Abstract

The harmful use of alcohol is a severe public health issue globally. Chinese per-capita alcohol consumption has increased sharply in recent decades, which has contributed to a rise in alcohol-related problems. In this article we present an analysis of Chinese alcohol policy, beginning with a characterization of alcohol consumption in China followed by an examination of how the nation's alcohol control policy has evolved over the past 30 years, identifying shortcomings and obstacles to improvement. Finally, we present several recommendations informed by the Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol and the SAFER Technical Package-Five Areas of Intervention at National and Subnational Levels (SAFER initiative), to the areas of taxation, alcohol availability, alcohol marketing regulation, and treatment.

Keywords: Alcohol, Alcohol policy, Alcohol control, China

Introduction

Many Chinese legends mention alcohol consumption, a widely accepted aspect of Chinese culture for millennia. It is sometimes associated with classical poetry, and famous Chinese poet Li Bai is known as China's ‘patron saint of alcohol’ (Cochrane et al., 2003).

Alcohol consumption continues to be a cultural norm in modern Chinese society, especially at social events such as traditional festivals, weddings, and business dinners, while drinking alone is relatively uncommon (Cochrane et al., 2003). Toasts made to one's guests are typically accompanied by the host exclaiming, “it is not a banquet without alcohol” in a show of respect. For many Chinese people, alcohol has an integral role in building and maintaining personal relationships. Drinking with colleagues or clients is now considered important for career advancement and job advertisements have even requested that applicants have a “good drinking ability” (Jiang et al., 2015).

Despite this long history and the social and cultural recognition of alcohol, until the early 1980s, alcohol-related problems were far less prevalent in China than in many western countries (Cochrane et al., 2003; Hao et al., 2005). Beginning in 1949, the alcohol industry was under the control of a state-owned monopoly, later dismantled as part of wider economic reforms throughout the period from the late 1970s to the early 1980s (Hao, 1995; Hao et al., 1999). The rapid economic and cultural shifts that followed this period of deregulation have contributed to the growth of the alcohol market in China (Guo & Huang, 2015; Hao, 1995; Hao et al., 1999). Risky drinking behaviors, such as excessive or frequent drinking, are reaching epidemic levels in China (Li et al., 2011). The prevalence of alcohol-related physical and mental illnesses has also risen steadily (Li et al., 2011; Hao et al., 1995). Since 1990, China has implemented several policies that have had a substantial impact on alcohol control, such as the prohibition of driving while intoxicated and the “Eight Rules” prohibiting officials from drinking alcohol during work hours (CPC Central Committee Political Bureau, 2012; Li et al., 2012). Still, China struggles with inadequate enforcement and out-of-date alcohol policies amounting to an overall strategy lacking in many aspects when compared to neighboring countries such as Russia, Thailand, and Japan, especially with regard to underage drinking (Tang et al., 2013; World Health Organization [WHO], 2018b). China requires alcohol control policy reform. This article presents an analysis of the impact that changes to China's alcohol policy have had on its effectiveness and outlines the considerations for developing a new Chinese alcohol control plan.

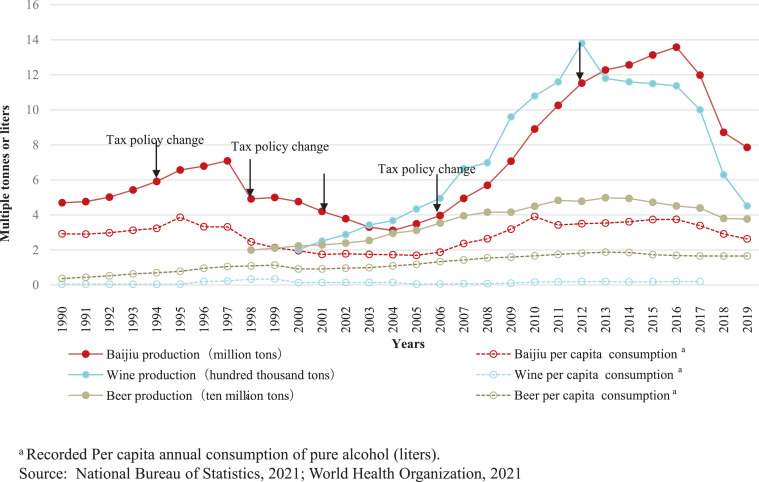

The status and trends of alcohol consumption and related harms in China

China's alcohol market has grown rapidly over the past 30 years to become one of the world's largest. Take, for example, the popular distilled spirit baijiu, the output of which increased from 7.09 million tons (5.76 liters per capita) to 13.58 million tons (9.78 liters per capita) between 1997 and 2016 (Fig. 1) (National Bureau of Statistics [NBS], 2021). This market growth has been accompanied by significantly increased consumption. Alcohol consumed was 7.2 liters per person in 2016, despite being only 4.1 liters per person in 2005, according to the Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018 (WHO, 2018b). In 2016, about 68.6% of men and 42.6% of women reported drinking alcohol in the past year (WHO, 2018a, 2018b). The WHO also estimated that 22.7% of Chinese (aged 15+ years) had engaged in heavy episodic drinking in 2016 (WHO, 2018a, 2018b). Although the prevalence of heavy episodic drinking in China was lower than the prevalence reported in some high-income countries such as Australia (39.2%) and New Zealand (35.2%), it was much higher than many other middle-income countries (e.g., 15.7% in Mongolia and 17% in India) (WHO, 2018a, 2018b).

Fig. 1.

Annual national production volume and average annual per capita consumption of alcoholic beverages (recorded) in China, 1990-2019.

China consumes a wide variety of alcoholic beverages, including strong baijiu (over 50% ABV), weak baijiu (30–40% ABV), rice wine (15–16% ABV), yellow rice wine and wine (12–18% ABV), beer (4–6% ABV), and medicinal liquors (Cochrane et al., 2003). Spirits, beer, and wine respectively accounted for 67%, 30%, and 3% of officially recorded Chinese alcohol consumption in 2016 (WHO, 2018b). It is believed that a substantial proportion of alcohol consumption, estimated to be 20.8%, is not reflected in the official consumption statistics (Tang et al., 2013; WHO, 2018b). With use particularly prevalent in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, this unrecorded alcohol is often priced lower than equivalent recorded beverages and can be high in ethanol, encouraging heavy drinking. It may also contain high concentrations of fermentation byproducts such as acetaldehyde (Newman et al., 2017; Rehm et al., 2014). As such, its use can pose significant long-term health risks to people who drink.

Congruent with patterns seen elsewhere in the world, both the prevalence and consumption of alcohol are higher in China among men when compared to women (Hao et al., 2004; Millwood et al., 2013; WHO, 2018b), though recent years have seen the prevalence of current drinking among women gradually increase (Slade et al., 2016). The prevalence of current alcohol use varies considerably by region within China. A large cross-sectional study sampled from 10 provinces found that mean weekly alcohol consumption among men ranged from 195g to 422g, and the prevalence of weekly drinking ranged from 7% to 51%, depending on the province (Millwood et al., 2013). The 2020 Youth Group Drink Consumption Insight Report describes increased alcoholic beverage consumption among Chinese youth, who are predicted to become the primary driver of the domestic alcohol market (CBNData, 2020). Together with the relative popularity of low-concentration alcohol products in this age group, this is believed to explain the emerging overall trend toward low-concentration products (CBNData, 2020).

The detrimental health impacts of alcohol consumption are globally widespread, responsible for 5.1% of the total disease burden and contributing to 3 million deaths each year (WHO, 2018b). Similarly, alcohol consumption is a major contributor to the total disease burden in China, where it was the eighth-greatest contributor to disability-adjusted life-years lost in China in 2019 (GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2020). Alcohol use disorder is a disproportionately male disease in China, even when compared to other countries. At 8.4% of men and 0.2% of women, males are approximately 42-times as likely to have alcohol use disorder (WHO, 2018b). According to a 2004 report by Hao et al., the overall prevalence of alcohol-induced mental disorders in China was about 5.1% (Hao et al., 2004). Alcohol also contributes to physical diseases, such as alcoholic liver disease, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and injuries such as resulting from vehicle collisions, violence, and suicide (GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators, 2018; WHO, 2018b). The annual prevalence of ALD in China steadily increased from 2.7% in 2000 to 4.4% in 2004, reaching as high as 8.74% by 2015 (Li et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2019). In the future, chronic liver diseases are predicted to become even more prevalent, driven mainly by increased ALD (Wang et al., 2019). Given the current level of alcohol-related harms and their projected increases, measures must be taken to control alcohol consumption.

Changes in alcohol policies and their impacts on alcohol production, consumption, and the burden of alcohol-related disease, 1990-2019

The World Health Organization has identified several highly cost-effective interventions to reduce the harmful use of alcohol, known as "best buys", which include increasing prices, limiting alcohol advertising, and limiting the availability of alcohol (WHO, 2011). We describe the implementation of these three “best buys” policies in China, with specific reference to alcohol tax policies, policies related to alcohol advertising, and restrictions on alcohol available to minors. In addition, we discuss the impact of anti-corruption measures upon alcohol consumption among civil servants and officials, as well as the successes of measures to prevent drink-driving in China.

Alcohol tax policy

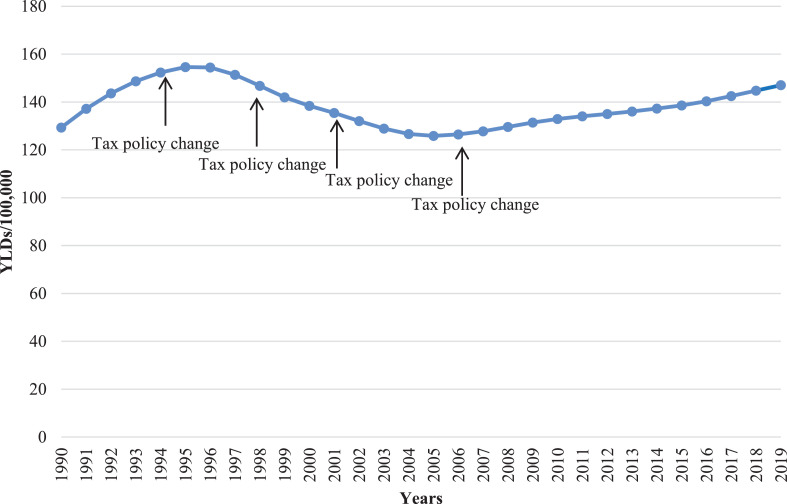

Alcohol taxes have long been an important source of government revenue in China. In 2017, about 30 billion Chinese Yuan (approximately 4.5 billion USD) in consumption tax was collected from the alcohol industry, making it the fourth-greatest contributor to total consumption tax revenue that year (Ma & Zhao, 2019). Since the rapid growth of the alcohol industry in post-reform 1980s China, the government has introduced, and subsequently made changes to, their alcohol taxation policy. As of 1984, the primary tax applied to baijiu was a production tax, set at 50% grain-derived baijiu and 40% for potato-derived baijiu (Guo & Huang, 2015). The tax reforms of 1994 saw these taxes removed and consumption taxes of 25% and 15% applied in their place (Guo & Huang, 2015). Beginning the year this policy was drafted, 1992, and continuing for several years, there was a rise in the production and consumption of baijiu, and alcohol-related disease burden grew in turn (Figs. 1, 3) (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation [IHME], 2019; WHO, 2018a). In response, the tax-deductible status of alcohol advertising was revoked in 1998, followed by introducing a volume-based tax (0.5 yuan/500 mL) in 2001. Dramatic reductions in baijiu production and consumption occurred between 1997 and 2003, with concurrent reductions in alcohol-related disease burden (Figs. 1, 3) (IHME, 2019; WHO, 2018a).

Fig. 3.

Trends in YLDs (per 100,000) attribute to alcohol use disorders in China, from 1990 to 2019.

In 2006, the tax distinction between grain and potato baijiu was removed and a uniform 20% consumption tax was instead applied (Tang et al., 2013). Consequently, the baijiu market and disease burden again grew rapidly (Figs. 1, 3) (IHME, 2019; WHO, 2018a). Baijiu producers’ exploitation of a tax loophole may have also contributed to this trend. The tax was calculated on wholesale price, so producers could sell baijiu at a reduced price to affiliated companies who would then sell at a markup (Chen, 2009). In response, the government required that alcohol excise tax could not be less than 70% of the final sale price of alcohol from 2009 (Chen, 2009).

Moreover, alcohol import duties and tariffs have gradually been reduced, with many alcoholic products receiving tariff-free status thanks to treaties signed since China became a member of the World Trade Organization two decades ago. For instance, wine imported from New Zealand has been tariff-free since 2012, and wine imported from Chile has been tariff-free since 2015 (Tang, 2015). Wine imports to China increased from 0.41 to 0.79 million tons between 2014 and 2017, with a corresponding wine-per-capita consumption increase from 1.8 to 2.0 liters (Figs. 1, 5) (NBS, 2021; WHO, 2018a; Zhongshang Research Institute, 2019). Despite this increase in consumption, the international competition in the wine market caused domestic wine production to fall (Figs. 1, 5) (NBS, 2021; WHO, 2018a; Zhongshang Research Institute, 2019). Some researchers have argued that eliminating import tariffs on alcohol products would reduce barriers, lower prices, boost consumption, and undermine government efforts to reduce alcohol consumption (Zeigler, 2006, 2009). As such, tariff-free policies may have detrimental effects on China's alcohol controls.

Fig. 5.

Wine production, import volume and per capita consumption in China, from 2014 to 2017.

Chinese alcohol tax policy affects the Chinese alcohol market and associated disease burden. Tax policy has helped reduce average alcohol consumption in China, but current efforts are insufficient to control the recent rise of alcohol-related harms. The low rate of taxation on alcohol in China compared to other countries is noteworthy, especially when considering high alcohol content products (WHO, 2004). In addition, since China's tax is not proportional to alcohol content it does not act to encourage the consumption of lower-strength options.

Drink-driving countermeasures

Drink-driving is a considerable risk factor for road traffic accidents (Xiang et al., 2016; Xiang et al., 2014). In 2003, the Chinese government demonstrated its determination to address road safety problems by adopting the first Road Traffic Safety Law at the 10th People's Congress (Li et al., 2012). China's 2004 national guidelines outlined a tiered system of blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limits, with a BAC of ≥0.08g ethanol/100ml blood considered drunk driving while a BAC below this limit but ≥0.02g/100ml BAC considered drink driving. To further improve relevant regulations, in 2011, the government revised the Road Traffic Safety Law passed in 2003, criminalizing drunk driving and increasing penalties (Li et al., 2012). The number of drink driving and drunk driving offenses fell by 18.7% and 42.7%, respectively, in the three years since the revision (Ministry of Public Security, 2014). However, serious alcohol-related traffic accidents continued to occur. The regulations were again reviewed on January 1, 2013, and the penalties became more severe (Li et al., 2012). According to a 2021 report by the Ministry of Public Security, approximately 20,000 fewer drunk driving deaths occurred in the 2010s than had occurred in the previous decade, roughly corresponding to the change in drunk driving deaths since drunk driving was criminalized (MPS, 2021). This would seem to indicate that the countermeasures were effective in reducing drunk driving deaths, though alternative explanations cannot be ruled out. Moreover, public awareness of the potential harms of drunk driving has increased thanks to the publicity of these regulations. Anecdotally, “driving without drinking, drinking without driving” has become a common phrase.

Nevertheless, in many regions, the potential for public policy to reduce alcohol-related traffic accidents has been hindered by a lack of human and financial resources, resulting in ineffective traffic enforcement (Jia et al., 2013; Jia et al., 2016; Jia et al., 2015). Despite breath alcohol testing being used to identify drivers over the limit, traffic police typically only test drivers they suspect to be over the limit, allowing many offenders to evade detection.

Restrictions on alcohol advertising

The policy formerly governing alcohol advertising in China was the Alcohol Advertising Management Approach, enacted in 1995, clearly delineating the authorized content, appearance and media of alcohol advertising. According to a report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, poor enforcement of this policy led to non-compliant advertisements being commonplace (Guo & Huang, 2015). It was abolished in 2017, and unfortunately, there has been no legislation specifically governing alcohol advertising in China since it was canceled. Instead, alcohol advertising now mainly falls under the control of other laws such as the Advertising Law and the Regulation on Broadcasting of Radio and Television Advertisements (National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China, 2018; National Radio and Television Administration, 2015). The transition away from an alcohol-specific policy has been accompanied by a softening of the law governing alcohol advertising. For example, the use of images of minors is no longer proscribed, but advertisements may still not appear in media intended for minors. A maximum of 12 advertisements for baijiu may appear on TV each day, with a maximum of two baijiu ads permitted between 7 p.m. and 9 p.m. Enforcement continues to be the weakest point of the policy governing alcohol advertising. For example, according to an advertising surveillance system, some channels of the state-owned broadcaster CCTV aired more than 60 alcohol ads per day and certain provincial TV channels typically aired no fewer than 20 alcohol ads per day during July 2021 (Jirang Technology Company, 2021).

Moreover, new forms of alcohol marketing have emerged in recent times. These include personalized digital advertising, sponsorship of events not directly related to alcohol, and corporate social responsibility strategies (CSR). CSR campaigns are marketing campaigns intended to improve a company's public image by focusing on their contributions to philanthropic or otherwise benevolent causes, strategies which critics have condemned for their semblance of public accountability despite their primary goal of furthering company interests (Yoon & Lam, 2013). Many major Chinese alcohol companies have CSR campaigns. For instance, Kweichow Moutai Group has a CSR section on their website describing their contributions to causes such as poverty alleviation, educational accessibility, and health promotion (Kweichow Moutai Group, 2021). Companies may also sponsor public events unrelated to alcohol, a tactic that is intended to enhance the company's image in a manner similar to CSR. Current regulations on alcohol advertising mainly target television broadcasts, and digital advertising is an emerging form of marketing that remains unregulated. These marketing strategies may pose a danger to public health as they are designed to circumvent the current regulations of alcohol marketing in China or to promote the notion that the societal benefits of alcohol far outweigh the social costs.

Underage drinking

A large cross-sectional study published in 2016 indicated that alcohol use is prevalent among Chinese adolescents, with a current drinking rate of 7.3% (Guo et al., 2016). A total of, 13.2% of students in China reported alcohol-related problems, which included social and behavioral problems (Guo et al., 2016). It seems that adolescents are less aware of the harms of alcohol consumption despite the evidence that adolescents are more sensitive to the neurotoxicity of alcohol than adults (De Micheli et al., 2016). Age of drinking onset is negatively correlated with their likelihood of developing heavy drinking later in life (Hingson et al., 2000). Therefore, it is important to strengthen the regulation of underage drinking, but China seems to pay little attention to it. The Law on the Protection of Minors, which protects minors under the age of 18, refers to the prohibition of alcoholic beverages to minors but does not specify a minimum drinking age (National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China, 2006). Business operators must prominently display “no alcohol to minors” signs, but there are no specific penalties for noncompliance. The law prohibiting the sale of alcohol to minors is not strictly enforced, thus the sale of alcohol to minors in China is commonplace (Ge, 2021). The Measures for the Administration of Alcohol Circulation policy, promulgated in 2006, stipulated a fine of 2000 yuan for the sale of alcohol to minors, but few businesses receive this penalty (Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China [MCPRC], 2005). This measure was eliminated in 2016 (MCPRC, 2005). These policies have not been vigorously enforced and have not been effective in curbing underage drinking (Dong, 2015). Intriguingly, some social organizations are concerned about underage drinking. The China Alcohol Association held the National Rational Drinking Publicity Week in 2016, focusing on underage drinking, but this, unfortunately, appears to have had little public health impact (Huang, 2016). Overall, underage drinking in China receives insufficient attention and is poorly regulated, so improvements are required to reduce its associated harms.

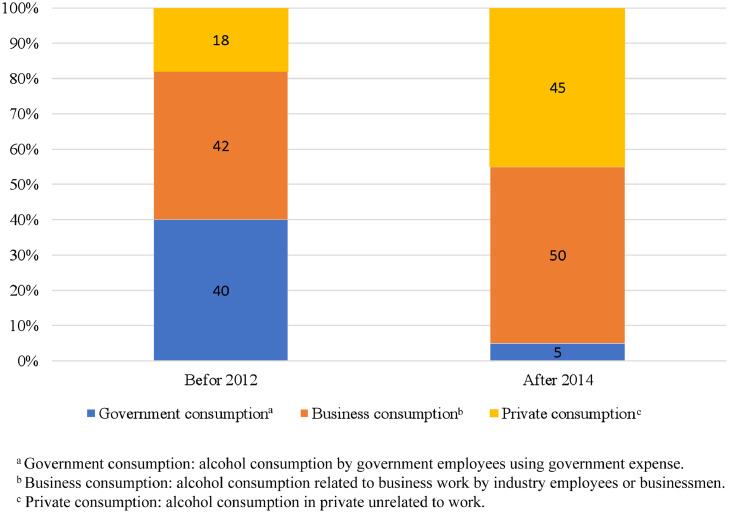

An anti-corruption campaign targeting drinking among governmental officials

Facilitated by China's economic prosperity, the Chinese alcohol industry experienced a “golden age” from 2003 to 2012, with the production of Chinese Baijiu increasing from 3.3 million tons (2.56 liters per capita) to 11.5 million tons (8.52 liters per capita) between these years (Fig. 1) (WHO, 2018a). Before 2012, it was not unusual for government officials, civil and military included, to drink alcohol during working hours at government expense. The public grew increasingly dissatisfied with the lavish banquets held during work hours to foster intragovernmental and private sector relationships. In the mind of the public, heavy drinking during working hours was closely associated with corruption, inefficiency, and the abuse of power (Tang et al., 2013). To address this, “Anti-corruption” regulation was introduced in 2012, including a ban on drinking among military personnel and the "Eight Rules" forbidding government officials from drinking alcohol while working (Central Military Commission of the People's Republic of China, 2012; CPC Central Committee Political Bureau, 2012). This anti-corruption campaign in China was well implemented and was followed by rapid declines in the sale of luxury alcohol products and declines in frequent drinking among government officials (Jiang et al., 2015), with the profile of the typical baijiu consumer changing accordingly. Government consumption dominated before 2012, but since the campaign's implementation, the proportion attributed to business and private consumption has increased (Fig. 4) (Insight and info, 2018). This shift suggests that consumption at government expense fell sharply in response to the anti-corruption campaign. These regulations, along with changes to drink-driving regulations, were also a hit to the alcohol industry and ended its “golden age”. After 2012, the growth rate of baijiu production, consumption, and the price was tempered (Figs. 1, 2) (WHO, 2018a).

Fig. 4.

Changes of Chinese baijiu consumption structure in China, before 2012 and after 2014.

Fig. 2.

Retail Price Index of Alcoholic Beverages in China, 2008-2018.

Recommendations

The rapid development of China's economy since the 1980s has been accompanied by the rapid growth of China's alcohol industry. We have seen how the consumption of alcohol has increased dramatically in China, along with the harms associated with alcohol use. Since 1990, the Chinese government has responded by adopting alcohol control policies of mixed efficacy. Undoubtedly, measures such as alcohol taxation, drink/drunk driving policy, and anti-corruption efforts have substantially impacted alcohol use. However, there are still some loopholes in alcohol management, especially in its marketing and availability to underage drinkers. We propose policy changes, informed by existing problems in alcohol management in China and the Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol and the SAFER initiative (WHO, 2010, 2019).

Develop a national action plan with a public health perspective

Taking effect in 2016, the Healthy China 2030 plan includes limiting alcohol consumption as one of its goals but fails to outline the strategies by which to accomplish it (State Council of the People's Republic of China, 2016). In stark contrast, China's highly successful national tobacco control strategy includes specific implementation plans, a clear indicator of an intent to reduce smoking-related problems (Chen et al., 2012). An analogous comprehensive national alcohol plan would assist China with alcohol control.

The alcohol industry is one of the largest light industries in China, and taxation of the industry is a major source of government revenue (Consumer Daily Network, 2021). Local governments will often actively support the alcohol production industry in regions where it is one of the major employment sources, due to the associated benefits to local government tax revenue (Guo & Huang, 2015). Despite this, the burden of disease attributable to alcohol cannot be understated: alcohol consumption leads to more than 83,000 liver cirrhosis deaths, 88,000 road traffic deaths, and 78,000 cancer deaths each year in China (WHO, 2018b). Consequently, in planning, policymakers should give priority to public health while giving due consideration to other interests. The new national alcohol plan will involve multiple sectors and stakeholders, so establishing a multi-sectoral alcohol coordination committee to direct all alcohol control policies will facilitate the plan.

Culture has a profound influence on drinking in China, as portrayed in common sayings roughly translated as, “it is not a banquet without alcohol,” “alcohol can cure disease,” and “drinking alcohol can reflect character.” A new national alcohol plan will only be successful if explicitly developed for the Chinese cultural context. Any public health strategy, especially in China, needs government commitment if it is to succeed.

Improve taxation policy

Alcohol price control is the most cost-effective measure governments have for controlling alcohol use (Elder et al., 2010). Also, in China, alcohol taxation has a significant impact, leading to lower alcohol consumption and fewer alcohol-related mortality (Chung et al., 2014). Further improvement in China's alcohol tax policy will promote better alcohol regulation. We call for increases in the overall tax rate and alcohol taxation reform. First, the tax structure on alcohol should be reexamined to identify and close loopholes such as tax avoidance, which have reduced the effectiveness of alcohol taxation in the past. Second, China would benefit from the adoption of a minimum unit alcohol pricing strategy, which has been shown to reduce average alcohol consumption (Anderson et al., 2021), and grading alcohol taxes based on ethanol content helps to guide low-strength healthy drinking. Third, alcohol is not an ordinary trade commodity, and reconsidering the role of alcohol products in trade agreements could be beneficial to public health in China. Finally, any change to alcohol taxation should be accompanied by measures to abate the possible unintended effects. For example, considering the availability of unrecorded alcohol in China, such as homemade and black-market alcohol, there is a risk that price controls may increase the consumption of these often-riskier alcohol products (Rehm et al., 2021). As such, we recommend that national monitoring systems be expanded to include high-quality data on these as-yet unrecorded varieties of alcoholic beverages.

Restrict alcohol marketing

Laws to restrict the marketing of alcohol are a vital consideration when aiming to reduce alcohol-related harm, particularly in the protection of minors. While the legislation governing alcohol marketing does require strengthening, particular emphasis should be given to improving the existing shortfalls in enforcement in this area if it is to effectively deter industry from breaching the advertising guidelines (Finan et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2017). It should be noted that a total ban on alcohol marketing would be more cost-effective than self-regulation in protecting vulnerable groups from alcohol marketing (Alcohol and Public Policy Group, 2010). In addition, the current policy efforts lag well behind the alcohol industry's marketing innovations. If alcohol marketing controls are to be effective, policymakers must also be quick to respond to new trends in alcohol marketing. One such example would be to limit alcohol sponsorship of events not directly connected to the alcohol industry.

Reduce the availability of alcohol and facilitate intervention and treatment

Restricting the availability of alcohol is one of the key measures recommended by the World Health Organization to reduce the burden of alcohol use and has been proven effective in many countries (Gruenewald, 2011; WHO, 2011). A systematic review shows that limiting alcohol outlet density could reduce excessive alcohol use and related harms (Bryden, Roberts, McKee, & Petticrew, 2012). Based on this, the strategy of restricting alcohol supply in China may be efficient for alcohol control in China, including limiting the density and trading hours of alcohol outlets, limiting the issuance of production licenses, or even the re-establishment of a government alcohol monopoly. Moreover, considering the need to protect minors from drinking-related harm, we suggest an underage drinking law that declares a minimum legal drinking age and a severe prohibition against sellers supplying alcohol to people below this age. Due to the current context of the widespread availability of alcohol despite one's age, these measures are necessary.

Shortcomings also exist in intervention and treatment, with a lack of resources and knowledge in the healthcare system being primary contributors. Effective and available treatment is vital in reducing alcohol-related harm, yet only a small percentage of severe AUD patients receive treatment in China (Tang et al., 2013). Many drugs are available in China for the treatment of alcohol dependence, such as disulfiram, nalmefene, naltrexone, and acamprosate, but some have not yet been officially approved (Li, 2016). There are few studies on the treatment of alcohol dependence in China, and specialized addiction services are inadequate in many parts of the country (Li, 2016; Tang et al., 2013). As such, there is a need to increase investment in alcohol treatment research, increase the number of specialist services and improve the affordability of healthcare.

Advance community-level action

Community action can play an important role in changing community attitudes and can encourage commitment to shared goals by cultivating a sense of ownership of alcohol control efforts (WHO, 2010). Some trials of community interventions such as the Sacramento Neighborhood Alcohol Prevention Project (SNAPP) have demonstrated that community interventions can significantly reduce alcohol-related problems, including the sale of alcohol to minors, underage drinking, and motor vehicle accidents (Treno, Gruenewald, Lee, & Remer, 2007). Based on this, interventions at the community level may contribute to the more effective implementation of national alcohol strategies. China can choose to promote awareness of the harms of alcohol through community advocacy, prevent the sale of alcohol to high-risk groups through community supervision, or reduce alcohol-related harm through other community-specific approaches, such as establishing community treatment services.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan [grant number 2021JJ30962], the World Health Organization [grant number 2019/971817-0], and the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 81571306].

Declarations of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Alcohol and Public Policy Group Alcohol: no ordinary commodity–A summary of the second edition. Addiction. 2010;105(5):769–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P., O’Donnell A., Kaner E., Llopis E., Manthey J., Rehm J. Impact of minimum unit pricing on alcohol purchases in Scotland and Wales: Controlled interrupted time series analyses. The Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(8):e557–e565. doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(21)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryden A., Roberts B., McKee M., Petticrew M. A systematic review of the influence on alcohol use of community level availability and marketing of alcohol. Health & Place. 2012;18(2):349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CBNData. (2020). 2020 Youth group drink consumption insight report. Retrieved from https://www.cbndata.com/report/2406/detail?isReading=report&page=1. May, 23 2021.

- Central Military Commission of China. (2012). The Central Military Commission issued ten regulations on strengthening its own style of work. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2012-12/22/content_2296301.htm. October, 27 2021.

- Chen L.F. A brief analysis of the administrative measures for the verification of the minimum taxable price of alcohol excise duty. China Collective Economy. 2009;2(21):127–149. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZJTG200921066.htm [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Shin Y.S., Beaglehole R. Tobacco control in China: Small steps towards a giant leap. The Lancet. 2012;379(9818):779–780. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61933-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung R.Y., Kim J.H., Yip B.H., Wong S.Y., Wong M.C., Chung V.C., Griffiths S.M. Alcohol tax policy and related mortality. An age-period-cohort analysis of a rapidly developed Chinese population, 1981-2010. Plos One. 2014;9(8):e99906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane J., Chen H., Conigrave K.M., Hao W. Alcohol use in China. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2003;38(6):537–542. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consumer Daily Network. (2021). Strengthen the standard of alcohol industry to serve a healthy China. Retrieved from http://www.xfrb.com.cn/article/news/10132319093042.html. May, 18 2021.

- CPC Central Committee Political Bureau (2012). Eight regulations for improving work style and keeping close contact with the masses. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2012-12/05/content_2283215.htm. October, 27 2021.

- De Micheli, D., & Andrade, A. LM, Silva, EA, & Souza-Formigoni, M. LO (2016). Drug abuse in adolescence.

- Dong Y. Who regulates underage drinking. Inside & Outside of Court. 2015;1(3):41. http://www.cqvip.com/qk/80051x/201503/664233133.html [Google Scholar]

- Elder R.W., Lawrence B., Ferguson A., Naimi T.S., Brewer R.D., Chattopadhyay S.K.…Fielding J.E. The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(2):217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan L.J., Lipperman-Kreda S., Grube J.W., Balassone A., Kaner E. Alcohol marketing and adolescent and young adult alcohol use behaviors: A systematic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2020;19(Suppl 19):42–56. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2020.s19.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1015–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31310-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1223–1249. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge, R. J. (2021). Representative Qiu Guanghe: Legislation will be passed to prohibit underage drinking and crack down on the sale of alcohol to minors. Retrieved from https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_11566529. March, 19 2022.

- Gruenewald P.J. Regulating availability: how access to alcohol affects drinking and problems in youth and adults. Alcohol Research & Health. 2011;34(2):248–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Deng J., He Y., Deng X., Huang J., Huang G.…Lu C. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among adolescents in China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2016;95(38):e4533. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000004533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Huang Y.G. The development of alcohol policy in contemporary China. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 2015;23(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao W. Alcohol policy and the public good: A Chinese view. Addiction. 1995;90(11):1448–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao W., Chen H., Su Z. China: Alcohol today. Addiction. 2005;100(6):737–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao W., Derson Y., Xiao S., Li L., Zhang Y. Alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems: Chinese experience from six area samples, 1994. Addiction. 1999;94(10):1467–1476. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941014673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao W., Su Z., Liu B., Zhang K., Yang H., Chen S.…Cui C. Drinking and drinking patterns and health status in the general population of five areas of China. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2004;39(1):43–52. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao W., Yang D.S., He M. Alcohol drinking in China:Present, future and policy. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;6(04):243–248. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZLCY504.016.htm [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R.W., Heeren T., Jamanka A., Howland J. Age of drinking onset and unintentional injury involvement after drinking. Jama. 2000;284(12):1527–1533. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.L. 2016 National Rational Drinking Publicity Week press conference was held in Beijing. Liquor-Making Science & Technology. 2016;1(11):53. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=NJKJ201611012&DbName=CJFQ2016 [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2019). GBD compare data visualization. Retrieved from http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare. October 19 2021.

- Insight and info. (2018). Analysis on consumption structure and main force of Chinese liquor industry in 2018. Retrieved from http://market.chinabaogao.com/yanjiu/0612342AR018.html. October 19 2021.

- Jia G., Fleiter J., King M., Sheehan M., Dunne M., Ma W. In: Proceedings of the 16th road safety on four continents conference. Wei Z., editor. The Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute; 2013. Reducing alcohol-related driving on China's roads: Traffic police officers' perceptions and practice; pp. 1–13.https://eprints.qut.edu.au/58922/ [Google Scholar]

- Jia K., Fleiter J., King M., Sheehan M., Ma W., Lei J., Zhang J. Alcohol-related driving in China: Countermeasure implications of research conducted in two cities. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2016;95(Pt B):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia K., King M., Fleiter J., Sheehan M., Ma W., Lei J., Zhang J. General motor vehicle drivers’ knowledge and practices regarding drink driving in Yinchuan and Guangzhou, China. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2015;16(7):652–657. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2014.1001509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Room R., Hao W. Alcohol and related health issues in China: Action needed. The Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(4):e190–e191. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(15)70017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Xiang X., Waleewong O., Room R. Alcohol marketing and youth drinking in Asia. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1508–1509. doi: 10.1111/add.13835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirang Technology Company. (2021). TV advertising market analysis. Retrieved from http://www.laptry.com/marketIndexAction_showView.do. August 20 2021.

- Kweichow Moutai Group. (2021). Social Responsibility. Retrieved from https://www.china-moutai.com/maotaijituan/shzr25/index.html. Nov 11 2021.

- Li J. People's Medical Publishing House; 2016. Guidelines for clinical diagnosis and treatment of alcohol use disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Jiang Y., Zhang M., Yin P., Wu F., Zhao W. Drinking behaviour among men and women in China: The 2007 China chronic disease and risk factor surveillance. Addiction. 2011;106(11):1946–1956. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Xie D., Nie G., Zhang J. The drink driving situation in China. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2012;13(2):101–108. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.637097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.M., Chen W.X., Yu C.H., Yue M., Liu Y.S., Xu G.Y.…Li S.D. [An epidemiological survey of alcoholic liver disease in Zhejiang province] Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi = Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi = Chinese Journal of Hepatology. 2003;11(11):647–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.C. & Zhao, Q. (2019). Some Thoughts on the Consumption Tax Reform in China. Taxation Research, 6(06), 30-35. doi:10.19376/j.cnki.cn11-1011/f.2019.06.006. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=SWXH201906006&DbName=CJFQ2019.

- Millwood I.Y., Li L., Smith M., Guo Y., Yang L., Bian Z.…Chen Z. Alcohol consumption in 0.5 million people from 10 diverse regions of China: Prevalence, patterns and socio-demographic and health-related correlates. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;42(3):816–827. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China. (2005). Measures for the administration of alcohol circulation. Retrieved from https://baike.so.com/doc/1044112-1104370.html.

- Ministry of Public Security. (2021). Reduced the number of deaths and injuries by more than 20,000 in the 10 years since drunk driving became a criminal offense. Retrieved from https://www.mps.gov.cn/n2254314/n6409334/c7859779/content.html. February 18 2022.

- Ministry of Public Security. (2014). Amendation of the drunk driving law brings positive effects. Retrieved from https://www.mps.gov.cn/n2254098/n4904352/c4922856/content.html. February 18 2022.

- National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China. (2006). Law on the protection of minors of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved from http://www.law-lib.com/law/law_view.asp?id=184008. October 27 2021.

- National Radio and Television Administration. (2015). Advertising law and the regulation on broadcasting of radio and television advertisements. Retrieved from http://www.nrta.gov.cn/art/2015/5/21/art_1588_43800.html. October 27 2021.

- National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China. (2018). Advertisement law of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved from http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c12435/201811/c10c8b8f625c4a6ea2739e3f20191e32.shtml.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2021). National data. Retrieved from https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=A01&zb=A020909&sj=202104. October 19 2021.

- Newman I., Qian L., Tamrakar N., Feng Y., Xu G. Composition of unrecorded distilled alcohol (bai jiu) produced in small rural factories in central China. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41(1):207–215. doi: 10.1111/acer.13280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Kailasapillai S., Larsen E., Rehm M.X., Samokhvalov A.V., Shield K.D.…Lachenmeier D.W. A systematic review of the epidemiology of unrecorded alcohol consumption and the chemical composition of unrecorded alcohol. Addiction. 2014;109(6):880–893. doi: 10.1111/add.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Neufeld M., Room R., Sornpaisarn B., Štelemėkas M., Swahn M.H., Lachenmeier D.W. The impact of alcohol taxation changes on unrecorded alcohol consumption: A review and recommendations. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T., Chapman C., Swift W., Keyes K., Tonks Z., Teesson M. Birth cohort trends in the global epidemiology of alcohol use and alcohol-related harms in men and women: Systematic review and metaregression. BMJ Journals. 2016;6(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State Council of the People's Republic of China. (2016). Outline of the healthy China 2030 plan. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm. June, 27.

- Tang D. Analysis of wine market under the impact of “zero tariff”. Science & Technology Vision. 2015;1(36):325. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KJSJ201536260.htm [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.L., Xiang X.J., Wang X.Y., Cubells J.F., Babor T.F., Hao W. Alcohol and alcohol-related harm in China: Policy changes needed. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;91(4):270–276. doi: 10.2471/blt.12.107318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treno A.J., Gruenewald P.J., Lee J.P., Remer L.G. The Sacramento Neighborhood Alcohol Prevention Project: outcomes from a community prevention trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(2):197–207. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2004). Global status report: Alcohol policy. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42801. October 27 2021.

- World Health Organization. (2010). Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44395. October 19 2021.

- World Health Organization. (2011). Scaling up action against noncommunicable diseases: How much will it cost? Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44706/9789241502313_eng.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2018a). Global Health Observatory data repository. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.GISAH?lang=en. December 28 2021.

- World Health Organization (2018b). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274603. October, 27 2021.

- World Health Organization. (2019). The SAFER technical package-five areas of intervention at national and subnational levels. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/the-safer-technical-package.

- Wang W.J., Xiao P., Xu H.Q., Niu J.Q., Gao Y.H. Growing burden of alcoholic liver disease in China: A review. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2019;25(12):1445–1456. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i12.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X., Luo T., Li R., Hu M., Huang H., Hao W. Association between drinking patterns and injuries in emergency room in three domestic general hospitals. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2016;41(9):992–997. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X.J., Li R.G., Wang X.Y., Cheng H.X., Liao Y.H., Hao W. Association between trauma and alcohol consumption in 508 emergency department patients. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;22(02):285–287. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2014.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S., Lam T.H. The illusion of righteousness: corporate social responsibility practices of the alcohol industry. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:630. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler D.W. International trade agreements challenge tobacco and alcohol control policies. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25(6):567–579. doi: 10.1080/09595230600944495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler D.W. The alcohol industry and trade agreements: A preliminary assessment. Addiction. 2009;104(Suppl 1):13–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhongshang Research Institute. (2019). China imported 729,677 kiloliters of wine in 2018, down 7.3 percent year on year. Retrieved from https://s.askci.com/news/maoyi/20190126/1051191140893.shtml. December 28 2021.