Abstract

Background:

Self-management regimens for oral and oropharyngeal cancer survivors can be complex and challenging. Effective self-management skills can foster better outcomes. We report on the development, feasibility, and pilot testing of a web-based self-management tool called “Empowered Survivor” (ES) for survivors of oral and oropharyngeal cancer.

Methods:

ES content was developed in two phases, with modules focusing on oral care, swallowing and muscle strength, and long-term follow-up. This single-arm pilot study consisted of a pre-, 2-month, and a 6-month postintervention survey.

Results:

Enrollment rates were relatively low. Once enrolled, data collected from the ES website indicated that 81.8% viewed ES. Participants provided positive evaluations of ES. Preliminary results indicate that ES had a beneficial impact on self-management self-efficacy, preparedness for survivorship care, and quality of life. ES improved survivors’ engagement in oral self-exams and head and neck strengthening exercises, improved ability to address barriers, and decreased information and support needs.

Conclusions:

This study provides preliminary evidence of engagement, acceptability, and beneficial impact of ES, which should be evaluated in a larger controlled clinical trial.

Keywords: posttreatment self-management, cancer survivors, self-efficacy

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Oral cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the world,1 and the 10th most prevalent type of cancer in men in the United States.2 An estimated 53 000 new cases of oral and oropharyngeal cancer and 10 860 deaths are estimated in the United States in 2019.3 Five-year survival rates have steadily increased from 52.5% to 66.3% over the past 30 years, resulting in a large and growing population of survivors.2 Treatment typically entails surgery, reconstruction, chemotherapy, and radiation. Because of the location of the structures involved, the disease, and the treatment, oral and oropharyngeal cancer results in debilitating and permanent disfigurement and functional changes that interfere with the ability to swallow, taste, speak, eat, and move the shoulders and neck.4–9 Thus, a primary goal of posttreatment care is to restore, maintain, and prevent future deterioration of function, enhance physical comfort, and monitor for recurrence.

Economic and time constraints affecting the provision of survivorship care services, oncology care providers may not have the time to fully address the care management needs of all oropharyngeal cancer survivors. Day-to-day responsibility for self-management is placed on the survivor. Self-management regimens may include daily oral care, ongoing surveillance, regular dental care, speech and swallowing rehabilitation, and management of existing and new cancer-related comorbidities that are the result of treatment. In addition to medical management, quality of life (QOL) is compromised for these survivors and is another aspect of self-management. Between 11% and 25%,10,11 of patients report a significant decline in global health-related quality of life (HRQOL), life satisfaction, role function, psychological well-being, and employment domains after treatment, contributing to the need to manage emotional, social, and financial concerns.12–14 Recent studies indicate that survivors struggle with the responsibilities associated with self-management.15

Effective self-management provides individuals with the ability to monitor their condition and implement the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional responses needed to maintain satisfactory functioning.16 As mentioned previously, effective self-management for survivors may focus on maintaining current functioning, preventing loss of functioning, and surveillance.17,18 There are relatively few evidence-based self-management interventions for cancer survivors. A recent review of self-management interventions for cancer survivors found only six published trials.19 The majority of these trials focused on a single symptom (fatigue) or a single self-management activity (physical activity), and most focused on care for breast cancer survivors. The key conclusion drawn from this review was that there was a need to develop and evaluate evidence-based self-management interventions for cancer survivors. There are no published randomized clinical trials evaluating a self-management intervention for oral and oropharyngeal cancer survivors. The goal of this pilot study was to address this gap by developing an online self-management intervention and obtain preliminary acceptability and efficacy data for the intervention.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study, we report on the development, feasibility, and pilot testing of a web-based, interactive decision aid called “Empowered Survivor” (ES) for survivors of oropharyngeal cancer. ES addressed key components of self-management of symptoms and surveillance. The study had two aims. The first aim was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of ES in a single-arm pilot study. Feasibility was measured as study enrollment and retention. Acceptability was assessed by use and evaluation of ES. The second aim was to obtain initial data assessing the impact of ES on the primary and secondary outcomes.

Intervention content was guided by social-cognitive theory. One key construct of social-cognitive theory is the development of self-efficacy, which is a belief in one’s ability to execute actions to deal with a situation successfully.20 Bandura20 proposed that self-efficacy is a task-specific expectation: People estimate their confidence in their ability to manage a situation by evaluating the specific tasks involved in successful completion of that task. Self-efficacy is considered a key psychological resource to assist people in managing chronic illnesses21 and plays a significant role in predicting both psychosocial and functional outcomes with chronic illness.22,23 ES content was guided by several other relevant constructs. First, Gollwitzer and Schwarzer’s work indicates that planning is a key component of self-management and achieving goals.24–27 Based on this, we focused on assisting patients in the process of planning: Setting goals, choosing strategies for goals, choosing strategies to overcome barriers, and obtaining support in achieving the goal. Second, we integrated the construct of activation, defined as the willingness to take actions to manage care and understanding one’s role in survivorship care.28 Third, we addressed information needs, defined as knowledge about treatment effects and care responsibilities. Knowledge of tasks is generally thought to improve self-efficacy, and it is also assumed that fewer information needs would be associated with higher self-efficacy. Fourth, we included support needs, defined as the level of assistance needed in accomplishing self-care tasks. Unmet support needs are strongly linked with lower self-efficacy.

We selected three primary outcomes that assess the goals of effective survivorship self-management: Self-efficacy to manage one’s care, preparedness for cancer survivorship, and head and neck-specific QOL. We evaluated a variety of secondary outcomes. Because the ultimate goal of self-management interventions is to improve the engagement in self-management behavior, we chose behaviors that are universal for oral and oropharyngeal cancer survivors: oral self-exams and engagement in head and neck mobility exercises. Regular self-exams to locate suspicious areas in the mouth and neck are recommended,29–31 as lesions that are not evident on positron emission tomography scans can be detected earlier and checked by a professional.32 Head and neck mobility exercises can foster the ability to eat, speak, and engage in activities of daily life,3,33 and our work suggests that engagement is relatively low. Finally, we assessed the processes targeted by the intervention, which are planning, activation, information needs, and support needs. This study was received approcal by of the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board. All study procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

2.1 |. Stage 1: intervention development

ES content was developed in two phases. In phase 1, the intervention content was programmed using the SNAP survey software (SNAP surveys Ltd, Thornbury, Bristol, 2012) (https://www.snapsurveys.com). The intervention was accessed as a URL website and participants were guided through webpages. The team focused on the most common information and support needs that were reported in a survey of 92 disease-free oral/oropharyngeal survivors who had been diagnosed 2 years to 5 years earlier in our previous work.34 The topics included how to recognize late effects of cancer treatment, how to recognize symptoms that should prompt calling a doctor, good nutrition, improving swallowing, fostering good oral health, and education about survivorship follow-up recommendations. We began with six modules. Module 1 focused on dry mouth—its causes, assessing symptoms, and managing it. Module 2 focused on dental hygiene—keeping one’s mouth clean, proper dental hygiene, and dental complications of dry mouth. Module 3 focused on swallowing symptoms and possible posttreatment complications—how to manage swallowing difficulty and when to seek speech pathologist services. Module 4 addressed detecting lesions: How to conduct an oral self-exam, signs to pay attention to, pictures of lesions, what to do if something is found, and what to expect during a professional oral exam. Module 5 focused on the nutritional impact of oral and oropharyngeal cancer, how to improve the sense of taste (helpful foods), managing mouth pain, and nutrition tips. Module 6 addressed long-term follow-up care: Why it is important, recommended follow-care, symptoms to discuss with your doctor, and preparing for follow-up visits. The team developed pictures and checklists for participants to use in each module. After the intervention was developed, we conducted a small utilization and evaluation study with 32 survivors, who were recruited from the Cancer Institute of New Jersey (CINJ) and diagnosed with oral or oropharyngeal cancer, off treatment, and disease free. They were sent the link to ES and asked to navigate it and provide input. Two-thirds of participants reported viewing all of the intervention, and the remaining participants reported that they completed a few sections. Participants requested information on ways to improve swallowing and neck muscle mobility.

In phase 2, this material was used to develop a professional-level, interactive online-mobile responsive intervention with ITX, a web development company. The team met regularly with ITX to create the intervention. The steps for this work were as follows:

Step 1: Construct the program:

Small chunks of information are particularly helpful for this patient population, who may carry comorbidities and have low education. Therefore, we combined content under key subjects and reduced complexity of information: Components of modules 1 and 2, dental care and nutrition, were combined with dry mouth care. Modules 4 and 6, detecting lesions and long-term follow-up care, were combined. To foster more interaction and behavioral change, an interactive goal setting and implementation planning component was added each module. The final modules were introduction, oral care, swallowing and muscle strength, and long-term follow-up.

Step 2: Develop interactive components:

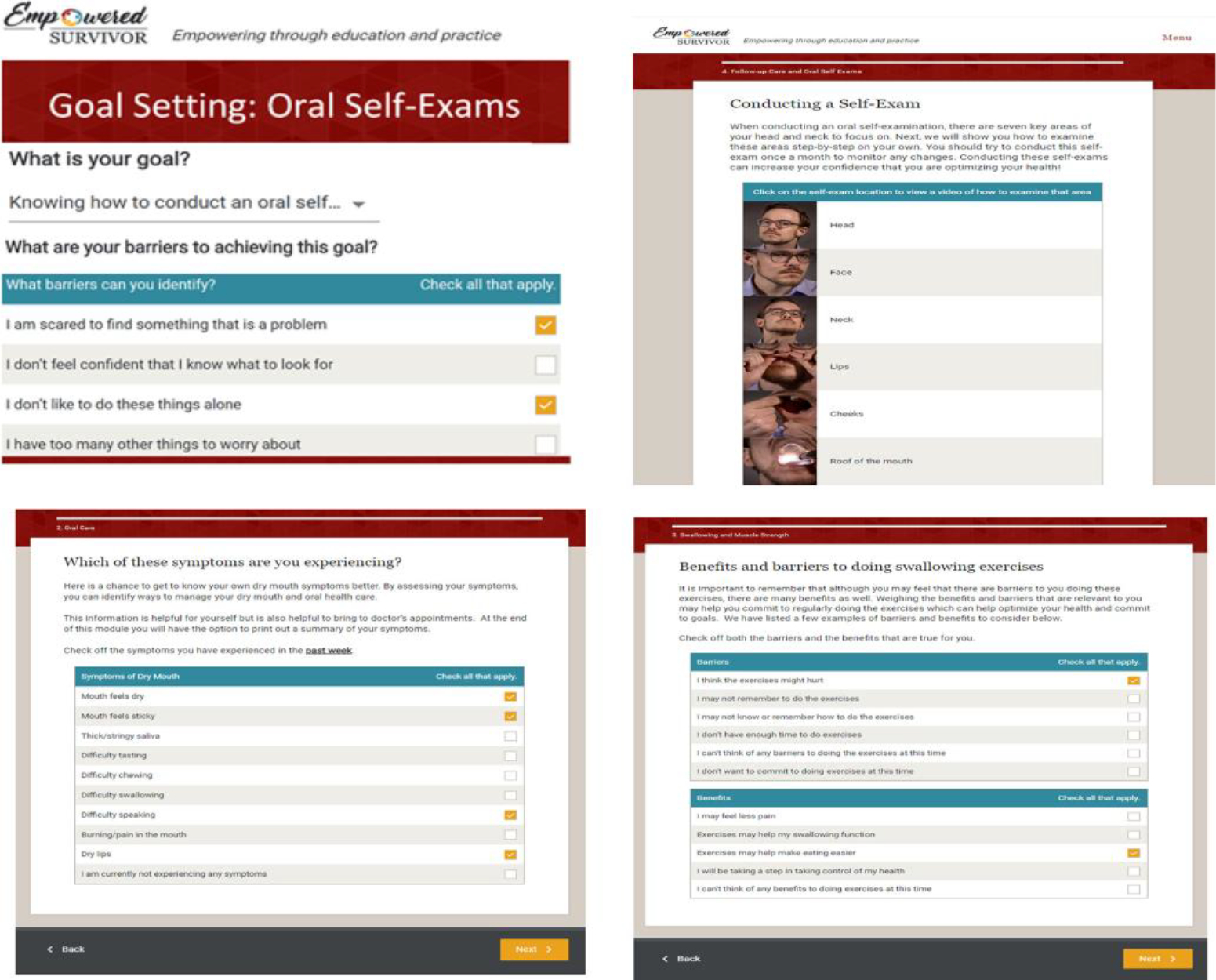

There were more than 22 interactive activities that were intended to engage participants and foster skill acquisition. For example, participants rated dry mouth and swallowing symptom severity, frequency, concern about each symptom, and confidence and importance of managing each symptom. In addition, participants selected a goal, rated the importance of the goal, chose from a menu of strategies, rated benefits and barriers to achieving the goal, confidence in achieving the goal, and needed goal support. The same format was used for dry mouth, swallowing, mobility exercises, and oral self-exams. Sample pages are shown in Figure 1. Each module included quizzes and narrated patient stories. Videotaped demonstrations of swallowing exercises, self-exams, and oral exams performed by a physician were included. Participants were asked if they had received a survivorship care plan and were provided the link to the survivorship care plan website. Recommendations for follow-up care were personalized to the time off-treatment. These recommendations were based on the widely agreed upon follow-up schedule (every 2 months for the first year, every 4 months for the second year, every 6 months for the third year, and once a year thereafter) with a suggestion that the patients would ask their oncologist for input on follow-up surveillance.35 A summary of ES content is provided in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Sample content of empowered survivor

TABLE 1.

Empowered survivor module description

| Module | Goals | Sample activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Introduction | Orient participants and introduce team Review program modules and navigation Enhance engagement with survivor stories |

Narrated introduction by oral surgeon Audiotaped survivor stories |

| 2. Oral care | Understand causes of dry mouth and what exacerbates it Assess dry mouth symptoms and severity Understand strategies to keep one’s mouth moist Choose strategies to manage dry mouth Develop a plan to implement these strategies |

Videotaped introduction by surgeon Patient experiences with dry mouth Self-assessment of dry mouth symptoms Tips for managing dry mouth Food preparation for dry mouth Goal setting, barriers, and strategies |

| 3. Swallowing and muscle strength | Understand the symptoms of swallowing difficulty Optimize swallowing ability Improve strength and mobility in head and shoulder Facilitate personal goal setting |

Self-assessment of swallowing difficulty Patient experiences with difficulty swallowing and range of motion Videotaped explanations of exercises by speech pathologist and occupational therapist Videotaped demonstrations of swallowing exercises Visual diagrams of neck and shoulder exercises Goal setting, barriers, and strategies |

| 4. Long-term follow-up care and detecting lesions | Understand how to do a self-exam Goal setting and managing barriers for self-exam Provide link to a survivorship care plan that includes follow-up recommendations Assess current smoking and alcohol use Review patient care team and general health screenings and recommendations |

Videotaped demonstrations of conducting oral exams with oncologist narration Patient experiences with conducting self-exams Assess tobacco and alcohol use Link to Drinker’s Checkup and Becomeanex Goal setting, barriers, and strategies |

Step 3: Obtain feedback:

Six oral or oropharyngeal cancer survivors recruited from the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey oncology practices participated in a feedback session. The study’s research assistant and project coordinator observed patients navigate ES. During the viewing, survivors provided comments about ES. After viewing, survivors completed two evaluation surveys. The first evaluation consisted of seven items assessing the materials (sample items: “Did you feel the material was presented in an accurate manner?” rated on a 7-point Likert scale, 1 = not at all, 7 = extremely, and “I learned something new from the information that was in the website,” rated on a 7-point Likert scale, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The second evaluation consisted of eight items assessing the ease of navigation, ease of comprehension, attractiveness, and general satisfaction with ES (sample items: “How easy was the ES web application to use?” “How much did you like the way that ES web application looked?” rated on a 5-point Likert scale, 1 = not at all, 5 = very). Average ratings were positive on the first survey evaluation: The material was presented in an accurate manner (M = 6.5, helped person navigate survivorship (M = 6.2, increased understanding of survivorship (M = 6.3), learned something new (M = 6.2), was interesting (M = 6.3), was valuable (6.3), and information was valid (6.3. Average ratings were also positive on the second survey evaluation: Easy to use (M = 4.5), satisfied (M = 4.5), kept interest and attention (M = 3.8), like it (M = 4.6), like the way it looked (M = 4.6), easy to understand (M = 5.0), easy to follow (M = 5.0), and useful (M = 4.4). Based on the feedback, the following changes were recommended: (a) Add details to the lesion pictures to illustrate where/what the lesion was and why it was suspicious; (b) enhance the goal-setting section to make clearer why it is beneficial, and (c) clarify site navigation and clearly indicate recommended exercises for the participant.

2.2 |. Stage 2: single-arm pilot study

2.2.1 |. Participants and procedures

Participants were recruited from the oncology clinics at the CINJ or RWJBarnabas Health, as well as from the New Jersey State Cancer Registry (NJSCR). Eligibility criteria were (a) age > 18 years; (b) diagnosed with a first primary oral or oropharyngeal cancer between 1 and 3 years ago; (c) currently cancer-free (but could experience a recurrence); (d) had computer access; and (e) read English.

Patients recruited from CINJ were identified from the outpatient clinic lists at CINJ. Patients were sent a letter about the study and then contacted by phone or in person during clinic visits. For patients recruited from the NJSCR, the NJSCR requires that the registry obtain physician assent and then reach out to the patient to obtain permission for the CINJ staff to contact them about the study. NJSCR staff reviewed patient eligibility, and, if eligible, send a letter to the patient’s diagnosing physician, making the physician aware that his/her patient is eligible. If the NJSCR staff did not receive a disapproval from the physician within 2 weeks, the patient was sent a cover letter and an “agreement to contact” sheet. Potential participants were called by registry staff to discuss the study. Participants had the option of verbally consenting (by a documented verbal consent form) to be contacted by CINJ staff about the study at that time or sending back a written consent form agreeing to be contacted by the CINJ staff. Contact information and consent forms from patients who consented for CINJ to contact them were sent to CINJ staff, who called the patient. Patients who were deemed eligible were provided with an online consent and survey. CINJ staff contacted patients weekly if they did not return the consent. Patients were considered passive refusers if they did not return a survey after repeated call attempts during days, nights, and weekends over a 3-week period after the letter was sent. Once the baseline survey was completed, participants were sent a link to ES. Participants who did not log into ES within a week were contacted and asked if they had any questions about ES or had trouble navigating it. Access to the intervention was allowed for the entire study duration, which was 6 months. The study entailed three surveys: Pre-intervention (baseline), 2 months after baseline (follow-up 1), and 6 months after baseline (follow-up 2). Participants were emailed a link to the Qualtrics surveys. Participants who did not complete a survey within a week were sent weekly emails and called. After 4 weeks, participants who did not complete either a baseline or a follow-up survey (depending on the stage of the study) were considered noncompleters for that survey. Participants received a $50 online gift certificate for completing each survey.

2.2.2 |. Primary outcome measures (all time points)

Self-efficacy to manage oral and oropharyngeal cancer care

A 22-item scale composed for this study assessed confidence in managing different aspects of self-care (eg, overall home care, dry mouth, dental care, nutrition, speech and swallowing exercises, neck and shoulder muscle strength and stiffness, follow-up medical appointments, oral self-exam, communicating with cancer providers, getting sufficient support and manage emotional concerns, stop using tobacco, and reduce alcohol intake). Participants were asked to rate their current confidence. Ratings range from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (very confident). An item average was calculated. Alphas were .91 at baseline and .85 at follow-up 1 and .94 at follow-up 2.

Preparedness for oral and oropharyngeal cancer survivorship

This 10-item scale, used in our prior intervention research on fostering preparedness among cancer patients,36 assesses whether information received about survivorship care was sufficient, easy to understand, helpful, addressed needs, and addressed self-care as well as how satisfied the participant was with the amount of information and the way information was provided. Participants were asked to rate their overall experience from the end of treatment until the present time. Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). Alpha values were .93 at baseline, .92 at follow-up 1, and .91 at follow-up 2.

Health-related quality of life

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire, Head and Neck Module (EORTC QLQ-HN35)37 is the most widely used measure of head and neck QOL and has been rigorously and systematically validated in 18 countries. Participants are asked to rate their symptoms in the past week. The scale has 30 items and 18 subscales (eg, pain, swallowing, social contact). Although not an established measure, due to the small sample size, only the total score is used in primary outcome analyses. We present the 18 separate subscales as supplemental analyses. Alpha values were .95 at baseline, .96 at follow-up 1, and .94 at follow-up 2. Higher scores indicate worse QOL.

2.2.3 |. Secondary outcome measures (all time points)

Performance and thoroughness of oral self-exams

This measure was composed for this study. Participants were asked if they performed a comprehensive exam of the inside of their mouth and neck in order to look for signs of cancer in the past month (yes/no). Those who reported conducting an exam reported if they checked each of 11 areas (eg, lower lip, inside of cheek). A total of body areas checked was used.

Performance of maintenance exercises

These items were composed for this study. Two items assessed engagement. First, participants were asked if they engaged in recommended swallowing exercises in the past month (examples were provided) (yes/no). Second, participants were asked if they engaged in exercises to improve or maintain their neck and shoulder muscle strength in the past month (yes/no).

Action and coping planning

Eight items assessed the degree to which a detailed plan was made to engage in self-care tasks (eg, engage in better oral care including the management of my dry mouth symptoms, manage difficulty swallowing, maintaining muscle strength and manage fatigue, and manage long-term follow-up care including detecting lesions through oral self-examinations).27,38 The item stems (eg, “I have made a detailed plan regarding what I need to do to…” and “I know what to do if something interferes with my plans to…”) were based on prior work assessing action and coping planning in non-oncology populations.38–40 The adaptation made was to alter the tasks to correspond to key self-care tasks. Sample items: “I have made a detailed plan regarding what I need to do to engage in better oral care including the management of my dry mouth symptoms,” “I know what to do if something interferes with my plans to manage my long-term follow-up care.” Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Participants rated their current experience. Alpha values were .95 at baseline, .94 at follow-up 1, and .92 at follow-up 2.

Patient activation

This 12-item measure based on the patient activation measure assessed the degree to which the participant perceived that they were responsible for managing their oral cancer care as well as whether they perceived that their actions will prevent or minimize symptoms.41 The original scale was adapted to reflect the focus on oral cancer care (eg, “When all is said and done, I am the person who is responsible for managing my health condition,” to “When all is said and done, I am the person who is responsible for handling my oral cancer care.”) This survey has not been used in studies of oral cancer survivors. Items were rated on a 4-point scale (1 = Disagree strongly, 4 = Agree strongly). Alpha values were .87 at baseline, .91 at follow-up 1, and .93 at follow-up 2.

Information needs

This 23-item scale was used in our prior study of 92 oral and oropharyngeal survivors34 and was adapted from the Health-Related Topics section of the FOCUS.42 Items assessed oral cancer topics (eg, managing dry mouth symptoms, improving any difficulty with swallowing, and getting social support from friends and family). Participants reported if they would like more information on each topic (yes/no). The number of “yes” responses was averaged. Alpha values were .90 at baseline, .91 at followup 1, and .92 at follow-up 2.

Support needs

The Supportive Care Needs Survey43 is a 34 item survey assessing physical, psychological, and health care system needs. Items included pain, anxiety, and being given explanations of tests. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they needed help in the past month (1 = No Need; Not applicable, “This is not a problem”, 2 = No need; Satisfied, “I did need help but my need was satisfied,” 3 = Low need; “It caused me concern and I had little need for additional help,” 4 = Moderate need—“It caused me concern and I had some need for additional help,” 5 = High need; – “It caused me concern and I had a strong need for additional help”). For the analysis, support needs that were rated as “moderate” (4) or “high” need (5) were summed, with a range of 0 to 34. Alpha values were .98 at baseline, .99 at follow-up 1, and .95 at follow-up 2.

ES evaluation

Two evaluations were given at follow-up 1 (two months). The first evaluation consisted of nine items based on our prior work evaluating online intervention with breast cancer patients44 (Sample items: “Did you feel the material that was presented in an accurate manner?” rated on a 7-point Likert scale, 1 = not at all, 7 = extremely, and “I learned something new from the information that was in the website,” rated on a 7-point Likert scale, 1= strongly disagree, 7= strongly agree, and “Did you show and/or discuss the information you received with your family and friends?” and “Did you show and/or discuss the information you received with any of your doctors?” rated as yes/no). Subsequent items assessed each module (eg, oral care, 6 items, swallowing and muscle strength, 4 items, long-term follow-up care, and six items). Items were answered if the participant reported viewing the module. Internal consistencies for the three module evaluation subscales were good (α = .85–.93).

The second evaluation consisted of eight items assessing the ease of navigation, ease of comprehension, attractiveness, and general satisfaction with ES (sample items: “How easy was the ES web application to use?” “How much did you like the way that ES web application looked?” rated on a 5-point Likert scale, 1 = not at all, 5 = very).44 Participants were provided with a list of additional topics not covered in ES (fatigue, worries about cancer coming back, and survivorship care plan) and were asked to indicate which they would like to see added. Open-ended questions also asked about participants’ opinions about the most positive and negative aspects of ES. ES use was assessed by average time spent in it and pages viewed. These data were tracked by the digital tool and not based on self-report.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Feasibility

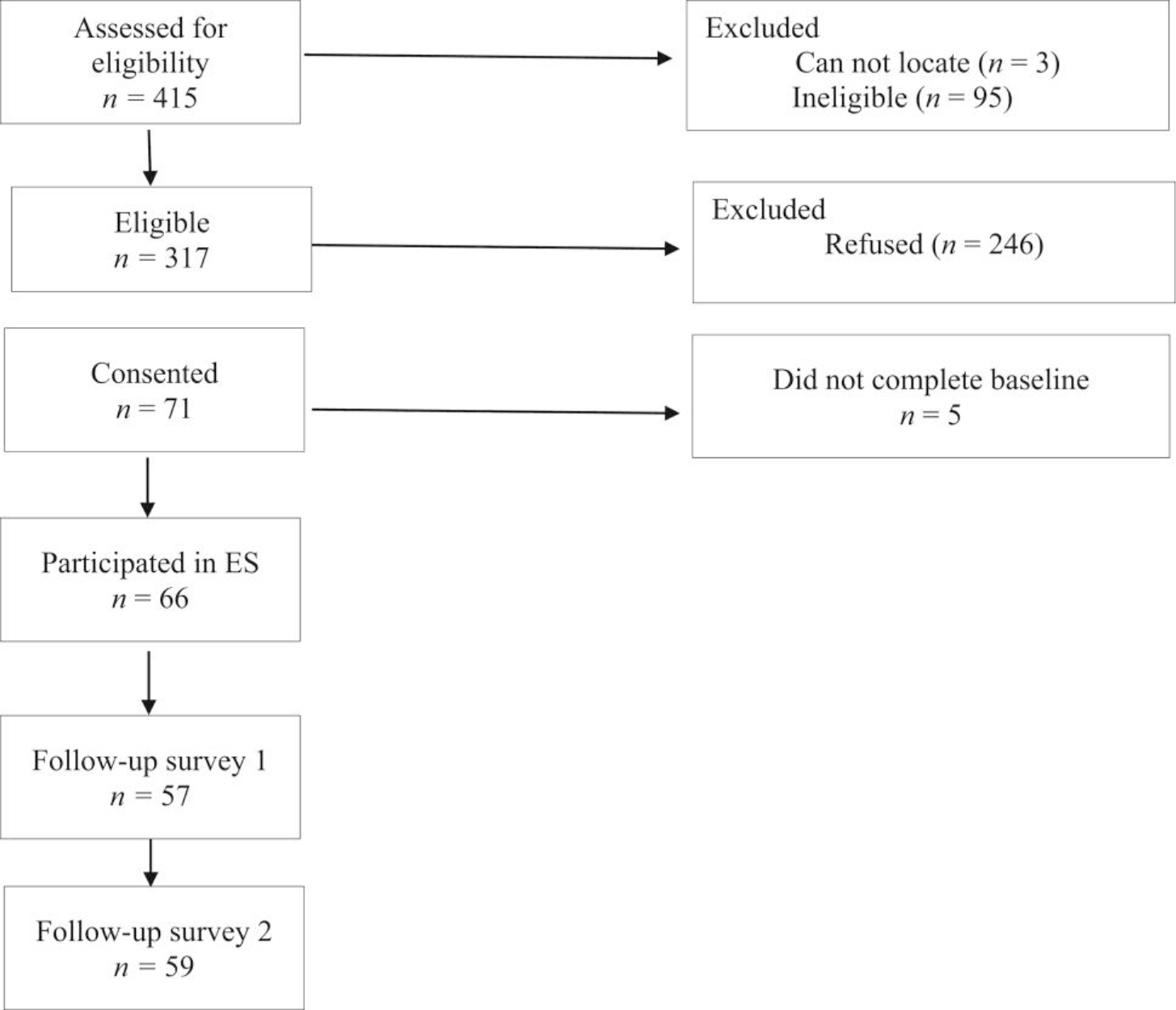

The study CONSORT is shown in Figure 2. Of the 415 patients approached, 95 were ineligible and three could not be located. Of the 317 remaining patients, 246 refused participation and 71 consented. Of the 71 who consented, 66 patients completed the baseline survey and were emailed the link to ES. Thus, the final sample included 66 patients. The acceptance rate was 20.8% of eligible participants (66/317). A comparison of the participants and refusers did not indicate significant differences on available demographic (age, sex) and medical information (time since diagnosis, cancer location, and cancer stage). However, study uptake was lower for the NJSCR (19.2%) than the other two sites (RWJBarnabas Health, 40%; CINJ, 71.4%) (χ2 = 13.48, P < .01). Follow-up survey completion was high: At follow-up 1, the completion rate was (57/66 = 86.4%); at follow-up 2, the completion rate was 59/66 = 89.4%.

FIGURE 2.

Study CONSORT

3.2 |. Sample

Table 2 shows sample characteristics. More than half of the sample was male (59%), the majority (86%) were non-Hispanic white, 73% were married or in a long-term relationship, slightly less than half had college or higher level of education, and the median annual family income was $75 000 to $99 999. Only 3% reported smoking during the past month (at baseline) and 59% reported drinking alcohol during the same time frame. It is interesting to note that slightly more than half of participants reported receiving a survivorship care plan.

TABLE 2.

Demographic and medical characteristics of the sample

| Variable | n (%) | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.2 (9.5) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 39 (59.1) | |

| Female | 27 (40.9) | |

| Ethnic background | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 57 (86.4) | |

| Minority | 7 (10.6) | |

| Missing | 2 (3.0) | |

| Education level | ||

| High school or less | 16 (24.2) | |

| Some college or trade school | 18 (27.3) | |

| College degree | 14 (21.2) | |

| Some graduate school or degree | 18 (27.3) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 31 (47.0) | |

| Part time | 3 (4.5) | |

| On leave | 3 (4.5) | |

| Retired/not employed | 21 (31.8) | |

| Other | 8 (12.1) | |

| Annual income (median) | $75 000 to $99 999 | |

| Less than $20 000 | 4 (6.1) | |

| $20 000 to $29 999 | 2 (3.0) | |

| $30 000 to $39 999 | 6 (9.1) | |

| $40 000 to $59 999 | 4 (6.1) | |

| $60 000 to $74 999 | 8 (12.1) | |

| $75 000 to $99 999 | 9 (13.6) | |

| $100 000 to $119 999 | 9 (13.6) | |

| $120 000 to $139 999 | 5 (7.6) | |

| $140 000 to 159 999 | 7 (10.6) | |

| $160 000 or more | 9 (13.6) | |

| Missing data | 3 (4.5) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 5 (7.6) | |

| Married | 45 (68.2) | |

| In non-marital relationship | 3 (4.5) | |

| Divorced | 6 (9.1) | |

| Widowed | 7 (10.6) | |

| Primary cancer | ||

| Tonsil | 22 (33.3) | |

| Lip | 2 (3.0) | |

| Tongue | 25 (37.9) | |

| Oropharynx | 1 (1.5) | |

| Gum and other mouth | 9 (13.6) | |

| Missing data | 7 (10.6) | |

| Disease stage | ||

| Localized | 17 (25.8) | |

| Regional | 34 (51.5) | |

| Receipt of SCP (yes) | 35 (53.0) | |

| Alcohol in past month | 39 (59.1) | |

| Smoked in the past month | 2 (3.0) |

Abbreviation: SCP, survivorship care plan.

3.3 |. Utilization of ES

Data collected from ES online indicated that use was high. Sixty participants (90.9%) logged in, and 81.8% of participants viewed three or four of the four modules. Among those logging in, average time spent in each module ranged from 13 minutes (module 1) to 25 minutes (module 3). The total time in ES ranged from 0 minutes to 272 minutes, with an average of 85 minutes.

3.4 |. Evaluation of ES

Results regarding the evaluation of ES are shown in Table 3. In terms of global ratings, material was considered educational, interesting, valuable, and valid, as average ratings ranged between 5.77 and 6.06 on the 7-point scale. . In terms of navigation ratings, participants reported that ES was relatively easy to use, easy to understand, and easy to follow, as average ratings ranged between 3.81 and 4.51 on a 5-point scale. Approximately 32% reported showing or discussing ES with their friends and/or family (n = 21/54 completing the item) and 22% of participants reported showing or discussing ES with their doctor (n = 15/54 completing the item). The most helpful aspects mentioned in comments were the demonstration of how to conduct an oral self-exam (n = 6), information and illustrations of exercises for head and neck strength and swallowing (n = 13), how to manage dry mouth (n = 7), and survivor stories (n = 5). The least helpful aspects of ES mentioned in the comments were aspects that did not pertain to the participant, and the suggestion that participants be able to skip those sections (n = 7). Of the 10 topics listed in ES that were not currently included that participants would like to be included, the most common were worries about cancer coming back (n = 32), fatigue and energy management (n = 28), how to talk with other health professionals (n = 11), information for family members or caregivers (n = 8), a survivorship care plan (n = 7), and a referral for speech pathology (n = 7).

TABLE 3.

Participant evaluations of empowered survivor (assessed at follow-up 1)

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Global ratings | M (SD) |

| Material presented in accurate mannera | 6.06 (1.10) |

| Helped educate how to best navigate survivorship phaseb | 5.88 (1.21) |

| Increased understanding of survivorship phaseb | 5.77 (1.11) |

| Learned something newc | 5.96 (1.15) |

| Information was interestingc | 5.96 (1.17) |

| Information was valuablec | 5.81 (1.21) |

| Information was validc | 5.77 (1.11) |

| Module and feature ratings | |

| Oral cared | 3.83 (0.75) |

| Swallowing and muscle strengthd | 3.91 (0.90) |

| Long-term follow-up cared | 3.99 (0.76) |

| Navigation, use, and satisfaction | |

| Easy to used | 4.21 (1.06) |

| Kept interest and attentiond | 3.81 (0.86) |

| Liked itd | 3.86 (0.86) |

| Liked way it lookedd | 3.92 (1.05) |

| Satisfied with itd | 3.86 (1.09) |

| Useful information providedd | 3.82 (1.10) |

| Easy to understandd | 4.29 (1.08) |

| Easy to followd | 4.51 (0.64) |

1 = not at all, 7 = definitely.

1 = not at all helpful, 7 = definitely helpful.

1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree.

1 = not at all helpful, 5 = extremely helpful.

3.5 |. Effects of ES on outcomes

Multilevel modeling was used to test for differences in outcomes as a function of time (baseline, follow-up 1, and follow-up 2). Unlike a repeated measures analysis of variance (which requires complete data for each participant), this approach allowed us to use all available data while still modeling the nonindependence due to repeated observations. For dichotomous outcomes (ie, whether the person conducted oral self-exams, did swallowing exercises, and did neck and shoulder muscle exercises), these analyses were conducted as binary logistic multilevel models. Significant main effects of time were followed by post hoc least significant difference pairwise tests. Results are shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Changes in outcomes at baseline, 2 months after baseline (follow-up 1), and 6 months after baseline (follow-up 2)

| Primary outcome | Baseline | Follow-up 1 | Follow-up 2 | F (df) | η 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | M | 3.93a | 4.22b | 4.32b | 14.74 (2111)** | 0.20 |

| SE | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |||

| Preparedness | M | 2.84a | 3.40b | 3.41b | 19.33 (2117)** | 0.25 |

| SE | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | |||

| HRQOL | M | 22.49a | 19.92b | 17.38c | 8.58 (2115)** | 0.13 |

| SE | 2.02 | 2.07 | 2.05 | |||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Oral self-exam | % | 59.1a | 80.6b | 83.7b | 11.30 (2178)** | 0.11 |

| SE | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |||

| Number of areas examineda | M | 4.12a | 7.45b | 8.44b | 32.94 (2114)** | 0.37 |

| SE | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.55 | |||

| Swallowing exercises | % | 19.6a | 40.9b | 41.3b | 7.83 (2175)** | 0.08 |

| SE | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | |||

| Muscle exercises | % | 32.9a | 55.2b | 48.7b | 6.72 (2176)** | 0.07 |

| SE | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | |||

| Action and coping planning | M | 3.42a | 3.86b | 3.97b | 12.55 (2116)** | 0.18 |

| SE | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | |||

| Activation | M | 3.28a | 3.39b | 3.50b | 7.72 (2116)** | 0.12 |

| SE | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |||

| Information needs | M | 0.44a | 0.32b | 0.27b | 15.76 (2116)** | 0.21 |

| SE | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |||

| Support needs | M | 3.23a | 2.31b | 2.19b | 3.46 (2113)* | 0.06 |

| SE | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.75 |

Abbreviation: HRQOL, health-related quality of life.

Number areas examined are the number of areas on the face and neck examined. Means (or percentages) that share the same subscript are not significantly different. Lower scores on HRQOL indicate better quality of life.

*P < .05; **P < .01.

As has been shown in the table, there were significant differences between the baseline and the two follow-up assessments for all of the primary and secondary outcomes examined. For all variables except QOL, the baseline differed from both follow-ups but the two follow-ups did not differ from each other. Reported self-efficacy, preparedness, the number of areas on the face and neck examined, action and planning coping, and activation increased from baseline to follow-up 1 and stayed high through follow-up 2. Information needs and support needs decreased in a similar fashion. In addition, the percent of participants who reported performing oral self-exams in the past month increased from 59% to over 80%, and the rate of swallowing and muscle exercises increased as well. Finally, the only variable that did not exactly fit this pattern was HRQOL. Like the other outcomes, this variable changed from baseline to follow-up 1, but it also changed from follow-up 1 to follow-up 2 such that individuals reported significantly lower scores (ie, better QOL) at each time point.

Table S1 illustrates the analyses of the 18 separate QOL subscales. Results indicated significant improvements in dry mouth, ability to open one’s mouth, trouble with social contact, trouble with senses, and speech problems.

4 |. DISCUSSION

This article described the development of ES, an online self-management intervention designed to foster effective self-management for survivors of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. ES provided information about common posttreatment symptoms as well as recommended surveillance, assessed the severity of some selected symptoms, presented information about managing selected symptoms, and facilitated goal setting. The first aim was to evaluate ES’s feasibility and acceptability. Enrollment rates were relatively low (approximately 20.8%) and lower than the limited acceptance rates that have been published for self-management interventions for survivors of other types of cancer (eg, Reference 45, 71%). Our current enrollment rate is also much lower than the enrollment rate of our prior observational studies of oral and oropharyngeal cancer survivors,34 which was 46%. Comparisons suggested that enrollment rates were higher for the two clinical settings than the registry recruitment settings. One explanation for this difference may be that the connection with the center where the patient was treated resulted in greater interest in survivorship care. However, once enrolled, retention in terms of completion of follow-up surveys was high. Utilization of ES was also very high: Most participants viewed ES (91%) and 81.8% of participants viewed at least three of the four modules. Furthermore, participants spent a relatively long period of time viewing it. Participants felt ES was easy to navigate and presented valid and useful information, and they felt the modules were helpful in navigating survivorship self-care.

The second aim was to evaluate the preliminary impact of ES. Given this was a small noncontrolled trial, all findings should be considered preliminary pending replication in a larger randomized clinical trial, the preliminary findings suggest that ES may have a beneficial impact on self-efficacy, preparedness for survivorship care, and QOL. Because self-efficacy is the key focus of the theoretical model underlying ES and the most important resource in self-management, the results of this study are consistent with the goals of the intervention. Our preliminary findings also suggest that ES may improve survivors’ engagement and thoroughness of their oral self-exams and increased engagement in head and neck strengthening exercises, suggesting a potential positive impact on important self-management practices. Consistent with our model of possible mechanisms of improvements in self-efficacy, our preliminary findings suggest that ES may reduce information and support needs and increased action and coping planning, which consists of having a plan in place of how managing self-care. It is important to note that the improvements were maintained at the second follow-up. Furthermore, our supplemental analysis suggests that ES impacted the aspects of QOL targeted in the intervention, including dry mouth, opening the mouth comfortably, trouble with saliva, and speech problems.

Overall, these findings provide promising data regarding engagement in, positive feedback about, and potential positive impact of ES. However, there are a number of limitations. First, enrollment in the study was low among participants recruited from the state registry as compared with the clinic settings. Survivors who participated may have been more motivated to work on their self-care and more interested in an online intervention, which would bias the study’s outcomes and possibly result in more favorable evaluations of ES. ES may not have as strong an impact among the broader population. Similarly, the study’s overall acceptance rate, at 20.8%, was relatively low and may adversely impact the feasibility of this work. The methods of improving study uptake should be considered in future research. Second, we did not include methods of keeping participants engaged after the first log-in. Effective self-management consists of integrating self-care tasks into daily life and maintaining changes, which is a longer term process, and involves trying out different self-management strategies.15 ES included goal setting, ascertainment of barriers, and solicitation of strategies to address barriers, but there was no follow-up outreach or additional content on how to set up a routine. Third, ES did not include a key concern in their feedback, management of anxiety about cancer recurrence. In addition, some participants noted that the content was not relevant for them. Fourth, we analyzed average self-efficacy across tasks and did not evaluate ES’s impact on self-efficacy for specific tasks (eg, mouth care). Due to the small sample size, we analyzed general QOL, which is not an established index, rather than the 18 separate subscales. Future studies with larger samples may illuminate the impact on task-specific self-efficacy and QOL domains. Fifth, our assessment of engagement in exercises assessed a month-long period of time and did not assess frequency. Future work should provide a more fine-grained assessment. Sixth, only 2 of the 11 outcome measures were widely validated instruments because there were no validated instruments to assess key study outcomes. Finally, this study was not a randomized clinical trial, and thus we do not know if these outcomes would have improved after completion of the baseline survey.

In our future work, we will address low uptake in our next study by enhancing explanation about the value of self-management and struggles to integrate it into daily life, include a maintenance aspect of the intervention, include a module on managing emotional concerns about recurrence, and conduct a randomized clinical trial. We will also consider targeting content based on relevant self-care needs and/or skills where the patient reports lower self-efficacy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Population Science Shared Resource as well as the New Jersey State Cancer Registry for their assistance with data collection. This study was funded by funds provided by the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

Funding information

Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Warnakulasuriya S Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Health. Surveillence, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer Stat Facts: Oral Cavity and Pharynx Cancer. 2019. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html. Accessed January 22, 2019.

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. 2015. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2015.html. Accessed January 22, 2019.

- 4.Russi EG, Corvo R, Merlotti A, et al. Swallowing dysfunction in head and neck cancer patients treated by radiotherapy: review and recommendations of the supportive task group of the Italian Association of Radiation Oncology. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(8):1033–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eades M, Chasen M, Bhargava R. Rehabilitation: Long-term physical and functional changes following treatment. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25(3):222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein DP, Ringash J, Bissada E, et al. Scoping review of the literature on shoulder impairments and disability after neck dissection. Head Neck. 2014;36(2):299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rieger JM, Zalmanowitz JG, Wolfaardt JF. Functional outcomes after organ preservation treatment in head and neck cancer: a critical review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35(7):581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang HL, Keck JF, Weaver MT, et al. Shoulder pain, functional status, and health-related quality of life after head and neck cancer surgery. Rehabil Res Pract. 2013;60:1768. 10.1155/2013/601768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Z, Brown JC, O’Malley BW Jr, et al. Post-treatment weight change in oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(5):2333–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abendstein H, Nordgren M, Boysen M, et al. Quality of life and head and neck cancer: a 5 year prospective study. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(12):2183–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oskam IM, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Aaronson NK, et al. Prospective evaluation of health-related quality of life in long-term oral and oropharyngeal cancer survivors and the perceived need for supportive care. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(5):443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, van Bleek WJ, Leemans CR, de Bree R. Employment and return to work in head and neck cancer survivors. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(1):56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammerlid E, Taft C. Health-related quality of life in long-term head and neck cancer survivors: a comparison with general population norms. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(2):149–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers SN, Hannah L, Lowe D, Magennis P. Quality of life 5–10 years after primary surgery for oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1999;27(3):187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunne S, Coffey L, Sharp L, et al. Integrating self-management into daily life following primary treatment: head and neck cancer survivors’ perspectives. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;28(4):742–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins J Tongue Strengthening: dysphagia intervention and prevention. in Annual Meeting of Dysphagia Research Society. Canada: Montreal, Quebec; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veis S, Logemann JA, Colangelo L. Effects of three techniques on maximum posterior movement of the tongue base. Dysphagia. 2000;15(3):142–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boland L, Bennett K, Connolly D. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1585–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A Self-efficacy: the exercise of control, New York, NY: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chirico A, Lucidi F, Mallia L, D’Aiuto M, Merluzzi TV. Indicators of distress in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1107. 10.7717/peerj.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansyur CL, Pavlik VN, Hyman DJ, Taylor WC, Goodrick GK. Self-efficacy and barriers to multiple behavior change in low-income African Americans with hypertension. J Behav Med. 2013;36(1):75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarzer R, Renner B. Social-cognitive predictors of health behavior: Action self-efficacy and coping self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 2000;19(5):487–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gollwitzer P Implementation intentions strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol. 1999;54(7):493–503. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luszczynska A, Schwarzer R. Planning and self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of breast self-examination: A longitudinal study on self-regulatory cognitions. Psychol Health. 2003;18(1):93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Osch L, Lechner L, Reubsaet A, Wigger S, de Vries H. Relapse prevention in a national smoking cessation contest: effects of coping planning. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(Pt 3): 525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5): 520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfister D, National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Head and Neck Cancer; (version 1.2016). 2019. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/head-and-neck.pdf Accessed January 22, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen EE, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(3):203–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Survivorship, Version 1.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(6):715–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathew B, Sankaranarayanan R, Wesley R, Nair MK. Evaluation of mouth self-examination in the control of oral cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;71(2):397–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logemann JA. Medical and rehabilitative therapy of oral, pharyngeal motor disorders. GI Motility online. 2006. 10.1038/gimo50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manne S, Hudson SV, Baredes S, et al. Survivorship care experiences, information, and support needs of patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1935–E1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oncology, ASCO. Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancer: Follow-Up Care. 2019. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/oral-and-oropharyngeal-cancer/follow-care. Accessed January 15, 2020

- 36.Manne S, Smith B, Mitarotondo A, Frederick S, Toppmeyer D, Kirstein L. Decisional conflict among breast cancer patients considering contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):902–908. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Tollesson E, et al. Development of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) questionnaire module to be used in quality of life assessments in head and neck cancer patients. EORTC Quality of Life Study Group. Acta Oncol. 1994;33(8):879–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sniehotta FF, Nagy G, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The role of action control in implementing intentions during the first weeks of behaviour change. Br J Soc Psychol. 2006;45(Pt 1):87–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pakpour AH, Hidarnia A, Hajizadeh E, Plotnikoff RC. Action and coping planning with regard to dental brushing among Iranian adolescents. Psychol Health Med. 2012;17(2):176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R, Fuhrmann B, Kiwus U, Voller H. Long-term effects of two psychological interventions on physical exercise and self-regulation following coronary rehabilitation. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(4):244–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rademakers J, Maindal HT, Steinsbekk A, Gensichen J, Brenk-Franz K, Hendriks M. Patient activation in Europe: an international comparison of psychometric properties and patients’ scores on the short form Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13). BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institute of Health, N.C.I. Follow-up care use among survivors (FOCUS) survey. 2019. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/resources/focus.html. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- 43.Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Brief assessment of adult cancer patients’ perceived needs: development and validation of the 34-item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34). J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(4):602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manne SL, Smith BL, Frederick S, Mitarotondo A, Kashy DA, Kirstein LJ. B-Sure: A randomized pilot trial of an interactive web-based decision support aid versus usual care in average-risk breast cancer patients considering contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(2):355–363. 10.1093/tbm/iby133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith SK, MacDermott K, Amarasekara S, Pan W, Mayer D, Hockenberry M. Reimagine: a randomized controlled trial of an online, symptom self-management curriculum among breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:1775–1781. 10.1007/s00520-018-4431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.