Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to discover the effects of coconut oil intake and diet therapy on anthropometric measurements, biochemical findings and irisin levels in overweight individuals.

Materials and methods

Overweight individuals (n = 44, 19–30 years) without any chronic disease were included. In this randomized controlled crossover study, the participants were divided into two groups (Group 1: 23 people, Group 2: 21 people). In the first phase, Group 1 received diet therapy to lose 0.5–1 kg of weight per week and 20 mL of coconut oil/day, while Group 2 only received diet therapy. In the second phase, Group 1 received diet therapy while Group 2 received diet therapy and 20 mL of coconut oil/day. Anthropometric measurements were taken four times. Irisin was measured four times by enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) method and other biochemical findings were measured twice. Statistical analysis was made on SPSS 20.

Results

The irisin level decreased significantly when the participants only took coconut oil (p ≤ 0.05). There was a significant decrease in the participants’ body weight, body mass index (BMI) level and body fat percentage (p ≤ 0.01). Insulin, total cholesterol, low density lipoproteins (LDL) cholesterol, and triglyceride (TG) levels of all participants decreased significantly (p ≤ 0.05). There was no significant difference in irisin level due to body weight loss (p ≤ 0.05); coconut oil provided a significant decrease in irisin level (p ≤ 0.05).

Conclusion

Diet therapy and weight loss did not have an effect on irisin level, but coconut oil alone was found to reduce irisin level. Coconut oil had no impact on anthropometric and biochemical findings.

Subject terms: Nutrition, Nutritional supplements

Introduction

The hormone irisin is a myokine that was first detected by Bostrom et al. and is released into the blood from skeletal muscle after exercise [1]. This myokine hormone was found to have essential physiological functions such as the conversion of white adipose tissue to brown adipose tissue, acceleration of fat oxidation, and increase in metabolic rate [2, 3]. Irisin, a type of peptide released from the muscles, was found to be a product of type 1 membrane fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 (FNDC5). This protein, FNDC5, is stimulated by the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPARy), which is stimulated by exercise. It was discovered that FNDC5 increases thermogenesis and energy expenditure by turning white adipose tissue into brown after exercise. Increased irisin level was found to improve glucose tolerance by increasing the release of FNDC5 in the liver. Along with these physiological functions, irisin is argued to hold an important place in the physiopathology of chronic diseases [4]. While there are studies in the literature revealing that the plasma irisin levels of individuals with obesity, type 1 and/or type 2 diabetes are higher than those of healthy individuals, there are also studies reporting otherwise [5–7]. In an in vivo study conducted with cells obtained from humans, it was found that irisin regulates both the browning and the protein expression of genes associated with UCP-1 (thermogenin: a protein found in the mitochondria of brown adipose tissue) and thus the effect of irisin on the browning of white adipose tissue was revealed [5–7]. It was found that the level of irisin, one of the circulating myokines, decreased both in the group undergoing a low-calorie diet therapy and that undergoing a bariatric surgery in individuals with overweight [8]. Irisin activates the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-protein kinase A (PKA)-hormone-sensitive lipase pathway that stimulates lipolysis by binding to the irisin hormone receptor in metabolism. After the cAMP is activated, hormone sensitive lipase is also activated as a result of the increase in the cAMP in the cell. Thanks to hormone sensitive lipase, energy expenditure and lipolysis are increased [9]. In a study investigating the relationship between the hormone oxytocin, which is secreted from the central nervous system and regulates food intake, and irisin, it was argued that irisin levels may also regulate food intake. In this study, irisin affected food intake associated with the hormone oxytocin [10]. In addition, irisin levels, which were found to be high in individuals with overweight, were also found to be higher in individuals with overweight (those with BMI levels of 25–29.9 kg/m2) compared to healthy individuals [11]. Referring to a BMI classification of 25–29.9 kg/m2, mild obesity is a clinical picture that appears prior to obesity, and an important diagnosis for the prevention of obesity and the morbidity and mortality risk that comes with it. Obesity can be prevented with appropriate treatment methods in this clinical picture before obesity. Obesity and mild obesity are chronic diseases that carry the risk of morbidity and mortality and can be prevented/treated with multidisciplinary treatment methods. Diet therapy for obesity and mild obesity is based on reducing daily energy intake and keeping macro and micronutrients at recommended intake levels [12]. In addition, although some functional treatment options have been mentioned in the literature, enough evidence has not been obtained to show their applicability in treatment. One of these functional treatment options is adding coconut oil to the diet. Containing medium-chain fatty acids, coconut fruit and the oil obtained from it have been stated to be effective in the treatment of obesity and related chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [13]. The feeling of hunger was found to decrease significantly during the day as a result of adding 25 ml of coconut oil to breakfast meals in women, and thus weight control became easier [14]. There is research showing that coconut oil consumption is effective in the treatment of insulin resistance and related T2DM as it increases the sensitivity of cells to insulin [15]. Another study showing that coconut oil helps the waist circumference get thinner, a significant decrease was found in the BMI levels of the individuals [16]. In addition, it is argued that coconut oil may help reduce inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-10), which are elevated in individuals with overweight [17].

The literature indicates that coconut oil increases the metabolic rate, supports weight loss, and helps to create a feeling of satiety. Hormone irisin was found to play an important role in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases and in exercise. In light of this, there is no study in the current literature investigating the relationship between coconut oil consumption and irisin hormone level during body weight control, and there is also no study including a nutritional intervention performed to regulate irisin level in individuals with overweight [18]. Addressing this deficiency in the literature, this study aimed to determine the change in the level of irisin hormone during the weight-loss process. This study was designed and carried out to determine whether irisin hormone is an important marker in the pathophysiology of obesity, to determine whether the effect of coconut oil, which is reported to be effective in weight control, is related to irisin, and to determine whether coconut oil is suitable for routine use in the diet treatment of obesity, the prevalence of which is increasing in our country and in the world, and complications of which lead to an increase in the prevalence of mortality and morbidity, and in health expenditures.

Method

This is a randomized controlled study adopting two-phase cross-sectional design. It was conducted with students studying at Bahcesehir University. This study was initiated after it was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Bahcesehir University with the decision numbered 22481095–020–500 on 11.02.2020. In addition, the study was supported by the Bahcesehir University Scientific Research Project commission with the project support numbered BAUBAP 2021.01.01.

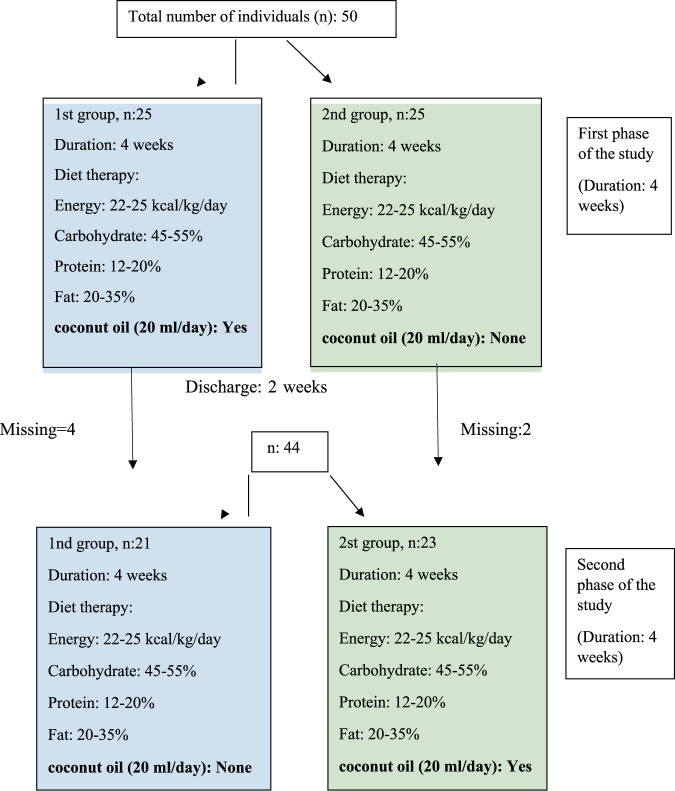

Patients

The sample size was calculated as 44 as a result of the G-power analysis in the beginning of the study, but 50 people were contacted considering possible losses. However, 6 people were excluded from the study due to non-compliance with the diet. All groups in the study consisted of adult individuals between the ages of 19–30 with a BMI level of 25 kg/m2−29.5 kg/m2. In the first phase, the first group (n = 21) was given 20 mL/day of coconut oil for 4 weeks in addition to their energy-containing diet that aims to have each individual lose 0.5–1 kg of weight per week while the second group (n = 23) was only given the same kind of energy-containing diet. After the first phase ended after four weeks, nutritional intervention was not applied to all individuals in the excretory phase (2 weeks). In the second phase, the first group was given energy-containing diet to allow each individual to lose 0.5–1 kg of weight per week while the second group was given 20 mL/day coconut oil in addition to the same energy-containing diet as group 1. The design of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Study design.

In the first phase, the first group (n = 21) was given 20 mL/day of coconut oil for 4 weeks in addition to hypocaloric diet. The second group (n = 23) was only given the hypocaloric diet. In the second phase, the first group was given hypocaloric diet while the second group was given 20 mL/day coconut oil in addition to the hypocaloric diet as group 1.

-Inclusion criteria for the study: Individuals between the ages of 19–30 and without a chronic disease were included in the study.

-Exclusion criteria for the study: Individuals who were underweight, normal weight, overweight and morbidly obese according to their BMI levels were not included in the study. In addition, individuals who do regular physical activity (athletes, those who exercise more than 30 min a day, heavy workers) were not included in the study.

-Diet Therapy: Containing energy intake of 22–25 kcal/kg/day, a diet therapy in which the ratio of macronutrients to energy was 45–55% of carbohydrates, 12–20% of proteins and 20–35% of fats [19, 20]. In the first phase, the first group was asked to consume 2 tablespoons of coconut oil per day by adding it to their coffee and/or tea in addition to their nutrition plan. In this phase, the energy from the coconut oil was calculated within the contribution of the fat content of the diet therapy to the energy (20–35%), and the total fat content of the plan was calculated the same as the other group. Coconut oil was not given to the individuals in the second group in the first phase.

Data collection

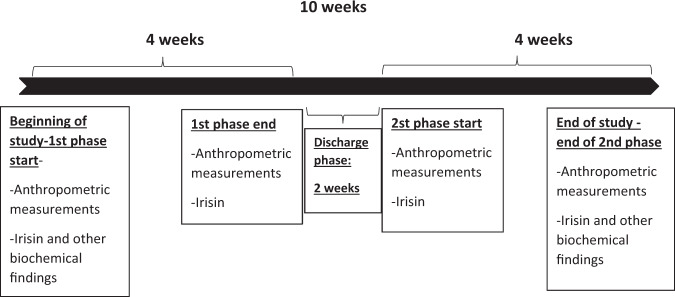

At the beginning of the study, data regarding age, gender, smoking and alcohol use, presence of food allergy, use of nutritional supplements, and previous weight loss diet attempts were obtained with the Personal Information Form. Nutritional habits of the participants were also obtained with the questions in this form (weekday and weekend diet, number of main and snack meals) Fig. 2. Anthropometric measurements and biochemical findings obtained at regular intervals throughout the study process were recorded in the form. In the first and second phases, 3-day food consumption records were obtained with the “Food Consumption Record Form” in order to check whether the participants adhered to the diet therapy throughout the study and to determine the daily macro- and micro-nutrient intake levels.

Fig. 2. Data collection.

Anthropometric measurements and blood samples were taken at the beginning and the end of the first phase, the beginning and the end of the second phase. The insulin, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were measured at the beginning and end of the study. Irisin hormone measured 4 times in total, at the beginning and end of both phases.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements of the participants were taken at the beginning of the study, the end of the first phase, the end of the excretory phase (beginning of the second phase) and the end of the second phase at the Anthropometry Laboratory of the Faculty of Health Sciences of Bahcesehir University. In addition, in order to motivate the participants, they were asked to measure their weight on their own weighing devices and report it to the researcher every week. Out of the anthropometric measurements, weight, waist circumference, BMI, detailed body analysis and waist/hip ratio were obtained from all individuals during face-to-face interviews conducted 4 times in total.

Biochemical findings and irisin

The blood samples of the participants were taken 4 times at the Mecidiyeköy branch of Düzen Laboratory at the beginning and end of the first phase, after the excretory phase, that is, at the beginning of the second phase, and at the end of the second phase. In order to determine the hormone irisin in all of the blood samples taken from each participant on a total of 4 different dates, and to determine the insulin, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels in the blood samples taken at the beginning and end of the study, the blood samples were sent to the Ankara Branch of Düzen Laboratory and stored under appropriate conditions. All these processes were carried out in accordance with the working principles of Düzen Laboratories Group.

The insulin, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels of the participants were measured twice, i.e. at the beginning and end of the study. The HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglyceride tests were performed by the spectrophotometric method using Roche Cobas c501 analyzer. The insulin test was performed by the ECLIA method using Roche Cobas e601 analyzer. The LDL cholesterol levels of the participants were calculated according to the Friedewald formula. This formula is LDL Cholesterol = Total Cholesterol – (Measured HDL Cholesterol + TG/5) [21]. Human Irisin ELISA kit (2 pieces, 96 plate wells in 1 piece) by Elabscience company was used for the hormone irisin, which should be determined 4 times in total, at the beginning and end of both phases.

Statistical analyses

The obtained data were statistically analyzed in the SPSS 20.0 program. Statistical significance was accepted as p < 0.05 in all analyzes. The fit of the data to the normal distribution was checked with the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. Number, percentage, mean and standard deviation values are included in the descriptive statistics. Pearson Correlation test was run to determine the relationship between the variables. Paired Sample t-Test was used if the pairwise comparisons of the variables at the end of each phase and at the end of the study showed a normal distribution, and Wilcoxon paired-sample test was used in cases that did not comply with the normal distribution. Mann–Whitney U test was used to evaluate the differences between the groups.

Findings

Thirteen males (29.5%) and 31 females (70.5%) participated in the study. It was found that 13.6% of the participants were smokers and 86.4% were non-smokers. Of the participants, 22.7% were drinking alcohol as social while 77.2% were not. While 38.6% of the participants were using regular medication, 61.4% were not. While 36.4% of the participants were taking regular vitamin-mineral supplements, 63.6% were not. While 4.5% of the participants had food allergy, 95.5% do not. All of the participants (100%) had previously undergone a weight loss diet and were eating properly on weekdays. While 63.6% of the participants were eating properly at weekends, 36.4% were not. While 84.1% of the participants had 2 main meals a day, 15.9% had 3. Of the participants, 9.1% had 1 snack, 15.9% had 2 snacks, 75% had 3 snacks.

At the beginning of the study, no significant difference was found between the two groups in all anthropometric measurements and biochemical findings, and the anthropometric measurements of the groups were homogeneous Tables 1–5. While the mean irisin level of the participants in Group 1 was 35.81 ± 4.68 ng/dL at the beginning, it was 29.14 ± 7.43 ng/dL at the end of the first phase. At the end of the first phase in Group 1, it was revealed that the irisin level of the participants decreased significantly as a result of the intake of coconut oil (p = 0.000). While the mean irisin level of the participants in Group 2 was 31.36 ± 7.52 ng/dL at the beginning, it was 29.77 ± 7.95 ng/dL at the end of the first phase. At the end of the first phase in Group 2, it was found that the irisin level of the participants did not change significantly after undergoing diet alone (p = 0.106).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics and nutritional habits of participants.

| Number of participants n | Percentage % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 31 | 70.5 |

| Male | 13 | 29.5 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 6 | 13.6 |

| No | 38 | 86.4 |

| Use of alcohol | ||

| Yes | 10 | 22.7 |

| No | 34 | 77.2 |

| Regular use of medication | ||

| Yes | 17 | 38.6 |

| No | 27 | 61.4 |

| Regular use of vitamin-mineral | ||

| Yes | 16 | 36.4 |

| No | 28 | 63.6 |

| Food allergy | ||

| Yes | 2 | 4.5 |

| No | 42 | 95.5 |

| Have you followed a weight loss diet before? | ||

| Yes | 44 | 100.0 |

| Number of meals | ||

| 2 | 37 | 84.1 |

| 3 | 7 | 15.9 |

| Number of snacking | ||

| 1 | 4 | 9.1 |

| 2 | 7 | 15.9 |

| 3 | 33 | 75.0 |

Table 3.

Anthropometric measurements and biochemical findings of the groups before the intervention.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Total | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 21 | n = 23 | n = 44 | |||

| X ± SD | X ± SD | X ± SD | |||

| Weight (kg) | 80.58 ± 5.71 | 78.13 ± 5.81 | 79.30 ± 5.83 | −1.167 | 0.243 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.17 ± 1.40 | 27.73 ± 1.18 | 27.46 ± 1.30 | −1.540 | 0.124 |

| Fat (%) | 36.52 ± 7.55 | 34.80 ± 6.44 | 35.62 ± 6.96 | −1.473 | 0.141 |

| Muscle (kg) | 27.90 ± 3.69 | 28.36 ± 4.62 | 28.14 ± 4.16 | −0.059 | 0.953 |

| Waist/Hip (cm) | 0.97 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | −0.676 | 0.499 |

| Irisin (ng/mL) | 35.81 ± 4.68 | 31.25 ± 7.52 | 33.48 ± 6.65 | −1.989 | 0.052 |

| Insulin (µIU/mL) | 13.02 ± 7.44 | 15.03 ± 9.91 | 14.07 ± 8.77 | −0.707 | 0.479 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 194.90 ± 30.23 | 189.60 ± 27.61 | 192.13 ± 28.67 | −0.955 | 0.340 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 130.18 ± 31.94 | 117.57 ± 27.88 | 123.59 ± 30.21 | −1.237 | 0.216 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 41.67 ± 7.17 | 48.52 ± 15.73 | 45.25 ± 12.75 | −1.167 | 0.243 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 115.21 ± 56.43 | 117.56 ± 51.94 | 116.44 ± 53.50 | −0.507 | 0.612 |

Mann–Whitney U Test.

Table 4.

Changes in anthropometric measurements and irisin levels of participants after the first phase.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | Z | p | Initial | Final | Z | p | |

| X ± SD | X ± SD | X ± SD | X ± SD | |||||

| Weight (kg) | 80.58 ± 5.71 | 77.89 ± 5.82 | −3.781 | 0.000 | 78.13 ± 5.81 | 74.89 ± 5.90 | −4.207 | 0.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.17 ± 1.40 | 26.37 ± 1.75 | −3.400 | 0.001 | 27.73 ± 1.18 | 26.59 ± 1.23 | −4.207 | 0.000 |

| Fat (%) | 36.52 ± 7.55 | 34.17 ± 8.12 | −3.920 | 0.000 | 34.80 ± 6.43 | 32.60 ± 7.06 | −3.996 | 0.000 |

| Muscle (kg) | 27.90 ± 3.69 | 27.82 ± 3.33 | −0.680 | 0.496 | 28.36 ± 4.62 | 28.12 ± 5.04 | −1.268 | 0.205 |

| Waist/Hip | 0.97 ± 0.06 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | −0.606 | 0.544 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | −4.248 | 0.000 |

| Irisin (ng/dL) | 35.81 ± 4.68 | 29.14 ± 7.43 | −4.017 | 0.000 | 31.36 ± 7.52 | 29.77 ± 7.95 | −1.614 | 0.106 |

Wilcoxon Test.

P values shown in bold are significantly different between initial and final at p < 0.05 for group 1 and group 2.

Table 1.

Recommended daily nutrient intake levels of the diet therapy [20].

| Contribution of Macronutrients and Saturated Fat to Energy | |

| Carbohydrate | 45–55% |

| Protein | 12–20% |

| Fat | 20–35% |

| Saturated fat | <7% |

| Recommended Daily Nutrient Intake Levels | |

| Protein | 0.8–1.0 gr/kg/day |

| Cholesterol | <300 mg |

| Fiber | 20–39 gr/day |

Table 5.

Changes in anthropometric measurements and irisin levels of participants after the second phase.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | Z | p | Initial | Final | Z | p | |

| X ± SD | X ± SD | X ± SD | X ± SD | |||||

| Weight (kg) | 77.46 ± 6.04 | 76.57 ± 6.19 | −2.870 | 0.004 | 74.32 ± 5.56 | 73.32 ± 5.90 | −3.027 | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.19 ± 1.79 | 25.89 ± 1.88 | −2.955 | 0.003 | 26.40 ± 1.14 | 26.04 ± 1.36 | −3.052 | 0.002 |

| Fat (%) | 34.78 ± 8.46 | 33.7 ± 8.76 | −3.191 | 0.001 | 33.14 ± 6.79 | 32.67 ± 5.73 | −0.802 | 0.423 |

| Muscle (kg) | 28.22 ± 3.97 | 27.40 ± 3.48 | −2.345 | 0.019 | 27.58 ± 4.65 | 28.23 ± 5.80 | −0.702 | 0.483 |

| Waist/Hip | 0.97 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | −2.114 | 0.035 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | −1.680 | 0.093 |

| Irisin (ng/dL) | 35.40 ± 8.47 | 40.03 ± 5.34 | −1.601 | 0.109 | 28.33 ± 10.37 | 26.92 ± 9.58 | −1.962 | 0.050 |

Wilcoxon Test.

P values shown in bold are significantly different between initial and final at p < 0.05 for group 1 and group 2.

While the mean irisin level of the participants in Group 1 was 35.40 ± 8.47 ng/dL at the beginning of the second phase, that at the end of the second phase was 40.03 ± 5.34 ng/dL. In Group 1, at the end of the second phase, no significant change was observed in the irisin level of the participants after undergoing diet alone (p = 0.109). The mean irisin level of the participants in Group 2 was 28.33 ± 10.37 ng/dL at the beginning of the second phase, while it was 26.92 ± 9.58 ng/dL at the end of the second phase. At the end of the second phase in Group 2, it was revealed that the irisin level of the participants decreased significantly as a result of the intake of coconut oil (p = 0.050). According to the analysis of the food consumption records of the participants in our study, the saturated fat intake was significantly higher during the period of coconut oil intake in both phases (p < 0.05).

The insulin, total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels of all participants decreased significantly at the end of the study. In addition, the change in the participants’ other anthropometric measurements due to weight loss is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Changes in all biochemical findings and anthropometric measurements of participants during the 10-week period (n = 43).

| Initial X ± SD | Final X ± SD | T | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irisin (ng/mL) | 33.48 ± 6.65 | 33.17 ± 10.20 | 0.258 | 0.798 |

| Insulin (µIU/mL) | 14.07 ± 8.77 | 11.04 ± 3.93 | 2.450 | 0.018 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 192.13 ± 28.67 | 169.63 ± 21.58 | 6.922 | 0.000 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 123.59 ± 30.21 | 106.83 ± 22.68 | 6.706 | 0.000 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 45.25 ± 12.75 | 44.97 ± 13.34 | 0.382 | 0.705 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 116.44 ± 53.50 | 89.13 ± 28.41 | 4.823 | 0.000 |

| Weight (kg) | 79.30 ± 5.83 | 74.87 ± 6.19 | 11.521 | 0.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.46 ± 1.31 | 25.97 ± 1.61 | 11.065 | 0.000 |

| Fat (%) | 35.62 ± 6.96 | 33.16 ± 7.26 | 7.355 | 0.000 |

| Muscle (kg) | 28.14 ± 4.16 | 27.83 ± 4.79 | 0.703 | 0.486 |

| Waist/Hip | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 5.269 | 0.000 |

T test.

P values shown in bold are significantly different between initial and final at p < 0.05 for all participants.

Discussion

Coconut oil consists of medium chain fatty acids which directly absorbed from the gastric mucosa, reach the liver via portal circulation, do not require carnitine transferase enzyme to participate in energy metabolism at the cellular level, and are not stored in adipose tissue [22]. Although the BMI levels of both groups receiving coconut oil and undergoing a diet in both phases were significantly reduced, there was no difference in weight changes between them in both phases. Coconut oil has been found to have no superiority in weight loss compared to diet alone. In a clinical study similar to ours with a randomized controlled design, but in which adult males with overweight (n = 29) participated, the participants were divided into two groups. The first group (n = 15) was given 1 teaspoon of coconut oil per day, while the second group (n = 14) was given 1 teaspoon of soybean oil per day. There was no significant difference in the anthropometric measurements between the groups at the end of the study (45 days) [23]. Similarly, another study showed that the BMI level of the participants who had a high intake of coconut oil was also significantly lower than that of the other groups. Coconut oil has been reported to be effective in optimal BMI level [24]. Another study reported that the weight loss was significantly higher in the mice given coconut oil for 8 weeks with oleic acid supplementation compared to the control group [25].

It has been reported that the level of hormone irisin, a myokine secreted after exercise, also changes as a result of dietary interventions. Our study indicated that the irisin level of the groups decreased significantly only when they received coconut oil. It was found that diet therapy did not change irisin level. It has been reported that there are both positive and negative correlations between BMI, fat mass, muscle mass and irisin level, which are among anthropometric measurements [26]. Irisin hormone level was found to be higher in individuals with overweight and obesity compared to healthy individuals [11, 27]. In a meta-analysis study reporting that the irisin hormone is higher in individuals with overweight than in healthy individuals, irisin levels were found to increase due to obesity-related metabolic dysfunction [11]. Studies investigating the effects of different oil types on irisin level are available in the literature, but there is no study investigating the effect of coconut oil on irisin level [28]. Coconut oil is known to support thermogenesis, reducing nutrient intake and promoting weight loss [29]. The hormone irisin has also been found to support thermogenesis in metabolism [30]. In our study, coconut oil intake was found to be associated with levels of irisin hormone. Coconut oil is rich in medium chain fatty acids and contains saturated fat. In addition, according to the analysis of the participants’ food consumption records in both groups in our study, the intake of saturated fat was found to be significantly higher in those who consumed coconut oil compared to those who did not. High saturated fat intake is associated with elevated LDL cholesterol levels, which is a risk factor for coronary heart diseases [31]. A meta-analysis of 16 studies showed that as a result of coconut oil intake for more than two weeks, the LDL cholesterol level of the participants increased by 10.47 mg/dL, while their HDL cholesterol level increased by 4 mg/dL compared to those who consumed vegetable oil [32]. Despite the atherogenic effect of coconut oil, it is thought that it may be protective as it increases the HDL cholesterol level. In an experimental animal study investigating the efficacy of coconut oil in the treatment of hyperlipidemia and hepatic dysfunctions, it was reported that coconut oil increased the level of glutathione peroxidase and had anti-inflammatory effects [33]. In another study, contrary to this one, it was reported that the oxidative stress level increased and myocardial fibrosis levels were also higher at the end of 8 weeks in the mice fed with a diet in which 10% of the fat content consisted of coconut oil. This study indicated that coconut oil might cause cardiomyopathy [34]. Similar to our study, adult females with a high body fat percentage (37.43 ± 0.83) participated in a randomized controlled study with a crossover design. The participants were divided into two groups. One group was given 25 ml of coconut oil at breakfast, while the other group followed an isocaloric balanced diet. In the second phase of the study, coconut oil was given to the group that had not received it, while the group that had received coconut oil in the previous stage was only assigned a balanced diet. At the end of the study, while there was no difference in energy metabolism and cardiometabolic risk factors (total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio, HOMA-IR, resting metabolic rate) [14].

Although the studies revealed the positive effects of coconut oil on weight control, it was not found to be superior to diet therapy in our study. However, coconut oil has been found to be associated with irisin level, and this relationship is thought to be related to metabolic dysfunction developed in individuals with overweight. If coconut oil is to be included in weight control diet therapy, its high content of saturated fat, which is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, should be taken into account.

Strengths of the study:

There are studies in the literature investigating the effect of different oil types on irisin level, but there has been no study investigating the effect of coconut oil on irisin level. Our study is thought to be unique in this context.

While the studies on irisin in the literature were conducted in individuals with overweight, our study was carried out with individuals with a clinical picture that is important in the pre-obesity period and preventable before its development. No studies were found regarding the hormone irisin in individuals with overweight, and our study aims to contribute to the literature in this regard, too.

Limitations of the study:

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the duration of the face-to-face interviews with the participants was kept short. Instead, the nutritional follow-up of the participants was performed through online interviews.

Conclusion

Our study discovered that coconut oil had no effect on anthropometric measurements, which are among the markers of weight loss in individuals with overweight. The relationship of hormone irisin, which was found to be secreted after exercise, with mild obesity and obesity is currently being discussed in the literature. Although there was a change in irisin level due to weight loss in our study, this was not statistically significant. However, coconut oil was found to be associated with the hormone irisin. Both phases of our study revealed that coconut oil reduced the level of hormone irisin in individuals with overweight. In order to prevent obesity, the prevalence of which is increasing in Turkey and around the world, multidisciplinary treatment of individuals with mild obesity should be carried out correctly. Diet therapy, which has an important place in the treatment mild obesity, should be applied based on evidence in line with the recommendations of national and international guidelines. In addition, scientific studies are in progress to include some functional nutrients in diet therapy. More studies are needed to include coconut oil as a functional nutrient in diet therapy.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

Study concept and design: BMK, EYA; acquisition of data: BMK; analysis and interpretation of data: TO; drafting of the manuscript: BMK, TO, EYA; critical revision of the manuscript: EYA; statistical analysis: TO; and study supervision: EYA. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41366-022-01177-1.

References

- 1.Hojlund K, Bostrom P. Irisin in obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2013;27:303–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polyzos SA, Mathew H, Mantzoros CS. Irisin: a true, circulating hormone. Metabolism. 2015;64:1611–8. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y, Pullisaar H, Landin MA, Heyward CA, Schroder M, Geng T, et al. FNDC5/irisin is expressed and regulated differently in human periodontal ligament cells, dental pulp stem cells and osteoblasts. Arch Oral Biol. 2021;124:105061. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2021.105061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espes D, Lau J, Carlsson PO. Increased levels of irisin in people with long-standing Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2015;32:1172–6. doi: 10.1111/dme.12731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faienza MF, Brunetti G, Sanesi L, Colaianni G, Celi M, Piacente L, et al. High irisin levels are associated with better glycemic control and bone health in children with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;141:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong J, Dong Y, Dong Y, Chen F, Mitch WE, Zhang L. Inhibition of myostatin in mice improves insulin sensitivity via irisin-mediated cross talk between muscle and adipose tissues. Int J Obes (Lond) 2016;40:434–42. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H, Zhang Y, Wang F, Donelan W, Zona MC, Li S, et al. Effects of irisin on the differentiation and browning of human visceral white adipocytes. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:7410–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sajoux I, Lorenzo PM, Gomez-Arbelaez D, Zulet MA, Abete I, Castro AI, et al. Effect of a very-low-calorie ketogenic diet on circulating myokine levels compared with the effect of bariatric surgery or a low-calorie diet in patients with obesity. Nutrients. 2019;11:2368. doi: 10.3390/nu11102368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SJ, Tang T, Abbott M, Viscarra JA, Wang Y, Sul HS. AMPK phosphorylates desnutrin/ATGL and hormone-sensitive lipase to regulate lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation within adipose tissue. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36:1961–76. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00244-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzger CE, Narayanan SA, Elizondo JP, Carter AM, Zawieja DC, Hogan HA, et al. DSS-induced colitis produces inflammation-induced bone loss while irisin treatment mitigates the inflammatory state in both gut and bone. Sci Rep. 2019;9:15144. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51550-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia J, Yu F, Wei WP, Yang P, Zhang R, Sheng Y, et al. Relationship between circulating irisin levels and overweight/obesity: a meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:1444–55. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i12.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosy-Westphal A, Muller MJ. Diagnosis of obesity based on body composition-associated health risks-Time for a change in paradigm. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13190. doi: 10.1111/obr.13190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korrapati D, Jeyakumar SM, Putcha UK, Mendu VR, Ponday LR, Acharya V, et al. Coconut oil consumption improves fat-free mass, plasma HDL-cholesterol and insulin sensitivity in healthy men with normal BMI compared to peanut oil. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:2889–99. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valente FX, Candido FG, Lopes LL, Dias DM, Carvalho SDL, Pereira PF, et al. Effects of coconut oil consumption on energy metabolism, cardiometabolic risk markers, and appetitive responses in women with excess body fat. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:1627–37. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panchal SK, Carnahan S, Brown L. Coconut products improve signs of diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2017;72:418–24. doi: 10.1007/s11130-017-0643-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardoso DA, Moreira AS, de Oliveira GM, Raggio Luiz R, Rosa G. A coconut extra virgin oil-rich diet increases Hdl cholesterol and decreases waist circumference and body mass in coronary artery disease patients. Nutr Hosp. 2015;32:2144–52. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.32.5.9642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newell-Fugate AE, Lenz K, Skenandore C, Nowak RA, White BA, Braundmeier-Fleming A. Effects of coconut oil on glycemia, inflammation, and urogenital microbial parameters in female Ossabaw mini-pigs. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ansari S, Djalali M, Mohammadzadeh Honarvar N, Mazaherioun M, Zarei M, Agh F, et al. The effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation on serum irisin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;15:e40614. doi: 10.5812/ijem.40614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hess JM, Fulgoni VL, Radlowski EC. Modeling the impact of adding a serving of dairy foods to the healthy mediterranean-style eating pattern recommended by the 2015-2020 dietary guidelines for Americans. J Am Coll Nutr. 2019;38:59–67. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2018.1485527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeSalvo KB. Public health 3.0: applying the 2015–2020 dietary guidelines for Americans. Public Health Rep. 2016;131:518–21. doi: 10.1177/0033354916662207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yüksel YKİ, Celepkolu T, Toprak G, Aydeniz N, Etik E, Çolpan L. Lipid panelinde Non-HDL kolesterol ve Total kolesterol/HDL kolesterol oranı. Abant Medical J. 2015;4:28–32.

- 22.Clegg ME. They say coconut oil can aid weight loss, but can it really? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:1139–43. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2017.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogel CE, Crovesy L, Rosado EL, Soares-Mota M. Effect of coconut oil on weight loss and metabolic parameters in men with obesity: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Food Funct. 2020;11:6588–94. doi: 10.1039/D0FO00872A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jimaima V, Lako VCN. Coconut oil is associated with a beneficial lipid profile in pre-menopausal women in the Philippines. Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr. 2001;10:188–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-6047.2001.00255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nogoy KMC, Kim HJ, Lee Y, Zhang Y, Yu J, Lee DH, et al. High dietary oleic acid in olive oil-supplemented diet enhanced omega-3 fatty acid in blood plasma of rats. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8:3617–25. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elizondo-Montemayor L, Mendoza-Lara G, Gutierrez-DelBosque G, Peschard-Franco M, Nieblas B, Garcia-Rivas G. Relationship of circulating irisin with body composition, physical activity, and cardiovascular and metabolic disorders in the pediatric population. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3727. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Meneck F, Victorino de Souza L, Oliveira V, do Franco MC. High irisin levels in overweight/obese children and its positive correlation with metabolic profile, blood pressure, and endothelial progenitor cells. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;28:756–64. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira-de-Lira L, Santos EMC, de Souza RF, Matos RJB, Silva MCD, Oliveira LDS, et al. Supplementation-dependent effects of vegetable oils with varying fatty acid compositions on anthropometric and biochemical parameters in obese women. Nutrients. 2018;10:932. doi: 10.3390/nu10070932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman H, Quinn P, Clegg ME. Medium-chain triglycerides and conjugated linoleic acids in beverage form increase satiety and reduce food intake in humans. Nutr Res. 2016;36:526–33. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann T, Elbelt U, Stengel A. Irisin as a muscle-derived hormone stimulating thermogenesis-a critical update. Peptides. 2014;54:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim GB. Coconut oil raises LDL-cholesterol levels. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:200. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neelakantan N, Seah JYH, van Dam RM. The effect of coconut oil consumption on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Circulation. 2020;141:803–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eleazu C, Ekeleme CE, Famurewa A, Mohamed M, Akunna G, David E, et al. Modulation of the lipid profile, hepatic and renal antioxidant activities, and markers of hepatic and renal dysfunctions in alloxan-induced diabetic rats by virgin coconut oil. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2019;19:1032–40. doi: 10.2174/1871530319666190119101058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilayaraja Muthuramu RA, Postnov Andrey, Mishra Mudit, Jacobs Frank, Gheysens Olivier, Van Veldhoven PaulP, et al. Coconut oil aggravates pressure overload-induced cardiomyopathy without inducing obesity, systemic insulin resistance, or cardiac steatosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1565. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.