Abstract

Purpose of review

Firearm injury is the leading mechanism of suicide among US women, and lethal means counseling (LMC) is an evidence-based suicide prevention intervention. We describe current knowledge and research gaps in tailoring LMC to meet the needs of US women.

Recent findings

Available LMC and firearm suicide prevention literature has not fully considered how LMC interventions should be tailored for women. This is especially important as firearm ownership and firearm-related suicides among women are increasing. Additional research is needed to better understand firearm characteristics, behaviors, and beliefs of US women, particularly related to perceptions of personal safety and history of trauma. Research is also needed to identify optimal components of LMC interventions (e.g., messengers, messages, settings) and how best to facilitate safety practices among women with firearm access who are not themselves firearm owners but who reside in households with firearms. Finally, it will be important to examine contextual and individual factors (e.g., rurality, veteran status, intimate partner violence) which may impact LMC preferences and recommendations.

Summary

This commentary offers considerations for applying existing knowledge in LMC and firearm suicide prevention to clinical practice and research among US women, among whom the burden of firearm suicide is increasing.

Keywords: Lethal means counseling, Women, Firearm suicide, Firearm ownership

Introduction

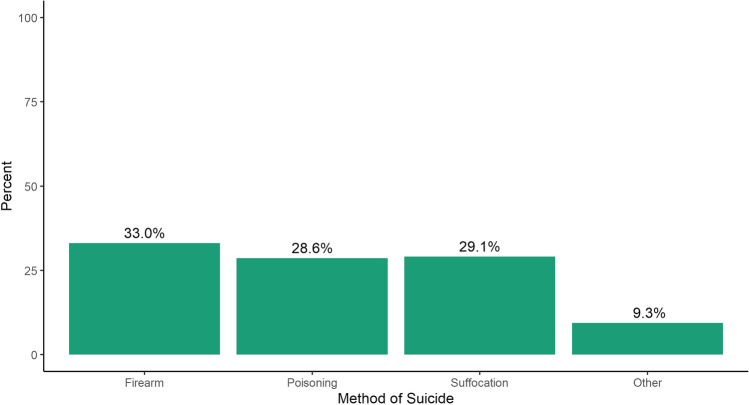

Firearm injury is the leading mechanism of suicide among women in the USA (Fig. 1). In 2020, firearm-related suicides accounted for 3,112 deaths and one-half of all firearm injury deaths among US women [1]. Further, the rate of firearm suicide among women increased by 36% from 2007 to 2019 (1.4 to 1.9 per 100,000) [2]. Access to a household firearms has been consistently shown to be a risk factor for suicide, including among women [3–6]. For example, among women who newly acquired handguns in California from 2004 to 2016, the suicide rate was seven times higher in comparison with women who did not acquire handguns [7•]. Given this relationship, clinical practice and medical society guidelines recommend that clinicians work with patients with elevated suicide risk to identify ways to reduce their firearm access [8, 9••].

Fig. 1.

Suicides among US women in 2020, by method. Data accessed using WISQARS (www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars).

Despite these guidelines and the alarming trends in firearm suicide among US women, extant literature has not considered gender as a central issue and offers little guidance on how clinicians should tailor firearm-related suicide prevention interventions for women. This may partially derive from the finding that most US firearm owners are men and that a portion of relevant research on firearm suicide prevention has focused on military and veteran populations, which are also predominantly male. Nonetheless, many published studies that could inform intervention development have not provided gender-stratified findings, even though many firearm-related studies have enrolled more women than men. In these studies, gender has been included as a covariate (meaning the impact of gender is statistically removed) or has not been considered at all (e.g., not examined as a moderator and not gender-stratified) [10•, 11]. Specific consideration of the influence of gender is needed to develop and deliver gender-tailored clinical care and suicide prevention messaging [12]. Further, this body of literature has varied in terms of whether gender or sex was assessed and whether that distinction was communicated across studies. In this article, we use the term “women” rather than “female,” as we hypothesize that gender is the most relevant construct pertaining to firearm beliefs and behaviors. However, we acknowledge that this term may not uniformly capture what was assessed in each study we cite, which is an important limitation to address in subsequent research.

Firearm Access among US Women

A large proportion of US women are exposed to household firearms. In the 2015 National Firearms Survey, conducted with a nationally representative sample of US adults, 12% of women reported personally owning at least one firearm, and another 20% reported residing in households with firearms present although they did not identify as firearm owners themselves [13••]. Notably, the number of US women with access to firearms has likely increased since then, as women accounted for half of the 3 million US adults who became new firearm owners from 2019 to 2021 [14•]. Reasons for this trend remain unclear. One survey found that most new firearm owners since 2019 reported purchasing firearms for protection against other people [14•]. Possible reasons for the increase in firearm purchases include the impact of electoral politics on firearm purchasing behaviors generally, supply chain concerns related to the global pandemic, and increased concerns regarding personal security due to pandemic-related social tensions, spikes in firearm homicide largely occurring in US urban areas, and responses to national protests for racial justice [15, 16]. Although initial findings indicate that suicide rates have remained stable or decreased through 2020 [17], this trend is nonetheless concerning given increases in other suicide risk factors among women during the COVID-19 pandemic era [18•].

Lethal Means Counseling

Lethal means counseling (LMC) is a clinical intervention whereby clinicians engage patients in discussions about reducing their access to lethal methods of suicide, including firearms. The intent of LMC is to increase the time necessary for an individual with suicidal intent to lethally harm themselves. Ideally, these conversations should take place before a suicidal crisis occurs to reduce the likelihood of injury or death during times of stress or crisis [19]. Common recommendations regarding firearm LMC include but are not limited to (1) removing firearms from the household, (2) storing firearms and ammunitions separately, (3) storing unloaded firearms in a locked safe or container, (4) ensuring firearms are stored with external locking devices (e.g., cable locks), and (5) storing firearms disassembled. Several resources exist to assist providers in facilitating these conversations, such as the Provider Pocket Guide developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense [20] and courses available through the Suicide Prevention Resource Center [21].

Although LMC is an evidence-based suicide prevention practice, clinicians delivering it may face several challenges, including those related to behavioral interventions generally and those related to addressing firearm access specifically. First, for many clinicians, LMC is a new skill that must be learned, and clinicians initially approach this intervention with varying levels of knowledge, skill, and comfort related to counseling itself or firearms generally [22]. These challenges can, in part, be addressed through trainings specific to LMC, on communication skills, and through clinical practice. Second, those who deliver LMC should approach it with an understanding that changing firearm-related behaviors can be challenging. Like many other behaviors which clinicians are tasked with influencing (e.g., tobacco use, diet), firearm behaviors are affected by myriad and varying characteristics which clinicians must be prepared to address. Some firearm owners find deep value in their firearms and firearm culture; effectively delivering LMC necessitates navigating discussions about personal protection, personal and family traditions, culture, sports and hunting, and patient beliefs about privacy and constitutional rights [23–25].

What is Known and What is Needed: Recommendations for Clinical Care and Research

Understanding more about the characteristics of women with household firearm access (through personal ownership or ownership by another household member), as well as their firearm behaviors and perspectives, is critical for developing gender-tailored LMC interventions that are feasible, acceptable, and efficacious. However, little information is available to guide such interventions. This is due to the overall shortage of well-designed studies demonstrating the efficacy of LMC generally [11], as well as the aforementioned lack of consideration of gender as a central issue in this body of research. Nonetheless, the existing literature on firearms and firearm suicide prevention offers some insights into factors relevant to tailoring LMC to women and specific research that may be needed to refine gender-tailored LMC recommendations.

Firearm access, ownership, and storage: On average, women owners tend to own fewer firearms in comparison to men (3.6 vs. 5.6), but are more likely to own handguns (83% vs. 75%), which are more likely to be used in suicide [7•, 13••, 26]. Among women firearm owners, only one in three reports storing all firearms unloaded and locked [13••]. Thus, clinicians must be prepared to engage in lethal means safety discussions with women that address specific firearm types (particularly handguns) and often multiple firearms and firearm types, while considering that most women store firearms in ways that are associated with increased suicide and injury risk for themselves and other household members.

Access without ownership: Another important consideration is that access to a firearm is the risk factor for firearm suicide (not solely ownership), and risk of firearm suicide is elevated among all household members where firearms are present [3]. This presents a unique challenge for clinicians in promoting lethal means safety among women, as 16–20% of US women do not consider themselves owners but report residing in a household with firearms present [13••, 27]. If the individual receiving the intervention is not the firearm owner, it complicates LMC discussions for multiple reasons. First, the recipient of the LMC intervention may not have full autonomy over household firearm storage practices and decisions. Second, they may lack accurate comprehensive knowledge about the number and types of firearms, storage practices, or operation of the firearms. Studies of cohabitating adults who reside in households with firearms have demonstrated a significant gap between owners and non-owners in their knowledge of firearms present and how they are stored [28, 29]. In these situations, clinicians may have to assist in navigating complex household dynamics to identify feasible ways to reduce firearm access. While preliminary studies suggest that some women (e.g., veterans) may find it acceptable or even preferable to engage their partners in firearm-related discussions [30•], this strategy has yet to be tested empirically and should not be assumed to be the case. Further, this approach may be especially challenging when there is concern regarding intimate partner violence; for example, it is critical to understand that women cohabitating with firearm-owning significant others experience a significantly increased risk of homicide [31].

-

Reasons for ownership and safety perspectives: Approximately two-thirds of US firearm owners report that they own firearms for personal protection [26] and that proportion may have increased among purchasers during the pandemic era. Women are more likely than men to report owning firearms for personal protection (73.1% vs. 65.1%) and to own firearms solely for protection (29.5% vs. 16.1%). Perceptions about personal safety play an important role in individuals’ reasons for owning firearms and their firearm safety practices, including storage methods [32, 33•], and are a common reason why patients are hesitant to change firearm ownership or storage practices after LMC. In these scenarios, when patients are hesitant to change their firearm access, motivational interviewing techniques that explore the ambivalence between the perceived benefits of someone’s current firearm practices and their risk of injury may be important. More detailed discussion regarding use of motivational interviewing techniques for firearm lethal means safety can be found in prior published works [34••].

Importantly, women disproportionately experience interpersonal violence [35], and those experiences (and the perceived threat of such experiences happening in the future) likely impact women’s perspectives on the importance of owning firearms and their associated safety practices [30•]. Given that women’s safety perceptions may in part stem from prior experiences of interpersonal trauma (e.g., sexual harassment or sexual assault [18•, 36]), taking a trauma-informed approach to such conversations may be particularly important [37]. This is especially relevant when working with women with a history of intimate partner violence or sexual trauma. For example, cognitive-behavioral techniques might be used to identify underlying beliefs (e.g., “I can only protect myself and/or my children if I am always armed”) that drive firearm behaviors (e.g., carrying or sleeping with a firearm). Then, the clinician and patient can collaboratively explore the validity of these safety-related beliefs and collaboratively identify more realistic beliefs regarding their present reality, as well as alternate behaviors that could serve a similar purpose of increasing perceived safety (see Hoyt et al. for additional discussion and specific examples [24]).

Nonetheless, given how prevalent interpersonal violence experiences are among women and how frequently they are underreported [38], use of a trauma-informed approach when conducting LMC among women may be called for regardless of whether trauma has been disclosed.

The message: To date, we know little about the specific messages that can be incorporated within LMC to effectively promote firearm-related behavior change nor whether or how such messaging should differ by gender. This includes consideration of specific language (e.g., terms such as “fear” and “safety”), recommendations, and resources [25, 39•, 40]. For example, in an undergraduate sample, the term “means safety” was considered more acceptable and preferable than “means restriction” and was also associated with greater reported intentions to limit firearm access. Gender differences were not assessed [41], and this language has not been formally tested within the context of LMC. Nonetheless, this finding emphasizes the import of the specific language used and the necessity of taking a scientific approach to ensuring optimal LMC messaging. Additionally, while a variety of devices and options could be recommended to increase safe storage of household firearms (e.g., cable lock, lockbox, biometric mechanisms), preferences for those options have not been clarified overall or by gender [42]. This is an area in which research is strongly needed to ensure that messaging resonates with women in a manner that impacts behavior.

Messengers, family involvement, partner involvement, and trusted information sources: Trust is an important factor to consider in identifying optimal LMC messengers. The available literature conducted among women Veterans emphasizes trust and rapport as important to facilitating open conversations about firearms and suicide prevention [30•, 43•]. Thus, ensuring that the messenger takes time to establish rapport and build trust is ideal, which may be especially challenging in acute care scenarios. However, given the priority of facilitating lethal means safety among those at risk of suicide, initiating such conversations as trust is established is suggested. LMC can then continue as trust and rapport increase.

Settings: To date, most LMC interventions have been developed for settings in which injury or suicide prevention discussions are expected (e.g., pediatrics, emergency departments, mental health). However, with expansion of suicide prevention initiatives across a variety of clinical settings to reach a broader range of at-risk individuals, LMC discussions are likely to follow in a broader array of settings, including reproductive healthcare settings [36, 44••, 45]. While this expansion is likely to provide additional opportunities to deliver LMC, how such interventions will be received by clinicians, and the acceptability for women receiving counseling in those settings, remains an important area for future research. Additional work is needed to elicit patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives on how LMC can be incorporated into settings providing care for women (e.g., women’s health, obstetrics).

Expecting and working with hesitancy: Firearm behaviors are influenced by a variety of factors, and many Americans find deep social, cultural, and/or practical value in owning and using firearms. As such, clinicians should approach these conversations with reasonable expectations, recognizing that behavior change can take time. Non-judgmental dialogue about factors driving ambivalence, as discussed above within the context of personal protection concerns, can be important for facilitating firearm behavior changes. Prior studies have identified reasons other than suicide prevention for which individuals may store their firearms securely, including injury prevention among other household members (especially children), theft prevention, and safe firearm storage being considered a key tenet of responsible firearm ownership. In some cases, these motivations might be used to facilitate behavior change in parallel with messaging on suicide prevention. How these motivations might apply specifically to women, or whether additional reasons might be leveraged to facilitate LMS discussions, has not been clarified.

Special considerations — high-risk populations: Risk of firearm suicide is elevated among specific subgroups of women, including those residing in rural areas and veterans.

Rurality

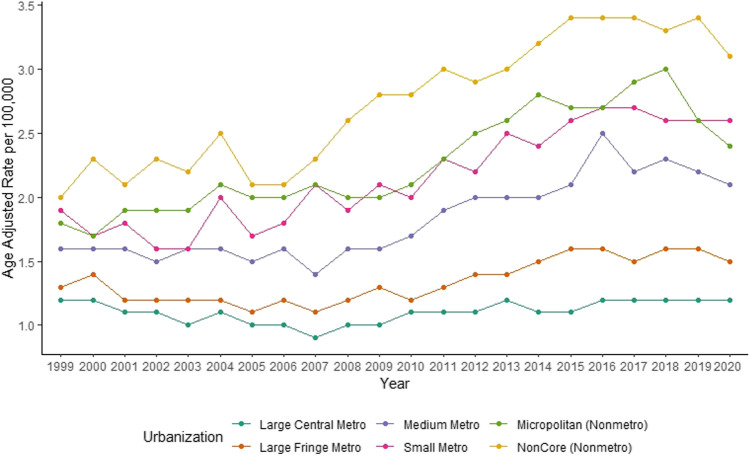

In 2020, the firearm suicide rate among women residing in rural areas was three times that of women residing in urban areas (3.1 versus 1.2 per 100,000) [1]. Furthermore, firearm suicide rates among women have been increasing in more rural areas since 2006 (Fig. 2) [1], and a higher proportion of rural-residing women have access to firearms compared to urban-residing women [13••]. Interestingly, a higher proportion of suburban-residing women live in households with firearms but are not the primary owner compared to both rural- and urban-residing women. These findings highlight the import of understanding differences in risk factors and LMC preferences specific to rurality of residence among women.

Fig. 2.

Firearm suicide rates for females 1999–2020 by 2013 urbanization level. Source: CDC WONDER Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2020(https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html). Urbanization levels defined by National Center of Health Statistics. Metro categories are defined based on population size and inclusion of a principal city as defined by the US Office of Management and Budget. Nonmetro counties (Micropolitan and Noncore) are considered rural. More information is available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm.

Veteran Status

Likewise, firearm injury is a more prevalent method of suicide among women Veterans (49.8% of all suicides in 2019), compared to non-Veteran women (31.3% of all suicides) [46]. Women Veterans are also twice as likely to own firearms compared to non-Veteran women [47]. Given their military training and, in some cases, extensive expertise with firearms [30•], women Veterans’ acquired capability to use a firearm in a suicide attempt may be higher compared to women without military experience [48]. Thus, firearm-related LMC is particularly important for women Veterans. Additionally, specific military experiences, such as gender-based harassment, sexual harassment, and sexual assault during military service, may prompt firearm acquisition and unsafe storage methods among women Veterans [30•, 36] and are extraordinarily common among these populations [49]h; thus, sensitivity to such concerns and consideration of acceptable and feasible ways to promote safety from future interpersonal violence may be critical.

Conclusions

LMC is a recommended practice to prevent firearm suicides [9••], but knowledge to inform optimal strategies among women is lacking. This article provides considerations and suggestions for applying existing knowledge to LMC practices and related research among US women. This includes considering the unique firearm ownership and access patterns among women, how they relate to firearm and safety-related perspectives and beliefs, including those related to personal safety, and the impact of contextual and other sociodemographic characteristics on these factors. Additional work is needed to clarify the ideal messengers, messages, and settings that can be used to increase safety behaviors most effectively among women, and how clinicians can best promote safety practices among women with firearm access who are not themselves owners, or when there is risk of intimate partner violence. Greater engagement of women stakeholders is recommended to guide clinical and research endeavors in such a way that LMC interventions are gender-aware and effective, especially given the increasing rate of firearm suicide among American women. Finally, future research should clearly delineate whether sex and/or gender were assessed to ensure that findings can be extrapolated accordingly.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), specifically the Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) for Suicide Prevention and the Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policy of the VA or the US government.

Declarations

Competing Interest

Drs. Spark and Cogan report no financial interests. Dr. Monteith has received funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs, the American Psychological Association, and the Department of Defense. Dr. Simonetti has received consulting fees from Peraton.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Social Determinants of Health

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NC for HS. Multiple cause of death 1999–2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database. 2021. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html. Accessed 3 Feb 2022.

- 2.Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2019. NCHS Data Brief. 2021:1–8. [PubMed]

- 3.Anglemyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G. The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:101–110. doi: 10.7326/M13-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey JE, Kellermann AL, Somes GW, Banton JG, Rivara FP, Rushforth NP. Risk factors for violent death of women in the home. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:777–782. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440280101009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kung HC, Pearson JL, Liu X. Risk factors for male and female suicide decedents ages 15–64 in the United States. Results from the 1993 National Mortality Followback Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0656-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller M, Swanson SA, Azrael D. Are we missing something pertinent? A bias analysis of unmeasured confounding in the firearm-suicide literature. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38:62–69. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.•.Studdert DM, Zhang Y, Swanson SA, Prince L, Rodden JA, Holsinger EE, Spittal MJ, Wintemute GJ, Miller M. Handgun Ownership and Suicide in California. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2220–2229. Provides the most reliable estimate of firearm suicide risk among women who purchase handguns. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Council on Science and Public Health. American Medical Association. The Physician’s Role in Firearm Safety. 2018.

- 9.••. The Assessment and Management of Suicide Risk Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. Version 2.0. 2019. Comprehensive clinical practice guidelines providing clear, evidence-based recommendations on management of suicidal self-directed violent behavior in patients.

- 10.•. Hunter AA, DiVietro S, Boyer M, Burnham K, Chenard D, Rogers SC. The practice of lethal means restriction counseling in US emergency departments to reduce suicide risk: a systematic review of the literature. Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8:1–7. The only systematic review of LMC interventions among emergency department patients in the U.S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Rowhani-Rahbar A, Simonetti JA, Rivara FP. Effectiveness of Interventions to Promote Safe Firearm Storage. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38:111–124. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton E, Klimes-Dougan B. Gender differences in suicide prevention responses: implications for adolescents based on an illustrative review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:2359. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120302359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.••.Wolfson JA, Azrael D, Miller M. Gun ownership among US women. Inj Prev. 2020;26:49–54. The most comprehensive and valid description of firearm ownership characteristics among US women. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.•.Miller M, Zhang W, Azrael D. Firearm purchasing during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the 2021 National Firearms Survey. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:219–225. One of the few studies that has provided key insights into firearm purchasing behaviors during the pandemc era. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Donnelly MR, Barie PS, Grigorian A, Kuza CM, Schubl S, de Virgilio C, Lekawa M, Nahmias J. New York state and the nation: trends in firearm purchases and firearm violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Surg. 2021;87:690–697. doi: 10.1177/0003134820954827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyons VH, Haviland MJ, Azrael D, Adhia A, Bellenger MA, Ellyson A, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Rivara FP. Firearm purchasing and storage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inj Prev. 2021;27:87–92. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehlman DC, Yard E, Stone DM, Jones CM, Mack KA. Changes in suicide rates — United States, 2019 and 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:306–312. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7108a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.•.Monteith LL, Holliday R, Hoffmire CA. Understanding women’s risk for suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113621. A contemporary and timely review of the dynamic nature of suicide risk factors among women during the pandemic era. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Anestis MD, Bryan CJ, Capron DW, Bryan AO. Lethal means counseling, distribution of cable locks, and safe firearm storage practices among the Mississippi national guard: a factorial randomized controlled trial, 2018–2020. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:309–317. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VA/DoD. The assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. In: VA/DoD Pocket Clin. Pract. Guidel. 2019. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/VADoDSuicideRiskCPGPocketCardFinal5088212019.pdf. Accessed 18 Mar 2022.

- 21.Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Assessing and Managing Suicide Risk: Core Competencies for Mental Health Professionals (AMSR) | Suicide Prevention Resource Center. 2019. https://sprc.org/resources-programs/assessing-managing-suicide-risk-core-competencies-mental-health-professionals. Accessed 18 Mar 2022.

- 22.Roszko PJD, Ameli J, Carter PM, Cunningham RM, Ranney ML. Clinician attitudes, screening practices, and interventions to reduce firearm-related injury. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38:87–110. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards JE, Hohl SD, Segal CD, et al. “What will happen if I say yes?” Perspectives on a standardized firearm access question among adults with depressive symptoms. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:898–904. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoyt T, Holliday R, Simonetti JA, Monteith LL. Firearm lethal means safety with military personnel and veterans: overcoming barriers using a collaborative approach. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2021 doi: 10.1037/PRO0000372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simonetti JA, Holliman BD, Holiday R, Brenner LA, Monteith LL. Firearm-related experiences and perceptions among United States male veterans: a qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE. 2020 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0230135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azrael D, Hepburn L, Hemenway D, Miller M. The stock and flow of U.S. firearms: results from the 2015 National Firearms Survey. RSF Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci. 2017;3:38–57. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaeffer K. Key facts about Americans and guns. In: Pew Res. Cent. 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/09/13/key-facts-about-americans-and-guns/. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

- 28.Azrael D, Miller M, Hemenway D. Are household firearms stored safely? It depends on whom you ask. Pediatrics. 2000;106:e31–e31. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coyne-Beasley T, Baccaglini L, Johnson RM, Webster B, Wiebe DJ. Do partners with children know about firearms in their home? Evidence of a gender gap and implications for practitioners. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e662–e667. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.•.Monteith LL, Holliday R, Dorsey Holliman BA, Brenner LA, Simonetti JA. Understanding female veterans’ experiences and perspectives of firearms. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76:1736–1753. The first study to explore perspectives of firearm suicide prevention efforts among veteran women. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Studdert DM, Zhang Y, Holsinger EE, Prince L, Holsinger AF, Rodden JA, Wintemute GJ, Miller M. Homicide deaths among adult cohabitants of handgun owners in California, 2004 to 2016: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.7326/M21-3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simonetti JA, Azrael D, Miller M. firearm storage practices and risk perceptions among a nationally representative sample of U.S. veterans with and without self-harm risk factors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49:653–664. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.•.Mauri AI, Wolfson JA, Azrael D, Miller M. Firearm storage practices and risk perceptions. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57:830–835. A broad desription of the assocation between risk perceptions and how individual store their firearms among a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.••.Britton PC, Bryan CJ, Valenstein M. Motivational interviewing for means restriction counseling with patients at risk for suicide. 2014. Only work describing use of motivational interviewing for LMC.

- 35.National Organization for Women. Violence against women in the United States: statistics – National Organization for Women. 2022. https://now.org/resource/violence-against-women-in-the-united-states-statistic/. Accessed 21 Mar 2022.

- 36.Monteith L, Holliday R, Miller C, Schneider A, Brenner L, Hoffmire C. Prevalence and correlates of firearm access among Post-9/11 U.S. women veterans using reproductive healthcare: a cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Monteith LL, Holliday R, Dichter ME, Hoffmire CA. Preventing suicide among women veterans: gender-sensitive, trauma-informed conceptualization. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 10.1007/s40501-022-00266-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Gracia E. Unreported cases of domestic violence against women: towards an epidemiology of social silence, tolerance, and inhibition. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:536–537. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.019604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.•.Fuzzell LN, Dodd S, Hu S, Hinnant A, Lee S, Cameron G, Garbutt JM. An informed approach to the development of primary care pediatric firearm safety messages. BMC Pediatr. 2022. 10.1186/S12887-021-03101-4. A contemporary description of an important approach to tailoring LMC messaging for target populations [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Stanley IH, Hom MA, Rogers ML, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. Discussing firearm ownership and access as part of suicide risk assessment and prevention: “means safety” versus “means restriction”. Arch Suicide Res. 2017;21:237–253. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2016.1175395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley IH, Hom MA, Rogers ML, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. Discussing firearm ownership and access as part of suicide risk assessment and prevention: “means safety” versus “means restriction.” 2016;21:237–253. 10.1080/13811118.2016.1175395. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Simonetti JA, Simeona C, Gallagher C, Bennett E, Rivara FP, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Preferences for firearm locking devices and device features among participants in a firearm safety Event. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20:552–556. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.5.42727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.•.Hoffmire CA, Brenner LA, Katon J, Gaeddert LA, Miller CN, Schneider AL, Monteith LL. Women veterans’ perspectives on suicide prevention in reproductive health care settings: an acceptable, desired, unmet opportunity. Womens Health Issues.2022. 10.1016/J.WHI.2022.01.003. An exploration of women veterans’ perspectives on suicide prevention intervention in novel settings. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.••.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4884. Rockville, MD. 2014. Contemporary, expert guidance on delivering trauma-informed care.

- 45.The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gun violence and safety: statement of policy. 2019. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/policy-and-position-statements/statements-of-policy/2019/gun-violence-and-safety. Accessed 23 Mar 2022.

- 46.VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2021 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. 2021.

- 47.Cleveland EC, Azrael D, Simonetti JA, Miller M. Firearm ownership among American veterans: findings from the 2015 national firearm survey. Inj Epidemiol. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s40621-017-0130-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE, Jr, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holliday R, Forster JE, Schneider AL, Miller C, Monteith LL. Interpersonal violence throughout the lifespan: associations with suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among a national sample of female veterans. Med Care. 2021;59:S77–S83. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]