The aging population is a new challenge for healthcare systems. By 2025, the population-aged ≥ 65 years is expected to exceed 30%, and consequently the burden of dementia to increase.[1] Conversely, the growth of geriatricians is far too slow to provide an adequate number of physician specialists to care for the acute needs of the elderly.[2] Geriatric cardiology has led the charge on emerging aspects of cardiovascular (CV) care delivery including patient-centered care, shared decision-making, and palliative care.[3] Epidemiological studies suggest a strong relationship between multiple CV risk factors, heart disease, metabolic syndrome, and dementia.[4,5] In particular, modification or prevention of such vascular and metabolic risk factors and proper management of CV diseases may prevent the development or progression of dementia including Alzheimer’s disease.[6] Dementia is an umbrella term covering different neuropathological features with several progressive clinical stages. People with mild or moderate cognitive impairment might still able to perform themselves in their activities of daily life, especially within some culturally evolved context.[7] Everyone experiences dementia differently and the rate at which symptoms become worse varies from person to person. There is often a lack of awareness and understanding of dementia, resulting in stigmatization and obstacles to diagnosis and care of other acute illnesses.[1] As a higher risk for procedural and other in-hospital complications has been detected in the geriatric population,[8] older adults are less likely to receive evidence-based standard of care. Often quite, age and cognitive impairment represent a double stigma in the healthcare system and a false pretext to exclude the elderly with any kind of cognitive impairment from invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures a priori. Receiving a dementia diagnosis seems like a ‘‘master status’’; ‘‘having dementia’’ not only becomes the most prominent aspect of the person’s life but also serves to overshadow other aspects and pathological conditions that may occur.[9] This issue is old as time but permeates our routinely care delivery. This is unacceptable and it is mandatory to counteract this clinical attitude by fostering the research in this field; however, the elderly population is still under-represented in clinical trials and no evidence on the best approach for the subgroup of patients with cognitive impairment is available.[10] The decision-making is not an easy process, as it needs a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s comorbidities and their physical performance but overall the quality of life that we might ensure for that patient. Personalized treatment does not mean excluding a subject from subsequent treatment just for age or cognitive impairment; it means ensuring on an individual basis the best of care according to the clinical guidelines. Decisions about how to manage older patients with CV ischemic disease generally depend on ischemic and bleeding risks, estimated life expectancy, comorbidities, the need for non-cardiac surgery, quality of life, frailty, cognitive and functional impairment, patient values and preferences, and the estimated risks and benefits of single procedures.[11] To the best of our knowledge, there are no specific decisional aids for clinicians in dementia care that cover multiple topics and not just the aspect closely related to the neurodegenerative process.[12] Moreover, it is fundamental to keep up with the times where cognitive impairment could have different clinical manifestation with different impact case by case. In many healthcare settings, the geriatrician figure is not widely present. Therefore, are people with dementia, especially those in the first stage of the disease, at higher risk of not receiving the best quality of care? Could the inequality risk increase across healthcare organizations in the clinical management of these patients without a geriatric perspective? This is the moment to rethink the misconception idea of dementia: could a dementia diagnosis be the reason for excluding affected people from the right therapeutic approach, especially in CV care, that may preserve them from further neurodegenerative progression? For vulnerable people, clinical guidelines deserve to be viewed from a geriatric perspective. Many predisposing factors for ischemic disease are observed in the geriatric population with a peculiarity: they require a lower threshold for destroying the homeostasis in the “frail phenotype”.[13] Furthermore, an atypical manifestation of acute illnesses is common in geriatric medicine where comorbid conditions represent the “pain distractor”.[14] In contrast with the last decades, recent survival benefit was detected in over 80 years underwent an early invasive strategy when compared to a conservative one, even in non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).[15–17]

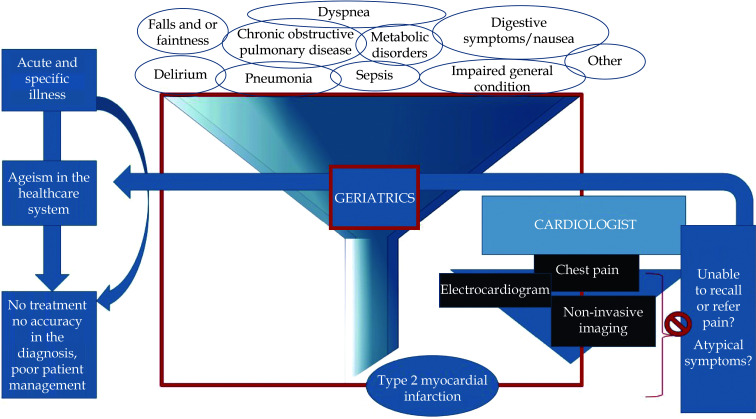

Gonçalves, et al.[18] performed a retrospective study evaluating the impact of coronary angioplasty in elderly patients with NSTEMI. In this study, they compared the results of patients aged ≥ 85 years who underwent coronary angiography. They grouped the population study in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention and in those who underwent optimized medical treatment. History of diabetes mellitus, stroke, and dementia were the baseline clinical characteristics of the optimized medical treatment group.[18] Nevertheless, there was not any reference to the stage of dementia (mild, moderate, or advanced) and it is possible to argue that most of the observational data are prone to selection bias for this vulnerable category of patients. A definitive result about the efficacy of invasive versus medical strategies in people with cognitive impairment and ischemic disease is not possible to achieve yet. As the proportion of older adults is expected to increase, studies are worthy to be conducted in this field. Ischemic events have a more clinical impact on the elderly, as well other CV diseases become more complex with age. Putot, et al.[19] shed the light on the type 2 myocardial infarction (T2MI), which is representing an emerging geriatric disease. T2MI is defined by an increase and decrease in cardiac biomarkers and evidence of ischemia without unstable coronary artery disease, due to a mismatch in myocardial oxygen supply and demand. Myocardial damage is similar but does not meet the clinical criteria for myocardial infarction. Putot, et al.[19] showed a potential diagnostic investigation of elevated cardiac troponin. According to them, “documented ischemia” refers to (1) a subjective statement of retrosternal pain; (2) the electrocardiogram; and (3) non-invasive imaging, respectively. However, this latter tool remains mostly underused in the elderly. The troponin test is important although it should not be routinely ordered. For various causes, pain or evident significant symptoms are not always detectable in the elderly, especially when the altered autonomic peripheral nerve and central mechanisms, sensory neuropathy, and ischemic preconditioning situations coexist.[14] However, the main concern is with people unable to report or remember symptoms. When an elderly patient is admitted to the emergency department, aging very often represents the shield behind which health professionals could hide their prejudicial perspectives. The risk of underestimating a myocardial injury is mainly in the elderly with delirium where it is very difficult to relate the two diseases so far. As an atypical clinical presentation and cognitive decline could affect clinicians’ ability to recognize the acute disease early (in particular myocardial infarction), with a dangerous effect in terms of morbidity and mortality, geriatricians must play a central role in both overall preventive strategy and therapeutic decisions (Figure 1). Novel approaches in clinical research and health systems are necessary to improve shared decision-making for older adults; however, the greatest scope for improvement may be foster interdisciplinary teamwork. Unfortunately, in many hospitals, the geriatric role is marginal or “passive” towards other specialists who settle their decision on the old paradigm where “ageing is the incurable culprit”. Instead, preparing the workforce to work collaboratively in the care of older adults is an essential component of a high-quality standard healthcare system. New horizons in this field should include close cooperation amongst healthcare professionals and researchers, as geriatrics is a living science constantly renewed by emerging diseases and patients’ needs. The practical approach of a geriatric cardiologist consists specifically of this: in making decisions not on age alone but on the whole medical, physical, and cognitive profile of the patients to achieve a sort of individualization, based not just on a given CV diagnosis, but on each patient’s aging experience.[20] Several documents have been prepared to underscore the importance of the frailty assessment and offer tools to measure it in each CV disease situation and establish guidelines on supportive care for elderly patients with CV disease.[21] This approach needs to be modeling also on people with cognitive disorders. An accurate knowledge of cognitive frailty meaning, and its impact on quality of life as well what are the social and personal resource, is worthy to be analyzed in the evaluation of the elderly with acute CV diseases. Finally, geriatrics cardiologist aims to maximize the benefits of patient management and productive clinical time. Considering the improvement of technical procedures in CV care and cultural change toward a dementia-friendly environment,[22] the geriatric cardiology needs to promote slight shifts in the common thinking to better frame cognitive disorders in the CV disease management.

Figure 1.

Myocardial infarction in people with cognitive impairment: the prominent role of geriatric cardiology to avoid the mismanagement of vulnerable older adults.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed June 8, 2022).

- 2.Morley JE The future of geriatrics. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s12603-019-1308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell SP, Orr NM, Dodson JA, et al What to expect from the evolving field of geriatric cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1286–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee H, Kim K, Lee YC, et al Associations between vascular risk factors and subsequent Alzheimer’s disease in older adults. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12:117. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00690-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frisardi V, Solfrizzi V, Seripa D, et al Metabolic-cognitive syndrome: a cross-talk between metabolic syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9:399–417. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frisardi V, Imbimbo BP Metabolic-cognitive syndrome: metabolic approach for the management of Alzheimer’s disease risk. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:S1–S4. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith M, Brown M, Ritchie L, et al Living with dementia in supported housing: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30:e589–e604. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hejazi SF, Iranirad L, Doostali K, et al In-hospital clinical outcomes and procedural complications of percutaneous coronary intervention in elderly patients. Cardiol Res. 2017;8:199–205. doi: 10.14740/cr582e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goffman ER. In Stigma: notes on the management of spoiledidentity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, USA, 1963.

- 10.Vitale C, Fini M, Spoletini I, et al Under-representation of elderly and women in clinical trials. Int J Cardiol. 2017;232:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lettino M, Mascherbauer J, Nordaby M, et al Cardiovascular disease in the elderly: proceedings of the European Society of Cardiology-Cardiovascular Round Table. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;15:zwac033. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwac033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies N, Schiowitz B, Rait G, et al Decision aids to support decision-making in dementia care: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31:1403–1419. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fried LP, Cohen AA, Xue QL, et al The physical frailty syndrome as a transition from homeostatic symphony to cacophony. Nat Aging. 2021;1:36–46. doi: 10.1038/s43587-020-00017-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carro A, Kaski JC Myocardial infarction in the elderly. Aging Dis. 2011;2:116–137. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(72)90290-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang D, Xing YL, Wang H, et al Invasive treatment strategy in patients aged 80 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2022;12:229–240. doi: 10.21037/cdt-21-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sui YG, Teng SY, Qian J, et al Invasive versus conservative strategy in consecutive patients aged 80 years or older with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a retrospective study in China. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2019;16:741–748. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siddiqui AJ, Omerovic E, Holzmann MJ, et al Association of coronary angiographic lesions and mortality in patients over 80 years with NSTEMI. Open Heart. 2022;9:e001811. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2021-001811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonçalves FF, Guimarães JP, Borges SC, et al Impact of coronary angioplasty in elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2020;17:449–454. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Putot A, Putot S, Chagué F, et al New horizons in type 2 myocardial infarction: pathogenesis, assessment and management of an emerging geriatric disease. Age Ageing. 2022;51:afac085. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afac085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Backman WD, Levine SA, Wenger NK, et al Shared decision-making for older adults with cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43:196–204. doi: 10.1002/clc.23267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung KJNC, Wilkinson C, Veerasamy M, et al Frailty scores and their utility in older patients with cardiovascular disease. Interv Cardiol. 2021;16:e05. doi: 10.15420/icr.2020.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inouye SK Creating an anti-ageist healthcare system to improve care for our current and future selves. Nat Aging. 2021;1:150–152. doi: 10.1038/s43587-020-00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]