Abstract

Background

Compelling evidence suggests that glioblastoma (GBM) recurrence results from the expansion of a subset of tumor cells with robust intrinsic or therapy-induced radioresistance. However, the mechanisms underlying GBM radioresistance and recurrence remain elusive. To overcome obstacles in radioresistance research, we present a novel preclinical model ideally suited for radiobiological studies.

Methods

With this model, we performed a screen and identified a radiation-tolerant persister (RTP) subpopulation. RNA sequencing was performed on RTP and parental cells to obtain mRNA and miRNA expression profiles. The regulatory mechanisms among NF-κB, YY1, miR-103a, XRCC3, and FGF2 were investigated by transcription factor activation profiling array analysis, chromatin immunoprecipitation, western blot analysis, luciferase reporter assays, and the MirTrap system. Transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles (Tf-NPs) were employed to improve blood–brain barrier permeability and RTP targeting.

Results

RTP cells drive radioresistance by preferentially activating DNA damage repair and promoting stemness. Mechanistic investigations showed that continual radiation activates the NF-κB signaling cascade and promotes nuclear translocation of p65, leading to enhanced expression of YY1, the transcription factor that directly suppresses miR-103a transcription. Restoring miR-103a expression under these conditions suppressed the FGF2–XRCC3 axis and decreased the radioresistance capability. Moreover, Tf-NPs improved radiosensitivity and provided a significant survival benefit.

Conclusions

We suggest that the NF-κB–YY1–miR-103a regulatory axis is indispensable for the function of RTP cells in driving radioresistance and recurrence. Thus, our results identified a novel strategy for improving survival in patients with recurrent/refractory GBM.

Keywords: DNA damage repair, glioblastoma, glioma stem cell, radioresistance

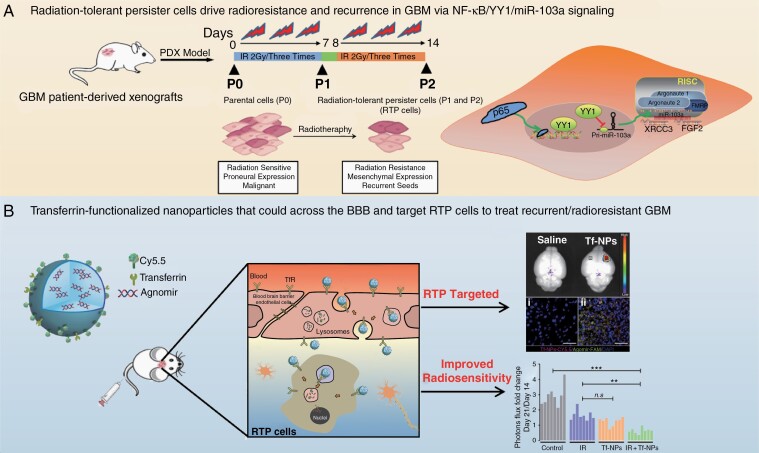

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Key Points.

Radiation-tolerant persister cells drive radioresistance and recurrence in glioblastoma via NF-κB/YY1/miR-103a signaling.

Transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles could cross the blood–brain barrier and target RTP cells to treat recurrent/radioresistant GBM.

Importance of the Study.

In this study, we developed a highly efficient and realistic radioresistant preclinical model ideally suited for radiotherapy studies. We demonstrated that radiation-tolerant persister cells drive radioresistance and recurrence in GBM via NF-κB–YY1–miR-103a signaling. Moreover, our nanoparticle platform could be used as an effective delivery system with a high potential for incorporation in the development of miRNA-based therapeutics for GBM.

Glioblastoma (GBM) ranks among the most lethal solid tumors, and current therapies offer only palliation.1,2 Radiotherapy has been the cornerstone of GBM treatment and remains the common mainstay curative approach in the great majority of patients.3 However, although many GBM patients initially respond to radiotherapy, residual surviving radioresistant cells often result in almost inevitable recurrence.4 Attempts have been made to improve patient outcomes by increasing the radiation dose, with the consequence of exposing healthy cells to dose levels exceeding their tolerance limit.5 A more efficient strategy is to suppress or overcome the mechanisms underlying radioresistance acquired during radiotherapy.

Repopulation by surviving tumor cells during fractionated radiation therapy limits the efficacy of radiotherapy and is the major cause of radiotherapy failure.6 Compelling evidence suggests that GBM recurrence results from the expansion of a subset of tumor cells with robust intrinsic or therapy-induced radioresistance.7 As an intrinsic heterogeneous subpopulation in GBM, glioma stem cells (GSCs) can maintain or enhance intrinsic cellular features that contribute to the development of radioresistance.8 Pools of cells with therapy-induced radioresistance display complicated clonal dynamics in which genetically distinct subclones acquire variable serial repopulating activity in vivo.9 A pool of these cells can survive exogenous DNA damage through preferential activation of the DNA damage checkpoint response, efficient DNA repair machinery activity, and escape from apoptosis, thereby contributing to radioresistance and recurrence.10 The DNA damage response (DDR) is a multistep process that includes damage sensing, signal transduction to repair complexes, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis induction.11 To circumvent the injurious effects of DNA damage, cells activate a highly coordinated DDR network in a timely manner to repair damaged DNA.12 Ionizing radiation usually produces a wide variety of DNA lesions, including double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are considered to be the major factor responsible for cell death.13 Two main pathways are involved in DSB repair: homologous recombination (HR) and nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ).14 HR occurs mainly during the S-G2 phases; in contrast, G0-arrested cells, in which HR is inactive, rely predominantly on NHEJ.

Gradual accumulation of particular genetic alterations is clearly a driving force for tumor progression and may also control resistance or sensitivity to radiotherapy.15 Traditionally, preclinical studies of radioresistance are performed using tumor cell lines that have been selected and maintained in cell culture for many years. Thus, the genetic and morphologic characteristics of tumors derived from these cells often do not accurately reflect those typically found in primary human tumors.16 To overcome obstacles in radioresistance research posed by limitations of the current in vitro and in vivo models, we established a preclinical radioresistant model utilizing patient-derived xenografts (PDXs). With this model, we performed a screen and identified a radiation-tolerant persister (RTP) subpopulation with high radioresistance and investigated the mechanisms by which cell state heterogeneity and plasticity contribute to the generation of RTP cells. The RTP cell pool constitutes a reservoir from which radioresistant tumors may develop. Mechanistic investigations showed that the NF-κB–YY1–miR-103a regulatory axis is indispensable for the function of RTP cells in driving radioresistance and recurrence. In addition, we developed transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles (Tf-NPs) that can deliver a miR-103a agomir to RTP orthotopic xenograft-bearing mice. As expected, Tf-NPs treatment combined with radiotherapy markedly decreased the tumor burden and prolonged survival. These findings advanced our understanding of the role of RTP cells in GBM radioresistance and recurrence and suggested that RTP-targeted drugs in combination with radiotherapy might be a novel effective strategy for GBM treatment.

Materials and Methods

Primary Cultures and Cells

Human tissues were obtained following written informed consent from patients in accordance with the Ethics Committee of Fourth Military Medical University. Data regarding cell lines and culture are included in Supplementary Methods.

HR and NHEJ Assay

Reporter plasmids were established to assess HR and NHEJ efficacy (see Supplementary Methods for details).

Oris 3D Embedded Invasion and Oris Migration Assay

Cells (5 × 104) were seeded into wells of the Oris Cell migration assembly kit and invasion assay kit (Platypus Technologies), and assays were conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, see Supplementary Methods for details.

In vitro Limiting Dilution Assay

Dissociated cells from GBM spheres were seeded in 96-well plates containing GSC culture medium. After 7 days, each well was examined for the formation of tumorspheres (see Supplementary Methods for details).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Frozen sections were fixed with chilled acetone for 20 min and blocked with 2% horse serum for 1 h at room temperature. Cultured cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C.

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins were separated by electrophoresis on 4–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. The primary antibodies are listed in Supplementary Materials.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation and PCR

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol, as described in Supplementary Methods.

Single-Cell Gel Electrophoresis Comet Assay

The comet assay was performed using an OxiSelect Comet Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (see Supplementary Methods for details).

In Vivo Assays

The establishment of the PDX model and intracranial xenograft experimental procedures are available in Supplementary Methods. Detailed patient information is presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Flow Cytometry

Further information is available in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Preparation of Nanoparticles

Further information is available in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM values. Student’s t-test, the log-rank test, or one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used. All statistical analyses of data were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Kaplan–Meier curves were generated using GraphPad Prism 7 software, and the log-rank test was performed.

Results

The RTP Subset Correlates With Radioresistance and Recurrence in the Preclinical Model

To overcome obstacles in radiotherapy research posed by limitations of the current in vitro and in vivo models, we established a preclinical radioresistant PDX model by using X-ray irradiation (IR) to identify a cell subpopulation that mediated radioresistance and recurrence (Figure 1A). The radioresistant P2 population was confirmed by comparing survival fractions under different radiation doses (Supplementary Figure 1A and B). Notably, the migration and invasion of P2 cells were dramatically enhanced (Supplementary Figure 1C). Tumors in patients with the mesenchymal (MES) subtype of GBM often exhibit radioresistance-associated properties such as increased invasiveness and reduced cell stiffness, and these patients have a worse prognosis than those with proneural (PN) tumors.17 Specifically, data from the preclinical model demonstrated that a PN-to-MES phenotypic shift was elicited in GBM cells subjected to radiotherapy (Supplementary Figure 1D). Based on the above biological properties of the radioresistant subpopulation, we designated this subpopulation, which could sustainably tolerate radiation damage and possessed a relatively aggressive phenotype, RTP cells (Figure 1B). Targeting RTP cells, therefore, presents a unique opportunity to inhibit the development of radioresistance and recurrence.

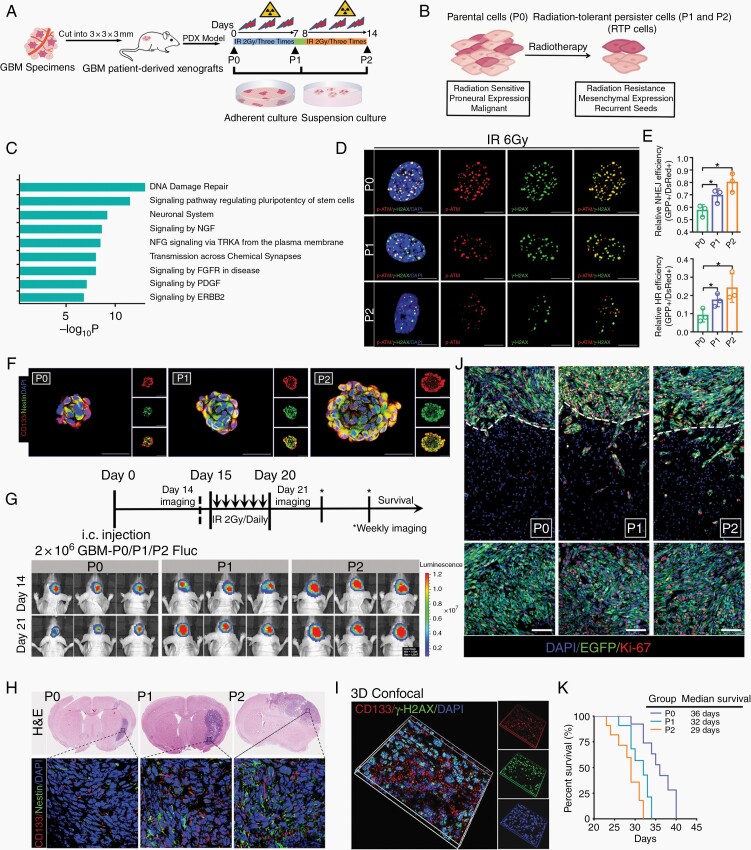

Fig. 1.

The preclinical radioresistant PDX model enabled the characterization of radioresistance associated with recurrence. (A) Establishment of the preclinical radioresistant PDX model by using X-ray irradiation. (B) Biological properties of RTP cells. (C) Gene ontology analysis of all genes specifically altered in RTP cells. (D) Colocalization of IR-induced (IRI) p-ATM/γ-H2AX-positive DNA damage foci 12 h after IR treatment. Scale bar: 10 μm. (E) Analysis of HR and NHEJ efficiency in P0, P1, and P2 cells by counting green versus red fluorescence puncta. (F) Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of GSC spheroids cultured under stem cell conditions with the indicated antibodies. Scale bar: 50 μm. (G) Schematic diagram of P2 cell-derived xenografts. (H) Coronal sections of mouse brains were harvested on day 21 after injection. (I) IF staining of intracranial EGFP-labeled tumors for Ki-67 and DAPI to visualize the core and invasive areas. Scale bar: 100 μm. (J) 3D confocal microscopy of CD133 and γ-H2AX expression and distribution. (K) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of xenograft tumor-bearing mice.

To elucidate the role of RTP cells in radioresistance, we first analyzed the transcriptional program of these cells. Gene ontology (GO) analysis showed that DNA damage repair and GSC stemness pathway-related genes were markedly upregulated in P2 cells (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure 1E), indicating that DDR activation and enhanced stemness are crucial in RTP cells. γ-H2AX/p-ATM foci remained stable in the parental P0 cells, but were greatly reduced in number in P2 cells, suggesting that this radioresistant subset had an enhanced ability for DSB repair (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure 1F). Moreover, the efficiency of both HR and NHEJ was greatly increased in P2 cells (Figure 1E and Supplementary Figure 1G). Accumulating evidence indicates that GSCs play pivotal roles in multitherapy resistance in GBM.18 Therefore, cells isolated from the radioresistant PDX model were analyzed, and the results showed that the number of CD133 and Nestin double-positive cells was increased (Supplementary Figure 2A and B). Consistent with this finding, spheroid staining showed relatively strong expression of stemness markers in RTP cells (Figure 1F). Moreover, the proportion of sphere-forming units was greatly increased among RTP cells, indicating enhanced GSC generation and self-renewal capabilities (Supplementary Figure 2C and D). Collectively, these data indicated that GSCs were induced and resided in the RTP subpopulation.

To further confirm that RTP cells indeed play essential roles in tumorigenesis, radioresistance, and recurrence, P0, P1, and P2 cells were intracranially injected into mice. Bioluminescence imaging suggested that all mice developed tumors, with the largest tumors observed in the P2 group (Figure 1G). Subsequently, these tumor-bearing mice were subjected to brain IR with 6 cycles of 2 Gy on consecutive days (days 15–20) to mimic the clinical radiotherapy regimen for GBM. As expected, radiotherapy markedly suppressed intracranial tumor growth in P0 group mice, but no apparent therapeutic effect was observed in P2 group mice (Supplementary Figure 2E and F). However, the P0 group mice were clinically asymptomatic, and only small tumors were found in their right hemispheres. Analysis of brain sections indicated increased expression of GSC markers in P1 and P2 group mice (Figure 1H). In addition, fewer DSBs were found in the CD133+ cells (Figure 1I). Compared with the P0 tumors, the P2 tumors grew rapidly, and some invasive tumor cell clusters (ki-67+/EGFP+) disseminated extensively deep into the brain parenchyma and migrated beyond the tumor core (Figure 1J and Supplementary Figure 2G). Kaplan–Meier analysis showed a significant decrease in overall survival after orthotopic intracranial engraftment of RTP cells compared with P0 cells (Figure 1K). Taken together, these results suggested that RTP cells drive radioresistance and recurrence in GBM.

The RTP Subpopulation Exerts its Effects in a miR-103a-Dependent Manner

To clarify the mechanism underlying RTP cell generation, we performed genome-wide miRNA expression profiling to compare P0 and P2 tumors (Figure 2A), followed by functional screening with a soft agar assay. The long-term colony formation potential was partially abolished by miR-99a, miR-196a, miR-153, and miR-103a. Among these miRNAs, ad-miR-103a had the best inhibitory effect (Supplementary Figure 3A). Previous studies showed that miR-103a is highly expressed in most tumors19; however, data from starBase demonstrated that miR-103a expression is repressed in GBM patients (Supplementary Figure 3B and C). In 38 paired GBM and adjacent nontumor tissue specimens, miR-103a was differentially expressed between the GBM and nontumor tissue in the individuals evaluated, but a greatly decreased level was more common in the GBM tissues than in the normal tissues (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 3D), possibly because of the heterogeneity of GBM cells. miR-103a was significantly downregulated in the overwhelming majority of the P2 PDX and radioresistant xenograft tumors, in which most tumor cells were homogeneous RTP cells (Figure 2C). Interestingly, miR-103a expression was negatively correlated with ALDH1A3 and CD44 expression in GBM tissues, implying that the repression of miR-103a expression in GBM promotes advanced malignancy (Supplementary Figure 3E). Overexpression of miR-103a in P2 cells sensitized these cells to radiation, whereas silencing miR-103a in P0 cells conferred radioresistance on these cells (Supplementary Figure 3F).

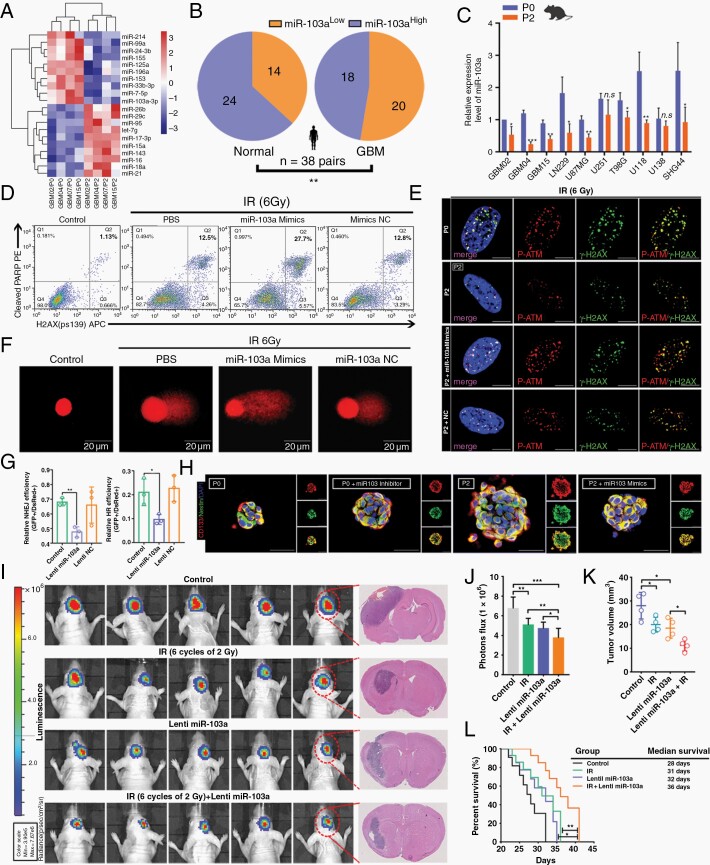

Fig. 2.

miR-103a is closely linked with the GSC properties and radioresistance of RTP cells. (A) Hierarchical clustering of 20 differentially expressed miRNAs in P0 tumors and the corresponding P2 tumors. (B) Pie charts showing the distribution of miR-103aLow and miR-103aHigh expression in normal and GBM tissues. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of miR-103a expression in radioresistant models. (D) FACS analysis of γ-H2AX and cleaved PARP-1 staining in irradiated P2 cells. (E) Colocalization of IRI p-ATM/γ-H2AX-positive DNA damage foci. Scale bar: 10 μm. (F) The presence of DNA damage after exposure to 6 Gy IR was assessed by a single-cell gel electrophoresis comet assay. (G) Effects of miR-103a on HR and NHEJ. (H) Immunofluorescence analysis of GSC spheroids. Scale bar: 50 μm. (I) Representative H&E staining of coronal sections harvested 21 days after transplantation. (J) Statistical analysis of orthotopic tumor growth as measured by luciferase activity over time. (K) Quantification of tumor sizes. (L) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of mice bearing P0 cell-derived xenografts treated as indicated.

Next, we investigated the physiological role of miR-103a in RTP cells. We further demonstrated that the numbers of γ-H2AX+/cleaved PARP-1+ cells were increased after transfection of the miR-103a mimic into irradiated cells (Figure 2D). Moreover, γ-H2AX/p-ATM foci persisted longer in miR-103a-overexpressing P2 cells, indicating that the ability to repair DNA lesions was reduced in these miR-103a-overexpressing cells (Figure 2E and Supplementary Figure 3G). P2 cells overexpressing miR-103a had significantly higher residual DNA damage, as assessed by the Olive tail moment, tail DNA %, and tail length values (Figure 2F and Supplementary Figure 3H). Furthermore, overexpression of miR-103a significantly impaired DSB repair by both HR and NHEJ (Figure 2G and Supplementary Figure 3I).

In contrast to that of other GSC markers, miR-103a expression was specifically decreased in spheres composed of GSCs compared with those composed of parental adherent cells, and reduced miR-103a expression was also observed in CD44+ or CD133+ cell populations compared with CD44− or CD133− cell subsets (Supplementary Figure 3J). Subsequently, we demonstrated that ectopic expression of miR-103a significantly reduced GSC tumorsphere formation (Supplementary Figure 3K). Moreover, elevated miR-103a expression resulted in a decrease in stemness (Figure 2H and Supplementary Figure 3L). As expected, combination treatment with radiotherapy and Lenti-miR-103a transduction showed significantly increased antitumor activity compared to either monotherapy (Figure 2I–L). Overall, these data indicated that miR-103a mediates the function of RTP cells through the DDR pathway and the regulation of GSC stemness.

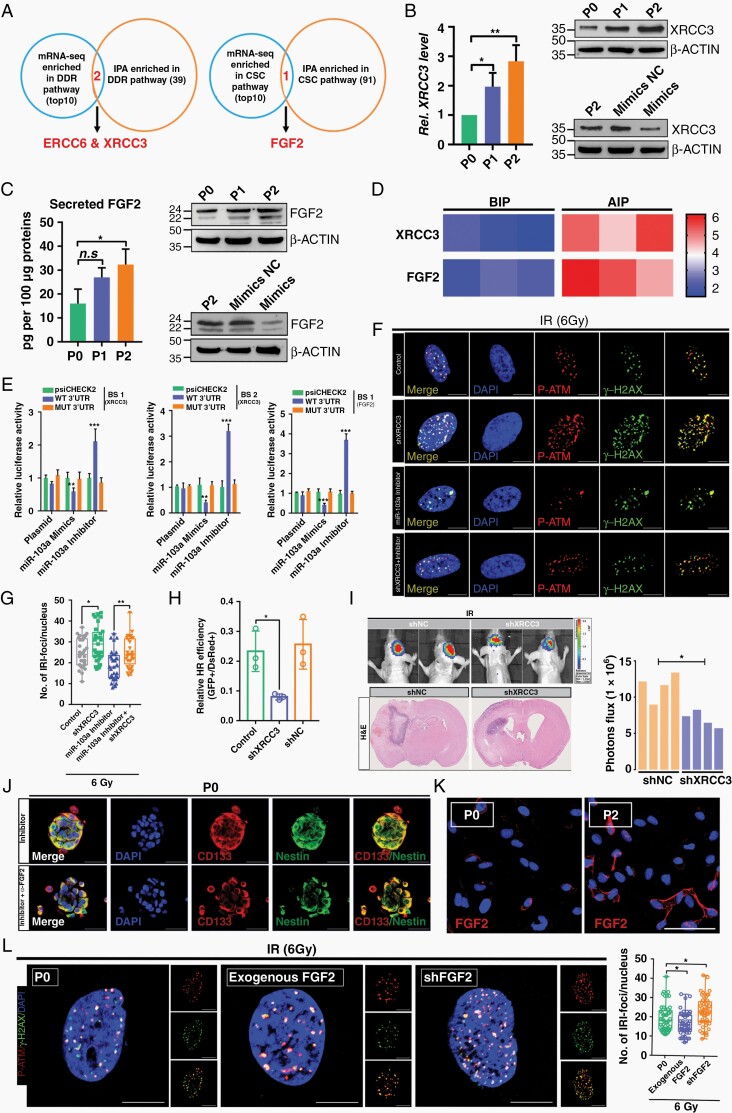

Targeted induction of XRCC3 and FGF2 by miR-103a Directly Regulates the DDR and Stemness

To identify miR-103a-mediated downstream regulators related to DNA damage repair and GSC properties in RTP cells, 3 target prediction algorithms (miRanda, miRWalk, and TargetScan) were applied. The 1286 targets identified by the algorithms were further subjected to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Consistent with our findings, both the DDR pathway and signaling pathways regulating the pluripotency of stem cells were among the major canonical pathways identified. Among the genes identified, ERCC6, XRCC3, and FGF2 best matched our prediction of direct activity in RTP cells (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 4A). We confirmed that XRCC3 and FGF2 were obviously upregulated in RTP cells and downregulated in miR-103a-overexpressing cells (Figure 3B and C). By using the miRNA Target IP system, we further confirmed that XRCC3 and FGF2 were significantly enriched after IP of P0 cells cotransfected with miR-103a and the pMirTrap vector (Figure 3D and Supplementary Figure 4B). miR-103a mimic markedly decreased the luciferase activity of the wild-type reporter but barely affected that of the mutant reporter (Figure 3E and Supplementary Figure 4C).

Fig. 3.

The miR-103a–XRCC3–FGF2 axis is functionally important for regulating DDR and GSC properties in RTP cells. (A) Target genes of miR-103a were identified by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis and RNA-seq. (B) Relative XRCC3 mRNA and protein expression in GBM cells subjected to different treatments. (C) Changes in the secretory FGF2 level in P2 cells compared to P0 cells, as evaluated by ELISA. The FGF2 protein level was assessed by WB analysis. (D) Heatmap represents fold enrichment before and after immunoprecipitation (BIP/AIP) using the RT2 profiler PCR array system. (E) Luciferase activity of psiCHECK2-XRCC3 and psiCHECK2-FGF2 in P0 cells after cotransfection with miR-103a. (F and G) p-ATM colocalized with γ-H2AX after DNA damage. Scale bar: 10 μm. (H) Efficiency of HR in P2 cells treated with or without shXRCC3. (I) Representative bioluminescence and H&E images of shNC- or shXRCC3-expressing P2 cells injected intracranially into nude mice. (J) Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of GSC spheroids. Scale bar: 50 μm. (K) IF staining of FGF2 in P0 and P2 cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. (L) Quantification of IRI p-ATM/γ-H2AX-positive DNA damage foci treated with exogenous FGF2 or shFGF2. Scale bar: 10 μm.

To determine whether XRCC3 directly mediates miR-103a-regulated DSB repair, XRCC3 was knocked down in P2 cells, and these P2 cells were greatly radiosensitized (Supplementary Figure 4D and E). In addition, the miR-103a silencing-induced reduction in γ-H2AX/p-ATM foci was greatly reversed by XRCC3 knockdown (Figure 3F and G). Collectively, these data demonstrated that at least some aspects of DNA damage repair regulated by miR-103a are dependent on XRCC3. Further studies showed that XRCC3 knockdown greatly increased the amount of unrepaired damaged DNA and that XRCC3 promoted DSB repair through an HR-dependent pathway (Figure 3H and Supplementary Figure 4F and G). Moreover, we showed that knockdown of XRCC3 significantly increased the radiosensitivity of P2 cell-derived orthotopic xenografts (Figure 3I). Collectively, these findings suggested that the miR-103a–XRCC3 axis performs a DNA damage repair function in RTP cells.

The particular role that FGF2 plays in GSC has recently been explored.20,21 We sought to determine whether miR-103a-targeted FGF2 confers a stemness phenotype on RTP cells. P2 cells treated with an anti-FGF2 neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb) exhibited a markedly lower self-renewal capacity than the parental P2 cells and hence were estimated to have a lower stem cell frequency (Supplementary Figure 4H–J). In RTP cells, the miR-103a inhibitor-induced GSC properties were apparently reversed by treatment with the anti-FGF2 neutralizing mAb (Figure 3J). Notably, the amounts of both the nuclear (22, 22.5, and 24 kDa) and cytosolic (18 kDa) FGF2 isoforms were increased in P2 cells in this model (Figure 3K). However, the functions of nuclear FGF2 in cancer cells remain poorly understood. Our research showed that knockdown of both isoforms of FGF2 greatly impaired the DNA damage repair ability of P2 cells, while the numbers of DSB foci in P2 cells were reduced in the presence of exogenous recombinant FGF2 (18 kDa) (Figure 3L and Supplementary Figure 4K). Further investigation confirmed that FGF2 performs its function in an NHEJ-dependent manner (Supplementary Figure 4L). Taken together, these data suggested that miR-103a suppresses stemness in the RTP subset by targeting FGF2, which is downstream of miR-103a and involved in DNA damage repair in RTP cells via the NHEJ pathway.

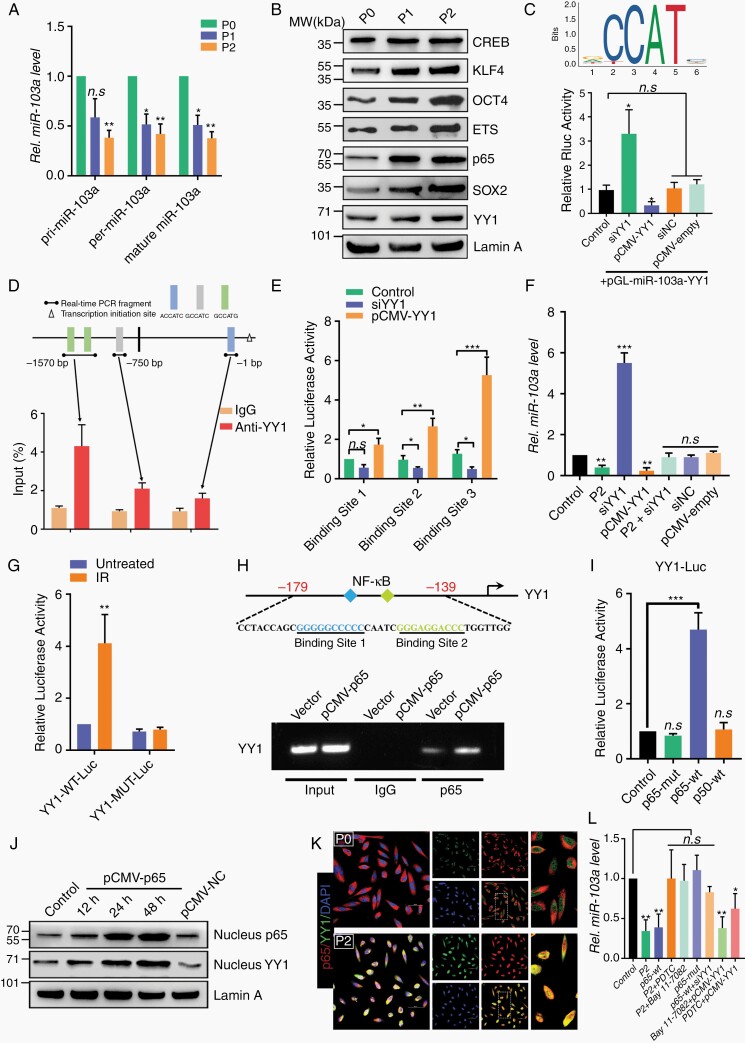

The NF-κB–YY1 Axis Transcriptionally Regulates the miR-103a Level in RTP Cells

To ascertain the possible mechanisms of miR-103a dysregulation in our model, the expression levels of primary, precursor, and mature miR-103a were measured. As shown in Figure 4A, the levels of pri-miR-103a, pre-miR-103a, and mature miR-103a were decreased in P2 cells compared with P0 cells, suggesting that endogenous miR-103a was downregulated by changes in de novo synthesis. First, epigenetic analysis revealed that the methylation level of the miR-103a promoter region was not significantly different between P0 and P2 cells (Supplementary Figure 5A–C). Then, we performed a transcription factor (TF) screen using a TF activation profiling array (Supplementary Figure 5D). Enrichment of CREB, KLF4, OCT4, ETS, p65, SOX2, and YY1 in P2 cells was apparently greater than that in P0 cells (Figure 4B). In addition, bioinformatic analysis showed the presence of 4 YY1-binding elements in the promoter of miR-103a. A subsequent luciferase reporter assay confirmed that ectopic expression of YY1 in P2 cells induced reproducible, significant miR-103a promoter-driven repression of the luciferase reporter (Figure 4C). To test whether YY1 directly interacts with the miR-103a promoter under physiological conditions, ChIP assays were performed. As shown in Figure 4D, since several potential YY1-binding motifs were proximal to each other, our primers flanked the outermost regions of the adjacent sites. The anti-YY1 antibody pulled down more miR-103a promoter DNA than the IgG control, and the highest signal was located 1.5 kb upstream (at the 5′ end) of the transcription start site (Figure 4E). In addition, knockdown of YY1 almost completely abolished the regulation of miR-103a by radiation in P2 cells (Figure 4F). Taken together, these experiments firmly established miR-103a as a YY1-specific target gene in RTP cells. However, to date, whether YY1 plays a pathophysiological role in radiotherapy remains undetermined. By using the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas database, we found that in both primary glioma and recurrent glioma, patients with high YY1 levels had a much worse survival probability than those with low YY1 levels (Supplementary Figure 6A). More importantly, our research also confirmed that knockdown of YY1 significantly increased the radiosensitivity of P2 cell-derived orthotopic brain xenografts (Supplementary Figure 6B–E).

Fig. 4.

The NF-κB–YY1 axis transcriptionally regulates miR-103a in RTP cells. (A) Expression profiles of pri-, pre-, and mature miR-103a in P0, P1, and P2 cells. (B) Western blot analysis of CREB, KLF4, OCT4, ETS, p65, YY1, LaminA, and SOX2. (C) The JASPAR database was used to predict the TF binding sites. P2 cells were transfected with the pGLmiR-103a-YY1 luciferase reporter vector. (D) Top: schematic diagrams of the regions amplified by the ChIP primers. Bottom: amounts of DNA precipitated by the anti-YY1 antibody and control IgG. (E) P2 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter vectors containing the miR-103a promoter region. (F) miR-103a expression level was determined by qRT-PCR. (G) P0 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter vectors containing the wild-type or mutant YY1 promoter region and were then treated with or without IR. (H) Schematic illustration of the YY1 promoter containing 2 putative NF-κB consensus binding sequences. ChIP analysis was used to detect the direct binding of p65 to the YY1 promoter. (I) P0 cells were transiently transfected with the YY1-Luc reporter plasmid alone or in combination with the indicated p65 or p50 expression plasmid. (J) P0 cells were transfected with pCMV-p65, and the expression levels of p65 and YY1 were determined by WB. (K) The distribution and expression of p65 and YY1 in P0 and P2 cells were evaluated by immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar: 50 μm. (L) The effect of the NF-kB–YY1 axis on miR-103a expression was detected by qRT-PCR.

We then sought to determine the mechanism by which YY1 is upregulated in P2 cells. A luciferase reporter assay showed that YY1 promoter activity was significantly enhanced by IR (Figure 4G), indicating that radiation accelerates YY1 transcription. We then analyzed the YY1 proximal promoter by bioinformatic approaches, and 2 motifs with similarities to the NF-κB consensus site were found. We referred to these motifs, located at positions 170 and 153 relative to the transcription start site, as BS1 (GGGGGCCCCC) and BS2 (GGAGGACCCT), respectively. Chromatin isolated from the vector and pCMV-p65 groups was immunoprecipitated, and p65 was found to interact strongly with the YY1 promoter in the pCMV-p65 group but weakly in the vector control group (Figure 4H). Moreover, an 800-bp fragment corresponding to the promoter region of the YY1 gene was amplified and subcloned into a pGL3-luciferase reporter plasmid. Cotransfection of this plasmid with different NF-κB subunits into P2 cells showed that the YY1 promoter element could be activated by p65 but not p50 (Figure 4I). Interestingly, in P0 cells transfected with pCMV-p65, both the expression and nuclear distribution of YY1 were greatly increased (Figure 4J). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that long-term radiotherapy led to p65 nuclear translocation and hence promoted the expression of YY1 (Figure 4K). Blockade of NF-κB activation notably reversed the repression of miR-103a expression induced by long-term radiotherapy. Consistent with this result, the regulatory effect of transfected p65 on miR-103a was absent in P0 cells treated with YY1-specific siRNA (Figure 4L). These data suggested that long-term radiotherapy downregulates miR-103a expression in an NF-κB–YY1 axis-dependent manner and that RTP cells exert their effects via the NF-κB–YY1–miR-103a regulatory axis.

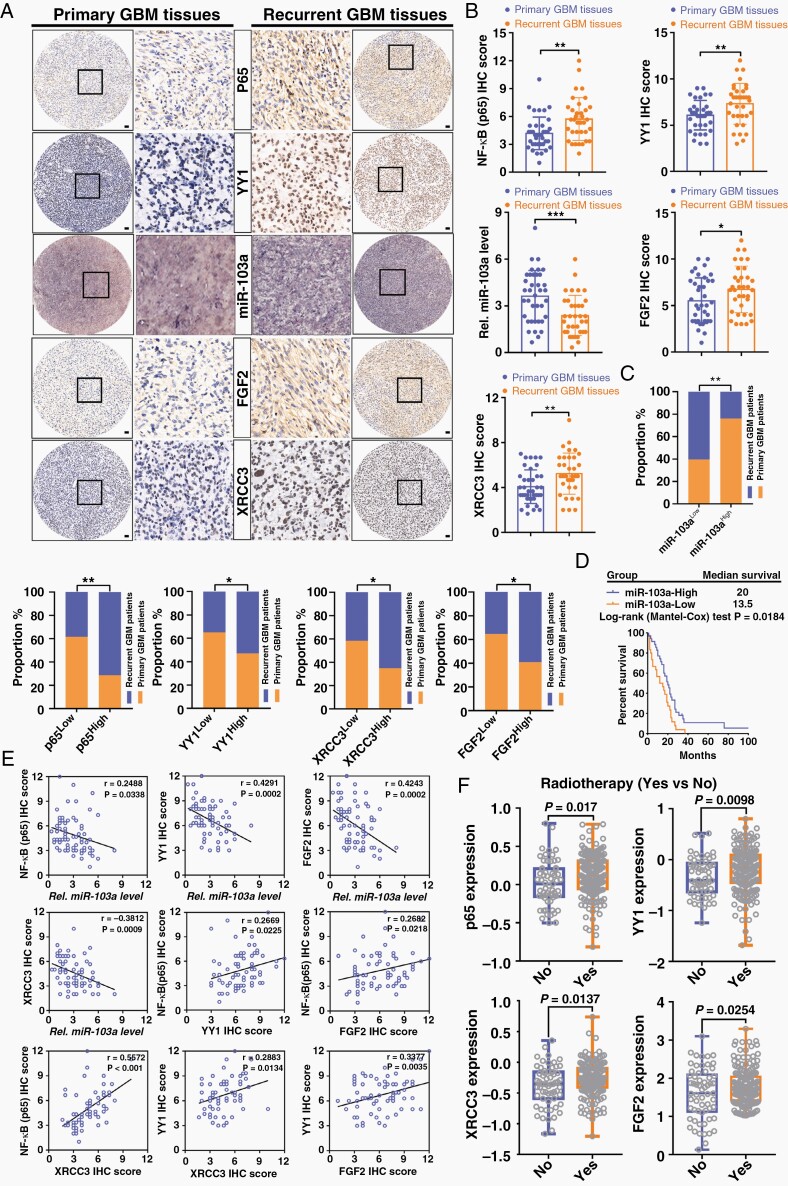

The NF-κB–YY1–miR-103a Axis Is Clinically Associated With Recurrence and Predicts the Radiotherapy Response in GBM Patients

To determine whether our above findings in RTP cells are clinically relevant, we evaluated the levels of miR-103a, p65, YY1, FGF2, and XRCC3 in 38 primary GBM tumors and 35 recurrent GBM tumors. The recurrent specimens exhibited significantly higher p65, YY1, FGF2, and XRCC3 staining intensities than the primary specimens, and conversely, miR-103a staining was reduced in the recurrent specimens (Figure 5A and B). High levels of p65, YY1, FGF2, and XRCC3 expression were significantly associated with tumor recurrence in patients with GBM, and the opposite trend was found for miR-103a expression (Figure 5C). Furthermore, we performed in situ hybridization with a tissue microarray containing 65 GBM specimens with accompanying prognostic information. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that miR-103aLow GBM patients had significantly poorer overall survival than miR-103aHigh GBM patients, suggesting that miR-103a has prognostic value in GBM patients (Figure 5D). Moreover, strong inverse relationships between the expression of miR-103a and that of p65, YY1, XRCC3, and FGF2 were revealed (Figure 5E). Finally, a dataset from The Cancer Genome Atlas showed that p65, YY1, XRCC3, and FGF2 were specifically upregulated in GBM patients who received radiotherapy (Figure 5F). These data were consistent with our in vitro and in vivo findings showing that the p65–YY1–miR-103a–XRCC3–FGF2 axis plays crucial roles in GBM radioresistance and recurrence.

Fig. 5.

The NF-κB–YY1–miR-103a axis is clinically associated with recurrence, worse prognosis, and radioresistance in GBM. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of p65, YY1, FGF2, and XRCC3 and in situ hybridization of miR-103a in primary and recurrent GBM tissues. Scale bars: 250 mm. (B) Immunohistochemical scores of p65, YY1, miR-103a, FGF2, and XRCC3 were compared between primary GBM (n = 38) and recurrent GBM (n = 35). (C) Histograms showing the correlations of high or low miR-103a, p65, YY1, XRCC3, and FGF2 expression levels with primary and recurrent GBM. (D) Kaplan–Meier analysis of patients represented in a GBM tissue microarray. (E) Pearson correlation analysis among p65, miR-103a, YY1, FGF2, and XRCC3 expression in 73 human GBM specimens. (F) GBM patients in the TCGA database were divided into 2 groups: with and without radiotherapy.

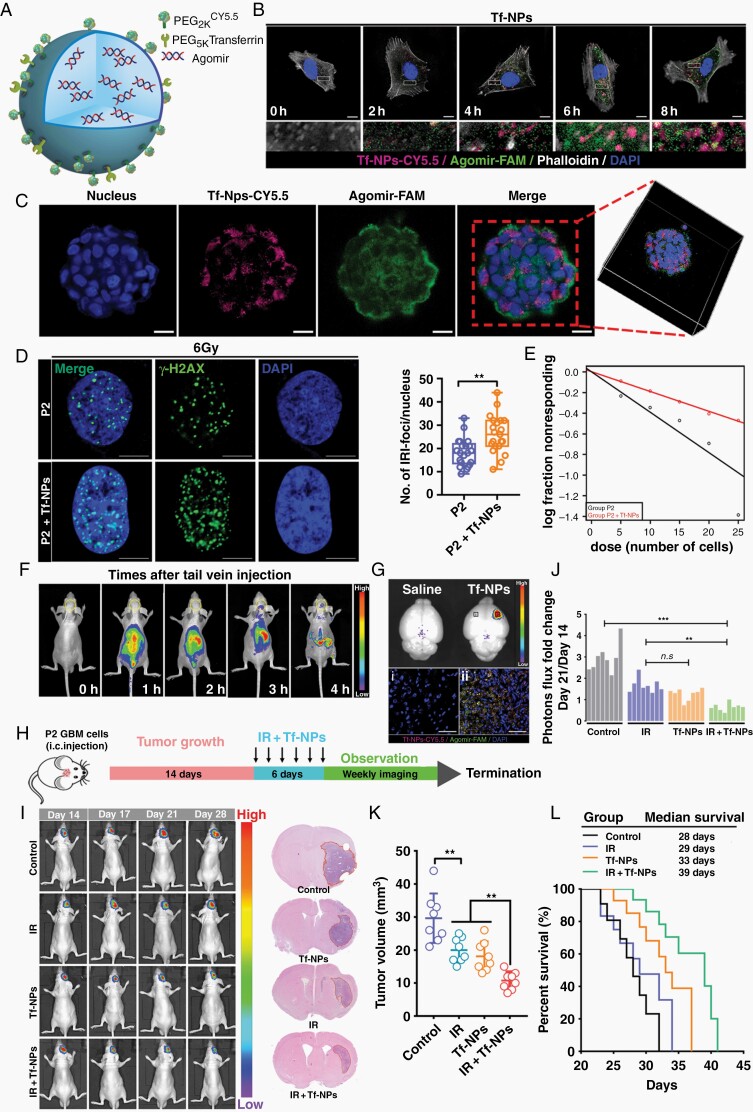

RTP-Targeting Nanoparticles Reverse Refractory GBM and Improve Radiosensitivity

Effective treatment of GBM is limited by the blood–brain barrier (BBB). To address this challenge, nanoparticles have recently been employed to enhance the delivery of drugs across the BBB. The most promising and representative approach is to target endogenous receptor-mediated transport systems.22 Our previous RNA-seq data showed that transferrin receptor (TfR) expression was noticeably elevated in P2 cells (data not shown). Additionally, we found that TfR was rarely expressed in normal human astrocytes (NHAs) but that TfR expression was significantly increased in RTP cells and patients with recurrent GBM compared with the corresponding controls (Supplementary Figure 7A–C). Based on these data, we prepared nanoparticles functionalized with Tf on the surface, designated Tf-NPs, for miR-103a delivery (Figure 6A). Tf-NPs were labeled with Cy5.5, a semiquantitative fluorescent tracer, to assess and trace the biodistribution of Tf-NPs transported across the intact BBB. Transmission electron microscopy imaging revealed that Tf-NPs formed spherical particles and were well dispersed with no aggregation (Supplementary Figure 7D). The maximum absorbance peak of Tf-NPs occurred at 680 nm, confirming that Cy5.5 was successfully coupled with Tf-NPs (Supplementary Figure 7E). Dynamic laser scattering analysis showed that the size of Tf-NPs was 96 ± 29.65 nm and that they had a negative surface charge (−19.1 ± 5.15 mV) (Supplementary Figure 7F–H). Cells incubated with Tf-NPs showed an increased intracellular Cy5.5 signal, which partially colocalized with agomir-FAM in the cytoplasm over time (Figure 6B and Supplementary Figure 7I). As shown in Figure 6C, three-dimensional (3D) laser confocal microscopy showed that Tf-NPs effectively entered spheroids and were widely distributed in the interior regions of the spheroids.

Fig. 6.

RTP-targeting Tf-modified nanoparticles reverse refractory GBM and improve radiosensitivity. (A) Schematic of a PEGylated agomir-loaded nanoparticles that can be functionalized to enhance transport across the BBB and target RTP cells. (B) Immunofluorescence staining demonstrating the time-dependent intracellular uptake of Tf-NPs in P2 cells. Scale bar: 10 μm. (C) Tf-NPs entering a GSC spheroid were monitored by 3D confocal laser microscopy Scale bar: 20 μm. (D) P2 cells were treated with IR in the presence or absence of Tf-NPs, and γ-H2AX foci formation was investigated. Scale bar = 10 μm. (E) In vitro limiting dilution assay. (F and G) In vivo real-time NIR fluorescence imaging of P2 tumor-bearing mice after administration of Tf-NPs for the indicated time periods. (H) Schematic diagram showing the experimental time course and details of the Tf-NP and IR treatment courses. (I) In vivo bioluminescence images of P2 tumor cells in orthotopic mice intravenously injected with Tf-NPs. (J) Statistical analysis of orthotopic tumor growth from P2 cells. (K) Quantification of tumor sizes. The data were obtained from H&E-stained brain sections of 8 mice per group. (L) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of mice intracranially injected with P2 cells.

When exposed to 0–10 Gy radiation, P2 cells pretreated with Tf-NPs demonstrated a significantly decreased survival fraction compared to that of control cells (Supplementary Figure 7J). Accordingly, the formation of DNA damage foci was greatly increased, whereas the self-renewal capacity of GSC was strikingly reduced (Figure 6D and E and Supplementary Figure 7K and L). To determine the Tf-NP delivery efficiency in the orthotopic xenograft model, real-time near-infrared fluorescence imaging showed that the fluorescence signal in Tf-NPs-treated P2 tumor-bearing mice accumulated quickly in the area of the brain at 3 h post-injection and persisted thereafter (Figure 6F). We used a dual universal point excitation light source to locally stimulate the heads of the mice, and quantitative analysis showed that the intensity in the Tf-NP group was higher than that in the control group (Supplementary Figure 8A). Intriguingly, accumulated Tf-NPs were not distributed evenly throughout the brain; instead, they were localized specifically within P2 tumors (Figure 6G). The liver is the main organ for Tf-NP metabolism and, like the brain, exhibited strong Tf-NP accumulation (Supplementary Figure 8B and C). The critical biomarkers of liver and renal damage were not significantly different among the groups (Supplementary Figure 8D and E).

Next, we evaluated the in vivo therapeutic efficacy of Tf-NPs. Tumors were allowed to grow for 14 days, and treatment with saline, IR, Tf-NPs, or IR + Tf-NPs was then administered for 6 days (Figure 6H). The fold change in photon flux showed that combination treatment with IR and Tf-NPs resulted in significantly enhanced inhibition of tumor growth (Figure 6I and J). Histologic evaluation of whole-brain sections confirmed that the tumor volumes actually reflected the differences in the bioluminescence signals (Figure 6K). As expected, overall survival analysis of the treated cohorts showed that the mice treated with Tf-NPs + IR had a significantly increased life expectancy compared with that of untreated mice or mice treated with either Tf-NPs or IR alone (Figure 6L).

Discussion

The universal recurrence of GBM after transient complete radiological remission suggests that even when very few radioresistant cells remain, to the point of being undetectable by conventional imaging, they can regenerate the original tumor, thereby leading to inevitable recurrence.23 Cells that escape the stress induced by radiotherapy, in particular, represent a phenotypically robust subpopulation that can be targeted. The responsible cell subpopulation(s), along with the underlying genetic and molecular mechanisms, are still poorly understood.

One explanation for the discrepancy between the preclinical and clinical data is the widespread use of animal models that fail to reproduce the in vivo conditions.24 Misleading preclinical data have been generated with established cancer cell lines cultured in simplified 2-dimensional in vitro systems, in which cells undergo profound phenotypic changes and exhibit markedly different responses to radiotherapy, leading to wasteful and ineffective trials.25 Here, we present a novel preclinical PDX model ideally suited for radiobiological studies and the adaptation of patient-specific regimens in the era of precision medicine. Pioneering work has associated the radioresistance of GBM and other tumors with the cancer stem cell phenotype, particularly the intrinsic ability to efficiently activate the DDR.26 Our RNA-seq analysis showed that DDR activation and GSC maintenance were important for the radioresistant characteristics of RTP cells. Moreover, mice inoculated with RTP cells showed further enhancement of tumor growth kinetics and radioresistance. These results indicated the expansion of RTP cells, likely benefitting from a selective advantage under radiation pressure and possibly mediating the well-known radioresistance of tumors.

We showed evidence that these cell state transitions are driven by changes in the constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling. Recent studies, including ours, have clarified that NF-κB is activated in tumors after IR treatment.27 NF-κB subunit p65 activated the transcription factor YY1, which led to enhanced expression of YY1 in RTP cells. The expression of YY1 was negatively correlated with the prognosis of both recurrent and primary glioma cases; this finding suggested that YY1 could regulate the advanced malignancy of RTP cells and might also involve in positive regulation of the biology/malignancy of primary glioma cases. In the present study, we also established miR-103a as a key regulator of GBM radioresistance, acting downstream of NF-κB–YY1 signaling. The importance of miR-103a in mediating GBM radioresistance and recurrence was supported by multiple lines of evidence. Unsurprisingly, analysis of clinical samples indicated that low miR-103a expression was associated with therapeutic resistance and a poor prognosis in GBM patients. Our results provide important insights into the mechanisms by which RTP cells survive radical radiotherapy.

There is a need for the development and translation of new GBM treatment strategies designed to target the subpopulation of RTP cells that drives tumor propagation, radioresistance, and recurrence following radiotherapy. However, the development of therapies targeting TFs, such as NF-κB, is notoriously challenging.28 Indeed, to date, no NF-κB-targeted cancer therapeutics have been developed. In addition, although NF-κB is potentially a promising candidate in RTP cells, we should consider that excessive and prolonged NF-κB inhibition is possibly detrimental because of its suppressive effect on innate immunity. Several groups have proposed using miRNA overexpression systems as an anticancer therapeutic strategy, and this approach has led to promising outcomes in vivo. For instance, a miR-16-based microRNA mimic has been studied in a clinical trial of patients with recurrent malignant pleural mesothelioma or non-small-cell lung cancer (NCT02369198).29 In addition, an anti-miR-155 agent is currently in a clinical trial (NCT03713320) for the treatment of patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.30 Thus, therapeutic delivery of miR-103a could provide clinical benefits in GBM. However, the delivery of miRNAs, particularly to central nervous system tumors, remains challenging. Nanoparticles, ranging from 50 to 300 nm in diameter, have been used successfully to deliver genes and drugs. Due to their nanoscale properties, nanoparticles do not undergo renal clearance and thus exhibit prolonged systemic circulation.31 In our study, Tf was conjugated to NPs to improve BBB permeability and tumor targeting. TfR expression was shown to be significantly higher in patients with recurrent GBM who eventually died than in GBM patients without recurrence. Therefore, TfR is an attractive target for delivering therapeutics to treat recurrent or radioresistant GBM. Subsequently, we demonstrated that Tf-NPs were transported across the intact BBB via TfR; after crossing the BBB, PEGylated Tf-NPs specifically recognized TfR-positive GBM tumors and distinguished the tumor cells from normal brain cells. In addition, Tf-NPs exhibited excellent biosafety in vivo. Multiple reasons may explain this lack of toxicity. First, Tf-NPs specifically recognized GBM tumor cells. Thus, Tf-NP accumulation in the tumor area was greater than that in healthy brain tissues. Second, TfR-mediated transcytosis was bidirectional. In healthy brain tissues, penetrating Tf-NPs accumulated near blood vessels. Since Tf-NPs did not accumulate in normal brain cells, some might have returned to the blood circulation. This possibility also indicates the need for careful screening of surface receptor protein levels in GBM patients at the time of biopsy or surgical resection to develop a personalized approach to ligand-targeted nanotherapy. Importantly, we evaluated the ameliorative effect of Tf-NPs on radioresistance in orthotopic P2 tumor-bearing mice. This nanoplatform could be used as an effective delivery system with a high potential for incorporation in the development of miRNA-based therapeutics for GBM.

In conclusion, in this study, a highly efficient and realistic radioresistant PDX model ideally suited radiotherapy studies and the development of novel treatment approaches was developed. We used the model to determine that the RTP subset pool constitutes a reservoir from which radioresistant tumors may develop and is crucial for GBM recurrence. Mechanistically, we defined a regulatory axis centered on miR-103a that plays an important role in oncogenic NF-κB-driven radioresistance in GBM. We also highlighted the possibility of using nanocarriers to treat patients with radioresistant GBM. Our findings not only provide a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying radioresistance in GBM but also identify a molecular target for therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jintao Gu, State Key Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Biotechnology Center, School of Pharmacy, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Nan Mu, Department of Physiology and Pathophysiology, School of Basic Medicine, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Bo Jia, Department of Neurosurgery, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Qingdong Guo, Department of Neurosurgery, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Luxiang Pan, State Key Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Biotechnology Center, School of Pharmacy, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Maorong Zhu, State Key Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Biotechnology Center, School of Pharmacy, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Wangqian Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Biotechnology Center, School of Pharmacy, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Kuo Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Biotechnology Center, School of Pharmacy, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Weina Li, State Key Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Biotechnology Center, School of Pharmacy, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Meng Li, State Key Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Biotechnology Center, School of Pharmacy, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Lichun Wei, Department of Radiotherapy, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Xiaochang Xue, College of Life Sciences, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China.

Yingqi Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Biotechnology Center, School of Pharmacy, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Wei Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Biotechnology Center, School of Pharmacy, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81872049, 81803053, 82003220, and 81373201).

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Authorship statement. Conception and design: J.G. and W.Z. Collection and assembly of data: J.G. and N.M. Data analysis and interpretation: B.J. and J.G. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Accountable for all aspects of the study: All authors.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Nagaraja S, Vitanza NA, Woo PJ, et al. Transcriptional dependencies in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(5):635–652 e636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tirosh I, Suvà ML. Tackling the many facets of glioblastoma heterogeneity. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26(3):303–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sulman EP, Ismaila N, Armstrong TS, et al. Radiation therapy for glioblastoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement of the American Society for Radiation Oncology Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(3):361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Echizenya S, Ishii Y, Kitazawa S, et al. Discovery of a new pyrimidine synthesis inhibitor eradicating glioblastoma-initiating cells. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(2):229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schaue D, McBride WH. Opportunities and challenges of radiotherapy for treating cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(9):527–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shimura T, Noma N, Oikawa T, et al. Activation of the AKT/cyclin D1/Cdk4 survival signaling pathway in radioresistant cancer stem cells. Oncogenesis. 2012;1:e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang J, Cheng P, Pavlyukov MS, et al. Targeting NEK2 attenuates glioblastoma growth and radioresistance by destabilizing histone methyltransferase EZH2. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(8):3075–3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8. Ahmed SU, Carruthers R, Gilmour L, Yildirim S, Watts C, Chalmers AJ. Selective inhibition of parallel DNA damage response pathways optimizes radiosensitization of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75(20):4416–4428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bolli E, D’Huyvetter M, Murgaski A, et al. Stromal-targeting radioimmunotherapy mitigates the progression of therapy-resistant tumors. J Control Release. 2019;314:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bian L, Meng Y, Zhang M, Li D. MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex alterations and DNA damage response: implications for cancer treatment. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gil del Alcazar CR, Hardebeck MC, Mukherjee B, et al. Inhibition of DNA double-strand break repair by the dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 as a strategy for radiosensitization of glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(5):1235–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pilié PG, Tang C, Mills GB, Yap TA. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(2):81–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bodo S, Campagne C, Thin TH, et al. Single-dose radiotherapy disables tumor cell homologous recombination via ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(2):786–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karakashev S, Fukumoto T, Zhao B, et al. EZH2 inhibition sensitizes CARM1-high, homologous recombination proficient ovarian cancers to PARP inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(2):157–167 e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. López GY, Van Ziffle J, Onodera C, et al. The genetic landscape of gliomas arising after therapeutic radiation. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137(1):139–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silva MF, Khokhar AR, Qureshi MZ, Farooqi AA. Ionizing radiations induce apoptosis in TRAIL resistant cancer cells: in vivo and in vitro analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(5):1905–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pavlyukov MS, Yu H, Bastola S, et al. Apoptotic cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote malignancy of glioblastoma via intercellular transfer of splicing factors. Cancer Cell. 2018;34(1):119–135.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu Z, Mesci P, Bernatchez JA, et al. Zika virus targets glioblastoma stem cells through a SOX2-integrin alphavbeta5 axis. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26(2):187–204 e110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. She Y, Han Y, Zhou G, Jia F, Yang T, Shen Z. hsa_circ_0062389 promotes the progression of non-small cell lung cancer by sponging miR-103a-3p to mediate CCNE1 expression. Cancer Genet. 2020;241:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jimenez-Pascual A, Mitchell K, Siebzehnrubl FA, Lathia JD. FGF2: a novel druggable target for glioblastoma? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2020;24(4):311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jimenez-Pascual A, Hale JS, Kordowski A, et al. ADAMDEC1 maintains a growth factor signaling loop in cancer stem cells. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(11):1574–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lajoie JM, Shusta EV. Targeting receptor-mediated transport for delivery of biologics across the blood–brain barrier. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:613–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu J, Sun T, Wang H, et al. MiR-215 is induced post-transcriptionally via HIF-Drosha complex and mediates glioma-initiating cell adaptation to hypoxia by targeting KDM1B. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(1):49–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gomez-Roman N, Stevenson K, Gilmour L, Hamilton G, Chalmers AJ. A novel 3D human glioblastoma cell culture system for modeling drug and radiation responses. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(2):229–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gupta T, Kannan S, Ghosh-Laskar S, Agarwal JP. Systematic review and meta-analyses of intensity-modulated radiation therapy versus conventional two-dimensional and/or or three-dimensional radiotherapy in curative-intent management of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Narayan RS, Gasol A, Slangen PLG, et al. Identification of MEK162 as a radiosensitizer for the treatment of glioblastoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17(2):347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim SH, Ezhilarasan R, Phillips E, et al. Serine/threonine kinase MLK4 determines mesenchymal identity in glioma stem cells in an NF-κB-dependent manner. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(2):201–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perkins ND. The diverse and complex roles of NF-κB subunits in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(2):121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Zandwijk N, Pavlakis N, Kao SC, et al. Safety and activity of microRNA-loaded minicells in patients with recurrent malignant pleural mesothelioma: a first-in-man, phase 1, open-label, dose-escalation study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(10):1386–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valipour A, Jager M, Wu P, et al. Interventions for mycosis fungoides. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7:CD008946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu M, Zheng J. Clearance pathways and tumor targeting of imaging nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2015;9(7):6655–6674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.