Abstract

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has revolutionized HIV prevention, but PrEP does not protect against other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Rates of STIs are rising worldwide, with notably high incidences among PrEP-using men who have sex with men in high-income countries; in low-income and middle-income countries, data are sparse, but results from a limited number of studies among African women initiating and taking PrEP have shown high STI prevalence and incidence. Efforts aimed at markedly reducing HIV in populations worldwide include a major focus on increasing PrEP use, along with improving HIV testing and treatment in order to eliminate HIV transmission. Together, these efforts could augment continued expansion of the global STI epidemic, but they could alternatively create opportunity to improve STI control, including the development of comprehensive sexual health programmes and research to develop new STI prevention strategies. The introduction of PrEP globally has been characterized by challenges and many successes, and its role as part of a range of robust strategies to reduce HIV infections is clear. Looking ahead, understanding rising rates of curable STIs and their relationship to HIV prevention and considering the future directions for synergies in PrEP and STI prevention will be integral to improving sexual health.

Introduction

The use of combination emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF) as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) was approved for adults by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2012 and extended to include adolescents (greater than 35kg) in 2018.1,2 Recommendations for PrEP for all those at risk for HIV were released by CDC in 2014,3 the World Health Organization in 2015,4 and the US Preventive Services Task Force (Grade A recommendation) in 2019;5 countries worldwide have followed the USA with regulatory approval.6,7 PrEP has quickly become a cornerstone of global initiatives to end the HIV pandemic. In October 2019, a second PrEP medication – daily FTC/TAF (tenofovir alafenamide, an alternative tenofovir prodrug that has improved bioavailability and enables a much lower dose) – received approval for use in Canada, Australia, United States, and Taiwan by men who have sex with men (MSM) and other individuals whose HIV risk is not through receptive vaginal sex, based on noninferiority data (IRR of 0.47 (95% CI 0.19-1.15)) in one clinical trial.8-10

PrEP prevents sexual acquisition of HIV;11-13 however, PrEP does not protect against curable sexually transmitted infections (STIs). STI rates are growing around the world, with rapid increases in syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia among MSM with multiple sexual partners in high-income countries and an increase in combined bacterial STI incidence (41–72%) has been observed among MSM in Canada and Australia in correlation with initiation of PrEP.14,15 Data from low-income and middle-income countries are sparse, but suggest high rates of curable STIs, with new Chlamydia trachomatis cases occurring at a rate of more than 20 per 100 person-years among women using PrEP services; in such settings, STI-associated morbidity is commonly high, particularly for women.16-18

The global rise in availability of PrEP and STI prevalence rates occurring together present potential synergies for comprehensive preventive sexual health. The need for access to PrEP and STI control have both gained attention in the scientific and popular press, signaling urgency.19,20

In this Review we address the successes and challenges of PrEP to date, its place as part of robust strategies to reduce HIV infections, rising rates of curable STIs and their relationship with HIV prevention, and future directions for synergies in PrEP and STI prevention.

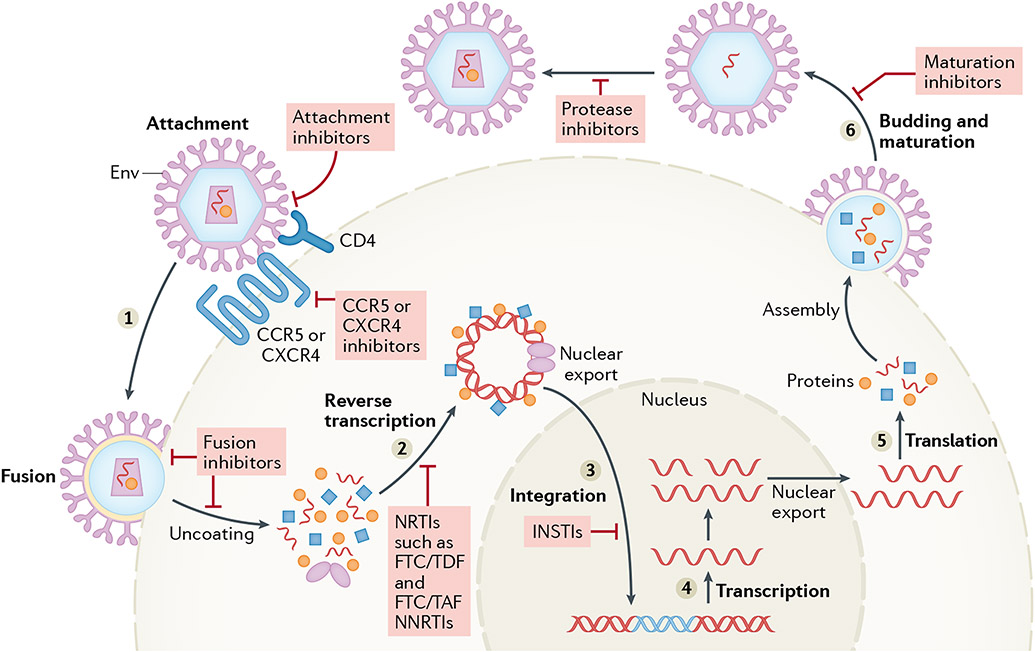

How PrEP works

Use of a combination of antiretroviral agents (e.g., nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors) to inhibit key enzymes needed for viral replication has been the mainstay of treatment of people living with HIV for nearly three decades.21 For those who do not have HIV, PrEP uses one or more antiretroviral agents, often similar or identical to those used in HIV treatment,22 and their use as prophylaxis acts so that an HIV exposure does not result in an infection if drug levels are at a therapeutic level at the time of exposure. In essence, by having the antiretroviral agent in the bloodstream or in relevant tissues (such as vaginal tissue, anal tissue and lymph nodes), the virus will be rendered unable to replicate and infection aborted (Figure 1). Notably, although combination antiretroviral therapy (usually with three active agents) is essential for HIV treatment, HIV prevention seems to be successful with only two or even one antiretroviral medication,23 reducing cost and potential adverse effects. Oral tablets (containing FTC/TDF or FTC/TAF) are currently the only PrEP agents with regulatory approval,24 but multiple other strategies for PrEP delivery, including vaginal rings, injections, and implants are under development to better address individual needs and preferences; all PrEP strategies depend on correct use at the time of exposure and many are aiming for consistency of adherence over longer periods of time (weeks or months) to improve the likelihood of use.

Figure 1. HIV infection and PrEP mechanism of action.

a. After an unprotected exposure, HIV integrates into CD4 cells, replicates, and infects other CD4 cells. b. A single pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) tablet, taken daily, stops HIV from replicating and, therefore, prevents acquisition of HIV in the event of an exposure. Current emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF) and FTC/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) PrEP treatments work against reverse transcriptase enzymes but other, future PrEP agents could have antiretroviral activity against other HIV components.

PrEP efficacy and safety for HIV prevention

Data supporting the approval of FTC/TDF as safe and effective PrEP for HIV prevention was derived from gold-standard, large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. The two trials that form the registrational foundation for FTC/TDF PrEP were the iPrEx trial25, conducted among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women, in which a 44% reduction in HIV incidence (95% CI 15-63; p=0.005) was reported,25 and the Partners PrEP Study13, conducted among heterosexual serodiscordant couples, in which the results showed a 75% reduction in HIV incidence (95% CI 55-87; p<0.001).13 In both trials, testing of blood samples after trial completion found that some participants were not adherent to the study medication.26,27 For those who were adherent to PrEP, HIV protection is estimated to exceed 95% and few cases of breakthrough infections have been documented worldwide, essentially all seeming to be caused by a HIV virus that was resistant to FTC/TDF in the source partner before transmission.28,29

PrEP was first tested in Cameroon, Ghana, and Nigeria in 200430 followed by a phase III trial in 2007 in Peru and Ecuador25 and approved for daily use of FTC/TDF (200mg/300mg).13,31 For daily FTC/TDF use, the WHO implementation tool recommends starting tablets 7 days before sexual exposure to HIV.32 Limited guidance exists on discontinuation of daily PrEP, ranging from maintained daily dosing for 72 hours to 28 days after last sexual exposure.33,34 High HIV protection from non-daily use averaging four doses per week is consistent with data from studies including MSM prescribed daily FTC/TDF that showed extremely effective HIV protection, with a 96% reduction in incidence — providing additional evidence that PrEP can be effective in men without daily dosing.31 Evidence has been provided for alternatives to daily FTC/TDF in studies limited to MSM and others whose principal risk exposure for HIV is receptive anal sex. A 1:1 randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 400 HIV-negative cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men in France demonstrated that dosing FTC/TDF in an on-demand strategy (double dose within 2 to 24 hours before sexual exposure to HIV followed by a single dose 24 hours and 48 hours after the initial double dose, also referred to as event-driven dosing or the 2-1-1 schedule), provides high HIV protection, seemingly comparable to daily FTC/TDF with a 97% (95% CI 81-100) reduction in incidence.35,36 Subsequently, the rapid approval of daily FTC/TAF for use by MSM by the FDA in 2019 was based on strong efficacy evidence for use of TAF in exchange for TDF in HIV treatment regimens in conjunction with robust data on FTC/TDF as PrEP; however, nuanced data on non-daily dosing or efficacy with vaginal receptive intercourse are not yet available.37,38

Because of a paucity of data outside of PrEP use among MSM and transgender women, only daily FTC/TDF, not 2-1-1 dosing or FTC/TAF, is currently recommended for cisgender women and transgender men who have receptive vaginal sex.39 Imperfect adherence to daily PrEP has been associated with low drug levels in vaginal mucosa suggesting that daily PrEP dosing might be important for prevention of HIV in those exposed vaginally.40,41 Importantly, among women who take FTC/TDF PrEP daily, HIV protection is equivalent to that observed in men.26 In many people taking PrEP, use is for a period, with discontinuation and often resumption, often coordinated with changes in sexual behaviour, new partners, or other factors, somewhat analogous to how contraceptives are generally used.42

PrEP is well-tolerated with no major safety concerns.2,43 The most common adverse effect of PrEP in clinical trials was nausea,31 which generally dissipated within the first month. No adverse interactions with contraceptives or fertility (in both women and men) were demonstrated with PrEP use, and USA and WHO guidance recommend PrEP use in women who are pregnant or lactating.4,44,45 Among those living with HIV, long-term use of FTC/TDF for HIV treatment is also very safe, emphasizing that long-term use of PrEP should similarly be safe.46 People living with HIV receiving FTC/TDF treatment demonstrated increased risk of osteopenia and low rates of proximal renal tubulopathy, to some degree probably a synergistic effect between the medication and chronic HIV infection itself.47,48 However, among HIV-negative people receiving PrEP, safety trials did not show an increase in fractures or renal injuries with FTC/TDF use in the first year of use.48-50 Blood biomarkers for FTC/TAF suggest this therapeutic might have even better renal and bone safety than FTC/TDF, and FTC/TAF can be used as PrEP in those with some renal compromise (estimated creatinine clearance ≥30 ml/min) unlike FTC/TDF which is not recommended for use in those with renal compromise (estimated creatinine clearance <60 ml/min).24

PrEP scale-up and effect

The number of people who use PrEP is estimated to be773,000 worldwide, a substantial number but many fewer than the 1.7 million who acquire HIV each year and the many more who are at risk.51 More than half of the worldwide PrEP prescriptions in July 2019 were in four high-income countries: the USA, Australia, France, and England. By October 2020, the USA (200,000) was joined by several low-income and middle-income countries that rapidly scaled up PrEP, including South Africa (88,000), Kenya (72,000), Uganda (47,000), and Zambia (46,000) to make up more than half of PrEP prescriptions.51 In settings with high PrEP roll-out, such as large urban centres with large populations of MSM (for example, San Francisco), new HIV infections have fallen substantially among white men in the past 5 years.52 In Sydney, an intentional PrEP access campaign decreased new HIV diagnoses by 50% over 24 months.53

The USA has the highest number of PrEP prescriptions, but major gaps in PrEP uptake and access persist — only an estimated 35% of those who are at risk of HIV acquisition are being prescribed PrEP, with considerably reduced coverage among racial and gender minorities.54-57 Across the USA, 68.7% of PrEP users are white compared with 11.2% who identified as Black.58 Importantly, despite this reduced uptake,56,59 epidemiological predictions indicate a much increased risk of HIV acquisition for minority populations, with a 1 in 2 lifetime risk among Black MSM and 1 in 5 among Latino-identifying MSM, compared with1 in 11 lifetime risk among white MSM.60 Disparities in HIV incidence and PrEP uptake by race in the USA are not associated with risk behaviour but are associated with sexual networks, geographic distribution of PrEP prescribers, and health insurance access.61 In the USA, 19% of new HIV infections in 2016 were among cisgender women, but only 7% of PrEP use is among cisgender women.62,63 In low-income and middle-income countries, incidence rates of HIV infection in adolescent girls are more than three times that of their male peers,64 but PrEP access for adolescent girls remains low, in large part owing to limited programmatic roll-out (despite generic drug pricing that results in a year of PrEP medication costing ~$70).65 Many countries in which HIV is endemic have identified all adolescent girls and young women aged 15 to 24 years as a key population for PrEP use along with MSM and commercial sex workers; however, this population is much larger than the population currently accessing PrEP.63,66-69 The WHO sustainable development goals regarding quality health services (3.8), ensuring access to sexual and reproductive healthcare (3.7), are linked with goals needed to improve PrEP service delivery and integrating STI and reproductive care into comprehensive health care. Improving access and use can be achieved through universal health coverage and a variety of financial and psychosocial support programmes that are tailored to meet the needs of individuals and their communities. To truly improve the health and safety for these communities, large systemic changes will be required to address root causes for these disparities, including addressing structural racism, transphobia, and homophobia within health care.

Psychosocial factors threaten the adherence to medications of many patients, especially in the absence of adherence counselling and support programmes.70 Barriers to adherence, while common, are driven by many different factors such as challenges with daily medication in absence of daily routine, self-perceived risk, belief in efficacy, stigma, and costs associated with refills.71 Adherence counselling can be supplemented with a variety of care plans as clinically indicated, such as sexual and reproductive care, mental health counselling, housing access assistance, substance abuse treatment, and gender-affirming care.

A new era for HIV

Innovations in HIV prevention and care in the past decade — including but not limited to PrEP — have ushered in a bold new era of how society and individuals think about HIV. First and foremost among these innovations has been the concept of HIV treatment as prevention. Effective HIV treatment suppresses viral levels to undetectable and results in normal lifespans for those living with HIV, often only requiring a single, combination antiretroviral pill taken once a day.72,73 People living with HIV who have undetectable viral loads have zero risk of sexually transmitting HIV, a concept commonly referred to as undetectable=untransmittable (U=U).74,75 U=U messaging on eliminating transmission while on treatment has been an important anti-stigma tool to ease shame and guilt surrounding sexual activity among people living with HIV, which might contribute to high rates of condomless sex and STIs.76 These important developments in HIV care and prevention coinciding with a new generation of sexually active individuals changes perceptions of HIV risk at a population level and reduce risk in sexual networks where care and prevention are accessible and utilized.77-79 At an individual and population level, treatment as prevention can be an important tool for preventing HIV in settings in which people at risk of HIV acquisition have access to health care and timely HIV testing.80 At the population level, PrEP and treatment as prevention are complementary, even synergistic, for reducing HIV and HIV stigma. Decreased fear of HIV is informed by knowledge of PrEP efficacy and the decreased risk of transmission from those living with HIV who are adherent to antiretroviral therapy.79,81

Communities with high use of treatment and PrEP have been transformed by marked population-level decreases in HIV incidence rates.53,82,83 The psychosocial influence of PrEP, an effective HIV prevention tool that does not require partner participation, has not fully been described; qualitative research among MSM in the USA report important effects of PrEP on increased empowerment, decreased fear during sex, and increased sexual pleasure.84,85 Prospective studies involving MSM using PrEP in Australia, Netherlands, and the USA revealed an increase in reported condomless anal sex, although as many studies have shown that starting PrEP does not result in reductions in condom use (more accurately, PrEP initiators were generally not using condoms consistently before PrEP).78,86-88 Changes in rates of condom use have not been reported among cisgender women taking PrEP,89 similar to findings of prior research on use of hormonal contraceptives and emergency contraceptives, which did not change rates of condomless sex.89,90 Importantly, PrEP and ART essentially eliminate HIV acquisition risk, including in the absence of condoms, which has led to calls that their widespread implementation have the potential to end the transmission of HIV.91,92

Rise of STIs in the era of PrEP

Concurrent with the expansion of PrEP use, as well as a new era of HIV treatment with decreased fear of HIV acquisition, the rates of STIs have substantially risen. In high-income settings, this rise began over a decade ago (preceding PrEP) but has continued steadily upward.93 In the USA, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis case numbers have grown every year for the last 5 years and data from 2018 indicated an all-time high in case numbers with largest increase in syphilis cases up 13.3% on the previous year.94 Globally, more than 1 million new curable STIs are contracted each day.95 In many settings, high rates of condomless sex in this new era of HIV are common, which is, in part, the reason for STI rises. Of course, a diagnosis of a new STI often foreshadows HIV acquisition and is, therefore, an indication for considering PrEP initiation, and individuals with STI risks might even seek out PrEP as a strategy to reduce their own risk of HIV infection.96,97 Untreated STIs increase the biological risk of HIV acquisition and transmission with each sexual act,46 and in many cases indicate one or more other HIV risk factors, such as condomless sex within a concurrent partnership.98

The relationship between STI risk and HIV risk is further compounded by changes in sexual behaviour. This association is shown in prospectively obtained data from 114 MSM with mean age 34 years in Australia who had increased STI incidence overall (incidence rate ratio 2.77 (1.52, 5.56)), especially anal detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the first 12 months of PrEP use, with 7.2% prevalence at baseline and 37.8 (per 100 person-years) cumulative incidence at months 3–12, (incidence rate ratio 5.26 (1.33, 45.41)).86 Incidence of curable STIs are rising an unprecedented rate among populations with high rates of PrEP uptake, such as MSM in high-income settings, e.g., San Francisco, Seattle, Sydney, Melbourne, where HIV incidence has declined and bacterial STI incidences rate have nearly doubled in the last decade.14,99-103 Even among populations not yet using PrEP at considerable levels, such as young women in sub-Saharan Africa, or young men in the southern USA, curable STI prevalence rates are high, as high as 29% among both African women and American MSM.16,18,65 104 Debate about whether or not the use of PrEP changes sexual risk taking is substantial, largely driven by the high frequency of STI diagnosis, with guidelines calling for an increase from annual screening to biannual or quarterly screening, among PrEP users.3,105,106 Conversely, concern about sexual liberation has been topic of much debate with each sexual health intervention, such as contraception or condom use.107,108 Qualitative reports of reduced fear during intercourse were associated with PrEP use as well as some evidence of increased condomless anal sex suggesting increased sexual liberation.109 Recognizing that PrEP is being used by those with preexisting risk, such as those who have multiple partners of unknown HIV status and low rates of condom use, is important and its protective benefits far outweigh any risk compensation.81,110,111

Regardless of the causal connection between PrEP and rising rates of STIs, the expansion of STIs globally is notable in general and in people who use PrEP in particular. Escalating N. gonorrhoeae cases are especially concerning as multidrug-resistant organisms become more common.112 Chlamydia trachomatis incidence rates in women in PrEP trials in sub-Saharan Africa approached a notable 50%.113 N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are principal aetiologies for severe infections including urethritis, cervicitis, prostatitis, epididymitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and extragenital disease,114,115 making their rise alarming. Syphilis incidence rates have been climbing consistently for the last decade in the USA from 14.6 per 100,000 in 2009 to 39.7 per 100,000 in 2019 with a 11.2% increase from 2018 to 2019.116,117 In 2019, a concerning increase in congenital syphilis was observed in the USA with a total of 1,870 cases, a 279% increase from 2015.116,117 Interestingly, rates of herpes have decreased,118 and some modest evidence shows that FTC/TDF might reduce herpes acquisition through a dual antiviral effect with a subgroup analysis of a placebo controlled PrEP trial reporting a 0.70 Hazard Ratio (95% CI, 0.49 to 0.99; p=0.047) of HSV-2 acquisition with daily PrEP.119 There are several obstacles to controlling the rise of STI incidence rates and access to aetiologic testing prevents the detection of the majority of infections which are asymptomatic.18,120 Rising rates of curable STIs demonstrate the importance of frequent testing for public health control of the STI epidemic, to identify patients who could benefit from PrEP, and to improve care of patients taking PrEP.

Integrating PrEP care with comprehensive care

PrEP prescriptions are becoming increasingly available with PrEP programmes established in 68 countries.63 People who are taking PrEP need HIV testing every 3 months, and many providers and programmes recognize the importance of integrating PrEP care into general care and offering additional services at PrEP follow-up consultations. The monitoring and support recommendations for PrEP prescription are minimal (Table 1), and PrEP prescription is not restricted to HIV care specialists.121 For individuals and populations, the intersection of PrEP and STIs offers new opportunities for improvements in care, screening, treatment, and prevention. Individuals accessing PrEP have the power to control their own risk of HIV acquisition through diligent adherence to PrEP and reliable access to PrEP is an important component of adherence. PrEP prescriber networks imperatively need to be expanded by integrating PrEP care into preexisting healthcare systems, such as primary care, urology, emergency medicine, gynecology, and other settings.122 To maximize the potential of PrEP, decentralized, cost-effective, and comprehensive programmes are needed to close access gaps and support PrEP use.

Table 1.

Recommended monitoring and support for PrEP use.

| Timeline | Laboratory tests | Additional care |

|---|---|---|

| PrEP initiation | ||

| HIV test | Screen for acute HIV | |

| Screen for syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea | Document Hepatitis B vaccine | |

| Serum creatinine | Safer sex counselling and other sexual health services (such as condoms, consideration of other relevant vaccines (for example HPV), and so on) | |

| **Pregnancy test | **Substance abuse care | |

| Follow-up visits (every *3–6 months) | ||

| HIV test | Adherence counselling | |

| Screen for syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea | Adverse effect screening | |

| *Serum creatinine | Repeat safer sex counselling and other sexual health services | |

| **Pregnancy test | **Substance abuse care | |

Guidelines differ by nation

When clinically indicated

With a large unmet need to expand PrEP access, further decentralization of PrEP care outside of clinic appointments could substantially improve access to PrEP. Similar to increasing access to emergency contraceptives, pharmacy-delivered care is an important step in improving access in many parts of the world. Additionally, mail-order PrEP is becoming increasingly popular in high-income countries, e.g., “I Want PrEP Now” in the UK, “PrEP Access Now” in Australia, and “Ready, Set, PrEP” in the U.S.123 Decentralized delivery of PrEP relies on new and evolving technology for patient-directed care, such as HIV self-testing kits,124,125 mail-in self-collected STI screening services,126 and point-of-care STI tests.17,127

Combining PrEP and STI management

The current syndemic of curable STIs and HIV can readily be observed among people prescribed PrEP and getting STIs and people with a new STI diagnosis leading to a new PrEP prescription. The public health crisis of rising STI rates demands new interventions for populations at risk for HIV and STIs.19 The current recommendations for STI control continue to rely on presenting for frequent screening and treatment based on physician-identified risk factors.128 MSM and transgender women having sex with men, who are already taking PrEP, are identified as at increased risk for STI acquisition, and in guidelines in high-resource settings, where aetiologic testing is accessible, screening all potentially exposed sites (urine, pharynx, and anus) every 3 months is recommended.3 Treatment of existing infections can be augmented by secondary prevention through use of expedited partner therapy; that is, the provision of pathogen-specific treatment to the primary partner of the infected patient.129,130 In low-income and middle-income countries where testing is not readily available, guidelines rely on empirical treatment in patients presenting with cervicitis or urethritis, or syndromic management.128 Syndromic management has low sensitivity (27-61%) and moderate specificity (41-99%), missing ~70% of infections that are asymptomatic, and some patients are exposed to unnecessary antibiotics when treating broadly for nonspecific symptoms and potentially contributing to antimicrobial resistance.120,131,132 Despite the frequent testing that is recommended for PrEP users in high-income countries, screening programmes for PrEP users in low-income and middle-income countries have not yet expanded beyond syndromic management owing to resource limitations.32,133 New point-of-care STI testing platforms currently being developed, e.g., binx health,134 have the potential to improve access in low-income and middle-income countries if prices are made affordable through collective price negotiations or bulk.132,135

Frequent testing and treatment of STIs remains the standard for STI control, and the expansion of PrEP services creates an important opportunity for improving STI control. Similarly, a new diagnosis with an STI might be an important cue for detecting an unknown HIV infection or initiation of PrEP given overlapping sexual exposure risk factors.

Future of PrEP care and STI prevention

PrEP modalities, dosing schedules, and prescription sites are growing in number and diversity and will improve the individualization of the approach to HIV prevention. Long-acting, injectable PrEP has been shown to be effective at preventing acquisition of HIV. Two double-blinded randomized trials of cabotegravir injections every 8 weeks compared with oral TDF/FTC reported 66% (HR 0.33, 95% CI 0.18-0.62, MSM and transgender women) and 89% (HR 0.11, 95% CI 0.04-0.32, cisgender women) reductions in incident HIV infections, reflecting high efficacy for the injection with better adherence than for the daily pills.136,137 Ongoing development and roll-out of injectable PrEP along with a dapivirine vaginal ring form of PrEP will provide potential options for select patients who find taking daily pills challenging.138 As alternatives to daily PrEP use become available, an increased number of patients will be able to find a method that works for them. Additionally, the increased availability of PrEP prescriptions outside of specialty clinics could follow a similar model to the variety of birth control options widely accessible beyond family planning clinics.139

Currently, frequent screening for asymptomatic STIs is an important part of STI control but future developments in primary prevention of STIs (such as event-driven doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (dPEP) and vaccinations) could theoretically decrease the need for frequent screening.140,141 A trial in France involving 232 MSM who were taking PrEP found significant reductions in incidence rates of chlamydia (HR 0.30; 95% CI 0.13-0.70; p=0.006) and syphilis (HR 0.27; 0.07-0.98; p=0.047) with use of single-dose dPEP following each day that they had had a condomless sexual exposure.142 Additional trials are ongoing to further investigate the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of dPEP.143,144 An epidemiological review in New Zealand noted a substantial (31%; 95% CI 21-39) decrease in gonorrhea infections among 14730 patients diagnosed with chlamydia and/or gonorrhea infection comparing those who received a full series of conjugate meningococcal vaccine, MeNZB, (n=7429) with those who were unvaccinated (n=6361) creating renewed hope for possible creation of a N. gonorrhoeae vaccine.145 In 2019 a C. trachomatis vaccine entered into a phase III trial, demonstrating that some curable STIs might be vaccine-preventable in the future.146 Vaccines are frequently the most effective means of infection prevention and could easily be incorporated into HIV prevention care.

Conclusions

PrEP is highly effective and is revolutionizing the prevention of HIV. Individuals presenting with an STI diagnosis are at increased risk of acquiring an HIV infection, and STIs are on the rise worldwide. PrEP and STI care go hand-in-hand: PrEP prescriptions should be considered in patients presenting with an STI diagnosis, and patients who are taking PrEP need frequent screening for STIs. PrEP access needs to be expanded to reach the many individuals who would benefit from biomedical HIV prevention. To maximize the potential of PrEP to help achieve the eradication of HIV, PrEP programmes integrated into other health-care services are needed to close access gaps, support PrEP user adherence, and increase STI prevention. The expansion of PrEP prescribers creates a crucial opportunity to improve comprehensive sexual health care and STI control.

Key points.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) prevents sexual acquisition of HIV and is a part of comprehensive, evidence-informed primary and specialty care. Expanding access to and initiation of PrEP is a key part of global efforts to reverse the HIV epidemic.

Sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates are rising worldwide and integration of STI prevention and care with PrEP care is an important opportunity for leveraging resources and synergizing interventions.

Strategies to simplify PrEP care and STI testing and treatment, including self-care approaches, could increase the number of individuals receiving effective HIV and STI prevention.

Research into new STI prevention strategies is still needed.

Acknowledgements:

US National Institutes of Health (grants R01AI145971, P30AI027757, K23MH124466, and T32AI007044).

Footnotes

Competing interests

JS declares no competing interests; JMB has served as an advisor to Gilead Science, Janssen, and Merck.

References

- 1.Blackwell CW Preventing HIV Infection in High-Risk Adolescents Using Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 29, 770–774 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosek SG, et al. An HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Demonstration Project and Safety Study for Young MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 74, 21–29 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2017 Update: a clinical practice guideline. Vol. 2018 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Guideline on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV. (Geneva, 2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Force, U.S.P.S.T., et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 321, 2203–2213 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairns G, McCormack S & Molina JM The European preexposure prophylaxis revolution. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 11, 74–79 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright E, et al. Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: clinical guidelines. Update April 2018. J Virus Erad 4, 143–159 (2018). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sax PE, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide vs. tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in single tablet regimens for initial HIV-1 therapy: a randomized phase 2 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 67, 52–58 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta SK, et al. Renal safety of tenofovir alafenamide vs. tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: a pooled analysis of 26 clinical trials. Aids 33, 1455–1465 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hare CB, et al. The Phase 3 Discover Study: Daily F/TAF or F/TDF for HIV PrEP. in CROI (Seattle, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson PL, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 4, 151ra125 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baeten JM, et al. Single-agent tenofovir versus combination emtricitabine plus tenofovir for pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 acquisition: an update of data from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 14, 1055–1064 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baeten JM, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 367, 399–410 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen VK, et al. Incidence of sexually transmitted infections before and after preexposure prophylaxis for HIV. Aids 32, 523–530 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Traeger MW, et al. Association of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis With Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Individuals at High Risk of HIV Infection. JAMA 321, 1380–1390 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morton J, et al. High prevalence of curable STIs among young women initiating PrEP in Kenya and South Africa. in AIDS 2018: 22nd International AIDS Conference, Vol. Abstract WEPEC224 (Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrett N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Xpert CT/NG and OSOM Trichomonas Rapid assays for point-of-care STI testing among young women in South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 9, e026888 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart J, Bukusi E, Celum C, Delany-Moretlwe S & Baeten JM Sexually transmitted infections among African women: an opportunity for combination sexually transmitted infection/HIV prevention. Aids 34, 651–658 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisinger RW, Erbelding E & Fauci AS Refocusing Research on Sexually Transmitted Infections. J Infect Dis (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stack L Sexually Transmitted Disease Cases Reach a Record High. in The New York Times; (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryom L, et al. 2019 update of the European AIDS Clinical Society Guidelines for treatment of people living with HIV version 10.0. HIV Med 21, 617–624 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Günthard HF, et al. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults: 2016 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA 316, 191–210 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baeten JM, et al. Single-agent tenofovir versus combination emtricitabine plus tenofovir for pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 acquisition: an update of data from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 14, 1055–1064 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.FDA. FDA approves second drug to prevent HIV infection as part of ongoing efforts to end the HIV epidemic. (FDA News Release, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant RM, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 363, 2587–2599 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donnell D, et al. HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 66, 340–348 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haberer JE, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a substudy cohort within a clinical trial of serodiscordant couples in East Africa. PLoS Med 10, e1001511 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colby DJ, et al. Acquisition of Multidrug-Resistant Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Infection in a Patient Taking Preexposure Prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markowitz M, et al. Newly Acquired Infection With Multidrug-Resistant HIV-1 in a Patient Adherent to Preexposure Prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 76, e104–e106 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson L, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for prevention of HIV infection in women: a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Clin Trials 2, e27 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant RM, L.J., Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 363, 2587–2599 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO. WHO Implementation tool for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV infection. Module 1: Clinical., Vol. (WHO/HIV/2017.17) (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seifert SM, et al. Dose response for starting and stopping HIV preexposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 60, 804–810 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saag MS, et al. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults: 2018 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA 320, 379–396 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molina JM, et al. Efficacy, safety, and effect on sexual behaviour of on-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in men who have sex with men: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 4, e402–e410 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molina JM, et al. On-Demand Preexposure Prophylaxis in Men at High Risk for HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med 373, 2237–2246 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeJesus E, et al. Superior Efficacy and Improved Renal and Bone Safety After Switching from a Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate- to a Tenofovir Alafenamide-Based Regimen Through 96 Weeks of Treatment. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 34, 337–342 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daar ES, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to fixed-dose bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide from boosted protease inhibitor-based regimens in virologically suppressed adults with HIV-1: 48 week results of a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV 5, e347–e356 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO. What’s the 2+1+1? Event-driven oral pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV for men who have sex with men: Update to WHO’s recommendation on oral PrEP. in Technical brief 24 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson CG, Cohen MS & Kashuba AD Antiretroviral pharmacology in mucosal tissues. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 63 Suppl 2, S240–247 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karim SS, Kashuba AD, Werner L & Karim QA Drug concentrations after topical and oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis: implications for HIV prevention in women. Lancet 378, 279–281 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pyra M, et al. Patterns of Oral PrEP Adherence and HIV Risk Among Eastern African Women in HIV Serodiscordant Partnerships. AIDS Behav (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mullins TLK & Lehmann CE Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Prevention in Adolescents and Young Adults. Curr Pediatr Rep 6, 114–122 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Were EO, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis does not affect the fertility of HIV-1-uninfected men. Aids 28, 1977–1982 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fonner VA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. Aids 30, 1973–1983 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arribas JR, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, emtricitabine, and efavirenz compared with zidovudine/lamivudine and efavirenz in treatment-naive patients: 144-week analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 47, 74–78 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mugwanya K, et al. Low Risk of Proximal Tubular Dysfunction Associated With Emtricitabine-Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Preexposure Prophylaxis in Men and Women. J Infect Dis 214, 1050–1057 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mulligan K, et al. Effects of Emtricitabine/Tenofovir on Bone Mineral Density in HIV-Negative Persons in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis 61, 572–580 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grohskopf LA, et al. Randomized trial of clinical safety of daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 64, 79–86 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pilkington V, Hill A, Hughes S, Nwokolo N & Pozniak A How safe is TDF/FTC as PrEP? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of adverse events in 13 randomised trials of PrEP. J Virus Erad 4, 215–224 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.AVAC. Global PrEP Use Landscape as of July 2019. in Global Tracker (PrEPWatch, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 52.County, P.H.-S.C. HIV Epidemiology Annual Report: County of Santa Clara, 2018. (2019).

- 53.Grulich AE, et al. Population-level effectiveness of rapid, targeted, high-coverage roll-out of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: the EPIC-NSW prospective cohort study. Lancet HIV 5, e629–e637 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finlayson T, et al. Changes in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Awareness and Use Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - 20 Urban Areas, 2014 and 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68, 597–603 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Calabrese SK, et al. Current US Guidelines for Prescribing HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Disqualify Many Women Who Are at Risk and Motivated to Use PrEP. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 81, 395–405 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siegler AJ, et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol 28, 841–849 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poteat T, et al. A Gap Between Willingness and Uptake: Findings from Mixed Methods Research on HIV Prevention among Black and Latina Transgender Women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N & Hoover KW HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis, by Race and Ethnicity - United States, 2014-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67, 1147–1150 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, Paz-Bailey G & National, H.I.V.B.S.S.G. Willingness to Take, Use of, and Indications for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men-20 US Cities, 2014. Clin Infect Dis 63, 672–677 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J & Hall HI Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 27, 238–243 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sullivan PS, et al. Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA: a prospective observational cohort study. Ann Epidemiol 25, 445–454 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raifman JR, et al. Brief Report: Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Awareness and Use Among Cisgender Women at a Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 80, 36–39 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.AVAC. Country Updates - PrEPWatch. Vol. 2018 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 64.UNAIDS. Trend of New HIV Infections. in AIDSinfo (AIDSinfo, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Celum CL, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women in Africa: from efficacy trials to delivery. J Int AIDS Soc 22 Suppl 4, e25298 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.UNAIDS. THE GAP REPORT. (2015).

- 67.UNAIDS. UNAIDS DATA 2018. (2018).

- 68.Watch, P. PrEP-it Pilot User Guide. Vol. Version 1.0 (2019).

- 69.Vandepitte J, et al. Estimates of the number of female sex workers in different regions of the world. Sex Transm Infect 82 Suppl 3, iii18–25 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Rendina HJ, Surace A & Lelutiu-Weinberger CL From efficacy to effectiveness: facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS 27, 248–254 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hosek SG, et al. Safety and Feasibility of Antiretroviral Preexposure Prophylaxis for Adolescent Men Who Have Sex With Men Aged 15 to 17 Years in the United States. JAMA Pediatr 171, 1063–1071 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kapadia SN, et al. HIV virologic response better with single-tablet once daily regimens compared to multiple-tablet daily regimens. SAGE Open Med 6, 2050312118816919 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hanna DB, et al. Increase in single-tablet regimen use and associated improvements in adherence-related outcomes in HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 65, 587–596 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodger AJ, et al. Sexual Activity Without Condoms and Risk of HIV Transmission in Serodifferent Couples When the HIV-Positive Partner Is Using Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. JAMA 316, 171–181 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rodger AJ, et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet 393, 2428–2438 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Closson EF, et al. Intimacy versus isolation: a qualitative study of sexual practices among sexually active HIV-infected patients in HIV care in Brazil, Thailand, and Zambia. PLoS One 10, e0120957 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Ferguson J & Sharma V Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potential. The Lancet 369, 1220–1231 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoornenborg E, et al. Change in sexual risk behaviour after 6 months of pre-exposure prophylaxis use: results from the Amsterdam pre-exposure prophylaxis demonstration project. Aids 32, 1527–1532 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Newcomb ME, Mongrella MC, Weis B, McMillen SJ & Mustanski B Partner Disclosure of PrEP Use and Undetectable Viral Load on Geosocial Networking Apps: Frequency of Disclosure and Decisions About Condomless Sex. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 71, 200–206 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen MS, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 365, 493–505 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Koester K, et al. Risk, safety and sex among male PrEP users: time for a new understanding. Cult Health Sex 19, 1301–1313 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.CDC. HIV Incidence: Estimated Annual Infections in the U.S., 2010-2016. in CDC Fact Sheet (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brown AE, et al. Fall in new HIV diagnoses among men who have sex with men (MSM) at selected London sexual health clinics since early 2015: testing or treatment or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? Euro Surveill 22(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carlo Hojilla J, et al. Sexual Behavior, Risk Compensation, and HIV Prevention Strategies Among Participants in the San Francisco PrEP Demonstration Project: A Qualitative Analysis of Counseling Notes. AIDS Behav 20, 1461–1469 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Grant RM & Koester KA What people want from sex and preexposure prophylaxis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 11, 3–9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lal L, et al. Medication adherence, condom use and sexually transmitted infections in Australian preexposure prophylaxis users. Aids 31, 1709–1714 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Montano MA, et al. Changes in Sexual Behavior and STI Diagnoses Among MSM Initiating PrEP in a Clinic Setting. AIDS Behav 23, 548–555 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu AY, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection Integrated With Municipal- and Community-Based Sexual Health Services. JAMA Intern Med 176, 75–84 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Heffron R, et al. Objective Measurement of Inaccurate Condom Use Reporting Among Women Using Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate for Contraception. AIDS Behav 21, 2173–2179 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sander PM, Raymond EG & Weaver MA Emergency contraceptive use as a marker of future risky sex, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 201, 146 e141–146 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kasaie P, et al. The Impact of Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: An Individual-Based Model. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 75, 175–183 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eisinger RW & Fauci AS Ending the HIV/AIDS Pandemic(1). Emerg Infect Dis 24, 413–416 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McManus H, et al. STI trends following PrEP uptake in men who have sex with men in a population-based implementation project. JAMA Netw Open (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 94.CDC. New CDC analysis shows steep and sustained increases in STDs in recent years. (CDC Newsroom Releases, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Newman L, et al. Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting. PLoS One 10, e0143304 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Bell TR, Kerani RP & Golden MR HIV Incidence Among Men Who Have Sex With Men After Diagnosis With Sexually Transmitted Infections. Sex Transm Dis 43, 249–254 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tilchin C, et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Diagnosis After a Syphilis, Gonorrhea, or Repeat Diagnosis Among Males Including non-Men Who Have Sex With Men: What Is the Incidence? Sex Transm Dis 46, 271–277 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fleming DT & Wasserheit JN From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect 75, 3–17 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ong JJ, et al. Global Epidemiologic Characteristics of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Individuals Using Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2, e1917134 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ramchandani MS & Golden MR Confronting Rising STIs in the Era of PrEP and Treatment as Prevention. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 16, 244–256 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Comninos NB, et al. Increases in pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae positivity in men who have sex with men, 2011-2015: observational study. Sex Transm Infect 96, 432–435 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Martin-Sanchez M, et al. Trends and differences in sexual practices and sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men only (MSMO) and men who have sex with men and women (MSMW): a repeated cross-sectional study in Melbourne, Australia. BMJ Open 10, e037608 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pagkas-Bather J, Khosropour CM, Golden MR, Thibault C & Dombrowski JC Population-Level Effectiveness of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among MSM and Transgender Persons With Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 87, 769–775 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rolle CP, et al. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis among Black and White men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Int J STD AIDS 28, 849–857 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rojas Castro D, Delabre RM & Molina JM Give PrEP a chance: moving on from the "risk compensation" concept. J Int AIDS Soc 22 Suppl 6, e25351 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wright E, et al. Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: clinical guidelines. Update April 2018. J Virus Erad 4, 143–159 (2018). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Atkins DN & Bradford WD Association between Increased Emergency Contraception Availability and Risky Sexual Practices. Health Serv Res 50, 809–829 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schuster MA, Bell RM, Berry SH & Kanouse DE Impact of a high school condom availability program on sexual attitudes and behaviors. Fam Plann Perspect 30, 67–72, 88 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Traeger MW, et al. Effects of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection on Sexual Risk Behavior in Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 67, 676–686 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Montano MA, et al. Differences in sexually transmitted infection risk comparing preexposure prophylaxis users and propensity score matched historical controls in a clinic setting. Aids 33, 1773–1780 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Holt M, et al. Community-level changes in condom use and uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by gay and bisexual men in Melbourne and Sydney, Australia: results of repeated behavioural surveillance in 2013-17. Lancet HIV 5, e448–e456 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.WHO. Global action plan to control the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. in Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stewart J, Bukusi E, Celum C, Delany-Moretlwe S & Baeten JM Sexually transmitted infections among African women: an underrecognized epidemic and an opportunity for combination STI/HIV prevention. Aids In press.(2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Moore MS, Golden MR, Scholes D & Kerani RP Assessing Trends in Chlamydia Positivity and Gonorrhea Incidence and Their Associations With the Incidence of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Ectopic Pregnancy in Washington State, 1988-2010. Sex Transm Dis 43, 2–8 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Brill JR Diagnosis and treatment of urethritis in men. Am Fam Physician 81, 873–878 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.CDC. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2019. (Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 117.CDC. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2018: Syphilis. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T & McQuillan GM Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2--United States, 1999-2010. J Infect Dis 209, 325–333 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Celum C, et al. Daily oral tenofovir and emtricitabine-tenofovir preexposure prophylaxis reduces herpes simplex virus type 2 acquisition among heterosexual HIV-1-uninfected men and women: a subgroup analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 161, 11–19 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zemouri C, et al. The Performance of the Vaginal Discharge Syndromic Management in Treating Vaginal and Cervical Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 11, e0163365 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stewart J & Stekler JD How to incorporate HIV PrEP into your practice. J Fam Pract 68, 254–261 (2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wood BR, et al. Knowledge, Practices, and Barriers to HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Prescribing Among Washington State Medical Providers. Sex Transm Dis 45, 452–458 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Siegler AJ, et al. Developing and Assessing the Feasibility of a Home-based Preexposure Prophylaxis Monitoring and Support Program. Clin Infect Dis 68, 501–504 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gichangi A, et al. Impact of HIV Self-Test Distribution to Male Partners of ANC Clients: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 79, 467–473 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mulubwa C, et al. Community based distribution of oral HIV self-testing kits in Zambia: a cluster-randomised trial nested in four HPTN 071 (PopART) intervention communities. Lancet HIV 6, e81–e92 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ogale Y, Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, Toskin I & Narasimhan M Self-collection of samples as an additional approach to deliver testing services for sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health 4, e001349 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Widdice LE, et al. Performance of the Atlas Genetics Rapid Test for Chlamydia trachomatis and Women's Attitudes Toward Point-Of-Care Testing. Sex Transm Dis 45, 723–727 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.WHO. GLOBAL HEALTH SECTOR STRATEGY ON SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS 2016-2021 TOWARDS ENDING STIs. WHO Bullitin (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kissinger P, et al. Effectiveness of patient delivered partner medication for preventing recurrent Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Infect 74, 331–333 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Golden MR, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med 352, 676–685 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Otieno FO, et al. Evaluation of syndromic management of sexually transmitted infections within the Kisumu Incidence Cohort Study. Int J STD AIDS 25, 851–859 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Verwijs MC, et al. Targeted point-of-care testing compared with syndromic management of urogenital infections in women (WISH): a cross-sectional screening and diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Infect Dis 19, 658–669 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Guidelines on Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV in Kenya. (2018).

- 134.Van Der Pol B, et al. Evaluation of the Performance of a Point-of-Care Test for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea. JAMA Netw Open 3, e204819 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Juneja S, Gupta A, Moon S & Resch S Projected savings through public health voluntary licences of HIV drugs negotiated by the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP). PLoS One 12, e0177770 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Statement—NIH Study Finds Long-Acting Injectable Drug Prevents HIV Acquisition in Cisgender Women. in Long-Acting Regimen More Effective than Daily Oral Pill Among African Women (NIH, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 137.NIH. NIH study finds long-acting injectable drug prevents HIV acquisition in cisgender women. in Long-acting regimen more effective than daily oral pill among African women. (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 138.WHO. WHO recommends the dapivirine vaginal ring as a new choice for HIV prevention for women at substantial risk of HIV infection. (ed. news, D.) (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sitruk-Ware R, Nath A & Mishell DR Jr. Contraception technology: past, present and future. Contraception 87, 319–330 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Gottlieb SL, et al. Gonococcal vaccines: Public health value and preferred product characteristics; report of a WHO global stakeholder consultation, January 2019. Vaccine 38, 4362–4373 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kenyon C, Van Dijck C & Florence E Facing increased sexually transmitted infection incidence in HIV preexposure prophylaxis cohorts: what are the underlying determinants and what can be done? Curr Opin Infect Dis 33, 51–58 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Molina JM, et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis with doxycycline to prevent sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: an open-label randomised substudy of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Lancet Infect Dis 18, 308–317 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Identifier NCT03980223, Evaluation of Doxycycline Post-exposure Prophylaxis to Reduce Sexually Transmitted Infections in PrEP Users and HIV-infected Men Who Have Sex With Men. in ClinicalTrials.gov (National Library of Medicine (US), Bethesda (MD), 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 144.Doxycycline PEP for Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Kenyan Women Using HIV PrEP. in ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04050540 (ClinicalTrials.gov, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 145.Petousis-Harris H, et al. Effectiveness of a group B outer membrane vesicle meningococcal vaccine against gonorrhoea in New Zealand: a retrospective case-control study. Lancet 390, 1603–1610 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Identifier NCT03926728, Safety and Immunogenicity of a Chlamydia Vaccine CTH522 (CHLM-02). in ClinicalTrials.gov (National Library of Medicine (US), Bethesda (MD), 2019). [Google Scholar]