Abstract

CONTEXT:

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a quite common chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder affecting the oral cavity and skin. The current treatment relies on systemic or topical corticosteroids but is known to cause side effects thereby demanding a search for an alternative.

AIM:

This study aims to assess and to compare the efficacy of topical Coconut (Cocos nucifera) 50% cream and Clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment for the management of OLP.

SETTINGS AND DESIGN:

An institution-based double-blinded randomized control trial.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Sixty clinically diagnosed OLP patients were allotted to two groups (30 in each): Group I (Coconut cream-50%) and Group II (Clobetasol Propionate ointment-0.05%). Patients were examined every 15 days until two months for a change in the lesion size and reduction in the burning sensation. The measurement of lesion size and burning sensation was done using Adobe Photoshop software (version CS3) and Numeric Pain Rating scale (NPS), respectively.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS USED:

The recordings were subjected to the statistical analysis using Wilcoxon matched-pairs and Mann–Whitney U tests for intra-group and inter-group comparisons, respectively.

RESULTS:

There was an 85% regression in the size of the lesion in Group I whereas Group II had it to be 95%, and a 100% reduction in the NPS score in Group I whereas Group II had it to be 95%.

CONCLUSION:

The Coconut cream showed a significant decrease in the size of the lesion and the burning sensation with no side effects neither any signs of toxicity reported during the treatment or follow-up, thereby proving to be a safe and promising medication for OLP.

Keywords: Burning sensation, clobetasol propionate, coconut cream, oral lesion, oral lichen planus

Introduction

Lichen planus is a quite common chronic inflammatory potentially malignant disorder that occurs involving the skin and oral mucous membrane with a prevalence of 1%–2%.[1] It usually occurs in the age group of 30–60 years and there is a high prevalence among the females.[2] Several factors have been predisposed to this condition but the exact etiology is unknown. However, evidence suggests that it is an autoimmune disorder in which the auto-cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes induce apoptosis causing damage to the basal layer of oral epithelium.[2,3]

At the first place, the disease mechanism includes the keratinocyte antigen expression or antigen unmasking that may be a heat shock protein or a self-peptide.[4] Ensuing this, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells migrate toward basal keratinocytes into the epithelium owing to chemokines. In addition, there is increased Langerhans cell count in oral lichen planus (OLP) along with the up-regulation of MHC-II expression and consequent antigen presentation to CD4+ cells, which are activated by interleukin (IL)-12, that in turn activate CD8+ T cells via receptor interaction, interferon γ, and IL-2. Finally, CD8+ T cells activate and kill the basal keratinocytes through tumor necrosis factor-α. Andreason clinically classified OLP into six types namely the reticular, papular, plaque, ulcerative, erosive, and bullous of which papular and plaque types rarely present with any symptoms.[5] However, reticular, atrophic, erosive, and bullous types clinically present with pain and burning sensation. Malignant transformation rates of OLP range between 1% and 2%.[4,6]

Various treatment modalities have been employed such as corticosteroids, systemic or topical calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine (0.1%), Tacrolimus ointment (0.1%), immunosuppressive drugs such as Mycophenolate-mycophenolic acid (mycophenolate mofetil-500 mg). Triamcinolone acetonide (0.1%) and clobetasol (ointment 0.05%) are the most widely used corticosteroids.

The rationale for their usage is their ability of inflammatory and immune modulation.[7] Even though these drugs are prescribed routinely, they do have adverse effects such as adrenal suppression on systemic use and atrophy of epithelium, immunosuppression, and candidiasis on topical use. Topical corticosteroids remain one of the most promising therapies for OLP, till date. Studies have also shown that the primary goal of the treatment of OLP is symptomatic, i.e., reduction in burning sensation associated with the lesions.[6,8,9]

Besides, there is a rise in the prevalence of recalcitrant cases of OLP. Currently, herbal medicines such as coconut oil, sunflower oil, olive oil, aloe vera, and Tulsi are gaining more attention due to their minimal or no side effects.[10] Coconut (Cocos nucifera) is tropical produce (tree of life or kalpavriksha) known for centuries for its medicinal, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects are due to palmitic acid and lauric acid, respectively. The immunomodulatory effect is due to capric acid. Coconut oil has no adverse effects, is cost-effective, easily available, and easily extracted. Hence, this study was proposed to use coconut oil in the form of topical coconut cream to treat OLP due to its various beneficial properties.

Objectives of the study

The objective is to assess and compare the efficacy of topical coconut cream in the regression of size of the lesion and reduction of burning sensation among the patients with OLP.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of coconut (Cocos nucifera) 50% w/v cream

The topical coconut cream was prepared in the constituent College of Pharmacy of the University after purchasing 100% pure coconut oil (KLF Coconãd from KLF Nirmal Industries [P] Ltd., Kerala) from the market. Coconut oil was warmed to 600°C. Surfactant Span 60 of 2.5 ml was added and dissolved. The mixture was emulsified with surfactant tween 20 of 2.5 ml in a homogenizer for 10 min. Carbopol 940 about 1 g solution was dissolved in warm distilled water (25 ml). This solution was added to Coconut oil. This mixture was kept in a homogenizer for 15 s. Vanillin and triethanolamine (0.2 g) were added and triturated. The cream was then dispensed in airtight sterile plastic containers and stored at 4°C in a refrigerator [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Prepared coconut cream

Finally, the composition per 100 g of 50% coconut cream contained coconut oil (50 ml), tween 20 (surfactant-2.5 g), span 60 (surfactant-2.5 g), Carbopol 940 (gelling agent-1 g), triethanolamine (viscous organic compound-0.2 g) and vanillin (0.001 g).

Methodology

A total of 60 patients reporting to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology with the age of 18 years and above, of either sex, were included in the study after clinical confirmation of OLP according to Andreason[5] criteria and with prior informed consent. However, patients with other potentially malignant disorders and under treatment for the same, pregnant patients, lactating mothers, patients undergoing/who underwent some form of OLP treatment within 3 months, those with known allergy to any of the preparations, and patients with systemic diseases were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee (Ref. no: 29/04/2017/1108) and spanned over 1.5 years from November 2016 to May 2018.

The sample size was calculated to be 30 in each group using the formula n = 2s2 (Zα + Zβ)2 / d2 where Zα = 1.96 at 5% level, Zβ = 1.682 at 95% confidence interval. The patients were allocated to two groups (30 in each): I and II to receive 50% coconut cream and 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment respectively by randomization using the chit system (chits in concealed envelopes) by Examiner A. After recording the thorough case history, baseline recordings of lesion size and burning sensation were measured using Adobe Photoshop (version CS3) on clinical photographs and Numeric Pain Rating scale (NPS) respectively by Examiner B.

The patients were instructed to apply their respective medications twice a day with sterile cotton buds after breakfast and dinner for 1 month after the demonstration of the same by Examiner A. The patients were also given a treatment card on which he or she was asked to enter the daily application of the respective medication. The patients were asked to stop and report immediately in case of any adverse reactions. The clinical estimation of the size (total area) of the lesion was calculated by taking the two longest diameters measured over the software at baseline, 15th, 30th, and 60th day by Examiner B. The NPS scores ranged from 0 (no burning sensation) to 10 (extreme burning sensation). Thereby, both the patient and Examiner B were blinded to the medication being received by the patient. All the recordings at baseline, 15th, 30th, and 60th day were compiled and subjected to statistical analysis using IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS® Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Standardization of photographs

The clinical photographs were taken using Canon DSLR HD-100 in intelligent mode by a single researcher (Examiner B). A graph sheet was photocopied on a transparent OHP sheet which was later cut according to the size of the lesion and transferred onto it. Before transferring the sheet to the lesion, the lesion was dried with gauze and compressed air. Photographs were then made of the lesion with the 100 mm macro lens on the camera along with a proper illumination from a ring flash attached to it. The central ray of the camera was held perpendicular to the sheet on which the grid was copied. All the photographs were made keeping the viewpoint, positioning, lighting, color, magnification, contrast, and background common.

Results

On age distribution analysis, the maximum number of patients in Group I were of the age 41–50 years (36.67%) and least were of the age ≤30 years (16.67%). Whereas, the maximum number of patients in Group II were in the age group of 31–40 years (33.33%) and least in the age group ≤30 years (13.33%). The mean age of the patients in Group I and II was 44.63 and 42.57 years, respectively.

There were both female and male patients as participants in both Group I (8 males and 22 females) and Group II (10 males, 20 females).

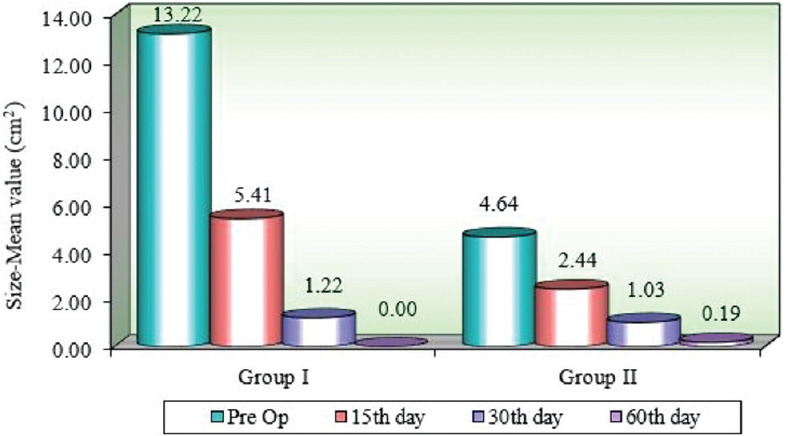

The mean size of lesion at baseline in Group I and Group II were 13.22 ± 3.33 cm2 and 4.64 ± 5.86 cm2 respectively.

Comparison of Group I and II concerning mean size of the lesion at different time intervals using the Mann–Whitney U test showed a significant decrease in the size of the lesion at the baseline, 15th, 30th, and 60th day (P < 0.05) but no significant change in the size of the lesion among the two groups was seen from the baseline to 60th day (P = 0.1516) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of Group I and Group II with mean size of lesion at different time points by Mann–Whitney U-test (P<0.05)

| Time point | Group I (cm2) | Group II (cm2) | U | Z | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Mean±SD | Sum of ranks | Mean±SD | Sum of ranks | ||||

| Pretreatment | 13.22±3.33 | 1010.50 | 4.64±5.86 | 819.50 | 354.50 | −1.4119 | 0.1580 |

| 15th day | 5.41±13.35 | 864.50 | 2.44±2.94 | 965.50 | 399.50 | −0.7466 | 0.4553 |

| 30th day | 1.22±4.17 | 800.50 | 1.03±1.64 | 1029.50 | 335.50 | −1.6928 | 0.0905 |

| 60th day | 0.00±0.00 | 855.00 | 0.19±0.75 | 975.00 | 390.00 | −0.8871 | 0.3751 |

| Pretreatment-15th day | 7.81±11.15 | 1085.00 | 2.19±4.57 | 745.00 | 280.00 | −2.5134 | 0.0120* |

| Pretreatment-30th day | 12.01±19.82 | 1056.00 | 3.60±5.00 | 774.00 | 309.00 | −2.0846 | 0.0371* |

| Pretreatment-60th day | 13.22±23.33 | 1012.00 | 4.44±5.36 | 818.00 | 353.00 | −1.4341 | 0.1516 |

*P<0.05. SD=Standard deviation

Comparison of different time points with the mean size of the lesion in Group I and II by Wilcoxon matched-pairs test showed a significant change in the lesion size at all time intervals with a mean difference between baseline and 60th day in Group I and II being 13.22 cm2 and 4.44 cm2 [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Comparison of different time points with mean size (cm2) of lesion in Group I and Group II

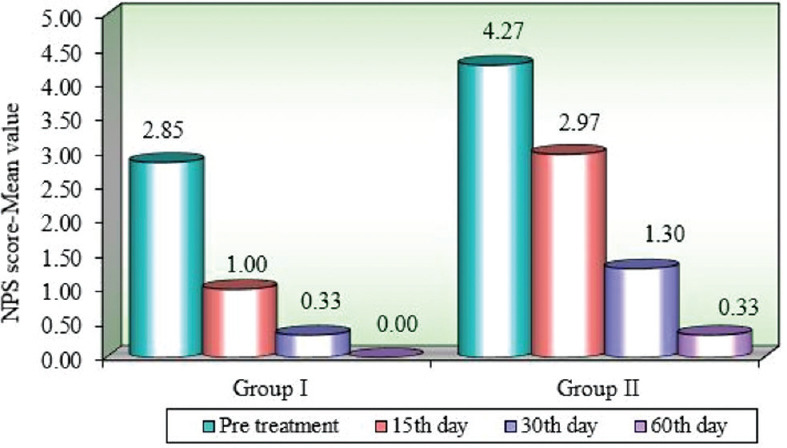

The mean value of burning sensation at the baseline in Group I and II were 2.85 and 4.27, respectively. Comparison of Group I and II with NPS scores a different time intervals using the Mann–Whitney U test depicted a significant reduction in both the groups with a better-controlled burning sensation in Group I compared to Group II on the 15th day [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of Group I and Group II with Numeric Pain Rating Scale at different time points by Mann–Whitney U-test (P<0.05)

| Time point | Group I | Group II | U | Z | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Mean±SD | Sum of ranks | Mean±SD | Sum of ranks | ||||

| Pretreatment | 2.85±2.91 | 805.50 | 4.27±3.47 | 1024.50 | 340.50 | −1.6189 | 0.1055 |

| 15th day | 1.00±1.95 | 713.00 | 2.97±2.98 | 1117.00 | 248.00 | −2.9865 | 0.002* |

| 30th day | 0.33±1.27 | 811.00 | 1.30±2.26 | 1019.00 | 346.00 | −1.5376 | 0.1242 |

| 60th day | 0.00±0.00 | 870.00 | 0.33±1.06 | 960.00 | 405.00 | −0.6653 | 0.5059 |

| Pretreatment-15th day | 1.85±2.09 | 932.50 | 1.30±0.92 | 897.50 | 432.50 | −0.2587 | 0.7958 |

| Pretreatment-30th day | 2.52±2.62 | 847.50 | 2.97±2.27 | 982.50 | 382.50 | −0.9979 | 0.3183 |

| Pretreatment-60th day | 2.85±2.91 | 825.50 | 3.93±3.13 | 1004.50 | 360.50 | −1.3232 | 0.1858 |

*P<0.05. SD=Standard deviation

Comparison of different time points with NPS scores in Group I and II by Wilcoxon matched-pairs test presented a significant reduction of burning sensation in both the groups from baseline to 15th, 30th, and 60th day. But when compared between Group I and II, the former showed better results especially at baseline to 15th day proving it to be better in an immediate reduction of burning sensation compared to the latter [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Comparison of different time points with Numeric Pain Rating scale scores in Group I and Group II

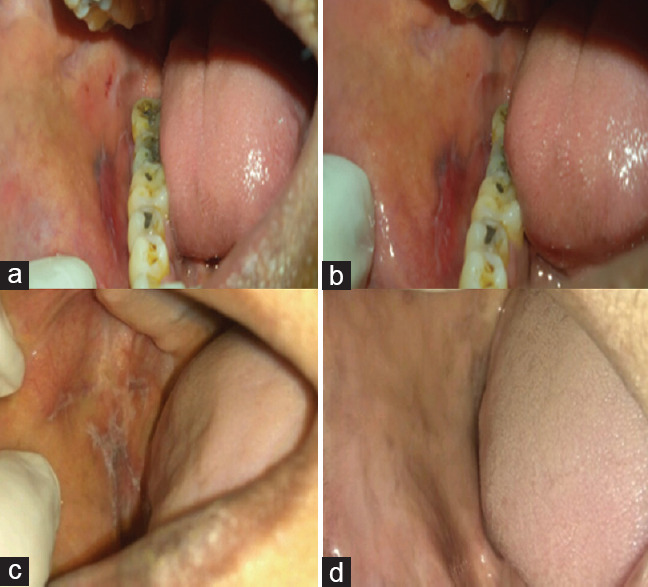

There was an 85% regression in the size of the lesion in Group I as compared to 95% in Group II and was a 100% reduction in the NPS score in Group I as compared to 95% in Group II [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Clinical presentation of oral lichen planus in- (a) Group I at the baseline (b) Group I after 60 days of coconut cream therapy (c) Group II at the baseline (d) Group II after 60 days of 0.05 % clobetasol propionate therapy

Discussion

OLP is an oral potentially malignant chronic inflammatory disorder associated with pain and burning sensation. The mainstay for the treatment of OLP is the administration of systemic or topical corticosteroids. Clobetasol ointment (0.05%) is the most widely used corticosteroid for the management of OLP. The rationale for its usage is its ability to modulate the inflammation as well as immune response.[11] Even though standard drug Clobetasol is prescribed, it has adverse effects such as adrenal suppression on long-term systemic use, atrophy of epithelium, and candidiasis on topical use. The adverse effects of Clobetasol propionate (0.05%) mouthwash include moon face and hirsutism between week 4 and week 6 of treatment.[12] Fluticasone propionate spray is known to cause minor adverse effects such as bad smell and taste, nausea, xerostomia, swollen mouth, sore throat, and candidiasis.[11,13] However, candidiasis due to fungal overgrowth was the only common side effect of topical triamcinolone acetonide application.[13] Concurrently, there is also a rise in prevalence of recalcitrant cases of OLP as seen by Thongprasom K and Dhanuthai K who presented that Topical tacrolimus (0.1%) ointment showed an improved therapeutic response initially than triamcinolone acetonide, but frequent relapses occurred within 3–9 weeks after the cessation of therapy and the most common side effect noted from both the drugs was temporary stinging or burning sensation at the application site of topical drug.[13] This demands a search for a safe, promising, and cost-effective alternative medication. Herbal extracts have been gaining attention in the recent past because of their minimal or no side effects. Coconut is a tropical tree known for its medicinal, nutritional values along with potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties. As per literature, coconut oil therapy is found to be effective for alleviating the symptoms in different oral conditions such as denture stomatitis, gingivitis, and mucositis.[14,15] It has been proved that coconut oil has various other potential benefits such as anticancer property,[16] hepatoprotective property,[17] reduction of body fat, fastening the metabolism,[18] and reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases like hypertension and atherosclerosis.[19]

Hence, coconut cream was proposed to be used and compared with the gold standard clobetasol propionate in this study.

The mean age of occurrence of OLP in Group I was 44.63 years and in Group II was 42.57 years which is consistent with the study by Malhotra et al. where the mean age of patients was 40–50 years among 49 patients.[20]

However, many studies have reported that the mean age of patients of OLP patients ranges from 55 to 65 years, but the recent trend has reported the age of occurrence of this disease to be as low as 28 years. This can be attributed to an increased level of stress at a younger age, as stress is one of the etiological factors for the causation of OLP.

The current study included patients of either gender as study participants. Among 60 patients with OLP, there were 70% females and 30% males indicating a female predominance which was in accordance with Varghese et al. who had 65% females and 35% males.[21]

In the current study, the mean size of the lesion in Group II at the baseline was 4.64 cm2 and on the 30th day was 1.03 cm2 which was in accordance to Radfar et al. where lesion size was reduced from a mean of 4.93 cm2 to 0.906 cm2 on 6th week in 0.05% clobetasol propionate group.[22]

The mean burning sensation of the lesion in Group II at the baseline was 4.27 and 1.30 on the 30th day which was in accordance with Carbone M et al., where burning sensation was reduced from a mean of 2.38 to 1.13 on the 30th day after 0.05% clobetasol propionate application.[23]

In the current study, the mean size of the lesion in Group I at the baseline was 13.22 cm2 and on the 30th day was 1.22 cm2 which was in accordance to Amirchaghmaghi Met al., where 250 mg of quercetin hydrate was administered to patients of Group A and lesion size was reduced from a mean of 9.40 cm2 to 4.73 cm2 on 30th day.[24]

The mean burning sensation of the lesion in Group I at the baseline and 30th day was 2.85 and 0.33, respectively. Similar findings were found in the study conducted by Amirchaghmaghi M et al., where 250 mg of quercetin hydrate was administered to patients of Group A and burning sensation was reduced from a mean of 1.92 to 0.53 on 30th day.[24]

Peedikayil et al. evaluated the effect of coconut oil pulling/oil swishing on plaque formation and plaque-induced gingivitis and revealed that the baseline mean gingival and plaque index were 0.91 and 1.19, respectively. The average gingival index score on the 30th day was reduced to 0.401 and the plaque index score to 0.385 respectively.[15] Verallo-Rowell et al. compared the effect of virgin coconut oil and virgin olive oil in adult atopic dermatitis and concluded that there is a significant difference posttreatment for both oils but the effect was greater with virgin coconut oil for the treatment of skin infections.[25]

Singla et al. revealed that there was a significant decrease in the mean Streptococcus mutans count from 5.62 to 2.06, Lactobacillus count from 4.57 to 1.04, plaque scores from 1.27 to 0.74, and gingival scores from 1.49 to 0.79 after 10 min from coconut oil gum massage therapy. Thus, it was clear that coconut oil is promising as a valuable preventive agent for the maintenance and improvement of oral health.[26]

Coconut cream is a very safe, promising, and cost-effective medication for the treatment of OLP as seen from the present study. The burning sensation had significantly reduced within 2 weeks of topical application of Coconut cream more effectively than the clobetasol propionate. Furthermore, there was a significant decrease in the size of the lesion as well.

Limitations

The limitations of the coconut cream are the need for a refrigerator for storage and short shelf life of 6 months due to the risk of moisture contamination which can be overcome by adding preservatives without affecting the therapeutic property. The limitations of the study were a smaller sample size and short patient follow-up period.

Conclusion

The study concluded that coconut cream showed significant regression in the size of the lesion as well as a reduction in the burning sensation in OLP patients without any side effects or adverse reactions. This could be because of the potent anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and wound healing properties of coconut cream which alleviated the signs and symptoms in OLP patients. Coconut cream appears to be a safe and promising cost-effective medication for the treatment of OLP. However, further studies should be carried out with a larger sample size for a longer follow-up period along with the evaluation of its mucosal substantivity and saliva factors influencing its stability quotient in topical form.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Shivalingappa B Javali, Associate Professor in Statistics for statistical analysis and Dr. U B Bolmal, Assistant Professor of Pharmaceutics for the preparation of Coconut cream.

References

- 1.Hui RL, Lide W, Chan J, Schottinger J, Yoshinaga M, Millares M. Association between exposure to topical tacrolimus or pimecrolimus and cancers. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1956–63. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisen D, Carrozzo M, Bagan Sebastian JV, Thongprasom K. Number V Oral lichen planus: Clinical features and management. Oral Dis. 2005;11:338–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez-Moles MA, Morales P, Rodriguez-Archilla A, Isabel IR, Gonzalez-Moles S. Treatment of severe chronic oral erosive lesions with clobetasol propionate in aqueous solution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:264–70. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.120522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decani S, Federighi V, Baruzzi E, Sardella A, Lodi G. Iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome and topical steroid therapy: Case series and review of the literature. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:495–500. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2012.755252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreasen JO. Oral lichen planus. 1. A clinical evaluation of 115 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:31–42. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: Report of an international consensus meeting. Part 1. Viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canto AM, Müller H, Freitas RR, Santos PS. Oral lichen planus (OLP): Clinical and complementary diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:669–75. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scully C, Eisen D, Carrozzo M. Management of oral lichen planus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:287–306. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan ES, Thornhill M, Zakrzewska J. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD001168. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Meij EH, Schepman KP, Smeele LE, van der Wal JE, Bezemer PD, van der Waal I. A review of the recent literature regarding malignant transformation of oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:307–10. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavanya N, Jayanthi P, Rao UK, Ranganathan K. Oral lichen planus: An update on pathogenesis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:127–32. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.84474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed I, Nasreen S, Jehangir U, Wahid Z. Frequency of oral lichen planus in patients with noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2012;22:30–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thongprasom K, Dhanuthai K. Steriods in the treatment of lichen planus: A review. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:377–85. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.50.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DebMandal M, Mandal S. Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.: Arecaceae): In health promotion and disease prevention. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4:241–7. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peedikayil FC, Sreenivasan P, Narayanan A. Effect of coconut oil in plaque related gingivitis – A preliminary report. Niger Med J. 2015;56:143–7. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.153406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamalaldin NA, Yusop MR, Sulaiman SA, Yahaya BH. Apoptosis in lung cancer cells induced by virgin coconut oil. Regen Res. 2015;4:30–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zakaria ZA, Rofiee MS, Somchit MN, Zuraini A, Sulaiman MR, Teh LK, et al. Hepatoprotective activity of dried- and fermented-processed virgin coconut oil. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:142739. doi: 10.1155/2011/142739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuji H, Kasai M, Takeuchi H, Nakamura M, Okazaki M, Kondo K. Dietary medium-chain triacylglycerols suppress accumulation of body fat in a double-blind, controlled trial in healthy men and women. J Nutr. 2001;131:2853–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vala GS, Kapadiya PK. Medicinal benefits of coconut oil (A review paper) IJLSCI. 2014;2:124–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malhotra AK, Khaitan BK, Sethuraman G, Sharma VK. Betamethasone oral mini-pulse therapy compared with topical triamcinolone acetonide (0.1%) paste in oral lichen planus: A randomized comparative study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varghese SS, George GB, Sarojini SB, Vinod S, Mathew P, Mathew DG, et al. Epidemiology of oral lichen planus in a cohort of South Indian population: A retrospective study. J Cancer Prev. 2016;21:55–9. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2016.21.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radfar L, Wild RC, Suresh L. A comparative treatment study of topical tacrolimus and clobetasol in oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carbone M, Arduino PG, Carrozzo M, Caiazzo G, Broccoletti R, Conrotto D, et al. Topical clobetasol in the treatment of atrophic-erosive oral lichen planus: A randomized controlled trial to compare two preparations with different concentrations. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:227–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amirchaghmaghi M, Delavarian Z, Iranshahi M, Shakeri MT, Mosannen Mozafari P, Mohammadpour AH, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled double blind clinical trial of quercetin for treatment of oral lichen planus. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2015;9:23–8. doi: 10.15171/joddd.2015.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verallo-Rowell VM, Dillague KM, Syah-Tjundawan BS. Novel antibacterial and emollient effects of coconut and virgin olive oils in adult atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2008;19:308–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singla N, Acharya S, Martena S, Singla R. Effect of oil gum massage therapy on common pathogenic oral microorganisms – A randomized controlled trial. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:441–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.138681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]