Abstract

Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) for the SARS-CoV-2 virus in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) has emerged as a cost-effective and unbiased tool for population-level testing in the community. In the present study, we conducted a 6-month wastewater monitoring campaign from three WWTPs of different flow rates and catchment area characteristics, which serve 28 % (2.1 million people) of Hong Kong residents in total. Wastewater samples collected daily or every other day were concentrated using ultracentrifugation and the SARS-CoV-2 virus RNA in the supernatant was detected using the N1 and E primer sets. The results showed significant correlations between the virus concentration and the number of daily new cases in corresponding catchment areas of the three WWTPs when using 7-day moving average values (Kendall's tau-b value: 0.227–0.608, p < 0.001). SARS-CoV-2 virus concentration was normalized to a fecal indicator using PMMoV concentration and daily flow rates, but the normalization did not enhance the correlation. The key factors contributing to the correlation were also evaluated, including the sampling frequency, testing methods, and smoothing days. This study demonstrates the applicability of wastewater surveillance to monitor overall SARS-CoV-2 pandemic dynamics in a densely populated city like Hong Kong, and provides a large-scale longitudinal reference for the establishment of the long-term sentinel surveillance in WWTPs for WBE of pathogens which could be combined into a city-wide public health observatory.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, WWTP, Longitudinal monitoring, WBE

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the large-scale testing is essential to identify infectious patients in a population and to timely control viral transmission. Testing of individuals by nucleic acid assays such as reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is the current diagnostic gold-standard with high sensitivity and specificity, but it is restricted with lagged turnaround time, limited testing capacity, and high resource-intensive for testing millions of people in the community (Mercer and Salit, 2021). Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) for SARS-CoV-2 is being considered as a promising and cost-effective tool in screening pandemics progressing at a population-wide scale, and has been used in public health invention, such as giving early warning signals before the pandemic outbreak (Medema et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021), tracking infection dynamics (Graham et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021), evaluating policy effectiveness (Hillary et al., 2021; Wurtzer et al., 2020), near-source tracking to find out infected patients (Betancourt et al., 2021; Deng et al., 2022b) and identifying new variants in the community (Deng et al., 2022a; Xu et al., 2022a). These finding emphasized the importance of incorporating wastewater surveillance into SARS-CoV-2 detection strategies for the public health response.

Over the past two years, >60 countries across the globe establish tailored detection protocols and scale them up for long-term wastewater surveillance networks for SARS-CoV-2 viruses (Naughton et al., 2021), such as European Sewage Sentinel System for SARS-CoV-2 (Gawlik et al., 2021), National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) in USA (Kirby et al., 2021), National COVID-19 Wastewater Epidemiology Surveillance Programme (N-WESP) in UK (https://nwesp.ceh.ac.uk/), and a territory-wide wastewater surveillance system in Hong Kong SAR, China (Deng et al., 2022a), etc. Numerous datasets generated in these global wastewater surveillance campaigns and challenge has been raised on the interpretation of temporal wastewater monitoring datasets for the public health information. The applicability of WBE into tracking community infection dynamics have been demonstrated in USA (Gonzalez et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2021; Karthikeyan et al., 2021; Peccia et al., 2020; Sherchan et al., 2020), Australia (Ahmed et al., 2021b), Switzerland (Fernandez-Cassi et al., 2021), India (Kumar et al., 2021), Bangladesh (Jakariya et al., 2021), Nepal (Tandukar et al., 2022), Singapore (Wong et al., 2021), etc. Although there are various methods to capture the spatiotemporal trends, the interpretation of wastewater data and the method sensitivity are site-specific due to multiple reasons (Fitzgerald et al., 2021).

In addition, it is suggested that normalization of SARS-CoV-2 virus signal to flow rates, or endogenous biomarkers could reduce wastewater surveillance variability of the operating process to strengthen the correlation (D'Aoust et al., 2021; Wolfe et al., 2021). Among the candidate biomarkers, PMMoV and CrAssphage displayed less variation and were more consistent in wastewater samples (Greenwald et al., 2021). Considering PMMoV virus is an RNA virus while crAssphage is a DNA virus, PMMoV virus was used in the present study for normalization because it is consistent with SARS-CoV-2 virus in nucleic acid extraction procedures and has the potential to serve as process control. However, other studies presented the opposite opinions toward the effectiveness of normalization, showing it makes no difference or even reduces the correlation after normalization (Feng et al., 2021). Thus, it is still unclear yet about the effect of normalization using biomarkers on the quantification of SARS-CoV-2 virus concentration and its correlation with the number of clinical cases.

In the present study, we performed a half-year longitudinal wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA across three WWTPs to monitor infection dynamics during the 4th wave of the pandemic outbreak in Hong Kong, China. The aims are to address the following aspects: (1) quantification of virus concentrations in the supernatant and the pellet of the wastewater samples; (2) correlation between wastewater virus concentration and case number within the catchment areas of WWTPs; (3) comparison of the viral concentration dynamics of different WWTPs after normalization using the daily flow rates and fecal indicator (e.g. PMMoV) concentration; and (4) comparison of the COVID-19 prevalence rates derived from the wastewater and clinical data.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples collection

Wastewater samples were collected from three WWTPs, i.e. Northwest Kowloon Preliminary Treatment Works (NWK), Sha Tin Sewage Treatment Works (ST), and Shek Wu Hui Sewage Treatment Works (SWH) in Hong Kong SAR, China (Fig. 1 ). These three WWTPs serve populations of 1.16 million, 0.65 million, and 0.29 million respectively, accounting for 28 % of Hong Kong residents in total. NWK had an average flow rate of 0.348 million m3/day and was connected to the largest WWTP in Hong Kong, Stonecutters Island Sewage Treatment Works. There are three hospitals receiving COVID-19 patients and four designated quarantine hotels within the NWK catchment area during the sampling period. ST and SWH provide secondary treatment with the average flow rates of about 0.26 million m3/day and 0.087 million m3/day, respectively. Both ST and SWH have a hospital receiving COVID-19 patients in their catchment areas, but no designated quarantine hotels during the study period. The 24 h flow-weighted composite samples were taken by Drainage Services Department (DSD) daily from NWK and every other day from both ST and SWH. From December 24, 2020 to June 30, 2021, 185, 79, and 80 samples were collected from NWK, ST and SWH, respectively. All collected wastewater samples were stored at a 4 °C refrigerator before delivery to the laboratory for processing once a week.

Fig. 1.

Description of sampling information in the three WWTPs. (a) Sampling period from December 24, 2020 to June 30, 2021. (b) Geoinformatics data. (c) Sampling locations and catchment areas.

2.2. Pretreatment of the samples

After arriving the laboratory, wastewater samples were heat-inactivated at 60 °C for 30 min to ensure lab safety (Chin et al., 2020). After that, for each sample, 40 mL wastewater were centrifuged at 4750 ×g for 30 min on Allegra X-15R Centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) to separate wastewater into two subsamples, i.e. supernatant and pellet. Next, 30 mL supernatant was concentrated through ultracentrifugation at 150,000 ×g for 60 min at 4 °C on Optima XPN Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) to obtain the concentrated sample (approximately 200 μL). Pellet from 40 mL wastewater was resuspended by the remaining wastewater (approximately 1.5 mL) and transferred into a new 2 mL micro-centrifugal tube for further centrifugation at 20,000 ×g for 2 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed carefully without disturbing the pellet.

2.3. RNA extraction

RNA of the concentrated samples from 30 mL supernatant or 40 mL pellet was extracted using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) on the auto-extraction platform QIAcube Connect (Qiagen), with the final elution volume of 50 μL. For QA/QC, 200 μL AVE from the extraction kit was used as the reagent blank in parallel for each batch of eleven samples. Paired supernatant and pellet samples from NWK from March 9 to July 7, 2021 were extracted to compare the viral loads.

2.4. RT-qPCR detection

One-step RT-qPCR targeting SARS-CoV-2 N1 (CDC, 2020) and E (Corman et al., 2020) was used for the detection and quantification of virus RNA concentrations with the same reagents and recommended annealing temperatures as described before (Deng et al., 2022a; Xu et al., 2022b). In detail, 4 μL RNA template was used for running 45 cycles in 20 μL reaction mixture on the Applied Biosystems ViiA7 qPCR machine (Thermo Fisher), together with 5 μL TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix (Thermo Fisher), primers and probe concentration of 500 nM and 250 nM, respectively. DEPC water as no-template controls (NTCs), DNA plasmids as positive control were included for every batch, and each sample and control were detected in duplicate. Samples were considered to have a virus signal if the Ct value was <40, and its virus concentration was calculated according to the plate-specific standard curve established by ten-fold serial dilution of the synthetic DNA plasmid from 106 to 100 copies/reaction. When the detected copy number is <1 copy/reaction, the value of “167 copies/L” was used as the virus concentration, corresponding to half of the theoretical detection limit value of 333 copies/L.

A one-step PMMoV RT-qPCR assay was performed to quantify the PMMoV concentration from both supernatant and pellet samples (Greenwald et al., 2021). Each 20 μL reaction mixture consists of 4 μL RNA template, 5 μL TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix, 500 nM primers, 250 nM probe, and DEPC-treated water. The thermocycling conditions were UNG incubation for 2 min at 25 °C, RT-step for 15 min at 50 °C and polymerase activation for 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 45 cycles of 3 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 55 °C on the Applied Biosystems ViiA7 qPCR machine (Thermo Fisher). The establishment of the standard curve and QA/QC practice were the same as the detection of N1 and E primer sets mentioned above.

2.5. COVID-19 epidemiological data

The geographic information of WWTPs is available on Geoinfo Map (https://www.map.gov.hk/gm/map/s/d/mM8DMOPE). All visited/resided buildings of confirmed COVID-19 cases locations and population size information was downloaded from Hong Kong Geodata Store (https://geodata.gov.hk/gs/). Confirmed COVID-19 cases within WWTPs catchment areas were extracted using ArcGIS Pro 2.8.0. The hospitalized date and discharge date of each COVID-19 case were provided by the Centre for Health Protection (CHP) of Hong Kong. Daily new cases were defined as confirmed cases admitted to the hospital on the day of sampling. During the 4th wave pandemic outbreak in Hong Kong, all the patients with COVID-19 were hospitalized on the same day or 1 to 2 days before official reporting date.

2.6. Calculation of prevalence rates

Daily SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the samples was calculated by the detected virus concentration multiplying the daily flow rates, that is:

| (1) |

COVID-19 prevalence rates from wastewater data (Pww) were calculated according to the Eq. (2).

| (2) |

Two definitions of clinical prevalence rates were used in this study, that is, prevalence of daily new cases (Pdaily) and prevalence of total new cases and convalescent patients within 7 days of sampling date (Pweekly) according to Eqs. (3), (4).

| (3) |

| (4) |

where,

L: viral load (copies/day);

C: SARS-CoV-2 virus concentration in the supernatant of the 24 h flow-weighted composite samples calculated using the N1 primer-probe set (copies/L);

Q: flow rate (m3/day, corresponding to 103 L/day);

S: virus shedding in the stool of an infected person, assuming 108 copies/mL (according to 102–108 copies/mL reported in Zheng et al (Zheng et al., 2020), and range of 102.7–107.8 copies/mL reported in Wolfel et al (Wolfel et al., 2020));

ρ: stool density, assuming 1.06 g/ mL (according to 1.06–1.09 g/mL reported in Penn et al (Penn et al., 2018));

W: stool weight, assuming 128 g/day (the median value in the range of 35–796 g/day reported in Penn et al (Penn et al., 2018)).

N: the population size in the catchment area of the WWTP.

Number of daily new cases: defined as those patients with COVID-19 hospitalized on the same date of the sampling date.

Number of weekly cumulative total cases: number of total cases contributing to virus signals in wastewater samples, defined as the cumulative number of daily new cases within 7 days after sampling date and convalescent patients within 7 days before sampling date.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Non-parametric Kendall's tau-b coefficient was used to evaluate the correlation among different measurements. Statistical analysis was performed using R Studio version 1.3.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. RT-qPCR performances

The standard curves used in this study meet with Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiment (MIQE) guidelines (Bivins et al., 2021) (Supporting Information Table S1).

High correlation between N1 and E primer-probe sets was observed among a total of 344 wastewater samples (Kendall's tau-b = 0.493, p < 0.0001), representing the agreement of these two detection assays. The N1 set obtained higher virus concentration than E set in more wastewater samples and showed higher correlation values with daily new case number than E set. Additionally, the qualitative detection results between the supernatant and the pellet were more consistent for N1 than E set. These results implied that N1 set was more robust for detection, quantification and data interpretation, thereby only this target gene was used to calculate the wastewater-derived prevalence rate in the subsequent analysis of the present study. Similarly, N1 gene detection was reported to be more sensitive than E gene assay and adopted in the national Scotland wastewater surveillance (Fitzgerald et al., 2021).

3.2. Comparison of the supernatant and the pellet

We compared paired supernatant and pellet of 91 wastewater samples collected in NWK for N1, E, and PMMoV measurements. The physicochemical wastewater parameters in NWK was summarized in Table S2. Higher detection rates were detected in the supernatant rather than the pellet, for both N1 and E sets (Fig. 2a). The detection rates were the same for PMMoV virus in supernatant and pellet, but significantly lower Ct value was observed in supernatant rather than pellet, with the average Ct values of 22.35 ± 1.89 and 27.43 ± 1.64, corresponding to 10-fold higher virus concentration in the supernatant (Fig. 2b and Fig. 2c). Therefore, detection of viruses in the supernatant using the two-step ultracentrifugation method is more effective, robust and sensitive than detection of those in the pellet obtained using low-speed centrifugation if starting from the same volume of wastewater.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the supernatant and the pellet. (a) Detection rates and Ct value in SARS-CoV-2 using N1 and E assays, and PMMoV; (b) Ct value of PMMoV. (c) PMMoV concentrations (copies/L).

This result was consistent with that obtained using inactivated SARS-CoV-2 spiked wastewater samples in Canada (Chik et al., 2021) and Japan (Alamin et al., 2022), but differed from those studies using wastewater samples from a Finland WWTP (Hokajarvi et al., 2021) and a California WWTP (Graham et al., 2021). Such inconsistency could be due to multiple reasons. Firstly, the centrifugation speed for the separation of particles from wastewater in the protocol will lead to the difference in the definition of the “supernatant” and “pellet”, deciding the partition of virus particles in these two parts. In the present study, low-speed centrifugation (4750 ×g for 30 min) was used to separate the supernatant and the pellet, while high-speed centrifugation (24,000 ×g for 15 min) was applied in the California WWTP (Graham et al., 2021). Secondly, the recovery efficiency of different virus concentration methods used to concentrate virus from the supernatant also contribute to the partition difference between the supernatant and the pellet. The virus recovery efficiency of ultrafiltration used in Finland's study (Hokajarvi et al., 2021) was only half of that of ultracentrifugation method used in the present study based on our previous method evaluation using Hong Kong wastewater (Zheng et al., 2022). Overall, using the supernatant or the pellet for SARS-CoV-2 virus detection may need to be selected specifically for the local wastewater samples with the considerations of the sampling sites, separation methods, and virus concentration methods.

3.3. Longitudinal trends and influencing factors

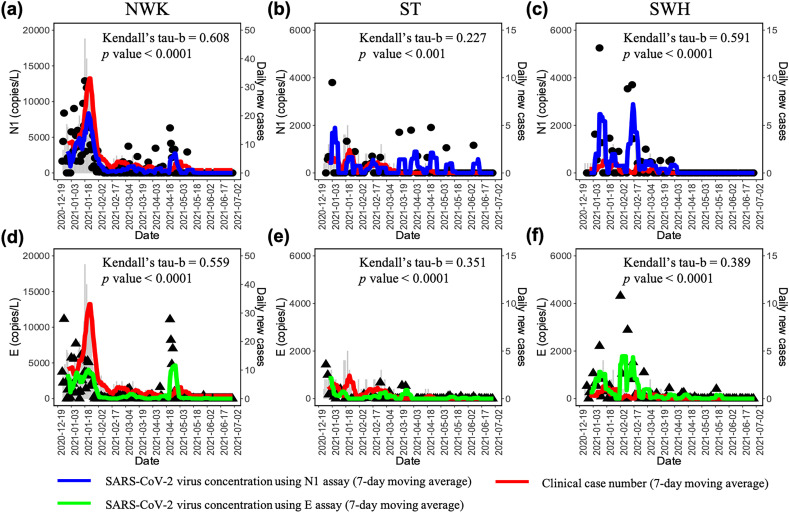

Wastewater surveillance monitoring was conducted from December 24, 2020 to June 30, 2021 using the influent of the three WWTPs of Hong Kong, which captured the bimodal upward and downward trends of clinical cases (Fig. 1a). The detection rates of N1 primer-probe set were 40.5 % (75/185) for NWK, 22.8 % (18/79) for ST and 21.3 % (17/80) for SWH, respectively. Similar detection rates across three WWTPs were obtained using E primer-probe set (Table S3). For both N1 and E sets using raw measurement, daily virus concentrations were significantly correlated with the daily new case numbers for NWK (Kendall's tau-b = 0.500 for N1 and Kendall's tau-b = 0.471 for E, p < 0.0001), but showed insignificant correlations for ST and SWH (p > 0.05). Using 7-day moving average values, both N1 and E virus concentrations were observed to be significantly correlated with the daily new case numbers within the wastewater catchment areas of the three WWTPs (Fig. 3 , Kendall's tau-b = 0.227–0.608, p < 0.001). This implied the effectiveness of wastewater data to reflect the infection dynamics after smoothing using the moving average value.

Fig. 3.

Longitudinal measurements of SARS-CoV-2 virus concentrations in wastewater samples using N1 and E detection assays, and their correlations with the number of daily new cases in the catchment areas of the three WWTPs. Red line: the clinical daily new cases number using 7-day moving average value. Blue line: the virus concentration (N1) using 7-day moving average value. Green line: the virus concentration (E) using 7-day moving average value.

The data smoothing facilitated establishing the correlation by reducing variation of dataset. With the increase of smoothing days, higher correlation values were obtained for both N1 and E sets across three WWTPs, and 7-day moving average were recommended. Similarly, smoothing dataset with 7-day moving window was also applied in wastewater data trend interpretation and obtained significant correlated trendlines in USA (Feng et al., 2021), Canada (D'Aoust et al., 2021) and Spain (Rusinol et al., 2021).

In addition, the sampling strategy is always a trade-off between limited resources and effectiveness of wastewater surveillance to track the pandemic dynamics. Here, we also use down-sampling simulated dataset to determine which sampling frequency could reduce sampling effort without the loss of tracking significant trendlines. Using the 6-months high-resolution daily sampling dataset of NWK, down-sampling results showed that decreasing sampling frequency generally would lead to lower correlation significance probably due to the higher randomness (Fig. S1). All simulated datasets sampled per up to 4 days presented significant correlations as that of the daily sampling dataset (p < 0.01), whereas several simulated datasets sampled at >4 days intervals showed insignificant correlation (p > 0.05). These results indicated that the minimum sampling frequency for SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance is at least twice a week, which was consistent with an evaluation result in another study using the primary sludge at a large WWTP (Graham et al., 2021). This sampling frequency had been adopted in the design of sentinel wastewater surveillance network in Hong Kong (Deng et al., 2022a) and was also recommended by European Union in its document to its member states regarding wastewater surveillance systems for SARS-CoV-2 (European Union, 2021). The sampling frequency needs to be re-evaluated when the virus concentrations change dramatically and new virus variants emerge in the community.

Some other factors may also contribute to track the trendline but cannot be evaluated in the present study, such as the sampling strategy and the clinical testing capacity. For example, compared with 3-hour composite samples or grab samples at specific peak timepoints, 24-hour composite samples which was used in the present study would be more representative with higher probability to capture virus shedding of patients, but the virus signals could be diluted (Ahmed et al., 2021a). In addition, limited clinical diagnostic testing capacity may lead to lower cases identified, unfavorable for the establishment of the correlation with wastewater results (Duvallet et al., 2021).

3.4. Effect of normalization by PMMoV and flow rates

Using the raw measurement, no matter whether normalized or not against PMMoV or daily flow rates, significant correlations were observed between N1 or E results with the number of clinical cases in the catchment area of NWK (Table 1 ). Conversely, no significant correlations displayed for ST and SWH before and after normalization for both PMMoV and flow rates. In addition, the correlation values showed no obvious change after normalization by daily flow rate but were slightly decreased after normalization by PMMoV. After smoothing with 7-day moving average, normalization still yielded similar correlation results as those without normalization. These results indicated that the normalization could not assist tracking trendline between wastewater data and the number of clinical cases for the three WWTPs in Hong Kong.

Table 1.

Kendall's tau-b coefficients between the virus concentration before/after normalization and the daily new cases number. The grey color indicates the insignificantly correlations (p value >0.05).

Similarly, normalization of SARS-CoV-2 virus signals by PMMoV virus did not strengthen the correlation with the number of clinical cases for a few US WWTPs (Feng et al., 2021; Graham et al., 2021). The usage of PMMoV for normalization is on the basis of its potential to present consistent virus concentration value for a catchment area with a stable population size. However, in the present study, PMMoV concentration shows significant temporal variation within individual WWTP, with the relative standard deviation (RSD) value of 57.3 %, 57.8 % and 118.3 % for NWK, ST and SWH (Fig. S2). Additionally, PMMoV is non-enveloped virus while SARS-CoV-2 virus is enveloped virus, which could influence viral partition behaviors in the wastewater samples and the recovery efficiency for virus concentration methods (Ye et al., 2016). For the above reasons, using PMMoV as a surrogate for normalization to mitigate the variation of SARS-CoV-2 during sample processing process is still very challenging.

Despite the limitation of PMMoV as a quantitative surrogate for normalization, it still could serve as an effective qualitative internal indicator for the process control. Presence of PMMoV indicates the human fecal sources for the extracted RNA of wastewater samples. In the present study, SARS-CoV-2 virus concentration dataset was omitted as outliers when PMMoV virus was undetectable. Similarly, PMMoV viral load was also used as an internal process control for detecting anomalies dataset in another study (Huisman et al., 2021). Overall, although PMMoV measurement may not be able to serve as a suitable normalization biomarker to strengthen the trendline, it could be leveraged as an internal quality control for wastewater samples in the testing process of SARS-CoV-2.

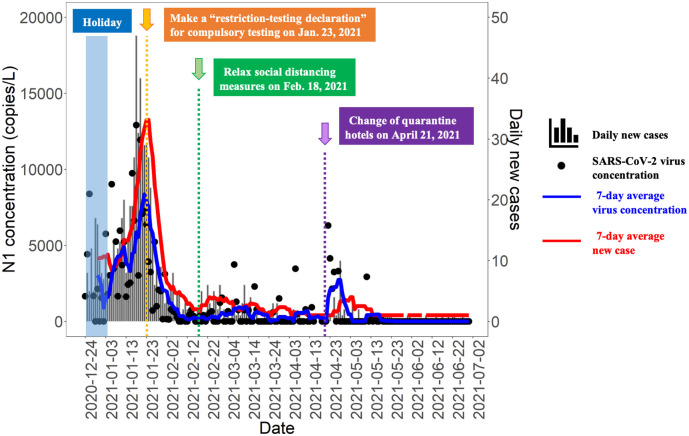

3.5. Interpretation of wastewater data with epidemiological scenarios

We explored the change of wastewater data of NWK serving a population size of around 1.16 million with the related epidemiological scenarios of Hong Kong (Fig. 4 ). After public holidays (Christmas and New Year) from December 24, 2020 to January 3, 2021, there was a simultaneous rapid increase in wastewater virus signals and daily new cases, suggesting the pandemic development due to holiday gatherings. To strengthen the effort to cut off hidden transmission chains in the community, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China made a restriction-testing declaration (RTD) in Yau Ma Tei to Jordan for compulsory testing on January 23, 2021 (GovHK, 2021c), which means all the residents within the RTD area were subject to compulsory testing and stay at home until receiving negative results of each resident within 48 h before January 25, 2021 (Monday). After that, the declines of daily new cases from January 19, 2021 to February 12, 2021 was observed, which was also reflected in reduced virus concentrations in wastewater samples. Later, on February 18, 2021, the Government started to relax social distancing measures (GovHK, 2021b), and a slight increase of wastewater virus concentration and daily new cases in the following days was observed, while the pandemic was still under control. Another increase of the virus concentration in wastewater started from April 21, 2021, which may be due to more travelers residing in the four designated quarantine hotels within NWK catchments after three Yau Tsing Mong designated quarantine hotels outsides NWK stopped receiving travelers (GovHK, 2021a).

Fig. 4.

The SARS-CoV-2 concentration (using N1 set) in the supernant of the NWK wastewater samples and its correlation with the pandemic outbreak and the policy change.

The wastewater trend in NWK catchment area coincided with epidemic events and policy change of Hong Kong. This finding indicated that WBE is a powerful tool to monitor the virus circulation at the community level for a densely populated city like Hong Kong. The WBE tool has an advantage over clinical testing in reflecting policy impacts regarding the sampling effort, testing capacity, and sampling frequency for large-scale population size. This finding also suggested that, if using carefully, WBE could assist decision makers to monitor the effectiveness of the public health interventions in a real-time manner.

Also, the results in the present study demonstrated the higher sensitivity of our method which could obtain high detection rate (40.5 %) for <50 daily new cases from over 1 million people in the catchment area, better than the detection limit of infection cases per 100,000 in other studies, for example, 25 cases in Scotland (Fitzgerald et al., 2021), and 13 cases in USA (Wu et al., 2021). The lower detection limit of infection cases in the present study demonstrated the feasibility and applicability of the developed method to establish the early warning system in Hong Kong.

3.6. Comparison of prevalence rates from the wastewater data and the clinical testing results

In the present study, SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the larger NWK showed significant correlations with the COVID-19 prevalence rates in that catchment area, but insignificant in the smaller ones, i.e. ST and SWH (Fig. S3). Thus, the data of NWK was used to calculate prevalence rates from the wastewater data (Pww) for comparison with the reported case number based on the clinical testing. Significant positive correlations were observed between the wastewater-derived prevalence (Pww) and the case number-derived prevalence, for both daily new cases (Pdaily) and weekly cumulative total cases (Pweekly) (Fig. 5 ). However, the Pww is much higher than Pdaily and Pweekly, with the slope of 32.671 and 2.783. Even though considering virus shedding from convalescent patients and lagged reported day(s) of new patients, there were still large discrepancies between the wastewater-derived prevalence rates and the case number-derived prevalence. These inconsistencies arise from multiple reasons, such as the uncertainty of virus shedding in stool samples (Wu et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020), variation of SARS-CoV-2 RNA recovery efficiency during the analytical process (Kantor et al., 2021), and underestimation of clinical confirmed cases for those asymptomatic or reluctant for testing patients. Therefore, wastewater data could be used to monitor the prevalence dynamic trend in parallel to the clinical datasets, but it should be cautious to infer the exact case number from the viral load in wastewater.

Fig. 5.

Comparisons of prevalence rates calculated from the wastewater data (Pww) and the clinical data using (a) prevalence of daily new cases (Pdaily) and (b) prevalence of total new cases and convalescent patients within 7 days of sampling date (Pweekly).

To maximize the utility of wastewater surveillance for capturing overall infection trends, additional researches are needed to integrate clinical and wastewater data. First, the wastewater-derived prevalence dynamic could be improved in accuracy and robustness by sampling more WWTPs dataset from diverse geographic regions to increase sample representativeness. Second, except for the back-estimation approach used in this study, other data-driven models should be applied to derive more accurate dynamic for the case prediction (Li et al., 2021). Third, the whole analytical process of SARS-CoV-2 RNA should be standardized for monitoring long-term trends by different batches of analyses.

4. Conclusions

-

•

In the present study, SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater samples were found to correlate with the infection dynamics through the 6-month sampling campaigns across three WWTPs in Hong Kong.

-

•

Supernatant concentrated by the two-step ultracentrifugation method was more robust and sensitive than pellet obtained by low-speed centrifugation directly. The selection of processing supernatant or pellet fractions need to consider the separation methods, sampling sites and virus concentration method.

-

•

Sampling frequency and the smoothing days are critical in catching the trendline, while normalization against PMMoV or flow rates did not improve the correlation.

-

•

The longitudinal trend of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater samples of a WWTP serving over 1 million people matched with the epidemiological scenarios of the city, demonstrating the sensitivity and feasibility of our method.

-

•

Wastewater dataset correlated with the overall clinical prevalence rates in general, but large inconsistency still exists and it is challenging to infer the exact case number from wastewater.

-

•

Long-term and regular wastewater surveillance in WWTPs is a cost-effective tool to provide the trend of the pandemic dynamic, and will help inform the authorities for timely public health actions and effective resources allocation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiawan Zheng: Methodology, Experiment, Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Shuxian Li: Methodology, Experiment. Yu Deng: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Xiaoqing Xu: Methodology, Experiment. Jiahui Ding: Experiment. Frankie T.K. Lau: Resources. Chung In Yau: Experiment. Leo L.M. Poon: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Hein Min Tun: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Tong Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Analysis, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Health and Medical Research Fund (HMRF) (COVID190209 and COVID1903015), the Food and Health Bureau, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China. We appreciated the help from Environmental Protection Department (EPD) and Drainage Services Department (DSD) of Hong Kong SAR Government for the wastewater sample collection and delivery. We also thank Vicky Fung for the technical support on lab facilities. Xiawan Zheng, Shuxian Li, Xiaoqing Xu, and Jiahui Ding would like to thank for The University of Hong Kong for the Postgraduate Studentship (PGS).

Editor: Warish Ahmed

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157121.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Ahmed W., Bivins A., Bertsch P.M., Bibby K., Gyawali P., Sherchan S.P., et al. Intraday variability of indicator and pathogenic viruses in 1-h and 24-h composite wastewater samples: implications for wastewater-based epidemiology. Environ. Res. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Tscharke B., Bertsch P.M., Bibby K., Bivins A., Choi P., et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA monitoring in wastewater as a potential early warning system for COVID-19 transmission in the community: a temporal case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;761 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamin M., Tsuji S., Hata A., Hara-Yamamura H., Honda R. Selection of surrogate viruses for process control in detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;823 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt W.Q., Schmitz B.W., Innes G.K., Prasek S.M., Pogreba Brown K.M., Stark E.R., et al. COVID-19 containment on a college campus via wastewater-based epidemiology, targeted clinical testing and an intervention. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;779:146408. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivins A., Kaya D., Bibby K., Simpson S.L., Bustin S.A., Shanks O.C., et al. Variability in RT-qPCR assay parameters indicates unreliable SARS-CoV-2 RNA quantification for wastewater surveillance. Water Res. 2021;203 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . 2020. 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) real-time RT-PCR primers and probes. [Google Scholar]

- Chik A.H.S., Glier M.B., Servos M., Mangat C.S., Pang X.L., Qiu Y., et al. Comparison of approaches to quantify SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater using RT-qPCR: results and implications from a collaborative inter-laboratory study in Canada. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2021;107:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2021.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin A.W.H., Chu J.T.S., Perera M.R.A., Hui K.P.Y., Yen H.-L., Chan M.C.W., et al. 2020. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K., et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aoust P.M., Mercier E., Montpetit D., Jia J.J., Alexandrov I., Neault N., et al. Quantitative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from wastewater solids in communities with low COVID-19 incidence and prevalence. Water Res. 2021;188 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Xu X., Zheng X., Ding J., Li S., Chui H.K., et al. Use of sewage surveillance for COVID-19 to guide public health response: a case study in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;821 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Zheng X., Xu X., Chui H.K., Lai W.K., Li S., et al. Use of sewage surveillance for COVID-19: a large-scale evidence-based program in Hong Kong. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022;130:57008. doi: 10.1289/EHP9966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvallet C., Wu F., KA McElroy, Imakaev M., Endo N., Xiao A., et al. 2021. Nationwide trends in COVID-19 cases and SARS-CoV-2 wastewater concentrations in the United States. medRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Union E . 2021. Commission Recommendations (EU) on a Common Approach to Establish a Systematic Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 And Its Variant in Wastewater in the EU. [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Roguet A., McClary-Gutierrez J.S., Newton R.J., Kloczko N., Meiman J.G., et al. Evaluation of sampling, analysis, and normalization methods for SARS-CoV-2 concentrations in wastewater to assess COVID-19 burdens in Wisconsin communities. ACS ES&T Water. 2021;1:1955–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Cassi X., Scheidegger A., Banziger C., Cariti F., Tunas Corzon A., Ganesanandamoorthy P., et al. Wastewater monitoring outperforms case numbers as a tool to track COVID-19 incidence dynamics when test positivity rates are high. Water Res. 2021;200 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald S.F., Rossi G., Low A.S., McAteer S.P., O’Keefe B., Findlay D., et al. Site specific relationships between COVID-19 cases and SARS-CoV-2 viral load in wastewater treatment plant influent. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55(22):15276–15286. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c05029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawlik B., Tavazzi S., Mariani G., Skejo H., Sponar M., Higgins T., Medema G., Wintgens T. Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance employing Sewage - Towards a Sentinel System, EUR 30684 EN. JRC125065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R., Curtis K., Bivins A., Bibby K., Weir M.H., Yetka K., et al. COVID-19 surveillance in Southeastern Virginia using wastewater-based epidemiology. Water Res. 2020;186 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GovHK TGotHKSAR. 2021. Government announces list of third cycle designated quarantine hotels. [Google Scholar]

- GovHK TGotHKSAR. 2021. Government begins to relax social distancing measures in gradual and orderly manner. [Google Scholar]

- GovHK TGotHKSAR. 2021. Government makes "restriction-testing declaration" and issues compulsory testing notice in respect of specified "restricted area" in Jordan. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K.E., Loeb S.K., Wolfe M.K., Catoe D., Sinnott-Armstrong N., Kim S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater settled solids is associated with COVID-19 cases in a large urban sewershed. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55:488–498. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c06191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald H.D., Kennedy L.C., Hinkle A., Whitney O.N., Fan V.B., Crits-Christoph A., et al. Tools for interpretation of wastewater SARS-CoV-2 temporal and spatial trends demonstrated with data collected in the San Francisco Bay Area. Water Res. X. 2021;12:100111. doi: 10.1016/j.wroa.2021.100111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillary L.S., Farkas K., Maher K.H., Lucaci A., Thorpe J., Distaso M.A., et al. Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in municipal wastewater to evaluate the success of lockdown measures for controlling COVID-19 in the UK. Water Res. 2021;200 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokajarvi A.M., Rytkonen A., Tiwari A., Kauppinen A., Oikarinen S., Lehto K.M., et al. The detection and stability of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers in wastewater influent in Helsinki,Finland. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;770 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman J.S., Scire J., Caduff L., Fernandez-Cassi X., Ganesanandamoorthy P., Kull A., et al. 2021. Wastewater-based estimation of the effective reproductive number of SARS-CoV-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakariya M., Ahmed F., Islam M.A., Ahmed T., Marzan A.A., Hossain M., et al. 2021. Wastewater based surveillance system to detect SARS-CoV-2 genetic material for countries with on-site sanitation facilities: an experience from Bangladesh. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor R.S., Nelson K.L., Greenwald H.D., Kennedy L.C. Challenges in measuring the recovery of SARS-CoV-2 from wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55:3514–3519. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c08210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan S., Ronquillo N., Belda-Ferre P., Alvarado D., Javidi T., Longhurst C.A., et al. High-throughput wastewater SARS-CoV-2 detection enables forecasting of community infection dynamics in San Diego County. mSystems. 2021;6 doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00045-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby A.E., Walters M.S., Jennings W.C., Fugitt R., LaCross N., Mattioli M., et al. Using wastewater surveillance data to support the COVID-19 response - United States, 2020–2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1242–1244. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7036a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Joshi M., Shah A.V., Srivastava V., Dave S. Wastewater surveillance-based city zonation for effective COVID-19 pandemic preparedness powered by early warning: a perspectives of temporal variations in SARS-CoV-2-RNA in Ahmedabad,India. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;792 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Kulandaivelu J., Zhang S., Shi J., Sivakumar M., Mueller J., et al. Data-driven estimation of COVID-19 community prevalence through wastewater-based epidemiology. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;789 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in the Netherlands. Environ.Sci.Technol.Lett. 2020;7:511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer T.R., Salit M. Testing at scale during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021;22:415–426. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00360-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton C.C., Roman F.A., AGF Alvarado, Tariqi A.Q., Deeming M.A., Bibby K., et al. 2021. Show Us the Data: Global COVID-19 Wastewater Monitoring Efforts, Equity, And Gaps. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peccia J., Zulli A., Brackney D.E., Grubaugh N.D., Kaplan E.H., Casanovas-Massana A., et al. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:1164–1167. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0684-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn R., Ward B.J., Strande L., Maurer M. Review of synthetic human faeces and faecal sludge for sanitation and wastewater research. Water Res. 2018;132:222–240. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusinol M., Zammit I., Itarte M., Fores E., Martinez-Puchol S., Girones R., et al. Monitoring waves of the COVID-19 pandemic: inferences from WWTPs of different sizes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;787 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherchan S.P., Shahin S., Ward L.M., Tandukar S., Aw T.G., Schmitz B., et al. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater in North America: a study in Louisiana, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandukar S., Sthapit N., Thakali O., Malla B., Sherchan S.P., Shakya B.M., et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater, river water, and hospital wastewater of Nepal. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;824 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe M.K., Archana A., Catoe D., Coffman M.M., Dorevich S., Graham K.E., et al. Scaling of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in settled solids from multiple wastewater treatment plants to compare incidence rates of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 in their sewersheds. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021;8:398–404. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Muller M.A., et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J.C.C., Tan J., Lim Y.X., Arivalan S., Hapuarachchi H.C., Mailepessov D., et al. Non-intrusive wastewater surveillance for monitoring of a residential building for COVID-19 cases. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;786 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Xiao A., Jian B., Moniz K., Endo N., Armas F., et al. Wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 across 40 U.S states from February to June 2020. Water Res. 2021;202:117400. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhang J., Xiao A., Gu X., Lee W.L., Armas F., et al. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater are higher than expected from clinically confirmed cases. mSystems. 2020;5 doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00614-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtzer S., Marechal V., Mouchel J.M., Maday Y., Teyssou R., Richard E., et al. Evaluation of lockdown effect on SARS-CoV-2 dynamics through viral genome quantification in waste water, Greater Paris, France, 5 March to 23 April 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.50.2000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Zheng X., Li S., Lam N.S., Wang Y., Chu D.K.W., et al. The first case study of wastewater-based epidemiology of COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;790 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Deng Y., Ding J., Zheng X., Li S., Liu L., et al. Real-time allelic assays of SARS-CoV-2 variants to enhance sewage surveillance. Water Res. 2022;220 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Deng Y., Zheng X., Li S., Ding J., Yang Y., et al. Evaluation of RT-qPCR primer-probe sets to inform public health interventions based on COVID-19 sewage tests. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c00974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Ellenberg R.M., Graham K.E., Wigginton K.R. Survivability, partitioning, and recovery of enveloped viruses in untreated municipal wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:5077–5085. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S., Fan J., Yu F., Feng B., Lou B., Zou Q., et al. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January-March 2020: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Deng Y., Xu X., Li S., Zhang Y., Ding J., et al. Comparison of virus concentration methods and RNA extraction methods for SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;824:153687. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material