Abstract

Objectives

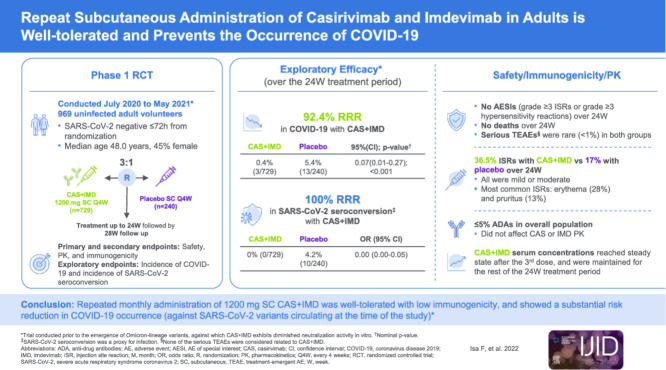

A phase 1, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and exploratory efficacy of repeat monthly doses of subcutaneous (SC) casirivimab and imdevimab (CAS+IMD) in uninfected adult volunteers.

Methods

Participants were randomized (3:1) to SC CAS+IMD 1200 mg or placebo every 4 weeks for up to six doses. Primary and secondary end points evaluated safety, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity. Exploratory efficacy was evaluated by the incidence of COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion.

Results

In total, 969 participants received CAS+IMD. Repeat monthly dosing of SC CAS+IMD led to a 92.4% relative risk reduction in clinically defined COVID-19 compared with placebo (3/729 [0.4%] vs 13/240 [5.4%]; odds ratio 0.07 [95% CI 0.01-0.27]), and a 100% reduction in laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 (0/729 vs 10/240 [4.2%]; odds ratio 0.00). Development of anti-drug antibodies occurred in a small proportion of participants (<5%). No grade ≥3 injection-site reactions (ISRs) or hypersensitivity reactions were reported. Slightly more participants reported treatment-emergent adverse events with CAS+IMD (54.9%) than with placebo (48.3%), a finding that was due to grade 1-2 ISRs. Serious adverse events were rare. No deaths were reported in the 6-month treatment period.

Conclusion

Repeat monthly administration of 1200 mg SC CAS+IMD was well-tolerated, demonstrated low immunogenicity, and showed a substantial risk reduction in COVID-19 occurrence.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Monoclonal antibody, Casirivimab, Imdevimab

Graphical abstract

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 is the causal agent of COVID-19 (Huang et al., 2020; Ludwig and Zarbock, 2020; Wang et al., 2020), which emerged in December 2019 and was declared a pandemic in March 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2019). As the SARS-CoV-2 virus continues to evolve, different approaches for COVID-19 treatment and prophylaxis are urgently needed, especially for individuals who have not mounted or are not expected to mount an adequate immune response to complete COVID-19 vaccination.

Casirivimab and imdevimab (CAS+IMD) is a combination of two distinct neutralizing monoclonal antibodies that simultaneously bind nonoverlapping epitopes of the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, thereby preventing the virus from infecting host cells (Baum et al., 2020; Baum and Kyratsous, 2021; Hansen et al., 2020). Previous trials with CAS+IMD have shown clinical benefit in the treatment of COVID-19, reducing the likelihood of hospitalization and death by over 70% in high-risk outpatients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Weinreich et al., 2021), and reducing mortality in hospitalized patients who are seronegative by 21% (RECOVERY Collaborative Group, 2022). In addition, a single dose of CAS+IMD reduced asymptomatic infection and COVID-19 (symptomatic infection) in close contacts of infected individuals (O'Brien et al., 2021). On the basis of these studies, CAS+IMD was authorized for treatment and post-exposure prophylaxis for COVID-19 in certain settings in the US under the trade name REGEN-COV® (Food and Drug Administration, 2020; Food and Drug Administration, 2021), and for treatment and prevention of COVID-19 in other jurisdictions under the trade name RonapreveTM (GOV.UK, 2021). With the high prevalence of the Omicron variant lineages, and because data show that CAS+IMD is unlikely to be active against them, CAS+IMD is not currently authorized for use in any US states, territories, or jurisdictions (Food and Drug Administration, 2022). This study evaluated the safety, tolerability, and exploratory efficacy of monthly dosing of subcutaneous (SC) CAS+IMD in uninfected individuals.

Methods

Study design

This phase 1, double-blind, placebo-controlled study was conducted at seven sites in the US (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT04519437). The study included a screening/baseline period (up to 7 days), a treatment period (up to 24 weeks), and a follow-up period (28 weeks) (Supplementary Figure 1); the total study duration was 1 year. Participants underwent an end-of-treatment-period visit 1 month after their final dose of study drug. They then entered the 28-week follow-up period leading to an end-of-study visit. As of the data cutoff date of May 21, 2021, all eligible participants had completed the end-of-treatment visit after receipt of up to six doses of study drug; follow-up was ongoing, with not all participants having completed the entire study. The rationale for 1200 mg SC dose selection and the methods for dose administration are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Participants

Eligible participants were uninfected adult volunteers, aged 18-90 years, who were healthy or had chronic but stable medical conditions and had no signs/symptoms suggestive of COVID-19. All had confirmed negative test results for SARS-CoV-2 by central lab reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of nasopharyngeal swab ≤72 hours before randomization. While in the treatment period, participants who met any of the following criteria were discontinued from study drug and were moved into the follow-up period: tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, developed symptomatic COVID-19, experienced an adverse event (AE) that led to study drug discontinuation, received a dose of an investigational COVID-19 vaccine, or were unblinded per protocol to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as diagnostic criteria for COVID-19, are presented in the Supplementary Appendix.

COVID-19 vaccination during the study

Participants who elected to receive COVID-19 vaccination were discontinued from study drug and entered follow-up. Handling of COVID-19 vaccination during the study is described in the Supplementary Appendix.

Outcome measures

The primary end points were 1) the incidence of AEs of special interest (AESIs), defined as grade ≥3 injection-site reactions (ISRs) or hypersensitivity reactions, occurring within 4 days of administration of CAS+IMD or placebo and 2) the concentrations of CAS+IMD in serum over time. All AEs were graded for severity using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, v5.0. Investigators assessed AEs to determine seriousness, relatedness to investigational product, and fulfilment of AESI criteria.

Secondary end points included the proportion of participants with treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) and immunogenicity (measured by anti-drug antibodies [ADAs]) to CAS+IMD.

Exploratory efficacy end points assessed the incidence and severity of symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection (i.e., COVID-19) during the treatment and follow-up periods and the proportion of baseline anti-SARS-CoV-2 seronegative participants who converted to seropositive for SARS-CoV-2 anti-nucleocapsid immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibodies post-baseline; seroconversion from negative to positive for SARS-CoV-2 anti-nucleocapsid IgG antibodies was considered indicative of an incident SARS-CoV-2 infection. Diagnosis of COVID-19 and assessment of SARS-CoV-2 serostatus are described in the Supplementary Appendix. In the event of suspected COVID-19, symptoms were evaluated by the investigator and the investigator was responsible for confirming infection. Participants were medically managed according to local standard of care.

Statistical analysis

The study aimed to enroll approximately 940 participants (705 and 235 participants in the CAS+IMD and placebo groups, respectively) to ensure sufficient safety data to support multiple-dose administration of CAS+IMD.

Treatment compliance/administration, the exploratory efficacy end points, and all clinical safety variables were analyzed in the safety analysis set, which comprised all randomized participants who received any study drug. Participants who received ≥1 dose of CAS+IMD were classified in the CAS+IMD group. The pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis set included all participants who received any study drug and had ≥1 non-missing post-baseline result.

Summary statistics were provided for safety analyses, exploratory efficacy analyses (with nominal P-values) and PK and immunogenicity variables. Handling of missing data and PK analysis methods are described in the Supplementary Appendix.

Study oversight

The protocol was developed by the sponsor (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). Data were collected by the study investigators and analyzed by the sponsor. The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. The local institutional review board or ethics committee at each study site oversaw trial conduct and documentation. All patients provided written informed consent before participating in the trial.

Results

Demographics and baseline characteristics

As of the data cutoff date of May 21, 2021, 974 participants were randomized into the study, of whom 969 were treated (Supplementary Figure 2; Supplementary Table 1). The safety analysis set (the population used for all safety and exploratory efficacy analyses) included 240 participants in the placebo group and 729 participants in the CAS+IMD group.

Baseline characteristics were balanced between the CAS+IMD and placebo groups. The overall median age was 48 years, 44.9% of participants were female, 10% of participants identified as African American, and 23.4% of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino (Table 1 ). There were six participants (0.6%) who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in a centralized RT-PCR test at baseline who had previously tested negative in screening with a local test. These participants received one dose of study drug before the availability of the RT-PCR test result from the central lab; they were discontinued from additional doses of study drug and excluded from efficacy analyses but continued to be followed for safety. Participants were included in the study regardless of SARS-CoV-2 antibody serostatus. At baseline, 825 (85.1%) participants were seronegative for SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike and anti-nucleocapsid antibodies, 101 (10.4%) were seropositive for anti-spike and/or anti-nucleocapsid antibodies, and 43 (4.4%) were of borderline or unknown serostatus (Table 1). Medical history was comparable between the CAS+IMD and placebo groups, with 20% of participants reporting ≥1 medical condition considered high-risk for progression to severe COVID-19 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2021a; Rosenthal et al., 2020; Williamson et al., 2020); the most common of these were hypertension and asthma (Table 1; Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics.

| Placebo n = 240 | CAS+IMD 1200 mg SC Q4W n = 729 | Total n = 969 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 48.0 (36.0, 59.0) | 48.0 (36.0, 58.0) | 48.0 (36.0, 58.0) |

| ≥50, n (%) | 112 (46.3) | 340 (46.8) | 452 (46.6) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 36 (15.0) | 90 (12.3) | 126 (13) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 109 (45.0) | 326 (44.9) | 435 (44.9) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 55 (22.9) | 172 (23.6) | 227 (23.4) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 207 (86.3) | 632 (86.7) | 839 (86.6) |

| Black or African American | 24 (10.0) | 73 (10.0) | 97 (10.0) |

| Asian | 5 (2.1) | 12 (1.6) | 17 (1.8) |

| Other | 4 (1.6) | 12 (1.6) | 16 (1.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 29.3 (6.8) | 29.4 (6.3) | 29.4 (6.4) |

| Baseline SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR result, n (%) | |||

| Negative | 238 (99.2) | 720 (98.8) | 958 (98.9) |

| Positive | 0 | 6 (0.8) | 6 (0.6) |

| Undetermined/missing | 2 (0.8) | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) |

| Baseline anti-SARS-CoV-2 serology result, n (%)a | |||

| Seronegative | 208 (86.7) | 617 (84.6) | 825 (85.1) |

| Seropositive | 24 (10.0) | 77 (10.6) | 101 (10.4) |

| Borderline | 6 (2.5) | 32 (4.4) | 38 (3.9) |

| Undetermined/missingb | 2 (0.8) | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||

| Participants with at least one medical history conditionc | 204 (85.0) | 615 (84.4) | 819 (84.5) |

| Participants with at least one medical history condition identified as high-risk for severe SARS-CoV-2 infectionc,d | 42 (17.5) | 152 (20.9) | 194 (20.0) |

BMI, body mass index; Q, quartile; Q4W, every 4 weeks; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SC, subcutaneous; SD, standard deviation; SMQs, Standardised Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities queries.

Baseline serology was defined as “seropositive” if positive for any of the three tests used (anti-S1 domain of spike protein IgG and IgA antibodies [EuroImmun] and anti-nucleocapsid IgG antibodies [Abbott]).

Participants with undetermined/missing baseline RT-PCR results were included in the analyses.

Participants may have had more than one.

Identified criteria are defined by the SMQ terms (narrow scope only) fitting Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for high-risk for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Exploratory efficacy

Incidence of COVID-19

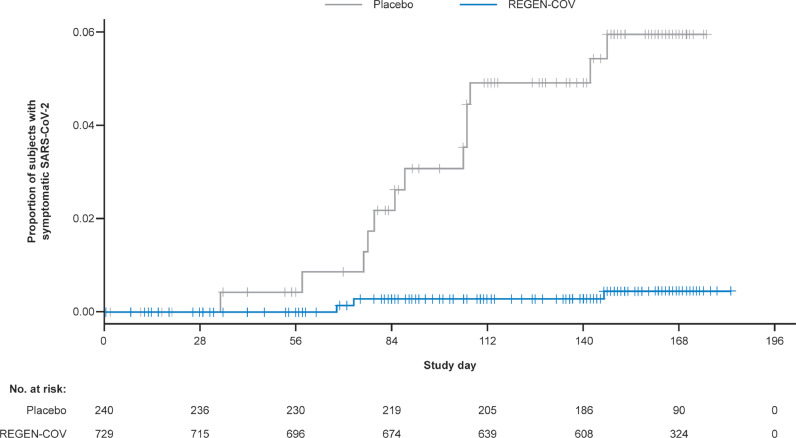

COVID-19 (symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection) diagnosis was made by the investigator based on clinical assessment. In a predefined exploratory analysis of efficacy, monthly CAS+IMD reduced the risk of COVID-19 infection over the 6-month dosing interval. There was a 92.4% relative risk reduction (RRR) for COVID-19 infections with CAS+IMD compared with placebo during the treatment period (3/729 [0.4%] vs 13/240 [5.4%]; odds ratio 0.07 [95% confidence interval {CI} 0.01-0.27]; nominal P-value <0.001) (Figure 1 ; Supplementary Table 3). Although not all study participants had completed the follow-up period at the time of data cutoff, during the entire study period there was a 93.0% RRR for COVID-19 infections with CAS+IMD compared with placebo (3/729 [0.4%] vs 14/240 [5.8%]) (Supplementary Table 3). These COVID-19 cases were evenly distributed throughout the study (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection during the treatment period. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The proportion of participants with the reported adverse event of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with the number of participants at risk for infection in the CAS+IMD group and placebo group is shown by study day. Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) determination was made by the investigator on the basis of clinical assessment.

Two additional participants who previously received placebo developed COVID-19 infection 2 days and 5 days after COVID-19 vaccination (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4); these events were excluded from the efficacy analysis. In total, including all cases of suspected COVID-19 regardless of COVID-19 vaccination status, there were 3/729 CAS+IMD (0.4%) and 16/240 placebo (6.7%) recipients who developed COVID-19, corresponding to an approximately 94% RRR, during the study (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

In the CAS+IMD group, each of the three (0.4%) participants who reported COVID-19 as an AE was seronegative for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies at baseline and at the end-of-treatment-period visit (Supplementary Table 4). Two of the three participants had negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test results, and one did not have RT-PCR data analyzed. Thus, although counted as infected, none of these three patients had laboratory confirmation of infection with SARS-CoV-2. Among these three CAS+IMD recipients, symptom duration was 11, 16, and 18 days, and symptoms were mostly mild (Supplementary Table 4). In contrast, for the 16 (6.7%) participants who were reported to have developed COVID-19 in the placebo group, 11 had either seroconversion for SARS-CoV-2 anti-nucleocapsid IgG antibodies or a SARS- CoV-2 infection documented by RT-PCR or antigen test. Among placebo recipients, symptom duration ranged from 5 to 30 days and symptoms were mostly mild, though a few were reported as moderate, in severity. In a subgroup analysis excluding the one participant with a positive antigen test, 10/240 (4.2%) in the placebo group and 0/729 in the CAS+IMD group had laboratory-confirmed infection as defined by RT-PCR positivity or seroconversion for SARS-CoV-2 anti-nucleocapsid IgG antibodies during the treatment period, corresponding to a 100% RRR for CAS+IMD versus placebo (odds ratio 0.00) (Supplementary Table 5). A list of all participants who experienced the AE of COVID-19, including serologic and/or PCR confirmation, is provided in Supplementary Table 4.

SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion

Conversion from SARS-CoV-2 anti-nucleocapsid seronegative to seropositive was used to assess the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the study. Of participants who were seronegative for anti-spike and anti-nucleocapsid protein (anti-spike IgG, anti-spike IgA, or anti-nucleocapsid IgG) at baseline, 0/617 (0%) of CAS+IMD recipients were seropositive for anti-nucleocapsid protein (anti-nucleocapsid IgG), compared with 20/208 (9.6%) of placebo recipients at the end-of-treatment-period visit, with a 100% risk reduction for anti-SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion (odds ratio 0.00 [95% CI 0.00-0.05]) (Supplementary Table 6). Of the 20 placebo recipients who seroconverted, eight reported symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection during the treatment period (Supplementary Table 6).

Safety and tolerability

Incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events

Over the 6-month treatment period, there were no AESIs (defined as grade ≥3 ISRs or grade ≥3 hypersensitivity reactions) or deaths reported among any study participants. Serious TEAEs were rare and occurred at similar rates in the CAS+IMD and placebo groups (5/729 [0.7%] vs 2/240 [0.8%]) (Supplementary Table 7). No serious TEAEs were determined to be related to study drug. A greater percentage of participants withdrew from the study because of an AE in the placebo group (12/240 [5.0%]) than in the CAS+IMD group (13/729 [1.8%]) (Supplementary Table 8). The most common AE leading to study drug withdrawal was COVID-19 (2/729 [0.3%] in CAS+IMD and 11/240 [4.6%] in placebo). A slightly higher percentage of participants reported TEAEs in the CAS+IMD group (400/729 [54.9%]) than in the placebo group (116/240 [48.3%]), a finding that is attributable to the higher rate of ISRs with CAS+IMD (Table 2 ). Aside from ISRs, the only TEAEs occurring at ≥5% were headache (8.0% in CAS+IMD vs 7.0% in placebo) and COVID-19 (0.4% in CAS+IMD vs 5.4% in placebo) (Supplementary Table 9).

Table 2.

Overview of TEAEs in the treatment period.

| Placebo n = 240 | CAS+IMD 1200 mg SC Q4W n = 729 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of TEAEs | 326 | 2107 |

| Number of grade ≥3 TEAEs | 3 | 10 |

| Number of serious TEAEs | 5 | 8 |

| Number of AESIsa | 0 | 0 |

| Number of TEAEs resulting in study drug being withdrawn | 13 | 15 |

| Number of TEAEs resulting in death | 0 | 0 |

| Participants with at least one TEAE, n (%)b | 116 (48.3) | 400 (54.9) |

| Participants with at least one ISRb | 40 (16.7) | 266 (36.5) |

| Grade 1 | 38 (15.8) | 211 (28.9) |

| Grade 2 | 2 (0.8) | 55 (7.5) |

| Grade ≥3 | 0 | 0 |

| Participants with at least one grade ≥3 TEAEb,c, n (%) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (0.5) |

| Participants with at least one serious TEAE, n (%)b | 2 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) |

| Participants with at least one TEAE resulting in study drug being withdrawn, n (%)b | 12 (5.0) | 13 (1.8) |

| Participants with any TEAE resulting in death, n (%) | 0 | 0 |

AESI, adverse event of special interest; ISR, injection-site reaction; Q4W, every 4 weeks; SC, subcutaneous; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

AESIs were defined as grade ≥3 injection-site or hypersensitivity reactions.

Participants may have had more than one.

No grade ≥3 TEAEs were determined to be related to study drug.

Injection-site reactions

In this multi-dose study, ISRs were experienced by 266/729 (36.5%) CAS+IMD recipients and 40/240 (16.7%) placebo recipients during the 6-month treatment period (Table 2). All ISRs for CAS+IMD and placebo were mild (grade 1, 28.9% and 15.8%, respectively) or moderate (grade 2, 7.5% and 0.8%, respectively), (Table 2). The majority of ISRs (>60%) resolved within 4 days of dosing (Supplementary Table 10), either spontaneously or with the use of over-the-counter medications. The most prevalent ISRs observed with CAS+IMD were erythema (27.6%) and pruritus (13.0%) (Supplementary Table 10).

Across all seven study sites combined, the rate of CAS+IMD ISRs was stable from doses one through four (∼13% per dose) and was higher with doses five and six (∼19% per dose) (Supplementary Figure 4a). However, an imbalance in ISR rates was observed between study sites, with the overall incidence being driven by two outlier sites (Supplementary Figure 4b; Supplementary Table 11). Across the other five sites, the rate of ISRs was stable across all six doses of CAS+IMD (∼6% per dose) (Supplementary Figure 4c).

Adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination

During this study, 354/969 (36.5%) of all participants (including 256/729 [35.1%] CAS+IMD and 98/240 [40.8%] placebo) received COVID-19 vaccination. Per study protocol, these participants were discontinued from further doses of study drug and continued to be followed for safety (Supplementary Table 12). Participants who received COVID-19 vaccination had a mean of 66.1 (from −20 to 194) days between last dose of study drug and receipt of vaccination, despite Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021b) recommending a 90-day delay between passive antibody therapy and COVID-19 vaccination (Supplementary Table 12). AEs after COVID-19 vaccination occurred in 39 (15.2%) participants who had previously received CAS+IMD and 18 (18.4%) participants who had previously received placebo (Supplementary Table 13). AEs after COVID-19 vaccination were all grade 1-2, except for a single grade 3 event in a participant previously dosed with CAS+IMD; this grade 3 event of brain mass, frontal lobe was assessed as not related to study drug (Supplementary Table 13).

Pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity

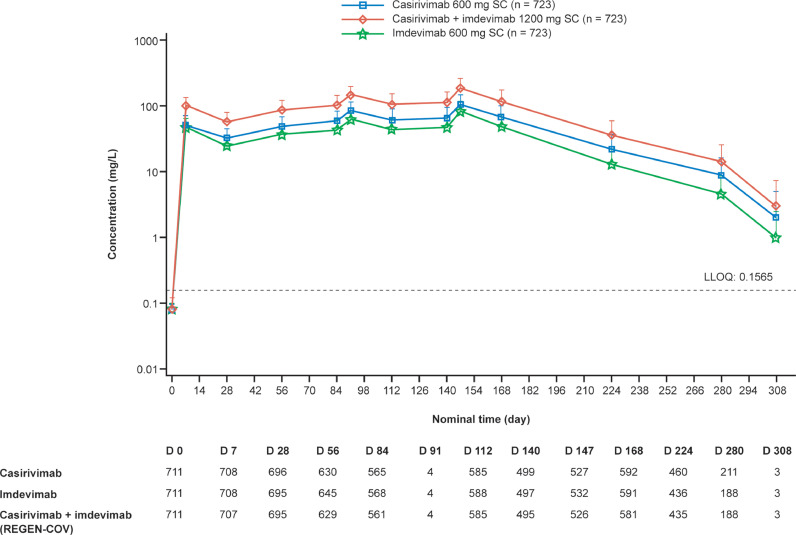

PK analysis showed that concentrations of casirivimab and imdevimab in serum reached steady state after the third dose of CAS+IMD and were maintained throughout the 6-month treatment period (Figure 2 ). Concentrations 28 days after the first dose of CAS+IMD were 32.7 mg/l for casirivimab and 24.8 mg/l for imdevimab, with accumulation ratios (ratio of concentrations 28 days after the sixth and the first doses) of 2.08- and 1.98-fold, respectively (Figure 2). Notably, in the three CAS+IMD recipients who reported COVID-19 symptoms, serum concentrations of casirivimab and imdevimab were comparable to those in participants without any reported COVID-19 symptoms (Supplementary Table 14).

Figure 2.

Concentrations of casirivimab, imdevimab, and casirivimab+imdevimab in serum over time. D, day; LLOQ, lower limit of quantification; SC, subcutaneous. Serum concentration of casirivimab, imdevimab, and casirivimab+imdevimab (CAS+IMD) in serum are depicted by study day. Sample collection visits on day 91 and day 208 were included in the original version of the protocol but were removed in protocol amendment 3.

We also examined whether repeat dosing would be associated with the formation of ADAs against either casirivimab or imdevimab, and whether these ADAs would impact circulating levels of drug. Casirivimab and imdevimab both showed low treatment-emergent immunogenicity, measured as ADAs in ≤5% of the population (1.1% for anti-casirivimab and 5% for anti-imdevimab). Approximately 4% of participants had pre-existing ADAs against casirivimab (3.1%) and imdevimab (3.9%) (Table 3 ); safety analyses and incidence of COVID-19 in participants with pre-existing ADAs are presented in Supplementary Table 4 (see footnote) and Supplementary Table 15. ADAs did not appear to impact circulating levels of study drug, as concentrations of casirivimab and imdevimab were comparable in participants with positive and negative ADA results (Supplementary Figure 5).

Table 3.

Casirivimab and imdevimab immunogenicity by anti-drug antibody status.

| ADA Status and Category | Placebo n (%) | CAS+IMD 1200 mg SC Q4W n (%) | Overall n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casirivimab immunogenicity | |||

| ADA analysis set | 237 (100) | 717 (100) | 954 (100) |

| Negative | 228 (96.2) | 687 (95.8) | 915 (95.9) |

| Pre-existing immunoreactivity | 8 (3.4) | 22 (3.1) | 30 (3.1) |

| Treatment-boosted response | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-emergent response | 1 (0.4) | 8 (1.1) | 9 (0.9) |

| Imdevimab immunogenicity | |||

| ADA analysis set | 237 (100) | 717 (100) | 954 (100) |

| Negative | 221 (93.2) | 653 (91.1) | 874 (91.6) |

| Pre-existing immunoreactivity | 9 (3.8) | 28 (3.9) | 37 (3.9) |

| Treatment-boosted response | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-emergent response | 7 (3.0) | 36 (5.0) | 43 (4.5) |

ADA, anti-drug antibody; Q4W, every 4 weeks; SC, subcutaneous.

n = number of participants contributing to each category.

Discussion

Recent data have shown that some individuals are not able/expected to mount an adequate immune response to COVID-19 vaccination (e.g., individuals with immunocompromising conditions and particularly those with B-cell deficiencies, including those taking immunosuppressive medications), leaving them unprotected and at increased risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and progression to severe COVID-19 (Bird et al., 2021; Lontok, 2021; Munro, 2021). The estimated number of such immunocompromised individuals is as high as 3% of the US population (Harpaz et al., 2016; Wallace et al., 2021). This highlights an unmet medical need for a significant subset of the population to have access to both COVID-19 treatment and prophylaxis, particularly in light of the ongoing resurgence in COVID-19 cases with the emergence of new variants.

This is the first study to investigate monthly SC administration of CAS+IMD. Results from this study show that CAS+IMD is well-tolerated and extend the findings of the household contact prevention study (O'Brien et al., 2021) by showing that monthly CAS+IMD prevents COVID-19 over a 6-month period. In a predefined exploratory efficacy analysis, CAS+IMD resulted in a 92.4% RRR for suspected COVID-19 versus placebo and a 100% RRR for laboratory-confirmed COVID-19. Although an assessment of efficacy was not the primary purpose of the study, the RRR for the development of COVID-19 seen in participants who received CAS+IMD is striking and is similar to the risk reduction seen in the vaccine trials (Baden et al., 2021; Polack et al., 2020; Tenforde et al., 2021; Voysey et al., 2021).

Results of this study also demonstrate a significant reduction in anti-nucleocapsid IgG seroconversion during the 6-month course of therapy among participants who received CAS+IMD. The production of SARS-CoV-2 anti-nucleocapsid IgG antibodies, as assessed by seroconversion from a seronegative status at baseline to a seropositive status, was considered a proxy for SARS-CoV-2 infection. There was a 9.6% seroconversion rate among placebo recipients and an absence of seroconversion (0%) among those who received CAS+IMD, suggesting that CAS+IMD is also effective in preventing asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection when given as pre-exposure prophylaxis for COVID-19. This finding is particularly impactful for immunocompromised individuals and in the context of long-term care facilities, such as nursing homes, where protection against asymptomatic infection could reduce viral transmission and potentially decrease overall morbidity and mortality in these vulnerable populations (Avanzato et al., 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021c; Kuritzkes, 2021).

Multiple-dose administration of CAS+IMD was well-tolerated. Compared with placebo, CAS+IMD was associated with a slightly higher frequency of ISRs. The overall rate of ISRs with CAS+IMD was ∼13% per dose, and 36.5% across all six doses combined. However, there was significant variability in the ISR rate between sites, with two outlier sites driving the incidence. A previous phase 3 study assessing the efficacy of CAS+IMD 1200 mg for post-exposure prophylaxis has shown an ISR rate of 4% after a single SC dose (O'Brien et al., 2021). This is consistent with the reported ISR rate observed at five of the seven sites in this study (∼6% per dose); however, two sites exhibited disproportionately higher ISR rates of 19-34% and 17-54% per dose, respectively. All ISRs were mild or moderate in severity (grade 1-2) and the incidence and severity of ISRs did not substantially increase with repeat dosing. There were no grade ≥3 hypersensitivity reactions in this study, and repeat dosing of CAS+IMD showed low incidence of treatment-emergent immunogenicity. Concentrations of each component of CAS+IMD, casirimivab and imedivimab, were maintained within the projected therapeutic range for viral neutralization throughout the dosing interval.

A potential limitation of this study was that regular RT-PCR testing was not performed in all participants who presented with a clinical syndrome compatible with COVID-19. However, when only laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection is considered, CAS+IMD showed a 100% RRR for the development of COVID-19. The discrepancy could imply that these participants had illnesses that were not due to SARS-CoV-2, or that sample collection time was not close enough to time of symptom onset. Another limitation of the study is that non-pharmaceutical interventions (e.g., personal protective equipment, social distancing) for the prevention of COVID-19 and their impacts on transmission dynamics could not be factored into the efficacy analysis.

In addition to incidence of infection, it is also important to consider severity of COVID-19 in those infected. While it was not possible to evaluate whether CAS+IMD provides protection against severe disease when compared with placebo in this study because of the small number of COVID-19 cases, previous reports have demonstrated that CAS+IMD reduces the duration of symptoms (O'Brien et al., 2021; O'Brien et al., 2022) and the likelihood of hospitalization and death (Weinreich et al., 2021) in SARS-CoV-2infected outpatients.

This study was conducted before the emergence of several SARS-CoV-2 variants. Although extensive nonclinical testing has demonstrated that CAS+IMD retains its neutralization capacity against nearly all clinically relevant viral variants tested, including Beta, Gamma, Epsilon, and Delta variants (Baum et al., 2020; Copin et al., 2021), CAS+IMD is not expected to retain activity against the several Omicron variant lineages (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2021; data on file). Antibodies that retain activity against Omicron are currently in development and could be similarly utilized.

Although CAS+IMD should not be deemed an appropriate substitute for vaccination in immunocompetent individuals, its efficacy and safety profile demonstrated in this study strongly support that CAS+IMD could be used for COVID-19 prophylaxis in individuals not expected to mount a sufficient immune response to vaccination, when circulating variants are susceptible to CAS+IMD.

Funding

This work was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Author contributions

FI, EF-N, JM, WZ, KCT, SG, AM, AD, JDH, YK, BK, YS, GPG, LL, NB, GDY, DMW, GAH contributed to study concept and design. FI, EF-N, JM, WZ, SR, DA, MO, CB, SF, LF, IH, SB, MPO'B, ATH, JDH were involved in data collection. ATH, JDH provided administrative, technical or material support. WZ, NS, BJM provided statistical analysis. FI, EF-N, JM, WZ, KCT, SG, AM, AD, GPG, NB, GDY, DMW, GAH provided analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors provided critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, and approval to submit.

Data availability

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, and statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities (e.g., Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, etc.), if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant reidentification. Requests should be submitted to https://vivli.org/. ClinicalTrials.gov National Clinical Trial number is NCT04519437.

Declarations of competing interest

FI, MPO, KCT, SG, JDH, and GAH are Regeneron employees/stockholders and have a patent pending, which has been licensed and receiving royalties, with Regeneron. EF-N, JM, WZ, LF, NS, BJM, SB, AM, AD, YK, BK, YS, GPG, LL, NB, and DMW are Regeneron employees/stockholders. CB reports grants or contracts from Gilead, Lilly, and GlaxoSmithKline for clinical trials. IH is a Regeneron consultant and Merck & Co. stockholder. ATH is a Regeneron employee/stockholder and former Pfizer employee and current stockholder. GDY is a Regeneron employee/stockholder and has issued patents (US Patent Nos. 10,787,501, 10,954,289, and 10,975,139) and pending patents, which have been licensed and receiving royalties, with Regeneron. SR, DA, MO, and SF have no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants who volunteered for the study; the investigators involved in this study; Kaitlyn Scacalossi, PhD, and Caryn Trbovic, PhD, from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals for medical writing support; and Prime Global, Knutsford, UK, for formatting and copyediting suggestions.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.06.045.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Avanzato VA, Matson MJ, Seifert SN, Pryce R, Williamson BN, Anzick SL, et al. Case study: prolonged infectious SARS-CoV-2 shedding from an asymptomatic immunocompromised individual with. Cell. 2020;183:1901–1912. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum A, Fulton BO, Wloga E, Copin R, Pascal KE, Russo V, et al. Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science. 2020;369:1014–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum A, Kyratsous CA. SARS-CoV-2 spike therapeutic antibodies in the age of variants. J Exp Med. 2021;218 doi: 10.1084/jem.20210198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird S, Panopoulou A, Shea RL, Tsui M, Saso R, Sud A, et al. Response to first vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with multiple myeloma. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e389–e392. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying medical conditions associated with high risk for severe COVID-19: information for healthcare professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html, 2021a (accessed 3 November 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html, 2021b (accessed 3 November 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Interim infection prevention and control recommendations to prevent SARS-CoV-2 spread in nursing homes. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/long-term-care.html, 2021c (accessed 3 November 2021).

- Copin R, Baum A, Wloga E, Pascal KE, Giordano S, Fulton BO, et al. The monoclonal antibody combination REGEN-COV protects against SARS-CoV-2 mutational escape in preclinical and human studies. Cell. 2021;184:3949–3961. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration, Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes monoclonal antibody for treatment of COVID-19. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-monoclonal-antibody-treatment-covid-19, 2020 (accessed 25 August 2021).

- Food and Drug Administration, FDA authorizes REGEN-COV monoclonal antibody therapy for post-exposure prophylaxis (prevention) for COVID-19. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-authorizes-regen-cov-monoclonal-antibody-therapy-post-exposure-prophylaxis-prevention-covid-19, 2021 (accessed 25 August 2021).

- Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization 091. https://www.fda.gov/media/145610/download, 2022 (accessed 10 February 2022).

- GOV.UK, Summary of product characteristics for Ronapreve. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-ronapreve/summary-of-product-characteristics-for-ronapreve, 2021 (accessed 1 December 2021).

- Hansen J, Baum A, Pascal KE, Russo V, Giordano S, Wloga E, et al. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science. 2020;369:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz R, Dahl RM, Dooling KL. Prevalence of immunosuppression among US adults, 2013. JAMA. 2016;316:2547–2548. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuritzkes DR. Bamlanivimab for prevention of COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;326:31–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lontok K. American Society for Microbiology, How effective are COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised people? https://asm.org/Articles/2021/August/How-Effective-Are-COVID-19-Vaccines-in-Immunocompr, 2021 (accessed 1 September 2021).

- Ludwig S, Zarbock A. Coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2: a brief overview. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:93–96. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro C. Covid-19: 40% of patients with weakened immune system mount lower response to vaccines. BMJ. 2021;374:n2098. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien MP, Forleo-Neto E, Musser BJ, Isa F, Chan KC, Sarkar N, et al. Subcutaneous REGEN-COV antibody combination to prevent Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1184–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien MP, Forleo-Neto E, Sarkar N, Isa F, Hou P, Chan KC, et al. Effect of subcutaneous casirivimab and imdevimab antibody combination vs placebo on development of symptomatic COVID-19 in early asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327:432–441. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group Casirivimab and imdevimab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2022;399:665–676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00163-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Regeneron's next generation monoclonal antibodies are active against all known variants of concern, including both omicron and delta. https://investor.regeneron.com/static-files/4aed42a1-3d26-48af-bd01-3f0c92938c11, 2021 (accessed 6 January 2022).

- Rosenthal N, Cao Z, Gundrum J, Sianis J, Safo S. Risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality in a US national sample of patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenforde MW, Olson SM, Self WH, Talbot HK, Lindsell CJ, Steingrub JS, et al. Effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines against COVID-19 among hospitalized adults aged ≥65 Years – United States, January-March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:674–679. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7018e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BI, Kenney B, Malani PN, Clauw DJ, Nallamothu BK, Waljee AK. Prevalence of immunosuppressive drug use among commercially insured US adults, 2018–2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, Ali S, Gao H, Bhore R, et al. REGEN-COV antibody combination and outcomes in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:e81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020 2020, (accessed 16 September 2021).

- Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, et al. Author Correction: a new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;580:E7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2202-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, and statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities (e.g., Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, etc.), if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant reidentification. Requests should be submitted to https://vivli.org/. ClinicalTrials.gov National Clinical Trial number is NCT04519437.