Abstract

HaloTag is a modified haloalkane dehalogenase used for many applications in chemical biology including protein purification, cell-based imaging, and cytosolic penetration assays. While working with purified, recombinant HaloTag protein, we discovered that HaloTag forms an internal disulfide bond under oxidizing conditions. In this work, we describe this internal disulfide formation and the conditions under which it occurs, and we identify the relevant cysteine residues. Further, we develop a mutant version of HaloTag, HaloTag8, that maintains activity while avoiding internal disulfide formation altogether. While there is no evidence that HaloTag is prone to disulfide formation in intracellular environments, researchers using recombinant HaloTag, HaloTag expressed on the cell surface, or HaloTag in the extracellular space should consider using HaloTag8 to avoid intramolecular disulfide formation.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The HaloTag system is a protein-based covalent capture technology that has been employed in a variety of applications, including protein purification, cell-based imaging, small molecule arrays, measuring cytosolic penetration of biomolecules, and neuropharmacology.1–7 The HaloTag enzyme, developed by Wood and colleagues, is a modified bacterial haloalkane dehalogenase that covalently reacts with haloalkanes.1 The reaction between terminal chloroalkanes and HaloTag is irreversible, biorthogonal, and kinetically fast. These features make HaloTag a valuable tool for chemical biology, cell biology, and biotechnology.

HaloTag has undergone a great deal of optimization.1,8–10 The most current version is known as HaloTag7 (commonly referred to as “HaloTag”), which contains ten site-specific mutations as well as an altered C-terminal sequence. These mutations together increased the rate constant by two orders of magnitude compared to the original version, and increased the expression of HaloTag fusion proteins by 7-fold.9,11,12 A small handful of biochemical assays were fundamental to optimizing HaloTag7, and these remain the primary means of characterizing HaloTag7 in vitro. The most common assays are fluorescence polarization (FP) with dye-labeled chloroalkanes, fluorescence intensity assays with fluorogenic probes, and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) assays where reactions are detected by in-gel fluorescence and/or mobility shifts.1,9–11,13–18

In previous work, we described the application of HaloTag7 to quantitative measurements of cytosolic penetration for chloroalkane-labeled molecules.18–20 Among other assays, we used gel-shift assays to compare HaloTag7 reactivity with various chloroalkane-labeled molecules. Unexpectedly, we observed a high-mobility protein band in experiments with recombinant, purified HaloTag7. Upon re-examining the literature, we discovered that this band was observed previously in several other gel-based assays, but never investigated.1,9,11,17 Here, we identify this band as oxidized HaloTag7 with a single, intramolecular disulfide. We characterize the formation of this disulfide bond under various conditions and compare reaction kinetics of the oxidized and unoxidized forms. Further, we develop a mutant, HaloTag8, that is resistant to intramolecular disulfide formation.

Results and Discussion

Detection of higher-mobility band for HaloTag7.

In previous work, we compared the relative reactivities of a diverse set of chloroalkane-tagged molecules with recombinant, purified HaloTag7. These experiments were performed as controls for the chloroalkane penetration assay, a HaloTag-based cytosolic penetration assay.18–20 We could not use FP or fluorescence-based gel assays because the molecules we prepared for the chloroalkane penetration assay did not have a fluorescent dye.1,9,13 Thus, we used a gel-shift assay to directly visualize the reaction with chloroalkane-tagged molecules. Gel-shift assays are routinely used to analyze extent of reaction of HaloTag7 and HaloTag7 fusion proteins with chloroalkane-tagged molecules, using either recombinant HaloTag7 or HaloTag7 present in the lysates of transfected mammalian cells.1,17,21,22

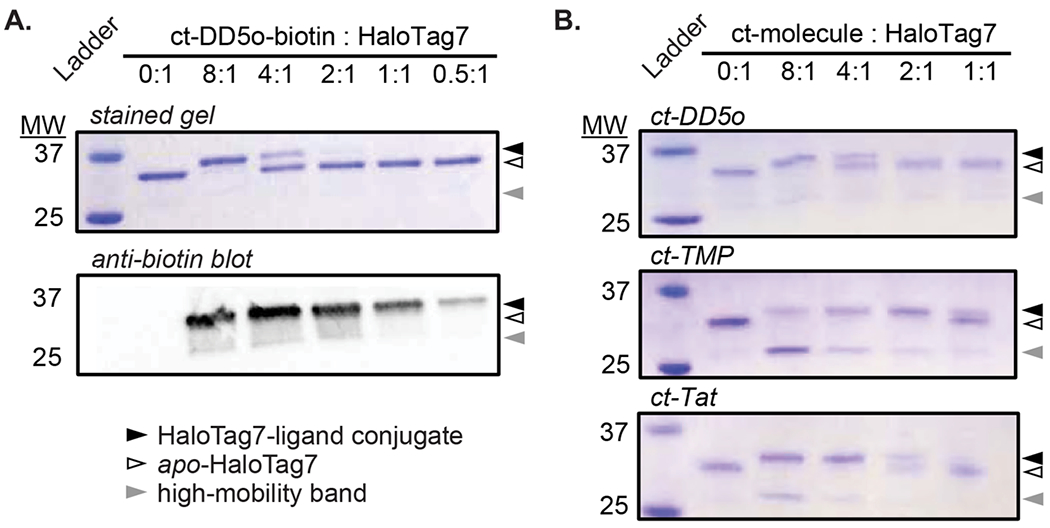

A representative example is the reaction between HaloTag7 and a chloroalkane-tagged biotinylated peptide, ct-DD5o-biotin (Table S1, Fig. S1). The unbiotinylated version of the peptide, ct-DD5o, is a cell-penetrant, autophagy-inducing stapled peptide.18,19 ct-DD5o was labelled with biotin to allow direct detection of HaloTag7-peptide adducts. When recombinant HaloTag7 was incubated with an excess of ct-DD5o-biotin, we observed a lower-mobility band consistent with an increase in molecular weight upon reaction with the chloroalkane-tagged molecule (upper band, Fig. 1A). The intensity of this lower-mobility band decreased with decreasing concentration of ct-molecule, and it disappeared at a low ratio of ct-molecule to HaloTag7. This result is consistent with the lower-mobility band being the covalent reaction product of ct-DD5o and HaloTag7. We confirmed these results by performing anti-biotin Western blots on the same samples. The relative amount of biotinylated protein correlated directly to the concentration dependence of the observed band shift (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Gel shift assay reveals an unexpected, higher-mobility band.

A. Recombinant HaloTag7 (5 μM; position on gel indicated by white triangle) was incubated with the indicated equivalents of ct-DD5o-biotin. Samples were denatured, resolved on a non-reducing SDS-PAGE gel, and either stained with Coomassie or detected by an anti-biotin Western blot. The lower-mobility band (black triangle) represents alkylation of HaloTag7 with ct-DD5o-biotin. The faint, higher-mobility band is indicated with a gray triangle. B. Gel shift assays with various chloroalkane-tagged molecules (ct-molecules) each show a higher-mobility band (adapted from Peraro et al. 2018).18 Sequences and structures of each ct-molecule are shown in Table S1 and Fig. S1, respectively. All images are representative of three independent replicates.

In addition to the appearance of an upper (lower-mobility) band, in some cases we also observed the unexpected appearance of a lower (higher-mobility) band with apparent molecular weight near 27 kDa (Fig. 1B). This band was faint in some trials, and more prominent in other trials (Fig. 1B). A faint higher-mobility band was also observed in anti-biotin Western blots (Fig. 1A), indicating that the ~27 kDa band contains at least some covalently labeled HaloTag7. Upon closer inspection of the literature, a similar higher-mobility band can be observed in several previous gel shift assays and Western blots.1,9,11,17 Some previous work attributed these bands to degradation products, while others did not address them at all. We decided to assess the identity of the higher-mobility band observed on these gels.

Higher-mobility band corresponds to HaloTag7 with an internal disulfide.

We first suspected proteolysis, either mediated by an unknown catalytic function of HaloTag7 or by trace proteases. However, mass spectrometry of the band extracted from the gel (Fig. S2), a gel shift assay on HaloTag7 treated with protease inhibitors (Fig. S3), and a gel shift assay with a HaloTag mutant lacking the catalytic aspartate (Fig. S4) did not support this hypothesis. Together, these data suggested that the higher-mobility band was not a cleavage product of HaloTag7.

We next hypothesized that the higher-mobility band was full-length protein migrating anomalously through the polyacrylamide gel. One reason for anomalous mobility in PAGE is internal disulfide formation.23–25 A gel shift assay of HaloTag7 under reducing and non-reducing conditions supported this hypothesis, as we observed the disappearance of the lower band in the presence of excess reducing agent (Fig. 2A). When recombinant HaloTag7 was incubated with peptides such as ct-DD5o, we had used 0.05% to 0.5% DMSO, which was a byproduct of diluting peptide stocks that were stored at high concentration in 100% DMSO. DMSO can promote oxidation, but it can also promote denaturation of folded proteins. Thus, we next sought to determine whether the apparent oxidation would be observed in samples exposed to air without DMSO present. Even after only 5-10 minutes of air exposure, PAGE of HaloTag7 revealed a faint higher-mobility band indicating a small amount of oxidized product (Fig. 2B). The intensity of the band corresponding to the oxidized product increased in a time-dependent manner, consistent with air oxidation. After 24 hours, the sample was roughly 50% oxidized, based on the relative intensities of upper and lower bands. Similar results were obtained when HaloTag7 was oxidized with the thiol-specific oxidant 5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB, Fig. S13). Observing the same higher-mobility band after incubation under three conditions known to promote disulfide formation26–28 supported the conclusion that the higher-mobility band represents HaloTag7 with an internal disulfide. While partial denaturation of HaloTag7 could not be ruled out as a contributing factor, observation of the higher-mobility band using three different oxidizing conditions and the observation of the higher-mobility band under a variety of other experimental conditions1,9,11,17 supported oxidation, not denaturation, as the principal cause of disulfide formation.

Figure 2. HaloTag7 forms an internal disulfide under oxidizing conditions.

A. Recombinant HaloTag7 (5 μM) was incubated with a high concentration of DMSO (25%) to promote oxidation, then resolved on a SDS-PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie. DMSO oxidation (or, possibly, denaturation followed by oxidation) produced a strong higher-mobility band. Reduction of the oxidized sample with 50 mM DTT dramatically decreased the intensity of the higher-mobility band. HaloTag7 incubated with ct-DD5o in the absence of DMSO had no detectable higher-mobility band. Gel image is representative of three independent replicates. B. Samples of 5 μM HaloTag7 were prepared and exposed to air for the indicated time points, then resolved on an SDS-PAGE gel and stained with SYPRO Ruby for increased sensitivity. Adding 50 mM DTT prevents the formation of the lower band, even after 24 hours. Gel image is representative of three independent replicates. C. A tryptic digest was performed on HaloTag7 samples that were incubated in PBS (untreated), in PBS with 20% DMSO, and in PBS with 20% DMSO with subsequent addition of 1 mM DTT. Samples were analyzed by LC-MS, and the base peak chromatograms were extracted from the total ion chromatogram. The m/z of all peaks corresponded to expected tryptic fragments. The peaks denoted with an asterisk correspond to a m/z of 444.73 Da in the +4 charge state, which matches the expected mass of the two cysteine-containing tryptic fragments connected by a disulfide bond (expected m/z 444.73 Da). The observed exact mass at this retention time is 1774.88 Da (expected exact mass 1774.88 Da). D. An identical experiment but with 1 equivalent DTNB used as the oxidant. E. The crystal structure of apo-HaloTag7 illustrates that the only two cysteines (purple) are located about 21 Angstroms apart.15 Key active site residues are shown in teal.

Next, we aimed to observe the hypothesized disulfide directly by mass spectrometry. HaloTag7 was incubated with and without DMSO, and the tryptic fragments of each sample were analyzed by both MALDI-TOF-MS and LC-MS. There are only two cysteines in HaloTag7, and thus there was only one possible disulfide-bridged tryptic fragment. By MALDI-TOF MS, a mass consistent with the expected disulfide-bridged tryptic fragment was identified in the DMSO-oxidized sample, but not in the same sample with DTT added (Fig. S5). LC-MS analysis also demonstrated the presence of the same disulfide-bridged tryptic fragment in the DMSO-oxidized HaloTag7, and the absence of this fragment following addition of DTT (Fig. 2C, Figs. S6–S7). A mass corresponding to the expected disulfide-bridged tryptic fragment was detected in the LC-MS base peak chromatogram in the untreated sample (Fig. 2C) though not on gels (Fig. 2A), representing a small amount of oxidation presumably due to transient exposure to air. We attribute this discrepancy to the high sensitivity of mass spectrometry. Supporting this conclusion, we observed a barely detectable higher-mobility band when untreated HaloTag7 was stained with the more sensitive SYPRO Ruby instead of Coomassie (Fig. 2B). Similar results were observed for HaloTag7 oxidized with DTNB (Fig. 2D, Figs. S8–S10). The direct observation of the disulfide-linked tryptic fragment confirmed that HaloTag7 undergoes intramolecular disulfide formation under oxidizing conditions.

Internal disulfide formation corresponds to decreased HaloTag7 activity.

In the crystal structure of apo-HaloTag7,15 the two cysteines are roughly 21 angstroms apart (Fig. 2E). One of these cysteines is solvent-exposed and the other is near the protein surface but not fully solvent-exposed. A structural shift large enough to form the observed disulfide seemed highly likely to decrease or abolish enzymatic activity.

To address whether disulfide formation impairs activity, we first determined whether the total amount of active protein remained the same in the untreated and the DMSO-oxidized samples. To this end, we prepared samples of HaloTag7 that were untreated, oxidized with 20% DMSO or 1 equivalent of DTNB for 3 hours, or oxidized with DMSO or DTNB and then reduced with DTT. After removal of DMSO or DTNB by dialysis, we treated these samples with a chloroalkane-labeled biotin (ct-PEG4-biotin; Fig. S1). We analyzed the samples by SDS-PAGE and performed a Western blot to selectively detect HaloTag7 that had reacted covalently with the ct-PEG4-biotin. In the DMSO-treated sample, the ratio of higher-mobility band to lower-mobility band indicates that more than 50% of the protein was oxidized (Fig. 3A). However, the corresponding bands on the anti-biotin Western blot do not have the same intensity ratio; instead, the higher-mobility (oxidized) band is slightly fainter than the lower-mobility (unoxidized) band. This discrepancy suggests that activity is greatly reduced after DMSO oxidation. Further, when the DMSO-oxidized HaloTag7 is subsequently reduced using an excess of DTT and then reacted with ct-PEG4-biotin, the resulting band in the anti-biotin Western blot is less intense than the band resulting from reaction of untreated HaloTag7 with ct-PEG4-biotin (Fig. 3A). This result implies that oxidizing and then reducing the protein does not fully rescue its activity. To help rule out denaturation as the cause of the decreased activity, we performed identical experiments but with 1 equivalent of DTNB instead of 20% DMSO (Fig. 3B). Similar results were observed in the DTNB-treated samples, with the stained gel indicating approximately 50% oxidation, but with the anti-biotin blot indicating that the oxidized material was less reactive with ct-PEG4-biotin than the unoxidized material (Fig. 3B). Overall, these data indicate that oxidation decreases the total amount of active protein, and this effect is not completely reversed when the material is subsequently reduced.

Figure 3. Impact of internal disulfide formation on the activity of HaloTag7.

A. Recombinant HaloTag7 (5 μM) was oxidized with 20% DMSO, then reacted with ct-PEG4-biotin. The sample in the final lane was oxidized first, then reduced with 1 mM DTT, and then incubated with ct-PEG4-biotin. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and either stained with Coomassie or detected by an anti-biotin Western blot. Structure of ct-PEG4-biotin is shown in Fig. S1. Images are representative of two independent replicates. B. Recombinant HaloTag7 (5 μM) was oxidized with 1 equivalent DTNB, then reacted with ct-PEG4-biotin. The sample in the final lane was oxidized first, reduced with 1 mM DTT, and then incubated with ct-PEG4-biotin. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and either stained with Coomassie or detected by an anti-biotin Western blot. Images are representative of two independent replicates. C. Time-dependent FP assays of HaloTag7 incubated with PBS (untreated), 20% DMSO, or 20% DMSO followed by reduction with 1 mM DTT, using chloroalkane-fluorescein as the probe. Second-order rate constants were fit to the FP data as described.29–32 No significant change in rate was observed among the three conditions. D. Identical time-dependent FP experiments for air-oxidized HaloTag7. E. Identical time-dependent FP experiments for HaloTag7 oxidized with 1 or 2 equivalents of DTNB. All FP data are shown as averages and standard error of the mean for three independent replicates.

To further address how internal disulfide formation affects HaloTag7 activity, we used FP to measure HaloTag7 reaction kinetics as described.1,9,13 We prepared samples of HaloTag7 that were untreated, oxidized with 20% DMSO, oxidized with prolonged air exposure, and oxidized with DTNB. We also prepared samples that were oxidized, then reduced with DTT. Extent of oxidation in each sample was estimated using SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3, Fig. S11–S13). To measure rate, we added a limiting concentration of chloroalkane-fluorescein to each sample and monitored FP of the chloroalkane-fluorescein over time. We then calculated an apparent second-order rate constant for each sample as described (see Materials and Methods).29–32 The rate constant for DMSO-oxidized HaloTag7 was statistically similar to untreated HaloTag7 and HaloTag7 oxidized with DMSO and then reduced with DTT (Fig. 3C, Fig. S11). We found that treatment with a high percentage of DMSO was the most consistent method for producing oxidized HaloTag7, but these conditions could also partially denature HaloTag7. Thus, we also measured reaction kinetics and total extent of reaction under two additional conditions: freshly oxygenated aqueous buffer with continuous exposure to air, and treatment with DTNB. As with DMSO-treated samples, untreated and oxidized samples still had statistically similar second-order rate constants (Table S3). The FP data for the untreated and air-oxidized samples were similar to one another (Fig. 3D), yet oxidation with prolonged exposure to air was inconsistent, with the oxidized product contributing between 5-30% of the total sample (Fig. S12). Oxidation with DTNB was slightly more effective than oxidation with prolonged air exposure and allowed for a shorter incubation time (Fig. S13). As with the other oxidation methods, the FP data for the untreated and DTNB-treated samples were not significantly different (Fig. 3E), and DTNB treatment did not significantly alter second-order rate constant compared to untreated sample (Table S3). Our measured rate constants are somewhat lower than some reported values for recombinant HaloTag7;1,9,11 this may be due to partial denaturation during the lengthy incubation phases at room temperature, which may contribute to the lack of difference among oxidized and non-oxidized HaloTag7 samples. Effects of denatured material are difficult to rule out completely. Thus, we conclude that some denaturation may occur upon treatment with DMSO, upon air oxidation, and upon treatment with DTNB, and that it remains unclear whether denaturation leads to oxidation, or whether formation of an internal disulfide promotes denaturation.

Engineered variant HaloTag8 is resistant to internal disulfide formation.

The formation of an internal disulfide within HaloTag7 was unexpected, and it could have unanticipated effects on applications, especially in oxidizing environments. Thus, we sought to produce a HaloTag mutant that would be oxidation-resistant. We performed site-directed mutagenesis to prepare the C61S and C262S single mutants, and the C61S/C262S double mutant (which we refer to as HaloTag8). When analyzed by CD spectroscopy, HaloTag8 had an identical spectrum compared to HaloTag7 (Fig. 4A). These data suggest that the C61S and C262S mutations did not alter the overall structure of HaloTag7. The reaction rate for the reaction of HaloTag8 with chloroalkane-fluorescein was identical to that of HaloTag7 (Fig. 4B), and little change in the reaction rate was observed for HaloTag8 upon exposure to 20% DMSO or DTNB (Figs. S14, S15). Next, we examined whether the new mutants could form a higher-mobility band on SDS-PAGE. No higher-mobility band was observed for HaloTag8 after incubation with 20% DMSO (Fig. 4C). No higher-mobility band was also observed for either the C61S or the C262S single mutant after incubation in 20% DMSO (Fig. 4D). Instead, for the single mutants, we observed formation of a band corresponding to a HaloTag dimer, suggesting intermolecular disulfide formation (Fig. 4D). These data further support the conclusion that each of the two cysteines in HaloTag7 is redox-active. Finally, we used anti-biotin Western blots to test whether the total activity of HaloTag8 with ct-PEG4-biotin was affected by oxidizing conditions. In agreement with the kinetics results, we observed that HaloTag8 activity was not affected at all by exposure to 20% DMSO or 1 equivalent of DTNB (Fig. 4E–F). These results are in stark contrast to similar assays with HaloTag7 (Fig. 3A–B). Overall, these data further support the conclusion that HaloTag8 completely resists oxidation. Also, since HaloTag8 maintained full activity in the presence of 20% DMSO or 1 equivalent DTNB, these data strongly suggest that the decrease in activity observed in the oxidized HaloTag7 samples are primarily due to internal disulfide formation, rather than denaturation.

Figure 4. HaloTag8 maintains structure and activity, and HaloTag8 is insensitive to oxidizing environments.

A. HaloTag7 and HaloTag8 show identical CD spectra, suggesting that the cysteine-to-serine mutations do not alter secondary structure. CD spectra are smoothed, averaged data from three independent trials. B. HaloTag7 and HaloTag8 show similar kinetics in a fluorescence polarization assay with 20 nM chloroalkane-fluorescein. Each curve was normalized to its own apparent maximum FP value. FP data are averages and standard error of the mean for three independent replicates. C,D. Gel shift assays were performed with the C61S mutant, the C262S mutant, and the double mutant HaloTag8. Each protein (5 μM) was prepared without oxidation (PBS only), with oxidation using 25% DMSO, and with DMSO oxidation followed by treatment with 50 mM DTT. No higher-mobility band was detected for C61S, C262S, or HaloTag8 oxidized with DMSO. A low-mobility band, roughly corresponding to a dimer from an intermolecular disulfide, was observed for C61S and C262S mutants. All gel images are representative of three independent replicates. E. Recombinant HaloTag8 (5 μM) was oxidized with 20% DMSO, then reacted with ct-PEG4-biotin. The sample in the final lane was treated with DMSO first, then reduced with 1 mM DTT, and then incubated with ct-PEG4-biotin. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and either stained with Coomassie or detected by an anti-biotin Western blot. Images are representative of two independent replicates. F. Recombinant HaloTag8 (5 μM) was oxidized with 1 equivalent DTNB, then reacted with ct-PEG4-biotin. The sample in the final lane was treated with DTNB first, then reduced with 1 mM DTT, and then incubated with ct-PEG4-biotin. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and either stained with Coomassie or detected by an anti-biotin Western blot. Images are representative of two independent replicates.

In summary, we have shown that recombinant HaloTag7 forms an internal disulfide under oxidizing conditions, including exposure to DMSO, air, and the thiol oxidant DTNB. Oxidation, or possibly concurrent oxidation and denaturation, decreased total enzymatic activity when examined by gel shift assays, yet maintained statistically similar rate constants with chloroalkane-labeled fluorescein when analyzed at shorter time points. We speculate that the unexpected redox sensitivity of HaloTag7 could be a redox-sensing function intrinsic to the original haloalkane dehalogenase. In addition, these observations inform new best practices when working with HaloTag7. Recombinant HaloTag7 should be assayed in a reducing environment whenever possible to avoid loss of activity, and to prevent confounding data such as the appearance of a higher-mobility band by SDS-PAGE. Care should be taken in interpreting data obtained with HaloTag7 produced in an oxidizing environment, such as the secretory pathway or the cell surface. Given the rapid reduction of the internal disulfide by 1 mM DTT, it seems unlikely that HaloTag7 expressed in the cytosol would be prone to disulfide formation. However, the redox-active nature of its two cysteines should be considered even in intracellular assays. Finally, we reported the development of HaloTag8, which has a similar structure and reactivity, yet is insensitive to oxidizing environments. Adoption of HaloTag8, especially in biochemical assays and other oxidizing environments, would avoid disulfide formation, avoid cross-reactivity with other thiol-reactive reagents, improve enzyme stability, and improve assay reproducibility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM127585. We thank Joseph McEwen and Lara Murray for their assistance with instrumentation and data processing.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Additional Materials and Methods, molecule characterization and structures, and supporting data sets.

References

- (1).Los GV, Encell LP, Mcdougall MG, Hartzell DD, Karassina N, Zimprich C, Wood MG, Learish R, Ohana RF, Urh M, et al. (2008) HaloTag: A Novel Protein Labeling Technology for Cell Imaging and Protein Analysis. ACS Chem. Biol 3, 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).England CG, Luo H, and Cai W (2015) HaloTag Technology: A Versatile Platform for Biomedical Applications. Bioconjug. Chem 26, 975–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Ohana RF, Levin S, Wood MG, Zimmerman K, Dart ML, Schwinn MK, Kirkland TA, Hurst R, Uyeda HT, Encell LP, and Wood KV (2016) Improved Deconvolution of Protein Targets for Bioactive Compounds Using a Palladium Cleavable Chloroalkane Capture Tag. ACS Chem Biol 11, 2608–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shields BC, Kahuno E, Kim C, Apostolides PF, Brown J, Lindo S, Mensh BD, Dudman JT, Lavis LD, and Tadross MR (2017) Deconstructing behavioral neuropharmacology with cellular specificity. Science (80-. ). 356, eaaj2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).San Segundo-Acosta P, Montero-Calle A, Fuentes M, Rábano AR, Villalba M, and Barderas R (2019) Identification of Alzheimer’s Disease Autoantibodies and Their Target Biomarkers by Phage Microarrays. J Proteome Res 18, 2940–2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Stuber JC, Kast F, and Plü A. (2019) High-Throughput Quantification of Surface Protein Internalization and Degradation. ACS Chem Biol 14, 1154–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ballister ER, Aonbangkhen C, Mayo AM, Lampson MA, and Chenoweth DM (2014) Localized light-induced protein dimerization in living cells using a photocaged dimerizer. Nat. Commun 5, 5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Bosma T, Pikkemaat MG, Kingma J, Dijk J, and Janssen DB (2003) Steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of halopropane conversion by a Rhodococcus haloalkane dehalogenase. Biochemistry 42, 8047–8053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Encell LP, Friedman Ohana R, Zimmerman K, Otto P, Vidugiris G, Wood MG, Los GV, McDougall MG, Zimprich C, Karassina N, Learish RD, et al. (2012) Development of a Dehalogenase-Based Protein Fusion Tag Capable of Rapid, Selective and Covalent Attachment to Customizable Ligands. Curr. Chem. Genomics 6, 55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Friedman Ohana R, Encell LP, Zhao K, Simpson D, Slater MR, Urh M, and Wood KV (2009) HaloTag7: A genetically engineered tag that enhances bacterial expression of soluble proteins and improves protein purification. Protein Expr. Purif 68, 110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kaushik S, Prokop Z, Damborsky J, and Chaloupkova R (2017) Kinetics of binding of fluorescent ligands to enzymes with engineered access tunnels. FEBS J. 284, 134–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Krooshof GH, Kwant EM, Damborský J, Koča J, and Janssen DB (1997) Repositioning the catalytic triad aspartic acid of Haloalkane dehalogenase: Effects on stability, kinetics, and structure. Biochemistry 36, 9571–9580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Los GV, Darzins A, Zimprich C, Karassina N, Learish R, Mcdougall MG, Encell LP, Friedman-Ohana R, Wood M, et al. (2008) One Fusion Protein: Multiple Functions HaloTag™ Interchangeable Labeling Technology for Cell Imaging, Protein Capture and Immobilization. Promega 89, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ohana RF, Kirkland TA, Woodroofe CC, Levin S, Uyeda HT, Otto P, Hurst R, Robers MB, Zimmerman K, Encell LP, and Wood KV (2015) Deciphering the Cellular Targets of Bioactive Compounds Using a Chloroalkane Capture Tag. ACS Chem Biol 10, 2316–2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Liu Y, Miao K, Dunham NP, Liu H, Fares M, Boal AK, Li X, and Zhang X (2017) The Cation–π Interaction Enables a Halo-Tag Fluorogenic Probe for Fast No-Wash Live Cell Imaging and Gel-Free Protein Quantification. Biochemistry 56, 1585–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Clark SA, Singh V, Vega Mendoza D, Margolin W, and Kool ET (2016) Light-Up “channel Dyes” for Haloalkane-Based Protein Labeling in Vitro and in Bacterial Cells. Bioconjug. Chem 27, 2839–2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ohana RF, Hurst R, Vidugiriene J, Slater MR, Wood KV, and Urh M (2011) HaloTag-based purification of functional human kinases from mammalian cells. Protein Expr. Purif 76, 154–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Peraro L, Deprey KL, Moser MK, Zou Z, Ball HL, Levine B, and Kritzer JA (2018) Cell Penetration Profiling Using the Chloroalkane Penetration Assay. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 11360–11369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Peraro L, Zou Z, Makwana KM, Cummings AE, Ball HL, Yu H, Lin YS, Levine B, and Kritzer JA (2017) Diversity-Oriented Stapling Yields Intrinsically Cell-Penetrant Inducers of Autophagy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 7792–7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Deprey K, and Kritzer JA (2020) Quantitative measurement of cytosolic penetration using the Chloroalkane Penetration Assay. Methods Enzymol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhang Y, So MK, Loening AM, Yao H, Gambhir SS, and Rao J (2006) HaloTag protein-mediated site-specific conjugation of bioluminescent proteins to quantum dots. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 45, 4936–4940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tomoshige S, Hashimoto Y, and Ishikawa M (2016) Efficient protein knockdown of HaloTag-fused proteins using hybrid molecules consisting of IAP antagonist and HaloTag ligand. Bioorganic Med. Chem 24, 3144–3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rath A, Glibowicka M, Nadeau VG, Chen G, and Deber CM (2009) Detergent binding explains anomalous SDS-PAGE migration of membrane proteins. PNAS 106, 1760–1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Shi Y, Mowery RA, Ashley J, Hentz M, Ramirez AJ, Bilgicer B, Slunt-Brown H, Borchelt DR, and Shaw BF (2012) Abnormal SDS-PAGE migration of cytosolic proteins can identify domains and mechanisms that control surfactant binding. Protein Sci. 21, 1197–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Miyake J, Ochiai-Yanagi S, Kasumi T, and Takagi’ T (1978) Isolation of a Membrane Protein from R. rubrum Chromatophores and Its Abnormal Behavior in SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis Due to a High Binding Capacity for SDS 1. J Biochem 83, 1679–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Tam JP, Wu C-R, Liu W, and Zhang J-W (1991) Disulfide Bond Formation in Peptides by Dimethyl Sulfoxide. Scope and Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc [Google Scholar]

- (27).Habeeb AFSA (1972) Reaction of Protein Sulfhydryl Groups with Ellman’s Reagent. Methods Enzymol. 25, 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Eilen E, and Krakow JS (1977) Cyclic AMP-mediated intersubunit disulfide crosslinking of the cyclic AMP receptor protein of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol 114, 47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Corbett JF (1972) Pseudo first-order kinetics. J. Chem. Educ 49, 663. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Schnell S, and Mendoza C (2004) The condition for pseudo-first-order kinetics in enzymatic reactions is independent of the initial enzyme concentration. Biophys. Chem 107, 165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lin J, and Wang L (2009) Comparison between linear and non-linear forms of pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order adsorption kinetic models for the removal of methylene blue by activated carbon. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. China 3, 320–324. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Simonin JP (2016) On the comparison of pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws in the modeling of adsorption kinetics. Chem. Eng. J 300, 254–263. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.