Abstract

Introduction:

We compare nursing-home and hospital admissions among residents with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) in memory-care assisted living to those in general assisted living.

Methods:

Retrospective study of Medicare beneficiaries with ADRD in large (>25 bed) assisted-living communities. We compared admission to a hospital, to a nursing home, and long-term (>90 day) admission to a nursing home between the two groups, using risk differences and survival analysis.

Results:

Residents in memory-care assisted living had a lower adjusted risk of hospitalization (risk difference = −1.8 percentage points [P = .014], hazard ratio = 0.93 [0.87–1.00]), a lower risk of nursing-home admission (risk difference = −2.2 percentage points [P < .001], hazard ratio = 0.87 [−.79–0.95]), and a lower risk of a long-term nursing home admission (risk difference = −1.1 percentage points [P < .001], hazard ratio = 0.71 [0.57–;0.88]).

Discussion:

Memory care is associated with reduced rates of nursing-home placement, particularly long-term stays, compared to general assisted living.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, assisted living, dementia care, hospitalization, memory care, nursing home admission, residential care

1 |. BACKGROUND

Assisted-living communities are important providers of care to older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD). In 2016, 23% of assisted-living communities offered memory care and 8% served residents with dementia.1 Among traditional Medicare enrollees at larger assisted-living communities (25+ units), 30% have a diagnosis of ADRD.2

In this article, we use the phrase “memory care” to describe assisted-living communities that have a state-sanctioned license, certification, or designation for dementia care that sets them apart from “general” assisted living, that is, other licensed assisted-living communities in the state that do not carry a memory-care endorsement. Other terms used in government regulations and in the academic literature to describe memory care include dementia special care and dementia care. Whatever the term used, memory care is a category that deserves study for two reasons. First, the designation signals to consumers that the assisted-living community is able to provide specific care for older adults with ADRD, even in states where memory care is a self-designation that entails minimal additional regulation or requirements. Second, residents pay nearly 40% more for memory care than general assisted living.3 Thus it is important to residents and their families, as well as policy makers, to understand whether memory-care designations achieve better outcomes.

Because there is no federal program to pay for assisted living, states are responsible for all oversight and regulation of assisted living. As a result, approaches to regulating the care of people with dementia vary widely from one state to another.4 Nearly all have guidelines for building design to protect residents from exiting unescorted, and most require specific training in dementia care for direct-care staff and administrators.5 Assisted-living communities in some states may also need to meet requirements for pre-admission assessments, consumer disclosure, and administrator training.6 Some states clearly define a dementia-specific license with more restrictive regulations, covering all relevant components of assisted-living licensure from staff training to door-locking mechanisms.7 The privileges afforded to a facility that is licensed or certified as ADRD-specific also vary. Some states allow only dementia-care facilities to market themselves as providing “memory care,” and some allow a higher rate to be charged for residents of such facilities who rely on the state Medicaid program for reimbursement.

Reports of some prior studies suggest that specialization in dementia care can improve quality of care. Admission to a nursing home with a dementia special care unit was found to lead to a reduction in the use of inappropriate antipsychotics, physical restraints, pressure ulcers, feeding tubes, and hospitalizations.8 When workers in assisted living are trained in dementia care, the residents with dementia have a higher quality of life–reduced depression, better medication adherence, and decreased emergency room use–compared to residents cared for by workers without the training.9 National data from 2010 indicate that in that year, only 14% of assisted-living residents with dementia lived in memory-care units.3 Previous literature comparing assisted-living residents with dementia in memory care to those in standard care found that people in memory care were similar or less severe in their medical co-morbidities but had lower cognitive function10; those studies did not find differences in mortality or in discharge to a more intensive level of care.11 No extant studies have examined health outcomes among a large, national sample of assisted-living residents in memory care.

Admissions to a nursing home or a hospital are important, person-centered outcomes. Whereas older adults who enter a rehabilitation or skilled-nursing facility may do so intending a short-term stay, it is reasonable to assume that most persons who move to an assisted-living community intend to establish a new home, or at least, age in place.12 Not only is any change of residence likely to be disruptive, disorienting, and upsetting–especially so for persons with dementia–but when the move is to a nursing home, a person has likely exchanged a more private and homelike environment for a more institutionalized setting. Similarly, admission to a hospital may represent potentially preventable injuries or illness. Hospital admission for a person with dementia can trigger distressed behaviors,13 delirium that can exacerbate cognitive deterioration,14 or expose the person to the risk of a hospital-acquired infection.

In this study, we aimed to (1) compare the characteristics of older adults with dementia who move to a memory-care community to those who move to an assisted-living community without memory care, and (2) determine the effect of moving to a memory-care community on hospitalization, length of hospital stay, nursing-home admission, and long-term nursing-home admission in the first 6 months.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Data sources

Our sources of administrative data on Medicare beneficiaries included the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF), inpatient Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files (MedPAR), outpatient Medicare claims, nursing-home Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessments, and the Home Health Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS). Data on assisted-living communities and memory-care designations came from a national census that was compiled by the authors from individual state licensing agencies in 2017.

2.2 |. Sample

The demographic and enrollment data of Medicare beneficiaries were drawn from the 2015–2017 MBSF. The Chronic Conditions Warehouse (CCW) segment of the MBSF was used to identify the health characteristics of beneficiaries. Our cohort included Medicare beneficiaries with an ADRD diagnosis who moved to assisted living any time from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2017, in one of 22 states where we are able to identify site-specific designations for memory care. Appendix 1 shows the states with memory-care licenses and those included in our analysis. To identify Medicare beneficiaries who moved to assisted living, we used facility addresses, OASIS, and Medicare Part B claims to create a finder file of validated nine-digit ZIP codes associated with 25+ bed assisted living.15 We looked for a change in the beneficiary’s nine-digit ZIP code from a ZIP code not associated with a large assisted-living community to a new nine-digit ZIP code corresponding to an assisted living with 25+ beds. We excluded Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage in the year before and during the year of their move, because diagnoses and utilization information are not available.

2.3 |. Measures

2.3.1 |. Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were any admission to an acute-care hospital and admission to a nursing home within 180 days of change of address to assisted living. We also examined nursing-home admissions that resulted in a long-term (>90 day) stay.

2.3.2 |. Exposure: memory care license

The exposure of interest was change of residence to a memory-care assisted living, compared to an assisted-living community without a specialized license. We defined memory care as a license, permit, certification, or designation conferred or subject to approval by a state agency that qualifies the assisted living to care for adults with ADRD or permits them to advertise services specific to dementia care.

2.3.3 |. Covariates

We adjusted for each resident’s age (in 5-year bins), gender, race, dual enrollment in both Medicare and Medicaid, chronic conditions, and the date of initial diagnosis of ADRD. As an additional marker for health status, we used claims data to identify healthcare utilization in the 12 months prior to moving to assisted living, including any emergency department utilization, hospitalization, admission to a hospital intensive care unit, admission to a nursing home or skilled nursing facility, or use of paid home health care.

In addition, as proxy measures for socioeconomic status and access, we adjusted for the county percentage of residents with a college education, unemployment rate, percentage of persons in poverty, median home value, rurality index [1–9], number of home health agencies per 1000 persons age 65 and older, and number of nursing home beds per 1000 persons age 65 and older. Because access to memory care may still be confounded by neighborhood characteristics after controlling for those measures, we also included the log of the linear distances to the nearest memory-care and general assisted-living communities to the centroid of the person’s previous ZIP code.

2.4 |. Analyses

We reported differences in the mean outcomes using inverse-propensity weights to adjust for differences between the two groups. Propensity scores were estimated using logistic models of the probability of entering memory care versus general assisted living, regressed on the covariates listed above and fixed effects for the state in which the assisted-living community was located. We excluded propensity ranges with insufficient overlapping support.16,17 To test the robustness of the findings, we stratified the sample into quintiles of the propensity score, and plotted the outcomes and 95% confidence intervals for each exposure. Because the groups may experience differential censoring due to mortality, we also estimated differences in time to outcomes using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional hazard ratios with inverse-propensity treatment weights. All analyses were conducted with SAS v.9.418 and Stata v.15.1.19

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Comparison of population characteristics

The final analytic sample included 20,646 people with ADRD who changed their residence to assisted living. Of these, 39% entered a memory-care community. Residents in memory care were older (mean = 84 years [standard deviation (SD) = 8.2] vs 82 [10.1]), less likely to be Black (2.1%%vs4.5%), and less likely to be dually enrolled in Medicaid (12.3% vs 26.0%). Memory care residents had a lower prevalence of chronic and mental health conditions compared to residents in general assisted living. The conditions with moderate differences in prevalence between the two groups (standardized difference greater than 10%) were schizophrenia (2.6% in memory care vs 7.7% in general care) and prior inpatient hospitalization (46.3% vs 48.1%). Beneficiaries with ADRD who moved to memory care came from counties with $20,000 lower median home, lower rurality index (2.2 [1.8] vs 2.4[1.9]), and more home health agencies per 1000 adults 65 and older (0.4 [0.48] vs 0.25 [0.36]). After applying inverse propensity weights, the samples were similar: all variables differed by less than 0.1 SD, except for distance to the nearest memory-care community (0.23 SD). Weighted sample means are reported in the Appendix, Table A2.

3.2 |. Comparison of outcomes

Table 2 shows the differences in hospital and nursing home admissions between the two types of assisted living. The risk of one or more hospital admissions was 26.5% in general care and 23.9% in memory care; the risk-adjusted difference in hospitalization was 1.8 percentage points lower for memory care (P = .014), representing a 7% difference from the average among residents of general assisted living. Among residents in general care, 15.5% had any nursing home admission within 6 months and 3.51% had a nursing home admission that resulted in a long-term stay; among beneficiaries who moved to memory care, 13.4% had any nursing home admission and 2.2% had a long-term nursing home admission. When adjusted for covariates, memory-care residents had 2.5 percentage point lower risk of nursing home admission within 180 days than general care residents (P < .001), representing a 16% decrease relative to general care. The adjusted probability of an admission to nursing home resulting in long-term (>90 day) stay was 1.0 percentage points lower in memory care (P < .001), a 28% lower risk of long-term nursing-home stay in memory care relative to general care.

TABLE 2.

Health care use and outcomes within 180 days after moving to assisted living (N = 20,646)

| General assisted living | Memory care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 12,523 (raw) N = 10,390.2 (wt) |

N = 123 (raw) N = 10,255.8 (wt) |

Unadjusted Difference | Adjusted difference(a) [95% CI] | Pr(diff|H0) | |

| Any acute inpatient hospital admission | 0.265 | 0.239 | −0.025 | −0.018 [−0.032, −0.004] | 0.014 |

| Any nursing home admission | 0.155 | 0.134 | −0.0207 | −0.022 [−0.033, −0.011] | <0.001 |

| Any long-term nursing home admission(b) | 0.0351 | 0.022 | −0.0131 | −0.010 [−0.015, −0.004] | <0.001 |

Notes: Data include traditional Medicare beneficiaries who changed address to a large (25+ units) general assisted-living community or a memory-care-designated assisted-living community from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2017.

Adjusted using inverse propensity weighted regression adjustment. Propensity score calculated using resident demographics, chronic conditions, previous health care use, and characteristics of their previous home county (see Table 1).

Long-term nursing home stay is defined as >90 days.

3.3 |. Robustness of findings

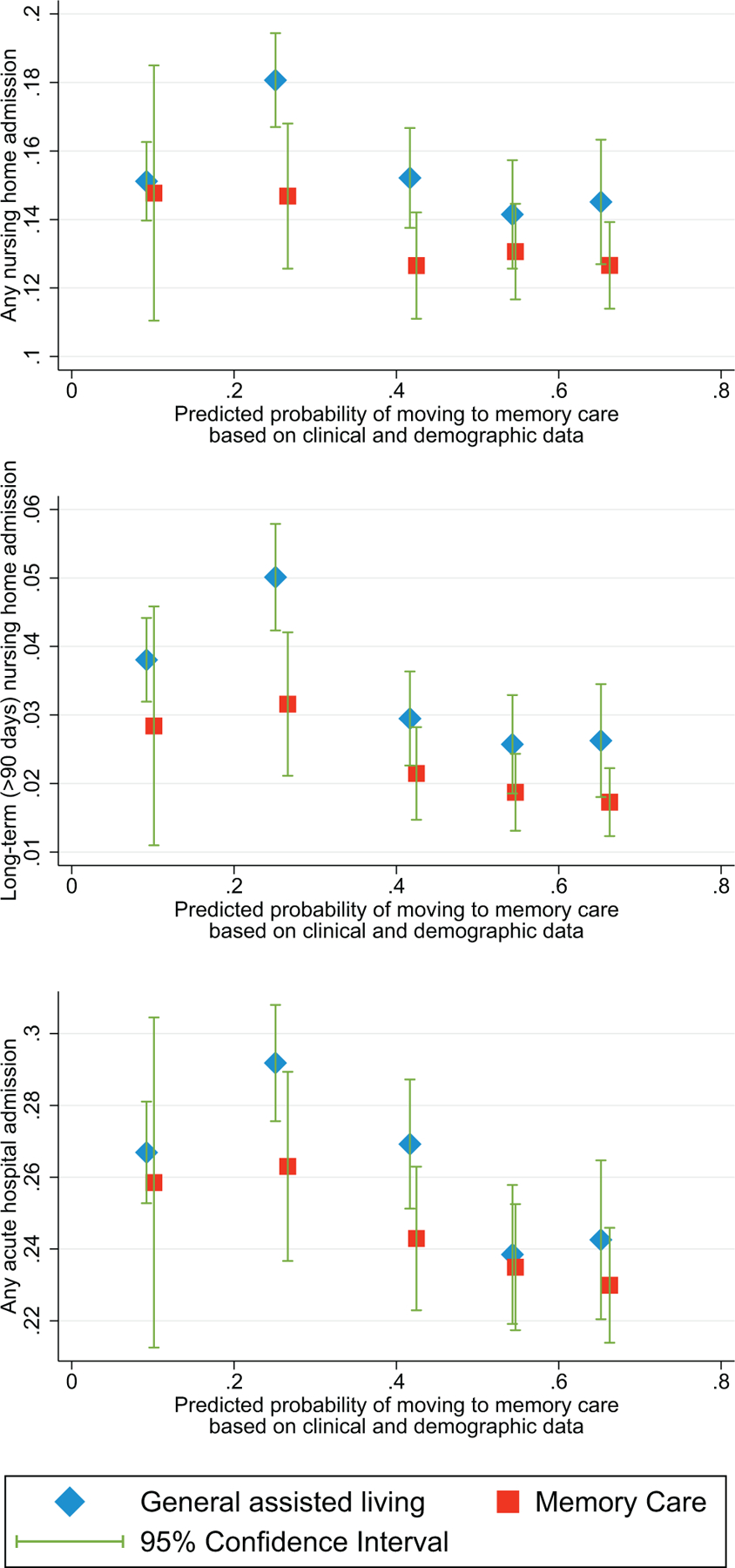

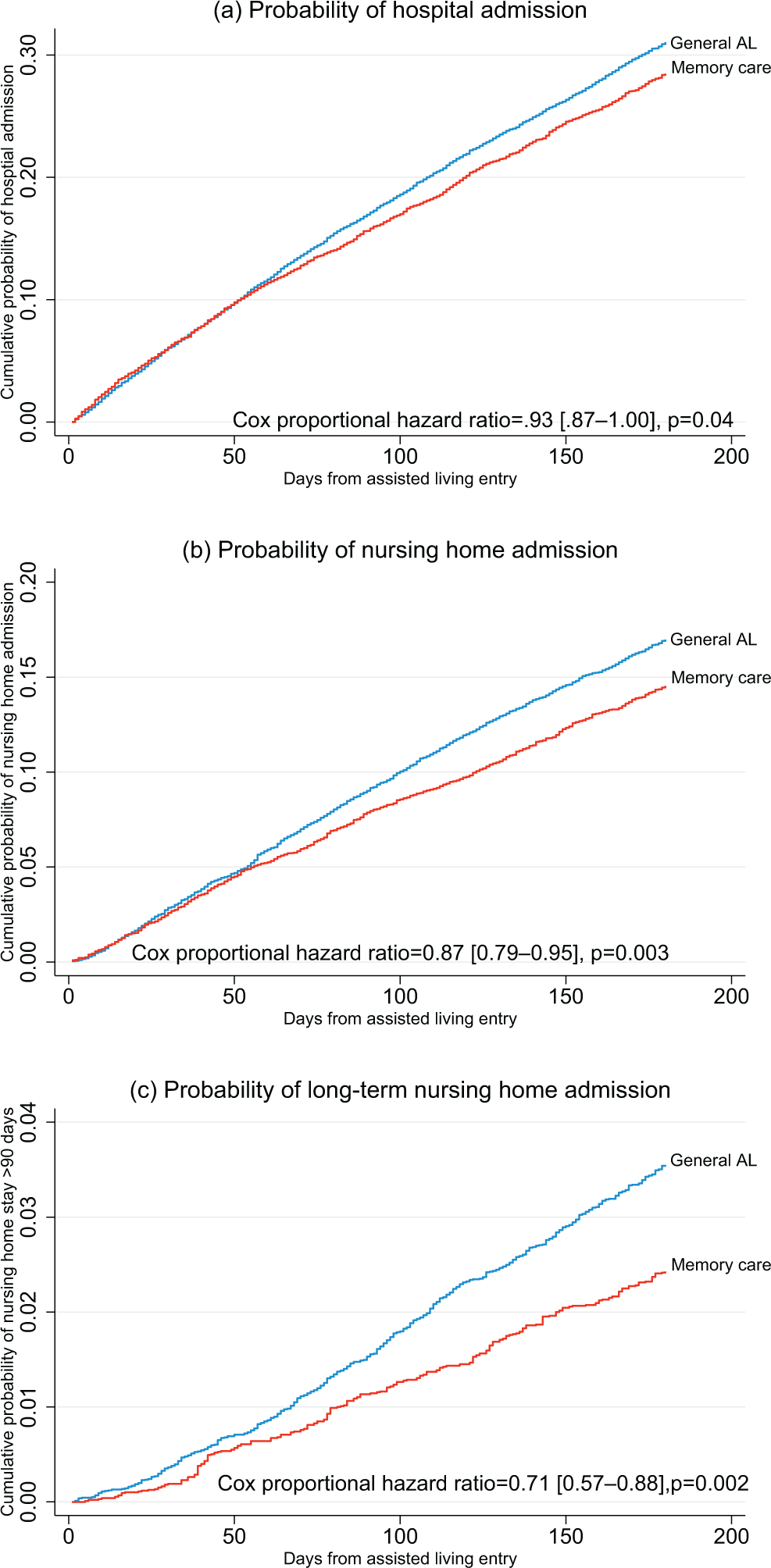

Figure 1 shows plots of the four outcomes, stratified by quintile of the propensity score. From lowest to highest, each quintile represents a higher likelihood of moving to memory care instead of general assisted living, as predicted from a resident’s characteristics and previous neighborhood. Percentage with a hospital admission and mean length of stay were similar between the two groups at each quintile, and both decreased with propensity score. That is, the clinical and demographic characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of memory care were also associated with a lower likelihood of hospital admission and length of stay within each group. For the nursing home admission outcomes (1b and 1c), the average rate of admission was lower in memory care than general care in the upper four quintiles. (There were very few memory-care residents in the lowest quintile, creating a very large confidence interval on this estimate.) The consistency of the difference across quintiles of the propensity score supports the robustness of our main findings. To account for the possibility of differential censoring due to mortality between the two groups, we conducted survival analyses of the time until outcome. Figure 2 shows Kaplan-Meier cumulative hazard curves using inverse-propensity treatment weights. In Cox proportional hazard models, residents in memory care as compared to general assisted living had a lower risk of hospital admission (hazard ratio 0.93 [0.87–1.00]), nursing home admission (hazard ratio 0.87 [0.79–0.95], and long-term nursing home admission (hazard ratio 0.71 [0.57–0.88]).

FIGURE 1.

Stratified outcomes by propensity score. Notes: Risk of outcomes for memory care and general assisted living are shown by quintile of the propensity score. Propensity score calculated using resident demographics, chronic conditions, previous health care use, and characteristics of patients’ previous home county (see Table 1)

FIGURE 2.

FI Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of outcomes. Notes: Kaplan-Meier hazard curves are shown using inverse-propensity treatment weights. Hazard ratios for outcomes are calculated using Cox proportional hazards regressions. Additional detail can be found in the technical appendix

4 |. DISCUSSION

4.1 |. Explanation of findings

After adjusting for clinical acuity, dual Medicare-Medicaid enrollment, and observable socioeconomic characteristics, we found that residents in memory care were less likely to have any hospital or nursing home admission within the first 180 days in assisted living. Most of this difference was driven by the difference in nursing home admissions that exceeded 90 days.

Differences in care processes in memory care that help residents to avoid transfer to a nursing home for care due to progression of ADRD symptoms may explain our results. Providing care to persons with dementia requires higher levels of staffing and supervision, staff training in how to safely address behaviors, and thoughtful design of buildings to accommodate residents who experience disorientation or who are prone to wandering. Staff with more advanced training may be able to safely supervise residents with severe behaviors, or to provide therapies that prevent or reduce behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia. Screening procedures may prompt operators to have sufficient care plans in place, or they may cause some people with advanced ADRD to be denied admission if their symptoms cannot be managed safely by the staff. It is important to note that we found that the differences in nursing home admissions are driven largely by differing risk of admissions that result in long-term (>90 day) stays. That finding is consistent with the explanation that memory-care communities are better equipped to care for ADRD residents, because short-term stays in a nursing home are usually for post-acute, skilled nursing care following a hospital stay, whereas a stay greater than 90 days often signifies long-term residential care.

We estimated slightly lower risk of hospital admission in memory care than general assisted living. It is possible that memory care provides safer, more person-centered care less likely to result in illness or injury requiring hospitalization. Future work could further investigate hospital admissions and emergency department visit use associated with dementia behaviors, such as falls and injuries,20 as well as admissions to psychiatric units.

Unobserved differences in the two populations may also be driving the difference in admission to nursing homes. For instance, we were not able to observe functional status, or progression of a person’s dementia–although if anything we would expect residents in memory care to have more severe symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. General assisted living had a significantly higher proportion of residents dually enrolled in Medicaid. Previous work has found that duals in assisted living are more likely than non-duals to spend some time in a nursing home,21 which may be due to the need to qualify for waiver-based Medicaid waiting lists that prioritize beneficiaries who need a nursing-home level of care. Residents in general assisted living may be less wealthy than residents in memory care, and therefore may be more likely than memory care residents to exhaust their financial resources, necessitating a move to a nursing home under the state’s Medicaid benefit. On the other hand, the high cost of memory care, which can be twice as expensive as general assisted living,22 may deter residents without sufficient wealth from choosing memory care.

The choice of memory care may also reflect stronger preferences to avoid moving to a nursing home. Residents may experience improved quality of life in memory care. If better practices and staff knowledge lead to increased well-being of residents or a perception by families of good-quality care, then families and residents will be inclined to remain in that setting as long as possible.

4.2 |. Implications for policy

People making the choice to purchase memory care are often spouses, children, or people with early stage dementia who plan future care and who do not directly experience the product. Thus the state’s endorsement takes on additional importance as a signal of quality that may be otherwise difficult to observe directly. Key questions for policymakers are two-fold: first, to what degree can additional regulation of memory care influence care processes to protect residents’ safety and improve well-being; and second, whether states should be willing to pay higher rates or subsidies for memory care than for general assisted living.

Several aspects of regulatory requirements for memory care could affect care quality and residents’ health care outcomes, such as cognitive screening upon admission, staffing (eg, training requirements or minimum staff levels or staff-to-resident ratios), and environmental safety.5,7 Pre-admission screening allows for a plan to provide appropriate dementia care. Ten states (six in our sample) require memory care settings, but not general assisted living, to conduct cognitive screening at admission.7 In 2018, a total of 20 states (10 included in our analyses) required direct-care workers or administrators of memory care facilities to receive training for dementia care, but not administrators of general assisted living. Training curricula might include topics such as the effects of medication on persons with dementia, nonpharmacological alternatives to address behaviors, behavior management techniques, and maintaining safety.23 Environmental-safety regulations specific to memory care, which were present in 17 of the states in our sample, may result in safer or more calming physical spaces.

It is important to recognize the limits of regulation to achieve quality goals. To be competitive, operators of assisted living might invest in staff, training, and physical space regardless of the presence of regulations. Regulations may follow after markets have already been differentiated: operators that have invested in a higher level of care may lobby for regulation as a way to establish a “brand,” or create a barrier to entry for competitors. Furthermore, to effect change in care, regulatory stringency relies on the approaches by state agents to monitoring and enforcement, which additionally vary across states.

Much attention has been paid to whether state subsidies for assisted living can be offset by reduced nursing home costs.24–27 In an increasing number of states that pay for assisted living through Medicaid waivers, Medicaid state plans, or supplements for room and board, state agents must decide whether to pay higher rates for memory care.17 For example, Oregon reimburses assisted living at $1439 for the lowest level of care and $3382 for the highest level, whereas memory care operators receive a flat rate of $4704 per month.28 In contrast, NewYork’s Medicaid state plan funds the Assisted Living Program, a managed care program that does not offer the special needs residential care that is certified to provide memory care in New York. Given our finding of reduced nursing home admission from memory care, public payers might be willing to pay a premium for memory care to prevent downstream costs of nursing home care.

4.3 |. Limitations

Limitations to inference from our data and analyses are important to note. In some states, a memory-care designation can apply only to a wing or unit within a facility. Because we linked Medicare beneficiaries to settings based on their ZIP codes, it is possible that some persons that we identify as residing in memory care in fact lived in a wing or unit of the assisted living not designated for memory care, which would tend to bias our findings toward the null. In addition, because we relied on Medicare data, the income and wealth of people in our sample, as well the progression of their ADRD, were unmeasurable for us. In general, in assisted living we observed higher levels of clinical need in the form of chronic conditions and previous health-care use, and unobserved clinical characteristics may have influenced the need for 24-hour skilled nursing care.

There are also limits to the generalizability of our findings. Because the ZIP-code methodology that we used to identify assisted-living residents has been validated only for large (25+ bed) communities, our findings may not apply to smaller communities. We should also be cautious in extrapolating to residents enrolled in Medicare Advantage, or to the states that have memory care licenses but where we were not able to obtain lists of assisted-living communities that had the licenses. Differences in outcomes that we measured can be attributed only to within-state differences between memory care and standard assisted living. Differences among states in their regulatory approaches to memory care, as well as the effects of dementia care regulation that are applied in both types of settings, are outside the scope of this analysis, although they raise important questions for future study.

4.4 |. Conclusions

The present study is the first analysis with national scope to examine residents’ outcomes in general assisted living in comparison to assisted living licensed for memory care. We found that people with ADRD who entered memory-care assisted living were at lower risk of being admitted to a nursing home and less likely to be admitted for the long term, compared to people who entered a general assisted living. The difference may be due to the processes of care within these settings, and our findings support the notion that memory-care communities are better able to cope with behaviors associated with dementia and support the well-being of their residents.

Supplementary Material

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of residents who move to assisted-living facilities with and without memory-care designation

| General assisted living |

Memory care |

Standardized differences(a) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 12523 | 8123 | Raw | Weighted | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 82.1 (10.1) | 84.1 (8.1) | 0.19 | 0.05 | |

| Age category | <65 | 780 (6.2%) | 198 (2.4%) | −0.12 | −0.02 |

| 65 to 74 | 1584 (12.6%) | 716 (8.8%) | 0.04 | 0.01 | |

| 75 to 84 | 3990 (31.9%) | 2742 (33.8%) | 0.1 | 0.01 | |

| 85 to 94 | 5533 (44.2%) | 4022 (49.5%) | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| 95+ | 636 (5.1%) | 445 (5.5%) | |||

| Female | 8144 (65.0%) | 5450 (67.1%) | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| Race | Non-Hispanic White | 11481 (91.7%) | 7776 (95.7%) | ||

| Black | 569 (4.5%) | 172 (2.1%) | −0.13 | −0.02 | |

| Other race | 206 (1.6%) | 80 (1.0%) | −0.05 | −0.01 | |

| Hispanic | 267 (2.1%) | 95 (1.2%) | −0.07 | 0 | |

| Dual eligible | 3255 (26.0%) | 1000 (12.3%) | −0.35 | −0.04 | |

| Retiree drug subsidy | 956 (7.6%) | 707 (8.7%) | 0.04 | −0.01 | |

| Years since ADRD diagnosis, mean (SD)(b) | 3.5 (3.7) | 3.4 (3.6) | −0.02 | −0.02 | |

| Cancer | 2631 (21.0%) | 1829 (22.5%) | 0.04 | 0 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3557 (28.4%) | 2376 (29.3%) | 0.02 | −0.01 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 5908 (47.2%) | 3626 (44.6%) | −0.05 | 0.01 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5726 (45.7%) | 3655 (45.0%) | −0.01 | 0.01 | |

| COPD | 5073 (40.5%) | 2991 (36.8%) | −0.08 | −0.01 | |

| Diabetes | 5430 (43.4%) | 3126 (38.5%) | −0.09 | 0.02 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 8370 (66.8%) | 5322 (65.5%) | −0.02 | 0 | |

| Osteoporosis | 4992 (39.9%) | 3376 (41.6%) | 0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Stroke | 4262 (34.0%) | 2790 (34.3%) | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Number chronic conditions, mean (SD) | 3.7 (2.0) | 3.6 (2.0) | −0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Anxiety | 5674 (45.3%) | 3441 (42.4%) | −0.03 | 0.01 | |

| Bipolar disorder | 1653 (13.2%) | 656 (8.1%) | −0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Obesity | 2519 (20.1%) | 1439 (17.7%) | −0.06 | −0.02 | |

| Schizophrenia | 967 (7.7%) | 212 (2.6%) | −0.16 | −0.04 | |

| Prior outpatient ED/OBS | 6774 (54.1%) | 4331 (53.3%) | −0.06 | 0 | |

| Prior inpatient hospitalization | 6025 (48.1%) | 3760 (46.3%) | −0.22 | −0.04 | |

| Prior ICU | 1581 (12.6%) | 999 (12.3%) | −0.02 | 0 | |

| Prior SNF and/or nursing home use | 4146 (33.1%) | 2427 (29.9%) | −0.04 | −0.01 | |

| Prior home health use | 4731 (37.8%) | 3354 (41.3%) | −0.01 | 0 | |

| Characteristics of county of previous residence, mean (SD) | |||||

| College education or higher | 30.5 (10.9) | 31.7 (10.9) | −0.06 | −0.03 | |

| Unemployment rate | 4.2 (1.0) | 3.9 (0.9) | 0.07 | 0.01 | |

| Percent persons in poverty | 13.4 (4.9) | 13.1 (4.7) | −0.08 | 0.05 | |

| Median home value (thousands) | 220 (137) | 200 (111) | −0.15 | −0.09 | |

| Rurality index (1–9) | 2.4 (1.9) | 2.2 (1.8) | −0.13 | 0.1 | |

| Number of home health agencies(c) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.24 | 0.02 | |

| Certified nursing beds(c) | 0.7 (4.1) | 0.7 (4.0) | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| Distance to nearest general AL | 5.3 (8.6) | 5.6 (7.9) | 0.01 | 0.06 | |

| Distance to nearest memory care AL | 11.2 (15.9) | 6.8 (11.4) | −0.32 | 0.23 | |

AL, assisted living; SD, standard deviation; ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias; ED, emergency department; OBS, hospital observational stay; ICU, intensive care unit; NH, nursing home; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Sample composed of traditional Medicare beneficiaries with a diagnosis of ADRD who moved to a large (≥25 bed) assisted-living community. Total number of communities included 3183 general assisted living and 1677 memory care.

Standardized difference is difference in means divided by pooled standard deviation, or for percentages, Cohen’s .

Any diagnosis of ADRD since Medicare enrollment or since 1999.

Per 1000 persons age 65 and over.

From home health agency or organization.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional bibliographic aids (eg, PubMed and Google Scholar), as well as meeting abstracts and presentations. We did not identify any previous multistate studies that used Medicare data to compare the nursing-home and hospital admissions of residents in memory-care assisted living to those in general assisted living.

Interpretation: Persons with dementia who move to a memory-care community are at a lower risk of admission to a hospital or nursing home in the first 6 months than persons with similar clinical acuity who move to general assisted living.

Future directions: The findings suggest that we should examine the mechanisms that produce differences in residents’ outcomes between the two types of assisted living. Important next steps include (1) examining the variation within and across states in regulations related to staffing requirements, together with their association with reduced nursing-home admission; (2) understanding how processes of care differ between the two settings; and (3) investigating the differences among memory-care residences on dementia-related causes of hospital admission or emergency department use, such as injuries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Joan Brazier for research and data support and Cassandra Hua, PhD and Brian Kaskie, PhD for comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (grant numbers R01AG057746 and P30AG043073).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to report.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris-Kojetin LD, Sengupta M, Lendon JP, Rome V, Valverde R, Caffrey C. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States, 2015–2016. Vital Health Stat. 2019;3(43). Feb. DHHS Publication No. 2019–1427, p. 18, Fig. 19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas KS, Zhang W, Cornell PY, Smith L, Kaskie B, Carder PC. State variability in the prevalence and healthcare utilization of assisted living residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(7):1504–1511. Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Reed D. Dementia prevalence and care in assisted living. Health Aff. 2014;33(4):658–666. Apr 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carder PC. State regulatory approaches for dementia care in residential care and assisted living. Gerontologist. 2017;57(4):776–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaskie BP, Nattinger M, Potter A. Policies to protect persons with dementia in assisted living: déjà vu all over again. Gerontologist. 2015;55(2):199–209. Apr 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carder PC, O’Keefe J, Okeefe C, Compendium of Residential Care and Assisted Living Regulations and Policy: 2015 edition: ASPE, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/compendium-residential-care-and-assisted-living-regulations-and-policy-2015-edition [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith L, Carder P, Bucy T, et al. Connecting policy to licensed assisted living communities, introducing health services regulatory analysis. Health Serv Res. 10.1111/1475-6773.13616. Published online January 10, 2021:1475–6773.13616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joyce NR, McGuire TG, Bartels SJ, Mitchell SL, Grabowski DC. The impact of dementia special care units on quality of care: an instrumental variables analysis. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3657–3679. Oct. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Williams CS, et al. Dementia care and quality of life in assisted living and nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2005;45(suppl_1):133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kopetz S, Steele CD, Brandt J, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of dementia residents in an assisted living facility. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(7):586–593. Jul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samus QM, Mayer L, Baker A, et al. Characteristics and outcomes for assisted living residents with dementia: comparing dementia-specific care units with non-dementia-specific care units. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1361. Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black K, Dobbs D, Young TL. Aging in community: mobilizing a new paradigm of older adults as a core social resource. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;34(2):219–243. Mar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Featherstone K, Northcott A, Harden J, et al. Refusal and resistance to careby people living with dementiabeing cared for within acute hospital wards: an ethnographic study. Health Serv Delivery Res. 2019;7(11). Mar 31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross AL, Jones RN, Habtemariam DA, et al. Delirium and long-term cognitive trajectory among persons with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1324–1331. Sep 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Gozalo PL, et al. A methodology to identify a cohort of Medicare beneficiaries residing in large assisted living facilities using administrative data. Med Care. 2018;56(2):e10. Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee BK, Lessler J, Stuart EA. Weight trimming and propensity score weighting. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e18174. Mar 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Causal inference in statistics, social, and biomedical sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. Apr 6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAS Institute Inc 2013. SAS/ACCESS® 9.4 Interface to ADABAS: Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 19.StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Doorn C, Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, et al. Epidemiology of Dementia in Nursing Homes Research Group. Dementia as a risk factor for falls and fall injuries among nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(9):1213–1218. Sep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fabius CD, Cornell PY, Zhang W, Thomas KS. State Medicaid Financing and Access to Large Assisted Living Settings for Medicare–Medicaid Dual-Eligibles. Med Care Res Rev. 2021:1077558720987666. Jan 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crouch M, “Memory Care: Specialized Support for People With Alzheimer’s or Dementia.” AARP. https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/basics/info-2019/memory-care-alzheimers-dementia.html

- 23.Burke G, Orlowski G. Training to serve people with dementia: Is our health care system ready? Part 2: A review of dementia training standards across health care settings. Washington, DC: Justice in Aging; 2015. August. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grabowski DC, Stevenson DG, Cornell PY. Assisted living expansion and the market for nursing home care. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2296. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cornell PY, Zhang W, Thomas KS. Changes in long-term care markets: assisted living supply and the prevalence of low-care residents in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(8):1161–1165. Aug 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai X, Temkin-Greener H. Nursing home admissions among Medicaid HCBS enrollees. Med Care. 2015;53(7):566–573. Jul 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kane RL, Lum TY, Kane RA, Homyak P, Parashuram S, Wysocki A. Does home-and community-based care affect nursing home use. J Aging Soc Policy. 2013;25(2):146–160. Apr 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comparison of Long-Term Care Facilities in Oregon, 2019. Oregon Department of Human Services. https://www.oregon.gov/dhs/SENIORS-DISABILITIES/Documents/2019-Facility-Comparison-Table.pdf [Accessed February 2, 2021]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.