Abstract

The development of Rhizophora mangle and Avicennia schaueriana seedlings impacted by marine diesel oil (MDO) was evaluated in the presence or absence of a hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium (HBC). The bioassays were conducted in a greenhouse during 6 months and consisted of three different treatments (control, MDO only and MDO + HBC). The bacterial consortium was mainly composed of Bacillus spp. (73%), but Rhizobium spp., Pseudomonas spp., Ochrobactrum spp., and Brevundimonas spp. were also present. After 6 months, A. schaueriana seedlings showed higher mortality compared to those of R. mangle; R. mangle exhibited 68% (control), 44% (MDO alone) and 50% (MDO + HBC) seedlings survivorship compared to 42% (control), 0% (MDO alone) and 4% (MDO + HBC) for A. schaueriana. This variability may be due to differences in species physiology. Stem growth, diameter and number of leaves remained constant during the 6 months of the experiment with marine diesel oil and hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium (MDO + BBC). For both mangrove species, bacterial enzymatic activity in the sediments was sufficient to maintain cell counts of 107 cells cm−3 in the rhizospheric soil and possibly synthetize the extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that may emulsify and solubilize oil products.

Keywords: Bioremediation, Esterase enzyme, Dehydrogenase enzyme, Biofilm, Rhizospheric soil

Introduction

Mangrove forests are an essential intertidal ecosystem throughout tropical and subtropical coastlines (Hoff 2002). These ecosystems are considered nurseries of endangered species and could help mitigate global warming due to their potential capacity to sequester and store carbon, estimated at 5.6 million ha (Howard et al. 2017; Arulnayagam and Park 2019). Periodically flooded by tidal water, this ecosystem exhibits high biodiversity and productivity, but often is polluted by human activities (Tam and Wong 1998; Guzzella et al. 2005; Cheng et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014; Li et al. 2019), particularly oil pollution.

Among organic pollutants, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a lethal contaminant ubiquitously present in coastal areas (Zuloaga et al. 2009; Song et al. 2012; Muratova et al. 2014). PAHs in the environment are of great concern because floating oils washed onto mangroves are challenging to remove from fine sediments and remain stranded on aerial roots, stems and leaves after the tides ebb, leading to choking (IARC 1983; Getter et al. 1985; Duke et al. 1998).

Some studies have been carried out to evaluate the effects of oil spills on the structure and survival of mangrove plants (Rodrigues et al. 1999; Moreira et al. 2011; Camargo et al. 2013). In elsewhere published data (Touchette et al. 1992; Duke 2016), seedling germination was highly susceptible to oil exposure, representing more than 96% of deaths in Avicennia marina seedlings controls (Grant et al. 1993).

Bioremediation is an eco-friendly process promoted by bacterial biofilms associated with the roots of plants and sediments (Luan et al. 2006; Tam and Wong 2008). Biofilms have been defined aggregates of microorganisms in which cells are frequently embedded in a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that adhere to each other and/or to a surface (Vert et al. 2012). A multilaminar environment is created within such biofilms where different microorganisms interact socially, physically and chemically via quorum sensing (Platt and Fuqua 2010; Mangwani et al. 2015). This communication exploits the genetic diversity and metabolic versatility of biofilms, which are integrated into the biogeochemical cycle of essential elements (Mürer et al. 1975; Druschel and Kappler 2015).

Mangrove species are differentially susceptible to damage from large oil spills (Santos et al. 2011; Lewis et al. 2011; Hensel et al. 2014). Given the importance of the recovery of mangrove areas, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of marine diesel oil (MDO) on the seedling development of Rhizophora mangle and Avicennia schaueriana in the presence/absence of a hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium (HBC).

Material and methods

Experimental set-up

Newly sprouted propagules of R. mangle and A. schaueriana were harvested from oil-impacted mangrove swamps in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (7.486.196 S, 684.985 W). Planting took place in individual perforated plastic bags (30 cm × 18 cm) containing 0.8 kg of fresh mangrove sediment. For the viviparous species R. mangle, one-third of each propagule's length was vertically inserted into the sediments, and the remainder (the apical growing tip) was left exposed. For the non-viviparous A. schaueriana, the small-sized propagules were placed a few millimeters below the surface sediment (Zhang et al. 2007). At the beginning of the bioassays, the propagules were cultivated in a greenhouse near the mangrove where sediments had been collected, and where they were watered with fresh water twice a day to maintain the soil moisture content.

The experiment started after propagules germination and had sprouted two pairs of leaves. After that, all individuals have been considerate seedlings. So, seedling in the plastic bags (50 replicates per treatment and mangrove species) were subjected to 3 different treatments as follows: (1) no treatment (Control); (2) seedlings were exposed to marine diesel oil alone (MDO); and (3) seedlings were exposed to marine diesel oil and hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium (MDO + HBC). The MDO treatment consisted of adding 3% MDO (mL g−1 of wet sediment) into the rhizosphere (Chequer et al. 2017). The MDO + HBC treatment involved adding 3% MDO (mL g−1 of wet sediment) plus 107 cells of a hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium (see below) into the rhizosphere soil. The MDO was added only once at the beginning of the experiments. To ensure MDO percolation into the rhizosphere soil, we pushed the same number of holes into the sediments of the MDO and MDO + HBC treatments. After 1 week and ensuring that MDO had fully reached the root system, the HBC was applied once per month for 6 months in the MDO + HBC treatment.

The MDO used in our bioassays was a distillate of marine diesel, which has a low cetane index, a high density and a sulfur content of between approximately 0.3 and 2.0 m/m% (EPA 1999).

Bioassays were conducted over 6 months, with four different sampling times, i.e., at the beginning of the bioassay (T0) and every 2 months thereafter (T2, T4, T6). Seedling’s parameters such as survival (%), stem growth (cm), diameter (mm), and the number of leaves produced were evaluated (150 seedlings per mangrove species). Stem growth and diameter were measured with a digital caliper. The leaves were counted as such only after they had emerged from the leaf primordia and were completely unfolded. Seedlings were scored as dead only if they displayed extensive discoloration and had become shriveled (Proffitt et al. 1995; Zhang et al. 2007).

Isolation and taxonomic identification of the hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium (HBC)

Samples of sediment were collected in the Suruí Mangrove, Guanabara Bay, RJ—Brazil (7.489.800 S; 694.280 W), an area impacted by MDO (Fontana et al. 2010). The samples were stored in sealed polythene bags placed in a cooler box with ice (4 °C) without direct contact during transport to the laboratory (NJDEP 2005) to reduce microbial metabolism and prevent the loss of species or predation (NJDEP 2005; Fenchel et al. 2012).

Sediment samples (1 g) were inoculated in a sterile liquid medium consisting of 9 ml filtered seawater (0.45 μm pore), urea (5 g/L), starch (1 g/L), and MDO (2 ml/L) in Erlenmeyer flasks and then incubated for 15 days at room temperature. Aliquots of the liquid medium were then spread on solid Congo agar (0.08%) and incubated for 15 days at room temperature to select hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria. The resulting reddish-pink colonies were inoculated into a liquid medium with the same protocol described above to attain bacterial biomass of 107 cells and to bioaugment the consortium (Krepsky et al. 2007).

The bacterial consortia were identified by 16S rRNA amplicon using Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (DGGE) technic (Lane 1991). The taxonomy of sequences was retrieved from Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) (Cole et al. 2009). All sequence data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (GenBank) under BioProject ID SUB7449012.

Quantification of bacterial enzymatic activity and cell number in the rhizospheric soil of R. mangle and A. schaueriana

Triplicate sediment samples were taken randomly from each treatment (Control, MDO and MDO + HBC) at the four different sampling times (T0, T2, T4, and T6) and bacterial enzyme activity and bacterial cell number were measured.

We analyzed enzymatic activities of esterases (EST; enzymes that act on biopolymers and transform them into low-molecular-weight organic carbon) and dehydrogenases (DHA; enzymes involved in the electron transport system). EST (µg fluorescein h g−1) was analyzed according to Stubberfield and Shaw (1990), and DHA (mg INT-F g−1) was analyzed using the method described by Houri‐Davignon et al. (1989). The sediment samples were analyzed in triplicate. Bacterial cells (cells cm−3) were enumerated in triplicate via epifluorescence microscopy (Axiosp 1, Zeiss, triple filter Texas Red–DAPI–fluorescein isothiocyanate, 1000× magnification) and using fluorochrome fluorescein diacetate and UV radiation (Kepner and Pratt 1994).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in the R statistical environment (R Development Core Team 2014). After verifying that each dataset was non-normally distributed, we conducted Kruskal–Wallis ANOVAs followed by post hoc Dunnett tests to define significant differences between the control and treatments (MDO and MDO + HBC). A p value of less than 0.05 was deemed to indicate statistical significance (95% significance level).

Results

Seedling’s survival

Over the 6-month bioassay, R. mangle presented a different survivorship pattern than A. schaueriana (Fig. 1). R. mangle seedlings in the control and MDO + HBC treatments had a similar survival pattern, whereas A. schaueriana exhibited high mortality under all treatments. For example, at T6, R. mangle survival rates were 68% (control), 44% (MDO) and 50% (MDO + HBC), whereas A. schaueriana showed 42% (control), 0% (MDO) and 4% (MDO + HBC). Differences in seedling survival between the control and MDO or MDO + HBC treatments were not significant for either species (Kruskal–Wallis, p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Propagule survival of R. mangle and A. schaueriana impacted by marine diesel oil in the absence (MDO) or presence (MDO + HBC) of a hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium

Table 1.

Summary of Dunnett tests on parameters analyzed during the development of R. mangle and A. schaueriana propagules impacted by marine diesel oil in the absence (MDO) and presence (MDO + HBC) of a hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium

| Propagule | Comparison | Survival | Stem growth | Diameter | Number of leaves | EST | DHA | Number of cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. mangle | Control v | MDO | 0.884 | 0.009* | 0.002* | 0.982 | 0.99 | 0.0001* | 0.841 |

| MDO + HBC | 0.818 | 0.006* | 0.35968 | < 0.0001* | 0.951 | 0.905 | 0.788 | ||

| A. shaueriana | Control v | MDO | 0.516 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | 0.007* | 0.99 | 0.001* | 0.221 |

| MDO + HBC | 0.437 | 0.273 | 0.080 | 0.879 | 0.951 | 0.954 | 0.647 | ||

*Significant effects are indicated in bold. EST: Esterase activity; DHA: Dehydrogenase activity

Stem growth and diameter

By the end of the bioassay (T6), stems of R. mangle were longer: 28.5 ± 0.6 cm for the control, 29.3 ± 0.4 cm for the MDO treatment, and 29.9 ± 0.5 cm for MDO + HCB (Fig. 2A). The stem growth average between the control and two treatments was significantly different (Kruskal–Wallis, p = 0.02) for R. mangle. Stem growth of A. schaueriana was also greater in the control (20.6 ± 1.2 cm) and MDO + HBC (21.3 ± 7.8 cm) treatments by the end of the bioassay (note that all A. schaueriana seedlings had died under the MDO only treatment, so this parameter could not be assessed for this treatment). The average growth differences between A. schaueriana control and treatments were significantly different, possibly due to the strong influence of the MDO only treatment (Kruskal–Wallis, p < 0.01). These stem growth results were also reflected in the stem diameter analysis, in which diameter was enhanced in all treatments for R. mangle and in the control and MDO + HCB treatment for A. schaueriana (Kruskal–Wallis, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Stem growth (A), diameter (B) and number of leaves (C) during development of R. mangle and A. schaueriana propagules impacted by marine diesel oil in the absence (MDO) or presence (MDO + HBC) of a hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium

Leaf production

Leaf production by R. mangle was lower than that of A. schaueriana during the bioassay (Fig. 2C). At the beginning T0, R. mangle had 4.2 ± 0.2 leaves in the control, 3.4 ± 0.1 in the MDO treatment and 3.6 ± 0.2 in the MDO + HBC treatment. R. mangle leaf number for the control and MDO treatment was similar by the end of the bioassay (T6), with 3.4 ± 0.2 and 3.1 ± 0.2 leaves, respectively. However, R. mangle leaf production under the MDO + HBC treatment was enhanced by T6 (4.3 ± 0.2; Kruskal–Wallis, p = 0.003). In contrast, the numbers of leaves were reduced under both control and treatments for A. schaueriana. However, by T6, numbers of A. schaueriana leaves were similar between the MDO + HBC (5.5 ± 0.5) and control (5.3 ± 0.8) treatments (not assessed for the MDO treatment because all A. schaueriana seedlings had died). The differences in A. schaueriana leaf numbers between the control and treatments were significantly different (Kruskal–Wallis, p = 0.04).

HBC taxonomy, bacterial enzyme activities, and bacterial cell numbers

The bacterial consortium isolated from mangrove sediments consisted of five bacterial strains: Bacillus spp. (73%), Rhizobium spp. (14%), Pseudomonas spp. (7%), Ochrobactrum spp. and Brevundimonas spp. (Both 3%). Our results suggest that potentially the main source of carbon and energy for these bacteria was MDO.

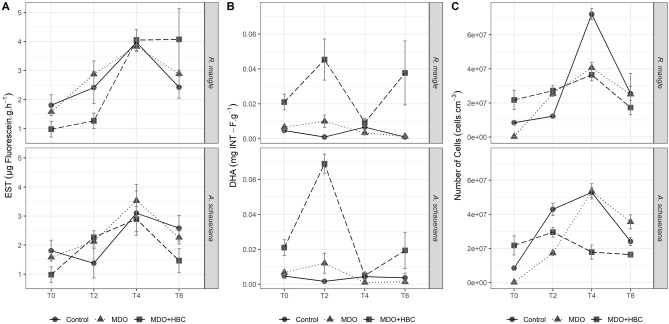

Esterase (EST) activity was similar across control (1.81 ± 0.36 µg fluorescein h g−1), MDO (1.58 ± 0.07 µg fluorescein h g−1), and MDO + HBC (0.98 ± 0.27 µg fluorescein h g−1) treatments at the beginning of the assay. Bacteria in the R. mangle rhizosphere showed the highest EST activities at T4 and T6 under MDO + HBC treatment (Fig. 3A). At T6, R. mangle under control and MDO only treatment exhibited low EST activity (2.43 ± 0.38 and 2.89 ± 0.07 µg fluorescein g h−1, respectively). Similar patterns of EST activity were observed in the rhizospheres of A. schaueriana, with increased activity up to T4 (control = 3.10 ± 0.67, MDO = 3.53 ± 0.56, and MDO + HBC = 2.90 ± 0.43 µg fluorescein g h−1). However, by the end of the bioassay (T6), EST activity for A. schaueriana had decreased (control = 2.58 ± 0.44, MDO = 2.26 ± 0.22, and MDO + HBC = 1.46 ± 0.42 µg fluorescein g h−1). The differences in EST activity between controls and treatments for both R. mangle and A. schaueriana were not significant (Kruskal–Wallis, p > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Esterase enzyme (EST) activity (A), dehydrogenase enzyme (DHA) activity (B) and number of bacterial cells (C) during development of R. mangle and A. schaueriana propagules impacted by marine diesel oil in the absence (MDO) or presence (MDO + HBC) of a hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium

Dehydrogenase (DHA) activity was significantly different between the controls and treatments for both mangrove species (Kruskal–Wallis, p < 0.05), with the highest activity recorded under the MDO + HBC treatment (Fig. 3B). After six months (T6), DHA activity in the rhizospheres of R. mangle was 0.0010 ± 0.000 mg INT-F g−1 for the control, 0.0013 ± 0.0003 mg INT-F g−1 for the MDO treatment, and 0.0377 ± 0.0183 mg INT-F g−1 for the MDO + HBC treatment. DHA activity in the rhizospheres of A. schaueriana control, MDO and MDO + HBC treatments were 0.0037 ± 0.0027, 0.0013 ± 0.0003 and 0.0193 ± 0.0104 mg INT-F g−1, respectively.

Throughout 6-month bioassays, bacterial cell numbers remained close to 107 cells cm−3 in the rhizosphere soils of both R. mangle and A. schaueriana (Fig. 3C). In the rhizospheres of R. mangle at the end of the bioassays, cell numbers were 2.5 × 107 ± 4.1 × 106 cells cm−3 (control), 2.5 × 107 ± 1.2 × 107 cells cm−3 (MDO), and 1.7 × 107 ± 1.4 × 106 cells cm−3 (MDO + HBC). Numbers of bacteria in the rhizospheres of A. schaueriana increased over the bioassay period for the control and MDO only treatment, culminating at T6 in values of 2.4 × 107 ± 2.4 × 106 (control), 3.6 × 107 ± 4.1 × 106 cells cm−3 (MDO), and a decrease to 1.6 × 107 ± 8.4 × 105 cells cm−3 for the MDO + HBC treatment. However, variation in bacterial cell numbers across the bioassay period was not significant (Kruskal–Wallis, p > 0.05).

Discussion

This study examined the influence of marine diesel on the development of the mangrove species R. mangle and A. schaueriana seedlings, which were inoculated by a specialized bacterial consortium in the rhizosphere soil. After 6 months of study, we observed that A. schaueriana exhibited high mortality under the MDO and MDO + HBC treatments. R. mangle appeared to be less affected under the same treatments and for the same duration. According to Getter et al. (1985), responses of mangroves to oil spills vary greatly and this variability may be attributed to the substance-specific response of mangroves for each family or group of oils.

The differential survival observed in the two mangrove species examined in this experiment may be related to natural metabolism, mainly in terms of the control of substance uptake by roots and transpiration of stressor compounds by the leaves. The oil is absorbed by the roots of seedlings and translocated to the leaves, where the volatile fractions are expunged through the stomata and the non-volatile fractions remain in the substomatal vestibules (Getter et al. 1985; Tomlinson 1994). Thus, resistance of R. mangle to marine diesel pollution is possibly due to an ability to prevent oil from being absorbed by the roots, whereas osmoregulation by A. schaueriana directs oil from the roots to the leaves via the vascular system, in a process like how mangroves expunge salt (Getter et al. 1985; Touchette et al. 1992; Tomlinson 1994).

In a study carried out by Proffitt et al. (1995), mangrove plants of the species A. germinans and R. mangle were subjected to acute and chronic doses of fresh lubricating oil at two locations: (1) in an air-conditioned laboratory with diffuse light (controlled environment); and (2) in an outdoor location, directly exposed to sunlight and weather conditions (natural environment). The authors found that A. germinans died under both treatments after a few weeks, whereas for R. mangle survival rates were more influenced by environmental factors than oil exposure. Under natural conditions, the mangrove A. marina was more sensitive to a moderate dose of lubricating oil than A. corniculatum (Ye and Tam 2007). Another study showed that R. mangle was impacted after 16 weeks under controlled conditions by acute and chronic doses of crude oil, but the effects were more pronounced for the acute doses (Chindah et al. 2008). Moradi et al. (2021) observed a reduction in height and number of leaves of A. marina when the plant was subjected to higher oil concentrations in the soil. The authors reported that the root architecture was modified under high oil contamination and suggested that this change makes it difficult for the oil to enter the plant’s vascular system. Naidoo et al. (2010) concluded that A. marina produced adventitious roots at the stem base in sediments impacted by oil and suggested that this response can be used as a biological indicator of oil pollution.

The literature reports that the responses of mangrove plants to oil pollution vary greatly due to differing physiologies, types of oil, and experimental conditions (de Soyza 2002; Lewis et al. 2011). Here, we showed that the effects of an oil spill differ for R. mangle and A. schaueriana seedlings; a finding also reported by Touchette et al. (1992).

Moreira et al. (2011) evaluated the effects of oil and the autochthonous bacteria of the rhizospheric soil on R. mangle growth. The authors did not report mortality rates, but they found that after 3 months, R. mangle exhibited higher growth in the presence of the bacterial community compared to the reference sediment, and the number of bacteria also increased over the experimental period. They suggested that this growth indicates that R. mangle is well adapted to oil pollution. In contrast to our findings, Moreira et al. (2013) reported that after 90 days, the growth of A. schaueriana had increased, as had the number of bacterial cells, and suggested that A. schaueriana is a promising species for bioremediation of mangroves impacted by oil. Sampaio et al. (2019) showed that the combination of Bacillus sp. and R. mangle had a higher rate of oil removal from the sediment than the treatment without bacteria. The authors indicated that the bacterial inoculum induced the propagule germination, increased plant survival, and the bacterial strains demonstrated their potential for phytoremediation purpose. Verâne et al. (2020) compared the efficiency of phytoremediation of PAHs using R. mangle and the natural attenuation of HPA in mangrove sediment impacted by crude oil. In this study, the phytoremediation was more efficient on PAHs degradation after 90 days of the experiment, indicating the positive interaction of rhizospheric and endophytic microbiota.

Here, we showed that bacterial esterase activity in the rhizospheric soil increased up to the end of the study for seedlings of both mangrove species. Elevated hydrolytic enzyme activities were also reported for the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (Arnosti et al. 2016; Ziervogel and Arnosti 2016). We found that bacterial dehydrogenase activity was high only under the MDO + HBC treatment. Being intracellular enzymes, dehydrogenases are often considered good estimators of contamination (Galiulin et al. 2012; Lipińska et al. 2014; Kaczyńska et al. 2015) and as an index of general microbiological activity in the soil (Moeskops et al. 2010). Furthermore, the growth of oil-degrading bacteria contributes to the high dehydrogenase activity (Kucharski and Jastrzȩbska 2005; Wyszkowska and Kucharski 2005) since marine oil is a good source of carbon. However, despite the high hydrolytic and oxidoreductase activities, bacterial cell numbers remained approximately 107 cells cm−3 in the rhizospheric soil in our study. Waite et al. (2020) observed the same patterns on metal bioremediation bioassays, with a similar number of cells in all experiments and high esterase and dehydrogenase activities. The enzymatic variation during the time indicated that the bacteria in the rhizosphere of mangrove plants (R. mangle and A. schaueriana) firstly produced energy with the increase of DHA after 2 months of the bioassays, and then used this energy to increase the number of leaves, which can be observed in T4. After 4 months from the beginning of the experiments, there was an increase of polymer hydrolysis and in the number of bacterial cells. The dehydrogenase activities were higher in the MDO + HBC when compared with MDO bioassay, suggesting that in MDO the autochthonous non-hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria did not use oil as a source of carbon and energy. Enzymatic activities produce cellular energy for the synthesis of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) (Quigg et al. 2016), which have varying functions (Decho and Herndl 1995; Leppard 1997; Verdugo 2012; Decho and Gutierrez 2017). Production of EPS by microbes in response to oil spills promotes attachment and/or may serve to emulsify and solubilize oil products, thereby increasing their bioavailability and biodegradation (Head et al. 2006; Krepsky et al. 2007; McGenity et al. 2012).

Specific microorganisms are very important in petroleum biodegradation, and they are selected during contamination, and appropriate environmental conditions. Various bacterial groups present in mangrove sediments exhibit a capacity to degrade petroleum hydrocarbons (Brito et al. 2006). Maciel-Souza et al. (2006) isolated oil-degrading bacterial strains from Laguncularia racemosa and R. mangle rhizospheres and indicated that, from the 11 most promising isolates obtained, 10 of them belonged to the genus Bacillus and one to Acinetobacter. According to Carmo et al. (2011), oil-degrading bacterial consortia could be an effective tool for the bioremediation of oil-contaminated mangroves. There is evidence that Bacillus spp. can be effective in clearing oil spills (Crapez et al. 1997; Ghazali et al. 2004). Ijah and Antai (2003) reported Bacillus spp. as the predominant isolates of oil-degrading bacteria characterized from highly polluted soil samples (30% and 40% crude oil).

Oil degradation by microorganisms associated with root surfaces and sediments could be important for bioremediation and phytoremediation. Such microorganisms, termed plant-growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), have the potential to promote plant growth and to aid in the recovery of oil-contaminated sites, as well as to improve plant health by the production and secretion of various regulatory chemicals and nutrients (Compant et al. 2010; Glick 2010). They can do this by simultaneously improving soil structure and degrading petroleum hydrocarbons (Yenn et al. 2014). Ochrobactrum spp. and Rhizobium spp. were previously described as a substantial component of soil and rhizosphere microbial communities, acting as nitrogen-fixers and symbionts in the roots and stems of plants (Ngom et al. 2004; Bathe et al. 2006). These nitrogen-fixing syntrophic microorganisms are important to plant in stressful environments (Yang et al. 2009; Jha and Saraf 2015) and for biodegradation of contaminants (McGenity et al. 2012; Chronopoulou et al. 2013). Rhizobium spp. and Pseudomonas spp. produce important regulatory chemicals, such as the plant hormone indole-3-acetic acid, siderophores, and hydrogen cyanide increasing phosphate availability for microbiota and plant hosts (Ahemad and Kibret 2014; Rijavec and Lapanje 2016).

Other bacteria that are also part of the HBC do not contribute to nitrogen or phosphorus availability but degrade PAHs (such as Bacillus spp. (Das and Mukherjee 2007; Fernandes et al. 2016; Yadav et al. 2016)) or aid the oil biodegradation process through EPS production (such as Pseudomonas spp. and Brevundimonas spp. (Das and Mukherjee 2007)). Oil provides a major source of carbon and electrons in an otherwise nutrient-starved marine environment (Tam and Wong 2008; Kostka et al. 2011), contributing to increased bacterial abundance. The variability in plant responses to oil spills and the role of the microbial consortia in oil-contaminated sediments reflect the complexity of this type of pollution, highlighting the need for monitoring and methodological developments (Sodré et al. 2013).

Conclusion

During 6 months of the essay, we observed the main forces driving the survivorship and resistance of R. mangle and A. schaueriana under marine diesel oil pollution, including seedlings survival. R. mangle showed more success in developing in oil impacted soil and possibly could chemically dialog with oil-degrading bacteria. The main predominant bacteria selected in this study were Bacillus spp., followed by Rhizobium spp. and Pseudomonas spp., both effective oil-degrading, diazotrophic and plant-growth promoting bacteria. Selected oil-degrading bacteria consortium colonized impacted sediment in this study and contributed to the emulsification and the solubilization process of oil that eradicated oil’s sensible species (A. schaueriana). However, it possibly helped in the development of resistant species (R. mangle) due to nitrogen fixation and plant promoting compounds. Mangroves are highly vulnerable to oil impact and play important roles in the maintenance of shorelines, as nurseries for several species, and could help in the mitigation of global warming. This work sheds light on how complicated a bioremediation process is in this environment. Pointing that a recovery project deeply requires taking into account the plant metabolism and its interaction with local microbiota.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank CAPES for fellowship grant support to the first author. We also thank Leandro Pereira Coutinho for help in laboratory analysis. This manuscript was greatly improved by the comments of the anonymous reviewers.

Author contributions

The contribution of the authors is described below with their responsibility in the research. With the submission of this manuscript, I would like to undertake that all authors of this research paper have directly participated in the planning, execution, or analyses of this study. JAPB: contributed to the analysis, interpretation of the data and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. CCCW, GOAS, DCP: contributed to the design, conceptualization of the study and laboratory analyses. MCAC: contributed to the analysis, interpretation of the data and revising the manuscript for intellectual content.

Data availability

Accession Number: All taxonomic sequence data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (GenBank) under BioProject ID SUB7449012.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

References

- Ahemad M, Kibret M. Mechanisms and applications of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: current perspective. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2014;26:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2013.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnosti C, Ziervogel K, Yang T, Teske A. Oil-derived marine aggregates—hot spots of polysaccharide degradation by specialized bacterial communities. Deep Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2016;129:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2014.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arulnayagam A, Park J. Blue carbon stock of mangrove ecosystems. Int J Sci Res. 2019;8:1371–1375. doi: 10.21275/ART20203497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bathe S, Achouak W, Hartmann A, et al. Genetic and phenotypic microdiversity of Ochrobactrum spp. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2006;56:272–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito EMS, Guyoneaud RRRRR, Goñi-Urriza M, et al. Characterization of hydrocarbonoclastic bacterial communities from mangrove sediments in Guanabara Bay, Brazil. Res Microbiol. 2006;157:752–762. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo MG, Nardes E, Lana PC. Efeitos de um derrame experimental de óleo bunker na sobrevivência e taxas de crescimento de plântulas de Laguncularia racemosa (Combretaceae) Biotemas. 2013;26:53–67. doi: 10.5007/2175-7925.2013v26n1p53. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo FL, Santos HF, Martins EF, et al. Bacterial structure and characterization of plant growth promoting and oil degrading bacteria from the rhizospheres of mangrove plants. J Microbiol. 2011;49:535–543. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-0528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Wang Y-S, Ye Z-H, et al. Influence of N deficiency and salinity on metal (Pb, Zn and Cu) accumulation and tolerance by Rhizophora stylosa in relation to root anatomy and permeability. Environ Pollut. 2012;164:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chequer L, Bitencourt J, Waite C, et al. Response of mangrove propagules to the presence of oil and hydrocarbon degrading bacteria during an experimental oil spill. Lat Am J Aquat Res. 2017;45:814–821. doi: 10.3856/vol45-issue4-fulltext-17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chindah AC, Braide SA, Amakiri JO, Onokurhefe J. Effect of crude oil on the development of white mangrove seedlings (Avicennia germinans) in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Estud Biol. 2008;30:181–194. doi: 10.7213/reb.v30i70/72.22810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chronopoulou PM, Fahy A, Coulon F, et al. Impact of a simulated oil spill on benthic phototrophs and nitrogen-fixing bacteria in mudflat mesocosms. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:242–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D141–D145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compant S, Clément C, Sessitsch A. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in the rhizo- and endosphere of plants: their role, colonization, mechanisms involved and prospects for utilization. Soil Biol Biochem. 2010;42:669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crapez MAC, Tosta ZT, Bispo MGS, et al. Biorremediação em sedimentos de praias arenosas utilizando Bacillus isolados de solo de floresta. Oecologia Bras. 1997;03:19–26. doi: 10.4257/oeco.1997.0301.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das K, Mukherjee AK. Crude petroleum-oil biodegradation efficiency of Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from a petroleum-oil contaminated soil from North-East India. Bioresour Technol. 2007;98:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Soyza AG. Development of quantitative tools for improved environmental decision-making in arid environments. Environmetrics. 2002;13:523–533. doi: 10.1002/env.528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decho AW, Gutierrez T. Microbial extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) in ocean systems. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–28. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decho AW, Herndl GJ. Microbial activities and the transformation of organic-matter within mucilaginous material. Sci Total Environ. 1995;165:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(95)04541-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Druschel GK, Kappler A. Geomicrobiology and microbial geochemistry. Elements. 2015;11:389–394. doi: 10.1002/2014EO100008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duke NC. Oil spill impacts on mangroves: recommendations for operational planning and action based on a global review. Mar Pollut Bull. 2016;109:700–715. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke NC, Ellison JC, Burns KA. Surveys of oil spill incidents affecting mangrove habitat in Australia: a preliminary assessment of incidents, impacts on mangroves, and recovery of deforested areas. APPEA J. 1998;38:646. doi: 10.1071/AJ97041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EPA (1999) In-Use Marine Diesel Fuel (EPA420-R-99-027). Fairfax, Virgínia

- Fenchel T, King GM, Blackburn H. Bacterial biochemistry: the ecophysiology of mineral cycling. 3. San Diego: Academic Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes PL, Rodrigues EM, Paiva FR, et al. Biosurfactant, solvents and polymer production by Bacillus subtilis RI4914 and their application for enhanced oil recovery. Fuel. 2016;180:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.04.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana LF, Da SFS, De FNG, et al. Superficial distribution of aromatic compounds and geomicrobiology of sediments from Suruí Mangrove, Guanabara Bay, RJ, Brazil. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2010;82:1013–1030. doi: 10.1590/S0001-37652010000400022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiulin RV, Bashkin VN, Galiulina RA. Degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons in soil under the action of peat compost. Solid Fuel Chem. 2012;46:328–329. doi: 10.3103/S0361521912050047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Getter CDC, Ballou TGT, Koons CB, Bruce Koons C. Effects of dispersed oil on mangroves synthesis of a seven-year study. Mar Pollut Bull. 1985;16:318–324. doi: 10.1016/0025-326X(85)90447-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazali FM, Rahman RNZA, Salleh AB, Basri M. Biodegradation of hydrocarbons in soil by microbial consortium. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2004;54:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2004.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glick BR. Using soil bacteria to facilitate phytoremediation. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant DL, Clarke PJ, Allaway WG. The response of grey mangrove (Avicennia marina (Forsk.) Vierh.) seedlings to spills of crude oil. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol. 1993;171:273–295. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(93)90009-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzella L, Roscioli C, Viganò L, et al. Evaluation of the concentration of HCH, DDT, HCB, PCB and PAH in the sediments along the lower stretch of Hugli estuary, West Bengal, northeast India. Environ Int. 2005;31:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head IM, Jones DM, Röling WFM. Marine microorganisms make a meal of oil. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel P, Proffitt EC, Delgado P, et al. Mangrove Ecology. In: Hoff R, Michel J, et al., editors. Oil spills in mangroves: planning & response considerations. USA: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2014. p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff R (2002) Oil spills in mangroves: planning & response considerations. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA Ocean Service, Office of Response and Restoration

- Houri-Davignon C, Relexans JC, Etcheber H. Measurement of actual electron transport system (ETS) activity in marine sediments by incubation with INT. Environ Technol Lett. 1989;10:91–100. doi: 10.1080/09593338909384722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Sutton-Grier A, Herr D, et al. Clarifying the role of coastal and marine systems in climate mitigation. Front Ecol Environ. 2017 doi: 10.1002/fee.1451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IARC Polynuclear aromatic compounds, Part 1, chemical, environmental and experimental data. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risk Chem Hum. 1983;32:1–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijah UJ, Antai S. Removal of Nigerian light crude oil in soil over a 12-month period. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2003;51:93–99. doi: 10.1016/S0964-8305(01)00131-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jha CK, Saraf M. Plant growth promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR): a review. J Agric Res Dev. 2015;5:108–119. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.5171.2164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczyńska G, Borowik A, Wyszkowska J. Soil dehydrogenases as an indicator of contamination of the environment with petroleum products. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11270-015-2642-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepner RL, Pratt JR. Use of fluorochromes for direct enumeration of total bacteria in environmental samples: past and present. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:603–615. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.603-615.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostka JE, Prakash O, Overholt WA, et al. Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria and the bacterial community response in gulf of mexico beach sands impacted by the deepwater horizon oil spill. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:7962–7974. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05402-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krepsky N, Da Silva F, Fontana L, Crapez M. Alternative methodology for isolation of biosurfactant-producing bacteria. Braz J Biol. 2007;67:117–124. doi: 10.1590/S1519-69842007000100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharski J, Jastrzȩbska E. Effects of heating oil on the count of microorganisms and physico-chemical properties of soil. Polish J Environ Stud. 2005;14:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lane DJ. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester: Wiley; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- Leppard GG. Colloidal organic fibrils of acid polysaccharides in surface waters: electron-optical characteristics, activities and chemical estimates of abundance. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem Eng Asp. 1997;120:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0927-7757(96)03676-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Pryor R, Wilking L. Fate and effects of anthropogenic chemicals in mangrove ecosystems: a review. Environ Pollut. 2011;159:2328–2346. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zheng L, Zhang Y, et al. Comparative metagenomics study reveals pollution induced changes of microbial genes in mangrove sediments. Nature. 2019;9:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42260-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipińska A, Kucharski J, Wyszkowska J. The effect of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on the structure of organotrophic bacteria and dehydrogenase activity in soil. Polycycl Aromat Compd. 2014;34:35–53. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2013.844175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luan TG, Yu KSH, Zhong Y, et al. Study of metabolites from the degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) by bacterial consortium enriched from mangrove sediments. Chemosphere. 2006;65:2289–2296. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel-Souza MC, Macrae A, Volpon AGT, et al. Chemical and microbiological characterization of mangrove sediments after a large oil-spill in Guanabara Bay––RJ—Brazil. Braz J Microbiol. 2006;37:262–266. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822006000300013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mangwani N, Kumari S, Das S. Involvement of quorum sensing genes in biofilm development and degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by a marine bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa N6P6. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:10283–10297. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6868-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGenity TJ, Folwell BD, McKew BA, Sanni GO. Marine crude-oil biodegradation: a central role for interspecies interactions. Aquat Biosyst. 2012;8:10. doi: 10.1186/2046-9063-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeskops B, Sukristiyonubowo BD, et al. Soil microbial communities and activities under intensive organic and conventional vegetable farming in West Java, Indonesia. Appl Soil Ecol. 2010;45:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2010.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Zare Maivan H, Seyed Hashtroudi M, et al. Physiological responses and phytoremediation capability of Avicennia marina to oil contamination. Acta Physiol Plant. 2021;43:18. doi: 10.1007/s11738-020-03177-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira ITA, Oliveira OMC, Triguis JA, et al. Phytoremediation using Rizophora mangle L. in mangrove sediments contaminated by persistent total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH’s) Microchem J. 2011;99:376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2011.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira ITA, Oliveira OMC, Triguis JA, et al. Phytoremediation in mangrove sediments impacted by persistent total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH’s) using Avicennia schaueriana. Mar Pollut Bull. 2013;67:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratova A, Pozdnyakova N, Makarov O, et al. Degradation of phenanthrene by the rhizobacterium Ensifer meliloti. Biodegradation. 2014;25:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s10532-014-9699-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mürer EH, Levin J, Holme R. Isolation and studies of the granules of the amebocytes of Limulus polyphemus, the horseshoe crab. J Cell Physiol. 1975;86:533–542. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040860310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo G, Naidoo Y, Achar P. Responses of the mangroves Avicennia marina and Bruguiera gymnorrhiza to oil contamination. Flora Morphol Distrib Funct Ecol Plants. 2010;205:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2009.12.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ngom A, Nakagawa Y, Sawada H, et al. A novel symbiotic nitrogen-fixing member of the Ochrobactrum clade isolated from root nodules of Acacia mangium. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2004;50:17–27. doi: 10.2323/jgam.50.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NJDEP . Field sampling procedures manual. New Jersey: NJDEP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Platt TG, Fuqua C. What’s in a name? The semantics of quorum sensing. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt CE, Devlin DJ, Lindseyt M. Effects of oil on mangrove seedlings grown under different environmental conditions. Mar Pollut Bull. 1995;30:788–793. doi: 10.1016/0025-326X(95)00070-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quigg A, Passow U, Chin W-C, et al. The role of microbial exopolymers in determining the fate of oil and chemical dispersants in the ocean. Limnol Oceanogr Lett. 2016;1:3–26. doi: 10.1002/lol2.10030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2014) R: a language and environment for statistical computing.

- Rijavec T, Lapanje A. Hydrogen cyanide in the rhizosphere: not suppressing plant pathogens, but rather regulating availability of phosphate. Front Microbiol. 2016 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues FDO, Lamparelli CC, De MDO. Environmental impact in mangrove ecosystems: São Paulo, Brazil. In: Arancibia AY, Lara-Domínguez AL, editors. Ecosistemas de manglar en américa tropical. Costa Rica: Silver Spring; 1999. p. 380. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio CJS, de Souza JRB, Damião AO, et al. Biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a diesel oil-contaminated mangrove by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1686-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos HF, Carmo FLFL, Paes JES, et al. Bioremediation of mangroves impacted by petroleum. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011;216:329–350. doi: 10.1007/s11270-010-0536-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sodré V, Caetano VS, Rocha RM, et al. Physiological aspects of mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa) grown in microcosms with oil-degrading bacteria and oil contaminated sediment. Environ Pollut. 2013;172:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M-K, Song M, Choi H-S, et al. Identification of molecular signatures predicting the carcinogenicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) Toxicol Lett. 2012;212:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubberfield LCF, Shaw PJA. A comparison of tetrazolium reduction and FDA hydrolysis with other measures of microbial activity. J Microbiol Methods. 1990;12:151–162. doi: 10.1016/0167-7012(90)90026-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tam NFY, Wong YS. Variations of soil nutrient and organic matter content in a subtropical mangrove ecosystem. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1998;103:245–261. doi: 10.1023/A:1004925700931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tam NFY, Wong YS. Effectiveness of bacterial inoculum and mangrove plants on remediation of sediment contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Mar Pollut Bull. 2008;57:716–726. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson PB. The botany of mangroves. 1. Australia: University of Cambridge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Touchette BW, Baca BJ, Stout DC (1992) Effects of an oil spill in a mangrove mitigation site. In: Ann. Conf. on Wetlands Restoration and Creation. 18th Ann. Conf. on Wetlands Restoration and Creation, Tampa, Fla., Tampa, Fla, pp 213–227

- Verâne J, Santos NCP, Silva VL, et al. Phytoremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in mangrove sediments using Rhizophora mangle. Mar Pollut Bull. 2020;160:111687. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo P. Marine microgels. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2012;4:375–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert M, Doi Y, Hellwich K, et al. Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012) Pure Appl Chem. 2012;84:377–410. doi: 10.1351/PAC-REC-10-12-04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waite CCC, Silva GOA, Bitencourt JAP, et al. Potential application of Pseudomonas stutzeri W228 for removal of copper and lead from marine environments. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Fang L, Lin L, et al. Effects of low molecular-weight organic acids and dehydrogenase activity in rhizosphere sediments of mangrove plants on phytoremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chemosphere. 2014;99:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyszkowska J, Kucharski J. Correlation between the number of cultivatable microorganisms and soil contamination with diesel oil. Polish J Environ Stud. 2005;14:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav AK, Manna S, Pandiyan K, et al. Isolation and characterization of biosurfactant producing Bacillus sp. from diesel fuel-contaminated site. Microbiology. 2016;85:56–62. doi: 10.1134/S0026261716010161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Kloepper JW, Ryu CM. Rhizosphere bacteria help plants tolerate abiotic stress. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Tam NFY. Effects of used lubricating oil on two mangroves Aegiceras corniculatum and Avicennia marina. J Environ Sci. 2007;19:1355–1360. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(07)60221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yenn R, Borah M, Boruah HPD, et al. Phytoremediation of abandoned crude oil contaminated drill sites of Assam with the aid of a hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial formulation. Int J Phytoremediat. 2014;16:909–925. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2013.810573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CG, Leung KK, Wong YS, Tam NFY. Germination, growth and physiological responses of mangrove plant (Bruguiera gymnorrhiza) to lubricating oil pollution. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;60:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2006.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziervogel K, Arnosti C. Enhanced protein and carbohydrate hydrolyses in plume-associated deepwaters initially sampled during the early stages of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Deep Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2016;129:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuloaga O, Prieto A, Usobiaga A, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in intertidal marine bivalves of sunderban mangrove Wetland, India: an approach to bioindicator species. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2009;201:305–318. doi: 10.1007/s11270-008-9946-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Accession Number: All taxonomic sequence data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (GenBank) under BioProject ID SUB7449012.