Abstract

Vitamin D3 and its metabolites have anti-tumorigenic properties in vitro and in vivo; however, clinical trials and retrospective studies on the effectiveness of vitamin D3 oral supplementation against cancer have been inconclusive. One reason for this may be that clinical trials ignore the complex vitamin D metabolome and the many active vitamin D3 metabolites present in the body. Recent work by our lab showed that 24R,25(OH)2D3, a vitamin D3 metabolite that is active in chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation, has anti-tumorigenic properties in estrogen receptor alpha-66 (ERα66) positive (ER+) breast cancer, but not in ERα66 negative (ER-) breast cancer. Here we show that 24R,25(OH)2D3 is pro-tumorigenic in an in vivo mouse model (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice) of ER- breast cancer, causing greater tumor growth than in mice treated with vehicle alone. In vitro results indicate that the effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 is via a membrane-associated mechanism involving ERs and phospholipase D. 24R,25(OH)2D3 increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis in ERα66-negative HCC38 breast cancer cells, and stimulated expression of metastatic markers. Overexpressing ESRI, which encodes ERα66, ERα46 and ERα36, reduced the pro-apoptotic response of ERα66- cells to 24R,25(OH)2D3, possibly by upregulating ERα66. Silencing ESR1 in ERα66+ cells increased apoptosis. This suggests 24R,25(OH)2D3 is differentially tumorigenic in cancers with different ERα isoform profiles. Anti-apoptotic actions of 24R,25(OH)2D3 require ERα36 and pro-apoptotic actions require ERα66.

Keywords: 24R,25(OH)2D3; Vitamin D3 metabolites; Breast cancer; Estrogen receptor α; ERα36

Introduction

Interest in vitamin D3 as an anti-tumorigenic agent first peaked when epidemiologists noticed that the incidence of certain cancers, including breast cancer, inversely correlated with daily sun exposure 1,2. Vitamin D3 is synthesized in skin in response to UVB radiation from sunlight. Retrospective clinical studies showed that reduced exposure to UVB correlated with low levels of serum vitamin D3, and low serum vitamin D3 correlated with an increased risk for breast cancer 3. Similarly, epidemiological studies showed vitamin D3 supplementation was associated with reduced risk of breast cancer recurrence 4. However, recent large-scale double-blind clinical trials have concluded that there is no connection between vitamin D3 supplementation and breast cancer incidence in the general population 5,6.

There are two possible reasons for this discrepancy. Most clinical studies that examine the efficacy of vitamin D3 treat breast cancer as a homogeneous disease with uniform presentation. In actuality, breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease that can present with several distinct molecular subtypes. Detailed clinical and retrospective analyses have shown that low serum vitamin D3 is associated with an increased risk of developing estrogen receptor alpha-66 (ERα66) positive (ER+) cancer, but not ERα66 negative (ER-) cancer 7. Furthermore, vitamin D supplementation is associated with a reduced risk of developing new or recurrent tumors in patients with ER+ cancer, but not patients with ER- cancer 4,8.

Another reason may be that most studies that examine the anti-cancer properties of vitamin D3 limit their investigations by correlating cancer incidence with oral vitamin D3 intake or with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) 9–11. Serum 25(OH)D3 measurements provide an incomplete picture of the active vitamin D metabolome. Vitamin D3 is metabolized in the liver to 25(OH)D3 12. In the kidney 25(OH)D3 is hydroxylated into a number of active vitamin D3 metabolites, including the well-described 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1α,25(OH)2D3) and the less studied 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (24R,25(OH)2D3) 13. 1α,25(OH)2D3 is partially responsible for maintaining calcium homeostasis and bone mineralization and has been shown to have some anti-cancer properties 14. However, it has a narrow therapeutic window and can induce hypercalcemia. 24R,25(OH)2D3 circulates at higher levels than 1α,25(OH)2D3 15,16. It is less calcemic, but it can be further metabolized to 1,24,25(OH)3D3. The serum and tissue levels of 25(OH)D3, 1,25(OH)2D3, 24,25(OH)2D3 and 1,24,25(OH)3D3 are highly regulated and interdependent, complicating studies that focus on only one parameter.

A number of studies show that vitamin D metabolites can be produced in many different cell types and can regulate a number of different cell functions. We and others have shown that 24R,25(OH)2D3 is responsible for maintaining cartilage extracellular matrix and may regulate the cell cycle in chondrocytes, whereas 1α,25(OH)2D3 stimulates their terminal differentiation 17–19. In addition, both 1α,25(OH)2D3 and 24R,25(OH)2D3 can affect the immune system by regulating the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines 19,20. 1α,25(OH)2D3 causes reduced production of pro-inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and interleukin 6 (IL-6) by monocytes in in vitro co-culture with colon cancer cells 20. 24R,25(OH)2D3 has likewise been shown to reduce serum levels of pro-inflammatory factors in rat models of osteoarthritis 19. By regulating the immune system, both 1α,25(OH)2D3 and 24R,25(OH)2D3 may indirectly alter cancer invasion and metastasis.

1α,25(OH)2D3 acts on cells via the canonical cytosolic/nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR), which modulates gene transcription, and via membrane-associated signaling pathways involving the VDR and another membrane protein, protein disulfide isomerase A3 (PDIA3), which acts through a phospholipase A2/protein kinase C signaling mechanism 21,22. In contrast, 24R,25(OH)2D3 acts through a phospholipase D (PLD) mediated p53 signaling pathway that does not involve either the VDR or PDIA3 23. Signaling by 24R,25(OH)2D3 results in both rapid non-genomic and genomic responses[33,40,41], supporting the presence of receptor(s) for this vitamin D metabolites, and several candidates have been proposed 24–28. However, whether one or more of these receptors are involved is not known.

The role that 24,25(OH)2D3 plays in tumorigenesis is not clear. It has anti-tumorigenic properties in certain cancers 29, including lung and stomach carcinomas 29,30, but an increase in 24-hydroxylase, the enzyme that increases production of 24R,25(OH)2D3, has been associated with increased tumorigenicity in models of colorectal carcinoma 31. Recently, our lab showed that 24R,25(OH)2D3 is active in breast cancer cell lines and that 100 ng 24R,25(OH)2D3 given three times a week is non-calcemic and anti-tumorigenic in a rat model of ER+ breast cancer 14. Moreover, the mechanisms by which 24R,25(OH)2D3 exerts its effects are not clear. It is anti-tumorigenic in ERα66+ breast cancer cell lines, but it is pro-tumorigenic in HCC38 cells, a breast cancer cell line that lacks ERα66 but expresses the membrane-associated ERα isoform, ERα36 14, suggesting that a relationship with ERα isoforms may be involved.

In vitro studies support this hypothesis. The actions of 24R,25(OH)2D3 in breast cancer are modulated by a rapid, membrane-associated PLD-dependent mechanism 14, similar to the actions of 17β-estradiol (E2) via ERα36 32. Breast cancer cells that are “ER+” express the classical isoform ERα66, whereas “ER-” cells do not express ERα66. Both ER+ and ER- breast cancer cells may express other ERs, including ERα36 32,33. HCC38, the cell line used for the present study, does not express ERα66 or ERα46, but it does express low levels ERα36 34, making it a useful model for isolating the relationship between 24R,25(OH)2D3 and ERα66. We hypothesized that the pro-apoptotic effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 might be regulated in part by the canonical receptor, ERα66, rather than the rapid signaling receptor, ERα36, thus implying a role for the canonical receptor ERα66 in the signaling of 24R,25(OH)2D3.

In this paper, we used a model of in vivo breast cancer created in NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice, which have compromised immune systems and do not produce mature B cells, T cells, natural killer cells, or complement of any kind. This model allowed us to study the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 directly on the tumor independently from the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on the immune system. In addition, we examined the requirement for ERα66 in mediating the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 by overexpressing and silencing ESR1 in HCC38 cells.

Materials & Methods

Cell Lines

MCF7, an epithelial-like ERα66-positive, ERα36-positive breast cancer cell line; HCC38, a mesenchymal-like ERα66-negative, ERα36-positive breast cancer cell line; MDA-MB-231, a triple negative ERα66-negative, ERα36-positive breast cancer cell line (Figure S1A,B) and T-47D, an ERα66-positive, ERα36-positive ductal epithelium breast cancer cell line, were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and used to study the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on breast cancer cells with different phenotypes and ERα profiles. C2C12 cells (ERα66-negative, ERα36-positive), an unrelated mesenchymal cell line (pre-myoblasts) that is not tumorigenic, were also purchased from ATCC and used to study the effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on cells without a tumorigenic phenotype. Experiments were conducted within 6 months of cell purchase. All cell lines were maintained according to ATCC guidelines as previously described 34. All cell lines were certified mycoplasma free by Hoechst DNA stain (indirect) method, Agar culture (direct) method, and PCR-based assay. Cells were not subsequently tested for mycoplasma.

To assess the dependence of the 24R,25(OH)2D3 effect on cells with different ERα profiles, ESR1 (encodes ERα66, ERα46, and ERα36) was transiently and stably overexpressed in HCC38 and C2C12 cells respectively, using an open reading frame plasmid. ERα66 was knocked down in MCF7 cells using an ESR1-targeting shRNA. To determine whether the 24R,25(OH)2D3 used a caveolae-dependent protein complex, HCC38 cells were knocked down for caveolin-1 using shRNA that targeted the CAV1 gene. For more details, please see the Supplemental Methods. Success of silencing and overexpression was validated by RT-PCR and western blots. The primers used are detailed in Supplemental Table 1 and the antibodies used for the western blots are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

In Vivo Studies

All animal experiments were approved by VCU’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were monitored for signs of hypercalcemia and other health and behavioral changes throughout the course of the study.

Effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on Xenograft Tumor Growth

To study the direct effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on breast cancer tumorigenicity in vivo, a mammary fat pad model of breast cancer was created in female 6–8 week old Nod-Scid-gamma IL2γ (NSG) mice obtained from the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Cancer Mouse Models Core Laboratory at Massey Cancer Center (Richmond, VA). NSG mice lack all immune cells except neutrophils and macrophages, and are therefore a common model for studying the effects of anti-tumorigenic agents independent of immuno-regulation 35. One million HCC38 cells were injected into the right fourth mammary gland of a female NSG mouse. The next day, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 0, 25 ng, or 100 ng of 24R,25(OH)2D3. Injections continued 3 times a week for the remainder of the study. Tumors were tracked with digital calipers twice a week from week 2–8 (harvest). Details are provided in supplementary methods.

In vitro Studies

Response to Vitamin D3 Metabolites

To examine the specificity of the 24R,25(OH)2D3 response, in vitro experiments were done with 24R,25(OH)2D3, its enantiomer 24S,25(OH)2D3, and 1α,25(OH)2D3, another vitamin D3 metabolite. 24R,25(OH)2D3, and 1α,25(OH)2D3 were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY); 24S,25(OH)2D3 was purchased from Millipore-Sigma (cat# 29447). Stock solutions were prepared in absolute ethanol and diluted in culture medium as previously described 14. For more details, please see supplementary methods.

Signaling Pathway Inhibition

In this set of experiments, we assessed the role of established 24R,25(OH)2D3 membrane-associated signaling second messengers in breast cancer cells. Cells were pre-treated for 30 minutes with inhibitors or vehicle in complete media as previously described 14. In brief, cultures were pretreated with 1–10μM 2-bromopalmitate (Millipore-Sigma #21604)36 to inhibit palmitoylation, 0.1–1 μM wortmannin (VWR, Radnor, PA, cat# 80055508) 23 to inhibit phospholipase D (PLD), or 1–10mM methyl β-cyclodextrin (Millipore-Sigma #C4555) in serum-free media to deplete cell membranes of cholesterol and disrupt intact caveolae 14.

Outcome Measures

DNA synthesis

To examine the effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on proliferation, cells were cultured to 70% confluence, then serum-starved for 48 hours to assess DNA synthesis 14. At that time, cells were treated with 24R,25(OH)2D3, 24S,25(OH)2D3, or 1α,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes and incubated with fresh complete media for 24 hours, harvested, and assayed for EdU incorporation according to manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, #C10214) 14.

Gene expression

Gene expression was used to examine the expression of markers of apoptosis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), metastasis, and the expression of hydroxylase enzymes. HCC38, which does not express ERα66 34 but does express ERα36, and MCF7, which expresses all ERα isoforms 34 were treated with 24R,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle for 15 minutes and then incubated with fresh media for 24 hours. RNA was isolated with TriZol, reverse-transcribed into cDNA, and probed for gene-specific primers for BAX and BCL2 as markers of apoptosis, the mesenchymal-associated transcription factor snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (SNAI1), receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2 (ERBB2), and MMP1 as markers of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) and primers for chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), C-X-C- motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12), osteoprotegerin (OPG), and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) as markers of metastasis. Primers are given in supplemental table 2 14. For more details, please see the supplementary methods. Untreated cultures of HCC38 and MCF7 cells were also assessed for CYP24A1 (24-hydroxylase) and CYP27B1 (1-hydroxylase) mRNA and normalized to GAPDH to assess the relative expression of vitamin D metabolic enzymes.

p53 content

To further assess apoptosis, total and S-15 phosphorylated p53 were measured 24 hours post-cell treatment in human cells with 24R,25(OH)2D3 as described above using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems, cat# DYC1043 & cat# DYC1839). Total p53 content was measured in C2C12 cells with a p53 pan ELISA (Millipore-Sigma cat# 11828789001).

DNA fragmentation

DNA fragmentation was assessed by colorimetric terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (Trevigen, TiterTAC™ in situ microplate TUNEL assay) as another marker of apoptosis. Cells were incubated with vehicle or 24R,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes, followed by incubation in fresh media for 24 hours. Samples were harvested and processed for TUNEL staining following the manufacturer’s instructions 14.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for secreted proteins

ER+ breast cancer has been shown to metastasize to bone in a preferential manner and increase bone resorption 37. To assess the potential of 24R,25(OH)2D3 to alter matrix turnover and bone resorption by breast cancer cells, confluent cultures were treated with vehicle or 24R,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes, aspirated, and then incubated in complete media. After 24 hours, conditioned media were collected and assayed for MMP-1, OPG, and RANKL using sandwich ELISAs. Cell monolayers were lysed in 0.05% Triton-X-100 and total DNA content was measured. Bone metastatic markers are expressed as a ratio of OPG/RANKL. Collagenase data are presented as a ratio of ng MMP1/μg DNA 14. For more details, please see the supplementary methods.

Osteoclast activity

To assess the potential of 24R,25(OH)2D3 to alter the activity of bone cells in the bone metastatic niche, osteoclast (OC) activity was measured using a commercially available europium-conjugated human type I collagen-coated OsteoLyse™ Assay Kit, as previously described 38. OCs were differentiated for 7 days. Simultaneously, HCC38 confluent cultures were treated with vehicle or 24R,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes, then aspirated and incubated with fresh complete media for 24 hours. Conditioned media from HCC38 cells were collected and cultured with OCs for an additional 7 days. After 7 days of culturing with HCC38-conditioned media (14 days total), OC activity was measured as above.

Wound closure assay

A wound closure assay was used to demonstrate cell migration, which can be indicative of metastasis. Confluent cultures of HCC38 cells were treated for 15 min with media containing vehicle or 24R,25(OH)2D3. Another set of cultures was treated with 10−7M 17β-estradiol as a positive control. Following treatment, a scratch was drawn from one end of the well to the other using a sterile 1 mL pipette tip. The loosened cells were aspirated along with the treatment media, and fresh media added to the cultures. A phase-contrast microscope was used to take pictures of each well at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 hours after the scratch was made. Wound area was calculated using Adobe Photoshop™ 2 software, normalized to the original wound closure area, and presented as percent wound closure. Data presented are from one of two repeated experiments 14.

Effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on PLD and PKC

24R,25(OH)2D3 increases PLD activity after 9 minutes in chondrocytes 23. In these studies, breast cancer cells were plated in 24-well plates and treated for 9 minutes with 24R,25(OH)2D3. Immediately after treatment, cells were aspirated, washed twice with 1X DPBS, and harvested with 200μL/well of PLD or PKC assay buffer according to manufacturer’s instructions. PLD activity was measured using the Amplex Red PLD assay (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, cat# A12219) 32. PKC activity was measured using the PKC Activity Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat# ab139437) 39.

Statistical Analysis

Data shown for HCC38 cells are from single representative experiments of two or more repeats and are presented as the mean ± standard error of six independent cultures per treatment group. In addition, in order to control for variations in baseline values due to potential differences in culture media (e.g., FBS), we calculated treatment/control ratios for MCF7 and HCC38 cells. These were derived from three to six individual sets of experiments for each variable. Thus, each experiment’s T/C ratio was treated as an N=1 in assessing statistical significance of any differences compared to control values. Data were analyzed by ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test to determine significance between groups. For more details, please see the supplementary methods.

Results

17β-Estradiol supplementation is not required to support HCC38 mammary fat pad xenografts in NSG mice.

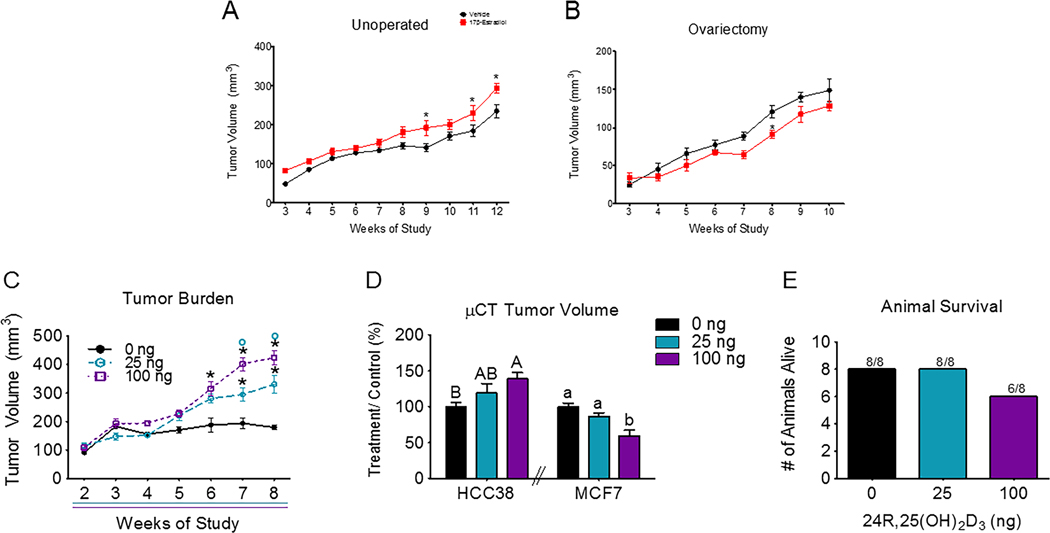

Systemic E2 did not significantly alter HCC38 tumor burden until week 8 (ovariectomized mice) or week 9 (un-operated mice) (Figure 1A–1B). At weeks 9, 11, and 12, E2 statistically increased HCC38 tumor burden in un-operated mice. In ovariectomized mice, E2 statistically decreased tumor burden at week 8, but did not significantly alter tumor burden at any other time point in the study. Tumors grown in mice with intact ovaries (un-operated mice) were slightly larger at 3 weeks (~50–75 mm3) as compared to ovariectomized mice (~30 mm3). This slight increase in tumor burden in un-operated mice continued throughout both studies, with tumors in un-operated mice being slightly larger (~200 mm3) than tumors in ovariectomized mice (~150 mm3) at the end of the study at 10 weeks (Figure 1A,B).

Figure 1: Breast cancer cell lines differentially respond to 24R,25(OH)2D3.

[A] Unoperated female NSG mice implanted with HCC38 xenograft mammary fat pad tumors were intraperitoneally injected with 2.5mg/kg 17β-estradiol or a vehicle twice a week for 12 weeks. Tumor burden was measured twice a week throughout the course of the study and plotted against time. [B] A similar study was done with ovariectomized NSG mice. HCC38 xenografts were treated with the same dose (2.5mg/kg) or 17β-estradiol) or a vehicle and tumors were measured twice a week until harvest at 10 weeks. The n=6 animals per group for these studies. *indicates statistical significance against week-matched vehicle tumors at α=0.05 with two-way ANOVA. [C] NSG mice with HCC38 mammary fat pad xenograft tumors were intraperitoneally injected with 25 or 100 ng of 24R,25(OH)2D3 3 times a week for 8 weeks. Tumor burden was measured with digital calipers and plotted against time. Animals given 24R,25(OH)2D3 had increased tumor burden as measured by digital calipers. *indicates significance as compared to vehicle-treated animals within the same time point. O indicates significance as compared to animals treated with 25 ng of 24R,25(OH)2D3 within the same time point. [D] Animals given 24R,25(OH)2D3 had increased tumor burden as measured by μCT as compared to tumor burden in vehicle-treated mice. Capital letters were used to indicate significance within HCC38 xenograft tumor groups, while lower-case letters were used to indicate significance within MCF7 tumor groups. Groups that do not share a letter are statistically significant. [E] After 8 weeks, 8 animals from the vehicle group, 8 animals from the low-dose (25 ng per injection) 24R,25(OH)2D3 group, and 6 animals from the high-dose (100 ng per injection) 24R,25(OH)2D3 group survived out of an original n of 8. Animals in the high-dose group did not have a statistically significant reduced survival rate as compared to animals in low dose or vehicle groups.

Tumors grew at a linear rate in vehicle-treated (R2=0.786) and E2-treated (R2=0.764) un-operated mice with slopes of 2.66 ± 0.18 mm3/day and 3.21 ± 0.23 mm3/day, respectively. The slopes of the vehicle-treated and E2-treated tumors were significantly different from each other with E2-treated tumors growing faster than vehicle-treated tumors in un-operated mice. In ovariectomized mice, tumors also grew at a linear rate with vehicle-treated (R2=0.83) and E2-treated (R2=0.79) tumors having slopes of 2.6 ± 0.2 mm3/day and 2.0 ± 0.2 mm3/day respectively. The slopes of the vehicle-treated and E2-treated tumors were also significantly different from each other, but E2 treated tumors grew more slowly than vehicle-treated tumors in ovariectomized mice. A linear regression analysis found that both vehicle and E2-treated tumors had significantly non-zero slopes in both un-operated and ovariectomized mice.

Treatment with 24R,25(OH)2D3 increased tumor burden in the HCC38 xenograft model of breast cancer.

Mice receiving either 25 ng or 100 ng per injection of 24R,25(OH)2D3 had a greater HCC38 tumor burden than mice given a vehicle control injection (Figure 1C). This increase in tumor volume in 24R,25(OH)2D3 treated mice began at week 6 and continued until harvest at week 8. In previous HCC38 mammary fat pad xenograft studies, vehicle-treated HCC38 tumors reached a final volume of 150–200 mm3 (Figure 1A, B), consistent with vehicle-treated HCC38 tumors in this study. Tumors in mice given 100ng of 24R,25(OH)2D3 per injection were significantly larger than tumors in mice given 25 ng at weeks 7 & 8. At harvest at week 8, tumors in mice given 100 ng were ~33% larger (final volume ~400 mm3) than tumors in mice given 25ng of 24R,25(OH)2D3 per injection, which reached a final volume of ~300 mm3. As in previous HCC38 mammary fat pad xenograft studies, HCC38 tumors were linear with non-zero slopes of 1.64 ± 0.43 mm3/day (vehicle), 5.5 ± 0.5 mm3/day (25 ng 24R,25(OH)2D3) and 7.6 ± 1.2 mm3/day (100 ng 24R,25(OH)2D3). All three slopes were significantly non-zero and different from each other. Treatment with high-dose 24R,25(OH)2D3 increased tumor growth rate and tumor burden in HCC38 xenografts by approximately 50%, as compared to a 50% decrease in tumor burden by 24R,25(OH)2D3 in MCF7 xenografts as measured by μCT (Figure 1D). Signs of hypercalcemia, such as anorexia, vomiting, lethargy, fatigue, and polyuria, were not detected in animals treated with a vehicle or with either dose of 24R,25(OH)2D3. In the high-dose 24R,25(OH)2D3 HCC38 xenograft group, only 6 out of 8 animals survived to the end of the study as compared to 8 out of 8 animals in the vehicle and low-dose 24R,25(OH)2D3 groups. However, this reduction in animal survival was not statistically significant (Figure 1E).

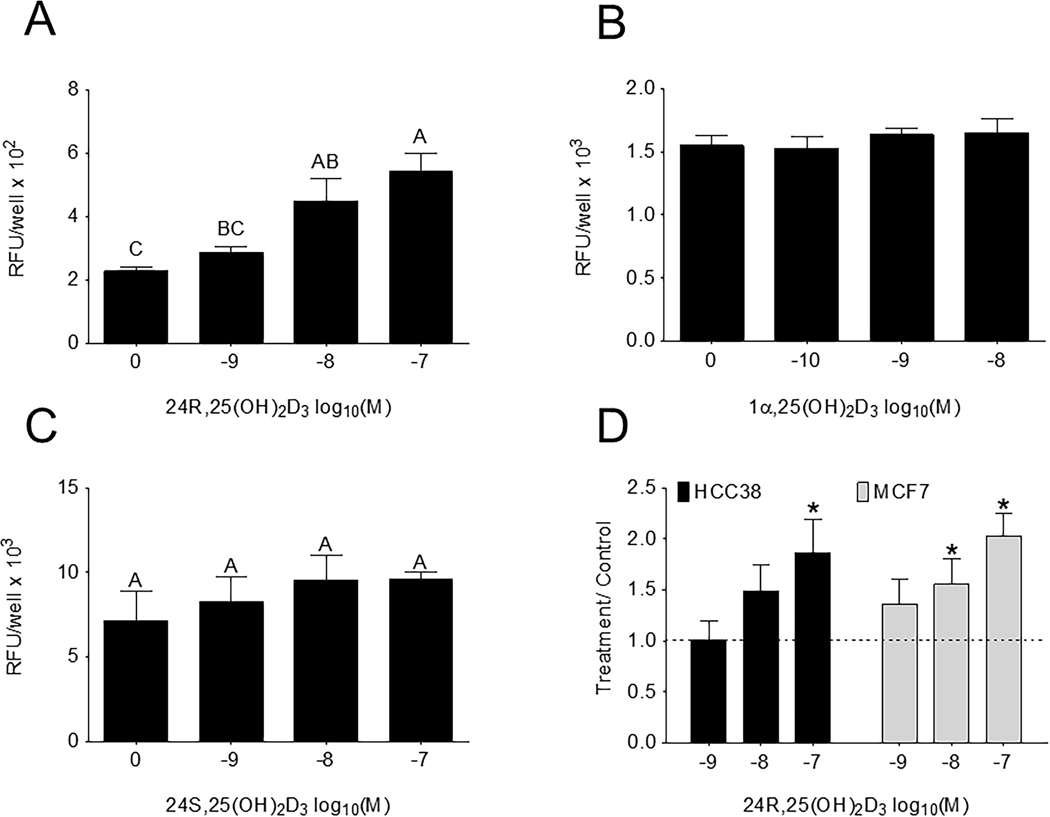

24R,25(OH)2D3 regulated proliferation of HCC38 cells in vitro.

When HCC38 cells were treated for 15 minutes with 24R,25(OH)2D3 proliferation increased after 24 hours (Figure 2A) as measured by DNA synthesis. However, treatment with 24S,25(OH)2D3, an enantiomer of 24R,25(OH)2D3, or 1α,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes did not change proliferation after 24 hours (Figure 2B, C). The effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 was dose-dependent with the greatest increase at 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3. The effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 was also observed in MCF7 cells 14, with both 10−8 and 10−7 24R,25(OH)2D3 increasing DNA synthesis (Figure 2D). In both HCC38 and MCF7 cells, 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 increased DNA synthesis ~two-fold above vehicle-treated cultures.

Figure 2: 24R,25(OH)2D3 specifically induces proliferation in HCC38 cells.

HCC38 monolayer cultures were serum-starved for 48 hours, treated with 24R,25(OH)2D3, 24S,25(OH)2D3, or 1α,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes and assayed 24 hours later for EdU incorporation. [A] 24R,25(OH)2D3, but not [B] 24S,25(OH)2D3 nor [C] 1α,25(OH)2D3, induced proliferation in HCC38 cell monolayers 24 hours after a 15-minute treatment. [D]. Data shown are from single representative experiments of two or more repeats and are presented as the mean ± standard error of six independent cultures per treatment group. Treatment over control was calculated as the average fold-change of treatment as compared to vehicle-treated cultures in three or more experiments and analyzed with a paired t-test against normalized vehicle controls. *indicates significance at P<0.05 as compared to vehicle-treated cultures. High-dose 24R,25(OH)2D3 induced proliferation in HCC38 and MCF7 cell monolayers 2-fold over control.

The addition of 24R,25(OH)2D3 to MDA-MB-231 cells (ER-) had a biphasic effect on DNA synthesis. DNA synthesis was increased at 10−8M and decreased at 10−7M 24R,25 (OH)2D3 (Figure S1C). The addition of 24,25 (OH)2D3 to T-47D cells (ER+) caused a dose dependent increase in DNA synthesis (Figure S2A).

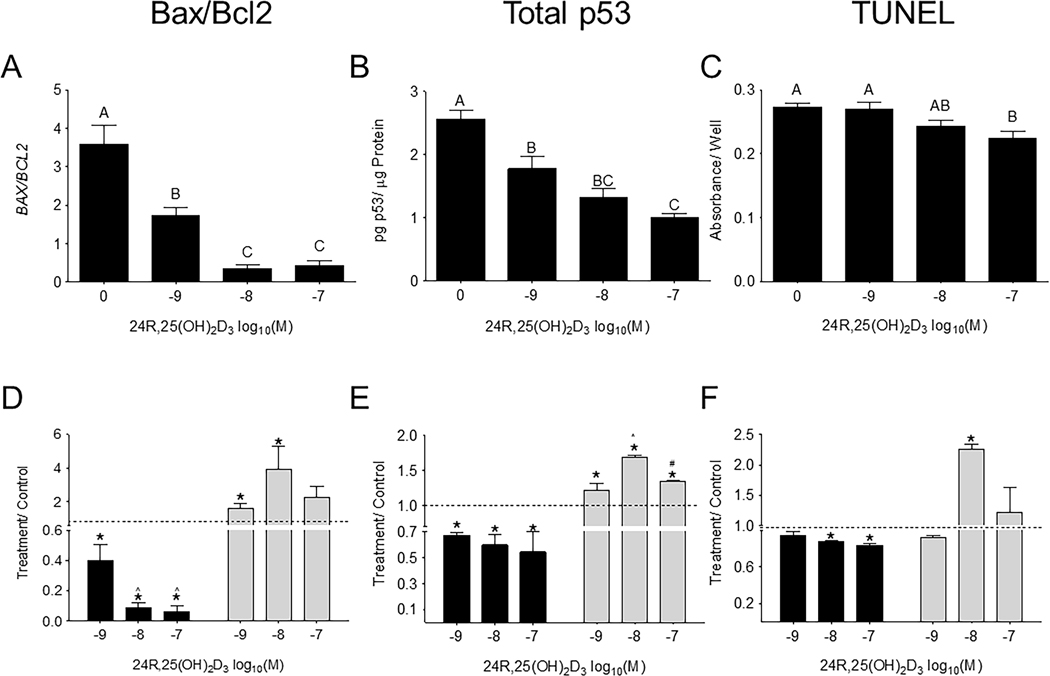

The effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on apoptotic markers varied with ERα66 status.

In HCC38 cells, 24R,25(OH)2D3 caused a dose-dependent decrease in B cell lymphoma protein 2-associated X protein (BAX) to B cell lymphoma protein 2 (BCL2) expression ratios (BAX/BCL2), which was significant at 10−8M and 10−7M (an ~8-fold decrease) (Figure 3A). 24R,25(OH)2D3 had a similar reducing effect on total p53 levels (Figure 3B) and TUNEL staining (Figure 3C), with the 10−7M dose producing the maximum decrease in p53 levels and TUNEL. 24R,25(OH)2D3-induced fold-change decreases in apoptosis in HCC38 cultures were similar in proportion to 24R,25(OH)2D3-induced fold change increases in apoptosis observed in MCF7 cultures (Figure 3D–F). However, in HCC38 cells, 24R,25(OH)2D3 had the greatest effect at 10−7M on BAX/BCL2, total p53, and TUNEL staining, whereas in MCF7 cells, maximal effect sizes were observed at 10−8M 24R,25(OH)2D3.

Figure 3: 24R,25(OH)2D3 prevents apoptosis in HCC38 cells, but induces apoptosis in MCF7 cells.

HCC38 monolayer cultures were treated with 24R,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes, and harvested 12 hours later for gene expression and 24 hours later for protein and TUNEL staining. Cultures were assessed for apoptosis as measured by [A, D] BAX/BCL2 gene expression, [B, E] total p53 protein, and [C, F] TUNEL staining. [A-C] 24R,25(OH)2D3 reduced apoptosis in HCC38 cells. Groups that share a letter are not significant at p<0.05. [D-F] HCC38 or MCF7 monolayer cultures were treated with 24R,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes and assessed for apoptosis 12–24 hours later. Data shown are from single representative experiments of two or more repeats and are presented as the mean ± standard error of six independent cultures per treatment group. Treatment over control was calculated as the average fold-change of treatment as compared to vehicle-treated cultures in three or more experiments and analyzed with a paired t-test against normalized vehicle controls. *indicates significance at P<0.05 as compared to vehicle-treated cultures.

Addition of 24R,25(OH)2D3 to MDA-MB-231 cells (ER-) caused a reduction in TUNEL staining, which was significant at 10−7M (Figure S1D), and a dose-dependent reduction in p53 levels (Fig S1E). 24R,25 (OH)2D3 increased TUNEL and p53 in T-47D cells (ER-) in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S2B, S2C).

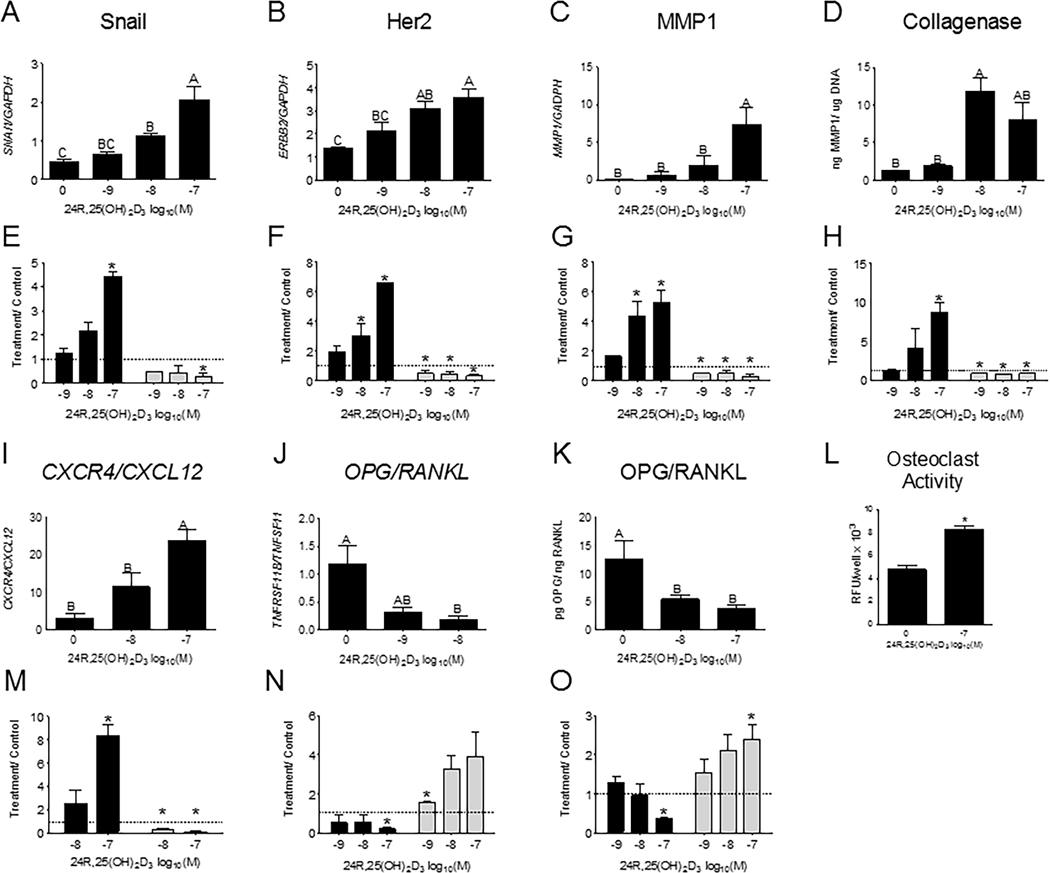

24R,25(OH)2D3 increased epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, metastatic markers, and migration in HCC38 cells in vitro.

Treatment with 10−8M and 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 significantly increased expression of SNAI1 compared to cells treated with vehicle (Figure 4A). Expression of ERBB2 and MMP1, which are associated with tumor aggression and matrix turnover respectively, was also increased by similar doses of 24R,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 4B,C), with the maximal effect at 10−7M. 24R,25(OH)2D3 had a biphasic effect on collagenase enzyme protein expression, with statistically significant induction of collagenase protein observed in cultures treated with 10−8M 24R,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 4D), and a non-significant increase in cultures treated with 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3. 24R,25(OH)2D3 (10−7M) stimulated a 4-fold increase in SNAI1 (Figure 4E), a 6-fold increase in ERBB2 expression (Figure 4F), a 6-fold increase in MMP1 expression (Figure 4G), and a 10-fold increase in collagenase protein expression (Figure 4H) as compared to vehicle-treated cultures (Figure 4E–H). This is in direct contrast to the effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on MCF7 cultures, where 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 reduced SNAI1, and all doses of 24R,25(OH)2D3 reduced ERBB2 and MMP1 transcript expression and reduced collagenase protein expression (Figure 4E–H).

Figure 4: 24R,25(OH)2D3 increases epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastatic markers in HCC38 cultures.

HCC38 and MCF7 monolayer cultures were treated with 24R,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes and harvested 12 hours later for gene expression. Effect of dose-dependent 24R,25(OH)2D3 on gene expression of [A, E] snail, [B, F] her2, [C, G] MMP1, [D, H] collagenase protein, [I, M] CXCR4/ CXCL12 ratios, [J, N] OPG/ RANKL ratios, and [K, O] OPG/RANKL protein. In [A-D, I-L] HCC38 cells 24R,25(OH)2D3 increases these gene markers, but reduces them in MCF7 cells [E-H, M-O]. [L] 24R,25(OH)2D3 increases osteoclast activity in osteoclasts treated with HCC38 conditioned media from cultures treated with 24R,25(OH)2D3. Groups that share a letter are not significant at p<0.05. Data shown are from single representative experiments of two or more repeats and are presented as the mean ± standard error of six independent cultures per treatment group. Treatment over control was calculated as the average fold-change of treatment as compared to vehicle-treated cultures in three or more experiments and analyzed with a paired t-test against normalized vehicle controls. *indicates significance at P<0.05 as compared to vehicle-treated cultures.

24R,25(OH)2D3 also increased metastatic markers in HCC38 cultures. 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 increased CXCR4 to CXCL12 ratios (CXCR4/CXCL12) (Figure 4I). 10−8M 24R,25(OH)2D3 decreased the ratio of OPG to RANKL transcripts (OPG/RANKL) (Figure 4J), and both 10−8M and 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 decreased OPG/RANKL protein expression (Figure 4K). Conditioned media from 24R,25(OH)2D3-treated HCC38 cells increased osteoclast activity more than conditioned media from vehicle-treated HCC38 cells (Figure 4L). 24R,25(OH)2D3 increased osteoclast activity by 100% as compared to vehicle-treated cells. 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 induced a 10-fold increase CXCR4/CXCL12 ratios (Figure 4M), and a 2-fold decrease in OPG/RANKL ratios (Figure 4N, 4O) in HCC38 cells. Both 10−8M and 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 decreased CXCR4/CXCL12 ratios and 10−9M and 10−7M increased OPG/RANKL transcript and protein expression ratios, respectively in MCF7 cells.

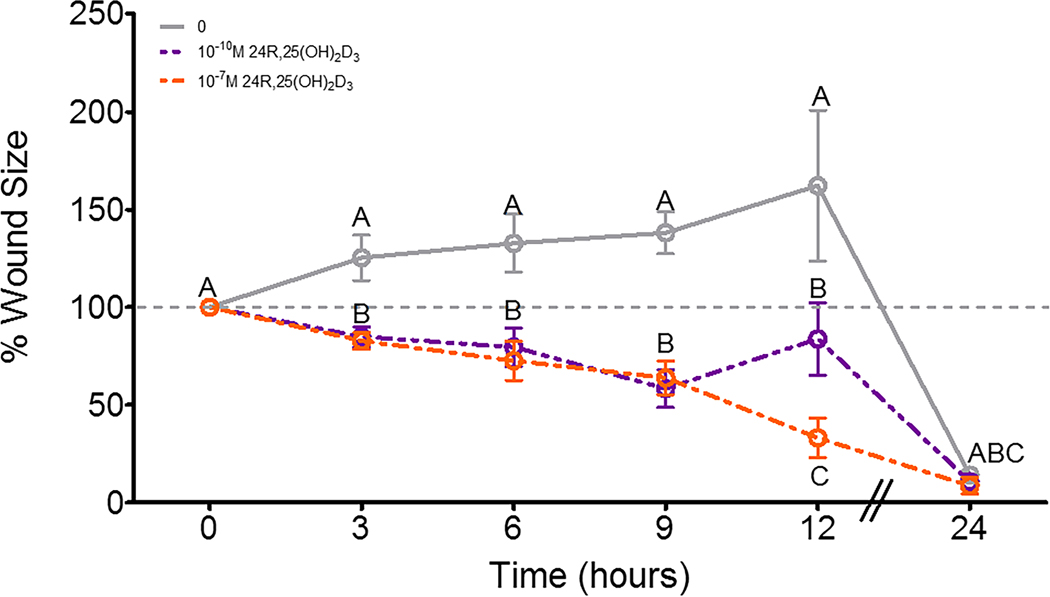

24R,25(OH)2D3 increased cell migration in a scratch test assay. 12 hours after a wound was made on a confluent culture of HCC38 cells, wound size in cultures given a vehicle treatment had not significantly altered, while 10−10M 24R,25(OH)2D3 had slightly decreased wound size, and 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 had reduced wound size to ~25% of its original area (Figure 5). 24 hours after the scratch test was initiated, all cultures had closed their wounds.

Figure 5: Effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on cell migration in HCC38 cell monolayers.

HCC38 monolayer cultures were treated with 24R,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes and incubated with fresh media. A scratch was made across the culture with a 1mL pipette tip, and monolayer cultures were observed over 24 hours for wound closure. . Data shown are from single representative experiments of two or more repeats and are presented as the mean ± standard error of six independent cultures per treatment group.

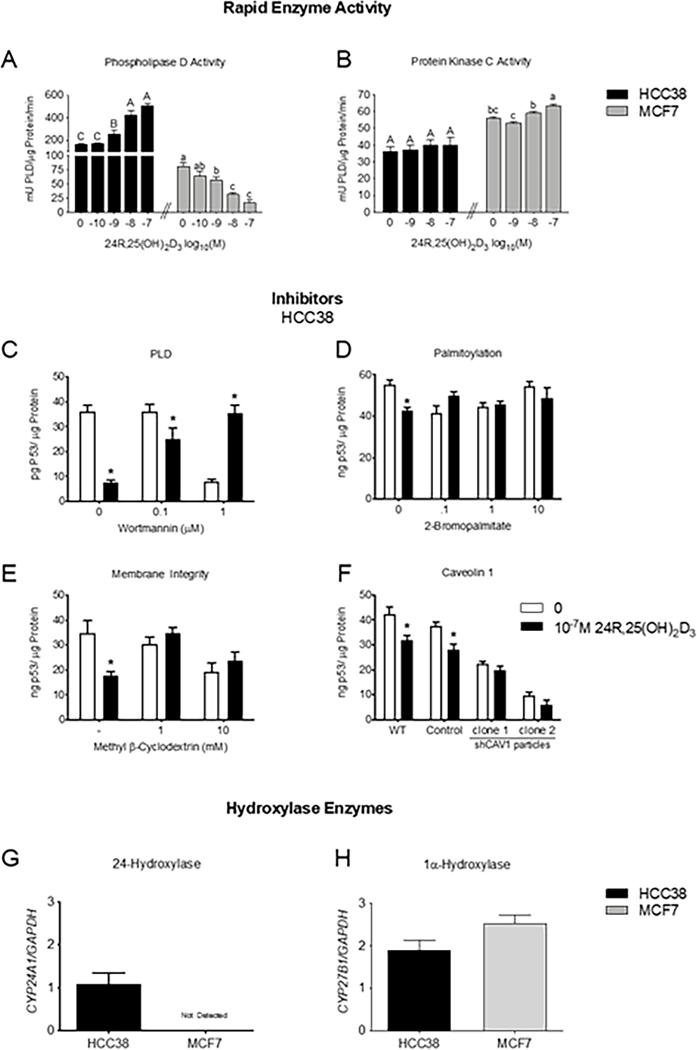

24R,25(OH)2D3 differentially regulates PLD and PKC activity in HCC38 and MCF7 cells.

24R,25(OH)2D3 dose-dependently increased PLD activity in HCC38 cells, with the maximal effect occurring at 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 (~3-fold increase as compared to vehicle-treated control cultures) (Figure 6A). However, 24R,25(OH)2D3 dose-dependently decreased PLD activity in MCF7 cells, with 10−7M reducing PLD activity to 25% that of vehicle-treated control cultures (Figure 6A). Treatment with 24R,25(OH)2D3 did not change PKC activity in HCC38 cells (Figure 6B); however, it did slightly increase PKC activity in MCF7 cells (Figure 6B). Baseline PKC activity in MCF7 cells was ~2-fold higher in MCF7 cells (~60 μU/μg protein/min) than in HCC38 cells (~30 μU/μg protein/min) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6: 24R,25(OH)2D3 reduces total p53 levels through a caveolae-associated, PLD-dependent mechanism.

HCC38 or MCF7 monolayer cultures were treated with 24R,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes, and assessed for [A] PLD activity, which is decreased, or [B] PKC activity. In a separate set of experiments, HCC38 monolayer cultures were treated with inhibitors for 30 minutes before treatment with 24R,25(OH)2D3 for 15 minutes and assessed for total p53 content. 24R,25(OH)2D3 reduced p53 levels in HCC38 cell monolayers, but this effect was prevented by treatment with [C] wortmannin to inhibit PLD activity, [D] 2-bromopalmitate to inhibit palmitoylation of nuclear receptors trafficked to the membrane, [E] methyl beta-cyclodextrin to deplete the membrane of cholesterol, and [F] short-hairpin RNA to silence caveolin-1. In a separate set of experiments, HCC38 and MCF7 breast cancer cells were cultured to confluence and harvested after 12 hours for gene expression. Cells were assessed for [G] CYP24A1 or [H] CYP27B1 expression and normalized to GAPDH as a housekeeping gene. . Data shown are from single representative experiments of two or more repeats and are presented as the mean ± standard error of six independent cultures per treatment group.

24R,25(OH)2D3 inhibits apoptosis through a caveolae-associated, PLD-dependent pathway.

PLD inhibition with low-dose wortmannin prevented a 24R,25(OH)2D3-induced reduction in p53 in HCC38 cells (Figure 6C). High-dose wortmannin reduced p53 levels, but treatment with 24R,25(OH)2D3 reversed this effect and increased p53 levels back to baseline p53 levels in vehicle-treated control HCC38 cultures (Figure 6C). 2-bromopalmitate (2BP) was used to prevent trafficking of palmitoylated nuclear receptors to the membrane. Treatment with all doses of 2BP prevented a 24R,25(OH)2D3-induced reduction in total p53 levels (Figure 6D). Methyl β-cyclodextrin (MBC) was used to deplete the cell membrane of cholesterol and destroy caveolae and lipid rafts. Treatment with 1mM and 10mM MBC prevented a 24R,25(OH)2D3-induced reduction in total p53 levels (Figure 6E).

To evaluate the role of the caveolae on 24R,25(OH)2D3 signaling in HCC38 cells, HCC38 cells were stably knocked down for caveolin-1 with shRNA (Figures S3 & S4). Caveolin-1 knocked down HCC38 cells (shCAV1-HCC38) had <10% of wild-type caveolin-1 protein, while empty control-transduced cells had >100% of wild-type caveolin-1 protein expression (Figure S3A, S3B). Caveolin-1 levels were similar for both clone #1 and clone #2 shCAV1-HCC38 cells (Figure S3A, B). 24R,25(OH)2D3 reduced total p53 protein expression in wild-type and scramble control HCC38 cells, but did not affect shCAV1-HCC38 cells. Baseline levels of p53 in shCAV1-HCC38 cultures were lower than wild-type, and empty-control transduced HCC38 cultures (Figure 6F).

Breast cancer cell lines differentially express 24-hydroxylase enzyme.

Breast cancer cells possess the ability to produce vitamin D metabolites locally, but enzyme expression is cell specific. HCC38 cells expressed both 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) and 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) (Figure 6G), while MCF7 cells did not express CYP24A1. Both HCC38 and MCF7 cells expressed similar levels of CYP27B1 (Figure 6H).

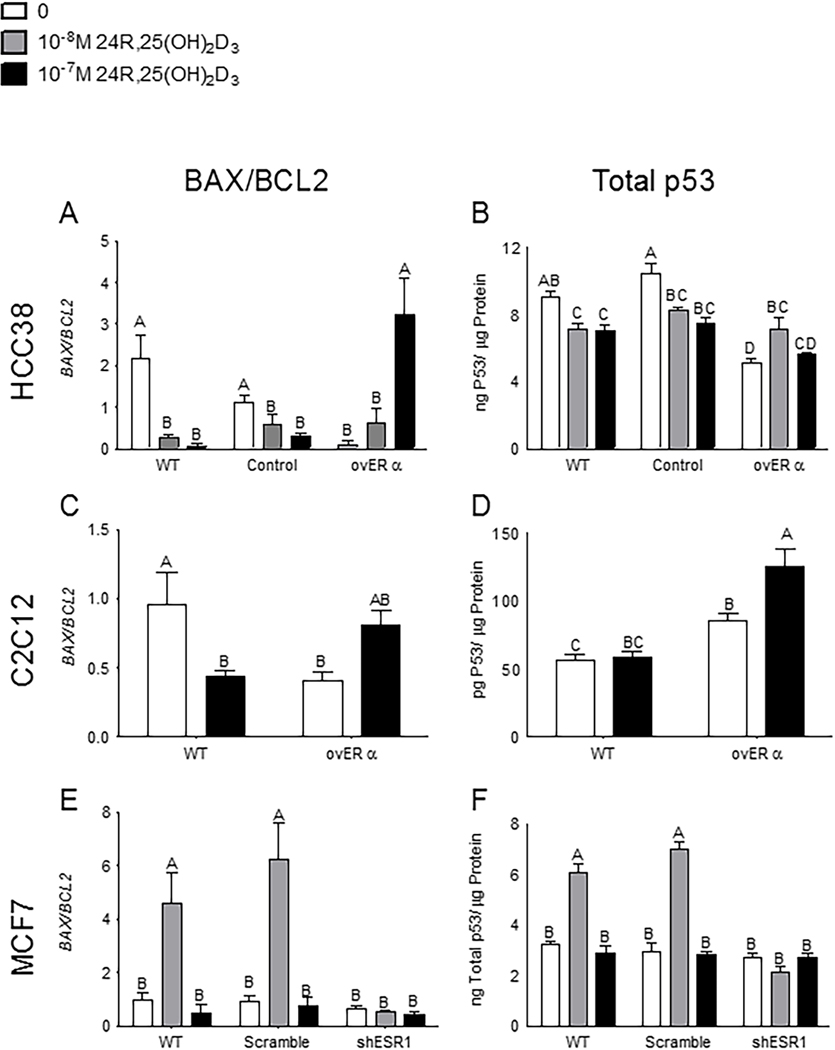

Overexpressing and silencing ESR1 changes the 24R,25(OH)2D3 response.

ESR1 was transiently overexpressed in HCC38 cells (Figure S5A,B, S6) and stably overexpressed in C2C12 cells (Figure S7, S8). ERα66 expression in ESR1-transfected HCC38 cells (ovERα-HCC38) was 20-times greater than wild-type HCC38 cells and 16-times greater than empty-control HCC38 cells (Figure S5C). ERα36 was 2.3-times greater in ESR1-transfected vs. wild-type HCC38 and 3-times greater than ORF-control HCC38 cells (Figure S5D). ERα46 was also increased in the ESR1-transfected cells. ESR1-transfected C2C12 cells (ovERα-C2C12) expressed 11-times more ERα66 protein expression than wild-type C2C12 cells (Figure S7A), and 2.8-times more ERα36 than wild-type C2C12 (Figure S7B,C).

24R,25(OH)2D3 prevented apoptosis in cells that did not express ERα66 but induced apoptosis in cells that expressed ERα66. In wild-type and ORF-control HCC38 cells, which express very low levels of ERα66 (Figure S5), all doses of 24R,25(OH)2D3 prevented apoptosis as measured by BAX/BCL2 (Figure 7A) and total p53 levels (Figure 7B). Treatment with 10−8M 24R,25(OH)2D3 induced apoptosis in ovERα-HCC38 cells (Figure 7A, B) as measured by both BAX/BCL2 and total p53. 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 upregulated BAX/BCL2 ratios in ovERα-HCC38 (Figure 7A). 24R,25(OH)2D3 had a biphasic effect on total p53 levels in ovERα-HCC38. 10−8 24R,25(OH)2D3 increased total p53 protein in ovERα-HCC38, but 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 did not affect p53 (Figure 7B). Wild-type and ORF-control HCC38 cells had similar baseline ratios of BAX/BCL2 mRNA (Figure 7A) and similar baseline levels of total p53 protein (Figure 7B), but ovERα-HCC38 cells had lower ratios of BAX/BCL2 mRNA and lower baseline p53 than wild-type HCC38 (Figure 7A, B).

Figure 7: Expression and silencing of ERα isoforms change the 24R,25(OH)2D3 response.

Overexpressing all ERα isoforms reversed the 24R,25(OH)2D3 anti-apoptotic effect in [A, B] HCC38 cells and [C, D] C2C12 cells. 24R,25(OH)2D3 prevented apoptosis as measured by [A] BAX/BCL2 and [B] total p53 levels in wild-type HCC38 and HCC38 cells transfected with an empty control vector, but induced apoptosis in ERα-transfected HCC38 cells. In C2C12 muscle cells, 24R,25(OH)2D3 prevented or did not induce apoptosis in wild-type cells but induced apoptosis in ERα-transfected cells as measured by [C] BAX/BCL2 and had no effect on apoptosis as measured by [D] total p53 levels in wild-type cells. Silencing the ERα66 isoform reversed the pro-apoptotic effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on [E, F] MCF7 cells. 24R,25(OH)2D3 induced apoptosis as measured by [E] BAX/BCL2 and [F] total p53 levels in wild-type and scramble-control MCF7 cells, but had no effect on apoptosis in ERα66-knocked down MCF7 cells. . Data shown are from single representative experiments of two or more repeats and are presented as the mean ± standard error of six independent cultures per treatment group.

In C2C12 muscle cells, which express low levels of ERα66 (Figure S7), 24R,25(OH)2D3 had an anti-apoptotic effect as measured by BAX/BCL2 mRNA ratios, but upregulated BAX/BCL2 mRNA ratios in ovERα-C2C12 cells (Figure 7C). Wild-type C2C12 cultures had higher baseline BAX/BCL2 mRNA ratios than ovERα-C2C12 cultures (Figure 7C). 24R,25(OH)2D3 did not affect total p53 levels in wild-type C2C12 cells but increased total p53 in ovERα-C2C12 (Figure 7D). Baseline total p53 was higher in ovERα-C2C12 cells than in wild-type C2C12 (Figure 7D). In both C2C12 and HCC38 cells, transfecting with ESR1 to overexpress the ERα isoforms changed the cell response to 24R,25(OH)2D3. 24R,25(OH)2D3 stimulated apoptosis in all HCC38 and C2C12 cultures that overexpressed ERα66 (Figure 7A–D).

ERα66 was stably knocked down in MCF7 cells (Figures S9, S10). Knocked down MCF7 (shESR1-MCF7) cells had approximately one-third the ERα66 expression of wild-type MCF7 cells, while scrambled controls had >80% of wild-type MCF7 cells expression (Figure S9A). ERα36 levels were similar for wild-type, scramble control, and shESR1-MCF7 cells, with the scrambled control and the shESR1-MCF7 cells expressing ~90% as much ERα36 as wild-type cells (Figures S9B, C).

24R,25(OH)2D3 upregulated BAX/BCL2 mRNA ratios and increased total p53 levels in wild-type and scrambled MCF7 cells at 10−8M (Figure 7E, F). 24R,25(OH)2D3 had no effect on BAX/BCL2 mRNA ratios or total p53 levels in shESR1-MCF7 cells (Figure 7E, F). Baseline BAX/BCL2 mRNA ratios and total p53 were the same in wild-type, scrambled, and shESR1 MCF7 cells. In wild-type, MCF7 cells, 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 also increased phosphorylated p53 but did not increase phosphorylated p53 in cultures that were knocked down for ERα66 (Figure S11). While 24R,25(OH)2D3 increased the average amount of phosphorylated p53 in scramble-control MCF7 cells as compared to vehicle-treated scramble-control MCF7 cells, this change was not statistically significant. Similarly, 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3 reduced average phosphorylated p53 in shESR1-MCF7 cells as compared to vehicle-treated shESR1-MCF7 cells; however, this difference was not statistically significant. Baseline phosphorylated p53 was not statistically different between wild-type, scrambled, and shESR1-MCF7 cells (Figure S11).

Discussion

In this paper, the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 were investigated in vivo in an HCC38 xenograft orthotopic mammary fat pad model of breast cancer in an immuno-compromised NSG mouse, and in vitro in monolayer cultures of HCC38 cells. The effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on a model of ERα66- breast cancer (HCC38 cells) were contrasted with the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 in a model of ERα66+ breast cancer (MCF-7 cells). The results reported here confirm our previously reported effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on MCF-7 cells 14. By comparing several sets of experiments in the present study using treatment/control ratios to eliminate differences in baseline values between experiments due to potential variations in culture conditions, we are able to more effectively assess differences between the two cell lines with respect to their response to the vitamin D metabolite.

The ESR1 receptor ERα66 was expressed in ERα66 negative HCC38 cells, overexpressed in ERα66 positive MCF7 cells, and a third unrelated cell line, ERα66 negative C2C12. All three cell lines constitutively express ERα36. In addition, ERα66 was successfully silenced in MCF7 cells, in order to understand how the expression of ERα66 modulates the effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3.

Treatment with 24R,25(OH)2D3 increased tumor burden and decreased animal survival in mice with HCC38 xenografts. In vitro, 24R,25(OH)2D3 specifically decreased apoptosis and increased proliferation, metastasis, and migration in HCC38 cells. This pro-tumorigenic effect is in direct contrast to the pro-apoptotic and anti-metastatic effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on MCF7 cells. Expressing and silencing ERα66 demonstrated that in cells that express ERα36, but do not express ERα66, 24R,25(OH)2D3 does not stimulate apoptosis and may be tumorigenic. In cells that express ERα66, 24R,25(OH)2D3 is pro-apoptotic and anti-tumorigenic. Our results suggest that ERα66 directly modulates the apoptotic effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3.

Our previous work showed that 24R,25(OH)2D3 is anti-tumorigenic in mammary fat pad xenografts of MCF7 cells in NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice. Here, we use a similar in vivo model to test the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on tumor burden in mammary fat pad xenografts of HCC38 cells in NSG mice. These models allowed us to study the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 directly on the tumor, rather than the direct and indirect effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on the tumor and concomitant immunity. Other studies have shown that 24R,25(OH)2D3 can reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines; 24R,25(OH)2D3 reduced serum levels of TNFα, IL-6, interleukin-1α, interleukin-1β, and other pro-inflammatory factors in Sprague-Dawley rats 19. While studies in this paper with immune compromised animals have shown that 24R,25(OH)2D3 is capable of directly modulating tumor growth in vivo, it is possible that 24R,25(OH)2D3 may also alter the concomitant immunity of carcinomas clinically, and this concomitant immunity could alter the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on the tumor directly. Although more studies are required to explore this possibility further, our in vitro data showing direct effects of 24R,25 (OH)2D3 on breast cancer cells support the conclusion that this vitamin D metabolite acts via mechanisms in addition to modulating the immune system.

Previously 24R,25(OH)2D3 was shown to have anti-carcinogenic properties in models of breast, lung, and glandular stomach carcinomas 14,29,30. However, high expression of 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1), the enzyme responsible for metabolizing 25(OH)D3 into 24R,25(OH)2D3, is associated with increased tumor aggression in several cancers including breast cancer 29–31,40. 24R,25(OH)2D3 has been shown to act both directly on bone, cartilage, kidney, and cancer cells, and indirectly by increasing the production of 1α-hydroxylated vitamin D3 metabolites in vivo 41,42. Physiologically, 24R,25(OH)2D3 increases the expression of 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) and 1α,25(OH)2D3, in turn, increases the expression of 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) 43. While HCC38 cells express both CYP24A1 and CYP27B1, our results and others have shown that MCF7 cells express CYP27B1 but do not express CYP24A1 40,44. It is possible that the MCF7 cells respond anti-tumorigenically to 24R,25(OH)2D3 because they are CYP24A1 negative, and this point should be explored further in future studies. MCF7 cells respond with the greatest fold-change to 10−8M 24R,25(OH)2D3 14, while in this paper we show that HCC38 cells are more sensitive to 10−7M 24R,25(OH)2D3. This may also indicate that MCF7 cells are more sensitive to 24R,25(OH)2D3 than HCC38 cells. Furthermore, our results with 24R,25(OH)2D3 on MCF7 and HCC38 cells may not be reflective of the direct effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3, but could be a result of shifting proportions of other vitamin D3 metabolites caused by an influx of 24R,25(OH)2D3. In our previous publication 14, we demonstrated that 24R,25(OH)2D3 can act on breast cancer cells. Here we focused on the interrelationship between 24R,25(OH)2D3 and ERα status, which is an important clinical indicator for the disease prognosis and treatment.

Our results show that the presence or absence of ERα66 had a major role in the response of breast cancer cells to 24R,25(OH)2D3. In ER- cells, 24R,25(OH)2D3 enhanced the cancer phenotype whereas in ER+ cells, 24R,25(OH)2D3 was inhibitory. To validate these observations, we examined the responses of a triple negative cells line, MDA-MB-231, and an ER+ cells line, T-47D, to 24R,25(OH)2D3. The results demonstrate that responses were enhanced in the triple negative ER- cells and inhibited in the ER+ cells, supporting our hypothesis that the level of ERα66 controls the 24R,25(OH)2D3 effect. Our finding showing that the response of C2C12 cells to 24R,25(OH)2D3 also depends on ERα, further supports this.

It needs to be mentioned that the effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on apoptosis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, metastatic markers, migration, PKC and PLD depended if the cells were ER+ or ER-; however, the effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on cell proliferation was similar in all cell types examined and was not dependent on the ERα level.

The role played by ERα36 in regulating the response to 24R,25(OH)2D3 is less clear. In cells that were transfected with ESR1, ERα36 was increased, although to a much lower level than ERα66. This is not surprising as ERα36 was expressed in HCC38 cells, which lack ERα66, as well as in C2C12 cells. Whereas ERα66 was knocked down in MCF7 cells, ERα36 was unaffected. Our cells were cultured in media that contains very low levels of E2, so it is possible that ERα36 dependent signaling was active. We have shown previously that rapid responses to E2 are via this receptor and the mechanisms involved, PLD and PKC, are shared with the actions of 24R,25(OH)2D3.

Our data on the effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on PLD and PKC activity in breast cancer cells suggest that 24R,25(OH)2D3 directly affects breast cancer cells and uses signaling pathways observed in other cell types. In male rat costochondral cartilage resting zone chondrocytes, the rapid actions of 24R,25(OH)2D3 are mediated by PLD, while the rapid actions of both 17β-estradiol and 1α,25(OH)2D3 are mediated by PKC 45. Our data show a similar effect, with 24R,25(OH)2D3 rapidly changing PLD activity in both HCC38 and MCF7 cells, but not affecting PKC activity in HCC38 cells at the same time point. 24R,25(OH)2D3 slightly increased PKC activity in MCF7 cells at high doses, but this effect had a smaller fold change than the effect size of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on PLD activity in MCF7 cells. The rapid effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on PLD rather than PKC activity in HCC38 and MCF7 cells suggests that in vitro, 24R,25(OH)2D3 acts directly on both HCC38 cells and MCF7 cells rather than stimulating the production of another vitamin D3 metabolite that is responsible for the effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 on apoptosis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, migration, and metastatic markers in these cells. The receptor that 24,25(OH)2D3 interacts with is a membrane receptor, and does not work through VDR 17,24–28,46. The results on the levels of PLD and PKC in the present study indicate the interaction of the estrogen receptor on the membrane modified the effect of 24,25(OH)2D3 on breast cancer cells.

The effect of 24,25(OH)2D3 on proliferation was very specific, since its enantiomer 24S,25(OH)2D3 had no effect. This is further supported by the observation that 1α,25(OH)2D3 did not have an effect on either MCF7 cells or HCC38 cells. Previous studies using other model systems have shown that 1α,25(OH)2D3 can regulate cancer cells directly via the VDR 47, suggesting that more than one mechanism may function in various breast cancers. 1α,25(OH)2D3 also has indirect effects on breast cancer via the immune system, but we did not test this in the present study. 25(OH)D3 did stimulate proliferation, which was measured after a 24 hour exposure to the vitamin D metabolites. Thus it is likely that the effect of this vitamin D metabolite was due to further metabolism to 24,25(OH)2D3 but not to 1,25(OH)2D3, based on the findings described above.

The connection between 24R,25(OH)2D3 and ERα66 has implications for many different cell types and tissues. Firstly, 24R,25(OH)2D3 has an established chondroprotective effect and may prevent bone resorption by limiting calcium efflux in cartilage and bone cells 48. Post-menopausal women have a higher incidence of osteoarthritis than men of similar ages 49,50, and the extremely low levels of circulating estradiol in post-menopausal women have been implicated in this discrepancy 50,51. Treatment with 24R,25(OH)2D3 has been proposed as a potential therapeutic for osteoarthritis patients, as 24R,25(OH)2D3 prevents oxidative damage and apoptosis in chondrocytes 19. However, all previous research on the chondroprotective effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 has previously been done in male chondrocytes 19, which have higher circulating estradiol than post-menopausal women and lower expression of ERα66 50,52. Further research on 24R,25(OH)2D3 and ERα66 should be done to ensure that the chondroprotective effects of 24R,25(OH)2D3 are clinically applicable to both men and women, and male and female chondrocytes may be an appropriate model to further investigate crosstalk between 24R,25(OH)2D3 and ERα.

Secondly, 24R,25(OH)2D3 is a naturally occurring ubiquitous metabolite of vitamin D3. Serum 24R,25(OH)2D3 is present at higher levels in the blood than 1α,25(OH)2D3, the more commonly studied active metabolite of vitamin D3 53. Women with breast cancer have been reported to take vitamin D3 supplements at a higher rate than the general population 4, and some of that supplemental vitamin D3 is metabolized into 24R,25(OH)2D3 54. Further investigation into the benefits of taking vitamin D3 supplements for patients with ERα66+ and ERα66- breast cancer needs to be conducted, as our results imply that women with ERα66- breast cancer may be aggravating their tumors by taking excess vitamin D3.

In summary, 24R,25(OH)2D3 modulates apoptosis and tumorigenicity in breast cancer cells through ER-mediated pathways. In ERα66-negative, ERα36-positive breast tumors, 24R,25(OH)2D3 increases tumor burden, migration, and metastasis, and may decrease survival. In ERα66-positive tumors, 24R,25(OH)2D3 induces apoptosis and reduces tumor burden. Our results show that expressing ERα66 in wild-type ERα66-negative HCC38 cells reverses the anti-apoptotic effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 and causes treatment with 24R,25(OH)2D3 to induce apoptosis. Silencing ESR1 in wild-type ERα66-positive MCF7 cells reduces ERα66 but not ERα36 and reduces the pro-apoptotic effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3, supporting a role for ERα36 in mediating the anti-apoptotic effect of this vitamin D metabolite. Our results with C2C12, an unrelated cell line, showed that the regulation of the 24R,25(OH)2D3 effect by these estrogen receptors is not limited to breast cancer cells; rather, treatment with 24R,25(OH)2D3 induced apoptosis in ESR1-overexpressing C2C12 cells. Our data show that ERα66 and ERα36 are modulators of the apoptotic effect of 24R,25(OH)2D3 in a diverse array of cell lines, and should inform diverse research areas such as the implications of vitamin D supplementation in breast cancer patients, the potential of 24R,25(OH)2D3 as a therapeutic in male vs. female osteoarthritis patients, and the value of measuring serum 25(OH)D3 as an indicator of vitamin D status and importance of local production of vitamin D metabolites in modulating the therapeutic effects of the hormone.

Supplementary Material

Implications:

These results suggest that 24R,25(OH)2D3, which is a major circulating metabolite of vitamin D, is functionally active in breast cancer and that the regulatory properties of 24R,25(OH)2D3 are dependent upon the relative expression of ERα66 and ERα36.

Acknowledgments

Services and products in support of the research project were generated by the Virginia Commonwealth University Cancer Mouse Models Core Laboratory, supported, in part, with funding from NIH-NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016059.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Freedman DM, Dosemeci M.& McGlynn K.Sunlight and mortality from breast, ovarian, colon, prostate, and non-melanoma skin cancer: A composite death certificate based case-control study. Occup. Environ. Med 59, 257–62 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbas S.et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of post-menopausal breast cancer--results of a large case-control study. Carcinogenesis 29, 93–99 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garland CF et al. The role of vitamin D in cancer prevention. Am. J. Public Health 96, 252–61 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poole EM et al. Postdiagnosis supplement use and breast cancer prognosis in the After Breast Cancer Pooling Project. Breast Cancer Res. treatment 139, 529–37 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scragg R.et al. Monthly high-dose vitamin D supplementation and cancer risk. JAMA Oncol. 4, e182178 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manson JE et al. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med 380, 33–44 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HJ et al. Vitamin D deficiency is correlated with poor outcomes in patients with luminal-type breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol 18, 1830–1836 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCullough ML et al. Dairy, calcium, and vitamin D intake and postmenopausal breast cancer risk in the cancer prevention study II nutrition cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 14, 2898–2904 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HJ et al. Changes in serum hydroxyvitamin D levels of breast cancer patients during tamoxifen treatment or chemotherapy in premenopausal breast cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 50, 1403–1411 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohr SB, Gorham ED, Kim J, Hofflich H.& Garland CF Meta-analysis of vitamin D sufficiency for improving survival of patients with breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 34, 1163–6 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chlebowski RT et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 100, 1581–91 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deluca HF Historical overview of vitamin D. in Vitamin D (eds. Feldman D, Pike JW & Adams JS.) 3–12 (Academic Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones G.& Prosser DE The activating enzymes of vitamin D metabolism (25- and 1α-hydroxylases). in Vitamin D (eds. Feldman D, Pike JW & Adams JS) 23–42 (Academic Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma A.et al. 24R,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishimura E.et al. Serum levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D in nondialyzed patients with chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamblyn JA, Jenkinson C, Larner DP, Hewison M.& Kilby MD Serum and urine vitamin D metabolite analysis in early preeclampsia. Endocr. Connect (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyan BD, Hurst-Kennedy J, Denison TA & Schwartz Z.24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [24R,25(OH)2D3] controls growth plate development by inhibiting apoptosis in the reserve zone and stimulating response to 1α,25(OH)2D3 in hypertrophic cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 121, 212–6 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyan BD, Sylvia VL, Dean DD & Schwartz Z.24,25(OH)2D3 regulates cartilage and bone via autocrine and endocrine mechanisms. Steroids 66, 363–374 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyan BD et al. 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 protects against articular cartilage damage following anterior cruciate ligament transection in male rats. PLoS One 11, e0161782 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bessler H.& Djaldetti M.1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulates the interaction between immune and colon cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother 66, 428–432 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyan BD, Wang L, Wong KL, Jo H.& Schwartz Z.Plasma membrane requirements for 1α,25(OH)2D3 dependent PKC signaling in chondrocytes and osteoblasts. Steroids (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doroudi M, Olivares-Navarrete R, Hyzy SL, Boyan BD & Schwartz Z.Signaling components of the 1α,25(OH)2D3-dependent Pdia3 receptor complex are required for wnt5a calcium-dependent signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 2365–75 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sylvia VL et al. Regulation of phospholipase D (PLD) in growth plate chondrocytes by 24R,25-(OH)2D3 is dependent on cell maturation state (resting zone cells) and is specific to the PLD2 isoform. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1499, 209–221 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsson D, Anderson D, Smith NM & Nemere I.24,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 binds to catalase. J. Cell. Biochem (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato A, Bishop JE & Norman AW Evidence for a 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3Receptor/Binding Protein in a Membrane Fraction Isolated from a Chick Tibial Fracture-Healing Callus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 244, 724–727 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato A, Seo EG, Einhorn TA, Bishop JE & Norman AW Studies on 24R,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3: Evidence for a nonnuclear membrane receptor in the chick tibial fracture-healing callus. Bone (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martineau C.et al. Optimal bone fracture repair requires 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its effector molecule FAM57B2. J. Clin. Invest (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizwicki MT et al. Identification of an alternative ligand-binding pocket in the nuclear vitamin D receptor and its functional importance in 1α,25(OH) 2-vitamin D3 signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeda Y.et al. Antitumor and other effects of 24R,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol in lewis lung carcinoma causing abnormal calcium metabolism in tumor-bearing mice. Oncology 205, 202–205 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikezaki S.et al. Chemopreventive effects of 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, a vitamin D3 derivative, on glandular stomach carcinogenesis induced in rats by N-methyl-N’-nitro-N- nitrosoguanidine and sodium chloride. Cancer Res. 56, 2767–70 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Höbaus J.et al. Impact of CYP24A1 overexpression on growth of colorectal tumour xenografts in mice fed with vitamin D and soy. Int. J. cancer 138, 440–50 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaudhri RA, Hadadi A, Lobachev KS, Schwartz Z.& Boyan BD Estrogen receptor-α 36 mediates the anti-apoptotic effect of estradiol in triple negative breast cancer cells via a membrane-associated mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 1–11 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaudhri RA, Schwartz N, Elbaradie K, Schwartz Z.& Boyan BD Role of ERα36 in membrane-associated signaling by estrogen. Steroids 81, 74–80 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaudhri RA et al. Membrane estrogen signaling enhances tumorigenesis and metastatic potential of breast cancer cells via estrogen receptor α 36 (ERα36). J. Biol. Chem 287, 7169–7181 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puchalapalli M.et al. NSG mice provide a better spontaneous model of breast cancer metastasis than athymic (nude) mice. PLoS One 11, 1–15 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb Y, Hermida-Matsumoto L.& Resh MD Inhibition of protein palmitoylation, raft localization, and T cell signaling by 2-bromopalmitate and polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem 275, 261–70 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahn SG et al. Prognostic factors for patients with bone-only metastasis in breast cancer. Yonsei Med. J 54, 1168–77 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lotz EM, Berger MB, Schwartz Z.& Boyan BD Regulation of osteoclasts by osteoblast lineage cells depends on titanium implant surface properties. Acta Biomater. 68, 296–307 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz N.et al. Estradiol receptor profile and estrogen responsiveness in laryngeal cancer and clinical outcomes. Steroids 142, 34–42 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischer D.et al. Vitamin D-24-hydroxylase in benign and malignant breast tissue and cell lines. Anticancer Res. 29, 3641–3645 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka Y, Castillo L, DeLuca HF & Ikekawa N.The 24 hydroxylation of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3. J. Biol. Chem 252, 1421–1424 (1977). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohyama Y.& Yamasaki T.Eight cytochrome P450s catalyze vitamin D metabolism. Front. Biosci 9, 3007–18 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lechner D, Kállay E.& Cross HS 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 downregulates CYP27B1 and induces CYP24A1 in colon cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 263, 55–64 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matilainen JM, Malinen M, Turunen MM, Carlberg C.& Väisänen S.The number of vitamin D receptor binding sites defines the different vitamin D responsiveness of the CYP24 gene in malignant and normal mammary cells. J. Biol. Chem 285, 24174–24183 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartz Z.et al. The effect of 24R,25-(OH)2D3 on protein kinase C activity in chondrocytes is mediated by phospholipase D whereas the effect of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 is mediated by phospholipase C. Steroids 66, 683–694 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz Z.et al. 24R,25-(OH)2D3 mediates its membrane receptor-dependent effects on protein kinase C and alkaline phosphatase via phospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase-1 but not cyclooxygenase-2 in growth plate chondrocytes. J. Cell. Physiol (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vanoirbeek E.et al. The anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory actions of 1,25(OH) 2 D 3. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ono T.et al. 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 promotes bone formation without causing excessive resorption in hypophosphatemic mice. Endocrinology 137, 2633–2637 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pan Q.et al. Characterization of osteoarthritic human knees indicates potential sex differences. Biol. Sex Differ 7, 27 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herndon JH Osteoarthritis in women after menopause. Menopause 11, 499–501 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koelling S.& Miosge N.Sex differences of chondrogenic progenitor cells in late stages of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 1077–1087 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elbaradie KBY, Wang Y, Boyan BD & Schwartz Z.Sex-specific response of rat costochondral cartilage growth plate chondrocytes to 17β-estradiol involves differential regulation of plasma membrane associated estrogen receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res 1833, 1165–1172 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young LR & Backus RC Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 concentrations in adult dogs are more substantially increased by oral supplementation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 than by vitamin D3. J. Nutr. Sci 25, 1–4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stubbs JR, Zhang S, Friedman PA & Nolin TD Decreased Conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 to 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 Following Cholecalciferol Therapy in Patients with CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 9, 1965–1973 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.