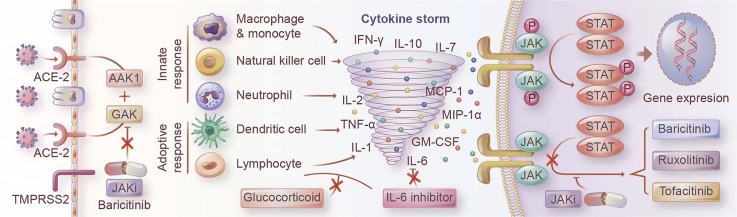

Graphical abstract

Keywords: JAK-STAT, JAK inhibition, Cytokines storm, Inflammation, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19

Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic continues to spread globally. The rapid dispersion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2 drives an urgent need for effective treatments, especially for patients who develop severe pneumonia. The excessive and uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory cytokines has proved to be an essential factor in the rapidity of disease progression, and some cytokines are significantly associated with adverse outcomes. Most of the upregulated cytokines signal through the Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway. Therefore, blocking the exaggerated release of cytokines, including IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFNα/β/γ, by inhibiting JAK/STAT signaling will, presumably, offer favorable pharmacodynamics and present an attractive prospect. JAK inhibitors (JAKi) can also inhibit members of the numb-associated kinase (NAK) family, including AP2-associated kinase 1 (AAK1) and cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK), which regulate the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) transmembrane protein and are involved in host viral endocytosis. According to the data released from current clinical trials, JAKi treatment can effectively control the dysregulated cytokine storm and improve clinical outcomes regarding mortality, ICU admission, and discharge. There are still some concerns surrounding thromboembolic events, opportunistic infection such as herpes zoster virus reactivation, and repression of the host’s type-I IFN-dependent immune repair for both viral and bacterial infection. However, the current JAKi clinical trials of COVID-19 raised no new safety concerns except a slightly increased risk of herpes virus infection. In the updated WHO guideline, Baricitinb is strongly recommended as an alternative to IL-6 receptor blockers, particularly in combination with corticosteroids, in patients with severe or critical COVID-19. Future studies will explore the application of JAKi to COVID-19 treatment in greater detail, such as the optimal timing and course of JAKi treatment, individualized medication strategies based on pharmacogenomics, and the effect of combined medications.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus underlying the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, has posed a great challenge to public health, economic, and social stability worldwide. At the time of writing, hundreds of million people are infected, with the death toll continuously growing. Effective therapy is a vast and unmet clinical need.

Most patients with COVID-19 experience an asymptomatic or mild-to-moderate respiratory disease characterized by fever, cough, and reduced levels of lymphocytes and/or natural killer cells in peripheral blood [1]. However, approximately 5% of patients develop severe cases characterized by acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multiple organ failure (MOF), and even death [2], [3], [4], [5]. Understanding the route of virus infection and the pathophysiological mechanisms of COVID-19 will help us effectively control the viral spread and prevent the disease, especially in severe cases.

There are two clinical phases of SARS-CoV-2 infection: viral infection and replication first, and the body’s immune response second [6]. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to zoonotic β-coronavirus; it infects humans by binding its antigen spike protein to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor. ACE-2 receptor is widely expressed in the type II alveolar cells, epithelium of the mouth, tongue, and upper airways, enabling SARS-CoV-2 to enter the target cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis with the help of the cellular protease TMPRSS2 [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Epithelial type-II cells are rich with ACE-2 receptor, which explains why pulmonary infection is the most prominent clinical manifestation.

The innate immune system senses RNA viruses through toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) and then activate downstream signaling effectors such as tumor-necrotic factor (TNF)-ɑ, interferon (IFN), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 [13]. An early and robust type-I IFN response, which activates the janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway, is critical for protecting against viral replication and spread by initiating transcription of hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes, including pro-inflammatory cytokines [13], [14], [15].

A practical and well-coordinated immune response is the host’s core defense against viral infection. While an excessive inflammatory innate response coupled with a dysregulated adaptive response may cause severe tissue damage both at the site of virus entry and at the systemic level [16]. Accumulating evidence suggested that dysregulated immune cells and molecular messengers released by them play a critical role in the pathophysiology of ARDS and MOF caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection [1], [17], [18], [5], [19]. Clinically, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10), and CCL3 were elevated in the plasma of patients, which could activate and attract macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils to inflammatory sites, resembling over-activation of innate immunity [1], [17]. IL-17, GM-CSF, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-12 expressed by T helper 1 (Th1), Th2, Th9, and Th17 cells would enhance the pro-inflammatory action of autoimmune responses [1], [20], [21], [22]. Among the cytokines implicated in COVID-19 associated cytokine storm, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IFN-γ, G-CSF, TNF-α, and GM-CSF transmit signals predominantly via JAK/STAT pathway. Some of these, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, were directly correlated with the severity of ARDS [23], [24], [25]. This hyper-inflammatory state produces oxidative stress that damages alveolar and endothelial cells in the lungs and facilitates the progression of MOF [5], [26]. Alleviating or diminishing the upregulated inflammatory response could provide a therapeutic advantage to COVID-19 patients and further improve clinical outcomes.

Therapeutic strategies that target the activated inflammatory response include cytokine monoclonal antibodies, inhibiting immune cell activation, and blocking cytokine-mediated inflammatory signal transduction [27], [28], [29]. JAK/STAT pathways transmit intracellular signals from the cell surface and participate in the cytokine-mediated immune overreaction, which eventually causes an excessive immune-inflammatory response [30]. In this review, we have recapitulated the clinical efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors (JAKi) in the treatment of COVID-19 and highlighted the clinical value and research prospect of such therapy.

2. JAK families

Cytokine defines an extensive range of soluble molecules that ensure effective intercellular communication for developmental and homeostatic immune processes, including host defense, inflammation, trauma, and cancer [31]. These extracellular molecules can signal to the nucleus by reaching membrane receptors and/or enzymes that can phosphorylate the intracellular portion (ICP) of membrane receptors, known as the janus kinases (JAKs) [32]. Membrane receptors can be divided into two classes based on whether they have intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity [33], [34]. Type I/II cytokine receptor superfamily does not possess enzymatic activities but relies on specific JAKs to transmit the signal inside the cell [30], [35], [36], [37].

2.1. Members and structure of the JAK family

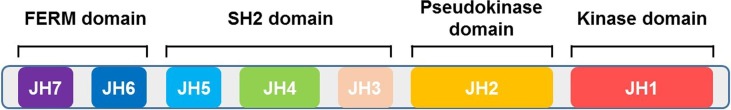

The human JAK family is comprised of four proteins, Jak1, Jak2, Jak3, and Tyk2, ranging in size from 120 to 140 kDa and consisting of seven conserved JAK homology (JH) domains [38], [39]. Jak1, Jak2, and Tyk2 are ubiquitously expressed, while Jak3 expression is restricted mainly to immune cells [40], [41], [42]. The JAK family proteins share four domains: the kinase domain (JH1), the pseudokinase domain (JH2), the SH2-like domain (JH3-JH5), and FERM (band-four-point-one ezrin radixin moesin) domain (JH6-JH7) [43], [44], [45] (Fig. 1 ). The kinase domain presents catalytic activity. Recent studies have suggested that the pseudokinase domain might have an essential regulatory function, which is required to auto-inhibit the JAK kinase [46], [47], [48]. The FERM domain plays essential roles in mediating interaction with the cytokine receptor subunits and regulating catalytic activity of the C-terminal kinase domain, while the SH2-like domain can facilitate associations with the cytokine receptors through providing scaffolding [49], [50], [51]. The common mechanism of action of current JAKi is to recognize and bind to the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site of the JH1 kinase domain in their active conformation [52], [53].

Fig. 1.

Schematic of JAK structural domains. The JAK family proteins share 4 domains: the kinase domain (JH1), the pseudokinase domain (JH2), the SH2-like domain (JH3-JH5), and FERM (band-four-point-one ezrin radixin moesin) domain (JH6-JH7).

2.2. JAK signaling pathway

When a type I/II cytokine receptor becomes bound by ligands, the active JAKs, working in pairs comprising either homodimeric or heterodimeric complexes, phosphorylate the tyrosines of ICP of membrane receptor and then the dock site of signal transmission and activator of transcription (STATs), another mediator of intercellular signaling following JAK phosphorylation. JAKs can also influence additional intercellular signaling pathways, such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK/ERK pathways, which are strong stimulater of cell growth, proliferation, and survival [54], [55], [56].

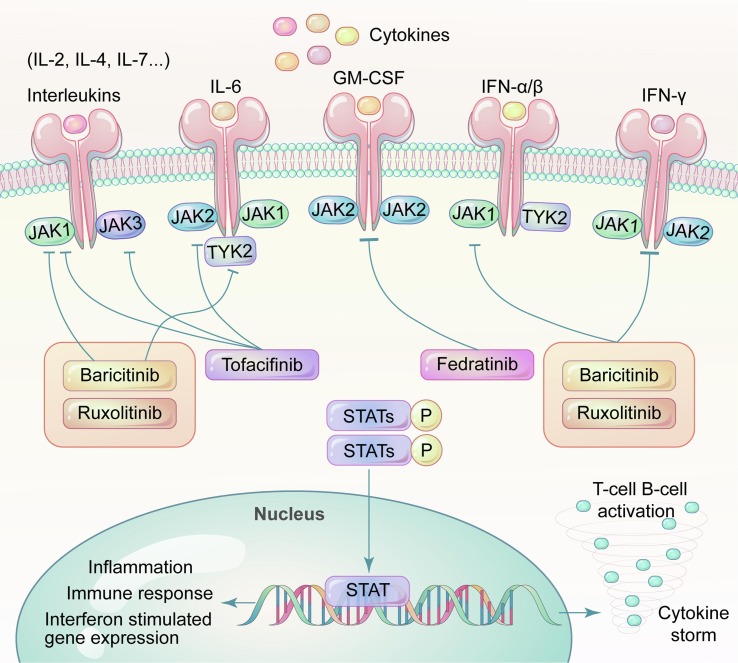

Seven types of STATs (STAT1 to 4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6) have been identified in mammals [57], [58]. Phosphorylated STATs, forming homodimers or heterodimers, migrate to the nucleus to induce and maintain immune responses via transcriptional regulation [37] (Fig. 2 ). These proteins constitute a rapid membrane-to-nucleus signaling transmission (JAK/STAT axis), which is involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and the physiological process of the immune system (Fig. 2) [37], [44], [59], [60], [61]. Different ligands (cytokine or growth factor) transduce their signals through specific sets of JAKs and STATs (Table 1 ) [60].

Fig. 2.

Cytokine storm consequent to SARS-CoV2 infection. The human JAK family, together with the STATs, primarily contribute to signaling transmission between extracellular receptors and the cell nucleus. Excessive COVID-19 associated cytokines bind to their receptors, leading to activation of JAKs and phosphorylation of downstream STATs.downstream Phosphorylated STATs regulate interferon induced gene expression, lymphocytes differentiation and proliferation, and participate in the cytokine-mediated immune overreaction, which eventually causes an inflammatory injury at the infected organ level, even at the systemic level.

Table 1.

Summary of JAKs and corresponding STATs as well as cytokines.

| JAKs | Associated STATs | Associated cytokines |

|---|---|---|

| JAK2 | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5 | IL-5, GH |

| JAK2 | STAT3 | Leptin |

| JAK2 | STAT5 | GM-CSF, EPO, PRL, TPO |

| JAK1, JAK2 | STAT1 | IFN-γ |

| JAK1, JAK2 | STAT3 | G-CSF |

| JAK1, JAK2 | STAT1, STAT3 | CLCF, IL-19, IL-20, IL-24/mda7 |

| JAK1, JAK2 | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5 | IL-31 |

| JAK1, JAK2 | STAT1, STAT4 | IL-35 (p35 + EBI3) |

| JAK1, JAK2 | STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5, STAT6 | TSLP |

| JAK1, JAK2 | STAT3, STAT5 | IL-3 |

| JAK1, JAK2, TYK2 | STAT3 | CT-1 |

| JAK1, JAK2, TYK2 | STAT1, STAT3 | IL-6, IL-11, LIF, OSM, CNTF |

| JAK1, JAK2, TYK2 | STAT3, STAT6 | IL-13 |

| JAK1, JAK2, TYK2 | STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5 | IL-27 (p28 + EBI3) |

| JAK1, JAK3 | STAT3, STAT5 | IL-7, IL-2, IL-9, IL-15, IL-21 |

| JAK1, JAK3 | STAT6 | IL-4 |

| JAK1, TYK2 | STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT5 | IL-20, IL-22, IL-28a, IL-28b, IL29 |

| JAK1, TYK2 | STAT1, STAT3 | IL-10, IL-26/AK155 |

| JAK1, TYK2 | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5 | IL-22/IL-TIF |

| JAK1, TYK2 | STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5, STAT6 | IFN-α, IFN-β |

| TYK2, JAK2 | STAT4 | IL-12 (p35 + p40) |

| TYK2, JAK2 | STAT1, STAT3, STAT4 | IL-23 (p19 + p40) |

GH = growth hormone; GM-CSF = granulocyte–macrophage colony stimulating factor; EPO = erythropoietin; PRL = prolactin; TPO = thrombopoietin; IFN = interferon; G-CSF = granulocyte colony stimulating factor; IL = interleukin; CT-1 = cardiotrophin-1; CLCF1 = recombinant cardiotrophin like cytokine factor 1; TSLP = recombinant human thymic stromal lymphopoietin; OSM = ontostatin M; CNTF = ciliary neurotrophic factor.

2.3. Dysregulation of JAK/STAT pathway and disease

JAK/STAT signaling dysfunction leads to immunodeficiencies in mouse models and humans. JAK gene targeting studies have established the critical role of JAKs in vivo. Jak1 knock-out mice exhibit a lethal perinatal phenotype; Jak2-/- mice exhibit a mid-gestational lethal phenotype attributed to defects in erythropoiesis and responses to cytokines such as members of the IL-2 family IL-3 and IFN-γ; Disruption of Jak3 demonstrates severe defects in lymphocyte development and activity [62], [63], [64], [65]. Loss-of-function or gain-of-function of the JAK/STAT pathway has also been observed in many immune-mediated diseases, lymphoproliferative disorders, and hematological malignancies, which characterized by uncontrolled proliferation and activation of T cell and macrophages [44], [48], [60], [66], [67]. High levels of serum pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, and IFN, have been proved to be a significant influencer in severe COVID-19 patients via JAK/STAT pathway [17], [68]. STAT3 is also known to mediate CD8+T cell stimulation, providing a greater immune response [69].

2.4. Therapeutic potential of JAK inhibitors

Given the pathogenic role of JAK/STAT signaling in the progression of COVID-19, a new generation of small molecule inhibitors, JAKi, have been developed to interrupt this signaling cascade in the treatment of immune-mediated disease. Baricitinib, Ruxolitinib, and Tofacitinib are the most studied inhibitors for COVID-19. They are all type I inhibitors (binding to active kinases and inhibiting them) with a relatively short half-life of 4 h for Ruxolitinib, 12.5 h for Baricitinib, and 3 h for Tafocitinib. Different JAKi inhibit different JAK isoforms, and the mechanism of action is not precisely the same [70], [71].

Baricitinib was initially an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [72]. Baricitinib strongly inhibits JAK1 and JAK2 enzymes (IC 50: 4.0–5.9 nM for JAK1 and 6.6–8.8 nM for JAK2), and it can also inhibit JAK3 (787 nM) and TYK2 (61 nM) in high concentrations [45], [61], [72], [73]. Both innate and adaptive immunity can be suppressed by Baricitinib due to blocking the signaling of GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-8, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-23 [74], [75], [76]. Moreover, Baricitinib was independently predicted to be effective for 2019-COVID via reducing the receptor-mediated viral endocytosis by artificial intelligence algorithms at clinically achievable serum concentrations [77], [78]. It has been shown to inhibit AP2-associated protein kinase-1 (AAK1) and, to a lesser degree, cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK), which may regulate the internal transport-related cell surface protein ACE-2 [79]. Its high affinity for AAK1 has been demonstrated uniquely among different JAKi in vitro assays[80], [81], [82]. In addition, recent studies have revealed that type I IFN and, to a lesser extent, type II IFN can upregulate ACE-2 expression. Baricitinib can efficiently prevent the IFN mediated increase in the expression of ACE-2, which may be beneficial in the early course of the COVID-19 [6], [83].

In 2011, Ruxolitinib was approved for myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) and steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease [84], [85]. Ruxolitinib has consistently demonstrated robust selective inhibition of JAK1 (3.3–6.4 nM) and JAK2 (2.8–8.8 nM) using enzymes and cell-based assays in vitro and in vivo [86]. The broad anti-inflammatory effects of Ruxolitinib were also observed in preclinical models and clinical studies. The immunomodulatory effect was reflected as suppressing IL-6, TNF-α, IL-12, IFN-γ, IL-18, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, CXCL-10, and phosphorylated STAT3, without affecting the peripheral proportion of CD4/CD8+ cells [87], [88], [89], [90]. Its ability to activate regulatory T lymphocyte can be considered as another mechanism for its immunosuppress activity [91]. The pharmacokinetic profile of Ruxolitinib is characterized by rapid oral absorption, a short terminal elimination half-life, and a concentration-dependent and reversible pharmacodynamic effect, which ensures flexibility and effectiveness in short-term therapy [92], [93].

Tofacitinib which inhibits JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3, is the first pan-JAKi to enter clinical trials for renal transplantation [94]. It inhibits mainly JAK1 (15 nM), JAK3 (45–55 nM), and to a lesser range the JAK2 (71–77 nM) and TYK2 (472–489 nM). It is a specifically potent JAK3 inhibitor, so its anti-inflammatory properties are due to its capacity to make JAKs irresponsive to multiple cytokines such as IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, and IL-21 [91], [95]. Theoretically, it may be more beneficial as it would not interact with the activation of IFNγ-mediated antibacterial immunity [96].

Overall, the SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers inflammation via the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, resulting in high levels of circulating chemokines, lymphocyte exhaustion, and uncontrolled cytokine storm especially in severe cases [13]. By blocking JAK/STAT signaling and subsequent production of cytokines, JAKi are expected to be a promising treatment for SARS-CoV-2 infection [97], [98]. Several clinical trials are investigating the effects of JAKi in the treatment of COVID-19, some of which have been completed with encouraging results.

3. Performance of JAK inhibitors in clinical trials

So far, there is no specific anti-viral treatment available for COVID-19. To target the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 and the role of cytokine storm in the progression of COVID-19 in severe cases, several anti-cytokine biologic therapies such as IL6 receptor antagonist, IL-1 receptor antagonist, TNF-α blocker, and JAK/STAT inhibitor, have been investigated in moderate-to-severe cases [99], [100], [101], [102]. We will summarize the relevant discoveries of the current registered clinical trials of JAKi, which may be an effective treatment option for COVID-19.

Forty-one studies listed under clinicaltrials.gov or chiCTR.org have been included; withdrawn studies have been excluded. The drugs tested include Baricitinib (N = 16), Ruxolitinib (N = 18), Tofacitinib (N = 4), and others (N = 3).

3.1. Baricitinib

Baricitinib is an oral selective JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor licensed to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA) that may block viral entry into pneumocytes, prevent cytokine storm, and restrain immune dysregulation in patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia [83], [103], [104], [105]. A total of 16 registered studies evaluated the therapeutic effects of Baricitinib (Table 2 ) on COVID-19 pneumonia.

Table 2.

Clinical trials investigating Baricitinib in treatment of COVID-19.

| Clinical trial identifier | Status | Study design | No of enrolled | Age(y) | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04401579 | Completed | double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ACTT-2) | 1033 | 18–99 | Baricitinib (4 mg/d) + RDV vs. Placebo + RDV | Time to recovery |

| NCT04390464 | Recruiting | Randomized, parallel arm, open-label (TACTIC-R) | 1167 | 18 ∼ | Baricitinib (4 mg/d) + SOC vs. Ravulizumab + SOC |

Time to the incidence of the composite endpoint of: death, mechanical ventilation, cardiovascular organ |

| NCT04358614 | Completed | Interventional | 12 | 12–85 | Baricitinib-4 mg/d | To assess the safety of Baricitinib combined with antiviral (lopinavir-ritonavir) in terms of serious or non-serious adverse events incidence rate. |

| NCT04362943 | Completed | Retrospective, observational, single-center cohort study |

576 | 70∼ | Baricitinib vs. Anakinra |

All-cause mortality |

| NCT04346147 | Active, not recruiting | Randomized, single-center, parallel assignment, open-label |

168 | 18∼ | Hydroxychloroquine + one of: Baricitinib (4 mg/d × 7 days) or Lopinavir/ritonavir or Imatinib |

Time to clinical improvement on 7-point ordinal scale |

| NCT04320277 | Not yet recruiting | Non randomized, before-after, single-center |

200 | 18∼ | Baricitinib (4 mg/d x14 days) + antiviral vs. antiviral and/or hydroxychloroquine |

ICU transfer |

| NCT04373044 | Terminated | Prospective, single-arm, two center, open label | 6 | 18∼ | Baricitinib (4 mg/d × 14 days) + one of: Hydroxychloroquine or Lopinavir/ritonavir/Remdesivir |

Death or mechanical ventilation at day 14 |

| NCT04321993 | Recruiting | Non randomized, multi-center, parallel assignment, open label |

800 | 18∼ | Baricitinib (2 mg/d x10 days) vs. SOC |

Clinical improvement on 7-point ordinal scale at day 15 |

| NCT04421027 | Completed | Randomized, double-Blind, placebo controlled, parallel assignment, interventional (COV-BARRIER) |

1585 | 18∼ | Baricitinib-4 mg/d vs. placebo | Cases needing: non-invasive ventilation, high-flow oxygen, invasive mechanical ventilation |

| NCT04393051 | Not yet recruiting | Randomized, multicentered, open-label, parallel assignment, interventional | 126 | 18∼ | Baricitinib- 4 mg or 2 mg/d for 14 days. vs. SOC |

The decrease in patients requiring invasive ventilation |

| NCT04399798 | Not yet recruiting | Single group, assignment, open-label, interventional | 13 | 18–74 | Baricitinib-4 mg/d for 7 days | Response to treatment: absence of moderate to severe oxygenation impairment |

| NCT04365764 | Recruiting | Cross sectional, case control, observational | 400 | no limit | Treatment including Baricitinib vs. patients are not given treatment. |

Composite of death and mechanical ventilation. |

| NCT04366206 | Recruiting | Prospective, cohort, observational | 143 | no limit | Treatment including Baricitinib vs. patients are not exposed to treatment or risk factor |

Composite of death and mechanical ventilation |

| NCT04970719 | Recruiting | Interventional, randomized, parallel, assignment | 382 | 18∼ | Baricitinib vs. Dexamethasone vs. Remdesivir |

Rescue treatment |

| NCT04640168 | Active, not recruiting |

Randomized, parallel assignment, interventional (ACTT-4) |

1010 | 18–99 | Baricitinib Dexamethasone Placebo Remdesivir |

The proportion of subjects not meeting criteria for one of the following two ordinal scale categories at any time: death; hospitalized, on invasive mechanical ventilation or ECMO |

| NCT04381936 | Recruiting | Randomized, controlled, open-label platform trial (RECOVER) | 8156 | no limit | Baricitinib 4 mg/d for 10 days vs. UC | 28-day mortality |

VDR = remdesivir; SOC = standard of care; ICU = intensive care unit; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The clinical benefit of Baricitinib in treating pneumonia induced by SARS-CoV-2 was first validated by a pilot study on 12 patients with moderate COVID-19 pneumonia, in which clinical and respiratory parameters significantly improved when Baricitinib (4 mg/d) was given for two weeks [104]. A large double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (NCT04401579, ACTT-2) enrolled 1,033 patients and delivered the results that Baricitinib with remdesivir was superior to remdesivir alone in reducing the median time to recovery (rate ratio for recovery, 1.16; 1.01 to1.32; p = 0.03) and improving clinical status (odds ratio, 1.3; 1.0 to 1.6). The benefit was even more apparent in patients receiving high-flow oxygen or noninvasive ventilation (rate ratio for recovery, 1.51; 1.10 to 2.08). While ACTT-2 did not detect pronounced differences in mortality between the group on the combination treatment and the group receiving remdesivir alone [106]. A phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial provided data related to overall survival (COV-BARRIER, NCT04421027). As demonstrated, Baricitinib plus standards of care (SOC) treatment were associated with significantly reduced mortality at 28 days (hazard ratio [HR] 0.57; 0.41–0.78]; p = 0.0018) and 60 days (HR 0.62; 0.47–0.83); p = 0.005), and the rate of adverse outcomes was similar between the two groups [107].

A combination of Baricitinib and corticosteroids showed significant improvement in pulmonary function compared with corticosteroids alone in moderate-to-severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia patients (improvement in oxygen saturation, 49; 22–77; p < 0.001) [108]. This conclusion was further confirmed by a randomized, controlled, open-label, platform trial RECOVERY study, which also demonstrated that a combination of Baricitinib with steroids had a 13% reduction in 28-day mortality for the treatment of COVID-19 (age-adjusted rate ratio 0.87; 0.77–0.98; p = 0.026, NCT04381936, RECOVERY) [109]. Another study demonstrated that an additional, single 8-mg oral loading dose of Baricitinib presented better clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, who need for intensive care and mechanical ventilation support [110].

Ongoing randomized, parallel, open-label trials (NCT04390464, TACTIC-R) will provide more information about Baricitinib in reducing the progression of COVID-19-related disease to organ failure or death compared with SOC alone [111].

3.2. Ruxolitinib

Ruxolitinib, an inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2 with selectivity against tyrosine kinase TYK2, was initially approved to treat neoplastic diseases [112], [113]. It also showed potential therapeutic benefits for severe immune-mediated diseases such as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and severe COVID-19 cases. Eighteen live and completed studies were registered to evaluate its efficacy (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Clinical trials investigating Ruxolitinib in treatment of COVID-19.

| Clinical trial identifier | Status | Study design | No. of enrolled | Age(y) | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChiCTR2000029580 | Completed | Single blind, randomized, parallel assignment | 35 | 18–75 | Ruxolitinib (5 mg bid) vs. placebo | Mortality; mechanical ventilation; duration of hospital stay; duration of ventilation; time to symptom or clinical improvement; time to viral clearance |

| NCT04338958 | Completed | Single arm, non-randomized, interventional | 105 | 18 ∼ | Ruxolitinib-10 mg bid increased to 20 mg bid for 7 days | Overall response rate in reversal of hyperinflammation |

| NCT04334044 | Completed | Single group assignment, open-label, interventional | 77 | 18 ∼ | Ruxolitinib- 5 mg bid | Recovery from pneumonia |

| NCT04377620 | Terminated | Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicentered, interventional | 211 | 12∼ | Ruxolitinib (5 mg bid) vs. Ruxolitinib (15 mg bid) + SOC | Proportion of participants who have died due to any cause |

| NCT04414098 | Not yet recruiting | Experimental, open-label prospective, single centered, add-on, interventional |

100 | 18∼ | Ruxolitinib- 5 mg bid up to 14 days and taken orally | Evaluation of Ruxolitinib efficiency in COVID-19 treatment |

| NCT04366232 | Terminated | Randomized, open label, parallel assignment, interventional | 2 | 18∼ | Ruxolitinib (5 mg bid up to 28 days + Anakinra vs. Anakinra vs. SOC |

CRP, Ferritinemia, Serum creatinine, AST/ALT, Eosinophils |

| NCT04362137 | Completed | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentered, interventional | 432 | 12∼ | Ruxolitinib- 5 mg bid for 14–28 days vs. placebo |

Proportion of patients who die, develop respiratory failure [require mechanical ventilation] or require ICU care |

| NCT04331665 | Terminated | Single arm, open-label, interventional | 3 | 12∼ | Ruxolitinib-10 mg bid x14days following this, 5 mg bid × 2 days and then 5 mg, qd × 1 day | The proportion of ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia who become critically ill the number of adverse events |

| NCT04361903 | Not yet recruiting | Cohort, retrospective, monocentric, non-profit observational |

18 | 18∼ | Ruxolitinib-20 mg bid in the first 48 h. | Patients avoiding mechanically assisted ventilation in ARDS occurring in COVID-19 patients |

| NCT04424056 | Not yet recruiting | Open-label, randomized, parallel assignment, interventional | 216 | 18–75 | Anakinra and Ruxolitinib vs. Tocilizumab and Ruxolitinib vs. SOC |

The number of days without mechanical ventilation at day 28 |

| NCT04374149 | Completed | Non-randomized, sequential assignment, open-label, interventional | 20 | 12–80 | Ruxolitinib (5 mg bid x14days) + TPE vs. TPE | CRP levels at baseline and day 14, cytokine levels at baseline and day 14 |

| NCT04359290 | Completed | Single group assignment, open-label, interventional | 15 | 18∼ | Ruxolitinib-10 mg bid (day1) up to 15 mg bid (day2-8) | Overall survival of COVID-19 patients |

| NCT04477993 | Terminated | Randomized, double-blind, parallel assignment, interventional (RUXO-COVID) | 5 | 18–95 | Ruxolitinib- 5 mg bid at days 0–14 vs. Placebo | Death, ICU admission, mechanical ventilation at day 14 |

| NCT04403243 | Recruiting | Randomized, open-label, parallel assignment, interventional | 70 | 18∼ | Colchicine vs. Ruxolitinib 5 mg vs. Secukinumab 150 mg/ml subcutaneous solution [COSENTYX] vs. standard therapy |

Change from baseline in clinical assessment score COVID 19 (CAS COVID 19) frame: baseline |

| NCT04348695 | Recruiting | Randomized, open-label, parallel assignment, interventional | 94 | 18∼ | Ruxolitinib-5 mg bid × 7 days and 10 mg bid for up to 14 days vs SOC | Cases developing severe respiratory failure |

| NCT04351503 | Recruiting | Retrospective, observational | 10,000 | no limit | Current treatments including Ruxolitinib | Identification of factors associated with infection, hospitalization, and requirement of ICU treatment |

| NCT04278404 | Recruiting | Prospective, observational | 5000 | ∼20 | Under studied drugs including Ruxolitinib | Clearance, half-life, volume of distribution, elimination rate constant, half-life |

| NCT04581954 | Recruiting | Randomized, parallel assignment, interventional |

456 | 18∼ | Ruxolitinib vs. Fostamatinib vs. SOC |

All-cause mortality |

SOC = standard of care; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; CRP = C-reactive protein; AST = aspartate transaminase; ALT = alanine transaminase; ICU = intensive care unit; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; TPE = therapeutic plasma exchange.

Rosée et al. prospectively stratified 14 patients with severe COVID-19 by the newly developed COVID-19 Inflammation Score (CIS) and gave Ruxolitinib as treatment (NCT04338958). In their study, 12/14 patients showed a significant reduction of CIS by more than 25% on day 7 and 11/14 patients obtained sustained clinical improvement [114]. Ruxolitinib not only potently reduced ARDS-associated inflammatory cytokine levels in plasma, but was also associated with rapid respiratory and cardiac improvement. It was reported that patients treated with Ruxolitinib (5 mg twice a day) + SOC achieved faster clinical improvement and significant CT improvement when compared with the SOC group in a multicenter randomized controlled trial (ChiCTR2000029580) [115]. Ruxolitinib was also well-tolerated and associated with improved cardiopulmonary function and clinical outcomes, probably by simultaneously turning off abnormal innate and adaptive immune responses in ARDS induced by COVID-19, even in elderly patients with high-risk factors (NCT04359290 and NCT01243944) [116], [117]. Another study of Ruxolitinib for the treatment of ARDS (RESPIRE, NCT04361903) suggested that Ruxolitinib administration resulted in a clinical improvement. A higher dose (20 mg bid in the first 48 h) in the early stage would improve clinical efficacy in reducing severe respiratory distress [118]. For those patients with no need for mechanical ventilation, compassionate use of Ruxolitinib (5 mg/twice daily) showed a significant reduction of inflammation biomarkers [119]. Initiating Ruxolitinib treatment immediately after respiratory symptoms begin to deteriorate, will achieve the best treatment result [118], [120]. The COVID-19 CIS obtained from clinical and laboratory markers will help to define the right time to initiate the drug [114].

A novel combination of Ruxolitinib and Eculizumab to treat ARDS induced by COVID-19 was investigated in a controlled study [121]. In this study, 17 consecutive cases of SARS-CoV-2-related ARDS treated with Ruxolitinib (10 mg/twice daily) + Eculizumabor (900 mg iv/ weekly) (n = 7) or the best available therapy (BAT, n = 10), and the results showed that patients treated with the combination therapy showed significantly improved respiratory symptoms. While the peripheral blood cell count was comparable between the two groups, and secondary infection was not observed in the experiment arm. In addition, lower level of circulating D-dimer was observed in the combination group compared with the BAT group.

There are several ongoing randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies to assess the efficacy and safety of Ruxolitinib at different dosages (NCT04362137, NCT04377620, etc.).

3.3. Tofacitinib and other JAK inhibitors

Tofacitinib, an orally administered selective inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK3 with functional selectivity for JAK2, is under investigation in 4 registered clinical studies (Table 4 ). Recently, a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (STOP-COVID, NCT04469114) conducted in Brazil revealed the significant advantages of Tofacitinib (10 mg bid) in reducing death or respiratory failure in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia through day 28 compared with placebo (risk ratio, 0.63; 0.41 to 0.97; p = 0.04) [122]. TD-0903 (Nezulcitinib) is a pan-JAK inhibitor. A randomized, parallel assignment study (NCT04402866) was designed to evaluate this new drug’s efficacy, safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics (Table 4). According to the early phase report, the overall mortality at day 28 was 33% in placebo-treated patients and 5% in nezulcitinib-treated patients [123]. There is another ongoing registered randomized, parallel assignment, interventional trial (NCT04404361), in which the efficacy and safety of Pacritinib, a selective JAK2 inhibitor, are evaluated in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 with or without cancer (Table 4). These results are worth anticipating.

Table 4.

Clinical trials investigating Tofacitinib and other JAKi in treatment of COVID-19.

| Clinical trial identifier | Status | Study design | No. of enrolled | Age(y) | Jaki | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04415151 | Terminated | Randomized, parallel assignment, interventional |

24 | 18–99 | Tofacitinib | Tofacitinib-10 mg bid followed by 5 mg bid for 0–14 days vs. Placebo |

Disease severity |

| NCT04469114 | Completed | Randomized, multicentered, double-blind, placebo controlled, interventional | 289 | 18∼ | Tofacitinib | Tofacitinib-10 mg vs. placebo | Death or respiratory failure at day 28 |

| NCT04390061 | Not yet recruiting | Randomized, multicentered, open-label, interventional | 116 | 18–65 | Tofacitinib | Tofacitinib (10 mg bid) vs. Hydroxychloroquine | Prevention of severe respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation |

| NCT04332042 | Not yet recruiting |

Prospective cohort study, single group assignment, open-label, interventional | 50 | 18–65 | Tofacitinib | Tofacitinib- 10 mg bid for 0–14 days. | Patients requiring the use of mechanical ventilation for PaO2/FIO2 greater than 150 |

| ChiCTR2000030170 | Completed | Interventional | 16 | 50–100 | Jacketinib | Routine standard therapy + Jacketinib | Severe novel coronavirus pneumonia group: TTCI [time window: 28 days] |

| NCT04404361 | Terminated | Randomized, parallel assignment, interventional |

200 | 18∼ | Pacritinib | Pacritinib vs. Placebo | Proportion of patients who progress to IMV and/or ECMO or death during the 28 days following randomization |

| NCT04402866 | Completed | Randomized, parallel assignment, interventional |

235 | 18–80 | TD-0903 | TD-0903 (pan-JAKi) vs. placebo |

Respiratory failure free days |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; PAO2 = pressure of oxygen; FIO2 = Fraction of inspiration; TTCI = time to clinical improvement; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

4. Safety of JAK inhibitors

The risk-benefit balance must be carefully considered when using pleiotropic immunomodulators such as JAKi. Despite the beneficial effects of JAKi in preventing viral invasion and controlling dysregulated inflammation, blocking the broad range of cytokine signals transmitted via JAK/STATs may be detrimental in some circumstances. The main concerns include delaying IFN-dependent viral clearance during acute viral infections, increasing vulnerability to secondary opportunistic infections, and thrombotic events.

4.1. Adverse events reported in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases

Inhibiting JAK-STAT signaling has been hypothesized to block downstream signals of inflammatory factors, including IFNα/β/γ, which play an essential role in responding to bacterial infection and curbing virus activity [4], [124], [125], [126], [127]. Increased risk of malignancies is the mainly concerning disadvantage of using Baricitinib for a long time [128], [129]. A significant increase in the risk of herpes zoster infection (relative risk 1.57; 95% CI, 1.04–2.37) was suggested in a meta-analysis comprising 66,159 patients with the immune-mediated inflammatory disease, who were exposed to JAKi long term [130]. While in registered randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, rates of infectious events are only mildly increased in JAKi-treated patients over eight to 24 weeks [131], [132], [133].

Several JAKi licensed for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases have FDA black box warnings for venous and arterial thrombotic events including ischemic stroke, pulmonary embolism, and deep venous thrombosis [134], [135].However, Ruxolitinib does not carry a venous thrombotic events warning. It has even been suggested to lower the inherently raised thrombotic risk in treatment for MPN [136]. A meta-analysis including 42 Phase II and III double-blinded randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of JAKi at licensed doses, involving 6,542 JAKi patient exposure years, showed that venous thromboembolism was unlikely to be substantially increased in those on JAKi therapy compared to placebo [137].

Other adverse events such as metabolism dysfunction, serious infections, cardiovascular events, and malignancy were not increased or mildly increased [138], [139], [140].

4.2. Safety profile of JAK inhibitors in clinical trials of COVID-19

Considering the proclivity to hypercoagulation in COVID-19 patients due to excessive inflammation, platelet activation, and endothelial dysfunction, whether JAKi would further increase the risk of thrombotic events was of particular concern [134], [141], [142], [143], [144]. Based on the current COVID-19 clinical trials data, no excess of thromboembolic events emerged in patients receiving JAKi [106], [137], [145]. Severe infections and thrombotic events were similar or even less occurred in the JAKi treatment group. The main adverse events recorded in COVID-19 clinical trials are summarized in Table 5 . Evidence from Baricitinib treatment in the RA population suggested that reducing the dose (2 mg/d) may help to reduce the risk of thrombosis [128]. Further data are anticipated from the TACTIC-R and COV-BARRIER studies.

Table 5.

Summary of adverse events of JAKi from registered COVID-19 clinical trials.

| Clinical trial identifier | JAKi |

Subjects (case vs. control or case only) |

Adverse event (case vs. control or case only) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04421027 | Baricitinib | n = 764 vs. n = 761 | serious adverse events (15% vs.18%) serious infection (9% vs.10%) venous thromboembolic events (3% vs.3%) major adverse cardiovascular events (1% vs. 1%) |

| NCT04401579 | Baricitinib | n = 515 vs. n = 518 | serious adverse events (16% vs. 21%) new infections (5.9% vs. 11.2%) |

| NCT04338958 | Ruxolitinib | n = 105 | grade 3 liver toxicity (n = 1) anemia grade 3 (n = 2) |

| NCT04361903 | Ruxolitinib | n = 18 | no drug related adverse events were observed |

| NCT04359290 | Ruxolitinib | n = 15 | adverse event (n = 2) |

| ChiCTR2000029580 | Ruxolitinib | n = 20 vs. n = 21 | hematological adverse events (65% vs. 57.1%) serious adverse events (0 vs. 19%) |

Other side effects of JAKi include anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and hyperlipidemia [146]. Therefore, JAKi are not recommended in the following situations: absolute neutrophil count less than 1 × 109 cells/L; absolute lymphocyte counts less than 0.5 × 109 cells/L; early asymptomatic infections; individuals not requiring hospital admittance [147]. These restrictions are also particularly important in severe COVID-19 cases that usually exhibit an exhausted lymphocyte phenotype. In a randomized trial of 43 patients in Wuhan, grade I to II anemia and thrombocytopenia were more common in the Ruxolitinib group. Compared with SOC, patients receiving Ruxolitinib had experienced a significantly shorter time before lymphocyte recovered [115]. However, further research data need to clarify the actual application situation in the real world.

In summary, JAKi are considered well tolerated with no new, serious safety signaling. However, information about the long-term adverse events and drug-related tumor onset is still lacking.

5. Discussion and perspectives

The incidence rate of COVID-19 increases over time, and the emergence of mutant strains makes the treatment more difficult. More efforts are being made to develop therapeutic strategies to suppress disease progression. Drug repurposing (also known as rediscovery) is an efficient way to accelerate the identification of drugs that can cure or prevent COVID-19. Significant interests are focused on the drugs, which are able to inhibit virus life circle and counteract the effects of virus infection [27], [99], [100], [148], [149]. No specific cure therapy for COVID-19 exists yet, and JAKi are the representative drugs capable of relieving systemic inflammatory symptoms and counteracting cytokine storm effects demonstrated in COVID-19. With the advantage of anti-inflammatory and anti-viral effects, convenient oral administration, and relatively short half-lives, JAKi are star molecules with great potential for clinical application [77], [82], [134].

A large sum of clinical evidence has represented significant therapeutic advances of JAKi in the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia, especially for severely ill patients. Whereas different JAKi inhibit JAK isoforms with different selectivity [52], [150]. The variable selectivity of JAK inhibitors is cell-dependent, dose-dependent, time-dependent, and not absolute, which may result in variability regarding their immunosuppressive effects and toxicity profile [151]. Generally, inhibiting JAK1 would block the broadest cytokine profile compared with other JAKs. JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2 were linked to erythropoiesis and thrombopoiesis, immune homeostasis, and anti-viral responses, respectively [52]. Direct comparisons from head-to-head clinical trials of JAKi are still lacking. From recent clinical experience, Baricitinib is the most extensively tested JAKi. Solid evidence from RCTs with a large sample size has demonstrated its efficacy in reducing inflammatory response, improving overall survival outcomes [106], [107], [109], [152]. The benefit of Baricitinib is derived from multiple mechanisms, including anti-inflammation, anti-viral, and preventing the IFN-mediated increase of ACE-2 expression. Ruxolitinib has the advantages of suitable tolerance, a short half-life. Some small non-controlled studies and meta-analyses suggested the positive effect of Ruxolitinib in improving inflammatory state and clinical symptoms [114], [116], [117], [120]. However, robust data from RCTs on survival have not been obtained until now. The recently reported randomized, double-blind, interventional phase 3 trial (STOP-COVID, NCT04469114) demonstrated that Tofacitinib treatment significantly reduced the risk of death or respiratory failure through day 28 [120]. Further evidence needs to be accumulated due to the relatively small sample size and impact of Tofacitinib on human B-cell differentiation and antibody production [122], [153]. Thus, in the newly updated WHO guideline for COVID-19, only Baricitinib is strongly recommended for severe or critical cases, especially in combination with corticosteroids [154].

Immune dysregulation is an important component of the pathophysiology of COVID-19, and remarkable successes such as the use of steroids or anti-cytokine therapies have been achieved (Table 6 ). Corticosteroids are considered a double-edged sword. Initially, they were only recommended in patients with SARS-CoV-2 without an alternative indication or presence of ARDS [155], [156], [157], [158], [159]. However, evidence showed that a short course of corticosteroids was beneficial and safe in critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 [156], [157], [160]. The results of RECOVERY showed that the use of dexamethasone (6 mg once daily administered for 10 days) has been found to be efficacious in reducing the mortality at 28 days for those patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation (36% reduction compared with usual care group) and receiving oxygen support without invasive mechanical ventilation (18% reduction compared with control) [161]. Similar protective effects of steroids were found in the REMAP-CAP study [162]. A living network meta-analysis included 23 randomized controlled trials showed that glucocorticoids were the only intervention with evidence to reduce mortality [163], [164]. An observational study enrolled patients with moderate to severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and evaluated the efficacy of Baricitinib plus corticosteroids in improving the pulmonary function. It showed that a combination of Baricitinib with corticosteroids was associated with a more significant improvement in pulmonary function compared with corticosteroids alone [108]. In this study, the D-dimer level was lower in the combination group. The recently released data from the RECOVER study confirmed the combined benefit of Baricitinb and corticosteroids in reducing mortality. In this study, 95% of patients were receiving corticosteroids, and the 28-day mortality is 12%[109]. Convincing evidence for the benefits of corticosteroids in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 disease has been provided, while it was not recommended by WHO in non-severe COVID-19 as the treatment brought no benefits [163].

Table 6.

Overview of approved immunomodulator treatments discussed in this paper.

| Immune-based therapy | Drug | Benefits | Negative indication | Clinical trial identifier | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | Hydrocortisone | improvement in organ support–free days within 21 days | / | NCT02735707 (REMAP-CAP) | patient admission to an ICU (n = 384) |

| Methylprednisolone | / | no significant effect on the primary outcome (composite of death, admission to the intensive care unit, or requirement for noninvasive ventilation) | GLUCOCOVID | hospitalized patients receiving oxygen without mechanical ventilation (n = 64) | |

| Dexamethasone | reduction in mortality at day 28 in patients on mechanical ventilation and those receiving supplementary oxygen | the mortality benefit was not found among those not receiving any respiratory support at randomization | NCT04381936 (RECOVERY) | hospitalized patient (n = 6425) | |

| Dexamethasone | improve the number of ventilator-free at day 28 | no significant difference in all-cause mortality, ICU-free days, mechanical ventilation duration at 28 days, or the 6-point ordinal scale at 15 days | NCT04327401 (CoDEX) | patients with moderate to severe ARDS in ICUs (n = 299) | |

| Hydrocortisone | / | no significantly in reducing treatment failure (death or persistent respiratory support) at day 21 | NCT02517489 (CAPE-COVID) | patients admitted to the ICU for COVID-19-related acute respiratory failure (n = 149) | |

| JAK inhibitor | Baricitinib (mainly) | reduction in mortality at day 28 | / | NCT04381936 (RECOVERY) | hospitalized patient (n = 8156) |

| Baricitinib | reduction in mortality at day 28 and day 60 | no significant reduction in the frequency of disease progression | NCT04421027 (COV-BARRIER) | hospitalized adults with COVID-19 (n = 1525) | |

| Baricitinib + remdesivir | reducing recovery time and accelerating improvement in clinical status (notably among those receiving high-flow oxygen or noninvasive ventilation) |

no significant difference in mortality at day 28 compared with remdesivir alone | NCT04401579 (ACTT2) | hospitalized adults with COVID-19 (n = 1033) | |

| Tofacitinib | lower risk of death or respiratory failure through day 28. | no significant difference in death from any cause | NCT04469114 (STOP-COVID) | hospitalized patients (n = 289) | |

| IL-6 antagonist | Tocilizumab | reduction in mortality with 28-days, reduce duration of hospitalization | no benefit was found among those not receiving invasive mechanical ventilation | NCT04381936 (RECOVERY) | severe ARDS hyperinflammatory states (N = 4116) |

| Tocilizumab and Sarilumab | Improving organ support–free days, 90-day survival, time to ICU, hospital discharge, and WHO ordinal scale at day 14 | / | NCT02735707 (REMAP-CAP) | patients need organ support in the ICU (n = 895) | |

| Tocilizumab | / | not effective for preventing intubation or death in moderately ill hospitalized patients with COVID-19 | NCT04356937 | SARS-CoV-2 infection, hyperinflammatory states (n = 243) |

ICU = intensive care unit; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; WHO = world health organization; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Apart from corticosteroids, anti-IL-6 therapies are another beneficial strategy available (Table 6). Tocilizumab is a monoclonal antibody acting as an IL-6 inhibitor that binds to membrane-bound and soluble IL-6 receptors. The first evidence was from a retrospective study of 21 patients in China. Tocilizumab (400 mg intravenously) was used in people with severe features of COVID-19. The results indicated that Tocilizumab caused plasma CRP to return to normal levels and improved lung function [165]. Anti-IL-6 strategies are beneficial according to the recently published large-scale RCTs (RECOVERY and REMAP-CAP) and meta-analysis, which demonstrated that Tocilizumab was beneficial in patients with severe and critical COVID-19, particularly in association with glucocorticoids [166], [167], [168]. Another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that Tocilizumab was ineffective for preventing intubation or death in moderately ill hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [99]. Sarilumab is also another inhibitor of IL-6; however, the clinical studies related to Sarilumab failed to consistently demonstrate its efficacy in clinical outcome prevention [167], [169]. Indeed, the pathogenesis of COVID-19 is highly complex. At least dozens of cytokines were found to be significantly elevated in patients. Blocking IL-6 alone may be over-simplistic to counteract the establishment of the immune/inflammatory/thrombotic vicious circle [170], [171], [172]. In addition, it is difficult to monitor the degree and duration of IL-6 blockades because of the long half-life of Mabs (2–3 weeks), which may have detrimental effects such as secondary infections [173], [174].

Clinical evidence on combination treatment has also emerged. Baricitinib, in combination with remdesevir, has shown to improve survival in COVID-19 patients, as demonstrated in ACTT2 [82]. Another small preliminary study evaluated the combination of Ruxolitinib and Eculizumab (an anti-C5a complement monoclonal antibody) to treat severe COVID-19 cases [121]. The results showed that the combination group had significantly improved PaO2 and PaO2/FiO2 ratio. Meanwhile, the two groups had similar adverse events, including secondary infection and thrombotic events. The safety of JAKi combined with MTX or other biologics such as Tocilizumab has been confirmed [175]; however, the efficacy is still under investigation [124], [176]. Numerous clinical trials are underway to explore the appropriate timing (NCT04361903), optimum administration dosage (NCT04377620), treatment course (NCT04414098), and combination with other agents such as Anakinra and Tocilizumab (NCT04366232). It is hoped that those controlled trials will contribute to establishing an optimal drug regimen of JAKi to reduce the mortality of COVID-19.

In the future, research should also focus on more precise applications of JAKi. The first-generation JAKi are pan-inhibitors that affect a broad spectrum of signaling pathways of cytokines. More and more efforts have been made to generate newer JAKi aiming to selectively target the chosen pathway to reduce the incidence of adverse events. However, it was not clear whether selective JAKi inhibitors will work better than non-selective drugs in the treatment of COVID-19. What is less clear is which particular JAKi and which route of administration will achieve the best effects with the most negligible toxicity. Currently approved JAKi are metabolized by CYP3A4 enzymes, and technology that permits genome-wide scanning may allow individualization of these drugs, thereby improving efficacy and safety. Pharmacogenomics and pharmacodynamics on JAKi and COVID-19 pneumonia will provide more evidence to identify the most benefited population and resolve drug-drug interaction problems.

Significant milestones have been reached for the severe and critical patients, but more evidence still needs to accumulate to prevent worsening of the patients with moderate disease but at high risk of progressing, and those critically ill patients with poor response to existing treatment options.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jin Huang: Writing – review & editing. Chi Zhou: Software. Jinniu Deng: . Jianfeng Zhou: Conceptualization.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the grants from National Science Foundation of China (Young Scientist Fund, No. 81800356). We thank all the study researchers.

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.L., Hui D.S.C., et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y., et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou T., Su T.T., Mudianto T., Wang J. Immune asynchrony in COVID-19 pathogenesis and potential immunotherapies. J Exp Med. 2020;217(10) doi: 10.1084/jem.20200674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owji H., Negahdaripour M., Hajighahramani N. Immunotherapeutic approaches to curtail COVID-19. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seif F., Aazami H., Khoshmirsafa M., Kamali M., Mohsenzadegan M., Pornour M., Mansouri D. JAK Inhibition as a New Treatment Strategy for Patients with COVID-19. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2020;181(6):467–475. doi: 10.1159/000508247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue Y., Tanaka N., Tanaka Y., Inoue S., Morita K., Zhuang M., Hattori T., Sugamura K. Clathrin-dependent entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into target cells expressing ACE2 with the cytoplasmic tail deleted. J. Virol. 2007;81(16):8722–8729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00253-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X., Chen P., Wang J., Feng J., Zhou H., Li X., Zhong W., Hao P. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020;63(3):457–460. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.-H., Nitsche A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280.e278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N., et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamilloux Y., Henry T., Belot A., Viel S., Fauter M., El Jammal T., Walzer T., Francois B., Seve P. Should we stimulate or suppress immune responses in COVID-19? Cytokine and anti-cytokine interventions. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020;19(7):102567. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crouse J., Kalinke U., Oxenius A. Regulation of antiviral T cell responses by type I interferons. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15(4):231–242. doi: 10.1038/nri3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider W.M., Chevillotte M.D., Rice C.M. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014;32:513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu B., Xu X., Wei H. Why tocilizumab could be an effective treatment for severe COVID-19? J. Transl. Med. 2020;18(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02339-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satarker S., Tom A.A., Shaji R.A., Alosious A., Luvis M., Nampoothiri M. JAK-STAT Pathway Inhibition and their Implications in COVID-19 Therapy. Postgrad. Med. 2021;133(5):489–507. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1855921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. Hlh Across Speciality Collaboration UK: COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banerjee S., Biehl A., Gadina M., Hasni S., Schwartz D.M. JAK-STAT Signaling as a Target for Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases: Current and Future Prospects. Drugs. 2017;77(5):521–546. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0701-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schett G., Sticherling M., Neurath M.F. COVID-19: risk for cytokine targeting in chronic inflammatory diseases? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20(5):271–272. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0312-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Josset L., Menachery V.D., Gralinski L.E., Agnihothram S., Sova P., Carter V.S., Yount B.L., Graham R.L., Baric R.S., Katze M.G. Cell host response to infection with novel human coronavirus EMC predicts potential antivirals and important differences with SARS coronavirus. mBio. 2013;4(3):e00165–00113. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00165-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryzhakov G., Lai C.C., Blazek K., To K.W., Hussell T., Udalova I. IL-17 boosts proinflammatory outcome of antiviral response in human cells. J. Immunol. 2011;187(10):5357–5362. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fajgenbaum D.C., June C.H. Cytokine Storm. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(23):2255–2273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2026131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akbari H., Tabrizi R., Lankarani K.B., Aria H., Vakili S., Asadian F., Noroozi S., Keshavarz P., Faramarz S. The role of cytokine profile and lymphocyte subsets in the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Life Sci. 2020;258:118167. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tay M.Z., Poh C.M., Renia L., MacAry P.A., Ng L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20(6):363–374. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ragab D., Salah Eldin H., Taeimah M., Khattab R., Salem R. The COVID-19 Cytokine Storm; What We Know So Far. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1446. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sultana J., Crisafulli S., Gabbay F., Lynn E., Shakir S., Trifiro G. Challenges for Drug Repurposing in the COVID-19 Pandemic Era. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:588654. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.588654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ismaila M.S., Bande F., Ishaka A., Sani A.A., Georges K. Therapeutic options for COVID-19: a quick review. J. Chemother. 2021;33(2):67–84. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2020.1868237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J., Xie B., Hashimoto K. Current status of potential therapeutic candidates for the COVID-19 crisis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz D.M., Bonelli M., Gadina M., O'Shea J.J. Type I/II cytokines, JAKs, and new strategies for treating autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016;12(1):25–36. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Channappanavar R., Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017;39(5):529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo Y., Alexander M., Gadina M., O'Shea J.J., Meylan F., Schwartz D.M. JAK-STAT signaling in human disease: From genetic syndromes to clinical inhibition. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021;148(4):911–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor S.S., Radzio-Andzelm E., Hunter T. How do protein kinases discriminate between serine/threonine and tyrosine? Structural insights from the insulin receptor protein-tyrosine kinase. FASEB J. 1995;9(13):1255–1266. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.13.7557015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris R., Kershaw N.J., Babon J.J. The molecular details of cytokine signaling via the JAK/STAT pathway. Protein Sci. 2018;27(12):1984–2009. doi: 10.1002/pro.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durham G.A., Williams J.J.L., Nasim M.T., Palmer T.M. Targeting SOCS Proteins to Control JAK-STAT Signalling in Disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019;40(5):298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rane S.G., Reddy E.P. Janus kinases: components of multiple signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2000;19(49):5662–5679. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garrido-Trigo A., Salas A. Molecular Structure and Function of Janus Kinases: Implications for the Development of Inhibitors. J. Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(Supplement_2):S713–S724. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harpur A.G., Andres A.C., Ziemiecki A., Aston R.R., Wilks A.F. JAK2, a third member of the JAK family of protein tyrosine kinases. Oncogene. 1992;7(7):1347–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schindler C., Levy D.E., Decker T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(28):20059–20063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnston J.A., Kawamura M., Kirken R.A., Chen Y.Q., Blake T.B., Shibuya K., Ortaldo J.R., McVicar D.W., O'Shea J.J. Phosphorylation and activation of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in response to interleukin-2. Nature. 1994;370(6485):151–153. doi: 10.1038/370151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witthuhn B.A., Silvennoinen O., Miura O., Lai K.S., Cwik C., Liu E.T., Ihle J.N. Involvement of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in signalling by interleukins 2 and 4 in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Nature. 1994;370(6485):153–157. doi: 10.1038/370153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kotyla P.J. Are Janus Kinase Inhibitors Superior over Classic Biologic Agents in RA Patients? Biomed. Res. Int. 2018;2018:7492904. doi: 10.1155/2018/7492904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tangye S.G., Pelham S.J., Deenick E.K., Ma C.S. Cytokine-Mediated Regulation of Human Lymphocyte Development and Function: Insights from Primary Immunodeficiencies. J. Immunol. 2017;199(6):1949–1958. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.A.V. Villarino, M. Gadina, J.J. O'Shea, Y. Kanno, SnapShot: Jak-STAT Signaling II, Cell 181(7) (2020) 1696-1696 e1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Clark J.D., Flanagan M.E., Telliez J.B. Discovery and development of Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for inflammatory diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57(12):5023–5038. doi: 10.1021/jm401490p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamaoka K., Saharinen P., Pesu M., Holt V.E., 3rd, Silvennoinen O., O'Shea J.J. The Janus kinases (Jaks) Genome Biol. 2004;5(12):253. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saharinen P., Takaluoma K., Silvennoinen O. Regulation of the Jak2 tyrosine kinase by its pseudokinase domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20(10):3387–3395. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3387-3395.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer S.C., Levine R.L. Molecular pathways: molecular basis for sensitivity and resistance to JAK kinase inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20(8):2051–2059. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leonard W.J., O'Shea J.J. Jaks and STATs: biological implications. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:293–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haan S., Margue C., Engrand A., Rolvering C., Schmitz-Van de Leur H., Heinrich P.C., Behrmann I., Haan C. Dual role of the Jak1 FERM and kinase domains in cytokine receptor binding and in stimulation-dependent Jak activation. J. Immunol. 2008;180(2):998–1007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wallweber H.J., Tam C., Franke Y., Starovasnik M.A., Lupardus P.J. Structural basis of recognition of interferon-alpha receptor by tyrosine kinase 2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21(5):443–448. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choy E.H. Clinical significance of Janus Kinase inhibitor selectivity. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58(6):953–962. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Musumeci F., Greco C., Giacchello I., Fallacara A.L., Ibrahim M.M., Grossi G., Brullo C., Schenone S. An Update on JAK Inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019;26(10):1806–1832. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180327093502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katz M., Amit I., Yarden Y. Regulation of MAPKs by growth factors and receptor tyrosine kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1773(8):1161–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee J.Y., Chiu Y.H., Asara J., Cantley L.C. Inhibition of PI3K binding to activators by serine phosphorylation of PI3K regulatory subunit p85alpha Src homology-2 domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(34):14157–14162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107747108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gadina M., Gazaniga N., Vian L., Furumoto Y. Small molecules to the rescue: Inhibition of cytokine signaling in immune-mediated diseases. J. Autoimmun. 2017;85:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Russell S.M., Tayebi N., Nakajima H., Riedy M.C., Roberts J.L., Aman M.J., Migone T.S., Noguchi M., Markert M.L., Buckley R.H., et al. Mutation of Jak3 in a patient with SCID: essential role of Jak3 in lymphoid development. Science. 1995;270(5237):797–800. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verhoeven Y., Tilborghs S., Jacobs J., De Waele J., Quatannens D., Deben C., Prenen H., Pauwels P., Trinh X.B., Wouters A., et al. The potential and controversy of targeting STAT family members in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020;60:41–56. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mertens C., Darnell J.E., Jr. SnapShot: JAK-STAT signaling. Cell. 2007;131(3):612. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Shea J.J., Plenge R. JAK and STAT signaling molecules in immunoregulation and immune-mediated disease. Immunity. 2012;36(4):542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xin P., Xu X., Deng C., Liu S., Wang Y., Zhou X., Ma H., Wei D., Sun S. The role of JAK/STAT signaling pathway and its inhibitors in diseases. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;80:106210. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodig S.J., Meraz M.A., White J.M., Lampe P.A., Riley J.K., Arthur C.D., King K.L., Sheehan K.C., Yin L., Pennica D., et al. Disruption of the Jak1 gene demonstrates obligatory and nonredundant roles of the Jaks in cytokine-induced biologic responses. Cell. 1998;93(3):373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neubauer H., Cumano A., Muller M., Wu H., Huffstadt U., Pfeffer K. Jak2 deficiency defines an essential developmental checkpoint in definitive hematopoiesis. Cell. 1998;93(3):397–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nosaka T., van Deursen J.M., Tripp R.A., Thierfelder W.E., Witthuhn B.A., McMickle A.P., Doherty P.C., Grosveld G.C., Ihle J.N. Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking Jak3. Science. 1995;270(5237):800–802. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomis D.C., Gurniak C.B., Tivol E., Sharpe A.H., Berg L.J. Defects in B lymphocyte maturation and T lymphocyte activation in mice lacking Jak3. Science. 1995;270(5237):794–797. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O'Shea J.J., Holland S.M., Staudt L.M. JAKs and STATs in immunity, immunodeficiency, and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368(2):161–170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Milner J.D., Vogel T.P., Forbes L., Ma C.A., Stray-Pedersen A., Niemela J.E., Lyons J.J., Engelhardt K.R., Zhang Y., Topcagic N., et al. Early-onset lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity caused by germline STAT3 gain-of-function mutations. Blood. 2015;125(4):591–599. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-602763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang X., Zhang Y., Qiao W., Zhang J., Qi Z. Baricitinib, a drug with potential effect to prevent SARS-COV-2 from entering target cells and control cytokine storm induced by COVID-19. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;86:106749. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hojyo S., Uchida M., Tanaka K., Hasebe R., Tanaka Y., Murakami M., Hirano T. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm. Regen. 2020;40:37. doi: 10.1186/s41232-020-00146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levy G., Guglielmelli P., Langmuir P., Constantinescu S. JAK inhibitors and COVID-19. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2022;10(4) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roda G., Dal Buono A., Argollo M., Danese S. JAK selectivity: more precision less troubles. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;14(9):789–796. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2020.1780120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fridman J.S., Scherle P.A., Collins R., Burn T.C., Li Y., Li J., Covington M.B., Thomas B., Collier P., Favata M.F., et al. Selective inhibition of JAK1 and JAK2 is efficacious in rodent models of arthritis: preclinical characterization of INCB028050. J. Immunol. 2010;184(9):5298–5307. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bruland O., Fluge O., Immervoll H., Balteskard L., Myklebust M., Skarstein A., Dahl O. Gene expression reveals two distinct groups of anal carcinomas with clinical implications. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;98(7):1264–1273. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mitchell T.S., Moots R.J., Wright H.L. Janus kinase inhibitors prevent migration of rheumatoid arthritis neutrophils towards interleukin-8, but do not inhibit priming of the respiratory burst or reactive oxygen species production. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017;189(2):250–258. doi: 10.1111/cei.12970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karonitsch T., Beckmann D., Dalwigk K., Niederreiter B., Studenic P., Byrne R.A., Holinka J., Sevelda F., Korb-Pap A., Steiner G., et al. Targeted inhibition of Janus kinases abates interfon gamma-induced invasive behaviour of fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57(3):572–577. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kubo S., Nakayamada S., Sakata K., Kitanaga Y., Ma X., Lee S., Ishii A., Yamagata K., Nakano K., Tanaka Y. Janus Kinase Inhibitor Baricitinib Modulates Human Innate and Adaptive Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1510. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Richardson P., Griffin I., Tucker C., Smith D., Oechsle O., Phelan A., Rawling M., Savory E., Stebbing J. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):e30–e31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sorrell F.J., Szklarz M., Abdul Azeez K.R., Elkins J.M., Knapp S. Family-wide Structural Analysis of Human Numb-Associated Protein Kinases. Structure. 2016;24(3):401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eberl H.C., Werner T., Reinhard F.B., Lehmann S., Thomson D., Chen P., Zhang C., Rau C., Muelbaier M., Drewes G., et al. Chemical proteomics reveals target selectivity of clinical Jak inhibitors in human primary cells. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):14159. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50335-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stebbing J., Krishnan V., de Bono S., Ottaviani S., Casalini G., Richardson P.J., Monteil V., Lauschke V.M., Mirazimi A., Youhanna S., et al. Mechanism of baricitinib supports artificial intelligence-predicted testing in COVID-19 patients. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020;12(8):e12697. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202012697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sanchez G.A.M., Reinhardt A., Ramsey S., Wittkowski H., Hashkes P.J., Berkun Y., Schalm S., Murias S., Dare J.A., Brown D., et al. JAK1/2 inhibition with baricitinib in the treatment of autoinflammatory interferonopathies. J. Clin. Invest. 2018;128(7):3041–3052. doi: 10.1172/JCI98814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stebbing J., Phelan A., Griffin I., Tucker C., Oechsle O., Smith D., Richardson P. COVID-19: combining antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatments. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(4):400–402. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stebbing J., Sanchez Nievas G., Falcone M., Youhanna S., Richardson P., Ottaviani S., Shen J.X., Sommerauer C., Tiseo G., Ghiadoni L., et al. JAK inhibition reduces SARS-CoV-2 liver infectivity and modulates inflammatory responses to reduce morbidity and mortality. Sci. Adv. 2021;7(1) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Verstovsek S., Kantarjian H., Mesa R.A., Pardanani A.D., Cortes-Franco J., Thomas D.A., Estrov Z., Fridman J.S., Bradley E.C., Erickson-Viitanen S., et al. Safety and efficacy of INCB018424, a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363(12):1117–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Verstovsek S., Mesa R.A., Gotlib J., Levy R.S., Gupta V., DiPersio J.F., Catalano J.V., Deininger M., Miller C., Silver R.T., et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366(9):799–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]