Abstract

Background:

Foreign-born Black and Latina women on average have higher birthweight infants than their US-born counterparts, despite generally worse socioeconomic indicators and prenatal care access, i.e. ‘immigrant birthweight paradox’ (IBP). Residence in immigrant enclaves and associated social-cultural and economic benefits may be drivers of IBP. Yet, enclaves have been found to have higher air pollution, a risk factor for lower birthweight.

Objective:

We investigated the association of immigrant enclaves and children’s birthweight accounting for prenatal ambient air pollution exposure.

Methods:

In the Boston-based Children’s HealthWatch cohort of mother-child dyads, we obtained birthweight-for-gestational-age z-scores (BWGAZ) for US-born births, 2006–2015. We developed an immigrant enclave score based on census-tract percentages of foreign-born, non-citizen, and linguistically-isolated households statewide. We estimated trimester-specific PM2.5 concentrations and proximity to major roads based residential address at birth. We fit multivariable linear regressions of BWGAZ and examined effect modification by maternal nativity. Analyses were restricted to non-smoking women and term births.

Results:

Foreign-born women had children with 0.176 (95% CI: 0.092, 0.261) higher BWGAZ than US-born women, demonstrating the IBP in our cohort. Immigrant enclave score was not associated with BWGAZ, even after adjusting for air pollution exposures. However, this association was significantly modified by maternal nativity (pinteraction = 0.014), in which immigrant enclave score was positively associated with BWGAZ for only foreign-born women (0.090, 95% CI: 0.007, 0.172). Proximity to major roads was negatively associated with BWGAZ (−0.018 per 10m, 95% CI: −0.032, −0.003) and positively correlated with immigrant enclave scores. Trimester-specific PM2.5 concentrations were not associated with BWGAZ.

Significance:

Residence in immigrant enclaves was associated with higher birthweight children for foreign-born women, supporting the role of immigrant enclaves in the IBP. Future research of the IBP should account for immigrant enclaves and assess their spatial correlation with potential environmental risk factors and protective resources.

Keywords: Immigrants, Race and Ethnicity, Maternal and Child Health, Health inequality, Air Pollution, Immigrant enclaves, Birthweight

Introduction

Immigrants are a rapidly growing population in the United States (US). By the year 2065, immigrants and subsequent generations will account for 88% of the country’s growth or approximately 103 million people [1]. As such, research that investigates drivers of perinatal health outcomes among immigrants is critical for shaping the health of future generations.

Low birthweight is a leading cause of infant mortality and morbidity in the US and associated with learning, social, and motor developmental delays and chronic diseases later in life [2]. Approximately 8.2% of babies in the US are low birthweight (<2,500 grams) and 9.4% are preterm (<37 weeks) [2]. Racial/ethnic disparities in low birthweight are well-documented, with Black and Latina mothers having a higher risk of low birthweight children than White mothers [3]. However by nativity status, Latina and Black foreign-born mothers tend to have a lower risk than their US-born counterparts, on average, despite generally worse socioeconomic indicators (e.g. lower educational attainment, lower household income, limited English proficiency) [4–8]. This phenomenon is often termed the ‘immigrant birthweight paradox’.

The immigrant birthweight paradox (IBP) has been attributed to residence in immigrant enclaves, which are spatially identifiable areas with a high concentration of foreign-born residents, social capital, and economic opportunities [9]. Previous studies have documented positive birth outcomes for foreign-born women living in immigrant/ethnic enclaves [10–12]. Maternal residence in these areas could promote favorable birthweight outcomes through the mechanisms of increased social networks and capital that facilitate access to health, social, and financial resources; direct access to ethnic-specific, linguistically-accessible, and culturally-competent services; and familial, cultural, and/or community norms that facilitate positive health practices during pregnancy [5,10,13–15]. In addition, residence in enclaves has been associated with healthier behaviors among women, such as nutritious diets and lower prevalence of smoking and alcohol use [16–18]. However, other studies have found null effects of immigrant enclaves on birthweight [19–21]. Differences in study findings could in part be attributed to prenatal environmental exposures that have not been accounted for in these prior studies.

Hazardous environmental exposures are known risk factors for lower birthweight and commonly omitted in studies of the IBP and immigrant enclaves. Immigrant enclaves are usually spatially clustered within urban areas and in gateway cities that also have worse environmental conditions, including higher levels of air pollution. Studies have documented higher concentrations of ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5), traffic-related air pollution, air-toxic lifetime cancer risk clusters, and Superfund sites in geographic areas that also have with a high concentration of immigrant residents [22–26]. Specifically, prenatal exposure to PM2.5 and traffic-related air pollutants are consistent risk factors for lower birthweight [27–33] and can induce oxidative stress and inflammation that restrict in-utero growth [34–35]. As such, prenatal exposure to higher levels of ambient air pollution may attenuate the positive effects of residence in immigrant enclaves on perinatal health outcomes, and thus should be further explored.

The objective of our study is to investigate the association of maternal residence in immigrant enclaves and birthweight-for-gestational-age z-scores (BWGAZ) accounting for prenatal ambient air pollution exposure. In addition, we examine whether maternal nativity status modifies this relationship. Our cohort consists of predominantly Black and Latina mother-child dyads from major cities in Massachusetts (MA). We restrict our analyses to non-smoking women given that smoking is a significant behavioral risk factor of lower birthweight [17,18] and less prevalent among foreign-born women, both in our cohort (9%) and nationally [36]. Our conceptual model can be found in Supplemental Data Figure S1.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study population is a retrospective cohort of mother-child dyads based in Boston, MA from Children’s HealthWatch (CHW). CHW is an ongoing clinical sentinel study monitoring the health and well-being of young children and their families across five US cities [37]. Mother-child dyads were recruited between 2009–2015 from the Boston Medical Center (BMC) pediatric Emergency Department. Eligibility was based on child’s age (0 to 48 months), primary caregiver status, ability to speak English or Spanish, and MA residency. Mothers were not approached if children were critically ill or injured at the time of visit [38]. Participant surveys about sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics were retrospectively linked to children’s electronic medical record (EMR) based on the child’s medical record number, sex, date of birth, and date of CHW visit. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the Boston University Medical Campus IRB prior to data collection.

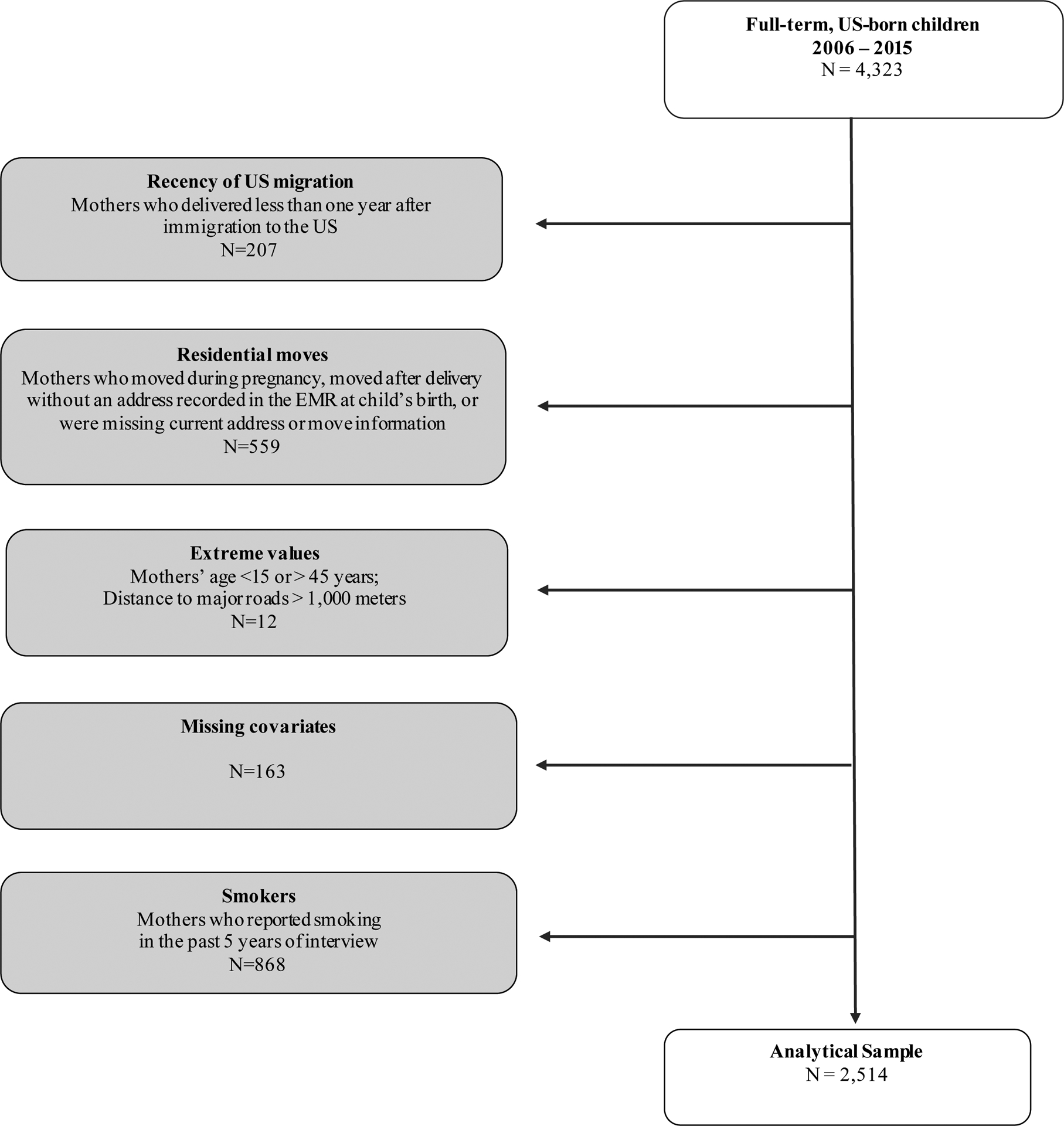

We restricted our study population to US-born, full-term births (i.e. gestational ages 37 to 42 weeks) between 2006–2015. We excluded pre-term (<37 weeks) and post-term (>42 weeks) births due to potential differences in the effect of prenatal exposures during these gestational periods [38,39]. We also excluded participants without information about maternal nativity, child birthweight, or residential address. To minimize potential confounding, we restricted our sample to women who delivered between the ages of 15–45 years and reported no smoking in the past 5 years prior to study visit. To ascertain prenatal exposure, we used residential address recorded in the EMR at the time of the child’s birth. For dyads missing address information at birth, we used the first reported address in the EMR. To minimize exposure misclassification, we excluded mother-child dyads that reported moving anytime during pregnancy; dyads that reported moving in the past year of the CHW survey and did not have an address recorded in the EMR at child’s birth; and dyads in which the mothers recently immigrated to the US within one year of delivery. We also excluded dyads missing data on maternal race/ethnicity, air pollution concentrations, and census-tract percent in poverty, and the few dyads with distances to a major road beyond 1,000 meters (i.e. extreme values in our cohort). Our final analytical sample consisted of 2,514 mother-child dyads (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Analytical sample selection, Boston-based Children’s HealthWatch cohort, 2006–2015.

Immigrant Enclave Score

We created an immigrant enclave score measure using estimates from the US American Community Survey (ACS) for percent foreign-born populations, percent non-US citizen populations, and percent non-English speaking/linguistically-isolated households in MA at the census-tract level. To account for temporal differences, we used five-year ACS estimates from 2006–2010 and 2011–2015 and linked this data to our cohort based on the child’s birth year (e.g. children born between 2006 and 2010 were assigned the ACS 2006–2010 data) and census tract of residence. Since there was not a standardized measure of immigrant enclave to our knowledge, our approach was based on methods from Finch et al. (2007) [10] and consistent with other studies using population density measures at the census-tract level [20,21].

We treated ACS variables as effect indicators [40] and evaluated their relationship with the latent factor of immigrant enclave using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in the R lavaan package [41]. We took the cubed root of each variable to satisfy the CFA normality assumption and constrained factors to a mean of 0 and a variance of 1. A CFA model was fit separately for the ACS 2006–2010 and 2011–2015 data. Fit statistics for both CFA models indicated good model fit: Comparative Fit Index for both = 1.0; Tucker-Lewis Index for both = 1.0; root mean square error of approximation for both <0.01; chi-squareACS 2006–2010 = 4483.9; and chi-squareACS 2011–2015 = 4609.8. In addition, our immigrant enclave measure had a high Cronbach’s alpha (≥ 0.94) and average interitem correlation (≥ 0.84) which suggested good reliability and internal consistency. Additional information can be found in Supplemental Data Tables S1 and S2.

Birthweight-for-gestational-age z-scores (BWGAZ)

Information about birthweight (grams) and gestational age (weeks) were obtained from EMRs and the CHW survey. Values from each data source were highly correlated (rbirthweight = 0.97 and rgestational age = 0.95) and thus, we used EMR values as the default and CHW imputed values when EMR data was missing [38]. Gestational age was determined based on the date of last menstrual period or ultrasound records. We calculated sex-specific, modified birthweight-for-gestational-age z-scores (BWGAZ) according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines [42], which were based on the World Health Organization’s growth standard charts for children under two years [43]. Gestational age cut-points for each trimester were in accordance with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) definition for the first (0–13 and 6/7 weeks), second (14 and 0/7 weeks to 27 and 6/7 weeks), and third (28 weeks to birth) trimesters [44]. The BWGAZ measure represents the degree of deviation from the median birthweight of the reference population matched on sex and gestational age characteristics [42]. At birth, a z-score of 0 would correspond to 3,530 grams for boys and 3,399 grams for girls [45]. We chose BWGAZ as the outcome measure because it accounted for gestational age and potential non-linear growth patterns [46]. In addition, BWGAZ has better statistical properties and less measurement error compared to categorical measures of birthweight [46]. Previous studies of prenatal air pollution exposure have also used BWGAZ [29,46–48].

Ambient Air Pollution Measures

Prenatal PM2.5 exposure and road distance measures were linked to EMR residential addresses at birth (71%) or first reported address in the EMR (29%). Maternal residential addresses were cleaned and geocoded to parcels in ArcMap version 10.6 (ESRI, ArcGIS, Redlands, CA, USA). There were minimal P.O. boxes or incomplete addresses (<1%) and unmatched addresses (3.6%) [49].

We calculated average PM2.5 concentrations (μg/m3) for each trimester of pregnancy to differentiate periods of fetal growth. Methods to generate PM2.5 averages have been previously described [30,49]. In brief, validated ambient PM2.5 averages at 1-kilometer (km)-squared grid resolution were generated based on daily aerosol optical depth (AOD) satellite data. AOD data were calibrated using a combination of ambient PM2.5 measurements, land use regression, and meteorological variables. Daily PM2.5 predictions were linked to participants’ residential address based on the closest 1-km2 grid cell and then averaged for each trimester.

Road distance (meters) was calculated as the Euclidean horizontal distance from the residential parcel to the nearest A1 and A2 major roads (e.g. primary roads, interstate and non-interstate highways, major roads without access restrictions). State road network data were obtained from the MA Department of Transportation 2018 road shapefiles [50].

Maternal Nativity and Race/Ethnicity

Information about self-reported maternal nativity status (foreign-born [FB], US-born [USB]), immigration characteristics (e.g. duration of US residency, countries of origin), and race/ethnicity (Latina, Black, White, and Other) were obtained from the CHW survey. Mothers born in Puerto Rico were categorized as US-born. Mothers were asked about their Hispanic, Latina, or Spanish ethnicity (Yes/No/Don’t know or Refused) separately from their race (multiple categories allowed). Women were categorized as Latina if they reported ‘Yes’ to the ethnicity question regardless of race. Women who responded ‘No’ to this question were categorized as Black, White, or Other if they selected ‘Black or African American’, ‘White or Caucasian’, and other or multiple race categories, respectively.

Covariates

Potential confounders considered were maternal demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, pregnancy risk factors, and housing instability based on prior literature [6,10,12,20,37,49,51, 53]. This included CHW survey data on maternal age at delivery (centered at mean 27.2), marital status (single/not married/widowed vs. married [reference]), educational attainment (no college vs. college [reference]), any homelessness during pregnancy (yes/no), public/subsidized housing during pregnancy (yes/no), and use of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC] during pregnancy (yes/no). We controlled for census-tract percentage of persons age 18 to 64 living in poverty (centered at mean 21.1%) as a proxy for neighborhood socioeconomic status. This data came from the ACS 2006–2010 and 2011–2015 five-year files and were linked to our cohort based on census tract residence and child’s birth year. We also controlled for the season and year of child’s birth to account for temporal trends. Maternal education and marital status were excluded in the final models for parsimony. They were poorly associated with the outcome (beta coefficients < 0.01, p ≥ 0.89), and their exclusion from final models did not change the coefficient magnitude of the main predictors by more than 10% (data not shown). Four covariates had missing data: maternal age [0.7%], WIC participation during pregnancy [0.5%], homelessness during pregnancy [6.4%], and public/subsidized housing during pregnancy [5.8%]. We imputed missing values under the missingness at random (MAR) assumption using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) in the mice R package [54], specifying 100 rounds of imputation. Results were similar for models with and without imputed values (data not shown), and therefore, presented results were based on the imputed dataset.

Statistical Analyses

We generated descriptive statistics overall and by nativity. Significant differences by nativity status were evaluated using chi-square tests for categorical variables and Welch’s two-sample t-tests or Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests for normal and non-normal continuous variables, respectively.

We ran multivariable linear regression models to test the association of immigrant enclave score and BWGAZ, and sequentially adjusted for trimester-specific PM2.5 concentrations and road proximity. Q-Q plots were used to confirm normality of residuals. Model comparison was conducted using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), with lower AIC scores indicating better fit. We considered a linear mixed-effect model with a random intercept for census tract to account for potential geographic clustering of BWGAZs. However, the variance of the random intercept was negligible (<0.0001) and there were little improvements in model fit compared to an ordinary least squares (OLS) model (AICmixed-effect = 6681, AICOLS = 6683). Therefore, results presented were from OLS models.

In each model, we adjusted for first, second, and third trimester average PM2.5 concentrations simultaneously to account for their correlations (Table S2), as this approach was shown to be less biased [52]. Road proximity was poorly correlated with PM2.5 averages across trimesters (Table S2). We checked for non-linearity of continuous predictors using generalized additive models (GAMs) with penalized cubic splines. Immigrant enclave score, trimester-specific PM2.5 concentrations, road proximity, and census-tract percent in poverty were linearly associated with BWGAZ. For distance to major roads, we stratified mothers into two groups - those living within a 100m buffer from a major road and those living beyond 100m - to account for slope differences in each stratum and consistent with a previous study [31]. We also tested for effect modification of maternal nativity on the association of immigrant enclave and BWGAZ using an interaction term. To examine the relationship between immigrant enclave score and environmental measures (i.e. trimester-specific PM2.5 averages and road distance), we ran GAMs with a penalized cubic spline for immigrant enclave score and adjusted for season and year of child’s birth.

In sensitivity analyses, we evaluated the robustness of our findings to potential exposure misclassification of maternal residence during pregnancy. We ran our final models excluding mother-child dyads without a known EMR address at the time of child’s birth (n=726). We also excluded dyads with low birthweight (<2,500 grams) or macrosomia (>4,000 grams) children (n=306). To assess geographic heterogeneity, we excluded mothers living outside of the greater Boston metropolitan area (n=39). Lastly, we tested for effect modification by child’s sex.

All statistical analyses were conducted in R Studio/R 3.5.1 (R Studio, Boston, MA). All testing was conducted with a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. We reported robust standard errors from the R sandwich package and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Population Characteristics

Sociodemographic, birthweight, and neighborhood characteristics of our study population are described in Table 1. Approximately 52% of mothers were foreign-born and 49% self-identified as Black and 39% as Latina. Most mothers were interviewed in English (81%), have not attended college (56%), and reported WIC participation during pregnancy (86%). Compared to US-born mothers, foreign-born mothers were older (mean 29 vs. 25 years), more likely to be married (51% vs. 29%), and less likely to have attended college (38% vs. 51%). They were also less likely to be homeless (6% vs. 12%) and live in public/subsidized housing (21% vs. 42%) while pregnant (p <0.001). Most foreign-born mothers immigrated from the countries of El Salvador, Haiti, Cape Verde, and the Dominican Republic. Mean BWGAZ at child’s birth was −0.22, corresponding to 3,310 grams. Children of foreign-born mothers had better birthweight outcomes than those of US-born mothers (−0.13 vs. −0.31 BWGAZ; 3,360 vs. 3,260 grams) (p <0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, birthweight. and neighborhood characteristics by maternal nativity status, Boston-based Children’s HealthWatch cohort, 2006–2015 (N=2,514)

| All Mothers (N=2,514) |

US-Born Mothers (N=1,213) |

Immigrant Mothers (N=1,301) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Characteristics, n (%) | p 1,2 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | < 2.2e-16 | |||

| Black | 1,240 (49.3%) | 659 (54.3%) | 581 (44.7%) | |

| Latina | 972 (38.7%) | 349 (28.8%) | 623 (47.9%) | |

| White | 179 (7.1%) | 146 (12.0%) | 33 (2.5%) | |

| Other | 123 (4.9%) | 59 (4.9%) | 64 (4.9%) | |

| Language of interview | < 2.2e–16 | |||

| English | 2,047 (81.4%) | 1,181 (97.4%) | 866 (66.6%) | |

| Spanish | 467 (18.6%) | 32 (2.6%) | 435 (33.4%) | |

| Length of time in the US | NA | |||

| US-born | 1,213 (48.2%) | 1,213 (100%) | NA | |

| <5 years in the US | 144 (5.7%) | NA | 144 (11.1%) | |

| 5–10 years in the US | 565 (22.5%) | NA | 565 (43.4%) | |

| 11+years in the US | 506 (20.1%) | NA | 506 (38.9%) | |

| Unknown | 86 (3.4%) | NA | 86 (6.6%) | |

| Top countries/regions of origin | NA | |||

| United States - 50 states | 1,138 (45.3%) | 1,138 (93.8%) | NA | |

| United States - Puerto Rico | 75 (3.0%) | 75 (6.2%) | NA | |

| El Salvador | 233 (9.3%) | NA | 233 (17.9%) | |

| Haiti | 188 (7.5%) | NA | 188 (14.5%) | |

| Cape Verde | 141 (5.6%) | NA | 141 (10.8%) | |

| Dominican Republic | 136 (5.4%) | NA | 136 (10.5%) | |

| Educational status | 1.00e–13 | |||

| Never/Elementary/Some High school | 571 (22.7%) | 203 (16.7%) | 368 (28.3%) | |

| High School Grad or GED | 833 (33.1%) | 395 (32.6%) | 438 (33.7%) | |

| Tech/College/Graduate/Masters | 1,110 (44.2%) | 615 (50.7%) | 495 (38.0%) | |

| Marital status | < 2.2e–16 | |||

| Single/Never-married | 1,198 (47.7%) | 731 (60.3%) | 467 (35.9%) | |

| Separate/Divorced/Widowed | 309 (12.3%) | 134 (11.0%) | 175 (13.5%) | |

| Married/Partnered/Cohabitation | 1,007 (40.1%) | 348 (28.7%) | 659 (50.7%) | |

| Age at delivery | < 2.2e–16 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27.2 (6.31) | 25.3 (6.05) | 29.1 (5.98) | |

| WIC participation during pregnancy | 8.98e–06 | |||

| Yes | 2,160 (85.9%) | 1,003 (82.7%) | 1,157 (88.9%) | |

| No | 354 (14.1%) | 210 (17.3%) | 144 (11.1%) | |

| Public/subsidized housing during pregnancy | < 2.2e–16 | |||

| Yes | 778 (30.9%) | 509 (42.0%) | 269 (20.7%) | |

| No | 1,736 (69.1%) | 704 (58.0%) | 1,032 (79.3%) | |

| Homelessness anytime during pregnancy | 8.38e–09 | |||

| Yes | 221 (8.8%) | 148 (12.2%) | 73 (5.6%) | |

| No | 2,293 (91.2%) | 1,065 (87.8%) | 1,228 (94.4%) | |

| Children’s Characteristics | p 1 | |||

| Birthweight-for-gestational age z-score | 5.22e–07 | |||

| Mean (SD) | −0.218 (0.913) | −0.313 (0.896) | −0.130 (0.921) | |

| Birthweight (grams) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3,310 (486) | 3,260 (481) | 3,360 (485) | 6.30e–07 |

| Categories | ||||

| Low birthweight (<2,500 grams) | 108 (4.3%) | 67 (5.5%) | 41 (3.2%) | 1.03e–03 |

| Normal (2,500–4,000 grams) | 2,208 (87.8%) | 1,067 (88.0%) | 1,141 (87.7%) | |

| Macrosomia (>4,000 grams) | 198 (7.9%) | 79 (6.5%) | 119 (9.1%) | |

| Birthweight-for-gestational age percentile (%) | 1.47e–06 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 41.5 (26.9) | 38.8 (26.2) | 43.9 (27.3) | |

| Child’s sex | 0.24 | |||

| Male | 1,364 (54.3%) | 643 (53.0%) | 721 (55.4%) | |

| Female | 1,150 (45.7%) | 570 (47.0%) | 580 (44.6%) | |

| Neighborhood Social-Contextual Factors (Census-tract level) | p 1 | |||

| Immigrant enclave score | < 2.2e–16 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.24 (0.69) | 1.08 (0.67) | 1.40 (0.69) | |

| Linguistically isolated households^ (%) | < 2.2e–16 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 45.6 (15.3) | 42.7 (14.0) | 48.2 (15.8) | |

| Foreign-born Populations (%) | < 2.2e-16 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 32.4 (12.4) | 29.3 (10.7) | 35.2 (13.1) | |

| Non-US citizen Populations (%) | < 2.2e–16 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 18.0 (11.6) | 15.0 (8.0) | 20.9 (13.5) | |

| Percent in poverty † (%) | < 2.2e–16 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 21.1 (11.4) | 23.1 (12.4) | 19.2 (10.1) | |

| Neighborhood Environmental Exposures | p 2,3 | |||

| First Trimester PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 0.64 | |||

| Median [Min, Max] | 9.16 [5.24, 16.6] | 9.16 [5.24, 15.9] | 9.16 [5.44, 16.6] | |

| Second Trimester PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 0.31 | |||

| Median [Min, Max] | 9.01 [5.05, 16.5] | 9.05 [5.05, 15.6] | 8.98 [5.99, 16.5] | |

| Third Trimester PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 0.57 | |||

| Median [Min, Max] | 8.85 [5.04, 18.2] | 8.84 [5.19, 17.1] | 8.86 [5.04, 18.2] | |

| Proximity to major roads (meter) | 0.34 | |||

| Median [Min, Max] | 90.6 [2.61, 943] | 90.7 [2.61, 942] | 89.6 [2.61, 943] | |

| Categorical | ||||

| <50 m | 821 (32.7%) | 377 (31.1%) | 444 (34.1%) | 0.39 |

| 50–100 m | 549 (21.8%) | 276 (22.8%) | 273 (21.0%) | |

| 101–200 m | 675 (26.8%) | 328 (27.0%) | 347 (26.7%) | |

| 201+ m | 469 (18.7%) | 232 (19.1%) | 237 (18.2%) | |

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. Abbreviations: SD = Standard deviation, NA = not applicable.

Black, White, and Other race categories refer to mothers who were not Hispanic, Latina, or Spanish.

Statistical tests:

Welch’s two-sample t-test;

Pearson chi-square test;

Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test.

Linguistically-isolated households: No one age 14+ years old speaks English-only or speaks English “very well”.

Among whom poverty status is determined.

Neighborhood Social-contextual and Environmental Factors

Compared to US-born mothers, foreign-born mothers on average lived in census tracts with a higher immigrant enclave score (1.40 vs. 1.08) (p <0.001); higher percentages of linguistically-isolated households (48% vs. 43%) and non-US citizens (21% vs. 15%); and lower percentages of residents in poverty (19% vs. 23%) (p<0.001) (Table 1). Additional characteristics by immigrant enclave score categories can be found in Table S3.

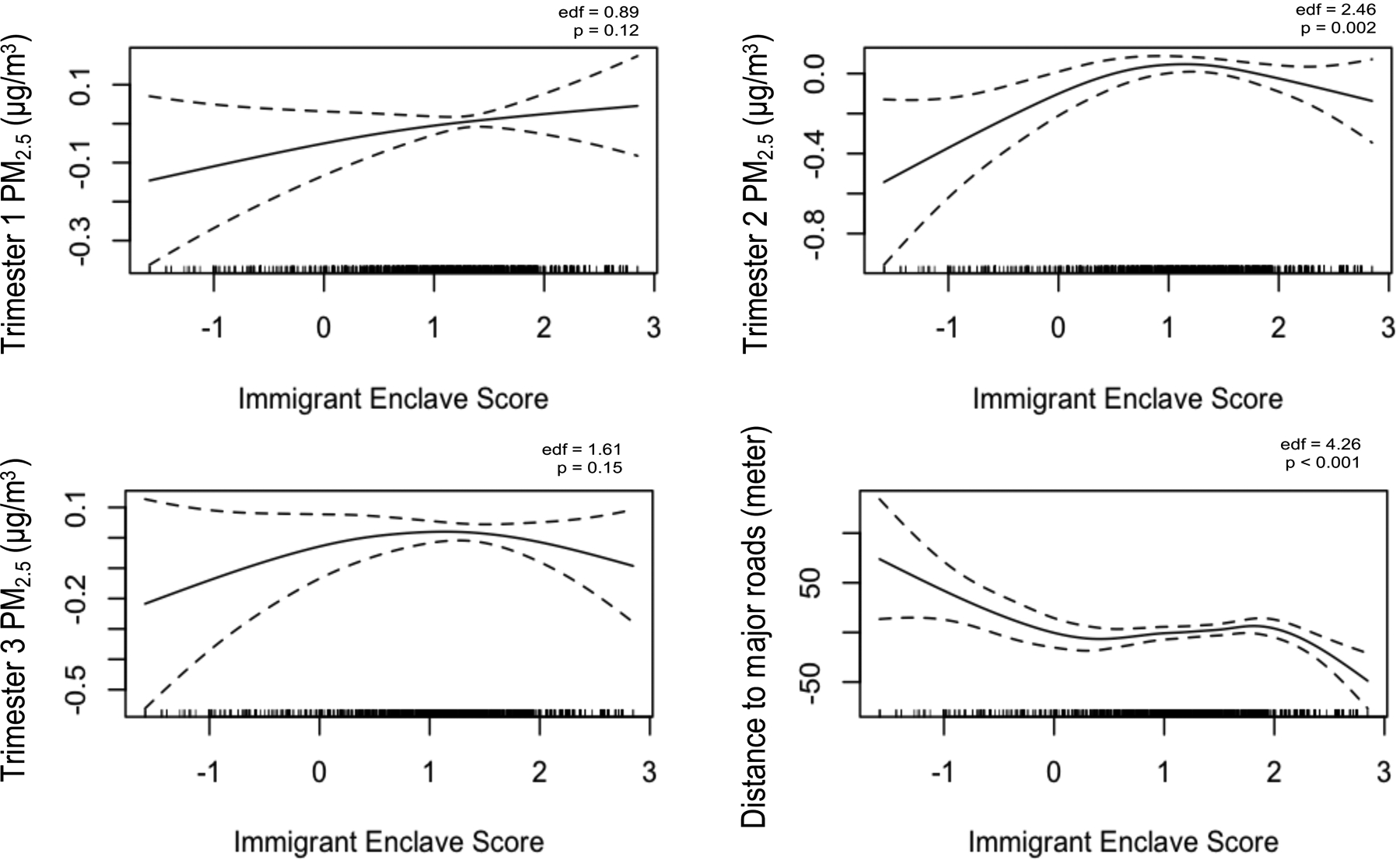

Median ambient PM2.5 concentrations ranged from 9.16 (range: 5.24–16.6) μg/m3 in the first trimester to 8.85 (range: 5.04–18.2) μg/m3 in the third trimester, while median distance to major roads was 90.6 (range: 2.61 to 943) meters (Table 1). The distribution of PM2.5 concentrations and distance to major roads were similar by maternal nativity status (p ≥ 0.31). Immigrant enclave score was not linearly correlated with trimester-specific PM2.5 concentrations and distance to major roads (Spearman ρ = |<0.10|) (Table S2). However, evaluation of the response functions indicated non-linear relationships between immigrant enclave score and second trimester PM2.5 (positive trend, p = 0.002) and distance to major roads (negative trend, p <0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Response functions of immigrant enclave score on the change in average first, second, and third trimester PM2.5 concentrations (μg/m3) and distance to major roads (meter), Boston-based Children’s HealthWatch cohort, 2006–2015 (N=2,514). Models adjusted for season and year of birth.

Predictors of BWGAZ

In multivariable models, immigrant enclave score had a positive but non-significant association with BWGAZ, even after adjusting for ambient air pollution sources (beta: 0.016, 95% CI: −0.039, 0.071) (Table 2, Model 3). The adjustment of road proximity slightly increased the coefficient of immigrant enclave score by a mean BWGAZ of 0.003 (Table 2, Models 1 vs. 2b). Proximity to a major road was associated with a lower mean BWGAZ: −0.018 per 10m (95% CI: −0.032, −0.003) for mothers living within a 100m buffer, and −0.003 per 10m (95% CI:−0.005, 0.002) for mothers living further away (Table 2, Model 3). Exposure to PM2.5 concentrations across the three trimesters were not significantly associated with BWGAZ.

Table 2.

Adjusted mean differences in birthweight-for-gestational-age z-scores, Boston-based Children’s HealthWatch cohort, 2006–2015 (N=2,514)

| Model 1 | Model 2a Adjust for PM2.5 |

Model 2b Adjust for Road Proximity |

Model 3 Adjust for PM2.5 + Road Proximity |

Model 4 Model 3 + Interaction |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | 95% Cl | Beta | 95% Cl | Beta | 95% Cl | Beta | 95% Cl | Beta | 95% Cl | |

| −29.83 | (−64.23,4.57) | −39.24 | (−90.78,12.29) | −28.37 | (−64.81, 3.24) | −37.33 | (−88.84,14.18) | −36.84 | (−88.38,14.71) | |

| Immigrant Enclave Score | 0.014 | (−0.041,0.068) | 0.013 | (−0.042,0.067) | 0.017 | (−0.038,0.072) | 0.016 | (−0.039,0.071) | −0.055 | (−0.131,0.022) |

| Foreign-born Status | 0.177 | (0.093,0.262) | 0.176 | (0.092,0.261) | 0.177 | (0.091, 0.260) | 0.176 | (0.092,0.261) | 0.015 | (−0.137,0.168) |

| Maternal Race/Ethnicity (ref: Black) | ||||||||||

| Latina | 0.023 | (−0.058,0.104) | 0.024 | (−0.058,0.105) | 0.025 | (−0.057, 0.106) | 0.026 | (−0.056,0.107) | 0.011 | (−0.072,0.094) |

| White | 0.363 | (0.206,0.519) | 0.364 | (0.206,0.521) | 0.360 | (0.201, 0.514) | 0.360 | (0.203,0.518) | 0.334 | (0.176,0.492) |

| Other | −0.047 | (−0.197,0.104) | −0.041 | (−0.193,0.11) | −0.053 | (−0.203, 0.102) | −0.048 | (−0.201,0.106) | −0.045 | (−0.198,0.109) |

| PM2.5 concentrations (per 10 μg/m3) | ||||||||||

| First Trimester Average | -- | -- | 0.243 | (−0.057,0.543) | -- | -- | 0.238 | (−0.060,0.538) | 0.230 | (−0.069,0.529) |

| Second Trimester Average | -- | -- | −0.056 | (−0.350,0.239) | -- | -- | −0.055 | (−0.350,0.240) | −0.054 | (−0.349,0.241) |

| Third Trimester Average | -- | -- | −0.071 | (−0.367,0.225) | -- | -- | −0.073 | (−0.369,0.222) | −0.067 | (−0.036,0.228) |

| Proximity to major roads (per 10 m) | ||||||||||

| Live within 100 m of road | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.018 | (−0.032, −0.003) | −0.018 | (−0.032, −0.003) | −0.018 | (−0.033, −0.003) |

| Live beyond 100 m of road | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.003^ | (−0.006,0.003) | −0.003^ | (−0.005, 0.002) | −0.003 | (−0.006,−0.00003) |

| Covariates | ||||||||||

| Age at delivery (centered, years) | 0.009 | (0.003,0.016) | 0.009 | (0.003,0.015) | 0.009 | (0.003,0.015) | 0.009 | (0.003,0.015) | 0.009 | (0.003,0.015) |

| WIC participation during pregnancy | 0.043 | (−0.068,0.155) | 0.042 | (−0.069,0.154) | 0.045 | (−0.066,0.157) | 0.045 | (−0.067,0.156) | 0.044 | (−0.067,0.156) |

| Homelessness during pregnancy | −0.142 | (−0.272,−0.011) | −0.142 | (−0.273,−0.012) | −0.138 | (−0.268,−0.008) | −0.138 | (−0.269,−0.008) | −0.132 | (−0.262,−0.001) |

| Public/subsidized housing during pregnancy | 0.053 | (−0.031,0.137) | 0.051 | (−0.033,0.135) | 0.055 | (−0.029,0.139) | 0.053 | (−0.030,0.137) | 0.061 | (−0.023,0.145) |

| Population in poverty (centered, %) | 0.122 | (−0.198,0.443) | 0.124 | (−0.196,0.444) | 0.089 | (−0.235,0.413) | 0.092 | (−0.232,0.416) | 0.119 | (−0.205,0.443) |

| Interaction: Immigrant Enclave Score × Foreign-born | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.134 † | (0.027,0.241) |

p-interaction = 0.014.

Note: Bold indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

= marginal significance (p = 0.05 – 0.07). Models adjusted for year and season of child’s birth.

Abbreviations: Beta = Estimated mean difference in z-scores; 95% CL = 95% Confidence limit.

Black, White, and Other race categories refer to mothers who were not Hispanic, Latina, or Spanish.

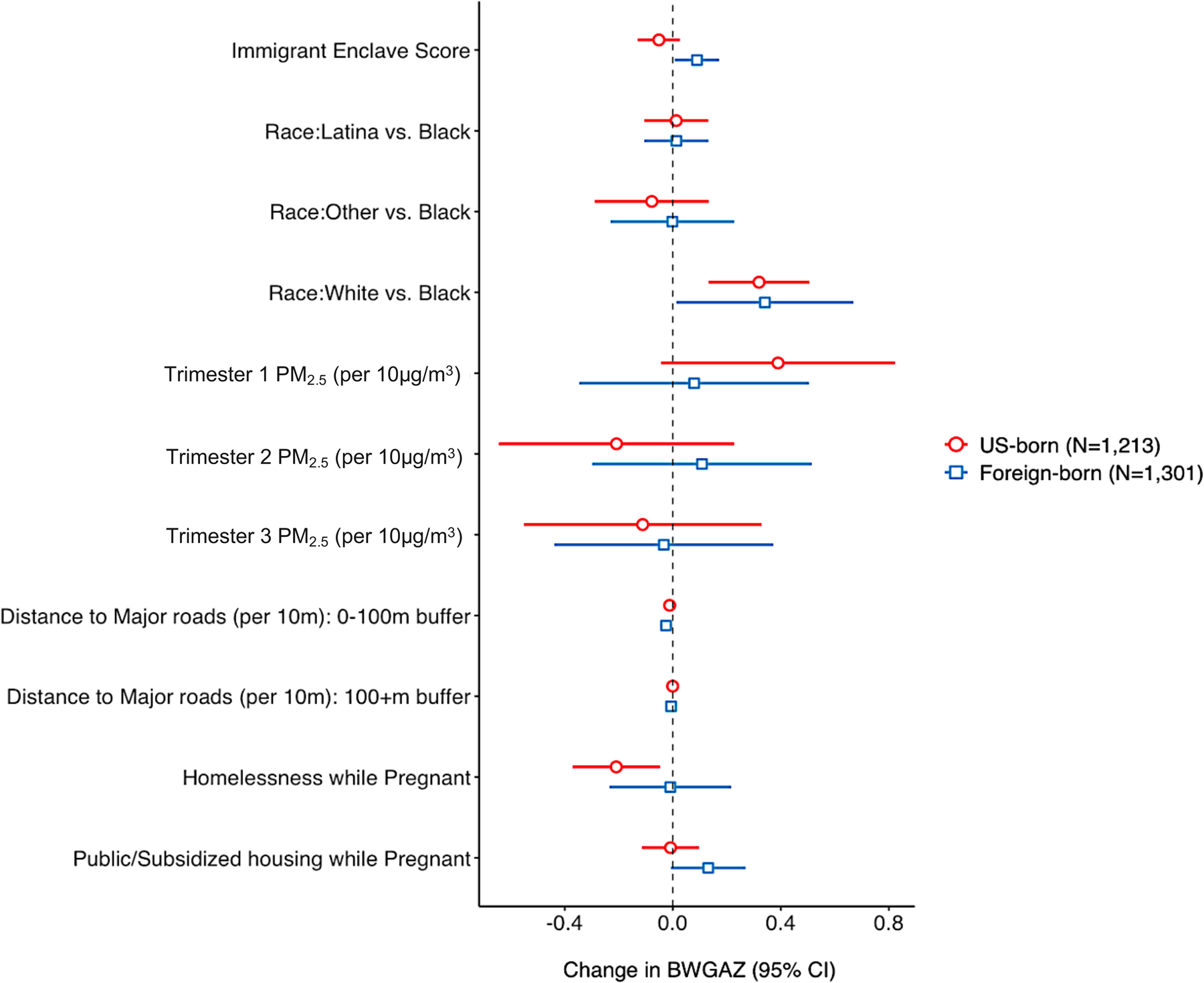

Across all models, the IBP was demonstrated: foreign-born mothers had children with 0.176 (95% CI: 0.092, 0.261) higher BWGAZ compared to US-born mothers on average (Table 2, Model 3). The interaction between immigrant enclave score and maternal nativity was significant (p=0.014), with an additional 0.134 (95% CI: 0.027, 0.241) increase in BWGAZ for foreign-born mothers per one-unit increase in their immigrant enclave score (Table 2, Model 4). In models stratified by nativity status, immigrant enclave was positively associated with BWGAZ among foreign-born mothers (0.090, 95% CI: 0.007, 0.172) but not among US-born mothers (−0.052, 95% CI: −0.130, 0.027) (Figure 3, Table S4). To contextualize our BWGAZ findings with other classifications of birthweight, an average 0.090 increase in BWGAZ corresponded to an average 52.97 (95% CI: 9.99, 95.95) gram increase or a 2.67 (95% CI: 0.32, 5.03) weight-for-gestational age percentile increase per one-unit increase in immigrant enclave score (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Adjusted mean differences in birthweight-for-gestational-age z-scores for US-born and foreign-born mothers, Boston-based Children’s HealthWatch cohort, 2006–2015 (N=2,514). Models adjusted for census-tract poverty level, maternal age at delivery, WIC participation during pregnancy, year and season of child’s birth.

We also observed persistent racial disparities. White mothers had children with 0.360 (95% CI: 0.203, 0.518) higher mean BWGAZ compared to Black mothers. Other risk factors for lower BWGAZ were younger age at delivery and homelessness during pregnancy (Table 2, Model 3).

Sensitivity analyses

Our model findings were generally insensitive to further sample restriction of dyads without a residential address reported in the EMR at the time of child’s birth, though we may have underestimated the effect of third trimester ambient PM2.5 concentrations (Table S5, Model B). Restricting the sample to mother-child dyads from the Boston metropolitan area (Table S5, Model C) and to infants with normal birthweights (2,500–4,000 grams) (Table S6) had minimal impact on model findings, though some estimates attenuated. In models stratified by child sex, the associations remained generally consistent with a few exceptions for the air pollution measures. Significant associations with road proximity and homelessness during pregnancy were observed only among female children, while significant associations with first trimester PM2.5 concentrations were observed only among male children (Table S7).

Discussion

Our study is one of the first to investigate the role of immigrant enclaves and ambient air pollution on birthweight outcomes in an urban cohort of non-smoking foreign-born and US-born women. We found evidence of the IBP in our cohort, in which foreign-born women had children with higher BWGAZ than US-born women despite having less college education and even after controlling for pregnancy and environmental risk factors. Residence in immigrant enclaves was significantly associated with higher BWGAZ for children of foreign-born women. Proximity to major roads was associated with lower BWGAZ for children of all women and correlated with higher immigrant enclave scores. Overall, our findings suggest the role of immigrant enclaves in the IBP and its potential spatial correlation with environmental risk factors.

Our study demonstrated that maternal nativity was a significant modifier of the association between residence in immigrant enclaves and BWGAZ. The salutary effect of immigrant enclaves for only foreign-born women is consistent with previous findings [10,11]. Immigrant enclaves may function as safe-havens from negative experiences like discrimination and spatial isolation for foreign-born residents [5]. They may promote favorable birth outcomes through increased access to social support, health information, financial resources, and ethnic-specific and linguistically-accessible services [5,13–15]. In addition, they may also reinforce familial, cultural, or community norms about health behaviors during pregnancy, such as healthier diets, less alcohol and tobacco use, and prenatal care services [12,17,18,21]. In our cohort, mothers living in immigrant enclave areas were more likely to be foreign-born, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and less assimilated (e.g. recently immigrated, limited English proficiency, lower educational attainment). As such, for these immigrant groups, immigrant enclaves may play a role in alleviating socioeconomic and assimilation stressors and their negative impacts on birthweight. However, other studies have found null [19–21] and negative effects [49] of immigrant enclaves on birthweight outcomes for foreign-born women, which may be due to differences in population composition, geography, and/or measures of immigrant enclaves across studies, and should be further explored.

A key finding in our study was the negative effect of proximity to major roads on birthweight outcomes, consistent with previous findings [27,29,31–33,47]. A study in Boston found that mothers living within 50 meters versus 200+ meters of major roads had a −0.26 (95% CI, −0.49, −0.04) lower BWGAZ [29]. Similarly, a study of full-term infants in Spain found that residence within 200 meter of major roads was associated with a 46% increase in the risk of low birthweight [31]. Road traffic and vehicular emissions are major sources of multiple air pollutants associated with adverse birth outcomes [31,47,55–57]. Exposure to these hazards can impair both maternal health and fetal growth through increased oxidative stress and DNA damage, cardiovascular inflammatory responses, allergic immune response, and arrythmia [29,55]. Impacts on maternal health can also impair transplacental function and nutrient transmission [58]. In our urban cohort of predominantly non-white and low-income women, over half lived within 100 meters of major roads during pregnancy and thus, may have had higher exposure to road traffic pollutants. Our findings underscore pervasive environmental justice concerns in low-income communities of color and the need for further regulations and interventions to reduce exposure disparities in traffic-related air pollution [24–26,59].

We found positive associations between immigrant enclave score and closer proximity to major roads and second trimester PM2.5 concentrations. This is consistent with previous studies documenting higher concentrations of air toxic clusters [24] and PM2.5 concentrations [22] in areas with a higher proportion of foreign-born residents. However, the adjustment of prenatal PM2.5 and proximity to major roads had minimal impact on the association of immigrant enclave score and BWGAZ, contrary to our expectation. Similarly, a recent study of ethnic enclaves among Asian/Pacific Islander women found that the association of ethnic enclave and gestational diabetes did not vary by levels of ambient volatile organic compounds [62]. We also found that prenatal PM2.5 concentrations across trimesters were poorly associated with BWGAZ. This may be due to spatial homogeneity of PM2.5 concentrations in our study population given the relatively small geographical coverage. Other studies of prenatal PM2.5 exposure have also found null associations with birthweight outcomes [29,48,57,60]. Relative to PM2.5, our study may have been better equipped to capture the effect of proximity to major roads, which was poorly correlated with PM2.5 in our cohort (|ρ| ≤ 0.020) but significantly associated with BWGAZ.

Our study also yielded findings that lead to further insights about our cohort and areas for future research. Notably, we found significant racial disparities in BWGAZ between Black and White mothers in our cohort, even after controlling for prenatal risk factors, neighborhood poverty, and environmental exposures. These findings suggest potential underlying impacts of structural racism on birthweight outcomes that we could not directly account for, such as institutional and everyday discrimination, redlining, residential segregation, and housing insecurity that are disproportionate among Black women and associated with adverse birth outcomes [71–76]. While these factors correlate with neighborhood poverty and environmental pollution, they should be independently accounted for in future studies of immigrant enclaves and birthweight.

In addition, US-born mothers in our cohort did not experience beneficial effects of residence in immigrant enclaves compared to foreign-born mothers. On the contrary, the association of immigrant enclave score and BWGAZ among US-born mothers was weakly negative, which could indicate their social isolation or blocked socioeconomic or spatial mobility to move away [14,63]. Previous studies have found increased racial/ethnic tensions [64], dissatisfaction with socioeconomic or neighborhood conditions, and greater competition for housing and neighborhood amenities [65] in areas of rapid immigrant growth. The role of immigrant enclaves on birthweight for US-born residents remains inconsistent in the literature [20, 66], and therefore, further research is needed to understand these findings.

Migration selection factors could contribute to the IBP observed in our cohort [5,67]. Prior studies of the ‘healthy migrant effect’ suggest that foreign-born women who are able to internationally migrate may be healthier than those who remain in their home country [67]. Even so, upon coming to the US, immigrants face discrimination, language, cultural, and legal barriers navigating the US health care systems that could counter their initial health advantage [68]. Most foreign-born women in our cohort did not attend college and a third of the women were limited-English speakers. Hence, it is likely that they had encountered these assimilation stressors. Another selection factor is return migration in which women with high-risk pregnancies or limited health care access may return to their home country prior to delivering [69]. While we could not test for this, we think this was unlikely in our cohort given potential travel risks during pregnancy [70]. However, migration selection factors should be considered in future studies.

Our study is subject to several limitations. Self-reported information from CHW surveys is susceptible to recall bias, though we expect any bias to be non-differential by residence in immigrant enclaves and nativity status. We also used smoking in the past five years as a surrogate for smoking during pregnancy, which could introduce residual confounding. However, this recall period should span the period of pregnancy since all mothers completed surveys within four years of child’s birth. Secondly, we could not account for other pregnancy risk factors such as alcohol/drug use, physical activity, pre-pregnancy weight, pregnancy weight gain, routine prenatal care, or medical complications due to limited information available. However, our main analysis was focused on BWGAZ by residence in immigrant enclaves, which is at the neighborhood-level and less likely influenced by these individual-level risk factors. Thirdly, we used maternal residential address at delivery or first reported in the EMR as surrogate for residence throughout pregnancy, which could introduce exposure misclassification. However, our analysis excluded mothers who reported moving during pregnancy or moving anytime without a known address at delivery. Our sensitivity analyses indicated that if anything, our analysis may have underestimated the effects of third trimester PM2.5. Any exposure misclassification should be minimal and non-differential. Fourthly, spatial imprecision in the estimation of PM2.5 and road proximity and the use of census-tract density measures to estimate immigrant enclave could also contribute to non-differential measurement error. Fifthly, more specific data on time-activity patterns and other sources of PM2.5 exposure during pregnancy (e.g. indoor, occupational) would enable better assessment of personal exposure, although this was beyond the scope of our study. Lastly, our population included only English- and Spanish-speakers and did not have a large representation of Asian and Pacific Islander women, which limits the generalizability of our findings to other populations. We could not disaggregate foreign-born populations by immigration characteristics (e.g. region of origin, length of time in US) due to limited sample size. Also, we could not fully differentiate between race and ethnicity due to limited race data among Latina women.

Our study has several strengths. It is one of the first to investigate the role of immigrant enclaves on birthweight outcomes accounting for ambient air pollution. Compared to previous studies, our population is restricted to non-smoking and predominantly low-SES women in order to minimize individual-level contributors of birthweight disparities and focus on immigrant enclave and environmental exposures. Our study population is comprised of Black and Latina immigrants, mostly from the Caribbean and Central and South Americas, while most IBP studies focus exclusively on Latina populations [6,10,20]. In addition, we used a composite measure of immigrant enclave at the census-tract level which may capture multiple dimensions and at finer spatial resolution compared to measures based on a single variable [20,76–78] and at the metropolitan level [12,79]. Our prenatal PM2.5 estimates were also generated at fine spatial resolution (1-km2), which minimized ecological bias that estimates at the county-level or based on distance to nearest monitor [28, 80] may be susceptible to. Our model for PM2.5 estimates also had excellent performance (mean out of sample R2 = 0.87) with minimal bias in the predicted concentration (slope of predictions vs. withheld observations = 0.99) [49]..

Overall, our study emphasizes the role of neighborhood social-contextual and environmental factors in shaping immigrant birthweight disparities. In an urban cohort of low SES and non-smoking women, we observed a protective association of residence in immigrant enclaves for foreign-born women and a negative association of proximity to major roads for all women. Our findings demonstrate the importance of accounting for immigrant enclaves, its interaction with nativity status, and its potential clustering with environmental exposures to disentangle the IBP. In addition, our study population is considered a vulnerable group: most children were on public insurance and had birthweights below the national average. Negative BWGAZs have been associated with higher odds of infant mortality, even among mildly growth-restricted infants [81]. Therefore, interventions that preserve immigrant enclaves and reduce exposure disparities in traffic-related air pollution could have large impacts on perinatal health. In addition, future studies should account for structural determinants of lower birthweight (e.g. racism, housing insecurity, residential segregation) that may explain persistent racial disparities in birthweight outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families and children who participated in the Boston-based Children’s HealthWatch survey, without whom these analyses would not have been possible. The authors also thank Itai Kloog, from the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, and Joel Schwartz, from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, for providing exposure data. Our work was part of the Center for Research on Environmental and Social Stressors in Housing Across the Life Course (CRESSH). CRESSH is a partnership between the Boston University School of Public Health and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health that studies environmental health disparities in low-income communities throughout MA.

Funding

This study was supported by the NIH/NIMHD grant (P50MD010428); NIH/NIEHS grants (T32ES007069, P30 ES000002, and R01 ES024332); and USEPA grants (RD83615601, RD83587201, and RD835872). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the grantee and does not represent official views of any funding entity. Further, no parties involved endorse the purchase of any commercial products or services discussed in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no actual or potential competing financial interests and that their freedom to design, conduct, interpret, and publish research is not compromised by any controlling sponsor.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

MyDzung T. Chu: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal analysis; Software; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing. Stephanie Ettinger de Cuba: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing - review & editing. M. Patricia Fabian: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing - review & editing. Kevin James Lane: Data curation; Methodology; Writing - review & editing. Tamarra James-Todd: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing - review & editing. David R. Williams: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing - review & editing. Brent A. Coull: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing - review & editing; Fei Carnes: Data curation. Marisa Massaro: Data curation. Jonathan I. Levy: Writing - review & editing; Funding acquisition. Francine Laden: Writing - review & editing; Funding acquisition. Megan Sandel: Writing - review & editing. Gary Adamkiewicz: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal analysis; Writing - review & editing; Supervision. Antonella Zanobetti: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Data curation; Methodology; Formal analysis; Writing - review & editing.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center [Internet]. Key findings about U.S. immigrants. 2021. [updated 2020 Aug 20; cited 2020 Jul 11]. Available from www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/.

- 2.Ferré C, Callaghan W, Olson C, Sharma A, Barfield W. Effects of maternal age and age-specific preterm birth rates on overall preterm birth rates—United States, 2007 and 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016. Nov 4;65(43):1181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Womack LS, Rossen LM, Martin JA. Singleton Low birthweight rates, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2006–2016. [PubMed]

- 4.Fuentes-Afflick E, Lurie P. Low birth weight and Latino ethnicity: examining the epidemiologic paradox. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1997. Jul 1;151(7):665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Committee on Population. The integration of immigrants into American society. National Academies Press; 2016. Apr 17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acevedo-Garcia D, Soobader MJ, Berkman LF. The differential effect of foreign-born status on low birth weight by race/ethnicity and education. Pediatrics. 2005. Jan 1;115(1):e20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acevedo-Garcia D, Bates LM. Latino health paradoxes: empirical evidence, explanations, future research, and implications. In Latinas/os in the United States: Changing the face of America 2008. (pp. 101–113). Springer, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flores ME, Simonsen SE, Manuck TA, Dyer JM, Turok DK. The “Latina epidemiologic paradox”: contrasting patterns of adverse birth outcomes in US-born and foreign-born Latinas. Women’s Health Issues. 2012. Sep 1;22(5):e501–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portes A, Manning RD. The immigrant enclave: Theory and empirical examples. Routledge; 2018. May 4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finch BK, Lim N, Perez W, Do DP. Toward a population health model of segmented assimilation: The case of low birth weight in Los Angeles. Sociological Perspectives. 2007. Sep;50(3):445–68. [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Sayed AM, Galea S. Community context, acculturation, and low-birth-weight risk among Arab Americans: evidence from the Arab–American birth-outcomes study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2010. Feb 1;64(2):155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams AD, Messer LC, Kanner J, Ha S, Grantz KL, Mendola P. Ethnic enclaves and pregnancy and behavior outcomes among Asian/Pacific Islanders in the USA. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2020. Apr;7(2):224–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Kelly MP, Schauffler R. Divided fates: Immigrant children in a restructured US economy. International Migration Review. 1994. Dec;28(4):662–89. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Not everyone is chosen: Segmented assimilation and its determinants. Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. 2001:44–69. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Portes A, Kyle D, Eaton WW. Mental illness and help-seeking behavior among Mariel Cuban and Haitian refugees in South Florida. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992. Dec 1:283–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGlade MS, Saha S, Dahlstrom ME. The Latina paradox: an opportunity for restructuring prenatal care delivery. American journal of public health. 2004. Dec;94(12):2062–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page RL. Positive pregnancy outcomes in Mexican immigrants: what can we learn?. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2004. Nov;33(6):783–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bethel JW, Schenker MB. Acculturation and smoking patterns among Hispanics: a review. American journal of preventive medicine. 2005. Aug 1;29(2):143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Britton ML, Shin H. Metropolitan residential segregation and very preterm birth among African American and Mexican-origin women. Social Science & Medicine. 2013. Dec 1;98:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osypuk TL, Bates LM, Acevedo-Garcia D. Another Mexican birthweight paradox? The role of residential enclaves and neighborhood poverty in the birthweight of Mexican-origin infants. Social science & medicine. 2010. Feb 1;70(4):550–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kane JB, Teitler JO, Reichman NE. Ethnic enclaves and birth outcomes of immigrants from India in a diverse US state. Social Science & Medicine. 2018. Jul 1;209:67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fong KC, Bell ML. Do fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5) exposure and its attributable premature mortality differ for immigrants compared to those born in the United States?. Environmental research. 2020. Oct 28:110387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brugge D, Leong A, Averbach AR, Cheung FM. An environmental health survey of residents in Boston Chinatown. Journal of immigrant health. 2000. Apr 1;2(2):97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liévanos RS. Race, deprivation, and immigrant isolation: The spatial demography of air-toxic clusters in the continental United States. Social Science Research. 2015. Nov 1;54:50–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grineski SE, Collins TW, Chakraborty J. Hispanic heterogeneity and environmental injustice: Intra-ethnic patterns of exposure to cancer risks from traffic-related air pollution in Miami. Population and environment. 2013. Sep 1;35(1):26–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter LM. The spatial association between US immigrant residential concentration and environmental hazards. International Migration Review. 2000. Jun;34(2):460–88. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritz B, Wilhelm M. Ambient air pollution and adverse birth outcomes: methodologic issues in an emerging field. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology. 2008. Feb;102(2):182–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell ML, Ebisu K, Belanger K. Ambient air pollution and low birth weight in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Environmental health perspectives. 2007. Jul;115(7):1118–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleisch AF, Rifas-Shiman SL, Koutrakis P, Schwartz JD, Kloog I, Melly S, et al. Prenatal exposure to traffic pollution: associations with reduced fetal growth and rapid infant weight gain. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.). 2015. Jan;26(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kloog I, Melly SJ, Ridgway WL, Coull BA, Schwartz J. Using new satellite based exposure methods to study the association between pregnancy PM 2.5 exposure, premature birth and birth weight in Massachusetts. Environmental Health. 2012. Dec;11(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dadvand P, Ostro B, Figueras F, Foraster M, Basagaña X, Valentín A, et al. Residential proximity to major roads and term low birth weight: the roles of air pollution, heat, noise, and road-adjacent trees. Epidemiology. 2014. Jul 1:518–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yorifuji T, Naruse H, Kashima S, Murakoshi T, Tsuda T, Doi H, et al. Residential proximity to major roads and placenta/birth weight ratio. Science of the total Environment. 2012. Jan 1;414:98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brauer M, Lencar C, Tamburic L, Koehoorn M, Demers P, Karr C. A cohort study of traffic-related air pollution impacts on birth outcomes. Environmental health perspectives. 2008. May;116(5):680–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez HA, Kubzansky LD, Campen MJ, Slavich GM. Early life stress, air pollution, inflammation, and disease: an integrative review and immunologic model of social-environmental adversity and lifespan health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018. Sep 1;92:226–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riva D, Magalhaes CB, Lopes A, Lancas T, Mauad T, Malm O, et al. Low dose of fine particulate matter (PM2. 5) can induce acute oxidative stress, inflammation and pulmonary impairment in healthy mice. Inhalation toxicology. 2011. Apr 1;23(5):257–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bosdriesz JR, Lichthart N, Witvliet MI, Busschers WB, Stronks K, Kunst AE. Smoking prevalence among migrants in the US compared to the US-born and the population in countries of origin. PloS one. 2013. Mar 8;8(3):e58654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ettinger de Cuba S, Chilton M, Bovell-Ammon A, Knowles M, Coleman SM, Black MM, et al. Loss of SNAP is associated with food insecurity and poor health in working families with young children. Health Affairs. 2019. May 1;38(5):765–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosofsky AS, Fabian MP, Ettinger de Cuba S, Sandel M, Coleman S, Levy JI, et al. Prenatal Ambient Particulate Matter Exposure and Longitudinal Weight Growth Trajectories in Early Childhood. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020. Jan;17(4):1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilcox AJ. On the importance—and the unimportance—of birthweight. International journal of epidemiology. 2001. Dec 1;30(6):1233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bollen KA, Bauldry S. Three Cs in measurement models: causal indicators, composite indicators, and covariates. Psychological methods. 2011. Sep;16(3):265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosseel Y Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). Journal of statistical software. 2012. Dec 19;48(2):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. SAS Program for the 2000 CDC Growth Charts (ages 0 to <20 years). 2019. [updated 2019 Feb 26; cited 2020 July 11]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm/

- 43.Grummer-Strawn LM, Reinold C, Krebs NF; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of the World Health Organization and CDC growth charts for children aged 0–59 months in the United States. Recommendations and Reports. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 2010; 59(RR-9);1–15. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5909a1.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. How Your Fetus Grows During Pregnancy. 2021. [updated 2020 Aug; cited 2020 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.acog.org/patient-resources/faqs/pregnancy/how-your-fetus-grows-during-pregnancy#measured

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Z-score Data files. 2009. [updated 2009 Aug 4; cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/zscore.htm.

- 46.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC pediatrics. 2003. Dec;3(1):1–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lakshmanan A, Chiu YH, Coull BA, Just AC, Maxwell SL, Schwartz J, Gryparis A, Kloog I, Wright RJ, Wright RO. Associations between prenatal traffic-related air pollution exposure and birth weight: Modification by sex and maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index. Environmental research. 2015. Feb 1;137:268–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosa MJ, Pajak A, Just AC, Sheffield PE, Kloog I, Schwartz J, et al. Prenatal exposure to PM2.5 and birth weight: A pooled analysis from three North American longitudinal pregnancy cohort studies. Environment international. 2017. Oct 1;107:173–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rhee J, Fabian MP, Ettinger de Cuba S, Coleman S, Sandel M, Lane KJ, et al. Effects of maternal homelessness, supplemental nutrition programs, and prenatal PM2.5 on birthweight. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019. Jan;16(21):4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MassGIS (Bureau of Geographic Information). MassGIS Data: Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) Roads. 2018. [cited 2020 Jul 11]. Available from: https://docs.digital.mass.gov/dataset/massgis-data-massachusetts-department-transportation-massdot-roads.

- 51.Shiono PH, Rauh VA, Park M, Lederman SA, Zuskar D. Ethnic differences in birthweight: the role of lifestyle and other factors. American Journal of Public Health. 1997. May;87(5):787–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson A, Chiu YH, Hsu HH, Wright RO, Wright RJ, Coull BA. Potential for bias when estimating critical windows for air pollution in children’s health. American journal of epidemiology. 2017. Dec 1;186(11):1281–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandel M, Sheward R, Ettinger de Cuba S, Coleman S, Heeren T, Black MM, et al. Timing and duration of pre-and postnatal homelessness and the health of young children. Pediatrics. 2018. Oct 1;142(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buuren SV, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of statistical software. 2010:1–68. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, Bell R, Pless-Mulloli T, Howel D. Particulate air pollution and fetal health: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiology. 2004. Jan 1:36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laurent O, Wu J, Li L, Chung J, Bartell S. Investigating the association between birth weight and complementary air pollution metrics: a cohort study. Environmental Health. 2013. Dec 1;12(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laurent O, Hu J, Li L, Kleeman MJ, Bartell SM, Cockburn M, et al. Low birth weight and air pollution in California: Which sources and components drive the risk? Environ Int. 2016; 92–93:471–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kannan S, Misra DP, Dvonch JT, Krishnakumar A. Exposures to airborne particulate matter and adverse perinatal outcomes: a biologically plausible mechanistic framework for exploring potential effect modification by nutrition. Environmental health perspectives. 2006. Nov;114(11):1636–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pratt GC, Vadali ML, Kvale DL, Ellickson KM. Traffic, air pollution, minority and socio-economic status: addressing inequities in exposure and risk. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2015. May;12(5):5355–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gehring U, Wijga AH, Fischer P, de Jongste JC, Kerkhof M, Koppelman GH, et al. Traffic-related air pollution, preterm birth and term birth weight in the PIAMA birth cohort study. Environmental research. 2011. Jan 1;111(1):125–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mannes T, Jalaludin B, Morgan G, Lincoln D, Sheppeard V, Corbett S. Impact of ambient air pollution on birth weight in Sydney, Australia. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2005. Aug 1;62(8):524–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams AD, Ha S, Shenassa E, Messer LC, Kanner J, Mendola P. Joint effects of ethnic enclave residence and ambient volatile organic compounds exposure on risk of gestational diabetes mellitus among Asian/Pacific Islander women in the United States. Environ Health. 2021. May 8;20(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hall M, Crowder K. Native out-migration and neighborhood immigration in new destinations. Demography. 2014. Dec 1;51(6):2179–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boustan LP. Was postwar suburbanization “white flight”? Evidence from the black migration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2010. Feb 1;125(1):417–43. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Crowder K, Hall M, Tolnay SE. Neighborhood immigration and native out-migration. American sociological review. 2011. Feb;76(1):25–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mezuk B, Cederin K, Li X, Rice K, Kendler KS, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Immigrant enclaves and risk of diabetes: a prospective study. BMC Public Health. 2014. Dec 1;14(1):1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the” salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. American journal of public health. 1999. Oct;89(10):1543–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social science & medicine. 2012. Dec 1;75(12):2099–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Palloni A, Arias E. Paradox lost: explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography. 2004. Aug;41(3):385–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID). “Pregnant Travelers”. 2020. [updated 2020 Dec 21; cited 2020 Oct 1]. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/pregnant-travelers

- 71.Matoba N, Suprenant S, Rankin K, Yu H, Collins JW. Mortgage discrimination and preterm birth among African American women: An exploratory study. Health & Place. 2019. Sep 1;59:102193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wallace D Discriminatory mass de-housing and low-weight births: Scales of geography, time, and level. Journal of Urban Health. 2011. Jun 1;88(3):454–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Giurgescu C, McFarlin BL, Lomax J, Craddock C, Albrecht A. Racial discrimination and the Black-White gap in adverse birth outcomes: a review. Journal of midwifery & women’s health. 2011. Jul;56(4):362–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Collins JW Jr, David RJ, Handler A, Wall S, Andes S. Very low birthweight in African American infants: the role of maternal exposure to interpersonal racial discrimination. American journal of public health. 2004. Dec;94(12):2132–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Earnshaw VA, Rosenthal L, Lewis JB, Stasko EC, Tobin JN, Lewis TT, et al. Maternal experiences with everyday discrimination and infant birth weight: A test of mediators and moderators among young, urban women of color. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013. Feb 1;45(1):13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mehra R, Keene DE, Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR, Warren JL. Racial and ethnic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: Differences by racial residential segregation. SSM-population health. 2019. Aug 1;8:100417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li K, Wen M, Henry KA. Ethnic density, immigrant enclaves, and Latino health risks: a propensity score matching approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2017. Sep 1;189:44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nobari TZ, Wang MC, Chaparro MP, Crespi CM, Koleilat M, Whaley SE. Immigrant enclaves and obesity in preschool-aged children in Los Angeles County. Social science & medicine. 2013. Sep 1;92:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Allen JP, Turner E. Ethnic residential concentrations in United States metropolitan areas. Geographical Review. 2005. Apr 1;95(2):267–85. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Parker JD, Heck K, Schoendorf KC, Saulnier L, Basu R, Woodruff TJ. Comparing exposure metrics in the relationship between PM2.5 and birth weight in California. National Center for Environmental Economics, US Environmental Protection Agency; 2003. Nov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steurer MA, Peyvandi S, Costello JM, Moon-Grady AJ, Habib RH, Hill KD, et al. Association between Z-score for birth weight and postoperative outcomes in neonates and infants with congenital heart disease. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2021. Jan 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.