Abstract

Background

Postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) have an impact on the recovery of adults after surgery. It is therefore important to establish whether preoperative respiratory rehabilitation can decrease the risk of PPCs and to identify adults who might benefit from respiratory rehabilitation.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to assess the effectiveness of preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) on PPCs in adults undergoing cardiac or major abdominal surgery. We looked at all‐cause mortality and adverse events.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2014, Issue 10), MEDLINE (1966 to October 2014), EMBASE (1980 to October 2014), CINAHL (1982 to October 2014), LILACS (1982 to October 2014), and ISI Web of Science (1985 to October 2014). We did not impose any language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials that compared preoperative IMT and usual preoperative care for adults undergoing cardiac or major abdominal surgery.

Data collection and analysis

Two or more review authors independently identified studies, assessed trial quality, and extracted data. We extracted the following information: study characteristics, participant characteristics, intervention details, and outcome measures. We contacted study authors for additional information in order to identify any unpublished data.

Main results

We included 12 trials with 695 participants; five trials included participants awaiting elective cardiac surgery and seven trials included participants awaiting elective major abdominal surgery. All trials contained at least one domain judged to be at high or unclear risk of bias. Of greatest concern was the risk of bias associated with inadequate blinding, as it was impossible to blind participants due to the nature of the study designs. We could pool postoperative atelectasis in seven trials (443 participants) and postoperative pneumonia in 11 trials (675 participants) in a meta‐analysis. Preoperative IMT was associated with a reduction of postoperative atelectasis and pneumonia, compared with usual care or non‐exercise intervention (respectively; risk ratio (RR) 0.53, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.34 to 0.82 and RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.77). We could pool all‐cause mortality within postoperative period in seven trials (431 participants) in a meta‐analysis. However, the effect of IMT on all‐cause postoperative mortality is uncertain (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.04 to 4.23). Eight trials reported the incidence of adverse events caused by IMT. All of these trials reported that there were no adverse events in both groups. We could pool the mean duration of hospital stay in six trials (424 participants) in a meta‐analysis. Preoperative IMT was associated with reduced length of hospital stay (MD ‐1.33, 95% CI ‐2.53 to ‐0.13). According to the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group guidelines for evaluating the impact of healthcare interventions, the overall quality of studies for the incidence of pneumonia was moderate, whereas the overall quality of studies for the incidence of atelectasis, all‐cause postoperative death, adverse events, and duration of hospital stay was low or very low.

Authors' conclusions

We found evidence that preoperative IMT was associated with a reduction of postoperative atelectasis, pneumonia, and duration of hospital stay in adults undergoing cardiac and major abdominal surgery. The potential for overestimation of treatment effect due to lack of adequate blinding, small‐study effects, and publication bias needs to be considered when interpreting the present findings.

Plain language summary

Breathing training before surgery for reducing lung complications after surgery in adults undergoing heart and major abdominal surgery

Background and review question

Despite advances regarding patient care in the last few decades, breathing complications as a result of lung injury after surgery such as pneumonia are the leading cause of sickness and death in adults undergoing heart and major abdominal surgery. Training of breathing muscles using a small device at home before surgery seems to make breathing easier and helps strengthen muscles of respiration after surgery. This training may help reduce breathing complications after surgery and may lead to improved patient care and overall health care cost savings for the public health system. We wanted to establish whether training of breathing muscles before surgery can reduce the risk of lung complications and to identify who in particular might benefit from such training.

Objective

We reviewed the evidence about the effects of breathing training before surgery on lung complications after surgery in adults undergoing heart or major abdominal surgery.

Study characteristics

We included 12 trials with 695 participants. Five of the 12 studies included participants awaiting planned heart surgery, and seven studies included participants awaiting planned major abdominal surgery. The evidence is current to October 2014.

Key results

This review showed that training of breathing muscles before surgery reduced the risk of some lung complications (atelectasis and pneumonia) after surgery and the length of hospital stay, compared with usual care. However, the effect of this training on in‐hospital death after surgery is unclear and needs further investigation. The trials did not report any undesirable effects associated with training of breathing muscles, and no study reported on costs resulting from breathing training using a device.

Quality of evidence and conclusion

Although the available evidence is insufficient in terms of the quality and size of trials, we can conclude that training of breathing muscles before surgery prevents lung complications after surgery. This training is easily performed at home under the supervision of a physiotherapist. The training of breathing muscles therefore appears to be a suitable option as one of the preparations for planned surgery, especially for adults awaiting high‐risk heart and abdominal surgery. Other surgeries, such as oesophageal resection (removal of part of the gastrointestinal tract 'food pipe'), should be evaluated; cost‐effectiveness and patient‐reported outcomes should be reported. The potential for overestimation of treatment effect needs to be considered when interpreting the present findings, as the quality of evidence is low to moderate.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Preoperative inspiratory muscle training compared to usual care, non‐exercise intervention for adults on waiting list for cardiac and major abdominal surgery.

| Preoperative inspiratory muscle training compared to usual care, non‐exercise intervention for adults on waiting list for cardiac and major abdominal surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: adult participants undergoing cardiac and major abdominal surgery Settings: hospital Intervention: preoperative inspiratory muscle training | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Preoperative inspiratory muscle training | |||||

| Postoperative atelectasis original authors’ definitions | Study population | RR 0.53 (0.34 to 0.82) | 443 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | I2 statistic = 0%, P value = 0.004 | |

| 207 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 (70 to 170) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 263 per 1000 | 139 per 1000 (89 to 216) | |||||

| Postoperative pneumonia original authors’ definitions | Study population | RR 0.45 (0.26 to 0.77) | 675 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2,3,4 | I2statistic = 0%, P value = 0.004 | |

| 117 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (31 to 90) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 83 per 1000 | 37 per 1000 (22 to 64) | |||||

| Mechanical ventilation > 48 hours | Study population | RR 0.55 (0.03 to 9.2) | 338 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,5,6 | I2 statistic = 56%, P value = 0.68, effect is uncertain | |

| 36 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (1 to 327) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| All‐cause mortality within 30 days during postoperative period | Study population | RR 0.4 (0.04 to 4.23) | 431 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,5,6,7 | I2 statistic = 59%, P value = 0.09, effect is uncertain | |

| 41 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (2 to 175) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 462 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | 8 studies reported on adverse events, however all these studies reported that there were no adverse events in both groups |

| Duration of hospital stay | ‐ | The mean duration of hospital stay in the intervention groups was 1.33 lower (2.53 to 0.13 lower) | ‐ | 424 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | I2 statistic = 7%, P value = 0.03 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 About half of studies were at unclear risk of bias in sequence generation and allocation concealment. (Downgraded one level for risk of bias.) 2 Different definition of postoperative pulmonary complications was used in each trial. (Downgraded one level for risk of bias.) 3 Small‐study effects may be present. (Downgraded one level for publication bias.) 4 RR < 0.5 (+1 for large effect) 5 I2 statistic ≥ 50% and P value < 0.1. (Downgraded one level for inconsistency.) 6 Confidence interval is wide and includes important benefit and potential harm. (Downgraded one level for imprecision.) 7 Even though six studies reported this outcome, three studies had zero events, and therefore only three studies could be pooled in the analysis (Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006b; Soares 2013).

Background

Description of the condition

Despite advances in perioperative care in the last few decades, postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) are probably the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in adults undergoing chest and abdominal surgery. PPCs and cardiac complications are commonly regarded as the two major causes of perioperative problems in selected groups of patients undergoing these high‐risk surgical procedures (Mendez‐Tellez 2008). However, PPCs are more common than postoperative cardiac complications and play a bigger role in mortality and healthcare costs (Fleischmann 2003; Shander 2011; Smetana 2009). Despite these factors, the natural history of PPCs and the necessity of preventive strategies have not been well recognized in studies to date.

PPCs are comprised of atelectasis, pneumonia, bronchospasm, pleural effusion, pulmonary oedema, and respiratory failure (Brooks‐Brunn 1995). Differences in the definition of PPCs across studies have contributed to a wide range in the reported incidences (6% to 76%) (Chumillas 1998). Various changes in the respiratory system occur during the postoperative period that increase the risk of these complications, including consequences from the residual anaesthetic effect, the surgical procedure itself, and the effects of any premorbid conditions (Mendez‐Tellez 2008).

A number of recognized risk factors predispose the person to developing PPCs. These risk factors can be classified into procedure‐related and patient‐related risk factors (Mendez‐Tellez 2008; Qaseem 2006). Procedure‐related risk factors include the type of surgery (abdominal, thoracic, neuro, head and neck, vascular, aortic aneurysm repair, and emergency surgery are all associated with higher risk of PPCs), the site of incision, prolonged operative time (exceeding three hours), and the type of anaesthesia (Guimarães 2009; Qaseem 2006; Smetana 2009). Patient‐related risk factors include advanced age (equal to or greater than 60 years), pre‐existing disease (for example chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure), current smoking, alcohol consumption, functional dependence, impaired sensorium, recent marked weight loss, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status (PS) Classification System class 2 (mild systemic disease without functional limitations) or severer status (Mendez‐Tellez 2008; Qaseem 2006). It is important to consider these risk factors at the time of the preoperative evaluation.

Description of the intervention

Prevention of PPCs can be more effective than treatment of already established PPCs, and it is incumbent on the surgeon to ensure that all necessary measures have been taken to prevent PPCs in their patient. For example, patients at high risk of PPCs who are scheduled to undergo elective surgery should be considered for preoperative respiratory rehabilitation strategies. These strategies can be performed in the outpatient setting (for example at home or in a local rehabilitation clinic) under the supervision of a physiotherapist. Hospitalized patients should also be commenced on a respiratory rehabilitation strategy immediately before surgery.

Respiratory rehabilitation is now considered to be the standard of care for surgical patients, the techniques of which include deep‐breathing exercises, thoracic physiotherapy, incentive spirometry (IS), and preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT; see Types of interventions). To date, four systematic reviews have focused on IS for the prevention of PPCs after abdominal surgery (do Nascimento 2014; Lawrence 2006; Overend 2001; Thomas 1994). The most recent review, which compared the effect of IS with no therapy or physiotherapy on PPCs, concluded that there is no evidence to support the effectiveness of IS for the prevention of PPCs after upper abdominal surgery (do Nascimento 2014). As more meticulous perioperative management is required in high‐risk patients, preoperative IMT has recently received wide research attention as a means to preventing PPCs (Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010).

How the intervention might work

Respiratory muscle strength has not been reported to correlate with the routinely examined pulmonary function (for example vital capacity (VC), forced expired volume in one second (FEV1)) (Nomori 1994). However, people with respiratory muscle weakness have a higher risk of PPCs (Nomori 1994). This is thought to be due to inspiratory muscle fatigue leading to collapse of alveoli (Kulkarni 2010). Several authors have reported that preoperative IMT resulted in significant improvement in mean inspiratory muscle strength and endurance after thoracic and abdominal surgery without causing adverse effects (Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Nomori 1994). Thus, it is reasonable to assume that an increase in inspiratory muscle strength and endurance through preoperative IMT can lead to better‐quality deep breathing after surgery, which would in turn result in a decreased incidence of PPCs (Valkenet 2011).

In summary, preoperative IMT is a feasible intervention and seems to have a prophylactic effect against PPCs (Hulzebos 2006b; Valkenet 2011). This strategy to reduce PPCs can lead to improved perioperative patient care, better resource utilization, and overall cost savings (for example save extra invasive stresses and drugs, shorten the length of hospital stay and mechanical ventilation) for the public health system (Shander 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

PPCs affect the quality, effectiveness, and efficiency of postoperative patient care. It is therefore important to establish whether preoperative respiratory rehabilitation can decrease the risk of PPCs and to identify patients who might benefit from respiratory rehabilitation.

Some published trials have demonstrated the advantages of preoperative IMT in participants undergoing cardiac surgery, in Hulzebos 2006a, Hulzebos 2006b, and Weiner 1998, or major abdominal surgery, in Dronkers 2008 and Kulkarni 2010. One systematic review summarized current evidence regarding the effectiveness of preoperative exercise therapy, including physical rehabilitation, on the postoperative complication rate in general (Valkenet 2011). However, to our knowledge no systematic review has focused on preoperative IMT alone for the prevention of PPCs. This systematic review will thus investigate whether preoperative IMT in participants undergoing cardiac or major abdominal surgery is an effective intervention for the prevention of PPCs. We hope that this review will help guide perioperative management in the future.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to assess the effectiveness of preoperative IMT on PPCs in adults undergoing cardiac or major abdominal surgery. We looked at all‐cause mortality and adverse events.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared preoperative IMT and usual preoperative care for adults undergoing cardiac or major abdominal surgery. We excluded quasi‐randomized studies, historically controlled trials, cohort studies, and case series. However, we planned to include cluster‐randomized trials if the intracluster correlation coefficient was reported.

Types of participants

We included adults (equal to or greater than 18 years of age) awaiting elective cardiac or major abdominal surgery.

We defined cardiac surgery as any surgical procedure involving the heart (for example coronary artery bypass graft surgery, valve surgery, and correction of congenital defects).

We defined major abdominal surgery as deliberate breach of peritoneum or retroperitoneum, including abdominal aortic surgery, gastrointestinal surgery, and urological surgery.

We excluded participants undergoing chest surgery that may involve the lung per se other than cardiac surgery because such procedures are likely to have a deep influence on pulmonary complications. We also excluded participants if they had undergone surgery within two weeks of initial contact. We excluded participants if they were ASA PS 5, or had a suspected or established respiratory infection.

Types of interventions

The intervention included a tailored training programme (called 'inspiratory muscle training', or IMT) designed to increase the strength and endurance of the inspiratory muscles. IMT consists of two distinct types of specific respiratory muscle training (that is respiratory muscle strength (resistive/threshold) and endurance (hyperpnoea) training). Training occurred five to seven times a week for at least two weeks before the actual date of surgery. Each session consisted of 15 to 30 minutes of IMT, performed under supervision by either a physiotherapist, physician, or researcher. The participants were trained to use an inspiratory threshold‐loading device with a load of 10% to 60% of maximal inspiratory muscle strength (Pi‐max). The participants in the intervention group also received usual care as defined below. We excluded participants who also received IMT after the surgery.

Our comparative intervention was usual care, a non‐exercise intervention, or no intervention. The usual‐care group received care as usual the day before surgery (instruction on deep‐breathing manoeuvres, IS, coughing, and early mobilization may be provided).

We included trials that required participants to undergo rehabilitation, as long as both groups (control and intervention) received similar IS, chest physiotherapy, and mobilization after surgery.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

PPCs. We defined clinically significant PPCs as two or more items in the grade 2 complications or one item in the grade 3 or 4 complications (Appendix 1).

All‐cause mortality within 30 days during postoperative period.

Evidence of adverse events from IMT.

Secondary outcomes

Maximal inspiratory muscle strength (Pi‐max) and endurance (Pm‐peak/Pi‐max). (Pm‐peak: Maximal negative pressure produced by the participant handling incremental resistance during the endurance test; inspiratory muscle strength and endurance assessed with respiratory pressure meter).

Duration of hospital stay.

Other types of complications within 30 days during postoperative period: cardiac complications, neurological complications, and surgical‐site infections (see Appendix 2 for detailed descriptions of each complication).

Total drop‐out from the study for any reason, as surrogate measure of overall acceptability.

Quality of life: patient‐reported health‐related quality of life such as the 12‐Item Short Form Health Survey, 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales, and World Health Organization Quality of Life.

Cost analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Anaesthesia, Critical and Emergency CareGroup's Trials Register (October 2014). We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2014 Issue 10, Appendix 3), MEDLINE (Ovid SP, 1966 to October 2014, Appendix 4), EMBASE (Ovid SP, 1980 to October 2014, Appendix 5), CINAHL (EBSCO host, 1982 to October 2014, Appendix 6), LILACS (via BIREME, 1982 to October 2014, Appendix 7), and ISI Web of Science (1985 to October 2014, Appendix 8).

We employed a sensitive search strategy and search using both subject headings and free‐text words. We used search strategies that are optimal for identifying RCTs, together with specific subject terms. We developed a search strategy for use in MEDLINE and revised it appropriately for use in all other databases in conjunction with the Cochrane Anaesthesia, Critical and Emergency Care Group. We used the cited and citing reference searching method in the Web of Science to find more recent articles that update earlier research. We imposed no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of the included articles. We also manually searched the journals Clinical Rehabilitation,Physiotherapy, and Physical Therapy from 1987 to October 2014. We attempted to contact relevant trial authors or experts in the field to identify any additional ongoing trials or unpublished data. We searched the conference proceedings of important meetings and abstracts. We also searched the databases of ongoing trials such as www.controlled‐trials.com/ and www.clinicaltrials.gov/. We contacted companies who supply respiratory muscle training devices in order to identify possible ongoing trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MK, AK) screened the titles and abstracts of all the publications obtained by the search strategy and independently selected trials that met our inclusion criteria.

We obtained the full text of all identified articles and any deemed unclear for inclusion from the titles and abstracts. We (MK, AK) independently examined the full‐text articles for inclusion. In case of disagreements, we consulted with a third independent review author (TT).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MK, AK) independently, and in duplicate, extracted data, including the following information.

Quality assessment of the study (risk of bias).

Participants' characteristics.

Intervention details and control agents.

Outcomes (types of outcome measures, timing of outcomes, effect differences).

We resolved any disagreements in consultation with a third review author (TT). We collected data manually on paper extraction forms and entered it into intermediate software (Microsoft Excel for Windows), ensuring accurate transfer by using double entry, before entering it into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5.3). This allowed for any necessary statistical conversions.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Two review authors (MK, AK) independently assessed trial quality. A third review author (TT) arbitrated and resolved any disagreements. We assessed risk of bias of all included studies across the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. For each included study, we assigned each of these domains one of three ratings: low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias (unclear indicating either lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias). We constructed a 'Risk of bias' graph and 'Risk of bias' summary figure using Review Manager (RevMan 5.3).

Measures of treatment effect

We performed all comparisons between the preoperative IMT and usual preoperative care groups. We used the following measures of the effect of intervention: we calculated the risk ratio for dichotomous outcomes and the mean difference (when all the outcomes are measured in the same unit) or standardized mean difference (when different scales are used for measuring the same construct) for continuous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

We took into account the level at which randomization occurred. We made an assessment of the randomization into simple parallel groups and the variations of this such as cluster‐randomized trials. Two review authors (MK, AK) reviewed the unit of analysis issues according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any differences by discussion. For trials that had a cross‐over design, we considered the results only from the first randomization periods. We included cluster‐randomized trials if the intracluster correlation coefficient was reported.

Dealing with missing data

We took the following steps for handling any missing data:

we calculated the standard deviation (SD) from study statistics (e.g. 95% confidence intervals (CIs), standard errors, t values, P values, F values) for missing SDs of continuous outcome data;

where possible, we contacted the original investigators of the study to obtain the missing data;

we addressed the potential impact of missing data on the findings of the review in the Discussion section;

when we could not calculate the exact SD, we imputed them from other studies in the meta‐analysis (Furukawa 2006).

We a priori planned to impute the missing SDs from other studies, but some studies reported quite different SDs of Pi‐max. We therefore did not pool the study in the meta‐analysis if we could not calculate the exact SD.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, that is we attempted to include all participants randomized to each group in the analyses, and analyse all participants in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. We calculated and reported the percentage lost to follow‐up if there was a discrepancy between the numbers randomized and analysed in each treatment group. If there were dropouts, we looked for reasons for the dropouts in the publication itself or obtained additional information from the authors of the publications as to the cause of the drop‐outs. We then carried out analyses with knowledge of the precise outcomes because it was possible to make an informed guess about dropouts. Finally, we repeated the meta‐analysis imputing the missing data and the dropouts as best‐ and worst‐possible outcomes in a sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used clinical heterogeneity to describe differences in participants, interventions, and outcomes that might reasonably affect recruitment strategies. We initially assessed heterogeneity by visual inspection of the results in the forest plots from a meta‐analysis of the studies. We measured statistical heterogeneity using the I2 and Cochran’s Q statistics (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003). If we identified significant heterogeneity (I2 statistic ≥ 50% and P value < 0.1), we investigated potential sources of the heterogeneity through subgroup and sensitivity analysis. We also undertook quality‐control checks of data extraction and input and reviewed the clinical and methodological aspects of the study trials.

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plot asymmetry may be caused by: selection bias (publication or location bias), poor methodological quality of smaller studies (design, analysis, fraud), true heterogeneity (variation with effect size), or artefact or chance (Egger 1997). In order to determine the level of publication bias, we performed a funnel plot analysis to visually assess whether small‐study effects may be present in the meta‐analysis, since sufficient numbers of trials allowed for a meaningful analysis.

Data synthesis

As the trials were sufficiently homogeneous, and clinically similar trials were available, we were able to pool the results in the meta‐analysis. We pooled data using the random‐effects model for dichotomous and continuous data because the intervention in question represents a complex, variable method and is expected to be associated with some clinical heterogeneity and also because the random‐effects model is known to be more conservative (i.e. is less likely to lead to type I error) than the fixed‐effect model.

Dichotomous data

We calculated the risk ratio as an effect measure and its associated 95% confidence interval (CI) because it was clinically interpretable and generalizable (Furukawa 2002). Where possible, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome and its 95% CI, assuming the observed average control event rate.

Continuous data

We calculated the mean difference and its associated 95% CI. We used the standardized mean difference for data that we could not convert to a uniform scale.

If no meta‐analysis was possible or appropriate due to substantive clinical or statistical (or both) heterogeneity, skewed distribution, missing data, or otherwise, we qualitatively summarized and described the identified trials.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where possible, we performed the following subgroup analyses. We were unable to perform some subgroup analyses due to lack of data.

Type of surgery: cardiac surgery or major abdominal surgery as subgroup analysis because the differences in operative procedure (procedure‐related risk factors) may affect the postoperative status of the participants.

High‐risk participants as subgroup analysis because patient‐related risk factors may affect the postoperative status of the participants. We included high‐risk participants if the trial reported the results of high‐risk participants separately. If the trial did not report these results separately, we attempted to contact relevant trial authors in order to identify any additional unpublished data about the participants' risk factors. We also included the trials in which more than 80% of participants had at least one risk factor. However, we anticipated that various studies would have used variable definitions of 'high‐risk participants'. We accepted the study authors' definitions.

Type of intervention as subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

To check the robustness of the observed findings, we performed the following sensitivity analyses using Stata, Stata 11, and Review Manager, RevMan 5.3.

Repeating meta‐analysis after exclusion of studies with high or unclear risk of bias in allocation concealment.

Repeating meta‐analysis after exclusion of studies in which the primary outcome evaluation was not blinded.

Repeating meta‐analysis imputing missing data and dropouts as best‐ and worst‐possible outcomes.

Comparing the difference of pooling analysis results by using a fixed‐effect and a random‐effects model.

Repeating meta‐analysis after exclusion of studies that used original authors' definition of PPCs and included no outcome based on our definition.

Summary of findings

We used the principles of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with the following specific outcomes in our review and constructed a Table 1 (Guyatt 2008):

PPCs;

all‐cause mortality within 30 days' postoperative period;

evidence of adverse events from IMT;

duration of hospital stay.

The GRADE approach assesses the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which there can be confidence that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. This assessment considers the study methodological quality, directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of the effect estimates, and the risk of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

We identified a total of 3218 citations from the database searches (see Figure 1 for selection process). Based on title and abstracts, we obtained copies of 61 full‐text studies that were potentially eligible for inclusion. After reading the full‐text papers, we excluded 46 studies from this review. We have provided the reasons for exclusion in Characteristics of excluded studies. We judged 12 trials (15 articles) eligible for inclusion (see Characteristics of included studies). We also identified two ongoing trials (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). We contacted the corresponding authors of the two ongoing studies and, at the time this review was submitted for editorial approval, we are still awaiting a reply.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 12 trials in this systematic review (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013; Weiner 1998). Three of the 12 trials were reported as a conference result only, including an abstract and poster presentation (Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Heynen 2012). We attempted to contact the authors of all 12 included trials for missing information; authors of nine trials responded, all of whom provided at least some of the desired information (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010).

Design

We included RCTs and cluster‐RCTs. All trials were single‐institution RCTs.

Sample size

In the majority of the trials, the sample sizes per arm were small. Seven of the 12 trials recruited fewer than 20 participants per arm (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Dronkers 2008; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Soares 2013). Three trials recruited 20 to 40 participants per arm (Dronkers 2010; Kulkarni 2010; Weiner 1998), and one trial recruited less than 10 participants per arm (Da Cunha 2013). Only one trial recruited over 100 participants to each arm (Hulzebos 2006b).

Setting

In six of the 12 included trials the setting was unclear (Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Heynen 2012; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013; Weiner 1998). Of the remaining six trials, three were conducted in university hospital settings (Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b), and three in non‐university hospital settings (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010). Of the 12 trials, five were performed in the Netherlands (Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b); five in Brazil (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Ferreira 2009; Soares 2013); one in the United Kingdom (Kulkarni 2010); and one in Israel (Weiner 1998).

Participants

Proportion of women

Three trials did not report the number of female participants (Da Cunha 2013; Heynen 2012; Weiner 1998). One trial recruited only women (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011). In the remaining eight trials, the proportion of females ranged between 22% and 78%.

Age

Ten of the 12 included trials provided the mean (or median) age of participants. The remaining two trials did not provide this information (Da Cunha 2013; Heynen 2012).

One trial recruited young participants, whose mean age was 35 (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011). Seven trials recruited middle‐age participants, whose mean age was in the 50s to 60s (Carvalho 2011; Dronkers 2008; Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013; Weiner 1998). The remaining two trials recruited elderly individuals only, whose mean age was in the 70s (Dronkers 2010; Hulzebos 2006a).

Participants' risk factors for PPCs

Nine of the 12 included trials reported the proportion of participants' risk factors for PPCs, such as smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, hypertension, and body mass index. Three of the 12 trials did not report participants' risk factors for PPCs (Da Cunha 2013; Heynen 2012; Weiner 1998).

Three trials included only participants with "high risk" factors for PPCs (the definition of "high risk" depended on the trial) (Dronkers 2008; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b). Five trials included participants at both high and low risk for PPCs. One trial included "high risk" participants, but the authors did not define "high risk" (Carvalho 2011).

Type of surgery

Five trials included participants awaiting elective cardiac surgery (Carvalho 2011; Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Weiner 1998); the remaining seven trials included participants awaiting elective major abdominal surgery (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Heynen 2012; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013).

Of the five cardiac surgery trials, four were only coronary artery bypass graft surgery (Carvalho 2011; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Weiner 1998), and one was both myocardial revascularization and valvuloplasty (Ferreira 2009).

The seven major abdominal surgery trials were: open Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass surgery (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011), aneurysm of the abdominal aorta (Dronkers 2008), colon surgery (Dronkers 2010), oesophagogastric surgery (Da Cunha 2013; Heynen 2012), and major abdominal or urological surgery (Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013).

Intervention

In 10 trials, the intervention was a simple preoperative IMT with threshold device (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Weiner 1998) (see Characteristics of included studies). In two trials, the intervention was a mixed training programme (Dronkers 2010; Soares 2013). The mixed training programme consisted of IMT with threshold‐loading device and exercise training of trunk and extremity. Kulkarni 2010 was a four‐arm RCT. The three different interventions were deep‐breathing exercises, incentive spirometry, and specific IMT with threshold‐loading device.

Comparisons

In eight trials (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Soares 2013), the control interventions were usual care or a non‐exercise intervention. In one trial, the control group underwent sham training, which consisted of breathing training through the same trainer but with no resistance (Weiner 1998). In another trial, the control group underwent home‐based exercise advice, which consisted of emphasizing the importance of the participant's physical condition to the postoperative course and encouragement to be active for minimally 30 minutes a day in the period prior to hospital admission (Dronkers 2010). In one trial, details of the control group were not described (Carvalho 2011). One trial was a four‐arm RCT in which participants were allocated to one of four groups (Group A, no training; Group B, deep‐breathing exercises; Group C, incentive spirometry; and Group D, specific IMT) (Kulkarni 2010). As described in the Methods section of our protocol (Katsura 2013), Group A, B, and C were the interventions of comparative group as usual care in our protocol.

Outcomes

All 12 included trials reported data on PPCs. Definitions for PPCs were author‐defined and varied across the trials. Of the 12 included trials, six did not report detailed definitions for PPCs (Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Ferreira 2009; Kulkarni 2010; Heynen 2012; Weiner 1998). Seven trials reported on all‐cause mortality (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006b; Soares 2013). Eight trials reported on adverse events (Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010).

As for secondary outcomes, all trials reported on maximal inspiratory muscle strength (Pi‐max), whereas only four trials reported respiratory muscle endurance (Pm‐peak/Pi‐max) (Dronkers 2008; Hulzebos 2006b; Soares 2013; Weiner 1998). Seven trials reported on the duration of hospital stay (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2010; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010). Two trials reported other types of early postoperative complications, that is cardiac or neurological or surgical site infection (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Ferreira 2009). Ten trials reported on total drop‐out from the study. One trial reported on quality of life (Dronkers 2010). No trial reported on cost analysis.

Excluded studies

Of the 61 trials retrieved for more detailed evaluation (full‐paper review), 46 trials did not meet our inclusion criteria and were excluded because of one of the following reasons: non‐randomized design including review articles (12 trials), interventions not relevant (33 trials), and other types of outcomes (one trial) (for full details see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Ongoing studies

We identified two ongoing studies from searching the database www.clinicaltrials.gov/ (NCT01321983; NCT01828632). (See Characteristics of ongoing studies.)

Studies awaiting classification

There are no studies awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

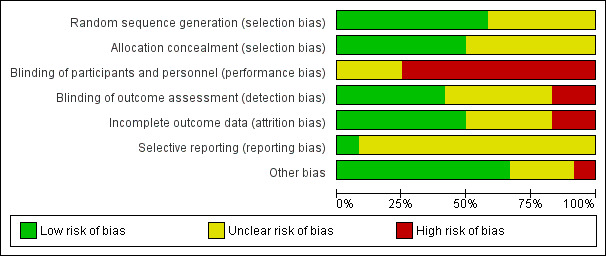

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for data on study quality.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

See Characteristics of included studies.

Allocation

Seven trials used an adequate method of generating random sequences (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). Three trials provided no description on random sequence generation (Carvalho 2011; Ferreira 2009; Weiner 1998). We contacted three authors for details regarding allocation concealment (Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006a; Weiner 1998), and one replied with the requested information (Hulzebos 2006a). Seven trials used an adequate method of allocation concealment (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). Five trials used sealed envelopes (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). One study used a computer‐generated allocation table (Hulzebos 2006a). Five trials provided no description.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the study designs, it was impossible to blind the participants in all trials. Of the 12 included trials, five trials adequately blinded the outcome assessors (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b). In two of the five trials, the radiologist who evaluated the images of pulmonary status was unaware of the allocation or participant information (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008). In the third trial, an investigator who was unaware of the treatment allocation assessed preoperative and postoperative measures (Dronkers 2010). In the fourth trial, a physical therapist who was blinded from the participant allocation took the outcome measures (Hulzebos 2006a). In the fifth trial, the incidence of PPCs was scored by a blinded independent investigator, and other data were evaluated by a blinded microbiologist (Hulzebos 2006b).

In two of the 12 included trials, the researchers and outcome assessors were identical (Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). The other five trials provided no information (Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Weiner 1998).

Incomplete outcome data

Nine trials adequately reported the information regarding the loss to follow‐up. In five trials, all participants completed the study (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006a). In three trials, the proportion of loss to follow‐up was small and similar between the groups (Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2010; Hulzebos 2006b).

One trial that compared four groups provided information on missing outcome data, but the proportion of loss to follow‐up was higher than 20% in two of the groups (Kulkarni 2010).

The remaining three studies provided no description.

Selective reporting

Only one trial adequately prespecified and reported the primary outcome (Hulzebos 2006b). The other trials either did not prespecify the primary outcome, or the protocols were unavailable.

Other potential sources of bias

Three trials did not reveal the participants' baseline data (Da Cunha 2013; Heynen 2012; Weiner 1998). The other nine trials revealed the participants' baseline data, and no baseline imbalance was found. One trial had a potential bias in its design: the intervention group was instructed to keep a diary, whereas the control group did not receive the same instruction (Dronkers 2008). This might have made the intervention group subject to the Hawthorne effect (Parsons 1974).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Overall, 12 trials involving 695 participants were available for assessing the effects of interventions. In one of the 12 trials (Kulkarni 2010), participants were allocated to one of four groups (Group A, control; Group B, deep‐breathing exercises; Group C, incentive spirometry; Group D, specific IMT). Following our protocol (Katsura 2013), we combined Groups A, B, and C into a single control group, which was compared with Group D, as an intervention group. Therefore, the results of the present systematic review included 320 participants allocated to the intervention group and 359 participants allocated to the control group. (See Table 1.) We pooled data using the random‐effects model because the intervention in question represents a complex, variable method and statistical significance were more conservative (i.e. is less likely to lead to type I error) than the fixed‐effect model.

Primary outcomes

1. PPCs

Different original authors' definitions for PPCs were used in all trials. The definition of Kroenke 1992, which we described in our protocol (Katsura 2013), was used in only one trial (Hulzebos 2006b). We therefore pooled data for the major three types of PPCs (atelectasis, pneumonia, and mechanical ventilation exceeding 48 hours) according to the original authors' definitions in a meta‐analysis, respectively.

1.1. PPCs; atelectasis

Seven trials involving 443 participants reported on postoperative atelectasis (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Dronkers 2008; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Soares 2013). Pooled analysis showed preoperative IMT was associated with a reduction of postoperative atelectasis, compared with usual care or non‐exercise intervention (risk ratio (RR) 0.53; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.34 to 0.82; P value = 0.004; I2 statistic = 0%) (Figure 4). Although we noted no heterogeneity between the trials, small‐study effects may be present. We therefore downgraded the outcome for risk of bias and publication bias and rated the quality of evidence as low quality.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, outcome: 1.1 PPC; Atelectasis.

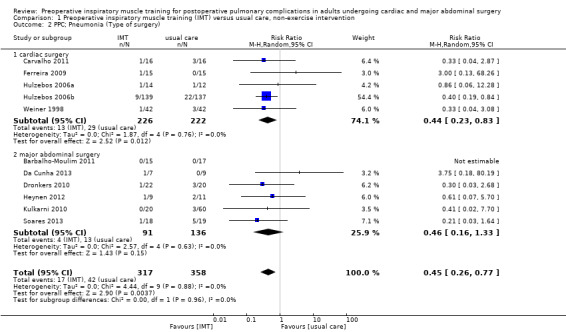

1.2. PPCs; pneumonia

Eleven trials involving 675 participants reported on postoperative pneumonia (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2010; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013; Weiner 1998). Pooled analysis showed preoperative IMT was associated with a reduction of postoperative pneumonia, compared with usual care or non‐exercise intervention (RR 0.45; 95% CI 0.26 to 0.77; P value = 0.004; I2 statistic = 0%) (Figure 5; Figure 6). Although we noted no heterogeneity between the trials, small‐study effects may be present. We downgraded the outcome for risk of bias and publication bias, but upgraded it for large effect (RR < 0.5). As a result, we rated the quality of evidence as moderate quality.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, outcome: 1.2 PPC; Pneumonia (Type of surgery).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, outcome: 1.3 PPC; Pneumonia (Type of intervention).

1.3. PPCs; mechanical ventilation exceeding 48 hours

Four trials reported on postoperative length of mechanical ventilation (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006b; Weiner 1998). One trial reported on postoperative ventilation dependence exceeding 24 hours (Weiner 1998). PPCs grade 4 is defined as the ventilator failure, which is postoperative ventilator dependence exceeding 48 hours (Appendix 1), according to Kroenke 1992's definition. We therefore pooled data for postoperative mechanical ventilation exceeding 48 hours from the remaining three trials in a meta‐analysis (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006b). Pooled analysis showed there was no evidence of a reduction of postoperative mechanical ventilation exceeding 48 hours in the groups receiving preoperative IMT (RR 0.55; 95% CI 0.03 to 9.20; P value = 0.68; I2 statistic = 56%) (Analysis 1.4). We noted a large degree of heterogeneity and wide confidence intervals, including important benefit and potential harm, so we downgraded this outcome for inconsistency and imprecision. As with the other outcomes regarding PPCs, small‐study effects may be present; we therefore also downgraded this outcome for publication bias. As a result, we rated the quality of evidence as very low quality and effect is uncertain.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 4 PPC; mechanical ventilation > 48 hours.

2. All‐cause mortality within 30 days during postoperative period

Seven trials reported on all‐cause mortality within the postoperative period (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006b; Soares 2013). In four trials, there were zero events in both groups (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Heynen 2012). In the remaining three trials, we could pool all‐cause postoperative death in a meta‐analysis (Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006b; Soares 2013), because Ferreira 2009 reported all‐cause mortality within a 30‐days postoperative period, whereas Hulzebos 2006b and Soares 2013 reported all‐cause postoperative mortality. The analysis found the effect of IMT on all‐cause postoperative death is uncertain (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.04 to 4.23; P value = 0.09; I2 statistic = 59%) (Analysis 1.5). We noted a large degree of heterogeneity and wide confidence intervals, including important benefit and potential harm, so we downgraded the outcome for inconsistency and imprecision. We also downgraded the outcome for publication bias because small‐study effects may be present. As a result, we rated the quality of evidence as very low quality and effect is uncertain.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 5 All‐cause postoperative death.

3. Adverse events

Eight trials provided reports of adverse events (Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010). All these trials reported that there were no adverse events in both groups (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 6 Adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

1.1. Maximal inspiratory muscle strength; Pi‐max

Eleven trials reported the data on maximal inspiratory muscle training strength (Pi‐max) (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013; Weiner 1998). We considered the clinically relevant outcome to be the change of Pi‐max between baseline and three postoperative days, rather than the final value of Pi‐max after the surgery. We therefore planned to pool the change scores of Pi‐max in the meta‐analysis. Six trials reported the data on Pi‐max, both before and after surgery (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Ferreira 2009; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). Three trials provided sufficient information, such as the P value or standard deviations (SDs) of the Pi‐max at both time points, to calculate the change scores (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Ferreira 2009). Three trials reported the mean or median of Pi‐max, however the mean and SDs of the change score were unavailable despite our contacting the authors (Carvalho 2011; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). We a priori planned to impute the missing SDs from other trials, but as the remaining two trials reported quite different SDs, we therefore did not pool this one trial in the meta‐analysis. Our analysis found that preoperative IMT was not associated with improved Pi‐max (mean difference (MD) ‐7.87; 95% CI ‐21.36 to 5.61; P value = 0.25; I2 statistic = 0%) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 7 Maximal inspiratory muscle strength; Pi‐max (postoperative change from preoperative baseline).

1.2. Respiratory muscle endurance; Pm‐peak/Pi‐max

Three trials reported the data about respiratory muscle endurance (Pm‐peak/Pi‐max) (Hulzebos 2006b; Soares 2013; Weiner 1998). Only one trial reported the change scores from baseline to postoperative status (Weiner 1998). However, as SDs of the change score were unavailable, we did not pool this one trial in the meta‐analysis.

2. Duration of hospital stay

Eight trials reported duration of hospital stay (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2010; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010). However, in two trials the median and range of hospital stay between groups were reported, and it was impossible to calculate the mean and SD of hospital stays (Heynen 2012; Kulkarni 2010). We could therefore pool the mean duration of hospital stay in the remaining six trials in a meta‐analysis. The analysis found that preoperative IMT was associated with reduced length of hospital stay (MD ‐1.33; 95% CI ‐2.53 to ‐0.13; P value = 0.03; I2 statistic = 7%) (Figure 7). Although we noted no heterogeneity between trials, small‐study effects may be present. We therefore downgraded the outcome for publication bias in addition to risk of bias and rated the quality of evidence as low quality.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, outcome: 1.8 Duration of hospital stay.

3. Other types of complications within 30 days during postoperative period

One trial reported the occurrence of other types of early postoperative complication, that is cardiac complications, neurological complications, or surgical‐site infections (Ferreira 2009). This trial reported that there is no statistically significant difference regarding postoperative heart failure; experimental 1/15 (67%) versus control 1/15 (67%), P value = 0.65.

4. Total drop‐out from the study for any reason, as surrogate measure of overall acceptability

Ten trials reported on dropouts (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). In five of the 10 trials there is no drop‐out participant between both groups (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Ferreira 2009; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b). In the remaining five trials that reported on drop‐out (Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Heynen 2012; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013;), the proportion of loss to follow‐up was higher than 20% in two trials (Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). All trials that reported dropouts described the reasons for drop‐out in each case. There was no difference between participants allocated to the intervention group and those allocated to the control group for discontinuation from trials due to any cause (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.36 to 1.51; P value = 0.40; I2 statistic = 0%) (Analysis 1.9). As we mentioned earlier, five trials reported zero events, therefore we conducted post‐hoc analysis using risk difference (RD) instead of RR because the RD method can include trials with zero events in both arms into the analysis. The analysis found no evidence of significant difference between groups (RD ‐0.00; 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.01; P value = 0.95; I2 statistic = 0%).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 9 Total drop‐out from the study.

5. Quality of life

One trial with 42 participants reported on quality of life (Dronkers 2010). In this trial, there were no significant differences across the groups as measured by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ‐ C30 version 3 designed for patients with cancer (Kaasa 1995)) that evaluated quality of life based on global health status/functional scale/symptom scale (see Table 2). It was impossible to conduct a meta‐analysis of this data due to the small number of studies and participants.

1. Quality of life.

| Baseline (before intervention) | Outcome (after surgery) | ||

| EORTC QLQ‐C30/GH | intervention group | 70 | 72 |

| (Global Health Status) | control group | 71 | 68 |

| EORTC QLQ‐C30/FS | intervention group | 408 | 413 |

| (Functional Scale) | control group | 427 | 425 |

| EORTC QLQ‐C30/SC | intervention group | 154 | 119 |

| (Symptom Scale) | control group | 130 | 155 |

EORTC QLQ‐C30: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire‐Core 30: a quality‐of‐life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology

6. Cost analysis

No trial provided reports of cost analysis.

Subgroup analysis

We performed pre‐planned subgroup analysis for our primary outcome only when a meaningful number of relevant trials had been identified.

1. Type of surgery

We performed subgroup analysis according to the type of surgery, that is cardiac surgery and major abdominal surgery. In the cardiac surgery subgroup, pooled analysis showed preoperative IMT was associated with a reduction of postoperative atelectasis and pneumonia compared with usual care or non‐exercise intervention (Figure 4; Figure 5). On the other hand, in the major abdominal surgery subgroup, pooled analysis showed that preoperative IMT was associated with a reduction of postoperative atelectasis, still not associated with a reduction of postoperative pneumonia even though a number of pooled trials were not meaningful for this subgroup analysis (Figure 4; Figure 5). Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 statistic = 0.57, df = 1 (P value = 0.45), I2 statistic = 0% (postoperative atelectasis) and Chi2 statistic = 0.00, df = 1 (P value = 0.96), I2 statistic = 0% (postoperative pneumonia).

2. High‐risk participants

Three trials included only participants with "high risk" factors for PPCs (the definition of "high risk" depended on the trial) (Dronkers 2008; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b). The other trials did not restrict inclusion to high‐risk participants and did not report the results of high‐risk participants separately. We attempted to contact the relevant trial authors to identify the risk factors of the included participants, but were unable to obtain this information. It was therefore not meaningful to carry out this pre‐planned subgroup analysis because of the small number of trials.

3. Type of intervention

In 10 of the 12 included trials, the intervention was simply preoperative IMT with threshold device (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Dronkers 2008; Ferreira 2009; Heynen 2012; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Weiner 1998). In the other two trials, the intervention was a mixed training programme including IMT (Dronkers 2010; Soares 2013). Dronkers 2010 reported only data on pneumonia for the primary outcome. We therefore performed subgroup analysis about postoperative pneumonia according to the type of intervention, that is simple IMT intervention and mixed training programme including IMT. In the simple IMT intervention subgroup, pooled analysis showed preoperative simple IMT was associated with a reduction of postoperative pneumonia compared with usual care or non‐exercise intervention (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.88; P value = 0.02) (Figure 6). Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 statistic = 0.67, df = 1 (P value = 0.41), I2 statistic = 0% (postoperative pneumonia).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed pre‐planned sensitivity analysis about the primary outcome only when we had identified a meaningful number of relevant trials. None of the sensitivity analyses led to a change in the main findings regarding the PPCs.

1. Excluding trials with high or unclear risk of bias in allocation concealment

After excluding the trials with high or unclear risk of bias with respect to allocation concealment, we included six trials in this analysis (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). Five of those six trials adequately reported postoperative atelectasis (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Soares 2013), and five of six trials adequately reported postoperative pneumonia (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Kulkarni 2010; Soares 2013). The result was consistent with the main findings regarding the incidence of postoperative atelectasis (Analysis 1.10) and of postoperative pneumonia (Analysis 1.11).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 10 Sensitivity analysis; PPC; Atelectasis (Excluding studies with high risk or unclear risk of bias in allocation concealment).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 11 Sensitivity analysis; PPC; Pneumonia (Excluding studies with high risk or unclear risk of bias in allocation concealment).

2. Excluding trials in which the primary outcome evaluation was not blinded

After excluding trials with a high or unclear risk of bias with respect to the blinding of outcome assessment, five trials adequately blinded the outcome assessors (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008; Dronkers 2010; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b). Of these five trials, we finally included in this analysis four that adequately reported postoperative atelectasis (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2008; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b) and four that adequately reported postoperative pneumonia (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Dronkers 2010; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b). The main findings regarding the incidence of postoperative atelectasis (Analysis 1.12) and of postoperative pneumonia (Analysis 1.13) did not change.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 12 Sensitivity analysis; PPC; Atelectasis (Excluding studies with high risk or unclear risk of bias in blinding of outcome assessment).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 13 Sensitivity analysis; PPC; Pneumonia (Excluding studies with high risk or unclear risk of bias in blinding of outcome assessment).

3. Performing the worst‐ and best‐case scenario analysis

Intention‐to‐treat analysis of RCTs regarding the incidence of postoperative pneumonia is the best‐case scenario. In a worst‐case‐scenario analysis, participants who drop out are treated as incident cases of postoperative pneumonia. Pooled analysis of this worst‐case scenario was consistent with the main findings regarding the incidence of postoperative atelectasis (Analysis 1.14) and of postoperative pneumonia (Analysis 1.15).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 14 Sensitivity analysis; PPC; Atelectasis (worst‐case scenario analysis).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training (IMT) versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, Outcome 15 Sensitivity analysis; PPC; Pneumonia (worst‐case scenario analysis).

4. Fixed‐effect or random‐effects models

Repetition of the analysis using a fixed‐effect model was consistent with the main findings regarding the incidence of PPCs.

5. Excluding trials that used original authors' definition of PPCs and included no outcome based on our definition

It was not meaningful to carry out this pre‐planned sensitivity analysis because all the trials used different original authors' definitions for PPCs.

Funnel plot analysis

As stated in the protocol for this review, we conducted funnel plot analysis for the incidence of pneumonia (Katsura 2013). The funnel plot showed asymmetrical appearance with a gap in the bottom corner of the graph (Figure 8), but Egger's test was not statistically significant (P value = 0.22). When we carried out the trim‐and‐fill imputation as a sensitivity check, the overall results did not change materially (the imputed RR = 0.41).

8.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Preoperative inspiratory muscle training versus usual care, non‐exercise intervention, outcome: 1.2 PPC; Pneumonia (Type of surgery).

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this systematic review and meta‐analysis, we compared the effectiveness of preoperative IMT and usual preoperative care on PPCs in adult participants undergoing cardiac or major abdominal surgery. We identified and pooled the data of 12 trials, of which five included participants awaiting elective cardiac surgery and seven included participants awaiting elective major abdominal surgery. The included trials did not report on all of the outcomes that were described in the protocol of this review (Katsura 2013). The present review showed that preoperative IMT was associated with a reduction of postoperative atelectasis and pneumonia, compared with usual care or non‐exercise intervention (respectively; RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.82 and RR 0.45; 95% CI 0.26 to 0.77). However, the effect of preoperative IMT on all‐cause postoperative mortality is uncertain (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.04 to 4.23) and needs further investigation. We found no trial that reported the incidence of adverse events caused by preoperative IMT.

When we considered secondary outcomes, the analysis found that preoperative IMT was associated with reduced length of hospital stay (MD ‐1.33; 95% CI ‐2.53 to ‐0.13). On the other hand, we found no evidence of a significant difference in the change score regarding Pi‐max between the preoperative baseline before intervention and postoperative period (MD ‐7.87; 95% CI ‐21.36 to 5.61); however, there were only three pooled trials.

We have presented the main findings of this review in Table 1. However, several points need to be considered when interpreting the present findings, as the majority of studies were small and rated as being at an unclear or high risk of bias.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Although this review answered our research questions, the number of included trials was small for some of the outcomes. It is known that most large treatment effects emerge from small‐sized trials, and all included trials but one were small‐sized. The salutary effect of the intervention might have derived from small‐sized trials (Pereira 2012), and so cautious interpretation and application are necessary. Our review included 10 trials from around the world, but six of them were from high‐income countries, including five from the Netherlands and one from the United Kingdom. The accessibility to the threshold device might limit the applicability of IMT with threshold device into the clinical practice.

Quality of the evidence

We included 12 trials with 695 participants in our review. Of the 12 trials we pooled 11 in the meta‐analysis on the incidence of pneumonia and 10 on the meta‐analysis on the incidence of drop‐out. Meta‐analyses on the other outcomes included a small number of trials (three to seven). The sample size of each of the 12 trials was small, except for one trial that comprised 276 participants (Hulzebos 2006b). The incidence of PPCs was relatively small in each trial. We assessed only one trial as at low risk of bias in all domains except the domain of performance bias (Hulzebos 2006b). We assessed all trials as at unclear or high risk of bias for the domain of performance bias. According to the GRADE Working Group guidelines for evaluating the impact of healthcare interventions, the overall quality of the trials for the incidence of pneumonia was moderate, whereas the overall quality of the trials for the incidence of atelectasis, all‐cause postoperative death, and duration of hospital stay was low or very low.

Potential biases in the review process

In order to minimize the risk of publication bias, we conducted an extensive search without language restrictions, and attempted to include three conference proceedings (Carvalho 2011; Da Cunha 2013; Heynen 2012). We also attempted to contact all of the authors of the included trials for information that was not reported in the published articles or proceedings. We gained necessary information regarding some outcomes, but were unable to obtain all of the information regarding other outcomes and trial designs. We also contacted the companies who supply respiratory muscle training devices, but information regarding any ongoing trials was unavailable. This limitation might introduce a source of bias. It is also possible that, as the funnel plot for the incidence of pneumonia suggests (Figure 8), there remains the possibility of small‐study effects and publication bias for this outcome.

Another concern is that the largest trial, Hulzebos 2006b, weighed nearly 50% in some primary analyses. It is possible that these outcomes were heavily influenced by this one trial (Hulzebos 2006b). However, this trial is free of any major bias and is large in the sample size, and may therefore accurately represent the necessity of preoperative IMT. We therefore decided to include this trial in the analysis.

We needed to make several changes to the protocol methods (Katsura 2013). Firstly, we included all reported data on PPCs, because most trials used their own definitions of PPCs, and because only a limited number of trials reported the outcomes of interest to us. Secondly, we also considered trials that used interventions that differed slightly from those in our original protocol (Katsura 2013): a trial where participants were required to have IMT five days a week, in Da Cunha 2013, and a trial where participants were assigned to start from 10% of maximal inspiratory pressure and to work incrementally, in Dronkers 2010. We believed that including these trials might enhance the applicability and understanding of preoperative IMT and find enough credibility in the clinical community. Thirdly, we also included two trials that employed complex mixed interventions consisting of preoperative IMT and exercise training (Dronkers 2010; Soares 2013). We subsequently examined the efficacy of these trials as well as those trials that met our original eligibility criteria in a subgroup analysis; while we found the statistical significance only in the simple IMT intervention subgroup, the direction of the effect size in the subgroup of the complex mixed intervention was the same (Figure 6).

While we found no heterogeneity between trials in the analysis of postoperative atelectasis, pneumonia, and duration of hospital stay, we found a large degree of heterogeneity in the analysis of mechanical ventilation exceeding 48 hours and all‐cause postoperative death. There were not enough trials in these analyses to enable subgroup analysis or meta‐regression analysis to be performed to investigate the cause of heterogeneity. Given the small number of trials for these outcomes, the effect is uncertain and the generalizability on these outcomes might also be limited.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

As far as we know, there exist two other recent systematic reviews focusing on preoperative physical therapy including IMT (Hulzebos 2012; Valkenet 2011). These reviews evaluated the efficacy of preoperative physical therapy with an exercise component. Hulzebos 2012 included participants awaiting cardiac surgery, while Valkenet 2011 included participants awaiting invasive surgery including cardiac, abdominal, or joint replacement surgery. Both studies concluded that preoperative physical therapy prevents some postoperative complications including atelectasis and pneumonia. We understand that their studies will have a few RCTs in common with ours, but we think that our proposed title can still be meaningful for the following reasons. We are interested in "inspiratory muscle training for major cardiac or abdominal surgery", and the other two review authors are interested in "physical exercise training for cardiac surgery or invasive surgery". We believe that the effectiveness of IMT is homogeneous across cardiac or abdominal surgeries (which is why we included the two in our review), and that excluding abdominal surgeries would make our estimate of the effectiveness of IMT less precise (that is with wider confidence intervals). Furthermore, "physical exercise training" will include therapeutic exercise programme and muscle endurance training in addition to IMT, and they will not directly answer our clinical question of whether we should regularly recommend IMT to our patients. The other reviews could perform subgroup analyses on IMT for abdominal surgeries, but then again such subgroup analyses will suffer from unnecessarily wide confidence intervals.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In high‐volume centres, many patients usually wait longer than two weeks for their elective surgery. Preoperative IMT could be easily performed in the outpatient setting (for example at home or in a local rehabilitation clinic) under the supervision of a physiotherapist, and with no adverse events reported. We found evidence that preoperative IMT is associated with a reduction of postoperative atelectasis, pneumonia, and duration of hospital stay. Preoperative IMT therefore appears to be a suitable preparation for elective surgery, especially for people on the waiting list for high‐risk major cardiac and abdominal surgery. It is important to note that as the quality of evidence is low to moderate, the potential for overestimation of treatment effect needs to be considered when interpreting the present findings.

Implications for research.

More high‐quality RCTs are needed to evaluate the postoperative benefit of preoperative IMT, especially for major abdominal surgery. Further studies should be more specific in their definition of PPCs and uniform in their descriptions regarding the change score of Pi‐max and the risk of bias. Other types of surgery associated with a high risk of PPCs, such as oesophagogastric resection and other non‐cardiac surgery, should be evaluated. Future studies need to assess whether a further increase of the dose and intensity of IMT influences its effect in reducing PPCs. Evaluations of the cost‐effectiveness of preoperative IMT and patient‐reported outcomes are also greatly desired.

Notes

We would like to thank Mathew Zacharias (content editor), Cathal Walsh (statistical editor), and Rik Gosselink and Andrezza Lemos (peer reviewers) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of the protocol, Katsura 2013, for the systematic review.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jane Cracknell (Managing Editor, Cochrane Anaesthesia, Critical and Emergency Care Group) and Karen Hovhannisyan (Trials Search Co‐ordinator) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of the protocol, Katsura 2013, and this systematic review.

We would like to thank Rodrigo Cavallazzi (content editor), Cathal Walsh (statistical editor), Peter Hartley and Tom J Overend (peer reviewers), and Anne Lyddiatt (consumer referee) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review.