Abstract

Phages able to infect the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora were isolated from apple, pear, and raspberry tissues and from soil samples collected at sites displaying fire blight symptoms. Among a collection of 50 phage isolates, 5 distinct phages, including relatives of the previously described phages φEa1 and φEa7 and 3 novel phages named φEa100, φEa125, and φEa116C, were identified based on differences in genome size and restriction fragment pattern. φEa1, the phage distributed most widely, had an approximately 46-kb genome which exhibited some restriction site variability between isolates. Phages φEa100, φEa7, and φEa125 each had genomes of approximately 35 kb and could be distinguished by their EcoRI restriction fragment patterns. φEa116C contained an approximately 75-kb genome. φEa1, φEa7, φEa100, φEa125, and φEa116C were able to infect 39, 36, 16, 20, and 40, respectively, of 40 E. amylovora strains isolated from apple orchards in Michigan and 8, 12, 10, 10, and 12, respectively, of 12 E. amylovora strains isolated from raspberry fields (Rubus spp.) in Michigan. Only 22 of 52 strains were sensitive to all five phages, and 23 strains exhibited resistance to more than one phage. φEa116C was more effective than the other phages at lysing E. amylovora strain Ea110 in liquid culture, reducing the final titer of Ea110 by >95% when added at a ratio of 1 PFU per 10 CFU and by 58 to 90% at 1 PFU per 105 CFU.

Fire blight, caused by the bacterium Erwinia amylovora, is a devastating disease of apple and pear trees in North America, Europe, the Mediterranean region, and New Zealand. Most pear and apple cultivars currently in commercial production are moderately to highly susceptible to fire blight. The pathogen is also able to infect a few other members of the Rosaceae, including pyracantha, hawthorn, and cotoneaster. A distinct subtype of E. amylovora is able to cause fire blight on Rubus spp., especially raspberry and blackberry, but not on apple and pear shoots or seedlings (14, 19). Except for differences in genetic fingerprints (11, 12), strains isolated from Rubus spp. are indistinguishable from tree fruit E. amylovora strains.

Preventing the buildup of epiphytic populations of E. amylovora on nutrient-rich stigmatic surfaces of blossoms in the spring is the main strategy for controlling fire blight (6, 22). Streptomycin is no longer effective for controlling epiphytic E. amylovora on blossoms in many fruit-growing regions because of the emergence of streptomycin-resistant strains of the pathogen (7). A new strategy for hindering the establishment of epiphytic E. amylovora on stigmas is the use of bacteria such as Pseudomonas fluorescens strain A506 (9), Pantoea agglomerans strain C9-1 (13, 20), and a few other species (8, 13), but so far the level and consistency of control with microbial agents are lower than those with antibiotics (6). Phages of E. amylovora have been proposed as possible control agents for fire blight. The control potential of an E. amylovora phage was first demonstrated by Erskine in 1973 (3). Subsequently, symptoms of fire blight were attenuated in apple seedlings inoculated with φEa1 in conjunction with E. amylovora (15) and in pear fruit inoculated with E. amylovora in the presence of a φEa1-encoded polysaccharide depolymerase (5). Phages of E. amylovora have commonly been found on aerial parts and in soils associated with fire blight-infected apple trees (3, 15, 16), but the association of phage with fire blight-infected Rubus spp. has not been investigated. Except for cloning a polysaccharide depolymerase gene from φEa1 (5), genetic methods have not been used to study E. amylovora-specific phages.

In this study the diversity of E. amylovora phages recovered from soils and shoots of fire blight-infected plants was evaluated. Phages were characterized using PCR, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The phage sensitivity of a panel of E. amylovora strains and the ability of the phage to lyse broth cultures of E. amylovora were examined. The ability to definitively identify phages is prerequisite to future epidemiological and control studies of fire blight using phage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, phages, and media.

E. amylovora strain Ea110, isolated in 1975 as strain MSU110 from a canker on Jonathan apple in an experimental orchard near East Lansing, Mich. (15), and phage φEa1, isolated in 1975 as phage PEa1 from blighted Jonathan apple shoots collected near Paw Paw, Mich. (15), were obtained from John S. Hartung, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, Md. (5, 16). Phage φEa7, isolated in 1976 as phage PEa7 from blighted apple shoots collected near Berrien Springs, Mich. (15), was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC 29780-B2). Phages φEa100, φEa104, φEa125, and φEa116C were isolated in this study and deposited at the American Type Culture Collection as ATCC 29780-B4, 29780-B5, 29780-B3, and 29780-B6, respectively. Forty strains of E. amylovora were collected from 14 apple orchards located in six counties of Michigan during 1997 and 1998. Their identity was confirmed based on their colony color and morphology on MM2Cu and Luria-Bertani (LB) media (2) and by PCR assay with the AJ75-AJ76 primer pair (10). E. amylovora strains MR1, -2, -3, and -4; RBA4, -8, -10, and -E; and RKK2, -3, -4, and -5 were collected from three raspberry farms in Michigan (11). Other bacteria included seven nonfluorescent and nine fluorescent strains of Pseudomonas spp. and 12 strains of Pantoea agglomerans previously isolated from Michigan apple orchards (18). Bacteria were routinely cultured on LB agar and in LB broth. The double-layer agar technique (1) was used to produce phage plaques on bacterial hosts, using a top agar consisting of 11.5 g of nutrient agar, 5 g of glucose, and 5 g of yeast extract per liter on a bottom agar of 23 g of nutrient agar and 5 g of glucose per liter.

Isolation of phage.

Samples were collected from an asymptomatic apple orchard at Michigan State University, several fire blight-infected commercial apple and pear orchards in southern Michigan, a fire blight-infected apple orchard in northern California, and a raspberry farm in northern Michigan in 1996 and 1997. Aerial tissues (i.e., branches, leaves, and fruit) and/or soil from within the tree dripline were mixed with sterile water. The collected washes were treated with chloroform at a final concentration of 5%. Aliquots (100 μl) were mixed with 100 μl of Ea110 culture at an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 to 3.0, plated, and assessed for the presence of plaques following 18 h of incubation. Phage were recovered from individual plaques by soaking isolated agar plugs in 1 ml of 100 mM NaCl–50 mM Tris-HCl(pH 7.5)–8 mM MgSO4 for at least 1 h. Phage were purified using successive rounds of single-plaque isolation.

Isolation of phage DNA.

Ea110 was grown overnight in LB broth with agitation at 28°C and diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.14 (approximately 2 × 108 CFU/ml). Bacteriophage (2 × 107 PFU) were mixed with 1 ml of diluted bacteria. Following a 10-min incubation, 9 ml of LB broth was added and the cultures were grown overnight at 28°C with agitation. Chloroform (30 μl) was added, and bacterial debris was removed by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 15 min. DNA was purified either by using the Wizard Lambda DNA Preps DNA Purification System (Promega, Madison, Wis.) or by phenol extraction of concentrated phage. In the latter case, the cleared bacterial lysate was incubated for 30 min at 37°C following addition of 40 μl of nuclease mix (0.25 mg each of DNase and RNase per ml in 150 mM NaCl–50% [wt/vol] glycerol). Four milliliters of 33% polyethylene glycol 8000–3.3 M NaCl was then added, and the mixture was incubated on ice for at least 30 min followed by centrifugation in 15-ml Corex tubes (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of 150 mM NaCl–40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–10 mM MgSO4 and clarified by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge for 2 min. The supernatant fluid was extracted twice with chloroform. Phage DNA was then released by gentle mixing in an equal volume of Tris-buffered phenol (pH 7.9) for 5 min. After centrifugation for 5 min, the upper layer was extracted again with phenol and then with chloroform. DNA was precipitated by the addition of 1 ml of 95% ethanol and 50 μl of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2), collected by centrifugation for 15 min, rinsed with 300 μl of 70% ethanol, allowed to dry, and gently resuspended in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–0.1 mM EDTA.

φEa1 PCR assay.

BglII restriction fragments of φEa1 were ligated into BamHI-digested, dephosphorylated pGEM3zf(+); ligation products were introduced into Escherichia coli strain JM109 by electroporation, and selected transformants were analyzed. A clone containing a 1.8-kb BglII fragment was partially sequenced (GenBank accession no. AF222715). Based on this sequence, PCR primers were designed to amplify a 304-bp fragment from φEa1 (PEa1A 5′-AATGGGCACCGTAAGCAGT and PEa1B 5′-TAATGGGTATGATAGAAGGCAGAC). PCR reaction mixtures (20 μl) consisted of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM (each) primer, 0.16 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (Gibco BRL) and 1 μl of phage lysate containing 104 to 107 PFU of phage. Reactions were performed in a PTC-150 minicycler (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.) with cycling parameters of 95°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 53°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Reaction products were analyzed on 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer run at 10 V/cm, followed by ethidium bromide staining.

Restriction analysis of phage DNA.

Purified phage DNA was subjected to restriction analysis according to the manufacturers' protocols (Gibco BRL and Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.). The samples were electrophoresed either through 0.8% agarose in 0.5× TBE buffer at 6 V/cm for 1 to 2 h or through 0.4% agarose in 0.5× TBE buffer at 1 V/cm for 18 to 24 h. The sizes of the fragments were estimated by comparison to HindIII-digested λ DNA, high-molecular-weight DNA standards, or the 1-kb DNA Plus ladder (Gibco BRL). Restriction maps were constructed by compiling the data from single- and double-enzyme digestions of intact and cloned BglII fragments of phage DNA.

Contour-clamped homogeneous electric field gel analysis.

Pulsed-field gels were run using a CHEF-DR II PFGE system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). The 1% gels were made with Seakem (Rockland, Maine) Gold agarose in 0.5× TBE buffer. The pulsed-field parameters were as follows: 0.5× TBE running buffer, 0.1-s initial switch time, 10-s final switch time, 6.0 V/cm, 15-h run time, and 14°C buffer temperature. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized using a Foto/Eclipse system (Fotodyne, Inc., Harland, Ws.).

Infection and lysis experiments.

Aliquots (50 μl) of overnight cultures of various strains were mixed with 103 PFU of phage (as determined by plaque formation using strain Ea110 as a standard), incubated for 10 min, mixed with 3 ml of top agar, and plated onto bottom agar. Following incubation at 22°C for 18 to 42 h, the plates were evaluated for the presence of plaques. Strain and phage combinations which yielded no plaques were retested at least twice.

Overnight cultures of Ea110 were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.007 (approximately 107 CFU/ml), and 1-ml aliquots were infected with 1.0 × 102, 1.0 × 104, and 1.0 × 106 PFU of a single phage; 0.5 × 102, 0.5 × 104, and 0.5 × 106 PFU of each of two phages; and 0.33 × 102, 0.33 × 104, and 0.33 × 106 PFU of each of three phages. Three 1-ml aliquots were grown without phage as a control. The cultures were incubated overnight at 28°C with agitation. Bacterial densities were assessed by measuring the optical density of the cultures at 600 nm. Percent growth was calculated for each experiment by dividing the optical densities by the average optical density of the cultures grown without phage. The percent growth values for three experiments were pooled and analyzed by analysis of variance.

RESULTS

Identification of phage types.

The collection of phages that formed plaques on the E. amylovora Ea110 host consisted of reference phages φEa1 and φEa7 and 48 new isolates collected in 1996 and 1997. Forty-four of the new isolates were from Michigan, including 41 from soil and plant material of fire blight-infected apple orchards, 2 from blighted raspberry canes, and 1 from a blighted pear shoot. Four additional isolates came from soil collected in a fire blight-infected apple orchard in California.

The phage isolates were characterized by plaque morphology and tested for the presence of a φEa1 sequence by PCR. Forty-two isolates, including φEa1 and isolates from Michigan and California tree fruit orchards, produced large plaques surrounded by an expanding translucent halo similar to those previously described for φEa1 and yielded a 0.3-kb PCR fragment when tested with φEa1 primers (data not shown). These isolates were categorized as presumptive φEa1 isolates.

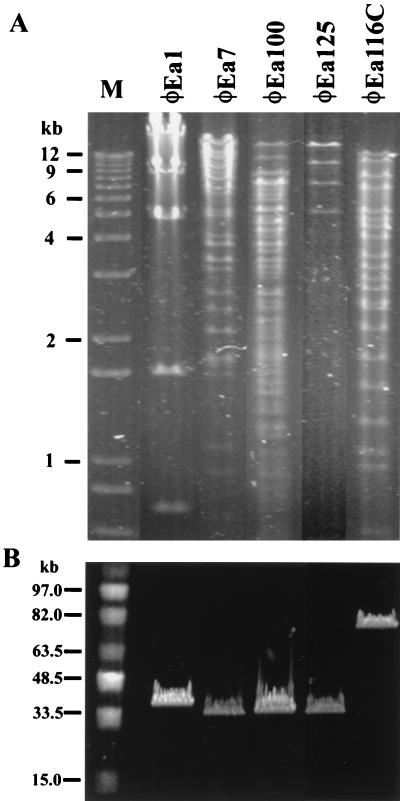

The remaining eight isolates generated small plaques and produced no PCR product with the φEa1 primers. EcoRI restriction analysis of DNAs from these isolates yielded four patterns distinct from the EcoRI profile of φEa1 represented by φEa7, soil sample isolates from Michigan (φEa100) and California (φEa125), and a Michigan apple orchard isolate (φEa116C) (Fig. 1A). The two isolates from raspberry and two additional isolates from Michigan apple orchards showed patterns identical to that of φEa7 (data not shown). DNAs from isolates representing the five EcoRI restriction patterns were analyzed by PFGE (Fig. 1B). The genome sizes of these phages were estimated to be 46 kb (φEa1), 35 kb (φEa7), 35 kb (φEa100), 35 kb (φEa125), and 75 kb (φEa116C).

FIG. 1.

Restriction analysis and pulsed-field gel analysis of DNAs from E. amylovora phages φEa1, φEa7, φEa100, φEa125, and φEa116C. (A) EcoRI restriction digestion analysis of phage DNA. Lane M, 1-kb Ladder Plus (Gibco BRL). (B) PFGE of phage DNA. Lane M, MidRange I PFG Marker (New England BioLabs, Inc.).

For φEa1, φEa125, and φEa116C the sums of the lengths of the observed EcoRI restriction fragments were in agreement with the genome size estimates from the PFGE analysis. In contrast, the sums of the lengths of the EcoRI restriction fragments of φEa7 and φEa100 greatly exceeded the genome sizes observed by PFGE, suggesting that the restriction digestions may have been incomplete. To test whether the presence of impurities was causing partial digestion, the DNA samples were subjected to additional phenol and chloroform extractions and ethanol precipitation followed by restriction digestion with high levels of EcoRI for 16 h. The resulting digestion patterns were identical to those originally observed (data not shown), suggesting that impurities were not responsible for the observed patterns.

Restriction analysis of φEa1-type isolates.

To verify that the presence of the 0.3-kb PCR product was accurately identifying φEa1-type phage, BglII restriction digests of DNAs from four PCR-positive isolates and φEa1 were compared (Fig. 2). The digest of φEa1 DNA yielded fragments of approximately 9, 7, 6.5, 6.2, 5.2, 3.5, 3, 2.1, 1.6, and 1.4 kb. Isolate φEa123 yielded a pattern identical to that of φEa1. The three other isolates exhibited restriction patterns similar to, but distinct from, that of φEa1. These three isolates were distinguished from φEa1 by the absence of the 9-, 6.5-, and 5.2-kb fragments and the presence of fragments of 14 kb; 3.8, 4.3, or 4.8 kb for isolates φEa101, φEa104, and φEa109, respectively; and 1.7 kb.

FIG. 2.

BglII restriction analysis of DNAs from φEa1 and putative φEa1-type phages isolated from Michigan (φEa101, φEa104, and φEa109) and California (φEa123). Lane M, 1-kb Ladder Plus (Gibco BRL). An additional 14 phages, each yielding a 0.3-kb PCR product typical for φEa1, had restriction patterns similar to these.

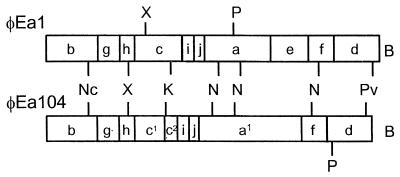

To assess the similarity between these isolates, restriction maps were constructed for φEa1 and φEa104 using restriction enzymes BglII, NcoI, XbaI, KpnI, NdeI, PvuII, and PstI (Fig. 3). Overall the maps were very similar, with single-site variations possibly accounting for differences in one BglII site (separating fragments a and e) and two PstI sites (within fragments a and d). A region of variability was detected between the third BglII site and the KpnI site. In φEa104 this region was approximately 0.5 kb shorter than in φEa1, it lacked the second XbaI site found in φEa1, and it contained a BglII site not found in φEa1, suggesting that an alternate sequence may be present in this region.

FIG. 3.

Restriction maps of E. amylovora phage isolates φEa1 and φEa104. Fragments a to j represent the longest to shortest BglII fragments of φEa1. Corresponding BglII fragments of φEa104 are indicated with the same letter designation; fragments a1, c1, and c2 are unique to φEa104. Other restriction sites in common between φEa1 and φEa104 are indicated between the two maps, and those unique to each phage are indicated above or below the φEa1 and φEa104 maps, respectively. B, BglII; K, KpnI; Nc, NcoI; N, NdeI; Pv, PvuII; X, XbaI.

An additional 13 PCR-positive isolates from Michigan analyzed by BglII digestion yielded patterns similar to those of φEa101, φEa104, and φEa109, and one additional isolate from California yielded a BglII pattern identical to that of φEa1 (data not show). These data support the grouping of all PCR-positive isolates as φEa1-type phages.

Host range of E. amylovora phages.

To assess the prevalence of phage resistance in natural populations of E. amylovora, the ability of phages φEa1, φEa7, φEa100, φEa125, and φEa116C to infect 40 strains of E. amylovora isolated from apple was tested in a plaque formation assay (Table 1). Resistance to at least one phage was detected in 65% of the strains. Resistance to φEa100 and φEa125 was found in 50 and 60% of the strains, respectively; resistance to both of these phages was found in 45% of the strains. Resistance to the other three phages was less common. φEa116C formed plaques on all 40 strains, a single strain was resistant to φEa1, and four strains were resistant to φEa7. Ninety percent of the strains were sensitive to phages φEa1, φEa7, and φEa116C.

TABLE 1.

Sensitivity of each of 52 strains of E. amylovora to phages

| No. of E. amylovora strains from the following hosta:

|

Plaques formed with the following phageb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malus spp. (n = 40 strains) | Rubus spp. (n = 12 strains) | φEa1 | φEa7 | φEa100 | φEa125 | φEa116C |

| 17 | 0 | + | + | − | − | + |

| 14 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | 0 | + | + | − | + | + |

| 2 | 0 | + | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | 0 | + | − | − | + | + |

| 1 | 0 | + | − | − | − | + |

| 1 | 0 | − | − | − | + | + |

| 0 | 2 | − | + | + | + | + |

| 0 | 2 | − | + | − | − | + |

Phages were tested on strains of E. amylovora from Malus spp. collected in six Michigan counties in 1998 (2 to 14 per county) and on strains from Rubus spp. collected at three sites in Michigan in 1994. Each strain was mixed with 103 PFU of each phage and plated using the double-layer agar technique.

Phage sensitivity plates were evaluated following 18 to 36 h of incubation. +, plaques present; −, no plaques. The total numbers of strains infected were as follows: φEa1, 47; φEa7, 48; φEa100, 26; φEa125, 30; φEa116C, 52.

Strains of E. amylovora which are capable of causing disease on Rubus spp. are genetically distinct from strains which cause disease on other rosaceous plants such as apple and pear (11, 12). To assess differences in phage sensitivity between the two distinct types of E. amylovora strains, 12 strains of E. amylovora isolated from Rubus hosts were also tested for their sensitivity to the phages. Eight strains were sensitive to all five phages. Four strains (all RKK strains) were resistant to φEa1; two of these strains (RKK2 and RKK5) were also resistant to φEa100 and φEa125.

φEa1, φEa7, and φEa116C were screened for ability to infect other common orchard bacterial isolates. A collection of nonfluorescent (7 strains) and fluorescent (9 strains) Pseudomonas strains and Pantoea agglomerans (12 strains) were challenged with 103 PFU of each phage. No plaques formed on any of the strains.

Lysis of E. amylovora strain Ea110 in liquid culture.

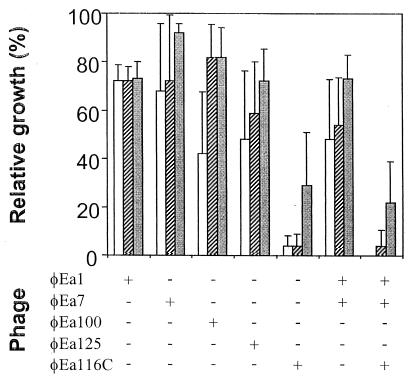

The ability of the phages to control populations of E. amylovora was tested by infecting liquid cultures of E. amylovora with individual phages or with combinations of phages φEa1, φEa7, and φEa116C (Fig. 4). Data for the seven phage treatments and three phage concentrations were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance. F values for treatments and phage concentrations were highly significant (P = 0.00001), and interaction effects were not significant. When φEa1, φEa7, φEa100, φEa125, and φEa116C were added individually to cultures of E. amylovora strain Ea110 at 1 PFU per 10 CFU or 1 PFU per 103 CFU, only φEa116C was able to effectively control bacterial populations, reducing optical densities to 96% ± 4% below that of bacteria grown without phage. A mixture of phages φEa1 and φEa7 was not significantly better than either phage alone in controlling bacterial populations. A mixture of phages φEa116C, φEa1, and φEa7 was as effective as φEa116C alone.

FIG. 4.

Control of growth of E. amylovora strain Ea110 in the presence of phage(s). Single phage types (φEa1, φEa7, φEa100, φEa125, or φEa116C) or combinations of equal proportions of two or three phages (φEa1 plus φEa7 or φEa1 plus φEa7 plus φEa116C) were added at 106) (open bars), 104 (hatched bars), and 102 (solid bars) total PFU to 1-ml aliquots of LB broth containing 107 CFU of E. amylovora strain Ea110. The optical densities of the cultures following 18 h of growth at 28°C were compared to the optical densities of cultures grown without phage. The data shown are the averages of three replications, with the standard deviation of each mean shown.

DISCUSSION

Five distinct E. amylovora phages were identified from a collection of 50 phage isolates. By cloning and sequencing a 1.8-kb BglII fragment of φEa1, a set of PCR primers specific for detection of φEa1-type phages was developed and used to screen the collection; others have also found these primers useful for rapidly differentiating φEa1 from other phages (4). Phages φEa7, φEa100, φEa125, and φEa116C, which were distinct from φEa1, were differentiated based on genome size and restriction fragment pattern. The analysis of these phages at the DNA level provides a basis for the characterization of future phage isolates.

Phages specific for E. amylovora were prevalent in Michigan orchard sites with active fire blight infections, and the detection of phages during the later stages of fire blight epidemics in apple orchards is consistent with the results of an earlier Michigan study (15). Nearly every site surveyed yielded φEa1-type isolates, indicating that this phage is commonly associated with E. amylovora in nature. Two major subtypes of φEa1-type phages were observed among the isolates based on restriction analysis. The first group included the original φEa1 isolate and the φEa1-type isolates from California; all of these isolates had identical EcoRI restriction patterns. The second group included the more recent isolates from Michigan, which produced somewhat variable EcoRI restriction patterns which were quite distinct from that of the original φEa1 isolate.

For the other four phages, our collection contained either single isolates (φEa100, φEa125, and φEa116C) or five isolates (φEa7). The five isolates of φEa7 displayed no obvious differences in restriction pattern even though two of the isolates were associated with E. amylovora from raspberry canes, which represent a genetically distinct and often spatially isolated host. It is not clear if the paucity of these phages in our collection was due to their scarcity in the collected samples or to difficulties in identifying the small plaques formed by these phages. Because our discovery of phages distinct from φEa1 was somewhat fortuitous, it may be reasonable to suppose that additional E. amylovora phage types exist.

One explanation for the insensitivity of some strains of E. amylovora to phages may be that they harbor temperate phages that render them resistant to other lytic phages. However, this appears unlikely, because Ritchie (15) tested strains of E. amylovora resistant to φEa1 or φEa7 for lysogeny using UV light and mitomycin C as induction agents; all tests were negative for temperate phage. Another indication of the presence of temperate phages is the formation of hazy plaques; none of the phages were observed to form plaques that became hazy in the center with age. As reported previously (15, 16), φEa1-type phages produced plaques with a distinct halo after about 18 h. This halo was shown to be the result of the production of a polysaccharide depolymerase, capable of hydrolyzing the capsular polysaccharide and not of lysogeny (5, 16).

Ritchie and Klos (15, 16) reported that φEa1 and φEa7 infected each of 20 E. amylovora isolates; however, our data from additional strains indicate that some strains differ in their phage sensitivity. All 52 strains of E. amylovora from Malus and Rubus hosts were infected by phage φEa116C. Although a more exhaustive screen might yield strains with resistance to φEa116C, it appears that resistance to this phage is rare. Among Malus strains of E. amylovora, 40 to 98% were infected by the other four phages. Apparently, despite the high degree of homogeneity among tree fruit strains of E. amylovora, some strains possess differences that prevent adherence, uptake, or replication by certain phages. The specific nature of the mechanisms responsible for phage resistance in the E. amylovora strains is unknown. The majority of the E. amylovora strains from Rubus were sensitive to all five phages, although resistance to φEa1, φEa100, and φEa125 was detected. This is the first study to show that Rubus and Malus strains of E. amylovora were infected by the same phages.

Despite the ability of each of the phages to infect E. amylovora strain Ea110, only φEa116C was able to drastically reduce the final density of the bacteria grown in liquid culture. In the case of φEa1, it has been shown that as phage titers increase, a phage-encoded polysaccharide depolymerase, which is able to degrade the capsule of E. amylovora, accumulates in the medium. When levels of the enzyme are high enough, φEa1 can no longer infect the bacteria, presumably due to destruction of φEa1 binding sites (5, 15). For φEa7, φEa100, and φEa125, the reasons for ineffective growth control are unknown.

The phages isolated in this study may be useful for biocontrol of E. amylovora, in particular φEa116C and, to a lesser extent, φEa1 and φEa7, because of the infrequent occurrence of resistant strains in E. amylovora populations. They might be effective either in orchards or for eliminating E. amylovora from the surface of contaminated budwood and fresh fruit. Control of the blossom-infection stage of fire blight is critical to the overall control of fire blight (6). E. amylovora multiplies on the stigmatic surfaces of blossoms prior to blossom infection (22). If E. amylovora-specific phages were present on the blossoms, they might suppress the growth of E. amylovora on the stigmatic surfaces. However, natural phage populations are below detectable levels during the bloom period (reference 16 and this study). Therefore, any control strategy based on phage would require that blossoms be treated with phage in much the same way as blossoms are treated with antagonistic bacteria. Prior colonization of the blossom by a suitable host, such as an avirulent strain of E. amylovora (21), has been shown to be important for the establishment and maintenance of phage populations (17). Without such a host the population of phage rapidly declined, presumably due to UV light or desiccation effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Monica Meyer and Katalin Kása for their assistance with experiments reported here and W. G. D. Fernando for his help in the isolation of phages in 1997.

This research was supported in part by the Rackham Endowment Fund, the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station, and USDA/CSREES Agreement 97-34367-3967.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M H. Bacteriophages. New York, N.Y: Interscience Publishers; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bereswill S, Jock S, Bellemann P, Geider K. Identification of Erwinia amylovora by growth morphology on agar containing copper sulfate and by capsule staining with lectin. Plant Dis. 1998;82:158–164. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erskine J M. Characteristics of Erwinia amylovora bacteriophage and its possible role in the epidemiology of fire blight. Can J Microbiol. 1973;19:837–845. doi: 10.1139/m73-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill J J, Svircev A M, Myers A L, Castle A J. Biocontrol of Erwinia amylovora using bacteriophage. Phytopathology. 1999;89:S27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartung J S, Fulbright D W, Klos E J. Cloning of a bacteriophage polysaccharide depolymerase gene and its expression in Erwinia amylovora. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1988;1:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson K B, Stockwell V O. Management of fire blight: a case study in microbial ecology. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1998;36:227–248. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.36.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones A L, Schnabel E L. The development of streptomycin resistant strains of Erwinia amylovora. In: Vanneste J L, editor. Fire blight: the disease and its causative agent Erwinia amylovora. Wallingford, Oxon, United Kingdom: CAB International; 2000. pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearns L P, Hale C N. Partial characterization of an inhibitory strain of Erwinia herbicola with potential as a biocontrol agent for Erwinia amylovora, the fire blight pathogen. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:369–374. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindow S E, McGourty G, Elkins R. Interactions of antibiotics with Pseudomonas fluorescens A506 in the control of fire blight and frost injury of pear. Phytopathology. 1996;86:841–848. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McManus P S, Jones A L. Detection of Erwinia amylovora by nested PCR and PCR-dot-blot and reverse-blot hybridizations. Phytopathology. 1995;85:618–623. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McManus P S, Jones A L. Genetic fingerprinting of Erwinia amylovora strains isolated from tree-fruit crops and Rubus spp. Phytopathology. 1995;85:1547–1553. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Momol M T, Momol E A, Lamboy W F, Norelli J L, Beer S V, Aldwinckle H S. Characterization of Erwinia amylovora strains using random amplified polymorphic DNA fragments (RAPDs) J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:389–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pusey P L. Crab apple blossoms as a model for research on biological control of fire blight. Phytopathology. 1997;87:1096–1102. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.11.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ries S M, Otterbacher A G. Occurence of fire blight on thornless blackberry in Illinois. Plant Dis Rep. 1977;61:232–235. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritchie D. Bacteriophages of Erwinia amylovora: their isolation, distribution, characterization, and possible involvement in the etiology and epidemiology of fire blight. Ph. D. thesis. East Lansing: Michigan State University; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritchie D F, Klos E J. Isolation of Erwinia amylovora bacteriophage from the aerial parts of apple trees. Phytopathology. 1977;67:101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnabel E L, Fernando W G D, Jackson L E, Meyer M P, Jones A L. Bacteriophage of Erwinia amylovora and their potential for biocontrol. Acta Hortic. 1998;489:649–654. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnabel E L, Jones A L. Distribution of tetracycline resistance genes and transposons among phylloplane bacteria in Michigan apple orchards. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4898–4907. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4898-4907.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starr M P, Cardona C, Folsom D. Bacterial fire blight of raspberry. Phytopathology. 1951;41:915. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stockwell V O, Johnson K B, Loper J E. Establishment of bacterial antagonists of Erwinia amylovora on pear and apple blossoms as influenced by inoculum preparation. Phytopathology. 1998;88:506–513. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tharaud M, Laurent J, Faize M, Paulin J-P. Fire blight protection with avirulent mutants of Erwinia amylovora. Microbiology. 1997;143:625–632. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomson S V. The role of stigma in fire blight infections. Phytopathology. 1986;76:476–482. [Google Scholar]