Abstract

The obesity paradox has been observed in short-term outcomes from critical illness. However, little is known regarding the impact of obesity on long-term outcomes for survivors of critically ill patients. We aimed to evaluate the influence of obesity on long-term mortality outcomes after discharge alive from ICU. The adult patients who were discharged alive from the last ICU admission were extracted. After exclusion, a total of 7619 adult patients discharged alive from ICU were included, with 4-year mortality of 32%. The median body mass index (BMI) was 27.2 (IQR 24–31.4) kg/m2, and 2490 (31.5%) patients were classified as obese or morbidly obese. The morbidly obese patients had the highest ICU and hospital length of stay. However, higher BMI was associated with lower hazard ratio for 4-year mortality. The results showed the obesity paradox may be also suitable for survivors of critically ill patients.

Keywords: Obesity paradox, Critical care, Survivors, Mortality

Background

Survivors of critically ill patients are at risk of experiencing significant physical, cognitive, and mental health issues, which were associated with an increased mortality following discharge from intensive care unit (ICU) [1–4]. However, factors associated with mortality for survivors of critical illness are not well understood, which may be important when counseling patients and families.

The obesity paradox, which is the phenomenon that obesity increases the risk of obesity-related diseases but paradoxically is associated with survival benefits, has been observed in short-term outcomes from critical illness [5–7]. Nonetheless, little is known regarding the impact of obesity on long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit (ICU).

We, therefore, aimed to evaluate the influence of obesity on 4-year mortality outcome for survivors of critically illness.

Methods

Data were extracted from the online database Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC III) [8]. We included adult patients who were discharged alive from the last ICU admission. The exclusion criteria were: (1) No weight and height data available, (2) body mass index (BMI) < 10 kg/m2 or > 70 kg/m2, (3) No follow-up survival data available.

We abstracted the height and weight data from the Electronic Medical Records (EMR) when admitted to ICU. The BMI was calculated using the equation: BMI (kg/m2) = weight (kg)/height2 (m2). BMI was examined as both a categorical and continuous variable. According to the international standards [9], obesity was assessed as a categorical variable according to BMI (BMI less than 10.0 or greater than 70.0 kg/m2 was excluded): underweight, BMI < 18.5 k kg/m2; normal weight, 18.5 ≤ BMI < 25 kg/m2; overweight, 25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2; obese, 30 ≤ BMI < 40 kg/m2; morbidly obese, BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2.

The primary endpoint was 4-year mortality which was extracted from the social security database and was considered as a time-to-event variable.

Baseline and clinical characteristics were compared among different BMI categories. Multiple imputation was used to deal with the missing data with the mice package [10]. We used Cox proportional hazards regression model to produce adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for the association between BMI and 4-year mortality with normal weight as reference. To better understand the effect of BMI on 4-year mortality as a continuous covariate in multivariable Cox model, the splines-based HR curve was expressed with smoothHR package [11]. The PostgreSQL (version 10, www.postgresql.org) was used for data extraction, and R software (version 3.5.1, www.r-project.org) was used to conduct all the statistical analysis.

Results

After exclusion, 7619 adult patients discharged alive from ICU were included, with 4-year mortality of 32% (Table 1). The median BMI was 27.2 (IQR 24–31.4) kg/m2. 2490 (31.5%) patients were classified as obese or morbidly obese. As expected, higher BMI patients had a higher percentage of comorbidities of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. The morbidly obese patients had the highest ICU and hospital length of stay. The underweight patients had the highest 4-year mortality (62%). The higher BMI was associated with lower HR for 4-year mortality.

Table 1.

Baseline and clinical characteristics of the study patients by BMI categories

| Variables | Total | Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) | Normal weight (18.5 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 25 kg/m2) | Overweight (25 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2) | Obese (30 kg/m2 ≤ BMI < 40 kg/m2) | Morbidly obese (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 7916 (100) | 206 (2.6) | 2368 (29.9) | 2852 (36.0) | 2065 (26.1) | 425 (5.4) |

| Age, years | 65 (54, 76) | 69 (55, 78) | 69 (54, 79) | 66 (55, 76) | 63 (54, 73) | 58 (50, 66) |

| Sex: male | 5023 (63) | 80 (39) | 1371 (58) | 2014 (71) | 1349 (65) | 209 (49) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.2 (24.0, 31.4) | 17.4 (16.4, 18.1) | 22.9 (21.5, 24.0) | 27.3 (26.2, 28.5) | 33.0 (31.4, 35.3) | 44.1 (41.7, 48.1) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 5397 (68) | 129 (63) | 1608 (68) | 1951 (68) | 1405 (68) | 304 (72) |

| Others | 2519 (32) | 77 (37) | 760 (32) | 901 (32) | 660 (32) | 121 (28) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 4373 (55) | 80 (39) | 1245 (53) | 1660 (58) | 1171 (57) | 217 (51) |

| Single | 1511 (19) | 59 (29) | 466 (20) | 513 (18) | 364 (18) | 109 (26) |

| Widowed | 1009 (13) | 34 (17) | 366 (15) | 320 (11) | 250 (12) | 39 (9) |

| Divorced | 469 (6) | 13 (6) | 111 (5) | 169 (6) | 142 (7) | 34 (8) |

| Others | 554 (7) | 20 (10) | 180 (8) | 190 (7) | 138 (7) | 26 (6) |

| Insurance type | ||||||

| Medicare | 4007 (51) | 126 (61) | 1315 (56) | 1418 (50) | 983 (48) | 165 (39) |

| Private | 3171 (40) | 64 (31) | 796 (34) | 1183 (41) | 916 (44) | 212 (50) |

| Medicaid | 452 (6) | 13 (6) | 150 (6) | 157 (6) | 97 (5) | 35 (8) |

| Government | 197 (2) | 3 (1) | 66 (3) | 64 (2) | 54 (3) | 10 (2) |

| Self-pay | 89 (1) | 0 (0) | 41 (2) | 30 (1) | 15 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 4457 (56) | 94 (46) | 1169 (49) | 1622 (57) | 1325 (64) | 247 (58) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2077 (26) | 33 (16) | 445 (19) | 663 (23) | 754 (37) | 182 (43) |

| Tumor | 525 (7) | 22 (11) | 182 (8) | 175 (6) | 119 (6) | 27 (6) |

| Respiratory disease | 1212 (15) | 52 (25) | 375 (16) | 357 (13) | 321 (16) | 107 (25) |

| CHF | 2146 (27) | 61 (30) | 662 (28) | 731 (26) | 548 (27) | 144 (34) |

| Liver disease | 273 (3) | 6 (3) | 97 (4) | 96 (3) | 65 (3) | 9 (2) |

| Renal failure | 643 (8) | 25 (12) | 202 (9) | 219 (8) | 160 (8) | 37 (9) |

| ICU types | ||||||

| CCU | 1341 (17) | 24 (12) | 397 (17) | 511 (18) | 338 (16) | 71 (17) |

| MICU | 3803 (48) | 64 (31) | 1071 (45) | 1438 (50) | 1062 (51) | 168 (40) |

| CSRU | 1191 (15) | 67 (33) | 379 (16) | 368 (13) | 289 (14) | 88 (21) |

| SICU | 906 (11) | 31 (15) | 272 (11) | 312 (11) | 235 (11) | 56 (13) |

| TSICU | 675 (9) | 20 (10) | 249 (11) | 223 (8) | 141 (7) | 42 (10) |

| ICU scoring systems | ||||||

| SOFA score | 4 (2, 6) | 4 (2, 5) | 4 (2, 6) | 4 (2, 6) | 4 (2, 6) | 4 (2, 6) |

| SAPS II | 31 (24, 40) | 36 (28, 43) | 33 (25, 41) | 31 (24, 39) | 30 (23, 39) | 30 (22, 40) |

| ICU LOS, days | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | 4 (2, 7) |

| Hospital LOS, days | 8 (6, 13) | 9 (6, 16) | 8 (6, 13) | 8 (6, 12) | 8 (6, 13) | 9 (6, 16) |

| Hospital discharge location | ||||||

| Home | 1980 (25) | 46 (22) | 539 (23) | 768 (27) | 535 (26) | 92 (22) |

| Home health care | 3003 (38) | 52 (25) | 852 (36) | 1144 (40) | 806 (39) | 149 (35) |

| Rehabilitation center | 1364 (17) | 44 (21) | 441 (19) | 420 (15) | 355 (17) | 104 (24) |

| Hospice | 60 (1) | 3 (1) | 21 (1) | 24 (1) | 6 (0) | 6 (1) |

| Skilled nurse facility | 1077 (14) | 48 (23) | 383 (16) | 348 (12) | 251 (12) | 47 (11) |

| Others | 432 (5) | 13 (6) | 132 (6) | 148 (5) | 112 (5) | 27 (6) |

| Four-year mortality | 2571 (32) | 127 (62) | 920 (39) | 821 (29) | 582 (28) | 121 (28) |

Data are median (interquartile range) or No/Total (%)

BMI body mass index, CHF chronic heart failure, CKD chronic kidney disease, ICU intensive care unit, CCU Coronary Care Unit, CSRU Cardiac Surgery Recovery Unit, TSICU Trauma Surgical ICU, MICU Medical ICU, SICU Surgical ICU, SOFA sequential organ failure assessment, SAPS Simplified acute physiology score, LOS length of stay

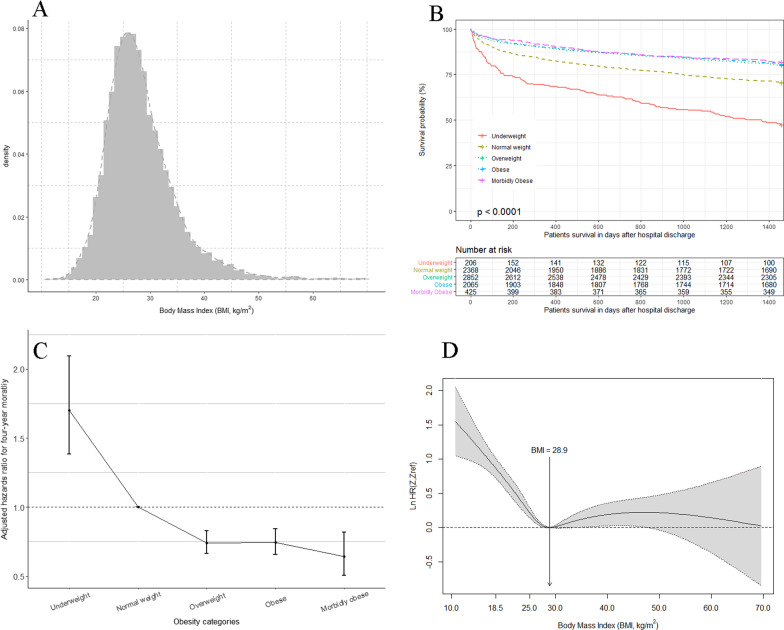

Underweight and normal-weight patients had a lower probability of 4-year survival (Fig. 1B). When considering normal-weight patients as the reference, underweight patients had higher adjusted HR for mortality, while overweight and obese patients had lower adjusted HRs (Fig. 1C). When using BMI as a continuous variable, the pointwise estimation of the adjusted HR curve showed a nonlinear relationship between BMI and long-term mortality outcome, with a BMI of 28.9 kg/m2 the lowest HR (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

A Histogram and density distribution of body mass index (BMI); B Kaplan–Meier survival curves by BMI category (log-rank p < 0.001); C Adjusted hazards ratio (HR) for 4-year mortality according to BMI categories, with normal weight as reference. The HRs and 95% confidence intervals (error bars) for each categories were calculated using COX proportional hazard model after adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, insurance type, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, tumor, respiratory disease, chronic heart failure, liver disease, and renal failure), ICU type, disease severity score of simplified acute physiology score (SAPS) II, and hospital discharge locations; D Smoothed HR (log transformation) curve with pointwise nonparametric estimation of association between BMI and 4-year mortality after adjusting for confounders (same with the confounders in C)

Discussion

In the present study, a significant proportion of patients discharging from ICU survive less than 4 years. Among survivors of critical illness, obesity was associated with lower 4-year mortality.

The high mortality of survivors discharging from ICU was in line with previous studies [12, 13]. In the study of Brinkman et al. [12], the mortality risk at 3 years after hospital discharge was 27.5%; and the 5 years mortality was 26.9% in the study of Doherty et.al, which was higher than the general age-matched population [13]. In view of the prevalence of obesity continuing to rise among the ICU population [6], efforts to understand the impact of obesity long-term outcomes after critical illness should also be important [14]. The present study showed the mortality was high for ICU survivors and obesity was associated with reduced mortality; However, the underlying mechanisms were unknown. Several pathophysiologic mechanisms including higher energy reserves, anti-inflammatory immune profile, role of adipose tissue, and prevention of muscle wasting may contribute to explain this phenomenon [5]. Interestingly, according to the recent study of Drago et al. [15], the relationship of increasing BMI and lower risk of hypoglycemia might contribute to decreased mortality.

The concept of obesity paradox has also been challenged. Martino et.al found that extreme obesity was not associated with a worse survival advantage after adjusted for confounders as well as had a longer duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU length of stay [16]. On the other hand, the BMI as a composite variable is intrinsically problematic, which is not an appropriate measure of fat and skeletal muscle mass and its distribution [17]. In the studies of Jaitovich et al. [18, 19], ICU admission pectoralis muscle area or erector spinae muscle mass was associated with survival outcomes, not was the subcutaneous adipose tissue mass. Similar studies were sparse for ICU survivors. As for survivors of critically ill patients, it is unclear whether it reflects a protective effect or limitations inherent to observational research for obesity paradox, which warrants further research.

There were several limitations to our study. First, the retrospective design in nature was subjected to the inherent limitations even though adjusted for potential confounders. The other confounding factors including smoking status, alcohol consumption, income, education, physical activity, and dietary pattern may be involved, which were not extracted from the database. Second, the ICU admission height and weight data were extracted from the EMR with a higher missing rate. The method (estimation or measurement) for recording the height and weight was unknown. Third, the weight was a variable parameter relying on fluid balance, which could cause perturbation for calculation of BMI. As a result of these limitations, the present findings warrant a cautious interpretation, and more prospective cohort studies are needed to further elucidate this phenomenon.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that the obesity paradox may be also suitable for survivors of critically ill patients.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- EMR

Electronic medical records

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- MIMIC

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care

Author contributions

DW Z and T L conceived this study. DW Z extracted the data. T L, DW Z, and C W designed and performed the statistical analyses. DW Z and Q L wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DW Z and T L reviewed and modified the final manuscript. All authors read, critically reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Foundation of Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. 2021-YJJ-ZZL-026).

Availability of data and materials

Data analyzed during the present study are currently stored in the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC III) (mimic.mit.edu).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All information was obtained from the MIMIC III database and was anonymized. Due to the HIPAA compliant de-identification in this database, our IRB requirement was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

None of the authors has declared a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, Griffiths J, Harrison DA, Watkinson P. Anxiety, depression and post traumatic stress disorder after critical illness: a UK-wide prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2223-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lima V, Bierrenbach AL, Alencar GP, Andrade AL, Azevedo LCP. Increased risk of death and readmission after hospital discharge of critically ill patients in a developing country: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(7):1090–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilcox ME, Girard TD, Hough CL. Delirium and long term cognition in critically ill patients. BMJ. 2021;373:n1007. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashem MD, Nallagangula A, Nalamalapu S, Nunna K, Nausran U, Robinson KA, Dinglas VD, Needham DM, Eakin MN. Patient outcomes after critical illness: a systematic review of qualitative studies following hospital discharge. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):345. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1516-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karampela I, Chrysanthopoulou E, Christodoulatos GS, Dalamaga M. Is there an obesity paradox in critical illness? Epidemiologic and metabolic considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9(3):231–244. doi: 10.1007/s13679-020-00394-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schetz M, De Jong A, Deane AM, Druml W, Hemelaar P, Pelosi P, Pickkers P, Reintam-Blaser A, Roberts J, Sakr Y, et al. Obesity in the critically ill: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(6):757–769. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05594-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepper DJ, Sun J, Welsh J, Cui X, Suffredini AF, Eichacker PQ. Increased body mass index and adjusted mortality in ICU patients with sepsis or septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):181. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1360-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson AE, Pollard TJ, Shen L, Lehman LW, Feng M, Ghassemi M, Moody B, Szolovits P, Celi LA, Mark RG. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible Critical Care database. Scientific data. 2016;3:160035. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pi-Sunyer FXBD, Bouchard C, Carleton RA, Colditz GA, Dietz WH, et al. Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(17):1855–1867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z. Multiple imputation with multivariate imputation by chained equation (MICE) package. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(2):30. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.12.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meira-Machado L, Cadarso-Suárez C, Gude F, Araújo A. smoothHR: an R package for pointwise nonparametric estimation of hazard ratio curves of continuous predictors. Comput Math Methods Med. 2013;2013:745742. doi: 10.1155/2013/745742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinkman S, de Jonge E, Abu-Hanna A, Arbous MS, de Lange DW, de Keizer NF. Mortality after hospital discharge in ICU patients. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(5):1229–1236. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827ca4e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doherty Z, Kippen R, Bevan D, Duke G, Williams S, Wilson A, Pilcher D. Long-term outcomes of hospital survivors following an ICU stay: A multi-centre retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0266038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tremblay A, Bandi V. Impact of body mass index on outcomes following critical care. Chest. 2003;123(4):1202–1207. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plečko D, Bennett N, Mårtensson J, Bellomo R. The obesity paradox and hypoglycemia in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):378. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03795-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martino JL, Stapleton RD, Wang M, Day AG, Cahill NE, Dixon AE, Suratt BT, Heyland DK. Extreme obesity and outcomes in critically ill patients. Chest. 2011;140(5):1198–1206. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weig T, Irlbeck T, Frey L, Paprottka P, Irlbeck M. Above and beyond BMI : Alternative methods of measuring body fat and muscle mass in critically ill patients and their clinical significance. Anaesthesist. 2016;65(9):655–662. doi: 10.1007/s00101-016-0205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaitovich A, Khan M, Itty R, Chieng HC, Dumas CL, Nadendla P, Fantauzzi JP, Yucel RM, Feustel PJ, Judson MA. ICU admission muscle and fat mass, survival, and disability at discharge: a prospective cohort study. Chest. 2019;155(2):322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaitovich A, Dumas CL, Itty R, Chieng HC, Khan M, Naqvi A, Fantauzzi J, Hall JB, Feustel PJ, Judson MA. ICU admission body composition: skeletal muscle, bone, and fat effects on mortality and disability at hospital discharge-a prospective, cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):566. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03276-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data analyzed during the present study are currently stored in the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC III) (mimic.mit.edu).