Highlights

-

•

Population-based data on COVID-19 seroprevalence in Zanzibar were analyzed.

-

•

57% of this representative cohort were positive for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2.

-

•

The highest seroprevalence was observed in adolescents.

-

•

No regional seroprevalence hotspots were detected in Unguja or Pemba.

-

•

The results form the basis for a follow-up survey on susceptibility to the Omicron variants.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Tanzania, epidemiology, cross-sectional, population-based

Abstract

Objectives

For Tanzania, including Zanzibar, the development of the COVID-19 pandemic has remained unclear since the reporting of cases was suspended during 2020/21. Our study was the first to analyze data on COVID-19 seroprevalence in the Zanzibari population before the Omicron variant wave began in late 2021.

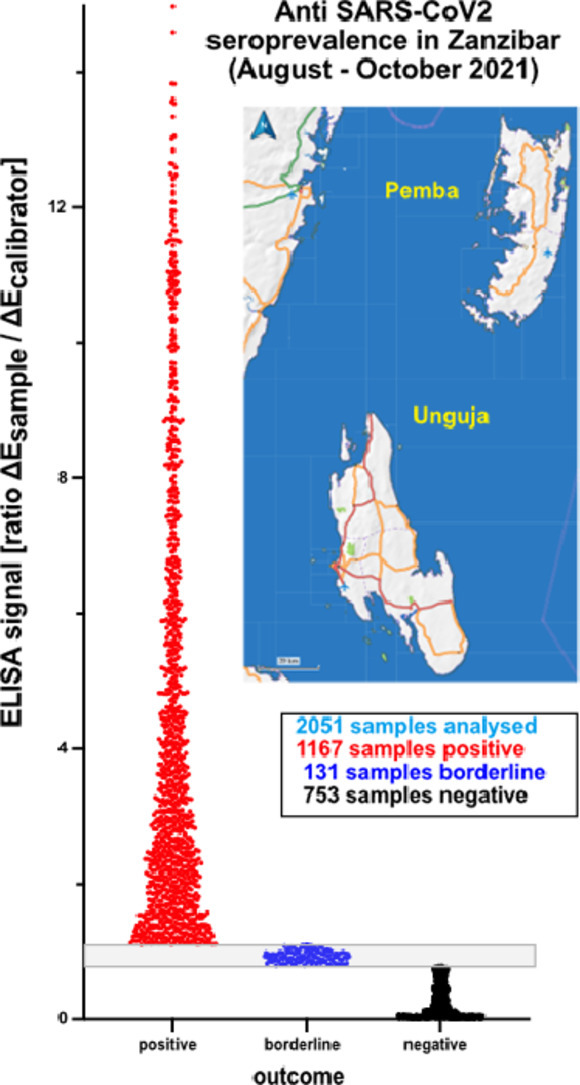

Design

During August through October 2021, representative cross-sectional data were collected from randomly selected households in 120 wards of the two main islands, Unguja and Pemba. Participants voluntarily provided blood samples to test their sera for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 using a semiquantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results

58.9% of the 2051 sera analysed were positive, without significant differences between Unguja and Pemba or between rural and urban areas. The results were in agreement with observations from other sub-Saharan African countries.

Conclusions

The antibody levels observed were most likely due to previous infections with SARS-CoV-2, since vaccination was generally not available before the survey. Therefore, this study offers the first insights into how many Zanzibari had COVID-19 before the Omicron variant emerged. Furthermore, it provides an appropriate basis for a follow-up survey addressing how this seroprevalence has influenced susceptibility to the Omicron variants, given the use of harmonized methodologies.

Graphical abstract

Background

COVID-19 was declared as a global pandemic in early 2020. Following the first case reports in March 2020 (WHO, 2022), Tanzania implemented a range of protective measures. However, in May 2020 Tanzania stopped reporting COVID-19 cases to WHO, and most restrictions were lifted by May 18th. In mid 2021, Tanzania resumed reporting, including previously detected COVID-19 cases, resulting in 33 836 confirmed cases and a death toll of 803 by April 1, 2022 (The United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health, 2022). These data clearly showed COVID-19 waves for April–June 2020, January–March 2021, and June–August 2021, coinciding with the original, Alpha, and Delta variant waves, as well as for the Omicron variants from December 2021 through March 2022 (The United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health, 2022).

Herd (or population) immunity is achieved if a sufficient proportion of a population has acquired immunity, through natural infection or vaccination, to prevent further spread of the pathogen. To achieve this for COVID-19, vaccination is the most efficient and preferred way, according to WHO (WHO, 2020), although the proportion that must be vaccinated to effect herd immunity is still not known. While several efficient vaccines have been produced, in most sub-Saharan Africa countries these have only become available late and in low numbers. Zanzibar began vaccination in July 2021 (Mikofu, 2021), with vaccination coverage in Tanzania including Zanzibar remaining at around 5% (The United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health, 2022).

While confirmed COVID-19 cases correspond to only 0.5% of the population, an unknown number of SARS-CoV-2 infections must be expected. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies can provide essential information (Bobrovitz et al., 2021). Our study, carried out in in 2021, was the first to provide data on COVID-19 seroprevalence in the Zanzibari population before the Omicron variant wave started in November 2021.

Methods

Study area, study design, and sampling

This cross-sectional study was designed to provide representative seroprevalence data from the main islands, Unguja and Pemba. 120 of the total 388 wards (Shehias) were randomly selected, covering both urban and rural areas. 354 randomly selected households were visited from July 28 through October 20, 2021. All household members were enrolled, irrespective of their age or sex, as in a previous survey (Nyangasa et al., 2016). All eligible participants gave written consent in an entirely voluntary manner after all relevant information had been provided in the local language.

Venous blood samples were collected into clotting activation tubes and transported to the laboratory for processing. Following centrifugation, serum was stored at −80°C.

Laboratory analysis

The EUROIMMUN Anti-SARS-CoV-2 ELISA (IgG) kit provided a semiquantitative analysis in detecting human IgG antibodies against the S1 domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, thus indicating prior infections, and has been recommended for seroprevalence surveys such as this (Gededzha et al., 2021). Using the kit's calibrator, a ratio-based analysis (OD of sample/OD of calibrator) of the obtained data was performed to differentiate between negative (ratio below 0.8), positive (ratio above 1.1), and borderline cases. According to the manufacturer's information, this kit offered a positive agreement of 90% (95% CI = 73.5–97.9%), counting borderlines as negative, and a negative agreement of 100.0% (95% CI = 95.5–100.0%).

Results and discussion

Until now, the frequency of SARS-CoV-2 infections causing COVID-19 in Tanzania has been unknown. Seroprevalence provides important information on how many individuals have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 before sampling. Our study was the first report on anti-SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in the Zanzibar population. In total, 2071 participants (66.2% of 3143) from 349 (98.6%) households in this survey provided blood samples, from which 2051 serum samples were available to be tested for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG; 56.9% of these samples were positive. Since vaccination against COVID-19 had not been generally available to participants, the antibodies detected were likely to have been induced by preceding SARS-CoV-2 infection(s) during the various COVID-19 waves (The United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health, 2022).

Seroprevalence was relatively evenly distributed, with only minor differences observed (Table 1), resulting in no significant differences (p > 0.9999) between Unguja and Pemba. On Unguja, the seroprevalences observed in the urban districts of Magharibi and Mjini were lower, whereas on Pemba the lowest level recorded was in Micheweni, a rural district (Table 1). Prevalence was slightly higher in males compared with female participants. The highest seroprevalence was observed in adolescents (p > 0.9137) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Regional seroprevalences; total number of tests conducted in Unguja and Pemba and their respective districts, with seropositivity as a percentage.

| District | Seropositive, N (%) | Seronegative, N (%) | Borderline, N (%) | Total, N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (Unguja) | 773 (57.1%) | 486 (35.9%) | 94 (6.9%) | 1353 |

| North A (Kaskazini A, Unguja) | 84 (56.8%) | 53 (35.8%) | 11 (7.4%) | 148 |

| North B (Kaskazini B, Unguja) | 93 (62.4%) | 49 (32.9%) | 7 (4.7%) | 149 |

| Central (Kati, Unguja) | 160 (58.4%) | 93 (33.9%) | 21 (7.7%) | 274 |

| South (Kusini, Unguja) | 81 (59.1%) | 50 (36.5%) | 6 (4.4%) | 137 |

| West (Magharibi, Unguja) | 159 (53.4%) | 122 (40.9%) | 17 (5.7%) | 298 |

| Urban (Mjini, Unguja) | 196 (56.5%) | 119 (34.3%) | 32 (9.2%) | 347 |

| Total (Pemba) | 394 (56.4%) | 267 (38.3%) | 37 (5.3%) | 698 |

| Chake Chake (Pemba) | 112 (60.5%) | 59 (31.9%) | 14 (7.6%) | 185 |

| Micheweni (Pemba) | 85 (50.6%) | 74 (44.0%) | 9 (5.4%) | 168 |

| Mkoani (Pemba) | 127 (56.2%) | 89 (39.4%) | 10 (4.4%) | 226 |

| Wete (Pemba) | 70 (58.8%) | 45 (37.8%) | 4 (3.4%) | 119 |

| Total (Zanzibar) | 1167 (56.9%) | 753 (36.7%) | 131 (6.4%) | 2051 |

Table 2.

Sex and age distribution of seroprevalences; total number and percentage of tests conducted.

| Population tested | Seropositive, N (%) | Seronegative, N (%) | Borderline, N (%) | Total, N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 626 (56.1%) | 416 (37.3%) | 74 (6.6%) | 1116 |

| Male | 541 (57.9%) | 337 (36.0%) | 57 (6.1%) | 935 |

| Age group < 10 years | 152 (51.9%) | 125 (42.7%) | 16 (5.5%) | 293 |

| Age group 10–13 years | 173 (61.6%) | 97 (34.8%) | 10 (3.6%) | 280 |

| Age group 14–16 years | 121 (66.5%) | 49 (26.9%) | 12 (6.6%) | 182 |

| Age group 17–59 years | 601 (54.9%) | 412 (37.7%) | 81 (7.4%) | 1094 |

| Age group ≥ 60 years | 120 (59.4%) | 70 (34.7%) | 12 (5.9%) | 202 |

| Total participants | 1167 (56.9%) | 753 (36.7%) | 131 (6.4%) | 2051 |

In summary, this first population-based survey uncovered widespread SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity across all districts of Zanzibar prior to the onset of the current Omicron-dominated wave. Overall, the seroprevalences observed were similar to those observed in other sub-Sahara Africa countries (Lewis et al., 2022).

At present, this level of seroprevalence cannot be considered as herd immunity, since it is uncertain how antibody levels correlate with virus neutralization, protection against reinfection, symptomatic cases, and asymptomatic cases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; Hamady et al., 2022). In this respect, future studies comparing the seroprevalences reported here with the situation during/after the Omicron variant wave could provide important information, especially if using identical tools to correlate analyses with neutralising activities against Omicron and previous variants in these sera.

Funding sources

Financial support was provided by the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) PAGEL Program (Project MENTION) to SK (University Bremen) and SSS (State University Zanzibar), and by the EU's Erasmus+ International Mobility Program to University Bremen. The funding agencies had no influence on the study design or the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; nor were they involved on the decision to submit the manuscript.

Ethical approval statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans, and was approved by the Second Vice President Office and the Zanzibar Ministry of Health through the Zanzibar Medical Research and Ethics Committee (ZAMREC/0001/AUGUST/013).

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all participants for their invaluable contribution, as well as to all Shehas of the participating wards for their support. They also appreciate the tireless technical support provided by Petra Berger and all members of the Unguja and Pemba survey teams. The authors would like to acknowledge the efforts of the Public Health Laboratory, Pemba, the Zanzibar Health Research Institute, and the Ministry of Health for their essential support, which contributed to the successful completion of this study.

Contributor Information

Salum Seif Salum, Email: salum.salum@suza.ac.tz, mention@uni-bremen.de.

Mohammed Ali Sheikh, Email: m.sheikh@suza.ac.tz.

Antje Hebestreit, Email: hebestr@leibniz-bips.de.

Sørge Kelm, Email: skelm@uni-bremen.de.

References

- Bobrovitz N, Arora RK, Cao C, Boucher E, Liu M, Donnici C, et al. Global seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What COVID-19 seroprevalence surveys can tell us. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/seroprevalance-surveys-tell-us.html, 2020 (visited April 18, 2022)

- Gededzha MP, Mampeule N, Jugwanth S, Zwane N, David A, Burgers WA, et al. Performance of the EUROIMMUN Anti-SARS-CoV-2 ELISA assay for detection of IgA and IgG antibodies in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamady A, Lee J, Loboda ZA. Waning antibody responses in COVID-19: what can we learn from the analysis of other coronaviruses? Infection. 2022;50:11–25. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01664-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis HC, Ware H, Whelan M, Subissi L, Li Z, Ma X, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of standardised seroprevalence studies, from January 2020 to December 2021; medRχiv preprint 2022; doi: 10.1101/2022.02.14.22270934 (visited April 18, 2022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mikofu J. Zanzibar kicks off COVID-19 vaccination, orders another consignment. The Citizen. 2021 https://allafrica.com/stories/202107160932.html July 16. 2021 (accessed April 18, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- Nyangasa MA, Kelm S, Sheikh MA. Hebestreit A. Design, response rates, and population: characteristics of a cross-sectional study in Zanzibar. Tanzania. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(4):e235. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health, COVID-19 Situation Report No 29; https://www.moh.go.tz/storage/app/uploads/public/625/527/243/625527243c3bd391718416.pdf, 2022 (visited April 18, 2022)

- WHO . WHO; 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Herd immunity, lockdowns and COVID-19.https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/herd-immunity-lockdowns-and-covid-19 December 31, 2020 (accessed April 18, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- WHO, Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/tz, 2022 (accessed April 18, 2022)