Abstract

Introduction: Aim of this retrospective cohort study is to evaluate the prognostic value of tumor volume reduction rate status post-induction chemotherapy in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Methods: Patients newly diagnosed from year 2007 to 2016 at a single center were included in this retrospective study. All patients had received induction Taxotere, Platinum, Fluorouracil followed by daily definitive intensity-modulated radiotherapy for 70 Gy in 35 fractions concurrent with or without cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Tumor volume reduction rate was measured and calculated by contrast-enhanced computed tomography images at diagnosis, and after at least 1 cycle of induction chemotherapy, and analyzed though a univariate and multivariate Cox regression model. Results: Ninety patients of the primary cancer sites at hypopharynx (31/90, 34.4%), oropharynx (29/90, 32.2%), oral cavity (19/90, 21.1%), and larynx (11/90, 12.2%) were included in this study, with a median follow-up time interval of 3.9 years. In multivariate Cox regression analysis, the tumor volume reduction rate of the primary tumor (TVRR-T) was also an independently significant prognostic factor for disease-free survival (DFS) (hazard ratio 0.77, 95% confidence interval 0.62-0.97; P-value = .02). Other factors including patient's age at diagnosis, the primary cancer site, and RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors), were not significantly related. At a cutoff value using 50% in Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, the DFS was higher with TVRR-T ≥ 50% group (log-rank test, P = .024), and a trend of improved overall survival. (log-rank test, P = .069). Conclusion: TVRR-T is a probable prognostic factor for DFS. With a cut-off point of 50%, TVRR-T may indicate better DFS.

Keywords: locally advanced, head and neck cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, induction chemotherapy, early response, tumor volume, volume reduction

Introduction

In the past 2 decades, induction chemotherapy (IC) has become a common treatment modality for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (LA-HNSCC). There are at least 4 large phase III randomized trials that investigated the benefits and IC. 1–4 The general conclusion of these trials was that IC may lower distant failure rates in LA-HNSCC without improving overall survival (OS). For laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer, there is an additional benefit with applying IC as a tool for selecting candidates for organ preservation. 5–7 However, for head and neck primary cancer sites other than larynx and hypopharynx, IC did not offer a clear benefit for either the organ preservation rate or survival.

The assessment of tumor response in organ preservation studies varied by using laryngoscope or images with unidimensional (in GORTEC 2001-01, and VALCSG trial) or bidimensional (using WHO in EORTC 24891) measurements. 8–10 Although widely used to describe the regression status of a solid tumor, unidimensional measurement, such as RECIST, was not always a predictive value for the treatment outcome of head and neck cancer patients. 11

On contrary, the extent of tumor volume shrinkage after IC has been established as a prognostic factor for other cancer. In rectal cancer, preoperative tumor volume reduction after chemoradiation therapy predict disease-free survival (DFS). 12 Tumor volume reduction rate (TVRR) during adaptive radiation therapy is regarded as a prognosticator for PFS in nasopharyngeal cancer. 13 In LA-HNSCC, with primary tumor volume being a predictive measurement of local control with chemoradiation, by similar justification, post-IC tumor volume reduction has potential for predicting the outcome, which has not yet been investigated. 14

In this study, we discussed the characteristics and the prognostic value of TVRR status post-IC in LA-HNSCC patients. We also argue that TVRR is a suitable prognostic indicator for following definitive treatment outcome for LA-HNSCC.

Materials and Methods

Patient Cohort and Clinical Data Collection

We retrospectively collected the clinical and imaging data of patients with newly diagnosed LA-HNSCC from year 2007 to 2016 at a single center (China Medical University Hospital) for this cohort study. Patients receiving primary treatment of IC followed by definitive (chemo-)radiotherapy (CRT) were included selectively. The inclusion criteria for the retrospective analysis were as follows: (1) the patient's age was 20 to 75 years old; (2) the newly diagnosed HNSCC with pathological proof; (3) there was no distant metastasis at diagnosis; (4) the patient had no prior history of any other cancer; (5) two contrast-enhanced CT scans were performed at diagnosis and after at least 1 cycle of IC (defined as interim CT); (6) the patient received at least 1 cycle of IC; (7) the patient received at least 1 course of definitive (C)RT.

We collected data including patient's age, gender, TNM classification, primary site of the cancer, smoking status, disease status, pattern of recurrence, time of recurrence and death. We also measured the response of tumor volume by RECIST 1.1 15 on interim CT, verified by 2 board certified hematologist-oncologists. The OS duration was defined as the time interval between the date of diagnosis and the date of death or the last follow-up visit date. The DFS was defined as the time interval between the date of diagnosis and the date of any disease recurrence (including distant metastasis and local recurrence) or the last follow-up visit date.

Treatment Schedule in our Facility

IC followed a dose-dense TPF (ddTPF) protocol 16 with cisplatin 50 mg/m2 and docetaxel 50 mg/m2 on day 1, leucovorin 250 mg/m2 on day 1, followed by 48 h continuous infusion of 2500 mg/m2 of 5-fluorouracil on day 1 and 2, every 2 weeks. Daily definitive IMRT for 68.4 to 72 Gy with 1.8 to 2.0 Gy fraction size was given alone or concurrent with chemotherapy (CCRT) with weekly cisplatin for 35 to 40 mg/m2. Interim CT is usually arranged after 2 cycles of IC.

Delineation of Anatomic Tumor Volume on CT Image

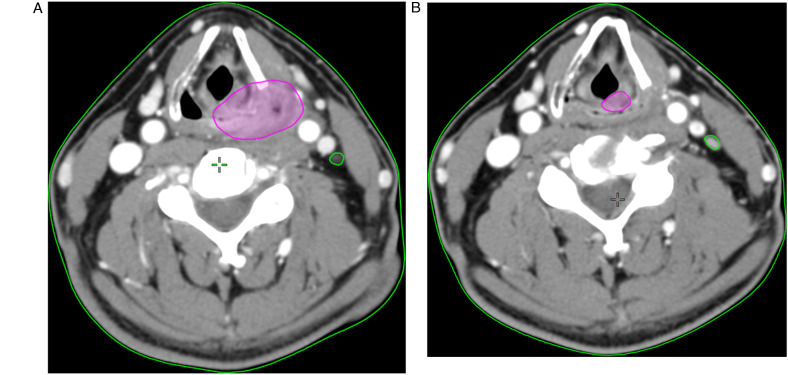

For each patient, the tumor was contoured by a senior resident and verified by a board-certified radiation oncologist, based on the contrast-enhanced CT images both at diagnosis and interim. The volumes of the primary tumor and the involved neck lymph nodes were separately delineated. The gross tumor volume of the primary tumor and the involved nodes before IC were designated as GTV-T1 and GTV-N1 (as shown in Figure 1A). On interim CT, primary tumor and the involved nodes before IC were designated as GTV-T2 and GTV-N2 (Figure 1B). The TVRR of primary tumor (TVRR-T) was calculated as (GTV-T1−GTV-T2)/GTV-T1, whereas nodal volume reduction rate (TVRR-N) = (GTV-N1−GTV-N2)/GTV-N1.

Figure 1.

(A) Delineating gross tumor volume before IC on contrast-enhanced CT images, primary tumor designated as GTV-T1 (purple), and the involved nodes designated as GTV-N1 (green). (B) Delineating gross tumor volume on interim CT, primary tumor designated as GTV-T2 (purple), and the involved nodes designated as GTV-N2 (green).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Python 3.6.4 scipy and lifelines packages. Univariate and multivariate analyses using the Cox regression model were applied to distinguish significant prognostic factors. Survival curves were created under Kaplan–Meier product-limit methods, and comparison was done using the log-rank test. In subgroup analysis for different cancer sites and disease status, we used Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables.

The reporting of this study conforms to STROBE guidelines. 17 Data collection and analysis were approved by the institutional review board of the hospital, approval number (CMUH111-REC1-091), with a waiver of informed consent for retrospective data collection. All patient details were de-identified.

Results

Patient and Treatment Characteristics

A total of 90 patients were included for analysis. The median follow-up time interval was 3.9 years. Of the 90 patients, 87 were stage IV and 3 were stage III (based on the seventh edition of AJCC staging). The primary cancer sites were hypopharynx (31/90, 34.4%), oropharynx (29/90, 32.2%), oral cavity (19/90, 21.1%), and larynx (11/90, 12.2%). Among the 29 oropharyngeal cancer patients, 13/29, 44.8% had available p16 status. Of the 13 patients, only 1 patient (1/13, 7.7%) was p16-positive, and the other 12 patients (12/13, 92.3%) were p16-negative (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics of all 90 Patients Who Received Induction Chemotherapy.

| Patient characteristics | All patients (percentage) |

|---|---|

| N | 90 |

| Age (median, [IQR]) | 53.5 [49.2,61.0] |

| Sex | |

| F | 4 (4.4) |

| M | 86 (95.6) |

| T category | |

| 1 | 2 (2.2) |

| 2 | 20 (22.2) |

| 3 | 17 (18.9) |

| 4A | 25 (27.8) |

| 4B | 26 (28.9) |

| N category | |

| 0 | 11 (12.2) |

| 1 | 1 (1.1) |

| 2A | 1 (1.1) |

| 2B | 36 (40.0) |

| 2C | 36 (40.0) |

| 3 | 5 (5.6) |

| Stage | |

| 3 | 3 (3.3) |

| 4A | 57 (63.3) |

| 4B | 30 (33.3) |

| Primary site | |

| Hypopharynx | 31 (34.4) |

| Larynx | 11 (12.2) |

| Oral cavity | 19 (21.1) |

| Oropharynx | 29 (32.2) |

| Primary site response to IC (RECIST) | |

| Partial Response | 58 (64.4) |

| Complete Response | 18 (20.0) |

| Stable Disease | 13 (14.4) |

| Progressive Disease | 1 (1.1) |

| Follow-up days (median, [IQR]) | 1413.5 [506.2,1951.5] |

| GTVtotal1 (ml) (median, [IQR]) | 50.6 [26.1,98.7] |

| GTV-T1 | 29.8 [14.4,76.5] |

| GTV-N1 | 10.1 [3.1,21.7] |

| GTVtotal2 (ml) (median, [IQR]) | 24.5 [11.5,58.0] |

| GTV-T2 | 17.1 [7.2,40.1] |

| GTV-N2 | 3.9 [1.2,9.2] |

| TVRR-total (%) (median, [IQR]) | 46.1 [29.8,60.1] |

| TVRR-T (%) | 43.6 [24.3,54.3] |

| TVRR-N (%) | 53.3 [31.6,66.3] |

| Disease status to the latest follow-up date | |

| Never disease free | 25 (27.8) |

| No recurrence | 38 (42.2) |

| Recurrence | 27 (30.0) |

| Recurrence pattern | |

| Distant Metastasis | 4 (11.4) # |

| Locoregional Recurrence | 23 (65.7) |

| Second Primary | 8 (22.9) |

| IC duration (days) (median, [IQR]) | 74.0 [57.0,80.8] |

| IC to RT interval (days) (median, [IQR]) | 25.0 [19.3, 32.0] |

| TPF dosage (median, [IQR]) | 3.0 [2.5,3.0] |

| T dose (mg/m2) | 263.5 [212.4,294.5] |

| P dose (mg/m2) | 245.4 [202.9,291.8] |

| F dose (mg/m2) | 13 116.8 [10 322.7,14503.7] |

| Smoking | |

| No | 10 (11.9) |

| Yes | 74 (88.1) |

| p16 | |

| Negative | 12 (92.3) |

| Positive | 1 (7.7) |

| N/A | 77 (86) |

| Complete definitive treatment | 77 (86) |

| RT alone | 58 (64) |

| concurrent with cisplatin | 19 (21) |

| Incomplete definitive treatment | 13 (14) |

| RT alone | 10 (11) |

| concurrent with cisplatin | 3 (4) |

# indicates there was no distal metastasis and locoregional recurrence combine. Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; GTVtotal1, gross tumor volume of both tumor and nodal sites before IC; GTVtotal2, gross tumor volume of both tumor and nodal sites at interim; GTV-T1, gross tumor volume of the primary tumor before IC; GTV-T2, gross tumor volume of the primary tumor at interim; GTV-N1, gross tumor volume of the involved nodes before IC; GTV-N2, post-IC gross tumor volume of the involved nodes at interim; IC, induction chemotherapy; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; RT, radiotherapy; TVRR-total, tumor volume reduction rate of both tumor and nodal sites; TVRR-T, tumor volume reduction rate of the primary tumor; TVRR-N, tumor volume reduction rate of the involved nodes; TPF, docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil.

All patients have received IC: 85 patients (85/90, 94.4%) received ddTPF, and 5 patients (5/90, 5.6%) received alternative IC regimen consisting of carboplatin, methotrexate, and/or cetuximab. Median number of IC cycles is 3 [IQR 2-3]. There are 2 only patients received only 1 cycle of IC. The median time interval between radiation and IC is median 25 days (IQR, 19.3-32.0). All patients started definitive RT course after interim CT.

All patients have received curative intent daily IMRT dose for 68.4 to 72 Gy with 1.8 to 2.0 Gy fraction size: 77 patients (77/90, 85.6%) had complete RT treatment courses, in which 58 (58/77, 75%) patients were RT alone and 19 (19/77, 25%) patients were concurrent with weekly cisplatin; 13 patients (13/90, 14.4%) had incomplete RT treatment courses (total dose below 68.4 Gy, median dose 56 Gy, IQR [38, 60]), in which 10 (10/13, 78%) patients were RT alone and 3 (3/10, 22%) patients were concurrent with weekly cisplatin.

There were 13 patients (n = 13/90, 14%) who had incomplete definitive (C)RT courses, ranging from minimum 12 Gy to maximum 68 Gy, median 56 Gy with interquartile range 38 to 60 Gy, and 8 of them (n = 8/13, 61.5%) failed to reach initial complete remission.

Tumor Volume Response to Induction Chemotherapy

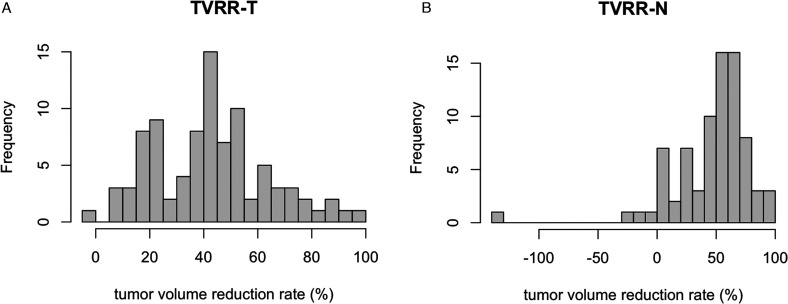

The tumor volume of primary site GTV-T1 (at diagnosis) and GTV-T2 (at interim study) were median 29.8 (14.4-76.5, IQR) ml and 17.1 (7.2-40.1, IQR) ml, and TVRR-T was median 43.6% (24.3%-54.3%, IQR). Respectively, the nodal volume GTV-N1 and GTV-N2 were median 10.1 (3.1-21.7, IQR) ml and median 3.9 (1.2-9.2, IQR) ml. TVRR-N was median 53.3% (31.6%-66.3%, IQR); distribution is shown in Figure 2A and 2B.

Figure 2.

(A) Distribution of TVRR-T. (B) Distribution of TVRR-N.

By RECIST criteria, tumor response comprised of partial response (PR) (58/90, 64.4%), complete response (CR) (18/90, 20.0%), stable disease (13/90, 14.4%), and progressive disease (1/90, 1.1%).

There was only 1 patient who had disease progression in primary tumor site. Four patients had disease progression on lymph node volume despite their primary site volume shrinking, in which 3 of them had nodal volume increasing over 10% and never reached disease free, even with 2 of them had received complete definitive RT.

Different Primary Sites of Cancer Response to IC and Outcome of Definitive Treatment

In 4 types of cancers, TVRR-T showed a similarity across different primary sites, as well as their received dosage of IC, despite that oral cavity cancer had larger primary tumor volume both before and after IC, that is, GTV-T1 85.3 ml (P = .01) and GTV-T2 44.3 ml (P = .03) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics Grouped by Primary Sites.

| Hypopharynx | Larynx | Oral cavity | Oropharynx | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 31 | 11 | 19 | 29 | ||

| T category | ||||||

| 1 | 2 (6.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | .085 | |

| 2 | 7 (22.6) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (10.5) | 7 (24.1) | ||

| 3 | 9 (29.0) | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 7 (24.1) | ||

| 4A | 6 (19.4) | 3 (27.3) | 6 (31.6) | 10 (34.5) | ||

| 4B | 7 (22.6) | 4 (36.4) | 10 (52.6) | 5 (17.2) | ||

| N category | ||||||

| 0 | 3 (9.7) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (10.3) | .578 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.4) | ||

| 2A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.4) | ||

| 2B | 15 (48.4) | 3 (27.3) | 6 (31.6) | 12 (41.4) | ||

| 2C | 11 (35.5) | 3 (27.3) | 10 (52.6) | 12 (41.4) | ||

| 3 | 2 (6.5) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (5.3) | 0 | ||

| Stage | ||||||

| 3 | 1 (3.2) | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (3.4) | .108 | |

| 4A | 21 (67.7) | 6 (54.5) | 7 (36.8) | 23 (79.3) | ||

| 4B | 9 (29.0) | 5 (45.5) | 11 (57.9) | 5 (17.2) | ||

| Follow-up days [IQR] | 1352.0 [590.0,1943.0] | 1606.0 [658.0,2019.5] | 399.0 [336.5,1368.5] | 1698.0 [1083.0,2018.0] | .019* | |

| GTV-T1 ml (median, IQR) | 15.7 [10.9,50.0] | 29.9 [17.1,50.7] | 85.3 [45.4,132.9] | 28.8 [17.9,49.7] | .001* | |

| GTV-N1 (median, IQR) | 8.2 [3.7,16.9] | 12.6 [1.1,37.2] | 11.0 [3.5,22.8] | 11.8 [2.8,21.8] | .953 | |

| GTV-T2 (median, IQR) | 9.1 [5.5,26.4] | 19.8 [8.4,33.4] | 44.3 [21.5,92.8] | 14.2 [8.0,25.7] | .003* | |

| GTV-N2 (median, IQR) | 3.0 [1.6,7.4] | 2.7 [0.4,8.3] | 5.9 [2.1,12.2] | 4.6 [1.2,7.7] | .566 | |

| TVRR-T (%) [IQR] | 41.1 [24.2,56.1] | 41.1 [19.6,50.2] | 44.0 [24.1,53.8] | 44.1 [33.2,53.0] | .812 | |

| TVRR-N (%) [IQR] | 51.8 [27.9,64.0] | 63.5 [53.5,73.3] | 40.6 [7.9,59.0] | 59.8 [45.1,70.5] | .019* | |

| Disease status | ||||||

| Never disease free | 8 (25.8) | 2 (18.2) | 13 (68.4) | 2 (6.9) | <.001* | |

| No recurrence | 16 (51.6) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (21.1) | 13 (44.8) | ||

| Recurrence | 7 (22.6) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (10.5) | 14 (48.3) | ||

* indicates P-value <0.05. Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; TVRR tumor volume reduction rate.

Regarding response to definitive (C)RT, hypopharynx, larynx, and oropharynx have similar CR rate of 51.6%, 45.5%, and 44.8%, respectively, the similar median follow-up days of 1352, 1606, and 1698, and the never free of disease percentage being 25.8%, 18.2%, and 6.9%. In contrary, oral cavity cancer responded significantly worse to definitive (C)RT, with 68.4% never free of disease, and only 21.1% reached complete remission.

Outcome of Definitive Treatment and Characteristic of Recurrence Status

After definitive treatment, 25 (25/90, 27.8%) patients were never disease free, who tended to have higher T (T4b 52%) and overall stage (stage IVB 60%), lower tumor reduction rates (TVRR-T 41.1%, and TVRR-N 43.4%), and shorter median follow-up days (387), compared to other initial complete remission group (recurrence median follow-up days 1133 and no recurrence group 1827). Oral cavity comprised 52% in this group (as shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient Characteristics Grouped by Disease Status.

| Never disease free | No recurrence | Recurrence | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 25 | 38 | 27 | |

| T category | ||||

| 1 | 2 (8.0) | 0 | 0 | <.001* |

| 2 | 0 | 15 (39.5) | 5 (18.5) | |

| 3 | 1 (4.0) | 8 (21.1) | 8 (29.6) | |

| 4A | 9 (36.0) | 7 (18.4) | 9 (33.3) | |

| 4B | 13 (52.0) | 8 (21.1) | 5 (18.5) | |

| N category | ||||

| 0 | 1 (4.0) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (22.2) | .310 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) | |

| 2A | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 0 | |

| 2B | 8 (32.0) | 15 (39.5) | 13 (48.1) | |

| 2C | 14 (56.0) | 16 (42.1) | 6 (22.2) | |

| 3 | 2 (8.0) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (3.7) | |

| Stage | ||||

| 3 | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 2 (7.4) | .013* |

| 4A | 10 (40.0) | 28 (73.7) | 19 (70.4) | |

| 4B | 15 (60.0) | 9 (23.7) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Cancer site | ||||

| Hypopharynx | 8 (32.0) | 16 (42.1) | 7 (25.9) | <.001* |

| Larynx | 2 (8.0) | 5 (13.2) | 4 (14.8) | |

| Oral cavity | 13 (52.0) | 4 (10.5) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Oropharynx | 2 (8.0) | 13 (34.2) | 14 (51.9) | |

| Follow-up days (median, [IQR]) | 387.0 [277.0, 507.0] |

1827.0 [1526.2, 2090.8] |

1133.0 [849.0, 1898.0] | <.001* |

| TVRR-T (%) (median, [IQR]) | 41.1 [19.0, 51.4] |

48.3 [35.2, 61.1] |

36.3 [23.8, 48.3] |

.025* |

| TVRR-N (%) (median, [IQR]) | 43.4 [5.3, 59.7] |

51.8 [31.5, 66.7] |

60.3 [49.6, 70.4] |

.008* |

| TPF cycles (median, [IQR]) | 3.0 [3.0, 3.0] | 3.0 [2.5, 3.0] | 3.0 [2.6, 3.0] | .703 |

| Recur pattern | ||||

| Distal Metastasis | 1 (33.3) | 3 (11.1) | <.001* | |

| Locoregional Recurrence | 1 (33.3) | 22 (81.5) | ||

| Second Primary | 1 (33.3) | 5 (100.0) | 2 (7.4) |

* indicates P-value <0.05. Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; TVRR-T, tumor volume reduction rate of the primary tumor; TVRR-N, tumor volume reduction rate of the involved nodes; TPF, docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil.

Sixty-five (65/90, 72.2%) patients reached initial complete remission. The recurrence pattern in this group was 33.8% (n = 22) with locoregional recurrence, 4.6% (n = 3) with distal metastasis, 7.7% with second primary cancer (n = 5), and 3.1% (n = 2) with both locoregional recurrence and second primary cancer combined. In following DFS analysis, patients with second primary were censored at the date of second primary cancer diagnosis. There was no patient with distal metastases and locoregional recurrence combined.

TVRR-T and RECIST: Univariate and Multivariate Using Cox Regression Model

In univariate Cox regression analysis, the TVRR-T as a continuous variable showed a significant difference for DFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.77, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.63-0.96; P = .02); otherwise, TVRR-N, age, IC dose (docetaxel), cancer sites, RECIST, completion of RT treatment, and concurrence with cisplatin-based chemotherapy as variables were not. In multivariate analysis, TVRR-T was also a significant prognostic factor for DFS (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.62-0.97; P = .02), with covariates of age, IC dosage, oral cavity cancer (or other primary sites) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis of the Associations Between Prognostic Factors and Disease-Free Survival (DFS) Outcomes.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard (95% CI) | P-value | |

| TVRR-T | 0.77 (0.63, 0.96) | .02* | 0.77 (0.62, 0.97) | .02* |

| TVRR-N | 1.17 (0.96, 1.42) | .120 | ||

| RECIST | 1.31 (0.62, 2.76) | .470 | ||

| Age | 0.84 (0.53, 1.38) | .500 | 1.00 (0.57, 1.77) | 1.00 |

| IC dose (Docitaxel) | 1.26 (0.67, 2.40) | .470 | 1.15 (0.55, 2.40) | .70 |

| Cancer sites (Oral cavity vs non-oral cavity) |

0.93 (0.22, 3.92) | .920 | 0.86 (0.18, 4.00) | .840 |

| Complete RT | 1.00 (0.24, 4.22) | .996 | ||

| RT concurrent with cisplatin | 2.13 (0.99, 4.56) | .053 | ||

* indicates P-value <0.05. Abbreviations: TVRR-T, tumor volume reduction rate of primary tumor; TVRR-N, tumor volume reduction rate of lymph node.

Cut-off Point of the TVRR-T for OS and DSF

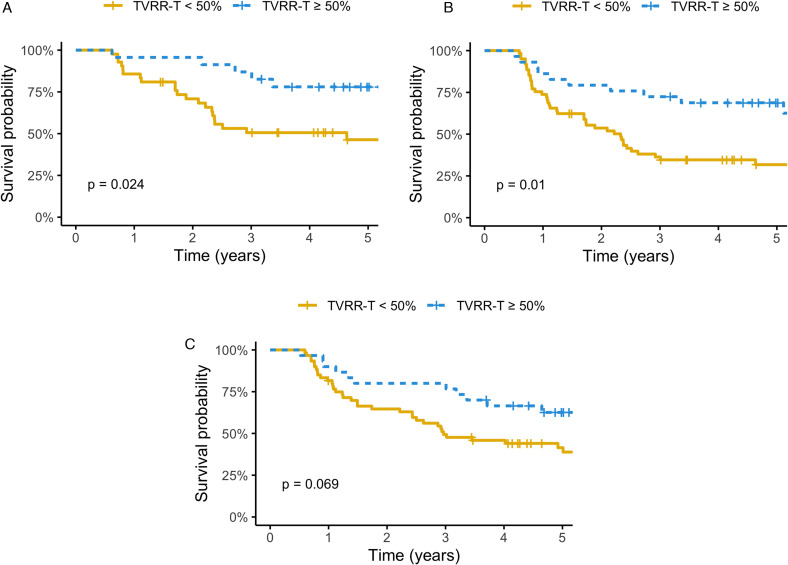

For Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, we used a cutoff value of 50% for the TVRR-T to stratify those who reached initial complete remission (n = 65) into 2 groups: good responder (n = 23) and poor responder (n = 42), the DFS was significant higher with TVRR-T ≥ 50% group (log-rank test, P = .024) (Figure 3A). If all patients were considered, including those who had never been disease free, there was still significant higher DFS (log-rank test, P = .01) for good responder (n = 30), compared to poor responder (n = 60) (Figure 3B). There was also a trend of improved OS in good responder (n = 30), compared to poor responder (n = 60) (log-rank test, P = .069) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

(A) Disease-free survival by a cut-off point of 50% of TVRR-T (only patients with initial complete remission were included [n = 65]). (B) Disease-free survival by a cut-off point of 50% of TVRR-T (all patients were included [n = 90]). (C) Overall survival by a cut-off point of 50% of TVRR-T (all patients were included [n = 90]).

Discussion

With imaging improvement, volumetric method theoretically provided more accurate description for gross tumor. In other cancer sites, such as rectal cancer, the extent of tumor volume shrinkage is an established prognostic factor.18,19 In small cell lung cancer, response volume also correlated to outcome of definitive RT. 20 In locally advanced nasopharyngeal cancer, a study found a cutoff point (12.6%) of TVRR after neoadjuvant chemotherpay to serve as a prognositc value for disease control, including OS. 21

In HNSCC, lower intratreatment SUVmax and lower nodal volume on PET/CT has association with improved outcome. 22 Metabolic tumor volume change under PET/CT after first IC cycle has been suggested as an early prognostic indicator of response for following (chemo)radiation. 23 However, the correlation between IC treatment response and following outcomes remains unclear. To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe volume shrinkage and its relation toward survival in this patient group.

In this study, we found the retrospective data supporting that TVRR-T has correlation to following curative intent (chemo)radiotherapy. In good responders, 77% of patients had reached complete remission, and also reached a significant superior DFS compared to poor responders, while the 1-dimensional RECIST failed to show correlation to disease control.

As for laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer, patients could benefit from IC to spare morbid surgeries and resulted in satisfactory disease control. Literature focusing on response after IC in HNSCC usually sorted patients into good and poor responders by various measurements, including RECIST or WHO. In some prospective studies, TVRR had taken the role to stratify HNSCC patients.24,25 However, there was still no evidence that the response to IC can be used as the indicator of organ preservation. 10

In most larynx preservation prospective trials protocol, for poor responders, defined as stable to progression disease, the patients undergo total laryngectomy for an non-inferior comparison to definitive (C)RT.8–10,25,26 Using our retrospective data, we had collected a curative intent cohort with same protocol after IC for all patients, both good and poor responders alike. Despite locally advanced in general, this cohort resulted in a superior DSF for good responders, reinforcing the rationale that good responders are suitable for organ preservation.

This study also revealed a discordant treatment response between primary tumors and involved lymph nodes in few patients. Some individuals had paradoxical responses to IC, that their primary tumor volume reduced but lymph nodes enlarged. Such finding is coherent with prognostic value that TVRR-T to DFS, while TVRR-N did not. This phenomenon had also been described in some immunotherapy studies, in which tumor shrinkage varied at primary and nodal sites, possibly due to different microenvironment. 27 For poor responders with progression disease, especially in nodal metastases, salvage surgical treatment such as neck lymph node dissection should be considered an option.

We also noticed an overall lower survival in our cohort compared to historical study. In Taiwan, unlike the Western population, patients with non-HPV oropharyngeal cancer still outnumbered the HPV-related counterpart, despite a rising trend in HPV-related group. 28 In our study cohort, up to 92.3% (N = 12) were non-HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer, which may result in the poorer outcome, regarding historical study like RTOG 0129, in which study HPV + and HPV− 3-year locoregional control were 86% and 65%. 29 With majority of patient with smoking (88.1%) and p16-negative (92.3%) risk factors in this cohort, an inferior outcome is understandable.

Other possible cause of inferior disease control in this cohort could be a considerable amount of oral cavity cancer. As a primarily surgical disease, they consisted of 21.1% in our study cohort. These patients reached an overall local control of 21%, 68% never free of disease, and OS of 25%, a much worse treatment outcome compared to PARADIGM trial, in which 18% oral cavity cancer and 45% patients with non-oropharyngeal cancer group yielded 3-year PFS 66% [45-80, 95% CI], and OS 73% [52-85, 95% CI], 3 non-inferior to oropharyngeal cancer.

Despite the suspicion of oral cavity may contribute to inferior outcome, multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed non-significant hazard to DFS, after adjusting age, IC dose, and oral cavity (vs non-oral cavity) cancer as covariates.

In summary, our study showed that TVRR-T after IC is prognostic of DFS in LA-HNSCC patient. As therapeutic and prognostic indicator, combined with future radiomic features, may be a useful reference for clinical judgement. 30 To better justify this treatment response organ preservation paradigm, larger prospective trial is need. Future prospective study design concerning IC could also consider volumetric measurement for treatment response.

Limitation

Limited by its retrospective nature, this study only selects patients who are suitable for IC and resulted in a group of patients with a variety of different outcome and treatment modality. The heterogeneity of this cohort and small sample size undermine the survival analysis, which is underpowered to show meaningful significance.

We choose docetaxel to represent the intensity of IC dosage in multivariate Cox regression analysis, as in TPF regimen, cisplatin and docetaxel was usually given in 1:1 ratio.

In DFS analysis, we excluded patients who failed to reach initial complete remission, although DFS had remained significantly better for good responders even if never disease free were considered. We believe an initial disease free have better representation for the outcome of definitive treatment, while those with residual tumor could have consideration for surgery.

There were considerable number of patients who failed to complete definitive (C)RT courses, 13 patients (n = 13/90, 14%), in which 8 of them (n = 8/13, 61.5%) also failed to reach initial complete remission. After excluding the patients who failed to reach initial complete remission, the completion of RT was still not a significant hazard to DFS in univariate Cox regression analysis.

The dosage of CCRT was not analyzed in this retrospective study, despite there was no significant DFS between patients received RT alone and those received CCRT, due to the majority patients received RT alone and a variety cycle was given, possibly a reflection of patient's performance status. While oncologists usually encourage patient with better performance to receive CCRT, we assumed that IC dose and completion of RT course had sufficed to describe the tolerable intensity of the whole treatment course.

Studies for volumetric measure usually favor MRIs over CT images, for MRIs have better quality to delineate tumor. However, the accessibility and cost make CT a reliable and reasonable clinical tool.

Conclusion

We found that the TVRR of primary tumor (TVRR-T) may correlate to the prognosis of patients with LAHNSCC. In univariate and multivariate analyses, we found that the TVRR-T is a probable prognostic factor for DFS. A cut-off point of 50% for the TVRR-T may indicate better DFS.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CRT

chemoradiotherapy

- DFS

disease-free survival

- GTV

gross tumor volume

- GTV-N1

gross tumor volume of the involved nodes before IC

- GTV-N2

gross tumor volume of the involved nodes at interim

- GTV-T1

gross tumor volume of the primary tumor before IC

- GTV-T2

gross tumor volume of the primary tumor at interim

- HR

hazard ratio

- IC

induction chemotherapy

- LA-HNSCC

locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- RT

radiotherapy

- TPF

docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil

- TVRR

tumor volume reduction rate

- TVRR-N

tumor volume reduction rate of the involved nodes

- TVRR-T

tumor volume reduction rate of the primary tumor.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement for This Work: Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Statement: Data collection and analysis were approved by the institutional review board of China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (CMUH111-REC1-091).

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the China Medical University Hospital (grant number DMR-108-055).

ORCID iD: Chi-Hsien Huang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8948-4827

References

- 1.Ghi MG, Paccagnella A, Ferrari D, et al. Induction TPF followed by concomitant treatment versus concomitant treatment alone in locally advanced head and neck cancer. A phase II-III trial. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2017;28(9):2206‐2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen EEW, Karrison TG, Kocherginsky M, et al. Phase III randomized trial of induction chemotherapy in patients with N2 or N3 locally advanced head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2014;32(25):2735‐2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haddad R, O’Neill A, Rabinowits G, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy (sequential chemoradiotherapy) versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locally advanced head and neck cancer (PARADIGM): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(3):257‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hitt R, Grau JJ, López-Pousa A, et al. A randomized phase III trial comparing induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy alone as treatment of unresectable head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(1):216‐225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posner MR, Norris CM, Wirth LJ, et al. Sequential therapy for the locally advanced larynx and hypopharynx cancer subgroup in TAX 324: survival, surgery, and organ preservation. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(5):921‐927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma J, Liu Y, Yang X, Zhang C ping, Zhang Z yuan, Zhong L ping. Induction chemotherapy in patients with resectable head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, Kirkpatrick A, Collette L, Sahmoud T. Larynx preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: preliminary results of a European organization for research and treatment of cancer phase III trial. EORTC head and neck cancer cooperative group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(13):890‐899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf GT, Fisher SG, Hong WK, et al. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(24):1685‐1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lefebvre J-L, Andry G, Chevalier D, et al. Laryngeal preservation with induction chemotherapy for hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: 10-year results of EORTC trial 24891. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2012;23(10):2708‐2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janoray G, Pointreau Y, Garaud P, et al. Long-term results of a multicenter randomized phase III trial of induction chemotherapy with cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, ± docetaxel for larynx preservation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(4):djv368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe NM, Kershaw LE, Bernstein JM, et al. Pre-treatment tumour perfusion parameters and initial RECIST response do not predict long-term survival outcomes for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with induction chemotherapy. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0194841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han YB, Oh SN, Choi, et al. Clinical impact of tumor volume reduction in rectal cancer following preoperative chemoradiation. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016;97(9):843‐850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee H, Ahn YC, Oh D, Nam H, Noh JM, Park SY. Tumor volume reduction rate during adaptive radiation therapy as a prognosticator for nasopharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;48(2):537‐545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knegjens JL, Hauptmann M, Pameijer FA, et al. Tumor volume as prognostic factor in chemoradiation for advanced head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2011;33(3):375‐382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 2009;45(2):228‐247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh C-Y, Lein MY, Yang SN, et al. Dose-dense TPF induction chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer: a phase II study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573‐577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiraishi T, Sasaki T, Ikeda K, Tsukada Y, Nishizawa Y, Ito M. Predicting prognosis according to preoperative chemotherapy response in patients with locally advanced lower rectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeo S-G, Kim DY, Park JW, et al. Tumor volume reduction rate after preoperative chemoradiotherapy as a prognostic factor in locally advanced rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2012;82(2):e193‐e199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halvorsen TO, Herje M, Levin N, et al. Tumour size reduction after the first chemotherapy-course and outcomes of chemoradiotherapy in limited disease small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2016;102:9‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang H, Liu Y, Zhang R, et al. Prognostic value of the tumor volume reduction rate after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locoregional advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2020;110:104897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mowery YM, Vergalasova I, Yoo DS, Das SK, Hara W, Brizel DM. Correlating clinical outcomes with changes in tumor volume and 18F-FDG PET characteristics during radiation therapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Int J Radiat Oncol • Biol • Phys. 2016;94(4):920. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong KH, Welsh L, Mcquaid D, et al. Metabolic tumor volume changes measured by 18F-FDG-PET/CT after 1 cycle of induction chemotherapy is an early predictor of radical chemoradiation therapy outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2016;94(4):920‐921. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seiwert TY, Foster CC, Blair EA, et al. OPTIMA: a phase II dose and volume de-escalation trial for human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2019;30(10):1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefebvre JL, Pointreau Y, Rolland F, et al. Induction chemotherapy followed by either chemoradiotherapy or bioradiotherapy for larynx preservation: the TREMPLIN randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31(7):853‐859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Semrau S, Schmidt D, Lell M, et al. Results of chemoselection with short induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation or surgery in the treatment of functionally inoperable carcinomas of the pharynx and larynx. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(5):454‐460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merlino DJ, Johnson JM, Tuluc M, et al. Discordant responses between primary head and neck tumors and nodal metastases treated with neoadjuvant nivolumab: correlation of radiographic and pathologic treatment effect. Front Oncol. 2020;10:566315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang T-Z, Hsiao J-R, Tsai C-R, Chang JS. Incidence trends of human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer in Taiwan, 1995-2009: human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(2):395‐408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen-Tan PF, Zhang Q, Ang KK, et al. Randomized phase III trial to test accelerated versus standard fractionation in combination with concurrent cisplatin for head and neck carcinomas in the radiation therapy oncology group 0129 trial: long-term report of efficacy and toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3858‐3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal JP, Sinha S, Goda JS, et al. Tumor radiomic features complement clinico-radiological factors in predicting long-term local control and laryngectomy free survival in locally advanced laryngo-pharyngeal cancers. Br J Radiol. 2020;93(1109):20190857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]