Abstract

Background

With the domestication of ornamental plants, artificial selective pressure favored the propagation of mutations affecting flower shape, and double-flower varieties are now readily available for many species. In peach two distinct loci control the double-flower phenotype: the dominant Di2 locus, regulated by the deletion of the binding site for miR172 in the euAP2 PETALOSA gene Prupe.6G242400, and the recessive di locus, of which the underlying factor is still unknown.

Results

Based on its genomic location a candidate gene approach was used to identify genetic variants in a diverse panel of ornamental peach accessions and uncovered three independent mutations in Prupe.2G237700, the gene encoding the transcript for microRNA miR172d: a ~5.0 Kb LTR transposable element and a ~1.2 Kb insertion both positioned upstream of the sequence encoding the pre-miR172d within the transcribed region of Prupe.2G237700, and a ~9.5 Kb deletion encompassing the whole gene sequence. qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that expression of pre-miR172d was abolished in di/di genotypes homozygous for the three variants.

Conclusions

Collectively, PETALOSA and the mutations in micro-RNA miR172d identified in this work provide a comprehensive collection of the genetic determinants at the base of the double-flower trait in the peach germplasms.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-022-03691-w.

Keywords: Prunus persica L. Batsch, Ornamental traits, Petal number, miRNA, miR172

Background

Peach (Prunus persica L.) is a deciduous tree species belonging to the Rosaceae family widely grown in temperate regions of both the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It originates from China, where the domestication process could have started as early as 7,500 years ago [1]. Between 3000 and 2000 years ago the cultivation of this crop spread through the Asian continent, to the Middle East and Europe, and was more recently brought to the Americas by Spanish and Portuguese explorers [2]. Since a long time, peach is appreciated as an arboreal ornamental plant for the flamboyance of its springtime blooms, particularly sought-after in Eastern countries such as Japan and China, where it is a symbol of luck and happiness. Ornamental peaches are characterized by a huge variability for traits related to tree growth habit, flower and leaf colors, flower shape and type. Growth habits vary from upright to dwarf, weeping, and fastigiate [3]. Flower color is usually pink but in different cultivars it ranges from white to magenta or red, occasionally displaying bicolor or tricolor stripes in ‘variegated’ varieties. While the cultivated peach typically bears flowers with five sepals, five petals, many stamens and one pistil, ‘Flore pleno’ or ‘Double flower’ varieties are instead characterized by extra flower organs, particularly petals (from 10 – 25 in ‘semi-double’ to more than 30 – 40 in double cultivars) [4]. The degree of doubleness and differences in petal shapes concurrently result in different flower types, recognized as ‘Mei-flower’ (rounded), ‘Rose’ (cup-shaped), ‘Peony’ (petaloid stamens) and ‘Chrysanthemum’ (non-showy narrow petals) types [3]. Like for other core eudicots, the flower meristem gives rise to four concentric whorls that differentiate, from the outside to the inside, into sepals and petals, the two whorls that define the outer perianth, and into stamens and a pistil, the reproductive organs. To explain the floral patterning, the so-called ABCDE model was devised using knowledge built from homoeotic mutants in model species [5–8] and has helped research in the topic for three decades now. The model divides different transcription factors into classes (A, B, C, D, E) based on their function, and the combination of different classes defines the ontogeny of each floral whorl. D-function genes are responsible for ovule identity [9], and the E-class genes act throughout the floral meristem, while A-, B- and C-class genes exert their action in adjacent whorls. A- and E- gene activity determines the formation of sepals in the first whorl, while the overlapping of their action with that of B-class genes leads to the formation of petals in whorl two. In whorl three the presence of B-, C- and E- functions is responsible of the differentiation of stamens, while the exclusive presence of C- and E-gene activity allows for carpel differentiation in the central whorl. In addition to their organ specification activity, the A-class and C-class genes were also found to mutually repress each other and play a cadastral role in maintaining each other’s activity in the whorl they contribute to shape. Nearly all these floral homoeotic genes encode MADS-domain transcription factors, with the C-function represented by AGAMOUS (AG) in Arabidopsis thaliana [5]. The A-class genes are instead members of the euAP2 family, transcription factors characterized by two AP2 DNA-binding and EAR-repressor domains, and containing a binding site for miR172 [10–12]. In Arabidopsis the promoter of the euAP2 gene APETALA2 (AP2) gene is active in all whorls [13], but accumulation of the resulting protein in whorl three and four is modulated by the complementary expression of miR172. Spatial and temporal patterns of expression appear to be crucial in fine-tuning organ identity, also beyond the ABCDE model: for example a partial overlap of AP2 and miR172 at whorl three during early flower development, causing a transient co-existence of AP2 and AG activities, was proposed to be crucial for stamen development [14]. Alteration at the miR172-binding site of AP2 genes resulted in phenotypes like over-proliferation of third-whorl organs, conversion of stamens to petals and even loss of floral determinacy, depending on the promoter used [13–15].

The first study about peach flower doubleness (hereafter double-flower trait, DF) traces back to Lammerts (1945) in the early 40s and was based on analysis of some F2 progenies from the DF cultivars ‘Early Double Pink’ and ‘Early Double Red’, bearing 12-15 and 18-24 supernumerary petals, respectively. Based on the segregation pattern, petal number was tentatively explained by the presence of three genetic factors: d1, completely recessive, dm1 and dm2 incompletely recessive. Trees homozygous for d1d1 have only 1 to 5 extra petals, d1d1 dm1dm1 10 to 16 extra-petals (as in 'Early Double Pink') while d1d1 dm1dm1 dm2dm2 15 to 24 extra-petals (as in 'Early Double Red' and 'Peppermint Stick'). The presence of a recessive inherited DF trait has been later confirmed in other materials, such as progenies issued from 'Pillar' accession (also known as NJ Pillar) and ‘Helen Borchers' [16]. The di locus was strictly associated to the fastigiated habitus (i.e. columnar growth habit) controlled by the Br/br locus in a genetic map built from an F2 ‘NC174RL’ x ‘Pillar’ progeny [17, 18] and was later assigned to linkage group 2 [19]. More recently, genome-wide association studies detected signal peaks on chromosome 2 at around 21,5 and 24,7 Mb (based on the peach V2.0 reference genome) [20, 21], not far from the candidate gene for Br habitus (i.e. TILLER ANGLE CONTROL 1, Prupe.2G194000.1), found at position 23.2 Mb [22]. Nevertheless, the genetic determinant of the di locus has not yet been identified. Another locus conferring DF trait harbors a single dominant gene (Di2/di2, double flower/single flower), first described by Beckman et al. [23] and also further confirmed in genome-wide association studies [20, 21]. The Di2 locus has been fine-mapped on the distal end of chromosome 6 in two F2 progenies from ‘NJ Weeping’ (an accession derived from ‘Red Weeping’, or probably the same genotype) x ‘Bounty’ and ‘Weeping Flower Peach’ x ‘Pamirskij 5’ crosses, where a strong candidate causal mutation was proposed in the A-function TOE-type gene Prupe.6G242400 [24], encoding a member of the euAP2 family of transcription factors. The mutation consisted in the deletion of the three-prime end of coding sequence, predicted to result in a shorter transcript deprived of the miR172 recognition sequence. The putative transcription factor resulting from the mutated allele was proposed to retain all the known key domains required for its function, but escape the spatial/temporal repression normally granted by miR172. The phenotype was consistent with an increase of meristem size and increased number of floral organs, possibly as consequence of an antagonizing role of this euAP2 on AG-like factors activity in the center of the meristem and impairment of their negative regulation on WUSCHEL [13, 25, 26]. Similar mutations in genes belonging to a family of orthologues to Prupe.6G242400, collectively identified as PETALOSA (PET), were found to consistently lead to dominant double-flower phenotypes in a variety of eudicots (rose species, carnation and petunia) [27]. Furthermore, CrispR-CAS9 induced mutations directed to the miR172 recognition sequence of a PET gene where also shown to lead to double flowers in tobacco [27].

Building on the knowledge of the genomic location of locus di, the molecular determinants of the recessive inherited double-flower trait were investigated through a candidate gene approach in a panel of ornamental peach accessions from different worldwide collections. Three distinct mutations at the microRNA miR172d-encoding transcript Prupe.2G237700 (named di1, di2 and diΔ) resulting in pre-miR172d miss-expression were identified as likely causes of the double-flower phenotype. Sequencing-based genotyping of ornamental accessions in available germplasm collections from Eastern countries revealed the presence of di1 and di2 allelic variants and the absence of diΔ, probably originated as an independent mutation after the peach cultivation spread in Europe.

Results

The di locus maps with a gene transcribing a miR172 precursor sequence

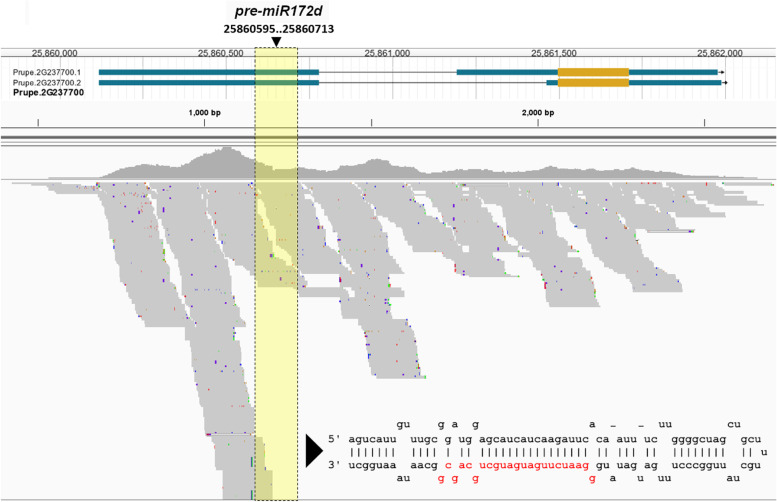

In the attempt to more precisely delimit the di locus position on chr 2, linkage disequilibrium (LD) pattern around the 23 – 26.5 Mb genomic interval enclosing the two associated GWAS signals was inspected in 21 Oriental DF accessions, using about 4K SNPs extracted from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data [21]. The LD map showed a complex pattern characterized by spaced and relatively short regions with long-range high LD levels, defining an interval of about 2.4 Mb, approximately comprised between SNP1456516 (24,277,038) and SNP1501405 (26,628,544) (Supplementary Figure S1). At least 381 gene models were annotated in this interval, based on a peach reference transcripts v2.1 annotations (Supplementary Table S1). Homology-based searches of genes putatively involved in flower tissues differentiation, growth and/or development allowed the identification of a predicted gene (Prupe.2G237700), transcribing a microRNA precursor sequence belonging to the miR172 family, previously classified as ppe-miR172e [28] and hereafter named ppe-miR172d (as currently annotated on www.mirbase.org, accession: MI0026098). Indeed, an increasing body of knowledge around the role of the euAP2/TOE-miR172 module in the regulation of petaloidy in various species [27] makes Prupe.2G237700 a prime candidate for the recessive DF trait. Firstly, the sequence of the miR172d primary transcript was annotated by mapping RNA-seq reads from peach dormant buds of various stages and carpel tissues. The expressed pri-miR172d sequence has no introns, spanning ~2.0 Kb from 25,860,117 to 25,861,987 bp, with the predicted pre-miR172d precursor sequence (119 nt) starting at 25,860,595 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Genomic structure of the micro-RNA miR172d encoding transcript Prupe.2G237700. The pri-miRNA sequence was identified by mapping transcriptome data from various peach flower tissues (petal, stamen, carpel). The predicted pre-miR172d stem-loop hairpin structure is also shown

Three independent mutant alleles of Prupe.2G237700 are associated with the recessive double-flower trait

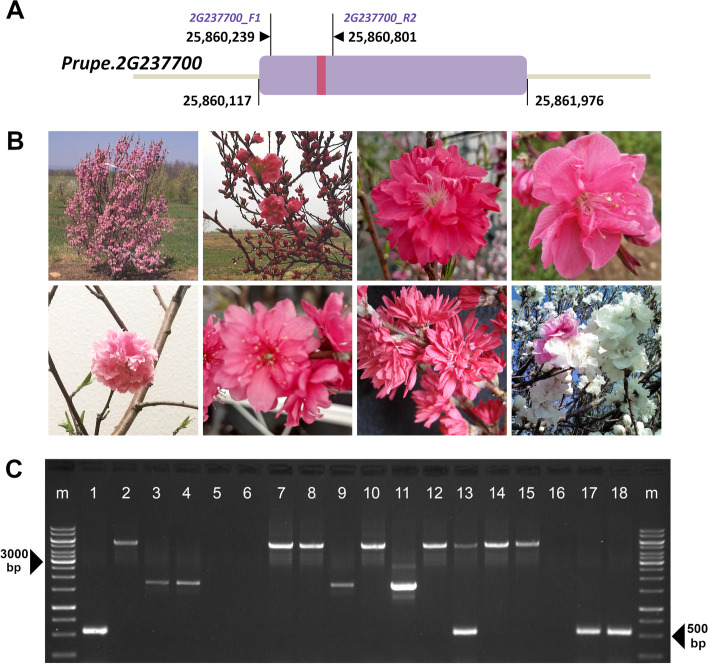

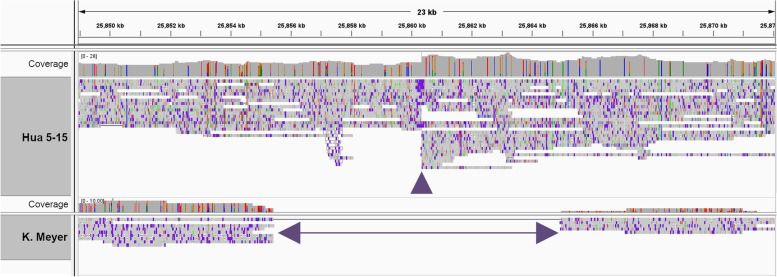

Several primer pairs covering the entire pri-miR172d sequence plus ~1 Kb upstream and downstream were designed to analyze allelic polymorphisms in various ornamental materials, including main commercial cultivars, and accessions or selections retrieved from reliable germplasm collections of INRAE-GAFL (France), University of Milan (Italy), USDA-ARS (Kearneysville, West Virginia, and Byron, Georgia) and Clemson University (South Carolina) (the accession list is provided in Table 1). In agreement with the recessive inheritance of the di trait, causal variant(s) were assumed to be homozygous in DF genotypes. Interestingly, primers 2G237700_F1 and 2G237700_R2 resulted the most informative, as PCR showed a diverse pattern of amplifications in the various accessions (Fig. 2): in single-flower (SF) accession ‘Crimson Rocket’ the wild-type (Di) amplicon of 563 bp (SF ‘Lovell’ peach genome) was observed, as well as in two DF selections ‘KV045590’ and ‘KV021779’; another SF accession, ‘Redleaf Pillar’, showed the 563 bp amplicon alongside a second PCR product of about 5.5 Kb. This PCR product, about 5.0 Kb longer than the wild-type (Di) allele, was exclusively obtained in DF accessions ‘Hokimomo op’, KV872615, ‘Compact Pillar’, ‘Peppermint Stick’, S10321 ‘Hua 5-15’, S10322 ‘Hua 5-25’ and ‘Okinawa’. Interestingly, the other four DF accessions (S7258 ‘clone IRAN 6:59’, ‘Kikoumomo D’, ‘G. Biffi fiore doppio’ and ‘Helen Borchers’) showed an amplicon of ~1.7 Kb (suggestive of an insertion of ~1.2 Kb compared to the Di allele). Finally, three additional DF accessions showed no amplification (among them ‘Klara Meyer’). Sanger sequencing of the 1.7 Kb amplicon revealed a 1,198 bp insertion without LTR elements (named di2 located at position +297 (Pp02:25,860,414) from the pri-miR172d transcription initiation site (Supplementary File S1). BLAST searching showed no clear similarity with known genes or transposable elements, although identical sequences are spread across several peach chromosomes. Instead, a long-read Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) approach was used to sequence the miR172d allelic variants in ‘Klara Meyer’ and ‘S10321 Hua 5-15’, as representative of the genotypes respectively yielding no amplification and the 5.5 Kb amplicons with 2G237700_F1 and 2G237700_R2. Whole-genome coverage was ~10 and ~20x, respectively for ‘Klara Meyer’ and ‘Hua 5-15’, with estimate read length N50 of 32.5 and 21.2 Kb. After aligning to the Peach V2.0 reference genome, two different allelic variants were discovered at the miR172d locus: a ~9.5 Kb deletion (Pp02:25,855,441 to Pp02:25,864,957) encompassing the whole miR172 miRNA precursor sequence including its flanking DNA regions, named diΔ; a ~5.0 Kb LTR insertion (hereafter di1), located at position +221 (Pp02:25,860,344) from the pri-miR172d transcription initiation site (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

List of peach ornamental accessions and selections analyzed in this study. Information about the genotype at di and Di2 loci, as well as source of material, origin and basic description of flower phenotypes are also provided. Asterisks indicate the presence of PET mutation at Di2 locus

| # | Accession | Origin and description | Source | Flower type | Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Crimson Rocket | complex cross from NJ Pillar and Italian Pillar | USDA-ARS (Kearneysville, West Virginia) | Single | Di/Di |

| 2 | Hokimomo op | Japan, variegated white and pink flowers | USDA-ARS (Kearneysville, West Virginia) | Double | di1/di1 |

| 3 | S7258 cl. IRAN 6:59 | Iran | INRAE-GAFL (Avignon, France) | Double | di2/di2 |

| 4 | 'G. Biffi' Fiore Doppio | unknown, Italy | University of Milan (Milan, Italy) | Double | di2/di2 |

| 5 | Taoflora pink | Vietnam – breeding | Nursery | Double | diΔ/diΔ |

| 6 | Taoflora white | Vietnam – breeding | Nursery | Double | diΔ/diΔ |

| 7 | KV872615 | from New Jersey Pillar, pink flowers | USDA-ARS (Kearneysville, West Virginia) | Double | di1/di1 |

| 8 | Compact Pillar | from New Jersey Pillar, red flowers | USDA-ARS (Kearneysville, West Virginia) | Double | di1/di1 |

| 9 | Helen Borchers | unknown, USA | USDA-ARS (Byron, Georgia) | Double | di2/di2 |

| 10 | Peppermint Stick cl. | unknown, USA | Clemson University (Clemson, South Carolina) | Double | di1/di1 |

| 11 | Kikoumomo D (KV044770) | op from Kikoumomo (Japan), chrysanthemum red flowers | USDA-ARS (Kearneysville, West Virginia) | Double | di2/di2 |

| 12 | S10321 Hua 5-15 | China | INRAE-GAFL (Avignon, France) | Double | di1/di1 |

| 13 | Redleaf Pillar | NJ Pillar (germplasm) x Italian Pillar (germplasm) | USDA-ARS (Kearneysville, West Virginia) | Single | Di/di1 |

| 14 | S10322 Hua 5-25 | China | INRAE-GAFL (Avignon, France) | Double | di1/di1 |

| 15 | Okinawa | Japan | University of Milan (Milan, Italy) | Double | di1/di1 |

| 16 | Klara Meyer | Germany, red flowers, semi-dwarf | Kaneppele nursery (Italy) | Double | diΔ/diΔ |

| 17 | KV045590 | F2 from Italian Pillar, white flowers, weeping | USDA-ARS (Kearneysville, West Virginia) | Double | Di/Di* |

| 18 | KV021779 | From Italian Pillar, rose flowers | USDA-ARS (Kearneysville, West Virginia) | Double | Di/Di* |

Fig. 2.

Molecular analysis of sequence variants of the miR172d gene. A Genomic structure of Prupe.2G237700 (purple box) and position of pre-miR172d encoding sequence (red segment). Arrowheads indicate the positions of the primers used for PCR analysis. B Phenotype of double-flower accessions used in this study. Left to right, Top: ‘KV872615’, ‘Compact Pillar’, ‘S7258 cl. IRAN 6:59’, ‘S10321 Hua 5-15’; Bottom: ‘Klara Meyer’, ‘S10322 Hua 5-25’, ‘Kikoumomo D (KV044770)’, ‘Hokimomo op’ (trees and flowers photos were provided by C. Dardick and V. Signoret). C PCR analysis of the single and double-flower accessions listed in Table 1

Fig. 3.

ONT long-sequencing reads alignment at di locus in ‘S10321 Hua 5-15’ and ‘Klara Meyer’ accessions. At the top: reads breakpoint due to a ~5.0 Kb LTR insertion (di1) located at position +221 (Pp02:25,860,338) from the pri-miR172d transcription initiation site. At the bottom: a ~9.5 Kb deletion (diΔ) from (Pp02:25,855,441 to 25,864,957), encompassing the entire pri-miR172 precursor sequence including its flanking DNA regions in ‘Klara Meyer’

The di1 insertion showed homology with a putative FRS5-LIKE gene of the FARS (FAR-RED IMPAIRED RESPONSE1 RELATED SEQUENCE) transcription factors family derived from Mutator-like element (MULE) transposases [29]. Validation of the three allelic variants of the di locus was performed through PCR analyses. Specific primer combinations confirmed the presence of the homozygous di1 insertion found in ‘Hua 5-15’ also in other six DF accessions: ‘Houki Momo op’, ‘KV872615’, ‘Compact Pillar’, ‘Peppermint Stick cl.’, ‘Hua 5-25’ and ‘Okinawa’ (Supplementary Figure S2); consistent with the recessive inheritance of the di trait, the di1 allele was amplified in the heterozygous SF accession ‘Redleaf Pillar’. Finally, the two remaining DF selections ‘KV045590’ and ‘KV021779’ showing the wild-type Di/Di genotype (i.e. 563 bp amplicon) both resulted heterozygous (Di2/di2) for the PETALOSA variant (underlying the dominant inherited Di2 allele) [24] (Table 1). In addition to the panel of ornamental cultivars, the absence (in homozygosis) of any of the three identified di variant(s) in single-flower accessions was further confirmed in a genetically diversified panel of 151 accessions from the PeachRefPop collection [30] (data not shown).

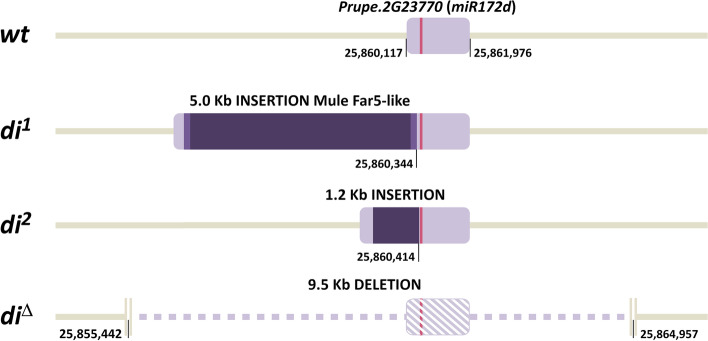

Thus, at least three distinct mechanisms acting on the miR172d gene underpin the recessive double flower trait in peach: di1 (a ~5.0 Kb insertion), di2 (a ~1.2 Kb insertion) and diΔ (a ~9.5 Kb deletion) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Structural variants identified at the gene encoding micro-RNA miR172d, Prupe.2G237700. The wt genomic structure of Prupe.2G237700 is represented by a light lilac box and the red segment indicates the position of the pre-miR172d encoding sequence. Insertions in alleles di1 and di2 are represented by a dark purple box, with LTR regions marked in lighter purple in di1. The genomic region deleted in diΔ is indicated by the dotted/shaded region

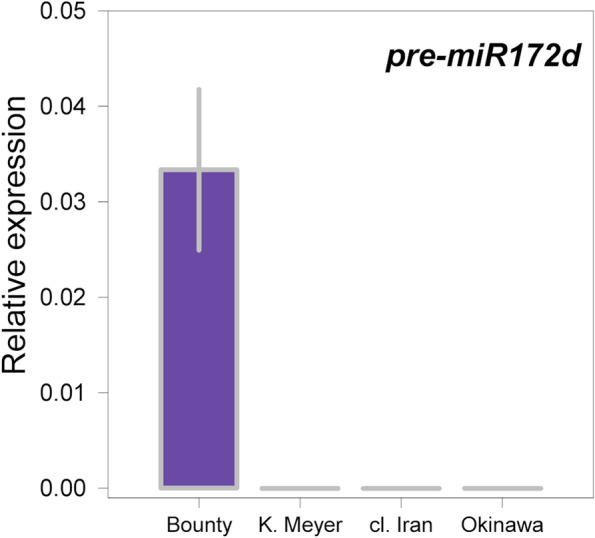

Pre-miR172d expression is abolished in homozygous di1, di2 and diΔ genotypes

The expression profile of pre-miR172d was investigated using qRT-PCR in pooled bud flower tissues from two developmental stages and three di variants: ‘Okinawa’ (di1/di1), ‘clone IRAN 6:59’ (di2/di2) and ‘Klara Meyer’ (diΔ/diΔ). The pre-miR172d was only expressed in the SF control accession ‘Bounty’ (Di/Di), being undetectable in all the three DF accessions (Fig. 5). These findings were clearly consistent with the complete deletion of miR172d sequence in the diΔ allele; in case of di1 and di2 alleles, transposon-induced gene silencing mechanisms could be the most probable explanation, although the exact mechanism(s) leading to their miss-expression should be more specifically addressed.

Fig. 5.

Expression pattern of pre-miR172d in pooled flower bud tissues from Baggiolini stage B (flower bud swelling) to C1 (flower buds apparent) from ‘Bounty’ (single-flower), ‘Klara Meyer’ (double-flower, diΔ), ‘S7258 cl. IRAN 6:59’ (double-flower, di2) and ‘Okinawa’ (double-flower, di1) genotypes. Actin (Prupe.6G163400) was used as a reference to normalize expression data

Distribution of allelic variants in DF varieties of germplasm collections

The availability of phenotypic and genotypic information on peach ornamental accessions across important Chinese collections, allowed exploring the allelic assortment at both di and Di2 loci. The presence of allelic variants (and co-segregation with flower phenotype) was assessed through a sequencing-based method (Supplementary Figure S3 and Materials and Methods section) using public WGS data (retrieved from NCBI SRA database) of 41 peach accessions with clear flower trait (double or semi-double) and sufficient genome coverage (i.e. > 10x), and several SF accessions as control. Among the DF accessions, 21 were homozygous di1/di1 (including the dwarf DF ‘Bonanza peach’, probably erroneously indicated as SF), 7 homozygous di2/di2 and ‘Ju Hua Tao’ carried the di1/di2 allelic combination (Supplementary Table S2); in this last case, the concomitant presence of di1 and di2 alleles suggests that both mutations are functionally equivalent; surprisingly, the diΔ variant seems to be absent in Chinese germplasm collections, suggesting the hypothesis that this allele originated after the arrival of peach in Europe (tracing back to the Greek-Roman era). Apart from the di locus, 7 DF accessions resulted heterozygous for the PET-Di2 variant (Supplementary Table S2). Interestingly the DF accession ‘Hua Yu Lu’ was homozygous for Di and di2 alleles but showing a heterozygous SNP within the core miR172 recognition sequence at the three-prime end portion of the coding sequence of the PET gene (Supplementary Figure S4).

Discussion

The pivotal role of euAP2/miR172 regulatory module is a key component of the floral C-function [7]. In flowers expressing a miR172-resistant version of AP2/TOE or with reduced miR172 activity, the stamens were partially (or completely) converted into petals [14, 27]. In tomato, miR172c and miR172d seem the most abundant forms in developing flowers [31], as also observed in peach [28]. CRISPR-Cas9-editing of tomato miR172c and miR172d showed that hypomorphic and loss-of-function alleles of mir172d were associated with the conversion of petals and stamens to sepaloids, suggesting a dose-dependent regulation of floral organ identity and number [31]. A very recent association study on 417 peach accessions from the Peach Germplasm Repository of Shandong (Agricultural University, China) also suggests the presence of two independent insertion events (named Hap2 and Hap3) within the promoter of Prupe.2G237700 [32] in DF accessions. Sequence alignment and insertion position both confirm the identity of Hap2 with the di2 allele. Also, the high degree of similarity (97.6%) suggests a correspondence of the Hap3 insertion with the di1 allele, despite a 500 bp longer sequence (5.5 vs 5.0 Kb, respectively). The different insertion size between the two alleles may arise from the assembly methods used for obtaining the consensus sequence (i.e. ONT long reads for di1 , Illumina short-reads for Hap3). A length of 4,992bp for the di1 insertion seems to be consistent with the amplicon sizes obtained by PCR (Fig. 2). Moreover, homology searches resulted in no exact matches in the Peach reference genome, in contrast to Hap3, showing 100% identity with an LTR sequence on chr 4 (18,058,479 - 18,063,978). Furthermore, as demonstrated by the annotation of miR172d primary transcript, both insertions fall within the expressed pri-miR172d sequence and not in its promoter region (Figs. 1 and 4), and their presence appears to abolish its expression as much as the putatively null diΔ allele (Fig 5).

Apart from the molecular aspects, the di1, di2 and diΔ allelic variants identified in the present work add valuable information on the genetics of ornamental cultivars, also allowing an evaluation of the breeding history of the varieties used in this study. ‘Houki Momo’ is a seed-propagated ancient ornamental peach from the Edo Era (1700 – 1900) in Japan, characterized by a fastigiated habitus and white-pink double flowers [33]. ‘Houki Momo’ was either the parent or possibly just renamed 'NJ Pillar' (C. Dardick, personal communication). 'Houki Momo‘ and ‘NJ Pillar’ were also the donor of DF trait of several commercial ornamental cultivars, such as the 'Terute’ (and ‘Terute momo’ and ‘Teruteshiro’, from F2 crosses with ‘Akashidare’ and ‘Zhu Fen Chui Zhi’) and the ‘Corinthian’ series of DF cultivars [34, 35], as well as some selections of USDA-ARS (such as ‘Compact Pillar’). Noteworthy, 'NJ Pillar' was one of the cross-parent of the segregating progeny used for the early mapping of di locus [17]. Moreover, 'NJ Pillar' and ‘Italian Pillar’ were also the source of fastigiated and upright growth habits in peach breeding [36], although the latter has single flowers. ‘Peppermint Stick’ (also known as ‘Candy stick’ or ‘Variegated’) has white (or pink) flowers with red stripes and was probably selected from ‘Versicolor’ cultivars around the mid-XIX century, although introduced to the US market only in 1939 by Clarke Nursery (San Jose, California) [37] and still commercially available. The recessive inheritance of DF trait in progenies issued from this cultivar was early reported by Lammerts (1945). ‘Okinawa’ is a low-chill rootstock characterized by white and semi-double flowers, originated from a seed lot imported by the Florida Agricultural Experiment station from the Ryukyu Islands in 1953 [38]. PCR also validated the homozygous diΔ deletion in ‘Klara Meyer’ and the two DF accessions yielding no amplicons with di_miR172F/di_miR172R: ‘Taoflora Pink’ and ‘Taoflora White’ (Supplementary Figure S2). 'Klara Meyer' is an old ornamental peach dating back to 1860 from France [39] (probably named in honor of the homonymous German actress) and bearing dark pink flowers with 80 - 90 petals [40]; this cultivar was introduced in the United States at the end of XIX century (1891) by Spath nursery. By contrast, the ‘Taoflora’ series was relatively recent, released in 2007 by the breeder N’Guyen Dinh Mao (Vietnam), although the breeding source of diΔ is unknown. Regarding the di2 variant, its breeding origin has been more elusive. Of the three di2 genotypes, the USDA-ARS selection ‘Kikumomo D’ (‘KV044770’) was obtained from an open-pollination of the Japanese ‘Kikumomo’ (probably also known as ‘Ju Tao’) showing the same chrysanthemum-type (non-showy) flowers. Progenies from ‘Kikumomo’ showed a recessive inheritance of DF trait [41]. 'Helen Borchers' was one of the oldest US commercial ornamental peaches released before 1939 by Clarke Nursery [16], bearing pink flowers with 30 – 40 petals, 10 sepals and multiple pistils [40]. Segregation of flower doubleness in F2 progenies from a F1 seedling derived from ‘Helen Borchers’ further confirmed the recessive inheritance of its di2 allele [16]. Our analysis clearly shows that the flower doubleness of ‘Helen Borchers’ is not ascribable to a diΔ allele derived from ‘Klara Meyer’, that was previously deemed as its parent [37].

Apart from the peach ornamental accessions available in European and US collections, wider germplasm pools are maintained in Far-East countries, which boast a centennial tradition in the conservation, selection and breeding of ornamental cultivars. A major difficulty in charting the breeding history of the di locus arises from the uncertain identity and classification of many cultivars, probably as a consequence of the long lasting material exchanges via seeds or bud-sticks, particularly across China, Japan, and more recently Western countries. Despite this, phylogenetic and population structure studies have consistently shown an evident differentiation of the ornamental peach and hybrids clusters (from P. davidiana, such as ‘Bai Hua Shan Bi Tao’ and ‘Fen Hua Shan Bi Tao’) from the ‘edible’ peach groups of landraces and improved cultivars [42–44]. Also, a certain degree of subpopulation differentiation has been reported within the ornamental peach cluster [35, 45], although the genetic relationships among the subgroups mainly reflect the growth habits (i.e. dwarf, fastigiated, weeping, upright or standard) rather than a (putative) different origin of DF alleles. Furthermore, different mutations from those described could also have arisen in different collections, and propagated locally. An example could be ‘Hua Yu Lu’ in which the reported DF phenotype could be due to an heterozygous SNP within the miR172 recognition sequence of the PET gene (Supplementary Figure S4). While the effective presence of this polymorphism should be further validated, the effects of single nucleotide mutations altering the miR172 seed region in PETALOSA gene orthologs have already been proven to induce the development of extra-numerary petals in gene-edited tobacco plants [27]. Other than the induction of flower supernumerary organs, di allelic variants cannot explain the range of differences in the number of extra-petals found in recessive DF accessions. In case of the dominant PET-Di2 mutation, an allele–dosage effect on average petal number explained most of the variability, with an increase of supernumerary petals in homozygous (Di2/Di2) versus heterozygous (Di2/di2) individuals [24], but the recessive nature of di mutations excludes such an effect (i.e. heterozygous Di/di individuals have single-flowers). While the de-regulation of PETALOSA genes has been indicated as responsible for the formation of extra-numerary flower structures in a variety of species, it is likely that additional layers of interaction between different euAP2 and/or MADS-box genes are in place to regulate flower organ formation. In a miR172d-deficient background, genotype-specific differences in the expression pattern of other homeotic genes could affect both meristem size and the conversion of stamens into petaloid structures. The existence of different interacting factors in determining petal number in di/di backgrounds had already been put forward by Lammerts (1945), and it has to be taken into account that miR172 is a key regulator of all euAP2 genes, and it is therefore expected that in miR172d-deficient individuals the activity of additional euAP2 could be prolonged. Transcripts for two euAP2 genes (Prupe.6G231700 and Prupe.6G091100) other than that for PETALOSA (Prupe.6G242400) were already reported in developing peach buds [24], but their precise tissue specificity and role in flower development are not known. Further work would be necessary to dissect their function and the effects of a possible de-regulation of the transcripts of these genes in the floral meristem a di/di background, taking also into account that environmental cues could also play a role: RcAP2 (a non-PETALOSA euAP2 gene sharing high similarity with Prupe.6G231700) has been suggested to regulate the conversion of stamens into petals in DF roses grown in different temperature conditions, with a variation in petal number of to up to three-fold [46]. Furthermore, in peach, a strong correlation has been observed between blooming date and either petal or sepal number in different segregating progenies, suggesting a link between flower morphology and phenology [30, 47]. Therefore, also in light of the changing climate conditions in many parts of the world, different genetic, environmental and/or G x E factors will have to be taken into consideration not only for crop species but also for ornamentals: to these ends, the information and characterized mutants already obtained in peach will be extremely valuable for future studies.

Conclusions

The identification of three independent mutations associated with the di locus responsible for the recessive double-flower phenotype unequivocally demonstrated the essential function of miR172 for floral identity and patterning in peach. These findings reinforce the evidences around the pivotal role of the miR172/euAP2 module and associated genetic variants in the creation of diverse flower forms and shapes, as previously advanced by the discovery of miR172-insensitive PETALOSA alleles. The allelic spectrum at the di (miR172d) and Di2 (PETALOSA gene) loci explains almost completely the appearance of DF in peach. This information may be translated to other species and pave the way to an understanding of the formation of DF in different ornamentals.

Methods

Plant materials

Leaf samples and photos of the 18 peach accessions used in this study were kindly provided by institution from various countries or directly acquired from nurseries, as specified in Table 1: accessions ‘Crimson Rocket’, ‘Hokimomo op’, KV045590, KV021779, Redleaf Pillar, Kikoumomo D (KV044770), KV872615 and Compact Pillar by C. Dardick (USDA-ARS, Appalachian Fruit Research Station, Kearneysville, West Virginia); ‘Helen Borchers’ by Chen Chunxian (USDA-ARS, Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, Byron, Georgia; ‘Peppermint Stick redleaves clone’ by K. Gasic (Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina); ‘S10321 Hua 5-15’, ‘S10322 Hua 5-25’ and the orginal source of ‘S7258 clone IRAN 6:59’ by B. Quilot (INRAE, Unit Genetics and Breeding of Fruit and Vegetables, Avignone, France). Commercial cultivars ‘Taoflora pink’ and ‘Taoflora white’ were provided by private nurseries. Trees of the accessions ‘Klara Meyer’ (from Kaneppele nursery, Trentino-Alto Adige, Italy), ‘S7258 clone IRAN 6:59’, ‘G. Biffi fiore doppio’ and ‘Okinawa’, as well as additional 151 accessions from the PeachRefPop collection were maintained at ASTRA-M. Neri farm ‘La Brusca’ (Imola, Italy). Accessions can be divided into either single or double flowers, the last including both double and semi-double types.

MinION library preparation, sequencing and analysis

High molecular weight (HMW) DNA was extracted following the protocol described by Li et al. [48]. The integrity and purity of the extracted DNA were evaluated in a 0.5% agarose gel electrophoresis run and with Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO (Thermo Fischer Scientific), respectively. DNA was quantified using the Invitrogen Qubit fluorimeter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts). Library preparation for amplicon sequencing was achieved using the 1D Genomic DNA by ligation protocol (SQK-LSK109; ONT, Oxford, United Kingdom), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, each sequencing library was prepared using 1.5 μg of high molecular weight genomic DNA extracted from nuclei. Sequencing was performed on a R9.4.1 flow-cell (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, ONT, United Kingdom) on a MinION Mk1b device. Each sample was run individually in a different flow cell. The basecalling of the ONT long reads was performed by Guppy v. 5.0.13 within the MK1C device. Reads were aligned against the peach V2.0 reference genome [49] using GraphMap Aligner [50], converted into bam files using SAMtools software [51]. True alignment was considered for both positive and negative strands following the GraphMap parameters for correct alignment. Each read was assigned with a quality indicator (mapQ), and those reads with a quality score ≥40 were accepted for inferences, while reads with quality rate ≤40 were not considered as a true alignment. IGV software [52] was used for visual exploration of sequencing data and retrieval of informative reads.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Genomic structure of the micro-RNA gene miR172d encoding transcript Prupe.2G237700 was identified by mapping RNAseq reads from various flower tissue libraries (carpel, petal, stamen, PRJNA493230) against peach V2.0 genome reference using STAR [53]. Genomic DNA was extracted from 200 μg of leaf tissue using a CTAB modified method [54] and 20 ng for each sample were used in PCR reactions using GoTaq Long PCR Master Mix (Promega) in a total volume of 10 ul and the appropriate primer combinations (Supplementary File S1), 5’-3’ strand: 2G237700_F1 (GTTTTACCATGTGGTCCCTGGG) and 2G237700_R2 (GACCAGTATCTAAATGTTTTACCTG) as pre-miR172 specific primers; diDEL_A_For (CAACATTGGATTACACACACTTC), diDEL_B_Rev (TGTCCAGTATAAACTGTAGTGGC), diDELwt_C_For (CGCTGATATTTGAAGGGTTTCAC) and diDELwt_D_Rev (TGTCAGAAACTTGATTCCAAGAC) specifics for diΔ variant and wild-type control; 2G237700_F1 and 2G237700_di1_Rev (ACTCATCAGCCACATCAGATGG) for di1 variant; 2G237700_di2_For (AGGACTATTTAACCCAGTCCAG) and 2G237700_R1 (TCATGATATCATCACGCCCATG) for di2 variant. PCR cycles were as follow: initial denaturation at 94° C for 30 sec., annealing at 58° C for 30 sec., extension at 65° for 4 min. (32 cycles) and final extension at 72° C for 5 min. The PETALOSA deletion variant at the Di2 locus was genotyped using primers reported in Gattolin et al. [24].

RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA was collected from pooled flower bud tissues from Baggiolini stage B (flower bud swelling) to C1 (flower buds apparent). RNA was treated with DNase I (Takara) and extracted using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by phenol extraction; 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamers and SuperScript III RT (Thermo Fisher Scientific). According to Zhu et al. (2012), specific primers for pre-miR172d amplify a 90 bp region including mature miR172d, located 84 nt from the 5’-prime end of the precursor sequence (Supplementary File S1): pre-miR172d_For (AGCATCATCAAGATTCACAATTTC) and pre-miR172d_Rev (TGCCGCTGCAGCATCATCAAGA). Real-time PCR reaction were carried out using Power SYBR Green qPCR Supermix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each reaction was performed in triplicate on QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR Systems (Thermo Fisher, United Kingdom) using the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 20 s, 56°C for 25 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Each thermal cycle was followed by a melting curve stage, with temperatures ranging from 60°C to 95°C. Pre-miR172d relative expression was calculated using ∆Ct method [55], using Actin (Prupe.6G163400) as reference gene [56]. RT-PCR products were run on 2.0% agarose gels with Midori staining and visualized under UV light. Three to four biological pool replicates were analyzed for each sample.

Sequence-based genotyping

For sequencing-based method, Illumina genomic resequencing data of peach and wild relatives accessions were retrieved from the SRA database of NCBI (Supplementary Table S2). The pri-miR172d wild-type genomic regions adjacent to the insertion/deletion breakpoints were blasted against cleaned reads of each accession. Variant(s) were deemed to occur when truncated reads were identified in wild-type sequences, and, as a control, overlapped reads were detected using the specific polymorphic allele.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure S1. Pattern of Linkage disequilibrium decay around di locus (chromosome 2) estimated from whole-genome sequencing data retrieved from Meng et al. (2019) [21].

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure S2. PCR-based identification of di1 and diΔ alleles at di locus and primers positions. Samples 1 – 7: di1 allele specific genotyping in ‘Hokimomo op’, ‘KV872615’, ‘Compact Pillar’, ‘Peppermint Stick cl.’, ‘Redleaf Pillar’, ‘S10322 Hua 5-25’ and ‘Okinawa’ accessions with primers 2G237700_F1 and 2G237700_di1_Rev; samples 8 – 10: diΔ allele specific genotyping in ‘Taoflora pink’, ‘Taoflora white’ and ‘Klara Meyer’ accessions with primers diDEL_A_For and diDELwt_D_Rev.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Figure S3. Allele mining at di and Di2 loci in peach germplasm using a sequence-based method. Exemplificative outputs were provided for homozygous di1/di1 and di2/di2 genotypes (‘Sa Hong Long Zhu Tao’ and ‘Hong Hua Bi Tao’), and a heterozygous di1/di2 (‘Ju Hua Tao’). Arrows indicate the position of di1 (left) and di2 (right) insertions.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Figure S4. Single nucleotide polymorphism detected within the miR172 seed region of PETALOSA gene (Prupe.6G242400) at the Di2 locus in the double-flower ‘Hua Yu Lu’ accessions. The PET deletion variant near the C terminus (Pp06:24,074,355 - 24,075,350) is also indicated.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Figure S5. Picture of the agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products used in Fig. 2.

Additional file 6: Supplementary Figure S6. Picture of the agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products used in Fig. S2.

Additional file 7: Supplementary File S1. DNA sequence of the diΔ, di1 and di2 variants. Prupe.2G237700 is highlighted in green with the boxed pre-miR172 sequence. The deletion is indicated in diΔ with strikethrough text while the insertions in di1 and di2 are highlighted in orange and yellow, respectively. Primers used for genotyping are marked as bold, underlined sequences. Primers used for RT-qPCR analysis are shown on a portion of the pre-miR172d sequence.

Additional file 8: Supplementary Table S1. Gene models were annotated in interval between SNP1456516 (24,277,038) and SNP1501405 (26,628,544), based on a peach reference transcripts v2.1 annotations. Best homology hit and percentage of identity to Arabidopsis gene models are indicated.

Additional file 9: Supplementary Table S2. Analysis of allelic variant on WGS data retrieved from NCBI SRA database of 41 peach accessions. The presence of di1/di1, di2/di2 and di1/di2 genotypes or of PET alleles in Prupe.6G242400 was assessed. References to phenotype information about double-flower and other ornamental traits are also indicated. Accessions with unclear genotype at either di or Di2 loci were also included.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Francesca Moscatelli (Donnadipiante), Giovanni Geotti and Suzanne Lukas (Susigarden), Chris Dardick (USDA-ARS, Appalachian Fruit Research Station, Kearneysville, West Virginia), Chen Chunxian (USDA-ARS, Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, Byron, Georgia), Ksenja Gasic (Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina), Benedicte Quilot and Veronique Signoret (INRAE-GAFL Unit, Avignone, France) for kindly providing plant material and photos. Special thanks to Elena Galati (University of Milan, Department of Biosciences) for helping with high-molecular weight DNA integrity evaluation. We also thank Martina Lama and Stefano Foschi for their technical assistance in the field.

Authors’ contributions

MC and SG analyzed genome-wide re-sequencing data, developed the associated molecular markers, conceived and performed the experiments, drafted the manuscript; RC, IB and FEF performed genotyping, analyses of gene expression and linkage disequilibrium (LD) pattern. AM and ST performed ONT sequencing. DB and LR selected the genetic materials for the study and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partially supported by FREECLIMB project, and, also partially funded in the framework of MAS.PES Italian project.

Availability of data and materials

The sequences generated during the current study are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository under accession code PRJNA814062

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The peach plant material used in this study complies with the University of Milan Institutional Ethics Committee. The Prof. Marco Cirilli is in charge of the formal management of the plant materials.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marco Cirilli, Email: marco.cirilli@unimi.it.

Stefano Gattolin, Email: stefano.gattolin@ibba.cnr.it.

References

- 1.Zheng Y, Crawford GW, Chen X. Archaeological Evidence for Peach (Prunus persica) Cultivation and Domestication in China. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne DH, et al. Peach. In: Badenes M, Byrne D, et al., editors. Fruit Breeding. Handbook of Plant Breeding. Boston: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu D, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Zhang Q. The germplasm preservation of ornamental peach cultivars. Acta Hort. 2003;620:395–402. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2003.620.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Layne, D.R. and Bassi, D. (2008) The peach: Botany, production and uses. CABI Publishing ISBN-13: 9781845933869

- 5.Bowman JL, Smyth DR, Meyerowitz EM. Genetic interactions among floral homeotic genes of Arabidopsis. Development. 1991;112:1–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coen ES, Meyerowitz EM. (1991) The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature. 1991;353(6339):31–37. doi: 10.1038/353031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Causier B, Schwarz-Sommer Z, Davies B. (2010) Floral organ identity: 20 years of ABCs. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rijpkema AS, Vandenbussche M, Koes R, Heijmans K, Gerats T. Variations on a theme: Changes in the floral ABCs in angiosperms. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinyopich A, Ditta GS, Savidge B, Liljegren SJ, Baumann E, Wisman E, Yanofsky MF. Assessing the redundancy of MADS-box genes during carpel and ovule development. Nature. 2003;424:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature01741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jofuku KD, den Boer BGW, Montagu MV, Okamuro JK. Control of Arabidopsis flower and seed development by the homeotic gene APETALA2. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1211–1225. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290:2105–2110. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S, Soltis PS, Wall K, Soltis DE. Phylogeny and domain evolution in the APETALA2-like gene family. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:107–120. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao L, Kim Y, Dinh TT, Chen X. miR172 regulates stem cell fate and defines the inner boundary of APETALA3 and PISTILLATA expression domain in Arabidopsis floral meristems. Plant J. 2007;51:840–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wollmann H, Mica E, Todesco M, Long JA, Weigel D. On reconciling the interactions between APETALA2, miR172 and AGAMOUS with the ABC model of flower development. Development. 2010;137(21):3633–3642. doi: 10.1242/dev.036673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X. A microRNA as a translational repressor of APETALA2 in Arabidopsis flower development. Science. 2004;3:2022–2025. doi: 10.1126/science.1088060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C, Okie WR. Novel peach flower types in a segregating population from ‘Helen Borchers’. J Am Soc Hort Sci. 2015;140(2):172–177. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.140.2.172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaparro JX, Werner DJ, O'Malley D, Sederoff RR. Targeted mapping and linkage analysis of morphological, isozyme, and RAPD markers in peach. Theor Appl Genet. 1994;87:805–815. doi: 10.1007/BF00221132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajapakse S, Belthoff LE, He G, Estager AE, Scorza R, Verde I, Ballard RE, Baird WV, Callahan A, Monet R, Abbott AG. (1995) Genetic linkage mapping in peach using morphological, RFLP and RAPD markers. Theor Appl Genet. 1995;90(3-4):503–510. doi: 10.1007/BF00221996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dirlewanger E, Graziano E, Joobeur T, Garriga-Calderé F, Cosson P, Howad W, Arúus P. Comparative mapping and marker assisted selection in Rosaceae fruit crops. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9891–9896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao K, Zhou Z, Wang Q, Guo J, Zhao P, Zhu G, Wang L. Genome-wide association study of 12 agronomic traits in peach. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13246. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng G, Zhu G, Fang W, et al. Identification of loci for single/double flower trait by combining genome-wide association analysis and bulked segregant analysis in peach (Prunus persica) Plant Breed. 2019;138:360–367. doi: 10.1111/pbr.12673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dardick C, Callahan A, Horn R, Ruiz KB, Zhebentyayeva T, Hollender C, Whitaker M, Abbott A, Scorza R. PpeTAC1 promotes the horizontal growth of branches in peach trees and is a member of a functionally conserved gene family found in diverse plants species. Plant J. 2013;75(4):618–630. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckman TG, Chaparro JX, Sherman WB. Evidence for control of double flowering in peach via dominant single gene loci. Acta Hortic. 2012;962:139–141. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2012.962.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gattolin S, Cirilli M, Pacheco I, et al. Deletion of the miR172 target site in a TOE-type gene is a strong candidate variant for dominant double-flower trait in Rosaceae. Plant J. 2018;96:358–371. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma VK, Carles C, Fletcher JC. Maintenance of stem cell populations in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11823–11829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834206100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Z, Shi T, Zheng B, Yumul RE, Liu X, You C, Gao Z, Xiao L, Chen X. (2017) APETALA2 antagonizes the transcriptional activity of AGAMOUS in regulating floral stem cells in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2017;215(3):1197–1209. doi: 10.1111/nph.14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gattolin S, Cirilli M, Chessa S, et al. Mutations in orthologous PETALOSA TOE-type genes cause dominant double-flower phenotype in phylogenetically distant eudicots. J Exp Bot. 2020;71:2585–2595. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu H, Xia R, Zhao B, et al. Unique expression, processing regulation, and regulatory network of peach (Prunus persica) miRNAs. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma L, Li G. FAR1-RELATED SEQUENCE (FRS) and FRS-RELATED FACTOR (FRF) family proteins in Arabidopsis growth and development. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cirilli M, Micali S, Aranzana MJ, Arús P, Babini A, Barreneche T, et al. The Multisite PeachRefPop Collection: A True Cultural Heritage and International Scientific Tool for Fruit Trees. Plant Physiol. 2020;184(2):632–646. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin W, Gupta SK, Arazi T, Spitzer-Rimon B. (2021) MIR172d Is Required for Floral Organ Identity and Number in Tomato. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:4659. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan Q, Li S, Zhang Y, et al. Chromosome-level genome assemblies of five Prunus species and genome-wide association studies for key agronomic traits in peach. Hortic Res. 2021;8:213. doi: 10.1038/s41438-021-00648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshida MK, Yamane Y, Ijiro N, Fujishige M, Yamaguchi E, Takahashi. Studies on ornamental peach cultivars. Bul College Agr Utsunomiya Univ. 2000;17(3):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamazaki K, Okabe M, Takahashi E. New broomy flowering peach cultivars ‘Terutebeni’, ‘Terutemomo’, and ‘Teruteshiro’ (in Japanese) Bul Kanagawa Hort Expt Sta. 1987;34:54–56. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu D, Zhang Z, Zhang D, Zhang Q, Li J. Genetic relationships of ornamental peach determined using AFLP markers. HortScience. 2005;40:1782–1786. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.40.6.1782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scorza R, Bassi D, Liverani A. Genetic interactions of pillar (columnar), compact, and dwarf peach tree genotypes. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 2002;127(2):254–261. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.127.2.254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobsen AL. North American landscape trees. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowen HH. Breeding peaches for warm climates. HortScience. 1971;6:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okie, W.R. (1998) Handbook of peach and nectarine varieties: performance in the southeastern United States and index of names. USDA, Agriculture Handbook No 714, 814 p

- 40.Lammerts WE. The breeding of ornamental edible peaches for mild climates, 1: inheritance of tree and flower characters-I. Inheritance of tree and flower characters. Am J Bot. 1945;32:53–61. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1945.tb05086.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamaguchi M, Baba T, Suesada Y, Adachi E, Yamane T, Sawamura Y, Yaegaki H. Breeding and Characteristics of New Ornamental Peach Cultivars, ‘Hakurakuten’ and ‘Maihiten’, with Pillar Type Tree Shape and Chrysanthemum-like Flowers. Hort Res (Japan) 2018;17(4):475–482. doi: 10.2503/hrj.17.475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao K, Zheng Z, Wang L, Liu X, Zhu G, Fang W, et al. Comparative population genomics reveals the domestication history of the peach, Prunus persica, and human influences on perennial fruit crops. Genome Biol. 2014;15(7):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0415-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akagi T, Hanada T, Yaegaki H, Gradziel TM, Tao R. Genome-wide view of genetic diversity reveals paths of selection and cultivar differentiation in peach domestication. DNA Res. 2016;23(3):271–282. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cirilli M, Flati T, Gioiosa S, Tagliaferri I, Ciacciulli A, Gao Z, et al. PeachVar-DB: a curated collection of genetic variations for the interactive analysis of peach genome data. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59(1):e2. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu D, Zhang Z, Zhang D, Zhang W, Li J. Ornamental peach and its genetic relationships revealed by inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) fingerprints. Acta Hort. 2006;713:113–120. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2006.713.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han Y, Tang A, Wan H, Zhang T, Cheng T, Wang J, Yang W, Pan H, Zhang Q. (2018) An APETALA2 Homolog, RcAP2, Regulates the Number of Rose Petals Derived From Stamens and Response to Temperature Fluctuations. Front Plant Sci. 2018;12(9):481. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song, YH., Niu, L., Liu, S. & Wang, Z. (2010) Inheritance Tendency of Several Characters of Ornamental Peach. Acta Agricolturae Sinica, 25(2): 78-83

- 48.Li Z, Parris S, Saski CA. A simple plant high-molecular-weight DNA extraction method suitable for single-molecule technologies. Plant Methods. 2020;16:38. doi: 10.1186/s13007-020-00579-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verde I, Jenkins J, Dondini L, Micali S, Pagliarani G, Vendramin E, Schmutz J. The Peach v2. 0 release: high-resolution linkage mapping and deep resequencing improve chromosome-scale assembly and contiguity. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3606-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sović I, Šikić M, Wilm A, et al. Fast and sensitive mapping of nanopore sequencing reads with GraphMap. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11307. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li H, Durbin R. (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. (2013) STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Passaro M, Geuna F, Bassi D, Cirilli M. Development of a high-resolution melting approach for reliable and cost-effective genotyping of PPVres locus in apricot (P. armeniaca) Mol Breeding. 2017;37(6):74. doi: 10.1007/s11032-017-0666-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tatsuki M, Nakajima N, Fujii H, Shimada T, Nakano M, Hayashi K, Hayama H, Yoshioka H, Nakamura Y. Increased levels of IAA are required for system 2 ethylene synthesis causing fruit softening in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch) J Exp Bot. 2013;64:1049–1059. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure S1. Pattern of Linkage disequilibrium decay around di locus (chromosome 2) estimated from whole-genome sequencing data retrieved from Meng et al. (2019) [21].

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure S2. PCR-based identification of di1 and diΔ alleles at di locus and primers positions. Samples 1 – 7: di1 allele specific genotyping in ‘Hokimomo op’, ‘KV872615’, ‘Compact Pillar’, ‘Peppermint Stick cl.’, ‘Redleaf Pillar’, ‘S10322 Hua 5-25’ and ‘Okinawa’ accessions with primers 2G237700_F1 and 2G237700_di1_Rev; samples 8 – 10: diΔ allele specific genotyping in ‘Taoflora pink’, ‘Taoflora white’ and ‘Klara Meyer’ accessions with primers diDEL_A_For and diDELwt_D_Rev.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Figure S3. Allele mining at di and Di2 loci in peach germplasm using a sequence-based method. Exemplificative outputs were provided for homozygous di1/di1 and di2/di2 genotypes (‘Sa Hong Long Zhu Tao’ and ‘Hong Hua Bi Tao’), and a heterozygous di1/di2 (‘Ju Hua Tao’). Arrows indicate the position of di1 (left) and di2 (right) insertions.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Figure S4. Single nucleotide polymorphism detected within the miR172 seed region of PETALOSA gene (Prupe.6G242400) at the Di2 locus in the double-flower ‘Hua Yu Lu’ accessions. The PET deletion variant near the C terminus (Pp06:24,074,355 - 24,075,350) is also indicated.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Figure S5. Picture of the agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products used in Fig. 2.

Additional file 6: Supplementary Figure S6. Picture of the agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products used in Fig. S2.

Additional file 7: Supplementary File S1. DNA sequence of the diΔ, di1 and di2 variants. Prupe.2G237700 is highlighted in green with the boxed pre-miR172 sequence. The deletion is indicated in diΔ with strikethrough text while the insertions in di1 and di2 are highlighted in orange and yellow, respectively. Primers used for genotyping are marked as bold, underlined sequences. Primers used for RT-qPCR analysis are shown on a portion of the pre-miR172d sequence.

Additional file 8: Supplementary Table S1. Gene models were annotated in interval between SNP1456516 (24,277,038) and SNP1501405 (26,628,544), based on a peach reference transcripts v2.1 annotations. Best homology hit and percentage of identity to Arabidopsis gene models are indicated.

Additional file 9: Supplementary Table S2. Analysis of allelic variant on WGS data retrieved from NCBI SRA database of 41 peach accessions. The presence of di1/di1, di2/di2 and di1/di2 genotypes or of PET alleles in Prupe.6G242400 was assessed. References to phenotype information about double-flower and other ornamental traits are also indicated. Accessions with unclear genotype at either di or Di2 loci were also included.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences generated during the current study are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository under accession code PRJNA814062