Abstract

Purpose:

To determine the extent of geographic variation in the proportion of patients with newly-diagnosed open angle glaucoma (OAG) undergoing visual field (VF) testing, fundus photography (FP), and other ocular imaging (OOI) among patients residing in different U.S. communities.

Design:

Retrospective longitudinal cohort study

Participants:

All enrollees with newly-diagnosed OAG enrolled in a managed care network between 2001-2014

Methods:

We identified all persons in the plan with incident OAG residing in 201 communities across the U.S. All communities contributed ≥ 20 enrollees. The proportion of enrollees undergoing ≥ 1 VF, FP, OOI, and no testing of any type in the 2 years after first OAG diagnosis was determined for each community and comparisons were made to assess the extent of variation in utilization of diagnostic testing among patients residing in the different communities.

Main Outcome Measures:

Receipt of VF testing, FP, OOI, or none of these tests in the 2 years after initial OAG diagnosis

Results:

Of the 56675 enrollees with newly-diagnosed OAG, the mean proportion of patients undergoing VF testing within two years of initial diagnosis was 74% ± 7%, ranging from as low as 51% in Rochester, MN to as high as 95% in Lancaster, PA. The mean proportion undergoing OOI was 63% ± 10% and varied from 34% in Palm Springs/Rancho Mira, CA to 85% in Charleston, SC. The mean proportion receiving FP was 26% ± 10% and ranged from as low as 3% in Fresno, CA to as high as 57% in Harlingen, TX. The proportion undergoing no glaucoma testing ranged from 0% in Binghamton, NY to as high as 35% in two communities.

Conclusions:

In many U.S. communities a high proportion of patients are undergoing testing according to established practice guidelines. However, in several communities, fewer than 60% of patients with newly diagnosed OAG are undergoing VF testing in the 2 years after initial OAG diagnosis and in a few communities over 1 in 4 patients have no record of glaucoma diagnostic testing of any type. Additional research is needed to understand factors driving this variation in practice patterns and its impact on patient outcomes.

Precis

Among 56675 insured patients with newly-diagnosed open-angle glaucoma, the proportions undergoing diagnostic testing (perimetry, fundus photography, other ocular imaging) within 2 years of first diagnosis can vary considerably depending on the enrollee’s community of residence.

Open-angle glaucoma (OAG) is a sight-threatening condition that affects more than 3 million people in the United States (U.S.) and millions more worldwide.1 With the aging of the baby boomer generation, that number is expected to rise to over 7 million in the U.S. by the year 2050.1 Most patients with OAG are asymptomatic until they have suffered a substantial amount of damage to the optic nerve. As such, without careful monitoring with diagnostic testing such as perimetry and careful assessment of the optic nerve, patients are at risk for experiencing potentially preventable disease progression and irreversible vision loss before they become aware of it. Furthermore, these glaucoma tests are useful for distinguishing persons with ocular hypertension from those with bona fide glaucoma, staging the disease based on the extent of damage present, and for establishing appropriate target pressures. It is essential to detect and treat OAG before it advances to more advanced stages when it impacts the ability of patients to perform daily activities such as reading, driving and caring for themselves,2-4 and the cost of glaucoma treatment and health economic burden increase substantially.5

The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) provides Preferred Practice Patterns (PPP) that serve as guidelines to aid clinicians in the diagnosis and management of patients with OAG.6 Guidelines published during 2003 to 2010 recommend VF testing and optic nerve evaluation and documentation (e.g. color stereophotography, computer-based analysis or nonstereoscopic photograph or drawing) at least once every 12 months for persons with primary OAG.6 Previous studies have demonstrated varying degrees in conformance with these guidelines.7-10 In these prior studies, the proportion of patients undergoing these tests varied widely from 66% to 92% for perimetry and 23% to 93% for optic nerve photography.7-10 Most of these earlier studies were conducted well over a decade ago, before the widespread use of optical coherence tomography (OCT) an ancillary test to monitor patients with OAG.

The purpose of this study is to examine geographic variation in the rate of VF testing, FP and OOI for patients with newly-diagnosed OAG residing in different communities throughout the U.S to identify communities where conformance with practice guidelines is better or worse than others. By identifying communities where conformance to practice guidelines for glaucoma management is high, researchers may be able to look at care in these communities to identify ways to improve conformance in other communities where it is suboptimal.

Methods

Data Source

Data was obtained from the Clinformatics DataMart database (OptumInsight, Eden Prairie, MN). This dataset contains detailed de-identified records of enrollees in a large U.S. managed-care network. The data available included beneficiaries receiving any form of eye care from January 1, 2001 through December 31, 2014. This subset of beneficiaries had ≥1 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for any eye-related diagnosis (360-379.9) or Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition, code for any eye-related visits, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures (65091-68899 or 92002-92499), or any other claims submitted by an ophthalmologist or optometrist during the beneficiary’s time in the medical plan.11,12 We had access to enrollees’ medical claims (inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing facility) for all ocular and non-ocular conditions, as well as their sociodemographic information (age, sex, race, education, income). Since the data were de-identified to the researchers, the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved this as a non-regulated study.

Participant Selection

We identified all enrollees age ≥ 40 years who had ≥ 1 diagnosis of OAG (ICD-9-CM codes 365.1, 365.10, 365.11, 365.12, and 365.15). As the objective was to evaluate diagnostic testing among those with newly-diagnosed OAG, those with 1 or more pre-existing diagnosis of OAG identified during a one year look-back period were excluded from analysis. We also required a confirmatory diagnosis of OAG after the initial diagnosis on a separate date to help ensure the patient did indeed have this condition. Enrollees who were not continuously enrolled in the plan for the entire 2 years following initial OAG diagnosis were excluded since they may have undergone testing during the times outside of the plan. Patients with other forms of glaucoma and glaucoma suspects were not considered for these analyses.

Communities of Residence

To identify communities where care was being received, we divided the U.S. into 306 hospital referral regions (HRRs). In brief, each HRR represents a regional health care market for tertiary medical care.13,14 HRRs have been used extensively to assess geographic variation in health care services in other areas of medicine.15-17 Enrollees were assigned to a given HRR based on their zip code of residence at the time of enrollment in the health plan. Communities with fewer than 20 eligible enrollees with incident OAG were excluded, leaving a total of 201 HRRs available for data analysis.

Receipt of Glaucoma Diagnostic Testing

The key outcome of interest was receipt of VF testing (CPT 92081, 92082, and 92083), FP (CPT 92250), or OOI (CPT 92133 or 92135) in the 24 months following initial diagnosis of OAG. Other ocular imaging includes imaging modalities such as OCT, confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (CSLO), and scanning laser polarimetry (SLP).

Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Enrollees’ characteristics were summarized for the entire sample using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. The proportion of enrollees undergoing ≥ 1 of a given test in the 24 months following initial OAG diagnosis was determined for enrollees residing in each HRR. Comparisons of the proportions undergoing each specific diagnostic test and persons with no record of any of the 3 diagnostic tests in the 24 months after initial OAG diagnosis were performed among the HRRs. We also looked at communities that had high proportions of patients undergoing OOI testing but no VF testing as prior work from our group has demonstrated trends of increasing utilization of OOI coupled with decreasing utilization of VF testing and we wished to explore how common this monitoring pattern occurs among persons living in different communities.18 We also assessed proportions of enrollees in each HRR who received ≥1 VF and no record of OOI, proportions of enrollees who received either FP or OOI, and proportions who underwent gonioscopy in the 24 months following initial OAG diagnosis.

As a subanalysis, we determined the proportions of enrollees in each HRR who were considered overutilizers of glaucoma testing. We defined overutilization as receipt of ≥4 VFs, ≥4 OOI tests, or ≥4 FP tests in the 2 year follow-up period after initial OAG diagnosis. Patients with comorbid retinal diseases were excluded from this subanalysis since certain retinal conditions require frequent use of OCT to monitor them.

In another subanalysis, we identified a subset of HRRs that had at least 20 patients with OAG who were under the exclusive care of ophthalmologists and 20 or more patients who were under the exclusive care of optometrists. In each of these communities, we compared the proportion of patients undergoing VF, FP, OOI, and no testing in the 24 months following initial OAG diagnosis among those under exclusive care by an ophthalmologist versus those under exclusive care by an optometrist. Comparisons of the proportions undergoing each of these tests were performed using chi-square and Fisher exact tests, accounting for multiple comparisons.

Results

Demographics

There were 56675 enrollees who met the study inclusion criterion. The mean ± SD age of enrollees at the time of initial OAG diagnosis was 68.1 ±14.0 years. Patients were followed in the plan for an average of 8.5 ± 2.8 years. There were 38800 whites (72.7%), 7824 blacks (14.7%), 5000 Latinos (9.4%), and 1778 Asian Americans (3.3%). There were 32424 (57.2%) women and 11833 (25.7%) enrollees had an income of ≥ $100000 per year. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Sample

| Variable | Value | Incident OAG N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 56,675 | |

| Age (yrs) at First OAG Diagnosis | 68.1 (14.0) | |

| Time (yrs) in Plan | 8.5 (2.8) | |

| Sex | Male | 24,251 (42.8) |

| Female | 32,424 (57.2) | |

| Race | White | 38,800 (72.7) |

| Black | 7,824 (14.7) | |

| Latino | 5,000 (9.4) | |

| Asian | 1,778 (3.3) | |

| Income | < $40K | 15,297 (33.2) |

| $40K - $59K | 8,174 (17.8) | |

| $60K - $99K | 10,704 (23.3) | |

| ≥ $100K | 11,833 (25.7) | |

| Education | Less than High School | 454 (0.8) |

| High School Diploma | 16,534 (29.9) | |

| Some College | 29,547 (53.4) | |

| Bachelor Degree or More | 8,772 (15.9) | |

| Diabetes | None | 32,852 (58.0) |

| Uncomplicated | 11,410 (20.1) | |

| Complicated | 12,413 (21.9) | |

| Clinical Risk Group | 1 (Healthiest) | 323 (0.6) |

| 2 | 6,049 (10.7) | |

| 3 | 46,128 (81.4) | |

| 4 (Least healthy) | 4,175 (7.4) |

OAG = Open Angle Glaucoma. Uncomplicated Diabetes = Presence of diabetes with no related end-organ damage. Complicated Diabetes = Presence of diabetes with related end-organ damage

There were 3273 persons with missing information on race, there were 10667 persons with missing information on income, and 1368 persons missing information on education.

Two hundred and one communities had ≥ 20 enrollees with newly-diagnosed OAG. The mean number of patients with newly-diagnosed OAG contributing data to a given HRR was 254.3 ± 404.0 and the mean number of eye care providers evaluating patients who were residing in a given HRR over the 2 year period following diagnosis (for OAG and other reasons) was 114.7 ± 145.5. When comparing the characteristics of the 201 HRRs that were included in these analyses to the others that had inadequately large numbers of patients with newly-diagnosed OAG, the HRRs that were included had more enrollees in this managed care network residing in them (mean (SD) number of beneficiaries in the plan 82369 (123503) vs. 7186 (5483), p<0.0001), they had greater numbers of ophthalmologists / 100K population (4.9/100K vs. 4.4/100K, p=0.002) and more were designated as urban HRRs, defined as ≥250 persons per square mile (28.9% vs. 15.4%, p=0.01).

Rates of Diagnostic Testing

Visual Field Testing

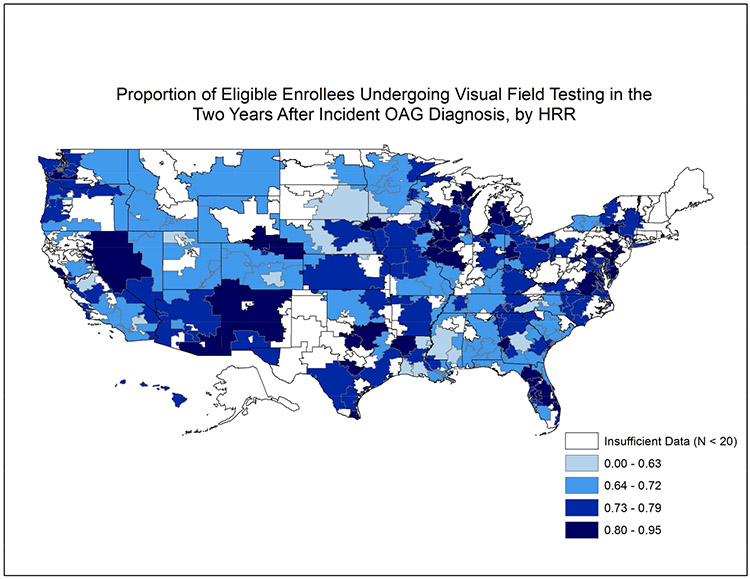

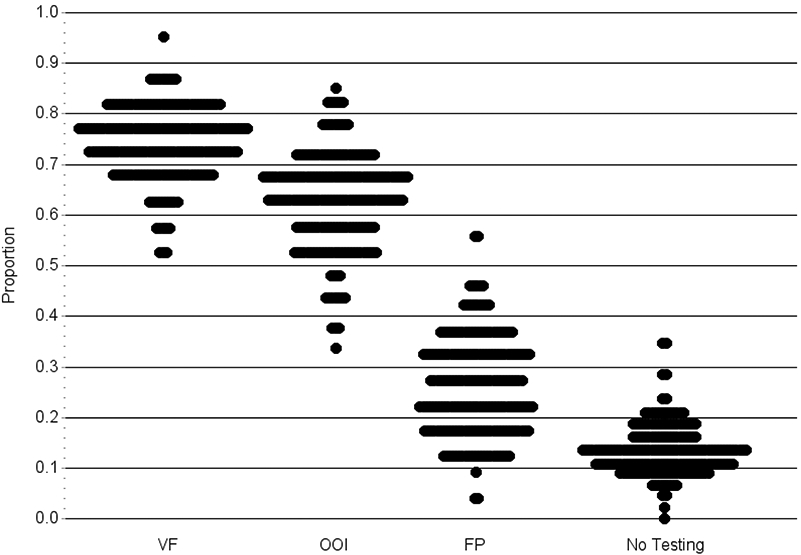

Of the 56675 enrollees with newly-diagnosed OAG, 42142 (74.4%) of them underwent VF testing at least once in the two years following initial diagnosis (Online Figure 1, available at http://aaojournal.org). Among the 201 HRRs studied, the mean ± SD proportion of patients receiving ≥ 1 VF testing in the 2 years after initial OAG diagnosis across HRRs was 74% ± 7%. Figure 1 shows the proportion of enrollees undergoing VF testing for the 201 communities studied. The rate of VF testing ranged from as low as 51% in Rochester, MN to as high as 95% in Lancaster, PA. (Table 2) The interquartile range (25th to 75th percentile) for perimetric testing among the communities studied was 69.8% to 79.3%. (Figure 2)

Figure 1: Utilization of Visual Field Testing in the Two Years Following Incident Glaucoma Diagnosis Among Communities Throughout the United States.

Map of the United States divided into 306 hospital referral regions. Communities with larger proportions of patients receiving visual field testing in the 2 years after initial open-angle glaucoma diagnosis are shaded dark colors relative to other communities with lower proportions of patients undergoing perimetry. Communities shaded white had fewer than 20 enrollees with newly-diagnosed open-angle glaucoma.

HRR = hospital referral region

Table 2.

Communities with highest and lowest proportion of newly diagnosed patients with open-angle glaucoma undergoing diagnostic testing in the two years after initial glaucoma diagnosis

| Highest | Lowest | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRR | Number Patients |

Number Providers |

Proportion | HRR | Number Patients |

Number Providers |

Proportion | |

| VF | Lancaster, PA | 21 | 25 | 0.952 | Rochester, MN | 49 | 30 | 0.510 |

| Wilmington, DE | 28 | 31 | 0.893 | Palm Springs/Rancho Mira, CA | 95 | 26 | 0.516 | |

| Davenport, IA | 52 | 24 | 0.885 | Dubuque, IA | 31 | 19 | 0.548 | |

| Santa Rosa, CA | 62 | 37 | 0.871 | Hickory, NC | 29 | 16 | 0.552 | |

| Olympia, WA | 46 | 51 | 0.870 | Modesto, CA | 206 | 41 | 0.568 | |

| Rockford, IL | 23 | 25 | 0.870 | Hackensack, NJ | 21 | 18 | 0.571 | |

| San Mateo County, CA | 188 | 81 | 0.862 | Macon, GA | 332 | 164 | 0.584 | |

| Lansing, MI | 43 | 33 | 0.861 | Lafayette, LA | 97 | 50 | 0.588 | |

| White Plains, NY | 113 | 110 | 0.858 | Lake Charles, LA | 61 | 28 | 0.607 | |

| Peoria, IL | 21 | 22 | 0.857 | Asheville, NC | 72 | 60 | 0.611 | |

| HRR | Number Patients |

Number Providers |

Proportion | HRR | Number Patients |

Number Providers |

Proportion | |

| OOI | Charleston, SC | 40 | 36 | 0.850 | Palm Springs/Rancho Mira, CA | 95 | 26 | 0.337 |

| Norfolk, VA | 31 | 32 | 0.839 | Kalamazoo, MI | 44 | 36 | 0.364 | |

| Clearwater, FL | 636 | 267 | 0.829 | Hickory, NC | 29 | 16 | 0.379 | |

| Davenport, IA | 52 | 24 | 0.827 | Birmingham, AL | 776 | 311 | 0.385 | |

| Neenah, WI | 45 | 39 | 0.822 | Santa Barbara, CA | 97 | 18 | 0.423 | |

| Lafayette, LA | 97 | 50 | 0.814 | Monroe, LA | 21 | 13 | 0.429 | |

| Waterloo, IA | 61 | 32 | 0.803 | Meridian, MS | 23 | 15 | 0.435 | |

| Wilmington, NC | 99 | 58 | 0.798 | Rochester, NY | 43 | 40 | 0.442 | |

| Reno, NV | 34 | 26 | 0.794 | Greenville, SC | 43 | 38 | 0.442 | |

| Allentown, PA | 66 | 49 | 0.788 | Mobile, AL | 423 | 121 | 0.444 | |

| HRR | Number Patients |

Number Providers |

Proportion | HRR | Number Patients |

Number Providers |

Proportion | |

| FP | Harlingen, TX | 23 | 23 | 0.565 | Fresno, CA | 31 | 9 | 0.032 |

| Royal Oak, MI | 20 | 23 | 0.550 | Ormond Beach, FL | 63 | 47 | 0.048 | |

| Lancaster, PA | 21 | 25 | 0.476 | Salem, OR | 43 | 24 | 0.093 | |

| Ocala, FL | 85 | 80 | 0.459 | Eugene, OR | 120 | 67 | 0.100 | |

| Binghamton, NY | 24 | 17 | 0.458 | La Crosse, WI | 30 | 24 | 0.100 | |

| Santa Barbara, CA | 97 | 18 | 0.454 | Shreveport, LA | 79 | 40 | 0.101 | |

| Fort Lauderdale, FL | 791 | 451 | 0.451 | Boise, ID | 98 | 54 | 0.102 | |

| Lansing, MI | 43 | 33 | 0.442 | Rochester, MN | 49 | 30 | 0.102 | |

| Takoma Park, MD | 150 | 87 | 0.440 | Toledo, OH | 29 | 26 | 0.103 | |

| Dothan, AL | 28 | 29 | 0.429 | Billings, MT | 47 | 33 | 0.106 | |

| HRR | Number Patients |

Number Providers |

Proportion | HRR | Number Patients |

Number Providers |

Proportion | |

| No Testing | Palm Springs/Rancho Mira, CA | 95 | 26 | 0.347 | Binghamton, NY | 24 | 17 | 0.000 |

| Hickory, NC | 29 | 16 | 0.345 | Olympia, WA | 46 | 51 | 0.022 | |

| Rochester, MN | 49 | 30 | 0.286 | Grand Rapids, MI | 22 | 23 | 0.046 | |

| Monroe, LA | 21 | 13 | 0.286 | Lancaster, PA | 21 | 25 | 0.048 | |

| Munster, IN | 37 | 23 | 0.243 | Reno, NV | 34 | 26 | 0.059 | |

| Salem, OR | 43 | 24 | 0.233 | Roanoke, VA | 33 | 27 | 0.061 | |

| Jackson, MS | 76 | 49 | 0.224 | White Plains, NY | 113 | 110 | 0.062 | |

| Modesto, CA | 206 | 41 | 0.223 | Clearwater, FL | 636 | 267 | 0.063 | |

| Montgomery, AL | 74 | 53 | 0.216 | Syracuse, NY | 60 | 55 | 0.067 | |

| Blue Island, IL | 51 | 40 | 0.216 | Newport News, VA | 29 | 28 | 0.069 | |

HRR = hospital referral region; VF = visual field; OOI = other ocular imaging; FP = fundus photography

No testing means no record of receipt of one or more visual fields, fundus photographs, or other ocular imaging in the 24 months following glaucoma diagnosis. “Number of patients” refers to number of enrollees with newly-diagnosed glaucoma who resided in the community during the study period and met the inclusion criteria. “Number of providers: refers to the number of ophtthalmologists and optometrists caring for all the enrollees residing in a given community during the 2 years after their initial glaucoma diagnosis. These providers may have been providing care for glaucoma or other reasons and some enrollees may have travelled outside their HRR of residence to seek care by some providers.

Figure 2: Turnip Graph Showing the Proportion of Patients with Incident Open-Angle Glaucoma Who Underwent Visual Field Testing, Fundus Photography, Other Ocular Imaging, and None of These Tests in the Two Years After Initial Diagnosis for Communities Throughout the United States.

Each dot on the plot represents a specific hospital referral region.

Plots that are short and wide depict little variation in utilization and few outlier communities. Plots that are long and narrow reflect lots of variation in utilization with many outlier communities.

VF = Visual Field; FP = Fundus photography; OOI = Other ocular imaging

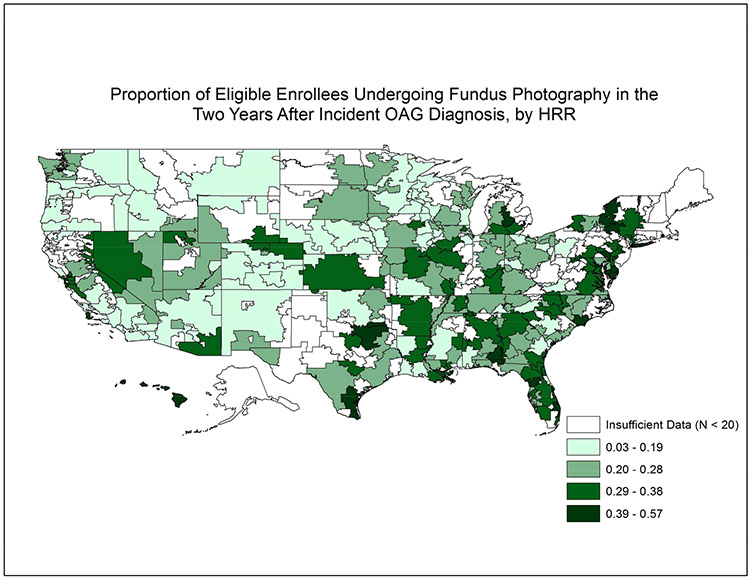

Fundus Photography

Overall, rates of receiving FP were considerably lower than VF testing. Only 15267 (26.9%) of eligible enrollees received ≥ 1 FP in the 2 years following initial OAG diagnosis. (Online Figure 1, available at http://aaojournal.org) Among the 201 HRRs studied, the mean ± SD proportion receiving ≥ 1 FP across HRRs was 26% ± 10%. Figure 3 shows the proportion of enrollees undergoing FP for the 201 communities studied. The proportion receiving FP in two years following initial OAG diagnosis ranged from as low as 3% in Fresno, CA to as high as 57% in Harlingen, TX. (Table 2) The interquartile range for FP in the 2 years after initial OAG diagnosis among the communities studied was 18.5% to 33.3%. (Figure 2)

Figure 3: Utilization of Fundus Photography in the Two Years Following Incident Glaucoma Diagnosis Among Communities Throughout the United States.

Map of the United States divided into 306 hospital referral regions. Communities with larger proportions of patients receiving fundus photography in the 2 years after initial open-angle glaucoma diagnosis are shaded dark colors relative to other communities with lower proportions of patients undergoing fundus photography. Communities shaded white had fewer than 20 enrollees with newly-diagnosed open-angle glaucoma.

HRR = hospital referral region

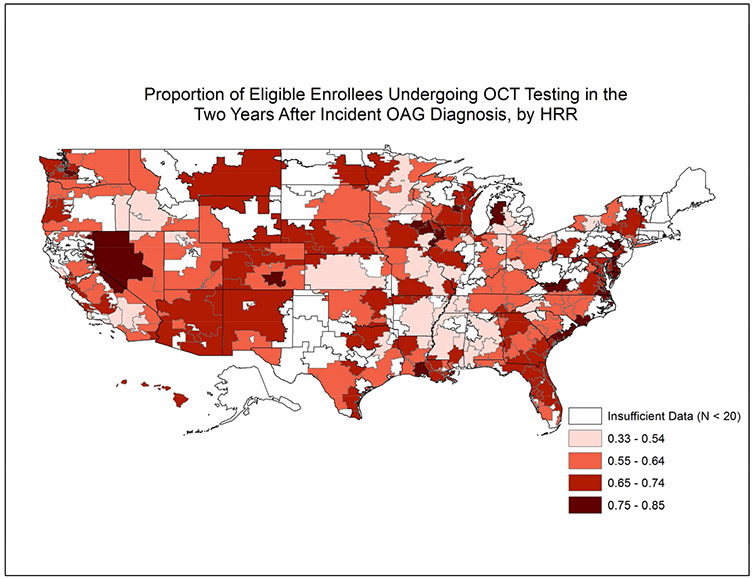

Other Ocular Imaging

Overall, 34951 (61.7%) enrollees received OOI in the two years after initial OAG diagnosis (Online Figure 1, available at http://aaojournal.org). The mean ± SD proportion of enrollees receiving ≥ 1 OOI test across HRRs was 63% ± 10%. Figure 4 shows the proportion of enrollees undergoing OOI for the 201 communities studied. The proportion undergoing OOI in the two years following initial OAG diagnosis varied from as low as 34% in Palm Springs/Rancho Mira, CA to 85% in Charleston, SC. (Table 2) The interquartile range for OOI in the 2 years after initial OAG diagnosis among the communities studied was 56.8% to 68.8%. (Figure 2)

Figure 4: Utilization of Other Ocular Imaging Testing in the Two Years Following Incident Glaucoma Diagnosis Among Communities Throughout the United States.

Map of the United States divided into 306 hospital referral regions. Communities with larger proportions of patients receiving other ocular imaging in the 2 years after initial open-angle glaucoma diagnosis are shaded dark colors relative to other communities with lower proportions of patients undergoing other ocular imaging. Communities shaded white had fewer than 20 enrollees with newly-diagnosed open-angle glaucoma.

HRR = hospital referral region

Receipt of Either Fundus Photography or Other Ocular Imaging

The total number of enrollees that underwent ≥ 1 of either FP or OOI testing the first 2 years after initial OAG diagnosis was 39295 (69.3%). Online Figure 2, available at http://aaojournal.org shows a map with proportions of enrollees in each HRR who underwent either FP or OOI and Online Figure 3, available at http://aaojournal.org shows a turnip graph depicting variation if utilization of FP or OOI among the communities.

Receipt of OOI but No VF Testing

The total number of enrollees that underwent ≥ 1 OOI testing but no VF testing in the first 2 years after initial OAG diagnosis was 5380 (9.5%) (Online Figure 1, available at http://aaojournal.org). The mean ± SD proportion of patients receiving ≥ 1 OOI but no VF testing across HRRs was 10% ± 5%. Several communities had zero enrollees who underwent OOI but no VF testing: Wilmington, DE; Kalamazoo, MI; and Lancaster, PA. Those with the highest proportion of enrollees undergoing OOI but no VF testing included Lafayette, LA (29.9%), Dubuque, IA (29.0%); Lincoln, NE (26.1%); Pueblo, CO (24.3%); and Hackensack, NJ (23.8%). The interquartile range for receiving OOI but no VF testing among the communities studied was 7.0% to 12.0%. Online Figure 3, available at http://aaojournal.org shows a turnip graph depicting variation if utilization of OOI but no record of VF testing among the communities.

Receipt VF Testing but No OOI

The proportion of enrollees receiving ≥ 1 VF but no record of OOI in each eligible community was also determined. Online Figure 3, available at http://aaojournal.org shows a turnip graph depicting variation if utilization of VF testing but no record of OOI among the communities.

Receipt of Gonioscopy

Online Figure 4, available at http://aaojournal.org shows a map with proportions of enrollees in each HRR who underwent gonioscopy at least once in the 24 months after initial OAG diagnosis. Online Figure 3, available at http://aaojournal.org shows a turnip graph depicting variation in utilization of gonioscopy among the communities.

No Glaucoma Diagnostic Testing

The number of enrollees who underwent no glaucoma diagnostic testing of any sort in the first 2 years following initial OAG diagnosis was 7918 (14.0%). The mean ± SD of persons receiving no glaucoma testing across HRRs was 13.5% ± 4.9%. The communities with the lowest proportion of enrollees undergoing no testing were Binghamton, NY (0%); Olympia, WA (2.2%); Grand Rapids, MI (4.6%); and Lancaster, PA (4.8%). Those with the highest proportion of enrollees undergoing none of these 3 tests included Palm Springs/Rancho Mira, CA (34.7%); Hickory, NC (34.5%); Rochester, MN (28.6%); and Monroe, LA (28.6%). (Table 2) The interquartile range for receipt of no glaucoma diagnostic testing among the communities studied was 10.2% to 16.1%. (Figure 2)

Overutilizers of Glaucoma Testing

Based on the definition of overutilization we used, 13% of the HRRs had 0% of patients with overutilization. The mean % of overutilization among the HRRs was 3.7%. In 2 communities, 18.5% of patients and 20.5% of patients were flagged as overutilizers.

Variation in Glaucoma Testing Among Ophthalmologists Versus Optometrists

There were 48 HRRs that had ≥20 patients under the exclusive care of ophthalmologists and ≥20 others under exclusive care by optometrists that could be compared. After accounting for multiple comparisons, the number of communities with statistically significant differences in rates of VF, OOI, FP, and no testing were 0, 1, 9, and 0, respectively. In each of the 9 communities with significant differences in utilization of FP, those under the exclusive care of optometrists had greater utilization of this test.

Discussion

In this study of a large group of patients with newly-diagnosed OAG who were enrolled in a nationwide managed care network, we learned that patients residing in many U.S. communities undergo monitoring with glaucoma testing that is consistent with recommendations from clinical practice guidelines.6 However, there are communities that are outliers where utilization rates of glaucoma diagnostic testing are considerably higher or lower than most others. By studying variation of utilization at the community level, researchers and health policy-makers can try to identify characteristics of the patients residing in those communities or the providers practicing in those locales that may be responsible for higher or lower utilization rates relative to others. Moreover, communities with utilization rates that are substantially lower than expected based on recommended guidelines may be able to learn from how care is provided to patients in other communities where the majority of patients receive care that is consistent with practice guidelines with the goal of improving the quality of glaucoma care in communities where it is suboptimal. Likewise, it is possible to use these sorts of analyses to identify communities where there is evidence of overuse of services.

In this analysis, utilization of VF testing for patients with newly-diagnosed OAG ranged from 70% to 79% for patients residing in most of the communities studied. Given the importance of VF testing to monitor OAG and assess for disease progression,19 we identified a number of communities throughout the U.S. where the majority of patients received perimetric testing that is in accordance with current practice guidelines. While one might expect to observe rates approaching 100%, it is not surprising to see few communities with rates this high since it is known there is a small subset of patients who are unable to perform this testing due to cognitive difficulties, physical or mental impairments, co-morbid ocular diseases, limited visual acuity, or other reasons.20 Utilization of OOI was slightly lower than perimetry, ranging from 57% to 69% for most of the communities. Reasons for lower utilization of OOI may be attributable to a greater reliance upon clinical examination by the clinician instead to capture structural damage to the optic nerve or nerve fiber layer tissue, patient-related factors (e.g high myopia, media opacities, epiretinal membranes) that limit the usefulness of OOI in some patients21,22, lack of equipment to perform this testing, or other factors. Fundus photography had the lowest utilization level with rates ranging from 19% to 33% for the majority of the communities studied. While fundus photos can be better at documenting the appearance of the optic nerve compared with drawings or written descriptions of the nerve, these tests may require pupillary dilation and relatively clear media. Moreover, unlike perimetry and OOI, FP lacks quantitative results that can be compared with a normative database and subtle changes to the appearance of the nerve in sequential photographs may be difficult to detect.

While a number of communities in this study had fewer than 10% of patients monitored for OAG with OOI and no record of perimetry, there are some communities where a greater proportion of patients are undergoing OOI compared to VF testing. For example, in Lafayette, LA, the proportion of patients undergoing OOI was much higher than those undergoing VF testing (81% vs. 59%). Surveys of patients have shown that many prefer OOI over VF testing.23 These ocular imaging tests are also much quicker and easier to perform compared with perimetry. However, OOI is a structural test and VF is a functional test. OOI is currently not a replacement for VF testing. Moreover, OOI should not be used as the only method of monitoring OAG in eyes with adequate vision and the patient is capable of performing perimetry. Using OOI as the sole method of monitoring OAG can be problematic in patients with advanced disease due to a floor effect, high myopes and patients with tilted discs or extensive peripapillary atrophy, and those with comorbid retinal conditions.21,22

Patterns of utilization of the three diagnostic tests of interest varied quite a bit among the communities. In some communities utilization of glaucoma diagnostic testing was much higher than average, irrespective of the specific testing modality. For example, Lancaster, PA ranked in the top 3 among the 201 communities studied for utilization of VF tests and for FP. By comparison, other communities tended to favor one testing modality over others. For example, in Lafayette, LA, utilization of glaucoma diagnostic testing was in the top 10 for OOI but in the bottom 10 of the 201 communities for VF testing. Furthermore, there was one community where every single patient with newly-diagnosed OAG had ≥1 records of some form of glaucoma diagnostic testing in the first 2 years after initial diagnosis while in 2 other communities, over 1 in 3 patients with newly-diagnosed OAG had no record of any of these tests during the 2 years after initial OAG diagnosis.

Prior studies captured regional variation in glaucoma care. Friedman and colleagues demonstrated that when assessing the likelihood of receiving treatment for glaucoma using medications, laser trabeculoplasty, or incisional glaucoma surgery, Medicare recipients residing in the Northeast had lower rates compared with other regions of the country.24 Likewise, Jampel and colleagues found that laser trabeculoplasty was performed twice as often in some regions compared with others among Medicare enrollees.25 While the study of regional patterns of care can capture differences in care for patients who reside in different parts of the country, one of the challenges of interpreting the findings of such analyses is that there can be considerable differences in the characteristics of the patients, providers, and health system within a given region. For example, patients who reside in New York City and others who live in rural Vermont are both contributing data to the Northeast region. In the present analysis we were able to perform a more refined assessment and comparison of patterns of glaucoma care by focusing on specific communities. By doing so, researchers and policy-makers may be able to better identify some of the underlying factors driving variation in care observed as has been done for various non-ocular diseases.16,17 While we would expect to see some variation in practice patterns from one locale to another, the expectation is that the majority of patients with OAG should undergo monitoring that is in accordance with established practice guidelines.6

When interpreting these results, it is important to recognize that the glaucoma care which is being captured in a given community includes patients who are receiving their care at various different settings (academic practices, private practices) and by a variety of different eye care providers (glaucoma subspecialists, other subspecialists, comprehensive ophthalmologists, optometrists). While certain communities are known to have one or more academic medical centers within them and others lack the presence of any academic medical centers, one should not assume that all of the patients receiving care in communities with academic centers are seeking care at such centers. Our analyses seem to show that even though certain academic medical centers are known to have a reputation for expertise performing research using some of these glaucoma tests, that does not necessarily translate into greater utilization of such testing among the eye care providers who practice in these communities.

One of the rather disconcerting findings of this analysis is the identification of several communities where at least one in three patients with newly-diagnosed open-angle glaucoma have no record of receiving any glaucoma diagnostic testing in the 2 years following initial diagnosis. The communities with the highest proportions of patients with no record of any glaucoma testing included 3 on the west coast (CA, OR), 4 in southeastern states (AL, LA, MS, NC), and 3 in the upper Midwest (IN, IL, MN) while several communities with the lowest proportion of enrollees with no record of glaucoma testing were in NY and VA. Further studies are needed to determine why the rates of no glaucoma testing are so high in these communities and whether they may be attributable to patient related factors (e.g. lack of knowledge about the importance of follow-up testing), provider related factors (e.g lack of equipment, unfamiliarity with clinical practice guidelines), difficulty with access to eye care, or other factors. Given that all of these patients have health insurance, the lack of testing we are observing in these communities is unlikely to be due to that known barrier.

Defining and characterizing overutilization of care can be challenging without access to actual clinical data to consider the specific circumstances for obtaining these tests. Therefore, we one must interpret the analysis of overutilization we performed with caution. Moreover, there are certainly circumstances whereby receipt of 4 of one of these tests in a two year period would be considered completely appropriate. For example, a monocular patient with advanced glaucoma may require testing as often as every 6 months to look for disease progression. That said, it is a little surprising to see that rates of overutilization are as high as 1 in every 5 patients in one specific community. Additional research with clinical data is required to understand whether such frequent testing is appropriate and necessary.

We studied patterns of utilization of these various glaucoma diagnostic tests among patients under exclusive care of ophthalmologists and those under exclusive care of optometrists in the 48 communities that had ample numbers of patients seeking care by both provider types. We identified no communities where the proportion of patients undergoing VF testing differed between those under the care of each type of eye care provider and only one community where the proportion of patients receiving OOI differed. However, in nearly one of every 5 communities studied, optometrists had significantly higher rates of performing FP. Additional analyses using other data sources are needed to better understand the factors driving the differences we are noting and the extent by which this additional testing impacts patient outcomes.

Study Strengths and Limitations

There are several strengths of this study. Our study examined data from a large sample of patients with newly-diagnosed OAG across various communities in the U.S. In addition to geographic diversity, there was also diversity among the type of eye care providers taking care of these patients, including optometrists, comprehensive and sub-specialist ophthalmologists. Identifying patients with OAG and receipt of glaucoma diagnostic testing was captured from claims submitted by eye care providers which is more accurate than patient self-reporting.26 Lastly, the fact the all the patients in this study are part of a managed care network eliminates lack of health insurance as a barrier to care.

There are several study limitations that need to be acknowledged.27 Since this study evaluated patients with commercial health insurance, the results are not necessarily generalizable to glaucoma care among patients residing in these communities who are uninsured or possess other forms of insurance. Claims data also lacks detailed clinical information on each patient to determine the appropriateness of the receipt (or lack thereof) of a given diagnostic test. It is also difficult to capture other factors that may affect a patient’s care in claims data, such as a provider’s access to proper testing equipment, a provider’s knowledge of the AAO’s recommendations for diagnosing and monitoring OAG or logistical factors such as available support staff to administer the tests and clinic time used for the tests. There are certainly an array of potential patient-related factors that are not provided by claims data but can affect utilization.

In conclusion, while many patients with newly-diagnosed OAG are receiving care that is in conformance with clinical practice guidelines, we also note geographic variation in utilization of diagnostic testing for patients with newly-diagnosed OAG. More work is needed to determine the extent by which this variation affects patient outcomes and to understand the role that patient and provider-level factors contribute to the variation in different communities observed. Learning more about the outlier communities through qualitative research methods, such as survey or focus group studies, would be particularly useful to better understand why these disparities exist and identify ways to improve them.

Supplementary Material

Financial support:

National Eye Institute K23 Mentored Clinician Scientist Award (JDS: 1K23EY019511); Research to Prevent Blindness “Physician Scientist” Award

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no proprietary interest in any material discussed in this manuscript.

Presented, in part, at the American Glaucoma Society (Washington, DC, February 28, 2014) and National Medical Association (Honolulu, HI, August 2, 2014) meetings.

References

- 1.Vajaranant TS, Wu S, Torres M, Varma R. The changing face of primary open-angle glaucoma in the United States: demographic and geographic changes from 2011 to 2050. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;154:303–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutierrez P, Wilson MR, Johnson C, et al. Influence of glaucomatous visual field loss on health-related quality of life. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:777–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramulu PY, van Landingham SW, Massof RW, et al. Fear of falling and visual field loss from glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2012;119:1352–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen AM, van Landingham SW, Massof RW, et al. Reading ability and reading engagement in older adults with glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:5284–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee PP, Walt JG, Doyle JJ, et al. A multicenter, retrospective pilot study of resource use and costs associated with severity of disease in glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Ophthalmology Glaucoma Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2010. Available at: www.aao.org/ppp. Accessed June 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albrecht KG, Lee PP. Conformance with preferred practice patterns in caring for patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1994;101:1668–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hertzog LH, Albrecht KG, LaBree L, Lee PP. Glaucoma care and conformance with preferred practice patterns. Examination of the private, community-based ophthalmologist. Ophthalmology 1996;103:1009–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fremont AM, Lee PP, Mangione CM, et al. Patterns of care for open-angle glaucoma in managed care. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:777–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quigley HA, Friedman DS, Hahn SR. Evaluation of practice patterns for the care of open-angle glaucoma compared with claims data: the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study. Ophthalmology 2007;114:1599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Physician International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. Vols. 1 and 2. Chicago:American Medical Association Press;2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.CPT 2006: Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago, IL:American Medical Association;2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wennberg J, Gittelsohn. Small area variations in health care delivery. Science 1973;182:1102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wennberg JE, Cooper MM, eds. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing, Inc.;1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welch HG, Sharp SM, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Geographic variation in diagnosis frequency and risk of death among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA 2011;305:1113–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinstein JN, Bronner KK, Morgan TS, Wennberg JE. Trends and geographic variations in major surgery for degenerative diseases of the hip, knee, and spine. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;Suppl Variation:Var81–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Connor GT, Quinton HB, Traven ND, et al. Geographic variation in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction: the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA 1999;281:627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein JD, Talwar N, Laverne AM, et al. Trends in use of ancillary glaucoma tests for patients with open-angle glaucoma from 2001 to 2009. Ophthalmology 2012;119:748–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossetti L, Goni F, Denis P, et al. Focusing on glaucoma progression and the clinical importance of progression rate measurement: a review. Eye (Lond) 2010;24 Suppl 1:S1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heijl A, Patella VM. Essential Perimetry: The Field Analyzer Primer, 3rd edition. Dublin, CA: Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc.; 2002:1–163. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Simavli H, Que CJ, et al. Patient characteristics associated with artifacts in Spectralis optical coherence tomography imaging of the retinal nerve fiber layer in glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;159:565–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asrani S, Essaid L, Alder BD, Santiago-Turla C. Artifacts in spectral-domain optical coherence tomography measurements in glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardiner SK, Demirel S. Assessment of patient opinions of different clinical tests used in the management of glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2008;115:2127–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman DS, Nordstrom B, Mozaffari E, Quigley HA. Variations in treatment among adult-onset open-angle glaucoma patients. Ophthalmology 2005;112:1494–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jampel HD, Cassard SD, Friedman DS, et al. Trends over time and regional variations in the rate of laser trabeculoplasty in the Medicare population. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:685–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patty L, Wu C, Torres M, et al. Validity of self-reported eye disease and treatment in a population-based study: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2012;119:1725–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein JD, Lum F, Lee PP, et al. Use of health care claims data to study patients with ophthalmologic conditions. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1134–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.