Abstract

Post-transcriptional modifications in archaeal RNA are known to be phylogenetically distinct but relatively little is known of tRNA from the Methanococci, a lineage of methanogenic marine euryarchaea that grow over an unusually broad temperature range. Transfer RNAs from Methanococcus vannielii, Methanococcus maripaludis, the thermophile Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus, and hyperthermophiles Methanococcus jannaschii and Methanococcus igneus were studied to determine whether modification patterns reflect the close phylogenetic relationships inferred from small ribosomal subunit RNA sequences, and to examine modification differences associated with temperature of growth. Twenty-four modified nucleosides were characterized, including the complex tricyclic nucleoside wyosine characteristic of position 37 in tRNAPhe and known previously only in eukarya, plus two new wye family members of presently unknown structure. The hypermodified nucleoside 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine, reported previously only in bacterial tRNA at the first position of the anticodon, was identified by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry in four of the five organisms. The ribose-methylated nucleosides, 2′-O-methyladenosine, N2,2′-O-dimethylguanosine and N2,N2,2′-O-trimethylguanosine, were found only in hyperthermophile tRNA, consistent with their proposed roles in thermal stabilization of tRNA.

INTRODUCTION

Despite evolutionary constraints placed on tRNA structure to produce overall correct folding of the molecule for accurate translation of the universal genetic code, tRNA sequences and post-transcriptional modifications vary considerably and in a mutually interactive—and poorly understood—fashion across the three phylogenetic domains of life. More than 80 modified ribonucleosides have been identified in tRNAs (1); these include a small group of modifications observed in tRNAs of almost all organisms (2). In addition to this conserved core, Archaea, Bacteria and Eucarya each make phylogenetically characteristic modifications to their tRNAs following transcription.

In their biologically active forms, proteins and RNAs must adopt specific secondary and tertiary structures that may be entropically unfavorable. Consequently, at high temperatures the macromolecules are subject to denaturation, forming entropically favored, but biologically inactive and potentially deleterious products. Although proteins are frequently processed post-translationally by covalent modification, these modifications are usually not important determinants of protein stability. In contrast, modifications introduced into RNA after transcription have been shown to exert clear effects on stability (3,4). Whereas modifications in the anticodon region of tRNAs can dramatically alter codon specificity (5) and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase recognition (6), others appear to provide significant stabilization to the folded tRNA (7–9 and references therein). This effect is substantial in hyperthermophilic Archaea growing at temperatures that would otherwise denature unmodified tRNAs (4).

In the mesophilic euryarchaeon Haloferax volcanii, for which extensive tRNA sequence data are available (10,11), ∼11% of the nucleotides in each tRNA are modified. Most of these modifications consist of base or ribose methylations of nucleosides whose sequence locations are generally conserved among tRNA species. Analyses of tRNA hydrolysates from other archaea including the thermophiles Archaeoglobus fulgidus, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, Thermoplasma acidophilum, Sulfolobus solfataricus, Pyrodictium occultum, Thermoproteus neutrophilus, Pyrococcus furiosus and Pyrolobus fumarii have identified numerous modified nucleotides, including many unique to the Archaea (4,12–16).

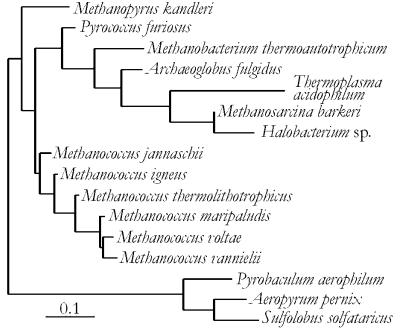

The Methanococcales comprise an order of marine Archaea that use H2, CO2 and formate (some species) to perform methanogenesis. All species are motile, irregular cocci and most grow chemolithotrophically. Despite their morphological and physiological similarities, the species are ecologically, genomically and phylogenetically diverse (Fig. 1) (17). The mesophilic Methanococci (such as Methanococcus vannielii, Methanococcus voltae and Methanococcus maripaludis) grow at ambient temperatures and were isolated from marine marshes and estuaries. Thermophilic Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus, initially isolated from geothermally heated marine sediment (18), grows optimally at 65°C. In contrast, the hyperthermophilic species Methanococcus jannaschii and Methanococcus igneus, isolated from submarine hydrothermal vents, grow optimally near 91°C (19). This broad range of optimal growth temperatures among a phylogenetically related group of organisms has made the Methanococcales an ideal model system for comparative analyses of thermal adaptation (17,20,21).

Figure 1.

Phylogeny of small subunit ribosomal RNA genes from Methanococcales and Archaea for which genomic sequence information is available. This tree was extracted from the full procaryotic tree (release 7.1) of the Ribosomal Database Project (63). The scale bar represents 0.1 nucleotide replacements per position.

An early survey of nucleosides from M.vannielii tRNAs identified significant amounts of 1-methyladenosine (m1A), 1-methylguanosine (m1G), N2-methylguanosine (m2G), N2,N2-dimethylguanosine (m22G),pseudouridine (ψ) and 2′-O-methylcytidine (Cm), with trace quantities of 2-thiocytidine (s2C) and 4-thiouridine (s4U) (12). In contrast to analyses of bacterial and eukaryotic tRNA nucleosides, no significant 7-methylguanosine (m7G) or 5-methyluridine (m5U) was detected in M.vannielii tRNAs, which supported the distinctiveness of the Archaea as a fundamental phylogenetic domain. Results described here greatly extend this inventory of modified nucleosides in the Methanococci by identifying rare and hypermodified nucleosides in five species of the genus Methanococcus. This study was designed in part to provide a close comparison of the effect of clear differences in wild-type temperature of growth among closely related archaea, to gain insights into which modifications play thermostabilizing roles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell sources and growth of cultures

Methanococcus jannaschii JAL-1T (DSM 2661) was a gift from the laboratory of R. Wolfe, University of Illinois. Methanococcus maripaludis JJT (DSM 2067) was a gift from W. Whitman, University of Georgia, Athens. Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus SN-1T (DSM 2095) was provided by B. Mukhopadhyay, University of Illinois, originally from K. O. Stetter. Methanococcus vannielii SBT (DSM 1224) culture was purchased from the Oregon Collection of Methanogens (OCM 148). Methanococcus jannaschii and M.igneus were grown anaerobically in defined minimal medium at 82–85°C under a pressurized headspace of 200 kPa H2:CO2 (80:20, v:v) (22). The medium contained 476 mM NaCl, 14 mM MgCl2, 14 mM MgSO4, 22 mM NH4Cl, 4.6 mM KCl, 0.8 mM K2HPO4, 10 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM CaCl2, 10 µM Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2, 2 µM Na2MoO4, 2 µM Na2WO4, 2 µM Na2SeO4, 4 µM resazurin, 1 mM Na2S and trace minerals (23,24). The concentrations of trace minerals were 73 µM trisodium nitriloacetic acid, 5.1 µM MnCl2, 8.4 µM CoCl2, 7.3 µM ZnCl2, 3.1 µM CuSO4 and 4.2 µM NiCl2 (25). Methanococcus maripaludis and M.vannielii were grown in the same medium at 37°C and adjusted with NaOH to pH 7.5. Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus was grown in the same medium at 65°C.

Extraction and purification of tRNAs

Total RNA was isolated by the guanidinium-acidic phenol–chloroform extraction procedure (26). Extractions were performed aerobically under normal laboratory lighting conditions. Cells (0.5 g) were suspended in 5 ml extraction buffer containing 4 M guanidine isothiocyanate, 0.5% (w:v) sodium N-laurylsarcosine, 25 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.0) and 110 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Cells were dispersed by passage through a syringe with a 22 gauge needle. Five hundred microliters of 2 M sodium acetate (pH 4.1) was added with 5 ml unbuffered phenol. This solution was mixed on a rotating shaker at 4°C for at least 8 h. One ml of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (49:1, v:v) solution was added with mixing followed by incubation on ice for 15 min. After centrifugation at 3000 g for 15 min, the aqueous phase was re-extracted with 3 ml of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (49:1). After centrifugation at 3000 g for 15 min, the aqueous phase was decanted, mixed with 2 vol of cold ethanol and stored at –20°C for at least 3 h. Precipitated total RNA was recovered by centrifugation at 17 000 g and the pellet was dried at room temperature.

DEAE–Sephadex (Pharmacia) chromatography at 4°C was used to purify tRNAs (27). A dried pellet of total RNA was resuspended in 1 ml binding buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.0). Passage through a syringe with a 22 gauge needle was used to disrupt the polysaccharide matrix that co-purified with RNA from some organisms. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 16 000 g for 5 min and the soluble fraction was applied to a syringe column containing 1.5 ml bed volume DEAE–Sephadex equilibrated in binding buffer. The column was washed with 5 vol of binding buffer followed by 5 vol of wash buffer (250 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0). Fractions were collected from an isocratic elution with 1 M NaCl and 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.0) and were then precipitated with 2 vol of cold ethanol for at least 3 h at –20°C. Precipitated tRNA was pelleted by centrifugation for 15 min at 6000 g, washed with 80% ethanol and then dried under vacuum using a SpeedVac apparatus (Savant). tRNA pellets were resuspended in distilled water and assayed spectrophotometrically by absorbance at 260 nm. Pooled fractions were analyzed by urea denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) followed by ethidium bromide staining. tRNAs were dried under vacuum using a SpeedVac apparatus (Savant).

Liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (LC/ESI-MS) of total enzymatic digests of tRNA

Unfractionated tRNAs were hydrolyzed to nucleosides using nuclease P1, venom phosphodiesterase and bacterial alkaline phosphatase as described previously (28). Analysis of nucleosides was carried out with an LC/MS system consisting of a Quattro II triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a Z-spray ion source (Micromass) and an HP 1090 liquid chromatograph with a photodiode array detector (Hewlett-Packard). Tuning of the mass spectrometer was performed with 10 mM adenosine solution. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separations of nucleosides were made by using a Luna C-18 reversed-phase column, 2.0 × 250 mm (Phenomenex), thermostatted at 40°C, with 5 mM ammonium acetate pH 5.3, and acetonitrile/water (40:60, v:v) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min without splitting (29). Source and desolvation temperatures were 130 and 350°C, respectively. All instrument control and data processing were performed with the MassLynx 3.4 software (Micromass). Procedures and interpretation of data for qualitative analysis of nucleosides in RNA hydrolysates were essentially as described in detail for a similar LC/MS system (29).

RESULTS

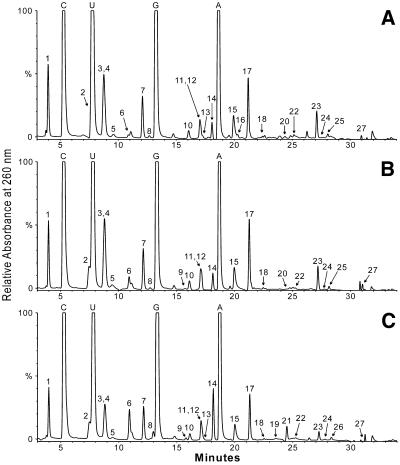

Nucleosides resulting from total tRNA digestion were separated and identified by LC/MS as shown by representative data sets from three organisms in Figure 2. Great selectivity in nucleoside assignments results from the combined use of HPLC relative retention times and ESI mass spectra, and does not require chromatographic separation of individual nucleosides (29). The dynamic range of detection of modified nucleosides using this method is ∼1 in 1000 to 1 in 10 000 total nucleosides. In addition to the four canonical nucleosides in methanococcal tRNAs, these analyses identified 26 modified nucleosides as listed in Table 1, including two new nucleosides of unknown structure, designated N422 (unknown nucleoside of molecular mass 422 Da) and demethylwyosine (imG*). Systematic names and structures for each nucleoside can be found on the world-wide web at: http://medlib.med.utah.edu/RNAmods/).

Figure 2.

LC/MS analysis of nucleosides in unfractionated tRNA isolates from Methanococci. (A) Methanococcus maripaludis, (B) M.thermolithotrophicus and (C) M.igneus. Nucleoside identities were established from mass spectra and relative retention times: 1, pseudouridine; 2, 1-methyladenosine; 3, 2-thiocytidine; 4, 1-methylpseudouridine; 5, 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine; 6, 5-methylcytidine; 7, 2′-O-methylcytidine; 8, inosine; 9, 2′-O-methyluridine; 10, 4-thiouridine; 11, 1-methylinosine; 12, 1-methylguanosine; 13, 2′-O-methylguanosine; 14, N2-methylguanosine; 15, archaeosine; 16, unknown nucleoside N422; 17, N2,N2-dimethylguanosine; 18, N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine; 19, 2′-O-methyladenosine; 20, N6-methyladenosine; 21, N2,2′-O-dimethylguanosine; 22, demethylwyosine (isomer not known); 23, N6-hydroxynorvalylcarbamoyladenosine; 24, wyosine; 25, 2-methylthio-N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine; 26, N2,N2,2′-O-trimethylguanosine; 27, N6,N6-dimethyladenosine (contaminant; see text).

Table 1. Modified nucleosides identified in tRNA from selected Methanococci.

| Growth temperature | Organism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M.maripaludis | M.vannielii | M.thermolithotrophicus | M.igneus | M.jannaschii | |

| 37°C | 37°C | 65°C | 85°C | 85°C | |

| Um, 2-O-methyluridine; m6A, N6-methyladenosine; tr, trace amount; assignment tentative. | |||||

| Nucleosidea | |||||

| ψ | + | + | + | + | + |

| m1A | + | + | + | + | + |

| s2C | + | + | + | + | |

| m1ψ | + | + | + | tr | tr |

| mnm5s2U | + | + | + | + | + |

| m5C | + | + | + | + | + |

| Cm | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ib | + | + | + | + | + |

| Um | tr | tr | + | + | |

| s4U | + | + | + | + | + |

| m1I | + | + | + | + | + |

| m1G | + | + | + | + | + |

| Gm | + | tr | + | + | + |

| m2G | + | + | + | + | + |

| G+ | + | + | + | + | + |

| N422c | + | + | + | ||

| m22G | + | + | + | + | + |

| t6A | + | + | + | + | + |

| Am | + | + | |||

| m6Ad | + | + | + | tr | + |

| m2Gm | + | + | |||

| imG*c | + | + | + | + | + |

| hn6A | + | + | + | + | + |

| imG | + | + | + | + | + |

| ms2t6A | + | + | + | tr | + |

| m22Gm | + | + | |||

aNucleosides are listed in the HPLC elution order shown in Figure 2.

bPresence of I resulting from artifactual deamination of A is possible.

cStructure unknown; see text for discussion.

dOccurrence (in part) via rearrangement of m1A is possible.

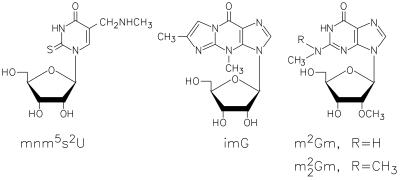

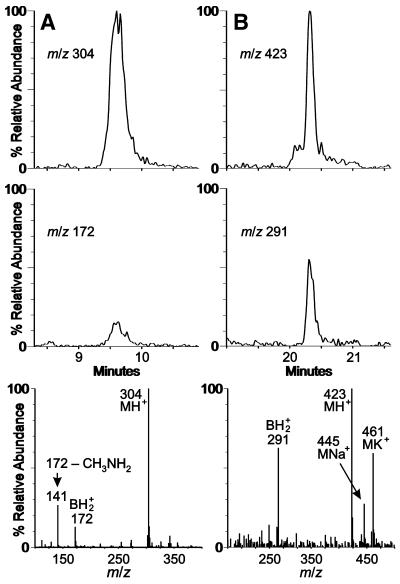

Unexpectedly, the highly modified uridine anticodon derivative 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine (mnm5s2U) (structure in Fig. 3), known previously to occur only in bacteria (2), was found in four of the five methanococcal species examined (Table 1). Rigorous identification was made as shown in Figure 4, based on relative retention times and mass spectra of the 9.4 min eluate compared with synthetic mnm5s2U (data not shown). In particular, loss of methylamine from the base ion to form m/z 141 ion is characteristic of the methylaminomethyl side chain on uridine (30). Three ribose-methylated nucleosides were observed only in tRNAs from the hyperthermophiles M.igneus and M.jannaschii: 2′-O-methyladenosine (Am), N2,2′-O-dimethylguanosine (m2Gm) and N2,N2,2′-O-trimethylguanosine (m22Gm).Unknown nucleosides N422 (Mr 422) and imG* (Mr 321) both exhibit UV absorption spectra characteristic of members of the tricyclic wyosine nucleoside family (31): UV λmax (HPLC) 233, 287 nm and UV λmax (HPLC) 228, 282 nm, respectively. The molecular mass of the nucleoside designated imG* is 14 Da lower than that of wyosine (imG) (Mr 335) originally discovered in yeast tRNA, and is consistent with an identity corresponding to a demethylwyosine in which the base contains only one methyl group. Three isomeric structures are, therefore, possible for imG* as a consequence of three potential methylation sites. The structure determinations of N422 and imG* are presently being pursued.

Figure 3.

Structures of Methanococcus tRNA nucleosides mnm5s2U, imG, m2Gm and <m22Gm>.

Figure 4.

Detection of nucleosides in M.maripaludis tRNA. (A) 5-Methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine and (B) unknown nucleoside of molecular mass 422. Ion chromatograms corresponding to MH+ (protonated molecule) and BH+2 ions (nucleoside fragment ion derived from the base moiety, B, and corresponding to the protonated free base) are shown in the top and middle panels, respectively; ESI mass spectra recorded at 9.7 and 20.3 min are shown in the bottom panels.

Among the most abundant modified nucleosides (Fig. 2) are those found in the TψCG loop [1-methylpseudouridine, (m1ψ) ψ, Cm, 1-methylinosine (m1I) and m1A], in the loop corresponding to the bacterial dihydrouridine loop [archaeosine (G+)] and in the hinge regions that join the four stems of the molecule [m2G, m22G and 5-methylcytidine (m5C)]. These modifications were identified previously in the sequences of fractionated tRNAs from H.volcanii (10). Other observed modifications include purine nucleosides at position 37 (adjacent to the anticodon triplet), and consist of m1G, N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A), 2-methylthio-N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (ms2t6A) and imG. This group may also include N6-hydroxynorvalylcarbamoyladenosine (hn6A), an adenosine N6-carbamoyl-linked norvaline derivative, which has been earlier identified in thermophilic bacteria and archaea, as well as in M.vannielii (32).

N6,N6-Dimethyladenosine (m62A) was observed in small amounts in all methanococcal RNA preparations (see peak 27 in Fig. 2), but is not a known tRNA nucleoside. It is often found in trace amounts in tRNA isolates (P.F.Crain, S.C.Pomerantz and J.A.McCloskey, unpublished observations), but is judged to arise from a fragment of 16S rRNA in which its presence is ubiquitous. This conclusion was supported by its detection by MS in an RNase T1 digest of the M.igneus tRNA preparation as the unique and highly conserved (33) 16S rRNA fragment m62Am62ACCUGp (Mr 1994.3; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Distribution and phylogenetic relationships of modified nucleosides in methanococcal tRNAs

This overall diversity of the 26 different modifications observed is relatively high, and compares with 15 in H.volcanii (10), the most extensively studied archaeon with respect to both identity and sequence locations of tRNA modifications, and ∼26 in Escherichia coli tRNA (34) and 29 in Salmonella typhimurium (35). Nucleoside mnm5s2U, which was identified in four of the five organisms studied, was unknown previously in the Archaea. In bacterial tRNA it occurs in the first position of the anticodon, in tRNAs that code for Glu and Lys (36), and is a multistep reaction product of the asuE and trmE genes (30,37). It is an important identity element at position 34 in E.coli tRNAGlu, required for efficient aminoacylation and for specific codon recognition (38,39). The striking clustering of mnm5s2U in the Methanococci suggests the possibility of horizontal gene transfer with the bacteria. However, relatively little comprehensive information exists concerning the phylogenetic distribution of mnm5s2U in bacteria, which would be useful in making inter-domain comparisons. Recent studies of mnm5s2U in the anticodon stem–loop of tRNALys using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) showed that this residue exerts considerable influence in stabilizing the stacking of the anticodon nucleotides and on the characteristic backbone U-turn at residues 33–34 (40). Much of the influence of mnm5s2U derives from the steric effect of sulfur at C-2, a powerful promoter of the C3′-endo sugar conformation (9). This thiolated nucleotide is the substrate for a selenium insertion enzyme that synthesizes the structurally related 5-methylaminomethyl-2-selenouridine in tRNAs of several bacteria and in the archaeon M.vannielii (41). Although mnm5se2U was not observed in the present study, it is readily susceptible to photochemical degradation under the conditions used for tRNA isolation.

Four of the modified nucleosides shown in Table 1 are unique to archaea: m1ψ, a T-loop surrogate for similarly shaped m5U-54 (42); archaeosine (G+), a 7-deazaguanosine derivative (43) that is conserved at position 15 and occurs widely in many tRNA isoacceptors (10,36) and the ribose-methylated species m2Gm and m22Gm, characteristic of archaeal hyperthermophiles (see discussion in following section). The tricyclic nucleoside wyosine (imG, Fig. 3) was known previously only in eukaryal tRNA, where it is restricted presumably to position 37, adjacent to the 3′ end of the anticodon in tRNAPhe, as are other members of the wye (‘Y’) family (36). The only member of the wyosine family previously known outside of eukaryal tRNA was designated mimG (42), a methylated derivative of imG, which occurs widely in the phylum Crenarchaeota (15). Its occurrence suggests that enzymes for biosynthesis of the unique tricyclic base structure (which is derived from guanine; 44) might also occur in the Euryarchaea. This possibility is borne out by the occurrence of the three ‘Y’ derivatives imG, imG* and N422 in the Methanococci, and appears to extend an earlier conclusion that post-transcriptional modifications of tRNA nucleosides in the Archaea are, in terms of structural motifs, generally more eukaryotic than bacterial (14).

Other nucleosides listed in Table 1 that contain base modifications that are shared with eukarya but not bacteria (2) are m5C, m1I, and m2G and m22G, and their ribose methylated derivatives that are unique to the archaeal thermophiles. Three nucleosides in the Methanococci that exhibit base modifications shared only with bacteria, in addition to mnm5s2U, are s2C (which is somewhat uncommon in archaea), s4U and the hypermodified norvaline derivative of A, hn6A. Thus, a total of nine tRNA nucleosides found in the Methanococci contain typically eukaryal base modifications whereas four are otherwise found only in bacteria. This tendency supports the broad conclusion from examination of full genomic sequences, that genes encoding information processing functions in Archaea (those dealing with replication, transcription and translation) most closely resemble those found in Eukarya (45,46). Along analogous lines, it will be interesting to establish whether amino acid sequences of the archaeal enzymes that produce common modification motifs (e.g. the ribosylmethyltransferases) are more similar to eukaryal homologs than to corresponding bacterial homologs, as has been studied for the complex system of genes responsible for ψ biosynthesis (47).

The diversity of structural modifications in methanococcal nucleosides characteristic of tRNA position 37 in the anticodon loop is notable: seven of 26 species listed in Table 1 (m1G, N422, t6A, ms2t6A, hn6A, imG and imG*). It has been proposed that the enzyme responsible for formation of m1G-37, tRNA(m1G37)methyltransferase, is part of a minimal set of genes required for life (48). The highly conserved extent of purine modification at position 37 has long been known (49). However, there has been heightened recent interest due to the implication of modification at this site in maintenance of correct translational reading frame (50), as well as to a greater understanding of the influence of N-37 modification on anticodon loop structure (9).

Comparison of hyperthermophilic and mesophilic tRNA modifications

In mesophiles, RNA structure is stabilized by elevated G + C content of stems, which in turn loosely correlates with optimal growth temperature (7,51), and with overall levels of post-transcriptional modification (52,53). However, in the case of thermophiles, stem G + C content essentially maximizes, and modification becomes relatively more important. The effect of modification has been determined directly by correlation between culture temperature for a given organism and increase in RNA Tm (4,54,55), or has been implied from increased levels of specific modifications, such as ribose methylation at O-2′ in tRNA (54) and rRNA (56), as a consequence of increased culture temperature.

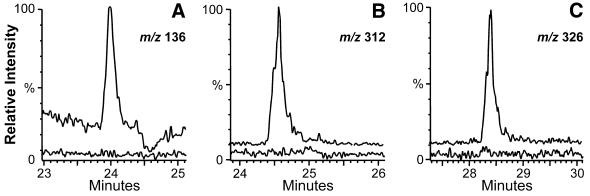

The organisms selected for the present study were chosen in part to determine whether there are differences in tRNA modification patterns among relatively closely related species that grow optimally at very different temperatures, thus minimizing differences due to phylogeny alone. This requirement is met through comparisons of tRNA from M.jannaschii and M.igneus (86–91°C) and M.maripaludis (37°C), whose phylogenetic relationships are shown in Figure 1. As seen in Figure 2 and Table 1, the modification profiles among the methanococcal tRNA nucleosides are relatively similar with regard to both identity and abundance. To some extent this observation reflects the fact that tRNA-encoding genes from the mesophilic species M.maripaludis are 86–93% identical to their homologs in the hyperthermophile M.jannaschii. The similar abundance of modified nucleosides suggests similarity of modification sites as well, and demonstrates a correlation between tRNA modification patterns and phylogenetic closeness as defined by SSU rRNA sequences. However, a clear difference is observed between the two hyperthermophiles M.igneus and M.jannaschii and the remaining organisms (including M.thermolithotrophicus) with respect to the occurrence of three nucleosides: m2Gm, m22Gm and Am. Selected ion chromatograms from the LC/MS analyses of M.igneus and M.maripaludis tRNAs are representative of the data as a whole and demonstrate complete absence of the three nucleosides in tRNA from the mesophile (Fig. 5). Another mesophilic Methanococcus, M.voltae, also lacks these three modifications (J.Konisky, P.F.Crain and J.A.McCloskey, unpublished experiments). Thermodynamically, 2′-O-methylated nucleosides favor the C3′-endo ribose pucker, which minimizes steric interferences of the base and C3′-phosphate with the ribose 2′-O-methyl group (57). In a pentofuranose ring, this conformation necessarily affects the backbone torsion angle and correlates with a low (anti-) glycosidic bond angle. Because this conformation matches that of nucleotides in an A-form double helix, the 2′-O-methyl group decreases the entropic costs of forming the duplex structure, and thereby stabilizes the base-paired form (58). Therefore, ribose methylation of specific nucleotides is a common and frequently convergent means of stabilizing the RNAs of archaeal thermophiles.

Figure 5.

Comparisons of three nucleosides that distinguish hyperthermophilic and mesophilic Methanococci. Ion chromatograms in each panel: top trace M.igneus; bottom trace M.maripaludis. (A) Base ion (<BH+2>) for detection of 2′-O-methyladenosine. (B) Molecular ion (MH+) for detection of N2,2′-O-dimethylguanosine. (C) Molecular ion (MH+) for detection of N2,N2,2′-O-trimethylguanosine.

Among the 2′-O-methylated nucleosides, m2Gm and m22Gm have thus far been identified only in hyperthermophilic archaea (15), and are likely located primarily at position 26, at the junction of the dihydrouridine and anticodon stems (see discussion in 4). In yeast tRNAPhe, m22G-26 pairs with A-44, mediating the coaxial stacking of these two stems (59,60). NMR studies of nucleosides show that, as with other 2′-O-methylations, m22Gm favors the C3′-endo-anti conformation, and that the effect is enhanced by the steric interference between the guanine N2-methyl groups and the 2′-O-methyl (61). Thus, the ribose methylations in m2Gm and m22Gm are expected to increase the thermal stability of the helical structure involved in coaxial stacking of the stems (4), although the magnitude of this effect cannot be distinguished from other stabilizing features. In the comparison of Pyrococcus furiosus cells grown at 100 versus 70°C, m22Gm and its precursor m22Gwere three times and one-third (respectively) as abundant in the high temperature cells as in the low temperature cells, consistent with ribose methylation being an active thermal adaptation (4). Similar results were observed with the thermotolerant bacterium Bacillus stearothermophilus where cells grown at 70°C had three times the 2′-O-methylated nucleosides as cells grown at 50°C (54). As pointed out by a reviewer, the relatively lower amount of m22Gm and other ribose-methylated species in M.igneus tRNA compared with that from P.furiosus (4) suggests that the ribose methylation mechanism of stabilization may be relatively less important in the present case. However, it is notable that the levels of m2Gm and m22Gmodification in M.jannaschii (chromatogram not shown) are nearly double those in M.igneus, while still appearing to be lower than those earlier found in P.furiosus.

It is intriguing that Am is common in the tRNAs of archaeal hyperthermophiles (15), but the locations of the modification are unknown. At low frequency, the amino acid acceptor stems of some eukaryotic tRNAs contain Am (36), and an S100 extract from P.furiosus was demonstrated to methylate an adenosine at position 6 in an in vitro transcript of a H.volcanii tRNA gene (62). It is possible that no recurring location will be found; with the exception of Cm at position 56, no widely conserved sites of ribose methylation are known in the Archaea. Until modification sites are identified experimentally, we will not speculate on the roles that Am might play in the stability of the tRNAs of hyperthermophiles.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authentic 5-methylaminoethyl-2-thiouridine was obtained from K. Murao, Jichi Medical School. The authors are grateful to R. S. Wolfe, W. B. Whitman, B. Mukhopadhyay and K. O. Stetter for strains used in this study. This work was supported by NIH grant GM29812 (J.A.M.), by Department of Energy grant DE-FG02-84ER13241 (J.K.), NIH grant GM22854 (D.S.), and by grant NAG5-8479 from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (G.J.O. and C.R.Woese).

REFERENCES

- 1.Rozenski J., Crain,P.F. and McCloskey,J.A. (1999) The RNA modification database-1999 update. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 196–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motorin Y. and Grosjean,H. (1998) Appendix 1: Chemical structures and classification of posttranslationally modified nucleosides in RNA. In Grosjean,H. and Benne,R. (eds), Modification and Editing of RNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 543–549.

- 3.Hall K.B., Sampson,J.R., Uhlenbeck,O.C. and Redfield,A.G. (1989) Structure of an unmodified tRNA molecule. Biochemistry, 28, 5794–5801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kowalak J.A., Dalluge, J.J., McCloskey,J.A. and Stetter,K.O. (1994) Role of posttranscriptional modification in stabilization of transfer RNA from hyperthermophiles. Biochemistry, 33, 7869–7876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curran J.F. (1998) Modified nucleosides in translation. In Grosjean,H. and Benne,R. (eds), Modification and Editing of RNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 493–516.

- 6.Giegé R., Sissler,M. and Florentz,C. (1998) Universal rules and idiosyncratic features in tRNA identity. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 5017–5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe K., Oshima,T., Iijima,K., Yamaizumi,Z. and Nishimura,S. (1980) Purification and thermal stability of several amino acid-specific tRNAs from an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus HB8. J. Biochem. (Tokyo), 87, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agris P.F. (1996) The importance of being modified: roles of modified nucleosides and Mg2+ in RNA structure and function. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 53, 79–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis D.R. (1998) Biophysical and conformational properties of modified nucleosides in RNA (nuclear magnetic resonance studies). In Grosjean,H. and Benne,R. (eds), Modification and Editing of RNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 85–102.

- 10.Gupta R. (1984) Halobacterium volcanii tRNAs. Identification of 41 tRNAs covering all amino acids, and the sequences of 33 class I tRNAs. J. Biol. Chem., 259, 9461–9471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta R. (1986) Transfer RNAs of Halobacterium volcanii: sequences of five leucine and three serine tRNAs. System. Appl. Microbiol., 7, 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Best A.N. (1978) Composition and characterization of tRNA from Methanococcus vannielii. J. Bacteriol., 133, 240–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta R. and Woese,C.R. (1980) Unusual modification patterns in the transfer ribonucleic acids of archaebacteria. Curr. Microbiol., 4, 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCloskey J.A. (1986) Nucleoside modification in archaebacterial transfer RNA. System. Appl. Microbiol., 7, 246–252. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edmonds C.G., Crain,P.F., Gupta,R., Hashizume,T., Hocart,C.H., Kowalak,J.A., Pomerantz,S.C., Stetter,K.O. and McCloskey,J.A. (1991) Posttranscriptional modification of transfer RNA in thermophilic archaea. J. Bacteriol., 173, 3138–3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCloskey J.A., Liu,X.-H., Crain,P.F., Bruenger,E., Guymon,R., Hashizume,T. and Stetter,K.O. (2000) Posttranscriptional modification of transfer RNA in the submarine hyperthermophile Pyrolobus fumarii. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. No. 44, 267–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boone D.R., Whitman,W.B. and Rouvière,P. (1993) Diversity and taxonomy of methanogens. In Ferry,J.G. (ed.), Methanogenesis. Chapman & Hall, New York, NY, pp. 35–80.

- 18.Huber H., Thomm,M., König,H., Thies,G. and Stetter,K.O. (1982) Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus, a novel thermophilic lithotrophic methanogen. Arch. Microbiol., 132, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stetter K.O. (1996) Hyperthermophilic procaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 18, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haney P.J., Badger,J.H., Buldak,G.L., Reich,C.I., Woese,C.R. and Olsen,G.J. (1999) Thermal adaptation analyzed by comparison of protein sequences from mesophilic and extremely thermophilic Methanococcus species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 3578–3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haney P.J., Stees,M. and Konisky,J. (1999) Analysis of thermal stabilizing interactions in mesophilic and thermophilic adenylate kinases from the genus Methanococcus. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 28453–28458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balch W.E., Fox,G.E., Magrum,L.J., Woese,C.R. and Wolfe,R.S. (1979) Methanogens: re-evaluation of a unique biological group. Microbiol. Rev., 43, 260–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajagopal B.S. and Daniels,L. (1986) Investigations of mercaptans, organic sulfides, and inorganic sulfur compounds as sulfur sources for the growth of methanogenic bacteria. Curr. Microbiol., 14, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukhopadhyay B., Johnson,E.F. and Wolfe,R.S. (1999) Reactor-scale cultivation of the hyperthermophilic methanarchaeon Methanococcus jannaschii to high cell densities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 65, 5059–5065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daniels L., Belay,N. and Rajagopal,B.S. (1986) Assimilatory reduction of sulfate and sulfite by methanogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 51, 703–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chomczynski P. and Sacchi,N. (1987) Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol–chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem., 162, 156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta R. (1995) Preparation of transfer RNA, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, and tRNAs specific for an amino acid from extreme halophiles. In DasSarma,S. and Fleischmann,E.M. (eds), Archaea: A Laboratory Manual (Halophiles). Cold Spring Harbor Press, Plainview, NY, pp. 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crain P.F. (1990) Preparation and enzymatic hydrolysis of RNA and DNA for mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol., 193, 782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pomerantz S.C. and McCloskey,J.A. (1990) Analysis of RNA hydrolyzates by LC/MS. Methods Enzymol., 193, 796–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagervall G., Edmonds,C.G., McCloskey,J.A. and Björk,G.R. (1987) Transfer RNA (5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine) methyltransferase from Escherichia coli K-12 has two enzymatic activities. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 8488–8495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasai H., Goto,M., Ikeda,K., Zama,M. and Mizuno,Y. (1976) Structure of wye (Yt base) and wyosine (Yt) from Torulopsis utilis phenylalanine transfer ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry, 15, 898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy D.M., Crain,P.F., Edmonds,C.G., Gupta,R., Hashizume,T., Stetter,K.O., Widdel,F. and McCloskey,J.A. (1992) Structure determination of two new amino acid-containing derivatives of adenosine from tRNA of thermophilic bacteria and archaea. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 5607–5614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Knippenberg P.H., Van Kimmenade,J.M. and Heus,H.A. (1984) Phylogeny of the conserved 3′ terminal structure of the RNA of small ribosomal subunits. Nucleic Acids Res., 12, 2595–2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gehrke C.W. and Kuo,K.C. (1990) Ribonucleoside analysis by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography. In Gehrke,C.W. and Kuo,K.C. (eds), Chromatography and Identification of Nucleosides, Part A, Vol. 45A. Journal of Chromatography Library, Elsevier, New York, NY, pp. A3–A64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Buck M., Connick,M. and Ames,B.N. (1983) Complete analysis of tRNA-modified nucleosides by high performance liquid chromatography: the 29 modified nucleosides of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli tRNA. Anal. Biochem., 129, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sprinzl M., Horn,C., Brown,M., Ioudovitch,A. and Steinberg,S. (1998) Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan M.A., Cannon,J.F., Webb,F.H. and Bock,R.M. (1985) Antisuppressor mutation in Escherichia coli defective in biosynthesis of 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine. J. Bacteriol., 161, 368–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakamoto K., Kawai,G., Watanabe,S., Niimi,T., Hayashi,N., Muto,Y., Watanabe,K., Satoh,T., Sekine,M. and Yokoyama,S. (1996) NMR studies of the effects of the 5′-phosphate group on conformational properties of 5-methylaminomethyluridine found in the first position of the anticodon of Escherichia coli tRNA(Arg)4. Biochemistry, 35, 6533–6538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madore E., Florentz,C., Giegé,R., Sekine,S., Yokoyama,S. and Lapointe,J. (1999) Effect of modified nucleotides on Escherichia coli tRNAGlu structure and on its aminoacylation by glutamyl-tRNA synthetase. Predominant and distinct roles of the mnm5 and s2 modifications of U34. Eur. J. Biochem., 266, 1128–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundaram M., Crain,P.F. and Davis,D.R. (2000) Synthesis and characterization of the native anticodon domain of E.coli tRNALys: simultaneous incorporation of modified nucleosides mnm5s2U, t6A, and pseudouridine using phosphoramidite chemistry. J. Org. Chem., 65, 5609–5614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittwer A.J., Tsai,L., Ching,W.M. and Stadtman,T.C. (1984) Identification and synthesis of a naturally occurring selenonucleoside in bacterial tRNAs: 5-[(methylamino)methyl]-2-selenouridine. Biochemistry, 23, 4650–4655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCloskey J.A., Crain,P.F., Edmonds,C.G., Gupta,R., Hashizume,T., Phillipson,D.W. and Stetter,K.O. (1987) Structure determination of a new fluorescent tricyclic nucleoside from archaebacterial tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 683–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gregson J.M., Crain,P.F., Edmonds,C.G., Gupta,R., Hashizume,T., Phillipson,D.W. and McCloskey,J.A. (1993) Structure of the archaeal transfer RNA nucleoside G*-15 (2-amino-4,7-dihydro-4-oxo-7-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-5-carboximidamide (archaeosine)). J. Biol. Chem., 268, 10076–10086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia G.A. and Goodenough-Lashua,D.M. (1998) Mechanisms of RNA-modifying and -editing enzymes. In Grosjean,H. and Benne,R. (eds), Modification and Editing of RNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 135–168.

- 45.Olsen G.J. and Woese,C.R. (1997) Archaeal genomics: an overview. Cell, 89, 991–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doolittle W.F. and Logsdon,J.M.,Jr (1998) Archaeal genomics: do archaea have a mixed heritage? Curr. Biol., 8, R209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watanabe Y. and Gray,M.W. (2000) Evolutionary appearance of genes encoding proteins associated with box H/ACA snoRNAs: Cbf5p in Euglena gracilis, an early diverging eukaryote, and candidate Gar1p and Nop10p homologs in archaebacteria. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 2342–2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Björk G.R., Jacobsson,K., Nilsson,K., Johansson,M.J., Bystrom,A.S. and Persson,O.P. (2001) A primordial tRNA modification required for the evolution of life? EMBO J., 20, 231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Auffinger P. and Westhof,E. (1998) Location and distribution of modified nucleotides in tRNA. In Grosjean,H. and Benne,R. (eds), Modification and Editing of RNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 569–576.

- 50.Björk G.R., Durand,J.M., Hagervall,T.G., Leipuviene,R., Lundgren,H.K., Nilsson,K., Chen,P., Qian,Q. and Urbonavicius,J. (1999) Transfer RNA modification: influence on translational frameshifting and metabolism. FEBS Lett., 452, 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galtier N. and Lobry,J.R. (1997) Relationships between genomic G + C content, RNA secondary structures, and optimal growth temperature in prokaryotes. J. Mol. Evol., 44, 632–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sampson J.R. and Uhlenbeck,O.C. (1988) Biochemical and physical characterization of an unmodified yeast phenylalanine transfer RNA transcribed in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 1033–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Derrick W.B. and Horowitz,J. (1993) Probing structural differences between native and in vitro transcribed Escherichia coli valine transfer RNA: evidence for stable base modification-dependent conformers. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 4948–4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agris P.F., Koh,P. and Söll,D. (1973) The effect of growth temperature on the in vivo ribose methylation of Bacillus stearothermophilus. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 154, 277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watanabe K., Shinma,M. and Oshima,T. (1976) Heat-induced stability of tRNA from an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 72, 1137–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noon K.R., Bruenger,E. and McCloskey,J.A. (1998) Posttranscriptional modifications in 16S and 23S rRNAs of the archaeal hyperthermophile Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Bacteriol., 180, 2883–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kawai G., Yamamoto,Y., Kamimura,T., Masegi,T., Sekine,M., Hata,T., Iimori,T., Watanabe,T., Miyazawa,T. and Yokoyama,S. (1992) Conformational rigidity of specific pyrimidine residues in tRNA arises from posttranscriptional modifications that enhance steric interaction between the base and the 2′-hydroxyl group. Biochemistry, 31, 1040–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yokoyama S., Inagaki,F. and Miyazawa,T. (1981) Advanced nuclear magnetic resonance lanthanide probe analyses of short-range conformational interrelations controlling ribonucleic acid structures. Biochemistry, 20, 2981–2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim S.H., Suddath,F.L., Quigley,G.J., McPherson,A., Sussman,J.L., Wang,A.H., Seeman,N.C. and Rich,A. (1974) Three-dimensional tertiary structure of yeast phenylalanine transfer RNA. Science, 185, 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robertus J.D., Ladner,J.E., Finch,J.T., Rhodes,D., Brown,R.S., Clark,B.F.C. and Klug,A. (1974) Structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA at 3 Å resolution. Nature, 250, 546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawai G., Ue,H., Yasuda,M., Sakamoto,K., Hashizume,T., McCloskey,J.A., Miyazawa,T. and Yokoyama,S. (1991) Relation between functions and conformational characteristics of modified nucleosides found in tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser., 49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Constantinesco F., Motorin,Y. and Grosjean,H. (1999) Transfer RNA modification enzymes from Pyrococcus furiosus: detection of the enzymatic activities in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 1308–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maidak B.L., Cole,J.R., Lilburn,T.G., Parker,C.T.,Jr, Saxman,P.R., Stredwick,J.M., Garrity,G.M., Li,B., Olsen,G.J., Pramanik,S., Schmidt,T.M. and Tiedje,J.M. (2000) The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) continues. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 173–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]