Abstract

Purpose

The proposed pathological mechanism for scar formation is controversial, and increased attention has been paid to the fatty acids (FAs) in the formation of pathological scars. Notably, FAs are known to be important in inflammation and mechanotransduction, which is closely related to scar formation. Therefore, it is necessary to clarify the roles of FA in scar formation.

Methods

Hypertrophic scar and keloid formed for more than a year and without other treatment, as well as normal skin samples were obtained from patients who underwent plastic surgery. Finally, keloids (n = 10), hypertrophic scars (n = 10), and normal skin samples (n = 10) were collected under informed consent. Primary dermal fibroblasts were isolated and cultured. The amount and variety of FAs were detected by lipid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Immunohistochemistry, real-time PCR, and western blotting were used to verify the expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 (SREBP1) and fatty acid synthase (FASN) in the samples and their fibroblasts. Student's t-test, ANOVA, and orthogonal partial least square discriminant analysis were performed for statistical analysis (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

Results

Compared with full-thickness normal skin, there were 27 differential FAs in keloids and 15 differential FAs in hypertrophic scars (∗p < 0.05 and variable influence on projection >1.0). The expression of SREBP1 and FASN was lower in pathological scars both at mRNA and protein levels (all ∗p < 0.05). However, the mRNA levels of SREBP1 (∗∗∗p = 0.0002) and FASN (∗∗∗p = 0.0021) in keloid-derived fibroblasts were higher than that in normal skin fibroblasts (NFBs), while the expression in hypertrophic scar-derived fibroblasts was lower than that in NFBs (both ∗p < 0.05). Whereas there was no significant difference in FASN protein expression between keloid-derived fibroblasts and NFBs (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

FAs involved in pathological scars are abnormally changed in scar formation. Thus, fatty acid-derived inflammation and de novo synthesis pathway of FA may play a key role in the formation of pathological scars.

Keywords: Hypertrophic scars, Keloids, Fatty acids, Fibroblasts

Introduction

Pathological scars, which mainly consist of hypertrophic scars and keloids, are large areas of proliferating fibroblasts accompanied by disordered apoptosis, excessive deposition of collagen and glycoproteins in the extracellular matrix.1,2 The proposed pathological mechanism of scar formation is controversial, and studies have focused mainly on genetic,3 vascular,4 immunological, neurogenic,5 and nutritional factors.6 Moreover, increasing attention has been paid to the effect of lipids in the formation of pathological scars, and fatty acid (FA) is an important class of functional lipids.

The lipid profiles in pathological scars showed constitutional changes. From a nutritional perspective, keloids contained decreased levels of membrane essential fatty acid (EFA),7 linoleic acid8 and increased arachidonic acid (AA),9 less abundant of cholesterol esters, wax esters, triglycerides, and ceramides compared to normal skin.10 Notably, lipids are related to various pathological mechanisms, including inflammation, secondary messengers and mechanotransduction.11 Moreover, the potential biological effects of FAs on wound healing have been investigated, and treatments related to FAs in scars have been studied.12,13 However, the altered FAs involved in pathological scars compared to normal skin remain unclear.

FAs include saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). PUFAs are EFAs that cannot be synthesized in vivo, but the components of their metabolism are important inflammation-related factors. So, the metabolism and dietary intake of PUFAs may influence the formation of pathological scars. Additionally, some kinds of FAs could be synthesized in vivo. In the process of FA synthesis in the human body, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP1) and fatty acid synthase (FASN) are the key enzymes of endogenous syntrophic fatty acid synthesis.

The role of FAs plays in pathological scars is worthy of researching. As a result, we conducted this study to (1) determine whether the FA content in pathological scars differs from that in normal skins, (2) explore whether the expression of SREBP1 and FASN in pathological scars and their dermal fibroblasts is abnormal, and (3) speculate on the relationship between the processes of FA synthesis and metabolism and the pathological scars.

Methods

Sample information

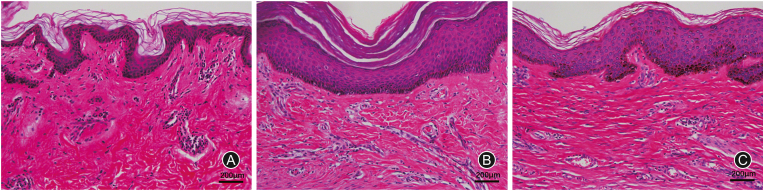

The investigative protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, and informed consent has been obtained from each patient. Hypertrophic scar and keloid formed for more than a year and normal skin samples were obtained from patients who underwent plastic surgery (Department of Burn and Plastic Surgery, the Fourth Medical Centre, Chinese PLA General Hospital and Plastic Surgery Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College). Patients with less than 1 year of scar formation or with other treatments will be excluded. Patients with underlying disease would also be excluded. Ultimately, a total of 30 samples were collected, and hematoxylin and eosin staining (Fig. 1) was used to determine the sample type.

Fig. 1.

The hematoxylin and eosin staining of samples. (A) Normal skin; (B) Keloid skin; (C) Hypertrophic scar skin.

Fibroblast culture

Dermal tissues were washed 3 times with phosphate buffer saline and then minced into pieces (about 1 mm). Pieces were explanted in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco BRL, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Solarbio, China) at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide. The medium was changed every 2 days. At 7–10 days after the primary culture, it was confirmed that the cells had proliferated on the dishes from the edge of the explanted tissue. Then, the cells were passaged 1–2 times per week.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections of 4 μm serial sections were subjected to gradual deparaffinization. Antigen retrieval was carried out by immersing the slides in citrate buffer and incubating for 10 min at 100°C. Sections were rinsed in water and blocked in 10% normal goat IgG for 20 min. The samples were incubated in primary mouse monoclonal anti-SREBP1 and anti-FASN antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, US) diluted 1:200 in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed in phosphate buffer saline, followed by 20 min incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide in dH2O. Biotin-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (ZSGQ-BIO, China) was added for 20 min at room temperature. DAB reagent (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) was applied for 2–3 min, and hematoxylin (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) was applied for 2 min to restain nuclei.

Real-time PCR (RT-PCR)

A TRIzol reagent kit (Invitrogen, USA) was used for RNA extraction. The isolated RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using the Prime Script RT Reagent kit (Takara, China). Primers were obtained from Takara Biotechnology. Quantitative PCR was performed using the CFX96™ real-time system (Bio-Rad, USA), using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara, China) in a 12 μl PCR solution. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1. The results were normalized against the mean Ct values for GAPDH using the ΔCt method as follows: ΔCt = Ct gene of interest - mean Ct (GAPDH). The fold increase was calculated as 2−ΔΔCt.

Table 1.

The sequences for primers.

| Primer | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| SREBP1 | CCTAAGTCTGCGCACTGCTGTC | CCTAAGTCTGCGCACTGCTGTC |

| FASN | AGCACAGACGAGAGCACCTTTG | CCATGCAGCTCAGCAGGTCTA |

| GAPDH | GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC | TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA |

SREBP1: sterol regulatory element binding proteins 1; FASN: fatty acid synthase; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Western blot analysis

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to lyse cells for 10 min on ice. Cells were then centrifuged at 14,000×g at 4°C to remove cell debris. Samples containing 50 μg of protein were loaded onto a 5%–10% polyacrylamide gel, separated by electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The markers were tested by exposing the membranes to primary antibodies (Santa, USA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Epizyme, China) antibody was used as the secondary antibody. Proteins were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence system using a Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+ (Bio-Rad, USA). Blots were detected using ImageLab™ software, version 5.1 (Bio-Rad).

Targeted metabolic profiling of FAs

Each sample was mixed with 10 prechilled zirconium oxide beads and 20 μL deionized water. After homogenized for 3 min, 150 μL methanol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) containing internal standard was added to extract the metabolites. Supernatant was transferred to the 96-well plate after centrifuged at 18,000×g for 20 min; and 20 μL derivative reagents were added to each well, which was sealed, and derivatization at 30°C for 60 min. Then, 400 μL of an ice-cold 50% methanol solution was added to the samples after evaporated for 2 h. The plate was stored at −20°C for 20 min, followed by centrifugation at 4000×g and 4°C for 30 min. A 135 μL volume of supernatant was transferred to a new plate with 15 μL internal standards. Finally, the plate was sealed for lipid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software 8.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student's t-test at a significance level of 5% were used to determine statistically significant differences. The LC-MS data were analyzed by orthogonal partial least square discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) using QuanMET software (Ver. 2.0, Metabo-Profile, Shanghai, China) (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). The values are shown in the figures.

Results

Targeted metabolic profiling of FAs

In total, 52 FAs, including 8 short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), were detected. Results of OPLS-DA showed 27 differential FAs in keloids (Table 2) and 15 differential FAs in hypertrophic scars (Table 3) compared to full-thickness normal skin (p < 0.05 and variable influence on projection >1.0), respectively. Among the altered SCFAs, the expression of butyric acid, isobutyric acid, valeric acid and succinic acid were the highest in hypertrophic scars, followed by normal skins, and significantly decreased in keloids. Of the other 44 FAs, we found that differential expression was in 22 FAs in keloids compared with normal skins. However, only 13 differential FAs were identified in hypertrophic scars.

Table 2.

Differential fatty acids of the full-thickness skin between keloid and normal skin.

| Metabolite | VIP | p value | Expressiona |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acids | |||

| Ethylmethylacetic acid | 2.15 | <0.0001 | Down |

| 2-Hydroxy-3-methylbutyric acid | 1.74 | 0.0004 | Up |

| Formic acid | 1.68 | 0.0008 | Down |

| Docosapentaenoic acid | 1.64 | 0.0011 | Up |

| Arachidonic acid | 1.64 | 0.0011 | Up |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid | 1.57 | 0.0021 | Up |

| 2-Methylvaleric acid | 1.54 | 0.0026 | Down |

| 5-Dodecenoic acid | 1.46 | 0.0050 | Down |

| 8,11,14-Eicosatrienoic acid | 1.43 | 0.0061 | Up |

| Adrenic acid | 1.43 | 0.0064 | Up |

| Itaconic acid | 1.34 | 0.0118 | Down |

| Myristoleic acid | 1.33 | 0.0123 | Down |

| 10Z-Nonadecenoic acid | 1.32 | 0.0132 | Up |

| Methylglutaric acid | 1.32 | 0.0132 | Down |

| DPAn-6 | 1.28 | 0.0166 | Up |

| Docosahexaenoic acid | 1.28 | 0.0166 | Up |

| Alpha-Linolenic acid | 1.26 | 0.0185 | Down |

| Isocaproic acid | 1.24 | 0.0212 | Down |

| Heptanoic acid | 1.17 | 0.0307 | Down |

| 12-Hydroxystearic acid | 1.02 | 0.0644 | Down |

| Dodecanoic acid | 1.02 | 0.0653 | Down |

| Sebacic acid | 1.00 | 0.0697 | Down |

| Short-chain fatty acids | |||

| Isobutyric acid | 2.05 | <0.0001 | Down |

| Butyric acid | 1.62 | 0.0014 | Down |

| Valeric acid | 1.48 | 0.0045 | Down |

| Isovaleric acid | 1.43 | 0.0065 | Down |

| Malonic acid | 1.37 | 0.0094 | Down |

VIP: variable influence on projection.

“down” means the expression of this fatty acid in keloid was lower than that in normal skin; on the contrary, “up” means this fatty acid in keloid was higher expression.

Table 3.

Differential fatty acids of the full thickness between hypertrophic scar and normal skin.

| Metabolite | VIP | p value | Expressiona |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acids | |||

| Ethylmethylacetic acid | 2.41 | 0.0001 | Down |

| Adrenic acid | 2.09 | 0.0019 | Up |

| Methylmalonic acid | 2.07 | 0.0021 | Up |

| Docosapentaenoic acid | 1.93 | 0.0048 | Up |

| Arachidonic acid | 1.90 | 0.0058 | Up |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid | 1.78 | 0.0108 | Up |

| Myristoleic acid | 1.72 | 0.0149 | Down |

| 2-Hydroxy-3-methylbutyric acid | 1.61 | 0.0238 | Up |

| Myristic acid | 1.58 | 0.0271 | Down |

| DPAn-6 | 1.55 | 0.0306 | Up |

| Palmitoleic acid | 1.55 | 0.0311 | Down |

| 12-Tridecenoic acid | 1.50 | 0.0372 | Down |

| Tridecanoic acid | 1.47 | 0.0413 | Down |

| Short-chain fatty acids | |||

| Succinic acid | 1.81 | 0.0096 | Up |

| Acetic acid | 1.74 | 0.0134 | Down |

VIP: variable influence on projection.

“down” means the expression of this fatty acid in hypertrophic scar was lower than that in normal skin; on the contrary, “up” means this fatty acid in hypertrophic scar was higher expression.

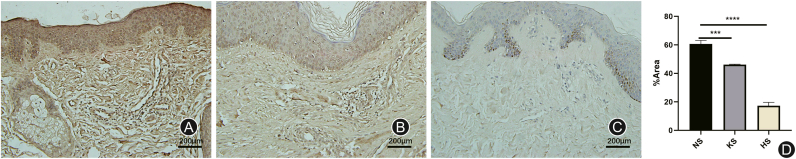

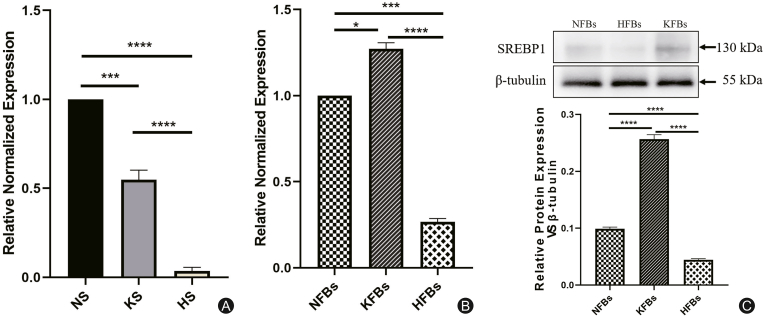

The expression of SREBP1 in hypertrophic scars and keloids

In the whole layer tissue, the results of immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2) and RT-PCR (Fig. 3A) showed that the mRNA expression of SREBP1 was lower in hypertrophic scars and keloids than in normal tissues. However, at the level of dermal fibroblasts, the expression of SREBP1 in KFBs was higher than that in NFBs, while its expression in hypertrophic scar-derived fibroblasts (HFBs) was lower than that in NFBs both at the mRNA and protein level (Figs. 3B and C).

Fig. 2.

The images and results of immunohistochemistry with SREBP1. (A) Normal skin (NS); (B) Keloid skin (KS); (C) Hypertrophic scar skin (HS). The expression of SREBP1 is lower in hypertrophic scars (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001) and keloids (∗∗∗p = 0.0007) than in normal tissues.

Fig. 3.

The expression of SREBP1 in keloid, hypertrophic scars, and their dermal fibroblasts. (A) The expression of SREBP1 was lower in hypertrophic scars (HS) (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001) and keloids (KS) (∗∗∗p = 0.0001) than in normal tissues (NS). (B) At the level of dermal fibroblasts, the results of RT-PCR showed that the expression of SREBP1 in KFBs (∗p < 0.05) was higher than that in NFBs, while its expression in HFBs was lower than that in NFBs (∗∗∗p < 0.001). (C) The relative protein expression of SREBP1 in KFBs was higher than that in NFBs (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001), while its expression in HFBs was lower than that in NFBs (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

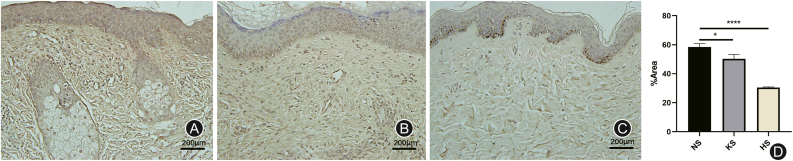

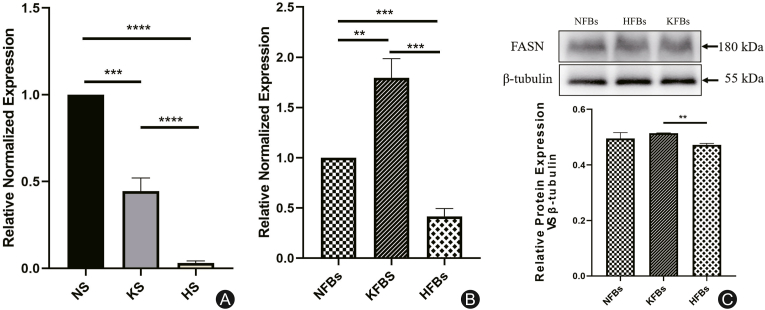

The expression of FASN in hypertrophic scars and keloids

As shown in immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4) and RT-PCR (Fig. 5A) of full-thickness skin tissues, the expression of FASN was downregulated in hypertrophic scars and keloids. However, the mRNA expression of FASN in KFBs was higher than that in NFBs, but decreased in HFBs (Fig. 5B). In terms of protein expression, the fibroblasts showed a slightly different trend: there was no significant difference in FASN protein expression between KFBs and NFBs (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 4.

The images and results of immunohistochemistry with FASN. (A) Normal skin (NS); (B) Keloid skin (KS); (C) Hypertrophic scar skin (HS). The expression of FASN was lower in hypertrophic scars (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001) and keloids (∗∗∗p < 0.001) than in normal tissues.

Fig. 5.

The expression of FASN in keloid (KS), hypertrophic scars (HS), and their dermal fibroblasts (NS). (A) As shown in full-thickness skin tissues, FASN expression was at lower levels in hypertrophic scars (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001) and keloids (∗∗∗p = 0.0001) compared with that in normal skin. (B) The mRNA expression of FASN in KFBs (∗∗∗p = 0.0002) was higher than that in NFBs, while its expression in HFBs was decreased (∗∗∗p < 0.001). (C) There was no significant difference in protein expression of FASN between KFBs and NFB (p>0.05), but it was downregulated in HFBs (∗p < 0.05).

From the above results, we found that the expression of SREBP1 and FASN in hypertrophic scars and keloids was lower than that in normal skin in terms of full-thickness skin, which is consistent with the trend in long-chain SFA in pathological scars. However, at the level of dermal fibroblasts, the mRNA expression of SREBP1 and FASN in KFBs was higher than that of NFBs, while was lower in HFBs. The difference between full-thickness skin and dermal fibroblasts may be attributed to expression in the epidermis.

Discussion

The changed FAs in pathological scars and inflammation

Pathological scars are thought to be closely related to the occurrence of inflammation. Prostaglandins (PGs) are key components of inflammatory processes. Furthermore, PGs have been described as critical components in wound healing, tissue regeneration and fibrosis,14 such as PGE2,15 PGD2 and 15d-PGJ216.

In addition, PGs are the main components of PUFA metabolism. Omega-6 and omega-3 FAs are the two major families of PUFAs. Excessive production of AA-derived eicosanoids, which including PGs, leukotrienes, and thromboxanes, are associated with the regulation and mediation of inflammatory processes.17,18 Cells involved in the inflammatory response are typically rich in the omega-6 fatty acid AA, but the AA contents can be altered through the administration of EPA and DHA. In our study, most PUFAs, such as AA, DPA, EPA, and DPAn-6, were more highly expressed in keloids and hypertrophic scars.

Moreover, SCFAs are also related to the regulation of inflammation, especially butyrate and propionate. A lack of SCFAs produces inflammatory mediators by inhibiting the activation of mast cells.19 In this study, a lack of SCFAs, such as butyric acid, was observed in keloids. This would influence the apoptosis, proliferation and differentiation of keloid-derived fibroblasts and cause collagen deposition. An in vitro study20 on keloid treatment in which butyrate was applied to keloid-derived fibroblasts for coculture verified this speculation. The results show that butyrate inhibits fibroblast proliferation, type III collagen expression, and PGE2 production but upregulates the expression of cyclooxygenase 1.

The FAs de novo synthesis and fast-proliferating KFBs

In addition to dietary intake, SFAs are FAs that could be synthesized by human body. FASN and SREBP1 are key factors in this process. Pathological scars are tumor-like tissue, and dermal-derived fibroblasts are fast-proliferating cells. Increased lipid production is one of the important metabolic markers of rapidly proliferating cells. Most normal cells obtain lots of FAs directly from the circulation to meet their metabolic and material synthetic needs. In tumor cells, which are rapidly proliferating cells, more than 90% of FAs, so-called de novo synthesis endogenous FAs, are obtained through self-synthesis.21 This process is completely independent of the normal pathway of FA synthesis.

Moreover, SREBP-1 and FASN are closely related to the abnormal FA synthesis of rapidly proliferating cells. SREBP-1 is an important transcription factor that regulates the synthesis of sterols and lipids in the de novo synthesis pathway and directly regulates the expression of key enzymes. FASN, which provides the energy needed for the survival of proliferating cells, is a critical enzyme in the abnormal metabolism of endogenous syntrophic saturated fatty acid.22,23 The activity of FASN was found to be increased in a variety of rapidly proliferating cells, and this increase was closely related to poor prognosis.24,25 KFBs are also abnormally active and proliferative cells, and the expression of SREBP and FASN in the de novo synthesis of FAs would be a direction for the mechanism of keloids.

The mechanism of pathological scar formation is generally focused on dermis-derived fibroblasts. According to the results, at the level of dermal fibroblasts, the mRNA expression of SREBP1 and FASN in KFBs was higher than that of NFBs, while was lower in HFBs. Then we speculate that the de novo FA synthesis pathway is abnormal in pathological scars and this process is active in keloid fibroblasts but inactive in hypertrophic scar fibroblasts.

The PUFAs diet and scar formation

Nutrition and treatment related to the FAs on pathological scars are also concerned by doctors. Given that some PUFAs exhibit different levels in pathological scars, we believe that EFA-related intake and dietary habits may affect pathological scars formation. Omega-6 PUFAs derived from linoleic acid and omega-3 PUFAs derived from Alpha-Linolenic acid are EFAs involved in the body's functions. LA and Alpha-Linolenic acid must be wholly derived from the diet.26 A retrospective questionnaire study performed in South Africa by Louw et al.27 found that individuals with keloids consumed higher levels of LA and AA, and the consumption of omega-6 PUFAs was lower than the amount recommended by the joint World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization (5%–8% of the PUFAs28). Based on these findings, some scholars have carried out several studies on the treatment of pathological scars with FA-related substances and achieved certain results.12,13 Furthermore, an in vitro study found that DHA has antifibrogenic effects on keloid fibroblasts.29

In conclusions, the synthesis and metabolism of FAs are important parts of regulation of the body. The type and quantity of FAs in hypertrophic scars and keloids are different from normal skin, and in the process of endogenous FA synthesis, the expression of SREBP1 and FASN in pathological scar-derived dermal fibroblasts is abnormal. Thus, FA synthesis and metabolism would be critical directions in pathological scar formation, and in-depth study would be done for the prevention and treatment of pathological scars.

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81772085). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical statement

The investigative protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (2019KY013-HS001), and informed consent has been obtained from each patient.

Declarations of competing interest

All authors declared no competing interest.

Author contributions

Jin-Xiu Yang, Le-Ren He and Min-Liang Chen contributed to the conception and design of the study, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. Jin-Xiu Yang participated in metabonomic by lipid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Jin-Xiu Yang and Shi-Yi Li performed the cells isolation and culture, PCR, immunohistochemistry, HE staining and Western blot. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Medical Association.

Contributor Information

Min-Liang Chen, Email: chenml@sohu.com.

Le-Ren He, Email: heleren@sina.com.

References

- 1.Meshkinpour A., Ghasri P., Pope K., et al. Treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloids with a radiofrequency device: a study of collagen effects. Laser Surg Med. 2005;37:343–349. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo S., Benathan M., Raffoul W., et al. Abnormal balance between proliferation and apoptotic cell death in fibroblasts derived from keloid lesions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:87–96. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200101000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robles D.T., Berg D. Abnormal wound healing: keloids. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le A.D., Zhang Q., Wu Y., et al. Elevated vascular endothelial growth factor in keloids: relevance to tissue fibrosis. Cells Tissues Organs. 2004;176:87–94. doi: 10.1159/000075030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akaishi S., Ogawa R., Hyakusoku H. Keloid and hypertrophic scar: neurogenic inflammation hypotheses. Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira A.C., Hochman B., Furtado F., et al. Keloids: a new challenge for nutrition. Nutr Rev. 2010;68:409–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louw L. Keloids in rural black South Africans. Part 3: a lipid model for the prevention and treatment of keloid formations. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;63:255–262. doi: 10.1054/plef.2000.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakespeare P.G., Strange R.E. Linoleic acid in hypertrophic scars. Burns Incl Therm Inj. 1982;9:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(82)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomura T., Terashi H., Omori M., et al. Lipid analysis of normal dermis and hypertrophic scars. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:833–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tachi M., Iwamori M. Mass spectrometric characterization of cholesterol esters and wax esters in epidermis of fetal, adult and keloidal human skin. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:318–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preiss J., Loomis C.R., Bishop W.R., et al. Quantitative measurement of sn-1,2-diacylglycerols present in platelets, hepatocytes, and ras- and sis-transformed normal rat kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8597–8600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishak W., Katas H., Yuen N.P., et al. Topical application of omega-3-, omega-6-, and omega-9-rich oil emulsions for cutaneous wound healing in rats. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2019;9:418–433. doi: 10.1007/s13346-018-0522-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olaitan P.B., Chen I.P., Norris J.E., et al. Inhibitory activities of omega-3 fatty acids and traditional african remedies on keloid fibroblasts. Wounds. 2011;23:97–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y.J., Kanaji N., Wang X.Q., et al. Prostaglandin E2 switches from a stimulator to an inhibitor of cell migration after epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Prostag Other Lipid Mediat. 2015;116–117:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao J., Shu B., Chen L., et al. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits collagen synthesis in dermal fibroblasts and prevents hypertrophic scar formation in vivo. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:604–610. doi: 10.1111/exd.13014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantel A., Newsome A., Thekkudan T., et al. The role of aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3)-mediated prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) metabolism in keloids. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:38–43. doi: 10.1111/exd.12854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marion-Letellier R., Savoye G., Ghosh S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation. IUBMB Life. 2015;67:659–667. doi: 10.1002/iub.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalinski P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J Immunol. 2012;188:21–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C.C., Wu H., Lin F.H., et al. Sodium butyrate enhances intestinal integrity, inhibits mast cell activation, inflammatory mediator production and JNK signaling pathway in weaned pigs. Innate Immun. 2018;24:40–46. doi: 10.1177/1753425917741970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torii K., Maeshige N., Aoyama-Ishikawa M., et al. Combination therapy with butyrate and docosahexaenoic acid for keloid fibrogenesis: an in vitro study. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:184–190. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mashima T., Seimiya H., Tsuruo T. De novo fatty-acid synthesis and related pathways as molecular targets for cancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1369–1372. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sankaranarayanapillai M., Zhang N., Baggerly K.A., et al. Metabolic shifts induced by fatty acid synthase inhibitor orlistat in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells provide novel pharmacodynamic biomarkers for positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Mol Imag Biol. 2013;15:136–147. doi: 10.1007/s11307-012-0587-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang L., Wang H., Li J., et al. Up-regulated FASN expression promotes transcoelomic metastasis of ovarian cancer cell through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:11539–11554. doi: 10.3390/ijms150711539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogino S., Nosho K., Meyerhardt J.A., et al. Cohort study of fatty acid synthase expression and patient survival in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5713–5720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen P.L., Ma J., Chavarro J.E., et al. Fatty acid synthase polymorphisms, tumor expression, body mass index, prostate cancer risk, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3958–3964. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li D., Sinclair A., Wilson A., et al. Effect of dietary alpha-linolenic acid on thrombotic risk factors in vegetarian men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:872–882. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louw L., Dannhauser A. Keloids in rural black South Africans. Part 2: dietary fatty acid intake and total phospholipid fatty acid profile in the blood of keloid patients. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;63:247–253. doi: 10.1054/plef.2000.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishida C., Uauy R., Kumanyika S., et al. The joint WHO/FAO expert consultation on diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: process, product and policy implications. Publ Health Nutr. 2004;7:245–250. doi: 10.1079/phn2003592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torii K., Maeshige N., Aoyama-Ishikawa M., et al. Combination therapy with butyrate and docosahexaenoic acid for keloid fibrogenesis: an in vitro study. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:184–190. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]