Abstract

Acetaminophen (APAP) is one of the major causes of drug-induced acute liver injury, and ethanol may aggravate APAP-induced liver injury. The problem of ethanol- and APAP-induced liver injury becomes increasingly prominent, but the mechanism of ethanol- and APAP-induced liver injury remains ambiguous. p38γ is one of the four isoforms of P38 mitogen activated protein kinases, that contributes to inflammation in different diseases. In this study we investigated the role of p38γ in ethanol- and APAP-induced liver injury. Liver injury was induced in male C57BL/6 J mice by giving liquid diet containing 5% ethanol (v/v) for 10 days, followed by gavage of ethanol (25% (v/v), 6 g/kg) once or injecting APAP (200 mg/kg, ip), or combined the both treatments. We showed that ethanol significantly aggravated APAP-induced liver injury in C57BL/6 J mice. Moreover, the expression level of p38γ was up-regulated in the liver of ethanol-, APAP- and ethanol+APAP-treated mice. Knockdown of p38γ markedly attenuated liver injury, inflammation, and steatosis in ethanol+APAP-treated mice. Liver sections of p38γ-knockdown mice displayed lower levels of Oil Red O stained dots and small leaky shapes. AML-12 cells were exposed to APAP (5 mM), ethanol (100 mM) or combined treatments. We showed that P38γ was markedly increased in ethanol+APAP-treated AML-12 cells, whereas knockdown of p38γ significantly inhibited inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in ethanol+APAP-treated AML-12 cells. Furthermore, we revealed that p38γ could combine with Dlg1, a member of membrane-associated guanylate kinase family. Deletion of p38γ up-regulated the expression level of Dlg1 in ethanol+APAP-treated AML-12 cells. In summary, our results suggest that p38γ functions as an important regulator in ethanol- and APAP-induced liver injury through modulation of Dlg1.

Keywords: fatty liver, steatohepatitis, acetaminophen, P38γ, ethanol, Dlg1

Introduction

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the most frequent and most serious complications of chronic alcohol intake. Its clinical manifestations include steatosis, fibrosis, alcoholic hepatitis (AH), liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1, 2]. The probability of hepatic steatosis (fatty liver) in alcoholic patients is more than 90%, and ~20–40% of them will develop more severe ALD [3]. In recent years, the occurrence of ALD has become increasingly common, causing increasing harm to humans [2, 4]. Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a severe clinical challenge worldwide, with more than 50% of cases of acute liver failure in the United States [5]. Acetaminophen (APAP) is a dose-dependent hepatotoxin that can cause intrinsic DILI [6]. The hepatotoxicity of APAP is caused by its toxic metabolite n-acetyl group. It is mediated by NAPQI, which is produced by hepatic cytochrome P450 and detoxified by binding with hepatic glutathione (GSH) [7, 8]. Of note, with the development of the social economy, the problem of DILI with pre-existing ALD is becoming serious. Zimmerman et al. found that the liver may be more sensitive to drug toxicity under the influence of alcohol [9]. In addition, a case report shows that long-term drinking can enhance the hepatotoxicity of low-dose APAP, and repeated therapeutic dosing will lead to severe liver injury, especially in chronic alcoholic abusers [10, 11]. However, at present, the mechanism of EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury is not completely clear. Therefore, it is of practical significance to find markers that can assist in differential diagnosis.

P38 are stress-activated serine/threonine kinases that sense a variety of cardiac pathologies, which are closely related to the production of ROS and consist of 4 isoforms: α, β, γ, and δ [12]. Biochemical evidence suggests that individual subtypes have specific roles and are classified as stress-activated kinases [13]. Among the four isoforms, p38γ contributed to inflammation in different diseases. Bárbara et al. confirmed that p38γ could reedit liver metabolism by regulating neutrophil infiltration [14], and p38γ is critical for regulating the cell cycle and affecting liver tumorigenesis [15]. Xu et al. found that alcohol could activate the Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ErbB2)/p38γ signaling pathway [16]. Overall, it is highly possible that p38γ could play a vital role in lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury.

Biopsies have shown that p38γ is highly expressed in human HCC tissue and may become a therapeutic target for HCC treatment [15]. In addition, p38γ is highly expressed in the livers of NAFLD patients, and mice lacking p38γ are resistant to diet-induced fatty liver, glucose intolerance and hepatic triglyceride accumulation [14]. P38γ has been confirmed to be involved in inflammation in different diseases [17], and the expression level of p38γ is necessary for the prolongation of nascent TNF-α protein in macrophages [18]. However, knowledge gaps still exist, the potential molecular mechanism, and the applicability of phosphatase as a therapeutic target for the disease. These findings demonstrated the role of p38γ in liver lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in the EtOH+APAP-induced mouse group, suggesting that p38γ has a potential role in the treatment of ALD and will bring new potential ideas and potential targets for future treatment.

Materials and methods

Reagent

F4/80-, Fasn-, Acox1-, and Dlg1-specific antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). P38γ antibody (CST, Danvers, MA) and Abclonal (ABc, Wuhan, China). P-p38γ antibody was acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SCB, Beijing, China). Anti-albumin was purchased from Proteintech (Pro, Beijing, China). Anti-NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4), anti-inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), anti-IL-6, anti-TNF-α, anti-IL-1β, anti-SREBP-1 and anti-PPAR-α were purchased from Bioss Biotechnology (Bioss, Beijing, China). 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCF) and dihydroethidium (DHE) were obtained from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Jiangsu Province, China). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione (GSH) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) commercial kits were obtained from Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Bioengineering (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). Respective ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) were used to detect IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Animal experiments

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 J mice were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Anhui Medical University. Mice were randomly separated into a normal group and an experimental group [19]. Animal experiments were approved by the ethics committee and approved by the animal Committee and use Committee of Anhui Medical University (No.: llsc20150348). Importantly, the modeling process of EtOH-fed mice lasted 16 days, including three processes: fluid diet adaptation stage (5 days), modeling (10 days), gavage (once) and then specimen (1 day) (EtOH feeding group). Of note, mice fed EtOH were randomly given an LD liquid diet containing 5% EtOH (5% v/v) for 10 days and then given EtOH by gavage according to body weight. Control mice were given the same amount of maltodextrin by gavage (Pair group). In addition, EtOH+APAP-fed mice were given corresponding EtOH gavage according to body weight, and APAP was intraperitoneally injected at 200 mg/kg. In addition, overnight fasted mice were only intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected 200 mg/kg APAP dissolved in normal saline. Mice were sacrificed at 9 h after APAP or/and EtOH injection, and livers and blood were collected. Adeno-associated virus was obtained from Hanbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The mice were slowly injected with AAV9 packaged p38γ knockdown (KD) plasmid through tail vein injection to construct p38γ KD mice [20].

Cell culture

AML-12 cells (noncancerous) are stored in the School of Pharmacy, Anhui Medical University. The battery is kept at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described in the literature [21]. Of note, the primary antibodies included p38γ (1:1000), p-p38γ (1:1000), Dlg1 (1:600), TNF-α (1:800), IL-6 (1:800), IL-1β (1:800), PPAR-α (1:500), SREBP-1 (1:500), Fasn (1:1000), and Acox (1:1000). ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) was used to quantitatively analyze the results.

Total RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the frozen liver and cultured cells. After reverse transcription, real-time PCR was implemented by utilizing Bio–Rad iQ SYBR Green Supermix with Opticon 2 (Bio–Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fold changes in the mRNA levels of target genes were related to the invariant control GAPDH.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

We extracted liver tissue from mice and fixed it with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h (5 μm) [22], followed by photographing the tissue using an optical microscope [22].

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Albumin and p38γ expression levels were detected in liver tissue. After fixation, the slide was blocked with goat serum before incubation with primary antibodies (anti-albumin and anti-p38γ) overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber. For in vitro experiments, AML-12 cells were cultured overnight with antibodies detecting p38γ and Dlg1 (1:200) followed by appropriate secondary antibodies for 2 h. Finally, the cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. All images were taken by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

Co-IP was analyzed in AML-12 cells by using the Co-IP Pull-Down Kit (RiboBio, Guangzhou). The cells were lysed in precooling lysis buffer. Protein A beads were incubated with anti-p38γ for 4 h and then cultured with total protein lysate overnight. The specific experimental steps were as follows in the kit instructions.

Biochemical analyses

Blood was collected, and serum was separated by centrifugation (4 °C, 3000 r/min, 10 min). The expression levels of serum ALT, AST, MDA, SOD, and GSH were determined according to the requirements of the instructions provided in reagent kits.

Hepatocyte isolation

Hepatocyte isolation was performed as described in the literature [23].

Statistical analyses

All experiments were repeated at least three times. The differences between groups were compared by one-way ANOVA. The data were analyzed as the mean ± standard error at least three times independently by Tukey’s multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism Version 7.

Results

EtOH aggravated APAP-induced liver injury in C57BL/6 J mice

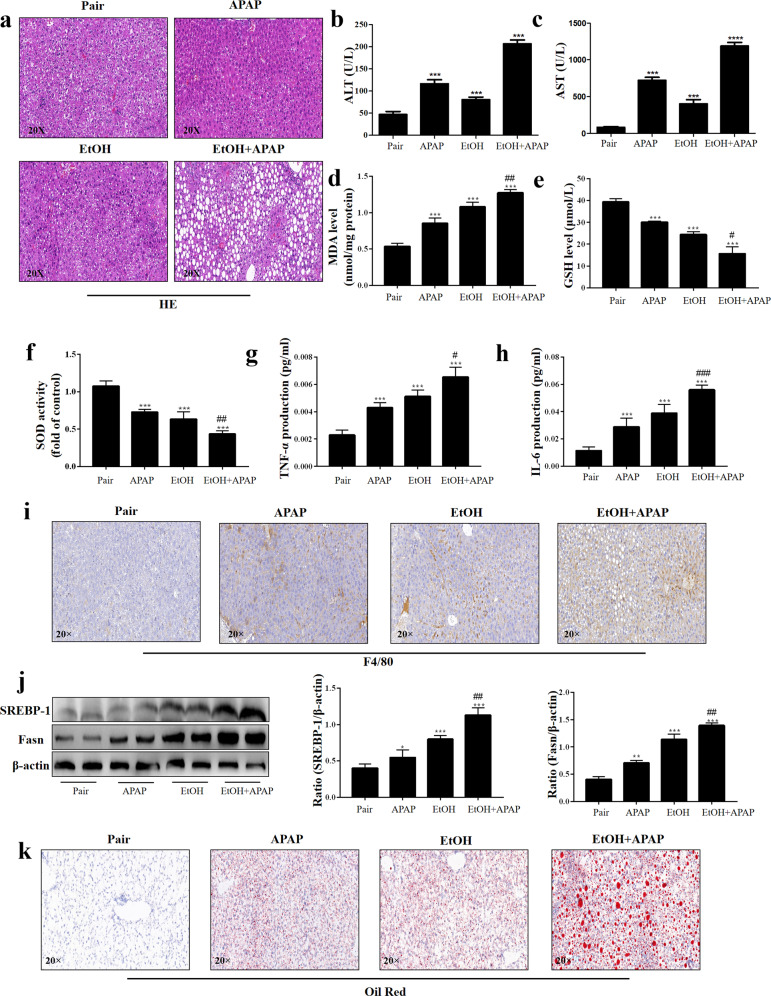

To investigate the effect of EtOH in APAP-induced C57BL/6 J mice, histopathological studies were performed. As shown in Fig. 1a, there were marked microsteatosis and macrosteatosis, as well as hepatocyte ballooning, in EtOH+APAP-induced mice (EtOH+APAP group) compared with EtOH-induced mice (EtOH group) and APAP-induced mice (APAP group). Serum expression levels of ALT and AST were markedly increased in the EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 1b, c). In addition, compared with the control mice (Pair group), MDA expression level increased significantly (Fig. 1d), GSH and SOD expression levels (Fig. 1e, f) decreased in liver tissues of the EtOH group, while APAP significantly aggravated the oxidative stress. A comparison of liver inflammation in the EtOH group and EtOH+APAP group is presented in Fig. 1G-I. We used ELISA to detect the expression of TNF-α and IL-6. Compared with the Pair and EtOH groups, TNF-α and IL-6 expression levels were significantly increased in the EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 1g, h). Moreover, the IHC analysis results showed significantly enhanced F4/80+ positive signals in the EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 1i). Furthermore, we found that the SREBP-1 expression level was markedly increased in the EtOH+APAP group compared with the EtOH group, while the MDA level was significantly increased (Fig. 1j). Oil Red O staining also showed more severe hepatic steatosis and lipid accumulation in the EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 1k). In conclusion, EtOH aggravated APAP-induced liver injury in C57BL/6 J mice.

Fig. 1. EtOH aggravated APAP-induced liver injury in C57BL/6 J mice.

a Liver tissues stained with HE. b, c Serum ALT and AST assay. d–f Levels of MDA, GSH, and SOD in serum; (g-h). Levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in serum. i IHC and quantitative analysis of F4/80. j The expression levels of SREBP-1 and Fasn detected by real-time PCR and Western blotting. k Oil Red O staining in mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs Pair group. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs APAP or EtOH alone group.

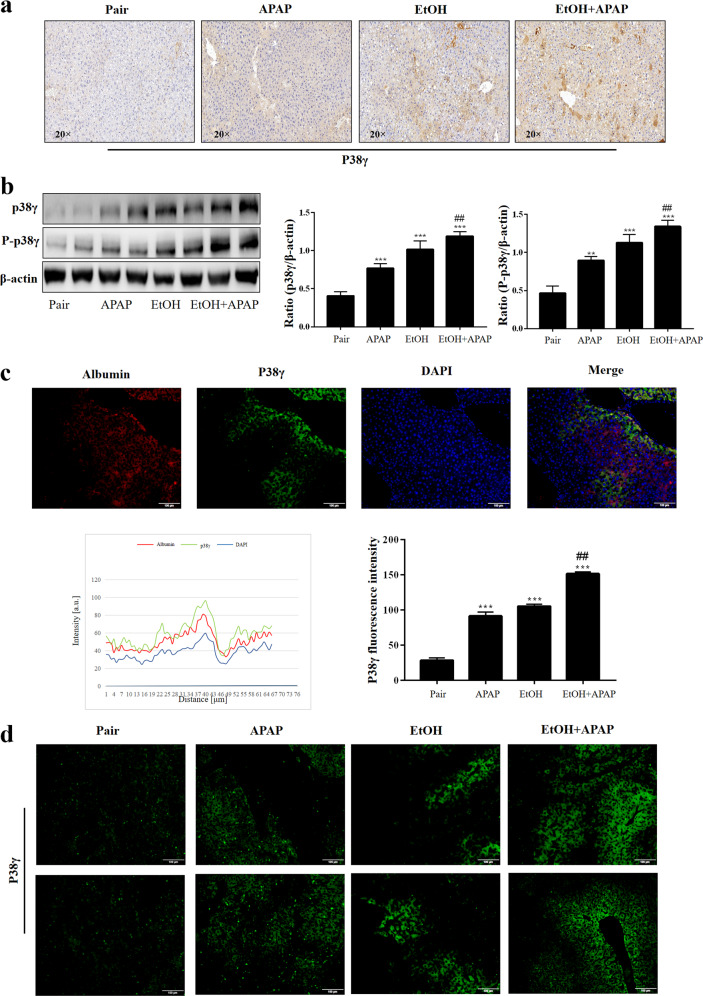

P38γ was elevated in EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury in C57BL/6 J mice

P38γ was upregulated in the patients with HCC [15]. Herein, we detected the expression level of hepatic p38γ in the EtOH+APAP group. The p38γ expression level was significantly upregulated in the EtOH+APAP group, as shown by IHC (Fig. 2a). In addition, the results of Western blotting in hepatic lysates showed that p38γ and p-p38γ expression levels were upregulated in the EtOH+APAP group compared with the EtOH group (Fig. 2b). Notably, immunofluorescence double staining showed that there was a typical colocalization of p38 and hepatocyte albumin immunoreactivity in liver tissue (Fig. 2c). In addition, the biopsies from the EtOH+APAP group showed that p38γ had the strongest fluorescence intensity compared to the pair group and EtOH group (Fig. 2d). These findings ascertained elevated hepatic p38γ upon EtOH+APAP challenge and suggested that abnormal p38γ expression levels might be relevant to EtOH-induced hepatic dysfunction.

Fig. 2. P38γ was elevated in EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury in C57BL/6 J mice.

a IHC analysis of p38γ. b The expression level of p38γ and p-p38γ was detected by real-time PCR and Western blotting. c Albumin and p38γ colocalized in the liver by double immunofluorescence. d Immunofluorescence analysis of p38γ. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Pair group. ##P < 0.01 vs APAP or EtOH alone group.

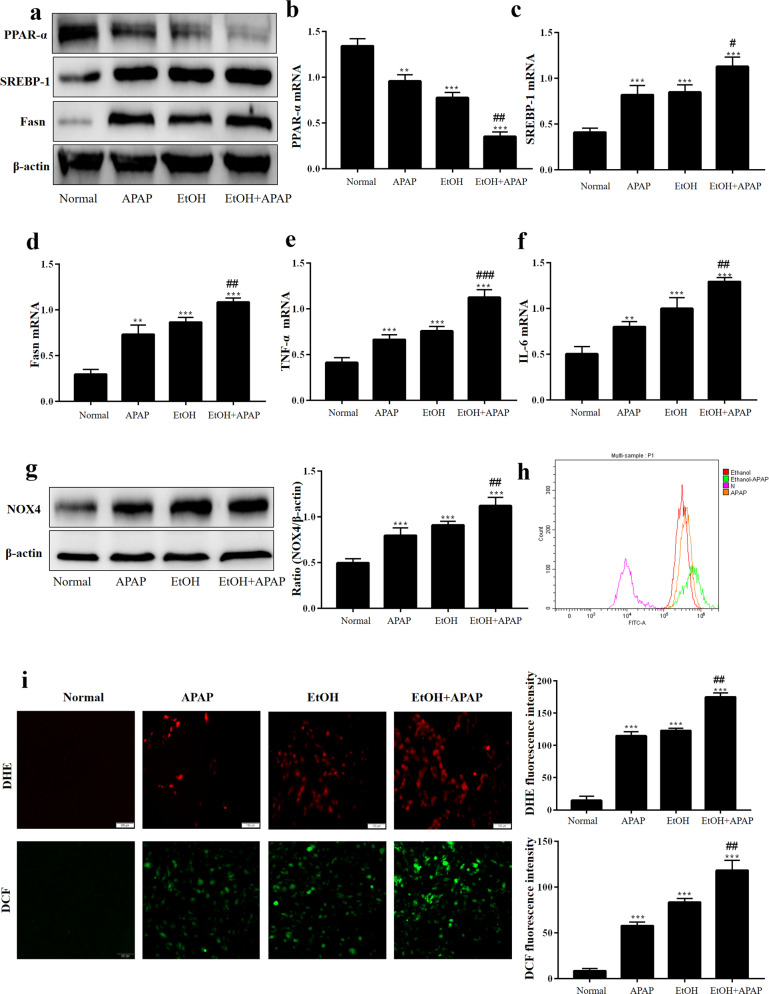

EtOH enhanced inflammation secretion, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in response to APAP

To establish an in vitro model, AML-12 cells were induced with APAP and EtOH to observe the influence of EtOH on APAP-induced inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress. As shown in Fig. 3a–d, EtOH-induced (100 mM EtOH) lower PPAR-α but higher SREBP-1 and Fasn expression levels in APAP-treated (5 mM APAP) AML-12 cells. In addition, we assessed the effects of EtOH+APAP (5 mM APAP and 100 mM EtOH) on the inflammatory response of AML-12 cells. The results showed that the expression levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were notably upregulated in the EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 3e, f). In addition, the protein expression level of NOX4 was also upregulated in the EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 3g). DCF and DHE staining results also demonstrated that the production of ROS increased in the EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 3h, i). Overall, it was suggested that EtOH could more seriously induce inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in APAP-induced AML-12 cells.

Fig. 3. EtOH enhanced inflammation secretion, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in response to APAP.

a–d Real-time PCR and Western blotting detected the levels of PPAR-α, SREBP-1 (the cleaved nuclear (~68 kDa) forms of SREBP-1) and Fasn. e, f Real-time PCR detect the level of TNF-α and IL-6. g Western blotting detected the level of NOX-4. h, i The production of ROS detected by DCF and DHE assay. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Normal group. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs APAP or EtOH alone group.

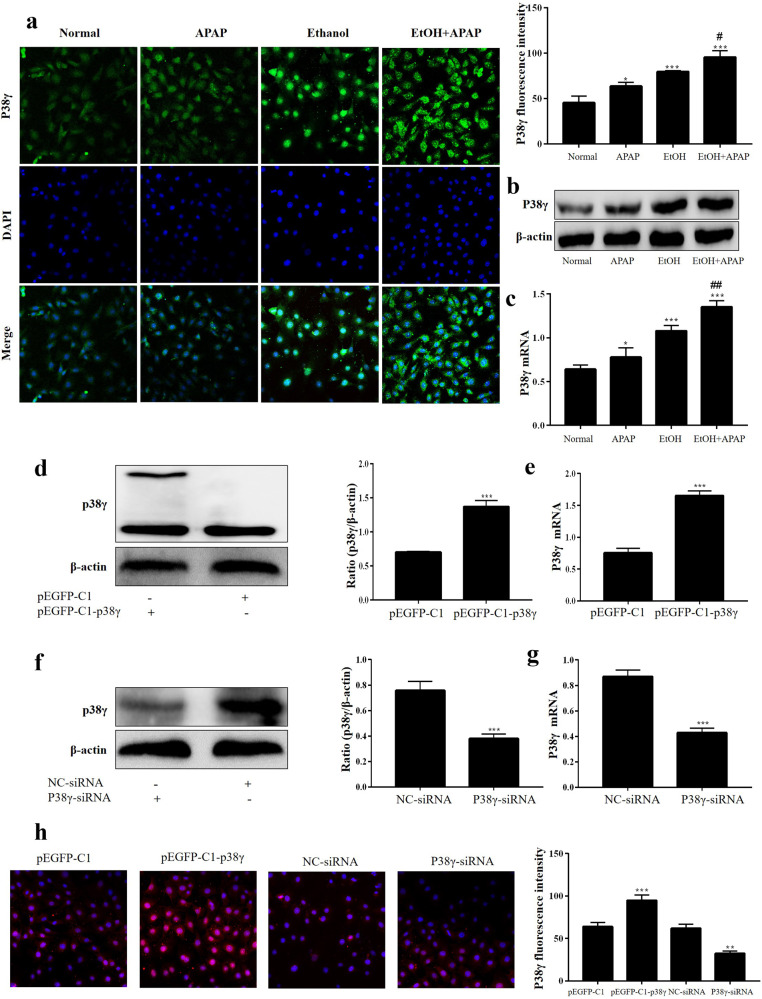

P38γ was also increased in EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells

To further define the expression level of p38γ in EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells, we used IF, Western blotting and real-time PCR analysis to detect the expression level of p38γ. Compared with the EtOH group, the p38γ expression level was obviously upregulated in the EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 4a–c). Next, AML-12 cells were transfected with pEGFP-C1-p38γ, pEGFP-C1, p38γ-siRNA and NC-siRNA, and related results confirmed that pEGFP-C1-p38γ and p38γ-siRNA were successfully transferred into AML-12 cells (Fig. 4d–h). Therefore, the effect of p38γ on inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells could be detected.

Fig. 4. P38γ was also increased in EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells.

a–c Immunofluorescence, Western blotting and real-time PCR were used to detect the p38γ expression level. d, e. Real-time PCR and Western blotting of the level of p38γ after transfection with pEGFP-C1-p38γ. f, g. Real-time PCR and Western blotting of the level of p38γ after transfection with p38γ-siRNA. h Immunofluorescence analysis of p38γ after transfection with pEGFP-C1-p38γ and p38γ-siRNA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Normal group. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs APAP or EtOH alone group.

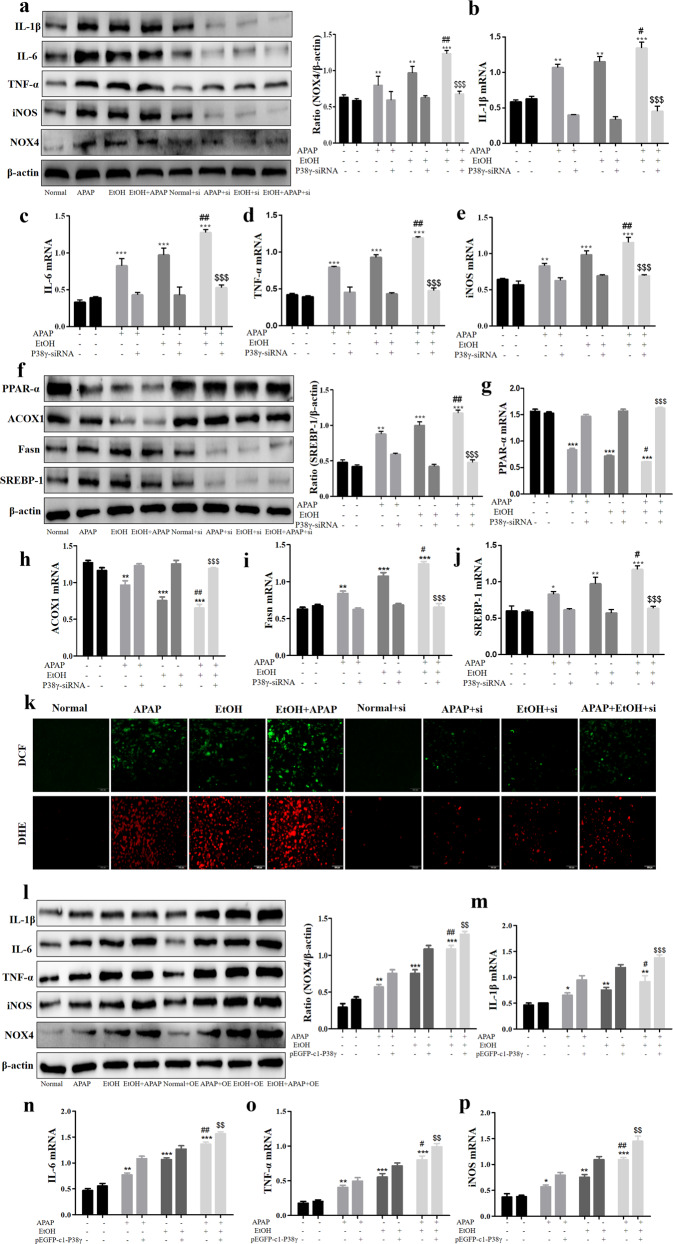

Interference of P38γ mitigated inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells

After successful construction of the p38γ-siRNA cell model, we further detected the effects of p38γ on inflammatory reactions, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells. First, we assessed the expression levels of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, iNOS and NOX4). These cytokines exhibited a trend of lower induction in p38γ-siRNA-transfected AML-12 cells (Fig. 5a–e). In addition, we tested the expression levels of hepatic steatosis-associated proteins. As shown in Fig. 5f, the expression levels of PPAR-α and ACOX1 were increased, and the expression levels of lipogenesis-associated proteins, including SREBP-1 and Fasn, were inhibited in p38γ-siRNA-transfected AML-12 cells. The results of real-time PCR also showed the same effects (Fig. 5g–j). These findings suggested that p38γ could inhibit EtOH+APAP-induced lipogenesis and facilitate fatty acid oxidation. Consistently, the disruption of p38γ suppressed oxidative stress levels (Fig. 5k). Next, we further examined the role of p38γ overexpression in EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells. As shown in Fig. 5l–p, these cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, iNOS and NOX4) exhibited a trend of higher expression levels in pEGFP-C1-p38γ-transfected AML-12 cells. In addition, the expression levels of PPAR-α and ACOX1 were decreased, and the expression levels of lipogenesis-associated proteins, including SREBP-1 and Fasn, were promoted in pEGFP-C1-p38γ-transfected AML-12 cells. The results of real-time PCR also showed the same effects (Fig. 5q-u). Consistently, p38γ could stimulate the levels of oxidative stress (Fig. 5v). Overall, these data suggested that inhibition of p38γ alleviated the sensitivity of AML-12 cells to EtOH+APAP-induced injury.

Fig. 5. P38γ interference mitigated inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH + APAP-induced AML-12 cells.

a–e The expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, iNOS and NOX4 detected by Western blotting and real-time PCR. f–j The expression levels of PPAR-α, ACOX1, Fasn and SREBP-1 (the cleaved nuclear (~68 kDa) forms of SREBP-1) detected by Western blotting and real-time PCR. k The production of ROS detected by DCF and DHE assay. l-p. The expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, iNOS, and NOX4 detected by Western blotting and real-time PCR after over-expression of p38γ. q–u The expression levels of PPAR-α, ACOX1, Fasn, and SREBP-1 detected by Western blotting and real-time PCR after over-expression of p38γ. v. The production of ROS detected by DCF and DHE assay after over-expression of p38γ. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Normal. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs EtOH or APAP alone. $$P < 0.01, $$$P < 0.001 vs EtOH+APAP group.

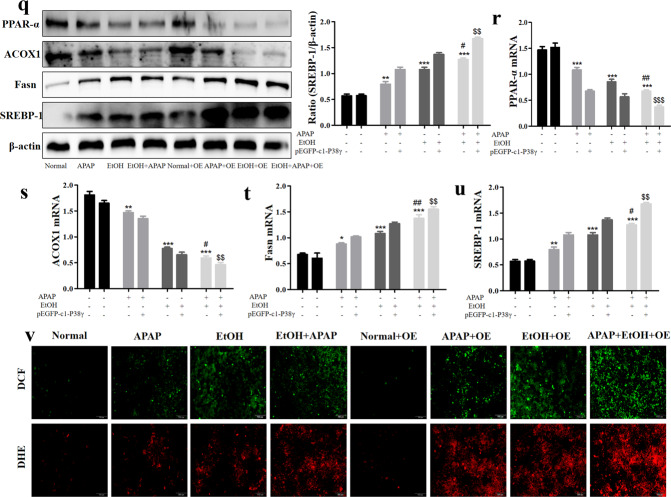

P38γ interacted with Dlg1 in AML-12 cells

IHC staining showed that the Dlg1 expression level was obviously reduced in the livers of the ALD group compared with the pair group (Fig. 6a). Similarly, the GEO database and Western blotting analysis results showed lower levels of Dlg1 in ALD patients and the EtOH+APAP group (Figs. 6b, c). Interestingly, we found that p38γ could interact with Dlg1 in the STING database (Fig. 6d). Next, the Co-IP analysis results showed that p38γ bound to Dlg1 in EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells (Fig. 6e), and the IF results also confirmed this (Fig. 6f). Furthermore, p38γ-siRNA upregulated the expression level of Dlg1 in EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells (Fig. 6g, h).

Fig. 6. P38γ interacted with Dlg1 in AML-12 cells.

a–c IHC and Western blotting analysis of Dlg1 in mice. d, e P38γ could interact with Dlg1 in AML-12 cells, as demonstrated by a co-IP assay. with Dlg1. f Double immunofluorescence displayed the typical colocalization of p38γ and Dlg1 in AML-12 cells. g, h Western blotting and real-time PCR of the levels of Dlg1 after transfection with p38γ-siRNA in AML-12 cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Normal group. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs EtOH or APAP alone group. $$P < 0.01, $$$P < 0.001 vs EtOH+APAP group.

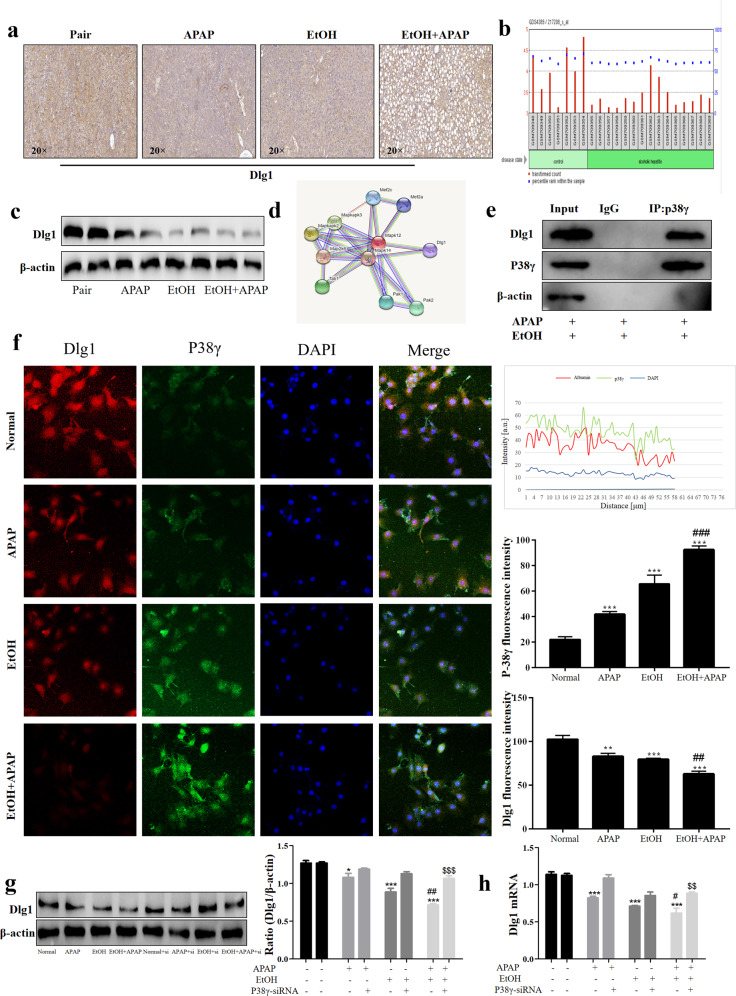

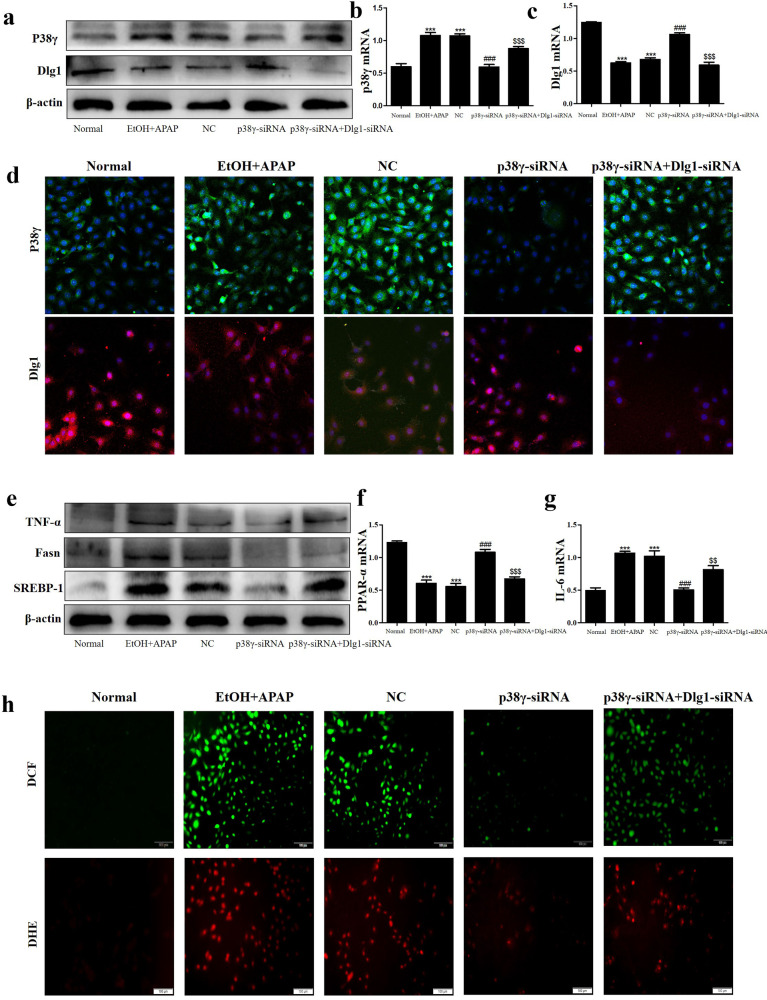

Interference of P38γ mitigated inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH + APAP-induced AML-12 cells by interacting with Dlg1

Next, we cotransfected p38γ-siRNA and Dlg1-siRNA into EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells. The Western blotting results showed that the expression level of p38γ was significantly increased in the cotransfection group, while the Dlg1 expression level was reduced compared with that in the group transfected with p38γ-siRNA (Fig. 7a–d). In addition, the cotransfection group showed obviously higher levels of TNF-α, Fasn and SREBP-1 than the group transfected with p38γ-siRNA (Fig. 7e–g). DCF and DHE staining also exhibited the same effects (Fig. 7h). Thus, these results showed that p38γ could not only regulate inflammatory reactions but also regulate lipid accumulation and oxidative stress by increasing the expression level of Dlg1 in AML-12 cells.

Fig. 7. P38γ interference mitigated inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH + APAP-induced AML-12 cells by interacting with Dlg1.

a–d IF, Western blotting and real-time PCR were used to detect the expression levels of p38γ and Dlg1 in AML-12 cells after transfection with p38γ-siRNA and Dlg1-siRNA. e–g Western blotting and real-time PCR were used to detect TNF-α, Fasn and SREBP-1 (the cleaved nuclear (~68 kDa) form of SREBP-1). h The production of ROS detected by DCF and DHE assays. ***P < 0.001 vs Normal group. ###P < 0.001 vs APAP or EtOH alone group. $$P < 0.01, $$$P < 0.001 vs EtOH+APAP group.

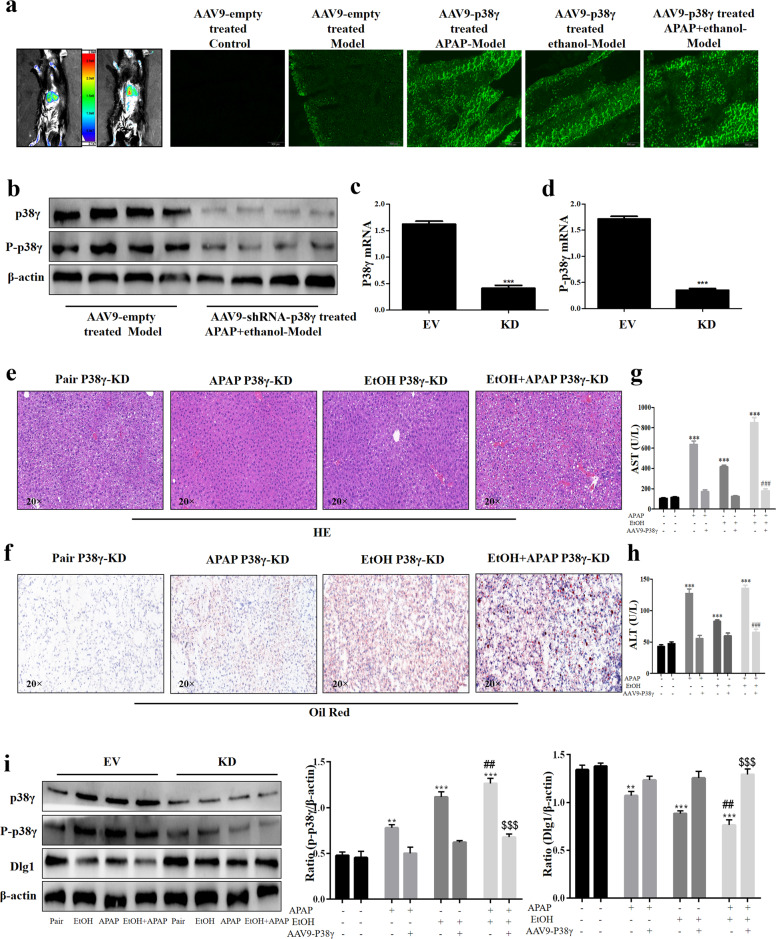

P38γ KD alleviated liver injury in EtOH- and APAP-induced mice

Next, we verified the role of p38γ in EtOH- and APAP-induced mice. AAV9-ShRNA-p38γ was injected into the tail vein to silence p38γ (Fig. 8a). According to the Western blotting analysis results, the p38γ protein expression level was downregulated in the AAV9-shRNA-p38γ group. Real-time PCR also verified the results at the gene level (Fig. 8b–d). In addition, significant fat accumulation in hepatocytes, mild necrosis and inflammatory infiltration and increased serum ALT and AST were exhibited in the EtOH+APAP group compared to the pair group. In contrast, p38γ KD exerted liver-protective effects in the EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 8e–h). The results of Western blotting analysis further confirmed that p38γ could regulate Dlg1 in the EtOH group and EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 8i).

Fig. 8. P38γ silencing alleviated liver dysfunction and injury in EtOH- and APAP-treated mice.

a Mouse in vivo imaging analysis showed that AAV9-shRNA-p38γ was specifically located in mouse liver tissue. b–d The mRNA and protein expression levels of p38γ and p-p38γ. e. HE staining in liver tissue. f. Oil Red O staining in liver tissue. g, h. Serum ALT and AST assay. i Western blotting detected the expression levels of p38γ and Dlg1. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Normal group. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs APAP or EtOH alone group. $$P < 0.01, $$$P < 0.001 vs EtOH+APAP group.

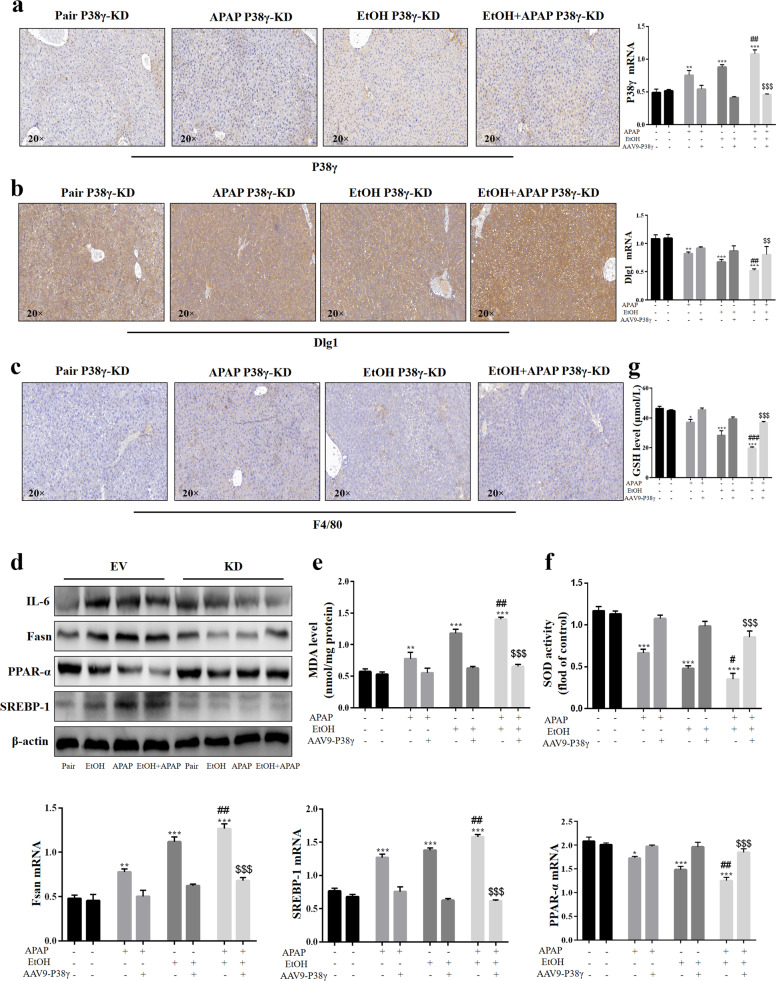

P38γ KD protected against liver inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH- and APAP-induced mice

In the p38γ KD model group, the p38γ expression level was reduced, but the Dlg1 expression level was increased (Fig. 9a, b). The results of IHC analysis showed that F4/80+ positive signals were alleviated in the p38γ KD EtOH+APAP group (Fig. 9c). In addition to the above experimental results, the authors also detected lower expression levels of IL-6, FASN and SREBP-1 and higher PPAR-α expression levels (Fig. 9d). Moreover, EtOH- and APAP-induced oxidative stress was obviously ameliorated in the p38γ KD mouse group (Fig. 9e–g), implying that p38γ might be an effective target for preventing EtOH+APAP-induced liver injury.

Fig. 9. P38γ KD protected against liver inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH- and APAP-induced mice.

a–c IHC analysis of p38γ, Dlg1, and F4/80. d The protein expression levels of IL-6, Fasn, PPAR-α, and SREBP-1 (the cleaved nuclear (~68 kDa) forms of SREBP-1). e–g The expression levels of MDA, SOD, and GSH. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Normal group. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs APAP or EtOH alone group. $$P < 0.01, $$$P < 0.001 vs EtOH+APAP group.

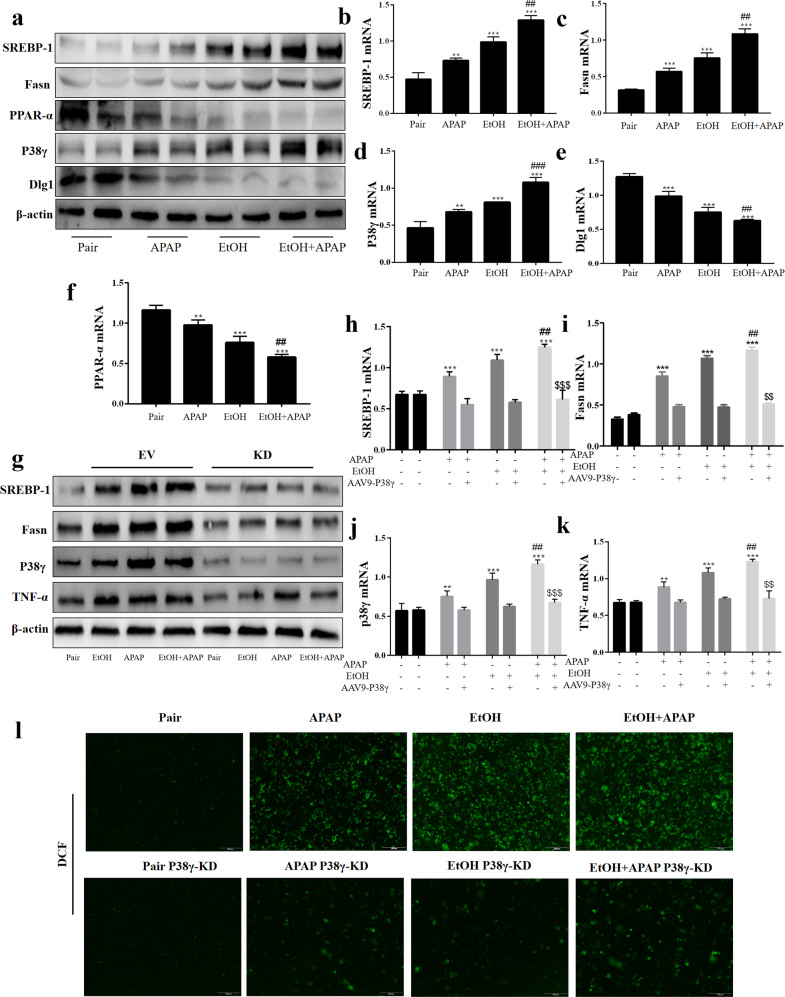

P38γ disruption alleviated inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in primary hepatocytes extracted from EtOH- and APAP-induced mice

Finally, primary hepatocytes were isolated from the control group and p38γ KD group, and the expression levels of markers related to inflammation, lipid accumulation, and oxidative stress were measured. Additionally, SREBP-1, Fasn, and p38γ expression levels were increased, while the expression levels of PPAR-α and Dlg1 were downregulated in the EtOH+APAP-induced group (Fig. 10a–f). The EtOH+APAP-induced elevation of SREBP-1, Fasn, p38γ and TNF-α was downregulated in the p38γ KD group compared to control hepatocytes (Fig. 10g–k). Moreover, DCF staining revealed that the p38γ KD group had alleviated oxidative stress (Fig. 10l). Taken together, these results confirmed that the important effects of hepatic p38γ destruction are regulated partly by diminishing EtOH+APAP-induced oxidative stress. Overall, p38γ might be an important regulator in EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury through modulation of Dlg1.

Fig. 10. P38γ disruption alleviated inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in primary hepatocytes extracted from EtOH- and APAP-induced mice.

a–f The mRNA and protein expression levels of SREBP-1, Fasn, PPAR-α, p38γ, and Dlg1 in the pair group and model primary hepatocytes. g–k The mRNA and protein expression levels of SREBP-1 (the cleaved nuclear (~68 kDa) forms of SREBP-1), Fasn, p38γ and TNF-α in Pair p38γ KD and model p38γ KD primary hepatocytes. l DCF analysis of ROS production. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Normal group. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs APAP or EtOH alone group. $$P < 0.01, $$$P < 0.001 vs EtOH+APAP group.

Discussion

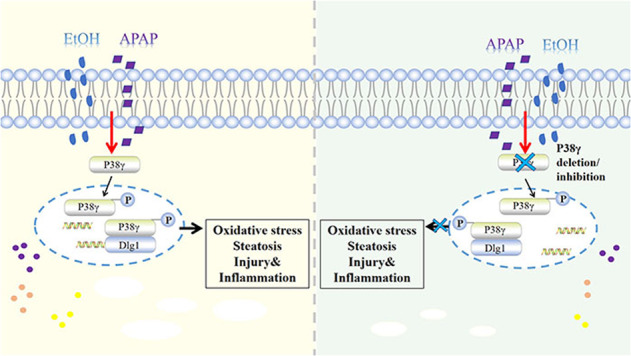

Liver disease is caused by hepatitis virus infection, poor habits, drug toxicity, alcohol and so on. It has a high incidence rate worldwide and poor long-term clinical efficacy, causing serious public health problems [24, 25]. In the clinic, complex liver diseases caused by multiple stimuli are common. Of note, alcohol is first converted into acetaldehyde through oxidative degradation by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and CYP2E1, and then acetaldehyde is oxidized to nontoxic acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) and coenzyme NAD or NADP to be excreted [26, 27]. Members of the ALDH family further convert reactive aldehydes, providing cells with potential protection against free radical oxidants (ROS) [27]. ROS accumulation in the liver is the main cause of the oxidative stress response [26, 28]. In addition, acetaldehyde enhances the redox cell state, and ROS activate transcription factors, thereby activating lipid biosynthesis genes and protecting liver cells from alcoholism [29]. As a common antipyretic and analgesic, APAP is often combined with GSH to remove the toxic compound NAPQI produced by metabolism. However, after GSH is exhausted, the accumulation of NAPQI will lead to liver injury [10]. Of note, it was suggested that even moderate EtOH consumption increases the manifestations and clinical course of liver damage in APAP acute liver failure. Generally, metabolic disorders and liver steatosis have been associated with stress signals, and the activation of lipokinases and stress kinases in obesity indicates the moderating effect of these proteins in diseases [30]. ALD is the main type of chronic underlying liver disease with DILI. EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury is a hot issue in most countries [30, 31]. Of note, related studies showed that APAP might affect the bioavailability of EtOH by inhibiting gastric ADH. The hepatotoxicity of APAP will increase due to chronic alcoholism. Interestingly, even after the alcohol in the body is completely removed, it will increase the toxic risk of APAP [32]. However, the mechanism of EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury needs to be further studied. Here, we demonstrated elevated inflammation, lipid accumulation, and oxidative stress in EtOH+APAP-cultured AML-12 cells and EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury in mice, which was related to high levels of activation of p38γ. However, AAV9-mediated p38γ KD in the liver attenuated EtOH+APAP-induced liver injury compared to Pair p38γ KD. Mechanistically, p38γ could bind to the Dlg1 protein in AML-12 cells treated with EtOH+APAP, thereby enhancing cell inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress.

P38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) play an important role in various cell stress responses, including apoptosis and necrosis, including cell death [33, 34]. The four members of the p38 isoform family are p38α, p38β, p38γ, and p38δ [35], which have high sequence homology and the iconic TGY phosphorylation motif in the kinase activation loop [36]. It is worth noting that the observed increase in hepatic p38γ is mainly due to changes in hepatocytes, as they constitute 80% of the liver volume [37–39]. P38γ can regulate hepatic metabolic reprogramming by regulating neutrophil infiltration [14], and p38γ is essential for the progression of liver tumorigenesis [15]. In addition, Xu et al. found that alcohol could activate the p38γ signaling pathway, and p38γ plays an important role in alcohol-enhanced aggressiveness of breast cancer [16]. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism of p38γ upregulation in EtOH- and APAP-induced livers is not yet clear. Similarly, the regulatory mechanism has not yet been determined and may include changes in translation, protein expression, and degradation. In this study, p38γ expression was increased by EtOH+APAP-induced AML-12 cells. Based on these results, we used p38γ-siRNA AML-12 cells and p38γ KD mouse models to examine whether p38γ could affect EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury. Furthermore, the vital regulatory role of p38γ in various processes, including cytokine production, protein synthesis, exocytosis, cell migration, stress and inflammatory responses, has been demonstrated [38, 40]. In addition, the knockout of p38γ will protect against methionine-choline-deficient (MCD)-induced steatosis [14]. Lipid accumulation and oxidative stress are vital to the occurrence and progression of liver diseases [41, 42]. In this article, the destruction of p38γ attenuated EtOH- and APAP-induced AML-12 cell injury. Moreover, the KD of p38γ could attenuate the inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury.

In addition, p38γ could be combined with Dlg1 by querying the STING database. Dlg1, also a member of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase family, maintains septate junctions and controls the localization of apical and adherens junction proteins, and it plays a vital role in cell polarity, proliferation and migration [43, 44]. Aline et al. found that Dlg1 can regulate the polarity of epithelial cells and is a signaling pathway destroyed by hepatitis C virus core protein [45]. In addition, Zinc finger protein 191 (ZNF191) activates Yap in hepatoma cells, inhibits cell migration and finally inhibits metastasis by upregulating DLG1 [46]. Interestingly, the STING database and Roberta et al. confirmed that p38γ could combine with Dlg1 to regulate peripheral nervous system (PNS) and central nervous system (CNS) myelination [47]. Related results showed that p38γ could bind to Dlg1 and reduce the expression level of Dlg1 in AML-12 cells treated with EtOH and APAP, thereby alleviating ROS production and liver damage.

In summary, our study showed that deletion of p38γ helps to alleviate EtOH+APAP-induced lipid accumulation and oxidative stress via the promotion of Dlg1. Thus, it is highly possible that p38γ could be considered a potential protein for the treatment of EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury. It was suggested that p38γ pharmacological inhibition might provide a feasible treatment for EtOH- and APAP-induced liver injury.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81700522, 81602344), Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (1808085MH235), and University Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Province (KJ2019A0268).

Author contributions

TX and JL conceived the research. SH, YY, ZYW, YCW, SXW, YH, JLM, LYL, CCY, HZ, and JFY performed cell culture, RT–qPCR, western blotting, IHC staining, and Co-IP assays. SH analyzed the data, sorted out figures and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-021-00795-1.

References

- 1.Tao Z, Zhang LH, Wu T, Fang XY, Zhao LG. Echinacoside ameliorates alcohol-induced oxidative stress and hepatic steatosis by affecting SREBP1c/FASN pathway via PPARalpha. Food Chem Toxicol. 2021;148:111956. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singal AK, Bataller R, Ahn J, Kamath PS, Shah VH. ACG clinical guideline: alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:175–94. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen H, Shen F, Sherban A, Nocon A, Li Y, Wang H, et al. DEP domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein suppresses lipogenesis and ameliorates hepatic steatosis and acute-on-chronic liver injury in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2018;68:496–514. doi: 10.1002/hep.29849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osna NA, Donohue TJ, Kharbanda KK. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and current management. Alcohol Res. 2017;38:147–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carolina IG, María JP, José EM, Aldo DM. Acetaminophen from liver to brain: New insights into drug pharmacological action and toxicity. Pharmacol Res. 2016;109:119–31. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ni HM, McGill MR, Chao X, Du K, Williams JA, Xie Y, et al. Removal of acetaminophen protein adducts by autophagy protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. J Hepatol. 2016;65:354–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saeedi BJ, Liu KH, Owens JA, Hunter-Chang S, Camacho MC, Eboka RU, et al. Gut-resident lactobacilli activate hepatic Nrf2 and protect against oxidative liver injury. Cell Metab. 2020;31:956–68 e955. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subramanya SB, Venkataraman B, Meeran M, Goyal SN, Patil CR, Ojha S. Therapeutic potential of plants and plant derived phytochemicals against acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3776. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benninger J, Schneider HT, Schuppan D, Kirchner T, Hahn EG. Acute hepatitis induced by greater celandine (Chelidonium majus) Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1234–7. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee WM, Kaplowitz N. Alcohol, fasting, and therapeutic dosing of acetaminophen: a perfect storm. Hepatology. 2021;73:1634–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.31747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Dell JR, Zetterman RK, Burnett DA. Centrilobular hepatic fibrosis following acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis in an alcoholic. JAMA. 1986;255:2636–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03370190120036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loonat AA, Martin ED, Sarafraz-Shekary N, Tilgner K, Hertz NT, Levin R, et al. p38gamma MAPK contributes to left ventricular remodeling after pathologic stress and disinhibits calpain through phosphorylation of calpastatin. FASEB J. 2019;33:13131–44. doi: 10.1096/fj.201701545R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarnieri F. Designing an orally available nontoxic p38 inhibitor with a fragment-based strategy. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1289:211–26. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2486-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.González-Terán B, Matesanz N, Nikolic I, Verdugo MA, Sreeramkumar V, Hernández-Cosido L, et al. p38gamma and p38delta reprogram liver metabolism by modulating neutrophil infiltration. EMBO J. 2016;35:536–52. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomás-Loba A, Manieri E, González-Terán B, Mora A, Leiva-Vega L, Santamans AM, et al. p38gamma is essential for cell cycle progression and liver tumorigenesis. Nature. 2019;568:557–60. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu M, Ren Z, Wang X, Comer A, Frank JA, Ke ZJ, et al. ErbB2 and p38gamma MAPK mediate alcohol-induced increase in breast cancer stem cells and metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:52. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0532-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zur R, Garcia-Ibanez L, Nunez-Buiza A, Aparicio N, Liappas G, Escós A, et al. Combined deletion of p38gamma and p38delta reduces skin inflammation and protects from carcinogenesis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:12920–35. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.González-Terán B, Cortés JR, Manieri E, Matesanz N, Verdugo Á, Rodríguez ME, et al. Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 controls TNF-alpha translation in LPS-induced hepatitis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:164–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI65124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertola A, Mathews S, Ki SH, Wang H, Gao B. Mouse model of chronic and binge ethanol feeding (the NIAAA model) Nat Protoc. 2013;8:627–37. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocca CJ, Ur SN, Harrison F, Cherqui S. rAAV9 combined with renal vein injection is optimal for kidney-targeted gene delivery: conclusion of a comparative study. Gene Ther. 2014;21:618–28. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang L, Liu XQ, Ma Q, Yang Q, Gao L, Li HD, et al. hsa-miR-500a-3P alleviates kidney injury by targeting MLKL-mediated necroptosis in renal epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2019;33:3523–35. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801711R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li LY, Yang JF, Rong F, Luo ZP, Hu S, Fang H, et al. ZEB1 serves an oncogenic role in the tumourigenesis of HCC by promoting cell proliferation, migration, and inhibiting apoptosis via Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021;42:1676–89. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-00575-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu MF, Koike S, Mello A, Nagy LE, Haj FG. Hepatic protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B disruption and pharmacological inhibition attenuate ethanol-induced oxidative stress and ameliorate alcoholic liver disease in mice. Redox Biol. 2020;36:101658. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vidal F, Lorenzo A, Auguet T, Olona M, Broch M, Gutiérrez C, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of ADH2, ADH3, CYP4502E1 Dra-I and Pst-I, and ALDH2 in Spanish men: lack of association with alcoholism and alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2004;41:744–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Guo P, Li W, Fang F, Zhu W, Fan J, et al. Perturbation of specific signaling pathways is involved in initiation of mouse liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2021;73:1551–69. doi: 10.1002/hep.31457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Shi J, Zhao L, Guan J, Liu F, Huo G, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0344 and Lactobacillus acidophilus KLDS1.0901 mixture prevents chronic alcoholic liver injury in mice by protecting the intestinal barrier and regulating gut microbiota and liver-related pathways. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69:183–97. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muzio G, Maggiora M, Paiuzzi E, Oraldi M, Canuto RA. Aldehyde dehydrogenases and cell proliferation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:735–46. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laurent A, Nicco C, Tran Van Nhieu J, Borderie D, Chéreau C, Conti F, et al. Pivotal role of superoxide anion and beneficial effect of antioxidant molecules in murine steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2004;39:1277–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu S, Li SW, Yan Q, Hu XP, Li LY, Zhou H, et al. Natural products, extracts and formulations comprehensive therapy for the improvement of motor function in alcoholic liver disease. Pharmacol Res. 2019;150:104501. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang F, Qi XM, Wertz R, Mortensen M, Hagen C, Evans J, et al. p38gamma MAPK is essential for aerobic glycolysis and pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2020;80:3251–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1572–85. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh A, Berger I, Remien CH, Mubayi A. The role of alcohol consumption on acetaminophen induced liver injury: Implications from a mathematical model. J Theor Biol. 2021;519:110559. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2020.110559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe T, Sekine S, Naguro I, Sekine Y, Ichijo H. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)-p38 pathway-dependent cytoplasmic translocation of the orphan nuclear receptor NR4A2 is required for oxidative stress-induced necrosis. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:10791–803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.623280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh A, Molinaro A, Ståhlman M, Khan MT, Schmidt C, Mannerås-Holm L, et al. Microbially produced imidazole propionate impairs insulin signaling through mTORC1. Cell. 2018;175:947–61 e917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaidi SK, Shen WJ, Bittner S, Bittner A, McLean MP, Han J, et al. p38 MAPK regulates steroidogenesis through transcriptional repression of STAR gene. J Mol Endocrinol. 2014;53:1–16. doi: 10.1530/JME-13-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin JH, Jeong JY, Jin Y, Kim ID, Lee JK. p38beta MAPK affords cytoprotection against oxidative stress-induced astrocyte apoptosis via induction of alphaB-crystallin and its anti-apoptotic function. Neurosci Lett. 2011;501:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang Z, Xia N, Yuan X, Zhu X, Xu G, Cui S, et al. PRDX1 is involved in palmitate induced insulin resistance via regulating the activity of p38MAPK in HepG2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;465:670–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cuenda A, Sanz-Ezquerro JJ. p38gamma and p38delta: from spectators to key physiological players. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42:431–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin X, Wang M, Zhang J, Xu R. p38 MAPK: a potential target of chronic pain. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:4405–18. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140915143040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koh A, Mannerås-Holm L, Yunn NO, Nilsson PM, Ryu SH, Molinaro A, et al. Microbial imidazole propionate affects responses to metformin through p38gamma-dependent inhibitory AMPK phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2020;32:643–53 e644. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dunn W, Shah VH. Pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;20:445–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leise MD, Poterucha JJ, Talwalkar JA. Drug-induced liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marziali F, Dizanzo MP, Cavatorta AL, Gardiol D. Differential expression of DLG1 as a common trait in different human diseases: an encouraging issue in molecular pathology. Biol Chem. 2019;400:699–710. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2018-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong X, Wei L, Guo X, Yang Z, Wu C, Li P, et al. Dlg1 maintains dendritic cell function by securing voltage-gated K+ channel integrity. J Immunol. 2019;202:3187–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Awad A, Sar S, Barré R, Cariven C, Marin M, Salles JP, et al. SHIP2 regulates epithelial cell polarity through its lipid product, which binds to Dlg1, a pathway subverted by hepatitis C virus core protein. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:2171–85. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e12-08-0626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu D, Liu G, Liu Y, Saiyin H, Wang C, Wei Z, et al. Zinc finger protein 191 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through discs large 1-mediated yes-associated protein inactivation. Hepatology. 2016;64:1148–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.28708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noseda R, Guerrero-Valero M, Alberizzi V, Previtali SC, Sherman DL, Palmisano M, et al. Kif13b regulates PNS and CNS myelination through the Dlg1 scaffold. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.