Abstract

Omeprazole is a proton pump inhibitor that has recently been reported to exhibit anticancer activity against several types of cancer. However, the anticancer mechanisms of omeprazole remain elusive. Snail is an oncogenic zinc finger transcription factor; aberrant activation of Snail is associated with the occurrence and progression of cancer. In this study, we investigated whether Snail acted as a direct anticancer target of omeprazole. We showed that omeprazole displayed a high binding-affinity to recombinant Snail protein (Kd = 0.076 mM), suggesting that omeprazole directly and physically binds to the Snail protein. We further revealed that omeprazole disrupted CREB-binding protein (CBP)/p300-mediated Snail acetylation and then promoted Snail degradation through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway in HCT116 cells. Omeprazole treatment markedly suppressed Snail-driven epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in aggressive HCT116, SUM159, and 4T1 cancer cells in vitro and reduced EMT-associated tumor invasion and metastasis in cancer cell xenograft models. Omeprazole also inhibited tumor growth by limiting Snail-dependent cell cycle progression. Overall, this study, for the first time, identifies Snail as a target of omeprazole and reveals a novel mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of omeprazole against cancer. This study strongly suggests that omeprazole may be an excellent auxiliary drug for treating patients with malignant tumors.

Keywords: omeprazole, Snail, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration, metastasis, tumor growth, cell cycle, anticancer action

Introduction

Malignancy (cancer) is a chronic and common disease that seriously threatens public health and imposes a tremendous economic burden on society [1, 2]. According to the latest statistics, 19.3 million new cancer patients were projected to be diagnosed worldwide in 2020, and 10 million patients were projected to die of cancer [3]. Approximately 90% of cancer deaths are caused by metastasis, which is characterized by potent invasion, high recurrence rates, and poor prognosis [4]. Despite the various modern therapies, patients with metastatic tumors present an enormous clinical challenge. Therefore, new treatment strategies for cancer patients are urgently required.

Omeprazole is a proton pump inhibitor that has been developed for the treatment of acid-related diseases [5, 6]. Recently, many studies have shown that omeprazole exhibits anticancer activity in several types of cancer, such as gastric cancer [7], pancreatic cancer [8], human B-cell malignancies [9], and glioblastoma [10]. However, the precise mechanisms underlying the anticancer properties of omeprazole remain elusive. Of note, omeprazole can strongly inhibit the invasion and migration of aggressive cancer cells, which is reminiscent of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a key event during metastasis [11, 12]. EMT is characterized by dramatic changes in the expression of the key epithelial cell-cell adhesion protein E-cadherin and the mesenchymal markers vimentin, fibronectin, and N-cadherin [13]. Based on a study of EMT-associated transcription factors, including the Snail/Slug family [14], ZEB1 [15], and Twist [16], which can induce EMT, we found that omeprazole suppresses Snail expression without affecting the expression of other EMT-associated transcription factors.

Snail is a major transcription factor that triggers EMT by suppressing the expression of cellular adhesion proteins, such as E-cadherin [17, 18]. Accumulating evidence shows that Snail is highly expressed in some aggressive tumors, but is essentially undetectable in normal tissues, indicating that Snail is closely related to cancer progression [19, 20]. In addition, Snail overexpression promotes EMT and enhances tumor invasion, metastasis, and recurrence, as well as therapeutic resistance [21, 22]. Such an important role in cancer progression makes Snail an appealing target for cancer therapy. However, there is no Snail inhibitor available in the clinic to date. Thus, in the present study, we aimed to reveal the direct targets of omeprazole that underlie its anticancer ability. We provided comprehensive evidence that omeprazole suppresses Snail-driven EMT and tumor metastasis both in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, omeprazole was first found to inhibit Snail-dependent cell cycle progression, thereby suppressing tumor growth. Our study advances the current understanding of the molecular mechanisms of omeprazole in cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Compounds

Omeprazole (≥ 98%) and pantoprazole (≥98%) were purchased from Solarbio Life Science (Beijing, China). Compounds used in assays were dissolved in 100% DMSO as stock solutions and stored at −20 °C for in vitro studies. The final DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.1% (v/v). Omeprazole sodium (≥98%, Solarbio) was dissolved in normal saline (NS) for in vivo studies.

Cell isolation and culture

All cell lines except for those with special instructions were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). HCT116, HEK293T, 4T1, 4T1.2, DLD1, SUM159, and RKO cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. PyMT cancer cells were generated and maintained in our laboratory as described previously. PyMT cancer cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), 10 ng/ml EGF (PeproTech), 500 ng/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 5 mg/ml insulin (Sigma), 20 ng/ml cholera toxin (Sigma) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo). Cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination every month, and only mycoplasma-negative cells were used.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

For immunoblot analysis, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Thermo) containing a protease inhibitor (Bimake, Houston, TX, USA). Primary antibodies against Snail (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA, 3879), Slug (Cell Signaling Technology, 9585), pan-acetyl-Lys (pan-AcK; Cell Signaling Technology, 9441), CBP (Cell Signaling Technology, 7389), p300 (Cell Signaling Technology, 70088), ubiquitin (Cell Signaling Technology, 3936), HDAC1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 5356), vimentin (Cell Signaling Technology, 5741), phospho-Rb (Cell Signaling Technology, 8516), CyclinD1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 55506), E-cadherin (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA, 610181), CDK4 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA, ab199728), CDK6 (Wanlei, Shenyang, China, WL03460), FLAG (Sigma, F3165), and β-actin (Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, CA, USA, sc47778) were used for protein detection. For IP, cells were lysed in buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% NP-40) containing a protease inhibitor. Total cell lysates were incubated overnight with antibodies against immunoglobulin G (control), FLAG (1:100), and Snail (1:100), and then conjugated to Protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Quantitative real-time PCR

qRT–PCR was performed using Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 qPCR system (Thermo) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Standard curves were generated, and the relative amount of each target gene mRNA was normalized to β-actin. The oligonucleotide sequences of the qRT–PCR primers were as follows:

β-ACTIN 5’-TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA-3’/5’CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA-3’,

β-actin 5’-GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG-3’/5’-CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT-3’,

SNAIL 5’-TCGGAAGCCTAACTACAGCGA-3’/5’-AGATGAGCATTGGCAGCGAG-3’,

Snail 5’-CACACGCTGCCTTGTGTCT-3’/5’-GGTCAGCAAAAGCACGGTT-3’,

CDH1 5’-GTCTCCTCTTGGCTCTGCCAG-3’/5’-ATTCACTCTGCCCAGGACGCG-3’,

Cdh1 5’-GAAGTCCATGGGGCACCACCA-3’/5’-CTGAGACCTGGGTACACGCTG-3’,

CDH2 5’-CGGCCGTCACAGTGACAG-3’/5’-CCAGGCTGGTGTATGGGGTTG-3’,

Cdh2 5’-TGTGCACGAAGGACAGCCCCT-3’/5’-CCTGCTCTGCAGTGAGAGGGA-3’,

VIM 5’-GGAGGAAATGGCTCGTCACC-3’/5’-GAGAAATCCTGCTCTCCTCGCC-3’,

Vim 5’-AGCGTGGCTGCCAAGAACCTC-3’/5’-GCAGGGCATCGTGTTCCGGT-3’,

FN1 5’-CATCCCTGACCTGCTTCCTGG-3’/5’-CTGTACCCTGTGATGGGAGCC-3’,

Fn1 5’-GGGTGACACTTATGAGCGCCC-3’/5’-GACTGACCCCCTTCATGGCAG-3’.

Protein expression, purification, and pull-down assays

GST-CBP-HAT proteins were expressed in and purified from E. coli (BL21). Strep-Snail recombinant proteins were expressed in and purified from baculovirus-transfected insect cells. Bead-bound Strep-tagged proteins were preincubated with various concentrations of omeprazole for 1 h at 4 °C on a rotator, and the eluted GST-CBP-HAT protein was added to the reaction mixtures and incubated overnight. The bound complexes were eluted and subjected to Coomassie blue staining.

BLI assay

Binding of various concentrations of omeprazole or pantoprazole to Snail recombinant proteins was evaluated using BLI assays in an Octet RED96 instrument (ForteBio). Briefly, Snail recombinant proteins were dissolved in PBS. For biotin labeling, proteins were incubated with EZ-Link Sulfo NHS-LC-LC-Biotin (Thermo) for 60 min at room temperature (1:3 molar ratio of protein to biotin). Spin desalting columns (Thermo) were used to remove excess biotin. Biotinylated proteins were immobilized onto Super Streptavidin (SSA) biosensors for further measurement. A duplicate set of SSA sensors incubated in buffer without protein was used as the negative binding control. The assay was performed in black 96-well plates with different concentrations of omeprazole or pantoprazole and PBS as the nonspecific interaction control. Binding events were recorded according to shifts in the light interference pattern. The data were then analyzed with ForteBio Data Analysis software to calculate the association and dissociation rates using a 1:1 binding model, and Kd was calculated as Koff/Kon.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 4000 cells per well in culture medium. The cells were allowed to adhere for 24 h and were then treated with various concentrations of omeprazole for another 48 h. Cell proliferation was measured with a CCK-8 kit (Yeasen, Shanghai, China), and the absorbance was measured with a Molecular Devices microplate reader at 450 nm.

Cell migration assay

Invasion assays were performed in 8-μm pore size chambers (BD Biosciences). Briefly, cells were treated with vehicle or various concentrations of omeprazole for 48 h. The cells were then seeded in FBS-free DMEM culture medium in the upper chambers at equal densities, and 1 ml of complete medium supplemented with 10% FBS was added to the lower chambers. Cells were allowed to invade the lower chambers for a few hours. The membranes in the chambers were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (w/v), and the purple area was photographed and quantified.

Flow cytometric analysis

Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a FACS Celesta flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data were quantitatively analyzed with FlowJo software. Briefly, cancer cells were treated with vehicle or various concentrations of omeprazole for 48 h. For apoptosis analysis, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined with a FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For cell cycle analysis, the percentages of cells in various cell cycle phases were determined whih a kit (KeyGen Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All FACS analyses were performed in triplicate, and representative results are shown.

Cloning, cell transfection, and viral transduction

p3XFLAG-Snail, pLKO.1-Snail-shRNA1 (bp 468–486), pLKO.1-Snail-shRNA2 (bp 1515–1533), and GST-CBP-HAT were constructed by Gen-Script Biotech Inc. HA-ubiquitin, pLKO.1-TRC, psPAX2, and pMD2.G were purchased from Addgene. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To generate lentiviral plasmids, pLKO.1-shRNA, psPAX2, and pMD2.G at a ratio of 4:3:1 were transfected into HEK293T cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated with fresh medium 24 h post transfection, and conditioned medium containing viral particles was harvested 48 h and 72 h post transfection. For viral transduction, target cells were treated with a mixture of lentiviral particles and fresh medium (1:1, v/v) for 24 h and re-fed with the mixture for another 24 h in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/ml; Sigma). Cells were transduced for an additional 24 h and selected by culture in puromycin (Sigma)-containing medium.

Mouse xenograft model

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University, and mice were housed under standard specific pathogen-free conditions. To establish the subcutaneous xenograft model, HCT116 cells were counted and resuspended in a 1:1 mixture of PBS and Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Cells were then injected (1 × 106 cells/mouse) subcutaneously into the dorsal flanks of BALB/c nu/nu mice at 7 weeks of age. Once the tumors reached a volume of ~100 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into three groups (n = 6 mice in each group). The mice were orally administered vehicle (NS), 150 mg/kg omeprazole, or 300 mg/kg omeprazole daily for two consecutive weeks. The weight of mice were weighed with an electronic balance, and tumor growth was measured daily by the same person with a calliper. The volumes of the implanted tumors were calculated using the formula π × length × width2/6. After treatment, the mice were euthanized, and tumors and key organs were harvested, photographed, and weighed. Tissues were either fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for histological and immunohistochemical analyses or snap-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C for immunoblot analysis. In some experiments, 2×106 control-shRNA-expressing cells and Snail-shRNA2-expressing cells were inoculated subcutaneously into BALB/c nu/nu mice.

MMTV-PyMT mouse model

MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice on an FVB background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (002374), and the colony was maintained in our laboratory. MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice aged 8 weeks were divided into two groups and were then orally administered vehicle or omeprazole (300 mg/kg) for 27 consecutive days. The mice were weighed with an electronic balance, and tumor growth was measured daily by the same person with a calliper. After treatment, the mice were euthanized, and the tumors, lungs and key organs were harvested for further use.

Hepatic metastasis model

A left subcostal surgical incision was made in BALB/c nu/nu mice at 7 weeks of age. GFP-labeled HCT116 cells (2 × 106) were intrasplenically injected into the spleens of these mice. The mice were randomly divided into two groups (n = 6 mice in each group) and orally administered vehicle or omeprazole (300 mg/kg) for three consecutive weeks starting from the third day after surgery. The mice were weighed daily with an electronic balance. After treatment, the mice were euthanized, and livers were then harvested for analysis.

Bone metastasis model in BALB/c mice established by fat pad inoculation

To establish the bone metastasis model, 4T1.2 tumor cells were counted and resuspended in a 2:1 mixture of PBS and Matrigel. The cells were then injected into the fourth mammary fat pad of BALB/c mice at 7 weeks of age. Tumors were palpable ~1 week after inoculation. The mice were randomly divided into two groups (n = 6 mice in each group) and orally administered vehicle or omeprazole (300 mg/kg) for 23 consecutive days. The mice were weighed with an electronic balance. After treatment, the mice were euthanized, and lungs, and bone were harvested for analysis.

Immunohistochemical staining

Tissue samples were fixed with 4% PFA and embedded in paraffin. For IHC analysis, tumors were sliced into 5 μm thick sections and mounted on polarized glass, deparaffinized and subjected to antigen heat retrieval with citric acid-based Antigen Unmasking Solution. Tumor sections were sequentially permeabilized with 0.3% H2O2 (in PBS); blocked with 5% goat serum (in PBS); incubated with primary antibodies against Ki67 (Abcam, ab15580), phospho-histone H3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9701), cleaved Caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9661), phospho-Rb (Ser807/811) (Cell Signaling Technology, 8516), Cyclin D1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 55506), and Snail (Cell Signaling Technology, 3879); and incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories) or biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories). A standard avidin-biotin complex (ABC) kit (Vector Laboratories) and a 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) HRP Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. After a review of haematoxylin staining, the positive staining of tumor cells was scored.

Immunofluorescence and immunocytochemical staining

For ICC analysis, cells were grown on chamber slides, fixed with 4% PFA, and incubated with primary antibodies against E-cadherin (BD Biosciences, 610181), vimentin (Cell Signaling Technology, 5741), and Snail (Cell Signaling Technology, 3879) followed by goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo). 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was performed at room temperature. Finally, cells were observed with a Zeiss LSM 800 microscope. For IF analysis, tumor sections were incubated with primary antibodies against E-cadherin (BD Biosciences, 610181), vimentin (Cell Signaling Technology, 5741), CD31 (Dianova, Germany, DIA310), α-SMA (Abcam, ab5694), VEGFA (Abcam, ab52917), and K14 (BioLegend, 905303) followed by goat anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, and anti-rat Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (all from Thermo).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Two-tailed Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to evaluate the significance of differences. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate significant differences.

Results

Omeprazole blocks migration and EMT in aggressive cancer cells

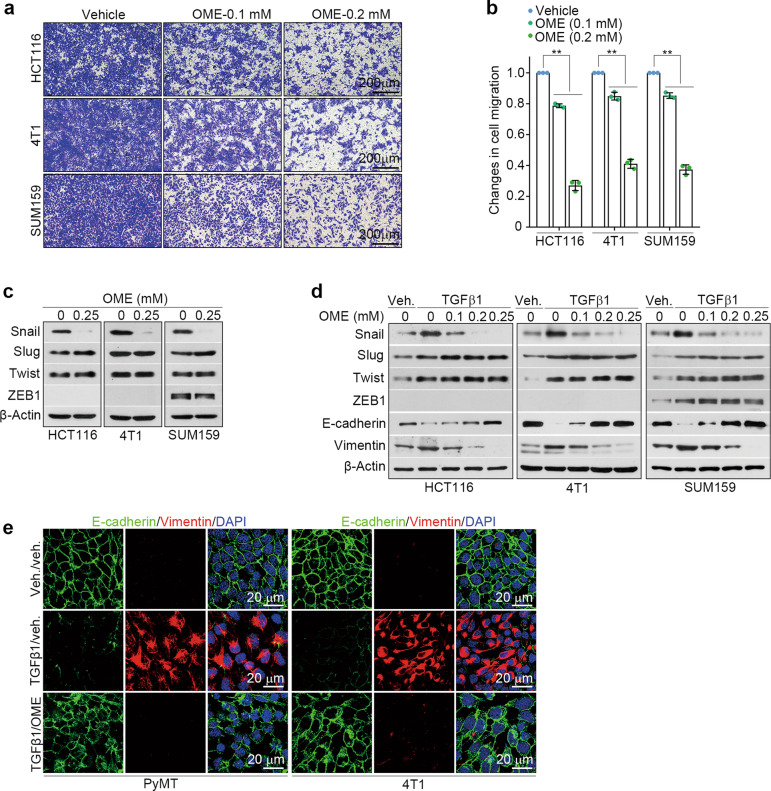

Given the potential role of omeprazole in the inhibition of tumor metastasis [23], we used chambers to test the effects of omeprazole on the migration of HCT116, SUM159, and 4T1 cells. Cells were treated with omeprazole for 48 h, and the results showed that omeprazole dose-dependently decreased the proportion of migrated cells in all three cancer cell lines (Fig. 1a, b). EMT is a key event in metastasis [11, 12]. Hence, we examined the effects of omeprazole on the expression levels of EMT-associated transcription factors, including Snail, Slug, Twist, and ZEB1. Immunoblot analysis revealed that omeprazole decreased the Snail protein level, but had no effect on the expression levels of other transcription factors (Fig. 1c). TGFβ is considered to be a primary inducer of EMT [24]. We further tested whether omeprazole blocks TGFβ-driven EMT phenotypes in cancer cells. Cells were pretreated with vehicle or TGFβ1 for 24 h and were then treated with vehicle or omeprazole for another 48 h. As shown, omeprazole inhibited the expression of Snail but did not affect Slug, Twist, or ZEB1 expression (Fig. 1d). Consistent with these results, omeprazole blocked the morphological changes indicative of TGFβ-driven EMT, including upregulation of epithelial markers (E-cadherin) and downregulation of mesenchymal markers (fibronectin, vimentin, and N-cadherin) (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. S1a). Collectively, these results indicate that omeprazole blocks cell migration and EMT in vitro.

Fig. 1. Omeprazole inhibits migration and EMT in vitro.

a The inhibitory effect of omeprazole on the migration of serum-stimulated HCT116, SUM159, and 4T1 cells. b The inhibitory effect was quantified as described in a (n = 3). c The levels of Snail, Slug, Twist, and ZEB1 in cancer cells treated with omeprazole were evaluated by immunoblotting. d The levels of Snail, Slug, Twist, ZEB1, E-cadherin, and vimentin in the presence of TGFβ1 (2 ng/ml) in cancer cells treated with omeprazole were evaluated by immunoblotting (n = 3). e Immunofluorescence staining of E-cadherin and vimentin in MMTV-PyMT (left) and 4T1 (right) cells as described in d. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance was used for statistical analysis. **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle.

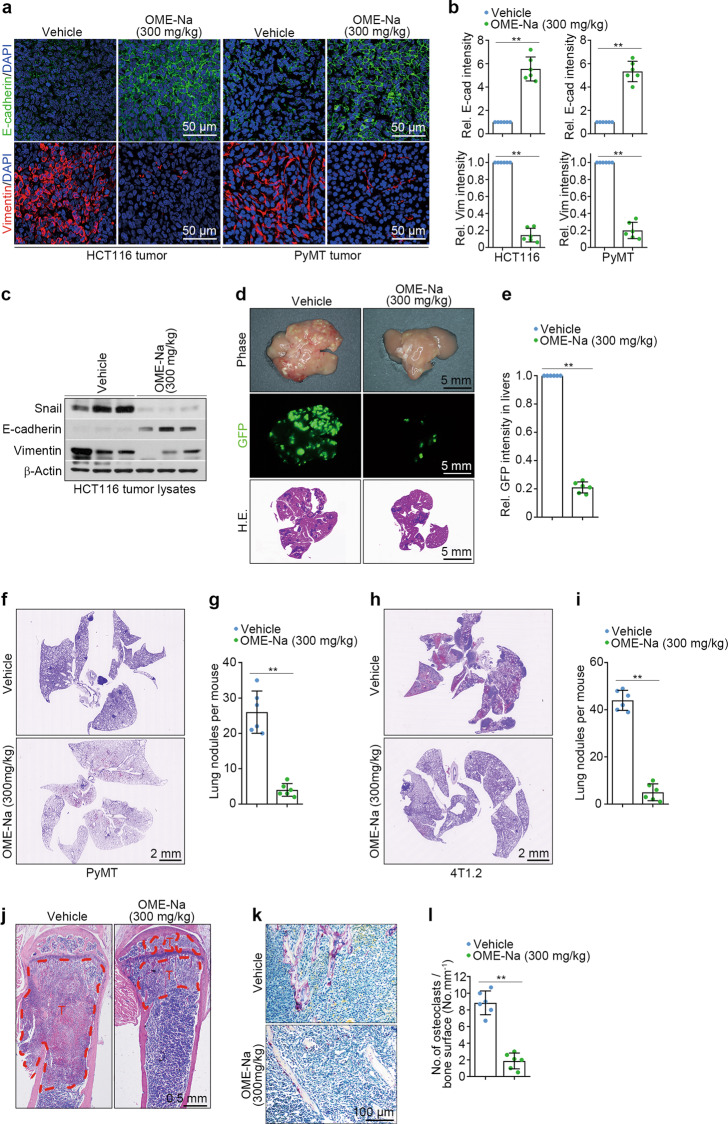

Omeprazole inhibits EMT-associated distant tumor metastasis

Next, we investigated whether omeprazole has similar effects in vivo using an HCT116 xenograft model. As shown, after 14 days of oral administration at a dosage of 300 mg·kg−1·d−1, impairment of EMT was detected in omeprazole-treated xenograft tumors, as indicated by the increased E-cadherin expression accompanied by the reduced vimentin expression (Fig. 2a–c). Notably, omeprazole markedly suppressed Snail expression (Fig. 2c). We also examined the effect of omeprazole on tumor metastasis using a hepatic metastasis model. To this end, nude mice were intrasplenically implanted with GFP-labeled HCT116 cells and orally administered omeprazole for three consecutive weeks. The results showed that omeprazole robustly reduced nodule formation and tumor metastasis in the liver (Fig. 2d, e).

Fig. 2. Omeprazole suppresses EMT and EMT-associated tumor metastasis in vivo.

a, b Immunofluorescence staining of E-cadherin and vimentin in HCT116 xenograft tumors and PyMT primary tumors; the staining intensity of the tumors was quantified (n = 6). c The levels of Snail, E-cadherin and vimentin in tumor lysates were evaluated by immunoblotting (n = 3 pools from six mice). d, e Representative photographs of metastatic nodules (top), GFP fluorescence (middle), and H&E staining (bottom) of livers; the fluorescence intensity of the livers was quantified (n = 6). f, g Representative H&E staining images of lungs from MMTV-PyMT mice; lung nodules were quantified (n = 6). h, i Representative H&E staining images of the lungs of BALB/c mice; lung nodules were quantified (n = 6). j Representative H&E staining images of bone sections from BALB/c mice (n = 6). T, tumor cells; B, bone. k, l Representative TRAP staining images of bone sections from BALB/c mice; the staining intensity was quantified (n = 6). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle.

The majority of cancer-related deaths are attributed to metastasis to distant organs, such as the lungs and bones [25]. Therefore, we tested the antimetastatic efficacy of omeprazole using MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice, a mouse model of breast cancer that exhibits spontaneous development of mammary tumors and mirrors the multistep progression of human breast cancer [26]. For this purpose, 2-month-old female MMTV-PyMT littermate mice were treated with vehicle or omeprazole for 27 consecutive days. The results showed that omeprazole-treated mice displayed markedly fewer and smaller metastatic lung nodules than vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2f, g). Moreover, omeprazole markedly increased the expression of E-cadherin and decreased the expression of vimentin, suggesting that omeprazole suppresses EMT in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice (Fig. 2a, b). We also tested the antitumor efficacy of omeprazole using a bone metastasis model in BALB/c mice, whose metastasis pattern closely resembles that observed in human breast cancer [27]. To do this, 4T1.2 cells, which are capable of spontaneous metastasis to both bone and lungs, were orthotopically injected into the fourth mammary fat pad of female BALB/c mice [28]. The mice were treated daily with omeprazole at a dose of 300 mg/kg for 23 days. At the treatment termination, we observed that omeprazole-treated mice had developed markedly fewer and smaller metastatic lung nodules than vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2h, i). Furthermore, H&E staining showed that omeprazole significantly reduced the number of bone lesions compared with that in vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2j). Consistent with these results, histological analysis revealed a marked decrease in the number of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive (TRAP+) osteoclasts in the bone tissue of omeprazole-treated mice compared with vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2k, l). Taken together, our findings suggest that omeprazole strongly suppresses EMT and EMT-associated tumor metastasis in vivo.

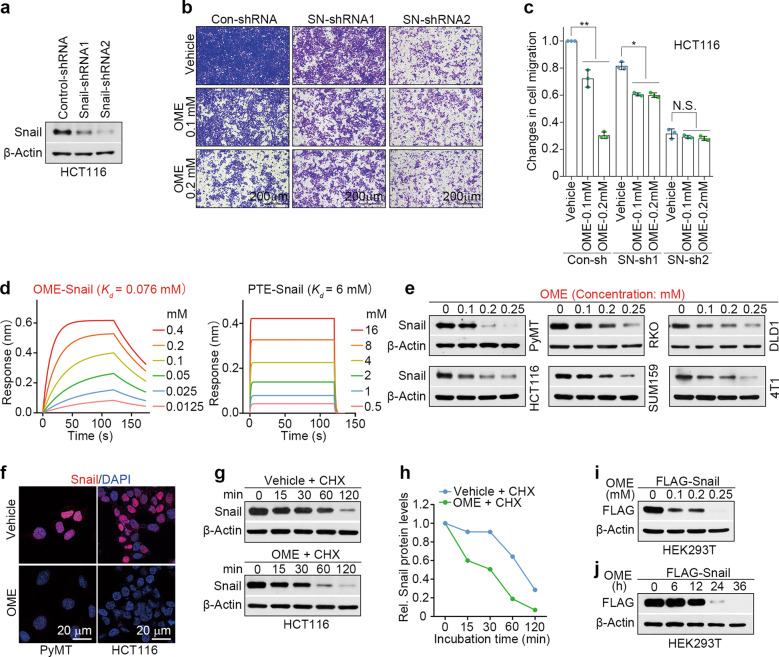

Omeprazole targets the Snail protein and reduces its stability

Snail has been reported to induce EMT and promote metastasis in various types of cancer [11, 24]. Therefore, we sought to determine whether omeprazole inhibits cell migration by targeting Snail. We transduced HCT116 and SUM159 cells with Snail-shRNA and subjected them to migration analysis. As expected, omeprazole markedly suppressed the migration of control HCT116 cells and HCT116 cells with moderate Snail silencing, but had no effect on the migration of HCT116 cells with complete Snail silencing. Cells with complete Snail silencing exhibited a significant reduction in cell migration, whereas cells with moderate Snail silencing displayed a slight reduction (Fig. 3a–c). A similar phenotype was observed in SUM159 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2a–c). These results suggest that Snail is a potential target of omeprazole in the suppression of migration.

Fig. 3. Omeprazole targets the Snail protein and reduces its stability.

a–c The expression of Snail in HCT116 cells transfected with control-shRNA, Snail-shRNA1 or Snail-shRNA2 was determined by immunoblotting, and the inhibitory activity of omeprazole on migration was quantified (n = 3). d The binding affinities of omeprazole (left) and pantoprazole (right) for Snail were measured by biolayer interferometry. e The expression of Snail in various cancer cells after omeprazole treatment was evaluated by immunoblotting. f Immunofluorescence staining of Snail in MMTV-PyMT (left) and HCT116 (right) cells after omeprazole treatment. g, h The expression of Snail in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX, 100 μg/ml) in HCT116 cells treated with omeprazole was evaluated by immunoblotting, and the level of Snail expression was quantified. The level of FLAG-tagged Snail in HEK293T cells treated with omeprazole for 48 h (i) and in cells treated with 0.2 mM omeprazole for different times (j) was evaluated by immunoblotting. All representative blots shown are from three independent experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance was used for statistical analysis. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; N.S. not significant vs. vehicle.

To explore whether omeprazole directly binds with Snail, we performed a biolayer interferometry (BLI) assay using recombinant Snail protein purified from Sf9 insect cells. As shown, omeprazole had a high binding-affinity to recombinant Snail protein (Kd = 0.076 mM), indicating that omeprazole directly and physically binds to Snail (Fig. 3d, left panel). Compared with omeprazole, pantoprazole (serving as a negative control) showed approximately 79-fold less potent toward Snail (Kd = 6 mM) (Fig. 3d, right panel). We next investigated the effect of omeprazole on Snail expression in cancer cells. Immunoblot analysis revealed that omeprazole dose-dependently decreased the Snail protein level in various cancer cell lines (Fig. 3e). In addition, we observed that omeprazole reduced the Snail protein level in a time-dependent manner in HCT116 and SUM159 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2d). The inhibitory effect of omeprazole on Snail expression was further confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis, which showed that omeprazole markedly decreased the Snail protein level in omeprazole-treated MMTV-PyMT and HCT116 cells (Fig. 3f). As expected, pantoprazole did not affect Snail expression (Fig. S2e). Furthermore, we found that the Snail mRNA level did not significantly change in omeprazole-treated cells, suggesting that omeprazole regulates Snail expression at the post translational level (Fig. S2f). To directly test whether omeprazole affects Snail protein stability, we used cycloheximide (CHX; 100 μg/ml) to block protein synthesis in vehicle- and omeprazole-treated HCT116 cells. As shown, Snail protein stability decreased rapidly in omeprazole-treated cells, whereas the Snail protein was more stable in vehicle-treated cells, suggesting that omeprazole indeed accelerates Snail protein degradation (Fig. 3g, h). We next examined the effect of omeprazole on the protein stability of exogenous Snail. Immunoblot analysis revealed that omeprazole markedly decreased the expression of FLAG-tagged Snail protein in both dose- and time-dependent manners (Fig. 3i, j). Notably, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is recognized to mediate the effect of omeprazole, and AhR (or its ligand) has been shown to inhibit Snail expression and the Snail-driven EMT program in cancer cells [10, 23, 29–33]. To determine whether AhR is involved in omeprazole-mediated inhibition of EMT/Snail, we silenced AhR expression in HCT116 and SUM159 cells and assessed the Snail level in control and AhR-silenced cells in the presence of vehicle or omeprazole. As shown, AhR silencing robustly increased Snail expression in HCT116 and SUM159 cells (Fig. S2g–i). Interestingly, omeprazole efficiently reduced Snail expression in AhR-silenced cells, and the Snail levels in the treated cells were even lower than those in control cells (Fig. S2h, i). These findings suggest that AhR serves as an upstream negative regulator of Snail and that omeprazole effectively reverses the augmented Snail expression in AhR-silenced cancer cells. Collectively, these data indicate that Snail is a direct target protein of omeprazole.

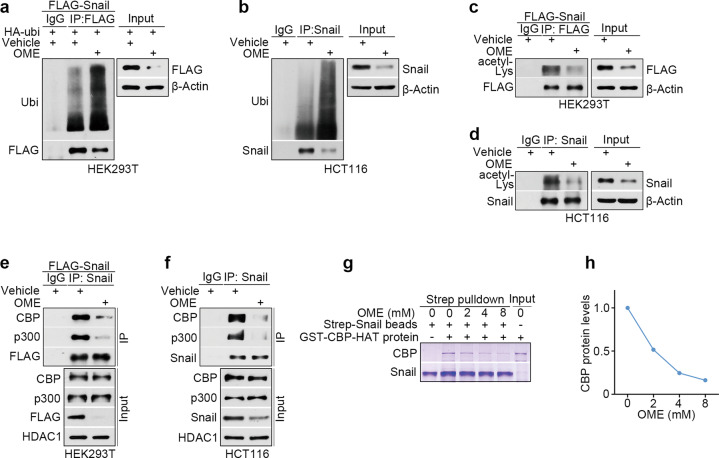

Omeprazole promotes Snail degradation by disrupting CBP/p300-mediated Snail acetylation

To further study the molecular mechanisms of Snail degradation by omeprazole, we co-expressed hemagglutinin (HA)-ubiquitin and FLAG-tagged Snail in HEK293T cells and examined Snail ubiquitination levels with an immunoprecipitation assay. We found that omeprazole greatly increased the ubiquitination level of the Snail protein (Fig. 4a). It has been reported that acetylation can stabilize the Snail protein [34]. Therefore, we tested whether omeprazole affects Snail acetylation. The results showed that omeprazole significantly decreased the acetylation of the Snail protein (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, we tested whether endogenous Snail is similarly regulated by omeprazole in HCT116 cells. Consistent with the above observations, omeprazole increased the ubiquitination level of Snail and decreased the acetylation of Snail in HCT116 cells (Fig. 4b, d). Previous studies have shown that CBP/p300 is a critical protein that acetylates Snail [34]. Therefore, we investigated whether omeprazole impairs Snail acetylation by disrupting the interaction of Snail with CBP/p300. As shown, omeprazole significantly reduced the Snail-bound CBP/p300 level without affecting total CBP/p300 expression in HCT116 and exogenous Snail-transfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 4e, f). We further tested whether omeprazole disrupts the interaction between Snail and CBP using an in vitro Streptavidin pull-down assay. For this purpose, we purified Strep-tagged recombinant Snail proteins in insect cells (sf9) and purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)-CBP-HAT in E. coli. The results showed that omeprazole diminished the interaction of GST-CBP-HAT with Strep-Snail recombinant proteins in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that omeprazole directly interferes with the binding between Snail and CBP (Fig. 4g, h). Slug is a member of the Snail family and plays a key role in cancer progression [12, 35]; thus we investigated whether omeprazole has a similar effect on Slug. Unexpectedly, we found that Slug and CBP could not interact, which indicated that Slug protein expression is regulated by other proteins, and omeprazole failed to affect Slug protein expression (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Collectively, our data suggest that omeprazole disrupts the interaction of Snail with CBP/p300 and eventually promotes Snail degradation.

Fig. 4. Omeprazole promotes Snail degradation by disrupting CBP/p300-mediated Snail acetylation.

a The ubiquitination level of FLAG-tagged Snail in HEK293T cells after omeprazole treatment was investigated by immunoprecipitation. b Ubiquitination assay of endogenous Snail protein in HCT116 cells treated with omeprazole. c The acetylation level of FLAG-tagged Snail in HEK293T cells treated with omeprazole. d Acetylation assay of endogenous Snail protein in HCT116 cells treated with omeprazole. e The binding interaction of exogenous Snail with CBP/p300 was evaluated in HEK293T cells treated with omeprazole. f The binding interaction of endogenous Snail with CBP/p300 was evaluated in HCT116 cells treated with omeprazole. g, h The effect of omeprazole on the association of CBP-HAT with Snail was assessed by a Streptavidin pull-down assay and quantified. All representative blots shown are from three independent experiments.

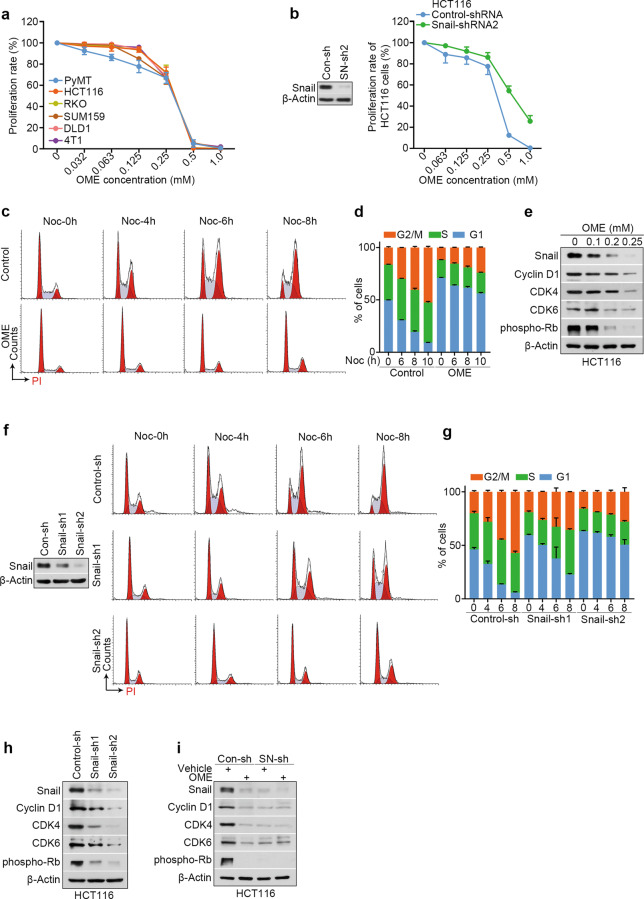

Omeprazole inhibits the proliferation of cancer cells by limiting Snail-driven cell cycle progression

Snail is also an essential regulator of tumor growth [36]. Hence, we investigated whether omeprazole affects the proliferation of cancer cells. To this end, a CCK-8 (Cell Counting Kit-8) proliferation assay was used to examine the effect of omeprazole on various cancer cells. We found that omeprazole inhibited cancer cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5a). To further evaluate whether the inhibitory effect of omeprazole on proliferation is related to Snail, we silenced Snail expression in HCT116 cells and subjected them to a proliferation assay. As shown, Snail-silenced cells were less sensitive to omeprazole treatment than control cells, suggesting that omeprazole inhibits cell proliferation by targeting Snail (Fig. 5b). To clearly elucidate the effects of omeprazole on proliferation, we performed an apoptosis assay by flow cytometry and found that omeprazole did not show significant effects on apoptosis in HCT116 and RKO cells (Supplementary Fig. S4a, b). Next, we performed cell cycle analysis by PI staining. To do this, we cultured vehicle- or omeprazole-treated HCT116 or RKO cells in the presence of the microtubule-destabilizing agent nocodazole (400 ng/ml), a widely used synchronizing agent that can inhibit growth to accumulate cells in G2-phase [37]. In the case of nocodazole treatment for the same amount of time, we observed that the proportion of G1-phase cells among omeprazole-treated cells was significantly higher than among vehicle-treated cells, indicating that omeprazole induces G1 arrest (Fig. 5c, d; Supplementary Fig. S4c, d). To investigate the changes in the cell cycle, we analyzed the expression of cell cycle-related proteins. Immunoblot analysis revealed that treatment with omeprazole led to the downregulation of G1 checkpoint-associated proteins, including cyclin D1 (CCND1), cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6), and phosphorylated Rb (p-Rb), further supporting the idea that omeprazole induces G1 arrest (Fig. 5e). Next, we compared the proportions of G1-phase cells among control and Snail-silenced cells in the presence of nocodazole. As shown, the proportion of G1-phase cells was slightly increased among HCT116 cells with moderate Snail silencing but markedly increased among cells with complete Snail silencing, suggesting that G1 arrest is Snail-dependent (Fig. 5f, g). Consistent with these findings, silencing Snail reduced the protein levels of cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, and p-Rb, and delayed cell cycle progression (Fig. 5h). To determine whether Snail is required for omeprazole-induced G1 arrest, we silenced Snail expression in HCT116 cells and subjected the cells to immunoblot analysis. As shown, omeprazole robustly reduced the protein levels of cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, and p-Rb in control cells, but failed to affect them in Snail-silenced cells (Fig. 5i). Collectively, our data indicate that omeprazole suppresses Snail-driven cell cycle progression, which consequently inhibits cancer cell growth.

Fig. 5. Omeprazole induces cell proliferation inhibition by limiting Snail-dependent cell cycle progression.

a CCK-8 cell proliferation assay of different cancer cell lines treated with omeprazole (n = 3). b CCK-8 analysis of control and Snail-silenced HCT116 cells after omeprazole treatment (n = 3). c Effect of omeprazole on the cell cycle distribution in HCT116 cells. X-axis—DNA content as measured by PI incorporation. Y-axis—cell counts for each phase of the cell cycle. d Quantitative analysis of the cell cycle distribution as described in c (n = 3). e Immunoblot analysis of Snail, Cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, and phospho-Rb in HCT116 cells treated with omeprazole. f Representative histogram of the cell cycle distribution in control cells (top) and two independent Snail-silenced HCT116 cell lines (middle and bottom). Cells were treated with nocodazole for 0, 4, 6, and 8 h before harvesting. g Quantitative analysis of the cell cycle distribution as described in f. h Immunoblot analysis of Snail, Cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, and phospho-Rb in control and two independent Snail-silenced HCT116 cell lines. i Immunoblot analysis of the indicated proteins in control and Snail-silenced HCT116 cells treated with omeprazole. All representative blots shown are from three independent experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

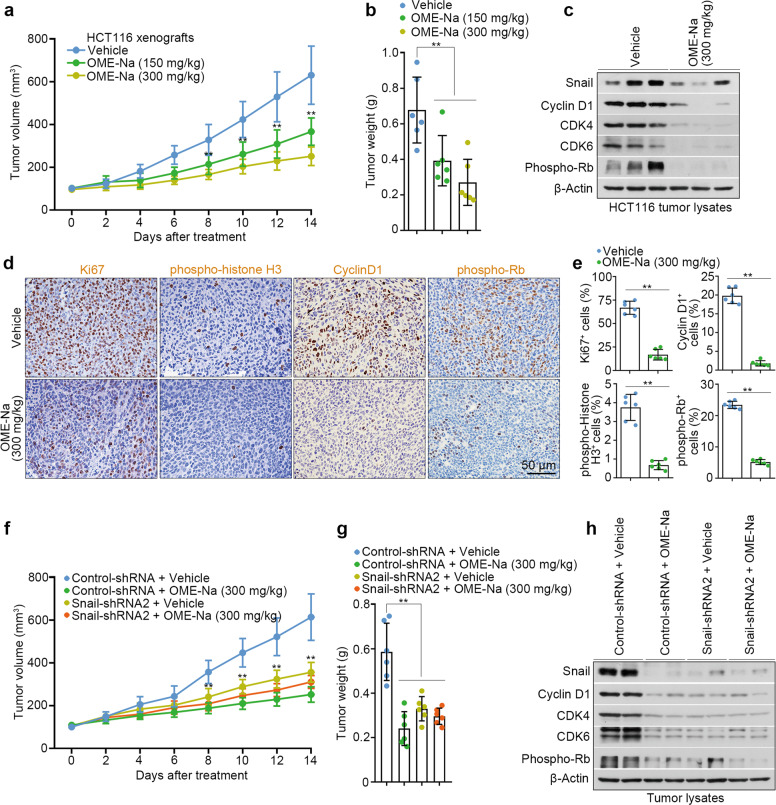

Omeprazole suppresses Snail-driven colon cancer xenograft growth

Our aforementioned results suggested the anti-proliferative activity of omeprazole in vitro. To further confirm the effects in vivo, we orally administered omeprazole (150 and 300 mg/kg/day) to HCT116 xenograft model mice. After 14 days of treatment, omeprazole efficiently inhibited xenograft tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6a, b). In addition, omeprazole did not affect the body weight or induce detectable histological changes in vital organs in tumor-bearing mice (Supplementary Fig. S5a, b). Consistent with these findings, immunoblot analysis showed that the protein levels of Snail, Cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, and p-Rb were efficiently reduced in the tumors of omeprazole-treated mice (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, omeprazole substantially decreased the percentages of proliferative (Ki67+) cells, mitotic (phospho-histone H3+, pH3+) cells, and G1-phase (cyclin D1+ and p-Rb+) cells without changing the percentage of apoptotic (cleaved caspase 3+) cells (Fig. 6d, e; Supplementary Fig. S5c, d). To examine whether the anti-proliferative effect of omeprazole is Snail-dependent in vivo, nude mice were subcutaneously implanted with 2 × 106 control or Snail-silenced HCT116 cells and treated with omeprazole for 14 days. As shown, silencing Snail resulted in a significant reduction in tumor size; omeprazole significantly reduced tumor growth in omeprazole-treated control-shRNA mice but largely failed to affect tumor growth in omeprazole-treated Snail-silenced mice, suggesting that omeprazole suppresses tumor growth by specifically targeting Snail (Fig. 6f, g). Furthermore, immunoblot analysis of xenograft tumor lysates revealed that Snail-short hairpin-mediated RNA 2 (shRNA2) significantly silenced Snail protein expression, which induced a substantial reduction in cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, and p-Rb levels (Fig. 6h). Notably, omeprazole significantly decreased Snail, cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, and p-Rb protein levels in control-shRNA tumors, but failed to affect these proteins in Snail-silenced tumors (Fig. 6h). These results collectively suggest a Snail-dependent effect of omeprazole in inhibiting xenograft tumor growth.

Fig. 6. Oral administration of omeprazole inhibits Snail-driven colon cancer xenograft growth.

Reductions in HCT116 xenograft tumor size (a) and weight (b) upon omeprazole treatment (n = 6). Mice were treated orally with omeprazole for 14 days starting when the tumor volume reached ~100 mm3. c The levels of Snail, Cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, and phospho-Rb in tumor lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting (n = 3 pools from six mice, each). d, e Immunohistochemical staining of Ki67, phospho-histone H3, Cyclin D1, and phospho-Rb in xenograft tumors; the staining intensity was quantified (n = 6). The size (f) and weight (g) of HCT116 xenograft tumors derived from control or Snail-silenced cells were monitored in mice treated orally with omeprazole for 14 days (n = 6). h Immunoblot analysis of Snail, Cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, and phospho-Rb in tumor lysates as described in f and g (n = 2 pools from six mice, each). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance and two-tailed Student’s t test were used for statistical analysis. **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle.

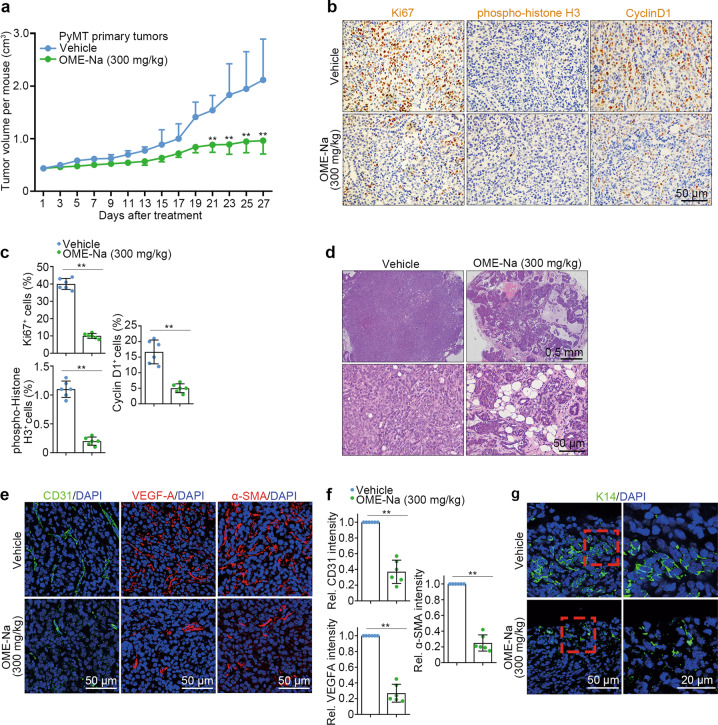

Omeprazole inhibits Snail-driven primary tumor growth in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice

To detect the anti-proliferative activity of omeprazole in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice, we measured primary tumor growth daily. As expected, omeprazole markedly inhibited primary tumor growth without eliciting toxicity in tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 7a; Supplementary Fig. S6a, b). Histological analysis revealed that omeprazole substantially decreased the percentages of Ki67+, pH 3+, and cyclin D1+ cells without changing the percentage of cleaved caspase 3+ cells (Fig. 7b, c; Supplementary Fig. S6c, d). Moreover, we examined whether omeprazole affects tumor architecture in primary breast tumors. The results showed that omeprazole-treated tumors exhibited a more differentiated phenotype at the end of the treatment period, whereas vehicle-treated tumors progressed to poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas (Fig. 7d). The tumor microenvironment plays a critical role in tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis [38]. Therefore, we tested whether omeprazole induces microenvironmental changes in primary breast tumors. As shown, omeprazole markedly reduced the infiltration of CD31+ endothelial cells, VEGFA+ (proangiogenic growth factor-expressing) cells, and α-SMA+ cancer-associated fibroblasts, suggesting that omeprazole treatment creates a suppressive tumor microenvironment (Fig. 7e, f). Cytokeratin 14 (K14) is a marker of highly migratory cancer cells, and K14+ cells can lead to collective invasion of breast tumors [39]. We found that K14+ cells were enriched at invasive borders in vehicle-treated mammary tumors, forming strands that invaded the surrounding stromal tissue, whereas omeprazole-treated mammary tumors failed to exhibit a locally invasive phenotype with almost no K14-enriched invasive strands in the stroma (Fig. 7g). Taken together, these results indicate that omeprazole strongly inhibits PyMT primary tumor growth by targeting Snail.

Fig. 7. Omeprazole inhibits mammary tumor growth in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice.

a Primary tumor growth inhibition upon omeprazole treatment in MMTV-PyMT mice (n = 6). Mice were treated orally with omeprazole for 27 days, starting when the total tumor volume reached ~400 mm3. b, c Immunohistochemical staining of Ki67, phospho-histone H3, and Cyclin D1 in primary tumors; the staining intensity was quantified (n = 6). d Representative photograph of H&E staining for the indicated primary tumors (n = 6). Magnified images of the boxed areas in the sections are shown in the bottom panels. e, f Immunofluorescence staining of CD31, VEGFA, and α-SMA in primary tumors; the staining intensity was quantified (n = 6). g Immunofluorescence staining of K14 in primary tumors (n = 6). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle.

Discussion

An increasing number of studies have reported that omeprazole exhibits remarkable anticancer properties in various cancer types [7–10]. However, its roles in the treatment of cancer remain controversial. In this report, we found that omeprazole reversed EMT progression by specifically suppressing the EMT-associated transcription factor Snail. Snail plays an essential role in the progression of cancer, and massive accumulation of Snail in the nucleus promotes tumor growth, metastasis, and recurrence. Therefore, targeting Snail is an effective strategy for cancer treatment. This study provides comprehensive evidence showing that omeprazole markedly suppresses the migration of cancer cells in vitro and impedes tumor metastasis in vivo by inhibiting the expression of the Snail protein. CBP/p300 has been demonstrated to stabilize Snail by inhibiting its polyubiquitination [34]. Based on further biochemical analyses, we proposed that omeprazole directly targets the Snail protein, thus disrupting Snail’s binding interaction with CBP/p300. Following treatment with omeprazole, the acetylation level of Snail was decreased, whereas its ubiquitination level was increased, thereby promoting Snail degradation through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. It is worth further exploring whether this strategy can lead to the development of novel Snail inhibitors with improved anticancer properties.

Clinical data have shown that chemotherapeutic drugs have a significant curative effect on many kinds of tumors; however, they are toxic, and drug resistance often develops at high doses, which is one of the important reasons for the failure of cancer chemotherapy. Recently, multiple combination therapies have been commonly used for the treatment of tumors. Preliminary evidence suggests that omeprazole can synergistically enhance the antitumor effects of Taxol, and we observed that omeprazole potently suppressed tumor growth and metastasis without eliciting toxicity in vital organs of tumor-bearing mice in vivo. Because the doses of omeprazole used in vivo exceeded the doses of omeprazole reported to date in human studies, an acute toxicity study was performed, which revealed that KM mice orally administered a single dose of omeprazole up to 4 g/kg experienced no obvious adverse health effects during a 30-day observation period, suggesting that omeprazole is safe and effective for cancer prevention and treatment. However, further clinical investigations are required to compare omeprazole monotherapy and combination treatment.

Disruption of normal cell cycle function is a new target for the treatment of tumors [40, 41]. Cell cycle progression is regulated by several cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) that act in complex with cyclins [42]. Cells produce cyclin D1, which forms an activating complex with CDK4/6 [43]. The cyclin D1-CDK4/6 complex then promotes the phosphorylation of Rb and drives cell cycle progression from G1 phase to S phase [44]. Of note, our results showed that omeprazole reduced cyclin D1, CDK4/6, and p-Rb protein levels, which led to pronounced G1 arrest. In addition, we observed a marked decrease in G1 checkpoint-associated protein expression in Snail-silenced cells. Consistent with these findings, reduced levels of G1 checkpoint-associated mRNAs were observed in the absence of Snail. Although omeprazole decreased the formation of the cyclin D1-CDK4/6 complex, it failed to affect cyclin D1-CDK4/6 expression in Snail-silenced cells. Based on these observations, we concluded that omeprazole interferes with the formation of the cyclin D1-CDK4/6 complex and inhibits Rb protein phosphorylation to block the G1/S transition by targeting Snail. However, the potential molecular mechanisms by which Snail regulates the cyclin D1-CDK4/6 complex need to be further clarified. CDK4/6 inhibitors exhibit marked clinical activity in oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative advanced and metastatic breast cancers as first-line therapy [45, 46]; however, drug resistance is frequently encountered and poorly understood [47, 48]. Recent studies have reported that patients who receive CDK4/6 inhibitors usually experience disease recurrence within 1–3 years after therapy [49–51]. In addition, a number of studies have shown the essential role of CDK6 in drug sensitivity; for example, knockdown of CDK6 restored drug sensitivity, and forced overexpression of CDK6 was sufficient to mediate drug resistance [49]. Because omeprazole markedly suppressed CDK4/6 expression, the data raise the possibility that the combination of omeprazole and CDK4/6 inhibitors, with even greater potency against tumors, might be of clinical interest, particularly in the setting of overcoming drug resistance.

In summary, our study shows that omeprazole directly targets the Snail protein, thus disrupting CBP/p300-mediated Snail acetylation and then promoting Snail degradation through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Omeprazole suppresses Snail-driven EMT and reduces EMT-associated tumor invasion and metastasis. Omeprazole also inhibits tumor growth by limiting Snail-dependent cell cycle progression. Overall, our data reveal the underlying mechanisms responsible for the anticancer activity of omeprazole and strongly suggest that omeprazole may be an excellent auxiliary drug for treating patients with malignant tumors.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973363 and 82125036), the State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines of China Pharmaceutical University (SKLNMZZCX202015), the Jiangsu Association for Science and Technology “Yong Talent Support Project”, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author contributions

ZQW and RF conceived the project, designed the experiments, and interpreted the data. YL and BXR performed the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript with help from HML. TL analyzed data and provided relevant advice.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Yang Li, Bo-xue Ren

Contributor Information

Rong Fu, Email: furong@cpu.edu.cn.

Zhao-qiu Wu, Email: zqwu@cpu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-021-00787-1.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson BO, Cazap E, El Saghir NS, Yip CH, Khaled HM, Otero IV, et al. Optimisation of breast cancer management in low-resource and middle-resource countries: executive summary of the Breast Health Global Initiative consensus, 2010. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:387–98. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van’t Veer LJ, Weigelt B. Road map to metastasis. Nat Med. 2003;9:999–1000. doi: 10.1038/nm0803-999b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Der G. An overview of proton pump inhibitors. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2003;26:182–90. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200309000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin JM, Kim N. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the proton pump inhibitors. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:25–35. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeo M, Kim DK, Kim YB, Oh TY, Lee JE, Cho SW, et al. Selective induction of apoptosis with proton pump inhibitor in gastric cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8687–96. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Udelnow A, Kreyes A, Ellinger S, Landfester K, Walther P, Klapperstueck T, et al. Omeprazole inhibits proliferation and modulates autophagy in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Milito A, Iessi E, Logozzi M, Lozupone F, Spada M, Marino ML, et al. Proton pump inhibitors induce apoptosis of human B-cell tumors through a caspase-independent mechanism involving reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5408–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin UH, Michelhaugh SK, Polin LA, Shrestha R, Mittal S, Safe S. Omeprazole inhibits glioblastoma cell invasion and tumor growth. Cancers. 2020;12:2097. doi: 10.3390/cancers12082097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nieto MA. The snail superfamily of zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:155–66. doi: 10.1038/nrm757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiery JP, Sleeman JP. Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:131–42. doi: 10.1038/nrm1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, et al. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batlle E, Sancho E, Francí C, Domínguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, et al. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–9. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cano A, Pérez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, et al. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ni T, Li XY, Lu N, An T, Liu ZP, Fu R, et al. Snail1-dependent p53 repression regulates expansion and activity of tumour-initiating cells in breast cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:1221–32. doi: 10.1038/ncb3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu ZQ, Rowe RG, Lim KC, Lin Y, Willis A, Tang Y, et al. A Snail1/Notch1 signalling axis controls embryonic vascular development. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3998. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nieto MA. Epithelial plasticity: a common theme in embryonic and cancer cells. Science. 2013;342:1234850. doi: 10.1126/science.1234850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tam WL, Weinberg RA. The epigenetics of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:1438–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin UH, Lee SO, Pfent C, Safe S. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand omeprazole inhibits breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:498. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Craene B, Berx G. Regulatory networks defining EMT during cancer initiation and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:97–110. doi: 10.1038/nrc3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhuang X, Zhang H, Li X, Li X, Cong M, Peng F, et al. Differential effects on lung and bone metastasis of breast cancer by Wnt signalling inhibitor DKK1. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:1274–85. doi: 10.1038/ncb3613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin EY, Jones JG, Li P, Zhu L, Whitney KD, Muller WJ, et al. Progression to malignancy in the polyoma middle T oncoprotein mouse breast cancer model provides a reliable model for human diseases. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2113–26.. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63568-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckhardt BL, Parker BS, van Laar RK, Restall CM, Natoli AL, Tavaria MD, et al. Genomic analysis of a spontaneous model of breast cancer metastasis to bone reveals a role for the extracellular matrix. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:1–13. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.1.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lelekakis M, Moseley JM, Martin TJ, Hards D, Williams E, Ho P, et al. A novel orthotopic model of breast cancer metastasis to bone. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:163–70.. doi: 10.1023/A:1006689719505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin UH, Karki K, Kim SB, Safe S. Inhibition of pancreatic cancer Panc1 cell migration by omeprazole is dependent on aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation of JNK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;501:751–757. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin UH, Kim SB, Safe S. Omeprazole inhibits pancreatic cancer cell invasion through a nongenomic aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway. Chem Res Toxicol. 2015;28:907–18. doi: 10.1021/tx5005198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin UH, Lee SO, Safe S. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR)-active pharmaceuticals are selective AHR modulators in MDA-MB-468 and BT474 breast cancer cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343:333–41. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.195339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rico-Leo EM, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Fernandez-Salguero PM. Dioxin receptor expression inhibits basal and transforming growth factor β-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7841–7856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.425009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai DW, Liu SH, Karlsson AI, Lee WJ, Wang KB, Chen YC, et al. The novel Aryl hydrocarbon receptor inhibitor biseugenol inhibits gastric tumor growth and peritoneal dissemination. Oncotarget. 2014;5:7788–804. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu DS, Wang HJ, Tai SK, Chou CH, Hsieh CH, Chiu PH, et al. Acetylation of snail modulates the cytokinome of cancer cells to enhance the recruitment of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:534–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu ZQ, Li XY, Hu CY, Ford M, Kleer CG, Weiss SJ. Canonical Wnt signaling regulates Slug activity and links epithelial-mesenchymal transition with epigenetic Breast Cancer 1, Early Onset (BRCA1) repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:16654–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205822109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheon MG, Kim W, Choi M, Kim JE. AK-1, a specific SIRT2 inhibitor, induces cell cycle arrest by downregulating Snail in HCT116 human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:637–45. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zieve GW, Turnbull D, Mullins JM, McIntosh JR. Production of large numbers of mitotic mammalian cells by use of the reversible microtubule inhibitor nocodazole. Nocodazole accumulated mitotic cells. Exp Cell Res. 1980;126:397–405. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(80)90279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balkwill FR, Capasso M, Hagemann T. The tumor microenvironment at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5591–6. doi: 10.1242/jcs.116392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheung KJ, Gabrielson E, Werb Z, Ewald AJ. Collective invasion in breast cancer requires a conserved basal epithelial program. Cell. 2013;155:1639–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santo L, Siu KT, Raje N. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases and cell cycle progression in human cancers. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:788–800. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whittaker SR, Mallinger A, Workman P, Clarke PA. Inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases as cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;173:83–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malumbres M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 2014;15:122. doi: 10.1186/gb4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roskoski R., Jr Cyclin-dependent protein serine/threonine kinase inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Pharmacol Res. 2019;139:471–88. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narasimha AM, Kaulich M, Shapiro GS, Choi YJ, Sicinski P, Dowdy SF. Cyclin D activates the Rb tumor suppressor by mono-phosphorylation. Elife. 2014;3:e02872. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dickler MN, Tolaney SM, Rugo HS, Cortés J, Diéras V, Patt D, et al. MONARCH 1, a phase II study of abemaciclib, a CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitor, as a single agent, in patients with refractory HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5218–5224. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, Boer K, Bondarenko IM, Kulyk SO, et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:25–35. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herrera-Abreu MT, Palafox M, Asghar U, Rivas MA, Cutts RJ, Garcia-Murillas I, et al. Early adaptation and acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2301–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konecny GE, Winterhoff B, Kolarova T, Qi J, Manivong K, Dering J, et al. Expression of p16 and retinoblastoma determines response to CDK4/6 inhibition in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1591–602.. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Z, Razavi P, Li Q, Toy W, Liu B, Ping C, et al. Loss of the FAT1 tumor suppressor promotes resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors via the hippo pathway. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:893–905. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Condorelli R, Spring L, O’Shaughnessy J, Lacroix L, Bailleux C, Scott V, et al. Polyclonal RB1 mutations and acquired resistance to CDK 4/6 inhibitors in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:640–645. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Leary B, Cutts RJ, Liu Y, Hrebien S, Huang X, Fenwick K, et al. The genetic landscape and clonal evolution of breast cancer resistance to palbociclib plus fulvestrant in the PALOMA-3 trial. Cancer Disco. 2018;8:1390–403. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.