Abstract

Reconstruction of eyelid defects, especially the posterior lamella, remains challenging because of its anatomical complexity, functional considerations, and aesthetic concerns. The goals of eyelid reconstruction include restoring eyelid structure and function and achieving an aesthetically acceptable appearance. An in-depth understanding of the complex eyelid anatomy and several reconstructive principles are mandatory to achieve these goals. Currently, there are multiple surgical treatment options for eyelid reconstruction, including different flaps, grafts, and combinations of them. This comprehensive review outlines the principles of reconstruction and discusses the indications, advantages, and disadvantages of currently available surgical techniques. We also propose our clinical thinking for solving specific clinical questions in eyelid reconstruction and offer perspectives on new potential methodologies in the future.

Keywords: Anterior lamella, Eyelid defect, Eyelid reconstruction, Periocular reconstruction, Posterior lamella, Tarsus

Key Summary Points

| The goals of eyelid reconstruction include restoring eyelid structures and functions and achieving a cosmetically acceptable appearance with minimal surgical morbidity, which present a great challenge for surgeons |

| Making accurate etiological, functional, and anatomical/pathological diagnoses for the defects is critical for designing a plan for eyelid reconstruction |

| For optimal outcomes, the reconstructive strategy should be well planned based on the reconstructive ladder principles and defect characteristics, including defect thickness, size, and location |

| Due to the limitations of current surgical techniques and the rapid development of tissue engineering, the methodology of eyelid reconstruction, especially posterior lamella reconstruction, will transform from a replacement strategy to a regenerative strategy |

Introduction

Reconstruction of eyelid defects caused by tumors, trauma, burns, and congenital factors remains a significant challenge in plastic and reconstructive surgery due to its anatomical complexity, functional considerations, and aesthetic concerns. Although numerous techniques have been described in the literature over the past decades, current clinically available techniques for eyelid reconstruction are essentially a replacement strategy [1]. Specifically, the first step is to identify whether the defect involves the anterior lamellar, the posterior lamellar, or both. Then, corresponding substitutes are used to replace the missing layers. The replacements for the anterior lamella mainly include skin grafts and local random flaps, while those for the posterior lamella mainly include free autografts and tissue flaps. Here, we summarize the general principles and review current surgical techniques for eyelid defect reconstruction. All data presented in this article were gathered following approval from the local research ethics committee.

Surgical Anatomy of the Eyelids

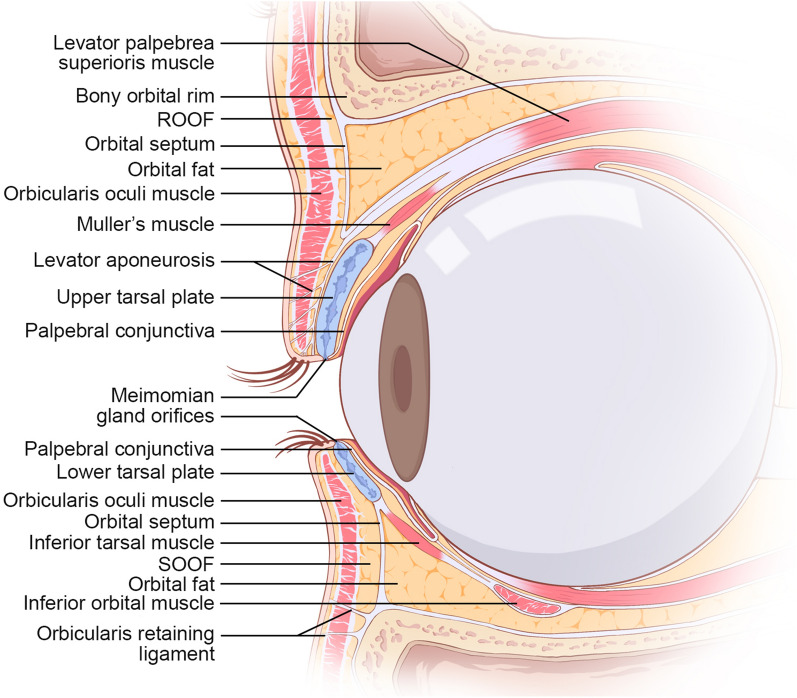

An in-depth understanding of eyelid anatomy is essential for surgical planning and preventing complications. The eyelids are essentially bilamellar structures comprising the anterior and posterior lamella (Fig. 1). The anterior lamella includes the skin and orbicularis muscle. Eyelid skin is the thinnest of all body skin and lacks subcutaneous fat, which has high elasticity and facilitates motility. The orbicularis muscle, consisting of pretarsal, preseptal, and orbital subunits, is responsible for eyelid closure. The posterior lamella comprises the tarsal plate and palpebral conjunctiva. The tarsus is a unique transitional tissue that features both dense fibrous connective tissue and cartilage tissue, which consists mainly of fibroblasts surrounded by extracellular matrix (ECM) and abundant meibomian glands. The tarsus is approximately 25 mm long and 1 mm thick, and the tarsal height varies from 8 to 12 mm in the upper eyelid to 4–5 mm in the lower eyelid [2]. The conjunctiva comprises overlying stratified and nonkeratinized epithelium with interspersed, secretory active goblet cells resting on a vascularized basement membrane. It can spontaneously re-epithelialize upon injury. The palpebral conjunctiva connects tightly to the tarsus and provides additional lubrication for the cornea and globe that facilitates eyeball movement and reduces friction.

Fig. 1.

Anatomical structures of upper and lower eyelids. ROOF retro-orbicularis oculi fat, SOOF sub-orbicularis oculi fat

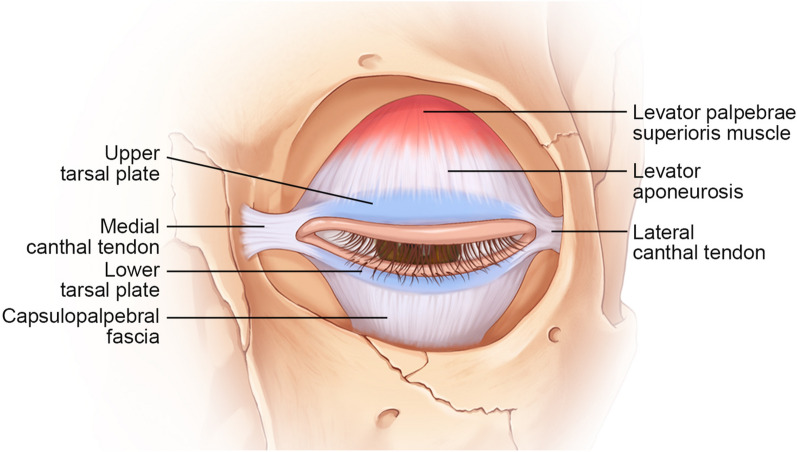

The primary supports of the eyelids are the medial and lateral canthal tendons, which attach to the tarsi and provide anterior-posterior stability to the eyelids as the tarsoligamentous sling. The medial canthus attaches to the anterior and posterior lacrimal crest. The lateral canthus attaches posterior to the lateral orbital rim at Whitnall’s tubercle. Vertical stabilization is provided to the upper eyelid by the levator aponeurosis (attaches to the superior tarsus) and to the lower eyelid by the retractors (attaches to the superior tarsus) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Supporting system of upper and lower eyelids

General Reconstructive Principles

The goals of eyelid reconstruction include restoring eyelid structures and functions, achieving a cosmetically acceptable appearance with minimal surgical morbidity, and, more importantly, maintaining ocular surface homeostasis to prevent visual impairment [3, 4]. To achieve these goals, the reconstructive strategy should be well planned based on reconstructive ladder principles and defect characteristics. According to the reconstructive ladder principles, the surgeon should take the simplest approaches and use “like” tissues to restore both function and cosmetic appearance as much as possible. Typically, an ideal method for eyelid reconstruction should have the following characteristics: (1) good contact without irritation to the bulbar conjunctiva and cornea; (2) supportability, particularly in the lower eyelids; (3) applicability to various types of defects; (4) easy performance; (5) minimal damage to the donor site [5].

Furthermore, reconstruction plans should be designed according to the defect characteristics, including the defect thickness, size, and location. First, the thickness of the defect determines which structure needs to be reconstructed. Partial-thickness defects only involve the anterior lamellar. Isolated anterior lamellar defects may need not only skin coverage but also orbicularis muscle reconstruction. The defects involving the posterior lamella are usually full-thickness defects, which require reconstruction of the two lamellae separately, and at least one lamella should provide blood supply. Second, the size of the defect determines how much tissue is needed. Defects that are < 25% of the lid can be closed primarily depending on the skin laxity. However, defects that are > 20–30% of the eyelid usually require free tissue grafts or flaps for reconstruction [6]. For full-length eyelid defects with complete tarsus loss, combinational techniques are often considered. Third, the location of the defect may require surgeons to take some special structures into consideration. For instance, surgeons repairing defects in the medial canthal area should carefully evaluate the function of the lacrimal system. Full mobility is crucial for the upper eyelid but is less important for the lower eyelid. However, maintenance of a static position that will contact the upper eyelid upon closure is necessary.

Anterior Lamellar Defects

Small (< 25% of the eyelid) and superficial anterior lamellar defects are often closed directly or left alone for secondary healing. For large defects involving the skin and potentially the underlying orbicularis muscle, skin grafts or flaps are often preferred. The reconstruction of anterior lamellar defects should (1) use thin and pliable skin with optimal color and texture matching, (2) place incisions in natural lid lines, and (3) distribute horizontal tension at the lid margins and vertical tension at the lateral or medial canthal regions. Table 1 shows a summary of the techniques for anterior lamellar reconstruction.

Table 1.

Techniques for anterior lamellar defect reconstruction

| Technique | Indications | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grafts | |||

| FTSG | Simple skin defect with healthy orbicularis base | Ease; minor donor site morbidity; no dimension limitation | Relatively high rates of graft contraction and hypertrophy |

| Local random flap | |||

| V–Y advancement flap | Deep, small defects located along the nasal sidewall | Ease; “like for like” reconstruction | Requirement of great skin laxity; vertically scar across the skin tension line; high vertical tension that may cause entropion |

| Rhomboid transitional flap | Mild medial and lateral canthal defects | Ease; minor donor site morbidity; “like for like” reconstruction | Requirement of great skin laxity |

| Mustarde cheek rotational flap | Deep, vertical defects of the entire lower eyelid | Single-stage procedure; large flap size; reliable blood supply | Relatively high thickness for eyelid; invasive procedure; risk of facial nerve lesion |

| Tripier flap | Entire lower eyelid defects | Use of excess upper eyelid orbicularis and skin; long flap length; less bulky | Limited vertical size, possible unreliability of the distal part of the unipedicled flap |

| Fricke flap | Entire upper and lower eyelid, lateral canthal defects | Long flap length | Two-stage procedure; excessive thickness for eyelid; limited vertical size; risk of frontal branch lesion; possible eyebrow elevation; possible unreliability of the distal part of the flap |

| Axial flap | |||

| Frontal flap based on STA | Entire upper and lower eyelid, and lateral canthal defects | No dimension limitation; possibility of dissection into island flap | Two-stage procedure; necessity of good surgical skills; skin grafting required to repair donor site; possible eyebrow elevation; unreliable venous outflow |

| Forehead flap based on supratrochlear artery | Entire upper and lower eyelid, and medial canthal defects | No dimension limitation, reliable blood supply | Two-stage procedure; necessity of good surgical skills; excessive thickness for upper eyelid |

| Nasolabial flap based on angular artery | Entire upper and lower eyelid, and medial canthal defects | No dimension limitation, excellent color and texture matching; minor donor site morbidity; provision of eyelid-cheek transition | Potentially compromised blood supply; risk of ectropion |

Full-Thickness Skin Graft (FTSG)

FTSG is suitable for simple anterior lamellar defects with a healthy orbicularis base [7, 8] or for use in combination with vascularized posterior lamellar replacements for bilamellar defects [9, 10]. Aesthetically, skin tissues from the ipsilateral or contralateral eyelid, retroauricular, inner brachial, and supraclavicular areas that provide similar color, thickness, and texture are considered ideal donor sites for the periocular region [11]. Hypertrophic scarring is the most common complication and can be reversed by massage, steroid ointment, and silicone gel application [12].

Local Random Flaps

Local random flaps have shown superior functional and aesthetic outcomes compared with FTSGs because of superior color and texture matching, a better blood supply, and reduced scarring. According to the repositioning method of the flaps, local random flaps can be categorized as advancement and rotational flaps. Advancement flaps are suitable for small to medium defects but unfeasible for defects greater than 80% of the upper eyelid because of the limited excess skin. Compared with advancement flaps, rotational flaps can be designed contiguous to the defect or at some distance away and are therefore more suitable for large defects of up to the whole length of the eyelid.

V–Y Advancement Flap

The V–Y advancement flap is a subcutaneous island pedicle flap and is commonly used to reconstruct anterior lamellar defects located along the nasal sidewall extending into the medial canthus and even the entire lower eyelid [13–15]. This flap is also modified to repair upper eyelid defects [16]. Typically, the V–Y advancement flap is designed as a triangular island positioned parallel to or within the nasolabial fold with the width of the flap equal to the width of the defect. The flap is then advanced vertically to the defect area based on the subcutaneous muscular pedicle. The V–Y flap requires less dissection and operation time, but advancement of the flap results in a vertical scar across the relaxed skin tension line, which can cause postoperative ectropion, especially on the lower eyelid. This flap has been modified to follow a horizontal orientation to minimize the risk of postoperative lower lid mispositioning [17–19].

Rhomboid Rotational Flap

The rhomboid rotational flap offers a versatile approach to the repair of periocular defects, particularly for medial and lateral canthal defects [20]. The classic rhomboid flap is designed in a rhombus shape with internal angles of 60° or 120°. The flap is then repositioned for defect repair, and the final closures of these flaps can be hidden in the glabellar folds, eyelid crease, or medial or lateral canthal angles. The design of this flap should follow the principles of horizontal tension distribution at the lid margins and vertical tension at the lateral and medial canthal regions to avoid canthal height distortion [21]. However, most periocular defects are circular or ovoid, and these defects can be conceptualized in a rhomboid shape and treated with modified rhomboid flaps [22].

Mustarde Cheek Rotational Flap

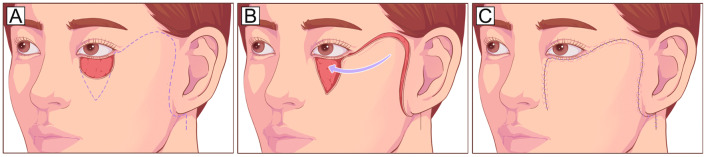

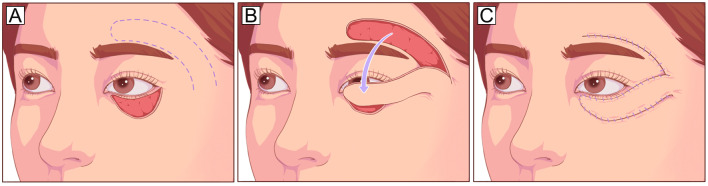

The Mustarde cheek rotational flap recruits skin tissue from the lateral cheek and preauricular area and is suitable for repairing deep vertical defects involving up to the entire anterior lamella of the lower eyelid in a single-stage procedure, especially if the vertical dimension of the defect is greater than the horizontal dimension (Fig. 3). Appropriate techniques to anchor or suspend the cheek flap to the lateral canthus or periosteum [23] or to sling it with a dermis-fat flap [24] are also necessary. The Mustarde flap is a reliable and versatile technique with a large donor area and sufficient blood supply [25, 26]. However, the cheek skin is relatively thick for the eyelid. In addition, it is a comparatively invasive procedure and may cause facial nerve injury.

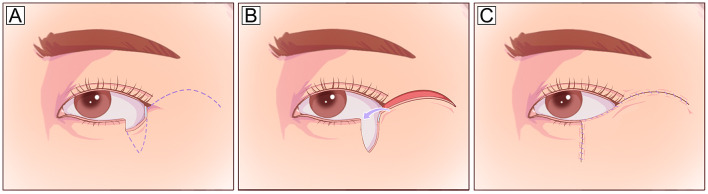

Fig. 3.

Mustarde cheek rotational flap. A Large vertical anterior lamella defect of the lower eyelid defect and planned incision design (dotted line). The incision runs laterally from the level of the lower eyelid and lateral canthus, superiorly into the temporal skin, and finally inferiorly toward the preauricular areas. B, C The flap is undermined in the subcutaneous or SMAS plane and rotated medially to cover the defect. To reduce the tension in the lid-cheek margin and avoid postoperative ectropion, the flap should be designed along the natural curve of the lower eyelid with a high takeoff from the lateral canthus to the temple before curving inferiorly. SMAS, superficial muscular aponeurotic system

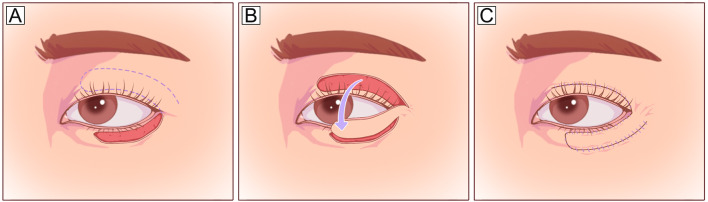

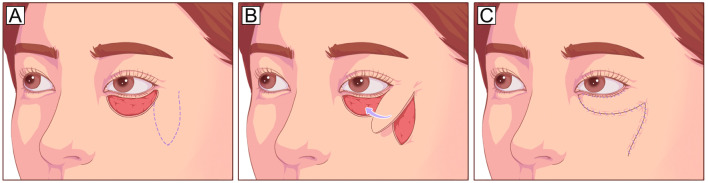

Tripier Orbicularis Myocutaneous Flap

The Tripier orbicularis myocutaneous flap is harvested from the upper eyelid and transposed to the lower lid as a unipedicled or bipedicled flap. A unipedicled flap can be used to repair defects involving 1/3–1/2 of the lower eyelid (Fig. 4), and a bipedicled flap can be used for total lower eyelid defects [27, 28]. This flap has been modified to an island Tripier flap for aesthetic reconstruction of subtotal defects away from the lateral canthus and a reverse Tripier flap for upper eyelid reconstruction [29]. This procedure uses the excess upper eyelid orbicularis and skin but has a limited size, particularly in the vertical dimension [30].

Fig. 4.

Tripier orbicularis myocutaneous flap (unipedicled). A Anterior lamellar defect involving 2/3 of the lower eyelid and planned incision design on the upper eyelid (dotted line). B The flap is elevated under the orbicularis muscle plane and pedicled on the orbicularis muscle laterally. C The flap is transposed inferiorly to cover the defect

Fricke Forehead/Cheek Flap

The Fricke forehead flap is a temporally based unipedicled transposition flap that can be used in the reconstruction of large lower and upper eyelid defects and lateral canthal defects [31] (Fig. 5). It is particularly useful when the defect involves the entire lower eyelid but with a relatively short height [32]. However, this two-stage operation may injure the frontal branch of the facial nerve and often result in eyebrow level elevation, upper eyelid malposition, and even lagophthalmos, which requires additional tissue recruitment for correction to prevent exposure keratitis [33]. A modification of this flap is harvesting the flap from the cheek instead of the forehead (Fricke cheek flap, Fig. 6), which offers a larger amount of available tissue and avoids the elevation of the eyebrow [34].

Fig. 5.

Fricke forehead flap. A Large lateral lower eyelid defect with long horizontal length and short vertical height and planned incision design on the forehead. The flap design should obey a width-to-length ratio of 1:2 to ensure blood supply to the flap tip. B, C The flap is elevated as a random cutaneous flap and rotated inferiorly to cover the defect

Fig. 6.

Fricke cheek flap. A Large anterior lamella defect involving the entire length of the lower eyelid and planned incision design on the cheek. B, C The flap is undermined in the orbicularis muscle plane and rotated superiorly to cover the defect

Axial Flaps

Axial flaps can be designed much larger than random flaps. Thus, they are more suitable for the reconstruction of large eyelid defects. However, these techniques require superb surgical skills for dissecting the perforators to avoid flap congestion and subsequent sequelae at the donor site [35, 36].

Frontal Flap Based on the Frontal Branch of the Superficial Temporal Artery (FBSTA)

The FBSTA-based frontal flap is similar to the Fricke flap but vascularized by a perforator of the FBSTA, which allows a significant supply of cutaneous tissue for covering defects of the upper or lower eyelid and the lateral canthal area [37, 38]. This flap can be dissected into an island flap based on a perforator [38, 39], which allows elevation of a thin flap for eyelid reconstruction within a single surgery. A bilobed island flap, which is composed of two FBSTA perforator-based island flaps or a tulip-shaped flap, has been used to reconstruct lateral canthus defects involving both the upper and lower eyelids and even the eyebrows [40].

Forehead Flap Based on the Supratrochlear Artery (STA)

The STA-based forehead flap is a workhorse for the reconstruction of intermediate-sized periorbital defects [41], especially those associated with nasal defects. This flap closely matches the eyelid pigmentation but is too bulky for periocular reconstruction. Anatomically, the STA emerges from the ophthalmic artery and travels superomedially under the orbicularis oculi muscle. The STA provides a consistent cutaneous branch in a position 1.18 ± 0.36 cm distal to the supraorbital rim [42], which allows the forehead flap to be trimmed as an ultrathin flap from 2 cm superior to the orbit and modified into an islanded flap [43] or tunneled flap [44] to conform to the complex landscape around the orbit.

Nasolabial Flap Based on the Angular Artery

The angular artery-based nasolabial flap is well suited for repairing moderate to large defects of the lower eyelid and medial canthal area [45]. The angular artery mainly originates from either the ophthalmic artery or the infraorbital artery and travels along the nasolabial fold [46], which allows the flap to be dissected as a superiorly pedicled nasolabial flap. The advantages of this flap include (1) easy flap dissection; (2) excellent color and texture matching; (3) provision of an eyelid-cheek transition; (4) minor donor morbidity [47, 48]. However, the potentials for compromised flap blood supply, ectropion, and lagophthalmos are the main limitations of this technique [49].

Posterior Lamellar Defects and Full-Thickness Defects

Reconstruction of posterior lamellar defects requires a layer of dense tissue with similar mechanical strength to the native tarsus to provide primary support to the eyelid and a layer of soft tissue with a similar structure to the native conjunctiva to provide additional lubrication to the globe. Direct closure is preferable for defects of < 25% of the eyelid length. When the defect involves 25–50% of the eyelid, the use of local tarsoconjunctival flaps or cantholysis can achieve primary closure. When the defects involve up to 50% of the eyelid, free autografts, tissue flaps, or combinational techniques are often needed. When the anterior lamella provides sufficient vascular support, posterior lamellar defects can be repaired by free autografts. In contrast to free autografts, tissue flaps repair posterior lamellar defects in the form of vascularized tissues, which allows for replacement of the anterior lamella with an FTSG, local flaps, or switch flaps in full-thickness eyelid defects. Table 2 shows a summary of techniques for posterior lamella and full-thickness reconstruction.

Table 2.

Techniques for posterior lamella and full-thickness defect reconstruction

| Reconstructive methods | Indications | Main advantages | Main disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free autografts | |||

| Tarsoconjunctival graft | Defects up to 75% of lower lid | “Like for like” reconstruction | Limited donor site; donor site morbidity; graft shrinkage |

| Tarsomarginal graft | Defects involving 1/4–3/4 of upper or lower eyelid | “Like for like” reconstruction; preservation of eyelash and eyelid margin; allows sequential grafting | Limited donor site; donor eyelid; risk of eyelid retraction |

| HPM graft | Defects involving 1/2 to total of upper or lower eyelid | Hidden donor site, tissue structure matching | Cornea irritation due to the keratinized epithelium; donor site morbidity; pain |

| Nasal chondromucosal graft | Defects involving 1/2 to total of upper or lower eyelid | No dimension limitation; a combination of cartilage and mucosa, hidden donor site | Donor site morbidity; risk of perforation and hemorrhage |

| Auricular cartilage graft | Defects involving 1/2 to total of upper or lower eyelid | No dimension limitation; easy to harvest, minor donor site morbidity; low contraction rate | Cornea irritation due to lack of lining tissue, stiffness |

| Tissue flaps | |||

| Local tarsoconjunctiva flap | Upper and lower eyelid defects less than 60% of the horizontal eyelid length | “Like for like” reconstruction; single-stage procedure | Limited donor site |

| Hughes flap | Defect involving 1/2 to total of lower eyelid | “Like for like” reconstruction | Two-stage procedure; donor eyelid morbidity; longtime of vision occlusion |

| Reversed Hughes flap | Defect involving 1/2 to total of upper eyelid | “Like for like” reconstruction | Two-stage procedure; donor eyelid morbidity; longtime of vision occlusion |

| Cutler-Beard flap | Defect involving 1/2 to total of upper eyelid | “Like for like” reconstruction | Two-stage procedure; donor eyelid morbidity; longtime of vision occlusion; requirement of tarsal substitutes; risk of lower lid entropion |

| Tenzel flap | Full-thickness defects involving 1/2–2/3 of lower or upper eyelid margin | Full-thickness reconstruction; single-stage procedure; minor donor site morbidity; preservation of eyelid margin with eyelashes | Requirement of temporal skin laxity; requirement of posterior coverage |

| Mustarde lower lid sharing flap | Full-thickness defects involving 30–60% of upper eyelid margin | Full-thickness reconstruction; preservation of eyelid margin with eyelashes | Two-stage procedure; risk of lower lid entropion |

Free Autografts

Tarsoconjunctival or Tarsal Graft

The tarsoconjunctival grafts taken from healthy eyelids are the gold standard tissue for posterior lamellar reconstruction [50] and have been used to repair defects of up to 75% of the eyelid length [51, 52]. Typically, the size of the donor tarsoconjunctival graft ranges from 4 to 5 mm vertically and 8–16 mm horizontally, and preservation of at least 4 mm of the tarsus is recommended to avoid complications. Tarsal grafts can be regarded as tarsoconjunctival grafts without the conjunctival lining. Free tarsoconjunctival grafts or tarsal grafts are often used in combination with other tissue flaps to provide a blood supply for the grafts in full-thickness defects [51, 53, 54]. When free tarsal grafts are used for posterior lamellar reconstruction, the conjunctival lining is often absent, leaving it to be gradually re-epithelialized from the marginal conjunctiva. The main limitations are donor eyelid morbidity, small graft size, and possible corneal irritation requiring a mucus membrane graft to protect the ocular surface [55].

Tarsomarginal Graft

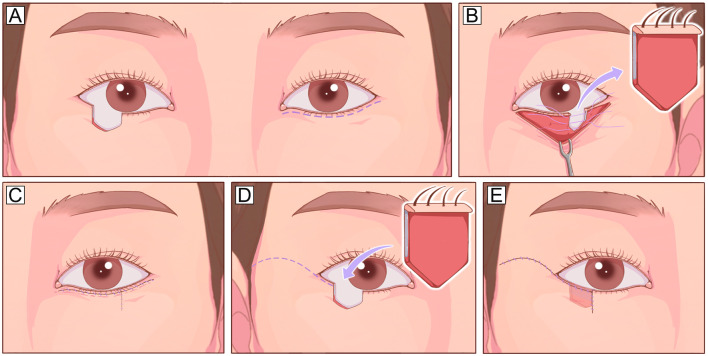

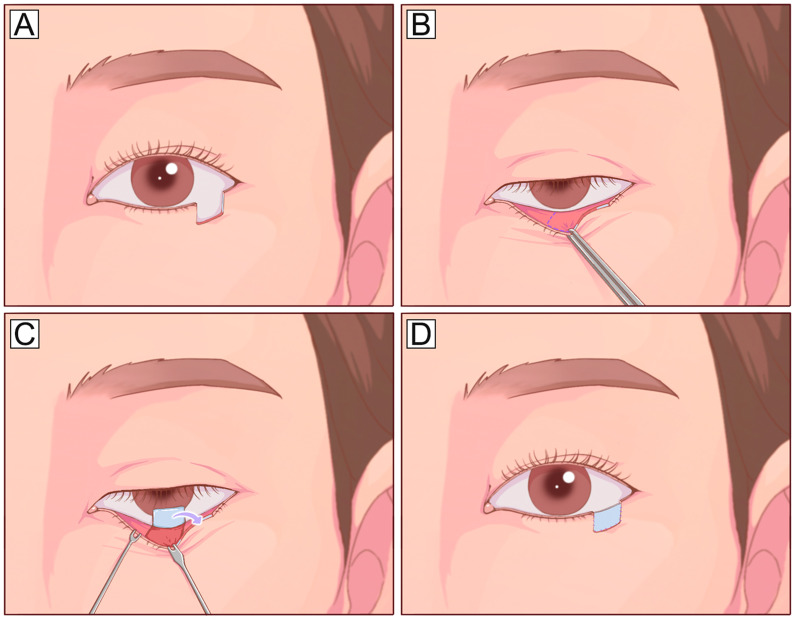

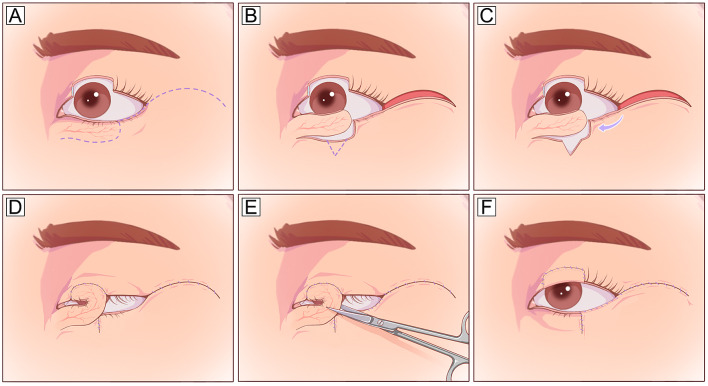

The tarsomarginal grafts are composite grafts consisting of tarsus, conjunctiva, eyelashes, and eyelid margins (Fig. 7). Typically, one-quarter or occasionally even one-third of the donor eyelid can be harvested with primary closure, and sequential grafts can be used for larger defects involving 1/4–3/4 of the upper or lower eyelid [56]. Tarsomarginal grafts are ideal autografts for posterior lamellar reconstruction because they retain the normal physiological structures of the eyelid margin, although the eyelash survival rate varies greatly. Scar formation and eyelid retraction are the main complications, and revision surgery is occasionally required [56].

Fig. 7.

Tarsomarginal graft. A A full-thickness defect with a half-length of the entire lower eyelid. B A planned incision is designed 2 mm inferior to the eyelid margin. C The myocutaneous flap is dissected to expose the posterior lamella, and a tarsomarginal graft with a length half of the defect is harvested. D The donor eyelid can be closed with primary closure. E, F The full-thickness lower eyelid defect is reconstructed using two different techniques: the posterior lamella defect is repaired with the harvested tarsomarginal graft, and the anterior lamella defect is closed with a local Tenzel flap

Hard Palatal Mucoperiosteal (HPM) Graft

The HPM grafts have both fibrous connective tissue and a mucosal surface that is histologically similar to the tarsoconjunctiva [57]. HPM grafts can provide good and lasting structural support to the eyelids, making them an optimal choice for repairing posterior lamellar defects [58, 59]. However, HPM is a tissue structured with keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, and orthokeratosis may persist for years following transplantation, which may irritate the cornea. Thus, the application of HPM grafts in upper eyelid reconstruction remains controversial, especially when the eyelid defect is adjacent to the middle part of the cornea [58]. In addition, the donor site of the HPM graft is typically left alone for secondary healing, which results in donor site discomfort, possible hemorrhage, and feeding difficulties.

Nasal Chondromucosal Graft

The nasal chondromucosal grafts harvested from the nasal septum [32, 60–62] or ala [63, 64] can offer both support and lining for replacing the tarsus and conjunctiva. The septal mucochondral graft tends to curl toward the mucosa-covered side after thinning of the cartilage, which matches the shape of the tarsus and can provide good eyelid stability and aesthetic outcomes [65, 66]. The donor site of septal chondromucosal grafts is typically left with nasal packing for secondary healing, which may result in septal perforation and hemorrhage [67]. Harvesting chondromucosal grafts from the nasal ala can avoid these complications and yield good results [63].

Auricular Cartilage Graft

The auricular cartilage is elastic cartilage with a spherical surface, suitable flexibility, and appropriate physical strength [67]. Compared with other autografts, auricular cartilage is thin, relatively abundant, easy to harvest, and has minor donor site morbidity [68]. Reconstruction of eyelid defects with auricular cartilage grafts shows an aesthetic contour and sufficient support without obvious graft shrinkage or absorption, which prevents eyelid retraction and other complications [69–71]. However, these grafts lack an inner lining for conjunctival reconstruction, and irritation due to direct contact between the eyeball and the raw surface of the graft remains a concern [67]. Preserving the perichondrium or overlaying an oral mucosa graft may be beneficial for solving this problem [5].

Tissue Flaps

Local Tarsoconjunctival Flap

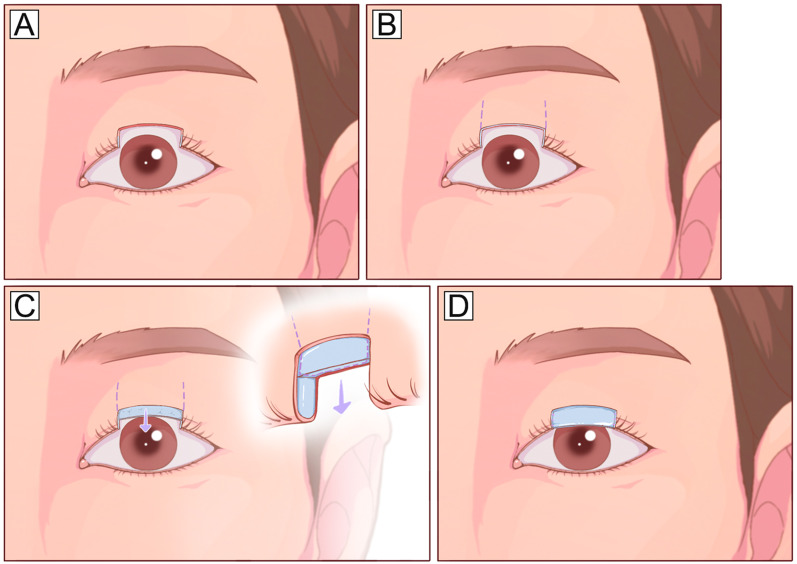

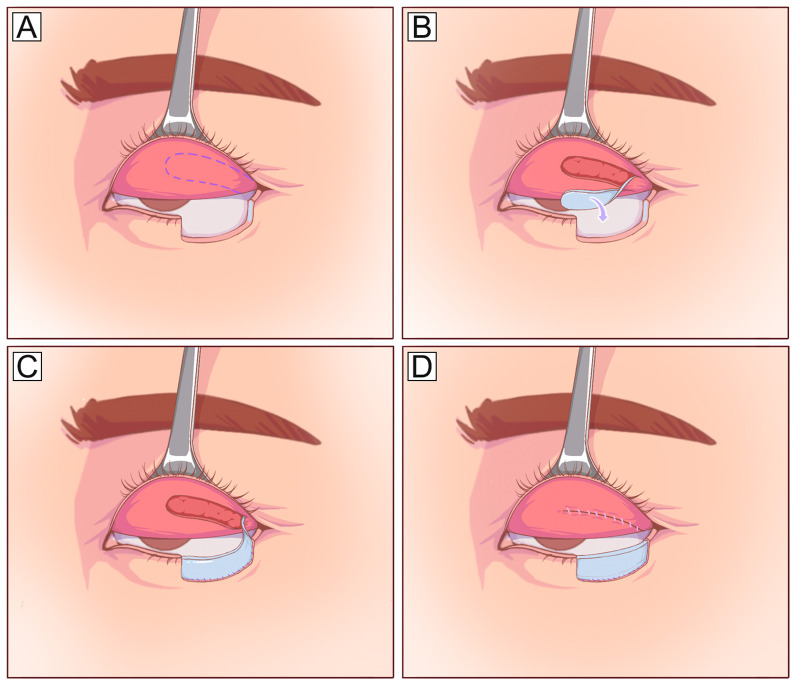

Posterior lamellar defects involving < 60% of the horizontal length can be repaired by using local tarsoconjunctival flaps according to the configuration of the defects. Central defects involving the inferior tarsus and eyelid margin are easily closed using a tarsoconjunctival advancement flap raised from the residual central superior tarsus[72] (Fig. 8). Medial or lateral defects can be repaired using a tarsoconjunctival sliding flap from adjacent eyelid tissue [73] (Fig. 9). Isolated defects evolving the lateral canthus area of the lower eyelid can be repaired using a Hewes tarsoconjunctival flap transposed from the upper eyelid (Fig. 10). These techniques are relatively simple and make full use of the remaining tarsus without tissue transplantation but require a residual tarsus height of at least 3–4 mm to maintain the stability of the reconstructed eyelid.

Fig. 8.

Tarsoconjunctival advancement flap. A A full-thickness upper eyelid defect involving the center upper tarsus and eyelid margin. B Planned incision design on the upper eyelid. C, D The residual center tarsus is cut vertically and mobilized on a conjunctival pedicle and advanced inferiorly to repair the posterior lamella part of the defect

Fig. 9.

Tarsoconjunctival sliding flap. A A full-thickness defect involving the lateral lower eyelid and eyelid margins. B A tarsoconjunctival flap is designed on the medial residual eyelid. C, D The tarsoconjunctival flap is dissected in the posterior lamella plane and slides laterally to fill the posterior lamella defect

Fig. 10.

Tarsoconjunctival sharing flap. A A laterally located full-thickness defect involving half the length of the lower eyelid. B A tarsoconjunctival flap is planned on the posterior lamella of the ipsilateral upper eyelid. C, D The flap is elevated and transposed with a lateral pedicle on the upper eyelid to fill the posterior lamella defect on the lower eyelid

Hughes Tarsoconjunctival Flap

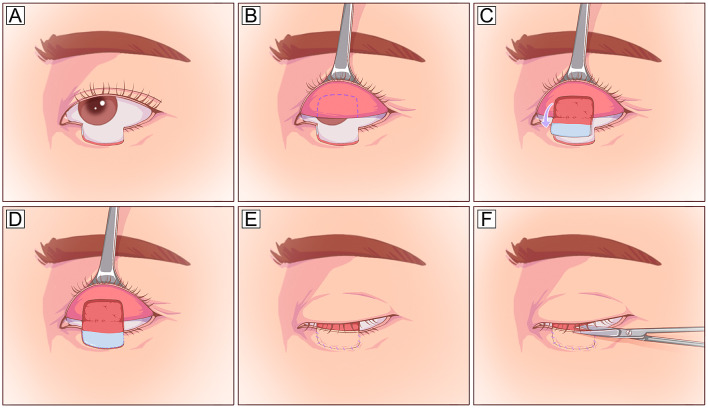

The Hughes tarsoconjunctival flap involves a two-stage eyelid-sharing technique for repairing lower eyelid defects involving 50–100% of the eyelid margin [74–76]. This flap delivers a vascularized tarsoconjunctival flap with a maximum height of 3–4 mm from the upper eyelid margin to the lower eyelid defect [77–79] (Fig. 11). The anterior lamella is typically reconstructed using an FTSG or local cutaneous or myocutaneous flap for full-thickness defects [80]. Following the same principles, a reverse Hughes flap, which transfers a pedicled tarsoconjunctival flap from the lower eyelid to the posterior lamellar defect of the upper eyelid, has been used for large upper eyelid reconstruction [81, 82]. However, these eyelid-sharing procedures lead to meibomian gland loss, lid margin abnormalities, exposure keratopathy [83], and dry eye symptoms [84, 85]. Furthermore, long-term vision occlusion also limits their application, especially in monocular patients [86]. Consequently, the classic Hughes technique is often modified to reduce postoperative complications and improve the blood supply of the flap [68, 74, 87, 88].

Fig. 11.

Hughes tarsoconjunctival flap. A A full-thickness defect involving the center part of the lower eyelid and eyelid margin. B Planned incision design on the conjunctiva surface of the upper eyelid. The flap is designed 4–5 mm from the upper eyelid margin, leaving a strip of the tarsus for structure support. C The flap is dissected in the posterior lamella plane and transposed inferiorly based on a superior conjunctiva pedicle. D The tarsoconjunctival part of the flap is advanced into the defect and sutured with the residual tarsus of the lower eyelid. E The anterior lamella defect is reconstructed with an FTSG. F The flap is separated after 2–4 weeks

Cutler-Beard Flap

The Cutler-Beard flap involves a two-stage eyelid-sharing technique for repairing full-thickness upper eyelid defects involving up to 50% of the eyelid [89]. This flap uses a skin-muscle-conjunctiva flap from the lower eyelid to repair upper eyelid defects (Fig. 12). Similar to the Hughes tarsoconjunctival flap, this flap also impairs vision and requires secondary flap division; unlike the Hughes flap, this flap is a full-thickness flap containing skin, muscle, and conjunctiva. Due to the lack of tarsus within this flap, an additional tarsus substitute, such as free auricular cartilage [31, 90], contralateral tarsus, tarsoconjunctiva [51, 91], or commercial dermal matrix [92], is required to reconstruct the upper eyelid tarsus to prevent postoperative retraction and entropion. Upper eyelid retraction and entropion are common complications of this technique [91].

Fig. 12.

Cutler-Bread flap. A A full-thickness defect involving the center upper eyelid and eyelid margin. The planned incision design is marked 4–5 mm below the lower eyelid margin to preserve the blood supply and stability of the lower eyelid. B A skin-muscle-conjunctiva flap is elevated on the lower eyelid. C The flap is tunneled underneath the undisturbed lower lid tarsus. D The flap is separated into a myocutaneous flap and a conjunctival flap, and the conjunctiva flap is sutured along the defect to repair the conjunctiva defect. E An additional tarsal substitute (e.g., contralateral tarsus, cartilage, perichondrium) is applied to the conjunctival flap to repair the tarsal defect. The myocutaneous flap is covered onto the tarsal substitute and left attached for 2–4 weeks. F The pedicle is divided, and the remaining flap is replaced along the lower lid

Tenzel Semicircular Rotational Flap

The Tenzel semicircular flap has a good color match and minor donor site morbidity and can be used to cover defects involving 1/2–2/3 of the lower or upper eyelid in a single-stage procedure [93, 94]. The flap procedure elevates a laterally or centrally based orbicularis myocutaneous flap initially in the suborbicular plane within the orbital rim and later along the subcutaneous plane beyond the orbital rim, and then the flap is rotated medially for primary closure of the defect (Fig. 13). The Tenzel flap is simple and efficient and can provide an uninterrupted full-thickness eyelid segment with a lash line [93, 95], but the flap is still not free from cicatricial ectropion.

Fig. 13.

Tenzel semicircular rotational flap. A A large full-thickness defect involving the lateral lower eyelid and eyelid margin. The planned flap incision is designed in a semicircular fashion from the lateral edge of the defect out toward the lateral eyebrow line. B The flap is initially undermined in the orbicularis muscle plane within the orbital rim and later along the subcutaneous plane beyond the orbital rim. A canthotomy of the upper limb of the lateral canthus is selectively performed. C The remaining lid along the semicircular myocutaneous flap is rotated medially for primary closure of the defect. The myocutaneous flap is sutured to the lateral edge of the tarsus and secured to the periosteum at the lateral orbital rim to reestablish the lateral canthal height. The lateral canthal height can be reestablished with suture fixation to the superolateral orbital rim periosteum

Mustarde Lower Lid Sharing (Lid Switch) Flap

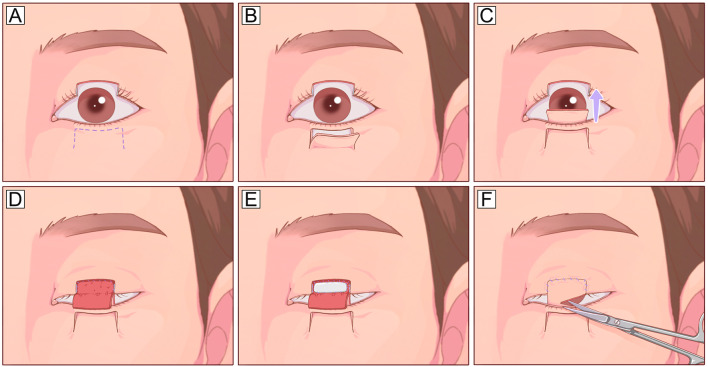

The Mustarde lid switch procedure transfers a full-thickness eyelid flap from the lower eyelid margin to repair an upper eyelid defect [96, 97]. It is well suited for full-thickness, shallow defects involving 30–60% of the upper eyelid, especially for patients who wish to have intact lash restoration. The flap should have a vertical height of 4 mm and a defect length of 1/2–2/3 of the upper eyelid to incorporate the marginal arcade. The flap is typically divided after 2–4 weeks, and the donor site is then repaired via direct closure, lateral canthotomy, or local myocutaneous flaps (Fig. 14). If there is excess tension, lateral canthotomy and cantholysis should be performed to minimize the risk of ectropion. Compared with the classic Cutler-Beard flap, this technique provides greater eyelid stability and allows reconstruction of the lash margin.

Fig. 14.

Mustarde lower eyelid sharing flap. A A full-thickness defect involving the center upper eyelid and eyelid margin. Planned incision design for a lower eyelid sharing flap and a lateral Tenzel rotational flap. B The lower eyelid sharing flap is dissected from the center portion of the lower eyelid and based on a medial pedicle. Simultaneously, the Tenzel flap is elevated, and a triangle-shaped tissue is planned for removal before the medial rotation of the Tenzel flap. C The Tenzel flap is rotated medially to repair the donor eyelid. D The lower eyelid flap is rotated superiorly to repair the upper eyelid defect. E, F The flap is divided after 2–4 weeks

Combinational Techniques

When defects involve two or more layers of eyelid structure, combinational techniques consisting of two or three tissue grafts/flaps are often used to restore the “layer-by-layer” structure of the eyelid. Among them, at least one vascularized tissue/flap is required to provide blood supply for the other free grafts. The basic formula for this technique is one vascularized flap for anterior lamellar reconstruction in combination with one free graft for posterior lamellar replacement. The commonly used flaps are medially or laterally based orbicular myocutaneous flaps [98, 99] and frontal or forehead axial flaps [37, 100], and the commonly used posterior lamellar substitutes are HPM [37, 58], auricular cartilage [100], tarsal grafts [99], and acellular dermal matrixes (ADMs) [82]. In contrast, a vascularized flap for posterior lamellar reconstruction and a free autograft for anterior reconstruction have also been used in full-thickness defect reconstruction [101].

The sandwich technique is a single-stage procedure that fabricates a three-layer structure to restore the closing mechanics. This technique is centered on an orbicularis muscle flap that is then covered with an FTSG and posterior lamellar substitute [55]. When the residual orbicularis muscle is insufficient, a frontalis muscle flap can be used as the center of the “sandwich” instead, and the motor function of the eyelid can also be restored to a certain extent [102]. In addition, tissue fabrication techniques have been applied for fabricating composite grafts for complex eyelid defect reconstruction, such as a chondromucosal-auricular graft [103], chondrocutaneous-myocutaneous composite graft [61], two-layer skin-cartilage unit [104], three-layer skin-cartilage-mucosal unit [105, 106], or skin-tendon-mucosal unit [45].

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Clinical Thinking is Critical for Eyelid Defect Diagnosis and Treatment

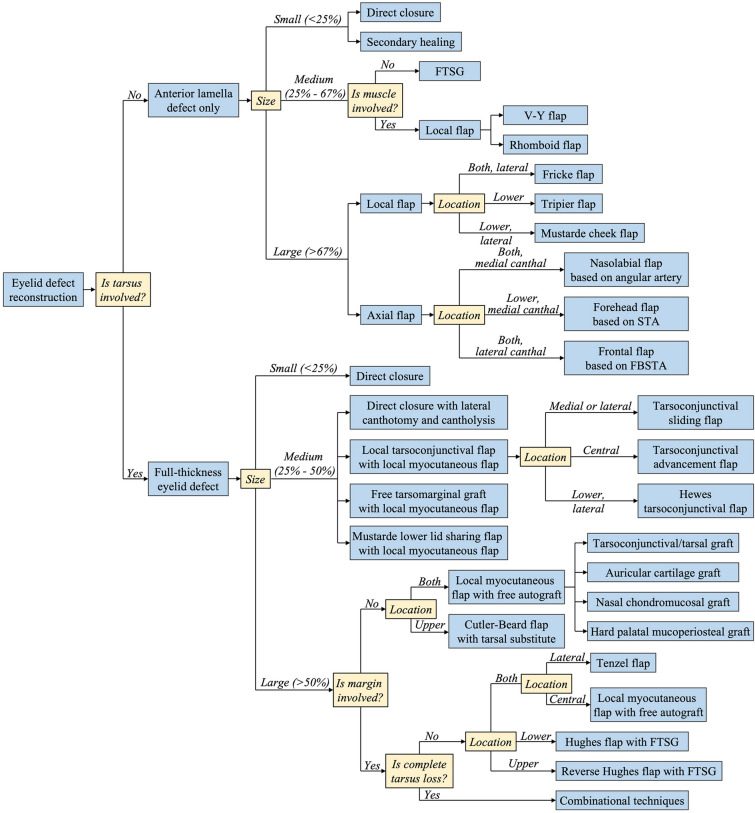

Reconstruction of eyelid defects requires critical clinical thinking and integration of many different surgical techniques to achieve the most functional and aesthetic outcome. Before planning, making an accurate and clear diagnosis for defects based on physical examination is a prerequisite for successful treatment. First, etiological diagnoses are made. Etiological diagnoses are the causes of defects such as trauma, burns, infection, or tumors. This information is beneficial for understanding the mechanism of defects and forming a general impression of the patient’s condition. The second is functional diagnoses. Making functional diagnoses involves searching for the dysfunction on the affected eyelid and evaluating the severity of the dysfunction, such as ectropion, entropion, retraction, ptosis, or movement disorder. These eyelid dysfunctions are the purpose of surgical treatment. Finally, anatomical and pathological diagnoses are made. Making anatomical or pathological diagnoses involves trying to determine the mechanisms of eyelid dysfunction at the anatomical or pathological level. For instance, for defects caused by trauma or burn scars, intensive attention should be given to examining which structures are affected, how large the defect is, and what conditions the surrounding tissues are; for defects caused by infection or tumors, the pathological type and possible infiltration depth of the lesion should be considered. The combination of these three diagnostic approaches enables plastic surgeons to make sound decisions. We recommend a three-step strategy for eyelid defect diagnosis and reconstruction technique selection: the thickness, size, and location. Figure 15 illustrates a decision tree outlining the options discussed in this review.

Fig. 15.

Schematic overview of eyelid defect reconstruction strategies for different conditions. FTSG full-thickness skin graft

Tarsus Tissue Engineering: Transforming from the Replacement Strategy to a Regenerative Strategy

In general, surgical techniques for anterior lamellar reconstruction can achieve adequate function and aesthetic restoration. However, great challenges remain in posterior lamellar reconstruction due to its unique properties and lack of ideal tissue substitutes, especially for the tarsus. Ideally, the conjunctival substitute should be a stable, thin, and elastic construct. In addition, the construct should support efficient epithelial repopulation, stratification, and even goblet cell differentiation to fully mimic the structure and function of native conjunctiva [107, 108]. Autologous tarsoconjunctival grafts or flaps are the gold standard option for posterior lamellar reconstruction but are limited by donor sources. Although various free autografts have been used to replace the damaged tarsus in clinical conditions, none of them can solve the mechanical strength and lubricant problems. Current techniques for eyelid reconstruction, especially posterior lamellar reconstruction, are a replacement strategy with limited functional and aesthetic reconstruction outcomes. Exploring a regenerative strategy for posterior lamellar reconstruction by following the principle of tissue engineering will be one of the breakthroughs in plastic and reconstructive surgery in the future. The growing field of tissue engineering offers promising alternative solutions to this challenge.

Attempts have been made to use biomaterials for clinical posterior lamellar reconstruction. ADM, derived from human (AlloDerm®, BellaDerm®) [82, 109–111], porcine (Endurage®) [112–114], or bovine (Surgimen®) [114, 115] dermis, provides a convenient off-the-shelf alternative for tarsus substitutes due to its good histocompatibility and lower inflammation. They are flexible but sturdy flat sheets of cross-linked collagen matrixes with a basement membrane surface and a dermis surface. However, graft contraction, resorption, and inflammatory responses appear to be the main disadvantages limiting its widespread clinical use [116, 117]. The use of biopolymeric materials, which are relatively biocompatible, rigid, and moldable, may overcome these limitations. Currently, porous high-density PE (Medpor®) has been clinically used for improving lower eyelid retraction [118]. However, high complication rates, including implant exposure, poor stability, skin contour abnormalities, and unexplained pain, make it sparingly used in eyelid surgery. However, the use of biomaterial substitutes has achieved limited clinical outcomes, opening a door for developing biological substates for tarsus, even tarsoconjunctiva. In the future, tissue engineering will advance toward engineering a compound construct consisting of both a layer of dense tissue with certain mechanical strength for tarsus reconstruction and a layer of smooth tissue with lubrication and secretion function for palpebral conjunctiva reconstruction. Such a construct should not only replace the damaged tissue but also take part in tissue regeneration by the transplanted cells and scaffolds.

Conclusions

Comprehensively, when planning an optimal strategy for complex eyelid defect reconstruction, surgeons should have a thorough understanding of eyelid anatomy, follow the reconstructive ladder principles, and consider the defect characteristics. Surgical techniques provide various solutions for anterior lamellar reconstruction and usually result in excellent eyelid functional and aesthetic outcomes. However, posterior lamellar reconstruction remains a challenge and often requires the integration of many different techniques to achieve the most functional and aesthetic outcome.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871571) and the Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty (shslczdzk00901). The journal’s Rapid Service Fees were funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Conceptualization (Ru-Lin Huang, Qingfeng Li); Literature review (Yuxin Yan, Rao Fu, Qiumei Ji, Chuanqi Liu, Jing Yang, Xiya Yin); Writing-original draft preparation (Yuxin Yan, Rao Fu); Writing-review and editing (Ru-Lin Huang, Qingfeng Li, Carlo M. Oranges). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Disclosures

Yuxin Yan, Rao Fu, Qiumei Ji, Chuanqi Liu, Jing Yang, Xiya Yin, Carlo M. Oranges, Qingfeng Li and Ru-Lin Huang declare that they have no conflicts of interest and no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Yuxin Yan and Rao Fu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Qingfeng Li, Email: dr.liqingfeng@shsmu.edu.cn.

Ru-Lin Huang, Email: huangrulin@sjtu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sun MT, O'Connor AJ, Wood J, Casson R, Selva D. Tissue engineering in ophthalmology: implications for eyelid reconstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3):157–162. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coban I, Sirinturk S, Unat F, Pinar Y, Govsa F. Anatomical description of the upper tarsal plate for reconstruction. Surg Radiol Anat. 2018;40(10):1105–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-2064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen JM, Shanbhag SS, Shih GC, et al. Multidisciplinary treatment to restore vision in ocular burns. J Burn Care Res. 2020;41(4):859–865. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irz201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Ou Z, Zhou J, Zhai J, Gu J, Chen J. Treatment of oculoplastic and ocular surface disease in eyes implanted with a type I Boston Keratoprosthesis in Southern China: a retrospective study. Adv Ther. 2020;37(7):3206–3222. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01381-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto N, Ogi H, Yanagibayashi S, et al. Eyelid reconstruction using oral mucosa and ear cartilage strips as sandwich grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5(4):e1301. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holds JB. Lower eyelid reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2016;24(2):183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zlatarova ZI, Nenkova BN, Softova EB. Eyelid reconstruction with full thickness skin grafts after carcinoma excision. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2016;58(1):42–47. doi: 10.1515/folmed-2016-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mol I, Paridaens D. Efficacy of lateral eyelid-block excision with canthoplasty and full-thickness skin grafting in lower eyelid cicatricial ectropion. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97(4):e657–e661. doi: 10.1111/aos.13958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bortz JG, Al-Shweiki S. Free tarsal graft and free skin graft for lower eyelid reconstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(6):605–609. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berggren J, Tenland K, Ansson CD, et al. Revascularization of free skin grafts overlying modified hughes tarsoconjunctival flaps monitored using laser-based techniques. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35(4):378–382. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jongh FW, Pouwels S, Weenen C, van den Bosch WA, Paridaens D. Medial canthal reconstruction of skin defects with full-thickness skin grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47(8):1135–1137. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rathore DS, Chickadasarahilli S, Crossman R, Mehta P, Ahluwalia HS. Full thickness skin grafts in periocular reconstructions: long-term outcomes. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(6):517–520. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seth D, Scott JF, Bordeaux J. Repair of a large full-thickness defect of the lower eyelid. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47(1):117–119. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibreel W, Harvey JA, Garrity J, Bite U. Lower eyelid reconstruction using a nasolabial, perforator-based V-Y advancement flap: expanding the utility of facial perforator flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;82(1):46–52. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart CM, Norris JH. Reconstruction of extensive medial canthal defects using a single V-Y, island pedicle flap. Orbit. 2018;37(5):331–334. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2017.1423344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yesiloglu N, Sirinoglu H, Sarici M, Temiz G, Guvercin E. A simple method for the treatment of cicatricial ectropion and eyelid contraction in patients with periocular burn: vertical V-Y advancement of the eyelid. Burns. 2014;40(8):1820–1821. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lize F, Leyder P, Quilichini J. Horizontal V-Y advancement flap for lower eyelid reconstruction in young patients. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2015;38(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim GW, Bae YC, Kim JH, Nam SB, Kim HS. Usefulness of the orbicularis oculi myocutaneous flap in periorbital reconstruction. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2018;19(4):254–259. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.02019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesiktas E, Eser C, Gencel E, Aslaner EE. A useful flap combination in wide and complex defect reconstruction of the medial canthal region: Glabellar rotation and nasolabial V-Y advancement flaps. Plast Surg (Oakv) 2015;23(2):113–115. doi: 10.4172/plastic-surgery.1000910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajabi MT, Hosseini SS, Rajabi MB, Tabatabaie SZ. A novel technique for full thickness medial canthal reconstruction; playing with broken lines. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2016;28(4):212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.joco.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller CJ. Design principles for transposition flaps: the rhombic (single-lobed), bilobed, and trilobed flaps. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(Suppl 9):S43–52. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho W, Jones CD. Geometry and design of a rhomboid flap. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2021;55(4):249–254. doi: 10.1080/2000656X.2021.1873792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eroglu L, Simsek T, Gumus M, Aydogdu IO, Kurt A, Yildirim K. Simultaneous cheek and lower eyelid reconstruction with combinations of local flaps. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(5):1796–1800. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182a2113f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selcuk CT, Erbatur S, Durgun M, Calavul A. Repairs of large defects of the lower lid and the infraorbital region with suspended cheek flaps with a dermofat flap. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(6):e539–e541. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim KP, Sim HS, Choi JH, et al. The versatility of cheek rotation flaps. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2016;17(4):190–197. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2016.17.4.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibanez-Flores N, Bruzual-Lezama C, Castellar-Cerpa JJ, Fernandez-Montalvo L. Lower eyelid reconstruction with pericranium graft and Mustarde flap. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed) 2019;94(10):514–517. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machado WL, Gurfinkel PC, Gualberto GV, Sampaio FM, Melo ML, Treu CM. Modified Tripier flap in reconstruction of the lower eyelid. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(1):108–110. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park SH, Elfeki B, Eun S. Laterally based orbicularis oculi myocutaneous flap: revisiting for the secondary ectropion correction. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(2):e157–e160. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verna G, Boriani F, Taveggia A, Fraccalvieri M. The Tripier reverse flap for reconstruction of the upper eyelid. Ann Ital Chir. 2009;80(4):311–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson AA, Cohen JL. Modified Tripier flap for lateral eyelid reconstructions. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(2):199–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukit M, Anbar F, Dadireddy K, Konofaos P. Eyelid reconstruction: an algorithm based on defect location. J Craniofac Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000008433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JH, Woo SS, Shin SH, et al. Upper eyelid reconstruction using a combination of a nasal septal chondromucosal graft and a Fricke flap: a case report. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2021;22(4):204–208. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2021.00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu L, Patel BC. Lagophthalmos. StatPearls. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing Copyright©; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sengupta S, Baruah B, Pal S, Tuli IP. Total reconstruction of lower eyelid in a post-traumatic patient using modified Fricke's cheek flap. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2013;5(2):95–98. doi: 10.4103/2006-8808.128749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauso R, Nicoletti GF, Sesenna E, et al. Superficial temporal artery perforator flap: indications, surgical outcomes, and donor site morbidity. Dent J (Basel). 2020 doi: 10.3390/dj8040117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding J, Liu C, Cui J, Liu H, Su Y, Ma X. Efficacy of pre-expanded forehead flap based on the superficial temporal artery in correction of cicatricial ectropion of the lower eyelid. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;59(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu J, Qing Y, Cen Y, Chen J. Frontal axial pattern flap combined with hard palate mucosa transplant in the reconstruction of midfacial defects after the excision of huge basal cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1421-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng Y, Zhao J, Wang X, et al. The application of axial superficial temporal artery island flap for repairing the defect secondary to the removal of the lower eyelid basal cell carcinoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52(1):72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eyraud Q, Grivet D, Gleizal A, Alix T, Prade V. Superficial temporal artery perforator flap for reconstruction of periorbital and eyelid defects, a variant of the classic flaps dissected in perforator flap. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;122(5):482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elbanoby TM, Elbatawy A, Aly GM, et al. Bifurcated superficial temporal artery island flap for the reconstruction of a periorbital burn: an innovation. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(6):e748. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozkaya Mutlu O, Egemen O, Dilber A, Uscetin I. Aesthetic unit-based reconstruction of periorbital defects. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(2):429–432. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agorgianitis L, Panagouli E, Tsakotos G, Tsoucalas G, Filippou D. The supratrochlear artery revisited: an anatomic review in favor of modern cosmetic applications in the area. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e7141. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tripathy S, Garg A, John JR, Sharma RK. Use of modified islanded paramedian forehead flap for complex periocular facial reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(2):e117–e119. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lian C, Zhang JZ, Li XL, Liu XJ. Reconstruction of a large oncologic defect involving lower eyelid and infraorbital cheek using MSTAFI flap. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021 doi: 10.1177/01455613211000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang W, Meng H, Yu S, Liu T, Shao Y. Reconstruction of giant full-thickness lower eyelid defects using a combination of palmaris longus tendon with superiorly based nasolabial skin flap and palatal mucosal graft. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2021;55(3):147–152. doi: 10.1080/2000656X.2020.1856123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim YS, Choi DY, Gil YC, Hu KS, Tansatit T, Kim HJ. The anatomical origin and course of the angular artery regarding its clinical implications. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(10):1070–1076. doi: 10.1097/01.DSS.0000452661.61916.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yousefiazar A, Hassanzadazar M. A new technique for reconstruction of medium-sized eyelid defects (a modification of Tessier Nasojugal Flap) Facial Plast Surg. 2018;34(6):657–662. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Talwar B, Khader M, Monis PL, Aftab A. Surgical treatment of recurrent lower eyelid sebaceous gland carcinoma and reconstruction with pedicled nasolabial and non-vascularised buccal mucosal flaps. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2019;18(4):536–538. doi: 10.1007/s12663-018-1171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tatar S, Yontar Y, Ozmen S. Superiorly based nasolabial island flap for reconstruction of the lateral lower eyelid. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47(6):1673–1680. doi: 10.3906/sag-1701-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tenland K, Berggren J, Engelsberg K, et al. Successful free bilamellar eyelid grafts for the repair of upper and lower eyelid defects in patients and laser speckle contrast imaging of revascularization. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37(2):168–172. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bengoa-Gonzalez A, Laslau BM, Martin-Clavijo A, Mencia-Gutierrez E, Lago-Llinas MD. Reconstruction of upper eyelid defects secondary to malignant tumors with a newly modified cutler-beard technique with tarsoconjunctival graft. J Ophthalmol. 2019;2019:6838415. doi: 10.1155/2019/6838415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pham CM, Heinze KD, Mendes-Rufino-Uehara M, Setabutr P. Single-stage repair of large full thickness lower eyelid defects using free tarsoconjunctival graft and transposition flap: experience and outcomes. Orbit. 2022;41(2):178–183. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1852579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajak SN, Malhotra R, Selva D. The 'over-the-top' modified Cutler-Beard procedure for complete upper eyelid defect reconstruction. Orbit. 2019;38(2):133–136. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2018.1444061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yazici B, Ozturker C, Cetin EA. Reconstruction of large upper eyelid defects with bilobed flap and tarsoconjunctival graft. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(4):372–374. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toft PB. Reconstruction of large upper eyelid defects with a free tarsal plate graft and a myocutaneous pedicle flap plus a free skin graft. Orbit. 2016;35(1):1–5. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2015.1078372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vimont T, Arnaud D, Rouffet A, Giot JP, Florczak AS, Rousseau P. Hubner's tarsomarginal grafts in eyelid reconstruction: 94 cases. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;119(4):268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yue H, Tian L, Bi Y, Qian J. Hard palate mucoperiosteal transplantation for defects of the upper eyelid: a pilot study and evaluation. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(5):469–474. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hendriks S, Bruant-Rodier C, Lupon E, Zink S, Bodin F, Dissaux C. The palatal mucosal graft: the adequate posterior lamellar reconstruction in extensive full-thickness eyelid reconstruction. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2020;65(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takasu H, Yagi S, Taguchi S, Furukawa S, Ono N, Shimomura Y. Lower eyelid reconstruction using a myotarsocutaneous flap while considering the superior and inferior Palpebral Sulci. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(3):e4147. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kececi Y, Bali ZU, Ahmedov A, Yoleri L. Angular artery island flap for eyelid defect reconstruction. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2020;54(1):1–5. doi: 10.1080/2000656X.2019.1647851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barin EZ, Cinal H. Total and near-total lower eyelid reconstruction with prefabricated orbicularis oculi musculocutaneous island flap. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3):e13372. doi: 10.1111/dth.13372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eser C, Kesiktas E, Gencel E, Tabakan I, Yavuz M. Total or near-total lower eyelid defect reconstruction using malar myocutaneous bridge and nasojugal flaps and septal chondromucosal graft. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32(3):225–229. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lemaitre S, Levy-Gabriel C, Desjardins L, et al. Outcomes after surgical resection of lower eyelid tumors and reconstruction using a nasal chondromucosal graft and an upper eyelid myocutaneous flap. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2018;41(5):412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gumus N. Three-dimensional tarsal plate reconstruction using lower lateral cartilage of the nose. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;88(4):406–409. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000003097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rajabi MT, Bazvand F, Hosseini SS, et al. Total lower lid reconstruction: clinical outcomes of utilizing three-layer flap and graft in one session. Int J Ophthalmol. 2014;7(3):507–511. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2014.03.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Santos G, Goulao J. One-stage reconstruction of full-thickness lower eyelid using a Tripier flap lining by a septal mucochondral graft. J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25(5):446–447. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.768329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suga H, Ozaki M, Narita K, et al. Comparison of nasal septum and ear cartilage as a graft for lower eyelid reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(2):305–307. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen B, Woo DM, Liu J, et al. Conjunctival flap with auricular cartilage grafting: a modified Hughes procedure for large full thickness upper and lower eyelid defect reconstruction. Int J Ophthalmol. 2021;14(8):1168–1173. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2021.08.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamashita K, Yotsuyanagi T, Sugai A, et al. Full-thickness total upper eyelid reconstruction with a lid switch flap and a reverse superficial temporal artery flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73(7):1312–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barrancos C, Garcia-Cruz I, Ventas-Ayala B, Sales-Sanz M. The addition of a conjunctival flap to a posterior lamella auricular cartilage graft: a technique to avoid corneal complications. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31(4):2165–2170. doi: 10.1177/1120672121998914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Malviya V, Goyal S, Bansal V. Reconstruction of lower eyelid with nasolabial flap for anterior lamella and turnover flap for posterior lamella. Surg J (N Y) 2022;8(1):e56–e59. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1742177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Skippen B, Hamilton A, Evans S, Benger R. One-stage alternatives to the Hughes procedure for reconstruction of large lower eyelid defects: surgical techniques and outcomes. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32(2):145–149. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Custer PL, Neimkin M. Lower eyelid reconstruction with combined sliding tarsal and rhomboid skin flaps. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32(3):230–232. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hishmi AM, Koch KR, Matthaei M, Bolke E, Cursiefen C, Heindl LM. Modified Hughes procedure for reconstruction of large full-thickness lower eyelid defects following tumor resection. Eur J Med Res. 2016;21(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s40001-016-0221-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McKelvie J, Ferguson R, Ng SGJ. Eyelid reconstruction using the "Hughes" tarsoconjunctival advancement flap: long-term outcomes in 122 consecutive cases over a 13-year period. Orbit. 2017;36(4):228–233. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2017.1310256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mori S, Di Monta G, Marone U, Botti G. Lower eyelid orbicularis oculi myocutaneous flap: a feasible technique for full thickness upper eyelid reconstruction. World J Plast Surg. 2021;10(2):98–102. doi: 10.29252/wjps.10.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aggarwal S, Shah CT, Kirzhner M. Modified second stage Hughes tarsoconjunctival reconstruction for lower eyelid defects. Orbit. 2018;37(5):335–340. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2017.1423351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ekin MA, Ugurlu SK. Impact of the type of anterior lamellar reconstruction on the success of modified Hughes procedure. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2020;83(1):11–18. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20200011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen Y, Al-Sadah Z, Kikkawa DO, Lee BW. A modified Hughes flap for correction of refractory Cicatricial lower lid retraction with concomitant ectropion. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(5):503–507. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yano T, Karakawa R, Shibata T, et al. Ideal esthetic and functional full-thickness lower eyelid "like with like" reconstruction using a combined Hughes flap and swing skin flap technique. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74(11):3015–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2021.03.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sa HS, Woo KI, Kim YD. Reverse modified Hughes procedure for uppereyelid reconstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(3):155–160. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181b8e5fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eah KS, Sa HS. Reconstruction of large upper eyelid defects using the reverse Hughes flap combined with a sandwich graft of an acellular dermal matrix. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37(3S):S27–S30. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Juniat V, Ryan T, O'Rourke M, et al. Hughes flap in the management of lower lid retraction. Orbit. 2021 doi: 10.1080/01676830.2021.2006721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klein-Theyer A, Horwath-Winter J, Dieter FR, Haller-Schober EM, Riedl R, Boldin I. Evaluation of ocular surface and tear film function following modified Hughes tarsoconjunctival flap procedure. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92(3):286–290. doi: 10.1111/aos.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang MT, Kersey TL, Sloan BH, Craig JP. Evaporative dry eye following modified Hughes flap reconstruction. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;46(6):700–702. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marcet MM, Lau IHW, Chow SSW. Avoiding the Hughes flap in lower eyelid reconstruction. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28(5):493–498. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kaufman AR, Pham C, MacIntosh PW. Reconstruction of full width, full thickness cicatricial eyelid defect after eyelid blastomycosis using a modified tarsoconjunctival flap advancement. Orbit. 2021 doi: 10.1080/01676830.2021.1884265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mehta HK. Myotarsal flap—a versatile entity for lower eyelid reconstructions. Orbit. 2018;37(3):223–229. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2018.1463547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rahmi D, Mehmet B, Ceyda B, Sibel O. Management of the large upper eyelid defects with cutler-beard flap. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014:424567. doi: 10.1155/2014/424567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mandal SK, Fleming JC, Reddy SG, Fowler BT. Total upper eyelid reconstruction with modified Cutler-Beard procedure using autogenous auricular cartilage. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(8):NC01–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/20303.8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yoon MK, McCulley TJ. Secondary tarsoconjunctival graft: a modification to the Cutler-Beard procedure. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29(3):227–230. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182831c84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shin HY, Chu M, Kim JH, Paik JS, Yang SW. Surgical feasibility of Curtler-Beard reconstruction for large upper eyelid defect. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(7):2181–2183. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cha JA, Lee KA. Reconstruction of periorbital defects using a modified Tenzel flap. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2020;21(1):35–40. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2019.00577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mandal SK, Maitra A, Ganguly P, Agarwal SS. Surgical outcomes of Tenzel rotational flap in upper and lower lid reconstruction without repair of posterior lamella: a modified approach. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2021;65(4):354–361. doi: 10.22336/rjo.2021.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yordanov YP, Shef A. Lower eyelid reconstruction after ablation of skin malignancies: how far can we get in a single-stage procedure? J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(5):e477–e479. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang YC, Dai HY, Xing X, Lv C, Zhu J, Xue CY. Pedicled lower lid-sharing flap for full-thickness reconstruction of the upper eyelid. Eye (Lond) 2014;28(11):1292–1296. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kuzmanovic Elabjer B, Busic M, Miletic D, Plese A, Bjelos M. The new face of the switch flap in the reconstruction of a large upper eyelid defect. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2022;2022:4159263. doi: 10.1155/2022/4159263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yoshitatsu S, Shiraishi M. A modified method for upper eyelid reconstruction with innervated orbicularis oculi myocutaneous flaps and lower lip mucosal grafts. JPRAS Open. 2021;28:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jpra.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee WW, Ohana O, Portaliou DM, Erickson BP, Sayed MS, Tse DT. Reconstruction of total upper eyelid defects using a myocutaneous advancement flap and a composite contralateral upper eyelid tarsus and hard palate grafts. JPRAS Open. 2021;28:52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpra.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yang M, Zhao Y. Reconstruction of full-thickness lower eyelid defect using superficial temporal artery island flap combined with auricular cartilage graft. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(2):576–579. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Moesen I, Paridaens D. A technique for the reconstruction of lower eyelid marginal defects. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(12):1695–1697. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.123075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stewart CM, Tan LT, Johnson D, Norris JH. Key issues when reconstructing extensive upper eyelid defects with description of a dynamic, frontalis turnover flap. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32(4):249–251. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nicoletti G, Jaber O, Tresoldi MM, Pellegatta T, Faga A. Prefabricated composite graft for eyelid reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg. 2015;31(5):534–538. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1564584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pushker N, Modaboyina S, Meel R, Agrawal S. Auricular skin-cartilage sandwich graft technique for full-thickness eyelid reconstruction. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(4):1404–1407. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1797_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fodor L, Bran S, Armencea G, Onisor F. Novel, "all-in-one" sandwich technique for reconstruction of full-thickness defects of the lower eyelid: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(4):300060520918697. doi: 10.1177/0300060520918697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jin MJ, Gao Y. Using buccal mucosa and auricular cartilage with a local flap for full-thickness defect of lower eyelid. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32(7):e660–e661. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lu Q, Al-Sheikh O, Elisseeff JH, Grant MP. Biomaterials and tissue engineering strategies for conjunctival reconstruction and dry eye treatment. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22(4):428–434. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.167818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Eidet JR, Dartt DA, Utheim TP. Concise review: comparison of culture membranes used for tissue engineered conjunctival epithelial equivalents. J Funct Biomater. 2015;6(4):1064–1084. doi: 10.3390/jfb6041064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kim KY, Woo YJ, Jang SY, Lee EJ, Yoon JS. Correction of lower eyelid retraction using acellular human dermis during orbital decompression. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3):168–172. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bee YS, Alonzo B, Ng JD. Review of AlloDerm acellular human dermis regenerative tissue matrix in multiple types of oculofacial plastic and reconstructive surgery. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(5):348–351. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Scruggs JT, McGwin G, Jr, Morgenstern KE. Use of noncadaveric human acellular dermal tissue (BellaDerm) in lower eyelid retraction repair. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(5):379–384. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Grumbine FL, Idowu O, Kersten RC, Deparis SW, Vagefi MR. Correction of lower eyelid retraction with En glove placement of porcine dermal collagen matrix implant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(3):743–746. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.McGrath LA, Hardy TG, McNab AA. Efficacy of porcine acellular dermal matrix in the management of lower eyelid retraction: case series and review of the literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(9):1999–2006. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Barmettler A, Heo M. A prospective, randomized comparison of lower eyelid retraction repair with autologous auricular cartilage, bovine acellular dermal matrix (Surgimend), and porcine acellular Dermal Matrix (Enduragen) spacer grafts. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34(3):266–273. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sun J, Liu X, Zhang Y, et al. Bovine acellular dermal matrix for levator lengthening in thyroid-related upper-eyelid retraction. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:2728–2734. doi: 10.12659/MSM.909306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Teo L, Woo YJ, Kim DK, Kim CY, Yoon JS. Surgical outcomes of porcine acellular dermis graft in anophthalmic socket: comparison with oral mucosa graft. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2017;31(1):9–15. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.31.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mancera N, Schneider A, Margo CE, Bajric J. Inflammatory reaction to decellularized porcine-derived xenograft for lower eyelid retraction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35(4):e95–e97. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Khalil AA, Yassine S, Torbey JS, Mehanna CJ, Alameddine RM. Intraocular migration of porous polyethylene malar implant used for Treacher collins eyelid reconstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37(2):e73–e75. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.