Abstract

Behavioral problems in children are a global issue, and it has attracted scholars in both developed and developing countries. This study aims to examine religious beliefs and parenting styles in predicting children’s behavioral problems, as well as investigate the mediating role of digital literacy to explain this relationship. This research adopted a quantitative approach based on the questionnaire provided to parents with different religious backgrounds who participated in the online survey. From a methodological perspective, we followed SEM-PLS to analyze and raise the comprehension of the phenomenon studied. The findings indicate that religious beliefs can affect authoritarian parenting styles and negatively influence digital literacy. However, religious beliefs failed in explaining children’s negative behavior. This research also notes the role of parenting style in driving children’s digital literacy and children’s behavior. Meanwhile, digital literacy does not influence children’s negative behavior. This study provides a sharpening of previous research on the theme of religious beliefs and parenting styles, as well as contributes to science related to the digital literacy and behavior of children.

Keywords: Digital literacy, Children behavior, Parenting style, Religious beliefs

Digital literacy; Children behavior; Parenting style; Religious beliefs

1. Introduction

The children’s behavior is a global issue that has been acknowledged among scholars, and it is often linked with parenting styles (Riany et al., 2017; Yananda et al., 2020). There are several parenting styles, including authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive, which has different characteristics and visible impact on children’s behavior (Özgür, 2016; Dempster et al., 2013). From an early age, children learn behavior from their social environment through observing models in their circumstances (Rathus, 2014). A preliminary study by Strayer and Roberts (2004) remarked that children’s interaction with parents and their environment impacts children. In doing so, children are also more dominant in imitating what their parents do instead of what their parents say, and this involvement affects children’s behavior (Patterson, 2005).

Some scholars believe that an inappropriate parenting style often leads to children’s negative behavior (Pickering and Sanders, 2016; Moon and Bai, 2020). The aforementioned studies remarked that the most significant factor in children’s behavior is applying an authoritarian parenting style. Authoritarianism can lead to aggressive behavior, depression, delinquency, and other problems in the later stages of children’s lives (Haslam et al., 2020; Konok et al., 2020). It is believed that authoritarian parenting style has the characteristics of asserting that parents are not only demanding without warmth, but also parents are not responsive to children’s requests. Punishment, coercion, and violence are primarily techniques used by parents to demonstrate this authoritarian style.

Authoritarian parenting is often acquainted with religious beliefs. Some preliminary studies by Volling et al. (2009); Nnadozie et al. (2018) revealed that religious beliefs have a noticeable impact on the adoption of parenting styles. The underlying reason is that religiosity is perceived as the culture which forms values and behaviors of parents to guide their children. In particular, during the coronavirus pandemic, it forced family members to adopt technology and the Internet, including education, economic, and social involvement. The situation brings a challenge for parents on how to avoid online risks that potentially leads to negative children’s behavior. In this matter, parenting styles have many perspectives regarding the ability to adopt gadgets for their children. Many parents provide education and stimulation to children by taking advantage of current technological developments (Lemish et al., 2020).

The use of gadgets in Indonesia is increasingly widespread, and it is ranked the fifth largest use of gadgets in the world. This is evidenced in 2019 data which shows that there are around 196.7 million digital media users. The number of people who use digital media is 73.7% of children and adolescents is a percentage of users (Kominfo, 2020). However, the use of gadgets has risen dramatically as a consequence of distancing policy during the Covid-19 pandemic. This increase in gadgets adoption definitely has both negative and positive impacts on human life. The positive impact can be reached in managing educational achievement, looking for information, and enhancing the opportunities to gain knowledge. At the same time, the negative impact of using the gadget for children is generally caused by the excessive use of devices.

Therefore, it is necessary to balance technological developments with digital literacy, focusing on understanding and using the information found on the internet in various formats (Gilster, 1997). It implies that children are fluent in using technology (digital) and make children master information literacy skills from digital media. Also, children need to understand the conceptual framework of technology, norms, and practices for using digital technology (Meyers et al., 2013). Digital literacy covers skill or competence to find information and the ability to involve digital matters in their lives (Gilster, 1997). In detail, digital literacy has three levels first, digital competency, digital usage, and transformation (Martin and Grudziecki, 2006); then, in the context of this research, digital literacy refers to the first and second levels.

Since the matter of parenting styles for children, it has raised attention among scholars in Indonesia and other countries. For instance, Myers (1996); Petro et al. (2018) showed that the level of parental diversity impacts children’s positive behavior. Additionally, Riany et al. (2017) remarked that religious beliefs can also impact authoritarian parenting patterns. While some earlier studies revealed that parenting style had been linked with the use of gadgets and the internet (Valcke et al., 2010; Terras and Ramsay, 2016). Some scholars noted that the spiritual level of parents shows a positive influence on children’s development (Myers, 1996; Petts, 2011; Petro et al., 2018). However, there is also evidence that parental diversity indirectly impacts children’s behavior problems with the mediator variable parenting patterns (Bartkowski et al., 2019). This study aims to fill this knowledge gap on parenting styles which can determine children’s behavioral problems from the perspectives of religious beliefs, as well as to understand the mediating role of digital literacy. This study provides an insight into the theme of religious belief and its influence on authoritarian parenting styles. This research contributes to science related to digital literacy and behavioral problems in children. Furthermore, this study can be used by stakeholders in providing decisions and policies related to digital literacy for parents and children.

The paper is provided as follows. Section 1 discusses the main issue and the background of the study. In section 2, this paper provides state of the art on religious beliefs, parenting styles, digital literacy, and children’s behavior. Section 3 describes the methodology and data, followed by the result analysis and discussion in Section 4 and Section 5. The last section concerns the conclusions, limitations, and directions for further research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Religious belief and parenting style

Religious beliefs can calm anxiety in the face of phenomena and protect humans and civilization’s destructive instincts (Freud, 1927). Religious belief is a dimension of a belief that can determine a person to accept something dogmatic and belief in the existence of his religious teachings (Glock and Stark, 1966). More specifically, religious belief is a person’s belief regarding the image of God (Newton and Mcintosh, 2010). The importance of religious beliefs can influence parents’ disciplinary decisions on child-rearing or parenting styles. Some preliminary studies documented that religious belief have a crucial role in determining the adoption of parenting styles (Petro et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2019). Religious beliefs can shape values and behavior by emphasizing family relationships and commitment to actively participating in their children’s lives (Volling et al., 2009). Religious beliefs can affect family interactions by prohibiting or allowing substances from the perspectives of religion. This is important to be adopted in the parenting style because it can gain value, provide support, and drive purpose and meaning (Krok, 2018).

Previous research has shown that parenting styles that are emotionally responsive, often involved in children’s activities, and democratic show a positive relationship to firm parental religious beliefs (Williams et al., 2019). Meanwhile, another study has stated that religious beliefs can sometimes lead to regressive behavior and damage family relationships. Certain religious expressions can have negative consequences on the family, including applying an authoritarian parenting style (Riany et al., 2017). Religious beliefs can harm children’s growth and development if they have become a source of conflict in a family, while religious beliefs can lead to the application of an authoritarian parenting style, it can be seen that children must obey their parents’ orders and their views are lower than their parents. It is believed that if children do not obey their parents' orders, they will receive “spiritual punishment” (Riany et al., 2017). Therefore, the hypothesis is provided as follows.

H1

Religious belief positively affects parenting style

2.2. Religious belief and digital literacy

Previous research remarked that the relationship between religious belief and digital literacy is negative because religion is an institution that holds traditional moral values as beliefs. On the other hand, digital literacy is an invention of modern society in which many introduce secular or non-traditional cultures that are contrary to the core of religious beliefs (Stout and Buddenbaum, 1996). Indeed, Paine (2015) stated that activity in religious belief has a negative relationship with digital competence, which includes the use of devices to retrieve, assess, store, produce, present and exchange information, communicate and participate in collaborative networks via the Internet (Gordon et al., 2009). As described by Meyers et al. (2013), the scope of digital literacy is mastery in the use of (digital) technology and mastery of information literacy skills from digital media to conceptual frameworks related to understanding, norms, and usage practices. It indicates that high levels of human education and liberal theology tend to promote tolerance (Krok, 2018). While other studies also revealed that stronger religious beliefs can lead to negative attitudes toward change, especially in the field of science (Morgan et al., 2018). Thus, the hypothesis is presented as follows.

H2

Religious belief positively affects digital literacy

2.3. Religious belief and behavioral problem

Behavioral problems in children can take the form of reactive emotions, anxiety, depression, somatic complaints, introverts, problems with attention, aggressive behavior, internalization, and externalization (Yananda et al., 2020). The concept of behavioral problems in this study is indeed more emphasized on mental health problems and does not refer to specific forms of action or expressions that show symptoms of problematic behavior. This is because the research findings that show the influence of gadgets on children’s behavior problems focus on mental health (Munawar and Amri, 2018; Saniyyah et al., 2021) then the general symptoms of mental health are taken which allow respondents or parents to identify indicators of different children’s behavior but reflect different mental health problems, which in turn impact on children’s negative behavior. The main factor that causes children’s behavior is children’s interaction with the surrounding environment, including parents (Dempster et al., 2013).

Preliminary studies stated that the religious beliefs of parents can influence children’s behavior, and it is linked with the parenting style applied by parents (Johnson et al., 2001; Chamratrithirong et al., 2013). Additionally, Li et al. (2018) noted that religious belief is a determining factor in attitudes and behavior because religion is a social institution and social control in life. Spiritual practices of parents can affect delinquency in the case of children and teenagers (Li et al., 2018). In general, research on the spiritual level of parents shows a positive influence on children’s development (Myers, 1996; Petts, 2011; Petro et al., 2018). However, there is also evidence that parental diversity indirectly impacts children’s behavior problems with the mediator variable parenting patterns (Bartkowski et al., 2019). This study attempts to examine the direct influence of the relationship between parents' religious beliefs and children’s behavior problems. In detail, this study put forward the following hypothesis.

H3

Religious belief positively affects children behavior problem

2.4. Parenting style and digital literacy

The use of gadgets is elementary and continues to spread consuming by children, primarily during the coronavirus pandemic. In some cases, children tend to use applications such as YouTube or TikTok content that is less educative and not infrequently, which in turn affects their negative behavior. The content raises scenes of inappropriate advertisements, violence, and other things that are not appropriate to watch according to their age. In doing so, digital literacy for children is essential in avoiding online risks, which can be provided by parenting style (Papadakis et al., 2019). Therefore, characteristics of parenting style can be used as a level of warmth and command to parents. Warmth to parents can be realized through activities such as letting children watch videos, play games, and help children use gadgets. Authoritarian parenting style in children can result in excessive use of devices (Valcke et al., 2010). Previous research stated that authoritative parenting provides opportunities for children to use devices but with conditions (for example, after the child has finished doing their work (Özgür, 2016). Authoritarian parenting tends not to allow children to use devices, only showing photos or videos to children without children being given access independently (Konok et al., 2020). Thus, the hypothesis is presented as follows.

H4

Parenting style positively affects digital literacy

2.5. Parenting style and behavioral problem

Parents have an essential role in providing a great home circumstance as stimulus for enhancement of students' behavior (Papadakis et al., 2021). Authoritative parenting has the characteristics of warmth, firm but fair control, and the use of explanation and reasoning in every activity (Campbell, 1995), and has a high responsibility (Baumrind, 1991). The connection with digital literacy is that parents can communicate warmly as long as children use devices. Parents are closer to children to direct the adoption of devices so that authoritative parenting is able to minimize negative impacts on children (Özgür, 2016; Fikkers et al., 2017). Furthermore, authoritarian parenting has the characteristics of asserting without warmth, and parents are not only demanding but parents are not responsive to children’s requests, punishment, coercion, and violence are mostly techniques used by parents to show their authority. Such parenting can cause behavioral problems in the form of aggression, depression, delinquency, and other problems that arise in the later stages of children’s lives (Bahrainian et al., 2014; Haslam et al., 2020). Other studies have also revealed that authoritarian parenting styles can prevent children’s opportunities to learn and open up new worlds (Özgür, 2016). Accordingly, permissive parenting has the characteristics of high warmth but a low level of control. Permissive parenting can cause behavioral problems in children outside the home (Fletcher et al., 2008), which has an impact on the permissive parenting style on online behavior, namely that children have behavior that is dependent on the use of devices, can be manipulated by strangers, and inappropriate access content (Özgür, 2016), lead to cyberbullying and aggression (Martínez et al., 2019). Therefore, the hypothesis is provided as below.

H5

Parenting style positively affects children behavior problem

2.6. Digital literacy and children behavior problem

The use of gadgets in Indonesia began with the economic boom in Asia in the 1980s, which created a new middle class in Indonesia, resulting in a high purchasing power of technology in society. The Indonesian Child Protection Commission survey stated that as many as 76.8% of children in Indonesia were allowed by their parents to operate devices (KPAI, 2020). In this study, the gadget that the most popular and widely used in Indonesia is Smartphone with various platforms and models. Several studies have shown that the use of gadgets for children can trigger aggressive behavior, addiction, and early sexual behavior (Haug et al., 2015; Guxens et al., 2019).

For early childhood, the gadgets is adopted to communicate and play games, searching and browsing, or watching videos and social media. Children tend to be exposed to use in the bedroom and spend much time on devices. More than half of the child population in Indonesia is given access by parents to use gadgets (Hendriyani et al., 2012). Previous research stated that some parents are aware of the educational values of devices such as those in digital games, and approximately 80% of these parents even allow their children to upload their applications (Crescenzi-Lanna, 2020). Some parents agree that gadgets can provide opportunities for children to learn, increase creativity, open up the world to children, and seek interesting information (Özgür, 2016). The use of devices in children can improve good communication skills, generally in children aged five years (Verenikina et al., 2016), but this can happen if there is an excellent ability to use devices in children and parents (Polizzi, 2020). Thus, the hypothesis is provided as follows.

H6

Digital literacy positively affects children behavior problem

3. Method and materials

3.1. Sample and data collection

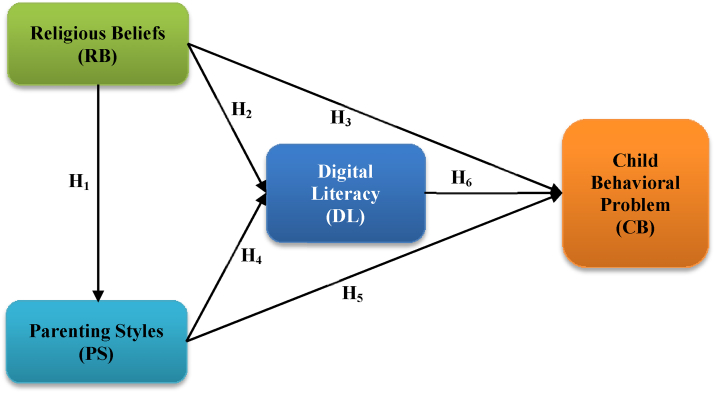

This study aims to understand how parents' belief in the existence of God and his teachings can affect the application of parenting styles, deviant behavior in children, and the use of gadgets that contain online activities in children who are the intervening models in this study (see Figure 1). The construct in Figure 1 was developed from prior studies and relevant theories. This study used gathered data from online administered among parents who are caring children in the age of 2–7 years. This study adopted online questionnaires via google forms which were distributed via social medias, i.e., Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp and Telegram to collect the data. The survey was sent to 414 families, and all of the returned questionnaires is fulfilled the criteria that can be used for analysis. In this study, we have no limitation on six religions in Indonesia: Islam, Christianity, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism as the official religion, with Islam as the majority religion. However, we also open for non-believers to involve to this study as long as to meet the criteria in this research.

Figure 1.

The research Design.

Table 1 informs the detail of respondents engaged in this survey. In general, despite the fact that we opened the questionnaires to be fulfilled by parents that meet the criteria (father, mother, and other family members), the surprising finding is that the questionnaires were completed by mothers (100%). In detail, the participants in this study were parents (mother) that caring children in the range of five and six years old, while the lowest percentagepercentage was parents with children in two years old (9%). Most participants in this study have bachelor degree with the percentage of approximately 59 percent and the least percentage was master and doctoral holder. Parents who incorporated in this research came from various religions which dominated by Moslem considering Indonesia has dominated with Moslem population. The voluntary respondents were asked for their anonymity, and Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Kalijaga performed the ethical issues in this study.

Table 1.

The demographic respondents.

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Children Age | ||

| 2 | 32 | 9% |

| 3–4 | 165 | 39% |

| 5–6 | 174 | 42% |

| 7 | 43 | 10% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 414 | 100% |

| Male | - | - |

| Education Level | ||

| High School | 100 | 24% |

| Bachelor | 241 | 59% |

| Post graduate (Master and Doctoral) | 73 | 17% |

| Religion | ||

| Moslem | 321 | 77.5% |

| Non-Moslem | 93 | 22.5% |

3.2. Instruments development

The construct of the questionnaire was adapted from previous research with slight modifications. The questionnaire includes 35 statements that frame the respondent’s profile and variables that you want to know. The instrument of religious belief (RB) was adapted from the centrality of religiosity scale questionnaire developed by Huber and Huber (2012). In addition, parenting style (PS), digital literacy (DL), and children’s negative behavior (CB) were adapted from the instrument developed by Konok et al. (2020). Each construct was measured using a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

3.3. Measurement and structural model

The assessment of the outer model and inner model in this study was carried out using SEM-PLS. The basic rationale of using this method is that SEM-PLS has the advantage that previous theories have not been adequately validated. The main purpose of this study is to maximize explained variance in the dependent construct but additionally to examine the data based on measurement model (Hair et al., 2017). It is a multivariate estimates method that can be used to describe the simultaneous linear relationship between variables involved in this study. The two main criteria used in the analysis of this measurement model include validity and reliability (Hair et al., 2014). The first step in evaluating the outer model in the PLS analysis is testing to ensure that the instrument used is valid and reliable. Cronbach Alpha is a reinforcement of construct reliability (Hair et al., 2014), where a score that exceeds 0.6 indicates good construct reliability. Two types of validity tests were carried out, namely convergent validity and discriminant validity test. Furthermore, to assess the structural model, there are several steps, namely 1) collinearity test, 2) assessing path coefficients, 3) assessing Goodness of Fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Hair et al., 2014).

4. Results

4.1. The outer model evaluation

The first estimation is convergent validity by using the AVE (Average Variance Extracted) measure, which is higher than 0.5, indicates that the construct explains more than half of the indicator variance. As shown in Table 2, the CR value for each construct ranges from 0.836-0.938, exceeding 0.5 as the limit value to achieve the construct reliability criteria (Hair et al., 2014).

Table 2.

The result of the outer model calculation.

| Construct | Item | Loading | Cronbach Alpha | C.R | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious Belief (RB) | RB 2 | 0.764 | 0.924 | 0.922 | 0.665 |

| RB 3 | 0.633 | ||||

| RB 4 | 0.692 | ||||

| RB 5 | 0.860 | ||||

| RB 6 | 0.908 | ||||

| RB 7 | 0.891 | ||||

| RB 8 | 0.650 | ||||

| RB 9 | 0.912 | ||||

| RB 10 | 0.786 | ||||

| Parenting Style (PS) | PS 3 | 0.659 | 0.702 | 0.886 | 0.632 |

| PS 6 | 0.848 | ||||

| PS 7 | 0.863 | ||||

| Digital Literacy (DL) | DL 1 | 0.798 | 0.846 | 0.836 | 0.565 |

| DL 2 | 0.817 | ||||

| DL 4 | 0.731 | ||||

| DL 5 | 0.678 | ||||

| DL 6 | 0.797 | ||||

| DL 8 | 0.676 | ||||

| Child Behavior (CB) | CB 1 | 0.816 | 0.899 | 0.938 | 0.665 |

| CB 2 | 0.864 | ||||

| CB 3 | 0.841 | ||||

| CB 4 | 0.744 | ||||

| CB 5 | 0.817 | ||||

| CB 6 | 0.806 |

The discriminant calculation can also be strengthened in Table 3. The application of the heteroit-monotrait ratio can be used as a measure of discriminant validity. The test results for each variable in Table 3 show that the heteroit-monotrait ratio is less than 0.9, which means the variable achieved the discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

| CB | MU | PS | RB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Behavior (CB) | ||||

| Digital Literacy (DL) | 0.188 | |||

| Parenting Style (PS) | 0.475 | 0.411 | ||

| Religious Belief (RB) | 0.128 | 0.341 | 0.276 |

The correlation matrix in Table 4 informs primary support for the hypothesis and confirms the forecasting relationship. From the six proposed hypotheses, four were accepted, and the rest hypotheses were rejected. The outcome in Table 4 shows that RB can impact PS and DL with t-value of 3.653 and 4.889, respectively. However, RB failed in predicting CB since the p-value of 0.6333. At the same time, PS can influence DI and CB with t-value of 5.310 and 7.267. Lastly, the statistical calculation remarks that DL has no influence on CB and declines the sixth hypothesis.

Table 4.

Coefficient test and hypothesis testing.

| Hypotheses | Relationship | T-value | P-value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | RB→PS | 3.653 | 0.000 | Approved |

| H2 | RB→DL | 4.889 | 0.000 | Approved |

| H3 | RB→CB | 0.478 | 0.633 | Rejected |

| H4 | PS→Dl | 5.310 | 0.000 | Approved |

| H5 | PS→CB | 7.267 | 0.000 | Approved |

| H6 | DL→CB | 0.482 | 0.630 | Rejected |

Note: RB = Religious belief; PS = Parenting style; DL = Digital literacy; CB = Children behavior.

4.2. Inner model assessment

The measurement model shows adequate convergent validity and discriminant validity. Therefore, the next step in PLS analysis is to develop an inner model that can be used to assess the relationship between constructs. All data were run using 500 bootstrap samples through 130 cases.

4.3. Collinearity

The variance inflation factor (VIF) has a value higher than 5.00 (Hair et al., 2014). The test results show that the range of inner VIF is in the value of 1.175–3.868, meaning that there are no collinearity issues.

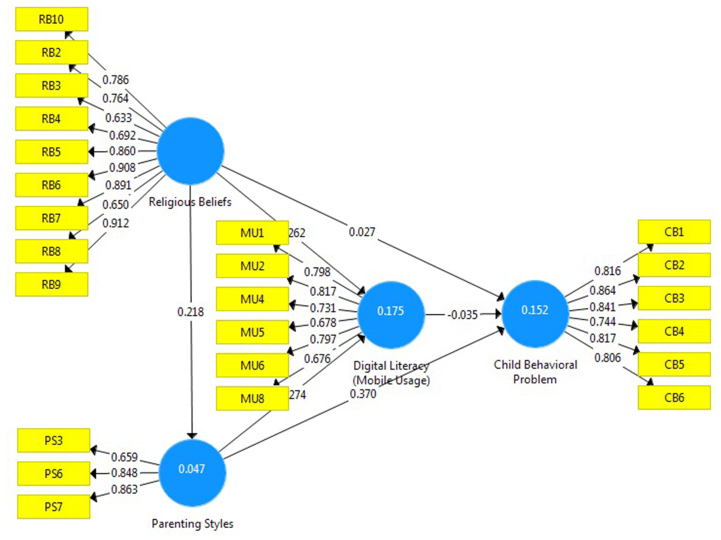

4.4. Path analysis

Path coefficients are also used to evaluate the inner model. T-statistics were estimated using a bootstrap resampling procedure. The bootstrap procedure is a non-parametric approach used to estimate the accuracy of the SEM-PLS estimation. Bootstrapping results show the stability of the study. In this study, the data were run using 500 bootstrap samples. As shown in Table 4 and Figure 2, there are four accepted hypotheses considering the p-value for each relationship is at a value of 0.000 less than 0.05.

Figure 2.

The model estimation.

4.5. Goodness of Fit (GoF)

Goodness of fit (GoF) test results can be seen from the value of Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.08, then the model will be considered suitable or appropriate. Then, the Normal Fit Index (NFI) value produces a value between 0 and 1. The closer to 1, the better or in accordance with the model built (Hu and Bentler, 1999). The SRMR value in Table 5 shows the number 0.069. This value is less than 1.10 or 0.08, so the model is considered appropriate. Next is the NIF value, which shows the number 0.823, which is getting closer to 1, meaning that it can be stated that the model is considered appropriate.

Table 5.

Goodness of fit (GoF).

| Saturated Model | |

|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.069 |

| d_ULS | 1.439 |

| d_G | 0.470 |

| Chi-Square | 1104.379 |

| NFI | 0.823 |

5. Discussion

The first objective of this study was to examine the relationship between religious beliefs and their effect on parenting style. This study confirms that religious beliefs can affect parenting styles and this finding is relevant to previous research, which states that religious beliefs in parents can influence the parenting applied to children (Boyatzis, 2004; Krok, 2018). Parents' religious beliefs can affect family interactions by prohibiting something that is unacceptable. This happens to gain value, and provide support, and determine purpose and meaning. This finding also strengthens the study of Riany et al. (2017) which remarked that high parental religious beliefs tend to apply strict parenting, in the sense that children must obey parental orders and the children view is lower than parents. It becomes a belief in parents that when children do not obey their parents' order, thus they will receive punishment in spiritual matters.

In addition to the first hypothesis, there is a negative influence between religious belief and digital literacy in children. According to Stout and Buddenbaum (1996), the relationship between religion and the use of technology, in this case, is that digital literacy has a negative result. It implies that the higher the religious belief in a person, the lower the use of children's gadgets. The fundamental rationale is that religion is an institution that holds traditional moral values as beliefs. The results of this study indicate that participants separate religious beliefs from digital literacy. This condition is very rational in the context of Indonesia, where religious beliefs are still considered separate from everyday life. This, of course, is in stark contrast to the US society who considers religion and mass media in this case digital literacy as very urgent elements. Digital literacy infused by religion belief creates a sense of tolerance, understands issues clearly, and is not easily provoked by false news (Stout and Buddenbaum, 2002; Cohen, 2012).

On the other hand, technology or gadgets are inventions of modern society in which many introduce secular or non-traditional cultures that are contrary to the core of religious beliefs. The results of this study are in line with the study of Schroeder et al. (1998) that online religious experience causes religion to be uprooted from its real place, real adherents, real shared feelings and cultural harmony, and collective consciousness. This finding supports an earlier study by Paine (2015), which remarked that religious beliefs such as participating in routine religious activities negatively affect the ability to use gadgets. The rational reason is that the use of gadgets is a futile job and does not contribute to religious beliefs. Furthermore, the results also strengthen a prior study by Armfield and Holbert (2003), which stated that the more religious person tends to affect in reducing of using the Internet due to this technology is built on the ethos of a secular worldview, which can prevent religious people from using and utilizing the Internet.

The next finding confirms some studies which state that religious beliefs in parents can affect behavior in children (Chamratrithirong et al., 2013; Li et al., 2018; Petro et al., 2018). Meanwhile, in this study, the psychological aspect that was tested was more focused on the negative behavior of the child. The test results showed that the level of parental religion was not related to the negative behavior of the child. The fourth and fifth hypotheses indicate that the authoritarian parenting style has an influence on digital literacy and negative behavior in children. The results of this study are also relevant to previous recent work by (Haslam et al., 2020; Konok et al., 2020; Lau and Power, 2020). Valcke et al. (2010) also confirmed that the intensity of the use of gadgets was more commonly found in children whose parents applied permissive parenting.

At the same time, draw a common thread between these findings and the literature review where the research subjects are teenagers. Thus, the general concept of mental health problems is emphasized, where indicators and behavioral expressions of mental problems differ between adolescents and children, for example. Expression of anger in early childhood is different from that of adolescents, or the form of aggressive behavior in early childhood is different from that of adolescents. In contrast, less intensity was found in parents who applied authoritarian parenting. The results of Valcke et al. (2010) research is supported by the results of research by Bahrainian et al. (2014) and Özgür (2016), which state that parents who apply permissive parenting to children can result in excessive use of gadgets, causing addiction.

Authoritative parenting provides opportunities for children to use gadgets but on the condition that (for example, after the child has finished doing their work) this parenting style is the most ideal among the others. Authoritarian parenting does not provide opportunities for children to adopt gadgets, parents only show photos/videos to children without children being given independent access. This parenting pattern can cause problems with the children’s world being less open to new things. The last finding in this study shows that digital literacy does not affect children’s negative behavior. This finding reinforces previous research, which states that negative behavior resulting from the use of gadgets is due to excessive use intensity (Haug et al., 2015; Cha and Seo, 2018; Guxens et al., 2019) without being balanced by significant digital competence and digital literacy, namely, an understanding of technology and the critical and responsible use of technology (Gilster, 1997; Meyers et al., 2013). This study emphasizes that the use of gadgets must be balanced with digital literacy so that it can eliminate or minimize the negative impact of technology.

6. Conclusion

This research aims to examine factors influencing the negative behavior of children in Indonesia. This study has six hypotheses, of which four are accepted, and the rest are rejected. The results of this study indicate that religious beliefs have no effect on children’s negative behavior and being a universal understanding that affirms that religious beliefs of the parents do have a direct bearing on child’s rearing, thus, impacting his/her behaviour. However, the parenting style of parents can explain the intensity of using gadgets in children. In addition, parenting style has a negative relationship with digital literacy (device use competence), while parenting style also positively affects children’s negative behavior. Then, digital literacy does not affect children’s negative behavior which implicates on a balanced use of digital gadgets. Based on the results of this study, this found that parents have conservative thoughts because they are bound by religious beliefs who still think that change is a living phenomenon that is prohibited in life, so this can result in a less open world for parents and children’s behavior. This study lies some limitations. First, it uses quantitative methods with limited variables, especially in digital literacy, which is solely incorporated with the competence of using gadgets. While many factors can influence children’s behavior, it is recommended that further researchers can develop by choosing other variables that also influence children’s behavior. Second, the returned questionnaires were filled out solely by the mother instead of other family members; thus, it can be considered the demographic respondents to obtain a better understanding. Third, all participants involved in this study are parents of certain religions, and future researchers consider non-believers who may provide different perspectives.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Sigit purnamma and Agus Wibowo: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Bagus Shandy Narmaditya; Qonitah Faizatul Fitriyah and Hafidh Aziza: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A

| No | Statement | Alternative Answer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | N | DA | SDA | ||

| 1 | I often think about religious issues or problems | |||||

| 2 | I believe that God exists | |||||

| 3 | I am often involved in religious activities | |||||

| 4 | I often experience situations where I feel that God has a hand in my life | |||||

| 5 | I believe that there is life in the afterlife, such as the immortality of the soul/the day of resurrection | |||||

| 6 | I think doing worship is important | |||||

| 7 | I think praying is important | |||||

| 8 | I often get information about religion through radio, television, internet, newspapers or books | |||||

| 9 | I think the power of God really exists | |||||

| 10 | Religion teaches goodness | |||||

| 11 | Religion is not anti-change | |||||

| No | Statement | Alternative Answer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | N | DA | SDA | ||

| 1 | We show children how to operate gadgets | |||||

| 2 | We provide opportunities for children to operate gadgets, but with limited time | |||||

| 3 | We give children the opportunity to operate the gadget but we lock the screen layer | |||||

| 4 | We provide opportunities for children to operate gadgets but under supervision (beside children) | |||||

| 5 | We provide opportunities for children to operate gadgets on conditions (for example if the child behaves well) | |||||

| 6 | We do not give children the opportunity to operate the gadget, we only show/view photos/videos together | |||||

| 7 | We do not give children the opportunity to operate the gadget/We take it from the child/We tell the child to put it down | |||||

| 8 | We provide free opportunities for children to operate gadgets | |||||

| No | Statement | Alternative Answer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | N | DA | SDA | ||

| 1 | Child opens/accesses movies/videos/cartoons | |||||

| 2 | Children playing games | |||||

| 3 | The child pretends to play the phone/holds the cell phone to the ear | |||||

| 4 | Children access music | |||||

| 5 | Child downloads apps/games | |||||

| 6 | Children access programs/applications | |||||

| 7 | Child makes and receives calls | |||||

| 8 | Children watching children's movies/videos | |||||

| No | Statement | Alternative Answer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | N | SA | SDA | ||

| 1 | Gadgets can cause behavioral problems in children | |||||

| 2 | Gadgets can cause aggressive/irritating/tension behavior in children | |||||

| 3 | Gadgets can cause depression/bad mood in children | |||||

| 4 | Gadgets can worsen fantasy/imagination/and creativity in children | |||||

| 5 | Gadgets can cause children to lose interest/more difficult to be busy with other things | |||||

| 6 | Gadgets can damage social relationships/cause problems in forming relationships/become “anti-social”/become introverted/cause children to like to be alone | |||||

| 7 | Gadgets can increase openness in children | |||||

| 8 | Gadgets can improve skills in children | |||||

| 9 | Gadgets can help children to find information about interesting things | |||||

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Armfield G.G., Holbert R.L. The relationship between religiosity and Internet use. J. Media Relig. 2003;2(3):129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrainian S.A., Alizadeh K.H., Gorji O.H., Khazaee A. 2014. Relationship of Internet Addiction with Self-Esteem and Depression in University Students; pp. 86–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski J.P., Xu X., Bartkowski S. Mixed blessing: the beneficial and detrimental effects of religion on child development among third-graders. Religions. 2019;10(1) [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. J. Early Adolesc. 1991;11(1):56–95. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis . Sage; 2004. The Handbook of Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S.B. 1995. Behavior Problems in Preschool Children: A Review of Recent Research. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha S.S., Seo B.K. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction in middle school students in Korea: prevalence, social networking service, and game use. Health Psychol. Open. 2018;5(1) doi: 10.1177/2055102918755046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamratrithirong A., Miller B.A., Byrnes H.F., Rhucharoenpornpanich O., Cupp P.K., Rosati M.J., Fongkaew W., Atwood K.A., Todd M. Intergenerational transmission of religious beliefs and practices and the reduction of adolescent delinquency in urban Thailand. J. Adolesc. 2013;36(1):79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Y. Media and religion: foundations of an emerging field. Commun. Res. Trends. 2012;31(4):39. [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzi-Lanna L. Emotions, private speech, involvement and other aspects of young children’s interactions with educational apps. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020;111 [Google Scholar]

- Dempster R., Wildman B., Keating A. The role of stigma in parental help-seeking for child behavior problems. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2013;42(1):56–67. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.700504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- F. Hair Jr J., Sarstedt M., Hopkins L., Kuppelwieser, V. G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) Euro. Bus. Rev. 2014;26(2):106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Fikkers K.M., Piotrowski J.T., Valkenburg P.M. A matter of style? Exploring the effects of parental mediation styles on early adolescents’ media violence exposure and aggression. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;70:407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher A.C., Walls J.K., Cook E.C., Madison K.J., Bridges T.H. Parenting style as a moderator of associations between maternal disciplinary strategies and child well-being. J. Family Issues. 2008;29(12):1724–1744. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. The future of an illusion. W. W. Norton & Company; New York: 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Glock & Stark . University of California; 1966. Religion and Society in Tension. [Google Scholar]

- Gilster P. Wiley Computer Pub; 1997. Digital Literacy. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J., Halász G., Krawczyk M., Leney T., Michel A., Pepper D., Putkiewicz E., Wiśniewski J. 2009. Key competences in Europe: opening doors for lifelong learners across the school curriculum and teacher education. (CASE Network Report No 87). [Google Scholar]

- Guxens M., Vermeulen R., Steenkamer I., Beekhuizen J., Vrijkotte T.G.M., Kromhout H., Huss A. Radiofrequency electromagnetic fields, screen time, and emotional and behavioural problems in 5-year-old children. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2019;222(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Hult G.T.M., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M., Thiele K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2017;45(5):616–632. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam D., Poniman C., Filus A., Sumargi A., Boediman L. Parenting style, child emotion regulation and behavioral problems: the moderating role of cultural values in Australia and Indonesia. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2020;56(4):320–342. [Google Scholar]

- Haug S., Paz Castro R., Kwon M., Filler A., Kowatsch T., Schaub M.P. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. J. Behav. Addict. 2015;4(4):299–307. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriyani Hollander, E., d’Haenens L., Beentjes J.W.J. Children’s media use in Indonesia. Asian J. Commun. 2012;22(3):304–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.T., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huber S., Huber O.W. The centrality of religiosity scale (CRS) Religions. 2012;3(3):710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B.R., Jang S.J., Larson D.B., De Li S. Does adolescent religious commitment matter? A reexamination of the effects of religiosity on delinquency. J. Res. Crime Delinquen. 2001;38(1):22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kominfo . Director General of PPI: Internet User Penetration Survey in Indonesia An Important Part of Digital Transformation. Kominfo; Jakarta: 2020. https://kominfo.go.id/index.php/content/detail/30653/dirjen-ppi-survei-penetrasi-pengguna-internet-di-indonesia-bagian-penting-dari-transformasi-digital/0/berita_satker Available online at: [Google Scholar]

- Konok V., Bunford N., Miklósi Á. Associations between child mobile use and digital parenting style in Hungarian families. J. Child. Media. 2020;14(1):91–109. [Google Scholar]

- KPAI . KPAI survey: 76.8 percent of children use devices outside study hours. KPAI; Jakarta: 2020. https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1420670/survei-kpai-768-persen-anak-gunakan-gawai-di-luar-jam-belajar Available online at: [Google Scholar]

- Krok D. Examining the role of religion in a family setting: religious attitudes and quality of life among parents and their adolescent children. J. Fam. Stud. 2018;24(3):203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lau E.Y.H., Power T.G. Coparenting, parenting stress, and authoritative parenting among Hong Kong Chinese mothers and fathers. Parenting. 2020;20(3):167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lemish D., Elias N., Floegel D. Look at me!” Parental use of mobile phones at the playground. Mobile Media Commun. 2020;8(2):170–187. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Subrahmanyam K., Bai X., Xie X., Liu T. Viewing fantastical events versus touching fantastical events: short-term effects on children’s inhibitory control. Child Dev. 2018;89(1):48–57. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A., Grudziecki J. DigEuLit: concepts and tools for digital literacy development. Innov. Teach. Learn. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2006;5(4):249–267. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez I., Murgui S., Garcia O.F., Garcia F. Parenting in the digital era: protective and risk parenting styles for traditional bullying and cyberbullying victimization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019;90:84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers E.M., Erickson I., Small R.V. Digital literacy and informal learning environments: an introduction. Learn. Media Technol. 2013;38(4):355–367. [Google Scholar]

- Moon S.J., Bai S.Y. Components of digital literacy as predictors of youth civic engagement and the role of social media news attention: the case of Korea. J. Child. Media. 2020;14(4):458–474. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M., Collins W.B., Sparks G.G., Welch J.R. Identifying relevant anti-science perceptions to improve science-based communication: the negative perceptions of science scale. Soc. Sci. 2018;7(4):64. [Google Scholar]

- Munawar M., Amri A. Pengaruh Gadget Terhadap Interaksi Dan Perubahan Perilaku Anak Usia Dini Di Gampong Rumpet Kecamatan Krueng Barona Jaya Kabupaten Aceh Besar. Jurnal Ilmiah Mahasiswa Fakultas Ilmu Sosial & Ilmu Politik. 2018;3(3):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Myers S.M. An interactive model of religiosity inheritance: the importance of family context. Am. Socio. Rev. 1996;61(5):858–866. [Google Scholar]

- Newton A.T., Mcintosh D.N. 39–58. 2010. Specific Religious Beliefs in a Cognitive Appraisal Model of Stress and Coping. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nnadozie E.E., Iorfa S.K., Ifebigh O.O. Parenting style and religiosity as predictors of antisocial behavior among Nigerian Undergraduates. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2018;44(5):624–631. [Google Scholar]

- Özgür H. The relationship between Internet parenting styles and Internet usage of children and adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;60:411–424. [Google Scholar]

- Paine . 2015. Exploring the Relationship between Religion and Internet Usage (Paper Presented at the Meeting of the International Communication Association) [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis S., Zaranis N., Kalogiannakis M. Parental involvement and attitudes towards young Greek children’s mobile usage. Int. J. Child-Comput. Interact. 2019;22 [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis S., Alexandraki F., Zaranis N. Mobile device use among preschool-aged children in Greece. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021:1–34. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G.R. The next Generation of PMTO models. Behav. Ther. 2005;28(2):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Petro M.R., Rich E.G., Erasmus C., Roman N.V. The effect of religion on parenting in order to guide parents in the way they parent: a systematic review. J. Spirituality Ment. Health. 2018;20(2):114–139. [Google Scholar]

- Petts R.J. Parental religiosity, religious homogamy, and young childrens well-being. Sociol. Relig.: Q. Rev. 2011;72(4):389–414. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering J.A., Sanders M.R. Reducing child maltreatment by making parenting programs available to all parents: a case example using the triple P-positive parenting program. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016;17(4):398–407. doi: 10.1177/1524838016658876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polizzi G. Digital literacy and the national curriculum for England: learning from how the experts engage with and evaluate online content. Comput. Educ. 2020;152(February) [Google Scholar]

- Rathus S.A. Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2014. Childhood & Adolescence : Voyages in Development/ [Google Scholar]

- Riany Y.E., Meredith P., Cuskelly M. Understanding the influence of traditional cultural values on Indonesian parenting. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2017;53(3):207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Saniyyah L., Setiawan D., Ismaya E.A. Dampak Penggunaan Gadget terhadap Perilaku Sosial Anak di Desa Jekulo Kudus. Edukatif: J. Ilmu Pendidik. 2021;3(4):2132–2140. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder R., Heather N., Lee R.M. The sacred and the virtual: religion in multi-user virtual reality. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 1998;4(2) [Google Scholar]

- Stout & Buddenbaum . Sage; 1996. Religion and Mass Media: Audiences and Adaptations. [Google Scholar]

- Stout D.A., Buddenbaum J.M. Genealogy of an emerging field: foundations for the study of media and religion. J. Media Relig. 2002;1(1):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Strayer J., Roberts W. Children’s anger, emotional expressiveness, and empathy: relations with parents’ empathy, emotional expressiveness, and parenting practices. Soc. Dev. 2004;13(2):229–254. [Google Scholar]

- Terras M.M., Ramsay J. Family digital literacy practices and children’s mobile phone use. Front. Psychol. 2016;7(DEC):1957. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcke M., Bonte S., De Wever B., Rots I. Internet parenting styles and the impact on Internet use of primary school children. Comput. Educ. 2010;55(2):454–464. [Google Scholar]

- Verenikina I., Kervin L., Rivera M.C., Lidbetter A. Digital play: exploring young children’s perspectives on applications designed for preschoolers. Global Stud. Child. 2016;6(4):388–399. [Google Scholar]

- Volling B.L., Mahoney A., Rauer A.J. Sanctification of parenting, moral socialization, and young children’s conscience development. Psychol. Relig. Spirituality. 2009;1(1):53–68. doi: 10.1037/a0014958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P.D., Hunter W.M., Seyer E., Sammut S., Breuninger M.M. Religious/spiritual struggles and perceived parenting style in a religious college-aged sample. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2019;22(5):500–516. [Google Scholar]

- Yananda M., Jiangliang Q., Chen C. The relationships between child maltreatment and child behavior problems. Comparative study of Malawi and China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020;105533 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.