Abstract

Airway smooth muscle plays a pivotal role in modulating bronchomotor tone. Modulation of contractile and relaxation signaling is critical to alleviate the airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) associated with asthma. Emerging studies examining the phenotype of ASM in the context of asthma provide rich avenues to develop more effective therapeutics to attenuate the AHR associated with the disease.

Keywords: Asthma, Bronchoconstriction, Bronchodilator agents

A number of factors influence the development of asthma and increase the incidence of the disease. Airway smooth muscle (ASM) represents the pivotal cell modulating bronchomotor tone. A more thorough understanding of the phenotypic and genotypic changes to ASM in the context of asthma will help to elucidate mechanisms of the development of a hypercontractile phenotype that is characteristic of the disease and in identification of therapeutic targets to alleviate bronchoconstriction or augment bronchodilation with current therapies.

Asthma-derived ASM exhibits a hypercontractile phenotype

Altered mechanisms of ASM shortening in asthma

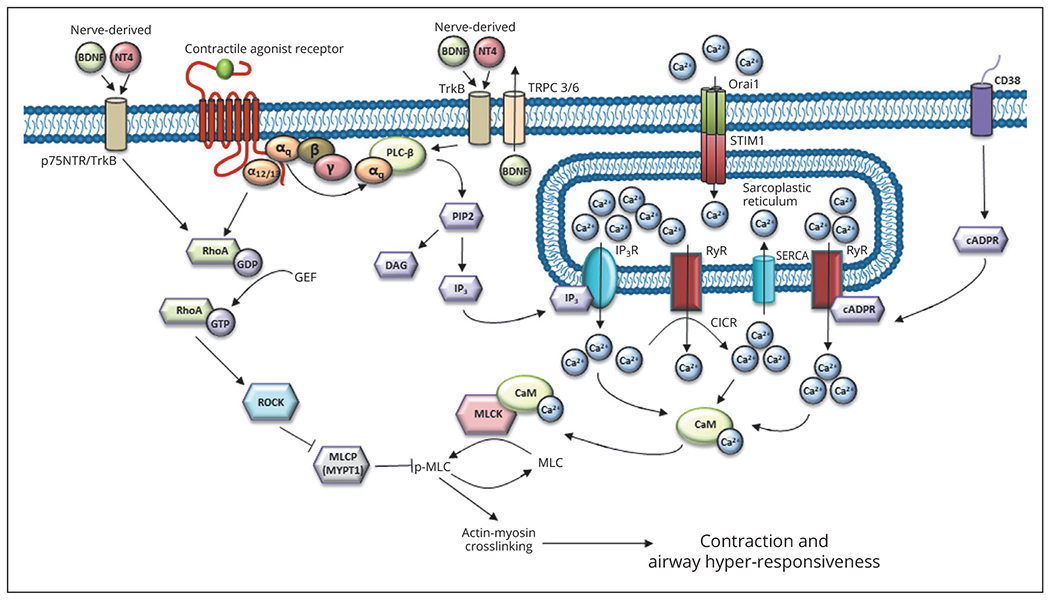

Asthma, an airway inflammatory disease, manifests as recurrent episodes of airflow obstruction. The inflammatory environment alters shortening of the ASM,1–3 that in turn modulates bronchomotor tone. Modulation of intracellular kinases, enzymes, and ion channels underly three main modes of regulation of ASM contraction, and can be classified into four main categories: calcium-dependent (Figure 1), calcium-independent (Figure 1), calcium-sensitization (Figure 1), nerve-mediated mechanisms (Figure 1), and modulation of actin dynamics (Figure 2). Asthma, and the inflammatory milieu characteristic of the disease, can phenotypically alter how ASM shortens.

Figure 1.—

Calcium-dependent and –independent, and nerve-mediated, pathways which modulate ASM contraction and AHR. cADPR, cyclic-ADP-ribose; CaM, calmodulin; CD38, cluster of differentiation 38; CICR, Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release; DAG, sn-1,2-diacylglycerol; GEF, guanidine nucleotide exchange factors; IP3, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate; IP3R, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; MLC, myosin light chain; MLCK, myosin light-chain kinase; MYPT1, myosin phosphatase target subunit-1 of myosin light-chain phosphatase (MLCP); Orai1, store operated channel proteins; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol (4,5 )-bis phosphate; RhoA-GDP, inactive form of RhoA; RhoA-GTP, active form of RhoA; ROCK, Rho-associated kinase; RyR, ryanodine receptor; SERCA, sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase; STIM1, stromal interaction molecule 1; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; NT4, neurotrophin 4 receptor; TrkB, tropomyosin receptor kinase B/p75 neurotrophin receptor; TRPC, transient receptor potential cation channel 3/6; PLC beta, phospholipase C.

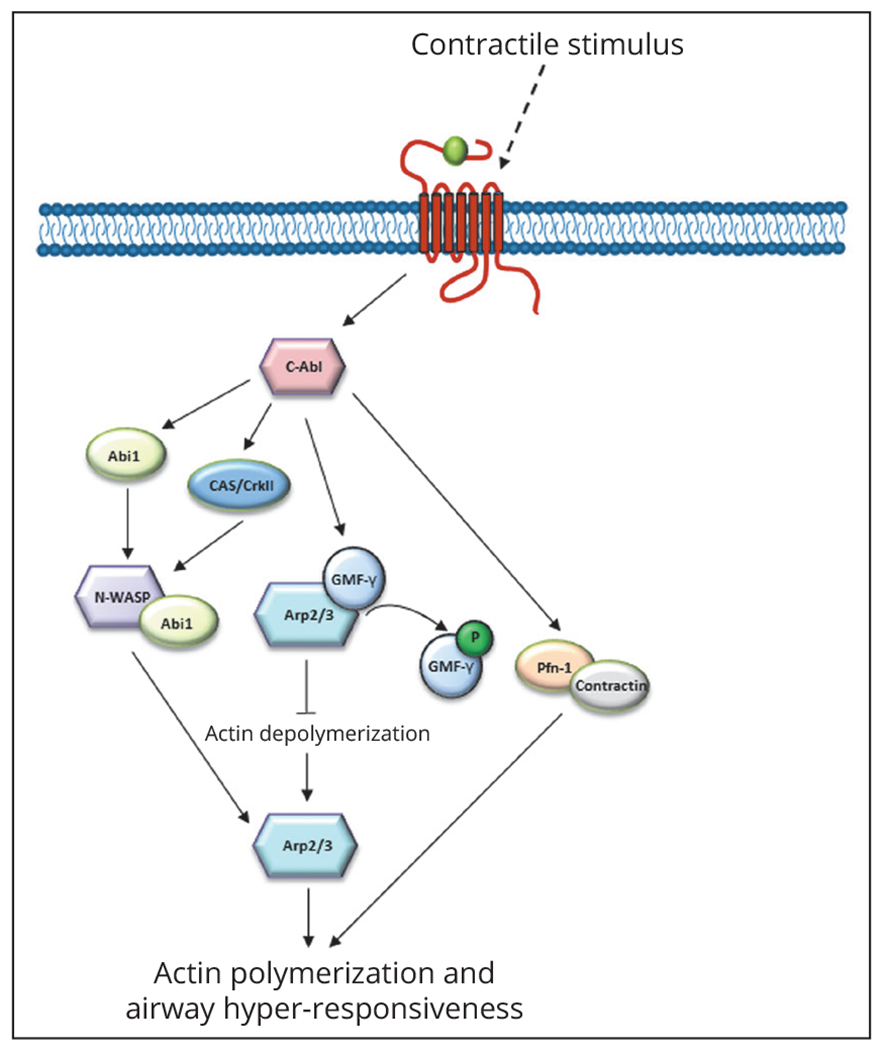

Figure 2.—

Actin remodeling pathways which modulate ASM contraction and AHR. C-Abl, c-abl tyrosine kinase; Abi1, c-Abl adaptor 1; N-WASP, neural wiskott-aldrich protein; Arp2/3, actin-related protein 2/3; GMFγ, glia maturation factor γ; Pfn-1, profilin-1; CAS/CrkII, Crk-associated substrate.

Calcium-dependent signaling in ASM

Binding of contractile agonists to G-protein couple receptors (GPCRs) within the cell membrane of ASM activates calcium (Ca2+)-dependent signaling pathways that elicit contractile responses in ASM.4–9 Described below are some of the calcium-dependent pathways that are activated/altered in asthma-derived ASM.

A role for the inositol triphosphate receptor, ryanodine receptor, and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum ca2+-atpase

These contractile responses are elicited through producing Ca2+ oscillations due to functions of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane Ca2+ channels such as the inositol triphosphate receptors (IP3Rs),9–12 ryanodine receptors (RyRs),5, 8, 11, 13 and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-atpase (SERCA).11, 14 These changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations [Ca2+]i ultimately induce myosin light-chain kinase phosphorylation (pMLC) and contraction of ASM,7 and dysregulation of [Ca2+]i can produce airway hyper-responsiveness that is characteristic of asthma.5, 6, 11, 14

Agonist binding to GPCRs induces activation of phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ) via dissociation of the GPCR Gαq and Gγβ subunits and subsequent binding of the Gα-subunit to PLCβ (as reviewed in9, 11). Activation of PLCβ induces hydrolysis of cytosolic phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bis phosphate (PIP2) into second messenger products inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and sn-1,2-diacylglycerol (DAG).9, 11, 12 IP3Rs on the membrane of the SR bind IP3 and release Ca2+ into the cytosol (as reviewed in 2). It has long been known that IP3 induces [Ca2+]i release from SR stores in ASM.10, 12 Interestingly, not all contractile agonists have been shown to behave similarly with respect to eliciting [Ca2+]i release. It was demonstrated that asthma-derived ASM exhibited a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i release then a slower decline in concentration in response to histamine, which was posited to be a result of IP3-mediated [Ca2+]i mobilization from intracellular stores.15 This study also showed that not all contractile agonists elicited augmented [Ca2+]i release from intracellular stores, where bradykinin (Bk), but not thrombin or histamine, induced more [Ca2+]i release from asthma-derived ASM. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) has been shown to promote increased [Ca2+]i in response to contractile agonists such as Bk, thrombin, and carbachol.4 This suggests that TNFα may elicit increased responses at the GPCR level, leading to increased [Ca2+]i by promoting formation of IP3 in ASM.4, 9 Additionally, it was noted that TNFα induced hyperresponsiveness of human small airways with carbachol stimulation.16

RyRs, located in the SR membrane of ASM, function similarly to IP3Rs and serve to elicit release of [Ca2+]i.5, 6, 8, 11, 13 Following agonist binding to contractile GPCRs, IP3 increases [Ca2+]i and evokes Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR), that in turn increases the probability of [Ca2+]i release through RyR.8 Mathematical analysis of agonist-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations suggest that the RyR is critical in inducing [Ca2+]i store depletion, however, following induction of store emptying from the SR and induction of CICR through RyR, the likelihood of RyR channel opening decreases and IP3R mediates prolonged [Ca2+]i store emptying.8, 11

This increase in [Ca2+]i following contractile agonist stimulation is attenuated through activation of SERCA, which removes [Ca2+]i from the cytosol and replenishes the SR [Ca2+]i stores.11, 14 Expression of SERCA2 is reduced in ASM derived from patients with moderate asthma via immunoblot and immunohistochemistry, and the duration of agonist-induced [Ca2+]i transients is amplified in ASM derived from asthma donors. These data suggest that that [Ca2+]i dysfunction in ASM due to SERCA2 expression may contribute to hyperresponsiveness of the airways that is associated with asthma.14 Additionally, application of Bk, ryanodine, and thapsigargin, three contractile agonists that induce [Ca2+]i store emptying in ASM, resulted in reduced SR [Ca2+]i store refilling following Bk stimulation, suggesting impaired SERCA function in asthma-derived ASM.13

The pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-13 appears key in inducing hyperreactivity of ASM.13, 17, 18 In a mouse ASM, blockade of interleukin 13 (IL-13), completely abrogates AHR responses and administration of IL-13 was capable of inducing AHR over time.18 IL-13 increased [Ca2+]i oscillations in ASM and augmented oscillations following treatment with cysteinyl leukotrienes, key metabolites of arachidonic acid.13 IL-13 was demonstrated to engender hyperresponsiveness to contractile agonists in both ASM and human small airways.16, 19–21 Additionally, inhibitors of RyR and IP3R decreased [Ca2+]i oscillations in ASM following agonist treatment ± IL-13 pre-treatment, suggesting that IL-13 augments signaling pathways involved in production of [Ca2+]i oscillations through activation of the IP3R and RyR.13 Interestingly, irrespective of its role in modulation of exatation-contraction (E-C) coupling in ASM, IL-13 can elicit greater eotaxin-1 release and that SERCA2 siRNA treatment of asthma-derived ASM further increased IL-13-induced eotaxin 1 release from the cells.14

CD38

In airway smooth muscle (ASM), CD38 functions as a transmembrane protein which has been implicated in pathways that mediate [Ca2+]i responses which control contraction and relaxation of ASM and modulate AHR.22–26 Specifically, CD38 influences [Ca2+]i release from the SR via the RyR channel pathway through a secondary messenger, cyclic-ADP-ribose (cADPR).26, 27 cADPR is regulated by the ADP-ribosyl cyclase and cADPR hydrolase enzymatic activity within the membrane-bound CD38 and that cADPR expression promotes release of [Ca2+]i stores from the SR following agonist treatment.22, 26, 27 CD38 has been shown to be critical in maintaining [Ca2+]i stores in ASM cells in response to store-emptying in human ASM (HASM).24

Inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukins (IL) such as IL-13 can contribute to asthma26 through eliciting changes in [Ca2+]i, eliciting AHR. TNFα can modulate the function of HASM cells derived from both asthma and non-asthma donors.28 Studies of CD38 in store-operated [Ca2+]i have revealed that HASM cells treated with TNFα increased expression of CD38 mRNA21, 24, 26 and cADPR enzymatic activity24 and increased store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) in response to SR store emptying,24, 26 and ASM derived from asthma donors exhibits higher levels of CD38 expression with TNFα stimulation. Overexpression of CD38 also increased expression of CD38 mRNA, as well as increased cADPR activity following treatment with TNF-α.24 Additionally, increased expression of CD38, as well as increased cADPR activity in HASM treated with IL-13 has been observed, suggesting a role for CD38 in AHR observed in asthma through modulation of [Ca2+]i in ASM.25

Calcium/Calmodulin and myosin light chain kinase

Smooth muscle contraction is dependent on the interactions between free [Ca2+]i and CaM, which associate and cause a conformational change which allows calcium/calmodulin (CaM) to bind and activate myosin light chain kinase (MLCK).7, 29–31 Decreases in [Ca2+]I dissociate between [Ca2+]i-CaM complexes that induce inactivation of MLCK.30 MLCK regulates contraction within airway smooth muscle cells through phosphorylation of 20-kD regulatory myosin light chains (MLC20), and subsequent actin activation through actomyosin adenosine triphosphate (ATPase), allowing for actin-myosin filaments to elicit ASM contraction.9, 32–34 The interaction between actin and myosin filaments is dependent on increases in [Ca2+]i caused by contractile agonist activation of GPCRs.9, 35 Increased [Ca2+]i activates Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) which phosphorylates MLCK, allowing for further phosphorylation of MLC20 and subsequent contraction of ASM.7, 9

MLCK protein expression and activity is increased in human ASM derived from sensitized airways32, 36 and in asthma-derived ASM. Additionally, presence of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), a cytokine commonly found in the lungs of asthma subjects, increased basal and contractile agonist-induced phosphorylation of MLC20 in HASM31 and both basal and contractile agonist-stimulated narrowing of human small airways, suggesting that the effect of TGF-β1 may contribute to the hyperresponsiveness observed in asthma-derived ASM.

STIM/Orai1

Refilling of SR Ca2+ stores (Ca2+SR) is critical to maintaining homeostasis within airway smooth muscle cells.37–39 Stromal interaction molecules (STIM) proteins, located within the SR, have been implicated in controlling [Ca2+]i following store emptying.38, 40 The N-terminus of STIM acts as a luminal Ca2+ sensor within the SR through a low affinity Ca2+ EF-hand domain which senses Ca2+ store emptying.39 Following store depletion, STIM1 proteins rapidly associate and translocate to junctions between the ER and plasma membrane where STIM1 interacts with Orai1 channel proteins.38, 39, 41 Orai channels that span the plasma membrane of the cells act as store operated channel (SOC) proteins which transduce calcium-release activated [Ca2+]i currents to mediate selective Ca2+ ion entry across the plasma membrane following translocation and coupling with STIM.39 This process is known as SOCE and is critical in maintaining [Ca2+]i homeostasis in the cytosol of airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells.37, 38, 41

Proinflammatory cytokines IL-13 and TNFα have been shown to increase SOCE in ASM following agonist stimulation through increased STIM1 aggregation, increasing contractility and SOCE.41 Additionally, application of TGF-β1 (24 hours) increased basal [Ca2+]i compared to control ASM cells, as well as a larger SOCE Ca2+ influx following store-depletion.41, 42 Interestingly, HASM cells pretreated with IL-13 do not display increased mRNA expression for neither STIM1 nor Orai1 despite displaying increased SOCE.37 This suggests that increased expression of STIM1 and Orai1 may not factor in increased SOCE in HASM cells.

Calcium-independent sensitization pathways

Along with pathways that elicit calcium release, there are pathways by which ASM contracts that are deemed calcium-sensitization pathways. Described below are some of these pathways that are altered in asthma-derived ASM.

Rho/ROCK/MYPT1

Exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and TGF-β, has been shown to increase AHR in ASM activation of pathways that include RhoA43–45 and Rho-associated kinase (ROCK)44 by activating a pathway known as Ca2+ sensitization.44, 46 As discussed previously, exposure to contractile agonists increases [Ca2+]i through Ca2+-dependent pathways that induce SR Ca 2+ store release through channels such as IP3R and RyR. These Ca2+-dependent pathways ultimately induce contractility and AHR in ASM through actin-myosin filament cross bridging following activation of MLCK. Phosphorylation of MLC20 is also regulated in a somewhat Ca2+-independent manner by myosin light-chain phosphatase (MLCP), that dephosphorylates MLC20, stimulating ASM relaxation.33 Under normal conditions, contractility and relaxation of ASM is balancing of expression of MLCK and MLCP.33, 35, 46

Activation of p115-RhoGEF by Gα12/13 and the exchange of inactive RhoA-GDP for RhoA-GTP activates ROCK.46, 47 Ca2+-sensitization occurs through ROCK-dependent phosphorylation of the myosin-binding subunit of MLCP, myosin phosphatase target subunit-1 (MYPT1), leading to inactivation of MLCP.33, 43, 44 Within ASM, inactivated MLCP leads to increased MLC20 phosphorylation by MLCK and enhanced ASM contraction.33, 35, 44, 46 Asthma-derived ASM was found to have greater pMYPT1 than non-asthma ASM.19 Pretreatment with TNF-α in human bronchi has also shown to increase contraction following treatment with contractile agonist histamine.48

A study from Ojiaku et al. showed that treatment of human precision cut lung slices (hPCLS) with TGF-β1 has augments both basal and agonist-induced constriction through increased phosphorylation of MLC20.31 Additionally, this study found that HASM treated with TGF-β1 exhibited increased MYPT1 phosphorylation through increased ROCK activation.31 Other studies have also shown that pretreatment with TGF-β1 increased Rho-associated GEF expression and activity of RhoA, as well as increased expression of MYPT1 and phosphorylation of MLC20 in response to bradykinin-induced contraction.45

Exposure of HASM to TNFα has been shown to increase levels of RhoA-GTP and phosphorylated MYPT1, both of which was completely ablated in HASM pre-treated with a ROCK inhibitor, indicating the effects of TNFα to induce Ca2+ sensitization and AHR through the RhoA/ROCK pathway.48

Actin remodeling-dependent pathways of contraction

As discussed previously, both Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-sensitization pathways contribute to the phosphorylation state of MLC20 and subsequent actin-myosin interactions which control ASM contraction and relaxation. Additionally, in response to a contractile stimulus, actin filaments polymerize in ASM independent of myosin phosphorylation.49, 50 As a result, both actin polymerization and MLC20 phosphorylation are necessary for ASM contractions50 (2). In response to a contractile agonist, soluble actin (G-actin) is converted into insoluble actin (F-actin).49

In ASM, actin polymerization occurs following the production of a contractile stimulus50 which produces phosphorylation and activation of c-Abl tyrosine kinase (c-Abl) leading to a signal cascade.50, 51 C-Abl expression has been found to be increased in ASM derived from severe asthma subjects, indicating a role in regulation of actin remodeling in asthma-derived ASM and AHR development.51 Activation of c-Abl leads the phosphorylation and activation of c-Abl adaptor 1 (Abi1) which associates with neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASP).50 N-WASP, under non-contractile conditions, is found in a conformationally inactive state.50 Contractile forces increase Abi1 activity, leading Abi1 and N-WASP association, rendering N-WASP active and capable of association with actin-related protein 2/3 (Arp2/3) complex which drives actin polymerization.50 Additionally, Crk-associated substrate (CAS) acts as an adaptor protein which helps regulate actin polymerization in ASM.49 Experimentally, Wang et al. demonstrated that acetylcholine (Ach) treatment of ASM and human bronchial rings increased N-WASP/Abi1 association, as well as the formation of a multiprotein complex involving c-Abl, CAS, and Abi1.50 Knockdown of c-Abl or CAS resulted in decreased Abi1/N-WASP association, indicating that both CAS and c-Abl are critical in inducing actin polymerization and could play a role in development of AHR.50

Profolin-1 (Pfn-1), an actin regulatory protein, and Cortactin have also been shown to induce and regulate, respectively, actin polymerization and modulate contraction in ASM.52 Following exposure to ACh, HASM increase associated Pfn-1 and Cortactin as compared to unstimulated HASM, suggesting a time-dependent association of these proteins following induction of contraction.52 In a mouse model, association of Pfn-1 and Cortactin was correlated with increased force generation as well as increased F-actin/G-actin rations in HASM.52 Moreover, disruption of Pfn-1/Cortactin association decreased F-actin/G-actin ratios in HASM, and decreased contraction in human bronchial rings independent of myosin phosphorylation. Interestingly, c-Abl knockdown, but not knockdown of Abi1, reduced phosphorylation of Cortactin and Pfn-1/Cortactin association, indicating that c-Abl may regulate Pfn-1/Cortactin induced actin polymerization in a separate capacity from Abi1 induced actin polymerization.52

Opposingly, an actin depolymerizing factor (ADF)/cofilin family protein, glia maturation factor-γ (GMF-γ), has been shown to bind Arp2/3 under resting conditions.49, 52–54 This binding of an ADF to Arp2/3 may block binding of N-WASP and induction of actin polymerization.55 However, c-Abl activation following contraction induced by ACh phosphondates GMF-γ at Tyr-104 residue that disassociates from Arp2/3 complexes.49, 54, 55 This effect increases levels of F-actin and decreases actin depolymerization within HASM, allowing for increased actin polymerization and contraction independent of myosin phosphorylation.55

Nerve-meditated mechanisms of contraction

Contraction of HASM can be modulated through nerve-mediated responses that are generated through ASM innervation.56, 57 Parasympathetic nerves, arising from brain stem and vagal origins, release ACh through muscarinic receptors (mainly M3) which induce cholinergic contractile responses from ASM tissue.56, 57 Electric field stimulation (EFS) has been used to demonstrate nerve-mediated bronchoconstriction in human precision-cut lung slices (hPCLS)56, 58 and human bronchi tissue57 through parasympathetic cholinergic pathways. Notably, non-cholinergic responses to EFS have also been demonstrated in hPCLS, though less effectively.58 Release of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) from postganglionic cholinergic nerves has also been shown to induce bronchoconstriction in human airway tissue through release of ACh.59

Non-cholinergic contraction within ASM can be attributed to nerve-derived factors such as neurotrophins (NT) and neurotrophin receptors (NTR),56, 60, 61 which are produced through ASM innervation with postganglionic non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC) nerves.56, 60, 62 In bronchial asthmatic patient serum, enhanced production of NT nerve growth factor (NGF) was found.63, 64 Neurotrophins such as brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin 4 (NT4) and their receptor, Tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB), have also been associated with asthmatic airways.56, 60, 64

The ability for nerve-mediated signaling to modulate Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-sensitization pathways within ASM such as PLC/IP3 and RhoA, respectively, has been reviewed.65, 66 TrkB can upregulate Ca2+-dependent signaling pathways including PLC/IP3 within ASM,66 that could promote development of AHR in asthma. Additionally, the p75NTR receptor, a low affinity BDNF receptor, has been observed to modulate RhoA signaling within ASM.66 PLC has been implicated in regulation of BDNF release in ASM65 showing that activation of PLC is necessary for release and regulation of BDFN within ASM, leading to further activation of Ca2+-dependent pathways65 and the potential for development of contractility and AHR.

Experimentally, application of NTs including BDNF and neurotrophin 4 (NT4) enhances Ca2+ response in HASM following exposure to ACh, histamine, and brandykinin in a dose-dependent manner.61, 62 Exposure to the proinflamatory cytokine TNF-α, which is often upregulated in asthmatic tissue, further modulated Ca2+ response to BDNF following exposure to ACh or histamine.61 Interestingly, ASM has been shown to secrete BDNF through transient receptor potential channels (TRPC), which assist in regulating [Ca2+]i, with higher BDNF secretion in asthmatic ASM, as well as with increased BDNF secretion following prolonged treatment with TNF-α.65

Additionally, exposure of ASM to BDNF significantly increased the force response generated after exposure to histamine or ACh.62 Following Ca2+ store depletion, enhanced SOCE was also seen in ASM acutely exposed to 1 nM or 10 nM BDNF, as well as ASM exposed to 1 nm BDNF or NT4, indicating that NTs can induce Ca2+ entry.62 Increased [Ca2+]i release from the SR or Ca2+ influx following exposure to BDNF, as well as increased expression of TrkB in human asthmatic bronchial samples,60 suggests a potential for increased contractility in HASM from NANC nerve-mediated pathways. Additionally, though not well studied in humans, inhibitory NANC pathways may mediate bronchodilation in ASM to attenuate bronchoconstriction and AHR.56

Taken together, these three mechanisms by which ASM contract have been shown to be altered in some way in asthma-derived ASM. These findings suggest that AHR induced in asthma is likely due to a combination of these mechanisms rather than amplification of one process alone.

Asthma-derived ASM displays attenuated responses to agonist-induced relaxation

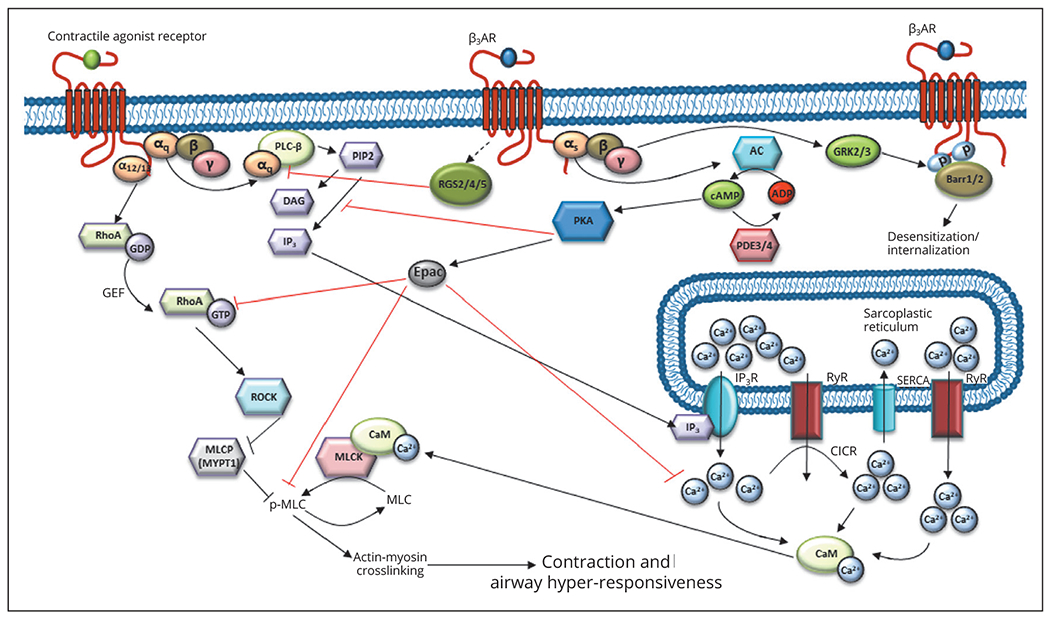

With alterations in contractile signaling, there exist alterations in relaxation signaling that can be precipitated by the inflammatory environment present in asthma. Figure 3 illustrates signaling downstream of the β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR), with the following section addressing phenotypic and genotypic changes to ASM that alter β2AR function and downstream signaling.

Figure 3.—

β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR)-mediated inhibition of contractile signaling, signaling pathways modulating relaxation, and mechanisms of β2AR downregulation. RGS2/4/5, regulator of g protein signaling 2/4/5; βarr, β arrestin 1/2; PDE3/4, phosphodiesterase 3/4; GRK2/3, G protein receptor kinase 2/3; Epac, exchange factor directly activated by cAMP; PKA, protein kinase A; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; AC, adenylyl cyclase.

Altered mechanisms of ASM relaxation in asthma

Downregulation of contractile pathways

Relaxation of ASM can modulate contractile pathways through activation of kinases and ion channels to reverse the effects of depolarization of the membrane following contractile GPCR activation. The most commonly targeted pathway to induce bronchodilation, that is also the target of current bronchodilator therapies used to treat asthma, is the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR). The β2AR belongs to a GPCR family that has been found to Gαs-coupled in order to promote dilation in ASM cells. Activation of Gαs by the β2AR then activates adenylate cyclase, which converts ATP to cAMP. Generation of cAMP induces activation of protein kinase A (PKA).44 Activation of these mechanisms can inhibit increases in [Ca2+]i elicited by contractile agonist receptor activation or reduce calcium sensitivity of the cell,67 through impairment of myosin light chain phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of HSP20 has been identified to inhibit contraction of ASM.68, 69 Additionally, generation of cGMP following nitric oxide stimulation of protein kinase G (PKG) can also induce ASM relaxation. It has been shown that cAMP, through PKG, is able to directly inhibit SOCE.70 Epac, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor, is an effector molecule downstream of cAMP. A cAMP analog that is targets activation of Epac was demonstrated to decrease contraction of ASM, MLC phosphorylation, and RhoA activities that are activated upon acetylcholine stimulation.71 This shows that cAMP, through Epac, is able to modulate both calcium-dependent and -independent sensitization pathways to induce relaxation of ASM. Activation of a PKC-dependent kinase, 17-kD myosin phosphatase inhibitor protein (CPI-17), has been shown to increase calcium sensitivity in ASM, illustrating another effect on calcium-dependent signaling that induces contraction, and subsequent knockdown of CPI-17 inhibited contraction of ASM.72, 73 Additionally, PKA has been shown to regulate membrane-proximal events including Gαq and PLC activation through phosphorylation to inhibit contractile agonist-induced [Ca2+]i mobilization and hydrolysis of phosphoinositides.67 To reverse the effects of [Ca2+]i flux induced by contractile agonists, it has been shown that cAMP, agonists of the β2AR, and PKA can all regulate gating of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels in ASM.74 Additionally, components of the calcium-dependent signaling like SERCA2 have been shown to be downregulated in asthma-derived ASM14 and with chronic stimulation with β2 agonists.67 Relaxation of ASM is dependent on myosin light-chain phosphatase, which dephosphorylates MLC20 when [Ca2+]i is low (1, 6). Thus, dysregulation of [Ca2+]i within the cytosol of asthmatic patients can lead to a buildup of [Ca2+]i and increased contraction of ASM through activation of MLCK. A large component of this dysregulation of Ca2+ homeostasis may be SERCA that, when lowly expressed in asthma-derived ASM, can lead to buildup of [Ca2+]i (8) and contraction of ASM through MLCK activity. Additionally, SERCA expression has been shown to be downregulated by ASM exposure to IL-13 and TNFα.26

Upregulation of regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins by β2 agonists has also been shown to attenuate agonist-induced contraction of ASM. It was demonstrated that both β2 agonist and glucocorticoid treatment of ASM increased RGS2 expression, that reduced [Ca2+]i flux elicited by histamine, methacholine, and leukotrienes.75 RGS2 is known to target Gαq-dependent signaling, a G protein that is known to be associated with multiple contractile GP-CRs. Additionally, RGS4 expression was found to be elevated in asthma-derived ASM and that overexpression of RGS4 was shown to attenuate muscarinic receptor-induced constriction.76 Prolonged exposure to β2 agonists has been shown to attenuate expression of RGS5 and siRNA-mediated knockdown of RGS5 reduced myosin light chain phosphorylation and [Ca2+]i flux.77 Levels of RGS5 are elevated in asthma-derived ASM.15 Reversal of actin polymerization is also affected by activation of β2AR signaling. It was demonstrated that activation of cAMP-PKA signaling inhibits modulation of the actin cytoskeleton. PKA induced HSP20 phosphorylation, thereby decreasing cofilin phosphorylation and disrupting actin polymerization resulting in ASM relaxation.69, 78

Regulation of β2AR signaling

To prevent aberrant/chronic signaling through the β2AR, there are mechanisms by which down-regulation of function/receptor number occurs. Desensitization of the β2AR has also been identified both clinically and experimentally. This downregulation of the receptor and functions has been problematic with respect to the widespread utilization of β2 agonists in the treatment of asthma,19, 20, 79–84 as prolonged use of these therapeutics results in downregulation of the receptor and attenuation of agonist-induced bronchodilation. Polymorphisms of the β2AR have been shown to downregulate the function of the receptor via targeting the receptor for degradation, by decreasing affinity of the receptor for β2 agonists, or through uncoupling of the receptor to adenylyl cyclase (as reviewed in85), with some evidence that the specific polymorphisms Arg16Gly and Gln27Glu having been associated with asthma severity and response to β2 agonist therapy.86 Natural antagonism of cAMP production occurs via a family of enzymes called phosphodiesterases (PDEs). The PDE3 inhibitor SKF94120 significantly inhibits contraction of human bronchi.87 Interestingly, multiple groups have found that PDE4D enzymes, including PDE4D5, are increased in expression in ASM derived from asthma subjects, as well as in TGF-β1-stimulated non-asthma ASM.88–92 When β2AR is stimulated, activation of the Gαβγ complex induces signaling downstream of the Gαs and Gβγ subunits. The Gβγ subunits can recruit βarrestins to the β2AR through activation of G protein receptor kinases (GRKs), which then lead to internalization of the receptor. It has been demonstrated that ASM express GRKs 2 and 3, as well as βarrestin 1 and 2, but predominantly βarrestin 1.93–95 Interestingly, inverse agonism of the β2AR was found to be important for the therapeutic actions of β blockers. A study showed that the β blocker nadalol increased PC20 and decreased FEV1 values over the study period, helping to partially reverse the AHR associated with asthma.96 In a letter to the editor, it was suggested that a biased ligand that inhibits β2 downregulation, leading to increased AHR, would be useful to antagonize the increased bronchoconstriction associated with asthma.97 The idea of biased agonism or antagonism has been postulated to “dial out” the unwanted effects of β2 agonists to provide more effective therapies for asthma.98 Additionally, β2 agonist stimulation of ASM has been shown to downregulate β2AR expression through up-regulation of let-7f miRNA.99 Asthma-derived ASM stimulation with a β2 agonist showed that this mechanism of downregulation of the β2AR is relevant in a disease model, suggesting that modulation of let-7f miRNA may be a valid target for therapeutic intervention in the case of β2 agonist-insensitivity.100

Cytokine-mediated alterations in β2AR signaling may also contribute to the hyporesponsiveness to bronchodilators. IL-13 treatment has been shown to decrease β2 agonist-induced cAMP production as well as attenuate β2 agonist-induced relaxation of human small airways16, 19, 20, 101 and cAMP production in ASM.21, 102 It was also demonstrated that following ASM stimulation with TGF-β1, β2 agonist-induced cAMP production and relaxation was attenuated via a PDE4-dependent mechanism.91 IL1-β, a factor associated with viral infections that can exacerbate underlying asthma, was shown to attenuate β2 agonist-induced cAMP production in ASM.21

Interestingly, activation of protein kinase G (PKG) can be achieved through stimulation of the β2AR, but it also occurs through activation of an enzyme similar to adenylate cyclase called guanylate cyclase (GC). Investigators have noted that direct activation of GC with nitric oxide (NO) donors including NOC18, sodium nitroprusside, BAY 41-2272, and BAY 60-2770 induced dilation of human small airways.103, 104 Even in the face of β2AR desensitization, the GC activators BAY 41 and BAY 60 were able to induce dilation of human small airways. Overnight treatment with the NO donor NOC18 augmented GC-dependent bronchodilation.104

With agonism of the β2AR being a main component of current asthma therapy, a greater understanding of mechanisms by which receptor stimulation dampens contractile signaling and how the inflammatory environment that is characteristic of asthma contributes to dysfunction of the receptor is key to future development of novel therapeutics to enhance signaling through the β2AR and associated pathways.

Acknowledgements.—

The authors acknowledge William Jester and Brian Deeney for their assistance with editing figures for the manuscript.

Funding.—

Reynold A. Panettieri: NIH funding - P01 HL114471; Cynthia J. Koziol-White: NIH funding – R56 HL142890.

Conflicts of interest.—

Eric B. Gebski: no conflicts of interest; Omar Anaspure: no conflicts of interest; Reynold A. Panettieri: Research Grant P01 HL114471 (related to the manuscript), AstraZeneca (not directly related to manuscript), RIFM grant (not directly related to manuscript); consultant for AstraZeneca, RIFM, Equillium (not directly related to manuscript); Honoraria for speaking (though not directly related to this manuscript): AstraZeneca, Sanofi/Regeneron, Genentech; Cynthia J. Koziol-White: Research Grant: R56 HL142890 (not related to the manuscript).

References

- 1.An SS, Bai TR, Bates JH, Black JL, Brown RH, Brusasco V, et al. Airway smooth muscle dynamics: a common pathway of airway obstruction in asthma. Eur Respir J 2007:29:834–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An SS, Kim J, Ahn K, Trepat X, Drake KJ, Kumar S, et al. Cell stiffness, contractile stress and the role of extracellular matrix. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;382:697–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An SS, Mitzner W, Tang WY, Ahn K, Yoon AR, Huang J, et al. An inflammation-independent contraction mechanophenotype of airway smooth muscle in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;138:294–297.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amrani Y, Krymskaya V, Maki C, Panettieri RA Jr. Mechanisms underlying TNF-alpha effects on agonist-mediated calcium homeostasis in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 1997;273:L1020–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croisier H, Tan X, Chen J, Sneyd J, Sanderson MJ, Brook BS. Ryanodine receptor sensitization results in abnormal calcium signaling in airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2015;53:703–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croisier H, Tan X, Perez-Zoghbi JF, Sanderson MJ, Sneyd J, Brook BS. Activation of store-operated calcium entry in airway smooth muscle cells: insight from a mathematical model. PLoS One 2013;8:e69598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon RE, Santana LF. A Ca2+- and PKC-driven regulatory network in airway smooth muscle. J Gen Physiol 2013;141:161–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang IY, Bai Y, Sanderson MJ, Sneyd J. A mathematical analysis of agonist- and KCl-induced Ca(2+) oscillations in mouse airway smooth muscle cells. Biophys J 2010;98:1170–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright DB, Tripathi S, Sikarwar A, Santosh KT, Perez-Zoghbi J, Ojo OO, et al. Regulation of GPCR-mediated smooth muscle contraction: implications for asthma and pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2013;26:121–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopra LC, Twort CH, Cameron IR, Ward JP, Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate- and guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate)-induced Ca2+ release in cultured airway smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol 1991;104:901–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koopmans T, Anaparti V, Castro-Piedras I, Yarova P, Irechukwu N, Nelson C, et al. Ca2+ handling and sensitivity in airway smooth muscle: emerging concepts for mechanistic understanding and therapeutic targeting. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2014;29:108–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marmy N, Durand-Arczynska W, Durand J. Agonist-induced production of inositol phosphates in human airway smooth muscle cells in culture. J Physiol Paris 1992;86:185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto H, Hirata Y, Otsuka K, Iwata T, Inazumi A, Niimi A, et al. Interleukin-13 enhanced Ca2+ oscillations in airway smooth muscle cells. Cytokine 2012;57:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahn K, Hirst SJ, Ying S, Holt MR, Lavender P, Ojo OO, et al. Diminished sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) expression contributes to airway remodelling in bronchial asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:10775–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Z, Balenga N, Cooper PR, Damera G, Edwards R, Brightling CE, et al. Regulator of G-protein signaling-5 inhibits bronchial smooth muscle contraction in severe asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2012;46:823–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper PR, Lamb R, Day ND, Branigan PJ, Kajekar R, San Mateo L, et al. TLR3 activation stimulates cytokine secretion without altering agonist-induced human small airway contraction or relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009;297:L530–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du Y, Zhao J, Li X, Jin S, Ma WL, Mu Q, et al. Dissociation of FK506-binding protein 12.6 kD from ryanodine receptor in bronchial smooth muscle cells in airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014;50:398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, et al. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science 1998;282:2258–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koziol-White CJ, Yoo EJ, Cao G, Zhang J, Papanikolaou E, Pushkarsky I, et al. Inhibition of PI3K promotes dilation of human small airways in a rho kinase-dependent manner. Br J Pharmacol 2016; 173:2726–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinett KS, Koziol-White CJ, Akoluk A, An SS, Panettieri RA Jr, Liggett SB, Bitter taste receptor function in asthmatic and nonasthmatic human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014;50:678–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tliba O, Deshpande D, Chen H, Van Besien C, Kannan M, Panettieri RA Jr, et al. IL-13 enhances agonist-evoked calcium signals and contractile responses in airway smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol 2003;140:1159–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deshpande DA, Walseth TF, Panettieri RA, Kannan MS. CD38/cyclic ADP-ribose-mediated Ca2+ signaling contributes to airway smooth muscle hyper-responsiveness. FASEB J 2003;17:452–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jude JA, Tirumurugaan KG, Kang BN, Panettieri RA, Walseth TF, Kannan MS. Regulation of CD38 expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: role of class I phosphatidylinositol 3 kinases. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2012;47:427–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sieck GC, White TA, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Wylam ME, Prakash YS. Regulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry by CD38 in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;294:L378–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deshpande DA, Dogan S, Walseth TF, Miller SM, Amrani Y, Panettieri RA, et al. Modulation of calcium signaling by interleukin-13 in human airway smooth muscle: role of CD38/cyclic adenosine diphosphate ribose pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sathish V, Thompson MA, Bailey JP, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS, Sieck GC. Effect of proinflammatory cytokines on regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ reuptake in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009;297:L26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prakash YS, Kannan MS, Walseth TF, Sieck GC. Role of cyclic ADP-ribose in the regulation of [Ca2+]i in porcine tracheal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol 1998;274:C1653–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jude JA, Solway J, Panettieri RA Jr, Walseth TF, Kannan MS. Differential induction of CD38 expression by TNF-alpha in asthmatic airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2010;299:L879–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Middleton E Jr. Airway smooth muscle, asthma, and calcium ions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1984;73:643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Middleton E Jr. Calcium antagonists and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1985;76:341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ojiaku CA, Cao G, Zhu W, Yoo EJ, Shumyatcher M, Himes BE, et al. TGF-β1 Evokes Human Airway Smooth Muscle Cell Shortening and Hyperresponsiveness via Smad3. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2018;58:575–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ammit AJ, Armour CL, Black JL. Smooth-muscle myosin light-chain kinase content is increased in human sensitized airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:257–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiba Y, Matsusue K, Misawa M. RhoA, a possible target for treatment of airway hyperresponsiveness in bronchial asthma. J Pharmacol Sci 2010;114:239–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo L, Wang L, Paré PD, Seow CY, Chitano P. The Huxley crossbridge model as the basic mechanism for airway smooth muscle contraction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2019;317:L235–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Álvarez-Santos MD, Álvarez-González M, Estrada-Soto S, Bazán-Perkins B. Regulation of Myosin Light-Chain Phosphatase Activity to Generate Airway Smooth Muscle Hypercontractility. Front Physiol 2020;11:701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Léguillette R, Laviolette M, Bergeron C, Zitouni N, Kogut P, Solway J, et al. Myosin, transgelin, and myosin light chain kinase: expression and function in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao YD, Zou JJ, Zheng JW, Shang M, Chen X, Geng S, et al. Promoting effects of IL-13 on Ca2+ release and store-operated Ca2+ entry in airway smooth muscle cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2010;23:182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soboloff J, Rothberg BS, Madesh M, Gill DL. STIM proteins: dynamic calcium signal transducers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012;13:549–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Deng X, Gill DL. Calcium signaling by STIM and Orai: intimate coupling details revealed. Sci Signal 2010;3:pe42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP, A key role for STIM1 in store operated calcium channel activation in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res 2006;7:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia L, Delmotte P, Aravamudan B, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS, Sieck GC. Effects of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-13 on stromal interaction molecule-1 aggregation in human airway smooth muscle intracellular Ca(2+) regulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013;49:601–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao YD, Zheng JW, Li P, Cheng M, Yang J. Store-operated Ca2+ entry is involved in transforming growth factor-β1 facilitated proliferation of rat airway smooth muscle cells. J Asthma 2013;50:439–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunter I, Cobban HJ, Vandenabeele P, MacEwan DJ, Nixon GF. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced activation of RhoA in airway smooth muscle cells: role in the Ca2+ sensitization of myosin light chain20 phosphorylation. Mol Pharmacol 2003;63:714–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koziol-White CJ, Panettieri RA Jr. Modulation of Bronchomotor Tone Pathways in Airway Smooth Muscle Function and Bronchomotor Tone in Asthma. Clin Chest Med 2019;40:51–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaifta Y, MacKay CE, Irechukwu N, O’Brien KA, Wright DB, Ward JP, et al. Transforming growth factor-β enhances Rho-kinase activity and contraction in airway smooth muscle via the nucleotide exchange factor ARHGEF1. J Physiol 2018;596:47–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev 2003;83:1325–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoo EJ, Cao G, Koziol-White CJ, Ojiaku CA, Sunder K, Jude JA, et al. Gα12 facilitates shortening in human airway smooth muscle by modulating phosphoinositide 3-kinase-mediated activation in a RhoA-dependent manner. Br J Pharmacol 2017;174:4383–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dogan M, Han YS, Delmotte P, Sieck GC. TNFα enhances force generation in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2017;312:L994–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang DD. Critical role of actin-associated proteins in smooth muscle contraction, cell proliferation, airway hyperresponsiveness and airway remodeling. Respir Res 2015;16:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang T, Cleary RA, Wang R, Tang DD. Role of the adapter protein Abi1 in actin-associated signaling and smooth muscle contraction. J Biol Chem 2013;288:20713–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cleary RA, Wang R, Wang T, Tang DD. Role of Abl in airway hyperresponsiveness and airway remodeling. Respir Res 2013;14:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang R, Cleary RA, Wang T, Li J, Tang DD. The association of cortactin with profilin-1 is critical for smooth muscle contraction. J Biol Chem 2014;289:14157–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerlach BD, Tubbesing K, Liao G, Rezey AC, Wang R, Barroso M, et al. Phosphorylation of GMFγ by c-Abl Coordinates Lamellipodial and Focal Adhesion Dynamics to Regulate Airway Smooth Muscle Cell Migration. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2019;61:219–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang DD, Gerlach BD. The roles and regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, intermediate filaments and microtubules in smooth muscle cell migration. Respir Res 2017;18:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang T, Cleary RA, Wang R, Tang DD. Glia maturation factor-γ phosphorylation at Tyr-104 regulates actin dynamics and contraction in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014;51:652–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kistemaker LE, Prakash YS. Airway Innervation and Plasticity in Asthma. Physiology (Bethesda) 2019;34:283–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takahashi T, Belvisi MG, Patel H, Ward JK, Tadjkarimi S, Yacoub MH, et al. Effect of Ba 679 BR, a novel long-acting anticholinergic agent, on cholinergic neurotransmission in guinea pig and human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;150:1640–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schlepütz M, Rieg AD, Seehase S, Spillner J, Perez-Bouza A, Braunschweig T, et al. Neurally mediated airway constriction in human and other species: a comparative study using precision-cut lung slices (PCLS). PLoS One 2012;7:e47344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dupont LJ, Pype JL, Demedts MG, De Leyn P, Deneffe G, Verleden GM. The effects of 5-HT on cholinergic contraction in human airways in vitro. Eur Respir J 1999;14:642–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dragunas G, Woest ME, Nijboer S, Bos ST, van Asselt J, de Groot AP, et al. Cholinergic neuroplasticity in asthma driven by TrkB signaling. FASEB J 2020;34:7703–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prakash YS, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in TNF-alpha modulation of Ca2+ in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;41:603–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prakash YS, Iyanoye A, Ay B, Mantilla CB, Pabelick CM. Neurotrophin effects on intracellular Ca2+ and force in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291: L447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bonini S, Lambiase A, Bonini S, Angelucci F, Magrini L, Manni L, et al. Circulating nerve growth factor levels are increased in humans with allergic diseases and asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:10955–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Renz H Neurotrophins in bronchial asthma. Respir Res 2001;2:265–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aravamudan B, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Mechanisms of BDNF regulation in asthmatic airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2016;311:L270–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Britt RD Jr, Thompson MA, Wicher SA, Manlove LJ, Roesler A, Fang YH, et al. Smooth muscle brain-derived neurotrophic factor contributes to airway hyperreactivity in a mouse model of allergic asthma. FASEB J 2019;33:3024–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Billington CK, Ojo OO, Penn RB, Ito S. cAMP regulation of airway smooth muscle function. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2013;26:112–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ba M, Singer CA, Tyagi M, Brophy C, Baker JE, Cremo C, et al. HSP20 phosphorylation and airway smooth muscle relaxation. Cell Health Cytoskelet 2009;2009:27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Komalavilas P, Penn RB, Flynn CR, Thresher J, Lopes LB, Furnish EJ, et al. The small heat shock-related protein, HSP20. is a cAMP-dependent protein kinase substrate that is involved in airway smooth muscle relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;294:L69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ay B, Iyanoye A, Sieck GC, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM. Cyclic nucleotide regulation of store-operated Ca2+ influx in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;290:L278–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roscioni SS, Maarsingh H, Elzinga CR, Schuur J, Menzen M, Halayko AJ, et al. Epac as a novel effector of airway smooth muscle relaxation. J Cell Mol Med 2011;15:1551–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eto M, Senba S, Morita F, Yazawa M. Molecular cloning of a novel phosphorylation-dependent inhibitory protein of protein phosphatase-1 (CPI17) in smooth muscle: its specific localization in smooth muscle. FEBS Lett 1997;410:356–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morin C, Sirois M, Echave V, Rousseau E. CPI-17 silencing-reduced responsiveness in control and TNF-alpha-treated human bronchi. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;39:638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kume H, Hall IP, Washabau RJ, Takagi K, Kotlikoff MI. Beta-adrenergic agonists regulate KCa channels in airway smooth muscle by cAMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Clin Invest 1994;93:371–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Holden NS, Bell MJ, Rider CF, King EM, Gaunt DD, Leigh R, et al. β2-Adrenoceptor agonist-induced RGS2 expression is a genomic mechanism of bronchoprotection that is enhanced by glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:19713–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Madigan LA, Wong GS, Gordon EM, Chen WS, Balenga N, Koziol-White CJ, et al. RGS4 Overexpression in Lung Attenuates Airway Hyperresponsiveness in Mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2018;58:89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang Z, Cooper PR, Damera G, Mukhopadhyay I, Cho H, Kehrl JH, et al. Beta-agonist-associated reduction in RGS5 expression promotes airway smooth muscle hyper-responsiveness. J Biol Chem 2011;286:11444–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hirshman CA, Zhu D, Panettieri RA, Emala CW. Actin depolymerization via the beta-adrenoceptor in airway smooth muscle cells: a novel PKA-independent pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001;281:C1468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cazzola M, Page CP, Calzetta L, Matera MG. Pharmacology and therapeutics of bronchodilators. Pharmacol Rev 2012;64:450–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cooper PR, Panettieri RA Jr. Steroids completely reverse albuterol-induced beta(2)-adrenergic receptor tolerance in human small airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:734–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haney S, Hancox RJ. Tolerance to bronchodilation during treatment with long-acting beta-agonists, a randomised controlled trial. Respir Res 2005;6:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Newnham DM, Grove A, McDevitt DG, Lipworth BJ. Subsensitivity of bronchodilator and systemic beta 2 adrenoceptor responses after regular twice daily treatment with eformoterol dry powder in asthmatic patients. Thorax 1995;50:497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wraight JM, Hancox RJ, Herbison GP, Cowan JO, Flannery EM, Taylor DR. Bronchodilator tolerance: the impact of increasing bronchoconstriction. Eur Respir J 2003;21:810–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yim RP, Koumbourlis AC. Tolerance & resistance to β2-agonist bronchodilators. Paediatr Respir Rev 2013;14:195–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liggett SB. Molecular and genetic basis of beta2-adrenergic receptor function. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;104:S42–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mohamed-Hussein AA, Sayed SS, Eldien HM, Assar AM, Yehia FE. Beta 2 Adrenergic Receptor Genetic Polymorphisms in Bronchial Asthma: Relationship to Disease Risk Severity, and Treatment Response. Lung 2018;196:673–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rabe KF, Tenor H, Dent G, Schudt C, Liebig S, Magnussen H. Phosphodiesterase isozymes modulating inherent tone in human airways: identification and characterization. Am J Physiol 1993;264:L458–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Billington CK, Le Jeune IR, Young KW, Hall IP. A major functional role for phosphodiesterase 4D5 in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;38:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chung E, Ojiaku CA, Cao G, Parikh V, Deeney B, Xu S, et al. Dexamethasone rescues TGF-β1-mediated β2-adrenergic receptor dysfunction and attenuates phosphodiesterase 4D expression in human airway smooth muscle cells. Respir Res 2020;21:256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Niimi K, Ge Q, Moir LM, Ammit AJ, Trian T, Burgess JK, et al. β2-Agonists upregulate PDE4 mRNA but not protein or activity in human airway smooth muscle cells from asthmatic and nonasthmatic volunteers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2012;302:L334–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ojiaku CA, Chung E, Parikh V, Williams JK, Schwab A, Fuentes AL, et al. Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Decreases β2-Agonist-induced Relaxation in Human Airway Smooth Muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2019;61:209–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Trian T, Burgess JK, Niimi K, Moir LM, Ge Q, Berger P, et al. β2-Agonist induced cAMP is decreased in asthmatic airway smooth muscle due to increased PDE4D. PLoS One 2011;6:e20000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Deshpande DA, Theriot BS, Penn RB, Walker JK. Beta-arrestins specifically constrain beta2-adrenergic receptor signaling and function in airway smooth muscle. FASEB J 2008;22:2134–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Deshpande DA, Yan H, Kong KC, Tiegs BC, Morgan SJ, Pera T, et al. Exploiting functional domains of GRK2/3 to alter the competitive balance of pro- and anticontractile signaling in airway smooth muscle. FASEB J 2014;28:956–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kong KC, Gandhi U, Martin TJ, Anz CB, Yan H, Misior AM, et al. Endogenous Gs-coupled receptors in smooth muscle exhibit differential susceptibility to GRK2/3-mediated desensitization. Biochemistry 2008;47:9279–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hanania NA, Singh S, El-Wali R, Flashner M, Franklin AE, Garner WJ, et al. The safety and effects of the beta-blocker, nadolol, in mild asthma: an open-label pilot study. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2008;21:134–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Penn RB. Far from “disappointing”. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Panettieri RA, Pera T, Liggett SB, Benovic JL, Penn RB. Pepducins as a potential treatment strategy for asthma and COPD. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2018;40:120–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang WC, Juan AH, Panebra A, Liggett SB. MicroRNA let-7 establishes expression of beta2-adrenergic receptors and dynamically down-regulates agonist-promoted down-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108:6246–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim D, Cho S, Woo JA, Liggett SB. A CREB-mediated increase in miRNA let-7f during prolonged β-agonist exposure: a novel mechanism of β2-adrenerjic receptor down-regulation in airway smooth muscle. FASEB J 2018;32:3680–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Laporte JC, Moore PE, Baraldo S, Jouvin MH, Church TL, Schwartzman IN, et al. Direct effects of interleukin-13 on signaling pathways for physiological responses in cultured human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Amrani Y, Panettieri RA Jr, Modulation of calcium homeostasis as a mechanism for altering smooth muscle responsiveness in asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;2:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ghosh A, Koziol-White CJ, Asosingh K, Cheng G, Ruple L, Groneberg D, et al. Soluble guanylate cyclase as an alternative target for bronchodilator therapy in asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:E2355–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Koziol-White CJ, Ghosh A, Sandner P, Erzurum SE, Stuehr DJ, Panettieri RA Jr. Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Agonists Induce Bronchodilation in Human Small Airways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2020;62:43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]