Abstract

BACKGROUND

Left-sided portal hypertension (LSPH), also known as sinistral portal hypertension or regional portal hypertension, refers to extrahepatic portal hypertension caused by splenic vein obstruction or stenosis. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBC) has been widely used in the endoscopic hemostasis of portal hypertension, but adverse events including renal or pulmonary thromboembolism, mucosal necrosis and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding may occur after treatment. Herein, we report successfully managing gastric variceal (GV) hemorrhage secondary to LSPH using modified endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided selective NBC injections.

CASE SUMMARY

A 35-year-old man was referred to our hospital due to an upper GI hemorrhage. Gastroscopy revealed GV hemorrhage and computed tomography venography (CTV) confirmed LSPH. The patient requested endoscopic procedures and rejected surgical therapies including splenectomy. EUS-guided selective NBC injections were performed and confluences of gastric varices were selected as the injection sites to reduce the injection dose. The “sandwich” method using undiluted NBC and hypertonic glucose was applied. No complications occurred. The patient was followed up regularly after discharge. Three months later, the follow-up gastroscopy revealed firm gastric submucosa with no sign of NBC expulsion and the follow-up CTV showed improvements in LSPH. No recurrent GI hemorrhage was reported during this follow-up period.

CONCLUSION

EUS-guided selective NBC injection may represent an effective and economical treatment for GV hemorrhage in patients with LSPH.

Keywords: Left-sided portal hypertension, Endoscopic ultrasound, Selective, N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, Gastric varices, Case report

Core Tip: Gastric variceal (GV) hemorrhage caused by left-sided portal hypertension (LSPH) is a severe complication. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided procedures for GV hemorrhage demonstrated beneficial results in reducing complication risks. Herein, we report the successful management of GV hemorrhage secondary to LSPH using EUS-guided selective N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection which proved the effectiveness and safety of this method. This case is the first report choosing confluences of gastric varices as injection sites to reduce the injection dose and postoperative complications in patients with LSPH.

INTRODUCTION

Left-sided portal hypertension (LSPH), also known as sinistral portal hypertension or regional portal hypertension, refers to extrahepatic portal hypertension caused by splenic vein obstruction or stenosis[1-3]. LSPH accounts for about 5% of extrahepatic portal hypertension and is characterized by isolated gastric varices (GVs) and normal liver functions[3]. Pancreatic diseases are the major causes of LSPH. Most patients with LSPH have no obvious clinical symptoms and they are often diagnosed during the endoscopic examination after gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Therefore, LSPH should be considered in patients with pancreatic diseases who develop unexplained GI hemorrhage[1,4].

Gastric variceal (GV) hemorrhage leads to significant mortality in patients with portal hypertension. Although N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBC) has been widely used in the endoscopic hemostasis of portal hypertension, the early expulsion of NBC and the resultant hemorrhage is not uncommon[5]. Compared with conventional endoscopic injection, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided procedures in patients with GV bleeding demonstrated better diagnostic capability and clinical efficacy[6,7].

Herein, we report the successful management of GV hemorrhage secondary to LSPH using modified EUS-guided selective NBC injection.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 35-year-old man was referred to our hospital due to an upper GI hemorrhage.

History of present illness

A few hours before admission, the patient had no apparent reason for one occurrence of sudden vomiting of blood mixed with stomach contents and the amount was estimated to be about 50-100 mL. He denied melena and syncope.

History of past illness

Nine months previously, this patient was admitted to our hospital due to persistent upper abdominal pain. He was diagnosed with severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) and underwent EUS-guided drainage of a pancreatic walled-off necrosis. He also had a 6-year history of hypertension and took enalapril regularly.

Personal and family history

This patient had a 10-year smoking history (a pack per day) and has not quit smoking. He denied alcoholism and taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Physical examination

After admission, physical examination revealed no abnormality except for 130/91 mmHg blood pressure.

Laboratory examinations

No apparent abnormalities were found in the emergency blood analysis.

Imaging examinations

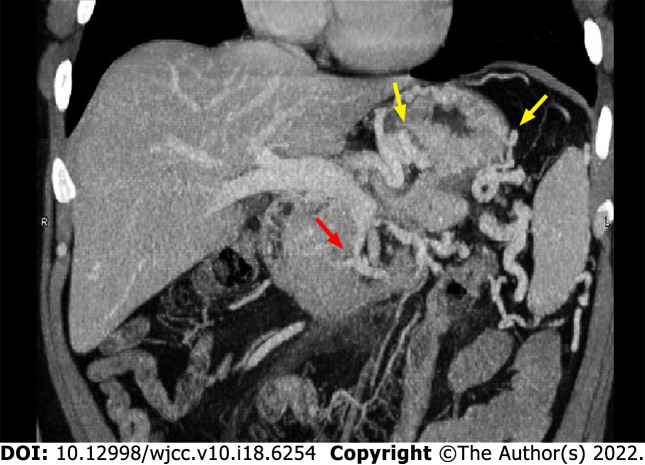

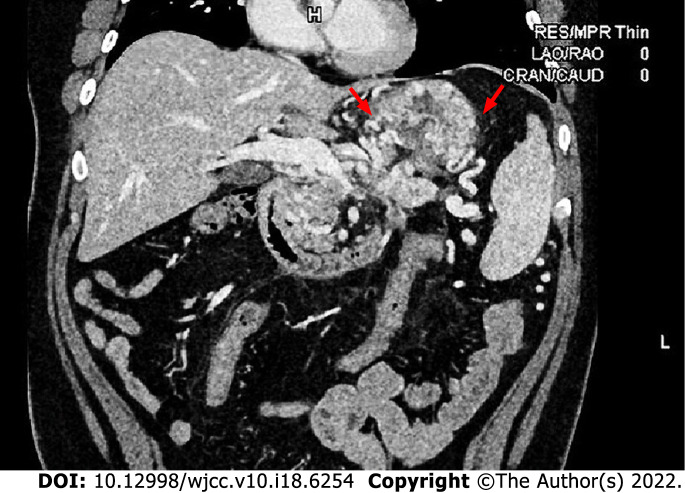

After admission, gastroscopy confirmed GV hemorrhage (IGV1 by Sarin classification), and no esophageal varices or portal hypertensive gastropathy was found (Figure 1). Abdominal computed tomography venography (CTV) revealed stenosis of the proximal superior mesenteric vein, invisible proximal splenic vein and increased collateral circulations (Figure 2). Neither a portal vein thrombosis nor a splenorenal shunt was detected.

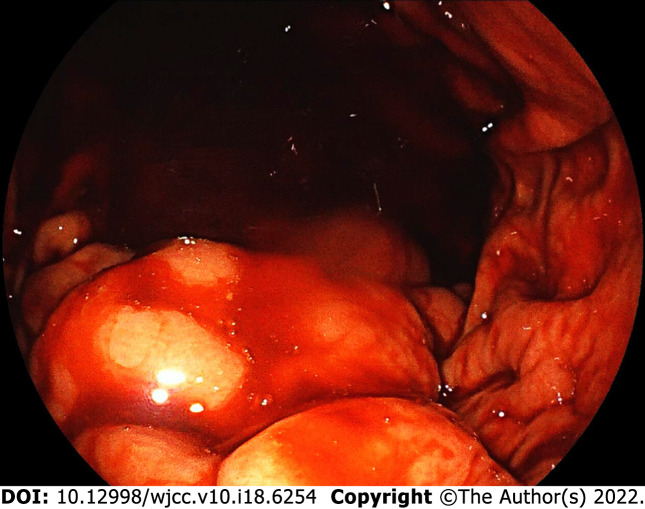

Figure 1.

Gastroscopic image. Gastroscopy revealed gastric variceal with signs of recent bleeding in the absence of active bleeding.

Figure 2.

Abdominal computed tomography venography image. Computed tomography venography revealed stenosis of the proximal superior mesenteric vein (red arrow), invisible proximal splenic vein, and increased collateral circulations (yellow arrows).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

LSPH and GV hemorrhage.

TREATMENT

The patient requested endoscopic procedures and rejected surgical therapies including splenectomy. EUS-guided selective NBC injections were performed for the treatment and prophylaxis of GV hemorrhage.

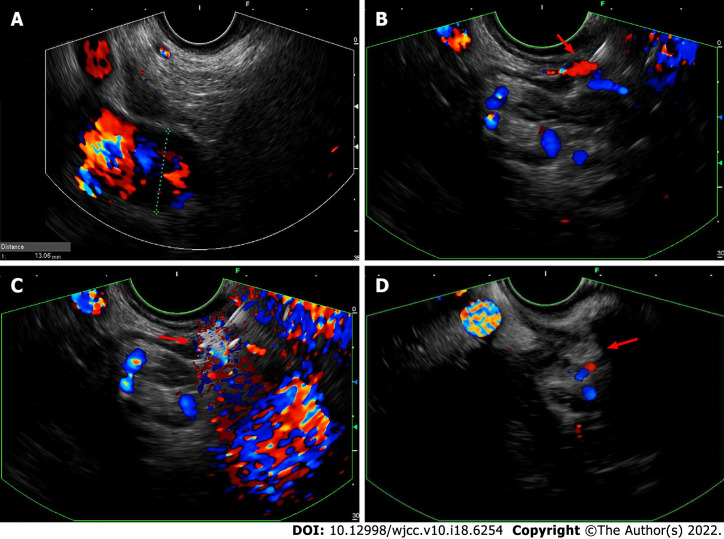

A linear Pentax echoendoscope (Hoya Co., Tokyo, Japan) and the color Doppler flow imaging were employed to determine the puncture site. EUS revealed an enlarged portal vein without cavernous transformation (Figure 3A). The confluences of GVs were selected as the injection sites to reduce the injection dose. A 22-gauge needle (Boston Scientific Co., Natick, MA, United States) was used to perform the puncture into the selected GVs (Figure 3B). The “sandwich” method using undiluted NBC (0.5 mL/ampoule; Beijing Compont Medical Devices Co., Beijing, China) and hypertonic glucose was applied (Figure 3C). A total of 2 mL of NBC was injected into three different confluences of GVs. Hyperechoic fillings and decreased blood flow signals were observed after injections (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Endoscopic ultrasound images. A: Endoscopic ultrasound revealed an enlarged portal vein; B: A confluence of gastric varices was identified and selected as the injection site (red arrow); C: Undiluted N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (red arrow) was injected into the selected gastric varix via a 22-gauge needle; D: Hyperechoic fillings (red arrow) and decreased blood flow signals were observed after injections.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

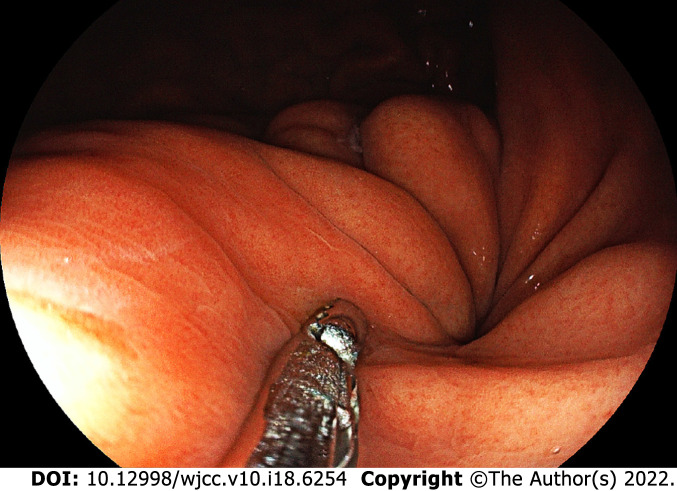

The patient fasted for 1 d after the procedure. No complications, including ectopic embolism, fever and post-injection GI bleeding occurred. The patient was followed up regularly after discharge. Three months later, the follow-up gastroscopy revealed no sign of NBC expulsion (Figure 4) and follow-up CTV showed improvements in LSPH (Figure 5). No recurrent GI hemorrhage and other complications were reported during the 3-mo follow-up.

Figure 4.

Gastroscopic image. With the help of biopsy forceps, the follow-up gastroscopy revealed firm gastric submucosa and no sign of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate expulsion.

Figure 5.

Computed tomography venography image. Compared with the results before the operation (Figure 2), follow-up computed tomography venography revealed improvements in left-sided portal hypertension and collateral circulations (red arrows).

DISCUSSION

Pancreatic diseases such as pancreatitis and pancreatic tumors are the most common etiology of LSPH[3,8]. The anatomical proximity between the splenic vein and the pancreas makes the splenic vein more susceptible to pancreatic diseases. When pancreatic disease obstructs the splenic vein flow, the pressure of the left portal vein system increases and blood flows retrogradely through the short and posterior gastric veins and the gastroepiploic veins, which would lead to GVs. In patients with acute pancreatitis, infected walled-off necrosis was one of the risk factors for LSPH and early anticoagulation could not wholly prevent its occurrence[8]. In this case, the patient had a history of SAP and infected pancreatic necrosis which may be responsible for his LSPH. About 20% of patients with portal hypertension may develop GVs[9], and although LSPH is a rare cause of upper GI hemorrhage, GV hemorrhage in patients with LSPH secondary to pancreatic disease is not uncommon. Liu et al[10] reported that about 15.3% of LSPH patients had complicated bleeding GVs and the death risk is relatively higher when recurrent GV hemorrhage occurs so this is worthy of attention.

It is well known that splenectomy is the most effective treatment for LSPH. However, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, balloon retrograde transvenous obliteration, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) and endoscopic NBC injection were reported effective for patients who are not suitable or unwilling to choose surgery[11]. Although endoscopic NBC injection therapy has been proven minimally invasive and effective[12], conventional endoscopic NBC injections may also cause severe complications including renal or pulmonary thromboembolism, fever, severe pain caused by intraperitoneal injection, mucosal necrosis at the injection site and GI bleeding[13]. As reported in recent years, an EUS-guided hemostasis treatment, including injection of NBC or in combination with coils, injection of thrombin or absorbable gelatin sponge, and clip-assisted endoscopic NBC injection, demonstrated promising results in reducing complication risks[14,15].

Modified EUS-guided selective NBC injection was applied for three distinct advantages in this present case. First, a reduced NBC dose may result in a lower occurrence of post-operational GI bleeding and ectopic embolism. EUS can also provide the detection of submucosal GVs, their confluences and real-time effectiveness evaluation for GV obliteration[7]. These advantages make it possible to identify and select confluences of gastric varices which were in the direction of bleeding gastric vessels and used as injection sites to reduce the injection dose. Although EUS-guided coil injection is reported superior to conventional NBC injection in terms of rebleeding after treatment[16], it was believed that a reduced dose of NBC would be injected into GVs in the modified EUS-guided selective NBC injection, which would lead to lower chances of post-injection ulcer and GI hemorrhage. Besides, reduced NBC dose may result in a similar lower occurrence of ectopic embolism in selective NBC injection as in the coils-combined injection method and clip-assisted injection method. Second, there would be no additional risk of radioactive exposure; coils and metal clips were not used in this modified injection procedure, which decreased the cost of endoscopic procedures. Third, selective NBC injection demonstrated a faster and firmer obliteration effect in GV hemorrhage than thrombin and absorbable gelatin sponge injections, making NBC injection more suitable than other procedures for acute GV bleeding. NBC rarely causes vascular necrosis and was reported superior to EIS in the hemostasis rate for GV bleeding[17]. Thus, EUS-guided selective NBC injection was performed for this patient based on the above factors and the result was adequate. Despite all these advantages, the operation time of EUS-guided selective NBC injection seemed a little longer than that of conventional endoscopic NBC injection due to time consumption to confirm confluences of GVs during the EUS procedure. Additional cases are needed to verify our findings and compare the efficacies and complications of different embolization methods guided by EUS. Currently, this described technique is recommended to be used only in hemodynamically stable patients. To the best of our knowledge, this case is the first report choosing confluences of gastric varices as injection sites to reduce the injection dose and postoperative complications in patients with LSPH.

CONCLUSION

Modified EUS-guided selective NBC injection may represent an effective and economical treatment for GV hemorrhage in patients with LSPH.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Chinese Society of Gastroenterology.

Peer-review started: December 12, 2021

First decision: February 8, 2022

Article in press: April 22, 2022

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Afify S, Egypt; Garbuzenko DV, Russia; Garbuzenko DV, Russia; Martino A, Italy S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia CL P-Editor: Zhang H

Contributor Information

Jian Yang, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China.

Yan Zeng, Department of Psychology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400010, China.

Jun-Wen Zhang, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China. 959308413@qq.com.

References

- 1.Zheng K, Guo X, Feng J, Bai Z, Shao X, Yi F, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Liu H, Romeiro FG, Qi X. Gastrointestinal Bleeding due to Pancreatic Disease-Related Portal Hypertension. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:3825186. doi: 10.1155/2020/3825186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie CL, Wu CQ, Chen Y, Chen TW, Xue HD, Jin ZY, Zhang XM. Sinistral Portal Hypertension in Acute Pancreatitis: A Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Pancreas. 2019;48:187–192. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Köklü S, Coban S, Yüksel O, Arhan M. Left-sided portal hypertension. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1141–1149. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandes A, Almeida N, Ferreira AM, Casela A, Gomes D, Portela F, Camacho E, Sofia C. Left-Sided Portal Hypertension: A Sinister Entity. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2015;22:234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpge.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng LF, Wang ZQ, Li CZ, Cai FC, Huang QY, Linghu EQ, Li W, Chai GJ, Sun GH, Mao YP, Wang YM, Li J, Gao P, Fan TY. Treatment of gastric varices by endoscopic sclerotherapy using butyl cyanoacrylate: 10 years' experience of 635 cases. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120:2081–2085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohan BP, Chandan S, Khan SR, Kassab LL, Trakroo S, Ponnada S, Asokkumar R, Adler DG. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided therapy versus direct endoscopic glue injection therapy for gastric varices: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2020;52:259–267. doi: 10.1055/a-1098-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammoud GM, Ibdah JA. Utility of endoscopic ultrasound in patients with portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14230–14236. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H, Yang Z, Tian F. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Sinistral Portal Hypertension Associated with Moderate and Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Seven-Year Single-Center Retrospective Study. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:5969–5976. doi: 10.12659/MSM.916192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343–1349. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Q, Song Y, Xu X, Jin Z, Duan W, Zhou N. Management of bleeding gastric varices in patients with sinistral portal hypertension. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1625–1629. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3048-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Khazraji A, Curry MP. The current knowledge about the therapeutic use of endoscopic sclerotherapy and endoscopic tissue adhesives in variceal bleeding. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:893–897. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2019.1652092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chevallier O, Guillen K, Comby PO, Mouillot T, Falvo N, Bardou M, Midulla M, Aho-Glélé LS, Loffroy R. Safety, Efficacy, and Outcomes of N-Butyl Cyanoacrylate Glue Injection through the Endoscopic or Radiologic Route for Variceal Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/jcm10112298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim YS. Practical approach to endoscopic management for bleeding gastric varices. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13 Suppl 1:S40–S44. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2012.13.S1.S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang M, Li P, Mou H, Shi Y, Tuo B, Jin S, Sun R, Wang G, Ma J, Zhang C. Clip-assisted endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection for gastric varices with a gastrorenal shunt: a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2019;51:936–940. doi: 10.1055/a-0977-3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhat YM, Weilert F, Fredrick RT, Kane SD, Shah JN, Hamerski CM, Binmoeller KF. EUS-guided treatment of gastric fundal varices with combined injection of coils and cyanoacrylate glue: a large U.S. experience over 6 years (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1164–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bazarbashi AN, Wang TJ, Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC, Ryou M. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Coil Embolization With Absorbable Gelatin Sponge Appears Superior to Traditional Cyanoacrylate Injection for the Treatment of Gastric Varices. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11:e00175. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oho K, Iwao T, Sumino M, Toyonaga A, Tanikawa K. Ethanolamine oleate versus butyl cyanoacrylate for bleeding gastric varices: a nonrandomized study. Endoscopy. 1995;27:349–354. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]