Abstract

The neurovascular unit (NVU) regulates metabolic homeostasis as well as drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the central nervous system. Metabolic fluxes and conversions over the NVU rely on interactions between brain microvascular endothelium, perivascular pericytes, astrocytes and neurons, making it difficult to identify the contributions of each cell type. Here we model the human NVU using microfluidic organ chips, allowing analysis of the roles of individual cell types in NVU functions. Three coupled chips model influx across the blood–brain barrier (BBB), the brain parenchymal compartment and efflux across the BBB. We used this linked system to mimic the effect of intravascular administration of the psychoactive drug methamphetamine and to identify previously unknown metabolic coupling between the BBB and neurons. Thus, the NVU system offers an in vitro approach for probing transport, efficacy, mechanism of action and toxicity of neuroactive drugs.

The multicellular NVU regulates the dynamic influx and efflux of nutrients, metabolites and drugs between the systemic circulation and the central nervous system1, and thereby controls brain homeostasis2. Neuronal function relies on the complex interplay between molecular transport and metabolic activities in all cell populations of the NVU3 (Fig. 1a), and loss of NVU integrity rapidly alters brain function4. Current experimental approaches, including animal models, are limited in their ability to resolve the spatial and temporal dynamics of the NVU and the interactions between neurons, the BBB and the perivasculature5. Moreover, animal studies are hampered by species-specific differences in efflux transporters, tight junctions and cell–cell signaling6. In vitro models of the human BBB and the surrounding perivasculature have been created using both conventional culture methods and microfluidic organ chips7–11, and similar models of brain neuronal networks have been reported10. More recently, human brain pericytes, astrocytes and neurons were integrated in organ chip models of the NVU12. However, the interacting cell types were contained in a single flow device, with at most two inlets and two outlets, preventing dissection of the contributions of the individual cell types or subcompartments to the function of the NVU.

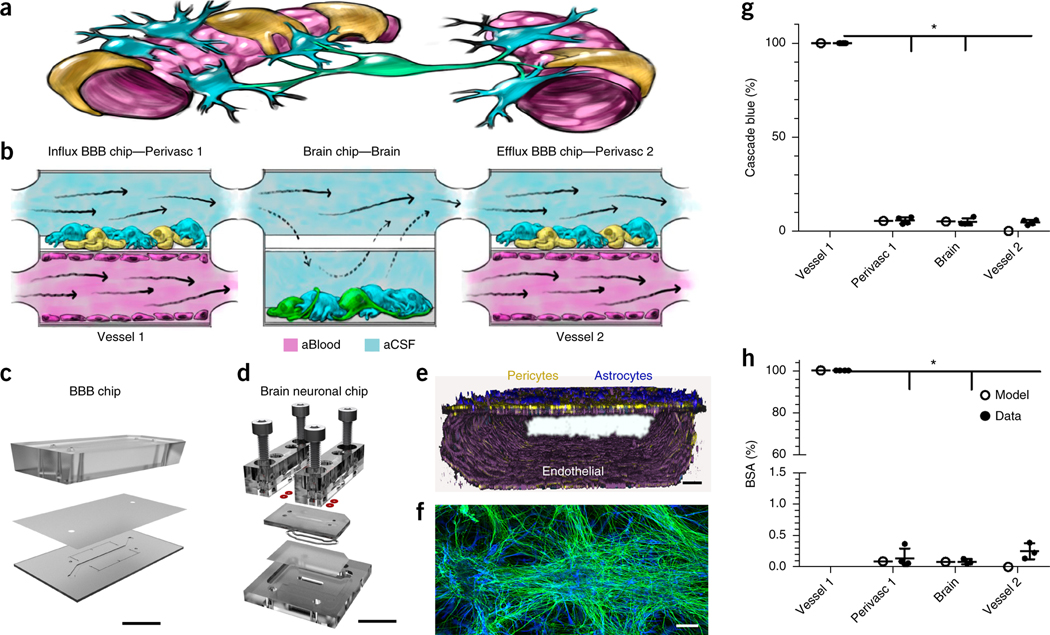

Figure 1.

Decoupling the NVU. (a) Simplified anatomical illustration of the NVU, highlighting positions and cell–cell interactions between vascular endothelial cells (pink) that line brain blood microvessels (left, right) and surrounding perivascular pericytes (yellow) and astrocytes (blue) that form the BBB, as well as neighboring neurons (green) in the brain parenchyma. (b) Schematic of the experimental setup of NVU system. hBMVECs (magenta) are cultured on all four walls of the lower vascular compartment and a mixture of brain astrocytes (blue) and pericytes (yellow) in the top compartment of both BBB chips; human brain neuronal cells (green) and astrocytes (blue) are cultured in the lower compartment of the brain chip. Cell culture medium is flowed into the upper perivascular compartment of BBB chip as an artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF, blue), and cell culture medium mimicking blood is flowed separately through the lower vascular compartment. Components that pass through the BBB perfuse into the perivascular fluid in the upper compartment and are transferred to the upper compartment of the brain chip. They pass by diffusion in and out of the lower neuronal cell compartment, and from there into the upper perivascular compartment of the BBBefflux chip, where some components pass back out into the vascular compartment. CAD illustration of the in vitro human NVU. (c) The BBB chip is composed of optically clear polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) polymer containing two parallel hollow microchannels (compartments, 2 cm long × 1 mm wide); the top and bottom channels (1 and 0.2 mm high, respectively) were separated by a porous (0.4 μm diameter; 4 × 106 pores/cm2) polyethylene terephthalate (PET) membrane coated with fibronectin and collagen IV (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). (d) The brain chip is a polycarbonate microfluidic device containing two parallel channels (compartments, 2.5 cm long × 2.5 mm wide); the top and bottom channels (compartments, 0.2 and 1 mm high, respectively) were separated by a porous (5 µm diameter; 4 × 106 pores/cm2) polycarbonate membrane (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1c,d). (e) Three-dimensional reconstruction of the human BBB chip from confocal fluorescence microscopic images showing the lower compartment covered by a continuous endothelial monolayer stained for VE-Cadherin (purple), and a mixture of pericytes (F-actin, yellow) and astrocytes (GFAP, blue) on the top surface of the porous membrane in the upper channel of the same chip (scale bar, 75 μm). (f) Confocal fluorescence micrograph of the lower compartment of the brain chip showing a mixed culture of neurons (β-III-tubulin, green) and astrocytes (glial fibrillary astrocytic protein, GFAP, blue) (scale bar, 100 µm). Brain chip cultures have been replicated >20 times with similar results. (g,h) Graphs showing mean permeability (%) of fluorescent Cascade blue (530 Da), (*P < 0.0001, (Supplementary Table 1a) (g) and mean Alexa-555-labeled BSA (67 kDa), (*P < 0.0001, Supplementary Table 1a). N = 4 representing independent NVU systems (h) through the BBB measured experimentally on-chip (gray), compared with computational model predictions (black). Error bars are s.e.m., N = 3, except Vessel 1, N = 4 representing independent NVU systems. Significance calculated with one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test (Supplementary Table 1a).

We constructed and connected two BBB chips on each side of a brain chip (Fig. 1a–d and Supplementary Fig. 1). In the BBB chip, primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMVECs) were cultured as a continuous monolayer on the lower surface of the membrane and on all walls of the bottom compartment, while primary brain microvascular pericytes interspersed among astrocytes were cultured on the upper surface of the membrane to mimic the external wall of a brain microvessel (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 2). In the brain chip, a mixed population of primary human neural cells (∼60% glial cells and 40% neurons; glutamatergic, GABAergic, dopaminergic and serotonergic) differentiated from hippocampusderived neural stem cells (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 2) were cultured on the bottom poly-l-lysine-/laminin-coated surface of the lower compartment (Fig. 1b).

In the coupled NVU system, an endothelial medium (artificial blood) was flowed through the endothelium-lined compartment of the first BBB chip (BBBinflux chip) and a neuronal medium (artificial cerebral spinal fluid) through its upper perivascular compartment (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1e). The fluid effluent from the perivascular compartment of the BBBinflux chip was directly transferred to the brain chip’s upper compartment reservoir, with the membrane allowing diffusion of components to and from the lower compartment. The effluent from the upper compartment of the brain chip was then transferred to the inflow of the perivascular compartment of the BBBefflux chip. Effluents of the lower vascular compartments of both BBB chips, as well as effluents of the upper perivascular compartments from all three chips, were collected individually for analysis (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1e). In this manner, the BBBinflux chip modeled influx of compounds from the blood to the brain parenchyma, while the BBBefflux chip modeled efflux from the brain to the blood.

Shear stress on the astrocytes and pericytes (0.0007 dyne/cm2) was >25-fold lower than on the endothelium (0.0007 versus 0.02 dyne/cm2) (Supplementary Fig. 3), with a symmetric volumetric flow rate (0.06 ml/h). By restricting active flow entirely to the upper compartment of the brain chip, the flow velocity over the neurons in the lower compartment approached zero, causing diffusion-mediated molecular transport to dominate, as is observed in the brain in vivo13. Minimal shear forces on neurons and astrocytes mimic the in vivo microenvironment more closely than conventional cultures, where each medium exchange exposes the cells to non-physiological forces.

A computational convection–diffusion model of oxygen delivery based on a modified Navier–Stokes equation with Michaelis–Menten reaction kinetics confirmed that the applied flow rate (0.06 ml/min) maintained physiologically relevant oxygen levels throughout the NVU system (Supplementary Video 1). We also confirmed that the cultured endothelium retained barrier function, which is crucial to NVU function13. The barrier was measured by the restricted diffusion into the perivascular channel of both the small polar molecule Cascade Blue (CB; 530 Da; Papp = 11.2 ± 0.8 × 10−6 cm/s) (Fig. 1g; permeability was calculated Online methods Eq. (1) and modeled in Supplementary Video 2) and the larger Alexa-555 labeled-bovine serum albumin (BSA-555; ∼67 kDa; Papp = 2.7 ± 0.2 × 10−7 cm/s) (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 4). Only ∼0.1% of the BSA-555 penetrated the perivascular compartment (Fig. 1g), which is consistent with the level of penetrance of IgG (MW ∼155 kDA) into the brain, as observed in vivo14,15.

RESULTS

Fluidic coupling leads to phenotypic modulation of cells in the NVU system

To identify contributions of the different cell populations, we first used label-free proteomic analysis of endothelium, pericytes, astrocytes (glial cells) and neurons cultured either in separate BBB and brain chips or when fluidically coupled, which allows interactions mediated by secreted factors. (Proteome database link in the Online Methods; ∼1,500–2,000 proteins were identified in each compartment). Changes in proteome-wide expression were visualized with GEDI (gene expression dynamics inspector) self-organizing maps (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 5a). In the coupled system, neurons were stimulated by factors secreted and transported by endothelial cells and perivascular cells of the BBBinflux chip, whereas the effluent from the BBBefflux chip contained compounds produced or transported by cells in the entire upstream system. Coupling led to significant changes in protein expression in endothelium, perivasculature and neurons (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 5a).

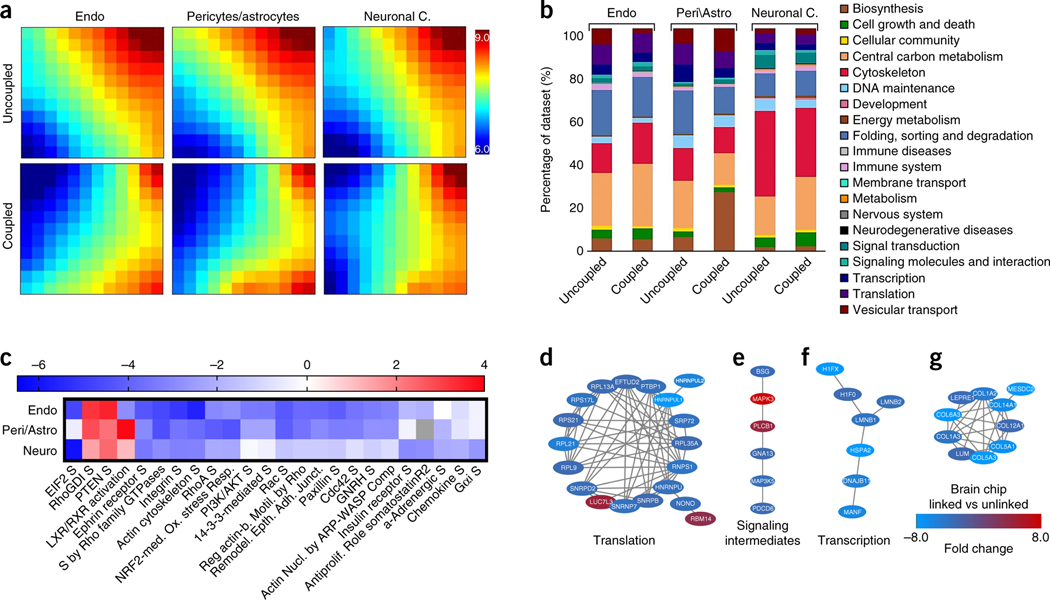

Figure 2.

Protein expression in human NVU cells in coupled versus uncoupled chips. Comparison of global protein expression profiles for cellular compartments of the NVU system and uncoupled BBB and brain chips, as measured by MS analysis and visualized using GEDI software. (a) The GEDI self-organizing map algorithm was trained on the data set and used to generate mosaics visualizing the expression profiles for endothelial cells, a mixed population of pericytes and astrocytes, and mixed populations of neuronal and astrocyte cells cultured in fluidically uncoupled chips, and contrasted with these cellular populations cultured in a fluidically coupled system. Each tile of the mosaic represents a cluster of proteins with similar expression profiles (Supplementary Fig. 5a); color scales indicate log10 normalized mass abundance, with blue representing low-abundance proteins, and red representing high-abundance proteins. (b) Bar graphs illustrating the percentage of the protein expression profiles represented by each KEGG Orthology biofunction terms for each of the compartments in uncoupled and coupled chips. Proteomaps further illustrate the KEGG Orthology biological process terms associated with low- and high-abundance proteins observed in the expression profiles of fluidically uncoupled chip compartments contrasted with expression values observed in the NVU system (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Videos 3–8). (c) IPA was used to identify the significant canonical pathway regulation, which changes due to the organ chip coupling, using Z-score, (red, high Z-score, pathway is upregulated; blue, low Z-score, pathway is downregulated; gray indicates that the pathway was not expressed). (d–g) Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed using the STRING database to identify protein complexes represented in the MS data associated with proteins that exhibited the greatest fold-change differences in expression between the coupled and uncoupled brain chips. We found PPI networks associated with translation (d), signaling intermediates (e), transcription (f) and extracellular matrix (ECM) (g) protein classes. These proteins were typically more highly expressed in the uncoupled system (blue) than in the coupled system (red).

We clustered the proteome data sets according to KEGG orthology to visualize the relative abundance (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 5b and Supplementary Videos 3–8) and variability (principle component analysis; Supplementary Fig. 5c) of proteins belonging to the dominant biological processes of each NVU compartment. In the coupled system, vesicular transport processes in vascular endothelium were downregulated compared to the uncoupled system. Studies of rodents and human in vitro cultures have shown reduced transcytotic vesicular transport in functional BBB endothelium compared to other endothelia16. In the perivascular BBB compartment, fluidic coupling upregulated the processes of amino acid synthesis and protein biosynthesis. In comparison to the other compartments (Supplementary Fig. 5b), the brain chip was more dominated by cytoskeletal function processes in both coupled and uncoupled configurations, which again is consistent with neuronal expression patterns in the human brain proteome17 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Videos 7 and 8). Notably, fluidic coupling upregulated metabolism-associated proteins in all compartments. For example, the vasculature and the brain showed an increase in carbon-metabolism-associated proteins (Supplementary Fig. 5), which have been shown to decrease DNA strand breakage, oxidative stress and apoptosis18 (Supplementary Videos 3–8).

Further canonical pathway analysis (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 5c) revealed that fluidic coupling downregulated Rho family GTPases, integrin, paxillin, Rac and actin cytoskeleton signaling, accompanied by RhoGDI upregulation in all compartments. Together with several of the other important regulated pathways (–2 > z score > 2), these data suggest that cells in the coupled system are less proliferative and less migratory19 than when cultured in isolation. Three protein clusters upregulated in the coupled system were associated with increases in translation (Fig. 2d), signal transmission intermediate molecules (Fig. 2e) and transcription (Fig. 2f), respectively, and a fourth with downregulation of extracellular matrix proteins (Fig. 2g). These changes may correspond to reduced cellular stress20 and astrocyte reactivity21 in the coupled brain chip. However, label-free proteomics should be used with caution at the level of individual proteins, and only changes larger than twofold should be considered significant. Two cell-specific proteins significantly upregulated by coupling were the pericyte-specific marker chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4) and, in the brain chip, GAP43, a protein associated with nerve growth as well as induction of axonal and dendritic filopodia22. The proteomic results demonstrate that paracrine signaling via fluidic coupling of the organ chips changes the phenotype of the cultured cell populations.

Methamphetamine transiently opens the human BBB

Methamphetamine (Meth) is known to induce reversible disruption of the BBB after acute administration in vivo and in vitro23 as well as in chronic abusers24. We used Meth to assess the utility of the NVU system for drug-modeling studies (Supplementary Fig. 6). Studies with Meth-treated hBMVECs grown in static Transwell cultures demonstrated a dose-dependent loss of barrier function, which was reversible at doses up to 4 mM Meth (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b), similar to previous in vitro results25. Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis showed that when 1.5 mM Meth was administered into the vascular channel of the BBBinflux chip (Supplementary Fig. 8a), ∼10% of 1.5 mM Meth reached the perivascular channel (Supplementary Fig. 8a). 1.5 mM is a high dose compared to in vivo plasma concentrations, which are typically in the micromolar range24; however, drug penetration into the perivascular channel was close to the plasma/ brain dialysate ratio observed in rats of ∼20–30%26. The Meth concentration in the brain chip was ∼100 µM, within the range observed in brain tissues of chronic Meth abusers (0.23–310 μM)27. At doses up to 1 mM, Meth did not decrease the viability of neurons in the brain chip (Supplementary Fig. 7c and Supplementary Video 9) or compromise BBBefflux barrier function. The sequential decrease in Meth concentration along the BBB-brain-BBB fluidic circuit occurred because of the BBBinflux chip’s barrier, addition of media, as well as absorption of Meth, and in the materials of the fluidic system as determined by mass balance calculation of Meth concentrations measured in the medium by MS (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Only low levels of Meth were taken up by the neurovascular cells as demonstrated in static well plate cultures (Supplementary Fig. 8b).

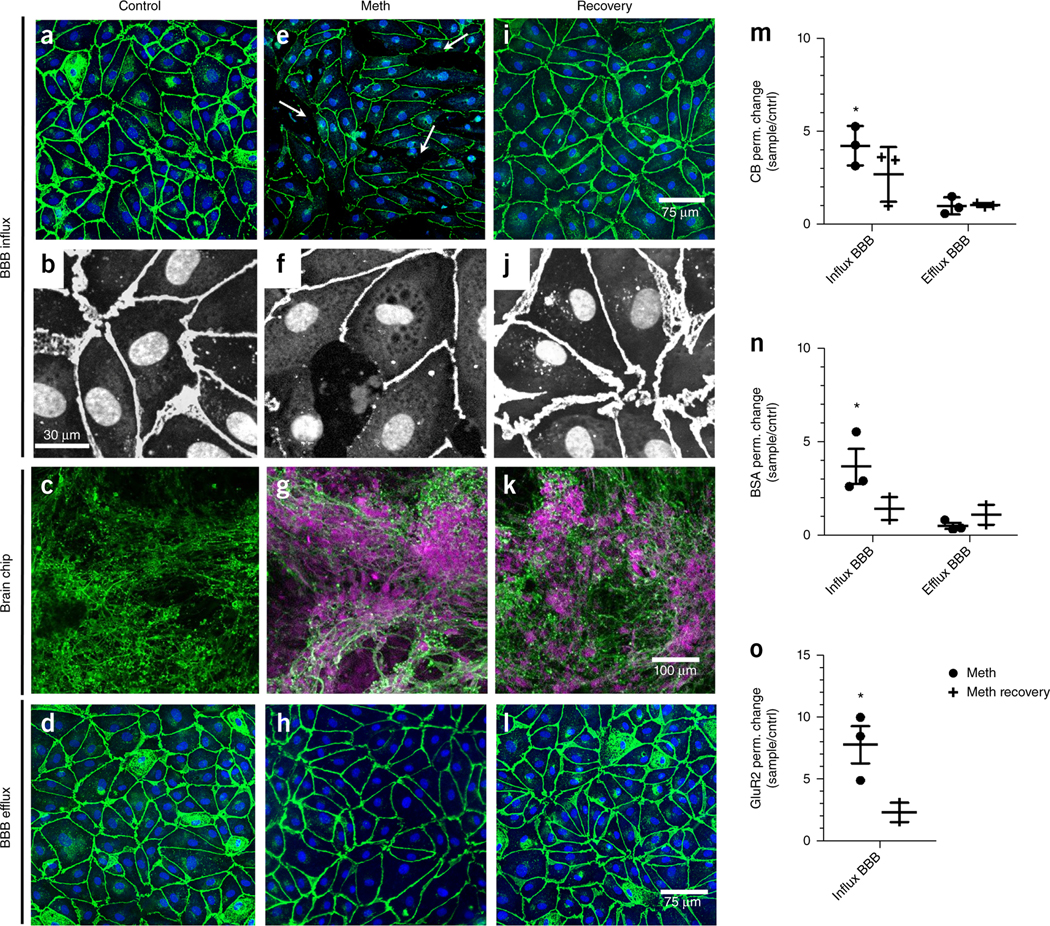

To assess changes in BBB function, influx/efflux processes and receptor expression, we added two independent fluorescent markers, CB and BSA-555, and a glutamate receptor 2 antibody (GluR2 Ab) that targets a neuron-specific extracellular domain to medium flowing through the vascular channel of the coupled BBBinflux chip (Supplementary Fig. 6). Fluorescence confocal microscopic analysis under control conditions confirmed that the endothelium formed a barrier similar to the BBB in vivo, as indicated by the presence of a continuous pattern of VE-cadherin-containing cell–cell junctions (Fig. 3a,b) and lack of GluR2 Ab penetration and staining in the brain compartment (Fig. 3c). The endothelium, pericytes and astrocytes of the BBBefflux chip demonstrated similar morphology as those in the BBBinflux chip (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 9). As previously observed in vivo23, we found that treatment with Meth (1.5 mM) caused barrier breakdown, as indicated by disruption of cell–cell junctions and lower expression of VE-cadherin (Fig. 3e,f). This resulted in increased influx of GluR2 Ab into the brain chip and, consequently, enhanced staining of the neurons (Fig. 3g), whereas there was no detectable effect on the cell–cell junctions of the endothelium in the BBBefflux chip (Fig. 3h). This agrees with our Transwell study (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b), where exposure of the brain endothelium to a Meth concentration equivalent to that seen by the endothelium in the BBBefflux chip (∼3.5 µM, a decrease of 99.7 ± 0.2% from the administered 1.5 mM dose due to transport and absorption properties of the NVU system; Supplementary Fig. 8a) did not lead to barrier breakdown. When we withdrew the Meth and cultured the cells for one additional day in fresh medium, we found that the barrier breakdown in the BBBinflux chip was reversible and the disrupted endothelial cell–cell junctions re-formed (Fig. 3i,j), resulting in partial recovery of endothelial barrier function. However, the anti-GluR2 Ab already bound to the neurons was not washed out of the brain chip (Fig. 3k); and again, the BBBefflux chip remained unaffected (Fig. 3l). Quantification of these results confirmed that Meth produced significant increases in transendothelial permeability of CB (Fig. 3m; P = 0.0092 (Supplementary Table 1), N = 3); BSA (Fig. 3n; P = 0.0497 (Supplementary Table 1), N = 3); and GluR2 Ab (Fig. 3o; P = .0114 (Supplementary Table 1), N = 3); however, this compromise of barrier function reversed within 24 h after drug withdrawal. Thus, the NVU system effectively mimics the previously reported ability of acute Meth administration to produce reversible breakdown of the BBB in both animals23 and humans24.

Figure 3.

Methamphetamine (Meth) reversibly increases BBB permeability. The BBBinflux chip recapitulates a tight barrier preventing penetration of an anti-GluR2 Ab from the vascular to the perivascular compartment during control conditions. The barrier is compromised by Meth dosing, allowing influx of the antibody. 24 h after Meth withdrawal the barrier has recovered (schematic in Supplementary Fig. 6). (a–l) Immunofluorescence micrographs of the different cell populations in the NVU system. (a) The BBBinflux chip (exhibits endothelial cell junctions stained for VE-Cadherin (VE-CAD, green). (b) Higher magnification immunofluorescence micrographs of the endothelial monolayer stained for VE-CAD (white) and CellMask to visualize nuclei and the cytoplasm (white and gray, respectively). (c) The neuronal networks in the brain chip stained for β-III-tubulin (green). During control conditions the BBB excludes the anti-GluR2 Ab from the brain compartment and leads to absence of anti-GluR2 staining (magenta). (d) The endothelial cell junctions stained for VE-CAD (green) of chipefflux demonstrating a barrier. (e) Meth administration for 24 h opens endothelial cell–cell junctions at the BBBinflux chip (indicated by white arrows). (f) Higher magnification immunofluorescence micrograph demonstrates the cell (CellMask, gray) and junction morphology (VE-CAD,white) after Meth administration for 24 h. (g) Meth addition makes the BBB leaky and allowing the anti-GluR2 (magenta) to stain the neurons (β-III-tubulin, green). (h) The endothelial cell junctions (VE-CAD, green) at the efflux chip were intact due to the low Meth concentration at this chip. (i) Meth administration was stopped, the endothelial cell junctions (VE-CAD, green) show recovery and the cell layer regains confluency after 24 h. (j) Panel i at higher magnification. (k) Meth withdrawal results in recovery of the BBB while anti-GluR2 Ab remains attached to the neurons. (l) The endothelial cell junctions (VE-CAD) at the efflux chip were intact and not affected by the Meth withdrawal. The experiment represented by the immunofluorescence micrographs was repeated three times with two to four individual NVU systems for each repeat. (m–o) Graphs showing mean relative changes in permeability (ratio) of BBB chips dosed with Meth for 24 h (black) and 24 h after recovery (gray), relative to control conditions, when analyzed using small molecular weight CB (530 Da), (*P = 0.0092, Supplementary Table 1a). (m) larger molecular weight BSA (∼67 kDa), (*P = 0.0497, Supplementary Table 1a). (n) or anti-GluR2 antibody (∼155 kDa), (*P = 0.0114, Supplementary Table 1a). (o) Error bars are s.e.m., N = 3, representing independent NVU systems, significance testing unpaired t-tests versus control.

Metabolic coupling between the compartments of the human NVU

The NVU is known to transfer metabolic substrates between the vasculature and the brain parenchyma, but the molecular basis of the communication between the cells within these adjacent microcompartments is poorly understood5,28. Brain metabolites have of cell populations located in different brain regions30. But it has not been studied in human cerebral spinal fluid29 and biopsies5, and ani- been possible to analyze the contributions of individual cell popumal studies have provided insight into the metabolomic characteristics lations in different physiological microenvironments or how they interact in vivo. We carried out untargeted MS metabolic analysis of the secretome produced by each physiological compartment of the NVU in both uncoupled and coupled chips. Principle component analysis verified that each compartment expressed a distinct secretome (Fig. 4a). The endothelial and perivascular cells of the BBB chips secreted higher numbers of different types of molecules than the neurons of the brain chip (Supplementary Fig. 10). A majority of these molecules were related to metabolic pathways (Fig. 4b,c, Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Tables 2–7), confirming that the vascular and perivascular niches maintained high metabolic activity in the NVU system.

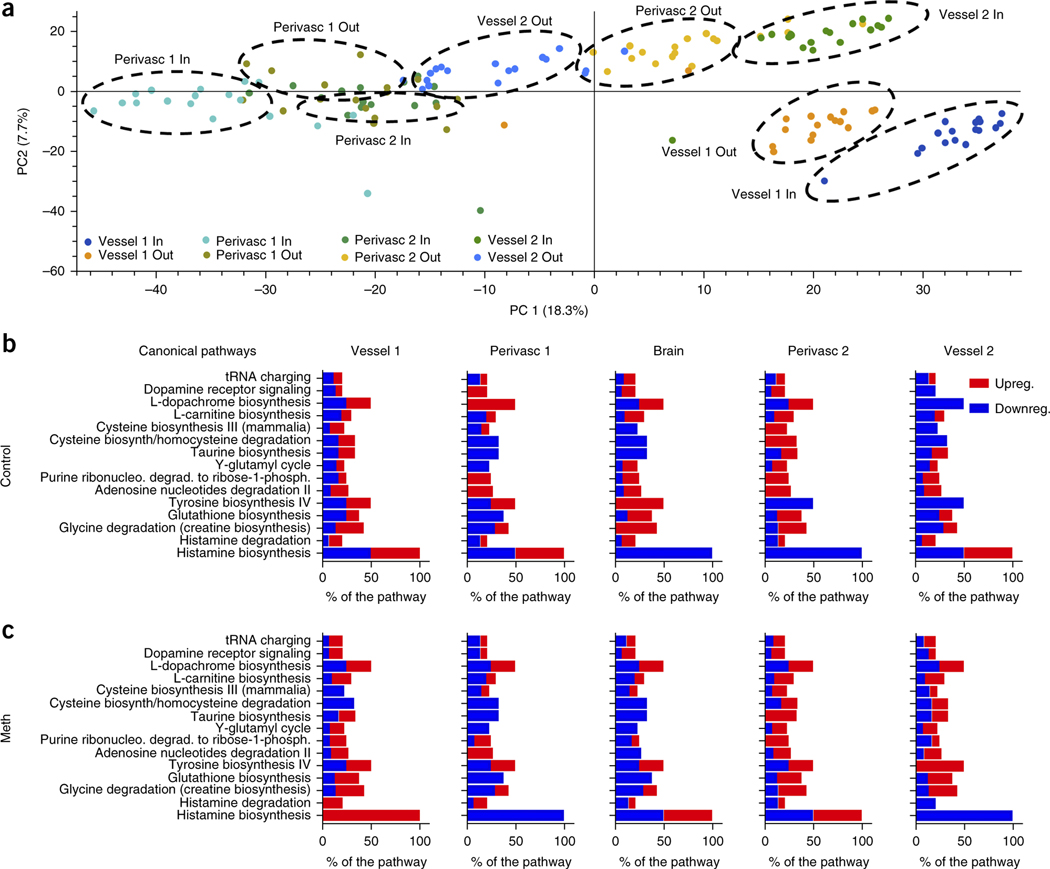

Figure 4.

Untargeted metabolic analysis of the cellular compartments in the NVU system. (a) Principle component analysis (PCA) was used to assess the expression variations and abundance of all the metabolites (up to ∼3,000 MW) detected in the different compartments of the NVU system by untargeted MS. The compounds organize in clusters that correspond to the different NVU microfluidic compartments: inflow (Vessel 1 in) and outflow (Vessel 1 out) of the vascular channel of the BBBinflux chip, inflow (Perivasc 1 in) and outflow (Perivasc 1 out) of the perivascular channel of the same BBB chip, inflow (Vessel 2 in) and outflow (Vessel 2 out) of the vascular channel of the second BBBefflux chip, and the inflow (Perivasc 2 in) and outflow (Perivasc 2 out) of the perivascular channel of the BBBefflux chip (note that Perivasc 1 out and Perivasc 2 in are also the inflow and outflow of the brain chip, respectively). (b,c) IPA was used to identify the important canonical pathways and how they are regulated over the compartment and during control. N = 6, representing independent NVU systems, over three time points (b) and Meth conditions (c). The bar shows the percent of the pathway that was found in our metabolic analysis and the regulation was analyzed using Z-score, (red, high Z-score, pathway is upregulated; blue, low Z-score, pathway is downregulated).

Meth exposure significantly altered (>2-fold change, P < 0.05) components of specific pathways identified by KEGG analysis (Fig. 4b,c, Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Tables 2) identification based on potential metabolite ID). These data correlated with data from long-term Meth abusers, which showed downregulation of the neuronal metabolite N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) and upregulation of uric acid secretion (Supplementary Tables 2), as well as altered regulation of glutamate and glycolysis pathways31 (Supplementary Tables 4 and 6 and Supplementary Fig. 10). We also identified many metabolites previously suggested as potential clinical markers of Meth abuse based on animal studies (Supplementary Tables 2). Additional correlations with animal data were seen in pathway (Fig. 4b,c) and functional (Supplementary Fig. 10) analysis of the effects of Meth on energy metabolism, citric acid cycle and oxidative stress (e.g., glutathione biosynthesis and taurine biosynthesis pathways).

Our untargeted MS metabolic study of the impact of Meth on the human NVU identified metabolic pathways related to regulation of neutrotransmitters, such as dopamine (e.g., tyrosine biosynthesis IV and L-dopachrome biosynthesis) and histamine biosynthesis. These pathways correlated well both with clinical data and previous studies23,24,27,32, dissecting how the fact that each compartment responds to Meth exposure individually showed that perivascular cells are more susceptible to Meth in terms of the higher number and variety of metabolic alterations they express compared to the neighboring endothelium (Fig. 4b,c, Supplementary Fig. 10, and Supplementary Tables 2–8).

We studied interactions critical for regulation of neuronal function and signaling by comparing our label-free proteomic results and untargeted MS metabolite data (Supplementary Table 8). The canonical pathways that correlated most significantly were related to basal maintenance of neurons (glutathione biosynthesis33, L-carnitine biosynthesis34, glycine degradation35), neuronal protection by the vasculature and perivasculature (L-cysteine degradation, cAMP regulation) and neurotransmitter levels (adenosine nucleotides degradation36). These findings further demonstrate how the secreted metabolome of the BBB provides chemical cues that help to maintain neuronal functionality. In the NVU, the synthesis and signaling of the key neurotransmitters, glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), are coupled to pyruvate and lactate levels via the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and glutamine–glutamate shuttling (Fig. 5a)37. However, the location where each metabolite is produced and where basal energy shuttling and amino acid conversions take place remains unknown13,28. It is known that brain endothelial cells and astrocytes primarily depend on glycolysis38, whereas neurons typically rely on lactate and pyruvate as energy sources (Fig. 5a)37. In contrast, metabolic flux in brain pericytes has not been reported, and thus, basic attributes, such as whether pericytes depend on glycolysis remain an open question.

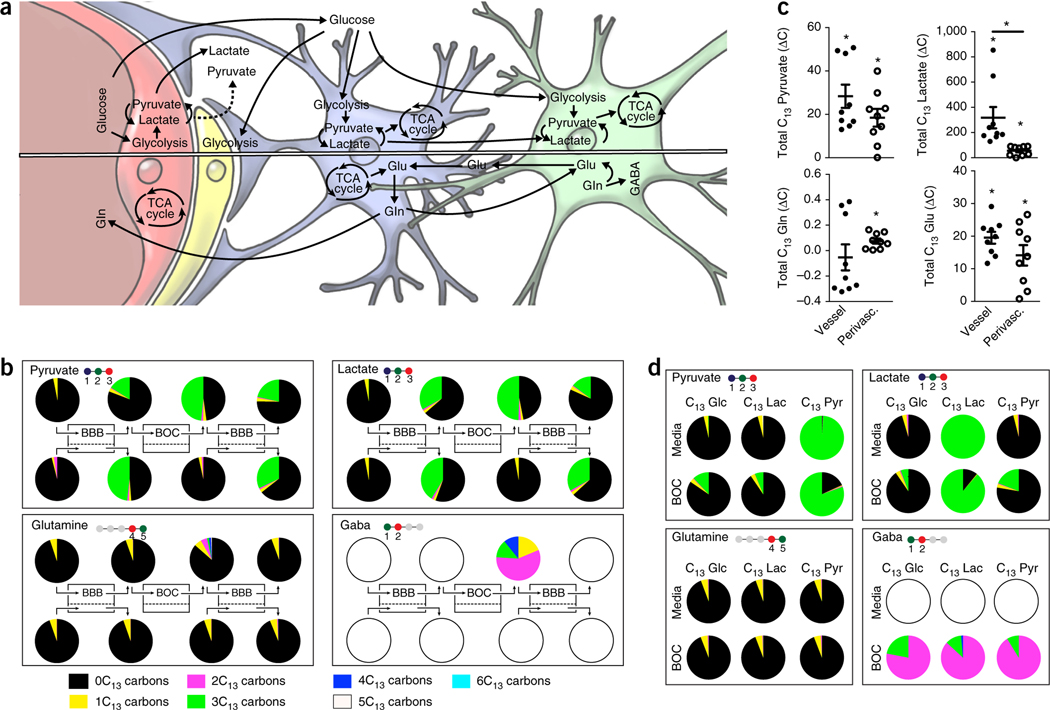

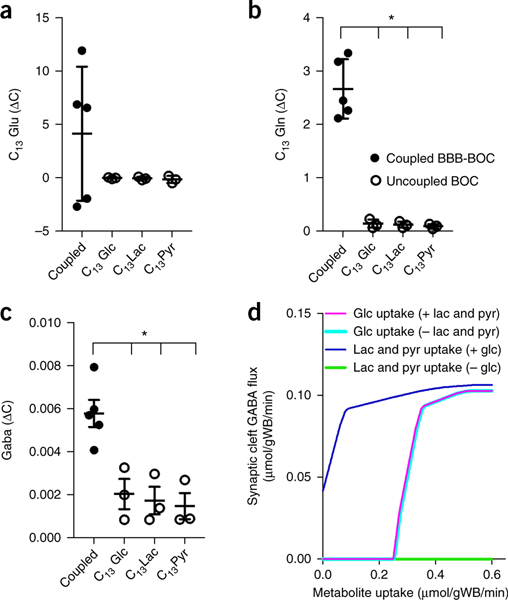

Figure 5.

Linked cell metabolism in the NVU system. (a) Simplified schematic representation of how glucose and glutamate (Glu)–glutamine (Gln) cycles are thought to interplay with all four cell types of the NVU—endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes and neurons. A simplified sketch of the pathways of glycolysis (TCA cycle and Glu/Gln/GABA cycles) can be found in Supplementary Fig. 11. (b) Graphic depictions of the distribution of the C13-labeled metabolites, pyruvate, lactate, glutamine and GABA measured by MS analysis when C13-labeled glucose was provided as the only glucose source in the NVU system. The number of carbons in respective compound is illustrated in the ball-and-stick molecular illustration where the colored balls show number of carbons incorporated in each glycolysis-TCA cycle turnover (i.e., pyruvate has three carbons, all of which are coming from glucose, while glutamine has five carbons, but only two coming from glucose in one cycle, see Supplementary Fig. 11). The pie charts, showing percentage of C13-labeled carbons for each analyte (i.e., 3C13 refer to molecule with three labeled carbons), are positioned above or below the sampling points along the NVU system diagrammed at the center. (c) The change in concentration of C13-labeled metabolites derived from each of the influx BBB compartments vascular (black), *P values: pyruvate = 0.0008, lactate = 0.0056, Gln = 0.6178, Glu < 0.0001 or perivascular (unfilled); *P values: pyruvate = 0.0019, lactate = 0.0021, Gln = 0.0060, Glu = 0.0020, (averages ± s.e.m., N = 3 representing independent NVU systems, with one time point, and N = 2 representing independent NVU systems with three time points), significance showed versus no change over the compartment ∆C = 0, unpaired two-tailed t-test (Supplementary Table 1a). Lactate vascular versus perivascular *P = 0.0074 unpaired t-test. (d) Isotype distribution of pyruvate, lactate, Gln and GABA in unlinked brain chips supplied with C13-labeled glucose (Glc), lactate (lac) and pyruvate (pyr), respectively.

To study the metabolic coupling among these various cell populations of the NVU, we supplied only C13-labeled glucose (6C13) exclusively to the vascular channel of the BBBinflux chip and then followed the generation of C13-labeled metabolites with high-resolution MS in each of the downstream microfluidic compartments (Supplementary Fig. 11a). This allowed us to analyze the metabolic contributions of each compartment of the NVU system to the biochemical pathways associated with glycolysis, the TCA cycle and the glutamine–glutamate cycle (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 11). We found that C13glucose underwent physiological glucose transport across the BBB in the influx chip and penetrated into all downstream compartments. These studies recapitulated the bidirectional glucose fluxes observed in the brain, with a net glucose flux from blood to brain, as previously observed in vivo39. Metabolism in each of the compartments resulted in changes in the amount and ratios of the carbon isotopes of the glucose metabolites, pyruvate, lactate, glutamine and glutamate (Fig. 5b). Identification of a consistent increase in the ratio of C13-pyruvate and C13-lactate measured in each downstream compartment compared to its upstream compartment revealed that glycolysis occurred in all compartments of the NVU system (Fig. 5b,c). Neural glycolysis is likely to be carried out by astrocytes in the brain chip, given the brain’s preference for pyruvate as a neuronal energy source37. Moreover, the overall consistency in the relative changes in C13-pyruvate and C13-lactate may be attributed to the rapid enzymatic conversion between these two metabolites.

In these studies, we also detected glutamine conversion to glutamate as a result of shuttling of lactate and pyruvate via the TCA cycle. Glutamine synthesis was observed in all compartments containing astrocytes (i.e., perivascular compartments of the BBB chips and brain chip). Higher C13-glutamine levels (and isotope ratio) were measured in the brain chip (Figs. 5b and 6) where astrocytic glutamine secretion may be stimulated by communication with neurons40. While glutamate is a key neurotransmitter produced by neurons, it is also synthesized by endothelial cells41, and accordingly, we observed glutamate synthesis in both the vascular and perivascular compartments (Fig. 5c) of the BBB chip and brain chip, which is again consistent with the in vivo phenotypes of these cells37. We also found that the C13-labeled neurotransmitter, GABA, was exclusively produced by the cells of the brain chip (Fig. 5b,d), which also confirms the functionality of the resident neurons.

Figure 6.

Brain chip metabolite production is altered by coupling to the BBB. (a–c) The mean production/consumption of glutamate (Glu) (a), glutamine (Gln) (b) and GABA (c) depends on the substrate available for the neuronal culture. The neuronal cultures in the brain chip were given different C13-labeled metabolic substrates that are essential for GABA production. The labeled substrates arrived directly to the brain chip (uncoupled system, unfilled) and through the vasculature of BBB (linked system, black). Gln *P values for all comparisons versus the coupled NVU system <0.0001; GABA *P values: glucose (Glc) = 0.0124, lactate (Lac) = 0.0073, pyruvate (Pyr) = 0.0048, (Supplementary Table 1a). Error bars are s.e.m., N = 3 for uncoupled systems and 5 for coupled systems, significance calculated with one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test, (Supplementary Table 1a). (d) Theoretical metabolic flux balance analysis of the synaptic cleft. GABA exchange is shown as a function of the uptake of glucose or equal amounts of lactate and pyruvate in the presence or absence of metabolites in parentheses. All fluxes are reported as μmol·g wet brain−1·min−1.

We compared secretomes from coupled (Fig. 5b) and uncoupled (Fig. 5c) brain chips and found significantly higher levels of GABA in the coupled brain chip. To evaluate the contribution of the vascular endothelium to synthesis of neuronal GABA and glutamate/glutamine, we supplied uncoupled brain chips separately with C13-labeled glucose, lactate or pyruvate at the concentrations detected experimentally in the inlet of the coupled brain chip. Past culture studies have revealed that neuronal synthesis of glutamate and GABA is highly dependent on an external supply of glutamine, typically thought to be provided by astrocytes37. We found that C13-glutamine secretion was significantly higher in coupled brain chips (Fig. 6b), demonstrating that metabolites from the vascular endothelium and perivascular cells directly influence glutamine production by astrocytes and neurons in the brain chip.

The coupled brain chip also demonstrated an alteration in C13-labeled glutamate distribution (but not an absolute change in concentration; Fig. 6a), which was likely due to high turnover by the astrocytes, whereas there were no changes in glutamate in the uncoupled brain chips (Supplementary Fig 11c). Thus, again, factors secreted by the BBB chip influenced the metabolic processes of neurons in the brain compartment. Glutamate transferred to the brain chip is likely to be taken up by astrocytes, converted to glutamine and shuttled to the neurons, which then synthesize intracellular glutamate, as they do in vivo37.

Synthesis of GABA is highly dependent on primary energy sources (glucose, lactate and pyruvate) and glutamate/glutamine supply37 and could only occur in the brain chip, the only compartment containing neurons (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 2). To identify how metabolites from the vascular and perivascular compartments influence GABA production, we modeled the metabolic flux of GABA turnover in the synaptic clefts at contact points between astrocytes and neurons. This analysis suggested that free exogenous pyruvate and lactate, which is not directly supplied in the cleft by astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 12) or taken up by astrocytes and directly supplied to the neurons (Fig. 6d), can contribute to neurotransmitter synthesis. In the coupled NVU system, we measured extracellular GABA (i.e., that escaped from synaptic clefts; Fig. 5b), and verified that C13-GABA was synthesized in uncoupled brain chips supplied with C13-lactate or C13-pyruvate, experimentally confirming the exogenous substrate hypothesis that underlies the model (Fig. 6c). More importantly, the levels of GABA synthesis in the coupled brain chip were significantly higher than in the uncoupled chips (Fig. 6c), indicating that factors produced by vascular endothelium and/or cells of the perivascular niche can indeed influence neurotransmitter synthesis in the brain neuronal compartment.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that our linked organ chip system mimics metabolically critical physiological functions of the NVU, including prolonged and increased expression of metabolic enzymes42, more effectively than static mono- and co-cultures of human cells. In recent studies, microfluidic models of different organs, such as the lung, liver and kidney, have been fluidically linked to create human ‘body-on-a-chip’ models43. In contrast, we linked three chips representing different functional units of the same organ—the human brain—to develop a compartmentalized model of the NVU. By comparing the functions of individual cell types in the NVU system and in isolated chips, we obtained new insights into how the different endothelial, perivascular and neuronal cell populations that make up the NVU interact metabolically and collaborate physiologically to maintain brain functions.

The brain endothelium is unique in that its specific barrier properties allow it to transport substances from flowing blood to the brain parenchyma and to exclude many toxic agents2,4,13,16. Using the NVU system, we also demonstrated that the reversible effects of the neuroactive drug, Meth, on the human BBB, previously observed in vivo can be mimicked in vitro. We found that Meth exerted its effects preferentially on the influx BBB, whereas we did not detect any changes in the efflux BBB. Our analysis of the proteome of the NVU system extends the current proteomic characterization of human neural and neurovascular cells in an experimental system with in vivo-like fluidic coupling, which allows both direct vascular-perivascular interactions and secretome-mediated interactions with the parenchymal compartment. These findings complement results of previously reported studies of human tissue proteomics44 and transcriptomics45, as well as experiments with monocultures of astrocytes46 and endothelial cells47. Using this analysis, we confirmed that the four cell types in the NVU system more closely recapitulated the phenotypes of the cells in the corresponding compartments of the human NVU in vivo than did previous in vitro models.

While it is known that the brain microvasculature indirectly affects neuronal metabolism by altering nutrient availability through regulation of brain blood flow, the question of whether the vasculature directly affects neuronal metabolism via its metabolic products or secreted factors remains open. Our NVU system revealed previously unknown metabolic interactions between the microvasculature and brain neurons. These interactions significantly increased the neuronal synthesis and secretion of important neurotransmitters, including glutamate and GABA, as a result of direct neuronal utilization of vascular metabolites. These findings suggest that the brain vasculature may play a metabolic role in disease states, given the increasing evidence suggesting a relation between alterations in neurometabolism and neuropathologies, such as neurodegeneration48, stroke49, traumatic brain injury50 and Alzheimer’s disease48.

Thus, our results suggest the utility of the NVU system for a diverse set of applications, including the assessment of drug delivery systems designed to cross the human BBB and the evaluation of drug penetrance and localized drug target effects, as well as off-target effects, in a more direct way than with previously reported BBB/NVU models12. The approach also may facilitate future studies focused on mechanisms of BBB function and its relation to both normal and diseased functions of the central nervous system.

METHODS

Methods, including statements of data availability and any associated accession codes and references, are available in the online version of the paper.

ONLINE METHODS

Microfluidic chips, fabrication and pretreatment.

BBB chip.

Microfluidic devices were produced by soft lithography from Sylgard 184 polydimethylsiloxane using molds made with stereolithography, see Supplementary Notes. The dimensions are given in the legend of Figure 1.

Brain chip.

The brain chip is composed of two polycarbonate (PC) parts; for fabrication see Supplementary Notes.

Cell culture.

Primary human cell culture.

Human hippocampal neural stem cells HIP-009 cells at passages 8–15 (PhoenixSongs Biological, Brandford, CT, USA) were plated for differentiation on poly-D-lysine, laminin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA)–coated TOPAS substrates in Neuronal Differentiation Medium (PhoenixSongs Biological, Brandford, CT, USA). The differentiation process was performed for 3–4 weeks, during which half of the medium was changed twice a week. All neural stem cell culture before mounting the cells in the brain chip was performed at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 2% O2 and 5% CO2. HIP-009 cells at passages 8–15 were used.

Cortical human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMVECs, CellSystems, Kirkland, WA, USA), were maintained with Cell Systems Corporation (CSC) complete medium (Cell Systems, Kirkland, WA, USA, Cat#ACBR371) on regular tissue culture flasks coated with Attachment factor (Cell Systems, Kirkland, WA, USA). Human astrocytes and human brain pericytes of cortical origin (ScienCell, San Diego, CA, USA, Cat#1200) were maintained in astrocyte and pericyte medium respectively (ScienCell, San Diego, CA, USA, Cat#1800). All cells were used before the sixth passage.

For individual well-plate cultures and uptake of Meth, human hippocampal neural stem cells, endothelial cells, astrocytes and pericytes were cultured in well-plates and exposed to 50 µM Meth for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of ambient O2 and 5% CO2. Media was sampled and analyzed with mass spectrometry (M.S) as described below.

Transwell cell culture.

BBB chip culture.

Chips were coated with a mixture of fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and collagen IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) at 200 µg/ml in cell culture grade water (ultrapure H2O) for >4 h. Human cortical astrocytes and pericytes (3:1 in number ratio) were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml in the apical channel. After 1 h attachment time cortical brain microvascular endothelial cells were seeded at a density of 4.8 × 106 cells/ml in the basal channel, incubated for 30 min and followed by upside down incubation for 1 h to allow attachment on both the porous membrane and the bottom of the chip. Chips were fed daily by a gravity driven flow of ∼50 µl/min for 4 min until a complete endothelial monolayer was formed. Media was exchanged to endothelial media (see below) with 250 µM cAMP (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and 17.4 µM RO20–1724 (St Cruz Biotech, St Cruz, CA, USA) and chips were connected to pressurized media inlets (∼10 cm H2O) and a peristaltic pump running at 1 µl/min.

Brain chip culture.

TOPAS substrates were first treated with poly-d-Lysine 5 μg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for 15 min on an area defined by a PDMS mask (44 mm2). The exposed area was rinsed 3 times with ultra-pure water and incubated 2 h with laminin from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm murine sarcoma basement membrane (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) 10 μg/ml at room temperature. Neurons were then seeded at a density of 100,000 cells/ TOPAS substrate through the PDMS mask. 1 h after seeding, the mask was removed and the TOPAS substrate was incubated in Neuronal Differentiation Medium (PhoenixSongs Biological, Brandford, CT, USA). The neuronal cultures were differentiated for 3–4 weeks at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 2% O2 and 5% CO2 with half medium change twice a week. After the differentiation phase, the TOPAS substrates were mounted on the brain chip as described above. The chips were perfused with Neuronal Differentiation Medium (PhoenixSongs Biological, Brandford, CT, USA) at 1 μl/minute at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 21% O2 and 5% CO2 (further described in the Supplementary Notes).

BBB and brain chip media.

BBB-brain-BBB system.

BBB chips treated with cAMP and RO20–1724 for 3–4 days were linked to brain chips via the apical channels. Brain chips had cultures matured for 3–4 weeks. Briefly, all channels had pressurized inlets, reservoirs of BBB chips at ∼10 cm H2O and of brain chips at ∼5 cm H2O, and liquid flow (1 μL/min) was regulated by a peristaltic pump attached to the outlet of each channel. The apical outlet of the influx BBB directly fed into the inlet of the brain chip, whose outlet fed into the apical inlet of the efflux BBB. Media flow was established with endothelial and brain media (Supplementary Fig. 1e), where C13 glucose and permeability tracers CB and BSA-555 100 µg/ml in the basal channel of the influx BBB. After 24 h of flow samples were collected and in the basal channel of the inlet BBB, 1,500 μM Methamphetamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and 10 μg/ml GluR2 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was added. After an additional 24 h Meth was withdrawn to evaluate recovery for 24 h.

Practical guidance in setting up the BBB-brain-BBB chip system. See Supplementary Notes.

Analytical methods.

αGluR2 ELISA was carried out as a Sandwich ELISA (Supplementary Notes).

Live dead assay was carried out with standard reagents (Supplementary Notes).

Fixation, staining and imaging was carried out with standard reagents (Supplementary Notes).

Permeability calculation.

The media from the different compartments was collected and the concentration of CB and BSA tracers in effluent was determined by using BioTek Neo (BioTek Instruments, Inc. Winooski, VT, USA). From these data, apparent permeability (Papp) was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

where VR is defined by the volume of receiving channel effluent after time t, CR is the measured concentration of tracer in receiving channel effluent, t is time of effluent collection, A is the area of the main channel, Vd is defined by the volume of dosing channel effluent after time t and Cd_Out is the concentration of dosing medium. As was presented in Figure 1, the absolute Papp values mentioned above and ratio of the penetrance between CB and BSA-555 (average 41.4) was similar to in vivo results previously observed (ratio 24.7) with similar size molecular species (Lucifer Yellow; 457 Da; Papp = 31.6 ± 1.87 × 10−6 cm/s) and BSA-Rhodamine (69 kDa; Papp = 1.27 ± 0.48 × 10−6 cm/s) in rat brain microvessels15.

Mass spectrometry – metabolomics.

Pyruvate, lactate, glucose, glutamine, glutamate and GABA was quantified with targeted mass spectrometry. All other metabolites were identified with untargeted mass spectrometry. See Supplementary Notes. Metabolic pathways were identified by using Mummichog 1.0.3 (refs. 51,52) a Python-based software which predicts network activity and significantly affected pathways from high-throughput metabolomics.

Mass spectrometry analysis.

Label-free proteomics was carried out with state-of-the-art methods, (Supplementary Notes). The proteomic data sets of each of the BBB-brain-BBB chip compartments in coupled and uncoupled configurations were added to the center of computational mass spectrometry, and can be found in the following database:

http://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/status.jsp?task=6370ee74ab3e45f897396a8a5cac3412

Mass spectrometry analysis.

Raw data were submitted for analysis in Proteome Discoverer 2.1.0.81 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) software. Assignment of MS/MS spectra were performed using the Sequest HT algorithm by searching the data against a protein sequence database including all entries from the Human UniProt database (SwissProt 16,768 2016) and known contaminants such as human keratins and common laboratory contaminants. Sequest HT searches were performed using a 20 p.p.m. precursor ion tolerance and requiring each peptide’s N/C termini to adhere with Trypsin protease specificity while allowing up to two missed cleavages. Cysteine carbamidomethyl (+57.021) was set as static modifications while methionine oxidation (+15.99492 Da) was set as variable modification. MS2 spectra assignment false discovery rate (FDR) of 1% on protein level was achieved by applying the target-decoy database search. Filtering was performed using a Percolator (64-bit version53). For quantification, a 0.02 m/z window centered on the theoretical m/z value of each the six reporter ions and the intensity of the signal closest to the theoretical m/z value was recorded. Reporter ion intensities were exported in the result file of Proteome Discoverer 2.1 search engine as an excel table. All fold changes were analyzed after normalization between samples based on total unique peptides ion signal.

Gene Expression Dynamics Inspector (GEDI).

Visual representations of the global protein expression profiles of the samples were created using Gene Expression Dynamics Inspector version 2.1 software54. This program uses a self-organizing map (SOM) algorithm to reduce data dimensionality by classifying proteins with similar expression profiles into discrete groups that are organized into distinct two-dimensional mosaics. Each tile of these mosaics represents a cluster of proteins and the mapping of proteins to these tiles is conserved across samples to facilitate comparison. Coloration of each mosaic tile indicates the fold-change value of the centroid learned during SOM training. For the proteomics data collected in this study, GEDI mosaic grid size was set to 11 × 12. SOM training occurred in two phases with 200 iterations in the first phase, and 800 iterations in the second phase. All other SOM parameter settings were set to default values. Since we were interested in identifying how metabolic coupling affected the protein expression profiles of each NVU compartment, the expression profiles for each of the coupled and uncoupled NVU compartments were individually compared, that is, GEDI maps for Endo coupled and uncoupled, for Peri/Astro coupled, and for neuronal cultures coupled and uncoupled.

Proteomaps.

Proteomaps illustrating the composition and abundance of the functional categories represented in the sample proteomes were constructed using Proteomaps version 2.0 software55. These maps are constructed from Voronoi diagrams that are divided into polygons representing top level KEGG Orthology56 biological process terms, which are in turn subdivided based on the sub-categories represented in the protein expression data set. The area of the individual polygons comprising the map is a function of the abundance of the proteins they represent. The coloration of the polygons facilitates visual distinction of the biological processes represented in the Proteomaps and has no quantitative interpretation. The percentage of each protein expression profile represented by the biological processes observed after Proteomaps analysis of the coupled and uncoupled NVU compartments were calculated and illustrated as bar graphs using the Pandas Python library.

Python scripts using the Pandas numpy, matplotlib, and sklearn libraries were used to determine the breakdown of KEGG Orthology terms in the mass spectrometry data sets, as well as perform Principal Components Analysis on the coupled versus uncoupled mass spectrometry data sets for each cellular compartment. Python scripts are available in Supplementary Scripts 1 and 2 and at https://github.com/spsheehy/Proteomics.

Protein–protein interaction network analysis.

Protein–protein interaction networks were constructed using the Search Tool for Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database, version 10.0 (ref. 57). The STRING database stores information about functional relationships between proteins that are derived from a number of sources. For the analyses performed in this study, only known experimental interactions imported from primary database sources, and pathway knowledge parsed from manually curated databases were considered. Edges in the network graphs were chosen to represent the confidence that the interaction between two proteins represents a true functional interaction, as judged from evidence provided by the knowledge sources considered. Only high-confidence interactions (i.e., Interaction scores > 0.7) were considered in this study.

Ingenuity pathway analysis.

QIAGEN’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, QIAGEN Redwood City, https://www.qiagen.com/ingenuity) was used to identify pathways for which a substantial number of upstream regulators are present in the protein expression data set, as inferred from z-score analysis based on prior knowledge stored in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base.

COMSOL Simulation Computational Model.

Fluid Dynamics and Chemical Species Transport and Reaction Kinetics were model by using COMSOL (COMSOL, Multiphysics 5.0, Stockholm, Sweden), see Supplementary Notes; parameters used are in Supplementary Tables 9 and 10.

Metabolic flux balance analysis.

Flux balance analysis (FBA) was used to study the metabolic interactions between the neurons and astrocytes, as well as their reliance on external metabolite sources58,59. FBA uses a mathematical representation of all the known reactions in an organism to determine the flow of metabolites through these reactions that maximize a biological objective. Any reaction or combination of reactions can be optimized to model phenotypes such as growth rate, ATP production or synthesis of a metabolite of interest. In FBA, a set of mass balance constraints is applied to the metabolic model. These are defined by the stoichiometric matrix, S, of dimensions m × n where m is the number of metabolites and n is the number of reactions in the model. Each element in S is the stoichiometric coefficient of a metabolite in any given reaction in which it participates. Flux balance analysis relies on the assumption that the system being modeled has reached steady state and thus all metabolite concentrations do not change. This assumption allows for the representation of the FBA optimization problem as:

| (2) |

where v is the vector of metabolite fluxes through each reaction. Experimental data are used to place bounds on elements in v, which is constrained by reaction directionality and enzymatic capacity. With these additional constraints, the distribution of fluxes is defined as:

| (3) |

Linear programming is then used to solve the optimization problem and define the resulting fluxes through each reaction.

Our application of FBA relies on a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of the human neuron and astrocyte, which contains all the metabolic reactions that are known to occur in both cell types60. This model is based on the human metabolic network reconstruction Recon 1 (ref. 61), as well as on proteomic and metabolic data that map gene expression in the parenchymal cells to metabolic reaction activity. Because GABA flux from the brain chip compartment was measured, the study’s GABAergic neuron-astrocyte reconstruction was selected as the most relevant to our application. The model contains an extracellular compartment, as well as neuronal and astrocytic cytoplasmic and mitochondrial compartments. Transport reactions between these compartments are unconstrained (vmax = 1,000), and vmax values of exchange reactions with the environment were defined experimentally in the study. All fluxes are reported as µmol·g wet brain−1·min−1 and all FBA simulations were carried out using the COBRA toolbox, a MATLAB package (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) for FBA model optimization62. The solver Gurobi 6 (Gurobi Optimizer Version 6.0. Houston, Texas: Gurobi Optimization, Inc.) was used for all LP problems. The genome-scale metabolic model used by Lewis, N.E. et al.60, in addition to the MATLAB scripts used, are available in Supplementary Scripts 3 and 4 and at https://github.com/arpacheco/BBB_FBA.

The objective function for the neuron-astrocyte model was initially the sum of fluxes of ATP in the neuron and astrocyte60. We first maximized this objective using FBA to determine the ATP demand of both cell types. The resulting fluxes were set as vmin values for their corresponding ATP demand reactions in subsequent simulations. The directionality of the lactate-pyruvate shuttle was constrained to be unidirectional (astrocyte → neuron) to measure the contribution of the astrocytes to the neuronal metabolism. With these constraints in place, neuronal GABA secretion was selected as the objective function to be maximized through FBA.

Subsequent simulations varied the vmax values of either glucose, or equimolar quantities of L-lactate and pyruvate uptake from the environment. These simulated medium conditions are summarized in Supplementary Table 11, and were used to quantify variation in GABA exchange.

Glucose, L-lactate, and pyruvate uptake vmax values were modulated from an initial vmax of zero to a maximum of 0.6 μmol/gWB/min—twice the published glucose uptake vmax. We note that published exchange vmax values of L-lactate and pyruvate are two orders of magnitude lower than that of glucose, meaning that increasing these fluxes to glucose uptake levels represents a less physiologically relevant phenotype. Nonetheless, this flux range was chosen to simulate high levels of L-lactate and pyruvate in the brain chip influx medium.

Total neuronal GABA output under any set of constraints in a given time interval was calculated using the expression:

| (4) |

where vGABA is in µmol·g wet brain−1·min−1, the mass of the neuron is estimated at 1 × 10−6 g63, and the number of neurons in the brain chip is estimated at 65,000.

Statistics.

All experiments were carried out with more than three independent experimental setups composed from multiple cohorts (different experimental setups, chips, cells, vials). In addition, multiple time points were taken to assess the system stability; exact numbers and P-values are mentioned per experiment in figure captions. Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for one-way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni posttest. For significance testing between two conditions a non-paired student’s t-test was used. The statistical tests, P values, t, df and significance listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data and code availability.

All raw data are available upon request. Scripts are available in Supplementary Scripts 1–5 and at https://github.com/spsheehy/Proteomics and https://github.com/arpacheco/BBB_FBA. In addition, all proteomics raw data for Figure 2 and Supplementary Videos 3–8 are deposited at http://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/status.jsp?task=6370ee74ab3e45f897396a8a5cac3412.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-12–2-0036 (D.E.I. & K.K.P.), and Sverige-Amerika Stiftelsen, Carl Trygger Stiftelse, Erik och Edith Fernstrom’s stiftelse (A.H.). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of DARPA or the US Government. This work also was made possible by access to the microfabrication facilities of the Center for Nanoscale Systems (CNS), a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Network (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation under NSF award no. 1541959. CNS is part of Harvard University. We also thank T. Ferrante for technical assistance, M. Rosnach and J.P. Ferrier for artwork and technical illustrations, to J.A. Goss for his help with chips design and fabrication, and the Harvard Medical School Neurobiology Imaging Facility (supported in part by NINDS P30 Core Center grant #NS072030) for consultation and instrument availability.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

D.E.I. holds equity in Emulate, Inc., consults for the company, and chairs its scientific advisory board. K.K.P. is a consultant and a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Emulate, Inc.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper

References

- 1.Banks WA From blood-brain barrier to blood-brain interface: new opportunities for CNS drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 275–292 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Itoh Y & Suzuki N Control of brain capillary blood flow. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 32, 1167–1176 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magistretti PJ & Allaman I A cellular perspective on brain energy metabolism and functional imaging. Neuron 86, 883–901 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lecrux C & Hamel E The neurovascular unit in brain function and disease. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 203, 47–59 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasilopoulou CG, Margarity M & Klapa MI Metabolomic analysis in brain research: opportunities and challenges. Front. Physiol. 7, 183 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren MS et al. Comparative gene expression profiles of ABC transporters in brain microvessel endothelial cells and brain in five species including human. Pharmacol. Res. 59, 404–413 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naik P & Cucullo L In vitro blood-brain barrier models: current and perspective technologies. J. Pharm. Sci. 101, 1337–1354 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Booth R & Kim H Characterization of a microfluidic in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier (µBBB). Lab Chip 12, 1784–1792 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prabhakarpandian B et al. SyM-BBB: a microfluidic blood brain barrier model. Lab Chip 13, 1093–1101 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griep LM et al. BBB on chip: microfluidic platform to mechanically and biochemically modulate blood-brain barrier function. Biomed. Microdevices 15, 145–150 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JA et al. Recreating blood-brain barrier physiology and structure on chip: A novel neurovascular microfluidic bioreactor. Biomicrofluidics 9, 054124 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown JA et al. Metabolic consequences of inflammatory disruption of the blood-brain barrier in an organ-on-chip model of the human neurovascular unit. J. Neuroinflammation 13, 306 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballabh P, Braun A & Nedergaard M The blood-brain barrier: an overview: structure, regulation, and clinical implications. Neurobiol. Dis. 16, 1–13 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banks WA et al. Passage of amyloid beta protein antibody across the blood-brain barrier in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Peptides 23, 2223–2226 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Easton AS & Fraser PA Variable restriction of albumin diffusion across inflamed cerebral microvessels of the anaesthetized rat. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 475, 147–157 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Z, Nelson AR, Betsholtz C & Zlokovic BV Establishment and dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier. Cell 163, 1064–1078 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uhlén M et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacques PF et al. Relation between folate status, a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, and plasma homocysteine concentrations. Circulation 93, 7–9 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridley AJ Rho GTPases and cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 114, 2713–2722 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonneh-Barkay D & Wiley CA Brain extracellular matrix in neurodegeneration. Brain Pathol. 19, 573–585 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zamanian JL et al. Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J. Neurosci. 32, 6391–6410 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frey D, Laux T, Xu L, Schneider C & Caroni P Shared and unique roles of CAP23 and GAP43 in actin regulation, neurite outgrowth, and anatomical plasticity. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1443–1454 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Northrop NA & Yamamoto BK Methamphetamine effects on blood-brain barrier structure and function. Front. Neurosci. 9, 69 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turowski P & Kenny BA The blood-brain barrier and methamphetamine: open sesame? Front. Neurosci. 9, 156 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Banerjee A, Banks WA & Ercal N N-acetylcysteine amide protects against methamphetamine-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity in immortalized human brain endothelial cells. Brain Res. 1275, 87–95 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujimoto Y et al. The pharmacokinetic properties of methamphetamine in rats with previous repeated exposure to methamphetamine: the differences between LongEvans and Wistar rats. Exp. Anim. 56, 119–129 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frankel PS, Alburges ME, Bush L, Hanson GR & Kish SJ Brain levels of neuropeptides in human chronic methamphetamine users. Neuropharmacology 53, 447–454 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bélanger M, Allaman I & Magistretti PJ Brain energy metabolism: focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell Metab. 14, 724–738 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wishart DS et al. The human cerebrospinal fluid metabolome. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 871, 164–173 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaeger C et al. The mouse brain metabolome: region-specific signatures and response to excitotoxic neuronal injury. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 1699–1712 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berman SM et al. Changes in cerebral glucose metabolism during early abstinence from chronic methamphetamine abuse. Mol. Psychiatry 13, 897–908 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng T et al. The metabolic impact of methamphetamine on the systemic metabolism of rats and potential markers of methamphetamine abuse. Mol. Biosyst. 10, 1968–1977 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vargas MR, Pehar M, Cassina P, Beckman JS & Barbeito L Increased glutathione biosynthesis by Nrf2 activation in astrocytes prevents p75NTRdependent motor neuron apoptosis. J. Neurochem. 97, 687–696 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanelli SA, Solenski NJ, Rosenthal RE & Fiskum G Mechanisms of ischemic neuroprotection by acetyl-l-carnitine. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1053, 153–161 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verleysdonk S, Martin H, Willker W, Leibfritz D & Hamprecht B Rapid uptake and degradation of glycine by astroglial cells in culture: synthesis and release of serine and lactate. Glia 27, 239–248 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fredholm BB, Chen JF, Cunha RA, Svenningsson P & Vaugeois JM Adenosine and brain function. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 63, 191–270 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schousboe A & Sonnewald U The Glutamate/GABA-Glutamine Cycle (Springer, 2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culic O, Gruwel ML & Schrader J Energy turnover of vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 273, C205–C213 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner DA & Adamson DC Neuronal-astrocyte metabolic interactions: understanding the transition into abnormal astrocytoma metabolism. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 70, 167–176 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bröer S & Brookes N Transfer of glutamine between astrocytes and neurons. J. Neurochem. 77, 705–719 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu G, Haynes TE, Li H & Meininger CJ Glutamine metabolism in endothelial cells: ornithine synthesis from glutamine via pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol 126, 115–123 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhatia SN & Ingber DE Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 760–772 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prantil-Baun R et al. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis enabled by microfluidically linked organs-on-chips. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 58, 37–64 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uchida Y et al. Quantitative targeted absolute proteomics of human blood-brain barrier transporters and receptors. J. Neurochem. 117, 333–345 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawrylycz MJ et al. An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature 489, 391–399 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malik N et al. Comparison of the gene expression profiles of human fetal cortical astrocytes with pluripotent stem cell derived neural stem cells identifies human astrocyte markers and signaling pathways and transcription factors active in human astrocytes. PLoS One 9, e96139 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urich E, Lazic SE, Molnos J, Wells I & Freskgård PO Transcriptional profiling of human brain endothelial cells reveals key properties crucial for predictive in vitro blood-brain barrier models. PLoS One 7, e38149 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Procaccini C et al. Role of metabolism in neurodegenerative disorders. Metabolism 65, 1376–1390 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sims NR & Muyderman H Mitochondria, oxidative metabolism and cell death in stroke. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1802, 80–91 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giza CC & Hovda DA The neurometabolic cascade of concussion. J. Athl. Train. 36, 228–235 (2001). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li S et al. Predicting network activity from high throughput metabolomics. PLOS Comput. Biol. 9, e1003123 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li S et al. Constructing a fish metabolic network model. Genome Biol. 11, R115 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.The M, MacCoss MJ, Noble WS & Käll L Fast and accurate protein false discovery rates on large-scale proteomics data sets with percolator 3.0. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 27, 1719–1727 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eichler GS, Huang S & Ingber DE Gene Expression Dynamics Inspector (GEDI): for integrative analysis of expression profiles. Bioinformatics 19, 2321–2322 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liebermeister W et al. Visual account of protein investment in cellular functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 8488–8493 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanehisa M & Goto S KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szklarczyk D et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D447–D452 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orth JD, Thiele I & Palsson BO What is flux balance analysis? Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 245–248 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Varma A & Palsson BO Metabolic capabilities of Escherichia coli: I. synthesis of biosynthetic precursors and cofactors. J. Theor. Biol. 165, 477–502 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lewis NE et al. Large-scale in silico modeling of metabolic interactions between cell types in the human brain. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 1279–1285 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duarte NC et al. Global reconstruction of the human metabolic network based on genomic and bibliomic data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 1777–1782 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schellenberger J et al. Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: the COBRA Toolbox v2.0. Nat. Protoc. 6, 1290–1307 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Groves PM & Rebec GV Introduction to Biological Psychology (W.C. Brown, 1988). doi: 10.1038/nbt.4226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw data are available upon request. Scripts are available in Supplementary Scripts 1–5 and at https://github.com/spsheehy/Proteomics and https://github.com/arpacheco/BBB_FBA. In addition, all proteomics raw data for Figure 2 and Supplementary Videos 3–8 are deposited at http://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/status.jsp?task=6370ee74ab3e45f897396a8a5cac3412.