Abstract

Many strains of Bacillus cereus cause gastrointestinal diseases, and the closely related insect pathogen B. thuringiensis has also been involved in outbreaks of diarrhea. The diarrheal types of diseases are attributed to enterotoxins. Two different enterotoxic protein complexes, hemolysin BL (HBL) and nonhemolytic enterotoxin (NHE), and an enterotoxic protein, enterotoxin T, have been characterized, and the genes have been sequenced. PCR primers for the detection of these genes were deduced and used to detect the genes in 22 B. cereus and 41 B. thuringiensis strains. At least one gene of each of the two protein complexes HBL and NHE was detected in all of the B. thuringiensis strains, while six B. cereus strains were devoid of all three HBL genes, three lacked at least two of the three NHE genes, and one lacked all three. Five different sets of primers were used for detection of the gene (bceT) encoding enterotoxin T. The results obtained with these primer sets indicate that bceT is widely distributed among B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains and that the gene varies in sequence among different strains. PCR with the two primer sets BCET1-BCET3 and BCET1-BCET4 unambiguously detected the bceT gene, as confirmed by Southern analysis. The occurrence of the genes within the two complexes is significantly associated, while neither the occurrence of the two complexes nor the occurrence of the bceT gene is significantly associated in the 63 strains. We suggest an approach for detection of enterotoxin-encoding genes in B. cereus and B. thuringiensis based on PCR analysis with the six primer sets for the detection of genes in the HBL and NHE operons and with the BCET1, BCET3, and BCET4 primers for the detection of bceT. PCR analysis of the 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer region revealed identical patterns for all strains studied.

Many strains of Bacillus cereus cause food poisoning and other infections. Two principal types of food poisoning caused by B. cereus, emetic and diarrheal, have been described. The emetic type is effected by a small cyclic heat-stable peptide, which cause vomiting a few hours after ingestion. Diarrheal types are attributed to enterotoxins, a group of heat-labile proteins causing abdominal pain and diarrhea after incubation for 8 to 16 h and vegetative growth of the bacteria in the intestine (8, 22).

The enterotoxins are proteins causing cytotoxicity, fluid accumulation in the ligated ileal loop of experimental animals, and dermonecrosis and are lethal for mice (8, 22). Two protein complexes from B. cereus strains, hemolysin BL (HBL) and nonhemolytic enterotoxin (NHE), and an enterotoxic protein, enterotoxin T (bc-D-ENT), with these characteristics have been characterized. HBL, characterized from B. cereus F837/76, contains three protein components: a binding component B, and two lytic components L1 and L2 (3). The B component, encoded by the hblA gene, was cloned and sequenced by Heinrichs et al. (13), and the genes for L1 and L2 (hblC and hblD) were sequenced by Ryan et al. (26). Mäntynen and Lindström (20) found by PCR that hblA occurred in all enterotoxic strains studied; Hsieh et al. (15) found the gene in 31% of 84 strains studied, and Prüss et al. (25) found it in 43% of their 23 strains. NHE also consists of three different proteins, A, B, and C with molecular masses of 45, 39, and 105 kDa, respectively (19). Granum et al. (9) sequenced the three genes nheA, nheB, and nheC. A commercial immunoassay (Tecra visual immunoassay [VIA]; Bioenterprises Pty. Ltd., Roseville, New South Wales, Australia) for identification of enterotoxic strains of B. cereus detects the 45-kDa protein of this complex (18). The bceT gene, encoding bc-D-ENT, was cloned and sequenced from B. cereus B4-ac by Agata et al. (2). They found by PCR that this gene was present in all 10 B. cereus strains studied, including 4 strains isolated from patients with food-borne diarrheal syndrome. Ombui et al. (23) detected the gene by PCR in 41% of their strains, Hsieh et al. (15) found it in 49% of their strains, and Mäntynen and Lindström (20) could not detect the gene in any of their strains.

B. thuringiensis has recently been reported to be involved in outbreaks of gastrointestinal diseases (16, 21), and some B. thuringiensis strains have been reported to produce enterotoxins by a number of different techniques (1, 4–7, 24). Further, some B. thuringiensis strains have been reported to possess genes known to be involved in B. cereus pathogenesis (12, 15, 20, 25).

The objectives of this study were to (i) detect bceT, the hblA, hblC, and hblD genes of the HBL complex, and the nheA, nheB, and nheC genes of the NHE complex in B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains by PCR-based techniques and (ii) examine whether these genes are found in association with each other.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The 22 B. cereus and 41 B. thuringiensis strains analyzed in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. For DNA preparation, bacteria were plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (27) and incubated overnight at 30°C. An amount of bacteria corresponding to a colony 1 to 2 mm in diameter was transferred to 200 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer. Bacteria were lysed by incubation at 102°C for 10 min, and debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 3 min. The DNA-containing supernatant was transferred to a new Microfuge tube and stored at 4°C. Primers for detection of bceT and the genes of the HBL and NHE complexes are given in Table 3. PCR was performed essentially as described elsewhere (11). One microliter of DNA extract was amplified with 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in a 25-μl reaction mixture using 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 55°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. PCR products were analyzed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, using MW VI (Boehringer) as a molecular weight marker. Throughout the investigation, PCR analysis of the 16S-23S rRNA gene (rDNA) spacer region with the L1-G1 primer set (17) was used as a control of DNA quality and the procedure.

TABLE 1.

Results from PCR, Southern, and Tecra VIA immunological analyses of B. cereus isolates

| B. cereus strainc | HBL complexa

|

NHE complexa

|

Tecra kitb |

bceTa

|

Southern blotting | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hblA | hblC | hblD | nheA | nheB | nheC | 1+3d | 1+4 | 2+3 | 2+4 | 5+6 | |||

| ATCC 10987 | − | − | − | + | + | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| AH 127 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ATCC 10876 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| ATCC 11778 | − | − | − | + | + | + | +++ | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| ATCC 14579T | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| AH 184 | + | + | − | + | + | − | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| AH 185 | + | + | + | + | − | + | +++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| F 4810/72 | − | − | − | + | + | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| F 837/76 | + | + | + | − | + | − | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| F 2038/78 | − | + | − | + | + | − | ++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| ATCC 6464 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| ATCC 4342 | + | + | + | + | − | − | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ATCC 7004 | − | − | − | + | + | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ATCC 7064 | + | + | + | − | − | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ATCC 21281 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ATCC 21282 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ATCC 27348 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| ATCC 33018 | − | − | − | + | − | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| T01 176:C2 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| F 4433/73 | − | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| F 4094/73 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| F 3502/73 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

+, a PCR product of the expected size was seen; −, no PCR product was formed, or the size of the product deviated significantly from the expected size.

+, OD414 < 0.75; ++, 0.75 ≤ OD414 < 1.5; +++, OD414 ≥ 1.5.

Source of strains: ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; AH: A.-B. Kolstø, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; F, Central Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom; T01 176:C2, The Pasteur Institute, Paris, France.

Primer set.

TABLE 2.

Results from PCR, Southern, and Tecra VIA immunological analyses of B. thuringiensis isolates

| Strainc | HBL complexa

|

NHE complexa

|

Tecra kitb |

bceT

|

Southern blotting | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hblA | hblC | hblD | nheA | nheB | nheC | 1+3e | 1+4 | 2+3 | 2+4 | 5+6 | |||

| B.t. finitimus HD 3 | + | + | + | − | + | + | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B.t. alesti HD4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. kurstaki HD 1d | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| B.t. kurstaki HD 73 | − | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| B.t. kurstaki HD 263 | + | + | + | − | + | + | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. dendrolimus HD 7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. dendrolimus HD 106 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. sotto HD 770 | − | + | + | + | − | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B.t. galleriae HD 29 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| B.t. galleriae HD 234 | − | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. canadensis HD 224 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| B.t. entomocidus HD 9 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. entomocidus HD 110 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. entomocidus HD 198 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. morrisoni HD 12 | + | − | + | + | + | − | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. ostriniae HD 501 | − | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B.t. tolworthi HD 537 | + | + | + | − | + | + | +++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. tolworthi HD 125 | + | + | + | − | + | + | +++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. darmstadiensis HD 146 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. darmstadiensis HD 601 | − | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. toumanoffi HD 201 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. kyushuensis HD 541 | − | + | − | + | + | − | ++ | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| B.t. thompsoni HD 542 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. pakistani HD 395 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| B.t. indiana HD 521 | − | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| B.t. dakota HD 932 | − | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| B.t. tohokuensis HD 866 | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B.t. kuamotoensis HD 867 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. tochigiensis HD 868 | − | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B.t. colmeri HD 847 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| B.t. shandogiensis HD 1012 | + | + | − | + | + | − | ++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. thuringiensis HD 22 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B.t. aizawai HD 131 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. aizawai HD 137 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. aizawai HD 11 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. aizawai HD 112 | − | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| B.t. aizawai HD 283 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. kenyae HD 136 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| B.t. israelensis HD 567d | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. israelensis 4Q2-72 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| B.t. israelensis Bta2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+, a PCR product of the expected size was seen; −, no PCR product was formed, or the size of the product deviated significantly from expected size.

+, OD414 < 0.75; ++, 0.75 ≤ OD414 < 1.5; +++, OD414 ≥ 1.5.

Sources of B. thuringiensis subspecies (B.t.) strains: HD, U.S. Department of Agriculture; B.t. israelensis 4Q2-72 and Bta2, The Pasteur Institute, Paris, France.

Strain in use as a microbiological pesticide.

Primer set.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide sequences and locations of PCR primers

| Primer name: sequence (5′→3′) | Primer positionb | Origin of DNA sequence | Reference | Accession no.c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S-23S rDNA spacer | 17 | |||

| G1: GAAGTCGTAACAAGGa | ||||

| L1: CAAGGCATCCACCGTa | ||||

| Diarrheal enterotoxin (bceT) | B. cereus B-4ac | 2 | D17312 | |

| BCET1: CGTATCGGTCGTTCACTCGG | 1191–1210 → | |||

| BCET2: AGCTTGGAGCGGAGCAGACT | 1418–1437 → | |||

| BCET3: GTTGATTTTCCGTAGCCTGGG | 1852–1832 ← | |||

| BCET4: TTTCTTTCCCGCTTGCCTTT | 2115–2096 ← | |||

| BCET5: TTACATTACCAGGACGTGCTTa | ||||

| BCET6: TGTTTGTGATTGTAATTCAGGa | ||||

| B component (hblA) of hemolysin BL | B. cereus F837/76 | 13 | L20441 | |

| HBLA1: GTGCAGATGTTGATGCCGAT | 671–690 → | |||

| HBLA2: ATGCCACTGCGTGGACATAT | 990–971 ← | |||

| L1 component (hblD) of hemolysin BL | B. cereus F837/76 | 26 | U63928 | |

| L1A: AATCAAGAGCTGTCACGAAT | 2854–2873 → | |||

| L1B: CACCAATTGACCATGCTAAT | 3283–3264 ← | |||

| L2 component (hblC) of hemolysin BL | B. cereus F837/76 | 26 | U63928 | |

| L2A: AATGGTCATCGGAACTCTAT | 1448–1467 → | |||

| L2B: CTCGCTGTTCTGCTGTTAAT | 2197–2178 ← | |||

| A component (nheA) of nonhemolytic enterotoxin | B. cereus 1230–88 | 9 | Y19005 | |

| nheA 344 S: TACGCTAAGGAGGGGCA | 344–360 → 843–823 ← | |||

| nheA 843 A: GTTTTTATTGCTTCATCGGCT | ||||

| B component (nheB) of nonhemolytic enterotoxin | B. cereus 1230–88 | 9 | Y19005 | |

| nheB 1500 S: CTATCAGCACTTATGGCAG | 1500–1518 → 2269–2253 ← | |||

| nheB 2269 A: ACTCCTAGCGGTGTTCC | ||||

| C component (nheC) of nonhemolytic enterotoxin | B. cereus 1230–88 | 9 | Y19005 | |

| nheC 2820 S: CGGTAGTGATTGCTGGG | 2820–2836 → | |||

| nheC 3401 A: CAGCATTCGTACTTGCCAA | 3401–3383 ← |

Deduced in the referenced study.

→, upper-strand sequence; ←, lower-strand sequence. Positions are given only for primers deduced in this study, according to the sequence.

EMBL/GenBank accession number of the sequence from which the primer was deduced.

DNA for Southern analysis was digested by EcoRI and was prepared from liquid cultures in LB. Harvested cells were lysed by treatment with lysozyme (10 mg/ml) and mutanolysin (0.5 U/ml) at 37°C for 2 h. DNA was purified using a High Pure PCR template preparation kit (Boehringer). Southern hybridization for detection of bceT in EcoRI-digested total DNA was performed as described by Hansen et al. (11), using a digoxigenin-labelled BCET1-BCET3 PCR fragment as the probe.

Detection of the 45-kDa protein of the NHE complex was performed by Bacillus diarrhea enterotoxin VIA (Tecra VIA; Bioenterprises). Bacteria were cultivated in LB for 16 h at room temperature at 250 rpm. After centrifugation, supernatants were sterile filtered and stored at −80°C until the assays were performed as specified in the instruction manual. The relative amount of the 45-kDa protein was estimated by measurement of optical density at 414 nm (OD414).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The three genes, hblA, hblC, and hblD, encoding the enterotoxic HBL complex were all detected by PCR in 29 of the 41 B. thuringiensis strains, a significantly higher proportion than detected in the B. cereus strains, where only 11 of the 22 strains harbored the three genes. The remaining 12 B. thuringiensis strains all possessed at least one of the three genes comprising the complex, while six B. cereus strains had none (Tables 1 and 2). As the occurrence of the three genes shows significant association and the functioning of the complex depends on products from all three genes (8), it is most likely that polymorphism among the genes causes the inability to detect all genes in some strains by PCR. Mäntynen and Lindström (20) and Prüss et al. (25) found polymorphism among hblA genes. Mäntynen and Lindström (20) detected hblA in 52% of their B. cereus strains and in one B. thuringiensis strain, and they found these strains to be enterotoxin positive as revealed by the test kit from Oxoid. Likewise, Prüss et al. (25) found that 43% of the B. cereus and all eight B. thuringiensis strains possessed the hblA gene.

The three genes nheA, nheB, and nheC, encoding the nonhemolytic enterotoxin, were all detected in 33 of the 41 B. thuringiensis strains, again a significantly higher proportion than among the B. cereus strains, where only 13 of the 22 strains harbored all three genes. All B. thuringiensis strains possessed at least two of the NHE genes, while three B. cereus strains only harbored one gene and one strain lacked all three genes (Tables 1 and 2). The Tecra VIA for the 45-kDa protein encoded by nheA of the NHE complex revealed that all 63 isolates produced this protein, with more B. cereus strains than B. thuringiensis strains showing a high OD414 (> 0.75; P < 0.05) (Tables 1 and 2). Thus, according to this assay, all 63 strains are enterotoxic. Because variations in the cytotoxicity of the NHE complex seem to be due to differences in the 105-kDa component, this variation in activity detected by the assay is not related to the cytotoxicity of the entire complex (19). The nheA gene was not detected in seven strains by PCR, although all seven strains were positive in the Tecra VIA. This is most likely due to sequence differences among the nheA genes of these 7 and the other 56 strains. However, as the Tecra VIA also detects the 105-kDa protein component, although it is at least 10 times less sensitive (18), some of the signal might be due to this component.

Five different sets of primers were used for PCR-based detection of the bceT gene deduced from the B. cereus B-4ac sequence (Tables 1 and 2). Five B. cereus and 13 B. thuringiensis strains yielded PCR products with sizes corresponding to the PCR products of B. cereus B-4ac with all five sets of primers. A significantly higher number of B. cereus strains (10; 45%) than B. thuringiensis strains (6; 15%) produced no PCR products (Tables 1 and 2). PCR with the remaining 7 B. cereus and 22 B. thuringiensis strains resulted in products with two, three, or four sets of primers in seven different combinations. Southern analysis with all 63 strains confirmed these results (Tables 1 and 2), as the gene was detected in all B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains PCR positive with primer sets 1+3 and/or 1+4 and not in the strains which were PCR negative for all primer sets. These results indicate that (i) the bceT gene is widely distributed among B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains, (ii) PCR with bceT primer sets 1+3 and 1+4 unambiguously detects the gene, and (iii) the bceT gene varies in sequence among strains, as evidenced by differences in PCR detection by the different pairs of primers. Our combination of primers detected the gene in 47 of the strains, whereas primer pair 5+6, as deduced by Agata et al. (2), detected the gene in only 41 of the 63 strains (Tables 1 and 2). The inability of Mäntynen and Lindström (20) to detect the gene in any strain except B. cereus B-4ac might be due primarily to differences in the bceT gene sequence between strains in the two collections. The widespread occurrence of bceT in B. cereus is in accordance with findings of Agata et al. (2), Hsieh et al. (15), and Ombui et al. (23). The gene has been detected in only 11 B. thuringiensis strains (12, 15).

All 41 B. thuringiensis strains possess at least two genes of the NHE complex and at least one gene of the HBL complex. In addition, 85% of the strains possessed the gene for bc-D-ENT. All 22 B. cereus strains were found to possess the NHE complex by Tecra VIA but not by PCR analysis. Of the B. cereus strains, 6 lacked the three genes from the HBL operon and 10 were devoid of the gene for bc-D-ENT. The occurrence of the three genes in the HBL or NHE operon is significantly associated (P > 0.05), while neither the occurrence of the two operons nor the occurrence of the bc-D-ENT gene is significantly associated in the 63 strains (P < 0.05).

The virulence of B. cereus is variable among strains (8). The data presented here suggest that important determinants for this variation are the number of different enterotoxins produced by the specific strain and differences within the enterotoxins, as evidenced by the occurrence of sequence variation in the bceT and hblA genes (20). The virulence of B. thuringiensis strains is unknown, but the widespread occurrence of genes, which seem to vary in sequence, encoding NHE complex, HBL complex, and bc-D-Ent in B. thuringiensis strains suggests that virulence varies among strains and that virulent B. thuringiensis strains causing diarrhea exist. We suggest an approach for detecting potential enterotoxic strains of B. cereus and B. thuringiensis consisting of PCR analysis with primers BCET1, BCET3, and BCET4, for the detection of bceT and the six primer sets for the detection of genes in the HBL and NHE operons. An alternative is the detection of the genes by Southern analysis.

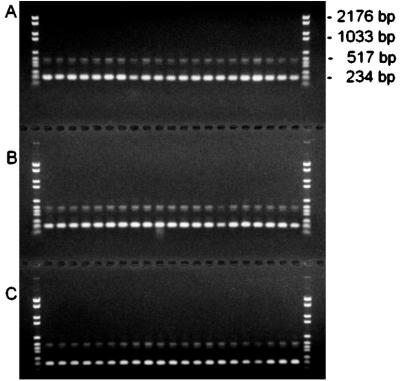

PCR analysis of the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region revealed identical patterns for all 63 strains (Fig. 1). This pattern is identical to the pattern observed for a few B. cereus, B. thuringiensis, and B. anthracis strains by Wunschel et al. (28). The 16S-23S rDNA spacer region is a very valuable tool for PCR-based typing and identification of bacteria (10, 17), and so this rDNA spacer uniformity is an additional argument for considering B. cereus and B. thuringiensis to represent one taxonomic unit, as recently proposed by others (14).

FIG. 1.

PCR analysis of the 16S-23S rDNA internal transcribed spacer of the 63 B. thuringiensis and B. cereus isolates. (A) B. thuringiensis strains from subspecies finitimus HD 3 to subspecies toumanoffi HD 201 (Table 2); (B) B. thuringiensis strains from subspecies kyushuensis HD 541 to subspecies israelensis Bta2 and B. cereus ATCC 10987 (Tables 2 and 1); (C) B. cereus strains from AH 127 to F3502/73 (Table 1).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Tina Thane for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Hameed A, Landén R. Studies on Bacillus thuringiensis strains isolated from Swedish soils: insect toxicity and production of B. cereus-diarrhoeal-type enterotoxin. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;10:406–409. doi: 10.1007/BF00144461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agata N, Ohta M, Arakawa Y, Mori M. The bceT gene of Bacillus cereus encodes an enterotoxic protein. Microbiology. 1995;141:983–988. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-4-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beecher D J, Shoeni J L, Wong A C L. Enterotoxin activity of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4423–4428. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4423-4428.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanan R L, Schultz F J. Comparison of the Tecra VIA kit, Oxoid BCET-RPLA kit, and CHA cell culture assay for the detection of Bacillus cereus diarrhoeal enterotoxin. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;19:353–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1994.tb00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson C R, Caugant D A, Kolstø A B. Genotypic diversity among Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1719–1725. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.1719-1725.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damgaard P H, Larsen H D, Hansen B M, Bresciani J, Jørgensen K. Enterotoxin-producing strains of Bacillus thuringiensis isolated from food. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;23:146–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damgaard P H, Granum P E, Bresciani J, Torregrossa M V, Eilenberg J, Valentino L. Characterization of Bacillus thuringiensis isolated from infections in burn wounds. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;18:47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granum P E. Bacillus cereus. In: Doyle M P, Beuchat L R, Montville T J, editors. Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1997. pp. 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Granum P E, O'Sullivan K, Lund T. The sequence of the non-hemolytic enterotoxin operon from Bacillus cereus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:225–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gürtler V, Stanisich V A. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology. 1996;142:3–16. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen B M, Damgaard P H, Eilenberg J, Pedersen J C. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Bacillus thuringiensis isolated from leaves and insects. J Invertebr Pathol. 1998;71:106–114. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1997.4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen B M, Hendriksen N B. Bacillus thuringiensis and B. cereus toxins. IOBC Bull. 1998;21:221–224. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinrichs J H, Beecher D J, Macmillan J D, Zilinskas B A. Molecular cloning and characterization of the hblA gene encoding the B component of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6760–6766. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6760-6766.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendriksen N B, Hansen B M. Phylogenetic relations of Bacillus thuringiensis: implications for risks associated to its use as a microbiological pest control agent. IOBC Bull. 1998;21:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh Y M, Sheu S J, Chen Y L, Tsen H Y. Enterotoxigenic profiles and polymerase chain reaction detection of Bacillus cereus group cells and B. cereus strains from foods and food-borne outbreaks. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:481–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson S G, Goodbrand R B, Ahmed R, Kasatiya S. Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis isolated in a gastroenteritis outbreak investigation. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;21:103–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen M A, Webster J A, Straus N. Rapid identification of bacteria on the basis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified ribosomal DNA spacer polymorphisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:945–952. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.945-952.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lund T, Granum P E. Characterization of a non-haemolytic enterotoxin complex from Bacillus cereus isolated after a foodborne outbreak. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;141:151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund T, Granum P E. Comparison of biological effect of the two different enterotoxin complexes isolated from three different strains of Bacillus cereus. Microbiology. 1997;143:3329–3336. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-10-3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mäntynen V, Lindström K. A rapid PCR-based DNA test for enterotoxic Bacillus cereus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1634–1639. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1634-1639.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noguchi H. Development of Bacillus thuringiensis in Japan. In: Kim L, editor. Advanced engineered pesticides. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1993. pp. 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Notermans S, Batt C A. A risk assessment approach for food-borne Bacillus cereus and its toxins. J Appl Microbiol Symp Suppl. 1998;84:51S–61S. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.0840s151s.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ombui J N, Schmieger H, Kagiko M M, Arimi S M. Bacillus cereus may produce two or more diarrheal enterotoxins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;149:245–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perani M, Bishop A H, Vaid A. Prevalence of β-exotoxin, diarrhoeal toxin and specific δ-endotoxin in natural isolates of Bacillus thuringiensis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;160:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prüss B M, Dietrich R, Nibler B, Märtlbauer E, Scherer S. The hemolytic enterotoxin HBL is broadly distributed among species of the Bacillus cereus group. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5436–5442. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5436-5442.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan P A, Macmillan J D, Zilinskas B A. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genes encoding the L1 and L2 components of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2551–2556. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2551-2556.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis A. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory. 2nd ed. N. Y: Cold Spring Harbor; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wunschel D, Fox K F, Black G E, Fox A. Discrimination among the B. cereus group, in comparison to B. subtilis, by structural carbohydrate profiles and ribosomal RNA spacer region PCR. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1994;17:625–635. [Google Scholar]