Abstract

Background

A phase 3 study to assess the efficacy and safety of the desidustat, an oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor, against the epoetin alfa for the treatment of anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) with dialysis dependency.

Methods

DREAM-D was a phase 3, multicenter, open-label, randomized, active-controlled clinical study conducted across 38 centers in India. A total of 392 patients with clinical diagnosis of anemia due to CKD with dialysis need (Erythrocyte Stimulating Agent [ESA] naïve or prior ESA users) and with baseline hemoglobin levels of 8.0–11.0 g/dL (inclusive) were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either desidustat oral tablets (thrice a week) or epoetin alfa subcutaneous injection for 24 weeks to maintain a hemoglobin level of 10–12 g/dL. The primary endpoint was to assess the change in the hemoglobin level between the desidustat and the epoetin alfa groups from the baseline to evaluation period week 16–24. The key secondary efficacy endpoint was the number of patients with hemoglobin response.

Results

The least square mean (standard error) change in hemoglobin from the baseline to week 16–24 was 0.95 (0.09) g/dL in the desidustat group and 0.80 (0.09) g/dL in the epoetin alfa group (difference: 0.14 [0.14] g/dL; 95% confidence interval: −0.1304, 0.4202), which met the prespecified noninferiority margin. The number of hemoglobin responders was significantly higher in the desidustat group (106 [59.22%]) when compared to the epoetin alfa group (89 [48.37%]) (p = 0.0382). The safety profile of the desidustat oral tablet was comparable with the epoetin alfa injection. There were no new risks or no increased risks seen with the use of desidustat compared to epoetin alfa.

Conclusion

In this study, desidustat was found to be noninferior to epoetin in the treatment of anemia in CKD patients on dialysis and it was well-tolerated.

Clinical Trial Registry Identifier

CTRI/2019/12/022312 (India).

Keywords: Anemia, Chronic kidney disease, Dialysis, Hypoxia-inducible factor, Hemoglobin, Hepcidin

Introduction

Anemia is a common complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1, 2]. It is associated with significant morbidity, mortality, progression of kidney disease in patients with diabetes, and higher transfusion rates in the CKD population [3, 4, 5]. Anemia may result from several causes, including factors that shorten red cell life span, functional iron deficiency, diminished erythropoietin (EPO) production, and resistance to EPO signaling [6, 7, 8]. The prevalence and severity of anemia are higher at later stages of CKD with >90% prevalence in stage 5 CKD [9]. Anemia can further worsen due to dialysis-related blood loss, infection, functional hemolysis, etc. [10].

In CKD, inflammation and impaired renal clearance result in an increased plasma hepcidin level, which leads to inhibition of duodenal iron absorption and sequestration of iron in macrophages. These effects of hepcidin can cause functional iron deficiency, decreased availability of iron for erythropoiesis, and resistance to endogenous and exogenous EPO [11]. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is an important transcription factor in the regulation of erythropoiesis, iron metabolism, and multiple other processes involved in the maintenance of homeostasis [12, 13, 14, 15]. HIF, a key mediator of cellular adaptation to oxygen deprivation, comprises an oxygen-sensitive α-subunit and a stable β-subunit. Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-α is stabilized and after nuclear translocation, it dimerizes with the HIF-β subunit, forming heterodimers that activate multiple genes, including EPO and other genes involved in iron metabolism. Prolyl hydroxylase domain has negative regulatory control on HIF. Therefore, the compounds that exert inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase domain activate HIF signaling and may represent effective treatments of anemia in CKD. Moreover, EPO-induced erythropoiesis stimulated by HIF-PHI inhibits hepcidin synthesis in the liver and reduces serum hepcidin levels [16].

In one of the studies, it was observed that HIF-PHI reduced mean low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in all patients regardless of whether they were taking statins [17]. This effect may be beneficial as patients with CKD are more likely to die from cardiovascular events than from kidney failure.

Hypoxia-inducible factor inhibition is also associated with upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) genes. Since transcription of the VEGF gene is regulated by HIF-1a and HIF-2a binding to hypoxia response elements, there is a clear theoretical concern that HIF stabilization will increase the risk for neoplasia and diabetic retinopathy, resulting in poor outcomes [18].

Desidustat, an oral HIF-PHI developed by Cadila Healthcare Limited for the treatment of anemia due to CKD, was found to be well-tolerated in single and multiple doses up to a 300 mg dose in the phase 1 study [19]. Desidustat was also found to be effective, safe, and tolerable up to 200 mg in patients with anemia in CKD in the phase 2 study [20]. Therefore, Cadila Healthcare Limited conducted a randomized phase 3 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of desidustat against epoetin alfa in the treatment of anemia due to CKD with a need of dialysis.

Methods

Trial Oversight

This was a phase 3, multicenter, open-label, randomized, active-controlled clinical study to evaluate the efficacy and the safety of desidustat tablet versus biosimilar epoetin alfa injection (Zyrop, Cadila Healthcare Limited) in the treatment of anemia in patients with CKD who were on dialysis. The study was designed and overseen by Cadila Healthcare Limited. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee at study sites, and the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the guidelines laid down in ICH GCP, CDSCO, and the regulations/guidelines of the Government of India.

A data safety monitoring board was established to ensure the safety of patients enrolled in the study. The data safety monitoring board consisted of three medical experts from the relevant therapeutic area and one independent statistician. The committee reviewed the safety data periodically and recommended the continuation of the study.

Patients

Key inclusion criteria were males or females aged ≥18 years; clinical diagnosis of anemia due to CKD (stage 5) on dialysis (≥2 times in a week) for at least 12 weeks prior to screening; baseline hemoglobin level of 8.0–11.0 g/dL (inclusive); serum ferritin >200 ng/mL and/or transferrin saturation (TSAT) >20%; no iron, folate, or vitamin B12 deficiency. Both Erythrocyte Stimulating Agents (ESA) naive (patients who had not received EPO analog for at least 4 weeks or Mircera® for at least 8 weeks prior to screening visit) and prior ESA users (patients on a stable dose of ESA at least 4 weeks prior to screening) were included in the study. Key exclusion criteria were patients with red blood cell transfusion within 8 weeks prior to enrollment; history of previous or concurrent cancer; history of renal transplant; patients having received ESA at high doses at screening; history of bleeding disorders. A complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in the online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000523949). All the patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Trial Procedures

The study patients were randomly assigned in 1:1 ratio to receive either the desidustat oral tablet or the epoetin alfa subcutaneous injection. The randomization schedule, to ensure the treatment balance, was generated using SAS® software. No stratification was used in the randomization. For ESA naïve patients, the initial dose of desidustat was 100 mg thrice a week and that of epoetin alfa was 50 IU/kg (Zyrop®, Cadila Healthcare Limited) thrice a week. For ESA users, the initial dose of desidustat (100 mg/125 mg/150 mg) and epoetin alfa was determined based on the dose of prior ESA therapy. The detailed information on dose calculation is provided in the online supplementary material. The IP was administered after dialysis on dialysis days. For those patients who reported twice a week for dialysis, the third dose was administered 48 h after the second dose. The treatment duration was 24 weeks followed by a safety follow-up 2 weeks after the end of the treatment. An Interactive Web Response System was used for the selection of doses during the study on the basis of hemoglobin level. Dose adjustment was permitted from weeks 4 to 20 on the basis of changes in the hemoglobin levels assessed by HemoCue. Further information on dose adjustment is provided in the online supplementary material.

To maintain adequate iron status, the iron supplementation (oral or parenteral) was allowed based on assessment of the iron profile (serum ferritin, serum iron, and TSAT) as specified in the protocol. Rescue medication (e.g., ESA and red blood cell transfusion) was reserved for the patients whose hemoglobin level dropped below 7 g/dL or decreased by ≥2 g/dL from the baseline as per the concerned investigator's discretion.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was a change in hemoglobin from the baseline to evaluation period of weeks 16–24. The secondary outcomes included a number of hemoglobin responders, time to achieve target range hemoglobin level of 10–12 g/dL, percentage of time spent in target hemoglobin range, change in serum hepcidin, change in serum potassium level, change in quality of life score as per SF-36, number (%) of patients on rescue therapy, change in VEGF, and change in lipid and lipoprotein profile.

Statistical Analyses

At least 163 patients in each of the two treatment groups were required to show noninferiority of desidustat to epoetin alfa at 85% power with a one-sided 0.025 level of significance, and a noninferiority margin of −1 g/dL. Considering a dropout rate of 20%, at least 392 patients were to be enrolled with an allocation ratio of 1:1.

The change in hemoglobin from the baseline at weeks 16–24 between the treatments was evaluated using the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with treatment as a fixed effect and baseline value as a covariate. The two treatment groups were compared using difference in least square mean and p value from the ANCOVA model. Noninferiority was established if the lower limit of the two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the treatment difference (desidustat − epoetin alfa) was above −1 g/dL.

The secondary efficacy endpoints of the number of hemoglobin responders and the number of patients requiring rescue medication were analyzed using the χ2/Fisher exact test. The quantitative secondary endpoints of change in hepcidin, potassium, and VEGF were analyzed similar to the primary endpoint using ANCOVA. For “time to achieve target range” the first occurrence of incidence was taken into consideration. Time to achieve the target range and percentage of time spent in the target hemoglobin range were analyzed using the Wilcoxon test.

All the randomized patients who received study medication and appeared for at least one postbaseline visit were included in the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population for the efficacy analysis using the last observation carried forward imputation method for postbaseline missing values. All the primary and secondary efficacy endpoints were analyzed using the mITT population. The per-protocol (PP) population was considered for supportive analyses. The PP population was defined as all the enrolled patients who met the eligibility criteria, completed the study in compliance with the protocol, and had no major protocol deviation.

Results

Characteristics of Patients

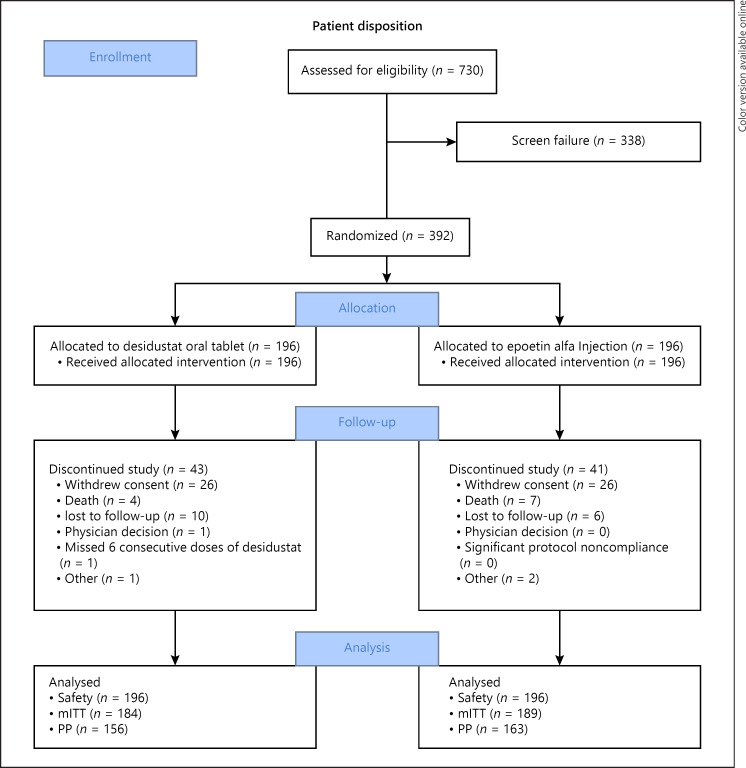

From January 04, 2020, to January 29, 2021, a total of 392 patients were randomly assigned in 1:1 ratio to receive desidustat or epoetin alfa at 38 centers in India. Patient disposition is provided in Figure 1. In total, 308 patients completed the study: 153 patients in the desidustat group and 155 patients in the epoetin alfa group. Out of 392 patients, 24 patients in the desidustat group and 26 patients in the epoetin alfa group were ESA naive at the time of enrollment. Overall, the two groups were well-balanced with respect to baseline characteristics (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics (safety analysis population)

| Statistics | Desidustat oral tablet (N = 196) | Epoetin alfa injection (N = 196) | Overall (N = 392) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | Mean ± SD | 51.02±13.97 | 50.91±13.48 | 50.96±13.71 |

| Median (min, max) | 52.50 (18.00, 77.00) | 52.00 (21.00, 91.00) | 52.00 (18.00, 91.00) | |

| Gender, n (%) | Female | 61 (31.12) | 62 (31.63) | 123 (31.38) |

| Male | 135 (68.88) | 134 (68.37) | 269 (68.62) | |

| Race, n (%) | Asian | 196 (100.0) | 196 (100.0) | 392 (100.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | South Asian | 196 (100.0) | 196 (100.0) | 392 (100.0) |

| Weight, kg | Mean ± SD | 58.93±13.37 | 60.82±13.36 | 59.87±13.38 |

| Median (min, max) | 57.00 (34.00, 112.00) | 59.20 (31.10, 104.00) | 58.00 (31.10, 112.00) | |

| Height, cm | Mean ± SD | 162.02±9.87 | 162.95±8.78 | 162.49±9.34 |

| Median (min, max) | 162.00 (134.00, 192.00) | 164.00 (141.00, 188.00) | 163.00 (134.00, 192.00) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | Mean ± SD | 22.43±4.96 | 22.90±5.01 | 22.66±4.99 |

| Median (min, max) | 21.85 (11.90, 46.60) | 22.20 (14.10, 43.10) | 21.95 (11.90, 46.60) | |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | − | 71 (36.22) | 70 (35.71) | 141 (35.96) |

| Hypertension | − | 181 (92.35) | 178 (90.82) | 359 (91.58) |

| Cardiac disorders | − | 10 (5.10) | 7 (3.57) | 17 (4.34) |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | Mean ± SD | 9.61±0.99 | 9.55±1.37 | − |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | Mean ± SD | 1,209.72±1,133.85 | 1,188.53±1,170.54 | − |

| TSAT, % | Mean ± SD | 37.60±18.49 | 35.88±16.47 | − |

| CRP, mg/L | Mean ± SD | 7.88±6.76 | 7.51±6.79 | − |

| Lipids and lipoprotein, mg/dL | ||||

| LDL cholesterol | Mean ± SD | 77.41±31.66 | 80.34±32.60 | − |

| HDL cholesterol | Mean ± SD | 40.92±14.12 | 39.06±12.47 | − |

| VLDL cholesterol | Mean ± SD | 27.04±17.59 | 27.85±17.92 | − |

| Total cholesterol | Mean ± SD | 137.05±37.58 | 137.41±35.91 | − |

| Apolipoprotein-A1 | Mean ± SD | 110.37±21.62 | 109.30±18.40 | − |

| Apolipoprotein-B | Mean ± SD | 75.05±24.98 | 76.76±24.32 | − |

| Lipoprotein (a) | Mean ± SD | 38.74±38.37 | 42.79±35.70 | − |

| Triglycerides | Mean ± SD | 135.03±87.87 | 139.27±89.59 | − |

| Potassium, mmol/L | Mean ± SD | 5.21±0.94 | 5.36±1.07 | − |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic | Mean ± SD | 143.06±16.71 | 143.15±14.98 | − |

| Diastolic | Mean ± SD | 82.01±10.05 | 82.21±9.67 | − |

BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; max, maximum; min, minimum; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; N, number of subjects in the mITT population in each treatment group; n, number of subjects in each treatment group at specific visit; SD, standard deviation.

Outcomes

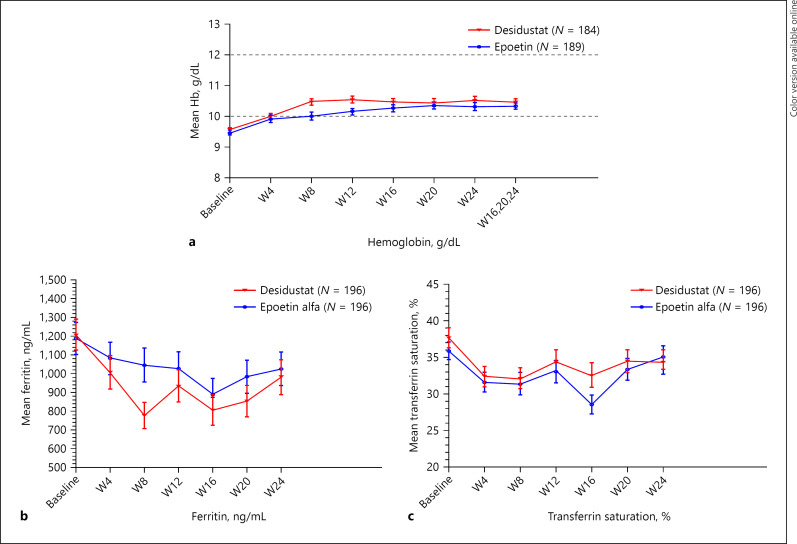

The least square mean (SE) change in hemoglobin from baseline to weeks 16–24 was 0.95 (0.09) g/dL in the desidustat group and 0.80 (0.09) g/dL in the epoetin alfa group (difference: 0.14 [0.14] g/dL; 95% CI: −0.1304, 0.4202), which met the prespecified noninferiority margin. Similar results were seen in supportive analysis in the PP population (difference: 0.19 [0.15] g/dL; 95% CI: −0.1058, 0.4936). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) hemoglobin level at weeks 16–24 was 10.47 (1.37) g/dL in the desidustat group and 10.32 (1.41) g/dL in the epoetin alfa group. A plot of hemoglobin values over time for both the treatment groups is presented in Figure 2a.

Fig. 2.

a Summary of hemoglobin levels over time (mITT population). b, c Summary of serum ferritin and TSAT levels over time (safety population).

These values were within the prespecified reference range of 10–12 g/dL. During the study, 77 patients in the desidustat group and 70 patients in the epoetin alfa group overshot a Hb level above 12 g/dL. The mean (SD) iron parameters (serum iron, serum ferritin, and TSAT) were comparable in both the treatment groups at the baseline. The postbaseline use of iron supplement was as per the iron parameters assessment. The summary plots of serum ferritin and TSAT are presented in Figure 2b and c, respectively.

The number of hemoglobin responders (defined as achievement of a target level of 10–12 g/dL [average of weeks 16, 20, and 24] and posttreatment increase of 1 g/dL or more in hemoglobin by week 24) were significantly higher in the desidustat group (106 [59.22%]) when compared to the epoetin alfa group (89 [48.37%]) (p = 0.0382). The median time to achieve hemoglobin in the target range was significantly less in the desidustat group compared to the epoetin alfa group (4 weeks in the desidustat group vs. 8 weeks in the epoetin group, p = 0.0417). The median percentage of time spent in the target hemoglobin range up to week 24 was statistically significantly higher in the desidustat group (83.33%) compared to the epoetin alfa group (66.67%) (p = 0.0489). No patients required rescue medication in the study. However, 1 patient in the desidustat group who had a serious adverse event (SAE) of lower respiratory tract infection and hemoglobin drop of 2 g/dL was given an epoetin alfa injection to maintain the hemoglobin level.

The mean (SD) change from the baseline in hepcidin to weeks 12 and 24 was −15.6 ± 103.3 and −36.6 ± 94.04 ng/mL, respectively, in the desidustat group and −16.6 ± 94.93 and −19.2 ± 148.1 ng/mL, respectively, in the epoetin alfa group. The difference of change in hepcidin from baseline to week 12 and 24 between the two treatment groups was not statistically significant (p value >0.05). The difference of change from baseline to week 12 between the two treatment groups was statistically significant for apolipoprotein-B (p value <0.0001), total cholesterol (p = 0.0003), and LDL cholesterol (p = 0.0010). The difference of change from baseline to week 24 was statistically significant (p = 0.0088) for lipoprotein (a). The use of lipid-lowering agents was comparable between the two treatment groups at baseline (41 in the desidustat group and 50 in the epoetin alfa group).

The quality of life score improved significantly at week 12 as well as at week 24 in both the treatment groups when compared to the baseline score, and there was no significant difference observed between the treatment groups in the change from the baseline to week 12 or 24. The difference of change in VEGF and change in potassium from the baseline to week 12 or 24 was not statistically significant between the treatment groups.

The results of secondary efficacy endpoints in the mITT population are shown in Online Supplementary Tables 2-4. Similar results were seen in the supportive analyses for all the efficacy endpoints except for “median time to achieve target hemoglobin range.” There was no difference observed between the treatment groups in “median time to achieve hemoglobin in target range” in the PP population.

Safety

Overall, no noticeable difference was observed in the occurrences of adverse events (AEs) between the two treatment groups. A total of 373 AEs were reported during the study: 196 AEs in the desidustat group and 177 AEs in the epoetin alfa group. The majority of AEs were mild, unrelated, and resolved without any action with the investigational product in both the treatment groups. A total of 94 (47.96%) patients reported at least one TEAE in the desidustat group, and 91 (46.43%) patients reported at least one TEAE in the epoetin alfa group. The most frequently reported TEAEs (reported in ≥2% of patients in either treatment group) are shown in Table 2. Among the enrolled patients, 181 (92.35%) in the desidustat group and 178 (90.82%) in the epoetin alfa group had hypertension as a concurrent medical condition. There was no clinically significant mean (SD) change from baseline observed in sitting systolic blood pressure (desidustat: −4.80 ± 16.14; epoetin alfa: −4.55 ± 16.71) or sitting diastolic blood pressure (desidustat: −1.78 ± 10.80; epoetin alfa: −1.03 ± 10.75) in any of the treatment groups at week 26. The events of hypertension reported as TEAEs were similar in both the treatment groups (2.55%).

Table 2.

Summary of common TEAEs (≥2% either treatment group) by PT (safety population)

| Desidustat oral tablet (N = 196), n (%) | Epoetin (N = 196), n (%) | Overall (N = 392), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects with at least one TEAE, n | 94 (47.96) | 91 (46.43) | 185 (47.19) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (2.04) | 5 (2.55) | 9 (2.30) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 1 (0.51) | 4 (2.04) | 5 (1.28) |

| Nausea | 7 (3.57) | 3 (1.53) | 10 (2.55) |

| Vomiting | 8 (4.08) | 7 (3.57) | 15 (3.83) |

| Asthenia | 8 (4.08) | 7 (3.57) | 15 (3.83) |

| Chills | 5 (2.55) | 1 (0.51) | 6 (1.53) |

| Edema | 4 (2.04) | 1 (0.51) | 5 (1.28) |

| Pyrexia | 16 (8.16) | 10 (5.10) | 26 (6.63) |

| COVID-19 | 9 (4.59) | 6 (3.06) | 15 (3.83) |

| Blood alkaline phosphatase increased | 4 (2.04) | 1 (0.51) | 5 (1.28) |

| Blood potassium increased | 7 (3.57) | 4 (2.04) | 11 (2.81) |

| Hyperkalemia | 5 (2.55) | 1 (0.51) | 6 (1.53) |

| Muscle spasms | 1 (0.51) | 4 (2.04) | 5 (1.28) |

| Headache | 7 (3.57) | 9 (4.59) | 16 (4.08) |

| Cough | 3 (1.53) | 4 (2.04) | 7 (1.79) |

| Dyspnea | 5 (2.55) | 9 (4.59) | 14 (3.57) |

| Hypertension | 5 (2.55) | 5 (2.55) | 10 (2.55) |

If a subject had multiple occurrences of TEAE, the subject was presented only once for the corresponding TEAE. N, number of subjects in the safety population in each treatment group which was used as the denominator to calculate percentages; n, number of subjects in each treatment group in a specific category.

The occurrence of SAEs was low in the desidustat group (16 [8.16%]) compared to the epoetin alfa group (21 [10.71%]). The most frequently reported system organ class was infection and infestation: 8 (4.08%) patients in the desidustat group and 7 (3.57%) patients in the epoetin alfa group (online suppl. Table 6). No SAE was considered causally related to any of the treatment groups. There were 4 deaths reported in the desidustat group and 7 deaths in the epoetin alfa group. All death events were considered not related to the study treatments. Blood pressure, oral temperature, pulse rate, and respiratory rate did not change significantly in any treatment groups. All the ECG results and 2D-ECHO results were not clinically significant. There was no trend observed in the safety laboratory parameters during the study that could affect the safety of the patients.

Discussion/Conclusion

This 24-week, phase 3 study demonstrated noninferiority of the desidustat oral tablet compared to the epoetin alfa injection in the treatment of anemia in patients with CKD undergoing dialysis. The effect of desidustat in increasing the hemoglobin levels was comparable to epoetin alfa. In this study, the hemoglobin levels started rising from week 4 and remained in the prespecified range of 10–12 g/dL throughout the study in both the treatment groups. Moreover, the percentage of hemoglobin responders was significantly higher in the desidustat group compared to the epoetin alfa group. The current study also showed that desidustat maintained the target hemoglobin level (10–12 g/dL) for a longer period of time compared to epoetin alfa. Desidustat was also comparable to epoetin alfa in improving the quality of life of patients in the study.

The efficacy results seen in the current study were in line with the results of our phase 2 study [19]. The change from baseline in hemoglobin to week 24 seen in the current study was consistent with the findings from our previous phase 2 study for the treatment duration of 6 weeks (0.96 ± 1.74 in phase 3 study and 1.57 ± 1.07 in phase 2 study) [20]. The efficacy results in terms of changes in the hemoglobin levels over time in the current study were consistent with those of another PHI-HIF (roxadustat) in the treatment of anemia for patients with CKD on dialysis [21].

There was no difference observed between desidustat and epoetin alfa for their effect on hepcidin, VEGF, and potassium levels. The decrease in levels of apolipoprotein-B, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol was significant in the desidustat group at week 12 when compared to the epoetin alfa group. The decrease in levels of lipoprotein (a) was significant in the desidustat group at week 24 compared to the epoetin alfa group. However, to prove the clinical significant benefits on lipids with desidustat, an independent study may be required. During the study, the VEGF level was measured till week 24 in both the treatment groups, and the changes in VEGF levels were found to be nonsignificant. The decreasing trend from baseline in levels of hepcidin and LDL seen in the current study was consistent with the findings from the phase 2 study [20] and with that of another PHI-HIF (roxadustat) in the treatment of anemia for a patient with CKD on dialysis [21].

The safety profile of the desidustat oral tablet was comparable with the epoetin alfa injection. There were no new risks or no increased risks seen with the use of desidustat compared to epoetin alfa. The incidence of SAEs was 16 (8.16%) in the desidustat group and 21 (10.71%) in the epoetin alfa group; however, none of the SAEs was considered to be related to the study treatments. Of the 11 deaths reported in the study (4 in desidustat and 7 in epoetin alfa group), none was considered related to the study treatments. The fatal events reported in the study included: COVID-19 (2 events); severe pneumonia with sepsis; type II respiratory failure; acute end-stage CKD on maintenance dialysis; hypertension; chronic anemia; end-stage renal disease; hypoxic brain injury; acute myocardial infarction, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation; and unknown reason. There were no clinically significant changes in the vitals, safety laboratory parameters, ECG, or 2D-ECHO in the current study. The safety results demonstrated that desidustat was generally well-tolerated and that the safety results were consistent with our phase 2 study results [20]. The limitations of the current study included the fact that the study was open-label as the routes of administration for both the treatments were different, lack of racial or ethnic diversity, and the follow-up for 2 weeks after end of treatment duration of 24 weeks. Strengths of this study include its multicenter, randomized, active comparator-controlled design, and its power to assess noninferiority of desidustat to epoetin alfa. In this study, desidustat was found to be noninferior to epoetin in the treatment of anemia in CKD patients on dialysis and it was well-tolerated.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants before enrollment. The trial was initiated only after obtaining the approvals of the Ethics Committee and regulatory authority of India (DCGI). The trial was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonization guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and any other applicable local regulations.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. Kevinkumar Kansagra, Dr. Pooja Kanani, Dr. Jayesh Bhatt, and Kuldipsinh Zala are employees of Cadila Healthcare Limited. All other authors declared to have no conflict of interest. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

Funding Sources

Phase 3 clinical development of Desidustat was funded by Cadila Healthcare Limited.

Author Contributions

Dr. Kevinkumar Kansagra was involved in the conceptualization, design, and supervision of the conduct of the study. Dr. Sishir Gang, Dr. Prakash Khetan, Dr. Deepak Varade, Dr. Venkata Ramakrishna Chinta, Dr. Siddharth Mavani, Dr. Umesh Gupta, Dr. S. Venkata Krishna Reddy, Dr. Sunil Rajanna, Dr. Tarun Jeloka, Dr. Vivek Ruhela, and the members of the Study Investigator Group (i.e., Dr. Alok Jain, Dr. Ashok Kumar Sharma, Dr. Avinash Ignatius, Dr. Chakravarthy Kolli K, Dr. Deepak Shankar Ray, Dr. Dhananjay Kumar Sinha, Dr. Dinesh Khullar, Dr. Javed Vakil, Dr. Kailas Shewale, Dr. Kamal Ramesh Goplani, Dr. Manisha Sahay, Dr. Rajan Isaacs, Dr. Rajasekara Chakravarthi Madarasu, Dr. Sanjay Srinivasa, Dr. Tejendra Singh Chauhan, Dr. Tapas Ranjan Behera, Dr. Manishkumar Mali, Dr. Govind Kasat, Dr. Sonal Shah, Dr. Aneesh Nanda, Dr. Anil Kumar B.T., Dr. Ambekar Niranjan Chintaman, Dr. Joyita Bharati, Dr. Vinay Rathore, Dr. Vinod P. Baburajan, Dr. Maddi Venkata Sai Krishna, Dr. Pravina Desai, Dr. Ravinder Singh Bhadoria, and Dr. Pinaki Mukhopadhyay) who enrolled study participants at their respective study sites. Dr. Pooja Kanani was involved in data interpretation. Dr. Jayesh Bhatt was responsible for project management. Kuldipsinh Zala was involved in manuscript writing.

Data Availability Statement

The limited data that support the findings of this study are included in the article and its supplementary material file. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Deven Parmar for his contribution in the conceptualization, design, and supervision of the conduct of the study; Purav Trivedi for clinical operation support; Jatin Patel for medical writing support; Vishal Nakrani for quality review support; Deepak Sahu for IP management support; Dr. Kalpesh Gandhi for laboratory assessment; Jay Bhavsar for statistical analysis support; and Dr. Chintan Shah, Nirav Patel, and Tech Observer for data management support. The authors would also like to acknowledge Anjali Narkhede for regulatory and QA support, Pragnesh Donga, for regulatory support; Chetan Shingala for quality assurance support; and Mukesh Ukawala for IP support. The authors would also like to acknowledge all the participants who participated in this trial (ZRC communication number: 673).

References

- 1.Collins A, Ma J, Xia A, Ebben J. Trends in anemia treatment with erythropoietin usage and patient outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32((6 Suppl 4)):S133–41. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(98)70176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens L, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298((17)):2038–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin A. The treatment of anemia in chronic kidney disease: understandings in 2006. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16((3)):267–71. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32805b7257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohanram A, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S, Lyle PA, Toto RD. The effect of losartan on hemoglobin concentration and renal outcome in diabetic nephropathy of type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2008;73:630–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawler EV, Bradbury BD, Fonda JR, Gaziano JM, Gagnon DR. Transfusion burden among patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:667–72. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06020809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vos FE, Schollum JB, Coulter CV, Doyle TC, Duffull SB, Walker RJ. Red blood cell survival in long-term dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:591–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishban S, Nissenson AR. Anemia management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2010;117:S3–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koury MJ, Haase VH. Anaemia in kidney disease: harsnessing hypoxia responses for therapy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:394–410. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen N, Qian J, Chen J, Yu X, Mei C, Hao C, et al. Phase 2 studies of oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor FG-4592 for treatment of anemia in China. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32((8)):1373–86. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsubakihara Y, Nishi S, Akiba T, Hirakata H, Iseki K, Kubota M, et al. 2008 Japanese society for dialysis therapy: guidelines for renal anemia in chronic kidney disease. Ther Apher Dial. 2010;14((3)):240–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2010.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganz T, Nemeth E. Iron balance and the role of hepcidin in chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2016;36((2)):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40((2)):294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell. 2012;148((3)):399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenger RH, Stiehl DP, Camenisch G. Integration of oxygen signaling at the consensus HRE. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re12. doi: 10.1126/stke.3062005re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai Z, Zhong H, Bosch-Marce M, Fox-Talbot K, Wang L, Wei C, et al. Complete loss of ischaemic preconditioning-induced cardioprotection in mice with partial deficiency of HIF-1 alpha. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:463–70. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haase VH. Regulation of erythropoiesis by hypoxia-inducible factors. Blood Rev. 2013;27((1)):41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyne D, Roger S, Shin S, Kim SG, Cadena AA, Moustafa MA, et al. Roxadustat for CKD-related anemia in non-dialysis patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:624–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta N, Wish JB. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors: a potential new treatment for anemia in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69((6)):815–26. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kansagra KA, Parmar D, Jani RH, Srinivas NR, Lickliter J, Patel HV, et al. Phase 1 Clinical Study of ZYAN1, a novel prolyl-hydroxylase (PHD) inhibitor to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics following oral administration in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacokinetic. 2018 Jan;57((1)):87–102. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0551-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parmar DV, Kansagra KA, Patel JC, Joshi SN, Sharma NS, Shelat AD, et al. Outcome of desidustat treatment in people with anemia and chronic kidney sisease: a phase 2 study. Am J Nephrol. 2019 May 21;49((6)):470–8. doi: 10.1159/000500232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen N, Hao C, Liu B, Lin H, Wang C, Xing C, et al. Roxudustat treatment for anemia in patients undergoing long-term dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 12;381((11)):1011–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Data Availability Statement

The limited data that support the findings of this study are included in the article and its supplementary material file. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.