Abstract

Rationale & Objective:

Patients with CKD are at elevated risk of metabolic acidosis due to impaired net acid excretion (NAE). Identifying early markers of acidosis may guide prevention in CKD. This study compared NAE in participants with and without CKD, as well as the NAE, blood pressure (BP), and metabolomic response to bicarbonate supplementation.

Study Design:

randomized-order, cross-over study with controlled feeding.

Setting & Participants:

8 patients with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate 30-59 mL/min/1.73 m2 or 60-70 mL/min/1.73 m2 with albuminuria) and 6 patients without CKD. All participants had baseline serum bicarbonate between 20-28 mEq/L, did not have diabetes mellitus, and did not use alkali supplements at baseline.

Intervention:

Participants were fed a fixed acid-load diet with bicarbonate supplementation (7 days) and with sodium chloride control (7 days) in a randomized-order, cross-over fashion.

Outcomes:

Urine NAE, 24-hour ambulatory BP, and 24-hour urine and plasma metabolomic profiles were measured after each period.

Results:

During control, mean NAE was 28.3 ± 10.2 mEq/d overall without difference across groups (p=0.5). Urine pH, ammonium, and citrate were significantly lower in CKD versus non-CKD (each p<0.05). Bicarbonate supplementation reduced NAE and urine ammonium in the CKD group; Urine pH increased in both groups, but more in patients with CKD versus non-CKD; Urine citrate increased with HCO3 in the CKD group (each p-interaction<0.2). Using metabolomics, several urine organic anions were increased with bicarbonate in CKD, including 3-indoleacetate, citrate/isocitrate, and glutarate. BP was not significantly changed.

Limitations:

small sample size and short feeding duration.

Conclusions:

Patients with, compared to without, CKD had lower acid excretion in the form of ammonium, but also lower base excretion as citrate and other organic anions, a potential compensation to preserve acid-base homeostasis. In CKD, acid excretion decreased further, but base excretion (e.g. citrate) increased in response to alkali. Urine citrate should be evaluated as an early and responsive marker of impaired acid-base homeostasis.

Funding:

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Duke O’Brien Center for Kidney Research.

Trial Registration:

Registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with study number NCT02427594.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease (CKD), metabolic acidosis, diet, hypertension, alkali, net acid excretion (NAE), bicarbonate, subclinical acidosis, human feeding study, cross-over trial, bicarbonate supplementation, acid-base homeostasis

Introduction

Metabolic acidosis is a complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD) that is associated with muscle wasting, bone disease, loss of kidney function, and increased mortality.1–4 Small interventional studies demonstrate that correcting metabolic acidosis with oral alkali supplementation, novel ‘acid exchange’ resins, or lower dietary acid load may preserve kidney function.5–8 Although metabolic acidosis is highly prevalent among patients with advanced CKD,9 animal studies suggest that patients with early CKD may have reduced pH in the renal cortex or other tissues, consistent with a state of ‘subclinical’ acidosis that is not clinically overt.10 Treating with sodium bicarbonate or diet earlier in CKD, before serum bicarbonate falls, may also protect kidney function.11,12 Currently, no routine clinical tests are available to identify patients with subclinical acidosis to guide earlier therapy, although both urine citrate and ammonium have been proposed.13–16

We hypothesized that patients with CKD and relatively preserved serum bicarbonate would be in a state of mild, subclinical acidosis compared to patients without CKD. Further, we hypothesized that the reduction in net acid excretion (NAE) after alkali supplementation would be blunted in CKD, reflecting a proclivity to restore alkali pools. With a rigorous cross-over and controlled feeding design, we compared the effect of alkali supplementation on the primary outcome of urine NAE in participants with and without CKD as a potential functional assay for subclinical acidosis. To determine hemodynamic effects related to the addition of the alkaline salt, we also tested effects on a second co-primary outcome of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure (BP). Finally, we evaluated metabolomics profiles in blood and urine as an exploratory approach aiming to preliminarily identify potential novel biomarkers of subclinical acidosis.

Methods

Study oversight

The Acid Base Compensation in CKD (ABC) study was a single site human feeding study conducted between April 2015 and July 2017. The protocol was approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02427594). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

We recruited 14 participants after completing a pre-screening phone interview and an incenter visit to confirm eligibility. After enrolling 8 participants with CKD, we then enrolled non-CKD participants that were frequency-matched for sex, race, and age within 5 years. Two participants with CKD remained unmatched at the end of enrollment.

Participants with CKD had estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] of 60-70 ml/min/1.73 m2 plus spot urinary albumin-creatinine ratio [UACR] ≥30 mg/g or eGFR of 30-59 ml/min/1.73 m2 irrespective of albuminuria. Participants without CKD had eGFR >70 ml/min/1.73 m2 plus spot UACR <30 mg/g. All participants were 22 years of age or older and had serum bicarbonate 20-28 mEq/L at screening. We excluded participants who were pregnant or breast feeding and those with serum calcium <8.6 mg/dl at screening, systolic BP (SBP) >160 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) >95 mm Hg, history of diabetes mellitus, body mass index <18.5 or >40 kg/m2, physical examination signs of volume overload at the study screening visit, intolerance to study foods, use of alkali supplements at baseline or major medical comorbidities as detailed in Item S1. Participants were asked to maintain the stable dosage of their antihypertensive medications during the study and required stable doses for ≥3 weeks before beginning the intervention.

Intervention

To minimize potential confounding by diet on NAE, BP, and metabolism, we used a rigorous feeding protocol over 17 days that was adapted from the feeding protocol used in our previous studies.17,18 All participants received an initial 3-day run-in diet to adjust daily calories and maintain a stable body weight. Immediately following the run-in period, participants were randomized to receive a 14-day cross-over intervention consisting of a 7-day control period and a 7-day alkali period in random order with no intervening washout (Figure S1). Four daily menus were designed and repeated in sequence to deliver a consistent level of total daily calories, sodium, and approximate diet-derived acid load with exact replication in each interventional period (Item S1).

During the alkali period, sodium bicarbonate was dosed initially as two 650 mg tablets daily for 3 days for all and then was escalated to four 650 mg tablets divided thrice daily (31 mEq/d) for participants with ideal body weight <70 kg, and up to five 650 mg tablets divided thrice daily (39 mEq/d) for participants with ideal body weight ≥70 kg. Sodium chloride was added to the diet as table salt during the control period at equimolar concentrations.

All study food and beverages were prepared in a metabolic kitchen at the Duke Stedman Nutrition & Metabolism Center. During weekdays, participants consumed dinner menu items on-site under staff supervision except for fasting visits in which breakfast was consumed. All other study meals, snacks, and beverages were packaged in “to-go” containers for participants to consume off-site. Diet adherence was monitored by direct supervision during weekday on-site visits and with daily food diaries. Pill counts were performed at weekday feeding visits.

Data and Sample Collection

The timeline for study activities and data collection visits is shown in Figure S1. A detailed description of data collection procedures is described in Item S1. In brief, medical histories, medication use, physical activity, and habitual diet intake was assessed at baseline. Physical measurements and biospecimens, including fasting blood specimens were collected by standard protocols and 24-hour urine specimens were collected to prevent CO2 losses (Item S1). Fasting blood, 24-hour urine, and clinic BP were measured at the end of each 7-day feeding period. On the final day of the alkali and control periods 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring was performed using a validated, automated device (Spacelabs Model 90207; Issaquah, WA).

Laboratory Measurements

We measured fasting serum sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphorus, chloride, glucose, and creatinine concentrations and spot UACR (LabCorp; Burlington, NC). We measured 24-hour urine pH, sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, creatinine, urea, magnesium, sulfate, citrate, and ammonium in real time throughout the study (Litholink Corporation; Chicago, IL). Urine bicarbonate was measured in a single batch at the end of the study on previously frozen (−80°C) samples using the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase/malate dehydrogenase method (Litholink). Urine titratable acidity was calculated from urine pH, urine phosphorus and urine creatinine, their respective pKa values, and the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, as previously described.19,20 NAE was then defined classically, as the sum of urine ammonium and titratable acids minus urine alkali in the form of bicarbonate, each in mEq. Glomerular filtration rate was determined using the creatinine-based CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.21

Metabolomic Measurements

Prior to metabolomic evaluation, 24-hour urine samples were standardized for dilution. First they were tested for creatinine concentration using a modified Jaffe method on the UniCel DxC 600 Synchron Clinical System (Beckman Instruments; Brea, CA). Urine creatinine concentration were then standardized across samples by resuspending in pure water as needed. Urine was derivatized as per standard protocols at the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute (DMPI). Untargeted gas chromatography–mass spectrometry was performed on a 6890N GC-5975B MS (Agilent Corporation; Santa Clara, CA) scanning from m/z 50-600. Peaks were annotated using custom DMPI retention time libraries and spectra (Item S1).

Primary Statistical Analysis

First, raw 24 hour urine values and changes were explored within and across individuals to evaluate for potential treatment order effects or outliers. To account for over- or under-collection of serial 24 hour urines, we used a regression calibration approach to express each 24 hour quantity adjusted to a constant within-person mean urine creatinine level. Outcomes were analyzed according to randomization assignment using a marginal model with fixed-effect terms for period, sequence, treatment assignment, CKD main effect, and treatment-by-CKD interaction using residual maximum likelihood with random effects for each participant. For outcomes with two measurements in a period (i.e., two consecutive day clinic BP measurements and 24-hour urine collections), values were treated as replicates, averaging across available data. Hypothesis tests for fixed effects were reported using a small sample Kenward-Roger adjustment to the degrees of freedom. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant main effects and P value <0.2 were considered statistically significant for alkali-by-CKD interaction, due to the exploratory nature and high risk of type 2 error. Effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals for treatment are presented for all outcomes including two simple effects by CKD status estimated with the interaction model.

Analyses were conducted with Stata 15 SE.

Exploratory Metabolomics Analyses

Untargeted urine metabolites were log transformed. Metabolites that were missing in ≥50% of specimens were removed and the remainder of missing values were imputed (Item S1). Metabolites were then filtered to exclude metabolites without CAS annotations.

The effect of alkali therapy on metabolites was evaluated using mixed effects linear regression with a random effect for participants and fixed effects for treatment period and visit number. Only complete cases with paired measurements across time points were retained. P-values from each regression were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment. Discriminant analysis was used as a secondary approach to confirm key findings (Item S1).

Results

Participants

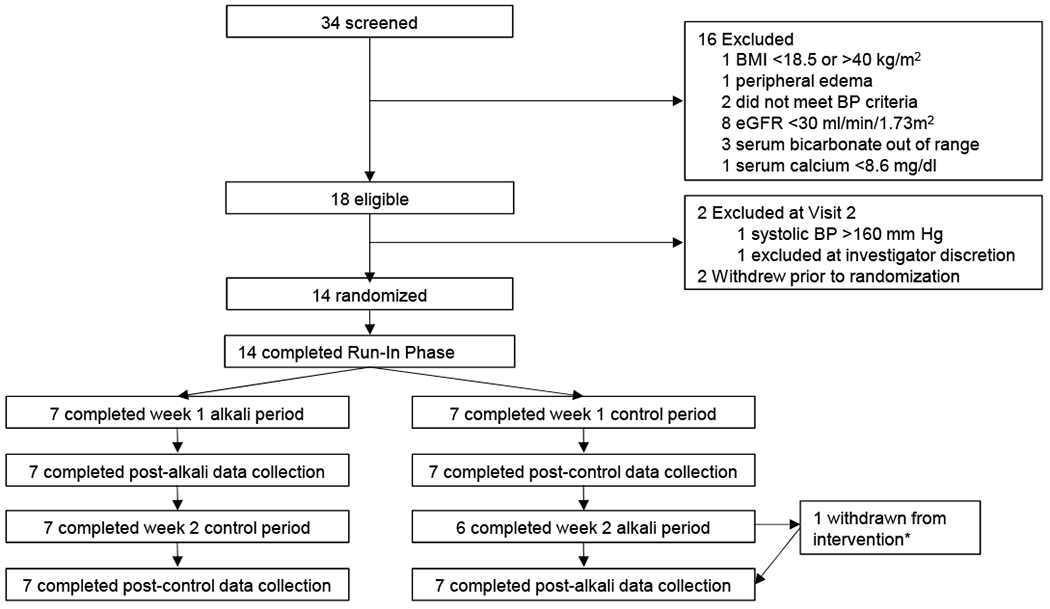

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of study participants. Fourteen participants were randomized and completed all data collection visits. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Overall, five participants were male, eight were white, mean age was 68 ± 8 years, mean body mass index was 29.6 ± 4.0 kg/m2, eight had CKD, and one had serum bicarbonate <22 mEq/l. Compared to participants without CKD, those with CKD had a lower mean eGFR (50.7 ± 9.2 versus 85.9 ± 12.0 ml/min/1.73 m2) and higher mean BP (121.9 ± 12.1/68.3 ± 3.6 versus 116.2 ± 10.8/ 64.5 ± 11.9 mm Hg). Serum bicarbonate concentrations were similar between groups (23.3 ± 1.2 for non-CKD and 23.5 ± 0.9 mEq/l for CKD).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants beginning on in-person screening visits through protocol completion. *withdrawn from treatment on day 6 of 7 day alkali period due to hyponatremia. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline

| Non-CKD (n=6) | CKD (n=8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, y | 68.3 ± 9.4 | 67.6 ± 8.0 |

| Female sex | 4 (67) | 5 (63) |

| Race | ||

| White | 4 (67) | 4 (50) |

| Black or African American | 1 (17) | 3 (38) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (17) | 0 |

| More than one race | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Clinical Measurements | ||

| Office SBP, mm Hg | 116.2 ± 10.8 | 121.9 ± 12.1 |

| Office DBP, mm Hg | 64.5 ± 11.9 | 68.3 ± 3.6 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.7 ± 5.1 | 29.6 ± 3.2 |

| Ideal–body weight, kg | 64.3 ± 7.2 | 58.9 ± 8.3 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 106.7 ± 11.5 | 104.9 ± 8.5 |

| Laboratory Measurements | ||

| Spot UACR, mg/g | 8.8 (3.6, 15.4) | 22.5 (13.1, 76.4) |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 85.9 ± 12.0 | 50.7 ± 9.2 |

| Serum potassium, mEq/l | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.5 |

| Serum bicarbonate, mEq/l | 23.3 ± 1.2 | 23.5 ± 0.9 |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.5 |

| Health History and Behavior | ||

| History of hypertension | 3 (50) | 6 (75) |

| Use of thiazide or loop diuretics | 1 (17) | 4 (50) |

| Currently smokes cigarettes | 1 (17) | 0 |

| Physical activity, kcal·kg−1·d−1 | 34.6 (27.5, 67.3) | 46.2 (29.3, 77.5) |

| Baseline Dietary Intake | ||

| Total kilocalories per day | 2329.5 ± 485.3 | 2018.6 ± 706.2 |

| Protein, g/d | 87.2 ± 27.1 | 82.1 ± 47.9 |

| Potassium, mg/d | 3125.9 ± 948.9 | 2682.2 ± 1355.2 |

| Sodium, mg/d | 4070.9 ± 1791.5 | 3041.0 ± 1002.5 |

| Phosphorus, mg/d | 1557.0 ± 503.9 | 1340.4 ± 728.1 |

| Fiber, g/d | 23.2 ± 11.0 | 17.4 ± 8.9 |

| Fruits (excluding juice), cups/d | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 1.2 |

| Total vegetables, cups/d | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 1.7 ± 1.0 |

| Dark green vegetables, cups/d | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.7 |

| Legumes, cups/d | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.8 |

| Meat, poultry and seafood, oz/d | 4.4 ± 1.7 | 4.6 ± 2.8 |

| Dairy, cups/d | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.8 |

Continuous data are shown as means ± standard deviations or medians [interquartile range]; categorical data as frequency counts (percentages). CKD, chronic kidney disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UACR, urinary albumin-creatinine

Randomization and adherence to study interventions

Participants were evenly randomized by CKD status to the control period or alkali period first. Per weight-based dosing, 12 participants were assigned 31 mEq/d of sodium bicarbonate and one participant in each group was assigned 39 mEq/d. One participant in the non-CKD group developed hyponatremia attributed to thiazide diuretics and was withdrawn from the intervention one day early (i.e., on protocol day 19; day 6 of the 7-day alkali period), but completed final data collection. All participants were maintained on their baseline antihypertensive medications without dose changes during the study, attended all of their on-site supervised meal visits, and maintained a weight within 2 kg of their baseline value (Figure S2).

Participants consumed ≥91% of the delivered dietary nutrients based on data derived from self-recorded food diaries and direct supervision at on-site meals, which demonstrates good diet adherence (Table S1). Table 2 shows results for urine biomarkers of dietary intake. Mean 24-hour urine sodium, potassium, phosphorus, sulfate, and urea were similar for the CKD and non-CKD groups during both the control and alkali periods. Urine calcium was lower in the CKD group compared to the non-CKD group during both periods. There were no significant within group differences in these 24-hour urine markers across feeding periods, suggesting that intake was consistent during the study.

Table 2.

Adjusted urine electrolytes during the control and alkali periods by CKD status.

| Urine diet biomarker | Non-CKD (n=6) | CKD (n=8) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Control period | Alkali period | Control period | Alkali period | |

| Urea nitrogen, g/d | 9.3 ± 2.0 | 9.5 ± 1.9 | 8.5 ± 1.6 | 8.3 ± 1.8 |

| Potassium, mmol/d | 63.0 ± 12.0 | 59.0 ± 12.9 | 52.7 ± 7.1 | 52.5 ± 4.2 |

| Sodium, mmol/d | 105.3 ± 21.1 | 94.0 ± 32.8 | 107.7 ± 21.1 | 101.1 ± 10.5 |

| Magnesium, mg/d | 84.2 ± 15.5 | 81.5 ± 15.3 | 63.3 ± 22.3 | 61.8 ± 22.1 |

| Calcium, mmol/d | 149.7 ± 65.9a | 143.6 ± 80.7b | 53.5 ± 40.7a | 48.9 ± 38.9b |

| Sulfate, mmol/d | 34.1 ± 10.6 | 34.3 ± 10.5 | 30.0 ± 10.1 | 30.0 ± 9.3 |

| Phosphorus, g/d | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

Data expressed as means ± standard deviations. All participants completed two consecutive 24-hour urine collections at the end of the alkali and control periods except one participant in the non-CKD group who completed one 24-hour urine collection at the end of the control period. Urine electrolytes are calibrated by regression to a constant mean urine creatinine concentration in each individual over the study period. P-values for between group difference during the control and alkali periods were

<0.01 and

0.01, respectively.

Self-reported side effects

No differences were observed in the number of patients with self-reported side effects during the run-in, control, and alkali periods (Table S2).

Serum biochemistries

Serum concentrations of phosphorus, calcium, and bicarbonate were similar among the CKD and non-CKD group during the control period, but potassium was higher in those with CKD (Table S3). Each of these measures were similar among the groups during the alkali period except for serum bicarbonate which was higher in the CKD group compared to the non-CKD group (25.8 mEq/L vs. 23.2 mEq/L; p=0.02). Serum bicarbonate was 2.6 (95% CI, 1.5-3.7) mEq/l higher at the end of the alkali compared to the control period for the CKD group (p<0.001), but there was no change in the non-CKD group (p=0.6; p-interaction=0.005).

NAE and urine acidity markers

Figure 2 depicts individual participant-level change in urine acidity markers from the first period to the second period comparing participants who were randomized to the control period first compared to the alkali period first. Approximate symmetry suggests an absence of meaningful order effects for all analytes with the exception of citrate. Raw effects on citrate excretion appear larger for those treated with control followed by alkali, compared to alkali followed by control, justifying adjustment for sequence in our analyses. Differences in 24 hour urine creatinine across periods appear meaningful in magnitude and random, thus we primarily present 24 hour urine results corrected for these differences.

Figure 2. Change in urine acidity markers comparing the end of the second week to the end of the first week in each ABC participant.

Points on the X-axis represent individual measurements within 14 participants (all); 8 individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are represented by closed circles (•) and 6 individuals without CKD are represented by open circles (ο), arranged in order of pre-post change. Left sided panels represent individuals who were randomized to the control period first followed by the alkali period. Negative values in the left panels represent lower values in the alkali period. Right sided panels represent individuals who were randomized to the alkali period first followed by the control period. Positive values in the right panels represent lower values in the alkali period. Approximate symmetry represents an absence of order effects for all analytes except citrate, in which an order effect is possible.

During the control period, when all participants were consuming identical diets, urine pH, ammonium, and citrate were statistically lower in the CKD compared to the non-CKD group (each p<0.05; Table 3). After alkali, only urine ammonium remained significantly lower in the CKD group compared to the non-CKD group, while there were no statistically significant between-group differences in urine pH, NAE, bicarbonate, and citrate (Table 3). The effects of alkali supplementation on NAE (p-interaction=0.1), urine ammonium (p-interaction=0.08), urine pH (p-interaction=0.2), and citrate (p-interaction=0.1) were greater for patients with versus without CKD. Alkali was associated with a greater increase in urine pH in the CKD group (0.9 [95% CI, 0.6-1.3]; p<0.001) compared to the non-CKD group (0.6 [95% CI, 0.2-1.0]; p=0.01) and was associated with increased urine citrate in the CKD group (63.6 [95 CI%, 11.4-115.7] mg/d; p=0.02) without having a statistically significant effect on urine citrate in the non-CKD group (9.3 [95% CI, −51.0 to 69.5] mg/d; p=0.7).

Table 3.

Adjusted urine acid excretion biomarkers during the control and alkali periods by CKD status.

| Urine acid excretion marker | Non-CKD (n=6) | CKD (n=8) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Control period | Alkali period | Net difference* | Control period | Alkali period | Net difference* | |

| NAE, mEq/d | 30.4 ± 13.1 | 25.0 ± 13.8 | −5.4 (−14.5, 3.6) | 26.7 ± 8.1 | 13.4 ± 12.7 | −13.3 (−21.1, −5.5)a |

| pH | 6.2 ± 0.5c | 6.8 ± 0.3 | 0.6 (0.2, 1.0)a | 5.7 ± 0.2c | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3)a |

| Ammonium, mEq/d | 25.7 ± 8.0c | 25.0 ± 8.5d | −0.7 (−4.5, 3.1) | 16.1 ± 6.5c | 11.3 ± 5.2d | −4.8 (−8.1, −1.5)a |

| Bicarbonate, mEq/d | 5.6 ± 6.1 | 8.1 ± 7.7 | 2.5 (−2.3, 7.3) | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 5.8 ± 5.5 | 4.9 (0.7, 9.0)b |

| Citrate, mg/d | 689.1 ± 219.6c | 698.3 ± 215.5 | 9.3 (−51.0, 69.5) | 422.4 ± 195.7c | 485.9 ± 248.2 | 63.6 (11.4, 115.7)b |

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations and β coefficients (95% confidence interval). Values are regressed to mean 24-hour urine creatinine. All participants completed two consecutive 24-hour urine collections at the end of the alkali and control periods except for one participant in the Non-CKD group who completed one 24-hour urine collection at the end of the control period. Significant alkali-by-CKD interaction, with P-interaction of <0.2 for NAE, ammonium, pH and citrate; therefore, the overall result was not presented. CKD, chronic kidney disease; NAE, net acid excretion. P-value for within-group net difference

≤0.01 and

<0.05. P-value for between-group difference

<0.05 and

<0.01.

Net difference in urine acidity markers was defined as the value at the end of the alkali period minus the value at the end of the control period.

Blood Pressure

Although mean 24-hour and office BP were generally lower after alkali exposure, this was not statistically significant overall or by patient subgroup (Table S4).

Metabolomic Changes

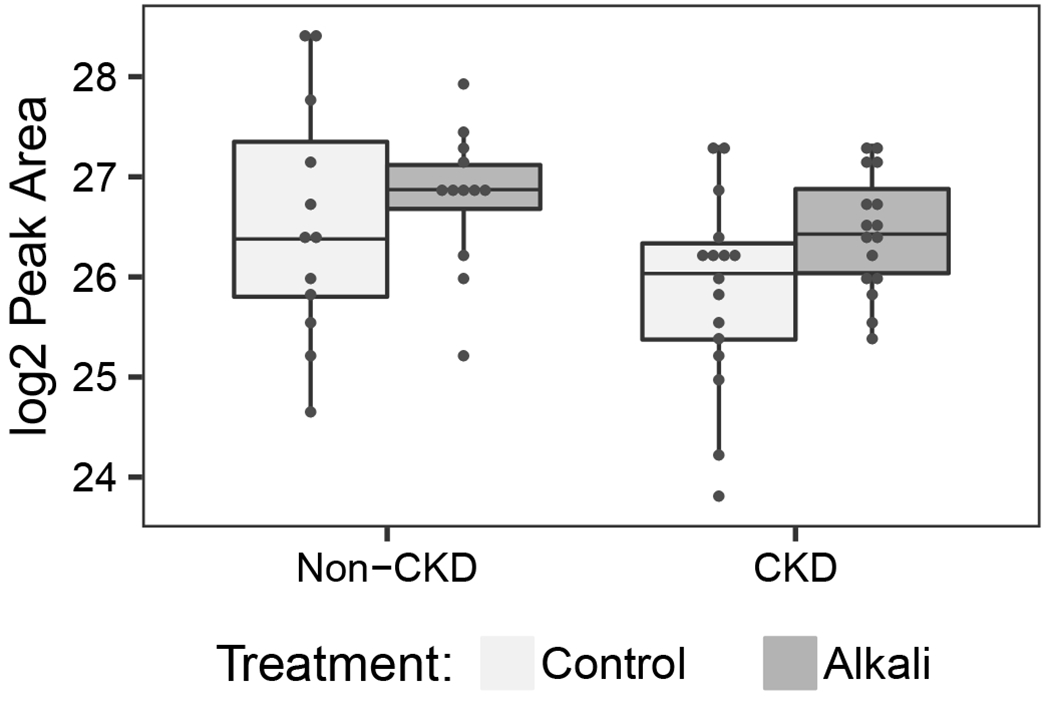

Using urine untargeted gas chromatography–mass spectometry, we characterized 207 unique and identifiable metabolites across samples. Sixty-six were present in less than 50% of samples and were excluded from further analysis. Using mixed-effects linear regression, we found that 15 metabolites were raised by alkali administration at a nominal p-value of <0.05 in CKD participants and 13 were lowered in non-CKD participants (Table 4). Only 3 annotated urine metabolites in the CKD participants, and no metabolites in the non-CKD participants, had significant changes based on FDR-adjusted p-values <0.05 (Table 4). These changes are annotated as rise in 3-indoleacetic acid, citric acid/isocitric acid, and glutaric acid in CKD patients. Each of these are excreted primarily as their conjugate base at physiologic urine pH (3-indoleacetate, citrate/isocitrate, and glutarate; Figure 3). Model fit for each of these annotated metabolites was satisfactory based on residual analysis and no metabolites values were imputed for these analytes. Sparse partial-least squares discriminant analysis (sPLS-DA) confirmed that these metabolites best discriminated between control and intervention periods with stability across models (Table 4).

Table 4.

Urine Metabolite Changes in Alkali Compared to Control Periods†

| Metabolite | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Fold-Change | p | FDR-adj p | sPLS-DA‡ | |

| CKD (n=8) | ||||

| 3-Indoleacetic Acid | 1.53 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 1 (0.98) |

| Citric Acid/Isocitric Acid | 1.50 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 1 (1) |

| Glutaric Acid | 1.30 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 1 (1) |

|

| ||||

| Azelaic Acid | 1.34 | 0.007 | 0.2 | |

| Succinic Acid | 1.33 | 0.008 | 0.2 | 1 (0.42) |

| Fumaric Acid | 1.29 | 0.009 | 0.2 | 1 (0.38) |

| Ethylmalonic Acid | 1.12 | 0.01 | 0.2 | -- |

| /γ-Hydroxybutyric Acid | ||||

| Adipic Acid | 1.43 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 1 (0.38) |

| Alpha-Ketoglutarate | 1.24 | 0.02 | 0.3 | -- |

| Methylmalonic Acid | 1.25 | 0.03 | 0.3 | -- |

| Guaiacol | 1.62 | 0.03 | 0.3 | -- |

| Decanoic Acid* | 1.55 | 0.03 | 0.3 | -- |

| Tricarballylic Acid€ | 1.66 | 0.03 | 0.4 | -- |

| p-Cresol | 1.21 | 0.04 | 0.4 | -- |

| Glycolic Acid* | 1.14 | 0.04 | 0.4 | -- |

| Non-CKD (n=6) | ||||

| Palmitic Acid | 0.58 | 0.002 | 0.1 | 1 (1) |

| o-Hydroxyhippuric Acid | 0.48 | 0.006 | 0.2 | 1 (1) |

| Stearic Acid | 0.59 | 0.007 | 0.2 | 1 (0.98) |

| 3-Hydroxybenzoic Acid | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 1 (0.98) |

| N-Methylglutamic Acid | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 1 (0.96) |

| Pyruvic Acid | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 1 (1) |

| 1,2-Propanediol | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 1 (0.82) |

| Mandelic Acid | 0.77 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 1 (0.84) |

| N-2-Furoylglycine | 0.58 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 1 (0.78) |

| Uracil | 0.79 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 1 (0.36) |

| 2,3-Dihydroxybenzoic Acid | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 1 (0.66) |

| Catechol | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 1 (0.68) |

| Oxalic Acid | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 1 (0.60) |

Note: Darkened rows represent metabolite changes strongly supported by both linear mixed models of individual metabolites and sparse least squares discriminant analysis (sPLS-DA) identifying multivariate representations with strong and stable loading. Loadings with stability <0.35 are not depicted. Metabolites present in sample blanks at levels >0.5 times the levels detected in samples were removed from the table. These included: myristic acid/pentadecanol; nonanoic acid; tiglic acid; glycerol; undecanoic acid/1-dodecanol. Metabolites are annotated in CAS as acids but excreted primarily as organic anions at physiologic urine pH given generally low pKa for most. Acid nomenclature has been retained here but they are discussed as their conjugate base form throughout the remainder of the article.

sPLS-DA indicates metabolites that also loaded on components using sPLS-DA by indicating the loaded component number (stability or proportion of cross-validated models in which the metabolite was selected).

Indicates metabolite detected frequently in sample blanks at concentration 0.25-0.49 of sample concentrations.

Metabolite was imputed in ~50% of samples due to missing data. Metabolites missing in more than 50% of samples were not imputed or further analyzed.

Figure 3. Levels of selected metabolites impacted by alkali depicted by study period and CKD status in the ABC Study.

Metabolites supported by both linear mixed models and sparse partial least squares discriminant analysis are presented. Scatterplots with overlying boxplots reveal log2 peak areas according to alkali and control periods in CKD and non-CKD for each of the following: (A) 24-hour urine 3-indoleacetate; (B) 24-hour urine citrate/isocitrate; (C) 24-hour urine glutarate. These metabolites were present in each sample tested and did not require imputation.

Discussion

In this controlled cross-over study of alkali supplementation, we report several key differences in the excretion of acids and organic anions in participants with and without CKD. First, in participants with mild to moderate CKD, we found lower urine ammonium, lower pH, and lower urine citrate compared to participants without CKD despite identical dietary intake. Second, the response to alkali loading was different in participants with and without CKD. Following oral alkali supplementation, urine citrate excretion increased significantly only among participants with CKD, restoring their citrate excretion to similar levels as the non-CKD group. Urine pH also rose more among CKD participants. Urine ammonium and classically defined NAE (i.e. urine ammonium plus titratable acidity minus urine bicarbonate) fell in the CKD group with alkali. Third, using exploratory metabolomics, we identified several urine organic anions in addition to citrate that rose among participants with CKD receiving alkali supplementation. Urine organic anions are base equivalents. They are currently not incorporated in classic calculations of NAE because they are assumed to be constants, proportional only to body size.22,23 This central premise is relevant because deficits between classic NAE and calculated acid production in CKD have raised concerns about ongoing, daily acid imbalance in CKD, in conflict with the physiologic principles of equilibrium and steady-state.24 More practically, these measurable physiologic compensations to maintain equilibrium in CKD could be used to identify subclinical acidosis and intervene sooner to prevent consequences of overt acidosis.25

We did not note a blunted response of NAE to alkali in our CKD participants as seen in other studies. Nonetheless our results reveal other acid-base adaptations that are consistent with a state of subclinical acidosis. First of all, in this CKD population without overt metabolic acidosis we noted lower urine ammonium as often detected in CKD. This fall in urine ammonium excretion is thought to be due to a reduced capacity for ammonium generation in the kidney and an initiating event in the development of acidosis. However, also consistent with known physiology, participants with CKD had lower urine pH, contributing to higher titratable acidity.19 This is a well described compensation in CKD to allow more acid excretion despite falling ammoniagenesis. Less well-recognized from an acid-base perspective are the lower levels of urine organic anions at baseline in CKD, which have major consequences on balance. Urine organic anions have long been considered measures of acid production, with each excreted equivalent contributing to a higher equivalent of acid production.25 Thus, the fall in urine organic anions in CKD may be a powerful mechanism to maintain acid-base equilibrium in CKD.

We found that urine citrate, a well-known organic anion, is lower in CKD participants at baseline and restored to non-CKD levels with alkali supplementation. Using metabolomics, a large number of other organic anions showed similar patterns although these were not rigorously quantified by our untargeted approach and many were not significant after testing for multiple comparisons. Urine samples were acidified prior to measurement and these are annotated by CAS as ‘acids,’ but with low pKa values most are primarily excreted as their conjugate bases, or organic anions, at urine pH. Most significant among these were urine glutaric acid, urine 3-indoleacetic acid, and urine citrate/isocitrate, each rising with alkali in our CKD participants. A variety of other urine metabolites had nominally significant increases, but did not reach false discovery rate significance. Altogether, our exploratory results found a set of carboxylic acids (i.e. 3-indoleacetic acid and glycolic acid), dicarboxylic acids (i.e. fumaric acid, succinic acid, ethylmalonic acid, methylmalonic acid, alpha-ketoglutaric acid, azelaic acid and adipic acid), and tricarboxylic acids (i.e. citric acid/isocitric acid) in the urine after alkali in CKD, likely representing excretion of their conjugate bases. Modulation of the production and excretion of these and other organic anions in the urine may be an important mechanism to maintain acid-base equilibrium in CKD as urine ammonium falls.

Our findings related to urine citrate are consistent with study results from Goroya et al. who compared urine citrate excretion in patients with CKD stages 1 and 2 before and after they consumed a 30-day base-producing fruit and vegetable diet. In this group without overt metabolic acidosis at baseline, urine citrate excretion was lower in patients with CKD stage 2 compared to CKD stage 1 on a standard diet. A base-producing diet was associated with increased citrate excretion in both groups.13 In contrast to Goraya et al., we compared patients with CKD stages 2-3 to patients with normal kidney function and controlled for dietary confounders with a rigorous feeding protocol supplemented with sodium bicarbonate pills. Taken together, our results are complementary and support the candidacy of urine citrate as a marker for subclinical acidosis in CKD. Our findings also suggest that increased urine citrate may be observed as early as 7 days after alkali supplementation. Additional studies are needed to test the utility of urine citrate as a predictive biomarker of impending metabolic acidosis.

Identifying subclinical acidosis is important because it could be used to guide alkali supplementation earlier in CKD, thus potentially improving clinical outcomes, though potential clinical benefits of early intervention need to be proven. Current use of alkali in overt acidosis only may miss this larger population with subclinical acidosis that could derive benefit. On the other hand, indiscriminate use of sodium bicarbonate in all patients with CKD could include unacceptable risks, such as sodium loading and hypertension. We did not note increases in blood pressure or body weight on sodium bicarbonate in this study. However, we included augmented use of sodium chloride in the control period so that total sodium exposure was constant. In practice, sodium bicarbonate would raise total sodium exposure.

Limitations of our study include its small sample size, open-label design, short feeding duration, lack of washout period between intervention periods, and lack of ambulatory BP measures at baseline. Use of objective outcomes measured without knowledge of the treatment assignment may somewhat mitigate concerns about the open-label design. We did not incorporate a washout period in order to maintain close continuous contact with participants and minimize losses to follow-up. Only citrate demonstrated potentially meaningful order effects based on our exploratory evaluation. Because citrate was reduced by alkali and this reduction appeared mitigated by the order, this is a conservative bias that may have attenuated our results towards the null. We also had many strengths. We used a random-order, cross-over design involving a feeding protocol that repeated exactly across study periods, a gold-standard approach to control for potential confounding by diet. This was particularly important for the validity of our study results since dietary composition, such as potassium depletion, can also lower urine citrate. Additional strengths include near complete participant adherence to sodium bicarbonate as assessed by pill count, and good adherence to the study diet as evidenced by the consistent excretion of urine dietary markers across the intervention periods. We also carefully account for other potential confounders by frequency matching demographics and maintaining stable weight and medication regimens across follow-up. We acknowledge that because the funding period ended before recruitment was completed, not all participants were matched. Additionally our small sample size prevented us from adjusting for other potentially relevant cofounders, such as diuretic use, that may have confounded some baseline measurements across CKD and non-CKD groups. The cross-over design primarily assesses within person change in biomarkers therefore these imbalances are unlikely to generate bias in our primary outcomes. Finally, for biomarker assessment we included two consecutive 24-hour urine specimens in each period to increase the accuracy of urine study results.

In summary, our results demonstrate acid-base compensations, consistent with subclinical metabolic acidosis among adults with CKD who have relatively preserved serum bicarbonate concentrations. While increased alkali exposure further reduced NAE in adults with CKD, urine citrate excretion was partially restored by alkali among patients with CKD. Thus, urine citrate may identify subclinical acidosis in CKD for future targeted alkali trials.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Timeline of ABC Study activities.

Figure S2. Participant weight trajectories during the interventional feeding periods.

Item S1. Supplemental methods.

Table S1. Summary of study diet adherence based on the total energy and nutrients delivered vs consumed.

Table S2. Number of people with self-reported side effects during the study intervention periods.

Table S3. Serum biochemistry results at the end of each intervention period by CKD status.

Table S4. Net difference in BP parameters comparing alkali to control period by CKD status.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge the effort and commitment of the participants from the ABC Study. We additionally acknowledge assistance with recruitment from faculty affiliated with the Duke Primary Care Research Consortium and the Duke Division of Nephrology. We thank Dr. Christopher Newgard for helpful consultation.

Support:

The ABC Study was supported by NIDDK grant K23DK095949 to JJS and a pilot and feasibility award from the Duke O’Brien Center for Kidney Research (P30DK096493) to JJS. CCT was partially supported by a supplemental research training award from the NHLBI (R01HL122836). JRB received salary support from NIA P30-AG028716. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, reporting, or the decision to submit for publication.

Financial Disclosure:

Dr. Scialla has received consulting fees from Tricida and modest research support for clinical event committees from GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi. The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data Sharing: De-identified individual level metabolomics and biochemical data presented in this manuscript may be shared with qualified investigators with approved research proposals, established data use agreements and collaboration with the study team for up to 24 months after publication. Requests should be made to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Workeneh BT, Mitch WE. Review of muscle wasting associated with chronic kidney disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(4):1128S–1132S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah SN, Abramowitz M, Hostetter TH, Melamed ML. Serum bicarbonate levels and the progression of kidney disease: a cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(2):270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovesdy CP, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of serum bicarbonate levels with mortality in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(4):1232–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navaneethan SD, Schold JD, Arrigain S, et al. Serum bicarbonate and mortality in stage 3 and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(10):2395–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramowitz MK, Melamed ML, Bauer C, Raff AC, Hostetter TH. Effects of oral sodium bicarbonate in patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(5):714–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wesson DE, Mathur V, Tangri N, et al. Veverimer versus placebo in patients with metabolic acidosis associated with chronic kidney disease: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10179):1417–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Iorio BR, Bellasi A, Raphael KL, et al. Treatment of metabolic acidosis with sodium bicarbonate delays progression of chronic kidney disease: the UBI Study. J Nephrol. 2019;32(6):989–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo CH, Wesson DE. Treatment of metabolic acidosis in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or oral bicarbonate reduces urine angiotensinogen and preserves glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int. 2014;86(5):1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moranne O, Froissart M, Rossert J, et al. Timing of onset of CKD-related metabolic complications. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(1):164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wesson DE, Pruszynski J, Cai W, Simoni J. Acid retention with reduced glomerular filtration rate increases urine biomarkers of kidney and bone injury. Kidney Int. 2017;91(4):914–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goraya N, Simoni J, Sager LN, Pruszynski J, Wesson DE. Acid retention in chronic kidney disease is inversely related to GFR. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018;314(5):F985–F991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahajan A, Simoni J, Sheather SJ, Broglio KR, Rajab MH, Wesson DE. Daily oral sodium bicarbonate preserves glomerular filtration rate by slowing its decline in early hypertensive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2010;78(3):303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goraya N, Simoni J, Sager LN, Madias NE, Wesson DE. Urine citrate excretion as a marker of acid retention in patients with chronic kidney disease without overt metabolic acidosis. Kidney Int. 2019;95(5):1190–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goraya N, Simoni J, Sager LN, Mamun A, Madias NE, Wesson DE. Urine citrate excretion identifies changes in acid retention as eGFR declines in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019;317(2):F502–F511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raphael KL. Metabolic Acidosis and Subclinical Metabolic Acidosis in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(2):376–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scialla JJ, Brown L, Gurley S, et al. Metabolic Changes with Base-Loading in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(8):1244–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin PH, Allen JD, Li YJ, Yu M, Lien LF, Svetkey LP. Blood Pressure-Lowering Mechanisms of the DASH Dietary Pattern. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:472396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scialla JJ, Asplin J, Dobre M, et al. Higher net acid excretion is associated with a lower risk of kidney disease progression in patients with diabetes. Kidney Int. 2017;91(1):204–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menezes CJ, Worcester EM, Coe FL, Asplin J, Bergsland KJ, Ko B. Mechanisms for falling urine pH with age in stone formers. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019;317(7):F65–F72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frassetto LA, Todd KM, Morris RC Jr, Sebastian A. Estimation of net endogenous noncarbonic acid production in humans from diet potassium and protein contents. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1998;68(3):576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scialla JJ, Anderson CA. Dietary acid load: a novel nutritional target in chronic kidney disease? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(2):141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemann J Jr., Bushinsky DA, Hamm LL. Bone buffering of acid and base in humans. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285(5):F811–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh MS. New perspectives on acid-base balance. Semin Dial. 2000;13(4):212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Timeline of ABC Study activities.

Figure S2. Participant weight trajectories during the interventional feeding periods.

Item S1. Supplemental methods.

Table S1. Summary of study diet adherence based on the total energy and nutrients delivered vs consumed.

Table S2. Number of people with self-reported side effects during the study intervention periods.

Table S3. Serum biochemistry results at the end of each intervention period by CKD status.

Table S4. Net difference in BP parameters comparing alkali to control period by CKD status.