Abstract

Background:

Disproportionately high acute care utilization among children with medical complexity (CMC) is influenced by patient-level social complexity.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to determine associations between ZIP code level opportunity and acute care utilization among CMC.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

This cross-sectional, multicenter study used the Pediatric Health Information Systems database, identifying encounters between 2016–2019. CMC aged 28 days to <16 years with an initial emergency department (ED) encounter or inpatient/observation admission in 2016 were included in primary analyses.

Main Outcome and Measures:

We assessed associations between the nationally-normed, multi-dimensional, ZIP code-level Child Opportunity Index 2.0 (COI) (high COI = greater opportunity), and total utilization days (hospital bed-days plus ED discharge encounters). Analyses were conducted using negative binomial generalized estimating equations, adjusting for age and distance from hospital and clustered by hospital. Secondary outcomes included intensive care unit (ICU) days and cost of care.

Results:

A total of 23,197 CMC were included in primary analyses. In unadjusted analyses, utilization days decreased in a stepwise fashion from 47.1 (95% CI: 45.5, 48.7) days in the lowest COI quintile to 38.6 (36.9, 40.4) days in the highest quintile (p<0.001). The same trend was present across all outcome measures, though was not significant for ICU days. In adjusted analyses, patients from the lowest COI quintile utilized care at 1.22-times the rate of those from the highest COI quintile (1.17, 1.27).

Conclusions:

CMC from low opportunity ZIP codes utilize more acute care. They may benefit from hospital and community-based interventions aimed at equitably improving child health outcomes.

Introduction

Children with medical complexity (CMC) account for disproportionately high hospital utilization rates and health expenditures.1–3 There is also evidence that CMC have higher rates of social complexity. For instance, despite higher socioeconomic status than parents of children with non-complex chronic disease, parents of CMC more commonly report financial and social hardships.4 Parents are also more likely to report health-related social needs on routine inpatient screening.5 CMC utilize significantly more social work services in a medical setting than non-medically complex children.6,7 Previous work has suggested that certain patient- or family-level factors like public insurance, non-White race, and barriers to consistent follow up influence risk of preventable hospitalizations and more hospital bed-days.8

The Child Opportunity Index (COI) 2.0 is a publicly-available, multidimensional standardized measure of neighborhood-based conditions, resources, and opportunities relevant to healthy childhood development.9 It is comprised of 29 indicators divided across three domains: education, health and environment, and social and economic opportunity. The COI 2.0 provides a single comparable metric across virtually all United States (US) census tracts. Prior studies demonstrate that children residing in lower COI neighborhoods are more likely to have sub-optimal health outcomes.10–12 These children present for more acute care visits, independent of neighborhood income, suggesting that residential factors related to educational, environmental, and socioeconomic opportunity play important roles in health outcomes.10 Similarly, studies have shown links between lower COI and increased urgent care and Emergency Department (ED) visits for any type of respiratory condition, as well as higher hospitalization rates for asthma,11 and other ambulatory care sensitive conditions.12

Individually, CMC and children residing in low COI neighborhoods are both noted to have increased acute care utilization.1–3,10–12 Despite these known links, the impact of opportunity as measured by the ZIP code level COI on acute care utilization for CMC is not known. The objective of this study was to examine associations between the nationally-normed COI and hospital utilization among CMC. We hypothesized that CMC living in lower COI ZIP codes would have increased hospital utilization compared to those from higher COI ZIP codes.

Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional, multicenter study examined acute care visits by CMC at hospitals included in the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database from 2016–2019. PHIS is an administrative and billing database maintained by the Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas) containing encounter-level data from 49 tertiary-care pediatric hospitals across the US. Participating hospitals are in 27 states and Washington, DC, represent 17 of the 20 major US metropolitan areas, and account for 15% of all inpatient pediatric care (excluding normal newborns) in the US. Hospitals submit encounter-level data, including patient demographics, patient home ZIP code, billing data, and diagnoses using International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes. Data are deidentified at the time of submission. Data quality and reliability are assured by joint efforts between the Children’s Hospital Association and participating hospitals. This study was deemed exempt by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

We included children aged 28 days to <16 years at the time of initial encounter. Each child had ≥1 complex chronic condition (CCC)13 and their first ED encounter or inpatient/observation admission between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2016. This age range was chosen to exclude initial Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (ICU) encounters and to ensure children remained <19 years old throughout the study period. Because there is no perfect approach to identifying CMC within administrative data, we chose to define CMC as the population of children who had at least 1 CCC.1 We further stratified this population of CMC into those that were less (1–2 CCCs) and more complex (3+ CCCs). To best capture the population most at risk for frequent acute care utilization, we focused our primary analyses on the more complex group.1,14–17 This population of CMC, those with 3+ CCCs, are known to have higher utilization rates than children with 1 CCC (e.g., Inflammatory Bowel Disease).18 We excluded patients with in-hospital deaths during the study period and encounters with missing or invalid ZIP codes. We also excluded data from 6 hospitals who provided incomplete information.

Primary Exposure – Child Opportunity Index 2.0

The primary exposure variable was the nationally-normed COI quintile (very low, low, moderate, high, very high opportunity) based on the patient home ZIP code from the index encounter. The COI is a composite measure that includes 29 indicators of neighborhood conditions and resources that affect children’s healthy development. Indicators include access to high quality education, healthy foods, and green space, proximity to environmental toxins, health insurance coverage, and local employment and poverty rates.9 Each indicator is transformed to a z-score, standardized, and weighted by how strongly it predicts children’s long-term health and economic outcomes. Indicators are then combined into overall and domain scores (education, health and environment, and social and economic), and divided into nationally-normed quintiles. In accordance with the granularity of geographic data available in the PHIS database, we used the COI 2.0 aggregated from the census tract to the ZIP code level by the COI developers19 and merged with available clinical data.

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome was total utilization days (hospital bed-days + ED discharge encounters) from the time of the initial encounter in 2016 through December 31, 2019. We chose this combined metric to identify any day a family was required to interrupt their usual home life to spend time in the ED or hospital. Hospital bed-days were defined as the total number of observation or inpatient bed-days counted from the calendar day of ED triage to the day of discharge. ED discharge encounters were those ED encounters that did not result in an inpatient stay. Secondary outcomes included total ED encounters (ED discharge + ED admission), total ED discharge encounters, total ED admission encounters, total inpatient/observation encounters, hospital bed-days, ICU days, and total costs during the study period. In PHIS, costs are estimated from charges using hospital- and year-specific cost-to-charge ratios. We also evaluated annual utilization of the study cohort, including the proportion of the cohort with ED discharge visits, hospitalizations, or both within the study timeframe.

Covariates

We examined demographic variables including age, sex, race and ethnicity (Asian, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, Other), payer type (government, private, other), hospital Census region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West), distance from the hospital (in miles), and rurality (rural, urban). We approximated the distance from the hospital using the center of the patient’s ZIP code to the center of hospital ZIP code. We used the urban-rural classification scheme developed by the National Center for Health Statistics (RUCA codes) to define each patient residence as urban or rural.20 Race and ethnicity were examined as sociopolitical constructs and included in our analyses due to known health impacts of racial residential segregation and a strong correlation with COI.21

Clinical variables included type(s) of CCC (e.g., neuromuscular), the maximum Hospitalization Resource Intensity Scores for Kids (H-RISK) across all encounters for each patient to approximate each patient’s severity, and index encounter type (ED, inpatient, observation). H-RISK is a relative weight developed from a national pediatric database that measures the severity of hospitalization based on costs for the assigned All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG).22. Demographic and clinical characteristics were selected from the index encounter.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized by COI quintile using frequencies for categorial variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. Unadjusted comparisons of differences across COI quintiles used Pearson’s chi-squared and Kruskal Wallis tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. To assess associations between COI quintile and patient outcomes, negative binomial generalized estimating equations were used, adjusting for patient age and distance from hospital while clustering by hospital. These analyses were completed for each stratum of complexity (3+ and 1–2 CCCs); results are presented as adjusted rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI). To validate findings, we performed three sensitivity analyses of primary and secondary outcomes. We examined: 1) a restricted cohort including patients living within the 75th percentile of distance from the hospital to exclude those most likely to seek acute care at non-PHIS hospitals closer to their home; 2) a restricted cohort including patients with an encounter in every year of the study to exclude patients who moved during the study period; and 3) the full cohort including maximum H-RISK in adjusted models to account for the potential impact of disease severity on utilization. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cohort Demographics

Of 175,039 children with ≥1 CCC in the study cohort, 23,197 (13%) had 3+ CCCs. Most children with 3+ CCCs were <5 years of age, male, non-Hispanic White, government-insured, and lived in an urban setting (Table 1). Most had an index encounter that was an inpatient admission. The median distance from home ZIP code to hospital was ~22 miles. The most common CCCs were within the gastrointestinal, neuromuscular, and cardiovascular categories. Although there were significant differences in presence of specific CCCs across COI quintiles, these differences were of unclear clinical significance (Supplemental Table 1). More than 80% of children with 3+ CCCs were technology dependent. Characteristics of children with 1–2 CCCs are included in Supplemental Table 2.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of Children with 3+ Complex Chronic Conditions

| Overall 23197 | Childhood Opportunity Index 2.0 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low 4944 (21.3) | Low 4784 (20.6) | Moderate 4687 (20.2) | High 4465 (19.3) | Very High 4317 (18.6) | |||

| Age | <1 year | 4001 (17.2) | 924 (18.7) | 848 (17.7) | 823 (17.6) | 742 (16.6) | 664 (15.4) |

| 1–4 years | 8030 (34.6) | 1812 (36.7) | 1673 (35) | 1604 (34.2) | 1568 (35.1) | 1373 (31.8) | |

| 5–9 years | 5358 (23.1) | 1061 (21.5) | 1066 (22.3) | 1086 (23.2) | 1053 (23.6) | 1092 (25.3) | |

| 10–15 years | 5808 (25) | 1147 (23.2) | 1197 (25) | 1174 (25) | 1102 (24.7) | 1188 (27.5) | |

| Sex | Female | 10611 (45.7) | 2236 (45.2) | 2134 (44.6) | 2205 (47) | 2044 (45.8) | 1992 (46.2) |

| Male | 12584 (54.3) | 2707 (54.8) | 2650 (55.4) | 2482 (53) | 2421 (54.2) | 2324 (53.8) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Asian | 768 (3.3) | 80 (1.6) | 125 (2.6) | 156 (3.3) | 139 (3.1) | 268 (6.2) |

| Hispanic | 4889 (21.1) | 1501 (30.4) | 1280 (26.8) | 982 (21) | 677 (15.2) | 449 (10.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3927 (16.9) | 1730 (35) | 804 (16.8) | 570 (12.2) | 501 (11.2) | 322 (7.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 11646 (50.2) | 1201 (24.3) | 2226 (46.5) | 2558 (54.6) | 2798 (62.7) | 2863 (66.3) | |

| Othera | 1967 (8.5) | 432 (8.7) | 349 (7.3) | 421 (9) | 350 (7.8) | 415 (9.6) | |

| Payor | Government | 13824 (59.6) | 4100 (82.9) | 3370 (70.4) | 2794 (59.6) | 2212 (49.5) | 1348 (31.2) |

| Private | 8406 (36.2) | 712 (14.4) | 1215 (25.4) | 1656 (35.3) | 2053 (46) | 2770 (64.2) | |

| Other | 967 (4.2) | 132 (2.7) | 199 (4.2) | 237 (5.1) | 200 (4.5) | 199 (4.6) | |

| US Census Region of Hospital | Midwest | 6175 (26.6) | 1186 (24) | 1056 (22.1) | 1194 (25.5) | 1322 (29.6) | 1417 (32.8) |

| Northeast | 3282 (14.1) | 734 (14.8) | 502 (10.5) | 560 (11.9) | 607 (13.6) | 879 (20.4) | |

| South | 8343 (36) | 2034 (41.1) | 2121 (44.3) | 1740 (37.1) | 1449 (32.5) | 999 (23.1) | |

| West | 5397 (23.3) | 990 (20) | 1105 (23.1) | 1193 (25.5) | 1087 (24.3) | 1022 (23.7) | |

| Rurality | Rural | 3154 (13.6) | 651 (13.2) | 1103 (23.1) | 830 (17.7) | 460 (10.3) | 110 (2.5) |

| Urban | 19495 (84) | 4229 (85.5) | 3595 (75.1) | 3788 (80.8) | 3874 (86.8) | 4009 (92.9) | |

| Index encounter type | Inpatient | 16862 (72.7) | 3534 (71.5) | 3440 (71.9) | 3400 (72.5) | 3299 (73.9) | 3189 (73.9) |

| ED | 3900 (16.8) | 970 (19.6) | 844 (17.6) | 765 (16.3) | 679 (15.2) | 642 (14.9) | |

| Observation | 2435 (10.5) | 440 (8.9) | 500 (10.5) | 522 (11.1) | 487 (10.9) | 486 (11.3) | |

| aDistance from hospital (miles) | 21.9 [9.8, 61.3] | 12 [5.9, 58.3] | 29.4 [10.8, 77.9] | 26.1 [11.9, 72.7] | 25.6 [13.1, 60.6] | 18.6 [11.7, 32.3] | |

| Maximum H-RISK Severity Indexb | 11.6 (12.1) | 11.9 (12.1) | 11.8 (12.2) | 11.8 (12.6) | 11.5 (11.6) | 11.1 (11.7) | |

Child Opportunity Index is nationally-normed at the ZIP code level. Data presented as N (%) or median (IQR)..

Includes Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander, American Indian Alaskan Native, or those listed as Other

Distance measured in miles from center of patient’s zip code to center of hospital’s zip code.

Hospitalization Resource Intensity Score for Kids (H-RISK) assessed across all encounters

Children with 3+ CCCs most frequently lived in lower opportunity ZIP codes as defined by the COI (Table 1). A total of 21.3% lived in very low compared to 18.6% in very high COI quintile ZIP codes (p<0.05). Compared to those in the very high COI quintile, children with 3+ CCCs in the very low COI quintile were more likely to be younger, non-Hispanic Black race, Hispanic ethnicity, government-insured, to reside closer to the hospital, to live in a rural setting, and have a higher maximum H-RISK score.

Utilization patterns among children with 3+ CCCs

In the first year of data collection (2016), 46% of children with 3+ CCCs had at least one ambulatory ED discharge encounter; 98% had at least one hospitalization. There were fewer utilization events among these children in subsequent years. In 2019, the final year of the study period, 43% of included children experienced any utilization event; 26% had an ED discharge encounter, and 33% had a hospitalization.

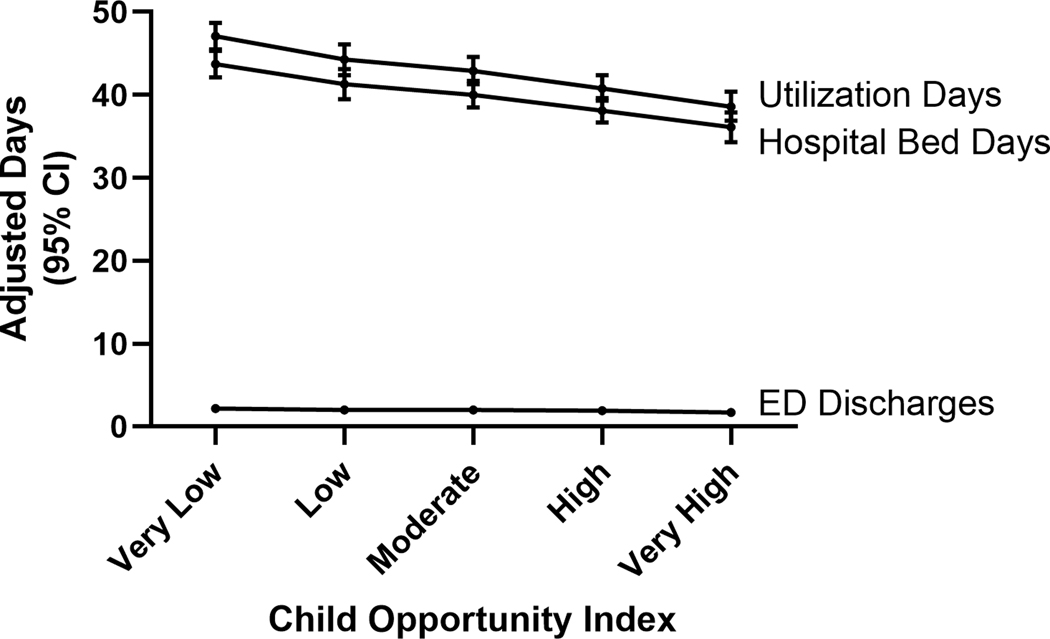

In unadjusted analyses, there was a significant, graded relationship between COI quintile and total utilization days, total number of ED encounters, ED discharge encounters, ED admission encounters, and hospital bed-days (Table 2). The primary outcome, total utilization days, decreased in a stepwise fashion from 47.1 (95% CI: 45.5, 48.7) days in the very low COI quintile to 38.6 (36.9, 40.4) days in the very high quintile (p<0.001). Figure 1 displays these relationships across quintile groupings for secondary outcomes. We also observed total costs declining consistently from an average of nearly $113K (95% CI: $100K, $127K) in the very low COI quintile to $100K (89K, 112K) in the very high COI quintile though this did not reach statistical significance. Most of the utilization (and cost) was driven by hospital bed-days.

Table 2:

Utilization patterns from 2016–2019 among Children with 3+ Complex Chronic Conditions in association with Child Opportunity Index quintile.

| Very Low (VL) | Low | Moderate | High | Very High (VH) | Pa | Adjusted Rate Ratiob (VL vs VH) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | |||||||

| Utilization Daysc | 47.1 (45.5, 48.7) | 44.3 (42.4, 46.1) | 42.9 (41.3, 44.6) | 40.8 (39.3, 42.4) | 38.6 (36.9, 40.4) | <.001 | 1.22 (1.17, 1.27) |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||||

| Total ED Encounters (Admitted + Discharged) | 5.2 (4.8, 5.7) | 4.9 (4.6, 5.2) | 4.7 (4.4, 5.1) | 4.4 (4.1, 4.8) | 4.2 (3.7, 4.7) | 0.001 | 1.26 (1.16, 1.36) |

| ED Discharged | 2.2 (2, 2.5) | 2 (1.9, 2.2) | 2 (1.8, 2.2) | 1.9 (1.6, 2.1) | 1.7 (1.5, 2.1) | 0.023 | 1.27 (1.13, 1.44) |

| ED Admitted | 2.4 (2.3, 2.6) | 2.4 (2.2, 2.6) | 2.3 (2.1, 2.5) | 2.2 (2, 2.3) | 2 (1.8, 2.2) | <.001 | 1.22 (1.15, 1.31) |

| Total Inpatient/Observation Encounters | 5.4 (5.3, 5.6) | 5.5 (5.3, 5.7) | 5.4 (5.2, 5.6) | 5.2 (5.1, 5.4) | 5.1 (4.9, 5.4) | 0.002 | 1.06 (1.02, 1.09) |

| Hospital Bed Days | 43.7 (42.1, 45.3) | 41.3 (39.5, 43.1) | 40 (38.5, 41.7) | 38.1 (36.7, 39.6) | 36.1 (34.3, 37.9) | <.001 | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) |

| ICU Days | 7.8 (7, 8.6) | 7.6 (7, 8.3) | 7.6 (6.9, 8.3) | 7.2 (6.6, 7.8) | 7 (6.3, 7.8) | 0.223 | 1.11 (1, 1.23) |

| Cost ($1000) | 113 (100, 127) | 107 (95, 120) | 104 (93, 115) | 101 (93, 112) | 100 (89, 112) | 0.178 | 1.13 (1.03, 1.24) |

Child Opportunity Index is nationally-normed at the ZIP code level. Data presented as median (IQR).

Unadjusted results calculated using Kruskal Wallis testing

Calculations pursued using negative binomial generalized estimating equations adjusted for child age and distance from hospital, clustered by hospital.

Utilization Days= Hospital Bed Days + ED Discharges.

Figure 1. Adjusted Utilization Days by COI Quintile among Children with 3+ Complex Chronic Conditions.

Calculations pursued using negative binomial generalized estimating equations adjusted for child age and distance to hospital, clustered by hospital.

Utilization Days= Hospital Bed Days + ED Discharges.

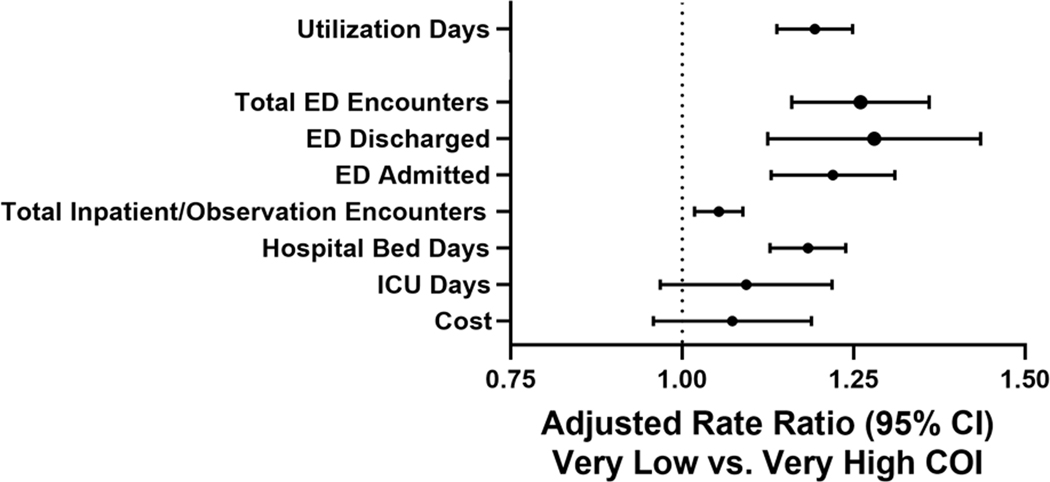

In adjusted analyses, those in the very low COI quintile utilized care at 1.22-times the rate of those in the very high COI quintile (95% CI: 1.17, 1.27). There were similar, significantly higher rates of care utilization measures including ED encounters, hospital bed-days, and cost for those living in very low compared to very high COI quintiles (range of rate ratios: 1.13–1.26; Figure 2). Although the association for ICU days was similar, this relationship did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2. Care Utilization Rate Ratio among Children with 3+ Complex Chronic Conditions, Very Low COI v. Very High COI.

Calculations adjusted for child age and distance to hospital, clustered by hospital.

Utilization Days= Hospital Bed Days + ED Discharges

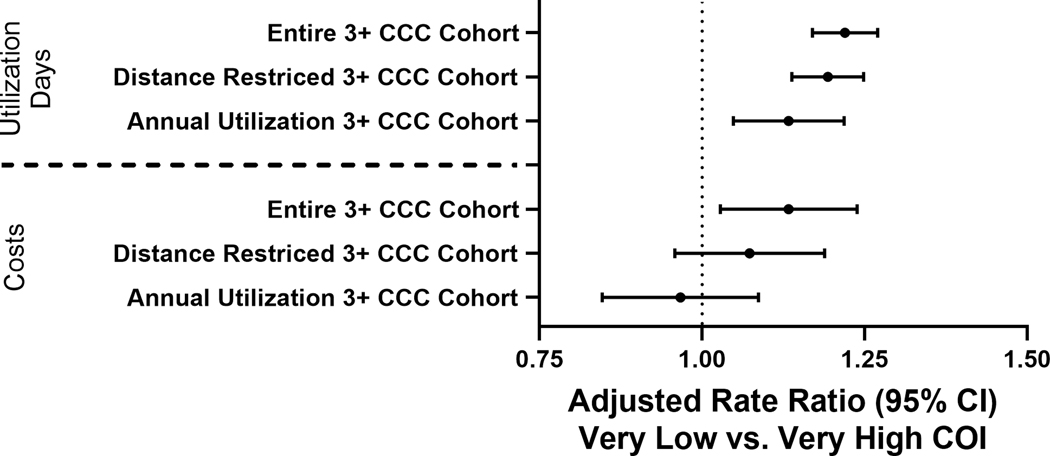

In sensitivity analyses, we separately investigated children who lived within 61.3 miles (75th percentile) of their hospital (n=17,397) and children who experienced at least one utilization event in each of the included study years (n=6,825). Our results did not meaningfully change (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 3). Similarly, we did not observe any significant differences in primary or secondary outcomes when adjusting for maximum H-RISK (Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 3. Utilization Days and Cost Rate Ratio, Very Low COI v. Very High COI in Full and Restricted Cohorts of Children with 3+ Complex Chronic Conditions (CCCs).

Calculations adjusted for child age and distance to hospital, clustered by hospital.

Distance-Restricted Cohort= Living within the 75%ile of distance from the hospital

Annual Utilization Cohort = ED discharge or inpatient/observation encounter in every year of the study, 2016–2019

Utilization patterns among children with 1–2 CCCs

We found significant decreases in utilization days with increasing nationally-normed COI quintile for children with 1–2 CCCs; however, the total number of utilization days and absolute differences between groups were notably lower than among children with 3+ CCCs (Supplemental Table 5, Supplemental Figure 1).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional, multicenter study in the US, we found that lower child opportunity, measured at the ZIP code level, was significantly associated with increased acute care utilization among CMC. The association between nationally-normed COI and acute care utilization was present for all outcome measures except ICU days for CMC with less complexity (1–2 CCCs) and for those with more complexity (3+ CCCs). Relationships were particularly stark for CMC with 3+ CCCs. The increased burden of acute care has implications for patients and their families, with each day representing time away from family, school, and/or work.23 It also has implications for hospital systems and payers, as demonstrated by the increased cost of care driven by children from lower COI quintiles.

Numerous factors may mediate this relationship between lower ZIP Code opportunity and increased utilization experienced by CMC. Residential factors captured by the COI may directly influence the health and well-being of CMC. Poor housing quality, lack of access to healthy food, and environmental pollutants may exacerbate chronic diseases resulting in increases in acute care utilization.24–26 Once hospitalized, CMC from lower opportunity ZIP codes may face additional challenges in timely and successful transition from hospital to home.23,27 Among general pediatric inpatient populations, families of lower socioeconomic status have identified limited social support, lack of transportation, and limited work flexibility as challenges surrounding hospital discharge.23 Lack of home nursing, a well-known cause of discharge delay in CMC,28 may also be influenced by neighborhood of residence, although this has not been previously described to our knowledge.

We noted important racial and ethnic disparities with children identified as non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic more likely residing in lower opportunity ZIP codes. The impact of structural racism and residential racial segregation contribute substantially to observed differences in COI.21,29 Although the current study could not address an independent effect of race on acute care utilization due to its collinearity with COI, structural racism has been broadly associated with disparities in health outcomes.29–31 This collinearity is relevant and indicates the degree to which racial segregation aligns with educational, environmental, and economic segregation (and, by extension, opportunity). Our findings support the need to overcome and dismantle systemic racism. Indeed, the ramification of racist practices like redlining persist –there are fewer opportunities within lower opportunity ZIP codes because of generational disinvestment.29

This study complements prior work highlighting the relationship between medical and social complexity, with more patient-level social risks among children with more medical needs7 and frequent reports of social hardship among families of CMC.4 Conceptually, medical and social complexity may propagate one another, with the impact of social risks contributing to higher rates of conditions that may result in medical complexity, including preterm birth32 and injury.33 Similarly, families of CMC may face additional financial and social hardships34 that act as barriers toward upward social and economic mobility.

Recognizing the increased vulnerability of CMC from disadvantaged ZIP codes may inform future interventions. At the hospital level, utilizing a measure like COI could enable risk stratification and identification of families in need of interventions including discharge navigation, home health services, and meaningful clinical-community partnership programs poised to enhance opportunities for families living in low opportunity areas. More broadly, results of this study provide yet another compelling reason for community action and policy change at the local and national levels to address systemic inequities that result in disparate opportunities for some children, magnified among CMC. Incorporating perspectives from families and community-based organizations is critical to ensure equitable outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, our inability to determine if patients accessed care at non-PHIS hospitals during the study period may have resulted in underestimation of utilization. However, prior studies have demonstrated that CMC are predominantly hospitalized at tertiary care children’s hospitals similar to those that contribute data to PHIS3,15 and that different hospital readmission is less common among children’s hospitals.35 Given the increasing regionalization of pediatric care for children extending to hospitalization of general pediatric conditions,36,37 it is unlikely we missed a large amount of patient encounters at non-PHIS tertiary care centers. Similarly, although we excluded patients who died in the hospital during the study period, we were unable to account for out-of-hospital deaths or patients who moved to a ZIP code in a different COI quintile or out of the hospital catchment area during the study period. Only two percent of the cohort moved to a different COI quintile during the study period, and restricted, sensitivity analyses including only patients living near a PHIS hospital and only patients with an encounter in every year of the study showed trends similar to our overall results, suggesting that the effect of these limitations was minimal. Additionally, demographic variables, number of CCCs, and COI quintile were assigned based on the index encounter and may have changed over the course of the study, resulting in misclassification during later years. Next, we only had access to ZIP code-level data. Although ZIP code-level COI measurement is validated19 and our results align with other studies,10–12 examining COI at the ZIP code level may result in misclassification of a small proportion of families into the wrong COI quintile, limiting our ability to assess true neighborhood-level outcomes. Individual hospitals, with access to data on their patient’s exact address and/or census tract, could replicate these analyses. They could also target interventions to the lowest opportunity, highest utilization areas. Finally, because the study design did not allow us to fully investigate the underlying mechanisms or protective factors for the trends we observed, these remain areas for future study.

Conclusion

CMC from lower opportunity ZIP codes utilize more acute care than those residing in higher opportunity ZIP codes. Interventions at both the hospital and community levels are needed to address underlying systemic and structural inequities. Incorporating perspectives from families of CMC and community-based organizations in developing interventions is critical to achieving optimal and equitable health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

No funding was secured for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Thomson reports Funding from Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) K08-HS025138. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Carroll reports funding support by grant number T32HS026122 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

References

- 1.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry JG, Hall M, Hall DE, et al. Inpatient growth and resource use in 28 children’s hospitals: a longitudinal, multi-institutional study. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(2):170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucholz EM, Toomey SL, Schuster MA. Trends in Pediatric Hospitalizations and Readmissions: 2010–2016. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson J, Shah SS, Simmons JM, et al. Financial and Social Hardships in Families of Children with Medical Complexity. J Pediatr. 2016;172:187–193.e181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fritz CQ, Thomas J, Gambino J, Torok M, Brittan MS. Prevalence of Social Risks on Inpatient Screening and Their Impact on Pediatric Care Use. Hospital pediatrics. 2020;10(10):859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coquillette M, Cox JE, Cheek S, Webster RA. Social Work Services Utilization by Children with Medical Complexity. Maternal and child health journal. 2015;19(12):2707–2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry JG, Harris D, Coller RJ, et al. The Interwoven Nature of Medical and Social Complexity in US Children. JAMA pediatrics. 2020;174(9):891–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coller RJ, Nelson BB, Sklansky DJ, et al. Preventing hospitalizations in children with medical complexity: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1628–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noelke C, McArdle Nancy, Baek Mikyung, Huntington Nick, Huber Rebecca, Hardy Erin F., and Acevedo-Garcia Dolores. . “Childhood Opportunity Index 2.0 Technical Documentation.” https://www.diversitydatakids.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/ddk_coi2.0_technical_documentation_20200212.pdf.January 15 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kersten EE, Adler NE, Gottlieb L, et al. Neighborhood Child Opportunity and Individual-Level Pediatric Acute Care Use and Diagnoses. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck AF, Huang B, Wheeler K, Lawson NR, Kahn RS, Riley CL. The Child Opportunity Index and Disparities in Pediatric Asthma Hospitalizations Across One Ohio Metropolitan Area, 2011–2013. J Pediatr. 2017;190:200–206.e201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krager MK, Puls HT, Bettenhausen JL, et al. The Child Opportunity Index 2.0 and Hospitalizations for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions. Pediatrics. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, Anderson G, Wodchis W, Guttmann A. Patterns and costs of health care use of children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1463–1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry JG, Poduri A, Bonkowsky JL, et al. Trends in resource utilization by children with neurological impairment in the United States inpatient health care system: a repeat cross-sectional study. PLoS medicine. 2012;9(1):e1001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berry JG, Agrawal R, Kuo DZ, et al. Characteristics of hospitalizations for patients who use a structured clinical care program for children with medical complexity. J Pediatr. 2011;159(2):284–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. Jama. 2011;305(7):682–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo DZ, Hall M, Agrawal R, et al. Comparison of Health Care Spending and Utilization Among Children With Medicaid Insurance. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1521–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Child Opportunity Index 2.0 ZIP Code Estimates. diversitydatakids.org: Brandeis University, The Heller School for Social Policy and Management;2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rural Health Research Center University of Washington. “Rural Urban Commuting Area Codes Data.” Accessed September 9, 2020. https://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-uses.php.

- 21.Acevedo-Garcia D, Noelke C, McArdle N, et al. Racial and Ethnic Inequities In Children’s Neighborhoods: Evidence From The New Child Opportunity Index 2.0.. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2020;39(10):1693–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson T, Rodean J, Harris M, Berry J, Gay JC, Hall M. Development of Hospitalization Resource Intensity Scores for Kids (H-RISK) and Comparison across Pediatric Populations. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(9):602–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AF, Solan LG, Brunswick SA, et al. Socioeconomic status influences the toll paediatric hospitalisations take on families: a qualitative study. BMJ quality & safety. 2017;26(4):304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster CC, Simon TD, Qu P, et al. Social Determinants of Health and Emergency and Hospital Use by Children With Chronic Disease. Hospital pediatrics. 2020;10(6):471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. “Housing And Health: An Overview Of The Literature”. June 7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poowuttikul P, Saini S, Seth D. Inner-City Asthma in Children. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56(2):248–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang LV, Shah AN, Hoefgen ER, et al. Lost Earnings and Nonmedical Expenses of Pediatric Hospitalizations. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maynard R, Christensen E, Cady R, et al. Home Health Care Availability and Discharge Delays in Children With Medical Complexity. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How Structural Racism Works - Racist Policies as a Root Cause of U.S. Racial Health Inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2015;10(9):e0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunlop AL, Essalmi AG, Alvalos L, et al. Racial and geographic variation in effects of maternal education and neighborhood-level measures of socioeconomic status on gestational age at birth: Findings from the ECHO cohorts. PloS one. 2021;16(1):e0245064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laflamme L, Hasselberg M, Burrows S. 20 Years of Research on Socioeconomic Inequality and Children’s-Unintentional Injuries Understanding the Cause-Specific Evidence at Hand. Int J Pediatr. 2010;2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Casey PH. A national profile of caregiver challenges among more medically complex children with special health care needs. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2011;165(11):1020–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan A, Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Same-Hospital Readmission Rates as a Measure of Pediatric Quality of Care. JAMA pediatrics. 2015;169(10):905–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.França UL, McManus ML. Availability of Definitive Hospital Care for Children. JAMA pediatrics. 2017;171(9):e171096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.França UL, McManus ML. Trends in Regionalization of Hospital Care for Common Pediatric Conditions. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.