ABSTRACT

Upsurge in mucormycosis cases in the second wave of SARS CoV2 infection in India has been reported. Uncontrolled diabetes is the major predisposing risk factor for these cases. The early diagnosis and surgical intervention with medical treatment may result in good clinical outcomes. The glycaemic control in diabetic patients also favours better treatment outcome in patients suffering from mucormycosis.

Keywords: Diabetes, GMS, KOH wet mount, Rhizopus arrhizus, RSA protein, steroid

Introduction

Mucormycosis, a life-threatening fungal infection, is caused by the members of order Mucorales.[1,2] Mucormycosis presents as fulminant fungal infection in debilitated patients, primarily involving the rhinofaciocranium, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, skin and kidney. Among these, rhino-orbito mucormycosis is the most common presentation where rapid tissue necrosis with black discolouration occurs at the affected site. The member of order Mucorales, genera Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, Mucor, Lichthemia, Apophysomyces, Cunninghamella, and Saksenaea, result in human infections. Rhizopus arrhizus (Rhizopus oryzae) followed by Rhizomucor spp is the leading cause of mucormycosis.[3]

Mucorales are widely distributed in an environment as saprotrophs, where they live on the dead decaying material and in soil.[4] The spores of these Mucorales enter the human body through inhalation, where they primarily colonize and infect the paranasal sinuses. In immunocompetent individuals, there is no clinical manifestation.[5] In contrast, neutropenia, uncontrolled diabetes, steroid therapy, hemato-oncological disorder promote spore germination into the coenocytic hyphae that invade the blood vessels & tissues.[6,7,8,9,10] The inhaled spores may also result in pulmonary mucormycosis in neutropenic patients.[11] Sometimes, the spores are directly inoculated at the abraded skin, especially in a burn, dressing, and traumatized patients, resulting in cutaneous mucormycosis.[12]

During the second wave of COVID 19, an upsurge in the number of mucormycosis cases has been observed across India.[13] This upsurge is a consequence of pre-existing uncontrolled diabetes, steroids induced hyperglycaemia, IL6 inhibitors (Tocilizumab), high fungal spores in the environment, especially at the construction sites.[14,15] Non-judicious use of antifungal agents, especially voriconazole as a prophylactic agent, further enhances the possibility of mucormycosis.[15] COVID-19 infection itself is a predisposing risk factor where it causes lymphopenia and endothelitis, favouring the fungal invasion. Uncontrolled diabetes and steroid use further increase the chances of invasive fungal infections. Hyperglycemia has been attributed to the high β-hydroxybutyric acid, resulting in a reduced iron-binding capacity of transferrin, which manifests as high serum Iron that favours the rapid growth of Mucorales.[16,17,18,19,20] The high load of fungal spores, especially at the construction site, is a significant risk factor for mucormycosis in COVID-19 care facilities where the ICU admitted patients with co-morbidities, who are already on steroid, IL6 inhibitor, and multiple antibiotics, are colonized initially by these spores. Subsequently, these spores germinate and result in localized/disseminated mucormycosis. As a consequence of angio-invasion, they result in black discolouration of the affected site.

This fungal infection has higher mortality, especially in untreated/delayed treatment conditions.[21] Thomas et al. in 2014 has reported 92% mortality in patients suffering from mucormycosis, which is reduced to 46% in patients having COVID associated mucormycosis, with 68% and 31% mortality in disseminated and cutaneous mucormycosis respectively.[22,23] Among the survivors, vision loss followed by facial deformity are the frequently encountered consequences of mucormycosis.[24] Thus; it is vital to have a high index of suspicion of mucormycosis in COVID 19/recovered patients. Therefore, this review will emphasise pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, lab diagnosis and management of mucormycosis.

Clinical Presentation

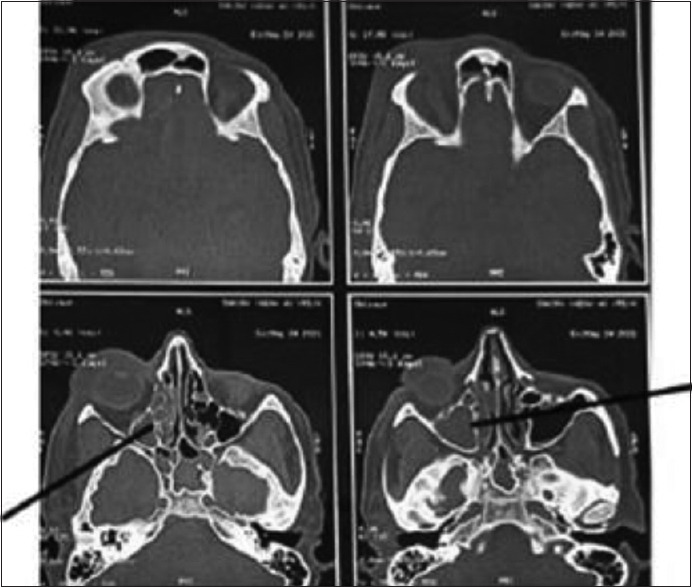

Mucormycosis presents itself as rhino-orbito-cerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, isolated renal and disseminated in the patients.[25,26] In rhinocerebral mucormycosis, facial pain, headache, brownish-blackish/blood-tinged nasal discharge is observed, whereas, in conditions with extension to surroundings, it presents as palatal ulcer, proptosis, periorbital swelling, and orbital pain [Figure 1]. CNS involvement primarily affects the frontal lobe and cerebellum where cranial nerve palsy, localized brain abscess, orbital apex syndrome can be observed later.[27,28]

Figure 1.

Black discolouration of the left cheek with left eye, left lip and left nasal cavity

In pulmonary mucormycosis, the patient usually complains of fever, cough with brown-coloured sputum, chest pain, breathlessness, and haemoptysis.[29] In cutaneous mucormycosis, clinical manifestations vary from pustule or vesicle to non-healing wound with necrotic edges. Sometimes, a cottony like growth is observed over the lesion surface (hairy pus).[30] In Gastrointestinal mucormycosis, the stomach is the primarily affected site, where ulceration of gastric mucosa with associated blood vessel thrombosis occurs.[31]

Diagnosis

The tissue necrosis resulting from angio-invasion is a classical feature of mucormycosis but, the other fungi, like Aspergillus, Lomentospora (Scedosporium), and Fusarium spp, also result in tissue necrosis.[32] In such cases, a joint approach is made by clinicians, histopathologist, microbiologist and radiologist. A high index of suspicion is needed for early diagnosis of mucormycosis in patients having multiple predisposing risk factors.[33] Endoscopy mediated nasal cavity examination, especially the middle turbinate and sinuses, may provide the initial evidence for mucormycosis. NCCT and MRI of the paranasal sinuses and orbit help to diagnose mucormycosis where the hyperinflamed densed sinus mucosa with bone erosion, including the periosteum, is observed [Figure 2].[34] These imaging techniques are essential to define the extent of the lesion. These clinic-radiological features provide a high index of suspicion for mucormycosis, whereas the diagnosis is confirmed by microbiological and histopathological examination. In cases of respiratory mucormycosis, reverse halo sign (RHS), multiple (≥10) nodules, pleural effusion, central necrosis, and air-crescent sign are observed on HRCT of the thorax.[35,36,37]

Figure 2.

CT axial images of skull showing ill defined soft tissue density noted filling right maxillary, ethmoid and sphenoid sinus with rarefaction of anterior and medial wall of maxillary sinus with mild right orbital bulge and periorbital swelling

Microbiological Examination

A microbiological examination is vital for early diagnosis of mucormycosis with identification of the causative pathogen. For this, the clinician should collect the nasal discharge, excised tissue by endoscopy or during surgery in the sterile universal container containing normal saline.[38] The clinicians should not use the swabs to collect nasal secretions/discharge as the cotton fibres interfere in the identification and cultivation of the pathogenic fungi. The collected specimen is never kept at a low temperature as the Mucorales does not survive at this temperature. The collected specimen is transported immediately to the Mycology lab, where the tissue samples are teased/cut into multiple small pieces.[39] Care must be taken while processing the sample as grinding and vortexing of the sample interfere in the viability of highly fragile hyphae of Mucorales. It is vital to select an appropriate portion of the sample for direct microscopic examination as Mucorales has a property of angioinvasion and perineural invasion.[40] Thus, the black-coloured area of the excised tissue is used for direct microscopic examination and cultivation [Figure 3]. Different diagnostic tools are being used to diagnose mucormycosis.[41]

Figure 3.

Excised tissue sample for microbiological investigation

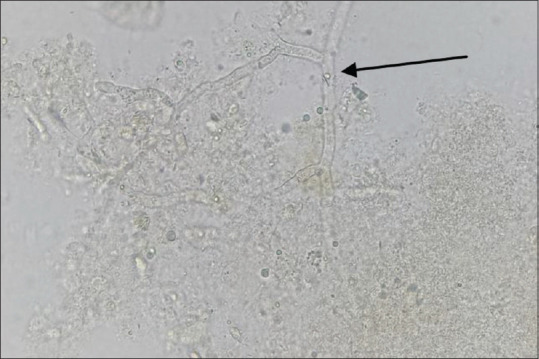

A) Potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mount:

It is a rapid presumptive test for diagnosing the fungal infection. A small piece of the excised tissue or BAL/sputum are kept in the 20% KOH, which dissolves the proteinaceous and other substances. We can fasten the process of dissolving by keeping the mount at 37°C. In KOH wet mount, the Mucorales hyphae reveal coenocytic broad aseptate/sparsely septate hyphae with right-angle branching resembling ribbon-like appearance [Figure 4]. It is essential to differentiate the Mucorales hyphae from the Aspergillus hyphae, which also causes rhinosinusitis and angioinvasion. Thin, septate, regular acute angle dichotomous branched hyaline hyphae of Aspergillus are observed in clinical samples. The sensitivity of KOH wet mount varied as the results on the direct wet mount are highly subjective. Therefore, it is essential to differentiate the fungal hyphae from artefacts, especially the cotton fibres.

Figure 4.

KOH wet mount of the excised tissue showing broad aseptate hyaline hyphae with right angle branching (Arrow), 400×

B) Calcofluor white (CFW) stain:

It is a non-specific fluorochrome dye used widely to diagnose fungal pathogens in clinical samples.[42] It binds specifically to the β 1-3, β1-4 glycoside chain of the chitin, an essential fungal cell wall component. Once the sample is stimulated with UV light in a fluorescent microscope, the fungal pathogen appears as the apple green or bluish against the white background, depending on the filter used. The addition of KOH in CFW stain increases the visibility of the fungal elements in clinical samples.[43] Care should be taken while examining the clinical samples, especially the cotton fibres; when present, they fluoresces as bluish as the CFW stain also bind the β 1-3, β1-4 glycoside of cellulose.

C) Culture:

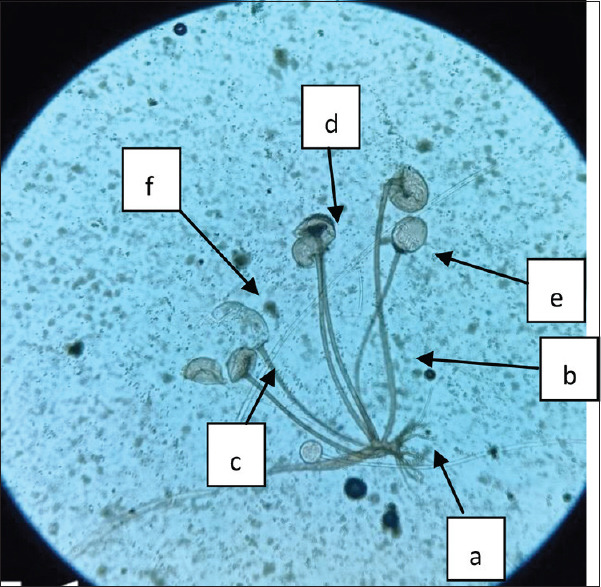

Culture is an essential diagnostic tool to determine the causative fungal pathogens with their antifungal susceptibility. Sabouraud’s Dextrose agar (SDA) is most widely used to cultivate the fungal pathogen. Briefly, the received sample is cut into multiple small pieces, directly inoculated over SDA and Potato dextrose agar (PDA) and incubated at 25°C in BOD. Mucorales grow rapidly at 25-37°C, where cottony fluffy growth is usually observed within 72hrs. The causative fungal pathogen is identified by standard mycological procedures including colony characteristics, morphological features on lactophenol cotton blue mount (LPCB), and growing at different temperature.[44] The following morphological characteristics; presence/absence of rhizoid, length and branching pattern of sporangiophore, apophysis, columella, collarette, the shape of the sporangium, size & shape of the sporangiospores, zygospore are observed on LPCB mount.[44] Care should be taken while reporting the cultivated fungi as it may be due to contamination. In such cases, other supporting tests aid in the diagnosis.

The primary concern about the culture is its low sensitivity, as in more than 50% of mucormycosis cases, usually, there is no growth. This low culture positivity may be attributed to different factors ranging from sample collection, storage to sample processing. The storage of samples at 4°C affects the viability of Mucorales. The tissue sample processing, including grinding or homogenization, also affects the viability of these fungal pathogens. However, good communication between the clinician and diagnostic laboratories can easily overcome these issues.

Rhizopus arrhizus (R. oryzae) is the predominant cause of mucormycosis. It rapidly grows at room temperature on SDA medium, where cottony fluffy growth with black dots, resembling salt-paper, is observed [Figure 5]. On LPCB wet mount well-developed rhizoid, opposite to long unbranched sporangiophores, with apophysis, collarette, hemispherical columella and globose hyaline-dark brown sporangium having numerous striated sporangiospores are observed [Figure 6].

Figure 5.

Cottony-fluffy growth of Rhizopus arrhizus on SDA agar

Figure 6.

LPCB wet mount showing Rhizoid (a), sporangiophore (b), Apophysis (c), columella (d), collarets (e), sporangium (f), 400×

D) Molecular methods:

These methods are widely used to diagnose mucormycosis from clinical samples and to identify the causative pathogen from the growth. Different molecular methods, semi-nested PCR, nested PCR with RFLP, real Time PCR targeting the ITS region or specific primers targeting a restricted number of mucoralean genera/species, are being used to diagnose mucormycosis.[45] Among these, the 18S ribosomal RNA gene is the most common target, but others; 28S rDNA, the mitochondrial gene rnl, the cytochrome b gene or the Mucorales-specific CotH gene are also being targeted.[46] Once the targeted region is amplified, it is sequenced to determine the causative fungal pathogen. These molecular methods aid the diagnosis where the fungal load is low and the conditions where other diagnostic tools fail. Care should be taken while interpreting the results of molecular-based diagnostic tools as they don’t differentiate between the actual pathogen/colonization or contamination.

Amplification of different target genes may generate varied results for mucormycosis as Zaman et al. has reported that only 54% (27/54) of the ROCM cases were confirmed by ITS2 amplification with subsequent sequencing. In contrast, Mucorales-specific PCR amplified DNA in all 50 samples, subsequently identified as Mucorales species.[47] This difference may be due to the amplification of all fungal elements present in clinical samples, as ITS 2 is present in all fungal species. It probably generated the sequence of all fungi present in clinical samples during amplification, resulting in a non-specific sequence. In contrast, amplification of Mucorales-specific PCR DNA results in the only generation of Mucorales specific products. Thus selecting a panfungal target in non-sterile sites may result in the identification of non-specific fungi, which can be easily overcome by selecting a specific target. Currently, real-time quantitative PCR targeting ITS1/ITS2 region with specific probes for R. arrhizus, R. microsporus, and Mucor spp., qPCR with specific primers targeting cytochrome b gene, 28S rDNA are also being used to diagnose the causative Mucorales in fresh/FFPE tissues.

E) Histopathological examination:

Histopathological examination of the excised tissue is essential to determine the tissue reactions and the causative fungal pathogens.[48,49] For this, the excised tissue is to be sent in a sterile container having 10% formalin, which preserves the tissue’s architecture. Initially, a gross examination of the excised tissue is done subsequently, it is cut into multiple small pieces which undergo paraffin embedding through dehydration, clearing and infiltration. Subsequently, the embedded paraffin block is cut into multiple 4-5 micrometre thickness parts, stained by Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining.

On microscopic examination, tissues from the suspected case of mucormycosis show necrosis, inflammatory infiltrate rich in neutrophils and fungal hyphae. The fungal hyphae appear basophilic one, broad, aseptate and show right-angle branching. The fungal hyphae are well observed on the H and E stained section; however, special stains like PAS and GMS can be done if required. Sometimes granuloma, angioinvasion or perineural invasion can be seen in tissue samples.

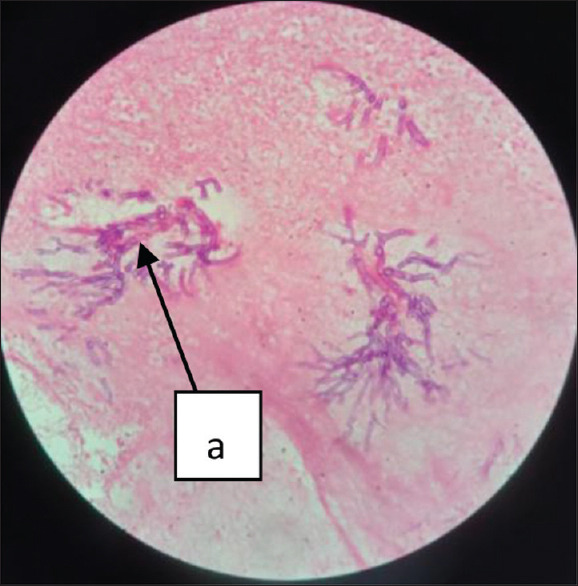

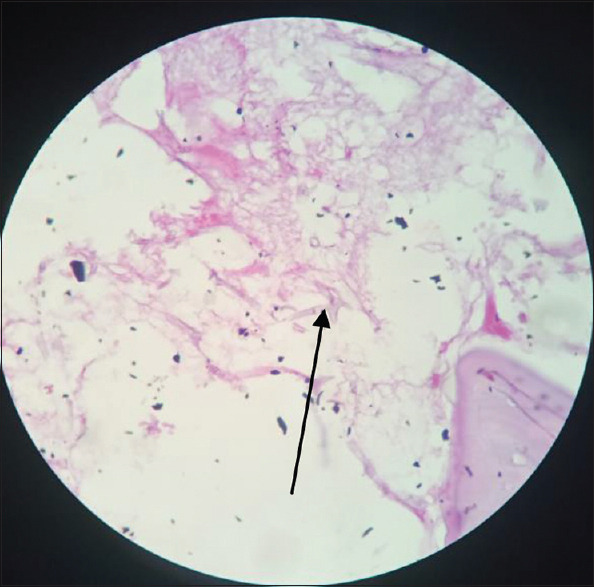

F) Hematoxylin and Eosin staining:

H& E staining is most widely used for histopathological examination. It is a combination of two dyes, Hematoxylin and Eosin. In the presence of mordant, aluminium salts, Hematoxylin, a basic dye, stains the nucleus purple, whereas Eosin, an acidic dye, stains the cytoplasm pink. It demonstrates the inflammatory response against fungal pathogens by identifying hyaline/phaeoid fungi [Figure 7]. The major drawback of this staining is that it fails to detect fungal pathogens when they are sparsely present. While interpreting the staining, it is also difficult to distinguish the fungal element from the small blood vessels in CNS and lung tissues.

Figure 7.

H and E staining of the excised tissue showing the necrosis (a) with plenty of broad aseptate hyphae (arrow), 400×

G) Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) staining:

PAS staining detects the carbohydrate component of the fungal cell wall, rich in β 1-3, β 1-4 D-glucan. The periodic acid results in the oxidation of carbohydrate components into the aldehyde, which is detected by the addition of Schiff reagent, where the fungal elements reveal as red or pink or magenta. [Figure 8]. The protein and nucleic acid remain unstained.

Figure 8.

Pink coloured aseptate fungal hyphae (arrow), 400×

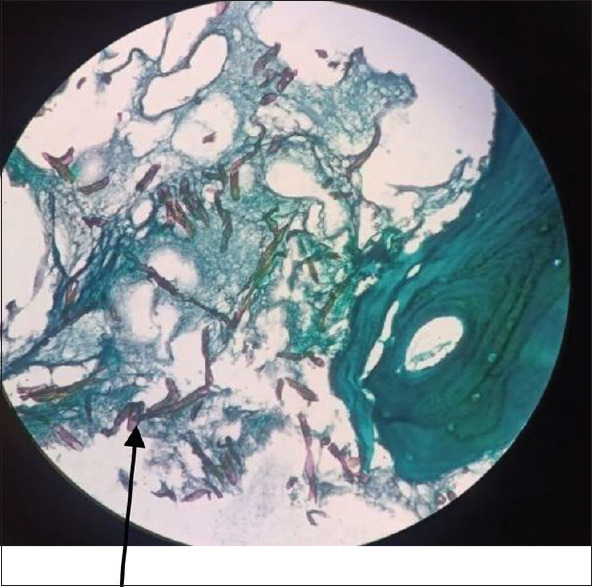

H) Grocott-Gomori’s Methenamine Silver staining (GMS) staining:

GMS is a unique stain used to detect the fungal element in the clinical samples. It is considered to be best as it provides better contrast for screening. Compared to PAS, it also stains the old and non-viable fungal organisms in tissue samples. GMS staining also detects the carbohydrate (glucan) component of the fungal cell wall, which appears dark and black coloured [Figure 9]. It also stains the filamentous bacteria, Actinomycetes & Nocardia. The major drawback of this staining is that it may overstain the fungi, which can obscure the internal structures. The GMS stain also does not properly study the host response to fungal infection.

Figure 9.

Dark brown-black coloured aspetate fungal hyphae (arrow), 400×

I) Serological test:

Galactomannan and β-D glucan tests are widely used to diagnose fungal infection. This β-D glucan test is considered a panfungal antigen test except for the Mucormycosis and cryptococcosis, whereas the Galactomannan test is specific for the Aspergillosis.[50,51] These tests have higher negative predictive value as false-positive galactomannan, and β-D glucan antigen can be observed in various settings. Similarly, the positive galactomannan and β-D glucan test exclude the mucormycosis diagnosis. Presently, ELISA testing targeting the serum R. arrhhizus, Rhizomucor pusillus antibody, western immunoblotting targeting R. arrhhizus antigen, Cytoplasm, hyphae walls and septate, of R. arrhizus WSSA are available for diagnosis of Mucormycosis.[52,53,54] Recently, ELISA (ELISpot) or immunocytofluorimetric assay targeting Mucorales specific IFN-γ-producing T cells have been assessed.[55] In 2017, Kanako Sato et al. have reported the unique protein antigen, protein RSA of 23 kDa, in the serum and lung homogenates of R.arrhizus infected mice compared to uninfected mice.[56]

The diagnosis of Mucormycosis by a serological test is a challenging task as human beings are frequently exposed to the Mucorales spores, resulting in antibody titre. The sensitized T lymphocyte may be an essential tool in diagnosing mucormycosis. Again, it is not easy to distinguish between the colonization and true Mucorale pathogen as these spores readily colonise the non-sterile body site.

J) Treatment:

A high index of suspicion is to be kept in each case of mucormycosis as these cases have higher mortality and severe morbidity among survivors. Mucormycosis cases are managed by extensive surgery, reversal of the predisposing risk factors, and early administration of antifungal drugs in appropriate doses.[57] Extensive surgery of the affected region is the primary treatment. The delay in surgery results in a bad prognosis. Amphotericin B is considered a drug of choice where the liposomal form is given to prevent nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity.[58,59] These Mucorales are usually resistant to fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole; in such conditions, posaconazole and isavuconazole are used as supportive/salvage therapy.

Strict glycemic control is required to manage mucormycosis, which is achieved by appropriate insulin dosing. Sodium bicarbonate can be used to neutralize the ketoacidosis.[60] However; all these measures may result in electrolyte imbalance, which needs to be corrected immediately.

Conclusion

Mucormycosis cases have higher morbidity and mortality among survivors. Therefore, the primary care physicians should have a high index of suspicion in patients presenting with blackish nasal discharge, and sinus pain as better prognosis has been reported in patients presenting in the early stages of infections. Thus, in the background history of diabetes and immunosuppressed states, prompt diagnosis with integrated team management can reduce the morbidity and mortality among the patients suffering from mucormycosis.

Key message

The primary care physician should have a high index of suspicion for mucormycosis in patients with uncontrolled diabetes, presenting as blackish nasal discharge or facial pain.

Prompt diagnosis of mucormycosis can be made by KOH wet mount of the excised tissue.

Mucormycosis cases should be managed by multidisplinary team comprising otorhinolaryngologist, ophthalmologist, physicians, radiologist and microbiologist.

The Black fungus, a clinical terminology of mucormycosis, is not an appropriate synonym as the causative fungal pathogens are hyaline.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We are sincerely thankful to the members of the COVID19 associated Fungal study group, IMS BHU for their kind support.

References

- 1.Hibbett DS, Binder M, Bischoff JF, Blackwell M, Cannon PF, Eriksson OE, et al. A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi. Mycol Res. 2007;111:509–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatt K, Agolli A, Patel MH, Garimella R, Devi M, Garcia E, et al. High mortality co-infections of COVID-19 patients:Mucormycosis and other fungal infections. Discoveries. 2021;9:e126. doi: 10.15190/d.2021.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong W, Keighley C, Wolfe R, Lee WL, Slavin MA, Kong DC, et al. The epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis:A systematic review and meta-analysis of case reports. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:236–301. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.236-301.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson M. The ecology of the Zygomycetes and its impact on environmental exposure. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugar AM. Agents of mucormycosis and related species. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2005. p. 2979. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibrahim AS, Edwards JE, Filler SG. Zygomycosis. In: Dismukes WE, Pappas PG, Sobel JD, editors. Clinical Mycology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 241–51. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakrabarti A, Das A, Mandal J, Shivaprakash MR, George VK, Tarai B, et al. The rising trend of invasive zygomycosis in patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Sabouraudia. 2006;44:335–42. doi: 10.1080/13693780500464930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakrabarti A, Chatterjee SS, Das A, Panda N, Shivaprakash MR, Kaur A, et al. Invasive zygomycosis in India:experience in a tertiary care hospital. Postgr Med J. 2009;85:573–81. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.076463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhanuprasad K, Manesh A, Devasagayam E, Varghese L, Cherian LM, Kurien R, et al. Risk factors associated with the mucormycosis epidemic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;111:267–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pak J, Tucci VT, Vincent AL, Sandin RL, Greene JN. Mucormycosis in immunochallenged patients. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2008;1:106–13. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.42203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skiada A, Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Petrikkos G, Katsambas A. Global epidemiology of cutaneous zygomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:628–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raut A, Huy NT. Rising incidence of mucormycosis in patients with COVID-19:Another challenge for India amidst the second wave? Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:e77. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00265-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Breakthrough invasive mold infections in the hematology patient:Current concepts and future directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1621–30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marty FM, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Cornely OA, Mullane KM, Perfect JR, Thompson GR, III, et al. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis:A single-arm open-label trial and case-control analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:828–37. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Artis WM, Fountain JA, Delcher HK, Jones HE. A mechanism of susceptibility to mucormycosis in diabetic ketoacidosis:Transferrin and iron availability. Diabetes. 1982;31:1109–14. doi: 10.2337/diacare.31.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morales-Franco B, Nava-Villalba M, Medina-Guerrero EO, Sánchez-Nuño YA, Davila-Villa P, Anaya-Ambriz EJ, et al. Host-pathogen molecular factors contribute to the pathogenesis of Rhizopus spp. in diabetes mellitus. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2021;8:6–17. doi: 10.1007/s40475-020-00222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.John TM, Jacob CN, Kontoyiannis DP. When uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and severe COVID-19 converge:the perfect storm for mucormycosis. J Fungi. 2021;7:298. doi: 10.3390/jof7040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldin C, Ibrahim AS. Molecular mechanisms of mucormycosis—the bitter and the sweet. PLoS Pathogens. 2017;13:e1006408. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bitar D, Cauteren DV, Lanternier F, Dannaoui E, Che D, Dromer F, et al. Increasing incidence of zygomycosis (mucormycosis), France, 1997–2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1395–401. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li DM, Lun LD. Mucor irregularis infection and lethal midline granuloma:A case report and review of published literature. Mycopathologia. 2012;174:429–39. doi: 10.1007/s11046-012-9559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell TA, Hardin MO, Murray CK, Ritchie JD, Cancio LC, Renz EM, et al. Mucormycosis attributed mortality:A seven-year review of surgical and medical management. Burns. 2014;40:1689–95. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Available from: https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)/mucormycosis .

- 24.Patel A, Agarwal R, Rudramurthy SM, Shevkani M, Xess I, Sharma R, et al. Multicenter epidemiologic study of coronavirus disease-associated mucormycosis, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:2349–59. doi: 10.3201/eid2709.210934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis:A review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634–53. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandey V, Gupta MK. An unusual case of renal fungal mass masquerading as renal cell carcinoma. Indian J Med Res. 2020;152:S173–4. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2269_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, Roilides E, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54((suppl_1)):S23–34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corzo-León DE, Chora-Hernández LD, Rodríguez-Zulueta AP, Walsh TJ. Diabetes mellitus as the major risk factor for mucormycosis in Mexico:Epidemiology, diagnosis, and outcomes of reported cases. Med Mycol. 2018;56:29–43. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin E, Moua T, Limper AH. Pulmonary mucormycosis:Clinical features and outcomes. Infection. 2017;45:443–8. doi: 10.1007/s15010-017-0991-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castrejón-Pérez AD, Welsh EC, Miranda I, Ocampo-Candiani J, Welsh O. Cutaneous mucormycosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:304–11. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spellberg B. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis:An evolving disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8:140–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai CC, Yu WL. COVID-19 associated with pulmonary aspergillosis:A literature review. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sen M, Lahane S, Lahane TP, Parekh R, Honavar SG. Mucor in a viral land:A tale of two pathogens. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:244–52. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3774_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Therakathu J, Prabhu S, Irodi A, Sudhakar SV, Yadav VK, Rupa V. Imaging features of rhinocerebral mucormycosis:A study of 43 patients. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2018;49:447–52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Georgiadou SP, Sipsas NV, Marom EM, Kontoyiannis DP. The diagnostic value of halo and reversed halo signs for invasive mold infections in compromised hosts. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1144–55. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Legouge C, Caillot D, Chrétien ML, Lafon I, Ferrant E, Audia S, et al. The reversed halo sign:Pathognomonic pattern of pulmonary mucormycosis in leukemic patients with neutropenia? Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:672–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chamilos G, Marom EM, Lewis RE, Lionakis MS, Kontoyiannis DP. Predictors of pulmonary zygomycosis versus invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:60–6. doi: 10.1086/430710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lass-Flörl C. Zygomycosis:Conventional laboratory diagnosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;5:60–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chander J. In: Fungal reagents and stainings. Textbook of Medical Mycology. 3rd ed. Chander J, editor. New Delhi: Mehta; 2009. pp. 514–21. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galletta K, Alafaci C, D'Alcontres FS, Maria ME, Cavallaro M, Ricciardello G, et al. Imaging features of perineural and perivascular spread in rapidly progressive rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis:A case report and brief review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2021;12:245. doi: 10.25259/SNI_275_2021. doi:10.25259/SNI_275_2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walsh TJ, Gamaletsou MN, McGinnis MR, Hayden RT, Kontoyiannis DP. Early clinical and laboratory diagnosis of invasive pulmonary, extrapulmonary and disseminated mucormycosis (zygomycosis) Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:S55–60. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monheit JE, Cowan DF, Moore DG. Rapid detection of fungi in tissues using calcofluor white and fluorescence microscopy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:616–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta M, Chandra A, Prakash P, Banerjee T, Maurya OP, Tilak R. Fungal keratitis in north India;Spectrum and diagnosis by Calcofluor white stain. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33:462–2. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.158609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de hoog GS, Guarro J, Gene× J, Figueras MJ. Eumycota, zygomycota:Explanatory Chapter and key to the genera. In:Atlas of Clinical Fungi. (2nd ed) 2000:58–124. Centralbureau Voor Schimmelcultures, Universitat I Virgili. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machouart M, Larche J, Burton K, Collomb J, Maurer P, Cintrat A, et al. Genetic identification of the×main opportunistic mucorales by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:805–10. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.805-810.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Springer J, Lackner M, Ensinger C, Risslegger B, Morton CO, Nachbaur D, et al. Clinical evaluation of a Mucorales-specific real-time PCR assay in tissue and serum samples. J Med Microbiol. 2016;65:1414–21. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zaman K, Rudramurthy SM, Das A, Panda N, Honnavar P, Kaur H, et al. Molecular diagnosis of rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis from fresh tissue samples. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66:1124–9. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gamble M. The hematoxylin and eosin. In: Bancroft DJ, Gamble M, editors. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 6th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 121–3. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartlett JH. Microorganisms. In: Bancroft DJ, Gamble M, editors. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 6th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2008. p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Son HJ, Sung H, Park SY, Kim T, Lee HJ, Kim SM, et al. Diagnostic performance of the (1–3)-?-D-glucan assay in patients with Pneumocystis jirovecii compared with those with candidiasis, aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and tuberculosis, and healthy volunteers. PloS One. 2017;12:e0188860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dichtl K, Forster J, Ormanns S, Horns H, Suerbaum S, Seybold U, et al. Comparison of ?-D-Glucan and galactomannan in serum for detection of invasive aspergillosis:Retrospective analysis with focus on early diagnosis. J Fungi. 2020;6:253. doi: 10.3390/jof6040253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandven PER, Eduard W. Detection and quantitation of antibodies against Rhizopus by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. APMIS. 1992;100:981–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1992.tb04029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wysong DR, Waldorf AR. Electrophoretic and immunoblot analyses of Rhizopus arrhizus antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:358–63. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.2.358-363.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones KW, Kaufman L. Development and evaluation of an immunodiffusion test for diagnosis of systemic zygomycosis (mucormycosis):Preliminary report. Clin Microbiol. 1978;7:97–101. doi: 10.1128/jcm.7.1.97-101.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Potenza L, Vallerini D, Barozzi P, Riva G, Forghieri F, Zanetti E, et al. Mucorales-specific T cells emerge in the course of invasive mucormycosis and may be used as a surrogate diagnostic marker in high-risk patients. Blood. 2011;118:5416–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-366526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sato K, Oinuma KI, Niki M, Yamagoe S, Miyazaki Y, Asai K, et al. Identification of a novel rhizopus-specific antigen by screening with a signal sequence trap and evaluation as a possible diagnostic marker of mucormycosis. Med Mycol. 2017;55:713–9. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myw146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cornely O, Arikan-Akdagli SE, Dannaoui E, Groll AH, Lagrou K, Chakrabarti A, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis 2013. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:5–26. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gebremariam T, Gu Y, Singh S, Kitt TM, Ibrahim AS. Combination treatment of liposomal amphotericin B and isavuconazole is synergistic in treating experimental mucormycosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76:2636–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Delaying amphotericin B-based frontline therapy significantly increases mortality among patients with hematologic malignancy who have zygomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:503–9. doi: 10.1086/590004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alqarihi A, Gebremariam T, Gu Y, Swidergall M, Alkhazraji S, Soliman SS, et al. GRP78 and integrins play different roles in host cell invasion during mucormycosis. Mbio. 2020;11:e01087–20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01087-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]