Summary

Autoimmune diseases are characterized by dysfunctional immune systems that misrecognize self as non-self and cause tissue destruction. Several cell types have been implicated in triggering and sustaining disease. Due to a strong association of major histocompatibility complex II (MHC-II) proteins with various autoimmune diseases, CD4+ T lymphocytes have been thoroughly investigated for their roles in dictating disease course. CD4+ T cell activation is a coordinated process that requires three distinct signals: Signal 1, which is mediated by antigen recognition on MHC-II molecules; Signal 2, which boosts signal 1 in a costimulatory manner; and Signal 3, which helps to differentiate the activated cells into functionally relevant subsets. These signals are disrupted during autoimmunity and prompt CD4+ T cells to break tolerance. Herein, we review our current understanding of how each of the three signals plays a role in three different autoimmune diseases and highlight the genetic polymorphisms that predispose individuals to autoimmunity. We also discuss the drawbacks of existing therapies and how they can be addressed to achieve lasting tolerance in patients.

Keywords: TCR, MHC, costimulation, coinhibition, cytokines

1. Introduction

A fundamental feature of the immune system is its unique ability to sufficiently distinguish self from non-self to prevent aberrant infection and colonization. The plethora of pathogens that exist can rapidly outmaneuver immune responses, as evidenced the ongoing global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2. Consequently, immune cells exist in a poised state to ensure rapid clearance of any infectious agent. However, maintaining this cell state requires exquisite control over immune cell activity and function to avoid unwarranted responses directed towards self. In autoimmune diseases, this tolerance to self is perturbed, leading to inappropriate activation of the immune system and subsequent tissue-specific or system immune cell infiltration and culminating in tissue destruction (1).

Currently, more than 80 different autoimmune diseases have been identified in humans (2). Each of these has its own etiology that involves different genetic predispositions, cell populations, tissues and environmental triggers. Common autoimmune diseases include type 1 diabetes (T1D), in which the pancreas is targeted; multiple sclerosis (MS), in which the central nervous system (CNS) is targeted; and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), in which the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is targeted. Frequently, such autoimmune diseases involve a loss in T cell tolerance and inappropriate activation of autoreactive T cells as evidenced by elevated numbers of such cells in tissues. Dampening T cell function is often implemented in patients to treat and manage disease (2).

T cell activation requires three signals – antigen recognition (Signal 1) initiated by the T cell antigen receptor (TCR) recognizing its cognate antigen on a given cell, costimulation (Signal 2), in which costimulatory/coinhibitory molecules are engaged and activated to boost or inhibit Signal 1 and cytokine-mediated differentiation (Signal 3), which directs T cell survival and differentiation into functional subsets (3). In the absence of any of these three signals, T cells are not properly activated, resulting in either unresponsive T cells (4) or reduced survival of T cells (5). In autoimmunity, however, dysregulation of each of these signaling pathways, either in isolation or in combination, has been reported to affect T cell activation (2, 6, 7). Additionally, subsequent T cell infiltration and effector responses resulting in chronic inflammation in tissues is further regulated by these signals in tissue sites themselves. Here, we review how these fundamental T cell activation pathways are perturbed in CD4+ T cells during autoimmune disease progression, with a focus on T1D, MS and IBD.

2. Signal 1 – TCR-Mediated Peptide-MHC Recognition by T cells

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules non-covalently interacting with linear peptide fragments are tethered to surfaces of antigen presenting cells (APCs) and serve as the primary ligands recognized by TCRs on T cells (8). Cognate TCRs recognizing a specific peptide/MHC (pMHC) complex presented by APCs can transduce activating signals to T cells. The peptides themselves are proteolytic byproducts that bind to the peptide binding groove of the MHC proteins during their assembly (9). In this manner, MHC molecules provide an overview of the proteins that are expressed within a cell, thereby allowing T cells to survey the landscape for any perturbations. Broadly speaking, MHC-I proteins that present intracellular peptides and MHC-II proteins that present peptides originating from extracellular proteins captured via the endocytic pathway (10). Through this division of labor, MHC molecules have evolved means to alert T cells to the presence of both extracellular and intracellular pathogens (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

MHC-II alleles and peptides contributing to altered Signal 1 in autoimmune diseases. A. Antigen presenting cells (APCs) express MHC-II molecules complexed with linear peptide fragments in antigen-binding pockets. CD4+ T cells bear αβ TCRs with the capacity to recognize the peptide/MHC-II complexes. Upon antigen recognition, the CD3 signaling subunits (γ, δ, ε, ζ) transduce signals that culminate in T cell activation. B. The known MHC-II risk alleles for type 1 diabetes (T1D), multiple sclerosis (MS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are listed for both humans and mice. C. The known self-antigens reported to be targeted in T1D, MS and IBD are listed. The references for the studies in which these antigens were identified are provided parenthetically. Abbreviations, ChgA – chromogranin A, GAD65 – glutamic acid decarboxylase, GRP78 - glucose-regulated protein 78, HIPs – hybrid insulin peptides, IA-2 – islet tyrosine phosphatase 2, IAPP – islet amyloid polypeptide, IGRP – islet-specific glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit-related protein, ZnT8 – zinc transporter 8, CNPase – 2’,3’-cyclic-nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase, MAG – myelin-associated antigen, MBP – myelin basic protein, MOBP – myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein, MOG – myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, PLP – proteolipid protein, S100β – S100 calcium-binding protein B, HH_1713 – a Helicobacter hepaticus-unique protein. This image was created with BioRender.com.

Although structurally and functionally similar, a few key differences exist between MHC-I and MHC-II proteins. While MHC-I molecules are expressed by all nucleated cells, MHC-II proteins are expressed only by certain populations at steady-state, the so-called ‘professional’ APCs (APCs) consisting of B cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and macrophages, at steady-state (8). Additionally, while the ligand-binding pocket in MHC-I molecules is formed by one polypeptide, the same pocket in MHC-II molecules is formed by two distinct polypeptides that form a heterodimer. Lastly, due to the closed ends of their peptide binding grooves, MHC-I molecules chiefly present peptides of 8–10 residues (11, 12). MHC-II molecules, though, possess open-ended grooves that allow presentation of longer peptides, with the peptide termini extending beyond the ends of the groove (13). Peptides bound in this extended conformation to MHC-II interact with the groove by forming conserved hydrogen bonds between the peptide backbone and MHC-II residues (14). As the MHC-II interactions occur with the peptide backbone and not its side chains, the bound peptides can shift in the groove while still maintaining their hydrogen bonds (15). Consequently, the same peptide can be recognized in distinct manners by different TCRs depending on the register in which it is bound to MHC-II (16).

Two α-helices and a β-pleated sheet form the sides and the floor of the MHC antigen binding groove, respectively (8). Residues within this pocket dictate which peptides can bind with sufficient affinity to create a stable complex that can be recognized by TCRs. Interestingly, the genes coding for MHC proteins are among the most polymorphic known (17). These polymorphisms are concentrated in the regions that code for the residues in the antigen binding cleft, which results in different MHC alleles displaying distinct peptide-binding biases that in turn impart greater susceptibility to or protection against pathogenic threats to the host (9). Another notable consequence of these polymorphisms is that certain MHC alleles have been linked to greater incidences of autoimmune diseases (2).

Adding to this complexity is the fact that the bound peptides exert their own potency in dictating the T cell response. In some cases, the immunogenic self-peptides are not always those against which T cells are effectively tolerized. Although, positive and negative selection in the thymus ensure that the T cells entering the periphery do not display strong reactivities to self-peptides, these peptides do not completely sample the antigenic space. Altered self-antigens in peripheral tissues are presented as neoantigens against which the T cells can mount an immune response due to incomplete tolerization (15, 18). In other cases, certain viral or bacterial peptides presented during an infection bear sufficient similarities to host self-peptides that the T cell response is misdirected to target host tissues and initiate the autoimmune cascade (19). Overall, both the peptides and the MHC molecules play critical roles in pushing T cells to break tolerance in various autoimmune diseases.

From the T cell perspective, the TCR is a protein that harbors extraordinary diversity with the capacity to recognize the entire universe of peptide-MHC complexes (20). The TCR heterodimer is composed of an α- and a β-chain and recognizes antigens using three flexible loops called complementarity determining regions (CDRs) on each chain (21). The CDR1 and CDR2 loops are coded within the variable (V) genes for each chain and have been shown to interact with the α-helices that form the peptide binding grooves of MHC molecules. The TCR diversity, though, is largely restricted to the CDR3 of each chain, which is produced via a coordinated series of somatic rearrangements. The CDR3 loops fixate on the MHC-bound peptide to ensure that the most diverse part of the TCR engages the most diverse part of the ligand (22). Antigen recognition results in conformational changes and subsequent intracellular signal transduction.

The TCR heterodimer itself has no signaling capacity. Instead, it is associated with a complex of proteins that cluster with the TCR and initiate the signaling cascade (23). The affinity of the TCR for its cognate peptide-MHC ligand determines the strength of the intracellular signal that is transmitted. High affinity interactions promote strong and lasting T cell activation with improved T cell fitness (24). Alternatively, high concentrations of cognate peptides presented by APCs can overcome the threshold required for T cell activation due to increased TCR avidity (25) (Figure 2). Thus, during autoimmunity, T cells bearing self-reactive TCRs with low to moderate affinities for their target peptides can be atypically activated and mediate disease in environments where cognate peptide concentrations are high (26, 27).

Figure 2.

High antigen concentration in the periphery can overcome poor MHC-II binding. Left, Numerous self-antigens are presented in the thymus by thymic APCs but due to their low availability, any given peptide/MHC complex is not presented at high levels. Self-peptides that bind to MHC molecules with low affinities are further underrepresented, allowing any developing T cell with cognate specificity to mature and not undergo clonal deletion. Right, In peripheral tissues, the low affinity self-peptides could be available at high concentrations, which could promote enhanced presentation of these peptides due to their increased proportional sampling. Low affinity interactions could, therefore, be overcome by higher avidity antigen presentation, which leads to activation of autoreactive T cells. This image was created with BioRender.com.

2.1. Type I Diabetes

T1D is characterized by T cell infiltration into the pancreatic islets culminating in the destruction of insulin-producing β cells (28). A strong disease association with certain MHC-II alleles implicates a more principal role for CD4+ T cells in T1D (29–31). Indeed, CD4+ T cells potentiate the production of insulin-specific autoantibodies by B cells, a key feature of T1D (32). In addition, activated CD4+ T cells promote inflammatory macrophage and neutrophil infiltration into the islets, which cause further depletion of β cells (33–35).

About 90% of patients diagnosed with T1D have been reported to carry the HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 haplotypes (36, 37) (Figure 1B). One principal element shared by these strong T1D-associated MHC-II alleles is a polymorphism at position 57 in the HLA-DQβ chain (29, 38). While most other MHC-II alleles possess an aspartic acid residue at this position, the disease-associated alleles possess a non-aspartic acid residue instead. Indeed, the widely used non-obese diabetic (NOD) spontaneous diabetes mouse model also possesses a non-aspartic acid at this position in its MHC-II allele (I-Ag7) (39, 40). β57 aspartic acid normally forms a salt bridge with an arginine residue (R76) in the DQα (or I-Aα in mouse) chain (41, 42) and in its absence, the αR76 uniquely shapes the peptide repertoire bound to the MHC-II alleles by preferentially selecting for peptides containing acidic residues at the P9 position (43, 44). As a result, MHC-II alleles with this position 57 polymorphism bind to peptides with significantly lower affinities than those with the canonical aspartic acid (45). Reduced peptide affinity to MHC-II has been proposed as a possible mechanism for how self-reactive T cells can avoid clonal deletion during thymic central tolerance (46). Self-peptides are poorly presented during thymic selection but their abundance in the target tissues allows autoreactive T cells to overcome the weak presentation and become activated.

Such inferior peptide binding to the T1D-associated MHC-II alleles could be linked to poor Class II-associated invariant chain peptide (CLIP) binding to the MHC-II groove as well. CLIP is the peptide derived from invariant chain (CD74) that prevents aberrant peptide binding to MHC-II proteins after their assembly in the ER. It is released in the late endosomes by HLA-DM (H-2DM in mice), thereby allowing peptide exchange to occur for proper antigen presentation. Previous work, however, has demonstrated that CLIP binding affinity to MHC-II varies in an MHC-allele-specific manner based on the polymorphic residues lining the binding pocket (47). For the non-βD57 containing HLA-DQ2, HLA-DQ8 and I-Ag7 alleles, the positively charged pocket lowers the CLIP binding affinity, resulting in low affinity peptides loaded onto MHC-II that were not edited by HLA-DM (48–50).

Recent work has further supported the hypothesis that poor CLIP binding to these T1D-associated MHC-II alleles could contribute to T1D progression. The Wucherpfennig lab generated a knock-in NOD mouse in which a CLIP mutation was introduced to increase its affinity for I-Ag7 (51). Mice carrying this mutation were reported to have a lower incidence of T1D compared to their WT counterparts. Additionally, fewer antigen-specific T cells infiltrating the islets were observed in these knock-in mice. Strikingly, while APCs from mutant mice could process proteins and subsequently present peptides to T cells as efficiently as those from WT mice, they inefficiently presented soluble peptides to T cells compared to WT APCs (51). Therefore, increasing CLIP affinity to MHC-II prevented premature peptide loading and ensured that H2-DM could promote binding of high affinity peptides, which subsequently hampered soluble peptide exchange at cell surfaces. Consequently, diabetogenic self-peptides were bound to I-Ag7 less frequently, resulting in reduced T cell priming and islet infiltration.

Numerous other MHC risk alleles have been identified in humans that have been linked to increased susceptibility of T1D (30). Furthermore, some MHC-I alleles have also been associated with a greater predisposition to develop T1D (52). Indeed, high numbers of islet invading CD8+ T cells have been observed in T1D patients (53, 54). This observation correlates with experiments performed in mice which concluded that CD8+ T cells and MHC-I molecules are critical for T1D development (55–57). Yet, the precise molecular biases that impact disease development for these risk alleles have not been identified and should be thoroughly investigated in the future.

Although all APCs have been shown to contribute to disease development, B cells in particular have been repeatedly demonstrated to be necessary for T1D. Mice lacking B cells are protected from T1D (58, 59), while human T1D patients in whom B cells are selectively depleted display improved β cell function (60). Autoreactive B cells, which make up to 75% of the immature B cell repertoire (61), have the potential to capture protein antigens and process/present peptides to cognate self-reactive T cells (62). In their absence, the CD4+ and CD8+ effector T cell populations are suppressed and the remaining DCs and macrophages instead promote a more regulatory landscape (63), further implicating B cells in promoting T cell-mediated β cell destruction. Overall, this highlights that even though all APCs express the same MHC alleles, the cell type activating T cells can have drastic consequences for the disease course.

The antigens specifically recognized by T cells make up the final piece of the ligand presented by APCs that helps to trigger Signal 1 in T cells. Many self-antigens, such as insulin, chromogranin A, GAD65, IGRP and ZnT8, for example, have been identified as targets in T1D (64–71) (Figure 1C). However, it remained unclear why autoreactive T cells targeted these antigens despite having undergone central tolerance in the thymus. For example, one oft-targeted peptide in T1D in both humans and mice is the insulin β-chain fragment B:9–23 (15, 44). Yet, the specific register bound in the MHC-II groove had been unknown and complicated by the I-Ag7 β57 polymorphism. Extensive work by the Kappler and Unanue groups has revealed that this peptide is likely generated in the β cells themselves, which may employ distinct proteases and generate peptides with termini different from those observed in APCs (72–74). This peptide is subsequently loaded onto I-Ag7 via peptide exchange at the cell surfaces of APCs such as DCs, which then prime T cells. Furthermore, structural and functional data indicate that due to its C-terminal truncation, the bound peptide does not occupy the C-terminal end of the I-Ag7 groove (15, 74, 75), allowing it to perhaps engage the MHC molecule with higher affinity than that of the peptide generated by the proteases in APCs. Altogether, these results hint at how T cells exposed to the same peptide in the thymus escape negative selection while simultaneously getting activated in the pancreas (Figure 2).

In addition, several recent studies have provided strong evidence for a novel mechanism instigating a break in tolerance in T1D. In a process termed transpeptidation, noncontiguous peptides are fused in the lysosomes of β cells (67, 76). As proteins are degraded in these vesicles, the N-terminus of one peptide can form a peptide bond with the C-terminus of an unrelated peptide, resulting in a chimeric neoantigenic peptide. The high concentrations of certain proteins such as insulin and chromogranin A favors the generation of fusion peptides in β cells while their low expression in thymic APCs prevents clonal deletion of T cells expressing TCRs with specificities to these neoantigens (77). Indeed, the fusion peptides identified to date have largely involved either insulin (Hybrid Insulin Peptides) or chromogranin A. Furthermore, neoantigen-specific T cells can be isolated and characterized from pancreatic islets using neopeptide-loaded MHC tetramers in both mouse and human (67, 78–80). These T cells are expanded and have an activated profile, suggesting that they play a pathogenic role in T1D. How the peptides are transferred from β cells to APCs (or to what extent such peptides can also be generated in APCs themselves) to initially activate the T cells remains an area of active investigation.

Recognition of antigens by TCRs expressed by diabetogenic T cells activates the cells but characterizing the antigen-specific TCR repertoire has been challenging in humans because only the circulating T cells can be assessed for their antigen receptor sequences while the majority of the antigen-specific T cell population is localized in the pancreas. Additionally, although a strong association exists between certain MHC alleles and T1D, the penetrance is not complete. Consequently, many individuals express the risk MHC alleles and possess antigen-specific T cells while remaining disease-free, thereby confounding the link between disease and bearing diabetogenic T cells (81–83). Despite these complications, many studies have identified notable features in the TCR repertoires in T1D human patients as well as in diabetic mouse models. Common TCR features across individuals would indicate that both the autoantigens and autoreactive TCRs are conserved during disease and highlight a focused immune response, which could subsequently shape therapy design.

Early work by several groups in the NOD mouse model identified some V genes (TRBV12 and TRBV13) in the TCRβ locus (TRBV genes) that contributed to disease progression (84, 85). Yet, crossing NOD mice to a strain lacking these genes did not impede T1D development, although insufficient backcrossing could have contributed to this phenotype (86). Indeed, further studies observed an enrichment of T cells bearing TRBV13 rearrangements in the islets, suggesting that these TCRs were clonally expanded in the tissue due to a common antigen (87, 88). But many of these initial studies only examined the TCRβ chains from islet-infiltrating T cells, which paints an incomplete picture regarding the antigen-specific repertoire. This limitation was overcome by the Davis group by implementing single cell PCR to amplify both TCR chain sequences from sorted single T cells (89). This study also confirmed that TRBV13 rearrangements were enriched in the islets of NOD mice. In particular, this study identified that many of the clones possessed CDR3β loops with an acidic residue that was further corroborated in a later study (90). Subsequent work to better understand biases in the TCRα repertoire also highlighted the importance of TRAV5D-4 variable gene usage in diabetogenic TCRs (91). Altogether, these studies provided some preliminary evidence for an immune response in T1D in NOD mice involving a “public” TCR repertoire – a repertoire that is shared across individuals due to common antigens instead of unique to each individual.

Preliminary work in humans pointed to a largely “private” TCR repertoire used by the T cells entering islets in T1D patients (92–94). While clonal expansions were observed within an individual, common motifs were not reported across patients. In a recent comprehensive study, however, many novel findings were reported about the T1D TCR repertoire in humans (95). The authors analyzed over 2×108 total TCRβ sequences from different CD4+ T cell subsets isolated from T1D patients. T cells from T1D patients expressed TCR sequences with shorter CDR3β loops and a reduced contribution from random non-templated nucleotide insertions compared to the CDR3β sequences of healthy individuals. Former work in mice had demonstrated that TCRs with reduced nucleotide insertions tended to be more promiscuous and displayed greater self-reactivities (96). Due to decreased nucleotide additions and a subsequent reduction in TCR diversity, public TCRs were more frequently observed in T1D patients than in healthy individuals. Of note, hydrophobic amino acids were enriched in T1D CDR3β sequences in positions that are associated with enhanced self-reactivity (97).

In one study, a large-scale expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis was performed to determine how MHC haplotypes impact the TCR repertoire (98). Using gene expression data from over 900 human samples, the authors attempted to link MHC allelic differences to TCR variable gene usage. Remarkably, MHC polymorphisms at position 57 in HLA-DQ strongly impacted TRAV gene usage with a high probability. Indeed, individuals with MHC alleles that coded for a non-aspartic acid at this position displayed TRAV gene usage that was often reciprocal to that observed in those individuals with an aspartic acid at position 57. This residue is likely to play a strong role in dictating TRAV gene usage since it is surface exposed and can be directly contacted by the TCR. In particular, since canonical TCR docking onto MHC results in TCRα/MHCβ and TCRβ/MHCα interactions (22), it is not surprising that polymorphisms in the MHCβ chain have a greater influence on TCRα gene usage. Future work can expand upon this study to determine whether certain MHCα polymorphisms affect TCRβ gene usage as well.

2.2. Multiple Sclerosis

MS occurs due to demyelination of neurons in the CNS, which results in progressive loss of neurological function (6). T cells have been shown in both humans and mice to play a central role in exacerbating disease. Genome wide association studies (GWAS) approaches have identified the MHC-II β-chain encoding HLA-DRB1 region as a major risk locus associated with MS (99). Interestingly, unlike most other MHC-II genes where allelic diversity exists for both the α and β chains, HLA-DRα is non-polymorphic (100). Perhaps as a compensatory mechanism, the HLA-DRB1 gene has more polymorphisms than other MHC-II genes, which could provide an underlying rationale for its association with several autoimmune diseases. One of these alleles, HLA-DRB1*15:01, displays a strong association with MS with a reported odds ratio of 3.08 (101, 102) (Figure 1B).

Through the use of fine genetic mapping techniques to explain the effect of this DRB1 allele, DRβ1 position 71 was identified as the most significant residue (103). While most DRB1 alleles code for a charged amino acid at this position (arginine, glutamic acid, or lysine), HLA-DRB1*15:01 instead codes for an alanine at β71. Additionally, β71 helps form the P4 pocket in the peptide binding groove that helps to anchor peptides to the MHC-II molecule. Consequently, larger/hydrophobic peptide anchor residues can be accommodated at this position (104). Unsurprisingly, a recent study in which the HLA-DRB1*15:01 peptidome was investigated using mass spectrometry identified tyrosine and phenylalanine as enriched at the P4 position of bound peptides (105). This corroborates structural work in which the immunodominant peptide from human myelin basic protein (MBP, an antigen targeted by T cells in MS) bound to HLA-DRB1*15:01 also possesses a phenylalanine at P4 (106).

A link with MHC-II has been more indirect in the mouse model for MS called experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Antigen-specific CD4+ T cells are sufficient to induce disease in both transfer and transgenic mouse models, indicating that that a key disease-causing factor is MHC-II-mediated antigen presentation (107–109). Yet, specific risk-associated MHC-II alleles have not been identified. The MHC-II alleles in EAE-susceptible mouse strains do not confer disease susceptibility when introduced into disease-resistant strains (110). This could be partly explained by the fact that the MHC-II locus responsible for disease in susceptible strains maps to the I-A region, instead of the I-E locus, because the I-E heterodimer is not expressed in many strains (111). Additionally, unlike the I-E locus (the HLA-DR ortholog in mice), the I-A locus displays polymorphisms in both MHC chains (112, 113). Thus, increased diversity in both MHC chains complicates pinpointing the disease-associated polymorphisms. Moreover, unlike the NOD mouse which develops spontaneous T1D, a strain of mouse that develops spontaneous MS has not been identified. Instead, EAE can often be effectively induced in several mouse strains by immunizing mice with myelin-derived antigens (114). As such, while MHC-II-dependent antigen presentation plays a critical role in driving EAE progression, no common MHC-II features across different strains can be readily identified as necessary for disease. Rather, each MHC-II allele presents antigens in a unique manner that distinctly activates the autoreactive T cells.

Despite these difficulties, some anomalous antigen binding and recognition features have been identified that have been useful in formulating hypotheses for how T cells break tolerance in EAE/MS. In one mouse model of EAE, mice bearing the I-Au MHC-II allele (such as mice belonging to the PL/J background) are immunized with the MBP peptide (115) (Figure 1B). This results in a relapsing/remitting chronic disease, which is reminiscent of the disease course in humans. Interestingly, the immunodominant epitope in this disease binds poorly to I-Au (116–118). The reason for this weak binding was evident once the trimeric structure involving a cognate TCR/MBP peptide/I-Au was solved (119). The bound MBP peptide has a charged lysine in the p6 position, which is incompatible with the hydrophobic p6 pocket created by the I-Au groove. In addition, the first three positions of the peptide binding groove remain unoccupied by the peptide, further destabilizing the peptide/MHC interactions. Such poor binding likely impacts peptide presentation in the thymus and has been experimentally demonstrated to result in improper negative selection of autoreactive thymocytes (120). Thus, distinct antigen presentation modes between thymic and peripheral APCs could provide an explanation for why central thymic tolerance does not effectively eliminate autoreactive clones (Figure 2). Whether other self-antigens in MS/EAE display similar poor MHC binding remains to be determined (121–126) (Figure 1C).

One further consequence of poor peptide binding is that TCRs also dock onto the peptide/MHC complex in unusual manners. In the MBP/I-Au example described above, as the first three positions of the groove are empty, the cognate TCR focuses on the carboxy-terminal region of the peptide instead of the center (119). This promotes distinct interactions between the TCR and the ligand that are usually not observed with other TCRs. Such unconventional TCR binding was also observed in a structure involving human HLA-DRB1*15:01 presenting MBP peptide and a cognate TCR (127). Unlike the mouse MBP peptide, human MBP peptide binds MHC-II with high affinity and fills the entire groove. Surprisingly, the cognate TCR binds to the complex with a focus on the N-terminal peptide fragment and the MHC α-helices. Uncommon TCR binding modalities have been previously observed to result in poor TCR signal transduction in the responding T cells (128). While it is unclear whether the abnormal docking of the MBP-specific TCRs triggers weak TCR signaling, such a possibility could explain how these T cells escape negative selection in the thymus. In the periphery, weak signaling could be overcome due to the high concentrations of the antigenic peptides that are sufficient to activate the T cells.

Since the aforementioned studies underscore the extent to which improper antigen presentation and recognition impact T cell activation, it is important to have an in-depth understanding of whether all APCs process and present antigens similarly or if instead different APC subsets have distinct capacities in activating T cells. Yet, the precise APC population that primes autoreactive T cells in the lymph nodes has remained elusive. Much attention has been paid to the contribution of DCs in initiating the immune response in EAE due to their superior antigen presentation competency. For instance, when in vitro bone marrow derived DCs were pulsed with MBP peptide and transferred into mice possessing antigen-specific T cells, the recipient mice rapidly developed EAE, suggesting that DCs play an important role in triggering disease (129). Indeed, a previous study by our group also observed that upon activation, DCs could in turn stimulate T cells to break tolerance and cause EAE (130). However, this has also been challenged more recently. Using genetic ablation strategies to deplete DCs, one study observed that mice lacking DCs experienced exacerbated disease, implicating a more protective role for DCs in EAE (131). This was further corroborated in a model of spontaneous EAE in which conditional deletion of DCs resulted in accelerated disease, indicating that other pAPCs are both capable and potent in priming T cells (132).

Several efforts have also been placed to determine which APCs are critical for restimulating the T cells in the CNS to license them to attack the tissue. Antigen presentation has most often been attributed to microglia, which are the CNS-resident leukocyte population (133). Other APC populations such as astrocytes, B cells, macrophages and monocytes have also been linked to restimulating the invading T cells (134–136). Recently, a publication by the Becher group has shed light on the APC population most critical in the CNS (137). Using various genetic targeting techniques to specifically delete MHC-II in different APC populations, the authors identified that a subset of DCs called cDCs are necessary for infiltrating T cells to become locally activated and invade the tissue. Mice in which cDCs lacked high MHC-II expression were protected from severe disease and displayed reduced EAE symptoms. Whether CNS cDCs are as critical in reactivating T cells in humans remains to be investigated.

While antigen presentation is critical for Signal 1, antigen recognition by the cognate TCRs is just as crucial for transducing the signal. Our current understanding of the characteristics of the TCR repertoire of pathogenic CD4+ T cells in MS and EAE has primarily resulted from studies of TRBV gene usage and CDR3β sequences. In human MS patients, much of the work has determined that a shared repertoire does not exist across all individuals. Instead, each individual possesses distinct clonally expanded populations in the CNS that attack tissue and mediate disease (138–141). This is in stark contrast to the repertoire analyses performed using T cells isolated from EAE mice, in which a more public TCR repertoire is observed involving dominant TRBV gene usage (142, 143). Indeed, saturation sequencing of the TCRβ repertoire in myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-peptide immunized mice revealed that public TCRs were preferentially enriched in the CNS (144). Furthermore, when public TCRβ chains were overexpressed in developing thymocytes, the resultant T cells displayed a greater predisposition to becoming autoreactive and causing disease, independent of the TCRα chains with which they were paired (145). These differences between humans and mice could be explained by the fact that disease in mice is often initiated due to autoreactivity to a defined peptide such as MBP or MOG. However, the antigens in humans could be varied even in HLA-matched individuals, which could engender diverse T cell responses. Moreover, epitope spreading is a common characteristic in human MS, in which T cell responses against epitopes distinct from those that initiate disease can arise during chronic inflammation (146, 147). As such, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding shared TCR repertoire features when the TCRs being assessed may have distinct specificities. When this issue was avoided by evaluating the TCR repertoire to a fixed antigen from multiple MS patients, a preferential TRBV gene usage and CDR3β motif was readily identified (148). Thus, by not focusing on the TCR repertoire directed against a specific epitope, the conclusions in human studies are obfuscated and underscore how human TCR repertoire analyses from MS patients need to be revisited with a greater focus on antigen-specificities.

Recent work by our group, though, has argued against the notion of a public TCR repertoire even in EAE (149). In this study, we isolated CD4+ T cells from mice that had been immunized with the MOG peptide to induce EAE. By implementing single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq), we were able to identify both the TCRα and TCRβ chain sequences of each of the isolated cells, which could then be used to assign cells to a clone. Interestingly, although within an individual mouse there was substantial clonal sharing across different tissues, such TCR sharing was absent when TCR sequences were compared across mice. Thus, prior work focusing exclusively on the TCRβ repertoire to define public clones does not take into consideration how TCRα chains also affect antigen recognition. As such, the MS-predisposing polymorphism at position 71 in HLA-DRB1*15:01 has a large impact of TRAV gene usage in humans (98), implying that the TCRα repertoire is not innocuous in disease initiation. These results point to a great need to properly utilize existing techniques to readdress many of the questions regarding the nature of the TCR repertoire in EAE and MS.

2.3. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Disorders characterized by chronic intestinal inflammation are called inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). IBD can be further categorized into two main subgroups – ulcerative colitis (UC), which manifests largely in the colon, and Crohn’s disease (CD), which can impact any region of the small or large intestine (150). Although immunosuppressive therapies have provided relief for many patients suffering from IBD, a large proportion of individuals either do not respond to therapy or become resistant within a year, with others progressing to the point of requiring surgical intervention (151).

Several studies identified a higher concordance rate for IBD among monozygotic twins, suggesting a genetic component to this disease (152). Additionally, familial aggregation of IBD has bolstered the notion that genetic predispositions to disease exist. However, IBD genetic linkage studies have not been able to strongly associate genetic variants with disease susceptibility. As the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is one of the largest tissues exposed to the environment, this weak association likely underscores the importance of environmental factors that affect disease development (153). Consequently, even though immune cells drive the chronic inflammatory state in IBD, the underlying cause of the disease can vary between individuals. For example, microbial composition and variation in the gut due to a variety of factors including age, diet, and geography can dictate the nature of the antigens presented to the immune system and subsequently influence the course of the immune response (154). Overall, the low penetrance of risk variants indicates that IBD likely arises in patients due to genetic susceptibility coupled with environmental factors.

Nevertheless, a few HLA locus polymorphisms have been linked to disease susceptibility. Much as in MS, several HLA-DRB1 alleles are associated with IBD. In particular, HLA-DRB1*07:01 is associated with CD patients often present with ileal inflammation (155, 156) (Figure 1B). Indeed, the odds ratios for ileal disease in CD patients in three independent cohorts were at least 1.5, signifying that there is a 1.5-fold greater risk of ileal inflammation in patients expressing the HLA-DRB1*07:01 allele (155, 157, 158). The HLA-DRB1*01:03 allele, on the other hand, is linked with increased susceptibility to both CD and UC with strong colonic inflammation (159). Multiple HLA haplotypes containing this allele have been observed in IBD patients, further connecting this allele to disease progression. Moreover, the odds ratios for colonic disease in IBD patients were observed to be >5 in multiple studies, indicating a strong association (155, 157, 158). However, why the polymorphisms in these alleles are linked to disease has not been determined. Unlike in T1D and MS where structural and functional studies have provided a greater mechanistic understanding of how HLA risk alleles predispose individuals to disease, similar work to gain insight into the molecular underpinnings of IBD risk variants has been lacking.

MHC-II also appears to play an important role in mouse models of IBD. In one widely used model of colitis, naïve CD4+ T cells (as determined by high expression of CD45RB) transferred into lymphopenic mice (such as Rag1−/−, for example) leads to the recipient mice beginning to lose weight within a few weeks after transfer (160, 161). These mice experience severe colitis mediated by CD4+ T cell infiltration. MHC-II allelic variants do not seem to impact susceptibility in this transfer model as multiple mouse strains with distinct MHC haplotypes have been used to successfully initiate disease (160, 162). Since the recipient mice do not possess any T cells of their own, the disease is a direct consequence of the transferred cells. Indeed, transferring regulatory T cells along with the naïve T cells significantly dampens disease severity (163). The gut microbiota appear to be critical in this transfer model because germ-free mice are resistant to disease (164). Thus, it is likely that certain bacterial peptides presented by MHC-II activate the transferred T cells to initiate colitis.

At steady-state, these microbial antigens function as self-ligands to promote peripheral tolerance in the hosts. Indeed, recent work has highlighted that there exists a cross-talk between the gut and the thymus to ensure that developing T cells bearing TCRs specific for commensal peptides are tolerant to these antigens, blurring the line between what is “self” and “non-self” (165). However, bacterial communities in the GI tract are profoundly sensitive to changes in the host, such as diet and health status (166). Upon perturbation, microbial community shifts have been observed, which could trigger a breakdown in T cell tolerance by presenting antigens to which the host has not been tolerized. Another non-mutually exclusive phenomenon could cause genetically predisposed individuals to gradually develop disease in which antigen-specific T cells that are resistant to peripheral tolerance mechanisms are continually activated. Indeed, this serves as the likely explanation for how disease is initiated in the CD4+ T cell transfer model (160). In the absence of any immunoregulatory influences, the transferred cells are activated by bacterial antigens and proceed to attack the intestine. Conversely, IBD can also manifest when T cells are super-activated, even though regulatory mechanisms are intact. This is most evident as a side-effect of anti-tumor immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy (referred to as immune-related adverse events) in which the “brakes” on T cells are hindered resulting in colitic infiltration and IBD development in many treated patients (167).

Altogether, IBD paints a complicated picture with respect to antigen-driven T cell-mediated autoimmunity, in that the antigenic specificity is by itself insufficient to initiate/exacerbate disease. The context under which the T cells are activated is just as vital in determining their effector potential, which is a concept that could extend to other autoimmune diseases as well. Indeed, TCR transgenic cells with fixed specificities that recognize commensal antigens develop into regulatory T cells at steady-state, but into effector cells (primary Th17 cells) during IBD (168). In a separate study, the authors demonstrated that the same T cells can be polarized into distinct lineages depending on the microbe that expresses its cognate antigen, adding another layer of complexity to T cell activation (169). Confounding matters further, a greater appreciation is being paid to pathobionts – commensal microbes that can cause harm during certain perturbations. One such pathobiont in mice is Helicobacter hepaticus, which does not cause colitis upon colonization unless the mice are deficient in interleukin-10 (IL-10) signaling (170). Helicobacter hepaticus-specific T cells normally adopt a regulatory phenotype in the gut when exposed to H. hepaticus, but become inflammatory in IL-10-deficient hosts (168) (Figure 1C). This inflammatory phenotype is also conferred upon bystander T cells with specificities for other commensals, which then persist as long-lived memory cells in the intestine and could contribute to disease. Simply determining disease-causing antigen specificities and epitopes, thus, is insufficient to deeply understand the causes behind IBD development. Collectively, although IBD shares many features with other autoimmune diseases, it might be better characterized as an inappropriate immune response mounted against bacterial antigens in genetically susceptible individuals (168, 171).

Taking these varied antigens into consideration, it is also difficult to gain insight into any shared TCR features that promote IBD. Because the composition of the gut microbiota is host-dependent, the antigens presented are also frequently private. Consequently, the TCRs that recognize these antigens could be distinct from individual to individual. This is likely true even in the CD4+ T cell transfer model of colitis in mice. Since a polyclonal repertoire is transferred into recipient mice in this model without confirming any antigen-specificity, the targeted antigens are likely to be distinct in each recipient. Indeed, one study reached similar conclusions when comparing the repertoires of the transferred cells across multiple recipients (172). While oligoclonal T cell expansions were observed within an individual mouse, the TCR gene usage varied across mice, indicating that there was little antigenic overlap. Private clonal expansions were observed in individual human IBD patients as well, highlighting that although antigen-driven T cell dysfunction is common in patients, the antigens themselves are not common (173–175).

3. Signal 2 – Costimulatory and Coinhibitory Pathways Activated in T cells

To properly initiate the TCR signaling cascade, T cells need to engage both their cognate antigens and receive an additional signal, which is commonly referred to as ‘Signal 2.’ This second signal serves to amplify (or dampen) the signal stemming from antigen recognition by the TCR (176). Without this second signal, T cells enter a state of anergy, which is characterized by their unresponsiveness (177). This prevents aberrant T cell activation since the costimulatory receptors are not engaged in non-inflammatory settings. To accommodate the various tissues/cell states/inflammatory states that a given T cell may experience, numerous costimulatory and coinhibitory receptors exist on T cells that can skew the T cell fate in myriad directions and provide exquisite control over the extent of the T cell response (176). These receptors engage their ligands on the APCs bearing antigen and colocalize with TCRs within the immunological synapse, where the surfaces of the two cells are juxtaposed and TCR signaling is initiated (178).

Broadly speaking, the costimulatory and coinhibitory receptors belong to two families – the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) and the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) (176). The classic family member belonging to the IgSF is CD28, expressed by T cells, which interacts with CD80 and CD86 on APCs. CD28 is constitutively expressed at high levels by naïve T cells and helps potentiate the production of a key survival cytokine (IL-2) after activation (179). Interestingly, a coinhibitory molecule called cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) competes with CD28 to bind to CD80/CD86 and hinder T cell activation. In fact, CTLA-4 interacts with CD80/CD86 with approximately 10-fold higher affinity than does CD28 but CD28 can still be engaged due to its higher expression levels compared to CTLA-4 (180). CTLA-4 can also act in a cell-extrinsic manner, when, for example, immunosuppressive Tregs (discussed in greater detail below) expressing high levels of CTLA-4 outcompete CD80/CD86 binding on APCs by CD28 expressed by the T cell being primed/activated (181). Thus, whether a T cell is activated and the degree of its activation are often dictated by which of these two proteins can more potently mediate its actions.

Notably, CD28 serves as more of an exception with respect to its expression on naïve CD4+ T cells. Expression of many costimulatory molecules is instead often induced de novo or upregulated upon T cell activation (182). In addition, many coinhibitory molecules are also expressed after activation, which help to maintain tolerance and prevent unchecked CD4+ T cell activation. Indeed, high expression of coinhibitory molecules is frequently a feature of activated cells, with the expression levels directly correlating with the extent of activation (183). The kinetics of costimulatory/coinhibitory molecule expression on T cells has been dubbed the tidal model of co-signaling (176, 182). Initially, T cell activation through the TCR results in increased expression of costimulatory receptors, which continue to favor and promote T cell activation. However, at the peak of the T cell response, coinhibitory receptors are also expressed at high levels, which then function to resolve the immune response by suppressing T cell activation and function. Therefore, T cell costimulation is not merely an on/off switch to amplify/dampen TCR signals but instead is a dynamic process that provides cues to CD4+ T cells in spatiotemporally regulated manners.

Stimulatory signals from receptors belonging to either superfamily promote cell survival, cell growth and activation of effector function. Signaling through these receptors primarily converge on the activation of canonical immune transcription factors such as NF-kB, NFAT and AP-1 (184, 185). Since these factors are also downstream of TCR signaling, pathways activated by costimulatory receptor engagement integrate and synergize with those of the TCR to enhance cell activation. Coinhibitory receptors act at various nodes along the pathways to inactivate or dampen the signals to serve as ‘brakes’ on the system. Importantly, though, each surface molecule can also activate independent pathways that together contribute to eventual CD4+ T cell fate (176). This is best evident when coinhibitory receptor blockade is employed in anti-tumor and chronic viral infection therapies to activate T cells (186). Merely blocking one receptor is often not as effective as blocking multiple receptors. Furthermore, blocking distinct coinhibitory receptors can differentially rescue specific functionality such as proliferation, cytotoxicity or cytokine secretion, indicating that each coinhibitory receptor plays a non-redundant role in dampening T cell activation and response. Similarly, while CD28 signaling results in high IL-2 production, signaling through inducible T cell costimulatory (ICOS), another IgSF member, instead results in high IL-4 and IL-21 production (187). Altogether, Signal 2 pathways both overlap with those of Signal 1 and can also provide unique signals depending on the molecule(s) engaged. Such molecular checks and balances are necessary to guide the T cells to mount appropriate immune responses when faced with dynamic immunogenic conditions and are often impacted in various autoimmune diseases, thereby contributing to improper T cell activation (Figure 3).

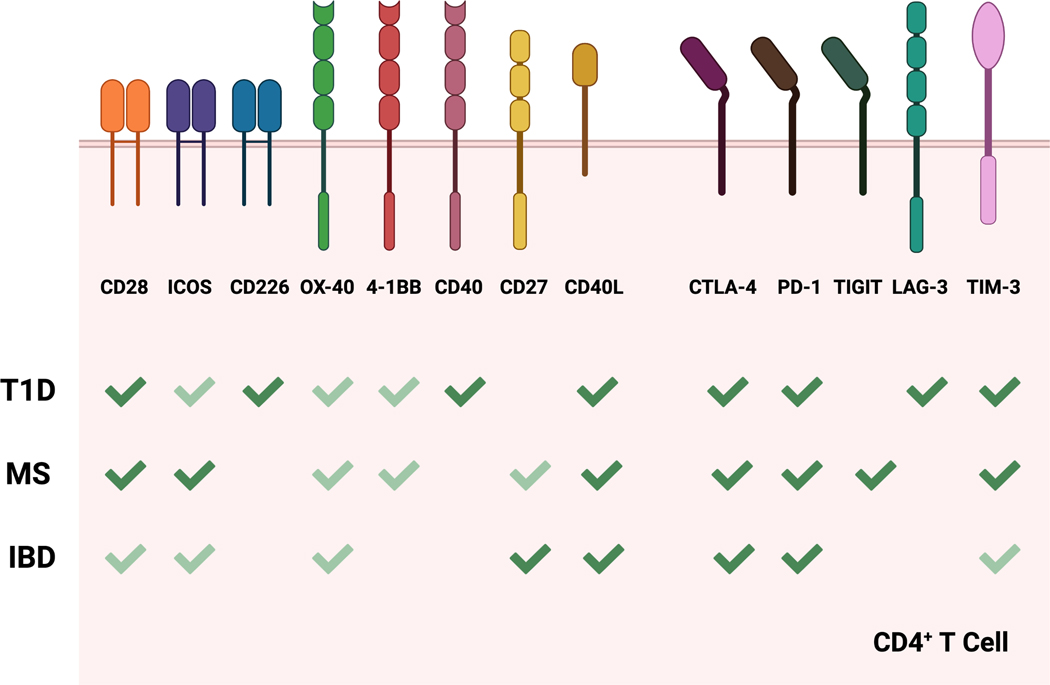

Figure 3.

Costimulatory and coinhibitory receptors involved in autoimmune diseases. The different costimulatory and coinhibitory receptors expressed by CD4+ T cells known to play a role in T1D, MS and IBD are depicted. The significance of any given receptor in contributing to disease progression is highlighted using dark green check marks (strong reported contribution) vs light green check marks (weak reported contribution). This image was created with BioRender.com.

3.1. Type I Diabetes

Due to its important role in T cell priming, it would be expected that CD28 plays an important role in activating diabetogenic T cell clones. In the absence of proper CD28 signaling, T cells were thought to become anergic and individuals would be protected from T1D. Instead, CD80/CD86 double-deficiency in NOD mice exacerbated T1D incidence (188). This finding was further corroborated in CD28-deficient NOD mice and was attributed to the paucity of CD25+ CD4+ Tregs that require CD28 signaling to properly develop. Indeed, absence of Tregs has long been known to increase incidence of multiple autoimmune disorders (189). Consistent with these results, treatment of NOD mice with antibodies that block CD28 interactions with CD80/CD86 also resulted in increased disease due to a reduction in Treg numbers (190). Interestingly, humans expressing the T1D-associated SNP (CT60G) in the CTLA4 locus expressed lower levels of the CTLA4 isoform lacking the transmembrane domain, referred to as soluble CTLA-4 (sCTLA-4) (191). Reduced expression of this sCTLA-4 was thought to allow for increased CD28-mediated activation and subsequent autoimmunity. NOD mice in which sCTLA-4 expression is reduced by RNA interference displayed accelerated T1D, further corroborating the human data (192). Our lab has previously reported that NOD mice also express an alternatively spliced CTLA-4 variant called ligand independent CTLA-4 (liCTLA-4) that lacks the extracellular domain required for CD80/CD86 binding (193). This isoform is expressed constitutively in primary CD4+ T cells and functions by binding to and dephosphorylating the TCR signaling proteins to inhibit signal cascade. Notably, disease-resistant mice possessed CD4+ T cells with higher expression of liCTLA-4 compared to those in disease-susceptible mice. Thus, various isoforms derived from the same genes can all impact autoimmunity but via distinct mechanisms.

One recent study measured the role of CD226 in impacting T1D incidence (194). CD226 is another costimulatory molecule expressed by T cells that interacts with CD155 (and also CD112) expressed by APCs and has been shown to promote differentiation of CD4+ T cells into the inflammatory Th1 subset (195). Of note, a SNP in CD226 in humans is associated with T1D and has been shown to enhance T cell activation (196, 197). Additionally, a risk locus in NOD mice also contains the Cd226 gene, indicating that this gene might be important even in the disease observed in mice (198). Indeed, NOD mice lacking expression of Cd226 displayed decreased T1D incidence and islet infiltration (194). Intriguingly, the T cells in this mouse also displayed reduced affinities for an immunodominant antigen, suggesting that CD226 signaling impacts T cell development in the thymus and in its absence, strongly self-reactive cells are not matured.

Unlike IgSF receptors such as CD28 and ICOS, TNFRSF members such as CD40-ligand (CD40L), OX-40 and 4–1BB appear to contribute more to effector T cell generation in T1D without impacting Treg function. This is rather surprising given the fact that TNFRSF members are vital for thymic Treg development (199). Since the importance of TNFRSF members in Treg development was assessed in C57BL/6 mice, while their absence in influencing disease was addressed in NOD mice, strain-dependent features could explain these differences. Nevertheless, germline deficiency of CD40L was sufficient to inhibit T1D in NOD mice, suggesting that CD40/CD40L signaling was required to initiate disease (200–202). CD40-expressing DCs promote Th1 differentiation and induce production of potent pro-inflammatory cytokines by the activated T cells (203). Interestingly, while CD40 is more often associated with expression in APCs, an aggressive autoreactive CD4+ T cell population was observed to express CD40 in T1D. Transferring these CD40+ T cells into non-diabetic mice was sufficient to induce progressive disease while transferring CD40− T cells could not transfer disease, highlighting the importance of CD40-expressing T cells in disease initiation (204, 205). In total, many costimulatory receptors cooperate with one another to maintain a delicate balance between Treg function and effector T cell activation that progressively disrupts homeostasis as T1D develops.

Prominent coinhibitory receptors such as PD-1 and LAG-3 also dramatically impact T1D progression, with SNPs in the human PDCD1 locus (the gene coding for PD-1) associated with disease susceptibility (206). This finding is recapitulated in mice as Pdcd1−/− mice develop aggressive T1D with complete penetrance (207). Similarly, Lag3 deficient NOD mice displayed highly aggressive disease progression (208). Extracellularly, LAG-3 competes with CD4 to bind to MHC-II while intracellularly, it inhibits TCR signal transduction (209). Due to its dual role, it is possible that LAG-3 can also function in a cell-extrinsic manner since Tregs express high levels of this protein and their function could be impacted in its absence. Lastly, T cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM-3) is another coinhibitory receptor that could play a role in exacerbating T1D. TIM-3 blockade in NOD mice accelerated T1D progression compared to that in control mice (210). Curiously, though, SNP analysis within the TIM-3 gene revealed no positive correlation with T1D, suggesting that there could be functional redundancy with other proteins in humans (211).

3.2. Multiple Sclerosis

Remarkably, unlike what is observed for T1D, CD28 signaling is necessary for induction of EAE (212). This is further corroborated by the fact that CD80/CD86 deficient mice are also protected from MOG peptide induced EAE (213). These puzzling discrepancies between disease models could be explained by the fact that the experiments were performed on mice from distinct genetic backgrounds (NOD vs C57BL/6). Indeed, even in EAE experiments, CD80/CD86 blockade accelerated EAE in mice from the SJL/J background, suggesting that other CD28 signaling deficiencies do not manifest themselves in the same manners in different strains (214, 215). Of note, while CD80 and CD86 are often considered to be interchangeable, their expression profiles are not always similar in different APC populations during EAE, with CD80 contributing more in the presentation of myelin-derived antigens (216–218). The tissue and cell type-dependent expression of CD80 and CD86 during EAE remain poorly understood and should be a future area of investigation.

ICOS deficiency surprisingly results in enhanced EAE induction with severe CNS infiltration by lymphocytes (219, 220). This has been attributed to reduced immunoregulatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10, produced by Th2 and Tr1 cells, respectively, that require ICOS signaling for their proper differentiation. These results are also in line with an independent study in which ICOS engagement with its ligand was blocked via treatment with a monoclonal antibody (221). Such blockade was discovered to have dynamic consequences depending on when the antibody was administered. When administered during the T cell priming phase, antibody blockade augmented disease induction in mice, which appears to phenocopy what is observed in ICOS germline deficiency. Conversely, when administered at later time points during the efferent phase, antibody blockade largely abrogated disease. Thus, the temporal context under which ICOS signaling is impacted can dramatically influence disease course.

For some of the TNFRSF members whose roles have been investigated in MS/EAE, a recurring theme is that while their absence does impact disease, they mostly appear to function in conjunction with the CD28/CD80/CD86 axis. For example, genetic deletion of either OX40 or OX40L reduces disease severity but does not intrinsically protect against EAE (222–224). Overexpression of OX40L, on the other hand, exacerbated disease but only when the CD28 signaling axis was intact (225). Interestingly, CD27 deficient mice experience worse disease while CD70 (the ligand for CD27) overexpressing mice experience ameliorated disease (226). This observation could be due to the fact that intact CD27 signaling is critical for proper thymic Treg development, as mentioned previously (199). Without proper CD27 signaling, dysfunctional Tregs might not be able to successfully impede effector T cell activity.

In addition to costimulatory molecules, several coinhibitory molecules have also been implicated in regulating disease induction. The previously described CTLA4 SNP associated with T1D (CT60G) is also a risk variant associated with MS (191, 227). Additionally, CTLA-4 has been shown to affect MBP-specific T cell function in MS patients (228). This extends to mice because blocking CTLA-4 results in more severe EAE (229–231). PD-1 signaling can also affect disease progression in both mice and humans (206, 232). Former work by our group identified the T cell Ig and ITIM domain (TIGIT) protein as regulatory during EAE (233). The CD226/TIGIT axis is analogous to the CD28/CTLA-4 pathway in which both CD226 and TIGIT bind to the same ligands but TIGIT provides an inhibitory signal to T cells. Mice lacking TIGIT developed more severe EAE upon immunization with MOG peptide, supporting its role as a strong coinhibitory receptor. In an independent study also by our group, we identified that TIM-3 also serves to inhibit T cell responses during EAE (234). Tolerance induction was inhibited when TIM-3-mediated signaling was abrogated and T cells became polarized into inflammatory effectors. Moreover, TIM-3 has also been linked to MS in humans where TIM-3 expression was observed to be reduced in T cells from MS patients (235, 236). Altogether, different coinhibitory pathways coordinate to prevent autoreactive T cells from causing CNS tissue damage in MS.

3.3. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

How the CD28 pathway influences IBD initiation is not entirely straightforward. In one initial study, when T cells were transferred into CD80 or CD86 single deficient mice to induce colitis, mice developed accelerated disease in either of the two single deficient recipient mice compared to WT recipient mice (237). However, CD80−/− CD86−/− recipient mice did not exhibit colitis-like symptoms, suggesting that single deficiency of either of the two CD28 ligands impacts T cell activation differently than absence of both. This observation was attributed to the fact that CTLA-4 expression on the transferred T cells was reduced in single deficient recipient mice compared to CD80/CD86-sufficient mice, suggesting that high cell-intrinsic CTLA-4 expression is necessary to inhibit rampant T cell activation (237). These results were revisited in a separate study by the same group in which colitis was induced spontaneously in a transgenic mouse that constitutively secreted soluble CD86-Ig fusion protein (238). In this system, the authors argued that increased disease in the presence of the fusion protein was due to its binding to CTLA-4 on T cells (because of its higher affinity for CTLA-4 over CD28) that inhibited the cell-intrinsic role CTLA-4 plays to curb immune activation.

Interestingly, CD28/CD80/CD86 may not even be entirely required during intestinal inflammation. One study identified that when T cells are deprived of CD80/CD86 signaling, they rely instead on ICOS and OX40 signaling to break tolerance. An earlier study had also demonstrated that ICOS blockade is effective in ameliorating colitis only in the absence of CD28 (239). Furthermore, OX40L expressing activated DCs were enriched in the draining lymph nodes during intestinal inflammation (240). Blocking OX40L-mediated signals was sufficient to abrogate colitis development in the treated mice. A later study determined that part of the effects of OX40 signaling also involve Tregs because Treg numbers were depleted due to increased apoptosis in the absence of OX40 (241). Blocking other costimulatory molecules such as CD27 and CD40L have also proven to be effective therapies in mouse models of colitis (242, 243). Mice overexpressing CD40L acquired a lethal inflammatory bowel disease marked by infiltration of CD40L+ T cells (244). This is particularly noteworthy since CD40L expression has been observed to be elevated in human IBD patients, especially within the inflamed mucosa (245, 246). Altogether, several costimulatory molecules can each initiate IBD.

Coinhibitory receptors in IBD have received renewed interest of late due to the increased use of ICB therapies in patients with tumors, which have now been successfully implemented in the clinic to treat patients suffering from various cancers such as melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and renal cell carcinoma, to name a few (247). In these therapies, antibodies targeting CTLA-4, PD-1 or PD-L1 (the ligand for PD-1) are used to reinvigorate dysfunctional T cells that express high levels of CTLA-4 or PD-1 due to chronic antigenic stimulation within the tumors (248). In doing so, the antigen-specific T cells are now poised to attack and kill the malignant cells. Unfortunately, because of the broad nature of these therapies, T cells are indiscriminately activated, even those that bear specificities for non-tumor self-antigens in other tissues. Consequently, many autoimmune diseases have been reported in patients receiving αCTLA-4 or αPD-1 treatments (167). One major site in which autoimmunity is initiated is the GI tract resulting in IBD. Severe T cell infiltration and substantial morbidity often results in patients choosing to discontinue therapy. αCTLA-4 therapy induces more frequent and severe inflammatory events, which is congruent with the role of CTLA-4 in maintaining mucosal tolerance in mice during colitis (249). More recently, antibodies targeting TIM-3 have also been demonstrated to reduce tumor burden when combined with αPD-1 therapy (250, 251). Intriguingly, patients with UC had reduced expression of TIM-3 on the surfaces of T cells, indicating that decreased TIM-3 levels could contribute to enhanced T cell responses and exacerbated disease (252). Thus, it remains to be seen whether treatment with αTIM-3 antibodies also results in IBD in some patients.

4. Signal 3 – Cytokine Signaling and T Helper Cell Subset Differentiation

Cognate antigen recognition coupled with costimulation is sufficient to activate T cells. However, this activated cell-state does not intrinsically predispose T cells to be functionally more (or less) adept at combating intracellular pathogens such as viruses or extracellular pathogens such as parasites. Clearing the host of these pathogens requires further specialization on the part of the T cells to ensure that the downstream responses are ideally suited to target the pathogen. The specialized activated T cells can then mediate their effector functions by recruiting specific immune cell populations to tissues and promoting inflammatory/regulatory environments by secreting distinct soluble molecules (253). This specialization is often established during the initial T cell priming stage through cytokines secreted by APCs, which act on the responding T cells (Signal 3) and differentiate them into functionally distinct subsets (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Therapies targeting different Th subsets implemented in humans. Top, In addition to Signal 1 and Signal 2, different cytokine cocktails are required to effectively differentiate naïve CD4+ T cells into the Th1, npTh17, pTh17, Tfh, pTreg and Tr1 subsets. Subsequently, these functional subsets display distinct cytokine secretion profiles that can differentially impact autoimmune disease progression. Bottom, The current therapies employed to inhibit effector T cell differentiation and/or function as well as expand regulatory T cell differentiation and/or function are listed for each subset. This image was created with BioRender.com.

Some initial work has indicated that strength of TCR signaling can affect effector T cell polarization into functional subsets, suggesting that distinct antigen specificities can instruct T cell fate (254–257). However, in most cases, the strength of TCR/costimulatory signaling does not fundamentally dictate T cell fate. Instead, the cytokines present during activation play critical roles in shaping the functionality of the T cells (253). Due to this, a substantial body of reductionist in vitro work exists in which naïve CD4+ T cells are polarized using non-specific TCR stimulation in the presence or absence of various other cytokines. These studies have imparted tremendous knowledge to the community and identified both the core cytokines required to polarize T cells and the cytokines secreted by the polarized cells.

The canonical T helper subsets are the type 1 (Th1) and type 2 (Th2) cells (258). Th1 cells are important for host defense against intracellular pathogens such as viruses and secrete large amounts of the antiviral cytokine interferon gamma (IFNγ), which promotes enhanced antigen presentation on APCs and activates many innate (NK cells) and adaptive (CD8+ T cells) lymphocyte populations (259). Th2 cells play an important role in clearing extracellular pathogens such as parasites and helminths by producing the prototypical Th2 cytokine interleukin 4 (IL-4) that helps to recruit innate immune cells such as eosinophils and mast cells to the site of infection (259). Initial activation sensitizes T cells to IL-12 and IL-4 produced by APCs to differentiate cells into the Th1 and Th2 subsets, respectively (260–262). Importantly, these signals elicit expression of the master transcription factors associated with these subsets – T-bet and GATA-3, respectively – that promote transcriptional and chromatin remodeling to establish stable fates upon differentiation (263, 264).

Three other Th subsets were more recently identified. Th17 cells, named because of their ability to secrete large amounts of the potent cytokine IL-17A, were identified for their role in autoimmunity (265–267). Different cytokine cocktails have been identified to promote Th17 differentiation both in vitro and in vivo. While combined exposure to TGFβ1 and IL-6 was shown to effectively polarize Th17 cells initially, it was later discovered that these Th17 cells possessed a regulatory profile imparted by signals received from the immunosuppressive cytokine TGFβ1 (268–270). Concurrently, a more inflammatory Th17 subset was discovered to be polarized by IL-23 (271). Importantly, both the regulatory and inflammatory Th17 subsets express high levels of the master transcription factor RORγt, which enhances and stabilizes their phenotype (272). A second T cell subset was identified due to its importance in curtailing autoimmunity in both humans and mice. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) suppress effector immune responses through myriad mechanisms and express the transcription factor FoxP3 (273). Interestingly, Tregs can also develop in multiple ways in vivo. In a process termed agonist selection, some strongly self-reactive T cells are diverted into the Treg lineage in the thymus instead of undergoing negative selection (274). Thus, unlike the overwhelming majority of T cells that exit the thymus in a naïve unpolarized state, thymic-derived natural Tregs (nTregs) commit to their lineage as a consequence of their thymic development. Tregs can also arise in the periphery (pTregs) from naïve CD4+ T cells that are activated in the presence of TGFβ (275). Lastly, type 1 regulatory (Tr1) cells are another CD4+ T cell subset characterized by strong production of the immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGFβ1 (276). Strikingly, although they share functional features with Tregs with respect to their ability to suppress effector T cell responses, these cells do not express the Treg transcription factor FoxP3. Tr1 cells can be differentiated in the presence of IL-10, IL-27 and/or TGFβ1 (277–279). Overall, the proportion and composition of the various Th subsets can drastically impact how tissues are surveyed by T cells and whether they break tolerance.

4.1. Type I Diabetes

Historically, the major T cell subset thought to be driving T1D was the Th1 population. An initial study explored the roles of differentiated T cell subsets in initiating disease course in NOD mice (280). The investigators polarized naïve CD4+ T cells into either Th1 or Th2 subsets in vitro by exposing the cells to different cytokine environments. Subsequently, these polarized cells were independently transferred into neonatal NOD mice to determine whether polarized cells of a given lineage were sufficient to cause disease. The in vitro-derived Th1 cells caused hyperglycemia in 50% of the recipient mice within 2 weeks after transfer and caused diabetes in 90% of the mice by 5 weeks (280). By contrast, the mice receiving Th2 cells largely were resistant to developing disease, with only 1 out 21 mice becoming hyperglycemic. This dramatic difference in ability to cause disease could not be attributed to differential tissue-trafficking abilities between the two Th subsets but rather a differential ability to create a pro-inflammatory environment upon arriving at the islets in the pancreas.

Further supporting a key role of Th1 cells in disease progression are the studies that have identified IFNγ, the signature Th1-produced cytokine, as a major contributing factor in T1D. Blocking IFNγ was sufficient to prevent T1D in NOD mice (281, 282) and overexpression of the gene suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1), which negatively regulates IFNγ signaling, resulted in protection from disease (283). T1D patients also possessed autoantigen-specific IFNγ-producing cells, highlighting the importance of Th1 cells in humans (284). Patients with gain of function mutations in STAT1, the transcription factor downstream of IFNγ receptor, also presented with concomitant T1D (285). Unsurprisingly, NOD mice lacking STAT1 were resistant to T1D (286). The same study also confirmed these results using an inhibitor for Jak2, the kinase upstream of STAT1, which delayed T1D progression in mice.

More recently, Th17 cells have also been proposed as a possible disease-causing T cell subset in T1D but conflicting results have made a definitive verdict about the role of this population challenging. NOD mice colonized with the Th17-inducing segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) displayed delayed diabetes kinetics (287). However, the Th17 cells induced by SFB are known to possess a more regulatory phenotype and serve to play a protective role in mucosal tissues (288, 289). Instead, when antigen-specific Th17 cells were polarized in the presence of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-23, the mice developed rapid insulitis and subsequent diabetes (290, 291). Interestingly, disease progression was dependent on the transferred Th17 cells converting to Th1 cells and producing IFNγ. This observation is consistent with work indicating that Th17 cells exposed to IL-23 are a potent inflammatory population that adopts a pathogenic phenotype characterized by coinciding Th1 and Th17 functionalities (292–294).

APCs isolated from humans with T1D expressed elevated levels of IL-1β and IL-6, two cytokines that are important in Th17 differentiation, suggesting that Th17 cells could participate in human disease (295). Furthermore, gain of function mutations in STAT3, which is downstream of IL-6, have also been linked to early-onset T1D in humans (296–298). These patients present with higher numbers of Th17 cells, likely due to the hyperactive STAT3. Mapping some STAT3 missense mutations to functions has helped determine that one possible mechanism by which STAT3 is hyperactive is through enhanced DNA binding affinity, which would result in increased chromatin accessibility in STAT3-dependent gene expression and a more stable Th17 phenotype (299). In a separate study, STAT3 gain of function was observed to result in increased expression of SOCS3, which negatively regulates IL-2 signaling and Treg numbers and stability (297).

Another cytokine with a curious role in T1D is IL-21, which belongs to the common γ-chain receptor family of cytokines that includes IL-2, IL-4, and IL-7. It is one of the candidate genes located in a disease-susceptibility locus and is elevated during disease in mice (300–304). The importance of IL-21 signaling was highlighted in two studies in which mice lacking the IL-21 receptor (IL-21R) failed to develop T1D (304, 305). While IL-21 can stabilize and enhance Th17 differentiation (306, 307), IL-21 signaling deficient mice did not exhibit any differences in Th17 numbers or functions (304). Yet, a separate study identified that IL-21 signaling in CD4+ T cells was necessary in T1D progression, suggesting that a different IL-21-sensitive Th subset is likely responsible for causing disease (308).

Indeed, one distinct T cell population that appears to be critical in T1D is the T follicular helper (Tfh) subset. These T cells are important in germinal center formation and function, where they provide crucial cues for proper B cell maturation during an immune response (309). They express high levels of the transcription factor Bcl6 and secrete IL-21, which also signals through STAT3. Remarkably, IL-21 itself can lead to increased expression of Bcl6 (310). In germinal centers, antigen-specific B cells mutate their antigen receptors and undergo a selection process, which relies on Tfh cells, to retain only those B cells with high affinities for the target antigens. Thus, the observation that Tfh cells are enriched in pancreatic lymph nodes in mice implicates their role in the generation of islet-specific autoantibodies, which are a hallmark of T1D (311). Mice in which Tfh generation is augmented exhibit accelerated T1D progression, further linking this T helper subset to disease (312).

Dysfunctional Tregs are another feature in individuals with T1D (313). As previously described, Tregs can arise during thymic selection (nTregs) or be generated in peripheral tissues when exposed to TGFβ1 during antigenic stimulation (pTregs) (274, 275). Thymic Tregs are reliant on IL-2 stimulation, which serves as a surrogate signal 3 even in sterile conditions, for their complete maturation. Strong TCR signaling in the thymus generates CD25hi FoxP3− Treg progenitors that require IL-2 signaling to mature into nTregs (314). Importantly, several studies have been able to link SNPs in humans impacting IL-2 signaling with Treg dysfunction (301, 315, 316). These results were also corroborated in NOD mice, which display a defect in IL-2 signaling in Tregs (317). Current therapies in T1D involve delivering IL-2 specifically to Tregs to ensure Treg activation without activating effector T cell populations and may serve as effective therapies in the future (318).