Abstract

Background

It is well established that transgender people experience considerable health inequities, which are sustained in part by limited teaching about transgender healthcare for trainee health professionals.

Aims

The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of both teaching staff from health professional education programmes and transgender community members on the best ways to teach about transgender healthcare, with a focus on ways of: 1) overcoming barriers to this teaching; and 2) involving community members in this teaching.

Methods

A research advisory committee was convened to guide the project and included transgender community members, teaching staff from health professional programmes, and trainee health professionals in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Three preliminary focus groups were held with 10 transgender community members. These community members were then invited to act as transgender community ‘ambassadors’ in focus groups with teaching staff based on suggestions from the advisory committee. Six focus groups were conducted with 22 teaching staff from a range of health professional education programmes along with at least two transgender community ambassadors.

Results

Teaching staff positioned themselves as lacking the expertise to teach about transgender healthcare but also as expert teachers when applying methods such as small group teaching. Transgender participants also positioned themselves as having expertise arising primarily from their own experiences and acknowledged that effective teaching about transgender healthcare would need to cover a diversity of transgender identities and healthcare outside their own experiences. Teaching staff and transgender community members were keen to pool expertise and thus overcome the shared sense of lacking the expertise to teach about transgender healthcare.

Discussion

These findings provide insights into the current barriers to teaching about transgender healthcare and provide future directions for staff development on teaching about transgender healthcare and ways of safely involving transgender community members in teaching.

Keywords: Curriculum planning, focus groups, patient educators, qualitative research, stakeholder consultation, transgender

Introduction

The existence of transgender people has a long and varied history in different cultures around the world (Byne et al., 2018; Oliphant et al., 2018; Winter et al., 2016). In this article we use the term transgender as an umbrella for teaching about the provision of both specialist and general healthcare for people whose sex assigned at birth does not align with their gender identity, including people with non-binary gender identities whose gender is neither exclusively female nor male and people with culturally specific indigenous genders such as two-spirit people in North America, māhu in Hawai’i, and whakawāhine, tangata ira tāne, and tāhine in Aotearoa/New Zealand (Oliphant et al., 2018; Winter et al., 2016).

Recent decades have seen progressive increases in the social conditions that allow transgender people to live as their gender in many locations (Byne et al., 2018; Oliphant et al., 2018; Pearce, 2018; Winter et al., 2016). However, this social progress has not yet been matched by improvements in healthcare service delivery for transgender people nor in extensive education for trainee healthcare professionals about providing healthcare for transgender people (Byne et al., 2018; de Vries et al., 2020; Ellis et al., 2015; Obedin-Maliver et al., 2011; Pearce, 2018; Taylor et al., 2018; Veale et al., 2019; Winter et al., 2016; Wylie et al., 2016). In this article we take a broad approach to transgender healthcare by considering the need to provide education about the wide range of aspects of healthcare for transgender people that addresses both the general provision of healthcare that is inclusive of transgender people as well as foundational provision of education about specialist healthcare for transgender people within gender identity service or mental health services, reflecting existing research and models of transgender healthcare (Byne et al., 2018; Delahunt et al., 2016; Ellis et al., 2015; Pearce, 2018; Riggs et al., 2015; Turban et al., 2018; Winter et al., 2016; Wylie et al., 2016).

Research into discourses evident across a wide array of online narrative material relating to different aspects of transgender healthcare in the UK by Pearce (2018) has demonstrated how transgender people and health professionals position themselves in relation to dominant discourses of ‘trans as condition’ (e.g., in relation to depathologisation of transgender people’s lives) and ‘trans as movement’ (e.g., in relation to activism around access to healthcare) and how these discourses relate to barriers to care across the healthcare system. A review of the factors that impact on the mental health of transgender people in Australia by Riggs et al. (2015) identified the negative impact of not being able to access desired gender affirming care, cisgenderist discrimination in society, and levels of stress exceeding the protective effects of community resources and ability to cope. A recent nationwide survey of over 1,100 transgender people in Aotearoa/New Zealand by Veale et al. (2019) has revealed extensive gaps in provision of healthcare for transgender people. The main health professional most respondents were seeing for gender affirming care was a general practitioner (55%) and only 24% of respondents felt that this health professional knew almost everything about providing healthcare for transgender people, and 42% knowing some things or very little or nothing. Respondents also raised barriers to both general healthcare and gender affirming care such as fear of mistreatment and direct costs. These findings indicate the kinds of gaps in healthcare that can exist for transgender people globally and an associated need for foundational education of health professionals across the disciplines that provide routine healthcare. Veale et al.’s findings also give local context to the present study on teaching about transgender healthcare within health professional programmes in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

There already exists guidance on delivering healthcare for transgender people in specific healthcare disciplines including dentistry (Russell & More, 2016), medicine (Chipkin & Kim, 2017; Winter et al., 2016; Wylie et al., 2016), psychiatry (Byne et al., 2018), and clinical psychology (Singh & dickey, 2016). However, existing clinical guidance typically summarizes approaches to apply in practice for one specific healthcare discipline without detailed pedagogical insights to support focused learning and without input from a range of transgender people. Exploratory consultative processes provide an effective way to understand barriers that will need to be addressed in order to inform enhancements to the limited current teaching about transgender healthcare across different health professional education programmes. In order to be able to effectively provide education about transgender healthcare to the range of health professionals who routinely provide forms of healthcare for transgender people there is a pressing need to determine the perspectives of those involved in teaching of all health professionals. It is therefore pertinent to take an interprofessional approach to seeking the perspectives of staff who teach into the range of health professional programmes along with input from transgender community members. Research on health professional education has established the value of interprofessional education approaches as a productive way for health professionals to learn with, from, and about different healthcare disciplines about a host of topics (Coleman, 2018; Kaste & Halpern, 2016; Pratt-Chapman & Phillips, 2020). There is some preliminary evidence of the value of interprofessional approaches to education about transgender healthcare specifically (Braun et al., 2017; Russell & More, 2016), and there is a need for further research exploring the provision of education about transgender healthcare across professions.

Education for trainee health professionals about healthcare for people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer (LGBTQ) has begun to become more established in healthcare curricula around the world, but issues concerning transgender people and the healthcare needs of different groups of transgender people (e.g., based on gender and age) are frequently absent or outside core priorities in time-limited curricula (de Vries et al., 2020; Desrosiers et al., 2016; Dubin et al., 2018; Obedin-Maliver et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2018). Pathways to gender affirming treatments remain either absent or in development in many healthcare systems (Byne et al., 2018; Delahunt et al., 2016; Pearce, 2018; Riggs et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2016; Wylie et al., 2016). Transgender people seeking healthcare still commonly encounter health professionals with insufficient knowledge about transgender identities and associated social and medical processes of gender transition (Liszewski et al., 2018; Pearce, 2018; Winter et al., 2016). As such, it has been found that transgender people are often asked or required to educate staff during consultations (Chipkin & Kim, 2017; Jaffee et al., 2016; Riggs et al., 2014; Schimanski & Treharne, 2019). It is crucial to understand how teaching staff can contribute to systemic changes by educating trainee health professionals about transgender healthcare but there is a gap in knowledge about how teaching staff feel about educating trainee health professionals about transgender healthcare. This gap in knowledge on the perspectives of teaching staff is pervasive across the range of healthcare disciplines that provide important aspects of routine and specialized healthcare for transgender people, including dentistry, pharmacy, physiotherapy, and psychology (de Vries et al., 2020; Desrosiers et al., 2016; Dubin et al., 2018; Morris et al., 2019), although the number of publications describing pedagogical innovations in teaching specifically about transgender healthcare have increased in the past decade (e.g., Braun et al., 2017; Ostroff et al., 2018; Parkhill et al., 2014; Park & Safer, 2018).

Recent moves to actively incorporate transgender healthcare in health professional curricula include the detailed pedagogical resources developed by the Association of American Medical Colleges (Hollenbach et al., 2014) as well as development of specific pedagogical innovations in some locations across many individual health professional education programmes, including dentistry, medicine, pharmacy, and psychology. For example, Brondani and Paterson’s (2011) research at a Canadian university explored the outcomes of a year-long paper on LGBTQ health in dentistry education involving panel discussions including some transgender community members. The reflections of their students revealed they had developed insights into diversity and professionalism. Similarly, Parkhill et al. (2014) conducted a panel discussion but specifically with transgender community members within a required course for first year pharmacy students in the US. Over 90% of students found the session useful and felt it aided in learning about transgender identities and gender transition as well as ways to communicate respectfully within a pharmacy setting. In addition, a single lecture on transgender healthcare within a required course for third year US pharmacy students increased knowledge and confidence in that knowledge (Ostroff et al., 2018).

Pedagogical innovations to teach medical students about transgender healthcare have tended to be combined with LGB health but a small and growing number of innovations have focused on transgender healthcare specifically (see Desrosiers et al., 2016; Dubin et al., 2018). In a prime example, Park and Safer (2018) tested the outcomes of an elective clinical rotation in collaboration with transgender healthcare service providers for 20 senior medical students at one US university following foundational teaching in earlier years. The clinical rotation resulted in increases in perceived knowledge and comfort to provide transgender healthcare. In research with Australian mental health professionals, Riggs and Bartholomaeus (2016) found that psychiatrists, psychologists and other mental health professionals were more knowledgeable and confident about providing care for transgender people if they had clinical experience with transgender people or had attended specific education sessions that covered transgender healthcare. The need for specific education on transgender healthcare for psychologists was also highlighted by Case et al. (2009) who called for continuing professional development for teaching staff so transgender inclusion can feature across curricula. Similarly, Singh and dickey (2016) described a need for pedagogical innovations to meet the educational goals necessary to develop future generations of transgender-affirmative health professionals.

Past research with teaching staff of health professional education programmes has revealed that the main barriers to teaching about transgender healthcare or LGBTQ healthcare more widely are: 1) limited curricular time, 2) lack of institutional support, and 3) lack of expertise on transgender healthcare among faculty (de Vries et al., 2020; Dubin et al., 2018; Murphy, 2019; Taylor et al., 2018). A result of these barriers is a gap in the competencies within the workforce of health professionals and a lack of confidence to provide routine care for transgender patients let alone specialized care or referrals (Pearce, 2018; Snelgrove et al., 2012). Further research is therefore needed to understand how to break the cycle of health professionals who do not include transgender healthcare in their teaching because they do not feel confident to cover these topics and thus never have the opportunity to develop this confidence.

There is an ongoing need for exploratory research given the current limited status of knowledge about the perspectives of a wide range of teaching staff on the possibility of teaching trainee health professionals more about transgender healthcare. Specifically, there is a need to develop a deeper understanding of the personal and systemic barriers to teaching about transgender healthcare in order to develop solutions that work within existing curricula and help with planning of curriculum changes. The specific aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of both teaching staff from health professional education programmes and transgender community members on the best ways to teach about transgender healthcare. We took an interprofessional approach to gathering the data by working with teaching staff from a range of relevant health professional programmes in the specific discussion sessions we held with teaching staff and transgender community members. The health professional disciplines included in this study (medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, physiotherapy, and psychology) were selected on a pragmatic basis and reflect programmes taught at the site of the study. Education programmes for different health professions often involve shared pre-clinical years of education (Braun et al., 2017; Brondani & Paterson, 2011; Morris et al., 2019; Russell & More, 2016) and ongoing aspects of interprofessional education on various topics (Coleman, 2018; Kaste & Halpern, 2016; Pratt-Chapman & Phillips, 2020). We argue that foundational knowledge about transgender healthcare should be a required aspect of all health professional education programmes and there is therefore a need to explore perspectives on developing more teaching about transgender healthcare across different programmes. We addressed two broad sets of exploratory research questions: (1) What barriers do health professional programme teaching staff feel hold them back from teaching about transgender healthcare and how might these barriers be overcome? Are the barriers consistent across medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, physiotherapy, and psychology or are there any thematic differences across staff of different health professional programmes? (2) What ways might transgender community members be involved in teaching about transgender healthcare issues, what barriers might hold them back, and how might these barriers be overcome?

Method

Study design and consultation

This study involved an exploratory qualitative design to collect data from staff who teach trainee health professionals as well as transgender community members, and we applied established principles of inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The primary method of data gathering was focus groups, which work well when participants have varied perspectives (Krueger & Casey, 2014). The project was a collaboration between transgender community members and cisgender academic researchers, and we worked together on the design of the study and analysis of the data following recent guidance on involving the community at all stages of research (Bouman et al., 2018; dickey et al., 2016; Katz-Wise et al., 2019; Noonan et al., 2018; T’Sjoen et al., 2017; Veale et al., 2019; Vincent, 2018). The study was approved by the University of Otago’s Human Ethics Committee (reference H16/111).

We convened a broad research advisory committee of 33 members: 12 transgender people with various binary and non-binary genders and 21 cisgender people. The committee consisted of 12 staff teaching on a range of tertiary health professional programmes, three other university staff with relevant experience, four trainee health professionals, three external people who provide professional support for transgender people, three research assistants on the project, and eight community members outside these other roles. The committee were consulted about the study design, terminology, and focus group question during a committee meeting, individual meetings, and email exchanges prior to applying for ethics approval. This led to our research design of holding the first focus groups with transgender community members alone and then to invite ‘ambassadors’ from these groups to represent the transgender community in focus groups with teaching staff. Two sets of open-ended questions were devised to stimulate discussions in the focus groups (Table 1), one for the groups with transgender community members and one for the groups with teaching staff and transgender community ambassadors. The questions were developed by the first author drawing on existing literature and in consultation with the research assistants and others from the research advisory committee. Focus groups were also conducted with current trainees and were analyzed separately (see Hayward & Treharne, in press).

Table 1.

The questions posed in the focus groups.

| Order | Questions for focus groups involving only transgender community members |

| 1 | Can you tell us a bit about yourself such as what you do for a living? |

| 2 | Can you tell us which personal pronouns you use and a little bit about your gender? |

| 3 | How would you feel about a teaching role for transgender community members within health professional training programmes? |

| 4 | What do you think would be a good approach to teaching trainee health professionals about healthcare for transgender people? |

| 5 | Would you be willing to take on that kind of teaching role? |

| 6 | What kind of support do you think would need to be offered to transgender community members with a teaching role? |

| 7 | What do you think trainee health professionals could learn from being taught by transgender community members? |

| 8 | What would the ideal healthcare for transgender people look like? |

| 9 | To sum up, what do you think are the most important things trainee health professionals need to know when it comes to delivering healthcare for transgender people? |

| Order | Questions for focus groups involving teaching staff and transgender community ambassadors |

| 1 | Can you tell us what you do for a living or a bit about what programme you teach and a bit about your teaching role? |

| 2 | Can you tell us about your gender? |

| 3 | Can you tell us a bit about what is currently taught about providing care for transgender people? |

| 4 | What do you see as the responsibilities of teaching staff in providing education about healthcare transgender people? |

| 5 | How would you feel about a teaching role for transgender community members within health professional training programmes? |

| 6 | What modes of teaching would suit this teaching role? |

| 7 | What kind of characteristics or skills would be good for someone in that role to have? |

| 8 | What kind of support do you think would need to be offered to transgender community members with a teaching role? |

| 9 | How do you think trainee health professionals would respond to this kind of role? |

| 10 | What would the ideal healthcare for transgender people look like? |

| 11 | To sum up, what do you think are the most important things trainee health professionals need to know when it comes to delivering healthcare for transgender people? |

Procedures for focus groups and participants

The study was advertised via an invitation circulated to the research advisory committee to share with peers via email, noticeboards, social media, and word-of-mouth. The focus groups were conducted from November 2016 to April 2017 and led by a cisgender facilitator along with one of two research assistants, one of whom is cisgender and one of whom is transgender and has a non-binary gender. Three focus groups were held with transgender community members and six groups were held with teaching staff and transgender community ambassadors. Participants gave written informed consent and completed a confidential demographics questionnaire before the focus groups started. The facilitators introduced their roles in the research and their gender at the start of focus group discussion and asked participants to do the same. The focus groups lasted 55-105 minutes with the transgender community members alone and 45-80 minutes with teaching staff and transgender community ambassadors.

Details of the three core groups of participants are outlined in Table 2. Ten transgender community members participated in three groups without teaching staff present. In addition, five transgender community members participated as ambassadors in the six focus groups with teaching staff, three of whom had participated in previous focus groups and two of whom were briefed before participating. Of note, two of the five community ambassadors had previous experience supporting university teaching about transgender issues but none had extensive experience teaching in this area.

Table 2.

Demographics of the focus group participants.

| Group | Characteristic | Descriptive statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Transgender community members alone (three groups) | ||

| Number present per group | ||

| n = 2 present | One group | |

| n = 4 present | Two groups | |

| Age | Median 24.5 years | |

| 20-24 years old | n = 5 | |

| 25-50 years old | n = 3 | |

| 50-71 years old | n = 2 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | n = 3 | |

| Male | n = 1 | |

| Non-binary | n = 6 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | n = 3 | |

| White | n = 7 | |

| Transgender community ambassadors (at the six groups with teaching staff) | ||

| Number present per group | ||

| n = 2 present | Two groups | |

| n = 3 present | Four groups | |

| Age | Median 30.0 years | |

| 20-24 years old | n = 1 | |

| 25-50 years old | n = 3 | |

| 50-71 years old | n = 1 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | n = 3 | |

| Male | n = 1 | |

| Non-binary | n = 1 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | n = 1 | |

| White | n = 4 | |

| Experience teaching about transgender issues at university | ||

| None | n = 3 | |

| Some | n = 2 | |

| Teaching staff (six groups) | ||

| Number present per group | ||

| n = 2 present | One group | |

| n = 3 present | Three groups | |

| n = 5 present | One group | |

| n = 6 present | One group | |

| Age | Median 47.5 years | |

| 35-44 years old | n = 9 | |

| 45-54 years old | n = 8 | |

| 55-62 years old | n = 5 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | n = 18 | |

| Male | n = 4 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Pākehā (White) and Māori (the indigenous peoples of Aotearoa/New Zealand) | n = 1 | |

| White | n = 19 | |

| Declined to answer | n = 2 | |

| Main programme taught into | ||

| Clinical psychology programmes | n = 1 | |

| Dentistry programmes | n = 3 | |

| Medicine programmes | n = 9 | |

| Pharmacy programmes | n = 2 | |

| Physiotherapy programmes | n = 3 | |

| Public health programmes | n = 4 | |

| Experience teaching about transgender issues at university | ||

| Limited | n = 19 | |

| Some | n = 3 |

Twenty-two teaching staff participated in six focus groups along with the transgender community ambassadors. Two groups consisted of staff who teach into a single programme (medicine or physiotherapy), whereas four groups consisted of staff from two or more programmes in order to purposefully stimulate inter-professional discussion about similarities across core aspects of providing competent care for transgender people across different professions. The majority of students enrolled in health professional education programmes at the site of the present study enter from a shared pre-clinical year, and the health professional education programmes have close working ties and provide interprofessional education throughout clinical training.

The researchers met regularly during data collection and recurring patterns were noted after the six focus groups with teaching staff and transgender community ambassadors. The discussions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist working to a confidentiality agreement then checked for accuracy by one of the research assistants. Nonverbal behavior such as laughter is indicated within brackets. Pauses are marked with ellipses, whereas ellipses in square brackets indicate replacements or minor edits for clarification that maintain the intended meaning.

Data analysis

Within Braun and Clarke's (2006) model of different approaches to thematic analysis, our analysis was inductive because the themes were determined from the data rather than testing any preexisting theory. We applied a realist/essentialist epistemology in our analysis, meaning that we aimed to develop knowledge about participants’ experiences as expressed in the data (see Braun & Clarke, 2006). We sought semantic themes because the perspectives shared by participants are treated as reflections of their experiences by exploring the surface meaning of participants’ descriptions (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We applied Braun and Clarke's (2006) six phases of thematic analysis within a participatory framework (Treharne & Riggs, 2015) by facilitating the direct involvement of two transgender community members in the analysis, both of whom are coauthors on this report. In addition, four cisgender researchers contributed directly to the analysis and two other cisgender researchers contributed to developing and finalizing the analysis. Two of the three facilitators of focus groups contributed to the analysis. A series of meetings were held to facilitate familiarization with the data, development of codes within the data, organization of preliminary themes, collectively reviewing themes against allocated transcripts, defining the core nature of themes, and detailing the themes.

Results

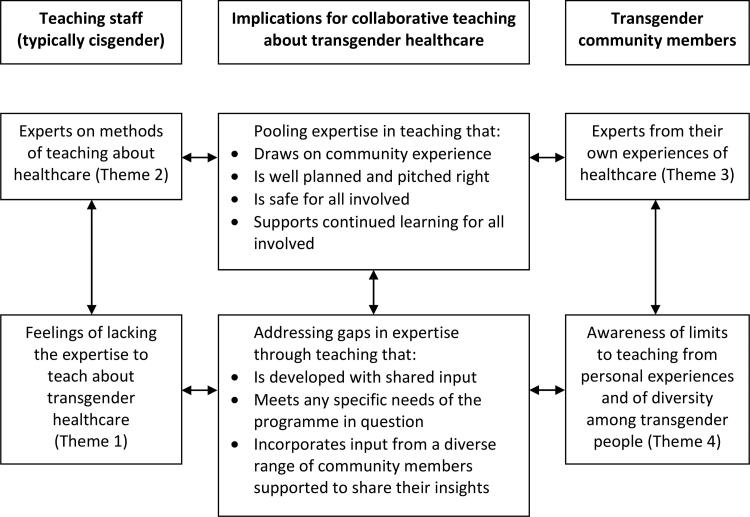

The aim of our analysis was to seek patterns across teaching staff regardless of the health professional education programme they taught into and no thematic differences were evident in perspectives of staff across the different programmes. Four themes developed from data that reflected the sense of both expertise and gaps/limits to expertise communicated by teaching staff and transgender community members. The themes are summarized in Table 3. All names that appear in the table and following coverage of the themes are pseudonyms. The first two themes focus primarily on the perspectives of teaching staff and the existing system of teaching, and both teaching staff and transgender community ambassadors contributed to these themes through the interactive discussions. The final two themes focus on insights transgender community members could bring to teaching about transgender healthcare, and these themes were also informed by the interactive discussions. Considerations about how transgender community members and existing teaching staff can collaborate in teaching feature throughout the findings and depicted in Figure 1, which indicates how the strengths and gaps in expertise expressed by both groups could be addressed in collaborative teaching.

Table 3.

An overview of the themes about expertise in teaching about transgender healthcare.

| Theme | Summary quotes (pseudonym and role) |

|---|---|

| 1: Teaching staff’s feelings of lacking expertise to teach about transgender healthcare |

That’s how I’ve learnt everything about it, from the students actually (Brendan, teaching staff) I don’t feel educated enough and I’d feel a bit like a fraud if I was in there teaching about transgender issues (Isabel, teaching staff) I’m happy to learn about it and find out about it and that’s what we should probably do with the students as well (Addison, teaching staff) |

| 2: Teaching staff’s feelings of expertise on methods of teaching about healthcare |

we’re always trying to make sure that we’re encouraging our students to be inclusive (Jocelyn, teaching staff) I think that small group [teaching] really lends itself to those kind of issues (Grace, teaching staff) Like meeting children, old age people, or people with some sort of disability; normal people with different kinds of experience regarding health issues (Delia, teaching staff) |

| 3: Transgender community members’ expertise on transgender healthcare |

it’s really important for us to find out what it is about a marginalized community that is specific, like what their needs are specifically (Alex, transgender community member) quite often the trans person has read far more than the medical profession about what’s happening [in healthcare] (Ellen, transgender community member) clinical values, hormone levels are important to remember when you’re dealing in the clinical setting but [when providing care] you are this profession first (Mike, transgender community member) |

| 4: Transgender community members’ awareness of limits to teaching from personal experiences |

the range of trans people is really quite huge so you just can’t take one person and use them as a typical example coz there is no typical example (Ellen, transgender community member) I talked about my story coz that’s the only story I can really talk about (Lisa, transgender community member) I think you need to […] ask as many different trans people as possible their stories (Ellen, transgender community member) |

Figure 1.

The connections between the four themes about strengths and gaps in expertise that inform the potential for collaboration between teaching staff and transgender community members.

Theme 1: “I don’t feel educated enough” – Teaching staff’s feelings of lacking expertise to teach about transgender healthcare

Throughout all of the focus groups, teaching staff across the different health professional education programmes consistently expressed feeling that they are lacking the expertise to provide teaching about transgender healthcare despite communicating a strong awareness of the need for this teaching. All of the teaching staff in the focus groups acknowledged gaps in their knowledge around healthcare for transgender people as well as gaps in their understanding of current terminology around gender identity and transitioning. As a case in point, during the introductions at the start of the focus groups many of the teaching staff discussed their lack of familiarity with the term cisgender and often resorted to laughing in a self-deprecating tone about this, as exemplified by the following exchange between teaching staff and the focus group facilitators:

Fern: I’m a cis female, just she/her.

Jane: I don’t even know what cis means (laughs).

Oliver: Mmm me neither.

Facilitator 1: So cis is a term that means the same side as.

These feelings of lacking the expertise to teach about transgender healthcare were linked to a desire to do well if engaging in teaching about transgender healthcare and an awareness of the very personal nature of gender identity. The teaching staff in all focus groups noted that they feel unprepared to teach safely about transgender healthcare; for example, Mel, who teaches about other aspects of health inequities explained: “I don’t have enough information to be able to [teach about transgender healthcare] and to do it well and respectfully”. Teaching staff also reflected on how their own clinical education had led to gaps in their knowledge about transgender healthcare because of the absence of coverage of this material even in recent decades, and again there was often a self-deprecating tone of humor to the discussions of these gaps in past approaches to education. For example, staff who teach mainly in the medical programme discussed how the lack of coverage of transgender healthcare leaves them feeling less knowledgeable than students:

Joan: And when I was going through medical school, there was nothing like this at all and so I kind of feel at a disadvantage (laughs) as well, because I think often the students are much more au fait with terminology and things than um my contemporaries.

Isabel: Yeah, I’d agree with that.

Kylie: Yeah so would I, just in terms of teaching the tutorials and other um that where you’re moving them from in terms of where they’re positioned on a continuum of knowledge or skills or attitudes is quite a different place now, I think they’re already here rather than here (signalling with hands).

Isabel: Yeah.

Matilda: And it has been quite a recent shift hasn’t it, like they’ve all got the language now and that they come to us knowing more than they used to.

Following on from these concerns about gaps in knowledge and awareness, both teaching staff and transgender community ambassadors suggested a need for continuing professional development. For example, Grace, who teaches in the medical programme highlighted that: “there’ll be a need for some really good staff development to go on”. And transgender community ambassador Mike noted: “Staff training before student training”.

Despite these gaps in knowledge and confidence, some teaching staff were in the process of developing transgender-related teaching or already delivering it. These participants expressed the importance of taking these first steps for them and the health professional programme they taught on. For example, Trish, who teaches in the medical programme argued that: “it’s that raising the issues as a place to start”. Moreover, Kylie explained some small shifts that had taken place recently such as actively including transgender characters in role play exercises and raising discussions about pronouns: “so we do different role plays and there are some suggestions around asking about pronoun use”. However, Kylie also noted that there was currently limited coverage of transgender healthcare, and this teaching tended to be grouped with wider coverage of LGBTQ health: “we also consider issues of gender in one workshop that’s associated with the group of sexuality lectures”. Limited space in curricula was raised as a barrier to teaching about transgender healthcare by some teaching staff but tended to be considered secondary to concerns about having the relevant expertise. Teaching staff and transgender community came up with solutions to barriers of limited space by proposing teaching a “strand throughout the whole curriculum” or focused blocks of teaching “because then at least we know they’re getting the information” (Kylie, teaching staff).

The relevance of learning to provide care for transgender people was regarded as of relevance across education for all health professionals who provide any form of face-to-face care. For example, Fern who teaches in a non-medical programme (masked to maintain confidentiality) noted that teaching about “the types of things that go wrong for people when dealing with healthcare professionals [is] exactly the sort of thing that the students should be considering, it’s not restricted to medicine”. The discussion was continued by Carla, who teaches in the medical programme and suggested “They could be doing yeah barriers to accessing healthcare for the transgender community that could be in co-partnership with the community organisation”.

The importance of making a start in teaching about transgender healthcare was also supported by transgender community ambassadors, all of whom were active in advocating for improvements to transgender healthcare although none were teaching in health professional programmes at the time of the focus groups. As a case in point, Mike, who attended several of the groups with teaching staff as a transgender community ambassador drew on his awareness of the international situation in health professional education when noting: “if anything, I think [teaching about transgender healthcare] is gaining momentum”.

Theme 2: “It’s about students seeing the reality” – Teaching staff’s feelings of expertise on methods of teaching about healthcare

Throughout all of the focus groups, the teaching staff expressed having expertise in a range of relevant aspects of pedagogical practice and were enthusiastic about using this expertise to develop appropriate ways of teaching about transgender healthcare with input from transgender community members in suitable formats. There was acknowledgement among the teaching staff and transgender community ambassadors in many of the focus groups that providing teaching about transgender healthcare would be straightforward for many trainee health professionals but could challenge the personal values of some. Therefore the idea of transgender community members contributing to teaching sessions was discussed as a suitable way to help trainees reflect on and build their values around professionalism. This kind of community contribution to teaching was also noted to demand a suitable teaching environment. Having skilled staff as a guide to teaching about values in small groups was emphasized by Grace, who teaches in the medical programme: “if it’s about value change, it doesn’t just happen […] it needs a lot of support so it needs very small groups, this kind of small [referring to the focus group of eight people], no bigger, and it needs very skilful facilitation”.

Some teaching staff noted aspects of their programme where they could apply their expertise in this kind of small group teaching to transgender healthcare in collaboration with transgender community members. For example, Bronwyn, who teaches in the clinical psychology programme explained “the ideal positioning would be probably the year that I’m working in which is their first professional year before they go out to say corrections or placements in the hospital or things like that and there’s a seminar series”. Teaching staff went on to demonstrate their expertise as teachers in discussion of the different teaching methods that could be used for teaching transgender healthcare. In particular, the teaching staff consistently advocated for small groups over large lecture-based formats to allow for easier discussion and reflection on community members’ experiences and stories. However, the following exchange between staff who teach mainly in the medical programme demonstrates how expertise on engaging audiences and use of technology can be applied regardless of the teaching format:

Isabel: The other problem with a large group is, speaking from experience, is that only a certain amount of [programme] students would feel comfortable asking questions in that large group as opposed to a more intimate environment where many of the medical students with a group of seven or eight colleagues would feel much more comfortable asking questions.

Rowena: That’s right. There are other ways of course, there’s those online, you know where you tweet a question through and it pops up on the screen.

Because most teaching staff had limited experiences teaching transgender healthcare, discussion about teaching methods often drew on comparisons with teaching involving other groups of community members. Many of the teaching staff had expertise on community-focused teaching and discussed how this might be applied to transgender healthcare. For example, Fern, who teaches in a non-medical programme (masked to maintain confidentiality) explained how she could apply her expertise in community-engaged teaching: “Ok, I think for me, my focus being bringing patients into this school for students to interact in […] an artificial but real life situation, that would be perfect because […] for us it’s about students seeing the reality of interacting with the person”. Teaching staff who attended the focus groups were mindful of seeking community input when developing new teaching initiative that apply their skills in teaching in collaboration with community members. Joan, who teaches in the medical programme emphasized that any teaching with involvement of transgender community members would “have to be probably developed in co-ordination, you know like linked in together and everything […] so I couldn’t just write something and then have someone from the transgender community come in”.

Another suggestions for a modality of teaching that participants raised was specifying details of case studies to include hypothetical transgender individuals. For example, Alex who attended all of the focus groups with teaching staff as one of the transgender community ambassadors outlined what might be learnt from a case-study teaching format as part of a discussion about the relevance of transgender identity in various healthcare situations:

I personally really like the idea of putting transgender people in this like theoretical case study that people look at… because it would really give you, if it wasn’t relevant, that the person was trans, it would give you just a regular question to ask and you would learn that that student has picked up on how to deal with a hip replacement but if they also say, well I need to investigate if this person has got hormones from their doctor which may impact the way that their bones have aged, just like if a woman is on Premarin [a brand of female hormone supplementation] for menopause, like it’s not really any different, it’s just you’re on this medication, I need to know how that’s going to impact on future surgery so it actually gives another level to it that if they understand what trans people’s medical needs are.

Theme 3: “Often the trans person has read far more” – Transgender community member’s expertise on transgender healthcare

In addition to their contributions to the discussions about strengths and gaps in expertise among teaching staff, all of the transgender community ambassadors positioned themselves as having expertise that could be applied in collaborative teaching primarily from a place of lived experience of transgender healthcare. One of the main ways that transgender community ambassadors communicated their sense of expertise about transgender healthcare was by explaining to the focus groups how they have often needed to fill the gaps in knowledge of health professionals they had interacted with. As a case in point, the term cisgender was unknown to many teaching staff present in our focus groups, and was explained etymologically by a transgender community ambassador, Alex: “Yeah it’s originally a chemistry term; trans meaning across and cis meaning the same side of”.

In another example of transgender community ambassadors communicating their expertise on transgender healthcare, Ellen, who attended most of the focus groups with teaching staff as a transgender community ambassador noted the role of administrative staff in reducing the need for transgender people to educate their own health professionals: “make sure you make friends with the receptionist, they’re often more important than the medical professional to have a comfortable experience”. And in the most extreme case, Lisa, who also attended most of the focus groups with teaching staff as a transgender community ambassador explained how she had been asked to advise other transgender people who were patients of a health professional she was being treated by: “I was being asked to help some of her clients because she didn’t have the understanding of it”. At the same time, Lisa was happy to advise another health professional who engaged with her as an expert and sought consent to do so: “any time she wanted to learn something about gender, about transgender, she actually asked me if it was ok and I actually really appreciated that”.

Transgender community ambassadors in all of the focus groups expressed considerable frustrations about ongoing inadequacies of local and global healthcare for transgender people. Although the transgender community ambassadors had a range of educational levels and work backgrounds, they all discussed how they needed to attend consultations prepared to be pro-active about their current health needs because health professionals they have interacted with do not ‘take charge’ of meeting a transgender person’s healthcare needs. For example, Ellen explained: “you actually have to go to the doctor and say ‘Look I’ve been off hormones for three months after the surgery, I want to go back on, I hear that I should have a bone density test first, can you help me arrange that?’ rather than saying ‘I’ve come back from surgery, what do I do next?’ And finally, you tell me where I can find a gynecologist in [city] that deals with trans people, trans females!”.

Despite these frustrating experiences, all of the transgender community ambassadors were eager to be involved in teaching to ensure that transgender healthcare be seen as a “legitimate sort of issue to be aware of”, as put by Harper, one of the transgender community ambassadors who attended several focus groups. Transgender community ambassadors also discussed a range of healthcare scenarios in which the patient’s gender identity and transition status could be vital for health professionals to know. However, several of the transgender community ambassadors explained a common phenomenon wherein a health professional becomes distracted by the person’s transgender identity or does not know whether it is relevant to a clinical situation. As Ellen explained: “you break your arm, you rush into the emergency department and they say ‘Oh, you have a broken arm,’ and then they realize you’re trans […] ‘Well I’ve never dealt with a trans person with a broken arm before.’”. Following on from these scenarios being raised by transgender community ambassadors, some of the teaching staff also noted that health professionals experience barriers to providing care when they feel unaware about whether or not transgender identity is relevant to particular healthcare scenarios. For example, Joan, who teaches in the medical programme noted: “[Some health professionals who struggle with communication] then shut down, they’re like ‘I’m not too sure what to do’ rather than realizing that they shouldn’t have been doing anything different”.

In summing up the key values behind healthcare that need to be developed in health professional education, Grace (who teaches in the medical programme) and Mike (a transgender community member) raised the following points, which demonstrate the collaborative insights that could be drawn on in teaching involving transgender community members:

Grace: It’s kind of universal isn’t it? It’s kindness.

Mike: Yep, professionalism, whenever of all of the sections that I feel like it needs to be touched on in the training programmes, it’s the ethics professionalism, um how you treat your patients with kindness, equal opportunity, what have you, I mean that carries and covers a whole lot more than anything like specifically, like as long as you’re kind to me, even if you mess up, I know you’re trying.

Theme 4: “The range of trans people is really quite huge” – Transgender community members’ awareness of limits to teaching from personal experience

All of the transgender community ambassadors positioned themselves as having become experts on transgender healthcare out of necessity. This sense of expertise was based primarily on their own experiences of healthcare but with consistent acknowledgement across all of the transgender community ambassadors that when they describe their experiences of healthcare they do so as one individual within the diverse range of transgender people living in a particular location. Moreover, the transgender community ambassadors and teaching staff noted that not all transgender people want to be involved in teaching health professionals because even for those who would be keen to contribute to teaching it can be “nerve wracking” (Lisa, transgender community ambassador) and even with good support from collaborating teaching staff it is possible that transgender people could be left feeling “unhappy or unsettled” (Rory, teaching staff) by comments or questions from students after talking about their experiences in a teaching session.

Several of the transgender community ambassadors took the opportunity during the focus groups to describe their healthcare experiences and share their personal stories. These participants emphasized why they are only able to speak to their own experiences in focus groups or if they engaged in teaching. For example, Lisa, a transgender community ambassador who had previously given a guest lecture about transgender identities in a university programme outside of health professional education noted that she drew on her experience:

Mike: [Small group teaching is] less impersonal than a lecture.

Trish: Precisely, thank you (laughs).

Lisa: I mean you give a speech, I did one for the university, for the [department] and it was, I talked about my story coz that’s the only story I can really talk about, you can’t talk about anybody else’s and then students were able to ask questions, and it touched on some really raw stuff, made some people really like ‘Wow, shit, does that actually happen in New Zealand?’ But it actually brought-, and then they were able to ask questions after that.

Several: Mmm.

Addison: Well this is why = it’s quite good = to get this out, you know so people do know what happens.

Other transgender community ambassadors, particularly those who shared their story in detail across several of the focus groups, highlighted being limited to telling their own story when teaching about healthcare experiences: “I represent one particularly narrow view […] The needs I have are different to the needs of the young person just starting out in life” (Ellen, transgender community member). Perspectives on teaching from personal experience of transgender healthcare also centered on a strong emphasis on the rich diversity within transgender communities: “they do need to know that everyone’s story is different […] and one case study doesn’t prepare you for anything like that” (Ellen, transgender community member). Transgender community ambassadors noted that age, employment, and socioeconomic status all relate to ability to pay for healthcare, particularly to gender affirming treatments. For example, Ellen outlined how her experience of transitioning was different to younger people’s and was facilitated by being able to pay directly for surgeries in another country because at the time there were no surgeons conducting genital surgeries in Aotearoa/New Zealand and a decades-long waiting list to access public funding for surgery: “I could afford to pay to get it done and that gives you a degree of confidence you don’t have relying on the system to do it”.

Transgender community participants were also emphatic about ensuring a diverse cross-section of community members in teaching by overcoming barriers to involvement in teaching and development of trust between community members and those organizing teaching. For example, Ellen and Lisa explained their perspective on engaging more reticent transgender community members in teaching and received reflection from Grace, a member of teaching staff:

Ellen: The problem you will have also is people like [other transgender community ambassador] and myself and [other transgender community ambassador] are all willing to be out there and talk about [transgender healthcare, but] you need to also meet the people who are less comfortable.

Lisa: It’s hard to do.

Ellen: Yeah because I don’t represent anything more than one person, you really do need to meet the ones who are much more shy or more sorted and stealth about it than we are.

Grace: In a more general sense, I think that those people may be helped by what you guys are doing.

Lisa: That’s right.

Discussion

There is increasing recognition that health professionals from all healthcare discipline are duty-bound to provide care for transgender people in their routine practice, and it is therefore essential to provide health professionals with the specific education to be confident in providing this care (Byne et al., 2018; de Vries et al., 2020; Obedin-Maliver et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2018; Veale et al., 2019; Winter et al., 2016; Wylie et al., 2016). In this study we addressed pressing research questions about the barriers that result in the currently limited provision of education about transgender healthcare for trainees across a range of health professional education programmes. Our focus group method brought together teaching staff from a range of health professional education programmes and transgender community members in a process that resulted in an interprofessional corpus of data as well as an interprofessional environment in the focus groups, the majority of which involved staff who teach into different health professional education programmes. Overall, our process of thematic analysis involving collaboration between transgender and cisgender researchers revealed that both teaching staff and transgender community members have aspects of expertise and are enthusiastic about working together to develop teaching on transgender healthcare that draws on their respective sets of expertise. At the same time, both teaching staff and community members acknowledged the constraints of their expertise that created the feeling that they alone cannot provide this teaching to an appropriate breadth and depth. There was thematic consistency across teaching staff from the participating health professional education programmes, who all expressed very similar perspectives about feeling they lack the expertise to teach about transgender healthcare. These findings provide in-depth perspectives on a core barrier to teaching about transgender healthcare that helps to explain the currently limited provision of this teaching across health professional education programmes, which is a global issue (de Vries et al., 2020; Desrosiers et al., 2016; Dubin et al., 2018; Obedin-Maliver et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2018). Our findings also provide practical ideas for implementing community-engaged teaching about transgender healthcare that could bring together expert teaching staff and experts by experience from transgender communities.

The findings of this study provide timely and novel insight into considerations for teaching about transgender healthcare that align with and add to existing research and theory around transgender healthcare (Byne et al., 2018; de Vries et al., 2020; Ellis et al., 2015; Obedin-Maliver et al., 2011; Pearce, 2018; Taylor et al., 2018; Veale et al., 2019; Winter et al., 2016; Wylie et al., 2016). The four themes provide much-needed insights into how to break the cycle of health professional education programmes not including transgender healthcare when teaching staff do not feel expert enough to cover these topics and thus never have the opportunity to develop this expertise. The themes also provide a picture of the synergistic aspects of expertise that teaching staff and transgender community members could bring to collaborative teaching. These findings expand on the limited body of past research on pedagogical innovations in foundational or advanced teaching about transgender healthcare (for comprehensive reviews, see Desrosiers et al., 2016; Dubin et al., 2018). Previous evidence suggests panel discussions involving transgender community members can be an effective component within required courses for trainee dentists (Brondani & Paterson, 2011) and pharmacists (Parkhill et al., 2014) and within elective courses for a range of trainee health professionals learning together in an interprofessional education setting (Braun et al., 2017; Pratt-Chapman & Phillips, 2020). Curriculum development resources are an important way of sharing concrete tools for teaching about transgender healthcare. For example, the guidance developed by the Association of American Medical Colleges (Hollenbach et al., 2014) provides clinical scenarios, discussion points, and assessment tools relating to transgender healthcare among other aspects of teaching about LGBTQ healthcare and intersex variations. Further guidance is required on how teaching staff of specific health professional programmes and transgender community members can collaborate on teaching in ways that are effective and safe for all involved. These initiatives might ideally be led as a collaboration between transgender community members and teaching staff who have expertise in gender affirming care with oversight or input from professional associations such as the Professional Association for Transgender Health Aotearoa (PATHA) in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

Teaching staff and transgender community members in this study emphasized that teaching about transgender healthcare requires careful planning to ensure good pedagogical outcomes and safety of all involved, particularly any transgender community members contributing to teaching who may face difficult scenarios including potential overt discrimination from students or being asked to speak on behalf of transgender people in a way that does not facilitate consideration of diversity of identities and experiences. These findings add a new level to recent research indicating that careful teaching about values-related issues facilitates personal growth of the learner (Gamble Blakey & Pickering, 2018; Gamble Blakey & Treharne, 2019). Values-related teaching supports health professionals to reflect on the values they bring to clinical practice and their professional duty to treat all patients with respect (Gamble Blakey & Pickering, 2018), which is particularly pertinent in learning to provide care for transgender people (Gamble Blakey & Treharne, 2019). Our findings also expand on Stroumsa et al.'s (2019) cross-sectional survey research showing that practicing health professionals holding more positive personal values about transgender people demonstrate greater expertise about core aspects of transgender healthcare. In particular, our findings demonstrate that teaching staff who participated are keen to develop greater expertise on transgender healthcare but have gaps in their foundational knowledge.

The findings of this study also add depth to previous research that has revealed the limited coverage of transgender healthcare or any aspect of LGBTQ healthcare in health professional education internationally (Dubin et al., 2018; Graham et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2019; Obedin-Maliver et al., 2011; Pratt-Chapman & Phillips, 2020; Taylor et al., 2018). Our findings also align with theories of transgender people’s wellbeing including gender minority stress and decompensation in the face of stress (Riggs et al., 2015; Riggs & Treharne, 2017; Tan et al., 2020). The transgender participants in our study discussed regularly providing education during their own healthcare consultations, which is an educational burden that has been found in past research (Jaffee et al., 2016; Riggs et al., 2014; Schimanski & Treharne, 2019). Most of the transgender participants in this study did not mind providing education at the same time as receiving care, but this finding may reflect the willingness to discuss being transgender among those who attended our focus groups. The educational burden during consultations is worrying because past research indicates that some transgender people delay or avoid healthcare for this reason (Chipkin & Kim, 2017; Jaffee et al., 2016; Riggs et al., 2014; Schimanski & Treharne, 2019). The findings of our study demonstrate how transgender community ambassadors who participated had developed expertise on transgender healthcare out of necessity and were willing to contribute to education at a more suitable time than their own consultations. At the same time, it is important to develop ways of ensuring that formal involvement of transgender community members in delivering health professional education does not perpetuate the kind of educational burden that often arises during for transgender people during their own healthcare consultations. It is also important to address considerations around appropriately remunerating transgender community members who contribute to teaching by instigating contracts for formal teaching roles and ensuring funding for appropriate pay.

Transgender participants in our research expressed the feeling that their expertise was limited to their own experience, which raises questions about how to include coverage of a diversity of transgender identities within teaching on transgender healthcare. Representing the diversity within transgender people has been recognized in pedagogical research and teaching on transgender healthcare (Green, 2010; T’Sjoen et al., 2017). Education on transgender healthcare must provide health professionals with the skills to respond to a patient’s uniqueness, as with all aspects of health professional practice (Wilson & Cunningham, 2014), and this must therefore be reflected in the content of education of health professional education about transgender healthcare and the diversity of community members who are involved in any such teaching. The findings of our study build on the insights developed by Pearce (2018) on provision of transgender healthcare in the UK that raised the various ways that expertise among transgender people shapes healthcare in practice through “collective discursive interventions from within trans communities” as well as input from “activist-experts” and “insider-providers” alongside “sympathetic cis professionals” (p. 201). The transgender community ambassadors in our study demonstrate a particular form of activist expertise in their willingness to draw on their own experience to contribute to future teaching activities to assist teaching staff who do not yet have a sense of expertise on transgender healthcare in a location that also lacks in insider-providers (i.e., transgender health professionals who work as teaching staff).

Our findings contribute to understanding how to seek wider input from “patients as ‘experts’” in health professional education (Jha et al., 2009, p. 10), which stems from any group of community members having “in-depth knowledge and motivation to use their expertise” (Jha et al., 2009, p. 14). We argue that the input of transgender community members needs to be recognized as an important part of trainee health professionals developing both an evidence-based and community-based understanding of what transgender healthcare should entail. Transgender community members have the potential to offer trainee health professionals a rich and memorable learning experience (Braun et al., 2017; Brondani & Paterson, 2011; Parkhill et al., 2014; Pratt-Chapman & Phillips, 2020) as has been found with many other aspects of healthcare education that draw on the experiential expertise of relevant community members and/or patients such as people living with arthritis (Jha et al., 2009).

Based on the input from the transgender community members and teaching staff who participated in this study we are able to make some preliminary recommendations about collaborative teaching that addresses respective sets of expertise and how these can be drawn on in a safe fashion, as summarized in Figure 1. The notion of safety in collaborative teaching was centered on ensuring that any transgender community members involved in teaching were appropriately supported. Our transgender participants noted that teaching would only be appropriate for transgender people who are comfortable talking to the size of student audience in question. This raises questions about how soon after undergoing surgery or commencing a form of treatment a community member might be safely positioned to be involved in teaching about transgender healthcare in general or specific to that treatment. Another recommendation arising from this study is that teaching should incorporates input from a diverse range of transgender community members. Attempting to ensure diversity among the transgender people contributing to a specific teaching activity or an overall programme of teaching also relates to safety by ensuring that no single community member feels expected to represent all transgender people as per our findings on feelings about limits to expertise when telling one’s own story in healthcare professional education.

In addition, recommendations about the importance of ensuring safety were expanded beyond the transgender community members involved in potential teaching activities and reflect the need for teaching staff to be supported to develop insights into the relevant evidence required to feel expert enough to teach about the particular aspect of transgender healthcare and the resulting safe learning environment for students too. This recognition of the need for continued learning fits with broad approaches to professional development for teaching staff (Gamble Blakey & Pickering, 2018; Hollenbach et al., 2014) and expands to all involved any teaching activities, including transgender community members. Another recommendation is to ensure that both transgender community members and teaching staff have an appropriate level of shared input in developing any specific teaching session about transgender healthcare so that both parties have clear expectations and to tailor the teaching to the particular programme and the stage of education of the trainees. Teaching staff and transgender community members also emphasized the importance of good planning in terms of selecting a suitable teaching modality and pitching the teaching session at the right level for the stage of education whilst also recognizing any previous education on transgender healthcare or LGBTQ healthcare that students have engaged in.

This research has a range of strengths and limitations. The involvement of a research advisory committee was a strength and our collaborative inclusion of transgender community members throughout the research process meets the call for in-depth research on the potential roles of patient educators (Towle et al., 2010) and builds on emerging best practices for community involvement in transgender-related research (Bouman et al., 2018; dickey et al., 2016; Katz-Wise et al., 2019; Noonan et al., 2018; T’Sjoen et al., 2017; Veale et al., 2019; Vincent, 2018). In relation to the criteria for inclusion of transgender community members in research described by Vincent (2018), our study involved researchers who were ideally positioned to apply knowledge of the local history of transgender healthcare in the study, and we applied terminology, focus group questions, and project roles that were deemed suitable by the local transgender community.

The use of focus group methodology is another strength of this study because it allowed the transgender community members and teaching staff to have frank discussions about aspects of their expertise and gaps in expertise and consider each other’s perspectives. Our process of running focus groups validated the identities of the transgender people present and allowed teaching staff to learn about terminology and priorities during the focus groups. The collaborative analysis is also a strength of this study and involved many of the people who had been involved in the focus groups and represents the insights of transgender community researchers who contributed throughout the research. Having a breadth of data from teaching staff across the different health professional education programmes was a strength that allowed us to demonstrate provisional insights into the consistency of perspectives on expertise that we discovered across the teaching staff. Four of the six focus groups involved teaching staff from more than one health professional education programme and this also added to the breadth of discussions by encouraging interprofessional considerations among teaching staff from different professional backgrounds. Future research is now needed to explore specific issues relating to developing expertise on transgender healthcare that addresses the specific teaching needs of individual professions and builds on these findings and past research demonstrating successful outcome of pedagogical innovations in different health professional education programmes (Braun et al., 2017; Brondani & Paterson, 2011; Desrosiers et al., 2016; Dubin et al., 2018; Ostroff et al., 2018; Parkhill et al., 2014; Park & Safer, 2018; Pratt-Chapman & Phillips, 2020).

The focus group method also has some limitations in that the discussions were restricted by time constraints and only captured perspectives at one point in time. This timepoint was typically prior to teaching staff having attempted any substantive planned teaching on transgender healthcare and much of the discussion was therefore hypothetical about how the teaching might proceed in practice. The transgender community ambassadors had limited prior experience of teaching in a university setting to draw on, and perspectives may differ among transgender people who have been more extensively engaged in teaching of trainee health professionals. It would be ideal to continue to interview teaching staff and transgender community members as they started teaching initiatives in the future to hear about their unfolding reflections and how they hone the teaching. The focus groups varied in size with some having a relatively large number of attendees from various health professionals education programmes, which can make it hard for everyone to contribute, particularly if their views diverged from others present. There are also unanswered questions about the perspectives of teaching staff who were unwilling to participate who may have less positive views of teaching about transgender healthcare.

Most participants in this study were White and female, particularly among teaching staff, which implies possible self-selection bias in willingness to participate. All teaching staff who participated in focus groups have cisgender gender identities, and many identified a need for introductory level professional development education for themselves. Future research could address the provision of such professional development and explore the experiences of transgender teaching staff given that all teaching staff in the focus groups were cisgender. Our sample did not include teaching staff from all health professions and future research could benefit from wider coverage and focused exploration of the educational needs relating to transgender healthcare for specific professions. The sample was also limited to a university in one region of Aotearoa/New Zealand but did not appear to differ from past research for other countries and this study provides useful in-depth insights that can be replicated in ongoing research with teaching staff and transgender community members in other regions.

Conclusions

This study reiterates the need for teaching staff of health professional programmes to be well-versed in transgender healthcare and considerations for teaching about values-related issues, which may necessitate support for teaching staff in developing their values around equity and inclusion of transgender people. The potential challenges and opportunities for pedagogical innovations expressed by participants in this study suggests a need for specific guidance on best pedagogical practice about providing teaching about transgender healthcare for a range of health professional programmes. Such guidance may benefit from specific focus on the potential role for transgender community members contributing to teaching based on their personal experiences of healthcare and wider social aspects of the ongoing discrimination faced by transgender people. The study adds to the small but growing body of pedagogical research providing applied knowledge about how to enhance teaching about transgender healthcare that addresses the unmet need expressed by Veale et al. (2019, p. v), who recently emphasized that there is a growing requirement to “create clear pathways for gender-affirming healthcare, including training, resources and culturally appropriate services”. These needs can only be met by teaching for trainee health professionals that draws on a sense of expertise in teaching about transgender healthcare.

Health professionals have the ethical duty to provide equitable healthcare for all of their patients, which necessitates a solid foundation of knowledge about what it means to be transgender and the specific and general provision of healthcare for this segment of the population. Teaching staff and transgender community members in our study expressed a sense of lacking the expertise to teach about transgender healthcare in distinct ways whilst also having a strong sense expertise on teaching methods or from their own experience as transgender people that could be pooled to provide an ideal combination of expertise and ground-breaking education about transgender healthcare for the next generation of health professionals.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants who contributed to this research as well as the research advisory committee who guided the research and others who contributed to recruitment. The study was funded by the University of Otago’s Division of Sciences and Committee for the Advancement Learning and Teaching.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by University of Otago Division of Sciences; University of Otago Committee for the Advancement Learning and Teaching.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethics approval for the study was granted by the University of Otago’s Human Ethics Committee (reference H16/111).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Bouman, W. P., Arcelus, J., De Cuypere, G., Galupo, M. P., Kreukels, B. P., Leibowitz, S., … Veale, J. (2018). Transgender and gender diverse people’s involvement in transgender health research. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(4), 357–358. 10.1080/15532739.2018.1543066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, H. M., Garcia-Grossman, I. R., Quinones-Rivera, A., & Deutsch, M. B. (2017). Outcome and impact evaluation of a transgender health course for health profession students. LGBT Health, 4(1), 55–61. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondani, M. A., & Paterson, R. (2011). Teaching lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender issues in dental education: A multipurpose method. Journal of Dental Education, 75(10), 1354–1361. http://www.jdentaled.org/content/75/10/1354.long 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2011.75.10.tb05181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byne, W., Karasic, D. H., Coleman, E., Eyler, A. E., Kidd, J. D., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Pleak, R. R., & Pula, J. (2018). Gender dysphoria in adults: An overview and primer for psychiatrists. Transgender Health, 3(1), 57–70. 10.1089/trgh.2017.0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case, K. A., Stewart, B., & Tittsworth, J. (2009). Transgender across the curriculum: A psychology for inclusion. Teaching of Psychology, 36(2), 117–121. 10.1080/00986280902739446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chipkin, S. R., & Kim, F. (2017). Ten most important things to know about caring for transgender patients. The American Journal of Medicine, 130(11), 1238–1245. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, K. (2018). Interprofessional education: Learning with, from, and about one another. Radiologic Technology, 90(2), 200–203. http://www.radiologictechnology.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=30420581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, E., Kathard, H., & Müller, A. (2020). Debate: Why should gender-affirming health care be included in health science curricula? BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12909-020-1963-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahunt, J. W., Denison, H. J., Kennedy, J., Hilton, J., Young, H., Chaudhri, O. B., & Elston, M. S. (2016). Specialist services for management of individuals identifying as transgender in New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal, 129(1434), 49–58. https://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/read-the-journal/all-issues/2010-2019/2016/vol-129-no-1434-6-may-2016/6882 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers, J., Wilkinson, T., Abel, G., & Pitama, S. (2016). Curricular initiatives that enhance student knowledge and perceptions of sexual and gender minority groups: A critical interpretive synthesis. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 7(2), e121–e138. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5344050/ 10.36834/cmej.36644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]