Abstract

Background:

Hemorrhagic cholecystitis (HC) is a rare complication of acute cholecystitis. HC is difficult to diagnose pre-operatively and previous case reports suggest a strong association with anticoagulation and an increased morbidity. The purpose of the study is to determine the clinical presentation and outcomes of patients with HC in a large cohort of patients.

Method:

A retrospective review of HC patients diagnosed following review of the clinical and pathological database between January 1, 2000 – June 30, 2021 at two hospitals. A search of the histopathology database, patient medical records, laboratory results, and imaging was conducted.

Results:

Thirty-five patients were diagnosed on the histopathology report from approximately 6458 patients who had cholecystectomies. Thirty-one had emergency presentation and four patients (11.4%) had elective surgery. Twenty-one patients (60%) were female and 15 patients (40%) were male. The median age was 51 years. All patients had laparoscopic cholecystectomy, four patients were converted to open and five patients required postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Two patients (5.7%) were on anticoagulation therapy. Twenty-three (65.7%) had ultrasound, 12 patients (34.2%) had computed tomography, three patients (8.5%) had magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and one patient with a pre-operative diagnosis of HC.

Conclusion:

HC is a rare form of acute cholecystitis. Anticoagulation only accounts for a small fraction of these patients. Pre-operative diagnosis of HC is not often made. Patients were treated with cholecystectomies and made a full recovery with no complications. Our study seems to show HC is a histological diagnosis with no clinical consequences for the patients.

Keywords: Gallbladder, Cholecystitis, Hemorrhage, Ultrasound, Computed tomography, Cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Acute cholecystitis is a common general surgical emergency. Gallstones are a common cause of acute cholecystitis with some patients presenting with acalculous cholecystitis. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis (HC) is a rare type of acute cholecystitis that seem to carry a high morbidity and mortality rate based on case reports. Its clinical course can mirror that of acute cholecystitis. Characteristic findings on ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan are useful clues to early diagnosis. Urgent cholecystectomy is required prior to progressing to perforation of gallbladder.2

In the literature, HC has been described as a separate pathological entity only in case reports. We present the largest series of patients with HC and describe the causes, clinical presentations, imaging, and outcomes of management.

METHOD

A retrospective review of all patients diagnosed with HC from the pathological database as well as clinical records of patients who presented to our hospitals between January 1, 2000 and June 30, 2021 was performed. We excluded patients with hemorrhage due to trauma. The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (27–2021). The patients’ clinical records were reviewed with review of the presentation, investigations, treatment, and pathological assessment. Patients who were managed nonoperatively and patients who had percutaneous cholecystostomies were excluded.

RESULTS

During the study period, 6458 patients underwent cholecystectomy of which 35 patients were identified with HC (Figure 1A and 1B). The overall incidence of HC is 0.55%. The median patient age was 51 years (range 36 – 83 years), with females, n = 20 (60%) and males, n = 15 (40%). Thirty-one patients (88.6%) were emergency presentations with clinical presentation of cholecystitis or biliary colic. Four patients (11.4%) were admitted for elective procedures.

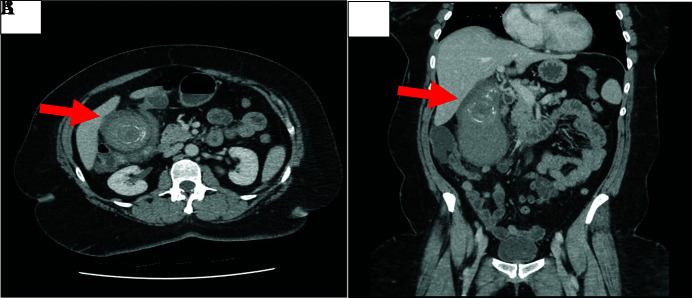

Figure 1.

(A) Gall bladder wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid both features compatible with acute hemorrhagic cholecystitis. (B) Coronal view of gall bladder with high density fluid and calculi.

The median hemoglobin level was 135 g/L (range105 – 165 g/L). Raised inflammatory markers were noted with raised white cell count in 25 patients (71.4%) and raised C-reactive protein in 27 patients (77.1%). Nineteen patients (54.3%) had deranged liver function tests; 16 patients (45.7%) had normal liver function tests. Only two patients (5.7%) were on anticoagulation therapy. Pre-operative investigations included ultrasound in 23 (65.7%) patients, CT scan 12 (34.2%) patients, and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in 3 (8.5%) patients (Table 1). Only one patient had a pre-operative diagnosis of HC.

Table 1.

Patient Presentations

| Number of Patients | Percentage % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 20 | 60 |

| Male | 15 | 40 |

| Presentation | ||

| Acute prevention to emergency department | 31 | 88.6 |

| Elective | 4 | 11.4 |

| Inflammatory markers and LFT | ||

| Raised CRP | 27 | 77.1 |

| Raised WCC | 25 | 71.4 |

| Deranged LFT | 19 | 54.3 |

| Normal LFT | 16 | 45.7 |

| Anticoagulation | 2 | 5.7 |

| Imaging modality | ||

| Ultrasound | 23 | 65.7 |

| Computed tomography | 12 | 34.2 |

| Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography | 3 | 8.5 |

| Treatment | ||

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 31 | 88.6 |

| Conversion to open cholecystectomy | 4 | 11.4 |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography | 5 | 14.2 |

LRT, liver function test.

The 31 patients (88.60%) with emergency presentation were treated with broad spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics; 28 received Ceftriaxone and Metronidazole while three patients received ampicillin, gentamycin, and metronidazole. All patients were managed with nil per os and IV fluids and thromboprophylaxis. Four elective patients (11.40%) had a single pre-induction dose of 2 grams Cefazolin.

All patients underwent a cholecystectomy with 31 (88.6%) having a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and 4 patients (11.4%) converted to open. The intraoperative findings are summarized in Table 2. Five patients (14.2%) had a postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The median length of stay was 4 days (range 2 – 10 days). All patients recovered without complications with no mortality.

Table 2.

Operative Findings

| Intraoperative Finding | Number of Patients | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Mucocele | 8 | 22.3% |

| Gangrenous gall bladder | 6 | 17.1% |

| Empyema of gall bladder | 4 | 11.4% |

| Gall bladder perforation | 2 | 5.7% |

DISCUSSION

HC is a rare type of acute cholecystitis. Acute cholecystitis is a common presentation in emergency departments (ED) with approximately 5% of ED visits and 3% – 9% of hospital admissions.3 The common etiology of acute cholecystitis is gall stone in more than 90% of the patients3 and the others with acalculus cholecystitis. It requires prompt diagnosis and treatment as any delay in treatment may increase morbidity and mortality.2

Shah and Clegg first described haemobilia caused by cholecystitis as hemorrhagic cholecystitis.4 It is a rare disease with a previously estimated incidence of 7% based on case reports,2 but our larger series shows the incidence is much lower at 0.55%.

The pathogenesis of HC is not clear, but it is thought to be most likely caused by an inflammatory process that consequently causes mucosal break down and erosion into gall bladder vessels causing hemorrhage or gangrene. Rarely there is perforation with hemorrhage into the abdominal cavity.5 Alternatively an impacted stone at the gall bladder neck causes an obstruction accompanied by inflammation and gall bladder distention, ultimately leading to necrosis or perforation of gall bladder.3

Bleeding into the gall bladder could manifest as perforation of the gall bladder with or without hemoperitoneum, haemobilia with or without obstruction of the biliary tract, and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding as hematemesis and melena.3,5–7 There have been rare presentations with obstructive jaundice8 and a case report of a pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with bleeding into the gall bladder with active extravasation on CT scan.9 On rare occasions HC has been reported with acalculous cholecystitis.10

The reported risk factors associated with HC include anticoagulation therapy, malignancies, coagulopathies, history of trauma, renal failure, and cirrhosis. Another documented possible risk factor is long term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use.11 Anticoagulation therapy has been a risk factor in 45.2% of patients in the case reports; however, this was only seen in 5.7% of patients in our study.

Patients typically present for acute cholecystitis or biliary colic with right upper quadrant pain, fever, raised inflammatory markers, and positive Murphy’s sign.12 Some patients may present with bleeding and low hemoglobin when there is active hemorrhage due to a ruptured aneurysm and hemoperitoneum. Abnormal liver function test with an obstructive pattern may be due to clot in the biliary tract obstruction. Presentation of upper abdominal pain, jaundice, and upper GI bleeding (i.e., Quincke's triad) is due to hemobilia.7 No patients in our study presented with Quincke's triad.

Ultrasound is the gold standard for imaging of the biliary disease. Ultrasound of the abdomen typically demonstrates one of the following sonographic features like intraluminal membrane, coarse nonmobile, nonshadowing, intraluminal echoes, and focal gallbladder wall irregularity.2 Ultrasound has limitations as it does not allow the appropriate evaluation of active bleeding or hemoperitoneum; furthermore the findings are operator dependent and can be compromised by patients’ body habitus.13

CT scan could help diagnose findings such as high attenuation material within the gall bladder lumen with fluid levels.14 In the arterial phase there may be active extravasation of the contrast into the gallbladder lumen. Also, CT scan could help with a diagnosis of hemoperitoneum. We believe CT is the best radiological test to identify the spectrum of findings present in hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Ultrasound has a 38.4% sensitivity and CT has a sensitivity of 69.2% in detecting hemorrhage in the gall bladder.5

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could be helpful if ultrasound and CT findings are inconclusive and in pregnant women to avoid radiation. MRI is the best imaging test for differentiating hemorrhage at the wall and lumen of the gallbladder, which is observed as high signal intensity of methemoglobin on T1-weighted imaging.13 Contrast MRI could help diagnose gangrenous cholecystitis with gall bladder perforation.15 Nevertheless, it is a difficult diagnosis to make radiologically7 and in our study just one case was diagnosed pre-operatively on CT scan.

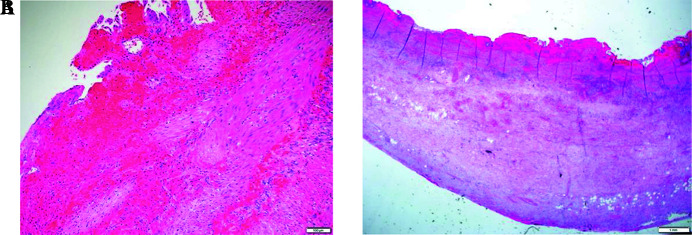

Histopathology of HC shows evidence of hemorrhage and inflammatory changes of the gall bladder, sometimes with signs of chronic of obstruction (see Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Photomicrograph of high magnification showing mucosal hemorrhage, widespread hemorrhage. (B) Photomicrograph of medium magnification showing florid mucosal injury replaced by widespread hemorrhage.

The treatment for HC is cholecystectomy. Our study revealed that most of the patients required laparoscopic cholecystectomy with 11.4% of patients requiring conversion to open surgery. Surgery was performed safely with no mortality in our series. In previous case studies, most patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy,16,17 others had open cholecystectomy2,5,11,12 or cholecystostomy, and a minority were managed nonoperatively6. Two patients required embolization of the cystic artery followed by open cholecystectomy.9

The strategies for safe cholecystectomy in HC is similar to those for acute cholecystitis and involves careful dissection of the hepatocystic triangle to achieve the critical view of safety, liberal use of intraoperative cholangiography, intraoperative time-out prior to clipping of any tubular structures, and recognition and utilization of anatomical landmarks to guide surgery. The surgeon should also be aware of and employ bailout strategies when indicated, which include conversion to open surgery, subtotal cholecystectomy, fundus first cholecystectomy, or tube cholecystostomy.18

Hemorrhagic cholecystitis is a rare presentation and the majority of previous publications are case reports. A total of 39 reports with 42 patients presenting with HC from January 1, 1985 – December 31, 2021 with approximately 45.2% of the patients on anticoagulation, 44.8% not on anticoagulation, and 10% not reported.15 Calderón et al. report a case series (n = 11), in which 82% of patients were on anticoagulations.13 This is in contrast to our study in which only 5.7% patients were on anticoagulation. In the literature, 76.2% of patients underwent cholecystectomy; 23.8% had nonoperative management or percutaneous cholecystostomies.13 In our series, all patients were managed with a cholecystectomy and all were discharged home without significant morbidity or mortality. The main limitation of our study is the retrospective nature; however, HC is a rare presentation.

In conclusion, HC is a rare form of acute cholecystitis. Anticoagulation only accounts for a small number of these patients. Pre-operative diagnosis of HC is not often made. All patients who were treated with cholecystectomies made a full recovery with no complications. Our study suggests that HC is a histological diagnosis with no clinical consequences for the patients.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: none.

Disclosure: none.

Funding sources: none.

Informed consent: Dr. Mirwais Khan Hotak declares that written informed consent was obtained from the patient/s for publication of this study/report and any accompanying images.

Contributor Information

Mirwais Khan Hotak, Department of Surgery, Calvary and Canberra Hospital, Bruce, Australia..

Mitali Fadia, Department of Anatomical Pathology, Canberra Hospital, Garran, Australia..

Sivakumar Gananadha, ANU Medical School, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia..

References:

- 1.Agha RA, Fowler AJ, Rajmohan S, et al. Preferred reporting of case series in surgery; the PROCESS guidelines. Int J Surg. 2016;36:319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng ZQ, Pradhan S, Cheah K, Wijesuriya R. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis: a rare entity not to be forgotten. BMJ Case Report. 2018:bcr-2018-226469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reens D, Podgorski B. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis: a case of expedited diagnosis by point-of-care ultrasound in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2019;57(1):74–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah VR, Clegg JF. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1979;66(6):404–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khoury G, Nicolas G, Abou-Jaoude EA, et al. An intra-operatively diagnosed case of hemorrhagic cholecystitis in a 43-year-old patient: case report. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:1732–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandya R, O'Malley C. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis as a complication of anticoagulant therapy: role of CT in its diagnosis. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(6):652–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks N. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis: an unusual cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ Case Report. 2014;2014:bcr2013202437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seok DK, Ki SS, Wang JH, Moon ES, Lee TU. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis presenting as obstructive jaundice. Korean J Intern Med. 2013;28(3):384–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.López V, Alconchel F. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Radiology. 2018;289(2):316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leaning M. Surgical case report—acalculous hemorrhagic cholecystitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2021(3);rjab075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Zhang C, Huang H, Wang J, Zhang Y, Hu Q. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis with rare imaging presentation: a case report and a lesson learned from neglected medication history of NSAIDs. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinnear N, Hennessey DB, Thomas R. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis in a newly anticoagulated patient. BMJ Case Report. 2017:bcr-2016-214617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calderón JZR, Chamorro EM, Sanz LI, Merino JCA, Nacenta SB. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis: ultrasound and CT imaging findings—a retrospective case review series. American Society of Emergency Radiology. 2021;28(3):613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revzin MV, Scoutt L, Smitaman E, Israel GM. The gallbladder: uncommon gallbladder conditions and unusual presentations of the common gallbladder pathological processes. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(2):385–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe Y, Nagayama M, Okumura A, et al. MR imaging of acute biliary disorders. Radiographics. 2007;27(2):477–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarazi M, Tomalieh FT, Sweeney A, Sumner D, Abdulaal Y. Literature review and case series of hemorrhagic cholecystitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2019(1):rjy360.2019rjy360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasegawa T, Sakuma T, Kinoshita H, et al. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis under anticoagulation. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta V, Jain G. Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy: adoption of universal culture of safety in cholecystectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;11(2):62–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]