Abstract

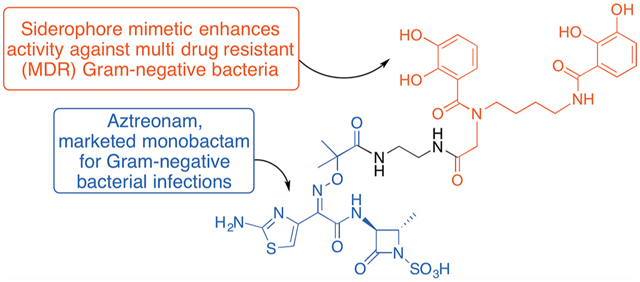

Monocyclic β-lactams with antibiotic activity were first synthesized more than 40 years ago. Extensive early structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies, especially in the 1980s, emphasized the need for heteroatom activation of monocyclic β-lactams and led to studies of oxamazins, monobactams, monosulfactams, and monocarbams with various side chains and peripheral substitution that revealed potent activity against select strains of Gram-negative bacteria. Aztreonam, still the only clinically used monobactam, has notable activity against many Gram-negative bacteria but limited activity against some of the most problematic multidrug resistant (MDR) strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Herein, we report that extension of the side chain of aztreonam is tolerated and especially that coupling of the side chain free acid with a bis-catechol siderophore mimetic significantly improves activity against the MDR strains of Gram-negative bacteria that are of most significant concern.

Keywords: aztreonam, siderophore conjugate, sideromycin, MDR bacteria

Graphical Abstract

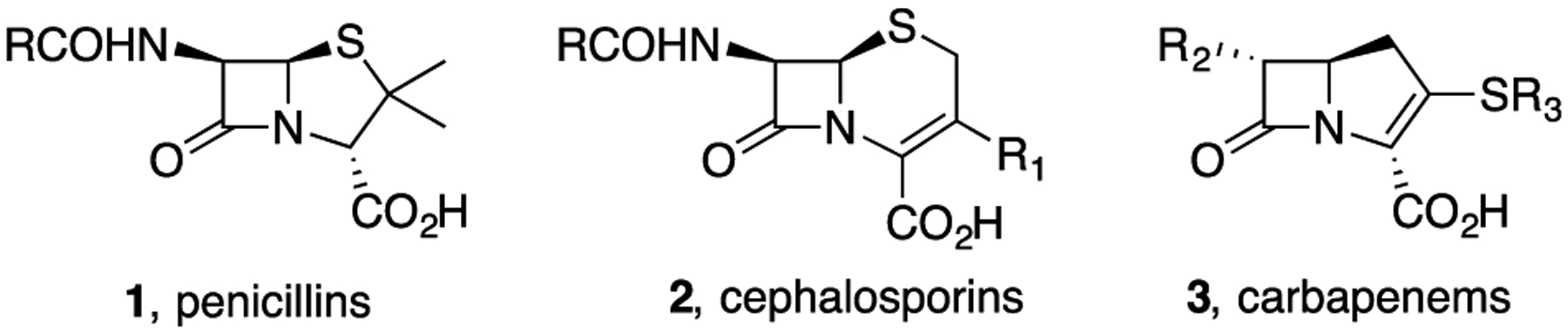

As the reactive warhead in classical penicillin, cephalosporin, carbapenem, and related antibiotics, the β-lactam core has been justifiably called the “enchanted ring”.1 These antibiotics positively influenced life as we know it and have contributed to a significant increase in life expectancy over the past century. As shown in Figure 1, most β-lactam antibiotics are fused bicyclic compounds with pendant functionality that is necessary for recognition, as they induce bacterial cell wall disruption. The bicyclic ring strain enhances the inherent reactivity of the β-lactam ring toward nucleophilic ring opening while interfering with bacterial cell wall synthesis. The extensive beneficial use and overuse of these important antibiotics has promoted the development of resistance to each successive generation of bicyclic β-lactams with a concomitant loss of efficacy primarily because of the extensive proliferation of β-lactamases that destroy the β-lactams before they reach their target.2 Health agencies have warned that over the next few decades the loss of antibiotic efficacy will result in millions of deaths with multitrillions of dollars in added economic burden.3 The WHO has identified several multidrug resistant strains of bacteria that are of particular concern, including β-lactamase producing strains of Acinetobacter baumanni and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.4 Although thousands of derivatives of bicyclic β-lactams have been prepared, most have relied on fermentation processes to provide the bicyclic framework for subsequent peripheral modification.

Figure 1.

Classical bicyclic β-lactam antibiotics.

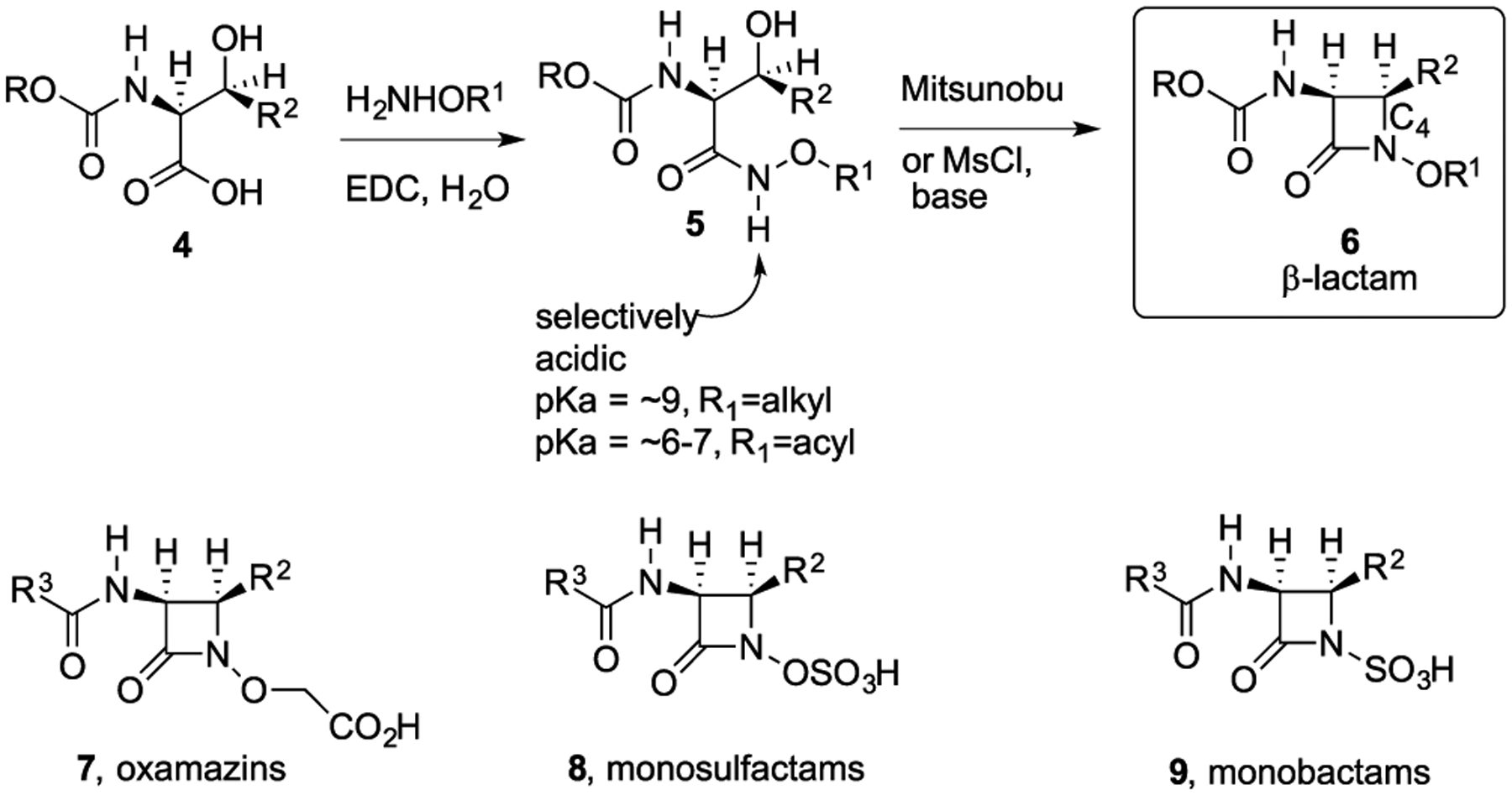

To date, no practical totally chemical syntheses of the penicillins or cephalosporins are available. In contrast, more than 40 years ago, our group developed a hydroxamate-mediated N–C4 biomimetic cyclization process (5 → 6, Scheme 1) that made it possible to efficiently synthesize the β-lactam core from β-hydroxy carboxylic acids (4) with complete control of the peripheral functionality and stereochemistry.5–7 The same process also introduced the concept of heteroatom activation rather than just bicyclic activation of the enchanted ring as manifested by the subsequent rapid disclosure of the oxamazins (7),8 monosulfactams (8), monobactams (9), monocarbams, and other moncyclic β-lactams.9 Development of this chemistry also coincided with the discovery of natural N-sulfated β-lactams (monobactams).

Scheme 1.

Hydroxamate-Mediated N–C4 Cyclization for Syntheses of Monocyclic β-Lactams

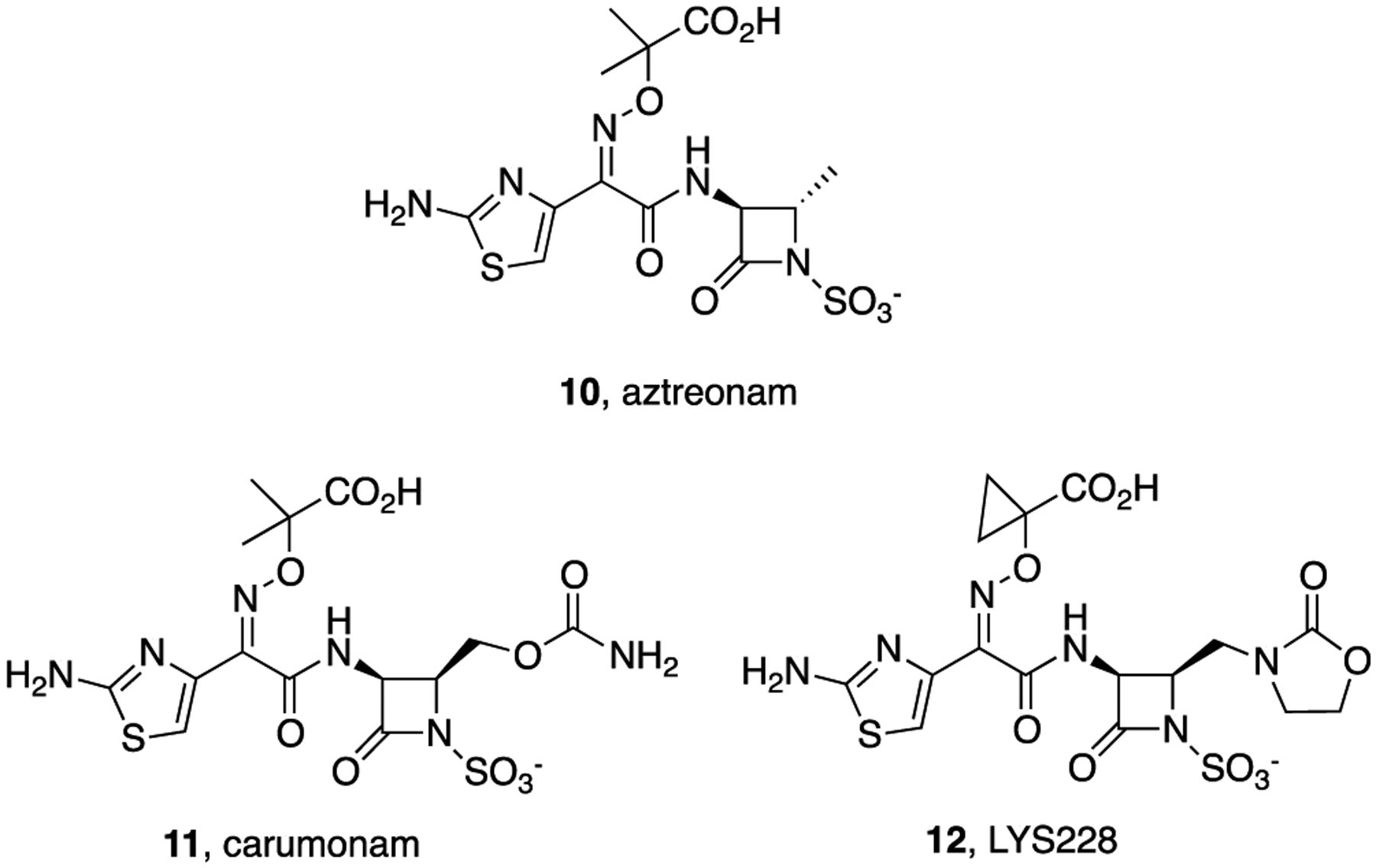

Although the natural monobactams were not highly active antibiotics,10,11 use of the N–C4 cyclization chemistry allowed syntheses of very active anti-Gram-negative bacteria monocyclic β-lactam antibiotics. Extensive structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies resulted in peripheral optimization12 that led to the first, and still only, marketed monobactam, aztreonam (10, Figure 2)13 although many other very active monobactams, including carumonam (11)14 and LYS228 (12),15 have been reported. Aztreonam is derived from the natural, readily available amino acid, l-threonine by modifications of the N–C4 cyclization chemistry.16,17 It was approved by the FDA in 1986 and is still used as an injectable antibiotic to treat infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria, including some that produce β-lactamases. However, aztreonam lacks efficacy against some of the MDR Gram-negative bacterial strains of greatest concern. Herein, we report that conjugates (27 and 30) of simple bis catechol siderophore mimetics and aztreonam (10) have enhanced and potent activity against Gram-negative bacteria, including those resistant to aztreonam itself.

Figure 2.

Aztreonam (10) and structures of related monobactams.

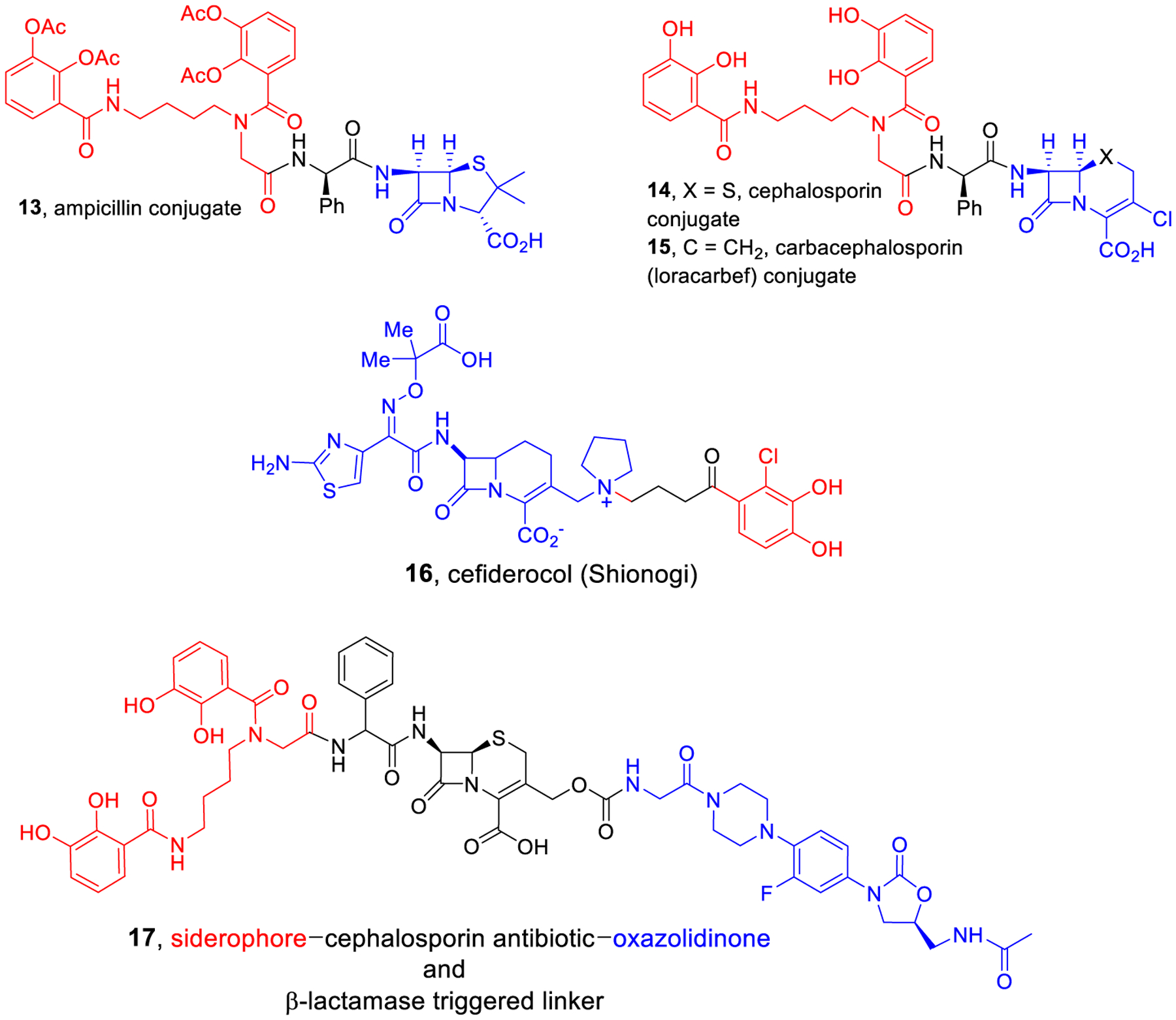

We and others have previously described the design, syntheses, and studies of siderophore–antibiotic conjugates that mimic natural sideromycins by utilizing essential iron sequestration processes to actively transport antibiotics into targeted pathogenic strains of bacteria.18,19 Most active synthetic sideromycins incorporate β-lactams as the antibiotic (“warhead”) component. In many cases, siderophore conjugates of penicillins (13, Figure 3)20 and cephalosporins (14, 15)21 have enhanced activity because of the active transport and circumvention of efflux, but some are still susceptible to deactivation by β-lactamases. However, cefiderocol (16),22 now also cleverly called FeTroja based on the iron-transport-mediated Trojan horse concept, is stable to most β-lactamases and has received FDA approval.23 Recently, we also demonstrated that β-lactamases can be exploited to release antibiotics from synthetic sideromycins. For example, a synthetic siderophore–cephalosporin–oxazolidinone conjugate (17) was potently active against cephalosporinase-producing strains of A. baumannii.24 By using the siderophore to actively transport the conjugate into the targeted bacteria, the β-lactamase destroyed the cephalosporin and released the normally Gram-positive antibiotic intracellularly and allowed it to kill Gram-negative bacteria. Although effective, this dual drug conjugate requires extensive synthesis.

Figure 3.

Representative known bis-catechol antibiotic conjugates.

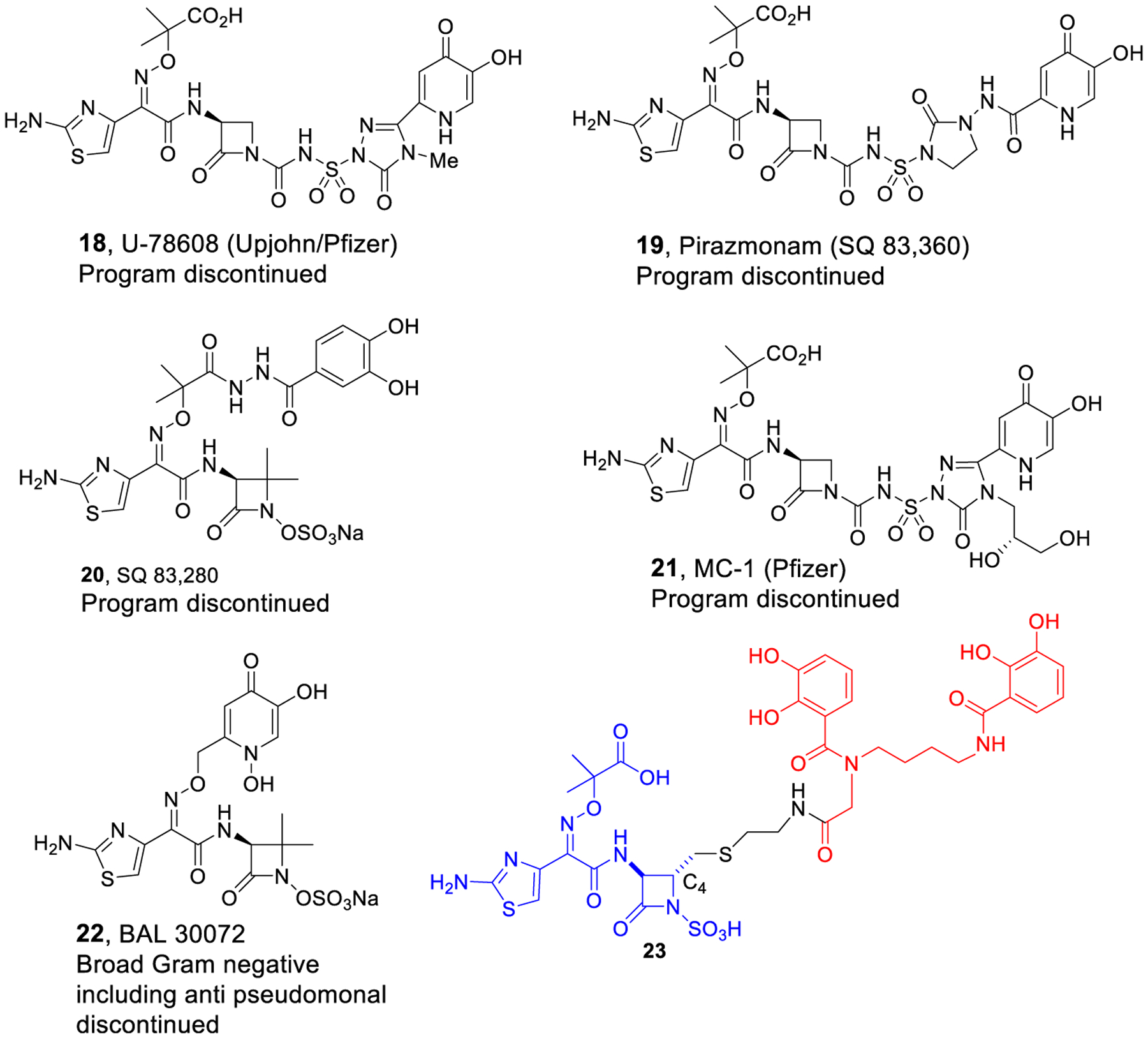

To avoid detrimental β-lactamase problems associated with conjugates of classical penicillins and cephalosporins, we prepared and studied siderophore conjugates of non-β-lactam antibiotics, including large complex compounds like daptomcyin and teicoplanin. In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated the effectiveness of the sideromycin approach to repurposing normally Gram-positive-only antibiotics to target Gram-negative bacteria.25 The reduced susceptibility of monobactams to β-lactamases also prompted us to further consider this class of small, structurally more simple compounds for siderophore conjugation. The primary concern was that more extensive modification of the monobactam periphery might negatively affect the previously established SAR.12 However, decades ago, iron-binding hydroxypyridone-substituted monocarbams such as U-78,608 (18)26 and pirazmonam (SQ-83,360, 19) as well as catechol SQ-83,280 (20)27 were reported to have impressive activity against Gram-negative bacteria even though they incorporated extensive modification beyond the original monobactam SAR suggestions (Figure 4). In 2011, the Pfizer group reported the synthesis and study of MC-1 (21), a hydroxypyridone-containing monocarbam with diol substitution that was hydrolytically stable and exhibited potent Gram-negative antibacterial activity.28 The monosulfactam BAL 30072 (22)29 and related compounds30 also replaced the usual aminothiazooxime carboxylic acid with a substituted hydroxypyridone. Although hydroxypyridones31 are not common natural siderophore iron binding ligands,32 they mimic catechols and their monocyclic β-lactam derivatives utilized siderophore transport to promote activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Unfortunately, none of these compounds were used clinically. However, their activity revealed that more extensive peripheral modification of the monocyclic β-lactam core was tolerated. As a further indication of acceptability of monobactam exterior modification, we also synthesized a C4-substituted monobactam with a bis-catechol siderophore mimetic. This conjugate (23)33 was extremely active against problematic Gram-negative bacteria, including carbapenemase and cephalosporinase producing strains of P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii, whereas aztreonam was not active (Table 1). Although such C4-substituted monobactams have tremendous potential, syntheses are lengthy because the corresponding β-hydroxy-α-amino acid precursors (4, with functionalized R2) are not readily available and require alternative syntheses.

Figure 4.

Monocarbams, monosulfactam, and monobactam conjugates.

Table 1.

Results of Duplicate In Vitro Antibacterial Assays of New Compounds 27, 30, and 32 and Comparison to Aztreonam (10) and Bis-Catechol Monobactam Derivative 23

| MIC values in μM using iron-deficient and (iron replete) MH media for different strains | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | 30 | 32 | 10 | 23 c | |

| S. aureus SG511 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| A. baumannii ATCC 17961 | 0.4 (4.5) | 0.4 (25) | >25 | >25 (>25) | 0.2 |

| A. baumannii ATCC BAA 1797 | 0.8 (12.5) | 0.4(>25) | >25 | >25 (>25) | 0.4 |

| A. baumannii ATCC 17978 | 0.2 | 0.2 | >25 | 25 | NT |

| A. baumannii ATCC 17978 pNT320a | 0.4 | 0.4 | >25 | >25 | 0.4 |

| A. baumannii ATCC 17978 pNT165b | 1.6 | 1.6 | >25 | >25 | 0.4 |

| B. dolosaAU0018 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 |

| P. aeruginosa 01 | 0.4 (1.2) | 0.4 (8) | 25 | 6 (6) | 0.4 |

| P. aeruginosa KW799/wt | 0.05 (0.6) | 0.05 (0.6) | 12.5 | 6 (3) | 0.4 |

| P. aeruginosa ARC 3502 | 1.6 (3) | 3 (25) | >25 | >25 (>25) | >25 |

| P. aeruginosa ISR14–003 | 0.2 (1.7) | 0.2 (0.4) | >25 | >25 (>25) | 1.6 |

| P. aeruginosa ISR14–004 | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.3) | 25 | 6 (3) | 6 |

| E. coli DC0 | 0.025 (0.1) | <0.0125 (0.2) | 0.4 | 0.4 (0.1) | <0.025 |

| E. aerogenes X816 | 0.1 (0.8) | 0.1 (1) | 0.8 | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.075 |

| P. mirabilis X235 | <0.013 (0.15) | <0.01 (0.025) | 0.05 | <0.013 (<0.013) | <0.025 |

| C. freundii ATCC 19063 | 0.025 | <0.0125 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.05 |

| K. pneumoniae X68 | 0.05 (0.6) | 0.05 (1.6) | 0.8 | 0.2 (0.2) | NTd |

Cephalosporinase-producing strain.

Carbapenemase-producing strain.

Literature value.33

NT = not tested.

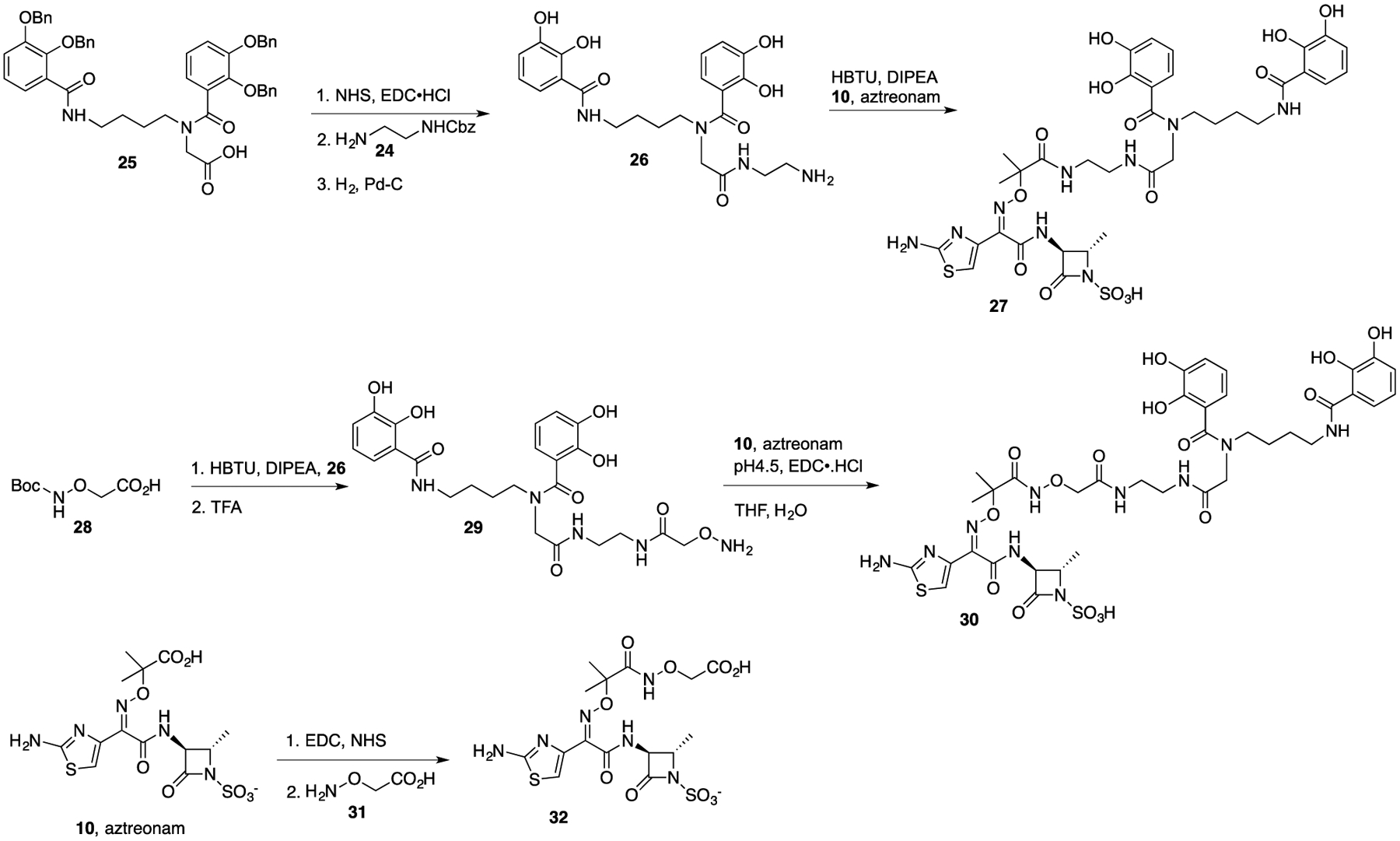

To address the ongoing need for extension of the antibiotic activity of monobactams against MDR Gram-negative bacteria, we decided to synthesize conjugates (27 and 30) in which a bis-catechol siderophore is directly attached to the side chain aminothiazoloxime (ATMO) carboxylic acid of commercially available aztreonam (10). As indicated above, related bis-catechol antibiotic conjugates (13–15) are remarkably active, indicating that the bis-catechol facilitates uptake by usually MDR Gram-negative bacteria. Although we were concerned that by coupling the side chain carboxylic acid to a terminal amine of a bis-catechol derivative to give 27 might reduce antibiotic activity, as the resulting amide would no longer be ionizable like the free acid of aztreonam itself, we were encouraged that SQ 83,280 (20) and BAL 30072 (22), without free carboxylic acids, retained potent in vitro activity. Still, we also thought that it would be of interest to incorporate an acidic moiety to mimic the carboxylic acid. Thus, we also synthesized the hydroxamic acid (32) derived from aminooxyacetic acid and the corresponding bis-catechol conjugate (30). Although hydroxamic acids (pKa ~8.5–9.5) are not as acidic as carboxylic acids, we wanted to compare the activity of derivative 32 to aztreonam and that of the corresponding amide (27) and hydroxamate (30) conjugates. A very attractive aspect of the proposed new conjugates was their straightforward syntheses, which required only coupling of readily available derivatives (26 and 29) of siderophore mimetics to commercially available aztreonam (10).

The syntheses are depicted in Scheme 2. The reaction of ethane 1,2-diamine with CbzCl gave mono-Cbz protected diamine 24. Formation of the active ester of tetrabenzyl bis-catechol (25) provided the siderophore derivative (26) with an amine suitable for coupling with aztreonam (10) to give conjugate 27. Alternatively, prior coupling of siderophore amine 26 with Boc-protected aminooxyacetic acid (28) gave hydroxylamine 29. Treatment of an aqueous solution of hydroxylamine 29 and aztreonam (10) with EDC at pH 4.5 in aqueous THF provided the final conjugate, 30, with a hydroxamate linkage. The control aminooxyacetic acid derivative 32 was prepared by EDC/NHS activation of aztreonam followed by reaction with aminooxyacetic acid (31).

Scheme 2.

Syntheses of Aztreonam Conjugates (27 and 30) and Analog 32

The results of antibacterial assays of the three new aztreonam derivatives (27, 30, and 32), aztreonam (10), and earlier data of conjugate 2333 are shown in Table 1. The assays were performed using iron-deficient media appropriate for screening siderophore conjugates as described previously.34 Representative assays were also performed under iron-replete (added FeCl3) conditions in the same media to explore the effect of non-siderophore-bound iron. As expected, under iron-restricted conditions that best mimic the situation during infections, the new siderophore conjugates (27 and 30) were most active with superb MIC values. Although their activity was significantly reduced under iron-replete conditions and end points less distinct, the conjugates still had activity comparable to or better than aztreonam, which was not affected by the presence or absence of iron in the media. Aminooxyacetic acid derivative 32 also displayed activity similar to that of aztreonam (10) itself. As expected, none of the compounds were active against the Gram-positive S. aureus. However, the conjugates (27 and 30) were notably active against Gram-negative bacteria that are resistant to aztreonam. Of special interest is the significant inhibitory activity against problematic strains of A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa, including cephalosporinase-producing P. aeruginosa and carbapenemase-producing A. baumannii (A. baumannii TCC 17978 pNT320 and ATCC 17978 pNT165), which are on the World Health Organization (WHO) list of MDR pathogens of greatest concern. The activity of the new conjugates (27 and 30) was also comparable to or better than that of the previously described more synthetically complex bis-catechol conjugate 23.33

The remarkable activity of conjugates 27 and 30 prompted further studies, including hydrolytic stability and mammalian cytotoxicity. Interestingly, although aztreonam (10) was completely stable in pH 7 buffer at room temperature for 24 h as monitored by LC/MS, only about 33% of 27 and 25% of 30 remained under the buffered conditions. In each case, a single product was produced with a mass corresponding to the original MW + 18, suggesting hydrolytic opening of the monobactam ring. The MW + 18 reaction product from conjugate 27 was isolated. Although the isolate contained a trace amount (~1% by LC/MS analysis) of the original conjugate (27), it was screened for activity against some of the same strains of Gram-negative bacteria, shown in Table 1. As shown in Table S1, the MW + 18 compound was significantly less active and in most cases was devoid of activity, consistent with hydrolysis of the β-lactam. These results suggest that the conjugates are rapidly assimilated by the targeted bacteria by their active iron-transport processes to induce inhibition of bacterial growth.

Because conjugates 27 and 30 contain catechol ligands, we were concerned about potential mammalian cytotoxicity. We were able to utilize the suite of nonclinical and preclinical services for in vitro assessment offered by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to determine cytotoxicity in human primary hepatocytes in the presence of compounds 27 and 30. Gratifyingly, neither conjugate demonstrated any significant toxic effects on human hepatocyte viability up to 100 μM, the top concentration evaluated (data are in the Supporting Information).

CONCLUSION

These studies demonstrate that direct coupling of siderophore-like compounds to the free carboxylic acid of the commercially available monobactam, aztreonam (10), provides rapid access to noncytotoxic conjugates with significantly enhanced antibacterial activity, including against MDR strains. Although there has been skepticism about the clinical potential of siderophore–antibiotic conjugates (sideromycins),35 the potential of this so-called Trojan horse approach to enhancing activity and even repurposing36 normally Gram-positive antibiotics and other agents merits continued attention. The recent FDA approval of cefiderocol (FeTroja, 16) emphasizes the value of this approach. It should also be recalled that natural sideromycins, including albomycin,37 were successfully used in the clinic to treat antibiotic-resistant infections even in the 1950s.38,39 Appropriately designed synthetic sideromycins have the potential to allow much needed development of both broad spectrum and narrowly targeted antibiotics. Additional studies on the spectrum of activity, in vivo efficacy and pharmaceutical potential of conjugates 27 and 30 are merited and are under consideration.

METHODS

General Methods.

All solvents and reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. Silica gel (230–400 mesh) was purchased from Silicycle, Quebec City, Canada. All compounds are >98% pure by HPLC analysis. All compounds were analyzed for purity by HPLC and characterized by 1H and 13C NMR using a Bruker 500 MHz NMR spectrometer. The mass spectra values are reported as m/z, and HRMS analyses were carried out with a Bruker MicroOTOF-Q II, electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer. The liquid chromatography mass spectrum (LC/MS) analyses were carried out on a Waters ZQ instrument consisting of chromatography module Alliance HT, photodiode array detector 2996, and mass spectrometer Micromass ZQ, using a 3 × 50 mm Pro C18 YMC reverse phase column. Mobile phases: 10 mM ammonium acetate in HPLC grade water (A) and HPLC grade acetonitrile (B). A gradient was formed from 5 to 80% of B in 10 min at 0.7 mL/min. The MS electrospray source operated at capillary voltage 3.5 kV and a desolvation temperature of 300 °C.

Benzyl (2-Aminoethyl)carbamate (24).

A solution of benzyl chloroformate (1.3 mL, 9 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (25 mL) was added over 1.5 h to a solution of ethylenediamine (6 mL, 90 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (90 mL) at 0 °C under an argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h, and then washed with brine (30 mL × 3 times). The CH2Cl2 layer was dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. Compound 24 was obtained as a white solid that was used directly for the next step without purification.

N-(2-((2-Aminoethyl)amino)-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-(2,3-dihydroxybenzamido)butyl)-2,3-dihydroxybenzamide (26).

To a solution of compound 25 (1 mmol, 779 mg) in 10 mL of dry DMF was added N-hydroxysuccinimide (1.5 mmol, 172 mg) and EDC·HCl (2 mmol, 382 mg). The mixture was stirred at room temperature and monitored by TLC. When the starting material 25 was completely consumed, compound 24 (1.2 mmol, 233 mg) was added to the reaction mixture, stirred for several hours, and monitored by LC/MS. When the reaction was completed, the solution was diluted with H2O and extracted with EtOAc (30 mL × 3 times). The EtOAc layers were combined and dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure evaporation. The residue was purified on silica gel column chromatography eluting with CH2Cl2 and 2-propanol (100:3) to give benzyl (2-(2-(2,3-bis(benzyloxy)-N-(4-(2,3-bis(benzyloxy)benzamido)butyl)benzamido)-acetami do)ethyl)carbamate as a colorless oil in 79% yield (753 mg, 0.79 mmol). 1H NMR (MeOD, 500 MHz): δ 1.03–1.04 (m, 5H), 3.61–4.21 (m, 2H), 2.95–3.15 (m, 7H), 4.82–4.87 (m, 1H), 4.94 (s, 1H), 5.00–5.02 (m, 3H), 5.05 (d, 1H, J = 5.0 Hz), 5.07 (d, 1H, J = 5.0 Hz), 5.10–5.15 (m, 3H), 7.04–7.46 (m, 31H).

To a solution of benzyl (2-(2-(2,3-bis(benzyloxy)-N-(4-(2,3-bis(benzyloxy)benzamido)butyl) benzamido)acetamido)-ethyl)carbamate (0.5 mmol, 477 mg) in 15 mL of MeOH under an argon atmosphere was added 10% Pd/C (47 mg, 10% wt. of the oil). The reaction flask was degassed and then refilled with H2 by a balloon. After the solution was stirred overnight, the reaction was completed, so it was filtered and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to give compound 26 as a light-purple solid in 76% yield that was used directly for the next step without purification.

(2S,3S)-3-((Z)-18-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl)-7-(2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)-1-(2,3-dihydroxyphenyl)-15,15-dimethyl-1,9,14-trioxo-16-oxa-2,7,10,13,17-pentaazanonadec-17-en-19-amido)-2-methyl-4-oxoazetidine-1-sulfonic acid (27).

To the solution of aztreonam (10, 0.5 mmol, 217 mg) in 10 mL of DMF was added HBTU (0.76 mmol, 288 mg) and DIPEA (2 mmol, 348 μL). The mixture was stirred for 10 min at room temperature. Compound 26 (0.5 mmol, 230 mg) in 2 mL of DMF was then added to the above reaction mixture. The solution was stirred overnight and monitored by LC/MS. When the reaction was completed, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure evaporation and the residue was purified by prep-HPLC to give compound 27 as a white solid in 18.3% yield (80 mg, 0.09 mmol). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): δ 1.11–1.42 (m, 12H), 1.54 (brs, 1H), 3.03–3.29 (m, 8H), 3.66–3.72 (m, 2H), 3.95–4.02 (m, 1H), 4.50 (s, 1H), 6.49–6.65 (m, 3H), 6.72–6.69 (m, 2H), 6.87 (d, 1H, J = 5 Hz), 6.96 (s, 1H), 7.07 (s, 1H), 7.17–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.29–7.37 (m, 3H), 7.88 (t, 1H, J = 5 Hz), 8.66–8.78 (m, 1H), 9.09–9.13 (m, 1H), 9.32–9.35 (m, 1H), 9.41–9.46 (m, 1H), 12.80–12.90 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): δ 18.67, 24.60, 24.96, 26.03, 26.47, 38.79, 39.12, 48.11, 49.45, 51.45, 57.71, 60.94, 83.61, 111.20, 115.52, 116.22, 116.66, 117.74, 118.19, 118.53, 119.42, 119.96, 120.19, 125.08, 141.84, 142.94, 145.90, 146.85, 150.40, 150.99, 162.85, 163.30, 169.47, 169.92, 170.37, 174.36. HRMS calcd for C35H44N9O14S2 (M +H+) 878.2444; found 878.2429.

2-(((tert-Butoxycarbonyl)amino)oxy)acetic Acid (28).

A round-bottom flask was charged with 2-(aminooxy)acetic acid hemihydrochloride (31, 2 mmol, 220 mg) in 15 mL of dry CH2Cl2. The solution was cooled to 0 °C, and Et3N (6 mmol, 424 μL) was added. To the mixture was added a solution of (Boc)2O (3 mmol, 1.3 g) in 10 mL of CH2Cl2. The reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min, then warmed up to room temperature. When the reaction was completed, the solution was washed with water. The aqueous portion was extracted with 20 mL of EtOAc and this EtOAc was discarded. Then the pH value of the aqueous portion was adjusted to 3.5 with 1 N HCl, and extracted with EtOAc (30 mL × 3 times). The EtOAc layers were combined and concentrated under reduced pressure to give compound 28 as a white solid, which was used directly without purification.

N-(2-((2-(2-(Aminooxy)acetamido)ethyl)amino)-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-(2,3-dihydroxybenzamido) butyl)-2,3-dihydroxybenzamide (29).

To a solution of 28 (0.98 mmol, 187 mg) in DMF (5 mL) was added HBTU (1.34 mmol, 505 mg) and DIPEA (3.56 mmol, 656 μL), and the mixture was stirred 10 min at room temperature. Compound 26 (409 mg, 0.89 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) was then added to the above solution and the reaction was continued overnight. When the reaction was completed, the solvent was removed by reduced pressure evaporation, and the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography eluting with CH2Cl2 and MeOH (20:1) to give tert-butyl ((7-(2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)-1-(2,3-dihydroxyphenyl)-1,9,14-trioxo-2,7,10,13-tetraazapentadecan-15-yl)oxy)-carbamate as a light yellow solid in 45% yield (170 mg, 0.27 mmol). 1H NMR (MeOD, 500 MHz): δ 1.41–1.50 (m, 11H), 1.57–1.60 (m, 1H), 1.73 (brs, 1H), 3.24 (t, 2H, J = 5 Hz), 3.35–3.61 (m, 6H), 3.98–4.25 (m, 4H), 6.69–6.72 (m, 3H), 6.83–6.85 (m, 1H), 6.91 (dd, 1H, J1 = 5 Hz, J2 = 10 Hz), 7.16–7.22 (m, 1H).

tert-Butyl

((7-(2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)-1-(2,3-dihydroxyphenyl)-1,9,14-trioxo-2,7,10,13-tetraazapentadecan-15-yl)oxy)-carbamate (80 mg, 0.13 mmol) was dissolved in 15 mL of dry CH2Cl2 followed by the addition of 1 mL of TFA. The mixture was stirred at room temperature and monitored by LC/MS. When the reaction was completed, the reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure evaporation to give compound 29, which was used directly for the next step without further purification.

(2S,3S)-3-((Z)-22-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl)-7-(2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)-1-(2,3-dihydroxyphenyl)-19,19-dimethyl-1,9,14,18-tetraoxo-16,20-dioxa-2,7,10,13,17,21-hexaazatricos-21-en-23-amido)-2-methyl-4-oxoazetidine-1-sulfonic Acid (30).

Compound 29 (67 mg, 0.12 mmol) and aztreonam (10, 156 mg, 0.36 mmol) were dissolved in H2O/THF (2 mL/2 mL) to give a solution. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 4.5 by adding NaOH (1N). EDC·HCl (46 mg, 0.24 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of H2O and then slowly added to the above mixture while keeping the pH at 4.5 by adding HCl (1N). When the pH did not change during EDC·HCl addition, the reaction was completed and confirmed by LC/MS. The resulting solution was purified by prep-HPLC directly without workup. Compound 30 was obtained as a white solid in 35% yield (40 mg, 0.04 mmol). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): δ 1.30 (brs, 1H), 1.36 (brs, 6H), 1.40–1.43 (m, 4H), 1.55 (brs, 2H), 3.08 (brs, 4H), 3.17 (brs, 4H), 3.66–3.70 (m, 1H), 3.73 (s, 1H), 4.03 (s, 1H), 4.22–4.25 (m, 2H), 4.49 (dd, 1H, J1 = 5 Hz, J2 = 10 Hz), 6.50–6.64 (m, 3H), 6.70–6.77 (m, 1H), 6.80 (s, 1H), 6.87 (d, 1H, J = 5 Hz), 6.96 (s, 1H), 7.06 (s, 1H), 7.16 (s, 1H), 7.20–7.29 (m, 1H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 7.92 (s, 1H), 8.23 (d, 1H, J = 20 Hz), 8.66–8.78 (m, 1H), 9.09 (d, 1H, J = 20 Hz), 9.23 (d, 1H, J = 10 Hz), 9.48 (d, 1H, J = 10 Hz), 11.00 (s, 1H), 12,79–12.89 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz): δ 17.13, 23.33, 23.52, 25.68, 26.14, 26.38, 28.34, 38.76, 48.49, 49.92, 58.24, 61.42, 75.13, 83.75, 111.89, 115.52, 116.33, 117.50, 117.82, 118.38, 120.04, 120.29, 123.35, 141.08, 141.53, 145.41, 145.68, 146.11, 149.13, 149.99, 163.73, 163.88, 169.97, 170.35, 170.48, 171.77, 172.86. HRMS calcd for C37H47N10O16S2 (M+H+) 951.2607; found 951.2611.

(Z)-2-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl)-5,5-dimethyl-1-(((2S,3S)-2-methyl-4-oxo-1-sulfoazetidin-3-yl)amino)-1,6-dioxo-4,8-dioxa-3,7-diazadec-2-en-10-oic Acid DIPEA Salt (32).

To a solution of aztreonam (10, 0.3 mmol, 130 mg) in 4 mL of DMF was added N-hydroxysuccinimide (1.2 mmol, 138 mg) and EDC·HCl (1.5 mmol, 287 mg). The reaction was stirred at room temperature and monitored by LC/MS. When the aztreonam was completely converted to the NHS active ester as indicated by the LC/MS, 2-(aminooxy)acetic acid hemihydrochloride (31, 3 mmol, 327 mg) was added to the reaction solution, followed by adding DIPEA (6 mmol, 1.1 mL). The reaction was continued with stirring at room temperature for several hours and was monitored by LC/MS. When the reaction was completed, the solution was concentrated by reduced pressure evaporation, and the residue was purified by prep-HPLC. Compound 32 was obtained as a colorless oil in 75% yield (115 mg, 0.23 mmol).1H NMR (MeOD, 500 MHz): δ 1.34–1.37 (m, 15H), 1.53 (s, 3H), 1.54 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 3H), 3.19 (q, 2H, J = 5 Hz), 3.69–3.74 (m, 2H), 4.13–4.15 (m, 1H), 4.22 (d, 2H, J = 5 Hz), 4.55 (d, 1H, J = 5 Hz), 6.95 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (MeOD, 500 MHz): δ 12.00, 16.68, 17.10, 22.58, 23.39, 23.50, 42.52, 54.51, 57.99, 61.60, 74.11, 83.53, 111.54, 141.82, 150.34, 163.74, 164.06, 171.96, 174.77. HRMS calcd for C15H20N6NaO10S2 (M+Na+) 531.0575; found 531.0599.

Antibacterial Assays.

MIC analyses (Table 1) were performed using iron-depleted media as described previously34 and separately under iron-replete (added iron) conditions. More details, including descriptions of the bacteria strains, are given in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the NIH (R37AI054193) and the University of Notre Dame. For cytotoxicity assays, the University of Notre Dame has utilized the suite of nonclinical and preclinical services for in vitro assessment offered by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Contract HHSN272201800007I/75N93021F00001, with Eurofins Pan-labs, Inc.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00458.

NMR spectra, descriptions of bacteria, assays in iron-replete media, MIC values in μg/mL, hydrolytic stability, and cytotoxicity assays (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00458

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Rui Liu, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Patricia A. Miller, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

Marvin J. Miller, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sheehan JC The Enchanted Ring: The Untold Story of Penicillin; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bush K; Bradford PA β-Lactamases: historical perspectives. In Enzyme-Mediated Resistance to Antibiotics: Mechanisms, Dissemination, And Prospects for Inhibition; Bonomo RA; Tolmasky ME, Eds.; ASM Press; Washington, DC, 2007; pp 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- (3).O’Neill J Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: London, 2016; pp 1–84. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2019-10-11-AMR-Full-Paper.pdf (accessed 2021–10-01). [Google Scholar]

- (4).2020 Antibacterial Agents in Clinical and Preclinical Development: An Overview and Analysis; World Health Organization, Geneva, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240021303 (accessed 2021–06-14). [Google Scholar]

- (5).Mattingly PG; Kerwin JF Jr, Miller MJ A Facile Synthesis of Substituted N-Hydroxy-2-Azetidinones. A Biogenic Type β-Lactam Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101, 3983–3985. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Miller MJ; Mattingly PG; Morrison MA; Kerwin JF Synthesis of β-Lactams from Substituted Hydroxamic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 7026–7032. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Miller MJ The Hydroxamate Approach to the Synthesis of β-Lactam Antibiotics. Acc. Chem. Res 1986, 19, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Woulfe SR; Miller MJ Synthesis and Biological Activity of [(3(S)-Acylamino-2-Oxo-1-Azetidinyl)oxy] Acetic Acids. A New Class of Heteroatom Activated ß-Lactam Antibiotics. J. Med. Chem 1985, 28, 1447–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cimarusti CM; Sykes RB Monocyclic β-Lactam Antibiotics. Med. Res. Rev 1984, 4, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Sykes RB; Cimarusti CM; Bonner DP; Bush K; Floyd DM; Georgopapadakou NH; Koster WH; Liu WC; Parker WL; Principe PA; Rathnum ML; Slusarchyk WA; Trejo WH; Wells JS Monocyclic β-Lactam Antibiotics Produced by Bacteria. Nature 1981, 291, 489–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Imada A; Kitano K; Kintaka K; Muroi M; Asai M Sulfazecin and Isosulfazecin, Novel β-Lactam Antibiotics of Bacterial Origin. Nature 1981, 289, 590–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Decuyper L; Jukic M; Sosic I; Zula A; D’hooghe MD; Gobec S Antibacterial and β-Lactamase Inhibitory Activity of Monocyclic β-Lactams. Med. Res. Rev 2018, 38, 426–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sykes RB; Bonner DP; Bush K; Georgopapadakou NH Azthreonam (SQ 26,776), a Synthetic Monobactam Specifically Active Against Aerobic Gram-negative Bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1982, 21, 85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).McNulty CA; Garden GM; Ashby J; Wise R Pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of carumonam, a new synthetic monobactam. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 1985, 28, 425–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Blais J; Lopez S; Li C; Ruzin A; Ranjitkar S; Dean CR; Leeds JA; Casarez A; Simmons RL; Reck F In Vitro Activity of LYS228, a Novel Monobactam Antibiotic, against Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2018, 62, e00552–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Slusarchyk WA; Dejneka T; Gordon EM; Weaver ER; Koster WH Monobactams: Ring Activating N-1 Substituents in Monocyclic β-Lactam Antibiotics. Heterocycles 1984, 21, 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Floyd DM; Fritz W; Cimarusti CM Monobactams. Stereospecific Synthesis of (S)-3-amino-2-oxoazetidine-1-sulfonic Acids. J. Org. Chem 1982, 47, 176–178. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wencewicz TA; Miller MJ Sideromycins as Pathogen-Targeted Antibiotics. In Antibacterials; Fisher JF, Mobashery S, Miller MJ, Eds.; Springer International; Publishing. 2018; Vol. II, pp 151–183. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Miller MJ; Liu R Design and Syntheses of New Antibiotics Inspired by Nature’s Quest for Iron in an Oxidative Climate. Acc. Chem. Res 2021, 54, 1646–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Möllmann U; Heinisch L; Bauernfeind A; Kohler T; Ankel-Fuchs D Siderophores as Drug Delivery Agents: Application of the “Trojan Horse” Strategy. BioMetals 2009, 22, 615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lin Y-M; Ghosh M; Miller P; Möllmann U; Miller MJ Synthetic sideromycins (skepticism and optimizm): selective generation of either broad or narrow spectrum Gram-negative antibiotics. BioMetals 2019, 32, 425–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Aoki T; Yoshizawa H; Yamawaki K; Yamawaki K; Yokoo K; Sato J; Hisakawa S; Hasegawa Y; Kusano H; Sano M; et al. Cefiderocol (S-649266), A new siderophore cephalosporin exhibiting potent activities against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative pathogens including multi-drug resistant bacteria: Structure activity relationship. Europ. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 155, 847–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).FDA approves new antibacterial drug to treat complicated urinary tract infections as part of ongoing efforts to address antimicrobial resistance. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-antibacterial-drug-treat-complicated-urinary-tract-infections-part-ongoing-efforts (accessed 2021-10-01).

- (24).Liu R; Miller PA; Vakulenko SB; Stewart NK; Boggess WC; Miller MJ A Synthetic Dual Drug Sideromycin Induces Gram-Negative Bacteria to Commit Suicide with a Gram-Positive Antibiotic. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 3845–3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ghosh M; Miller PA; Möllmann U; Claypool WD; Schroeder VA; Wolter WR; Suckow M; Yu H; Li S; Huang W; Zajicek J; Miller MJ Targeted Antibiotic Delivery: Selective Siderophore Conjugation with Daptomycin Confers Potent Activity Against Multi-Drug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Both in vitro and in vivo. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 4577–4583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Barbachyn MR; Touminen TC Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationships of Monocarbams Leading to U-78608. J. Antibiot 1990, 43, 1199–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Sykes RB; Koster WH; Bonner DP The New Monobactams: Chemistry and Biology. J. Clin. Pharmacol 1988, 28, 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Flanagan ME; Brickner SJ; Lall M; Casavant J; Deschenes L; Finegan SM; George DM; Granskog K; Hardink JR; Huband MD; Hoang T; Lamb L; Marra A; Mitton-Fry M; Mueller JP; Mullins LM; Noe MC; O’Donnell JP; Pattavina D; Penzien JB; Schuff BP; Sun J; Whipple DA; Young J; Gootz TD Preparation, Gram-Negative Antibacterial Activity, and Hydrolytic Stability of Novel Siderophore-Conjugated Monocarbam Diols. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2011, 2, 385–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Page MGP; Dantier C; Desarbre E In Vitro Properties of BAL30072, a Novel Siderophore Sulfactam with Activity against Multiresistant Gram-Negative Bacilli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 2291–2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Tan L; Tao Y; Wang T; Zou F; Zhang S; Kou Q; Niu A; Chen Q; Chu W; Chen X; Wang H; Yang Y Discovery of Novel Pyridone-Conjugated Monosulfactams as Potent and Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics for Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 2669–2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Cilibrizzi A; Abbate V; Chen Y-U; Ma Y; Zhou T; Hider RC Hydroxypyridone Journey into Metal Chelation. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 7657–7701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hider RC; Kong X Chemistry and Biology of Siderophores. Nat. Prod. Rep 2010, 27, 637–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Carosso S; Liu R; Miller PA; Hecker SJ; Glinka T; Miller MJ Methodology for Monobactam Diversification: Synthesesand Studies of 4-Thiomethyl Substituted β-Lactams with Activity Against Gram-Negative Bacteria, Including Carbapenemase Producing Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 8933–8944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ghosh M; Miller PA; Möllmann U; Claypool WD; Schroeder VA; Wolter WR; Suckow M; Yu H; Li S; Huang W; Zajicek J; Miller MJ Targeted Antibiotic Delivery: Selective Siderophore Conjugation with Daptomycin Confers Potent Activity Against Multi-Drug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Both in vitro and in vivo,. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 4577–4583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lin Y-M; Ghosh M; Miller P; Möllmann U; Miller MJ Synthetic sideromycins (skepticism and optimizm): selective generation of either broad or narrow spectrum Gram-negative antibiotics. BioMetals 2019, 32, 425–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ghosh M; Miller PA; Miller MJ Antibiotic repurposing: bis-catechol- and mixed ligand (bis-catechol-mono-hydroxamate)-teicoplanin conjugates are active against multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antibiot 2020, 73, 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Vertesy L; Aretz W; Fehlhaber H-W; Kogler H Salmycin A-D, antibiotika aus Streptomyces violaceus, DSM 8286, mit siderophor-aminoglycosid-struktur. Helv. Chim. Acta 1995, 78, 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Gause GF Recent studies on albomycin, a new antibiotic. Br. J. Med 1955, 2, 1177–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Gamburg RL Use of albomycin in pneumonia in children. Pediatriia 1951, 5, 37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.