Abstract

Objective

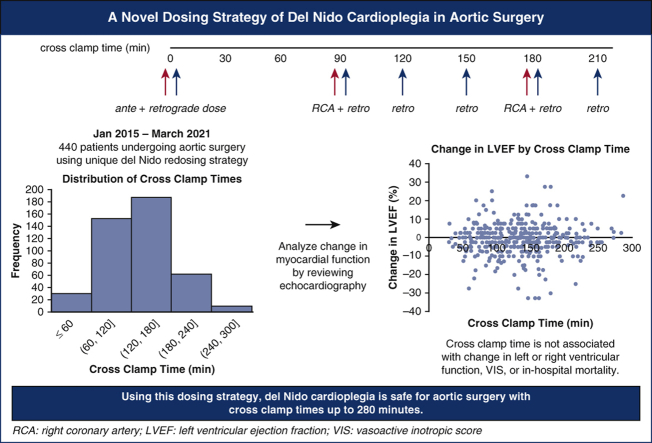

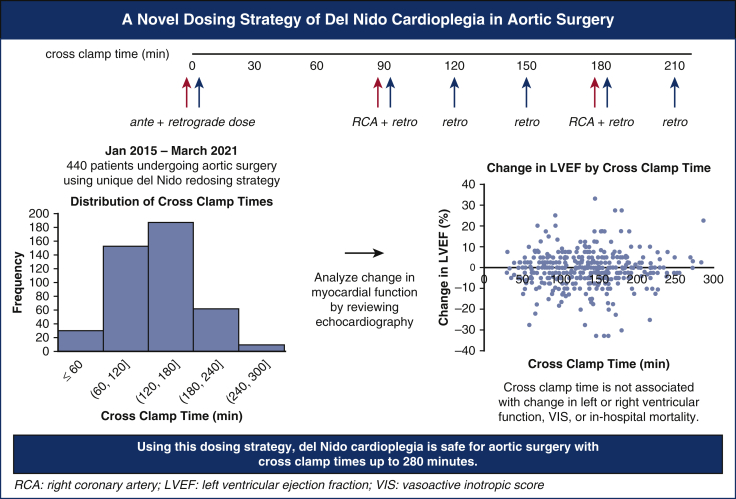

While del Nido (DN) cardioplegia is increasingly used in cardiac surgery, knowledge is limited in its safety profile for operations with prolonged crossclamp time (CCT). We have introduced a unique redosing strategy for aortic surgery: all operations use DN with a 1000-mL initiation dose (750 mL antegrade, 250 mL retrograde) composed of 1:4 blood:DN crystalloid. At 90 minutes CCT and every 30 minutes thereafter, a 250-mL dose was introduced retrograde in a 4:1 (“reverse”) ratio. Additionally, at 90 minutes CCT and every 90 minutes thereafter, a reverse ratio dose of approximately 100 to 400 mL was introduced via the right coronary artery. Here, we analyze the outcomes of our unique redosing strategy used.

Methods

In total, 440 patients underwent aortic surgery between January 2015 and March 2021 under a single surgeon and received DN. Our primary end points were change in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and right ventricular systolic function based on echocardiography. Multivariable linear regression was used to analyze the relationship between CCT and outcomes.

Results

The median was 61 years old (interquartile range, 51-69), and 23% were female. Indication was aneurysm in 65% and dissection in 24%. Median preoperative LVEF was 60% (55%-62%). Median CCT and cardiopulmonary bypass times were 135 minutes (93-165 minutes) and 181 minutes (142-218 minutes), respectively. In-hospital mortality occurred in 3%. Multivariable linear regression showed CCT was not associated with change in LVEF or change in right ventricular systolic function.

Conclusions

Our unique method of redosing DN cardioplegia appears to provide safe and effective myocardial protection for aortic surgery.

Key Words: aorta, cardioplegia, del Nido, myocardial ischemia, crossclamp, aortic surgery

Abbreviations and Acronyms: CCT, crossclamp time; CI, confidence interval; DN, del Nido; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; VIS, vasoactive inotropic score

Graphical abstract

Our dosing strategy shows no association between change in LVEF and crossclamp time.

Central Message.

Using our dosing strategy, which introduces “reverse ratio” 4:1 blood:del Nido crystalloid, del Nido cardioplegia is safe in aortic surgery, including cases with prolonged myocardial ischemic time.

Perspective.

The safety of del Nido cardioplegia had not yet been widely studied in complex cardiac surgery with prolonged clamp times. By describing a dosing method and showing clinical outcomes from cases with crossclamp times between 30 minutes to 280 minutes, surgeons may more confidently adopt del Nido cardioplegia for a wider variety of cases.

There are many different cardioplegia solutions of varying compositions used for myocardial arrest and protection in cardiac surgery, and the choice of cardioplegia is often up to institution or surgeon preference. Most conventional blood cardioplegia requires a dose every 15 to 20 minutes. del Nido (DN) cardioplegia solution was originally developed for pediatric and congenital heart surgery and was widely adopted for its ability to provide myocardial protection for 90 minutes after a single induction dose.1,2 The solution uses lidocaine and magnesium to arrest the myocardium in a depolarized state.

More recently, DN cardioplegia has been used in adult cardiac surgery, and its safety compared with conventional cardioplegia solutions has been documented in adult operations including coronary artery bypass graft,3, 4, 5, 6 valve operations,3,7, 8, 9, 10, 11 reoperative aortic valve surgery,12 and more recently ascending aortic surgery.13 In operations with prolonged crossclamp time (CCT), however, there is no consensus regarding timing, quantity, and route of additional doses.14 By our knowledge, fewer than 40 operations using DN with CCT greater than 3 hours have been shared in literature.

In a study by Lenoir and colleagues11 on aortic root surgery with CCTs up to 4 hours, patients in their DN group had greater cardiac biomarkers after 150 minutes of ischemic time compared with their conventional cardioplegia group. In their methods for operations that appeared to exceed 90 minutes of CCT, DN cardioplegia was administered with a 1250-mL antegrade initiation dose in a 1:4 ratio of blood to DN crystalloid, with an additional dose administered at 60 minutes, again in a 1:4 ratio. The authors rationalized the increased biomarkers in the DN cohort by citing literature that showed that repeated doses of DN cardioplegia may lead to reduced cardiac functional recovery and negative inotropic effects, speculating that this effect may be due to myocardial concentration of lidocaine.15 In contrast, a study on ascending aortic surgery showed no difference in postoperative biomarkers between blood and DN cardioplegia; their DN redosing strategy included additional doses in 1:4 ratio every 60 minutes.13

Although DN cardioplegia continues to be administered in adult cardiac operations, there still exists a well-grounded hesitancy to use it for prolonged complex cases. We developed a unique method of dosing DN cardioplegia, which was used in aortic operations with myocardial ischemia times up to 280 minutes. The present study aimed to analyze postoperative outcomes of these cases to assess its safety and effectiveness of the DN dosing strategy. We hypothesized that the described method of redosing DN cardioplegia would be safe for aortic surgery.

Methods

Ethical Statement

This protocol (#AAAR2949) was approved by the Columbia University Irving Medical Center institutional review board with waiver of patient consent on December 14, 2021.

Patients

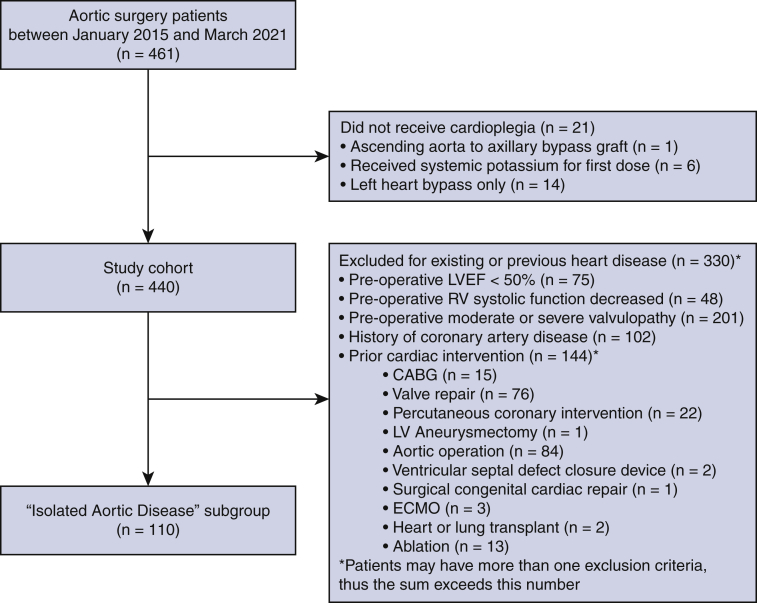

All patients who underwent open thoracic aortic surgery by a single surgeon (H.T.) at our Aortic Center between January 2015 and March 2021 were included. Patients were excluded if they did not receive a full first dose of cardioplegia (n = 20) or if they received systemic potassium as their first dose (n = 6). The final study cohort was 440 patients (Figure E1). Patient demographics, operative details, and postoperative outcomes were obtained from our Aortic Center database and review of electronic medical records. Cardioplegia characteristics were obtained from our institutional perfusion database. To better describe the clinical characteristics of the study cohort based on the redosing strategy delineated herein, the patients were divided into 3 groups based on CCT: CCT <90 minutes (n = 100), CCT 90 ≤ X < 180 minutes (n = 268), and CCT ≥ 180 minutes (n = 72).

Figure E1.

Consort diagram presenting exclusion criteria for the whole cohort of 440 patients and the isolated aortic disease subgroup of 110 patients. LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; RV, right ventricle; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LV, left ventricular; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

To better understand the safety of this dosing strategy on an “unremarkable heart,” a subgroup analysis was conducted of patients who had undergone isolated aortic operation without any concomitant cardiac operation or any pre-existing functional or structural heart disease. For this group, patients with a preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%, decreased preoperative right ventricular systolic function (RVSF), moderate or severe valvulopathy, history of coronary artery disease, or previous cardiac intervention were excluded, leaving a subset of 110 patients in the “isolated aortic disease” subgroup (Figure E1).

Surgical Technique

Surgical indication was determined based on most recent guidelines.16,17 An open aneurysm repair was recommended for patients with aneurysms ≥55 mm and recommended for some patients based on individual risk assessment for aneurysms 50 to 55 mm. Patients with aneurysms 45 to 50 mm may be offered a repair at a concomitant open cardiac procedure. Acute type A dissections were repaired with emergent surgery. The aortic valve was spared during aortic root replacement with reimplantation techniques whenever appropriate.18, 19, 20 When replacement was necessary, the prosthetic valve was chosen based on guidelines and patient preference. Supra-aortic vessels were individually reconstructed using a multibranch graft. The arterial cannulation site was typically placed in the distal ascending aorta with the option of using the axillary artery, based on surgeon preference and aortic pathology. Femoral cannulation was considered to be the last option. Distal aortic anastomosis in arch replacement procedures was performed under moderate hypothermia (24-28 °C, based on nasopharyngeal temperature) and with bilateral antegrade cerebral perfusion.

All operations used DN cardioplegia via the following protocol, visualized in Figure 1 and Video Abstract. At the time of the aortic crossclamp, a 1000-mL initiation dose composed of 1 part patient blood to 4 parts DN crystalloid was introduced, 750 mL antegrade through the aortic root (or directly through the coronary ostia if significant aortic insufficiency was present) and 250 mL retrograde through the coronary sinus. After 90 minutes of crossclamp time and every 30 minutes thereafter, a 250-mL dose was introduced retrograde in a 4:1 blood:DN crystalloid “reverse ratio.” In addition, at 90 minutes of crossclamp time and every 90 minutes thereafter, a 4:1 reverse ratio dose was introduced via the right coronary artery for 2 minutes at a line pressure of 200 mm Hg (approximately 100-400 mL). Topical cooling was not used. A left ventricular vent was used in all cases.

Figure 1.

Our dosing strategy uses del Nido cardioplegia and features redoses starting at 90 minutes of myocardial ischemic time and every 30 minutes thereafter. Based on our study of 440 patients undergoing aortic surgery, del Nido cardioplegia appears to provide safe and effective myocardial protection for aortic operations up to 280 minutes of crossclamp time. RCA, Right coronary artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; VIS, vasoactive inotropic score.

The composition of DN cardioplegia in both 1:4 standard ratio and 4:1 reverse ratio compared to standard cardioplegia is displayed in Table E1. Standard ratio was used in initiation doses to induce arrest with sufficient hyperkalemia and lidocaine. Reverse ratio was used at our institution after literature suggested that lidocaine in cardioplegia may accumulate to toxic levels if continually dosed.15,21 After careful calculation, we found that reversing the ratio to 4:1 blood:DN crystalloid for maintenance doses lowered the amount of lidocaine while also providing enough cardioplegia to maintain myocardial quiescence.

Study End Points

The primary outcomes of interest were change in LVEF and change in RVSF comparing preoperative and postoperative values, measured from echocardiography. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was used if available, and data were supplemented from intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) if TTE data was insufficient or missing (Table E2). Preoperative values were obtained from TTE done closest to the date of operation. The median and interquartile range (IQR) days between preoperative TTE and date of operation was 43 days (6-113 days) for our cohort. Postoperative values were obtained from predischarge TTE, with a median and IQR of 6 days (4-11 days) between operation and predischarge TTE. Nearly all (413/415, 99.5%) predischarge echo reports were official reading from the Columbia University Irving Medical Center Cardiac Echo Laboratory, which regularly monitors for quality and interobserver variability and were read in accordance with American Society of Echocardiography criteria. Although one half (n = 235, 53%) of the preoperative TTE reports were from the same Columbia University Irving Medical Center laboratory, the rest were scanned from outside cardiologists, including 8% (n = 37) of reports from Columbia- or New York Presbyterian–affiliated sources. In the cases that LVEF was reported as a range, the average of the range was used. Eight patients (1.8%) did not have LVEF data on either preoperative and/or predischarge echocardiogram and thus were excluded from the analysis of change in LVEF (Table E3). For change in RVSF, 42 patients (9.5%) were excluded since they did not have data on preoperative and/or postoperative echocardiogram (Table E4).

Secondary outcomes were in-hospital mortality, vasoactive inotropic score (VIS) at intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and uneventful recovery. VIS is a weighted sum of inotropes and vasoconstrictors such as dobutamine and norepinephrine and is a known predictor of mortality and morbidity after cardiac surgery.22 Uneventful recovery is a binary composite end point describing any patient discharged from the hospital without in-hospital mortality, any stroke, reoperation for bleeding, respiratory failure, acute renal failure, deep sternal infection, postcardiotomy shock, or permanent pacemaker implantation in the postoperative period.23

Data Definitions

Change in LVEF was calculated as the difference between the postoperative LVEF and the preoperative LVEF. RVSF was reported categorically on echocardiogram on an ordinal scale ranging from normal, mildly decreased, mildly to moderately decreased, moderately decreased, moderately to severely decreased, to severely decreased. Change in RVSF was defined as the number of categories changed from the preoperative RVSF to the postoperative RVSF and could be zero (for no change), positive (for increased RVSF after operation), or negative (for decreased RVSF). Stroke, reoperation for bleeding, respiratory failure, acute renal failure, and deep sternal infection were consistent with the definitions of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database.24 Postcardiotomy shock was defined as any patient requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the postoperative period.

Statistical Analysis

R version 4.0.4 statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used for all analysis. Patient characteristics were analyzed using the ‘tableone’ package. Continuous variables were all found to be non-normally distributed by the Shapiro–Wilks Test, and were expressed as median (IQR) and analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables were expressed as a percentage and were compared using the χ2 test. Outcomes were analyzed against the independent variable crossclamp time as a continuous variable in all regression models, even though crossclamp time was categorically divided into groups in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 for descriptive purposes. Change in RVSF was calculated as a continuous variable and analyzed with linear regression.25 Multivariable linear regression was used to analyze continuous outcomes (change in LVEF, change in RVSF, and VIS), whereas multivariable logistic regression was used to analyze binary outcomes (in-hospital mortality and uneventful recovery). For multivariable analysis, independent variables were selected based on clinical significance and previous literature; variable selection was additionally informed by variables with an alpha of ≤0.10 on univariable analysis. The ‘rms’ package was used to analyze the binary outcomes and to create cubic spline figures with 3 knots after adjusting for covariates. Missing data was equal to or less than 10% in all variables and was excluded from analyses (Table E5).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by crossclamp time

| Patient characteristics | All patients (n = 440), N (%) median [IQR] | CCT <90 min (n = 100), N (%) median [IQR] | CCT 90 <X < 180 min (n = 268), N (%) median [IQR] | CCT ≥180 min (n = 72), N (%) median [IQR] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61 [51-69] | 66 [58-75] | 60 [49-69] | 56 [46-62] | <.001∗ |

| Female | 100 (23) | 50 (50) | 46 (17) | 4 (6) | <.001∗ |

| BSA | 2.04 [1.88-2.20] | 1.91 [1.75-2.13] | 2.05 [1.91-2.21] | 2.17 [2.01-2.33] | <.001∗ |

| Hypertension | 325 (74) | 84 (84) | 193 (72) | 48 (67) | .021∗ |

| On dialysis | 5 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (0) | 3 (4) | .068 |

| Diabetes | 61 (14) | 19 (19) | 30 (11) | 12 (17) | .118 |

| Endocarditis | 25 (6) | 2 (2) | 11 (4) | 12 (17) | <.001∗ |

| CLD | 57 (13) | 11 (11) | 40 (15) | 6 (8) | .269 |

| CVD | 50 (11) | 15 (15) | 26 (10) | 9 (13) | .343 |

| PVD | 103 (23) | 23 (23) | 60 (22) | 20 (28) | .628 |

| Preoperative LVEF | 60 [55-62] | 60 [55-62.5] | 60 [52.5-62.5] | 57.5 [54-60] | .524 |

| Low EF (<40%) | 32 (7) | 3 (3) | 27 (10) | 2 (3) | .018∗ |

| Moderate or severe AS | 61 (14) | 18 (18) | 39 (15) | 4 (6) | .058 |

| Moderate or severe AI | 119 (27) | 11 (11) | 84 (31) | 24 (33) | <.001∗ |

| Primary indication | |||||

| Aneurysm | 288 (65) | 61 (61) | 184 (689) | 43 (60) | .208 |

| Dissection | 106 (24) | 28 (28) | 62 (23) | 16 (22) | .575 |

| Valvular | 28 (6) | 7 (7) | 16 (6) | 5 (7) | .915 |

| Obstruction | 2 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | .195 |

| Infection | 11 (2) | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | 5 (7) | .029∗ |

| Hematoma | 6 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | .810 |

| Urgent/emergent | 214 (49) | 45 (45) | 141 (53) | 28 (39) | .084 |

CCT, Crossclamp time; IQR, interquartile range; BSA, body surface area; CLD, chronic lung disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; EF, ejection fraction; AS, aortic stenosis (moderate or severe); AI, aortic insufficiency (moderate or severe).

P value < .05.

Table 2.

Operative details by crossclamp time

| Operative detail | All patients (n = 440), N (%) median [IQR] | CCT <90 min (n = 100), N (%) median [IQR] | CCT 90 < X < 180 min (n = 268), N (%) median [IQR] | CCT ≥180 min (n = 72), N (%) median [IQR] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascending only | 12 (3) | 9 (9) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | <.001∗ |

| Proximal extension | 205 (47) | 30 (3) | 137 (51) | 38 (53) | .001∗ |

| VSRR | 84 (19) | 1 (1) | 63 (24) | 20 (28) | <.001∗ |

| Bentall | 82 (19) | 9 (9) | 55 (21) | 18 (25) | .013∗ |

| AV procedure | 39 (9) | 20 (2) | 19 (7) | 0 (0) | <.001∗ |

| Distal extension | 98 (22) | 56 (56) | 42 (16) | 0 (0) | <.001∗ |

| Hemiarch | 22 (5) | 15 (15) | 7 (3) | 0 (0) | <.001∗ |

| Partial/total | 76 (17) | 41 (41) | 35 (13) | 0 (0) | <.001∗ |

| Proximal + distal | 125 (28) | 5 (5) | 86 (32) | 34 (47) | <.001∗ |

| Root + hemiarch | 17 (4) | 1 (1) | 12 (5) | 4 (6) | .219 |

| Root + partial/total | 23 (5) | 0 (0) | 13 (5) | 10 (14) | <.001∗ |

| AVR + hemiarch | 45 (10) | 3 (3) | 31 (12) | 11 (15) | .016∗ |

| AVR + partial/total | 40 (9) | 1 (1) | 30 (11) | 9 (13) | .006∗ |

| Additional procedures | |||||

| Mitral valve | 30 (7) | 1 (1) | 19 (7) | 10 (14) | .004∗ |

| Tricuspid | 9 (2) | 1 (1) | 6 (2) | 2 (3) | .674 |

| CABG | 78 (18) | 12 (12) | 45 (17) | 21 (29) | .012∗ |

| CPB time, min | 180 [142-217] | 123 [96.5-165] | 179 [154-204] | 261 [230-295] | <.001∗ |

| CCT, min | 135 [93-164] | 72 [59-80] | 138 [113-156] | 206 [189-225] | <.001∗ |

| Circulatory arrest | 219 (50) | 56 (56) | 129 (48) | 34 (47) | .363 |

“Partial/total” indicates partial or total arch replacement. CCT, Crossclamp time; IQR, interquartile range; VSRR, valve-sparing root replacement; AV, aortic valve; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass.

P value < .05.

Table 3.

Postoperative outcomes by CCT

| Postoperative outcome | All patients (n = 440), N (%) median [IQR] | CCT <90 min (n = 100), N (%) median [IQR] | CCT 90 < X < 180 min (n = 268), N (%) median [IQR] | CCT ≥180 min (n = 72), N (%) median [IQR] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inotropes on ICU admittance | 335 (76) | 67 (67) | 204 (76) | 64 (89) | .004∗ |

| VIS on ICU admission | 4.94 [1.05-10.22] | 3.3 [0-9.2] | 4.5 [1.1-9.5] | 7.6 [3-12.9] | .001∗ |

| Length of ICU stay, d | 3 [1.6-6.1] | 2.9 [1.4-5.6] | 2.8 [1.5-5.9] | 4.7 [2.3-9.6] | .004∗ |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 8 [6-14] | 9 [6-15] | 8 [6-13] | 10 [7-21] | .020∗ |

| Uneventful recovery | 276 (63) | 70 (70) | 172 (64) | 34 (47) | .007∗ |

| In-hospital mortality | 11 (3) | 4 (4) | 5 (2) | 2 (3) | .500 |

| Re-exploration for bleed | 22 (5) | 4 (4) | 13 (5) | 5 (7) | .672 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 30 (7) | 2 (2) | 19 (7) | 9 (13) | .025∗ |

| Respiratory failure | 128 (29) | 25 (25) | 71 (27) | 32 (44) | .007∗ |

| Stroke | 26 (6) | 9 (9) | 10 (4) | 7 (10) | .053 |

| Acute renal failure | 27 (6) | 4 (4) | 19 (7) | 5 (7) | .672 |

| Deep sternal infection | 4 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | .307 |

| Postcardiotomy shock | 15 (3) | 2 (2) | 7 (3) | 6 (8) | .040∗ |

| Change in LVEF (%) | 0 [−5 to 2.5] | 0 [−4.88 to 2.5] | 5 [−5 to 2.5] | 0 [−2.5 to 2.6] | .546 |

| Decrease in RVSF | 85 (21) | 18 (20) | 57 (24) | 10 (15) | .333 |

CCT, Crossclamp time; IQR, interquartile range; ICU, intensive care unit; VIS, vasoactive inotropic score; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function.

P value < .05.

Results

Preoperative patient characteristics are described in Table 1 for the total cohort and shown in groups according to crossclamp time (n = 440). Compared with the 100 patients whose crossclamp time was less than 90 minutes, the patients with the longest crossclamp times (≥180 minutes, n = 72) were younger in age (56 vs 66, P < .001), had greater body surface area (2.17 vs 1.91, P < .001), had a greater incidence of preoperative aortic insufficiency (33% vs 11%; P < .001), and had a greater history of infective endocarditis (17% vs 2%, P < .001). Overall, the most common primary indication for surgery was aneurysm in 288 (65%) patients. Dissection (n = 106, 24%) and valvulopathy (n = 28, 6%) were the next most common; the remaining handful of cases had a primary indication of infection, hematoma, or obstruction.

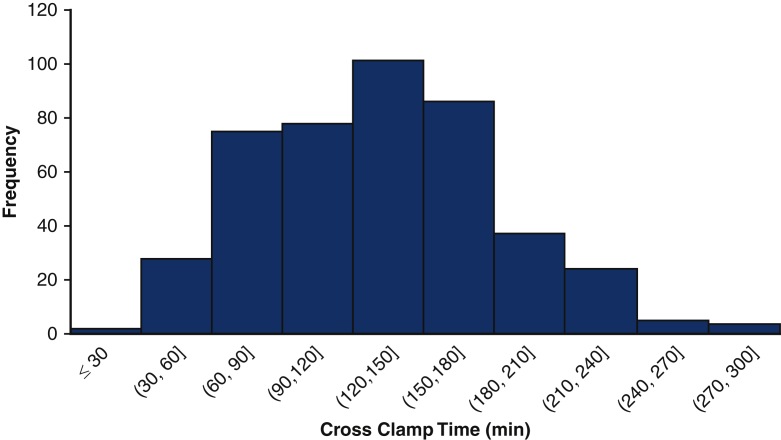

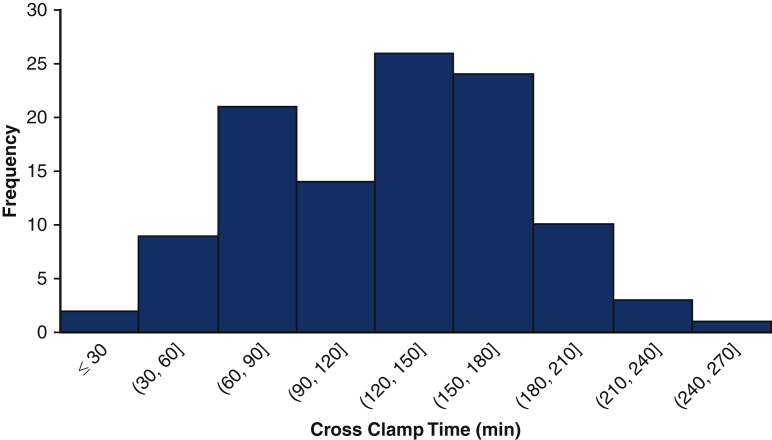

Figure 2 shows the distribution of crossclamp times of the cohort. The operative characteristics are shown in Table 2. The median was 135 minutes with an IQR of 93-165. One half (n = 219, 50%) required the use of circulatory arrest. Only 12 (3%) patients had isolated ascending arch replacement, and nearly one half (n = 205, 47%) had proximal extension including valve-sparing root replacement, Bentall, or procedure of the aortic valve. The remaining patients had a procedure with either a distal extension (n = 98, 22%) or both proximal and distal extensions (n = 125, 28%). The most common additional procedures were coronary artery bypass graft (n = 78, 18%) and mitral valve procedures (n = 30, 7%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of crossclamp times of 440 aortic surgery patients receiving del Nido cardioplegia, including cases between 27 minutes and 278 minutes.

Primary Outcomes

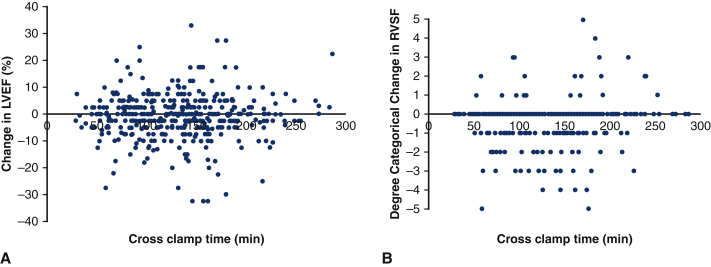

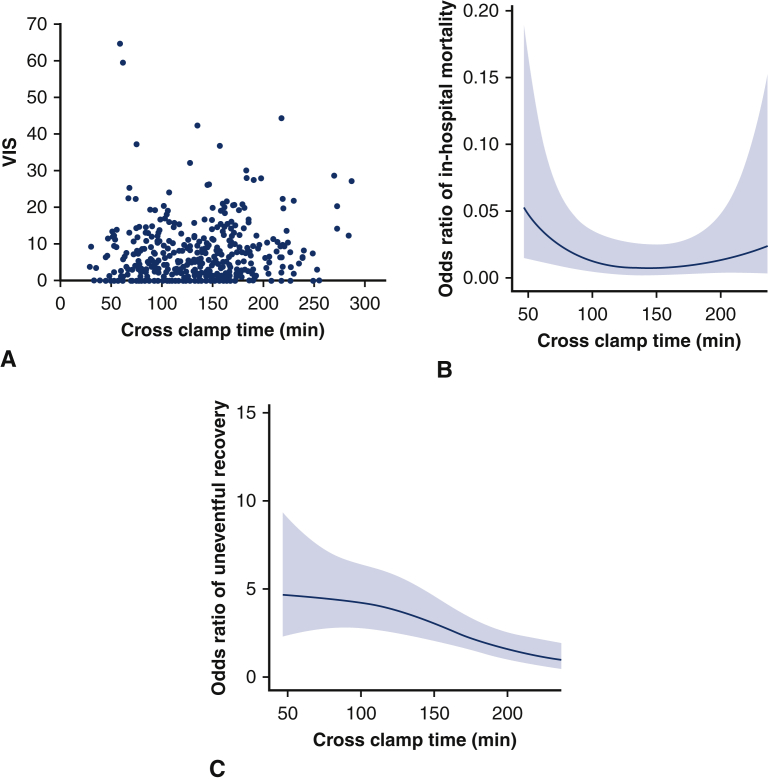

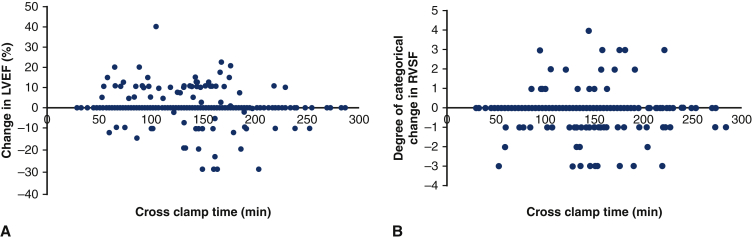

The median change in LVEF was 0% (IQR –5 to 2.5), with 79 (18%) of patients having no change in LVEF, 161 (37%) improving in LVEF, and 191 (43%) decreasing. On multivariable linear regression adjusting for preoperative LVEF and chronic lung disease, there was no significant relationship between CCT and change in LVEF (coefficient estimate = 0.001, 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.013 to 0.015, P = .879; Figure 3, A, Table E6). There was no relationship between CCT and change in LVEF after excluding patients with preoperative aortic valvulopathy and who underwent an aortic valve operation (Figure E2). Because circulatory arrest may contribute some hypothermia and thus extra myocardial protection, the primary outcomes were also studied in patients that did not have circulatory arrest (n = 221, 50%). In patients without circulatory arrest, crossclamp time was not a predictor in change in LVEF (P = .119) (Figure E3, A).

Figure 3.

Change in left ventricular ejection fraction (A) and change in right ventricular systolic function (B) against crossclamp time for 440 patients undergoing aortic surgery using the described del Nido dosing technique. There was no relationship between crossclamp time and change in LVEF (P = .879) or change in RVSF (P = .204) after multivariable linear regression. LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function.

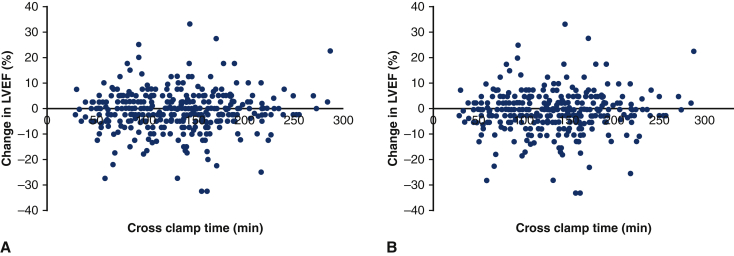

Figure E2.

Change in LVEF by crossclamp time in aortic surgery patients that using the described del Nido dosing strategy after excluding patients with preoperative aortic insufficiency (A) or aortic stenosis (B) and subsequent aortic valve operation. On multivariable analysis, cross clamp time was not found to be a predictor for change in LVEF in the group without patients with corrected aortic insufficiency (coefficient estimate = 0.002; 95% CI, 0.988-1.016; P = .814) or corrected aortic stenosis (coefficient estimate = 0.004; 95% CI, 0.990-1.019; P = .566). LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; CI, confidence interval.

Figure E3.

Change in LVEF (A) and change in RVSF (B) by crossclamp time in aortic surgery patients using the described del Nido dosing strategy but who did not undergo circulatory arrest. On multivariable analysis, crossclamp time was not found to be a predictor for change in LVEF (coefficient estimate = 0.017; 95% CI, 0.996-1.039; P = .119) but was a positively correlated with change in RVSF (coefficient estimate = 0.004; 95% CI, 1.001-1.007; P = .004). LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function; CI, confidence interval.

Most patients (n = 292, 66%) did not have a change in RVSF on echocardiography after the operation. Nearly 1 in 5 (n = 84, 19%) of patients had decreased RVSF after operation; 5% (n = 22) had increased RVSF. In univariate analysis on change in RVSF, preoperative RVSF, sex, history of diabetes, and urgent or emergent operation status were identified to be have an association with an α < 0.10. On multivariable linear regression adjusting for these 4 covariates, there was no relationship between CCT and change in RVSF (coefficient estimate = 0.001, 95% CI, –0.001 to 0.003, P = .204; Figure 3, B, Table E6). In patients without circulatory arrest, crossclamp time was found to be a predictor in change in RVSF (P = .004; Figure E3, B).

Secondary Outcomes

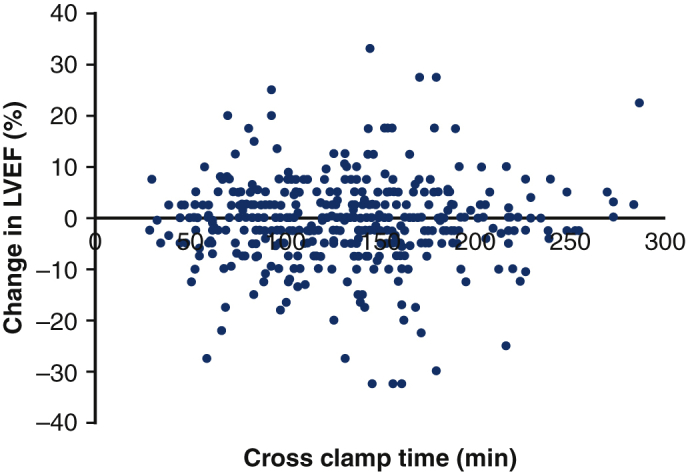

More than three-quarters (n = 335, 76%) of the total cohort were on inotropes or vasopressors upon admission to the ICU, with a median VIS of 4.94 (1.05-10.22) (Table 3). Patients with longer crossclamp times had a greater percentage of inotrope use and greater VIS at time of ICU admission. In analyzing the effect of CCT on VIS, the following variables were selected for multivariate analysis based on clinical importance: age, infective endocarditis, chronic lung disease, cerebrovascular disease, cardiopulmonary bypass time, preoperative LVEF, primary indication of dissection, and urgent or emergent operation status. After adjusting for these covariates, there was no relationship between CCT and VIS (coefficient estimate = −0.016, 95% CI, −0.041 to 0.008, P = .195) (Figure 4, A, Table E6).

Figure 4.

Vasoactive inotropic score (VIS) (A), odds ratio of in-hospital mortality (B), and odds ratio of uneventful recovery (C) by crossclamp time for 440 patients undergoing aortic surgery using the described del Nido dosing technique. There was no relationship between crossclamp time and VIS after multivariable linear regression (P = .195) or crossclamp time and in-hospital mortality after multivariable logistic regression (P = .250) Crossclamp time was found to be a predictor of uneventful recovery after adjusting for covariates (P = .002).

In-hospital mortality occurred in 11 patients (3%). There was no relationship between CCT and in-hospital mortality on multivariable logistic regression controlling for age and preoperative LVEF (odds ratio, 0.991; 95% CI, 0.997-1.006; P = .250) (Figure 4, B, Table E7).

As shown in Table 3, most (n = 276, 63%) patients had an uneventful recovery. In multivariable logistic regression, the odds ratio of uneventful recovery decreased with crossclamp time after controlling for the same covariates as VIS (odds ratio, 0.993; 95% CI, 0.988-0.997: P = .002) (Figure 4, C, Table E7). Incidence of pacemaker implantation, respiratory failure, and postcardiotomy shock were increased in patients with the greatest crossclamp times and were likely drivers of the relationship between crossclamp time and uneventful recovery. We reviewed patients with postcardiotomy shock to understand its increased incidence in the group with longer crossclamp times and found that the clamp time was rather prolonged by intraoperative technical challenges and deemed not to be due to issues with cardioplegia (Table E8).

Subgroup Analysis

Preoperative characteristics, operative details, and postoperative outcomes for the isolated aortic disease subgroup are shown in Table E9. The subgroup with isolated aortic disease (n = 110) had lower rates of cerebrovascular disease (n = 5, 5%) when compared with the remaining 332 patients (n = 45, 14%, P = .015), and otherwise was not different in terms of preoperative characteristics aside from the variables selected in creating the subgroup. The distribution of crossclamp times is shown in Figure E4 and was not different from the remaining patients (133 minutes vs 135 minutes, P = .335), although cardiopulmonary bypass time was shorter in this subgroup (171 minutes vs 185 minutes, P = .030).

Figure E4.

Distribution of crossclamp times of the 110 aortic surgery patients receiving del Nido cardioplegia in the isolated aortic disease subgroup.

In the postoperative period, the isolated aortic disease subgroup had lower VIS at ICU admission (3.14 vs 5.24, P = .003), shorter ICU stays (2.0 days vs 3.4 days, P = .006), and shorter hospital stays (7 days vs 9 days, P = .001). There was also lower incidence of permanent pacemaker implantation (2% vs 9%, P = .029) and respiratory failure (16% vs 33%, P = .001) postoperatively, contributing to a greater rate of uneventful recovery (79% vs 57%, P < .001). Although the subgroup had comparable changes in LVEF, there was a lower incidence of decreased RVSF after operation (14% vs 24%, P = .054). There was no relationship between crossclamp time and change in LVEF (P = .324), change in RVSF (P = .234), or VIS (P = .562) (Table E10) in multivariable linear regression. Unlike the whole cohort, there was no relationship between crossclamp time and uneventful recovery in this subgroup (P = .662) (Table E10).

Discussion

The present study examined the utility of a unique dosing strategy for DN cardioplegia in aortic surgery. We observed no difference in primary outcomes of change in LVEF and change in RVSF, as well as no difference in VIS score at ICU admission and in-hospital mortality across CCT with our dosing strategy. While the odds ratio of uneventful recovery increased with CCT, this was not counter to our hypothesis, since uneventful recovery is a composite outcome relying on the lack of several postoperative events, most of which are not dependent on myocardial function. In patients without circulatory arrest, CCT was not a predictor of change in LVEF but was a predictor of change in RVSF; interestingly, change in RVSF improves with CCT in this group rather than decline, and thus does not contradict our hypothesis. Overall, the described method of dosing DN cardioplegia appears safe for myocardial protection during ischemic periods of up to 5 hours.

Our DN dosing strategy starts with a single administration of cardioplegia for the first 90 minutes of CCT, followed by subsequent doses every 30 minutes. While maintaining the clinical utility of DN with 90 uninterrupted minutes of crossclamp time, the transition to reverse ratio 4:1 blood:DN crystalloid in maintenance doses may reduce potential cardiotoxic effects that can be a concern when using multiple concentrated doses of DN for prolonged crossclamp time. This reconciles the conceptual difficulties of the redosing strategies of previous studies. Lenoir and colleagues11 speculated that the extended periods of time in between doses, one of the perceived advantages of DN cardioplegia due to its time-saving effect, allowed for disappearance of the protective components and cooling temperatures of cardioplegia, resulting in the elevated biomarkers found in their DN subgroup; previous literature15 implying that more frequent doses of lidocaine-based cardioplegia (such as DN) may cause harmful negative inotropic effects prevented their surgeons from applying DN more frequently.

Our use of reverse ratio 4:1 blood:DN crystalloid in maintenance doses decreases the amount of crystalloid the patient receives and dilutes the lidocaine concentration, reducing its cardiotoxic potential. The reverse ratio also dilutes the potassium concentration to one more similar to the “low potassium” composition of conventional cardioplegia. Therefore, once the reverse ratio is introduced, succeeding doses follow a redosing timing more similar to conventional cardioplegia. Maintenance doses are started at 90 minutes after the induction dose, with a retrograde coronary sinus dose every 30 minutes and an antegrade dose to right coronary artery every 60 minutes. Since the induction dose is sufficient for 90 minutes and following doses are administered every 30 minutes, there is still a time-saving benefit compared with whole-blood cardioplegia, which is redosed every 15 to 20 minutes after the induction dose.

Study Limitations

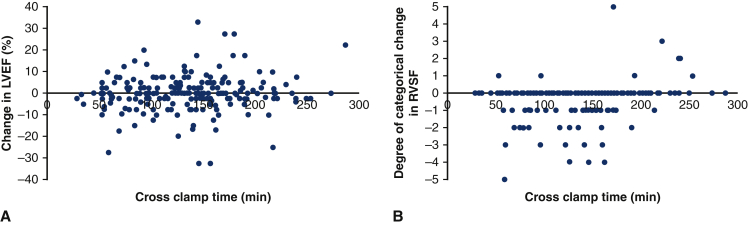

This is a single-center, single-surgeon retrospective study which may introduce bias and limit generalizability to other surgeons or institutions. In addition, the lack of a comparison group does not allow for direct analysis against other cardioplegic myocardial protection methods. However, we believe that the descriptive data of our unique redosing strategy provides an important preliminary data and insights in understanding the utility of this cardioplegic solution in aortic surgery. While surgeons at our institution have used this strategy for other adult cardiac operations with satisfactory outcomes, we urge caution on generalizing these findings to all of adult cardiac surgery. This study relies on echocardiographic parameters of cardiac function, LVEF and RVSF, to assess the safety and effectiveness of this redosing strategy in myocardial protection. RVSF is calculated by visual assessment, which is somewhat supported by echocardiography guidelines but not yet fully standardized.26 This did not permit complex or nuanced assessment of RVSF but nonetheless provided a reasonably reliable assessment of global RV function. While we believe the values obtained from the standardized reports, we did not have access to a core laboratory for standardized review. Although the majority of patients had TTE reports both pre- and postoperatively, preoperative TEE data were used 16% of the time and postoperative TEE data was used 3% of the time. Although TEE data might have been confounded by other clinical factors, such as general anesthesia or pharmacologic support, we believe this bias is stronger in postoperative TEE, which was used less often, as 97% of patients had a discharge TTE on file. Additional analysis calculated solely by TEE values shows no relationship between CCT and primary outcomes (Figure E5). Lastly, while we were able to analyze clinical outcomes, we did not have data for cardiac biomarkers such as troponins, which would have added another dimension to our analysis of myocardial protection.

Figure E5.

Change in LVEF (A) and change in RVSF (B) by crossclamp time in aortic surgery patients that using the described del Nido dosing strategy based on TEE data. On multivariable analysis, cross clamp time was not found to be a predictor for change in LVEF (coefficient estimate = –0.017; 95% CI, 0.999-1.001; P = .951) but or change in RVSF (coefficient estimate = 0.000; 95% CI, 0.999-1.000; P = .745). LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function; CI, confidence interval.

Conclusions

There is still uncertainty about the safety of DN cardioplegia in operations with prolonged myocardial ischemic time and no established method on how to redose. This paper describes a novel perfusion method of DN cardioplegia and its outcomes for diverse aortic operations with crossclamp times up to 287 minutes, including 72 operations with crossclamp times exceeding 180 minutes. This paper introduces the concept of “reverse ratio” DN cardioplegia, which consists of a lower concentration of lidocaine appropriate for redosing every 30 minutes. Our study found no relationship between crossclamp time and change in ventricular systolic function, postoperative cardiovascular support, or in-hospital mortality, suggesting that this redosing method may provide sufficient myocardial protection, even in prolonged cardiac ischemic periods. This paper also took the unique opportunity to study a cohort of patients with isolated aortic disease undergoing prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass; this subgroup also showed no relationship between crossclamp time and clinical outcomes. Future studies on biomarkers such as troponin could elucidate the effects and validate the use of “reverse ratio” DN cardioplegia in prolonged clamp times.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health 2T35HL007616-41 (to M.M.C.); H.T. was supported by the Rudin Foundation.

Supplementary Data

A brief summary of the paper, “A Novel Dosing Strategy of Del Nido Cardioplegia in Aortic Surgery.” Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S2666-2736(22)00192-9/fulltext.

Appendix E1

Table E1.

Composition of del Nido cardioplegia in standard and reverse ratio

| Cardioplegia component | Conventional cardioplegia | Del Nido cardioplegia standard ratio 1:4 blood:crystalloid | Del Nido cardioplegia “reverse ratio” 4:1 blood:crystalloid |

|---|---|---|---|

| K, mmol/L | 23.5 | 20.55 | 8.139 |

| Mg, mmol/L | 0.66 | 6.33 | 2.198 |

| Ca, mmol/L | 1.8 | 0.450 | 1.800 |

| Lidocaine, mmol/L | 0 | 0.420 | 0.104 |

Calculations used the following blood electrolyte levels: potassium 4.0 mmol/L, magnesium 2.0 mg/dL, calcium 9.0 mg/dL. K, Potassium; Mg, magnesium; Ca, calcium.

Table E2.

Echocardiography data, n = 440

| Echocardiography | LVEF, n (%) | RVSF, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative TTE or TEE | 436 (99) | 417 (95) |

| Preoperative TTE | 361 (82) | 333 (76) |

| Preoperative TEE | 432 (98) | 356 (81) |

| Postoperative TTE or TEE | 436 (99) | 421 (96) |

| Discharge TTE | 412 (94) | 376 (85) |

| Postoperative TEE | 420 (95) | 361 (82) |

| Both preoperative and postoperative echocardiography | 432 (98) | 398 (90) |

LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram.

Table E3.

Sensitivity analysis for patients missing LVEF data

| Variable | LVEF data (n = 432), N (%), median [IQR] | Missing LVEF data (n = 8), N (%), median [IQR] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative characteristics | |||

| Age | 61 [50-69] | 60 [56-78] | .297 |

| Female | 98 (23) | 2 (25) | 1.000 |

| Body surface area | 2.04 [1.88-2.20] | 2.12 [1.93-2.23] | .636 |

| Hypertension | 319 (74) | 6 (75) | 1.000 |

| On dialysis | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes | 60 (14) | 1 (13) | 1.000 |

| Infective endocarditis | 24 (6) | 1 (13) | .944 |

| Chronic lung disease | 54 (13) | 3 (38) | .120 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 50 (12) | 0 (0) | .646 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 102 (24) | 1 (13) | .753 |

| Preoperative LVEF | 60 [55-62] | 33 [33-55]∗ | .067 |

| Moderate or severe aortic stenosis | 60 (14) | 1 (13) | 1.000 |

| Moderate or severe aortic insufficiency | 116 (27) | 3 (38) | .787 |

| Primary indication | |||

| Aneurysm | 285 (66) | 3 (38) | .193 |

| Dissection | 102 (24) | 4 (50) | .189 |

| Valvular | 28 (7) | 0 (0) | .989 |

| Obstruction | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Infection | 10 (2) | 1 (13) | .493 |

| Hematoma | 6 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Urgent or emergent status | 211 (49) | 3 (38) | .780 |

| Operative details | |||

| Ascending only | 12 (3) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Proximal extension | 204 (47) | 1 (13) | .111 |

| VSRR | 84 (19) | 0 (0) | .351 |

| Bentall | 82 (19) | 0 (0) | .364 |

| AV procedure | 38 (9) | 1 (13) | 1.000 |

| Distal extension | 94 (22) | 4 (50) | .141 |

| Hemiarch replacement | 20 (5) | 2 (25) | .072 |

| Partial/total arch replacement | 74 (17) | 2 (25) | .911 |

| Proximal + distal extensions | 122 (28) | 3 (38) | .857 |

| Root + hemiarch | 17 (4) | (0) | 1.000 |

| Root + partial/total arch | 23 (5) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| AVR + hemiarch | 42 (10) | 3 (38) | .048† |

| AVR + partial/total arch | 40 (9) | 0 (0) | .778 |

| Additional procedures | |||

| CABG | 76 (18) | 2 (25) | .939 |

| Mitral valve | 29 (7) | 1 (13) | 1.000 |

| Tricuspid valve | 9 (2) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| CPB time, min | 180 [143-216] | 219 [131-249] | .372 |

| Crossclamp time, min | 135 [93-164] | 108 [91-155] | .541 |

| Use of circulatory arrest | 219 (50) | 3 (38) | .731 |

| Postoperative outcomes | |||

| Inotropes on ICU admission | 329 (76) | 6 (75) | 1.000 |

| VIS on ICU admission | 4.92 [1.05-9.67] | 10.73 [7.33-13.16] | .191 |

| Length of ICU stay, d | 3.0 [1.6-6.0] | 8.9 [4.7-9.7] | .014† |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 8 [6-14] | 11 [10-16] | .182 |

| Uneventful recovery | 274 (63) | 2 (25) | .063 |

| In-hospital mortality | 9 (2) | 2 (25) | .003† |

| Reexploration for bleed | 21 (5) | 1 (13) | .870 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 29 (7) | 1 (13) | 1.000 |

| Respiratory failure | 122 (28) | 6 (75) | .013† |

| Stroke | 23 (5) | 3 (38) | .002† |

| Acute renal failure | 26 (6) | 1 (13) | .989 |

| Deep sternal infection | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Postcardiotomy shock | 14 (3) | 1 (13) | .655 |

LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction; IQR, interquartile range; VSRR, valve-sparing root replacement; AV, aortic valve; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass time; ICU, intensive care unit; VIS, vasoactive inotropic score.

n = 5 (63%).

P value < .05.

Table E4.

Sensitivity analysis for patients missing RVSF data

| Variable | RVSF data (n = 398), N (%), median [IQR] | Missing RVSF data (n = 42), N (%), median [IQR] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative characteristics | |||

| Age | 60 [50-69] | 63 [56-70] | .135 |

| Female | 87 (22) | 13 (31) | .253 |

| Body surface area | 2.04 [1.87-2.20] | 2.06 [1.95-2.29] | .429 |

| Hypertension | 291 (73) | 34 (81) | .360 |

| On dialysis | 4 (1) | 1 (2) | .972 |

| Diabetes | 54 (14) | 7 (17) | .751 |

| Infective endocarditis | 23 (6) | 2 (5) | 1.000 |

| Chronic lung disease | 49 (12) | 8 (19) | .320 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 46 (12) | 4 (10) | .889 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 93 (23) | 10 (24) | .677 |

| Preoperative LVEF | 59 [55-62] | 60 [56-63] | .523 |

| Moderate or severe aortic stenosis | 56 (14) | 5 (12) | .880 |

| Moderate or severe aortic insufficiency | 106 (26) | 13 (31) | .677 |

| Primary indication | |||

| Aneurysm | 263 (66) | 25 (60) | .497 |

| Dissection | 94 (24) | 12 (29) | .600 |

| Valvular | 25 (6) | 3 (7) | 1.000 |

| Obstruction | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Infection | 9 (2) | 2 (5) | .640 |

| Hematoma | 5 (1) | 1 (2) | 1.000 |

| Urgent or emergent status | 192 (48) | 22 (52) | .728 |

| Operative details | |||

| Ascending only | 10 (3) | 2 (5) | .724 |

| Proximal extension | 185 (47) | 20 (48) | 1.000 |

| VSRR | 75 (19) | 9 (21) | .842 |

| Bentall | 75 (19) | 7 (17) | .892 |

| AV procedure | 35 (9) | 4 (10) | 1.000 |

| Distal extension | 86 (22) | 12 (29) | .403 |

| Hemiarch replacement | 17 (4) | 5 (12) | .074 |

| Partial/total arch replacement | 69 (17) | 7 (17) | 1.000 |

| Proximal + distal extensions | 117 (29) | 8 (19) | .217 |

| Root + hemiarch | 16 (4) | 1 (2) | .918 |

| Root + partial/total arch | 23 (6) | 0 (0) | .217 |

| AVR + hemiarch | 40 (10) | 5 (12) | .913 |

| AVR + partial/total arch | 38 (10) | 2 (5) | .457 |

| Additional procedures | |||

| CABG | 69 (17) | 9 (21) | .654 |

| Mitral valve | 25 (6) | 5 (12) | .292 |

| Tricuspid valve | 8 (2) | 1 (2) | 1.000 |

| CPB time, min | 181 [141-216] | 180 [144-216] | .952 |

| Crossclamp time, min | 135 [93-164] | 131 [97-166] | .998 |

| Use of circulatory arrest | 197 (50) | 22 (52) | .847 |

| Postoperative outcomes | |||

| Inotropes on ICU admission | 299 (75) | 36 (86) | .180 |

| VIS on ICU admission | 4.58 [1.00-9.67] | 7.66 [2.29-11.84] | .109 |

| Length of ICU stay, d | 3.0 [1.6-6.0] | 5.0 [2.0-8.4] | .113 |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 8 [6-14] | 10 [7-14] | .181 |

| Uneventful recovery | 253 (64) | 23 (55) | .340 |

| In-hospital mortality | 8 (2) | 3 (7) | .132 |

| Re-exploration for bleed | 19 (5) | 3 (7) | .766 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 25 (6) | 5 (12) | .292 |

| Respiratory failure | 112 (28) | 16 (38) | .241 |

| Stroke | 22 (6) | 4 (10) | .484 |

| Acute renal failure | 21 (5) | 6 (14) | .048∗ |

| Deep sternal infection | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Postcardiotomy shock | 11 (3) | 4 (10) | .064 |

| Change in LVEF (%) | 0.0 [−5.0 to 2.5] | 0 [−5.0 to 5.0]† | .906 |

RVSF, Right ventricular systolic function; IQR, interquartile range; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; VSRR, valve-sparing root replacement; AV, aortic valve; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass time; ICU, intensive care unit; VIS, vasoactive inotropic score.

P value < .05.

n = 36 (86%).

Table E5.

Missing data, n = 440

| Variable | Missingness (%) |

|---|---|

| BSA | 1 (0.0) |

| Last hematocrit | 8 (1.8) |

| Change in LVEF | 8 (1.8) |

| Preoperative LVEF | 4 (0.9) |

| Postoperative LVEF | 4 (0.9) |

| Change in RVSF | 42 (9.5) |

| Preoperative RVSF | 23 (5.2) |

| Postoperative RVSF | 19 (4.3) |

| VIS | 5 (1.1) |

BSA, Body surface area; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function; VIS, vasoactive inotropic score.

Table E6.

Multivariable analysis for predictors of continuous outcomes

| Variable | Coefficient estimate | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change in LVEF | |||

| Crossclamp time | 0.001 | −0.013, 0.015 | .879 |

| Preoperative LVEF | −0.339 | −0.423 to –0.255 | <.001∗ |

| Chronic lung disease | −4.937 | −7.123 to –2.750 | <.001∗ |

| Change in RVSF | |||

| Crossclamp time | 0.001 | −0.001 to 0.003 | .204 |

| Preoperative RVSF | −0.676 | −0.814 to –0.538 | <.001∗ |

| Female | 0.308 | 0.073-0.543 | .011∗ |

| Diabetes | 0.184 | −0.084 to 0.452 | .179 |

| Urgent or emergent status | 0.212 | 0.029-0.396 | .024∗ |

| VIS | |||

| Crossclamp time | −0.016 | −0.041 to 0.008 | .195 |

| Age | 0.061 | 0.007-0.116 | .029∗ |

| Preoperative LVEF | −0.104 | −0.187 to -0.020 | .016∗ |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.245 | −2.224 to 2.714 | .846 |

| Chronic lung disease | 2.596 | 0.319-4.873 | .026∗ |

| History of endocarditis | 2.797 | −0.709 to 6.304 | .119 |

| Indication of dissection | 1.252 | −0.802 to 3.306 | .233 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time | 0.039 | 0.019-0.059 | .000∗ |

| Urgent or emergent status | 0.165 | −1.333 to 1.663 | .829 |

CI, Confidence interval; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function; VIS, vasoactive inotropic score.

P value < .05.

Table E7.

Multivariable analysis for predictors of binary outcomes

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uneventful recovery | |||

| Crossclamp time | 0.993 | 0.988-0.997 | .002∗ |

| Age | 0.976 | 0.959-0.992 | .004∗ |

| Preoperative LVEF | 1.035 | 1.010-1.060 | .004∗ |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.589 | 0.298-1.162 | .127∗ |

| Chronic lung disease | 0.652 | 0.343-1.237 | .191 |

| History of endocarditis | 0.259 | 0.094-0.707 | .008∗ |

| Indication of dissection | 0.262 | 0.160-0.428 | <.001∗ |

| Urgent or emergent status | 0.945 | 0.612-1.458 | .798 |

| In-hospital mortality | |||

| Crossclamp time | 0.991 | 0.977-1.006 | .250 |

| Age | 1.033 | 0.981-1.089 | .218 |

| Preoperative LVEF | 0.991 | 0.900-1.000 | .051 |

CI, Confidence interval; LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction.

P value < .05.

Table E8.

Analysis of patients with postcardiotomy shock

| Age | Sex | CPB time, min | CCT, min | Indication | Mechanical support | Outcome | Intra-/postoperative events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 69 | M | 120 | 74 | Type A | ECMO POD4 | Mortality 6 months postoperative | None |

| 80 | M | 151 | 116 | Root aneurysm | Peripheral ECMO POD12 | In-hospital mortality POD49 | Postoperative tamponade and cardiac arrest |

| 35 | M | 168 | 102 | Type A | Central ECMO | d/c home | Coronary malperfusion due to aortic dissection, preoperative cardiac arrest, postoperative LVEF <10% |

| 57 | M | 180 | 112 | Aortic aneurysm | Ax/Fem ECMO | d/c acute rehab | Difficult reoperation after previous type A repair |

| 59 | M | 218 | 180 | Type A | Central ECMO | d/c to SNF POD44 | Coronary malperfusion due to aortic dissection and rupture |

| 78 | M | 222 | 135 | Aortic aneurysm | Central ECMO | In-hospital mortality POD5 (stroke) | Reoperation of a zone 2 frozen elephant trunk |

| 31 | F | 242 | 171 | Type A | Femoral ECMO | d/c home | Coronary malperfusion due to aortic dissection, preoperative LVEF 10% |

| 41 | M | 252 | 59 | Aortic aneurysm | Central ECMO, central RVAD | In-hospital mortality POD1 | Profound postbypass shock requiring ECMO, open abdomen and chest |

| 46 | M | 265 | 217 | Root aneurysm | Femoral ECMO | d/c to rehabilitation | Postoperative tamponade |

| 65 | M | 307 | 181 | Reoperation for root PSA | Ax/Fem ECMO | d/c to SAR | Prolonged CCT due to intractable bleeding |

| 52 | M | 310 | 218 | Prosthetic root abscess | Femoral ECMO | d/c home | Both coronary ostia involved in abscess cavity, requiring extensive reconstruction |

| 56 | M | 341 | 219 | Type A | Central ECMO | In-hospital mortality POD11 | Coronary malperfusion due to type A, right and left coronary arteries were bypassed with SVGs off of ascending sidearm branches |

| 66 | M | 378 | 146 | Thoracic aorta rupture | Central ECMO | d/c home | Prolonged CCT due to aortic rupture |

| 38 | M | 387 | 204 | Reoperation for root PSA | Ax/Fem ECMO | d/c to SNF | Prolonged CCT due to need for extensive LVOT reconstruction |

| 72 | F | 439 | 164 | Type A | Central ECMO | d/c to rehabilitation | Coronary malperfusion due to aortic dissection, required left and right coronary bypasses |

CPB, Cardiopulmonary bypass; CCT, crossclamp time; M, male; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; POD, postoperative day; d/c, discharged; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; Ax/Fem, axillary artery and femoral vein; SNF, skilled nursing facility; F, female; RVAD, right ventricular assist device; PSA, pseudoaneurysm; SVG, saphenous vein graft; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract.

Table E9.

Patient characteristics for isolated aortic disease cohort

| Variable | Isolated aortic disease (n = 110), N (%), median [IQR] | Remaining patients (n = 330), N (%), median [IQR] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative characteristics | |||

| Age | 60 [50-68] | 61 [51-70] | .367 |

| Female | 32 (29) | 68 (21) | .088 |

| Body surface area | 2.07 [1.91-2.22] | 2.03 [1.87-2.20] | .431 |

| Hypertension | 75 (68) | 250 (76) | .150 |

| On dialysis | 1 (1) | 4 (1) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes | 12 (11) | 49 (15) | .381 |

| Infective endocarditis | 0 (0) | 25 (8) | .006∗ |

| Chronic lung disease | 9 (8) | 48 (15) | .119 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5 (5) | 45 (14) | .015∗ |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 23 (21) | 80 (24) | .559 |

| Primary indication | |||

| Aneurysm | 79 (72) | 209 (63) | .132 |

| Dissection | 26 (24) | 80 (24) | 1.000 |

| Valvular | 3 (3) | 25 (8) | .114 |

| Obstruction | 1 (1) | 1 (0) | 1.000 |

| Infection | 1 (1) | 10 (3) | .378 |

| Hematoma | 2 (2) | 4 (1) | 1.000 |

| Urgent or emergent status | 54 (49) | 160 (49) | 1.000 |

| Operative details | |||

| Ascending only | 1 (1) | 11 (3) | .311 |

| Proximal extension | 48 (44) | 157 (47) | .544 |

| VSRR | 35 (32) | 49 (15) | <.001∗ |

| Bentall | 11 (10) | 71 (22) | .011∗ |

| AV procedure | 2 (2) | 37 (11) | .005∗ |

| Distal extension | 34 (31) | 64 (19) | .017∗ |

| Hemiarch replacement | 9 (8) | 13 (4) | .130 |

| Partial/total arch replacement | 25 (23) | 51 (16) | .109 |

| Proximal + distal extensions | 27 (25) | 98 (30) | .360 |

| Root + hemiarch | 9 (8) | 8 (2) | .015∗ |

| Root + partial/total arch | 9 (8) | 14 (4) | .174 |

| AVR + hemiarch | 5 (5) | 40 (12) | .037∗ |

| AVR + partial/total arch | 4 (4) | 36 (11) | .035∗ |

| CPB time, min | 171 [143-197] | 185 [141-226] | .030∗ |

| Crossclamp time, min | 133 [86-165] | 135 [95-164] | .335 |

| Use of circulatory arrest | 49 (45) | 170 (52) | .248 |

| Postoperative outcomes | |||

| Inotropes on ICU admission | 76 (69) | 259 (79) | .061 |

| VIS on ICU admission | 3.14 [0-7.97] | 5.24 [1.23-11.10] | .003∗ |

| Length of ICU stay, d | 2.0 [1.3-5.0] | 3.4 [1.8-6.8] | .006∗ |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 7 [5-12] | 9 [6-14] | .001∗ |

| Uneventful recovery | 87 (79) | 189 (57) | <.001∗ |

| In-hospital mortality | 0 (0) | 11 (3) | .113 |

| Re-exploration for bleed | 2 (2) | 20 (6) | .130 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 2 (2) | 28 (9) | .029∗ |

| Respiratory failure | 18 (16) | 110 (33) | .001∗ |

| Stroke | 4 (4) | 22 (7) | .350 |

| Acute renal failure | 3 (3) | 24 (7) | .136 |

| Deep sternal infection | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 1.000 |

| Postcardiotomy shock | 0 (0) | 15 (5) | .049∗ |

| Change in LVEF (%) | 0 [−2.5 to 2.5] | 0 [−5 to 4.25] | .501 |

| Decrease in RVSF | 14 (14) | 70 (24) | .054 |

IQR, Interquartile range; VSRR, valve-sparing root replacement; AV, aortic valve; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass time; ICU, intensive care unit; VIS, vasoactive inotropic score; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function.

P value < .05.

Table E10.

Outcomes of the isolated aortic disease subgroup

| Variable | Crossclamp time coefficient estimate | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change in LVEF | −0.007 | −0.026 to 0.012 | .324 |

| Change in RVSF | −0.001 | −0.003 to 0.001 | .234 |

| VIS | −0.016 | −0.071 to 0.039 | .562 |

| Crossclamp time odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uneventful recovery | 0.997 | 0.985-1.009 | .662 |

CI, Confidence interval; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSF, right ventricular systolic function; VIS, vasoactive inotropic score.

References

- 1.Charette K., Gerrah R., Quaegebeur J., Chen J., Riley D., Mongero L., et al. Single dose myocardial protection technique utilizing del Nido cardioplegia solution during congenital heart surgery procedures. Perfusion. 2012;27:98–103. doi: 10.1177/0267659111424788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matte G.S., del Nido P.J. History and use of del Nido cardioplegia solution at Boston Children's Hospital. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2012;44:98–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ad N., Holmes S.D., Massimiano P.S., Rongione A.J., Fornaresio L.M., Fitzgerald D. The use of del Nido cardioplegia in adult cardiac surgery: a prospective randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155:1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.09.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timek T., Willekes C., Hulme O., Himelhoch B., Nadeau D., Borgman A., et al. Propensity matched analysis of del Nido cardioplegia in adult coronary artery bypass grafting: initial experience with 100 consecutive patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:2237–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timek T.A., Beute T., Robinson J.A., Zalizadeh D., Mater R., Parker J.L., et al. Del Nido cardioplegia in isolated adult coronary artery bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160:1479–1485.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yerebakan H., Sorabella R.A., Najjar M., Castillero E., Mongero L., Beck J., et al. Del Nido cardioplegia can be safely administered in high-risk coronary artery bypass grafting surgery after acute myocardial infarction: a propensity matched comparison. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:141. doi: 10.1186/s13019-014-0141-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ota T., Yerebakan H., Neely R.C., Mongero L., George I., Takayama H., et al. Short-term outcomes in adult cardiac surgery in the use of del Nido cardioplegia solution. Perfusion. 2016;31:27–33. doi: 10.1177/0267659115599453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanetra K., Gerber W., Shrestha R., Domaradzki W., Krzych Ł., Zembala M., et al. The del Nido versus cold blood cardioplegia in aortic valve replacement: a randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;159:2275–2283.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.05.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vistarini N., Laliberté E., Beauchamp P., Bouhout I., Lamarche Y., Cartier R., et al. Del Nido cardioplegia in the setting of minimally invasive aortic valve surgery. Perfusion. 2017;32:112–117. doi: 10.1177/0267659116662701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziazadeh D., Mater R., Himelhoch B., Borgman A., Parker J.L., Willekes C.L., et al. Single-dose del Nido cardioplegia in minimally invasive aortic valve surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:P471–P476. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenoir M., Bouhout I., Jelassi A., Cartier R., Poirier N., El-Hamamsy I., et al. Del Nido cardioplegia versus blood cardioplegia in adult aortic root surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;162:514–522.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorabella R.A., Akashi H., Yerebakan H., Najjar M., Mannan A., Williams M.R., et al. Myocardial protection using del nido cardioplegia solution in adult reoperative aortic valve surgery. J Card Surg. 2014;29:445–449. doi: 10.1111/jocs.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willekes H., Parker J., Fanning J., Leung S., Spurlock D., Murphy E., et al. Del Nido cardioplegia in ascending aortic surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. November 1, 2021 doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2021.10.008. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waterford S.D., Ad N. Del Nido cardioplegia: questions and (some) answers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. November 27, 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.11.053. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Govindapillai A., Hancock Friesen C., O’Blenes S.B. Protecting the aged heart during cardiac surgery: single-dose del Nido cardioplegia is superior to multi-dose del Nido cardioplegia in isolated rat hearts. Perfusion. 2016;31:135–142. doi: 10.1177/0267659115588633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erbel R., Aboyans V., Boileau C., Bossone E., Bartolomeo R.D., Eggebrecht H., et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2873–2926. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiratzka L.F., Bakris G.L., Beckman J.A., Bersin R.M., Carr V.F., Casey D.E., Jr., et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons,and Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:e27–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bethancourt C.N., Blitzer D., Yamabe T., Zhao Y., Nguyen S., Nitta S., et al. Valve-sparing root replacement versus bio-bentall: inverse propensity weighting of 796 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113:1529–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen S.N., Yamabe T., Zhao Y., Kurlansky P.A., George I., Smith C.R., et al. Bicuspid-associated aortic root aneurysm: mid- to long-term outcomes of David V versus the Bio-Bentall procedure. Semin. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;33:933–943. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2021.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamabe T., Zhao Y., Kurlansky P.A., Nitta S., Borger M.A., George I., et al. Assessment of long-term outcomes: aortic valve reimplantation versus aortic valve and root replacement with biological valved conduit in aortic root aneurysm with tricuspid valve. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;59:658–665. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezaa389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hearse D.J., O'Brien K., Braimbridge M.V. Protection of the myocardium during ischemic arrest. Dose-response curves for procaine and lignocaine in cardioplegic solutions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1981;81:873–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koponen T., Karttunen J., Musialowicz T., Pietiläinen L., Uusaro A., Lahtinen P. Vasoactive-inotropic score and the prediction of morbidity and mortality after cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:428–436. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamabe T., Zhao Y., Sanchez J., Kelebeyev S., Bethancourt C.R., McMullen H.L., et al. Probability of uneventful recovery after elective aortic root replacement for aortic aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:1485–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adult cardiac surgery database data Collection: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2021. https://www.sts.org/registries-research-center/sts-national-database/adult-cardiac-surgery-database/data-collection

- 25.Robitzsch A. Why ordinal variables can (almost) always be treated as continuous variables: clarifying assumptions of robust continuous and ordinal factor analysis estimation methods. Front Educ. 2020;5:1–7. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.589965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudski L.G., Lai W.W., Afilalo J., Hua L., Handschumacher M.D., Chandrasekaran K., et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. quiz 86-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A brief summary of the paper, “A Novel Dosing Strategy of Del Nido Cardioplegia in Aortic Surgery.” Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S2666-2736(22)00192-9/fulltext.