Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the pattern of substandard and falsified pharmaceutical products recall in Nepal.

Setting

We analysed drug recall notices issued by the Department of Drug Administration (DDA), Nepal, and systematically reviewed peer-reviewed research articles during January 2010 to December 2020.

Participants

This study did not include human participants. However, data were collected from 72 drug recall notices issued by DDA and four research papers.

Results

A total of 346 pharmaceutical products were recalled during the reported period. The number of recalled pharmaceutical products has increased significantly over the past decade in Nepal. The most frequently recalled drugs were antimicrobials followed by gastrointestinal medicines, vitamins and supplements and pain and palliative medicines among others. Number of imported recalled drugs were slightly higher (42.2%) than domestic recalled drugs (40.7%). Sixty-two percentage of recalled drugs were substandard, 11% were falsified and remaining 27% were not registered at the DDA. Similarly, higher number of modern drugs (62%) were recalled than traditional ones (35%). Hand sanitisers used to minimise COVID-19 transmission contributed significantly to the list of recalled pharmaceutical products in 2020. Most of these sanitisers contained significant amounts of methanol (as high as 75% v/v) instead of appropriate amount of ethyl or isopropyl alcohol. The peer-reviewed research papers reported issues with labelling, unregistered drugs and drugs failed in several laboratory testing.

Conclusion

Our analysis showed that number of recalls of substandard and falsified drugs are increasing in Nepal. Since the recall data in this paper did not include number of samples tested and location of samples collected, more studies to understand the prevalence of substandard and falsified drugs in Nepal is recommended.

Keywords: public health, COVID-19, health economics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to evaluate the pattern of drug recall in Nepal.

A comprehensive analysis of drug recall notice issued by Department of Drug Administration, Nepal, from January 2010 to December 2020.

Also includes a systematic review of peer-reviewed publications from 2010 to 2020 which reported poor quality drugs in Nepal.

It does not include number of samples tested, location of sample collected and impact of recall notice.

Since we looked at pattern of recall drugs, it did not report the rate of low-quality drugs over the last decade.

Introduction

Pharmaceutical products are essential to treat, prevent and save lives of millions of people globally.1 They should be safe, effective and of good quality. Such products should be prescribed by authorised medical practitioner and used rationally.2 However, pharmaceutical products that do not meet regulatory standards and quality threaten the health of the population of today and future. Such products may be substandard or low-quality or falsified. Substandard or falsified drugs could lead to drug resistance and put the lives of patients at risk in addition to increasing the economic and social burden on people.3 There are several reasons for the circulation of such substandard and falsified products in market such as lack of access to affordable, quality, safe and effective medical products and good governance as well as poor ethical practices in healthcare facilities and medicine outlets. Limited technical capacity in manufacturing, quality control, distribution and testing also contribute to this problem.4 5

Ozawa et al in a 2018 meta-analysis estimated that about 10.5% of the medicines worldwide are either substandard or falsified. Prevalence of low-quality pharmaceutical products is higher in low-income and middle-income countries (13.6%) compared with high-income countries. About 18.7% medicines have been estimated to be low-quality in Africa and 13.7% in Asia. The most substandard or falsified drugs are the antimalarials (19.1%).3

Nepal is one of the least developed countries6 that shares open and poorly regulated boarders with India and China. These two countries are considered as major producers of low-quality and falsified pharmaceutical products circulating in the global market.4 The domestic market for medical products in Nepal was estimated to be 70 billion Nepal rupees in 2019 which included drugs (36 billion), raw materials and surgical equipment.7 The Department of Drug Administration (DDA) authorises the distribution of all pharmaceutical products in Nepal including production, distribution, export and import. The DDA in Nepal is equivalent to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is responsible to prevent the misuse or abuse of drugs and allied pharmaceutical substances.8 Few studies in the past have indicated the circulation of substandard, counterfeit and unregistered drugs in the Nepali market.9–11 DDA Nepal recalls marketed drugs if the drugs do not fulfil any requirement as indicated in the Drug Act 2035 B.S.8 It then issues public alerts and warnings when substandard, falsified and unregistered medicine incidents are detected. Analysis of pattern of drug alerts, regulatory recalls and company led recalls could be helpful to understand major issues responsible for the availability of poor-quality drugs and devise appropriate actions to mitigate the problem.12 13 Analysis of medical product recall and alert are available from few countries such as the UK12 and the Saudi Arabia,14 which have shown a significant increase in the number of recalled drugs.

In this study, we report the pattern of recall of poor-quality drugs in Nepal by analysing drug recall notice issued by the DDA. We analysed temporal trend of low-quality drugs, types of drugs and formulations, origin of drugs and manufacturers and reasoning for recall. We also reviewed research publications that reported drug quality data.

Methodology

We analysed drug recall notices published by DDA Nepal from January 2010 to December 2020. The DDA publishes such notices in its bulletins, websites and newspapers (https://dda.gov.np/). We extracted all the information provided on the recall notice such as brand name, dosage form, batch number, manufacturing date, expiry date, recall date, reason for non-compliance and the manufacturer information. We used National List of Essential Medicines 2016 of Nepal to classify the recalled drugs into essential and non-essential drugs15 and the WHO definition to identify substandard, falsified and unregistered drugs.16 According to WHO definition, substandard drugs are authorised medical products but fail to meet quality standards or specifications or both. Similarly, falsified drugs are medical products that misrepresent their identity, composition or source.17 Pharmaceutical products that did not pass dissolution test, active pharmaceutical ingredient assay, microbial test, leakage test, friability, were non-compliance with the pharmacopoeia for physical appearance, fungal count, weight variation, particulate matter test, uniformity test, disintegration test and pH test were put together under the substandard category. Similarly, drugs that contained impurities, active ingredient not meant to be there, had price sticker without approval, or did not have product specification were classified as falsified pharmaceutical products. The drugs that were recalled as being not registered at DDA Nepal were classified under unregistered category. Unregistered drugs do not undergo evaluation and/or approval by DDA Nepal. Based on the brand names of each non-ayurvedic pharmaceutical product, we identified their generic names and then categorised them into different groups based on their therapeutic properties.

In addition to the recall notice, we systematically reviewed the published research works to find the reporting of low-quality drugs in Nepali market. We specifically searched peer-reviewed research articles from electronic databases such as PubMed (2010–2020), Web of Science (2010–2020), SpringerLink (2010–2020) and Google Scholar (2010–2020). We used the following search terms in conjunction with Boolean search term (‘OR’, ‘AND’) to identify related articles: ‘counterfeit*’, ‘substandard*’, ‘falsified*’, ‘fake’, ‘spurious’, ‘unregulated drugs’, ‘unregistered’ or ‘frauds’; combined with ‘drug’, ‘medicine’ or ‘pharmaceutical’; ‘Nepal*’. In Google Scholar same search terms were used, but instead of ‘Nepal*’, we used ‘intitle:Nepal’. The articles were screened and evaluated manually through the title and abstract based on inclusion criteria: date of publication (2010–2020), the language (English) in which the article was published, the article should contain data/information on the prevalence of falsified/spurious/counterfeit/substandard drugs and the location of experiment/research carried out. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Also excluded were opinion articles, letters, notes, conference papers, book chapters, editorials or comments or articles with no abstracts or articles with counterfeit or substandard medicines related to animals.

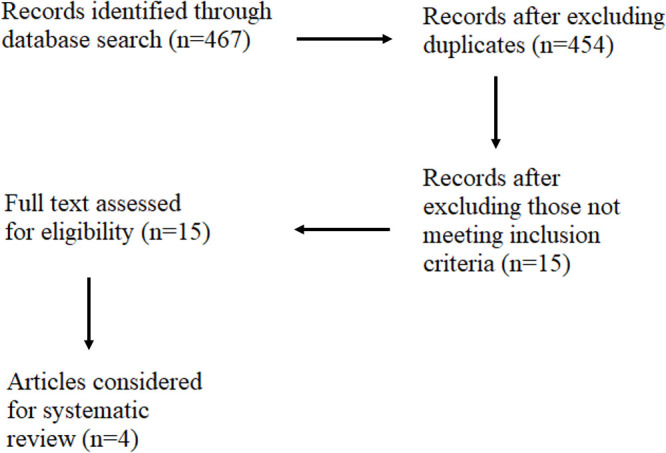

A flow chart of search procedure is given in figure 1. Initially, we identified 467 journal articles after a search of literature in four different databases: PubMed, SpringerLink, Web of Science and Google Scholar. We removed 13 duplicate articles and brought the number of articles to 454. By screening the title and abstract of these articles, we removed 439 articles and we considered only 15 in next step (see online supplemental table SI). We read the full text of these articles and excluded 11 articles because they did not follow the inclusion criteria. At last, four articles9–11 18 were found to be relevant that contained primary information on the prevalence of substandard, falsified and unregistered medicines in the Nepali market.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of research papers search procedure.

bmjopen-2021-053479supp001.pdf (49.3KB, pdf)

Statistical analyses of data such as χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test and simple linear regression were performed using R V.1.4.1106.

Patients and public involvement

Patient or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting and dissemination plans for this study.

Results

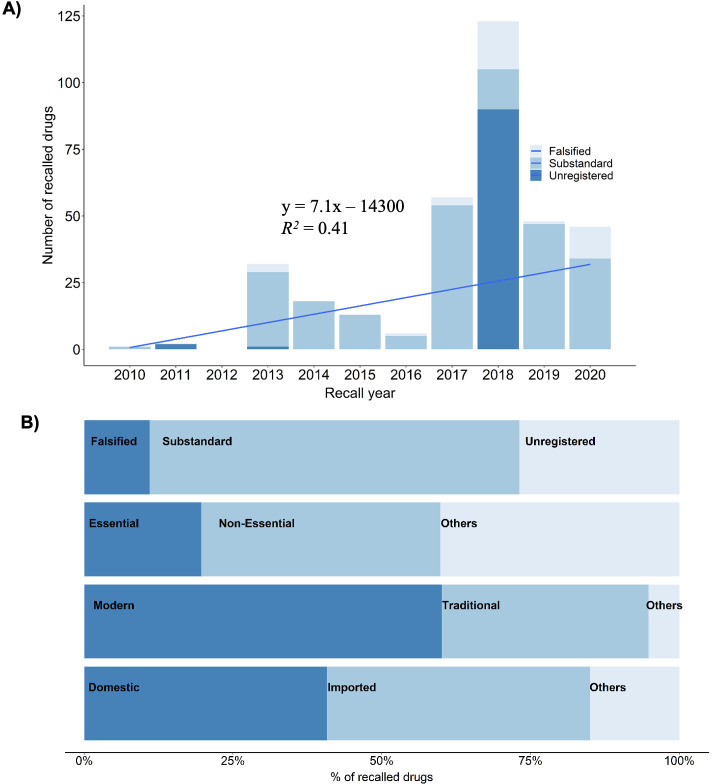

We analysed recalled drugs during the period of 2010–2020. During this period 346 pharmaceutical products were recalled by DDA Nepal. The number of recalled low-quality drugs in Nepal has significantly increased in the last decade (figure 2A, linear regression, p value<0.05, adjusted R2 value=0.335). We found that only one pharmaceutical product was recalled in 2010. The product was a lactate solution which is commonly used for fluid resuscitation. The solution was recalled from the Nepali market because it did not pass the sterility test. There was no recall in 2012. The year 2018 had the highest number of pharmaceutical products recalled (123 products, see figure 2A). Forty-six products were recalled in the year 2020, majority of which were hand sanitisers. The recalled pharmaceutical products were from 96 manufacturers mostly from Nepal and India, few from Australia, Bangladesh and China. Manufacturer of 91 recalled drugs were unknown. The recalled pharmaceutical products included a significantly (two-sided Fisher’s exact test, p value<0.001) higher number of imported medicines (153) items than domestically manufactured ones (141). The imported recalled products were manufactured mostly in India (97%, figure 2B) and in drugs from Australia, Bangladesh and China. Country of origin of 52 recalled pharmaceutical products were not identified.

Figure 2.

(A) Temporal trend of recalled pharmaceutical products in Nepal. (B) Contribution of different categories of pharmaceutical products in the recall list.

Sixty percentage (n=346) of recalled pharmaceutical products were modern or allopathic (208) and 35% were traditional or ayurvedic (120) (figure 2B). Two-sided Fisher’s exact test showed that significantly higher number of modern pharmaceutical products were recalled (p value<0.001). Twenty-seven percentage of the recalled drugs were unregistered at the DDA indicating they were not authorised to be distributed and sold in Nepal. Similarly, 20% of the recalled drugs, mostly allopathic, were listed as essential medicines. Forty percentage of the recalled drugs were non-essential allopathic (p value<0.001) and 40% were ayurvedic drugs. Essential medicines are distributed free of cost through government health centres15 and only allopathic drugs are listed as essential ones. Majority of the recalled pharmaceutical products were substandard (62%) followed by unregistered (27%) and falsified (11%) (see figure 2B). We found that the recall pattern among these three categories were significantly different (one-way χ2 test, p value<0.001, χ2=142.31, df=2).

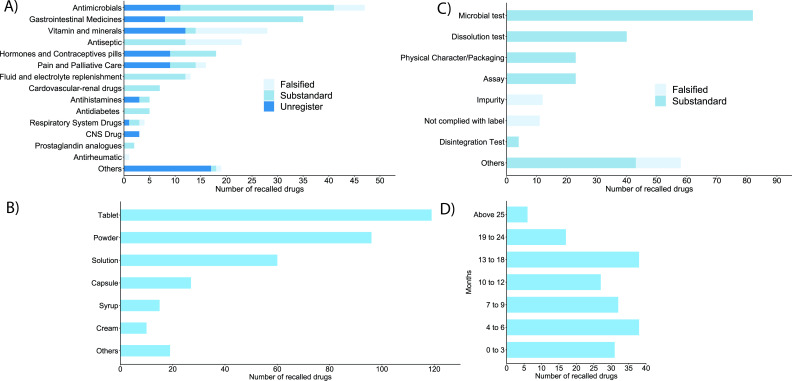

The top 10 most recalled drugs were antimicrobials (13.6%) followed by gastrointestinal medicines (10.1%), vitamins and minerals (8.1%), antiseptic (6.6), hormones and contraceptives (5.2%) and pain and palliative care medicines (4.6), fluid and electrolyte replenishment items (3.7%), cardiovascular and renal drugs (2.0%), anti-diabetes (1.4%) and antihistamines (1.4%) (see figure 3A). Remaining recalled drugs were central nervous system drugs, respiratory system drugs, prostaglandin analogues and antirheumatic agents. Nineteen drugs were not classified into any of those and labelled as ‘others’ because sufficient information was not available. Ayurvedic drugs were not included in this categorisation.

Figure 3.

(A) Categories of recalled drugs based on their therapeutics, (B) types of dosage forms of recalled drugs, (C) major reasons for recalling the pharmaceutical products, (D) self-life of recalled pharmaceutical products after the recall (in months).

The DDA provided reason(s) for every recalled pharmaceutical product. Large number of drugs (26.8%) were recalled because they were not registered at DDA. The most common reason for recall among registered drugs was the failure to comply with microbial test (23.7%) followed by failures in dissolution test (11.5%), in quantitative assay for active pharmaceutical ingredient (6.6%) and in physical characteristics and packaging (6.6%). Eleven products did not comply with labelling requirements and 12 had one or more impurities. Few samples categorised as ‘others’ were recalled due to failure in identification test and contained active ingredient in dietary supplements (see figure 3B). Tablets were the most recalled dosages forms followed by powder, solution, capsules, syrups/suspension and cream/ointment. Dosage forms of some products were not identifiable, and they are categorised as ‘others’ (figure 3C). The shelf-life of recalled drugs ranged from less than 3 months (16.4%) to more than 2 years at the time of recall (figure 3D).

Low-quality drugs reported in research papers

As stated in method section, only four research articles were included for detailed analysis. One of these articles reported by Jha18 assessed the quality of essential medicines available in 62 public healthcare facilities across 21 districts of Nepal. The authors tested 244 batches of 20 different generics of essential medicines and found that 37 batches failed to meet the required pharmacopoeial standards. The quality failed medicines included both supplied by Government of Nepal (62.2%) and purchased from local pharmacies (37.8%). The failed medicines included antibiotics, supplements, anti-diabetics and so on.

Providing required information on the label is another major issue. Most of the 759 pharmaceutical products from 37 Nepali pharmaceutical companies inspected in Chitwan in 2017 missed at least one critical information on the label such as drug quantity, name of pharmacopoeia, serial number of pharmaceutical industries, price list, drug classification and information in Nepali language.10 The reports showed that labels of 84% of drugs did not provide the directions for use. Similarly 90% of drug samples (n=40) in Kathmandu did not comply with the existing regulatory requirement on labelling and 42.5% brands did not indicate the pharmacopoeial standard.9 The same study showed that 40% of domestic and 28% imported brands failed to meet national criteria during laboratory analysis. On average, 32.5% samples were found to be of substandard quality in this study. Another study evaluated the availability and rationality of unregistered fixed-dose drug combinations (FDCs) in Nepal using snowball sampling method and Health Action International Asia-Pacific toolkit in 20 retail pharmacies. Forty-one unregistered fixed-dose anti-inflammatory/analgesic/antipyretics drug combinations were found in five major cities of Nepal. Regulatory authorities should initiate strict monitoring and appropriate regulatory mechanisms to prohibit the use of unregistered and irrational FDCs.11

Discussion

Low-quality medicines or related products are recalled from the market by manufacturing companies voluntarily or by the order of national or international drug regulatory bodies.19 Many recall incidents of poor quality medicine have been reported globally.20 For example, Johnson and Johnson recalled 200 000 bottles of liquid ibuprofen in 2013 due to possible contamination with plastic particles. The US FDA had recalled the contaminated vials of corticosteroid medication in 2012 which was manufactured by the New England Compounding Center.21 An analysis of drug recall in the UK has shown a 10-fold increase in the defective medicines from 2001 to 2011 mostly due to contamination and issues with packaging.12 Similarly, the number of drug recall reported by Saudi Arabia Drug Authority increased sixfolds from 2010 to 2018, in which the most commonly recalled drugs were antihypertensive drugs and antibiotics due to contamination and issues with non-compliance with manufacturer’s specifications.14

Our analysis showed that the overall trend of recalled drugs is increasing in Nepal. Starting from a single drug recall in 2010 to highest numbers (123) in 2018. In this year, most of the recalled drugs (90) were due to them not registered with the DDA. This indicates that the circulation of unregistered drugs in market is a serious issue in Nepal which may be contributed to by the open and unregulated border with India.

Both allopathic and ayurvedic medicines are widely used in Nepal. Allopathic medicines are the modern medicines that are manufactured synthetically whereas ayurvedic medicines are the traditional medicines which uses the natural remedies to improve health or to treat diseases. Both types of medicines are commercially manufactured in Nepal in addition to being imported mostly from India. There are two groups of manufacturers of ayurvedic drugs in Nepal. The first being the registered companies which sell their products in packages through registered shops. Second, the ayurvedic drugs are made by individuals or small business holders without being registered at DDA and sell their ayurvedic products in streets, through door-to-door service and through individual networks. We found that both allopathic and ayurvedic medicines were recalled due to their non-compliance with government standards. Ayurvedic medicines are used prominently in Nepali communities, and sometimes, they are used concomitantly with allopathic medicines.22 There has been an increasing interest in the study of traditional medicine in different parts of world.23 However, there is still lack of quality research and standards, and stringent regulatory environment for this sector.

Essential medicines are defined by WHO as the medicines that satisfy the priority healthcare needs of the population.24 The concept of essential medicines was adopted in 1986 A.D. in Nepal to enhance access of essential medicines to every individual. The main criteria for selection of the medicines in the National List of Essential Medicine (NLEM) of Nepal are public health relevance, efficacy, safety, cost-effectiveness and access of the drugs. The NLEM 2016 of Nepal contains 359 medicines thus having 86 medicines more than NLEM 2011.15 The following criteria were used for including a medicine in NLEM: approved and licenced in Nepal, relevance to a disease posing public health problem, proven efficacy and safety, aligned with standard treatment guideline of Nepal, stable under storage conditions, cost-effective and access. However in certain conditions, some medicines are excluded from the NLEM list: those banned in Nepal, over safety concerns, if medicine with higher efficiency, safety profile and lower cost is available, irrelevant to public health disease burden, antimicrobial resistant, medicine with abuse and misuse potential.15 Our study showed that some of the recalled allopathic medicines were essential drugs. Jha18 indicated the presence of high number of substandard essential medicines and majority of which were purchased by Government of Nepal. Essential medicines for various illnesses are supplied free of cost in Nepal through government hospitals, healthcare centres and health posts. Poor quality of essential medicines can have serious impact on public health. As significant proportion of drugs recalled by DDA included essential medicines distributed by Government of Nepal, there is enough room to improve the procurement practices and upgrading of health facilities in Nepal that store and distribute medicines. In one study25 that looked into the procurement practices in Nepal, it was reported that the majority of hospital pharmacies in Nepal use an expensive direct procurement model for purchasing medicines. They relied on doctors’ prescriptions to choose a particular brand, which may be influenced by pharmaceutical companies’ marketing strategies. Most of the hospital pharmacies procured only registered medicines, a minority reported purchasing unregistered medicines through unauthorised supply chains. Not all pharmacies followed Basel Statements during procurement of medicines. Such pharmacies may need awareness and training to fully adopt regulation of national and international policies to enhance accessibility to quality medicines.

Among the recalled groups, antimicrobial group of medicines had the highest frequency of recall incidents. Acharya and Wilson26 highlighted the problem of antimicrobial resistance in Nepal as an alarm bell for worse public health situation. Suboptimal dose or poorly manufactured antibiotic medicine increases the chance of antimicrobial resistance.27 Most of the recalled therapeutic categories of medicines like vitamins and minerals, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, other antipyretic and analgesic agents, antiseptics, fluid and electrolyte replenishment items and others are over-the-counter medicines that can be brought from the pharmacy without prescription. Such medicines can pose a significant threat patients who consume them.28 Few anti-diabetes medicines were also recalled. Consumption of such medicines may increase the incidence of macrovascular and microvascular complications due to compromised glucose control.29

Our study showed that some of the drugs were recalled due to failure in various laboratory tests like microbial test, assays, content uniformity test, weight variation, impurity test, dissolution test, friability test as well as identification and sterility test. Many of these failures can be linked to inadequate quality control measures during manufacturing and inappropriate procedures for transportation and storage and other logistic issues.17

Jha pointed out that only 13% of 62 health facility inspected followed medicine storage guidelines for light, heat and humidity.18 Keeping the temperature and humidity within a specified range is necessary because it has a major role in degradation of medicines. Another reason was failure to comply with claims and incorrect labelling. The DDA regulation requires appropriate labelling of marketed medicines to ensure patient safety. Thus, drug analysts and the drug regulators should be encouraged to remain vigilant about the possibility of counterfeiting possibility. They should conduct appropriate analysis including chemical, physical, package inspection and authentication efforts to ensure quality and safety of drugs getting to the ultimate user.30

Domestically produced and imported medicines in Nepal should have the registration license from DDA.8 Nonetheless, we found that high numbers of unregistered drugs were recalled during the inspection. Drug suppliers, wholesalers and even retailers should ensure that the drugs they are handling is duly registered with the national regulatory body to ensure only safe and efficacious drugs get to the patient. Also, the regulatory body should conduct post-market surveillance to ameliorate the situation. Unregistered medical products in Nepal may or may not have been registered in India. Since Nepal shares open and poorly regulated boarder with India, drugs registered in India are also easily sold in the Nepali market, especially in bordering districts. We found that nearly half of the total recalled medicines were imported from India. India is the leading country in counterfeit drug production, having as much as 35% of the world production originating within its borders.31

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the surge of substandard and falsified medical products including drugs, masks, sanitisers, diagnostic tests and vaccines and other essential medical products.32 Rampant circulation of falsified medical products during emergencies has happened throughout history.32 Counterfeit respirators and masks pose additional risk to healthcare workers.33 Falsified chloroquine was seized in Cameroon, Congo and Niger between March and May 2020. Chloroquine was controversially announced as the drug for the treatment of COVID-19.34 The US FDA uncovered nearly 1300 fraudulent products during early days of COVID-19.35 DDA Nepal has recently amended the standard for instant hand sanitiser in order to prohibit selling of substandard, falsified and unregistered sanitisers.36 Between September and November 2020, the DDA issued recall notices for 19 hand sanitisers which failed to comply with the standard guideline. Some sanitisers were found to contain methanol, rather than ethyl alcohol and isopropyl alcohol. Methanol is very toxic. Use of hand sanitiser containing methanol may cause transdermal absorption and increases the risk of systemic toxicity.37 The increase in the demand for hand sanitisers and other medicines in the face of COVID-19 has increased the growth of e-commerce. Online sale of pharmaceutical products has just started in Nepal during recent years. WHO has reported that 60% of medications purchased through the internet could be counterfeit or substandard, and more than 50% of medications purchased online from sites that concealed their actual physical address were found to be low-quality medicines.38 Nepali regulating agencies should pay special attention to this new method of doing business in Nepal to protect the people from consumption of low-quality and falsified medical products. Inexorable growth of online pharmacies, unregulated websites and social media platforms for business may contribute to the dispensing of unapproved, subpotent, counterfeit, expired or illegal drugs and prescription drugs without valid prescriptions.39

Recall and alert from regulating agencies is important step, however more actions are necessary to fully understand the substandard and falsified drugs circulation in the market and their potential impact. Naughton and Akgul13 argued that freely available drug alert and recall are not enough to estimate medicine quality. Researchers have suggested to regulatory agencies to publish more information such as exact number of recalled packs, numbers of samples collected and tested, performed tests and results and so on. Further, sampling methodologies for substandard and falsified (SF) prevalence studies are variable in terms of sample size, design methods consistency, reporting contextual factors, resulting in not reliable comparison across studies.40 Therefore a standardise protocol for testing and reporting, global legal framework and surveillance systems of substandard and falsified drugs are needed.41 This could potentially help to compare the results from different countries and understand from each other and make better policy interventions globally.13

Conclusion

In this paper, we presented a detailed pattern of low-quality and falsified drugs circulating in Nepal in the past decade using recall notice. We showed that the number of recalled drugs has significantly increased. This might be attributed either to a greater surveillance by DDA or actual increase in the levels of substandard, falsified and unregistered medicines in the market, similar to previous studies.12 However, our analysis was not enough to identify the exact cause of increase in the recalled drugs. Like global trends, antimicrobial drugs were the most recalled drugs in Nepal. The recall notices used did not provide information on the number of samples collected for testing or inspection and location of sample collection. Therefore, our analysis did not report the rate or prevalence of low-quality drugs. Since sample collection locations were not available, it was not possible to know the most vulnerable districts of Nepal for low-quality drugs. Therefore, more studies are needed to understand the prevalence of substandard and falsified drugs in Nepal covering different parts of the country on regular basis. We suggest having more stringent regulatory systems and implementation for pharmaceutical manufacturing industries and enhanced post marketing surveillance.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @SabitaT25927567, @girib71

Contributors: BG contributed to conceptualisation and study design, data analysis and manuscript revision. AN, MB contributed to data collection, analysis and first draft. ST contributed to data collection. BG is responsible for overall content as guarantor. All authors gave approval for the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Author compiled and curated raw data will be made available with a reasonable request to corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Seiter A. Health and economic consequences of counterfeit drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;85:576–8. 10.1038/clpt.2009.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . Pharmaceutical products. Available: http://www.who.int/topics/pharmaceutical_products/en/

- 3.Ozawa S, Evans DR, Bessias S, et al. Prevalence and estimated economic burden of substandard and Falsified medicines in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e181662. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.OECD, European Union Intellectual Property Office . Trade in counterfeit pharmaceutical products. OECD, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma N, Barstis T, Giri B. Advances in paper-analytical methods for pharmaceutical analysis. Eur J Pharm Sci 2018;111:46–56. 10.1016/j.ejps.2017.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Least developed country category: Nepal profile | department of economic and social Affairs. Available: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/least-developed-country-category-nepal.html

- 7.Setopati . Domestic medicine market expanding. Available: https://en.setopati.com/market/126366/

- 8.DDA . Drugs act, 2035. Available: https://www.dda.gov.np/content/drugs-act-2035

- 9.Gyanwali P, Humagain BR, Aryal KK, et al. Surveillance of quality of medicines available in the Nepalese market: a study from Kathmandu Valley. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2015;13:233–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poudel RS, Shrestha S, Thapa S, et al. Assessment of primary labeling of medicines manufactured by Nepalese pharmaceutical industries. J Pharm Policy Pract 2018;11:13. 10.1186/s40545-018-0139-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poudel A, Mohamed Ibrahim MI, Mishra P, et al. Assessment of the availability and rationality of unregistered fixed dose drug combinations in Nepal: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Glob Health Res Policy 2017;2:14. 10.1186/s41256-017-0033-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Almuzaini T, Sammons H, Choonara I. Substandard and falsified medicines in the UK: a retrospective review of drug alerts (2001-2011). BMJ Open 2013;3:e002924. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medicine quality in high-income countries: The obstacles. - Google Scholar. Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Medicine+quality+in+high-income+countries%3A+The+obstacles+to+comparative+prevalence+studies&btnG=

- 14.AlQuadeib BT, Alfagih IM, Alnahdi AH, et al. Medicine recalls in Saudi Arabia: a retrospective review of drug alerts (January 2010–January 2019). Futur J Pharm Sci 2020;6:91. 10.1186/s43094-020-00112-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dda: essential drug list. Available: https://www.dda.gov.np/content/essential-drug-list

- 16.Substandard and falsified medical products. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/substandard-and-falsified-medical-products

- 17.WHO . Who global surveillance and monitoring system for substandard and falsified medical products. Available: http://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/publications/gsms-report-sf/en/

- 18.Jha AK. Quality of essential medicines in public health care facilities of Nepal–2019. 1–16, 2019. Available: http://nhrc.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Drug-report.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.FDA . Research, C. for D. E. and. drug recalls, 2019. Available: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/drug-recalls

- 20.Nagaich U, Sadhna D. Drug recall: an incubus for pharmaceutical companies and most serious drug recall of history. Int J Pharm Investig 2015;5:13–19. 10.4103/2230-973X.147222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall K, Stewart T, Chang J, et al. Characteristics of FDA drug recalls: a 30-month analysis. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2016;73:235–40. 10.2146/ajhp150277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shrestha S, Danekhu K, Sapkota B, et al. Herbal pharmacovigilance in Nepal: challenges and recommendations. F1000Res 2020;9:111. 10.12688/f1000research.22133.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO . Who global report on traditional and complementary medicine, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/978924151536

- 24.WHO . Essential medicines. Available: http://www.who.int/medicines/services/essmedicines_def/en/

- 25.Shrestha M, Moles R, Ranjit E, et al. Medicine procurement in hospital pharmacies of Nepal: a qualitative study based on the Basel statements. PLoS One 2018;13:e0191778. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acharya KP, Wilson RT. Antimicrobial resistance in Nepal. Front Med 2019;6:105. 10.3389/fmed.2019.00105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelesidis T, Falagas ME. Substandard/counterfeit antimicrobial drugs. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015;28:443–64. 10.1128/CMR.00072-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rojas-Cortés R. Substandard, falsified and unregistered medicines in Latin America, 2017-2018. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2020;44:e125:1. 10.26633/RPSP.2020.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saraswati K, Sichanh C, Newton PN, et al. Quality of medical products for diabetes management: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001636. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alghannam A, Evans S, Schifano F, et al. A systematic review of counterfeit and substandard medicines in field quality surveys. IPRP 2014;3:71–88. 10.2147/IPRP.S63690 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wertheimer AI, Santella TM. Counterfeit drugs: defining the problem and finding solutions. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2005;4:619–22. 10.1517/14740338.4.4.619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newton PN, Bond KC, 53 signatories from 20 countries . COVID-19 and risks to the supply and quality of tests, drugs, and vaccines. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e754–5. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30136-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ippolito M, Gregoretti C, Cortegiani A, et al. Counterfeit filtering facepiece respirators are posing an additional risk to health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Infect Control 2020;48:853–4. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waffo Tchounga CA, Sacre PY, Ciza P, et al. Composition analysis of falsified chloroquine phosphate samples seized during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2021;194:113761. 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMeekin J. National consumer protection week: FDA is Vigilant in protecting consumers against COVID-19 vaccine Scams. FDA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 36.DDA . Dda: instant hand sanitizer (alcohol based) सम्बन्धि अत्यन्त जरुरी सूचना, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan APL, Chan TYK. Methanol as an Unlisted ingredient in supposedly alcohol-based hand rub can pose serious health risk. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1440. 10.3390/ijerph15071440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashames A, Bhandare R, Zain AlAbdin S, et al. Public perception toward e-commerce of medicines and comparative pharmaceutical quality assessment study of two different products of furosemide tablets from community and illicit online pharmacies. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2019;11:284–91. 10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_66_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fung CH, Woo HE, Asch SM. Controversies and legal issues of prescribing and dispensing medications using the Internet. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:188–94. 10.4065/79.2.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McManus D, Naughton BD. A systematic review of substandard, falsified, unlicensed and unregistered medicine sampling studies: a focus on context, prevalence, and quality. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002393. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mackey TK. Prevalence of substandard and Falsified essential medicines: still an incomplete picture. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e181685. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-053479supp001.pdf (49.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Author compiled and curated raw data will be made available with a reasonable request to corresponding author.