Abstract

Understanding pandemic-related psychopathology development is limited due to numerous individual and contextual factors. It is widely accepted that individual differences to endure or cope with distress predict psychopathology development. The present study investigated the influence of individual differences in neuroticism and healthy emotionality concerning the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems. It was hypothesized that healthy emotionality would moderate the mediated link between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems. A sample of 752 participants (351 males and 401 females) completed an online survey including the Emotional Style Questionnaire, Fear of COVID-19 Scale, the Neuroticism subscale of the Big Five Inventory, and General Health Questionnaire. The results showed that the fear of COVID-19 positively predicted mental health problems (β = .43, SE = .05, p < .001, Cohen’s f 2 = .24). Neuroticism also showed a significant mediation effect on the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems. Fear of COVID-19 indirectly predicted psychopathology through neuroticism (β = − .16, SE = .04, p < .001, t = 4.53, 95% CI [0.11, 0.23]). Moreover, healthy emotionality had a moderating effect on the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems, β = − .21, SE = .03, p < .001, t = 5.91, 95% CI [− 0.26, − 0.14]. The study’s findings are expected to contribute to a better understanding of the roles of both individual differences in personality traits and healthy emotionality in psychopathology development during the current pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Fear of COVID-19, Psychopathology, Emotion regulation, Neuroticism, Resilience

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is much more than a medical challenge. There is also a global mental health emergency with possible long-lasting and profound adverse consequences (Xie et al., 2021). Based on the previous severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus pandemic, survivors reported persistently elevated psychological distress one year after the initial outbreak (Lee et al., 2007). Preliminary psychological research concerning COVID-19 has identified fear (i.e., fear of infection and/or fear of infecting others such as family members) as one of the most common emotional responses during the pandemic for all groups and across genders (Mertens et al. 2020). Fear generated by traumatic events is a major emotion in psychopathology (Tull et al., 2020; Perusini, & Fanselow, 2015).

Fear is conceptualized as an adaptive, evolutionary, and automatic reaction to threat (Craske et al., 2009). Fear generated by the pandemic can be viewed as a motivating factor that facilitates protective behaviors (e.g., following pandemic health instructions) and preventive behaviors (e.g., avoiding unnecessary social activities) among individuals. However, elevated fear increases risk perception and (i) generates subjective experiences of fear in an objective safe context, (ii) provides inaccurate information to the individual, and (iii) generates problematic behaviors (Wu et al., 2021). Extensive fear can lead to elevated health anxiety symptoms, worry-specific phobias, and sleep disturbance (Arpaci et al., 2020; Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2020). However, there is a lack of information regarding the psychopathological mechanisms (e.g., risk factors and protective factors) associated with the fear of COVID-19. It is now widely accepted that personality traits in enduring or coping with stressful challenges are associated with the development or persistence of mental and physical health problems (Zeigler-Hill & Shackelford, 2020).

Neuroticism as mediator

Individual differences in neuroticism predict a broad range of adverse physical and psychological outcomes (Barlow et al., 2014), such as depression (Mineka et al., 2020), anxiety, and somatic symptoms (Strickhouser et al., 2017). COVID-19 psychological distress predicts higher levels of neuroticism (Nazari et al., 2021a). Neuroticism has also been shown to be a strong predictor of internalizing symptomology (Nikčević et al., 2021) and depressive symptoms during the pandemic (Nazari et al, 2022). Moreover, individuals with higher levels of neuroticism are more vulnerable to elevated psychological distress generated by COVID-19 (Lyon et al., 2021). For example, individuals high in neuroticism potentially pay more attention to information about COVID-19 and are anxious more about the consequences of COVID-19 (Kroencke et al., 2020). As a personality trait, neuroticism may shape individual responses through beliefs and attitudes (McCrae & Costa, 2006). The expectancy model of fear (Reiss & McNally, 1985) conceptualizes fear of illness as one of the fundamental fears that are believed to underlie sensitivities to inherently aversive threats and therein represent the vulnerabilities from which fears arise (e.g., fear of flying, fear of hospitals). For instance, fear generated by COVID-19 or catastrophic appraisals related to being infected may lead to mental health problems by elevating negative emotions and dysfunctional beliefs related to health anxiety. Neuroticism is a key trait associated with most emotional disorders (Brown & Barlow, 2009). COVID-19 studies describing the etiological role of neuroticism in psychopathology have proposed similar mediators, such as loneliness (Gubler et al., 2020) and emotional dysregulation (Nazari et al., 2022).

Healthy emotionality as a moderator

The degree to which individuals can regulate emotions involves a complex interplay of affective, cognitive, behavioral, and physiological processes. Healthy emotionality refers to an individual’s overall abilities in adaptive emotional responses. To identify the important components of an individual’s emotional profile, Davidson proposed six dimensions governed by specific brain circuits (Davidson, 1998; Davidson & Begley, 2012). These six dimensions are outlook, resilience, social intuition, self-awareness, sensitivity to context, and attention. For most individuals, each dimension describes a continuum with two extremes (i.e., high and low) and reflects increased or reduced activity in the neural circuits that underlie these dimensions (Davidson & Begley, 2012; Grupe et al., 2018). For most individuals, the type, duration, and intensity of experienced emotions are determined by their unique individual emotional style (Davidson, 1998; Grupe et al., 2018; Kesebir et al., 2019).

Mental health problems refer to conditions that are characterized by cognitive and emotional dysregulations, abnormal behaviors, impaired functioning, or any combination of these. Such problems cannot be accounted for solely by environmental circumstances and may involve physiological, genetic, chemical, social, and other factors (American Psychological Association & VandenBos, 2015). Affective chronometry is particularly germane to understanding individual differences that may reflect mental health problems. Affective chronometry refers to the temporal dynamics involved in emotion to adversity and regulates emotion (Jager, 2016; Kuppens et al., 2009). For example, in unprecedented disasters, resilience alludes to an individual’s capacity to recover from adversity (Feldman, 2020). Positive and adaptive responses that result in a quick recovery after temporary difficulties and help individuals readjust from adversity are associated with positive mental and physical health. Slower recovery from stressful situations predicts greater adverse effects on mental health, such as neuroticism (Schuyler et al., 2014). Outlook denotes the ability to savor pleasant feelings (e.g., positive emotions) over time. There is evidence that short-lived responses to pleasant feelings predict a longer recovery period from negative affect and emotional disorders (e.g., depression; Lapate & Heller, 2020). In turn, higher abilities in self-awareness or individual accuracy in internal bodily cue perceptions play a critical role in somatoform disorders such as health anxiety and cyberchondria during the pandemic (Landi et al., 2020). Sensitivity to context refers to whether an emotional and behavioral response matches the provided social cue. Social cognition and behavior rely on sensitivity to intention and context (Aldao, 2013). Sensitivity to context is a prerequisite for social interaction and learning. This dimension can be considered the outer-directed version of self-awareness. Whereas self-awareness reflects attunement to one’s own physiological and emotional cues, sensitivity to context reflects attunement to the social environment. Contextual sensitivity deficits may provoke maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (Myruski et al., 2017). Social intuition (as ‘evolutionary biological wisdom’) refers to reading nonverbal cues and signals (e.g., body language), which is crucial for facilitating productive interpersonal communication in suspicious situations (Kret et al., 2011). Individuals high on the social intuition dimension are adept at reading nonverbal cues, decoding motives and intentions (e.g., facial expressions, body language, and gestures), and making rapid judgements and attunements to nonverbal social signals based on certain cues (Norman & Price, 2012). Highly socially intuitive individuals may effectively manage their emotions and the impact of emotions in their interactions and infer social information from others’ emotional states (Armstrong et al., 2012). The ability to process nonverbal signals and cues is a prerequisite for establishing productive social interactions. Attention refers to intentional selective attention to positive information. Following stressful events, prolonged or repeated attention to negative aspects of these impairs the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal system, predicts depression and is associated with health problems (Vlachos et al., 2020). Additionally, the inability to disengage attention away from threat plays a significant role in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety disorders. Deficits in cognitive processing abilities may be related to social interaction impairments, which are vital during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Purpose of the present study

The patterns concerning psychological reactions to pandemics are complex, and evidence-based treatments must address such complexity (Holmes et al., 2020). Conceptualizations of coping as an adaptive process have held promise in contributing to the understanding of how individuals are able to deal with adversity and why they sometimes succumb to its pressures. There is a large body of evidence regarding the increase in psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ornell et al., 2020) and the association between psychological distress and the risk of death from infectious diseases (Hamer et al., 2019). Although the negative impacts of the pandemic on mental health are well-documented, much less attention has been given to identifying effective adaptive strategies in the face of adverse situations, particularly among the healthy population (Ben-Ezra et al., 2020). Understanding the factors that can help individuals positively cope with pandemics is critical. Additionally, emotion regulation studies tend to concentrate on the regulation of negative emotional experiences. However, there is evidence that individuals also regulate positive emotions, and the effective regulation of positive emotions is associated with several positive outcomes, such as lower affective disorder vulnerabilities.

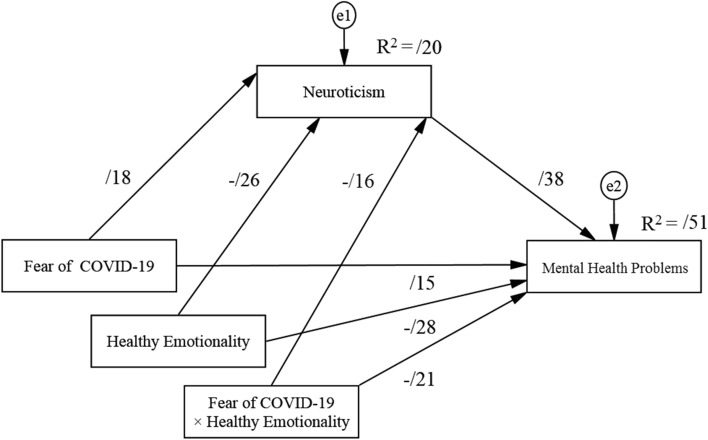

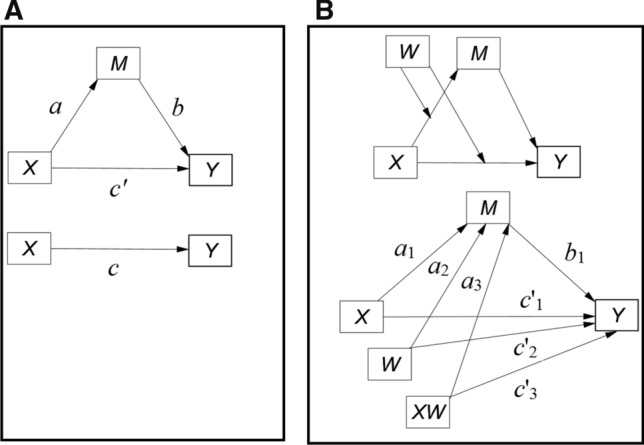

Therefore, the present study investigated the relationship between healthy emotionality (individual differences in emotional style responses), neuroticism, fear of COVID-19, and mental health problems. The proposed model is depicted both statistically and conceptually in Fig. 1. In the present study, it was hypothesized that higher levels of the fear of COVID-19 would be associated with higher levels of mental health problems. It was also investigated whether neuroticism mediated the association between fear generated by COVID-19 and psychopathology among a healthy sample of adults. It was expected that neuroticism would be a predictor of psychopathology. Additionally, it was hypothesized that healthy emotionality would moderate the association between COVID-19-generated fear and neuroticism. It was also hypothesized that healthy emotionality would moderate the mediated link (direct effect) between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems. It was expected that for individuals affected by the psychological distress of the pandemic, a higher healthy emotionality level would be associated with a lower level of neuroticism and with a lower level of mental health problems. More specifically, it was expected that for individuals with higher levels of healthy emotionality, the effect of COVID-19 fear on mental health problems would be lower than that for individuals with lower levels of healthy emotionality.

Fig. 1.

Proposed model depicted as a conceptual model and a statistical diagram. Panel A = mediation model. Panel B = final model for moderating effects of healthy emotionality. X: independent variable (fear of COVID-19). Y: dependent variable (Mental health problems). M: Mediator (neuroticism). WM: Moderator (healthy emotionality). XW: Interaction (fear of COVID-19 × healthy emotionality)

Neuroticism can be potentially relevant for understanding maladaptive behaviors during stressful situations (Strickhouser et al., 2017). Evidence indicates that fears of death and dying in both self and others (family members) have been found to be associated with higher neuroticism levels (Loo, 1984; Zeigler-Hill, & Shackelford, 2020). A recent neuroimaging study suggested that neuroticism was associated with emotion dysregulation (Yang et al., 2020). Additionally, neuroticism is recognized as one of the strongest predictors of reduced resilience (Zager Kocjan et al., 2021). In addition, individuals with higher levels of neuroticism may be more likely to misinterpret the slightest normal bodily sensations as indications of serious disease (Wu et al., 2021). Therefore, high levels of neuroticism appear to negatively affect the ability to cope and to adaptively respond to everyday challenges. Individuals high in neuroticism are more sensitive to the psychological distress generated by the pandemic, such as fear of infection. Therefore, it was hypothesized that the respondents’ healthy emotionality would moderate the strength of the indirect relationship between the fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems via neuroticism in such a way that the mediated relationship (direct effect) is weaker (or stronger) when the respondents’ healthy emotionality is high (or low).

Method

Participants

Data for the present study were collected during a six-week period from October to November 2021 via an online platform (Digital Intelligent Data Collection Company) and social media (Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook). This period coincided with an increase in COVID-19 infection rates in Iran. Eligibility criteria included being (i) aged 18 years or above; (ii) able to read and complete an online consent form and survey; (iii) not being hospitalized or quarantined in the current or past viral pandemics due to a viral infection, or not having (or suspect as having) COVID-19; and (iv) fluent in Persian.

Instruments

Fear of COVID-19

The seven-item Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S), which was originally developed in the Persian language, was used to assess fear of COVID-19 (Ahorsu et al., 2020). Each item (e.g., “My heart races or palpitates when I think about COVID-19”) is rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total raw scores range from 7 to 35, and higher scores indicate greater fear of COVID-19. The scale had very good internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach alpha = 0.83).

Neuroticism

The eight-item Neuroticism subscale of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-44; John et al., 1991; Persian version: Afshar et al., 2015) was used to assess neuroticism. Each item (e.g., “I see myself as someone who: gets nervous easily”) is rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). The total raw scores range from 8 to 40, and higher scores indicate greater levels of neuroticism. The scale had very good internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach alpha = 0.80).

Healthy emotionality

The 24-item Emotional Style Questionnaire (ESQ; Kesebir et al., 2019; Persian version: Nazari & Griffiths, 2020) was used to assess healthy emotionality. The ESQ comprises six dimensions (outlook, resilience, self-awareness, social intuition, sensitivity to context, and attention; four items per dimension), and each item (e.g., “I am sensitive to other people’s emotions”) is rated on a seven-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Total raw scores range from 24 to 168, and higher scores indicate greater healthy emotionality. The scale had very good internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach α = 0.86).

Mental health problems

The 28-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28; Goldberg & Williams, 1978; Persian version: Malakouti et al., 2007) was used to assess the severity of psychopathology in four domains (i.e., depression, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and somatic symptoms) during the past few weeks in the non-psychiatric settings. Each item (e.g., “Have you recently: Been thinking of yourself as a worthless person?”) is rated on a four-point scale (0-0-1-1 system). Total raw scores range from 0 to 28, and higher scores indicate greater levels of mental health problems. The scale has very good internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach alpha = 0.81).

Demographic variables

Participants were asked about their age, gender, and education level. Other socioeconomic status information was not requested. Participants were also asked whether they had COVID-19 or chronic disease, with the following question: Are you currently infected or suspect being infected by COVID-19?

Procedure

Participant recruitment

The study was reviewed and approved by the corresponding author’s university ethics committee. Data were collected online because traditional face-to-face data collection was not possible. Once the link was clicked, it led to an informed consent page to be read and agreed upon by participants before proceeding to the survey. The informed consent page included information about the study goals and objectives, and confidentiality was ensured. In the present study, participants were requested to concentrate on how COVID-19 affected them within the past four weeks when rating survey items. All participants provided digital informed consent.

Sample size

A priori power analysis for structural equation modeling (SEM) was calculated online using an alpha of.05, a power of 0.80, four observed and four latent variables, and two predictors to detect the small effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.2), the minimum sample size required to detect the specified effect, and the minimum sample size required (Westland, 2010). Cohen’s d signifies small effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). The minimum sample size required to detect the specified effect based on these calculations was 342. Additionally, the minimum sample size for the final model structure was 700. In total, 752 participants were recruited in the present study, which allowed for a 10% loss of data.

Data analysis

There were no missing values in the assessed variables, and therefore, no imputation method was implemented. Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were calculated for all continuous variables. Chi-square and independent sample t-tests (i.e., the absolute values) were used to calculate sex differences. The absolute skewness and kurtosis values assessed the normality assumption (Finney and DiStefano, 2013). The multicollinearity issue was evaluated by the variance inflation factor (VIF). VIF values less than 5 indicate the absence of multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2018). Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were generated to calculate the correlations between individual differences in emotional style responses (e.g., resilience, self-awareness), fear of COVID-19, neuroticism, and psychopathology.

A path analysis, using SEM, was carried out to investigate the relationships between fear of COVID-19 (X), neuroticism (M), and mental health problems (Y). In the first step, the simple mediation model was conducted to test whether neuroticism (M) mediated the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and psychopathology. In the second step, healthy emotionality was added to determine whether healthy emotionality moderated both effects of fear generated by COVID-19 on neuroticism and mental health problems. Both interaction effects (fear of COVID-19 × healthy emotionality) on neuroticism and mental health problems were investigated. The direct, indirect, and interaction effects were significant if the calculated 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) did not include zero. The 95% CI was generated by the bias-corrected method for the point estimate with 5,000 bootstrap samples. The effect sizes (Cohen’s f 2) were also generated to provide better insights into the relationships in the models. Cohen’s f 2 ≥ 0.15 and Cohen’s f 2 ≥ 0.35 are considered approximately moderate to large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, 1988). SPSS (version 25, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and AMOS (version 24, IBM) were utilized to test hypotheses with a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 to determine statistical significance.

Results

Table 1 presents an overview of the sample’s demographic characteristics. The sample comprised 752 adults aged 18 to 51 years. The mean age was 32.37 years (SD = 8.42). The participants were well-educated, and significantly more participants had a B.Sc. degree or higher (χ2 = 397, p < 0.01). Compared to males, females had significantly higher fear of COVID-19 scores (t [750] = 2.60, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.29) and neuroticism scores (t [750] = 2.32, p = 0.02, Cohen’s d = 0.19). Compared with females, males had significantly higher scores on healthy emotionality (t [750] = 2.32, p = 0.02, Cohen’s d = 0.19), resilience (t [750] = 2.29, p = 0.02, Cohen’s d = 0.17), and attention (t [750] = 3.05, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.32).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 752)

| Item | Value | Test | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical variables | ||||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Males | 351 (46.7) | χ2 = 3.32 | .07 | |

| Females | 401 (53.3) | |||

| Age, n (%) | ||||

| 18 to 24 years | 257 (34.2) | χ2 = 4.26 | .08 | |

| 24 to 30 years | 295 (39.2) | |||

| Over 30 years | 200(26.6) | |||

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| Primary | 106 (14.2) | χ2 = 397 | < .001 | |

| Higher education | 646 (85.8) | |||

| Continuous variables Mean, SD | ||||

| Age (years) | 32.47 | 8.42 | t(1, 750) = 0.48 | .62 |

| Fear of COVID-19 | 11.90 | 3.97 | t(1, 750) = 2.60 | < .01 |

| Mental health problems | 25.43 | 8.27 | t(1, 750) = 1.93 | .054 |

| Neuroticism | 19.81 | 4.80 | t(1, 750) = 2.31 | .02 |

| Attention | 3.35 | 1.44 | t(1, 750) = 3.05 | < .01 |

| Awareness | 3.72 | 1.75 | t(1, 750) = 1.52 | .16 |

| Outlook | 3.10 | 1..62 | t(1, 750) = 1.83 | .06 |

| Resilience | 3.81 | 1.69 | t(1, 750) = 2.29 | p = .02 |

| Social intuition | 2.53 | 1.28 | t(1, 750) = 1.42 | .15 |

| Context sensitivity | 3.40 | 1.07 | t(1, 750) = 0.39 | .52 |

| Healthy emotionality | 78.50 | 17.09 | t(1, 750) = 2.32 | p = .01 |

n = frequency; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; t = independent t-test to compare gender; the absolute value of the t-statistic is being used

The absolute values of skewness and kurtosis were less than 2. The continuous variable correlational matrix is shown in Table 2. Fear of COVID-19 was negatively correlated with all six dimensions of emotional style responses. Analyses showed a significant negative correlation, although small, between age and fear of COVID-19 (r = − 0.14; p < 0.001). Age was also significantly correlated with healthy emotionality (r = 0.12; p = 0.001), outlook (r = 0.29; p < 0.001), resilience (r = 0.15, p < 0.001) and attention (r = 0.10; p = 0.007). Fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems were negatively correlated with all six dimensions of emotional style responses.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Skewness | Kurtosis | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Fear of COVID-19 Scale | 1.00 | − .32 | − .53 | 1.53 | |||||||||

| 2-Mental health problems | .43** | 1.00 | − .82 | 1.29 | 1.78 | ||||||||

| 3-Neuroticism | .47** | .59** | 1.00 | − .47 | − .40 | 1.30 | |||||||

| 4-Attention | − .41** | − .53** | − .33** | 1.00 | .36 | − .12 | 1.80 | ||||||

| 5-Awareness | − .36** | − .36** | − .45** | .32** | 1.00 | .19 | − 1.53 | 1.95 | |||||

| 6-Outlook | − .14** | − .23** | − .32** | .21** | .39** | 1.00 | − .45 | − 1.77 | 2.23 | ||||

| 7-Resilience | − .20** | − .37** | − .29** | .27** | .35** | .29** | 1.00 | 1.45 | 1.89 | 1.91 | |||

| 8-Social intuition | − .19** | − .21** | − .30** | .20** | .17** | .32** | .13** | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.35 | ||

| 9-Context sensitivity | − .39** | − .31** | − .41** | .39** | .44** | .18** | .29** | .33** | 1.00 | .22 | − 1.20 | 1.92 | |

| 10-Healthy emotionality | − .49** | − .50** | − .36** | .85** | .72** | .48** | .51** | .54** | .70** | 1.00 | − .52 | − 1.99 | 2.79 |

VIF = variance inflation factor

**Correlation significant at the p < .01 level (two-tailed)

Mediation analysis

The simple mediation analysis showed that the total effect of the fear of COVID-19 on psychopathology (path C) was statistically significant, with a medium to large effect size; β = 0.43, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, t = 13.12, 95% CI [0.33, 0.46], Cohen’s f 2 = 0.24. Neuroticism showed a significant mediation effect on the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and psychopathology. Fear of COVID-19 predicted neuroticism (path a). Additionally, neuroticism directly predicted mental health problems (path b), with a large effect size; Cohen’s f 2 = 0.21, 95% CI [0.22, 0.60]. Fear of COVID-19 indirectly predicted psychopathology through neuroticism (path ab), β = 0.16, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, t = 5.53, 95% CI [0.11, 0.23]. The direct effect of the fear of COVID-19 on psychopathology (path C’) was statistically significant, with a small to medium effect size. Therefore, neuroticism partially mediated the association between fear of COVID-19 and psychopathology (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Mediation and Moderation Analysis

| Model | Effect | Path | beta | SE | t-static | LLCI | ULCI | p-value | Cohen’s f 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | |||||||||

| X- > M | a | .33 | .04 | 7.49 | 0.24 | 0.42 | p < .001 | .12 | |

| M—> Y | b | .50 | .05 | 10.31 | 0.41 | 0.59 | p < .001 | .38 | |

| X- > Y | C | .43 | .05 | 11.43 | 0.37 | 0.51 | p < .001 | 0.24 | |

| X- > Y | C’ | .28 | .04 | 6.86 | 0.20 | 0.35 | p < .001 | .11 | |

| X- > M—> Y | ab | .16 | .03 | 5.34 | 0.10 | .022 | |||

| Model B | |||||||||

| X- > M | a1 | .18 | 0.04 | 3.81 | 0.08 | 0.27 | p < .001 | .03 | |

| W- > M | a2 | − .26 | 0.04 | 6.56 | − 0.34 | − 0.19 | p < .001 | .07 | |

| M—> Y | b1 | .38 | 0.05 | 8.03 | 0.29 | 0.47 | p < .001 | .24 | |

| X- > Y | C’1 | .15 | .04 | 3.94 | 0.06 | 0.23 | p < .001 | .04 | |

| W- > Y | C’2 | − .28 | .04 | 6.91 | − 0.36 | − 0.21 | p < .001 | .11 | |

| X × W- > M | a3 | − .16 | 0.04 | 4.53 | − 0.23 | − 0.10 | p < .001 | .05 | |

| X × W- > Y | C’3 | − .21 | .03 | 5.91 | − 0.26 | − 0.14 | p < .001 | .09 | |

| X × W—> M—> Y | a3 b1 | − .06 | 0.02 | 3.68 | − .10 | − .03 | p < .001 | ||

| X- > M—> Y | a1 b1 | .07 | 0.02 | 3.44 | .04 | .11 | P = .001 | ||

| W—> M—> Y | a2 b1 | − .10 | 0.02 | 4.37 | − .15 | − .06 | p < .001 | ||

LLCI = lower-level confidence interval, ULCI = upper-level confidence interval; beta = standardized path coefficient; SE = standard error;

X: independent variable (fear of COVID-19); Y: dependent variable (mental health problems); M: Mediator (neuroticism)

W: Moderator (healthy emotionality); X × W: Interaction (fear of COVID-19 × healthy emotionality); C = total effect;

[ab, a3 b1, a1 b1, a2 b1] = indirect effects

Moderation analysis

The final model is shown in Fig. 2, and the results suggested that the model fitted the data well (χ2/df = 1.00, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.001, 90% CI [0.001, 0.04], with R2=0.51, F [4, 747] = 48.44, p < 0.001). Healthy emotionality was a significant negative predictor of mental health problems; β = -0.28, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, t = 6.91.95% CI [− 0.38, − 0.26], Cohen’s f 2 = 0.18, 95% [0.10, 0.28]. The interaction effect of fear of COVID-19 and healthy emotionality (fear of COVID-19 × healthy emotionality) on neuroticism was statistically significant, β = −0.16, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, t = 4.53, 95% CI [−0.23, −0.10], indicating that healthy emotionality had a moderating effect on the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and neuroticism. Fear of COVID-19 was significantly associated with higher neuroticism for individuals with lower levels of healthy emotionality (mean minus 1 SD); B = 0.46, SE = 0.07, t = 6.46, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.32, 0.60] and average levels of healthy emotionality (mean); B = 0.21, SE = 0.06, t = 3.23 p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.08, 0.33]. However, for individuals with higher (mean plus 1 SD) healthy emotionality scores, the effect of the fear of COVID-19 on neuroticism was not statistically significant; B = 0.04, SE = 0.07, t = 0.51, p = 0.62, 95% CI [−0.11, 0.20].

Fig. 2.

Standardized proposed model for moderating effects of healthy emotionality

Additionally, healthy emotionality moderated the mediated link (direct effect) between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems, with a ∆ R2 = 0.04, F [1, 747] = 46.62, p < 0.001). Fear of COVID-19 was significantly associated with higher mental health problems for individuals with lower levels of healthy emotionality (mean minus 1 SD); B = 0.11, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.08, 0.11] and for individuals with average levels of healthy emotionality (mean); B = 0.05, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.03, 0.07]. However, the effect of the fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems was not statistically significant (B = − 0.01, SE = 0.02, p = 0.61, 95% CI [− 0.04, 0.02]) for individuals with higher (mean plus 1 SD) healthy emotionality scores.

Discussion

Exposure to pandemics, including actual or threatened death, can lead to mental health disorders (Tull & Kimbrel, 2020). Understanding COVID-19 pandemic-related psychopathology development has been limited due to numerous individual and contextual factors. Individual differences in how individuals respond to intense emotional situations can explain why specific individuals are vulnerable to psychopathology development and why others are resilient (Schaefer et al., 2018). The present study investigated the relationship between fear of COVID-19, mental health problems, healthy emotionality, and neuroticism among the general Iranian population. The findings support existing COVID-19 research that a higher fear of COVID-19 is predictive of mental health problems. The study’s findings provide further support for the role of neuroticism, which can be associated with mental health problems (Norton & Paulus, 2017). Additionally, consistent with recent studies (Nudelman et al., 2021; Modersitzki et al., 2020), the present study’s findings indicated that neuroticism was one of the risk factors associated with the mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, healthy emotionality may play a buffering role against the fear of the effect of COVID-19 on mental health problems.

The study’s findings indicated that healthy emotionality moderated the association between fear of COVID-19 and neuroticism. The results indicate that the individual differences in adaptive emotional responses to the fear of the pandemic are associated with mental health problems. Previous research suggests that individuals expect positive outcomes, promote higher savoring, and increase psychological resilience during life-threatening situations (Carver & Scheier, 2014; Fredrickson & Joiner, 2018). A higher outlook ability (e.g., maintaining positive emotions for a longer period, being optimistic) is associated with active coping and regulatory strategies in dealing with stressful life events and can predict mental health problems among both healthy and clinical populations (Lemola et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2018). Persistence of positive emotion may be an effective coping strategy to reduce the risk of depression in traumatic situations in which individuals’ resilience abilities are critical (Nazari & Griffiths, 2020; Laird et al., 2019). For instance, there is evidence that optimism is an effective trait in reducing cyberchondria during the current pandemic (Maftei & Holman, 2020). Positive emotions may contribute to a greater tendency to undertake healthcare behaviors (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2018). Resilience is recognized as a strong negative predictor of psychological distress and COVID-19 anxiety (Nazari et al., 2021a). During the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience promotion has been recognized as a crucial priority to reduce the adverse and traumatic influences of the pandemic on mental health (Bryce et al., 2020; Santarone et al., 2020).

Individual capacity in interoceptive accuracy and awareness of bodily sensations and memories (as well as other types of mental content) play an important role in adaptive emotional responses (Ardelt & Grunwald, 2018). Individuals affected by negative events may be more likely to misinterpret the slightest abnormal bodily sensations as indications of serious disease. Accurate knowledge concerning COVID-19 infection may inhibit an automatic fear response and suppress an initial emotional, bodily fear reaction. Higher self-awareness and contextual awareness enable individuals to clearly identify the triggering of negative responses and can reduce maladaptive cognitive patterns by facilitating awareness/attention toward an object (e.g., increased heartbeat, faster breathing) in a mindful manner (Bonanno et al., 2020; Harvey et al., 2016).

Sensitivity to context is associated with greater flexibility in the use of adaptive or maladaptive coping strategies (Myruski et al., 2017; Yamashita et al., 2016). Fear can be associated with evaluating a low risk or safe situation as uncertain and uncontrollable, driving individuals to perceive such circumstances as more hazardous. Context sensitivity enhances discriminative facility capacity, which refers to the ability to accurately identify controllable from no controllable aspects in a traumatic situation. Deficit insensitivity to context can potentially provoke other maladaptive components of the negative phenotype (e.g., avoidance). Attentional bias toward threat is conceptualized as being reflexive, automatic, and occurring outside of conscious awareness (Wieser & Keil, 2020). Attentional bias toward threat is implicated in interpreting the development and maintenance of fear-related psychopathology presentation (McNally, 2019). Additionally, information processing biases are recognized as critical factors in the psychopathology of anxiety disorders (Rudaizky et al., 2014). According to attentional bias threat theory, individuals with higher fear or anxiety levels exhibit a faster detection threat ability (Bardeen, 2020), which can be helpful in some situations. However, individuals with repeated, prolonged, and/or intensive attentional responses to objectively safe stimuli can experience negative emotions and can be more vulnerable to psychopathologies, such as rumination, distorted perceptions, and negative affect (Cannito et al., 2020; Lee & Zelman, 2019).

The present study also found some sex differences. In line with numerous studies, females reported a higher fear of COVID-19 than males in the present study (Fullana et al., 2020; Nazari et al., 2022). Being older was associated with a higher outlook, greater resilience, increased healthy emotionality, and less fear of COVID-19. In line with the findings, women and younger individuals suffered from negative pandemic consequences more than other groups, as has been reported elsewhere (Fernández et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020). According to social-emotional selectivity theory, older individuals tend to savor positive feelings compared with younger individuals (Carstensen et al, 2003). The study findings align with previous studies indicating that females report greater self-criticism, shame, and psychological problems and are more likely to develop anxiety symptoms and be more neurotic than males (Blüml et al., 2013).

Practical implications

Personality traits have been considered stable and inflexible (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), but growing evidence suggests that neuroticism may be more malleable than originally believed. In the present study, greater fear of COVID-19 was associated with a greater level of neuroticism. Given the high prevalence of anxiety/depressive disorders (Kessler et al., 2005) and various comorbidities (such as anxiety sensitivity) during the current pandemic (Mertens et al., 2020), disorder-specific interventions may be difficult to justify when the clinical reality is complex, and comorbidities are the norm (Holmes et al., 2018). Transdiagnostic interventions based on an emotional style framework can be developed to address temperamental vulnerabilities, in this case neuroticism, associated with comorbidity conditions and can serve as a promising intervention for individuals psychologically affected by the pandemic.

The findings also hold practical implications in intervention design to enhance resiliency. While the resilience constructs are usually oversimplified in clinical settings and research, the dimensions of emotional styles are very relevant in building individuals’ resiliency and to better understand the psychopathology associated with stressful situations (e.g., global disasters). The dynamic processes of positive adaptation to stressful events may offer a practical resilience concept (Kalisch et al., 2017). Moreover, the findings indicate that as healthy emotionality increases, the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems decreases. Compared with individuals with higher levels of healthy emotionality, the negative consequences of fear on mental health problems are more reported by individuals with lower healthy emotionality levels. In the present sample, for individuals with lower ability in overall adaptive emotional responses, higher fear of COVID-19 levels were associated with higher levels of mental health problems. Interestingly, for individuals affected by psychological distresses of the pandemic, an increase in healthy emotionality level may be associated with a significantly reduced risk of mental health problems. A recent study indicated that higher levels (Mean + 1 SD) of adaptive emotional functioning are associated with a reduced rate of anxiety up to 70%, both among healthcare professionals and the general population (Barzilay et al., 2020). Comprehensive and accurate interventions should be used to enhance individual abilities with lower levels of healthy emotionality. Taken together, the findings of the study suggest designing interventions based on all six dimensions of healthy emotionality to promote individual resilience resources.

Emotional style dimensions are both salient and relevant to psychological readiness for the global crisis, which is divided into cognitive and emotional aspects directed at the threat (McLennan et al., 2020; Roudini et al., 2017). In addition to the roles of resilience and outlook in coping with the crisis, the model specifies major dimensions of emotional life, which are each prominently relevant to cognitive aspects (social intuition, attention) and emotional aspects (e.g., self-awareness, sensitivity to context). These affective and cognitive aspects also refer to the emotional intelligence construct, which is conceptualized as individuals’ ability to accurately identify emotion perception in themselves (self-awareness, context sensitivity) and others (social intuition, attention), to regulate emotions and to evaluate and generate an adaptive affective experience (Salovey & Sluyter, 1997). Taken together, the emotional style dimensions can be clinically useful targeted constructs in psychological interventions during the pandemic. Additionally, evaluating individual resources across healthy emotionality components can provide valuable information for healthcare staff (e.g., psychiatrists, psychologists, caregivers) concerning individual psychological states. More specifically, these additional assessments can be helpful to plan personalized psychological treatment programs for individuals affected by pandemic distress but not to the extent that they have a clinical diagnosis. Integrative interventions that comprehensively promote all six dimensions can be implemented in future programs.

Limitations

The present study suffers from limitations—most notably related to the participants and data collection. The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, to minimize infection risk, online data collection was utilized rather than a traditional face-to-face method. This meant that individuals without internet access could not participate. Therefore, the data do not represent these groups’ views and affect the generalizability of the study’s findings. Moreover, the data were self-reported and subject to common method biases. The participants were well-educated and motivated to participate, which could also have affected the study outcomes. It should also be noted that the data collected did not include some potentially important variables, such as whether (1) the participants were currently working or whether they had lost their job as a result of the pandemic, (2) they and/or their family members had experienced COVID-19, and (3) they had financial problems as a result of the pandemic. These are all variables that could be considered in future research when reexamining the variables of this study. Additionally, the study was cross-sectional; therefore, determining directions of causality between the study’s variables cannot be determined. Finally, in addition to being a mediator, neuroticism could have acted as a moderator in the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems. Future studies can be conducted to investigate whether individuals with higher levels of neuroticism will present severe psychopathology, after being exposed to COVID-19.

Conclusion

Despite the wealth of empirical data concerning the association between emotion regulation and mental health problems, much less is known about adaptive emotion regulation abilities most relevant to mental health problems. The findings of the present study indicate that the adverse consequences of the pandemic on mental health problems can be moderated by overall individual abilities in the temporal parameters of emotional style responses. The buffering effect of healthy emotionality can help alleviate the adverse impact of the fear generated by COVID-19 and facilitate good mental health among the general population. The findings of the present study are expected to contribute to a better understanding of the roles of individual differences in personality traits and adaptive emotional functioning responses in psychopathology development during the current pandemic.

Acknowledgements

Education Science “Twelfth Five-year Plan” Provincial General Project of Hunan Provincial Subject (NO.XJKO16CYZ005).

Author contributions

N.Y. was involved in visualization, investigation, and software. N.N. was involved in conceptualization, methodology, and writing–original draft preparation. H.A.V. was involved in methodology, writing–original draft preparation, and supervision. M.D.G. involved in data curation, writing–revision draft preparation, validation, final editing and supervision. All authors were involved in writing–reviewing and editing.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this paper.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this paper.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved and registered by the ethical and research committees from the collaborating centers. The first author’s Institutional Review Board approved the research, prospectively. All participants provided signed written consent.

Footnotes

Editors: Riccardo Brunetti (European University of Rome) / Thomas Alrik Sørensen (Aalborg University); Reviewers: Desiree Blázquez-Rincón (University of Murcia), Marilyn Cyr (New York State Psychiatric Institute).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Afshar H, Roohafza HR, Keshteli AH, Mazaheri M, Feizi A, Adibi P. The association of personality traits and coping styles according to stress level. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20(4):353–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and initial validation. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A. The future of emotion regulation research capturing context. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8(2):155–172. doi: 10.1177/1745691612459518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association, & VandenBos GR (2015) APA dictionary of psychology. American Psychological Association

- Ardelt M, Grunwald S. The Importance of self-reflection and awareness for human development in hard times. Res Hum Dev. 2018;15(3–4):187–199. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2018.1489098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong SJ, van der Heijden BIJM, Sadler-Smith E. Intellectual styles, management of careers, and improved work performance. In: Zhang L-F, Sternberg RJ, Rayner S, editors. Handbook of intellectual styles: Preferences in cognition, learning, and thinking. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Arpaci I, Karataş K, Baloğlu M. The development and initial tests for the psychometric properties of the COVID-19 Phobia Scale ( C19P-S ) Personality Individ Differ. 2020;164:110108. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen JR. The regulatory role of attention in PTSD from an information processing perspective. In: Tull MT, Kimbrel NA, editors. Emotion in posttraumatic stress disorder. Amesterdam: Elsevier Science; 2020. pp. 311–341. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Ellard KK, Sauer-Zavala S, Bullis JR, Carl JR. The origins of neuroticism. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2014;9(5):481–496. doi: 10.1177/1745691614544528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilay R, Moore TM, Greenberg DM, DiDomenico GE, Brown LA, White LK, Gur RE. Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):291. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ezra M, Cary N, Goodwin R (2020) The association between COVID-19 WHO non-recommended behaviors with psychological distress in the UK population: A preliminary study. J Psychiatr Res 130:286–288. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Blüml V, Kapusta ND, Doering S, Brähler E, Wagner B, Kersting A (2013) Personality factors and suicide risk in a representative sample of the German general population. PloS One 8(10):e76646. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bonanno GA, Maccallum F, Malgaroli M, Hou WK. The Context Sensitivity Index (CSI): Measuring the ability to identify the presence and absence of stressor context cues. Assessment. 2020;27(2):261–273. doi: 10.1177/1073191118820131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J, Margraf J. Predicting adaptive and maladaptive responses to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: A prospective longitudinal study. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2020;20(3):183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for assessment and treatment. Psychol Assess. 2009;21(3):256–271. doi: 10.1037/a0016608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce C, Ring P, Ashby S, Wardman JK. Resilience in the face of uncertainty: Early lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J Risk Res. 2020;23(7–8):1–8. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1756379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cannito L, Di Crosta A, Palumbo R, Ceccato I, Anzani S, La Malva P, Di Domenico A. Health anxiety and attentional bias toward virus-related stimuli during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16476. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73599-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Fung HH, Charles ST. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motiv Emot. 2003;27(2):103–123. doi: 10.1023/A:1024569803230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Dispositional optimism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(6):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. London: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Rauch SL, Ursano R, Prenoveau J, Pine DS, Zinbarg RE. What is an anxiety disorder? Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(12):1066–1085. doi: 10.1002/da.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Affective style and affective disorders: Perspectives from affectiveneuroscience. Cognit Emot. 1998;12(3):307–330. doi: 10.1080/026999398379628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Begley S. The emotional life of your brain. New York: Hudson Street Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. What is resilience: An affiliative neuroscience approach. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):132–150. doi: 10.1002/wps.20729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández RS, Crivelli L, Guimet NM, Allegri RF, Pedreira ME. Psychological distress associated with COVID-19 quarantine: Latent profile analysis, outcome prediction and mediation analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney SJ, DiStefano C. Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In: Mueller GR, Hancock RO, editors. Structural equation modeling: A second course. 2. Charlotte NC: Information Age Publishing; 2013. pp. 1269–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Joiner T. Reflections on positive emotions and upward spirals. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018;13(2):194–199. doi: 10.1177/1745691617692106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullana MA, Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Vieta E, Radua J. Coping behaviors associated with decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:80–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupe DW, Schaefer SM, Lapate RC, Schoen AJ, Gresham LK, Mumford JA, Davidson RJ. Behavioral and neural indices of affective coloring for neutral social stimuli. Soc Cognit Affect Neurosci. 2018;13(3):310–320. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsy011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler DA, Makowski LM, Troche SJ, Schlegel K. Loneliness and well-being during the Covid-19 pandemic: associations with personality and emotion regulation. J Happiness Stud. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00326-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis. 8. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M, Kivimaki M, Stamatakis E, Batty GD (2019) Psychological distress and infectious disease mortality in the general population. Brain Behav Immun 76:280–283. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harvey MM, Coifman KG, Ross G, Kleinert D, Giardina P. Contextually appropriate emotional word use predicts adaptive health behavior: Emotion context sensitivity and treatment adherence. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(5):579–589. doi: 10.1177/1359105314532152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, Ghaderi A, Harmer CJ, Ramchandani PG, Cuijpers P, Morrison AP, Roiser JP, Bockting C, O'Connor RC, Shafran R, Moulds ML, Craske MG (2018) The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on psychological treatments research in tomorrow's science. Lancet Psychiatry 5(3):237–286. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30513-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Bullmore E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager G. Short-term time structure of food-related emotions: Measuring dynamics of responses. In: Meiselman HL, editor. Emotion Measurement. City of publication missing: Woodhead Publishing; 2016. pp. 273–298. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. Big five inventory (BFI) [Database record] APA PsycTests. 1991 doi: 10.1037/t07550-000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch R, Baker DG, Basten U, Boks MP, Bonanno GA, Brummelman E, Chmitorz A, Fernàndez G, Fiebach CJ, Galatzer-Levy I, Geuze E, Groppa S, Helmreich I, Hendler T, Hermans EJ, Jovanovic T, Kubiak T, Lieb K, Lutz B, Kleim B. The resilience framework as a strategy to combat stress-related disorders. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1(11):784–790. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesebir P, Gasiorowska A, Goldman R, Hirshberg MJ, Davidson RJ. Emotional style questionnaire: a multidimensional measure of healthy eEmotionality. Psychol Assess. 2019;31(10):1234–1246. doi: 10.1037/pas0000745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(6):593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kret ME, Sinke CBA, de Gelder B. Emotion perception and health. In: Nyklíček I, Vingerhoets A, Zeelenberg M, editors. Emotion regulation and well-being. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 261–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kroencke L, Geukes K, Utesch T, Kuper N, Back MD. Neuroticism and emotional risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Res Pers. 2020;89:104038. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Stouten J, Mesquita B (2009) Individual differences in emotion components and dynamics. Introduction to the Special Issue. Cognit Emot 23(7):1249-58 10.1080/02699930902985605

- Laird KT, Krause B, Funes C, Lavretsky H. Psychobiological factors of resilience and depression in late life. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0424-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi G, Pakenham KI, Boccolini G, Grandi S, Tossani E. Health anxiety and mental health outcome during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: the mediating and moderating roles of psychological flexibility. Front Psychol. 2020;11:2195. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapate RC, Heller AS. Context matters for affective chronometry. Nat Hum Behav. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0860-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SA, Crunk EA. Fear and psychopathology during the COVID-19 crisis: Neuroticism, hypochondriasis, reassurance-seeking, and coronaphobia as fear factors. Omega. 2020 doi: 10.1177/00302228209493500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FKS, Zelman DC. Boredom proneness as a predictor of depression, anxiety and stress: The moderating effects of dispositional mindfulness. Personality Individ Differ. 2019;14:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AM, Wong JGWS, McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Sham PC, Chua SE. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiat. 2007;52(4):233–240. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemola S, Räikkönen K, Gomez V, Allemand M. Optimism and self-esteem are related to sleep. Results from a large community-based sample. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20(4):567–571. doi: 10.1007/s12529-012-9272-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo R. Personality correlates of the fear of death and dying scale. J Clin Psychol. 1984;40:120–122. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198401)40:1<120::AID-JCLP2270400121>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon KA, Elliott R, Ware K, Juhasz G, Brown LJE. Associations between facets and aspects of big five personality and affective disorders: A systematic review and best evidence synthesis. J Affect Disord. 2021;288:175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maftei A, Holman AC. Cyberchondria during the coronavirus pandemic: The effects of neuroticism and optimism. Front Psychol. 2020;11:567345. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakouti SK, Fatollahi P, Mirabzadeh A, Zandi T. Reliability, validity and factor structure of the GHQ-28 used among elderly Iranians. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(4):623–634. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206004522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr . Cross-cultural perspectives on adult personality trait development. In: Mroczek DK, Little TD, editors. Handbook of personality development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- McLennan J, Marques MD, Every D. Conceptualising and measuring psychological preparedness for disaster: The psychological preparedness for disaster threat scale. Nat Hazards. 2020;101(1):297–307. doi: 10.1007/s11069-020-03866-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Attentional bias for threat: Crisis or opportunity? Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;69:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens G, Gerritsen L, Duijndam S, Salemink E, Engelhard IM. Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): Predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;74:102258. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Williams AL, Wolitzky-Taylor K, Vrshek-Schallhorn S, Craske MG, Hammen C, Zinbarg RE. Five-year prospective neuroticism–stress effects on major depressive episodes: Primarily additive effects of the general neuroticism factor and stress. J Abnorm Psychol. 2020;129(6):646–657. doi: 10.1037/abn0000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modersitzki N, Phan LV, Kuper N, Rauthmann JF (2020) Who is impacted? Personality predicts individual differences in psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Soc Psychol Pers Sci 12(6):1110–1130. 10.1177/1948550620952576

- Myruski S, Bonanno GA, Gulyayeva O, Egan LJ, Dennis-Tiwary TA. Neurocognitive assessment of emotional context sensitivity. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2017;17(5):1058–1071. doi: 10.3758/s13415-017-0533-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari N, Griffiths MD. Psychometric validation of the Persian version of the emotional style questionnaire. Curr Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari N, Safitri S, Usak M, Arabmarkadeh A, Griffiths MD. Psychometric Validation of the Indonesian Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Personality Traits Predict the Fear of COVID-19. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00593-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari N, Zekiy AO, Feng LS, Griffiths MD. Psychometric validation of the Persian version of the COVID-19-related psychological distress scale and association with COVID-19 fear, COVID-19 anxiety, optimism, and lack of resilience. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00540-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari N, Sadeghi M, Samusenkov V, Aligholipour A. Factors associated with insomnia among frontline nurses during COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey study. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03690-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Nguyen TT, Nguyen TTP, Nguyen YH, Sørensen K, Pleasant A, Duong TV. Fear of COVID-19 Scale—Associations of its scores with health literacy and health-related behaviors among medical students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4164. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikčević AV, Marino C, Kolubinski DC, Leach D, Spada MM. Modelling the contribution of the Big Five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:578–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman E, Price MC (2012) Social intuition as a form of implicit learning: Sequences of body movements are learned less explicitly than letter sequences. Adv Cogn Psychol 8(2):121–131. 10.2478/v10053-008-0109-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Norton PJ, Paulus DJ. Transdiagnostic models of anxiety disorder: Theoretical and empirical underpinnings. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;56(7):122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudelman G, Kamble SV, Otto K. Can personality traits predict depression during the COVID-19 pandemic? Soc Justice Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11211-021-00369-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornell F, Schuch JB, Sordi AO, Kessler FHP. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: mental health burden and strategies. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42(3):232–235. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perusini JN, Fanselow MS. Neurobehavioral perspectives on the distinction between fear and anxiety. Learn Mem. 2015;22(9):417–425. doi: 10.1101/lm.039180.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, McNally RJ. Expectancy model of fear. In: Reiss S, Bootzin RR, editors. Theoretical issues in behaviour therapy. San Diego: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Roudini J, Khankeh HR, Witruk E. Disaster mental health preparedness in the community: a systematic review study. Health Psychology Open. 2017;4(1):1–12. doi: 10.1177/2055102917711307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudaizky D, Basanovic J, MacLeod C. Biased attentional engagement with, and disengagement from, negative information: independent cognitive pathways to anxiety vulnerability? Cogn Emot. 2014;28(2):245–259. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.815154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Sluyter DJ. What is emotional intelligence? In: Salovey D, Sluyter DJ, editors. Emotional development and emotional intelligence. New York: Basic Books; 1997. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Santarone K, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Preserving mental health and resilience in frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1530–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SM, van Reekum CM, Lapate RC, Heller AS, Grupe DW, Davidson RJ, Davidson RJ. The temporal dynamics of emotional responding: Implications for well-being and health from the MIDUS Neuroscience Project. Oxford Handbook of Integr Health Sci. 2018 doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190676384.013.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler BS, Kral TR, Jacquart J, Burghy CA, Weng HY, Perlman DM, Bachhuber DR, Rosenkranz MA, Maccoon DG, van Reekum CM, Lutz A, Davidson RJ. Temporal dynamics of emotional responding: Amygdala recovery predicts emotional traits. Soc Cognit Affect Neurosci. 2014;9(2):176–181. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickhouser JE, Zell E, Krizan Z. Does personality predict health and well-being? A meta synthesis. Health Psychol. 2017;36(8):797–810. doi: 10.1037/hea0000475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Kimbrel N. Emotion in posttraumatic stress disorder: Etiology, assessment, neurobiology, and treatment. Amesterdam: Elsevier; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachos II, Papageorgiou C, Margariti M. Neurobiological trajectories involving social isolation in PTSD: a systematic review. Brain Sci. 2020;10(3):173. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10030173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Zhao Y, Cheng B, Wang X, Yang X, Chen T, Gong Q. The optimistic brain: Trait optimism mediates the influence of resting-state brain activity and connectivity on anxiety in late adolescence. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39(10):3943–3955. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westland JC. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2010;9(6):476–487. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2010.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wieser MJ, Keil A. Attentional threat biases and their role in anxiety: A neurophysiological perspective. Int J Psychophysiol. 2020;153:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Nazari N, Griffiths MD. Using Fear and Anxiety Related to COVID-19 to Predict Cyberchondria: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(6):e26285. doi: 10.2196/26285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Liu XB, Xu YM, Zhong BL. Understanding the psychiatric symptoms of COVID-19: a meta-analysis of studies assessing psychiatric symptoms in Chinese patients with and survivors of COVID-19 and SARS by using the symptom checklist-90-revised. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):290. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01416-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita Y, Fujimura T, Katahira K, Honda M, Okada M, Okanoya K. Context sensitivity in the detection of changes in facial emotion. Sci Rep. 2016;6:2–9. doi: 10.1038/srep27798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Mao Y, Niu Y, Wei D, Wang X, Qiu J. Individual differences in neuroticism personality trait in emotion regulation. J Affect Disord. 2020;265:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager Kocjan G, Kavčič T, Avsec A. Resilience matters: explaining the association between personality and psychological functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21(1):100198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford TK. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Cham: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.