Abstract

Pythium insidiosum (PI) is an oomycete, a protist belonging to the clade Stramenopila. PI causes vision-threatening keratitis closely mimicking fungal keratitis (FK), hence it is also labeled as “parafungus”. PI keratitis was initially confined to Thailand, USA, China, and Australia, but with growing clinical awareness and improvement in diagnostic modalities, the last decade saw a massive upsurge in numbers with the majority of reports coming from India. In the early 1990s, pythiosis was classified as vascular, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, systemic, and ocular. Clinically, morphologically, and microbiologically, PI keratitis closely resembles severe FK and requires a high index of clinical suspicion for diagnosis. The clinical features such as reticular dot infiltrate, tentacular projections, peripheral thinning with guttering, and rapid limbal spread distinguish it from other microorganisms. Routine smearing with Gram and KOH stain reveals perpendicular septate/aseptate hyphae, which closely mimic fungi and make the diagnosis cumbersome. The definitive diagnosis is the presence of dull grey/brown refractile colonies along with zoospore formation upon culture by leaf induction method. However, culture is time-consuming, and currently polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method is the gold standard. The value of other diagnostic modalities such as confocal microscopy and immunohistopathological assays is limited due to cost, non-availability, and limited diagnostic accuracy. PI keratitis is a relatively rare disease without established treatment protocols. Because of its resemblance to fungus, it was earlier treated with antifungals but with an improved understanding of its cell wall structure and absence of ergosterol, this is no longer recommended. Currently, antibacterials have shown promising results. Therapeutic keratoplasty with good margin (1 mm) is mandated for non-resolving cases and corneal perforation. In this review, we have deliberated on the evolution of PI keratitis, covered all the recently available literature, described our current understanding of the diagnosis and treatment, and the potential future diagnostic and management options for PI keratitis.

Keywords: Pythiuminsidiosum, Keratitis, Parafungus, Zoospore, Leaf incarnation method, Linezolid, Azithromycin, Therapeutic keratoplasty

Key Summary Points

| Pythium insidiosum is an oomycete causing vision-threatening keratitis in humans. |

| Presumptive assumption by the clinician and the microbiologist that they are dealing with a fungus can delay early diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment. |

| Recent literature supports growing evidence for the use of antibacterials (linezolid and azithromycin) as the first-line drugs. |

| Due to high virulence, rapid proliferation, and early recurrence, early therapeutic keratoplasty with 1-mm margin clearance is recommended. |

Introduction

The genus Pythium embraces 200 species. They are one of the most destructive plant pathogens, infecting crops and destroying the seeds, storage organs, roots, and other plant tissues [1]. The genus was considered as true fungi by Pringsheim in 1858 due to characteristics including eukaryotes with filamentous growth, absence of septa, nutrition by absorption, and reproduction via spores [2]. However, as the understanding of evolution has developed, the Pythium species are now being classified as protozoan, as they have cellulose, beta-glucans, and hydroxyproline in their cell walls [2]. The only species of Pythium known to cause keratitis in humans is Pythium insidiosum (PI) [3], which was described as an emerging phytopathogen causing infections in animals and humans in 1884 [4]. Virgile et al. made the first report of a corneal ulcer in a 31-year-old woman caused by PI in 1993. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with sickle cell trait [3]. Since then, 168 ocular pythiosis cases have been reported in the literature until 2021 [5]. PI keratitis has been sparsely reported due to varied reasons such as lack of knowledge about the microscopic and colony morphology of the organisms among the microbiologists, falsely labeling it as an unidentified fungus, absence of growth in the culture, lack of high clinical suspicion among the clinicians, delayed diagnosis, and its clinical resemblance to fungus [6]. The common systemic and ocular risk factors identified for Pythium infection are thalassemias, sickle cell trait, swimming with contact lenses, exposure to farm animals, and swampy areas [7]. Recently, a few studies from South India reported a higher incidence of PI keratitis in homemakers and IT professionals [8, 9].

Early diagnosis and prompt differentiation from fungal keratitis (FK) are imperative for immediate initiation of appropriate treatment for Pythium to yield a good prognosis [7]. The direct microscopic examination of smears with Gram staining and KOH mount, on the cursory look, may resemble fungal filaments. The sensitivity ranges from 79.3 to 96.5% [8]. Still, the microbiologist's familiarity with the typical appearance of Pythium filaments, which appear as broad, ribbon-like filaments with right angle branches, would help in the early identification of the infection [9]. The confirmatory test is the cultural identification with zoospore formation but it takes 5–7 days, which may significantly delay the initiation of treatment for Pythium [8, 10, 11]. The time to identification can be minimized if the clinician and microbiologist are experienced and suspect Pythium. Agarwal et al. had used confocal microscopy to rapidly identify and define the typical confocal features of Pythium in the stroma; they appear as multiple, linear, hyper-reflective, well-delineated structures with a width of 4 μm and length of 350 μm seen in all the layers of the cornea with occasional branching and intersecting angles at 78.6° [12]. Though it has a 95% sensitivity, it cannot differentiate PI from other FK [12, 13]. Serodiagnosis to detect antibodies against P. insidiosum, immunofluorescence, or immunoperoxidase staining assays can assist in diagnosis if a high index of clinical intuition is present [9]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is considered the gold standard in the diagnosis of Pythium. It is crucial to understand the recent diagnostic modalities for prompt identification of the PI, with high specificity and sensitivity for the expeditious management [14]. Previously, therapeutic keratoplasty remained the terminal option to reduce the microbial load to salvage the eye and invariably 90% of the keratitis ended up with evisceration [15]. Recently, several authors have reported in vitro susceptibility of various strains to antibacterial such as tigecycline, macrolides, tetracyclines, and linezolid both as monotherapy and in combination with antifungal agents [10, 11, 14, 16–18].

However, with better understanding of its morphology, clinical features, and response to antibacterial agents along with the development of adjunctive treatment methods, the prognosis and outcomes have significantly improved [16–18]. This review article discusses the entire evolution of our understanding of PI keratitis concerning its morphology, clinical features, laboratory diagnosis, and management in detail along with a futuristic perspective on the way forward. This work is based on previously conducted studies, and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Method of Literature Search

A detailed systematic literature search was performed of the PubMed, Google Scholar, ePub publications, and Cochrane Library database for all the recent case reports, series, original articles, review articles, and clinical trials on PI keratitis. The literature search was performed using the keywords Pythium insidiosum, Pythium insidiosum keratitis, Pythium keratitis, Pythium AND (Zoospore) AND (antifungals) AND (antibacterials) AND (review) AND (diagnosis) AND (treatment). Articles in languages other than English were also reviewed. All the relevant articles were compiled and reviewed for relevant literature.

Epidemiology

Pythium insidiosum keratitis is reported commonly in tropical, subtropical, and temperate climates [10]. The first case of ocular pythiosis came into existence in 1988 from Thailand. Since then, there have been numerous reports from different countries, viz. Australia, Israel, China, Japan, Malaysia, India, etc. [7]. As per detailed literature review, the reported incidence and prevalence of PI keratitis is variable, which is probably due to the rarity of microorganisms and regional and geographical variations. Das et al. reported in their analysis of keratitis in COVID-19 period reported it to be a rare cause of keratitis compared to FK [19]. Hasika et al. reported a prevalence of 5.9% (71/1204) of PI keratitis from South India [15]. Vishwakarma et al. in their analysis reported a higher male preponderance and greater prevalence among agricultural workers of lower socio-economic strata [20]. Sharma et al. reported a prevalence of 5.5% (9/162) in phase 1 and 3.9% (4/102) in phase 2 of PI keratitis as an etiological agent of FK [11]. A higher incidence of PI has been reported in patients with thalassemia, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), chronic arterial insufficiency and patients with thrombosis, aneurysms, and vasculitis [7]. Hence, a high index of clinical suspicion is necessary among clinicians to diagnose the vision-threatening keratitis [21].

Clinical Features

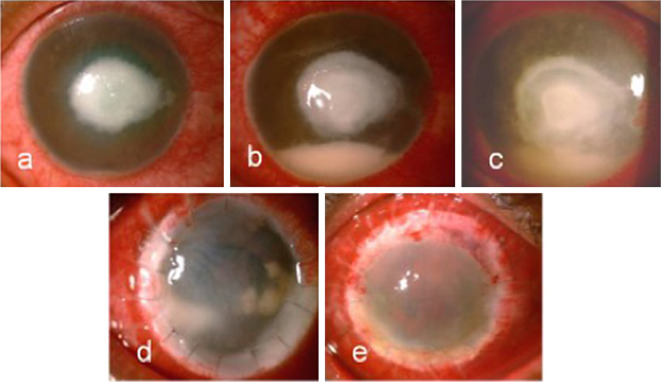

Clinical features of PI keratitis can be highly variable, which makes the diagnosis challenging. Similar to FK, the corneal surface overlying the infection is described as "dry" without the significant suppuration or purulence that is associated with bacterial keratitis [16]. PI keratitis can present with several patterns of infiltration. Across several case series, the most common presentation described is a dense, full-thickness stromal infiltrate in the central cornea with associated radiations of tentacle-like, wispy, reticular infiltrates in the subepithelial layer or the anterior corneal stroma [12, 16, 22–25]. Despite being distinctive, these radiating reticular infiltrates are neither pathognomonic nor present in all cases [11]. PI keratitis can also present with a large central infiltrate associated with multiple smaller discrete satellite infiltrates with intervening gaps of the clear cornea [11, 16, 24]; multifocal infiltrates scattered across the cornea [11, 16]; punctate miliary subepithelial lesions [10, 17]; or a large, dense infiltrate occupying most of the cornea [16, 24, 25]. Infiltrates often have feathery or non-discrete edges, similar to FK [17]. Other non-specific findings, including ring infiltrates [26], keratoneuritis [23], keratic precipitates [26], endothelial plaque [10, 27], and peripheral corneal thinning [10], have also been reported. Hypopyon has been commonly reported, particularly in severe cases [11, 12, 22, 25, 27]. In severe cases, the infection can extend to the limbus, sclera, and anterior chamber [10, 25] or progress to corneal melt or perforation (Fig. 1) [10, 15].

Fig. 1.

Digital image of a patient with rapidly proliferative Pythium insidiosum keratitis. a At presentation (day 1)—5 × 6 mm central full-thickness infiltrate with trace hypopyon. b, c (day 7) Worsening of full-thickness infiltrate with rapid spread towards limbus and increase size and density of hypopyon despite topical medications. d Recurrence-graft infection noted 7 days following therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty, e 1 month following a regraft-diffuse congestion, stromal edema, and 360-degree superficial vascularization

PI keratitis can most easily be misdiagnosed as FK [11, 28] due to similar clinical features, including a “dry” corneal surface and feathery infiltrates with indistinct edges, multifocal infiltrates, and lack of response to the usual antibacterial therapy. Both Pythium and FK occur more commonly among young, working-age adults with exposure to vegetable matter [10] or natural bodies of water [23, 25]. FK in developing countries classically occurs in farmers and day laborers, while multiple case series report PI keratitis in white-collar workers with no discernable exposure to plant or vegetable matter [10, 23]. Clinicians, therefore, should maintain a high index of suspicion for Pythium in cases of culture-negative or smear-negative presumed FK cases that fail to respond to empiric antifungal treatment [23]; atypical-appearing keratitis that occurs following exposure to natural bodies of water, particularly in tropical settings such as Thailand or India; and the appearance of distinctive reticular or tentacle-like superficial infiltrates suggestive of PI infection.

Acanthamoeba keratitis can also share features with PI keratitis, including ring infiltrates [26], multifocal infiltrates [16, 24], and keratoneuritis [23]. Although Acanthamoeba keratitis is most commonly seen in contact lens wearers [29], and PI keratitis is most strongly associated with exposure to natural water, there can be overlap in risk factors. Acanthamoeba is a free-living protist found particularly in aquatic environments and can cause keratitis in non-contact lens wearers, particularly in India, where the leading risk factor is exposure to vegetable matter [30, 31]. PI keratitis has been reported in contact lens wearers [23], typically after exposure to natural water [27]. Co-infection with Pythium and Acanthamoeba has also been reported [29]. To improve the diagnosis of PI keratitis, treating clinicians should maintain an open mind about the etiology of any presumed microbial keratitis that is failing to respond to empiric antimicrobial therapy. Repeat smears, molecular testing such as PCR, and/or biopsy with appropriate stains and culture should be strongly considered in such cases. A summary of the clinical features of PI keratitis and its differential diagnoses is given in Table 1 [7–12, 15, 17, 29, 32, 33].

Table 1.

Classical clinical features of Pythium insidiosum keratitis and resemblance to other keratitis

| Serial number | Pathogen | Risk factor | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pythium insidiosum keratitis [7–12] (Hallmark features) | Dust fall, pond water, swimming pool, stick injury, clay injury, vegetative trauma | Pinhead-size lesions, reticular dot infiltrates, stromal infiltrates with hyphated edges, tentacles, multifocal infiltrate, peripheral furrowing, guttering, early limbal spread, and rapid corneal melt |

| Clinical features resembling other keratitis* | |||

| 1 | Bacterial (Gram-positive and negative) keratitis [33] | Insect fall, exposure due to lagophthalmos, blunt trauma, steroids, contact lens | Purulent discharge, mated lashes, epithelial defect, stromal infiltrate, corneal melt, dense white cheesy suppuration, corneal abscess, endo-exudates, hypopyon, and perforation |

| 2 | Fungal (filamentous and non-filamentous) keratitis [7–11, 15] | Vegetative matter injury, steroids, sand injury, alcohol intake, surgery | Epithelial defect, subepithelial, stromal or full-thickness infiltrate with feathery margins, corneal abscess, ring infiltrate, satellite lesions, endo-exudates, hypopyon, perforation, gradual limbal involvement |

| 3 | Atypical mycobacterial keratitis [17] | Post refractive surgery, incidental trauma, steroid-induced, contact lens | Epithelial defect, dry greyish-white stromal infiltrate and edema, Descemet folds, cracked- windshield appearance |

| 4 | Acanthamoeba keratitis [29] | Contact lens (West), bath in pond water, and contaminated water (India) | Satellite lesions, focal pinhead-size infiltrates, ring infiltrates, stromal infiltrates, radial keratoneuritis |

| 5 | Peripheral ulcerative keratitis [32] | Connective tissue disease, idiopathic | Peripheral thinning and guttering, crescent-shaped stromal infiltrate stromal cellular reaction and edema. stromal melt, corneal perforation |

All these clinical features can be seen in Pythium insidiosum keratitis besides the hallmark features listed above

Microbiological Laboratory Diagnosis

The General Approach to Lab Diagnosis

PI keratitis, as we understand it, is relatively rare. Still, clinicians and microbiologists should always have a high suspicion index whenever dealing with atypical microbial keratitis, as missing the diagnosis usually relates to poorer outcomes [32]. Clinicians should ideally not rule out Pythium based on one form of testing alone until attaining a satisfactory clinical endpoint, as it may require multiple and/or different types of specimens ranging from a corneal scrape, corneal biopsy, corneal button to eviscerated tissue to establish the diagnosis [15, 34]. In general, any specimen requiring testing for Pythium growth should be stored between 28 and 37 °C [35]. Culture positivity with zoospore induction gives a definitive diagnosis but still PCR (polymerase chain reaction) is the gold standard due to high sensitivity and specificity. It is also vital to understand all the existing and evolving modes of lab diagnosis [36].

Direct Staining/Examination

Corneal scrapings collected under aseptic precautions can be directly stained and studied under a microscope. 'Broad sparsely septate ribbon-like hyaline filaments' is the typical description of Pythium [7]. They can also exhibit collapsed walls and vesicular expansion [37]. In contrast, fungal hyphae are broad sparsely septate with branching at various angles. While it is generally considered difficult to differentiate Pythium from fungal filaments, newer stains are helping improve the diagnostic ability of this technique. Various stains have been reported in different studies, including Gram, 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH), Calcofluor-White (CFW) [37], Acridine Orange [38], Lactophenol cotton blue (LPCB), Trypan blue, and potassium iodide-sulfuric acid (IKI-H2SO4) [9].

A combination of 10% KOH-CFW staining has been shown to have a sensitivity between 79.3 and 96.5% and over 93% specificity in detecting Pythium [37]. This requires a fluorescence microscope and microbiologist to study images. Trypan blue is an easily available stain that can be used by ophthalmologists and directly studied without any special microscope. This technique has a sensitivity of over 75% and specificity of 68% [39, 40]. IKI-H2SO4 stain is a recent addition that specifically stains Pythium, but not fungal filaments, and different studies show a specificity close to 100% [9, 41]. The sensitivity and specificity of various stains is with respect to culture results of PI keratitis. One or different combinations of the above, along with a trained eye and clinical suspicion, can help in the early detection of PI keratitis. In vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) has been shown to demonstrate hyperreflective beaded string-like branching structures, but they cannot differentiate Pythium from fungus or Nocardia [36, 42].

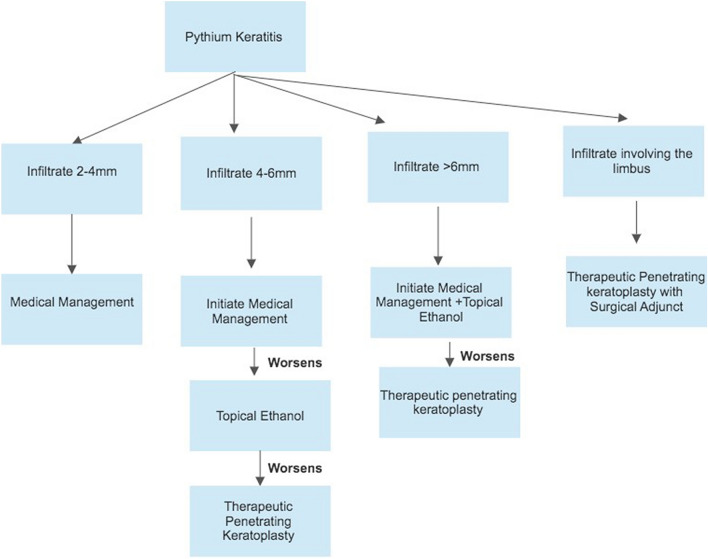

Culture

Pythium has been described to grow as a flat colorless or light brown colony with fine radiations in the edges [7, 36]. Culture can be obtained either from scraping or inoculation from the corneal button into blood agar, potato dextrose agar (PDA), or Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA). PI will grow on most commonly used bacterial, fungal, and amoebic agars (Fig. 2a–c). Grass leaves with water culture has been shown to induce zoospore formation, which is confirmatory for P. insidiosum (Fig. 2d) [11, 36]. The above process can be time-consuming (up to 11 days) and significantly delay the initiation of appropriate pharmacotherapy. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) is a novel technique that has been shown to rapidly identify Pythium species in the very early stages of culture. This could be used for very early detection of Pythium from culture plates with accuracy [43].

Fig. 2.

Digital culture images of Pythium insidiosum keratitis. a 5% sheep blood agar image depicting flat, gray-white colony at 37° (2nd day). b Dense cream-colored colony of Pythium on 5% sheep blood agar at 37° after 5 days. c White submerged colony on chocolate agar after 2 days. d Magnified view (× 10) of a small vesicle with numerous zoospore formation after 3 h of incubation using leaf incarnation method

Histopathological Examination (HPE)

HPE of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded corneal buttons excised during therapeutic keratoplasty (TPK) or eviscerated specimen is possible with the help of different stains such as H&E (hematoxylin-eosin stain), periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), and Gömöri methenamine silver (GMS) [7, 9]. This test is typically done at later stages of the disease but can help in confirming the diagnosis. IKI-H2SO4 stain typically stains Pythium but not fungal filaments and has 100% specificity, which is better than PAS or GMS stains [9].

Serology-Based Tests

Serology-based tests detect antigens or antibodies, and tests like hemagglutination (HA), ELISA, immunochromatography (ICT), and immunodiffusion (ID) are available for the detection of pythiosis [44–47]. Immunoperoxidase staining assay, ELISA, and ICT have high sensitivity and specificity [47, 48]. Overall, they have good utility in systemic pythiosis but not in keratitis, as there is usually no significant systemic antibody response in keratitis.

Molecular (PCR-Based) Tests

Apart from positive culture with zoospore formation, PCR tests are the only gold standard, as they typically identify species-specific sequences of the DNA [11, 36]. PCR can either be performed as a rapid test from a corneal scraping or the growth on a culture plate. rDNA-ITS (internal transcribed spacer) regions are usually targeted [49, 50]. PCR for Pythium detection has rapidly evolved. The initial nested PCR had a sensitivity of around 90% with 80% specificity [51]. Duplex PCR targeting 18S rRNA and ITS showed 100% specificity but 91% sensitivity [49]. The newer LAMP (loop-mediated isothermal amplification) PCR technique has 100% sensitivity and 98% specificity [52]. Real-time PCR targeting a protein exo-1, 3-beta-glucanase is a novel value addition with 100% sensitivity and specificity apart from a shortened turnaround time of 7.5 h [14]. While the above targets are used for clinical testing, PCR for targets like cox-II, ELI025, exo-1,3-β-glucanase gene, and other techniques like AFLP (amplified fragment length polymorphism) are being used for population studies of Pythium [53–58].

Imaging

Imprecise and delayed diagnosis based on different staining techniques, cultures, and zoospore identification has necessitated the need to look for alternatives. Serological tests using antibodies have facilitated the diagnosis of systemic pythiosis, but its role in ocular infection is limited [50]. The use of in vivo confocal microscopy has also been described to diagnose PI; however, the features are not characteristic or specific and cannot be used to distinguish from fungi. They appear as beaded, thin hyperreflective branching structures with a mean branching angle of 78.6° and varying from 90 to 400 μm in length [42]. Nevertheless, confocal microscopy does have a role in detecting an early recurrence [14]. The use of immunoperoxidase staining using P. insidiosum antibodies through various sources has been reported to have higher sensitivity and specificity than the routine histopathological stains; however, Kosirurkvongs et al. compared nested PCR with culture and immunostaining and found PCR to be the most sensitive [48, 59]. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) is a recent tool for identification that is based on crude proteins generating a main spectral profile (MSP) which is then searched against a reference database for P. insidiosum [43, 60].

Treatment

Increased awareness, improved understanding of the pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and microbiological features have facilitated relatively faster diagnosis, however, management of PI keratitis still poses multiple challenges [61]. Presently, there is no gold standard treatment for PI keratitis, and with the lack of standardized antimicrobial susceptibility testing for oomycetes, choosing an appropriate antimicrobial also becomes difficult [7]. Based on broth microdilution, Etest, and disk diffusion methods following the CLSI guidelines, in vitro studies have shown tigecycline, minocycline, azithromycin, and clarithromycin to be effective as compared to antifungals [62, 63]. The lack of ergosterol in the Pythium cell wall, which is the leading site of action of all antifungals, is the primary reason for its lack of response. The Pythium cell wall primarily comprises cellulose, chitin, and small amounts of beta-glucan. Caspofungin, which inhibits beta-glucan synthase, was more effective than other echinocandins. However, the effect was only static, and thus its use was not very encouraging [64].

Loreto et al. found azithromycin to be superior to linezolid; however, Bagga et al., in their in vitro and animal studies, have found linezolid to be more effective [63, 65]. The diversity in the susceptibility techniques and the concentration of spores used possibly explain the diversity for MIC obtained for P. insidiosum. Inhibition of protein synthesis by these antibacterial agents has been considered the possible mechanism of action for inhibiting Pythium. However, bacteria are prokaryotes with 70S ribosomes with 30S and 50S subunits, whereas Pythium, like humans, are eukaryotes that possess 80S ribosomes with 60S and 40S subunits. Both linezolid and azithromycin act on the 50S ribosome unit, prevent protein synthesis, and thus act as antibacterials [66, 67]. This is in fact one of the critical factors that reduce its toxicity in humans, as it does not affect the 80S ribosome, thus raising doubts about their exact mechanism of action in inhibiting Pythium.

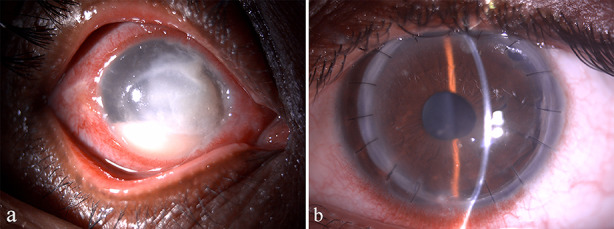

Recently, in a series of 69 eyes, 55.1% resolved with medical treatment, with 34.3% requiring cyanoacrylate glue for tectonic support, with the median duration of treatment being 3 months. The remaining 44.9% required a therapeutic graft. On comparing the characteristic features, eyes with infiltrates > 6 mm, longer duration, and posterior stromal involvement did not respond to medical therapy being constituted by a combination of topical linezolid, azithromycin, and oral azithromycin. The authors recommend initiating medical treatment in mild-to-moderate cases, and therapeutic keratoplasty (TPK) can be planned based on the treatment [68]. In another series of 18 eyes from Eastern India, all seven eyes where medical therapy was initiated ended up requiring a therapeutic graft or were eviscerated [28]. Among 30 eyes reported by Gurnani et al., seven (23.3%) responded to topical azithromycin and linezolid with oral azithromycin, whereas 19 eyes (63.3%) required surgical intervention. They also concluded that patients with mild-to-moderate ulcer severity with a size less than 4 mm, only anterior one-third stromal involvement, and fewer tentacular projections, respond to medical therapy. Among the 19 eyes which underwent a TPK, recurrence was noted in 20%, requiring a repeat graft [9]. Oral azithromycin can cause nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or stomach upset, but none has been reported by any studies. A higher incidence of recurrence in the range of 46–54.2% following TPK, even necessitating evisceration, has been a major concern in most published series [15, 24]. To reduce this incidence, a larger graft with at least 1 mm of clear margins instead of 0.5 mm is routinely indicated, including the radiating reticular pattern in the cornea within the keratoplasty (Fig. 3). Delay in presentation and diagnosis are the important parameters which govern the spread of PI to the limbus, sclera, and the presence of non-resolving anterior chamber exudates, although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact percentage or number of cases developing this picture. Moreover, once the organism has spread to the limbus, rapid scleral involvement is seen, and it becomes too difficult to contain the infection even after an aggressive keratoplasty. Full-thickness large ulcers involving the visual axis need an early keratoplasty after 7–10 days to obtain a good anatomical and functional outcome.

Fig. 3.

Digital image of a patient of Pythium insidiosum keratitis. a Depicting 6 × 8 mm full-thickness infiltrate with subepithelial infiltrates radiating up to the limbus. b No recurrence noted 2 weeks after therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty taking 1 mm larger host margin with intraoperative cryotherapy and alcohol

Agarwal et al. proposed using surgical adjuncts like cryotherapy and ethanol in grafts involving the limbus to reduce recurrence further. The actual spread of the organism into the limbus and the adjacent sclera becomes difficult to distinguish clinically until active necrosis sets in, contributing to the increased risk of recurrence. The surgical adjuncts, both cryotherapy, and ethanol, aid in reducing recurrence following a therapeutic graft by addressing this clinically unidentifiable spread when the limbus is involved [12]. In their series of 46 eyes, recurrence rates of 100, 51.8, and 7.1% were noted in eyes that received medical treatment, therapeutic keratoplasty alone, and TPK with surgical adjuncts, respectively. A single freeze–thaw cryotherapy using a nitrous oxide probe is recommended at the limbus, and in cases with infiltration extends 3–4 mm beyond the graft–host junction, ethanol with multiple rows of cryotherapy is used to prevent recurrence [25].

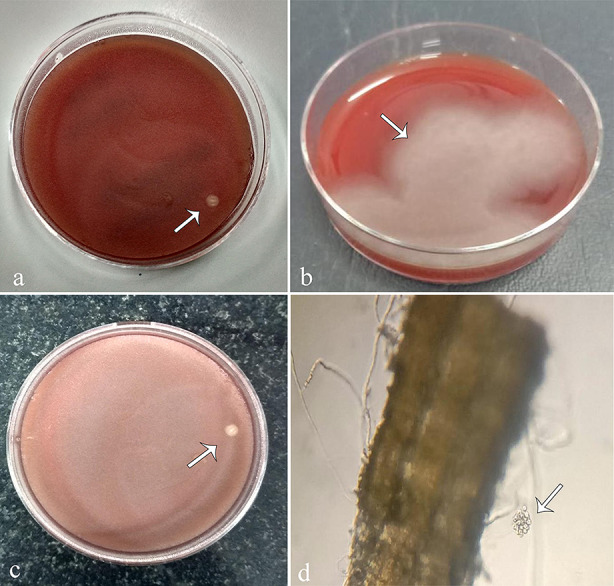

Based on their initial success with ethanol, Agarwal et al. explored the efficacy of using topical ethanol to treat PI. They performed microbiological, clinical, and histopathological studies to analyze the effect of absolute ethanol on P. insidiosum along with infrared spectroscopy to assess the corneal penetration and concluded that it could be considered as a therapeutic option; however, the exact dose and strength of ethanol at which it will be most effective still needs to be explored [69]. Ethanol is known to decrease the viability of cells by causing cell lysis, suppressing proliferation, and inducing apoptosis. It primarily acts on the cell membranes, and the lack of ergosterol in the cell wall of Pythium makes it more susceptible to ethanol even at lower concentrations. Based on the reports available in the literature and the author's own experience managing PI keratitis, we propose a treatment algorithm taking the size of infiltrate at presentation as the determinant (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Image depicting the proposed management algorithm for Pythium insidiosum keratitis

Future Directions

Management of PI keratitis is challenging, and still relies on surgical technique to be the most favorable. Multiple drugs, drug combinations, natural extracts, natural compounds, bacterial isolates, substances like biogenic silver nanoparticles, copper acetate, and drugs like miltefosine have shown anti-P. insidiosum effects but need to be explored clinically [62, 70]. Xanthyletin, a natural compound of green plants, is a coumarin derivative and was found to have anti-Pythium effects by probably affecting the protein composition of the cell wall or cell membrane [71]. The presence of cellulose in the Pythium cell wall, similar to acanthamoeba cyst, makes it resilient in nature [72]. Although chemically homogenous, cellulose exists in crystalline and amorphous topologies, and there is no single enzyme that can hydrolyze it. The insoluble, crystalline, and heterogeneous nature makes it a resilient and challenging substrate for enzyme hydrolysis. Streptomyces species are being used as a biocontrol agent against Pythium species and are shown to produce enzymes that cause cell wall rupture. S. rubrolavendulae S4 was reported to have a very high cellulase activity and inhibit Pythium growth [73]. Understanding the cellulose structure and arrangement of fibers in the Pythium cell wall will help discover the most effective combination of cellulases that can disrupt the Pythium cell wall. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is being explored to treat refractory infections, especially due to increasing antimicrobial resistance. The photosensitizer and the light interaction produce reactive oxygen species, which are highly toxic to cells. PDT using methylene blue, Photogem®, and Photodithazine® was evaluated, and all were found to have inhibition rates of more than 50% but regrowth was observed within 7 days. The three dyes' penetration varied, and Photodithiazine® showed maximum efficacy due to higher cell wall penetration and concentration in membranes [74].

Pythium has a very different cell wall structure as compared to other microorganisms. The presence of cellulose makes the drug penetration and action a challenge [75]. An improved understanding of the cell wall structure and organization will further open new avenues to be explored in managing this refractory organism. A summary of review of literature of all the clinical studies and case reports or PI keratitis is listed in Table 2 [3, 8, 10, 12, 15–19, 22–29, 32–34, 38, 68, 75–85].

Table 2.

Review of literature of clinical studies and case reports of Pythium insidiosum keratitis

| S. no. | Authors | Country | Demography | Risk factors | Clinical features | Investigations | Management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roy et al. [74] | India | 42-year-old male | COVID-19 (35 days after COVID-19) | Left eye had corneal ring infiltrate (4 × 4 mm), vision 20/60 | Corneal scraping | Medical management | Resolved in 14 days |

| 2 | Hou et al. [75] | China |

1: 45-year-old female 2: 51-year-old female, and 55-year-old male |

1, 3: Exposure to river water 2: Exposure to cigarette ash |

1: Corneal ulcer (ring infiltrate) 2, 3: Corneal stromal infiltrate 3: received diagnosis of viral keratitis, had keratoneuritis mimicking Acanthamoeba |

1: Corneal scraping, confocal microscopy, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing with pan fungal primers (ITS1/ITS4) 2: Corneal scraping, Gram staining, KOH, culture, potato dextrose agar (PDA), Subculture in the brain–heart infusion, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) 3: Cultured on PDA plate and confirmed by MALDI-TOF-MS |

1: Keratectomy, lamellar keratoplasty, intracameral fluconazole, enucleation, and medical management 2: Medical management, penetrating keratoplasty, intracameral fluconazole, enucleation 3. Medical management, two therapeutic keratoplasties (TPK), intracameral amphotericin B, enucleation |

1: Enucleation 2: Enucleation 3: Endophthalmitis and enucleation |

| 3 | Kate et al. [31] | India | 54-year-old male | Peripheral ulcerative keratitis | Pythium was confirmed by zoospore formation and DNA sequencing; histopathology showed filaments | Medical management (topical vancomycin and ciprofloxacin) and topical and oral corticosteroids worsened the disease; later, TPK. Medical management of Pythium was started | ||

| 4 | Zhang et al. [16] | China (article in Chinese) | 4 males, 2 females, mean age in years ± standard deviation 58.7 ± 11.3, age range, 52–72 years | Dry surface of the corneal ulcer, satellite lesions, pseudopodia around the ulcer, the immune ring was not seen | There was a poor response to antifungal drugs. All patients received keratoplasties. Recurrence was noted in 3 patients [4–6 days after the first surgery and 2–3 days after the second surgery | Evisceration was needed for some eyes | ||

| 5 | Vishwakarma et al. [20] | India | 18 patients (15 males, 3 females), mean age 45.50 ± 15.35 years, low socioeconomic status | Agricultural injury, dust, soil, cement, insect | All patients had unilateral involvement. Corneal ulcer with tentacle-like extension, reticular dot-like infiltrates, feathery margins, ring infiltrates, corneal perforation, hypopyon, peripheral corneal thinning, descemetocele, blurred or irregular ulcer margins |

Smear [Gömöri methenamine silver: 93.8% positivity, iodine-potassium iodide-sulfuric acid: 100% positivity, periodic acid–Schiff's: negative staining in 62.5% and weak staining in 37.5%] Culture [blood agar, chocolate agar] Histopathology of the corneal button |

Anti-pythium therapy with topical or systemic linezolid and azithromycin (TPK) was needed in 15 eyes, re-TPK in 4 eyes, and evisceration in 3 eyes. One eye was managed medically | Globe salvage in 15 eyes, 1 eye underwent evisceration, 7 eyes had good visual outcome, 2 eyes developed phthisis, graft failure in 6 eyes, late presenters had worse outcomes and more complications |

| 6 | Puangsricharern et al. [24] | Thailand | 25 patients (26 eyes), 14 males, 11 females, mean age 46.1 ± 14.0 (range 21–73) years | Contaminated water, foreign body (soil, plants), ocular injury | Reticular infiltration, satellite infiltration, multifocal infiltration, total infiltration | Gram staining, 10% potassium hydroxide preparation, and cultivation on blood agar, chocolate agar, and Sabouraud dextrose agar, PCR-based assay amplifying the internal transcribed spacer region and cytochrome oxidase II gene, DNA-sequencing | Medical management, Pythium antigen immunotherapy (PIAI), 21 eyes needed TPK, 3 eyes eviscerated, recurrence in 15 of 21 eyes: 8 eyes had 2nd TPK, 7 eyes underwent evisceration or enucleation | Risks of globe removal include late initiation of therapy, advanced presentation, advanced age, dense hyphae infiltration of the cornea |

| 7 | Gurnani et al. [10] | India | 30 patients, mean age, 18 males and 12 females, 43.1 ± 17.2 years | Injury—80% and exposure to dirty water—23.3% | Most common hypopyon and stromal infiltrate in 46.6%, other features tentacles, reticular dot infiltrates, guttering | Scraping Gram stain and 10 5 KOH, culture on blood agar preoperatively and post TPK, zoospore identification by leaf incarnation method | Before culture—All patients—antifungals (5% natamycin, 1% itraconazole, 1% voriconazole, after culture results—All were treated with 1% azithromycin and 0.2% linezolid and 19 required TPK | Seven-graft reinfection, Seven healed with medical management, 3 endophthalmitis |

| 8 | Gurnani et al. [33] | Indian | 1 patient, 9-year-old male | Stick injury | 6 × 5 mm dry, mid-stromal corneal ulcer | Scraping 10% KOH and Gram stain, culture blood agar, and zoospore identification by leaf incarnation method | 5% natamycin and 1% itraconazole hourly before culture results, after culture results, 0.2% linezolid and 1% azithromycin hourly, cyanoacrylate glue | Healed infiltrate with final visual acuity of 6/12 |

| 9 | Nonpassopon et al. [23] | Thailand |

6 patients, mean age 34 ± 16.3 years, 3 males, 3 females |

Contact lens wear, tap water, river, and seawater contamination | Mean ulcer size 3.33 ± 1.31 mm, tentacles, feathery edges, satellite lesions, and radial keratoneuritis | CL culture | Failed conservative management, all patients TPK | Globe salvage—83.3% |

| 10 | Sane et al. [21] | India | 21 patients | - | Large infiltrates in 60% | Characteristic features om 10% potassium hydroxide, calcofluor white wet mount—95.23% patients, and Gram stain in 85.71% | Topical and oral linezolid, topical azithromycin, 4 patients underwent TPK, 1 evisceration | Medical resolution in 82.35% |

| 11 | Bagga et al. [67] | India |

112 patients were reviewed, 69 were analyzed Mean age medical treatment group (n = 38) 38.7 ± 15.2 years. Penetrating keratoplasty group (n = 31) 37.9 ± 14.2 years |

Trauma Foreign body Contaminated water |

Endoexudates—7, tentacles—60, guttering—32, pinhead lesions—57, plaque—14, perforation—1, central thinning—9, hypopyon—32 | Coenocytic aseptate/sparsely septate filaments—38 patients on scraping and culture (KOH, blood agar) | Topical and oral linezolid, topical azithromycin, natamycin, voriconazole, moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, ketoconazole, prednisolone acetate, TPK—44.9% cases | Successful management in the majority of patients with topical and oral antibiotic therapy |

| 12 | Maeno et al. [18] | Japan | 20-year-old male | Contact lens | Paracentral corneal infiltrate |

Gram stain—fungal filaments PCR-Pythium insidiosum In vitro disc diffusion assay revealed sensitivity to antibiotics |

Liposomal amphotericin B 100 mg initially, after disc diffusion assay, minocycline 4 times, 1200 mg linezolid oral, topical chloramphenicol hourly Later TPK |

Improved outcome with triple therapy and TPK, final visual acuity 20/25 |

| 13 | Bernheim et al. [76] | France | 20-year-old male | Swimming pool water, contact lens | Corneal abscess and perilesional corneal infiltrates | Conventional smears—fungal mycelial growth, PCR on 38th day Pythium insidiosum, mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF)—Pythium | Topical hexamidine, PHMB, vancomycin, amikacin, cross-linking, TPK, voriconazole IV, 2% cyclosporin, amphotericin B, voriconazole topical, oral doxycycline, clindamycin, Azithromycin | Successful resolution with antibiotic therapy |

| 14 | Hasika et al. [15] | India | 71 patients, mean age 44 ± 18.2 years |

50% Farmers, Dust—40.8% patients Vegetative matter—17% Dirty water—7% Insect injury—7% |

Tentacle like infiltrate—50.7% Dot infiltrate—21.1% Peripheral furrowing—12.7% Perforated corneal ulcer—7% Total corneal ulcer—8.5% |

10% KOH and Gram stain—fungal hyphae in 77.5%, culture of smear and corneal button—Blood agar, leaf incarnation | 5% natamycin + 1% voriconazole—42%, 5% natamycin—39.4%, 1% itraconazole 10%, TPK—67.6% | 54.2% graft reinfection, three eyes underwent eviscerations, 4 had anterior staphyloma, and 13 became phthisical |

| 15 | Raghavan et al. [28] | India | 21-year-old young male | Contact lens, dust exposure | 4 × 5 mm patchy mid-stromal infiltrate |

Gram stain—Fungal hyphae, Nutritional agar—BA, SDA, NNA, BHI Confocal microscopy—Combined Pythium and Acanthamoeba |

Topical PHMB, 5% natamycin, 1% voriconazole, Homide, moxifloxacin and linezolid | Resolution of Infiltrate with visual acuity of 6/18 |

| 16 | Agarwal et al. [25] | India | 46 patients | 6 patient history of vegetative matter trauma, rest all urban locals | Subepithelial infiltrates, reticular pattern—15 eyes, full-thickness infiltrate with hypopyon—13 eyes, limbus to limbus infiltrate—16 eyes, perforation—1 eye | PCR-based DNA sequencing | Topical and oral Azithromycin, topical linezolid, TPK, cryotherapy ± alcohol with TPK | Graft infection 27 eyes, Repeat TPK—11 eyes, Evisceration—5 eyes, 100% recurrence after medical management, 50% after TPK, 7% after cryotherapy |

| 17 | Neufeld et al. [26] | Canada | 51-year-old male | Crohn's disease, Contact lens | Epithelial breach, stromal infiltrate | Gömöri methenamine silver—septate hyphae, PCR-confirmatory of Pythium, corneal biopsy and confocal microscopy—negative |

Topical propamidine, moxifloxacin, chlorhexidine, amphotericin B, natamycin, and voriconazole Non-resolving ulcer-TPK |

Enucleated eye |

| 18 | Bagga et al. [8] | India | 114 patients | Farmers—40.4%, homemakers—23.6%, students/office goers—36%, foreign body injury—43.8%, dirty water exposure—0.9% | Full-thickness infiltrate—44.4%, infiltrate to 1/3 depth—13.4%, posterior stromal involvement—4.1%, dot infiltrates—16.3%, tentacles—6.1%, reticular pattern—1%, ring infiltrate—2%, endoexudates—10.2, hypopyon—54% | Culture of zoospore | Topical natamycin, linezolid, azithromycin, oral azithromycin, TPK | The rate of TPK reduced in patients treated with antibacterials compared to antifungals |

| 19 | Rathi et al. [77] | India | 70-year-old male | Contaminated tap water | Full-thickness corneal ulcer with thinning | Gram stain showed Gram-positive cocci, KOH, and confocal—fungal hyphae, corneal button culture on SDA—hyphae, PCR—Pythium, MRI suggestive of cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis | Topical antibiotics, antifungals, TPK | Exenteration later—lid sparing |

| 20 | Chatterjee et al. [78] | India | 7-year-old boy | No history of trauma | Central corneal infiltrate with thinning |

10% KOH and gram stain—aseptate fungal hyphae Repeat scrapping—Aseptate broad hyaline hyphae, ribbon-like folds, and perpendicular bends |

First visit—5% natamycin and 1% voriconazole, and after rescrapping 1% Azithromycin, 1% Voriconazole, and 1% Atropine, Oral 250 mg Azithromycin and Cyanoacrylate glue with BCL | Vascularized corneal opacity, PKP awaited |

| 21 | Agarwal et al. [12] | India | 10 patients, age range 19–50 years | 3 Farmers, 5 software professionals, 2 housewives, no trauma history | Full-thickness infiltrate—6 eyes, subepithelial and superficial stromal infiltrate, hypopyon, reticular pattern, endo-exudates | All patients Gram stain, KOH, culture on blood agar, chocolate agar and SDA, PCR, and confocal microscopy in 1 patient | TPK—10 eyes, 6 cryotherapy, repeat TPK—2 eyes, 2 eyes absolute alcohol application | Graft infection—10 eyes, 2 eyes evisceration, 2 eyes scleritis |

| 22 | Ramappa et al. [17] | India | 42-year-old female | History of trivial injury | Greyish white dense stromal infiltrate, tentacles, pinhead-size peripheral lesions |

Gram stain, 10% KOH, 0.1% Calcofluor white, Ziehl–Neelsen stain—1% H2SO4, GMS stain Culture on blood agar, chocolate agar, SDA, LJ medium |

Topical 0.2% linezolid, oral azithromycin 500 mg, 1% atropine, topical 1% azithromycin | Corneal scar at 3 weeks |

| 23 | He et al. [37] | China | 7-year-old male child | Twig injury | 3 × 2 m peripheral nasal corneal infiltrate, peripheral multiple radial keratoneuritis | Acridine orange, Lactophenol cotton blue—show sparse septate hyphae, thick cell wall, numerous vesicles, Confocal microscopy—multiple Refractile filaments, PDA corneal button culture showed—Pythium | Topical natamycin, Fluconazole ½ hourly, topical Fluconazole ointment HS and 100 mg oral Voriconazole, Later TPK | Conjunctivilization of the cornea, visual acuity hand moments |

| 24 | Lelievre et al. [32] | France | 30-year-old female | Contact lens | Central subepithelial and stromal infiltrate, reticular pattern, feathery margins, satellite lesions |

May–Grünwald–Giemsa staining Culture -Chocolate PolyViteX agar, Schaedler broth with globular extract, and SDA, Corneal button—Pythium positive, Confocal microscopy—fungal filaments |

Topical 0.25% amphotericin B, 1% voriconazole, topical and oral capsofungin, topical bacitracin and Coly-Mycin eye drops, oral voriconazole 200 mg BD 3 days, later TPK | Graft failure |

| 25 | Hung and Leddin [79] | Canada | 51-year-old male | Immunosuppression due to Crohn's disease | Central corneal infiltrate | Corneal biopsy and culture-negative, histopathological analysis of enucleated eye revealed Pythium |

Oral adalimumab 80 mg/ week Later TPK |

Enucleated eye |

| 26 | Barequet et al. [80] | Israel | 24-year-old male | Swimming pool water and contact lenses | Corneal abscess | Culture—showed septate mold, PCR depicted Pythium | Topical fortified antibiotics, natamycin, voriconazole and IV voriconazole | No recurrence |

| 27 | Thanathanee et al. [22] | Thailand | 5 eyes, 4 patients | Contaminated water | Subepithelial and stromal infiltrates, reticular infiltrates | Gram stain—fungal filaments, KOH stain—fungal filaments, culture, confocal microscopy—negative, Pythium, was confirmed by PCR |

Topical natamycin 5%, ketoconazole 2%, oral ketoconazole 400 mg, oral terbinafine 250 mg, oral itraconazole, topical AMB 0.3% with ketoconazole Later TPK. Pythium vaccination |

Evisceration in 1 eye |

| 28 | Tanhehco et al. [27] | USA | 21-year-old male | Tap water rinsing and contact lenses | Inferior limbal stromal infiltrates, endo-exudates, hypopyon | Culture negative, CL culture—Enterobacter, Confocal microscopy suggestive of Acanthamoeba, Corneal button culture with PAS and GMS—Zygomycetes | Topical fortified antibiotics, antifungals, topical chlorhexidine, oral voriconazole, antiglaucoma drugs, and later TPK | Graft infection, repeat TPK, and enucleation |

| 29 | Badenoch et al. [81] | Australia | 3-year-old child | Swimming in public pool, vegetative matter trauma | Central corneal infiltrate, stromal melt, thinning, hypopyon | Gram stain—hyphae less well stained and polymorphonuclear cells, culture on blood, chocolate, and non-nutrient agar—filamentous growth—Suspected Pythium |

Topical 1% voriconazole, PHMB 0.02% 4 times and oral 100 mg voriconazole BD Later TPK Postoperatively—FML 0.1% eye drops |

Graft stable, visual acuity 20/80 |

| 30 | Lekhanont et al. [82] | Thailand | 22-year-old female | Contact lens | 5.4 × 5.2 mm central subepithelial to stromal infiltrates with perineural infiltrates | Gram stain—white blood cells, KOH negative, corneal button culture on GMS and SDA revealed Pythium |

Topical vancomycin 50 mg/ml and ceftazidime 50 mg/ ml hourly Later TPK |

Two times regraft, Enucleation |

| 31 | Kunavisarut et al. [83] | Thailand | 10 patients with 8 complete information, mean age of 49.8 years | 7 farmers | Fungal corneal ulcer-like picture | Diagnosis on histology—Pythium | Topical antifungals and antibiotics, all patients underwent TPK, 1 anterior lamellar keratectomy | 7 Evisceration and enucleated eyes |

| 32 | Badenoch et al. [84] | Malaysia | 32-year-old male | Contact lens wear and swimming | Epithelial defect, deep stromal infiltrate approaching the limbus, and hypopyon |

Gram and Giemsa stain negative, biopsy revealed hyphae, culture showed filamentous microorganism DNA sequencing confirmed Pythium keratitis |

Antifungals—oral itraconazole and topical natamycin. Topical antibacterials and anti-amoebic medications. Later therapeutic keratoplasty and anterior chamber wash | 7 months postoperatively patient had clear graft, working vision, and no evidence of recurrence of infection |

| 33 | Murdoch and Parr [85] | New Zealand | 28-year-old male | Bath in a hot pool | 6 × 6 mm mid—stromal infiltrate with hypopyon, later perforation | 3 sets of corneal scraping, 3 scrapings revealed fungal hyphae | Topical 5% natamycin, 2% miconazole ointment, oral 5 fluorocytosine 150 mg/kg, ketoconazole 200 mg BD and later topical prednisolone and TPK | Evisceration after 10 days |

| 34 | Virgile et al. [3] | USA | 31-year-old female | Sickle cell trait | Posterior stromal corneal infiltrate with hypopyon, Later perforation | Gram stain—Gram-positive diplococci, the biopsy revealed Staph epidermidis, SDA showed Pythium growth |

IV Gentamicin—70 mg TDS, Toba 15 mg/ml hourly, Cefazolin 1 gm TDS Later TPK |

Anterior segment reconstruction |

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Dr. Joseph Gubert for providing microbiological images for the article. They also wish to thank Aravind Eye Hospital and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology, Pondicherry, India; Sankara Nethralaya, Chennai; The Ottawa Hospital, University of Ottawa Eye Institute, Ontario, Canada; Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, United States of America; Aravind Eye Hospital and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, India; and ASG Eye Hospital, BT Road, Kolkata, India.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: BG, KK, SA; drafting manuscript: BG, KK, SA, NS, VL, AV, KT, GI, BS, JG; critical revision of manuscript: BG, KK, SA, NS, AV, VL, KT; supervision: BG, SA, VL, NS GI, BS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Bharat Gurnani, Kirandeep Kaur, Shweta Agarwal, Vaitheeswaran G Lalgudi, Nakul S. Shekhawat, Anitha Venugopal, Koushik Tripathy, Geetha Iyer and Joseph Gubert have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This review article is based on previously conducted studies. The article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Bharat Gurnani, Email: drgurnanibharat25@gmail.com.

Kirandeep Kaur, Email: beingkirandeep@gmail.com.

Shweta Agarwal, Email: shwe20@yahoo.com.

Vaitheeswaran G. Lalgudi, Email: kanthjipmer@gmail.com

Nakul S. Shekhawat, Email: nshekha1@jhmi.edu

Anitha Venugopal, Email: aniths22@ymail.com.

Koushik Tripathy, Email: koushiktripathy@gmail.com.

Bhaskar Srinivasan, Email: drbhaskar75@gmail.com.

Geetha Iyer, Email: drgeethaiyer@gmail.com.

Joseph Gubert, Email: joseph_gubert@yahoo.co.in.

References

- 1.Lang-Yona N, Pickersgill DA, Maurus I, et al. Species richness, rRNA gene abundance, and seasonal dynamics of airborne plant-pathogenic oomycetes. Front Microbiol. 2018;15(9):2673. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waterhouse GM. Key to Pythium Pringsheim. Mycol Pap. 1967;109:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virgile R, Perry HD, Pardanani B, et al. Human infectious corneal ulcer caused by Pythium insidiosum. Cornea. 1993;12(1):81–83. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaastra W, Lipman LJ, De Cock AW, Exel TK, Pegge RB, Scheurwater J, Vilela R, Mendoza L. Pythium insidiosum: an overview. Vet Microbiol. 2010;146(1–2):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yolanda H, Krajaejun T. Global distribution and clinical features of pythiosis in humans and animals. J Fungi (Basel) 2022;8(2):182. doi: 10.3390/jof8020182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yolanda H, Krajaejun T. History and perspective of immunotherapy for pythiosis. Vaccines. 2021;9:1080. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurnani B, Kaur K, Venugopal A, et al. Pythium insidiosum keratitis—a review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(4):1107–1120. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1534_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagga B, Sharma S, Madhuri Guda SJ, et al. Leap forward in the treatment of Pythium insidiosum keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102(12):1629–1633. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mittal R, Jena SK, Desai A, Agarwal S. Pythium insidiosum keratitis: histopathology and rapid novel diagnostic staining technique. Cornea. 2017;36(9):1124–1132. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurnani B, Christy J, Narayana S, Rajkumar P, Kaur K, Gubert J. Retrospective multifactorial analysis of Pythium keratitis and review of literature. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(5):1095–1101. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1808_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma S, Balne PK, Motukupally SR, et al. Pythium insidiosum keratitis: clinical profile and role of DNA sequencing and zoospore formation in diagnosis. Cornea. 2015;34(4):438–442. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal S, Iyer G, Srinivasan B, et al. Clinical profile of Pythium keratitis: perioperative measures to reduce risk of recurrence. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:153–157. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anutarapongpan O, Thanathanee O, Worrawitchawong J. Role of confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of Pythium insidiosum keratitis. Cornea. 2018;37:156–161. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keeratijarut A, Lohnoo T, Yingyong W, et al. Detection of the oomycete Pythium insidiosum by real-time PCR targeting the gene coding for exo-1,3-β-glucanase. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64(9):971–977. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasika R, Lalitha P, Radhakrishnan N, Rameshkumar G, Prajna NV, Srinivasan M. Pythium keratitis in South India: Incidence, clinical profile, management, and treatment recommendation. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(1):42–47. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_445_18.PMID:30574890;PMCID:PMC6324135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang XY, Qi XL, Lu XH, Gao H. Clinical features and treatment prognoses of Pythium keratitis. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2021;57(8):589–594. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112142-20201023-00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramappa M, Nagpal R, Sharma S, Chaurasia S. Successful medical management of presumptive Pythium insidiosum keratitis. Cornea. 2017;36(4):511–514. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeno S, Oie Y, Sunada A, Tanibuchi H, Hagiwara S, Makimura K, Nishida K. Successful medical management of Pythium insidiosum keratitis using a combination of minocycline, linezolid, and chloramphenicol. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2019;18(15):100498. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2019.100498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das AV, Chaurasia S, Joseph J, Roy A, Das S, Fernandes M. Clinical profile and microbiological trends of therapeutic keratoplasty at a network of tertiary care ophthalmology centers in India. Int Ophthalmol. 2022;42(5):1391–1399. doi: 10.1007/s10792-021-02127-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vishwakarma P, Mohanty A, Kaur A, et al. Pythium keratitis: clinical profile, laboratory diagnosis, treatment, and histopathology features post-treatment at a tertiary eye care center in Eastern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(6):1544–1552. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2356_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sane SS, Madduri B, Mohan N, Mittal R, Raghava JV, Fernandes M. Improved outcome of Pythium keratitis with a combined triple drug regimen of linezolid and azithromycin. Cornea. 2021;40(7):888–893. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thanathanee O, Enkvetchakul O, Rangsin R, Waraasawapati S, Samerpitak K, Suwan-Apichon O, et al. Outbreak of Pythium keratitis during rainy season: a case series. Cornea. 2013;32:199–204. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182535841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nonpassopon M, Jongkhajornpong P, Aroonroch R, Koovisitsopit A, Lekhanont K. Predisposing factors, clinical presentations, and outcomes of contact lens-related Pythium keratitis. Cornea. 2021;40(11):1413–1419. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puangsricharern V, Chotikkakamthorn P, Tulvatana W, et al. Clinical characteristics, histopathology, and treatment outcomes of Pythium keratitis: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;23(15):1691–1701. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S303721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agarwal S, Iyer G, Srinivasan B, et al. Clinical profile, risk factors and outcome of medical, surgical and adjunct interventions in patients with Pythium insidiosum keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(3):296–300. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neufeld A, Seamone C, Maleki B, Heathcote JG. Pythium insidiosum keratitis: a pictorial essay of natural history. Can J Ophthalmol. 2018;53(2):e48–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanhehco TY, Stacy RC, Mendoza L, Durand ML, Jakobiec FA, Colby KA. Pythium insidiosum keratitis in Israel. Eye Contact Lens. 2011;37(2):96–98. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e3182043114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raghavan A, Bellamkonda P, Mendoza L, Rammohan R. Pythium insidiosum and Acanthamoeba keratitis in a contact lens user. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11(1):bcr2018226386. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-226386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bharathi JM, Srinivasan M, Ramakrishnan R, Meenakshi R, Padmavathy S, Lalitha PN. A study of the spectrum of Acanthamoeba keratitis: a three-year study at a tertiary eye care referral center in South India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55(1):37–42. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.29493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Meenakshi R, Padmavathy S, Shivakumar C, Srinivasan M. Microbial keratitis in South India: influence of risk factors, climate, and geographical variation. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14(2):61–69. doi: 10.1080/09286580601001347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kate A, Bagga B, Ahirwar LK, Mishra DK, Sharma S. Unusual presentation of Pythium keratitis as peripheral ulcerative keratitis: clinical dilemma. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;19:1–4. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1952276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lelievre L, Borderie V, Garcia-Hermoso D, et al. Imported Pythium insidiosum keratitis after a swim in Thailand by a contact lens-wearing traveler. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(2):270–273. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurnani B, Narayana S, Christy J, Rajkumar P, Kaur K, Gubert J. Successful management of pediatric Pythium insidiosum keratitis with cyanoacrylate glue, linezolid, and azithromycin: rare case report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;28:11206721211006564. doi: 10.1177/11206721211006564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chitasombat MN, Jongkhajornpong P, Lekhanont K, Krajaejun T. Recent update in diagnosis and treatment of human pythiosis. PeerJ. 2020;20(8):e8555. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ong HS, Sharma N, Phee LM, Mehta JS. Atypical microbial keratitis. Ocul Surf. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagga B, Vishwakarma P, Sharma S, Jospeh J, Mitra S, Mohamed A. Sensitivity and specificity of potassium hydroxide and calcofluor white stain to differentiate between fungal and Pythium filaments in corneal scrapings from patients of Pythium keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(2):542–545. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1880_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He H, Liu H, Chen X, Wu J, He M, Zhong X. Diagnosis and treatment of Pythium insidiosum corneal ulcer in a Chinese child: a case report and literature review. Am J Case Rep. 2016;27(17):982–988. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.901158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rathi VM, Murthy SI, Mitra S, Yamjala B, Mohamed A, Sharma S. Masked comparison of trypan blue stain and potassium hydroxide with calcofluor white stain in the microscopic examination of corneal scrapings for the diagnosis of microbial keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(9):2457–2460. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3434_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma S, Rathi VM, Murthy SI, Garg P, Sharma S. Application of trypan blue stain in the microbiological diagnosis of infectious keratitis—a case series. Cornea. 2021;40(12):1624–1628. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mittal R, Agarwal S. Reply. Cornea. 2018;37(3):e14–e15. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anutarapongpan O, Thanathanee O, Worrawitchawong J, Suwan-Apichon O. Role of confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of Pythium insidiosum keratitis. Cornea. 2018;37(2):156–161. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mani R, Vilela R, Kettler N, Chilvers MI, Mendoza L. Identification of Pythium insidiosum complex by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Med Microbiol. 2019;68(4):574–584. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inkomlue R, Larbcharoensub N, Karnsombut P, et al. Development of an anti-elicitin antibody-based immunohistochemical assay for diagnosis of pythiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(1):43–48. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02113-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pracharktam R, Changtrakool P, Sathapatayavongs B, Jayanetra P, Ajello L. Immunodiffusion test for diagnosis and monitoring of human pythiosis insidiosium. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(11):2661–2662. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2661-2662.1991.PMID:1774283;PMCID:PMC270400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jindayok T, Piromsontikorn S, Srimuang S, Khupulsup K, Krajaejun T. Hemagglutination test for rapid serodiagnosis of human pythiosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16(7):1047–1051. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00113-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chareonsirisuthigul T, Khositnithikul R, Intaramat A, et al. Performance comparison of immunodiffusion, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunochromatography and hemagglutination for serodiagnosis of human pythiosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76(1):42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keeratijarut A, Karnsombut P, Aroonroch R, Srimuang S, Sangruchi T, Sansopha L, Mootsikapun P, Larbcharoensub N, Krajaejun T. Evaluation of an in-house immunoperoxidase staining assay for histodiagnosis of human pythiosis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40(6):1298–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kulandai LT, Lakshmipathy D, Sargunam J. Novel duplex polymerase chain reaction for the rapid detection of Pythium insidiosum directly from corneal specimens of patients with ocular pythiosis. Cornea. 2020;39(6):775–778. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kammarnjesadakul P, Palaga T, Sritunyalucksana K, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Pythium insidiosum Thai strains using cytochrome oxidase II (COX II) DNA coding sequences and internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS) Med Mycol. 2011;49(3):289–295. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.511282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kosrirukvongs P, Chaiprasert A, Uiprasertkul M, et al. Evaluation of nested PCR technique for detection of Pythium insidiosum in pathological specimens from patients with suspected fungal keratitis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2014;45(1):167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Htun ZM, Rotchanapreeda T, Rujirawat T, et al. Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) for Identification of Pythium insidiosum. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garzón CD, Geiser DM, Moorman GW. Diagnosis and population analysis of pythium species using AFLP fingerprinting. Plant Dis. 2005;89(1):81–89. doi: 10.1094/PD-89-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azevedo MI, Botton SA, Pereira DI, Robe LJ, Jesus FP, Mahl CD, Costa MM, Alves SH, Santurio JM. Phylogenetic relationships of Brazilian isolates of Pythium insidiosum based on ITS rDNA and cytochrome oxidase II gene sequences. Vet Microbiol. 2012;159(1–2):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ribeiro TC, Weiblen C, de Azevedo MI, de Avila BS, Robe LJ, Pereira DI, Monteiro DU, Lorensetti DM, Santurio JM. Microevolutionary analyses of Pythium insidiosum isolates of Brazil and Thailand based on exo-1,3-β-glucanase gene. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;48:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inkomlue R, Larbcharoensub N, Karnsombut P, Lerksuthirat T, Aroonroch R, Lohnoo T, Yingyong W, Santanirand P, Sansopha L, Krajaejun T. Development of an anti-elicitin antibody-based immunohistochemical assay for diagnosis of pythiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(1):43–48. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02113-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Choi YJ, Beakes G, Glockling S, Kruse J, Nam B, Nigrelli L, Ploch S, Shin HD, Shivas RG, Telle S, Voglmayr H, Thines M. Towards a universal barcode of oomycetes—a comparison of the cox1 and cox2 loci. Mol Ecol Resour. 2015;15(6):1275–1288. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Appavu SP, Prajna L, Rajapandian SGK. Genotyping and phylogenetic analysis of Pythium insidiosum causing human corneal ulcer. Med Mycol. 2020;58(2):211–218. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myz044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krajaejun T, Kunakorn M, Pracharktam R, et al. Identification of a novel 74-kiloDalton immunodominant antigen of Pythium insidiosum recognized by sera from human patients with pythiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(5):1674–1680. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1674-1680.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krajaejun T, Lohnoo T, Jittorntam P, et al. Assessment of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for identification and biotyping of the pathogenic oomycete Pythium insidiosum. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;77:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gurnani B, Kaur K. Pythium Keratitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- 61.Yolanda H, Krajaejun T. Review of methods and antimicrobial agents for susceptibility testing against Pythium insidiosum. Heliyon. 2020;6(4):e03737. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loreto ES, Tondolo JS, Pilotto MB, Alves SH, Santurio JM. New insights into the in vitro susceptibility of Pythium insidiosum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(12):7534–7537. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02680-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pereira DI, Santurio JM, Alves SH, et al. Caspofungin in vitro and in vivo activity against Brazilian Pythium insidiosum strains isolated from animals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(5):1168–1171. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahirwar LK, Kalra P, Sharma S, et al. linezolid shows high safety and efficacy in the treatment of Pythium insidiosum keratitis in a rabbit model. Exp Eye Res. 2021;202:108345. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Livermore DM. Linezolid in vitro: mechanism and antibacterial spectrum. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(Suppl 2):ii9–ii16. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jelić D, Antolović R. From erythromycin to azithromycin and new potential ribosome-binding antimicrobials. Antibiotics (Basel) 2016;5(3):29. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics5030029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bagga B, Kate A, Mohamed A, Sharma S, Das S, Mitra S. Successful strategic management of Pythium insidiosum keratitis with antibiotics. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(1):169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agarwal S, Srinivasan B, Janakiraman N, et al. Role of topical ethanol in the treatment of Pythium insidiosum keratitis—a proof of concept. Cornea. 2020;39(9):1102–1107. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Loreto ES, Tondolo JSM, de Jesus FPK, et al. Efficacy of miltefosine therapy against subcutaneous experimental pythiosis in rabbits. J Mycol Med. 2020;30(1):100919. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.100919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wittayapipath K, Yenjai C, Prariyachatigul C, et al. Evaluation of antifungal effect and toxicity of xanthyletin and two bacterial metabolites against Thai isolates of Pythium insidiosum. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4495. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61271-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lakhundi S, Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Cellulose degradation: a therapeutic strategy in the improved treatment of Acanthamoeba infections. Parasit Vectors. 2015;14(8):23. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0642-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loliam B, Morinaga T, Chaiyanan S. Biocontrol of Pythium aphanidermatum by the cellulolytic actinomycetes Streptomyces rubrolavendulae S4. Sci Asia. 2013;39:584–590. doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2013.39.584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pires L, Bosco Sde M, Baptista MS, Kurachi C. Photodynamic therapy in Pythium insidiosum—an in vitro study of the correlation of sensitizer localization and cell death. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roy A, Chaurasia S, Ramappa M, Joseph J, Mishra DK. Clinical profile of keratitis treated within 3 months of acute COVID-19 illness at a tertiary care eye centre. Int Ophthalmol. 2022;1:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10792-022-02288-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hou H, Wang Y, Tian L, Wang F, Sun Z, Chen Z. Pythium insidiosum keratitis reported in China, raising the alertness to this fungus-like infection: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):619. doi: 10.1186/s13256-021-03189-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bernheim D, Dupont D, Aptel F, et al. Pythiosis: case report leading to new features in clinical and diagnostic management of this fungal-like infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;86:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rathi A, Chakrabarti A, Agarwal T, et al. Pythium keratitis leading to fatal cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis. Cornea. 2018;37(4):519–522. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chatterjee S, Agrawal D. Azithromycin in the management of Pythium insidiosum keratitis. Cornea. 2018;37(2):e8–e9. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hung C, Leddin D. Keratitis caused by Pythium insidiosum in an immunosuppressed patient with Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(10):A21–A22. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barequet IS, Lavinsky F, Rosner M. Long-term follow-up after successful treatment of Pythium insidiosum keratitis in Israel. Semin Ophthalmol. 2013;28(4):247–250. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2013.788676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Badenoch PR, Mills RA, Chang JH, Sadlon TA, Klebe S, Coster DJ. Pythium insidiosum keratitis in an Australian child. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37(8):806–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lekhanont K, Chuckpaiwong V, Chongtrakool P, Aroonroch R, Vongthongsri A. Pythium insidiosum keratitis in contact lens wear: a case report. Cornea. 2009;28(10):1173–1177. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318199fa41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kunavisarut S, Nimvorapan T, Methasiri S. Pythium corneal ulcer in Ramathibodi Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86(4):338–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Badenoch PR, Coster DJ, Wetherall BL, et al. Pythium insidiosum keratitis confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(4):502–503. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.4.496g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Murdoch D, Parr D. Pythium insidiosum keratitis. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1997;25(2):177–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1997.tb01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]