Abstract

IL-17 cytokine family members have diverse biological functions, promoting protective immunity against many pathogens but also driving inflammatory pathology during infection and autoimmunity. IL-17A and IL-17F are produced by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells, and various innate immune cell populations in response to IL-1β and IL-23, and they mediate protective immunity against fungi and bacteria by promoting neutrophil recruitment, antimicrobial peptide production and enhanced barrier function. IL-17-driven inflammation is normally controlled by regulatory T cells and the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10, TGFβ and IL-35. However, if dysregulated, IL-17 responses can promote immunopathology in the context of infection or autoimmunity. Moreover, IL-17 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of many other disorders with an inflammatory basis, including cardiovascular and neurological diseases. Consequently, the IL-17 pathway is now a key drug target in many autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders; therapeutic monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-17A, both IL-17A and IL-17F, the IL-17 receptor, or IL-23 are highly effective in some of these diseases. However, new approaches are needed to specifically regulate IL-17-mediated immunopathology in chronic inflammation and autoimmunity without compromising protective immunity to infection.

Subject terms: Immunotherapy, Cytokines, Antimicrobial responses

IL-17 cytokines drive biological responses that protect the host against many infections but can also contribute to host pathology in the context of infection and autoimmunity. Here, Kingston Mills highlights the different cellular sources of IL-17 and compares the pathological versus protective functions of these cytokines.

Introduction

Since its discovery nearly 30 years ago1,2, IL-17 has emerged as a key cytokine for host protection against mucosal infections but also as a major pathogenic cytokine and drug target in multiple autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. The IL-17 family comprises six members (IL-17A to IL-17F) that mediate their biological functions through the IL-17 receptors (IL-17RA to IL-17RE). The most studied IL-17 family member is IL-17A (referred to hereafter as IL-17 unless otherwise stated) and it, as well as IL-17F, promotes its biological activities by binding to IL-17RA and IL-17RC (Box 1).

It is now appreciated that IL-17 evolved to mediate innate immunity in invertebrates, which lack adaptive immune systems. However, the inflammatory functions of IL-17 were originally described in mouse models of autoimmune disease, where the initial focus was on IL-17-secreting CD4+ T cells — T helper 17 (TH17) cells — as a key producer of this cytokine. We now know that CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), natural killer (NK) cells, invariant NK T cells, mucosal associated invariant T cells, mast cells and Paneth cells can also be sources of IL-17. Although T cell receptor (TCR) activation is key for IL-17 production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, IL-17 production by innate immune cells is primarily driven by inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-1β and IL-23 (Box 2). Neutrophils may also be a source of IL-17 during infection3, although this has been questioned by others4.

Studies of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a mouse model for multiple sclerosis (MS), suggested that IL-17 was a key pathogenic cytokine in T cell-mediated autoimmune disease pathology5–7. It was subsequently shown that, in EAE, IL-17 is secreted by TH17 cells and by IL-17-secreting γδ T (γδT17) cells8,9. These studies and others detailing pathological roles of IL-17 in human diseases eventually culminated in the development of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that target IL-17A, both IL-17A and IL-17F, IL-17RA, or IL-23, a cytokine produced by innate immune cells that promotes the expansion of TH17 cell populations. These mAbs have been licensed for the treatment of certain autoimmune diseases, especially psoriasis, where their efficacy has surpassed traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-blocking drugs10–12.

Clinical trials and real-world use demonstrated an increase in fungal and upper respiratory tract bacterial infections in patients treated with mAbs that block the IL-23–IL-17 pathway10,13–15. Interestingly, although decreased resistance to infection might have been expected to be more frequent with the use of the anti-IL-12p40 mAb ustekinumab — which blocks both IL-12 and IL-23, thereby inhibiting both TH1 and TH17 cell-associated responses (Fig. 1) — a comparative analysis revealed that this was not the case15, at least for Candida infections, where IL-17 plays a key protective role. A mAb that neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F (bimekizumab) that was more effective than an anti-IL-17A mAb (secukinumab) at reducing symptoms in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis was associated with a higher incidence of mild-to-moderate oral candidiasis11. The incidence of oral candidiasis was also higher in patients given bimekizumab as opposed to adalimumab (an anti-TNF mAb) to treat plaque psoriasis12. These studies provided evidence that IL-17A and IL-17F have protective roles against certain infections, especial those caused by fungal pathogens in humans. However, more unequivocal evidence for a host-protective role for IL-17 came from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes coding for IL-17A, IL-17RA, IL-17RC, IL-23 or NF-κB activator 1 (ACT1, an adapter protein downstream of the IL-17R, also known as TRAF3-interacting protein 2 (TRAF3IP2)) that abolished cellular responsiveness to IL-17A and IL-17F. These SNPs were associated with susceptibility to chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), a persistent infection of the skin, nails and/or mucosae with commensal Candida species16.

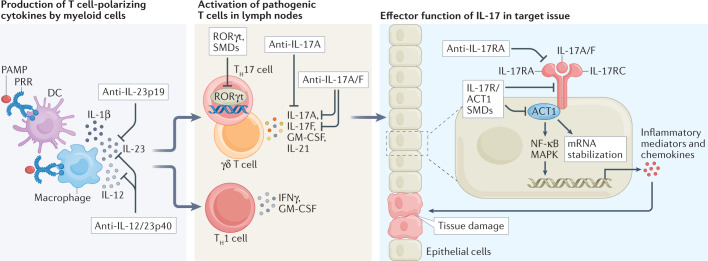

Fig. 1. Drug targets in the IL-23–IL-17 pathway.

Activation of dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages through pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) promotes production of IL-23 and IL-1β, which play a major role in the induction and/or expansion of populations of T helper 17 (TH17) cells, IL-17-secreting γδ T (γδT17) cells and other IL-17-secreting cells (not shown). By contrast IL-12 production by DCs and macrophages promotes development of TH1 cells. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that neutralize IL-12p40 (ustekinumab) suppress TH1 cell as well as TH17 cell and γδT17 cell responses, whereas mAbs that neutralize IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab and risankizumab) specifically block IL-17-secreting cells. The RORγt transcriptional factor is the master regulator of IL-17 production in diverse cell types and a target for small molecule drugs (SMDs) in development. TH17 cells, γδT17 cells and other IL-17-secreting cells (not shown) co-produce IL-17A and IL-17F and, while most of the focus has been on mAbs specific for IL-17A (secukinumab and ixekizumab), antibodies that neutralize both IL-17A and IL-17F (bimekizumab) are also in clinical use. These, together with mAbs that bind to IL-17RA (brodalumab) and inhibit binding of IL-17A and IL-17F to IL-17RA–IL-17RC, appear to be marginally more effective than anti-IL-17A mAbs. Finally, peptides, macrocycles and other SMDs that target IL-17R or ACT1 are also in development. GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern.

Mechanistic studies in animal models of fungal and bacterial infection demonstrated a key protective role for IL-17 at mucosal surfaces, largely mediated by chemokine-driven neutrophil recruitment, antimicrobial peptide (AMP) production and enhanced mucosal barrier function. Thus, IL-17 is not only a pathogenic cytokine in inflammatory diseases but also a key cytokine in host protective immunity to infection. However, even in the setting of infection, IL-17 appears to be a double-edged sword, with defective IL-17 production allowing unchecked expansion of certain pathogens but excessive IL-17 production mediating damaging immunopathology. Several studies have shown that TH17 cell plasticity may underlie many of the pathological roles of these cells in disease settings. This Review discusses the dual role of IL-17 in driving protective immunity to infection and immunopathology in inflammatory diseases.

Box 1 IL-17 family members.

IL-17A was the first member of the IL-17 family to be identified1,218. The murine Il17 gene, initially called mCTLA8, was cloned from a T cell hybridoma and had 57% homology with the ORF13 gene of the T lymphotropic virus herpesvirus Saimiri1. It was thought that this virus-captured cellular gene was related to the immune system or to cell death and survival. It was then reported that murine and human IL-17A protein was produced by T cells and had cytokine-like properties, including the induction of NF-κB activity and IL-6 production by fibroblasts2,218. IL-17B to IL-17F were identified based on homology with IL-17A. Furthermore, an additional member, IL-17N, was found in Japanese pufferfish219. The biological function of the IL-17A to IL-17F family is mediated through the IL-17 receptor family, IL-17RA to IL-17RE, with IL-17A and IL-17F binding to IL-17RA and IL-17RC. IL-17A–IL-17F heterodimers can also form a ternary complex with IL-17RA and IL-17RC220. IL-17A has a non-redundant role in the control of many fungal and bacterial infections but is also a key pathogenic cytokine in many autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. IL-17F has overlapping and some distinct functions to IL-17A. For example, blocking IL-17A and IL-17F is more effective than blocking IL-17A alone in treatment of psoriasis but is associated with a higher incidence of oral candidiasis11. IL-17B, which binds to IL-17RB, has anti-inflammatory properties, limiting inflammation in the colon and in allergic asthma; it inhibits IL-25 (IL-17E), another member of the IL-17 cytokine family that also binds to IL-17RB221. IL-25 enhances type 2 cytokine and eosinophil responses in the lung and may be a mediator of allergic airway diseases222. IL-17C, which signals through the IL-17RE–IL-17RA complex, promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine and antibacterial peptide production, especially in response to intestinal pathogens53, and also promotes neutrophilia and inflammatory gene expression in the lungs222.

Box 2 Cellular sources of IL-17 and their stimuli.

CD4+ T helper 17 (TH17) cells are a key source of IL-17A but can also produce IL-17F, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-21, IL-22, IFNγ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)223,224. IL-6 and TGFβ were initially described as differentiation factors for TH17 cells225–227. However, it was later demonstrated that IL-23 in synergy with IL-1 (IL-1β or IL-1α) or IL-18 in combination with T cell receptor (TCR) ligation promotes activation of mouse and human memory TH17 cells5–7. A population of CD4+ T cells that produce IL-17 without TCR engagement have been called natural TH17 (nTH17) cells228,229. These nTH17 cells differentiate in the thymus, express the transcription factor RORγt, IL-23R, α4β1 integrins and CCR6, produce IL-17A, IFNγ and IL-22, and develop in the absence of IL-6 required by inducible TH17 cells230,231. nTH17 cells mediate host protection at mucosal surfaces through IL-17 and IL-22 production228,229. IL-17-secreting CD8+ T cells produce a similar range of cytokines and are activated in a similar fashion to TH17 cells. IL-17-secreting γδ T cells produce the same range of cytokines as TH17 cells but are activated by IL-1β and IL-23 without TCR stimulation8,232. A novel population of T cells, that co-expresses αβ and γδ TCRs and high levels of IL-1 and IL-23 receptors, produces IL-17A, GM-CSF and IFNγ following stimulation with IL-1β and IL-23 with or without TCR stimulation151. CD1d-dependent invariant NKT cells produce IL-17 in response to glycolipid antigens and IL-1β and TGFβ233,234. Finally, type 3 innate lymphoid cells produce IL-17A and IL-22 in response to IL-1β and IL-23 (refs.235,236).

TH17 cell plasticity

TH17 cells can display plasticity in cytokine production in vivo and can switch from predominantly producing IL-17 to predominantly producing IFNγ, thereby resembling TH1 cells17. These TH1-like ‘ex-TH17’ cells are expanded in the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), are functionally distinct from other TH1 and TH17 cell populations, and escape regulation by regulatory T (Treg) cells18. TH17 cell plasticity is influenced by T cell-polarizing cytokines and the inflammatory tissue environment. IL-12 suppresses expression of RORγt and IL-17 but enhances IFNγ production by human TH17 cells19. Fate mapping studies in mice with EAE showed that, as disease developed, TH17 cells in the spinal cord produced less IL-17 and more IFNγ, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and TNF20. By contrast, in acute cutaneous Candida albicans infection, TH17 cells stopped producing IL-17 but did not switch to IFNγ production20. Consistent with these findings, we found that CD4+ T cells from Il17a−/− mice could transfer EAE to naive mice21. However, blocking GM-CSF or IFNγ in vivo had little impact on the course of disease whereas blocking IL-17, especially at induction of EAE, prevented development of disease21. Furthermore, in humans, antibodies that target IL-17 are almost as effective as antibodies that target IL-17R or IL-23 in the treatment of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis10–13,22. Therefore, while some TH17 cells may stop producing IL-17 in vivo, IL-17 still has a pathogenic role in certain autoimmune diseases, either as an effector cytokine or in the priming of TH17 cells21. Furthermore, studies in an infection model showed that antigen-specific TH17 cells in the nasal tissue of mice infected with Bordetella pertussis predominantly produce IL-17, without IFNγ, during the course of infection and persist as tissue resident memory T (TRM) cells that still predominantly produce IL-17 upon re-activation many months after bacterial clearance23. This suggests that, at least in certain infection settings, IL-17-secreting CD4+ T cells show a relatively stable phenotype.

There is emerging evidence that cellular metabolism can influence TH17 cell plasticity. In models of intestinal infection, it was shown that segmented filamentous bacterium (SFB) induced TH17 cells that produced IL-17A and IL-22 and mainly use oxidative phosphorylation, which is typical of what is seen in quiescent or memory T cells24. These TH17 cells did not show production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines. By contrast, TH17 cells induced during infection with Citrobacter rodentium were highly glycolytic and exhibited plasticity towards pro-inflammatory cytokine production24.

TH17 cells can also produce IL-10, and such regulatory-type TH17 cells fail to promote autoimmune inflammation in the EAE model25. This contrasts with the IL-1β-stimulated and IL-23-stimulated TH17 cell populations that produce IL-17 and GM-CSF without IL-10, which are pathogenic in the EAE model6,26,27. Studies with human TH17 cells showed that TH17 cells induced in the skin by C. albicans co-produced IL-17 and IFNγ but not IL-10, whereas TH17 cells induced in the skin in response to Staphylococcus aureus produced IL-17 and IL-10 (ref.28). This suggests that the nature of the pathogen or the innate immune response against a pathogen can determine the nature of the TH17 response. Notably, IL-1β suppresses IL-10 production by TH17 cells28, confirming a key role for IL-1β in the development of pathogenic TH17 cells6. These findings provide further evidence that the cytokine milieu generated by innate immune cells in the tissue environment influences the plasticity of TH17 cells. Overall, such plasticity in TH17 cell populations may allow the cells to control infection while in most settings, avoiding excessive inflammation or the development of autoimmune disease.

IL-17 in immunity to infection

Fungal infections

There is convincing evidence from IL-17 polymorphism studies in humans and experiments with knockout mice that IL-17-secreting cells play a central role in protective immunity to Candida and other fungal pathogens. Individuals with autosomal recessive deficiency in IL17RA29 or mutations in ACT1 (ref.30) are susceptible to the development of CMC. In addition, CMC is associated with dominant-negative mutations in STAT3, which is a key transcription factor in the IL-6, IL-21 and IL-23 signalling pathways required for the development of TH17 cells. Furthermore, patients treated with anti-IL-17 mAbs have an increased risk of developing oropharyngeal, oesophageal and cutaneous candidiasis31.

Studies in mouse models showed enhanced fungal burden post challenge in mice lacking IL-17 or its receptor. Enhanced kidney infection and poorer survival in Il17ra−/− mice after systemic challenge with C. albicans was associated with reduced recruitment of neutrophils to the kidneys32. Oral candidiasis was more severe in Il23p19−/− mice and Il17ra−/− mice than in wild-type mice, but was not more severe in Il12p35−/− mice, suggesting that TH17 cells, and not TH1 cells, were required for protection, which was mediated by recruitment of neutrophils and β-defensin production33. IL-17RA-deficient humans and mice are highly susceptible to oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) and have reduced levels of CXC chemokines and impaired neutrophil recruitment to the oral mucosa. Mice lacking IL-17RA or ACT1 were more susceptible to OPC than Il17a−/− mice, suggesting a role for both IL-17F and IL-17A in antifungal immunity in the oropharynx34.

Although TH17 cells are a key source of IL-17 in fungal infections, in a model of OPC, IL-17-secreting CD8+ T cells compensated for a lack of CD4+ T cells35. NK cells36 and ILCs37 are also important sources of IL-17A and IL-17F in immunity to fungal infections. However, it has been reported that natural TH17 cells and γδ T cells, but not ILCs, are key sources of IL-17 in the control of oral candida infection33. In a model of Aspergillus-induced keratitis, neutrophils produced and responded to IL-17 to mediate fungal clearance through the production of reactive oxygen species3.

IL-17 can also modulate protective TH1 cell responses and enhance immunopathology in fungal infections. In a mouse model of infection with Cryptococcus deneoformans, a fungal pathogen that can cause fatal meningoencephalitis in immunosuppressed patients, early secretion of IL-17 by γδ T cells suppresses the protective TH1 cell responses required for fungal clearance and promotes neutrophil-associated inflammation38. In a mouse model of skin infection with the fungus Microsporum canis, an absence of IL-17 resulted in enhanced TH1 cell responses, increased colonization of the epidermis and more severe skin inflammation39. Furthermore, patients and mice with AIRE deficiency, which results in enhanced TH1 cell responses but not enhanced TH17 cell responses, show increased susceptibility to mucosal but not systemic fungal infections40. Enhanced expression of IFNγ without impaired IL-17 led to defects in mucosal barrier functions that increased susceptibility to infection and inflammation at mucosal sites.

Chronic paracoccidioidomycosis caused by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in humans is associated with neutrophil infiltration into the lungs and the development of granulomatous lesions and pulmonary fibrosis41. Depletion of neutrophils in mice reduced the inflammatory responses in lungs and pulmonary fibrosis induced by P. brasiliensis41. Interestingly the depletion of neutrophils not only reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1α and IL-1β, but also reduced the number of TH17 cells in the lungs. This is consistent with a role for IL-1-producing neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes in feedback activation of IL-17 production by TH17 cells21. These findings demonstrate that IL-17-mediated neutrophil recruitment and activation, while playing a key protective role in many fungal infections, can also contribute to infection-associated immunopathology. In conclusion, IL-17 is clearly a key protective cytokine in anti-fungal immunity but, in certain settings, IFNγ can also have a protective role. However, if not properly regulated, these cytokines can also mediate pathology during fungal infections.

Bacterial infections

Early studies revealed that IL-17 is upregulated in the gastric mucosa of humans infected with Helicobacter pylori and in vitro studies showed that it enhanced IL-8 secretion from gastric epithelial cells, which promoted neutrophil chemotaxis42. Mechanistic studies by Ye et al. showed that Il17ra−/− mice but not control animals rapidly succumbed to lethal infection after intranasal challenge with Klebsiella pneumoniae43. This study was the first to link IL-17 signalling with neutrophil recruitment; K. pneumoniae-infected Il17ra−/− mice had defective neutrophil recruitment associated with reduced production of CXC-chemokine ligand 2 (CXCL2, also known as MIP2) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)43. Furthermore, IL-17 and IL-22 promoted the production of CXC chemokines and G-CSF in the lung and enhanced lung barrier function and resistance to damage44. Therefore, IL-17 and IL-22, produced by TH17 cells, appear to have distinct and overlapping roles in immunity to this bacterial infection, with both cytokines promoting AMP production while IL-22 is more involved in barrier function and IL-17 in neutrophil recruitment. In addition to promoting indirect recruitment of neutrophils by inducing chemokine production, IL-17 can directly activate bacterial killing by neutrophils and macrophages. IL-17-mediated protection against nasopharyngeal colonization with Streptococcus pneumoniae involves recruitment and pneumococcal killing by neutrophils45. In B. pertussis infections in mice, IL-17 plays a critical role in the clearance of primary and secondary infections of the nasal mucosa by recruiting SIGLEC-F+ neutrophils that have high NETosis activity and by inducing AMP production23. IL-17 induced by infection with Francisella tularensis mediates its protective effects indirectly by promoting IFNγ production, which enhances bacterial killing by macrophages46. However, it is possible that this may reflect plasticity of TH17 cells, with a shift to IFNγ production. There is also evidence that IL-17 synergizes with IFNγ to enhance nitric oxide production by macrophages, thereby promoting protection against Chlamydia infection47. Furthermore, IL-17 and IFNγ enhance intracellular killing of B. pertussis by macrophages48 and neutrophils49. In addition, immunization studies with a candidate Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine in mice suggested that IL-17-secreting T cells that accumulate in the lung promote chemokine production that recruits TH1 cells to control the infection50. These findings suggest a positive or synergistic influence of IL-17 on the IFNγ response to certain bacterial infections, although it may also reflect TH17 cell plasticity in vivo.

TH17 cells may also have more direct antibacterial activities. TH17 cell clones specific for the skin commensal bacteria Cutibacterium acnes secrete extracellular traps that capture bacteria and kill them through secreted antimicrobial proteins51. The antimicrobial function of TH17 cells may also be mediated through their production of IL-26, which kills extracellular bacteria through membrane pore formation52. IL-17C, which is largely produced by non-immune cells, such as colon epithelial cells, synergizes with IL-22 to produce AMPs that protect against C. rodentium53. Furthermore, IL-17C produced by respiratory epithelial cells mediates protective immunity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa by inhibiting siderophore activity in the nasal epithelium54.

IL-17-secreting CD4+ TRM cells play a key role in sustaining adaptive immunity to bacterial infections, especially in the respiratory tract. These cells confer protection against reinfection of the lung and nose with B. pertussis23,55. Current injectable acellular pertussis vaccines fail to induce respiratory TRM cells but this can be reversed by adding an adjuvant that induces IL-1 and IL-23 expression and drives IL-17-secreting TRM cells to the respiratory tissues56. Using IL-17A fate mapping mouse models, it has been demonstrated that lung CD4+ TRM cells that confer protective memory against K. pneumoniae are derived from TH17 cells that can be induced by immunization with heat-killed K. pneumoniae57. IL-17-secreting TRM cells are more readily induced by previous mucosal infection or with vaccines administered by respiratory rather than by parenteral routes. Respiratory tract-delivered candidate vaccines protect against lung infection with M. tuberculosis58 and against nasal infection with B. pertussis23,59 largely through induction of IL-17-secreting TRM cells, which mediate their protective effects through the recruitment of neutrophils, activation of AMP production and/or IgA production.

Although CD4+ T cells were identified as a major source of IL-17 in antibacterial immunity, γδ T cells also contribute, especially early in infections at mucosal surfaces. In mouse models, γδ T cells are also a major source of IL-17, which mobilizes neutrophils during peritoneal infection with Escherichia coli60, liver infection with Listeria monocytogenes61, intestinal infection with L. monocytogenes62, cutaneous infection with S. aureus63, and respiratory infection with S. pneumoniae64 or B. pertussis55. In a B. pertussis infection model, innate Vγ4−γ1− γδ T cells provide early IL-17 production, whereas adaptive antigen-specific Vγ4+ γδ T cells are induced later in infection and become TRM cells that rapidly produce IL-17 and contribute to protection against reinfection55. Memory γδT17 cells also mediate protection against reinfection with S. aureus65. In an S. aureus skin infection mouse model, IL-17 produced by Vγ6+ γδ T cells induces neutrophil recruitment, the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-1β and TNF, and host defence peptides66.

In addition to its protective role, IL-17 can also promote detrimental inflammatory responses to bacterial infections. In sepsis models, IL-17 was associated with abscess formation following Bacteroides fragilis challenge in TH2-impaired Stat6−/− mice; treatment with anti-IL-17 mAbs prevented abscess formation67. Similarly, neutralization of IL-17 significantly reduced bacteraemia and systemic levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and enhanced survival in mice with sepsis induced by caecal ligation and puncture68.

Colonization with the commensal microorganism SFB induces TH17 cells that produce IL-17 and IL-22, which confers resistance against the intestinal pathogen C. rodentium69. However, TH17 cells induced by SFB can also promote autoimmune arthritis in mice70. TH17 cells also have a pathogenic role in infection-induced neutrophilic inflammation associated with allergic airway inflammation in mouse models of neutrophilic asthma in humans71. Neutralization of IL-17 prevented enhancement of allergic airway inflammation induced by respiratory infection with Moraxella catarrhalis72. Finally, IL-36-induced IL-17 production by TH17 cells and γδT17 cells has been implicated in S. aureus-induced skin inflammation and atopic dermatitis73. Collectively, these findings suggest that, while IL-17 plays a protective role in immunity to many bacteria, excessive IL-17 and associated neutrophilia can result in immunopathology, which can extend to precipitation or exacerbation of inflammatory diseases (Fig. 2).

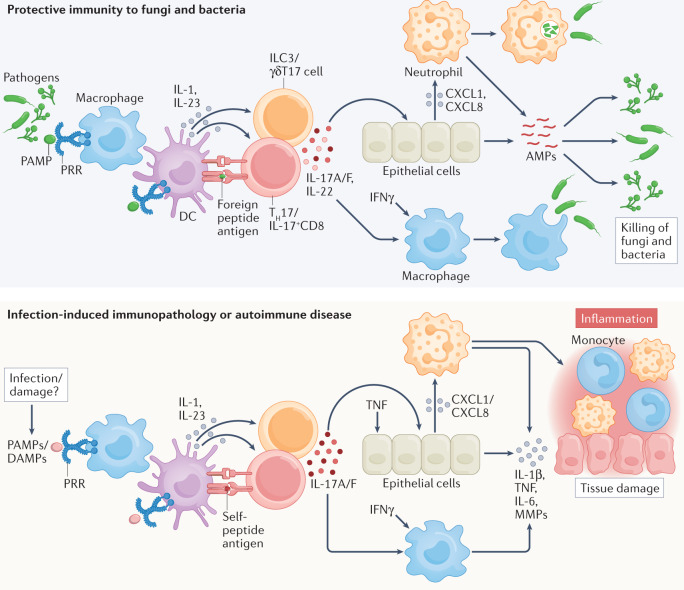

Fig. 2. Role of IL-17 in protective immunity versus immunopathology.

During infection, pathogens release pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that bind to pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and activate innate immune cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), which present foreign peptide antigens to T cells and provide a source of T cell-polarizing cytokines. IL-1β and IL-23 activate T helper 17 (TH17) cells, IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells (IL-17+CD8+), type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3s) and IL-17-secreting γδ T (γδT17) cells, which produce IL-17A and IL-17F as well as other pro-inflammatory cytokines (not shown) that promote the production of neutrophil-recruiting chemokines from epithelial cells (for example, in respiratory tract or intestine). IL-17, together with IFNγ, can also activate macrophages. Activated macrophages and neutrophils phagocytose and kill intracellular bacteria, fungi and protozoan parasites. IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-22 promote the production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and enhance epithelial barrier function. In autoimmune diseases (or infection-indued immunopathology), the same responses, triggered by infection or damage during sterile inflammation (damage-associated molecular patterns; DAMPs), can promote auto-antigen-specific TH17 cells and γδT17 cells that produce IL-17A and IL-17F, which in combination with tumour necrosis factor (TNF), act on epithelial cells (for example, keratinocytes in psoriasis) to produce chemokines that recruit neutrophils and macrophages, promoting inflammation. IL-17 also activates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that mediate the tissue damage and inflammation that lead to autoimmune diseases. CXCL, CXC-chemokine ligand.

Viral infections

Antigen-specific TH17 cells or IL-17+CD8+ T cells are induced during human infection with various viruses, including influenza virus74, HIV1 (ref.75) and hepatitis C virus (HCV)76. However, the role of IL-17 in immunity to viruses is still unclear. Evidence of a positive role for IL-17 came from the demonstration that IL-23 enhances resistance to vaccinia virus infection in mice and treatment with anti-IL-17 mAbs exacerbated the viral load77. Studies with SIV-infected rhesus macaques revealed that SIV depletes TH17 cells in the ileal mucosa and impairs mucosal immunity to Salmonella Typhimurium78. Memory α4+β7hiCD4+ T cells that produce IL-17 are preferentially infected and depleted during acute SIV infection, and the loss of these cells results in a skewing towards a TH1-type response and promotes disease progression79. In HIV infection, TH17 cells are reduced and Treg cells enhanced as disease progresses, resulting in impaired immune function75. TH17 cells may also be involved in vaccine-induced antiviral immunity, for example, in protection against HSV2 infection by enhancing TH1-type TRM cells in the female genital tract80.

TH17 cells and IL-17+CD8+ T cells protect against disease and lethality in mice infected with influenza virus by promoting neutrophil influx into the lung74. There is also evidence that γδT17 cells may promote clearance of influenza virus from the respiratory tract and protect against infection-associated mortality in neonatal mice by promoting IL-33-induced infiltration of ILC2s and Treg cells, which enhance amphiregulin secretion and tissue repair81. In humans, the number of γδT17 cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with influenza virus-associated pneumonia is negatively associated with disease severity82.

While the protective role for IL-17 in immunity to viruses is still not clear, there is strong evidence that it can promote inflammatory pathology during viral infection. Virus-specific TH17 cell populations are expanded in the circulation and liver of individuals with HCV infection and, while these cells appear to be regulated by endogenous IL-10 and TGFβ76, their numbers correlate with the severity of liver inflammation but not with HCV replication83. Hepatic damage is associated with high numbers of TH17 cells and IL-17+CD8+ T cells and a lower frequency of T cells that co-produce IL-17, IL-10, IFNγ and IL-21 (ref.84). TH17 cell populations are also expanded in the circulation and liver of patients with hepatitis B virus infection, and the level of fibrosis in these patients correlates with IL-17 production85. IL-17 contributes to liver disease progression by activating stellate cells that promote liver fibrosis86. IL-17 can promote hepatocyte necrosis by neutrophil activation in aged mice infected systemically with herpes viruses87. Similarly, TH17 cells contribute to the pathogenesis of stromal keratitis following cornea infection in mice with HSV1; pathology is alleviated by neutralization of IL-17 (ref.88). Furthermore, TH17 cells promote viral replication and myocarditis following coxsackievirus B3 infection in mice; aggressive myocarditis was linked with overactive TH1 cell and CD8+ T cell responses89. IL-17+CD8+ T cells induced in LCMV-infected mice that had CD8+ T cells deficient in T-bet and Eomes promote inflammation associated with multi-organ neutrophil infiltration and wasting syndrome90, suggesting that pathogenic IL-17 responses by CD8+ T cells may normally be regulated by IFNγ or Treg cells.

IL-17 can promote lung inflammation associated with influenza virus infection. Patients infected with pandemic H1N1pdm09 strains of influenza virus had elevated levels of IL-17 and TH17 cells, which was associated with acute lung injury, and studies in a mouse model showed that influenza virus-induced lung damage could be ameliorated by neutralization of IL-17 (ref.91). Gastroenteritis-like symptoms following lung infection with influenza virus are associated with intestinal microbiota-induced recruitment of TH17 cells that mediates intestinal injury92. Furthermore, signalling via IL-17R and the associated neutrophil recruitment and tissue myeloperoxidase production have been linked with acute lung injury following influenza infection93.

In respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, IL-17 has been linked with protective immunity and immunopathology. Humans that resist RSV infection have high pre-symptomatic IL-17 signalling in the nasal mucosae, whereas those that develop disease have neutrophilic inflammation and suppressed TH17 cell responses94. In mice, IL-17 produced by γδ T cells protected against RSV-induced lung inflammation95. Furthermore, IL-17 can inhibit airway hyper-responsiveness (AHR) in mice infected with RSV by suppressing type 2 cytokines and eosinophil recruitment96. However, there is evidence that TH17 cells and neutrophils contribute to lung pathology in RSV-associated AHR through complement activation97. IL-17-induced neutrophils have also been implicated in airway inflammation and AHR following infection of mice with enterovirus 68, which may explain the asthma-like symptoms observed in people infected with this virus98.

IL-17 may play a pathogenic role in lung inflammation and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) associated with severe COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2. TH17 cell populations are expanded and activated in patients with COVID-19 who develop pulmonary complications99. Furthermore, hyperinflammation and lung damage in patients with COVID-19 are associated with enhanced TH17 cell responses100, neutrophilia and increased NETosis101. Individuals with SNPs in IL17A that reduce IL-17 expression have decreased susceptibility to ARDS, whereas SNPs in IL17A that result in more IL-17 correlate with enhanced lung inflammation102. IL-17 is also elevated in patients with obesity, and this may partly explain the greater risk of developing ARDS associated with COVID-19 that is seen in these patients103. IL-17 signalling pathway genes are upregulated in different organs and tissues following SARS-CoV-2 infection104. In a mouse model, lung-infiltrating TH17 cells, macrophages and neutrophils were associated with the increased inflammatory cytokine response that occurred following infection with SARS-CoV-2 (ref.105). A small clinical trial in which patients with COVID-19 were treated with the anti-IL-17 mAb netakimab showed that it reduced lung lesion volume and the need for oxygen support and enhanced survival106. However, in another study, treatment with netakimab reduced C-reactive protein levels and improved some clinical parameters but did not reduce the need for mechanical ventilation nor did it enhance survival in patients with COVID-19 (ref.107). Nevertheless, these and other studies suggest that transient inhibition of IL-17 may be a therapeutic option for controlling excessive inflammation during acute viral infections.

Parasitic infections

There is evidence of protective roles for IL-17 in immunity to certain parasites, especially intracellular protozoa, through its roles in promoting the activation of monocytes and/or macrophages. However, IL-17 does not have a major role in mediating immunity to large multicellular parasites and can even promote infection-induced immunopathology in this setting, largely through the recruitment of neutrophils.

IL-17 has a protective role against the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi in mice, controlling infection-induced inflammation by inhibiting IFNγ production as well as inflammatory responses that mediate hepatic damage by recruiting IL-10-secreting immunosuppressive neutrophils108. In humans, high levels of IL-17 are associated with better cardiac function in individuals with Chagas disease, which is caused by infection with T. cruzi109. Furthermore, SNPs in the IL17A gene are associated with susceptibility to the development of chronic cardiomyopathy following infection with T. cruzi110.

IL-23-induced IL-17, together with IL-22, has protective roles against visceral leishmaniasis in humans, which is caused by the protozoan Leishmania donovani111. IL-17 acts synergistically with IFNγ to promote nitric oxide production by macrophages infected with Leishmania infantum, thereby suppressing the parasitic infection in mice112. However, IL-17 produced by γδ T cells can inhibit host control of intracellular infection of monocytes with L. donovani113. It has also been demonstrated that TGFβ and IL-35 production from Treg cells controls chronic visceral leishmaniasis by downregulating TH17 cells114. Furthermore, IL-17 can promote disease progression in mice infected with Leishmania major through recruitment of neutrophils115. Similarly, immunopathology associated with mucosal leishmaniasis, a severe form of cutaneous leishmaniasis, is mediated by IL-17 production and neutrophil recruitment and associated with low concentrations of IL-10 (ref.116). Furthermore, IL-17-producing ILCs activated by skin microbiota promote skin inflammation in cutaneous leishmaniasis117.

Although IL-17 can promote protection against the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii by recruiting neutrophils118, antibody-mediated neutralization of IL-17 in disease-susceptible C57BL/6 mice reduced inflammation and enhanced survival during T. gondii infection, and this was associated with augmented production of IFNγ and IL-10 (ref.119). Furthermore, intraocular inflammation and uveitis during toxoplasmosis is suppressed by neutralizing IL-17; this was associated with enhanced induction of T-bet and IFNγ and a reduced parasite load120. Thus, the balance between IL-17 and IFNγ can determine the outcome of T. gondii infection. Collectively, these studies suggest that IL-17 has a protective role against intracellular parasites but that, in certain settings, IL-17 can also mediate immunopathology.

Protective immunity against large multicellular parasites, especially helminths, is mediated by type 2 immune responses and, although IL-17-producing T cells are induced during helminth infection, they predominantly mediate pathology. However, IL-17 has been shown to have protective as well as pathogenic roles during infection of the lung with the nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. IL-17 signalling via ACT1 in epithelial cells promotes the expansion of ILCs and drives type 2 immunity against N. brasiliensis121. Furthermore, early IL-17 production by ILCs promotes the development of protective type 2 responses by suppressing IFNγ but, later in infection, IL-17 also limits excessive type 2 responses, especially the activation of ILC2 (ref.122). IL-1β-induced IL-17 production by γδ T cells, induced by chitinase-like proteins, also has a protective role against infection with N. brasiliensis123. However, IL-17 can mediate helminth-induced lung inflammation by recruiting neutrophils123. IL-17 is also a major mediator of the immunopathology seen in mice124 and humans125 following infection with schistosomes, which are parasitic flatworms. Schistosoma mansoni egg antigen-induced immunopathology is associated with IL-17-mediated neutrophil recruitment and is restrained by IFNγ126. Antibody neutralization of IL-17 in mice infected with Schistosoma japonicum reduced worm and egg burdens as well as the percentages of neutrophils and eosinophils in liver granulomas while increasing the proportions of macrophages and lymphocytes127. Therefore, the role of IL-17 in parasitic infection tends to be more damaging than protective, especially against large extracellular parasites.

IL-17 in autoimmunity and inflammation

The sections above have considered the beneficial and detrimental effects of IL-17 induction in response to different types of infection. Below, I discuss the involvement of IL-17 in driving the pathology seen in autoimmune and other inflammatory diseases.

Inflammatory skin and joint diseases

IL-17 has a well-established role in the pathology of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. SNPs in IL17RA or in its promoter that enhance IL-17 responses have been identified as a risk factor for psoriasis128 and ankylosing spondylitis129. Studies in a mouse model of psoriasis, induced by topical application of the Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)/TLR8 ligand imiquimod, showed that disease was attenuated in mice deficient for IL-23 or IL-17R130. TH17 cells are found in the dermis of psoriasis skin lesions131 and mediate skin inflammation in mice and humans following recognition of self-lipid antigens presented by CD1a132. Furthermore, IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells with a tissue-resident phenotype are found in the synovial fluid of patients with psoriatic arthritis133. Other cellular sources of IL-17 — including γδ T cells, neutrophils and mast cells — and IL-23-driven induction of IL-22, may also be involved in the pathology of these diseases134.

A range of highly effective therapeutics that target the IL-23–IL-17 pathway are in widespread clinical use. Clinical trials revealed that antibodies that target IL-12p40 (ustekinumab), IL-17A (secukinumab and ixekizumab), IL-17A and IL-17F (bimekizumab), IL-17RA (brodalumab), and IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab and risankizumab) are effective for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis (Table 1). Blocking IL-17A and IL-17F with bimekizumab resulted in greater skin clearance in patients with psoriasis than blocking IL-17A alone with secukinumab11. Therapeutics that target the IL-23–IL-17 pathway are also efficacious for psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis22.

Table 1.

IL-17 pathway-targeted therapies in autoimmunity and inflammation

| Indication | Evidence of role for IL-17 pathway in animal models | Blocking IL-17 pathway in animal models | Evidence of role for IL-17 pathway in humans | mAb to IL-17 pathway in clinal trials/human use | Refs./Clinical trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis | Disease ameliorated in Il17a, Il17ra, Il23 KO mice | Anti-IL-17 mAbs and inhibitors of RORγt decrease disease in psoriasis model | IL17RA SNP associations; TH17 cells and γδT17 cells present in skin lesions | Ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, bimekizumab, brodalumab guselkumab, tildrakizumab and risankizumab: approved | 10–12,128,130–132,134 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Evidence from psoriasis models (above) | Evidence from psoriasis models (above) | TH17 cells, IL-17+CD8+ T cells, γδT17 cells and ILC3 in skin lesions and synovial fluid | Ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, guselkumab and risankizumab: approved | 13,133 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | IL-23 induces enthesitis, γδT17 cells involved | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease joint inflammation | Il23R, STAT3 and CARD9 SNP association | Secukinumab, ixekizumab and brodalumab: approved | 22,129,197 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | TH17 cells and γδT17 cells promote joint inflammation | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease joint inflammation | IL-17 in synovial fluid | Ustekinumab or guselkumab: no efficacy; secukinumab: low efficacy | 138–144 |

| Multiple sclerosis | TH17 cells and γδT17 cells transfer disease; EAE decreased in Il17a KO mice | Anti-IL-17 mAbs at induction decrease EAE | TH17 cells and γδT17 cells in brain lesions | Secukinumab: some efficacy, phase II | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | TH17 cells and ILC3 increase in gut; Il23 and Act1 KO mice show reduced colitis | Anti-IL-12p40 or anti-IL-23p19 mAbs decrease colitis, anti-IL-17 mAbs increase colitis | IL23R SNPs association; TH17 cells increase in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis | Ustekinumab: approved; secukinumab and brodalumab increase disease | 14,156–160,163 |

| TID | TH17 cells increase disease in NOD mice | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease disease | TH17 cells expanded in blood in patients with T1D | Ustekinumab and ixekizumab: phase II/III recruiting | |

| Uveitis | TH17 cells involved in pathology; decrease disease in Il17a KO mice | Anti-IL-17 mAb increase disease | Elevated IL-17 and IL-23 in blood | Secukinumab: phase III trials did not meet primary end point | |

| Atopic dermatitis | TH17 cells and IL-17 levels increase in acute skin lesions | NA | IL-17 increase in skin lesions, increased TH17 cells in blood | Secukinumab: phase II completed | |

| Neutrophilic asthma | IL-17 promotes neutrophilic influx in mouse allergic asthma model | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease neutrophil influx | IL17A SNP association, TH17 cells increase in blood | Secukinumab and brodalumab: phase II trials terminated | |

| GVHD | Transfer of TH17 cells induces GVHD | Anti-IL-23 mAbs or RORγt inhibitors decrease GVHD | Increased TH17 cells in blood of patients with GVHD | Ustekinumab: phase II completed, some benefit | |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | NA | NA | Substantial skin infiltrating CD161+ TH17 cells | Secukinumab: moderate efficacy, open-label trial; bimekizumab and secukinumab: phase III, ongoing |

ECT202000417942 ECT201800206326 |

| AD | γδT17 cells accumulate in brain in animal model; TH17 cells increase AD-like pathology | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease short-term memory deficit and neuro-inflammation | Increased TH17 cells in blood in mild cognitive impairment | Ustekinumab in AD: status unknown | |

| FLD | Obesity-associated IL-17 increases FLD | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease liver damage | IL-17 increased in obesity/liver disease | Secukinumab: completed | |

| COVID-19 | TH17 cells associated with inflammatory cytokine response | NA | TH17 cells increased in lungs in severe COVID-19/obesity | Netakimab: attenuated disease | 103–107 |

γδT17, IL-17-secreting γδ T; AD, Alzheimer disease; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; FLD, fatty liver disease; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; ILC3, type 3 innate lymphoid cell; KO, knockout; mAbs, monoclonal antibodies; NA, not applicable; NOD, non-obese diabetic mouse; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; TH17 cell, T helper 17 cell; TID, type 1 diabetes.

Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic inflammatory skin disease of hair follicles, is characterized by substantial skin infiltration of TH17 cells that express CD161, a lineage marker for TH17 cells135. Open-label pilot clinical trials with secukinumab showed moderate efficacy in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa136, and phase III trials are ongoing. Although secukinumab was not effective in treating alopecia areata137, there is off-label use of IL-17-blocking drugs for the treatment other skin disorders, including Behcet disease, lichen planus, pustular psoriasis, impetigo herpetiformis and pityriasis rubra pilaris.

RA is probably the disease where there was most promise but least return on IL-17 as a therapeutic target. High concentrations of IL-17 are present in the synovial fluid of patients with RA, where it promotes osteoclastogenesis138. Furthermore, TH17 cells from patients with RA promote the release of IL-6, IL-8 and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) by synovial fibroblasts139. In mouse models of RA, TH17 cells and γδT17 cells were found to mediate autoimmune arthritis140,141, and blocking IL-17 attenuated joint inflammation and cartilage destruction142. However, clinical trials in patients with RA using antibodies that target IL-17 or IL-23/IL-12p40 had low or no efficacy, respectively143,144. The limited therapeutic benefit of IL-17-targeted dugs in RA is not clear but may reflect disease heterogeneity or the fact that ex-TH17 cells (which produce IFNγ but not IL-17) rather than classical TH17 cells are enhanced in the synovial fluid of patients with RA18.

MS and EAE

Many of the initial discoveries on TH17 cells and on the pathogenic role of IL-17 in autoimmune disease were made in the EAE mouse model of MS. Although there was some scepticism around the precise role of IL-17 in EAE and MS and difficulty in translating findings from mice to humans, recent studies have provided convincing evidence that IL-17 is a key pathogenic cytokine in EAE and a major drug target in MS. IL17 mRNA is expressed in immune cells in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with MS145. Furthermore, TH17 cells cross the blood–brain barrier in individuals with MS and accumulate in areas of active lesions146. A proof-of-concept study in patients with relapsing-remitting MS showed that treatment with the anti-IL-17 mAb secukinumab reduced the number of cumulative new lesions by 67%147. Surprisingly, this has not been followed up in larger clinical trials despite the encouraging results from patients with MS and convincing data from the EAE model.

In the EAE model, TH17 cells, driven by IL-23 and IL-1β or IL-18, are a key T cell population that mediate pathology5–7. However, there is also evidence that autoantigen-specific TH1 cells can mediate EAE148 or enable TH17 cells to enter the central nervous system (CNS)149, which may involve IFNγ-mediated enhancement of VLA4 (the α4β1 integrin) expression on TH17 cells150. γδT17 cells are also found in high numbers in the CNS of mice with EAE, especially early in disease, and their depletion prevented the development of disease8. Furthermore, T cells co-expressing αβ and γδ TCRs are recruited to the CNS early in EAE, and these highly activated T cells act as an initial trigger for inflammatory responses by providing a very early source of IL-17 (ref.151). Collectively, these findings suggest that EAE pathology is not driven exclusively by IL-17 and TH17 cells and that other cytokines and cells, including CD8+ T cells and γδ T cells, may be involved.

It has also been suggested that IL-17 does not play a major role in EAE. Overexpression of IL-17 in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells did not enhance the severity of EAE, and anti-IL-17 mAb treatment of Il17f−/− mice did not affect the development of EAE152. However, treatment with anti-IL-17 mAb attenuated disease when administered at induction of disease or before relapse in the relapsing-remitting model of EAE but had little effect when administered at the peak of disease153. Similarly, treatment with anti-IL-17 mAb significantly reduced clinical scores when administered at induction but not after onset of clinical signs in the MOG-induced chronic EAE model21. Furthermore, Il17a−/− mice are resistant to induction of EAE21,154. A recent study from my group provided one explanation for some of the previous anomalies. We found that IL-17 has a priming role in EAE by inducing chemokines that recruit IL-1β-producing neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes that promote IL-17 production by γδ T cells, which kick-start the inflammatory cascade that mediates EAE21. It has also been suggested that the cells that mediate CNS pathology in EAE are GM-CSF+ IFNγ+ CXCR6+ pathogenic TH17 cells derived from stem-like TCF1+ IL-17+ SLAMF6+ T cells that have trafficked from the intestine, where they were maintained by the microbiota155. This is consistent with our demonstration that, while IL-17 is required to initiate inflammation, it is redundant at the effector stage of disease21. This does not rule out IL-17 being an important drug target in MS; on the contrary, blocking the IL-17 pathway may suppress induction or re-activation of TH17 cells and γδT17 cells and may therefore be an effective approach, as suggested by a clinical trial147, for the prevention of relapse in patients with relapsing-remitting MS.

Inflammatory bowel disease

The expression of IL-17 is significantly increased in the serum and inflamed mucosa of patients with active ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease156. Furthermore, GWAS studies showed that a non-synonymous SNP in the IL23R gene is associated with Crohn’s disease157. Studies in mouse models of colitis suggested that IL-17 produced by TH17 cells and/or ILCs and stimulated by IL-1β and IL-23 plays a critical role in chronic intestinal inflammation158,159. Furthermore, deletion of ACT1 in gut epithelial cells reduced IL-17-induced expression of CXCL1 (also known as KC), IL-6, and CXCL2 and attenuated colitis in mice160. However, there is also evidence that IL-23 promoted IFNγ, which synergizes with IL-17 to mediate intestinal inflammation161. Alternatively, pathology may be mediated by ex-TH17 cells, which are TH17 cells that have switched to become IFNγ-producing cells162.

These and other studies led to the testing of IL-17 and IL-23 targeted therapies for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and ustekinumab has been approved for treatment of Crohn’s disease. However, clinical trials with secukinumab or brodalumab in patients with IBD resulted in enhanced Candida infections and increased intestinal inflammation14,163. Although IL-17 and TH17 cells can drive inflammation that damages the gut mucosa, IL-17 and IL-22 also play protective roles in limiting fungal and bacterial infection of the gut164. Studies in mouse models showed that blocking IL-17 exacerbated intestinal inflammation, whereas blocking IL-12p40 or IL-23p19 conferred protection165. The protective effect of IL-17 was lost in mice lacking functional ACT1 in gut epithelial cells166, which is consistent with a role for IL-17 and IL-22 in protecting barrier integrity of the intestinal epithelium. However, it has also been demonstrated that IL-17F may have a pathogenic role in murine colitis and that blocking IL-17F but not IL-17A induced protective Treg cells through modification of the microbiota167.

Other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases

Studies in the experimental autoimmune uveitis mouse model showed that IL-17 plays a key role in pathology168 although disease could be induced by both TH1 and TH17 cells169. Clinical trials with secukinumab in patients with non-infectious uveitis did not meet the primary efficacy end point170. TH17 cells also have a pathogenic role in autoimmune diabetes. Treatment with anti-IL-17 mAbs or recombinant IL-25 (which inhibits TH17 cells) attenuated disease171. Furthermore, TH17 cells are expanded in the blood of patients with type 1 diabetes and IL-17 enhances inflammatory responses in human islet cells172. Clinical trials with anti-IL-12p40 and anti-IL-17 mAbs are ongoing in patients with type 1 diabetes. Evidence is emerging of a role for IL-17 in other autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, and in a broad range of diseases where inflammation is at the core of the pathology, including neurological diseases, metabolic diseases, asthma and cancer (Box 3 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Diseases in which targeting the IL-17 pathway could be explored in the future

| Indication | Evidence of role for IL-17 pathway in animal models | Blocking IL-17 pathway in animal models or in vitro | Evidence of role for IL-17 pathway in humans | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD | TLR-induced IL-17 in pregnant mice increase ASD in offspring | Anti-IL-17 mAbs in pregnancy decrease ASD in offspring | TH17 to Treg cell ratio in blood correlates with disease severity | 207,208 |

| PD | TH17 cells exacerbate dopaminergic neurodegeneration | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease IL-17-mediated cell death of PD-derived neurons | IL17A SNP association, increased TH17 in PD blood | 209–211 |

| Atherosclerosis | IL-17 and γδT17 cells promote high-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis | Anti-IL17 mAbs decrease atherosclerotic lesions | IL-17 increased disease in patients with hyperlipidaemia | 212,213 |

| IS | IL-17+ γδ T cells infiltrate lesion site after IS and mediate ischaemic brain tissue damage | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease BBB damage induced by γδ T cells that secrete IL-17 | IL17RC SNP association, IL-17 increased in serum during IS | 214–216 |

| Sepsis | TH17 and γδT17 cells decrease bacteria load but increase pathology | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease sepsis | IL-17 increased in human sepsis | 67,68,217 |

| Influenza virus associated inflammation | IL-17 increases lung inflammation and gastroenteritis during infection | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease influenza virus-induced lung damage | Not known | 91–93 |

| Stromal keratitis | TH17 cells increase HSV1-induced stromal keratitis | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease stromal keratitis | Not known | 88 |

| Parasitic infections | IL-17A increases helminth-induced neutrophil recruitment and lung damage | Anti-IL-17 mAbs decrease neutrophils and liver granulomas | IL-17 increases schistosomiasis-associated immunopathology | 124–127 |

γδT17, IL-17-secreting γδ T; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BBB, blood–brain barrier; IS, ischaemic stroke; mAbs, monoclonal antibodies; PD, Parkinson disease; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; TH17 cell, T helper 17 cell; TLR, Toll-like receptor; Treg, regulatory T.

Box 3 IL-17 in other diseases with an inflammatory basis.

In cancer, T helper 17 (TH17) cells and IL-17-secreting γδT (γδT17) cells can have protective roles in eradicating established tumours237 but IL-17 can also promote early tumour growth through induction of inflammatory mediators and wound-healing pathways238. IL-17 has structural similarity with nerve growth factor and other neurotrophins239 and appears to have a role in the pathogenesis of a range neuroinflammatory, neurological and neurodevelopmental diseases, including Alzheimer disease203,205, Parkinson disease209–211 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis240. IL-17 has also been shown to exacerbate neuropathic pain by suppressing inhibitory synaptic transmission241. Finally, there is evidence that IL-17 mediates autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the offspring of mice injected with poly(I:C) during pregnancy208. Furthermore, in children with ASD, circulating TH17 cells are increased, with the TH17 to regulatory T cell ratio positively correlating with disease severity207. IL-17 promotes damage to the blood–brain barrier during Streptococcus suis meningitis242. Therefore, infection-induced IL-17 during pregnancy or in infants may contribute to the development of ASD and other developmental disorders.

IL-17 has been implicated in high-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis in mice and in disease progression in patients with hyperlipidaemia213. IL-17 produced by γδT17 cells that infiltrate the aortic roots is involved in atherosclerotic lesion formation212. IL-17 also promotes coagulation and thrombosis and has been implicated in myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke214–216, hypertension and aneurysm formation243. γδT17 cells are found at high numbers in adipose tissue244 and IL-17 production during obesity enhances the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice206. IL-17 also plays a role in anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis and lupus nephritis245. Finally, IL-17 may play a pathogenic role in corticosteroid-insensitive neutrophilic asthma. In a mouse model of allergic asthma, IL-17 promoted neutrophil influx into the lungs, which was reversed by treatment with anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibodies199. Furthermore, IL-17 levels and TH17 cells are augmented in patients with neutrophilic asthma200. Although clinical trials have yet to demonstrate clear positive effects of blocking the IL-17 pathway in human asthma201, patient stratification in future trials may improve outcomes.

Regulation of IL-17 activity

Even though IL-17 is produced in response to most if not all infections and that this cytokine is central to the pathogenesis of many autoimmune diseases, most people do not succumb to these diseases. This reflects the existence of efficient host tolerance and regulatory mechanisms to control autoreactive TH17 cells and IL-17-induced inflammatory responses. Such mechanisms include Treg cells, alternatively activated macrophages, anti-inflammatory cytokines and immune-checkpoints that regulate T cell responses (Fig. 3). Thymically derived FOXP3+ Treg cells and peripherally induced Treg cells play key roles in regulating IL-17 to prevent autoimmunity and infection-induced immunopathology. Treg cells are co-induced with effector T cells and the outcome of these diseases can depend on their balance.

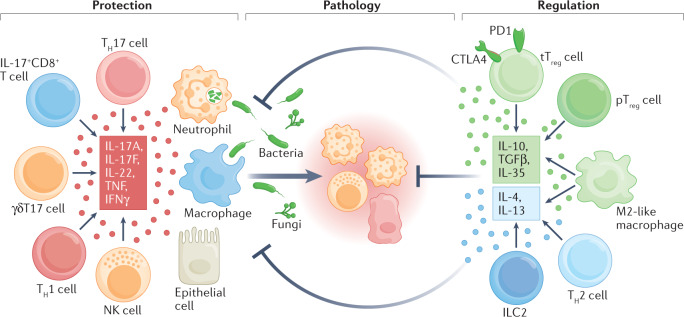

Fig. 3. Regulation of IL-17-producing cells that mediate pathology during infection or in autoimmune diseases.

IL-17A, IL-17F and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) produced by T helper 17 (TH17) cells, IL-17+CD8+ T cells or IL-17-secreting γδ T (γδT17) cells, and IFNγ produced by TH1 cells and natural killer (NK) cells recruit and/or activate neutrophils and macrophages that kill intracellular bacteria, fungi and small parasites. IL-17 and IL-22 also promote barrier function. These inflammatory responses can result in immunopathology and tissue damage unless they are tightly regulated. Regulation is mediated by thymically derived regulatory T (tTreg) cells, peripherally induced regulatory T (pTreg) cells, alternatively activated macrophages, TH2 cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2). These cells suppress effector T cells either through the production of immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10, TGFβ, IL-35, IL-4 and IL-13 or directly through the co-inhibitory molecules CTLA4 and PD1 expressed on tTreg cells.

Children infected with H. pylori have significantly lower IL-17 production, neutrophil infiltration and gastric inflammation but higher levels of IL-10 production and FOXP3+ Treg cells than in H. pylori-infected adults173, suggesting that Treg cells control inflammatory TH17 cell responses in vivo. In patients with MS, there is a normal overall frequency of FOXP3+ Treg cells in the circulation and these cells do not suppress TH17 cells; however, there is a reduced frequency of and loss of suppressive function in a subset of CD39-expressing FOXP3+ Treg cells that have been shown to inhibit pathogenic TH17 cells174. There is also evidence that CD39+CD25− CD4+ T cells with low levels of PD1 expression suppress IL-17 production in patients with brain inflammation linked to human T lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV1)-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis175. TH17 cells may also be controlled by migration to the small intestine, where they are either eliminated or converted to regulatory-type TH17 cells25. These cells are potent producers of IL-10 and capable of suppressing potentially pathogenic effector T cells. Treg cells that co-express RORγt and FOXP3 also play a suppressive role in intestinal inflammation in mice176. However, the relative contribution of conventional Treg cells, RORγt+FOXP3+ Treg cells or regulatory-type TH17 cells in controlling inflammation in humans is still unclear.

There is an established role for anti-inflammatory cytokines in regulating IL-17. IL-10 limits protective TH17 cell responses during influenza virus infection; Il10−/− mice have enhanced TH17 cell responses and show better survival following infection with influenza virus without excessive inflammation177. IL-10 plays a key role in limiting IL-17-mediated pathology in Lyme arthritis following Borrelia burgdorferi infection178. IL-10 and IFNγ also regulate IL-17 production in the setting of autoimmunity. Regulatory-type TH17 cells that co-express IL-17 and IL-10 are generated under the influence of IL-6 and TGFβ in mice with EAE and these cells are non-pathogenic, whereas TH17 cells that develop in EAE under the influence of IL-1β and IL-23 do not secrete IL-10 and induce potent disease6,27. Co-production of IL-17 with IL-10 may allow TH17 cells to control infection without driving damaging pathology, whereas the inflammatory pathology in autoimmunity may only occur when IL-17 is produced in the absence of IL-10. This also in part explains how the same cell type can be involved in autoimmunity and protective immunity to infection.

Although identified as a TH1 cell-promoting cytokine, IL-27 can regulate TH17 cells. IL-27 suppresses the development of TH17 cells during RSV infection179. In T. gondii infection, IL-27 limits IL-17-mediated chronic immunopathology in the CNS180. The protective effect of IFNβ in EAE and MS is mediated in part by IL-27-mediated suppression of IL-17 production as IFNβ was shown to induce IL-27 expression181. The suppressive effect of IL-27 involves the inhibition of IL-1 and IL-23, which activate TH17 cells and γδT17 cells.

Evidence is emerging of a role for immune-checkpoints in regulating IL-17 production. Treatment of malignancies with anti-PD1/anti-PDL1 or anti-CTLA4 antibodies is associated with the development of autoimmune and inflammatory manifestations182 that can be mediated by IL-17 (ref.183). In mouse models, anti-PD1 mAbs enhanced graft-versus-host disease mediated by TH17 cells and TH1 cells184, whereas intratracheal treatment of lung tumour-bearing mice with anti-PD1 antibodies activated TH17 cells and γδT17 cells185. However, the precise role of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in regulating TH17 cells and γδT17 cells in autoimmunity and infection and the mechanisms involved remain to be defined.

As well as genetic factors, exposures to pathogens and commensal microorganisms have a significant impact on the balance between protective versus pathogenic and regulatory immune responses and the development of autoimmune diseases. Recent interpretations of the hygiene hypothesis have suggested that infection with anti-inflammatory commensal bacteria or helminth parasites can attenuate autoimmune diseases mediated by TH17 cells. Infection with the intestinal helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus suppresses IL-17 production that mediates colitis through IL-4 and IL-10 induction186. Infection of mice with the helminth Fasciola hepatica suppresses TH17 cells and γδT17 cells that mediate EAE through helminth induction of TGFβ187, type 2 cytokines and eosinophils188. In humans, helminth infections can reduce disease severity in patients with MS and this has been linked with IL-35 production by regulatory B cells189.

The development of TH17 cells can be regulated by environmental factors. For example, high-salt conditions promote the development of highly pathogenic TH17 cells that secrete GM-CSF, TNF and IL-2 through activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 (NFAT5) and serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1)190. Furthermore, TH17 cell responses can be negatively regulated downstream of the receptors for IL-17 or IL-23. A20, an inhibitor of signalling downstream of TNF receptors and TLRs, attenuates IL-17-mediated NF-κB and MAPK pathways by deubiquitinating the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6, downstream of the IL-17R191. Moreover, development of TH17 cells can be suppressed by SOCS3, which negatively regulates IL-23-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation192.

Much of the focus on the regulation of IL-17 production has been on TH17 cells. However, innate immune cells, including γδT17 cells and hybrid αβ-γδ T cells, are an important early source of IL-17 in EAE and S. aureus infection8,151. These cells are activated by IL-1β and IL-23, independent of TCR engagement, and may therefore escape the mechanisms that regulate conventional CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells, which often involve suppression of antigen-presenting cell function. Further work will be required to unravel the regulation of IL-17 production by unconventional T cells and their possible role in precipitating autoimmunity.

Conclusions and future perspectives

T cells and innate immune cells that produce IL-17 play key protective roles in immunity to fungal, bacterial, and many viral and parasitic pathogens but can also mediate damaging infection-associated immunopathology or, through the influence of genetic and environmental factors, lead to the development of autoimmune or other chronic inflammatory diseases. IL-17 produced during infection with pathogens or commensal microorganisms, although not specific for self-antigens, may indirectly precipitate or exacerbate autoimmune diseases by priming autoreactive TH17 cells. In fact, IL-17 induced by infection or during sterile inflammation may promote inflammatory responses that are central to many different pathologies, including cardiovascular and neuroinflammatory diseases, neutrophilic asthma, cytokine storms and sepsis, and IL-17 is therefore a drug target in these diseases (Table 2).

All of the currently licensed therapeutics in the IL-17–IL-17R pathway are mAbs. Some have been associated with side effects, including enhanced intestinal inflammation in patients with IBD treated with secukinumab or brodalumab14,163, suicidal thoughts in some patients with psoriasis treated with brodalumab193, and enhanced Candida or upper respiratory tract infections in patients treated with a range of mAbs that target the IL-17–IL-17R pathway11,12,15. Oral bioavailable small molecule drugs (SMDs) have advantages not only regarding cost of production and ease of delivery but also regarding the potential of reduced infection-related side effects. Unlike biologics, which chronically block IL-17 production, SMDs are more likely to transiently blunt IL-17 production, which may break the cycle of inflammation without suppressing the protective effects of IL-17 against infection. However, off-target toxicity can be an issue with some SMDs.

SMDs against RORγt suppress IL-17 production by human and mouse TH17 cells, IL-17+CD8+ T cells, and γδT17 cells and attenuate imiquimod-induced psoriasis in mice194. However, safety issues seem to have halted their clinical progression. SMDs or peptide inhibitors of the IL-17A–IL-17R interaction can block IL-17A signalling in primary human keratinocytes195,196. However, these have not progressed to animal model or clinical studies. Therefore, there is a need for safe and effective oral bioavailable SMDs that block the IL-17–IL-17R pathway.

Because of the dual role of IL-17 in protective immunity and damaging inflammation, an alternative, more targeted approach may be to exploit the host’s natural immunoregulatory mechanisms that selectively suppress IL-17 responses to self-antigens or in specific diseased tissues. Selective induction of Treg cells or cell-based therapies with in vitro-expanded Treg cells have already shown proof-of-principle in animal models and, although yet to deliver major success in human clinical trials, they may provide a safe and effective approach for the treatment of autoimmune diseases in humans.

Acknowledgements

K.H.G.M. acknowledges funding from Science Foundation Ireland (16/IA/4468 and 20/SPP/3685). He is grateful to L. Borkner, D. Jazayeri, C. Ní Chasaide, W. McCormack and J. Fletcher for comments and discussion.

Glossary

- IL-17-secreting γδ T (γδT17) cells

γδT17 cells are CD27−, express the T helper 17 (TH17) cell lineage-defining transcription factor RORγt, and are activated to produce IL-17 in response to IL-1β and IL-23 without TCR activation.

- Tissue resident memory T (TRM) cells

Long-lived memory T cells that infiltrate and persist in epithelial and mucosal tissues and provide the first line of defence against infection and are often categorized by expression of CD69 or CD69 and CD103.

- Natural TH17 cells

A population of RORγt+ and IL-17-producing T cells that develop in the thymus and are poised to rapidly secrete cytokines.

- AIRE

Gene encoding the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) transcription factor, which is essential for promoting tolerance to self-antigens.

- NETosis

A process that leads to the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which bind and help to kill extracellular pathogens.

- Siderophore

High-affinity iron-binding compounds that are secreted by micro-organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, and help them to acquire iron.

- Fate mapping mouse models

Fate mapping approaches in mice, especially those that use genetic approaches, such as barcoding, allow cells of the immune system to be marked so that their descendant can be followed to establish the function of specific cell populations in vivo in health and disease.

- Alternatively activated macrophages

A description historically used to indicate macrophages that have been activated with IL-4 or IL-10 and that are more anti-inflammatory in nature. These cells have also been referred to as ‘M2-like’ macrophages.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks J. Ribot and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Competing interests

K.H.G.M. is a co-founder and shareholder in a Biotech start-up company involved in the development of anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rouvier E, Luciani MF, Mattéi MG, Denizot F, Golstein P. CTLA-8, cloned from an activated T cell, bearing AU-rich messenger RNA instability sequences, and homologous to a herpesvirus saimiri gene. J. Immunol. 1993;150:5445–5456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao Z, et al. Herpesvirus Saimiri encodes a new cytokine, IL-17, which binds to a novel cytokine receptor. Immunity. 1995;3:811–821. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor PR, et al. Activation of neutrophils by autocrine IL-17A-IL-17RC interactions during fungal infection is regulated by IL-6, IL-23, RORγt and dectin-2. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:143–151. doi: 10.1038/ni.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamassia N, et al. A reappraisal on the potential ability of human neutrophils to express and produce IL-17 family members in vitro: failure to reproducibly detect it. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:795. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langrish CL, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutton C, Brereton C, Keogh B, Mills KH, Lavelle EC. A crucial role for interleukin (IL)-1 in the induction of IL-17-producing T cells that mediate autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1685–1691. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lalor SJ, et al. Caspase-1-processed cytokines IL-1beta and IL-18 promote IL-17 production by gammadelta and CD4 T cells that mediate autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2011;186:5738–5748. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutton CE, et al. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2009;31:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribot JC, et al. CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between interferon-gamma- and interleukin 17-producing gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:427–436. doi: 10.1038/ni.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langley RG, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis–results of two phase 3 trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:326–338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reich K, et al. Bimekizumab versus Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385:142–152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warren RB, et al. Bimekizumab versus Adalimumab in plaque psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385:130–141. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mease PJ, et al. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:1329–1339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hueber W, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2012;61:1693–1700. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saunte DM, Mrowietz U, Puig L, Zachariae C. Candida infections in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors and their practical management. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017;177:47–62. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Vinh DC, Casanova JL, Puel A. Inborn errors of immunity underlying fungal diseases in otherwise healthy individuals. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017;40:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee YK, Mukasa R, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Developmental plasticity of Th17 and Treg cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009;21:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basdeo SA, et al. Ex-Th17 (Nonclassical Th1) cells are functionally distinct from classical Th1 and Th17 cells and are not constrained by regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2017;198:2249–2259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Annunziato F, et al. Phenotypic and functional features of human Th17 cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1849–1861. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirota K, et al. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGinley AM, et al. Interleukin-17A serves a priming role in autoimmunity by recruiting IL-1β-producing myeloid cells that promote pathogenic T cells. Immunity. 2020;52:342–356.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baeten D, et al. Anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab in treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]