Abstract

Background:

About 20%–30% of persons with major depression are said to have treatment-resistant depression (TRD) when they do not respond to antidepressants. These people continue to suffer in life and have poor quality of life. Although electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is the most successful option in treating TRD, many people refuse ECT due to various reasons (stigma, the cost involved, and medical complications). Various studies combine treatment options such as psychotherapy, repetitive trans magnetic stimulation, ketamine, and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in an attempt to reduce symptoms for those people suffering from TRD. This study aims to compare the effectiveness of ECT and tDCS in TRD.

Subjects and Methods:

A total of 90 persons suffering from TRD were selected for the study. 46 persons received 6 ECTs and 44 persons received 10 sessions of tDCS. Treatment response was measured using baseline and postassessment scores of Hamilton depression rating scale and clinical global impression. The scores were used to determine the effectiveness of ECT in comparison to tDCS in TRD.

Statistical Analysis:

The mean ± standard deviation was analyzed and paired t-test was used to find the significance of treatment outcome in a group at a 95% confidence interval.

Results:

ECT was found to be more effective than tDCS in the reduction of depressive symptoms. tDCS showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms (P < 0.001). ECT has yet again been proven to be effective in the treatment of TRD.

Conclusion and Discussion:

tDCS is effective in reducing depressive symptoms in persons suffering from TRD. However, ECT is superior in decreasing depressive symptoms in TRD when compared to tDCS.

Keywords: Comparative study, electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial direct current stimulation, treatment-resistant depression

Depression is a major illness that[1] takes a severe toll in a person's psycho-social aspects of life. It is projected by the WHO that by the year 2030, major depression will be the first major cause of the burden of disease in the world. About 70%–80% of people with depression recover with medications and therapy. However, some people do not respond to standard treatment with antidepressants. Depression is considered to be treatment resistant[2] when there is no clinical improvement of symptoms in response to two trials of antidepressants (adequate in dose, duration, and compliance) across different pharmacological classes. Depression is the leading cause of suicide and it can occur across all age groups as indicated by various studies[3,4] across cultures. People who have treatment-resistant depression (TRD) are at higher risk of suicide and hence, it is imperative that the condition is managed at the earliest. It has also shown in various studies that people with TRD experience low quality of life, and account for the loss of productivity with an increased frequency of relapses.[2]

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is considered to be the gold standard for the treatment of severe depression and especially those with TRD when immediate relief from symptoms is expected.[5] Unfortunately, many people refuse ECT due to the stigma associated with it, besides ECT is not advisable to a small percentage of people due to medical reasons. Hence, the search for alternative methods of treatment is important. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, ketamine, and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) are some of the alternative treatment modalities that are being researched for their efficacy as in the treatment for TRD.

tDCS is a noninvasive brain stimulation therapeutic approach[6] used for a variety of neurological and psychiatric conditions. tDCS works on the principle[7] that people with major depressive disorder have the neuropsychological characterization of hypo-activity in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and hyperactivity in the right DLPFC. It is a neuro-modulatory technique that involves directing low-intensity current, directly to the cortical regions thus affecting neuronal networks.[8] Meta-analysis of the therapy[9] has shown that tDCS is effective for major depressive disorder. This noninvasive brain stimulation is cost-effective, portable, and easy to administer[10] and has proven to be effective in studies in the treatment of major depression in medication-free randomized studies.[10] Studies involving tDCS in TRD are very few and one double-blinded, sham-controlled study with antidepressants[11] showed that although there was no noticeable difference between treatment and sham group, tDCS was associated with an increase in positive emotions and a decrease in negative emotions.

People suffering from TRD usually show poor compliance with conventional medicines because they do not find it beneficial to them. Although ECT is considered to be the gold standard procedure for TRD, most people are hesitant to opt for it fearing stigma associated with the whole treatment process; however, they are open to noninvasive safer methods of treatment. Hence, other options including tDCS must be tested for its efficacy in comparison to ECT. There are the availability of studies that compare the effectiveness of ECT with that of repetitive trans magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and Deep brain stimulation, but none of the studies compare the effectiveness of ECT and tDCS in TRD. Considering the various advantages of tDCS such as easy administration, portability, low cost, and minimal side effects, it can be considered as a viable alternative to ECT. This study aims to compare the effects of ECT and tDCS in the treatment of TRD. It aims to find if tDCS is as effective as ECT in the clinical improvement of depressive symptoms in persons suffering from TRD.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. This study was approved by the internal ethics committee, Radianz health care, and the research center (Registration number–4/2018). This study was a prospective parallel randomized controlled, open-label, noninferiority/superiority trial. Persons who visited the hospital and were diagnosed with major depressive disorder according to DSM 5 and who did not show response, despite treatment with drugs from two different pharmacological classes of antidepressants, each used in an adequate dose for an adequate period were identified to have TRD[2] and they were selected for the study. The sampling mode was proportionate stratified random sampling. All participants provided informed consent after receiving a detailed description of the study.

inclusion criteria

Persons in the age group of 18–60 years were selected for the study

Persons who met the criteria of major depressive disorder according to DSM 5 and who were refractory to trials of antidepressants across two different pharmacological classes for 6 weeks (adequate in dose, duration, and compliance), were identified to have TRD[2] and hence included.

Exclusion criteria

Persons suffering from bipolar affective disorder or schizophrenia or depression with psychotic symptoms were excluded from the study

People with neurological conditions like intellectual disability or other neuro-developmental conditions were also excluded from the study

Persons using alcohol or other psychoactive substances including nicotine were not included in the study

Pregnant and lactating women were also excluded from the study.

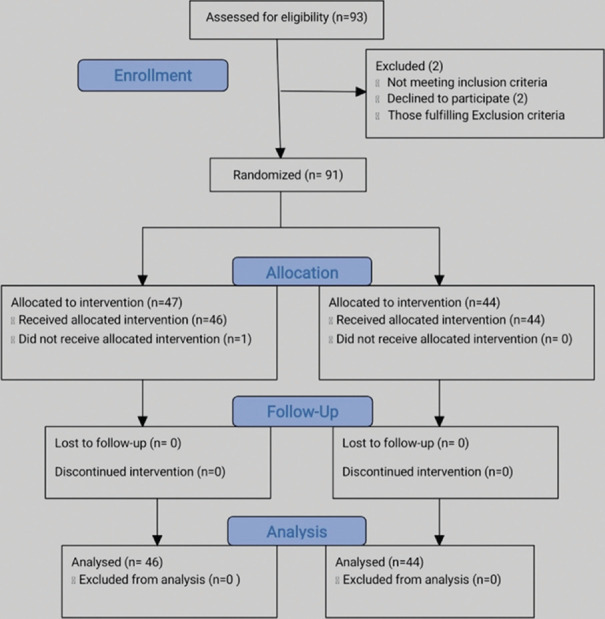

A total of 93 people were selected after assessing for eligibility and were approached to participate in the study for 6 months from July 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018. Two people declined to participate and 91 people were randomized by block randomization technique using a software-generated sequence. 47 subjects were selected to receive ECT and 44 participants were selected to receive tDCS. Due to the nature of the intervention, the physician and investigator could not be blinded while the statistician was blinded in the analysis of the study. Fitness for ECT and tDCS procedure was procured. The baseline depression scores were recorded using the Hamilton depression rating scale (HAM-D) and clinical global impression (CGI) severity scale, before the start of the treatment. Treatment response is ascertained if there is an improvement from their HAM-D baseline score at the rate of more than or equal to 50% at the end of 2 weeks [Figure 1]. The participants received a steady dose of various classes of antidepressants such SSRIs and SNRIs from 4 weeks before the study and throughout the study and there was no change in the medicines during the study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart

All participants included in the study were admitted to the hospital during the treatment. One person who was selected to receive ECT did not turn up for admission and hence was dropped from the study. Since the duration of the study was 2 weeks, it was decided that 6 ECTs and 10 tDCS were planned to be administered to the participants in the stipulated time.

Modified ECT was given three times a week, on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, up to a total of 6 treatments over 2 weeks. Persons who were to be given ECT were informed to fast overnight. ECT procedure was started at 6 am. Muscle relaxant and anesthesia were given to the patient and a stimulus dose titration procedure was performed at the first treatment to determine the seizure threshold.[12] Subsequent ECTs were given accordingly. The patients were treated with a standard brief-pulse ECT device with bitemporal electrode placement.[12] Post ECT procedures were duly followed and the patient was kept in continuous observation throughout the treatment. Postassessment using HAM-D was taken at the end of the 6th ECT.

Ten sessions of tDCS were given over 2 weeks, with patients receiving treatment daily from Monday to Friday except on weekends. Patients were seated in a comfortable position and awake during the tDCS procedure. The anodal electrode was placed in the left DLPFC and the cathodal electrode was placed over the supraorbital region. Stimulation was given at 1–2 mA for 20 min. Patient was kept in continuous observation throughout the treatment. Postassessment of depressive symptoms was taken after the end of the 10th session using HAM-D. 2 persons in the tDCS arm complained of mild tingling sensations at the placement of the electrode during the first session. The sensation was transient and there were no adverse effects reported.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Inc. Released 2008. SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0. (Chicago: SPSS Inc.). The various details pertaining to socio-demographic details were analyzed for normal distribution. The mean ± standard deviation was analyzed and paired t-test was used to find the significance of treatment outcome in a group at 95% confidence interval. P values computed by Kolmogrov–Smirnov test for HAM-D score and CGI scoring scale evaluated in the patients before therapy, and at the end of therapy. Independent sample t-test was done to find the significant difference between means of the two arms of treatment, with significance at <0.05 indicating a significant difference between the variables.

RESULTS

The sociodemographic details of the participants were found to be normally distributed across both the arms of the study, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic details

| ECT arm | thCS arm | Sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 23 | 15 | P=0.094 |

| Female | 23 | 19 | NS | |

| Age group | <30 yrs | 11 | 6 | P=0.131 |

| 31-50 yrs | 28 | 24 | NS | |

| >51 yrs | 7 | 14 | ||

| Socio-economic status | Low | 17 | 15 | P=0.924 |

| Middle | 20 | 19 | NS | |

| High | 9 | 10 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 35 | 36 | P=0.343 |

| Unmarried | 11 | 6 | NS | |

| Education | School | 14 | 14 | P=0.891 |

| Graduate | 21 | 18 | NS | |

| Postgraduate | 11 | 12 |

The results as shown in Table 2 indicate that ECT produced a significant reduction in depression scores as measured by HAM-D and CGI. Similarly, tDCS has been proven to produce significant symptom reduction (P = 0.000) as evidenced in Table 3 by the mean score reduction in HAM-D and CGI.

Table 2.

Paired t-test results for electroconvulsive therapy

| Group | n | Mean±SD | Mean difference | Paired t value | Stat result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAM-D score | |||||

| Pre | 46 | 18.98±1.949 | 10.891 | 29.695 | P=0.000 (significant) |

| Post | 46 | 8.09±3.032 | |||

| CGI severity | |||||

| Pre | 46 | 5.13±0.885 | 3.174 | 27.994 | P=0.000 (significant) |

| Post | 46 | 1.96±0.729 |

HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; CGI – Clinical global impression; SD – Standard deviation

Table 3.

Paired t-test results for transcranial direct current stimulation

| Group | n | Mean±SD | Mean difference | Paired t value | Stat result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAM-D score | |||||

| Pre | 44 | 19.23±2.140 | 3.05 | 6.65 | P=0.000 (significant) |

| Post | 44 | 16.18±2.160 | |||

| CGI severity | |||||

| Pre | 44 | 5.45±0.791 | 1.47 | 9.64 | P=0.000 (significant) |

| Post | 44 | 3.98±0.63 |

HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; CGI – Clinical global impression; SD – Standard deviation

On comparing the scores between the ECT and tDCS arm, the mean baseline HAM D scores for depression was 18.98 for the ECT group, and for the tDCS group, it was 19.23. There was no significant difference between the mean baseline scores (P = 0.565) for HAM D and CGI severity scale (P = 0.071) as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Independent sample t-test results for baseline score (electroconvulsive therapy vs. transcranial direct current stimulation group)

| Group | n | Mean±SD | Mean difference | t | Stat result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAM-D score | |||||

| ECT | 46 | 18.98±1.95 | 0.25 | 0.580 | P=0.565 (not significant) |

| tDCS | 44 | 19.23±2.14 | |||

| CGI severity score | |||||

| ECT | 46 | 5.13±0.89 | 0.32 | 1.81 | P=0.071 (not significant) |

| tDCS | 44 | 5.45±0.79 |

tDCS – Transcranial direct current stimulation; ECT – Electroconvulsive therapy; HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; CGI – Clinical global impression; SD – Standard deviation

The mean postassessment scores for ECT and tDCS as shown in Table 5 indicates that the ECT arm produced a greater amount of symptom reduction with a mean score of 10.09 in HAM D and 1.96 in CGI severity scale with a significant difference from the tDCS arm (P = 0.001).

Table 5.

Independent sample t-test results for postassessment scores (electroconvulsive therapy vs. transcranial direct current stimulation group)

| Group | n | Mean±SD | Mean difference | t | Stat result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAM-D score | |||||

| ECT | 46 | 10.09±3.03 | 6.09 | 11.02 | P=0.001 (significant) |

| tDCS | 44 | 16.18±2.16 | |||

| CGI severity score | |||||

| ECT | 46 | 1.96±0.73 | 2.02 | 14.07 | P=0.001 (significant) |

| tDCS | 44 | 3.98±0.63 |

tDCS – Transcranial direct current stimulation; ECT – Electroconvulsive therapy; HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; CGI – Clinical global impression; SD – Standard deviation

DISCUSSION

This study hoped to compare the effectiveness of ECT and tDCS in TRD. The results indicate that tDCS has a significant antidepressant effect, but it is not superior or equal to the standard ECT.

The results clearly indicate that tDCS has significant symptoms reduction in TRD as shown by similar studies.[13,14] As with previous studies,[11] people undergoing tDCS had minimal side effects with only two complaining of mild tingling during their first session. Various studies are evolving that encourage alternative methods like tDCS for TRD.[15] This study confirms that ECT is still the gold standard in the treatment of TRD.[16,17] However, the effectiveness of tDCS cannot be ignored especially in the geriatric population,[18,19] and for young adolescents, as noted in similar studies.[20] Both these populations are considered to be vulnerable. This study is another attempt to find alternatives to ECT like rTMS, deep brain stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of TRD.

As discussed earlier, most people feel hesitant to opt for ECT for various reasons.[21] TRD is a challenging clinical condition and response is further hindered by patients becoming demotivated and demoralized due to the lack of improvement through various pharmacological and therapeutic measures. This calls for integrated therapeutic strategies that are being studied extensively.[22] This study could form the basis for further studies that analyze the long-term effects of tDCS, especially in the context of TRD.

CONCLUSION

tDCS has significant improvement in depressive symptoms with patients suffering from TRD. ECT is superior to its antidepressant effects in comparison to tDCS. tDCS could be suggested as a suitable option for patients who are not fit to undergo ECT and are looking for alternatives. tDCS is a safe option that could be administered in sessions on an outpatient basis.

The authors accept that given the small prevalence rate of TRD this sample size was adequate for the present comparative study. Long-term effects of repeated sessions of tDCS could be further analyzed through longitudinal studies, especially concerning the geriatric, adolescent, and young adult population.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet. 2018;392:2299–312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31948-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little A. Treatment-resistant depression. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boldrini M, Mann JJ. USA: Academic Press, Elsevier Inc; 2015. Depression and Suicide. In: Neurobiology of Brain Disorders: Biological Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders; pp. 709–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anastasia A, Solmi M, Fornaro M. Encyclopedia of Biomedical Gerontology. USA: Academic Press, Elsevier Inc; 2019. Suicide; pp. 307–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner RD, Reti IM. Key updates in the clinical application of electroconvulsive therapy. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29:54–62. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2017.1309362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lefaucheur JP, Antal A, Ayache SS, Benninger DH, Brunelin J, Cogiamanian F, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128:56–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2016.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimm S, Beck J, Schuepbach D, Hell D, Boesiger P, Bermpohl F, et al. Imbalance between left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in major depression is linked to negative emotional judgment: An fMRI study in severe major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:369–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunoni AR, Boggio PS, De Raedt R, Benseñor IM, Lotufo PA, Namur V, et al. Cognitive control therapy and transcranial direct current stimulation for depression: A randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2014;162:43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalu UG, Sexton CE, Loo CK, Ebmeier KP. Transcranial direct current stimulation in the treatment of major depression: A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1791–800. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711003059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boggio PS, Rigonatti SP, Ribeiro RB, Myczkowski ML, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A, et al. A randomized, double-blind clinical trial on the efficacy of cortical direct current stimulation for the treatment of major depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:249–54. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707007833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumberger DM, Tran LC, Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE, Daskalakis ZJ. A randomized double-blind sham-controlled study of transcranial direct current stimulation for treatment-resistant major depression. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:74. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellner CH, Fink M, Knapp R, Petrides G, Husain M, Rummans T, et al. Relief of expressed suicidal intent by ECT: A consortium for research in ECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:977–82. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nitsche MA, Boggio PS, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Treatment of depression with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): A review. Exp Neurol. 2009;219:14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dell’Osso B, Zanoni S, Ferrucci R, Vergari M, Castellano F, D’Urso N, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation for the outpatient treatment of poor-responder depressed patients. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:513–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holtzheimer PE. Management of treatment-resistant depression: Somatic nonpharmacological therapies. Management of Treatment-Resistant Major Psychiatric Disorders. 2012:49–73. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor SM. Electroconvulsive therapy, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and possible neurorestorative benefit of the clinical application of electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2008;24:160–5. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181571ad0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rapinesi C, Kotzalidis GD, Curto M, Serata D, Ferri VR, Scatena P, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy improves clinical manifestations of treatment-resistant depression without changing serum BDNF levels. Psychiatry Res. 2015;227:171–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunoni AR, Nitsche MA, Bolognini N, Bikson M, Wagner T, Merabet L, et al. Clinical research with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): Challenges and future directions. Brain Stimul. 2012;5:175–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Rooij SJ, Riva-Posse P, McDonald WM. The efficacy and safety of neuromodulation treatments in late-life depression. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2020;7:337–48. doi: 10.1007/s40501-020-00216-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Croarkin PE. 17.4 Noninvasive brain stimulation for adolescent treatment-resistant depression. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:S284. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teh SP, Helmes E, Drake DG. A western Australian survey on public attitudes toward and knowledge of electroconvulsive therapy. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2007;53:247–73. doi: 10.1177/0020764006074522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: Therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369–88. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S29716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]