Key Points

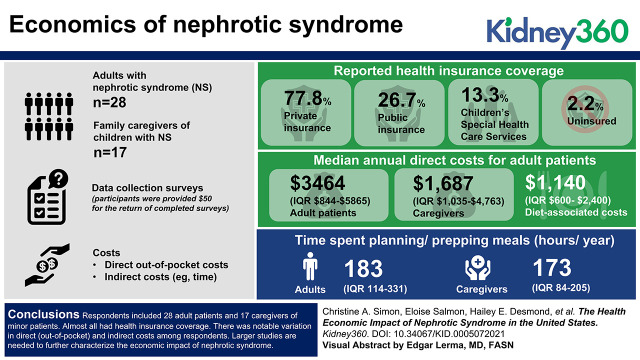

Median annual direct costs (including medication, diet, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and clinic visits) were $3464 (interquartile range [IQR] $844–$5865) for adult patients and $1687 (IQR $1035–$4763) for caregivers.

The time spent planning/prepping meals was 183 h/yr (IQR 114–331) for adults and 173 h/yr (IQR 84–205) for caregivers.

Providers can better understand the burden of living with nephrotic syndrome, consider barriers when treating patients, and develop supportive strategies.

Keywords: glomerular and tubulointerstitial diseases, absenteeism, food selection, health economics, low sodium diet, nephrotic syndrome, patient costs, patient experience, United States

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a rare kidney syndrome with high morbidity. Although a common contributor to the burden of chronic kidney disease, the direct and indirect costs of NS to patients and family caregivers are unrecognized. The objective was to characterize the direct and indirect costs of NS to patients.

Methods

Adults with NS and family caregivers of children with NS were eligible to participate if they had a diagnosis of primary NS, had disease for at least 1 year, and had no other severe health conditions. Data-collection surveys were generated with input from the Kidney Research Network Patient Advisory Board, and surveys were mailed to the eligible participants. Participants were provided $50 for the return of completed surveys. Costs were defined as either direct out-of-pocket costs or indirect costs (e.g., time). Descriptive statistics, including percentage and median (interquartile range [IQR]) are reported.

Results

Respondents included 28 adult patients and 17 caregivers of patients who were minors. Reported health insurance coverage included 35 (78%) with private insurance, 12 (27%) with public insurance, six (13%) with Children’s Special Health Care Services, and one (2%) uninsured. Median annual direct costs were $3464 ($844–$5865) for adult patients and $1687 (IQR $1035–$4763) for caregivers. Of these costs, diet-associated costs contributed $1140 (IQR $600–$2400). The most substantial indirect cost was from the time spent planning/prepping meals (adults: 183 h/yr [IQR 114–331]; caregivers: 173 h/yr [IQR 84–205]).

Conclusions

Adults and caregivers of children with NS face substantial disease-related direct and indirect costs beyond those covered by insurance. Following replication, the study will help health care providers, systems, and payers gain a better understanding of the financial and time burden incurred by those living with NS, consider barriers when treating patients, and develop supportive strategies.

Introduction

The clinical diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome (NS), defined by hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, edema, and proteinuria, impacts individuals of all ages. Primary causes of NS are minimal change disease, focal glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), membranous nephropathy, and hereditary nephropathies. When systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus or systemic lupus erythematosus cause NS, it is labeled secondary NS (1). Primary NS was the focus of this study. In children, minimal change nephropathy is the most common subtype of primary NS, with an incidence of approximately 2 per 100,000 in the United States (2). In adults, the incidence of primary NS has been estimated at 3 per 100,000, with membranous nephropathy and FSGS each accounting for 30%–35% of NS cases, and minimal change disease and immunoglobulin A nephropathy each accounting for approximately 15% of cases (3).

For all subtypes, primary NS is a chronic health condition; it may be relapsing and remitting or progressive to kidney failure. Management strategies include disease-modifying therapies such as immunosuppressive agents (e.g., cyclosporin, tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and rituximab), adjunctive therapies, and diet modifications (4).

There is a paucity of literature addressing the time and financial burdens of chronic conditions such as NS. However, a health economics study focused on phenylketonuria illustrated that there are significant direct (out-of-pocket) costs and indirect (time and opportunity loss) burdens associated with a condition whose management also includes both health care visits and lifestyle changes, including dietary modification (5). As a result, our study aimed to characterize the direct (out-of-pocket) and indirect costs to patients and families affected by NS to understand better the financial implications and burden of chronic illness and to guide strategies to address these issues.

Materials and Methods

Survey Development

The Kidney Research Patient Advisory Board (PAB) (5) had a key role in survey development. The PAB is comprised of volunteer patients and family caregivers and provides strategic leadership to the Kidney Research Network regarding perspectives on selected research, educational, and network initiatives. PAB members reflected on the costs of NS and were asked: “How has kidney disease impacted your/your family’s finances?” From this discussion, NS cost-related concepts were defined and used to modify “The financial and time burden associated with phenylketonuria (PKU) treatment in the United States survey,” with permission (6). Two 240-item surveys were designed: one for adults aged ≥18 years living with NS, and one for family caregivers of children aged <18 years living with NS. A summary of the survey content can be found in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Recruitment

Survey respondents for this pilot study were recruited within nephrology practices, website advertisements on kidneyresearchnetwork.org and umhealthresearch.org, electronic study invitations through the Kidney Research Network registries, and Facebook NS support groups.

Eligibility

To be eligible for this study, participants needed to be ≥18 years old, have primary FSGS, minimal change disease, IgM nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, or childhood-onset idiopathic NS for at least 1 year, or be a caregiver of a child who has any of the above conditions for at least 1 year, and reside in the United States. NS must have been active on the basis of abnormal proteinuria or NS-related therapy within the past 12-month period. Individuals with CKD stages 1–5 were eligible, as were individuals post transplant or receiving chronic dialysis. Exclusion criteria included non-English-speaking individuals because the surveys were only available in English, secondary NS, and co-existing chronic illnesses such as diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, etc. that may impart additional economic impact nondistinguishable from NS.

Eligible participants received a paper survey and postage-paid return envelope and were asked to return the survey within 1 month. The survey took 60–90 minutes to complete. Upon return of a completed survey, participants received a $50 honorarium. The recruitment goal was 25 adults and 25 family caregivers with completed surveys.

Data Organization, Classification, and Analysis

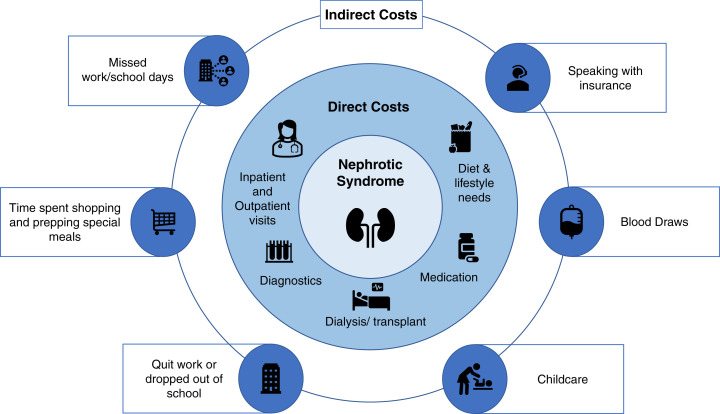

Data from completed surveys were entered into the study REDCap database by a member of the study team. Costs were classified as either direct or indirect. Direct costs included out-of-pocket inpatient, outpatient, surgery, drug, and other health care service costs, whereas indirect costs were related to time lost due to NS, such as loss of productivity at work (7) (Figure 1). Indirect time costs were monetized using the average hourly earnings of January 2021 from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, with 1 day measured as 8 hours lost in average hourly earnings (8). Descriptive statistics using percentage, median, and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of patient/family indirect and direct costs associated with nephrotic syndrome. These costs exclude costs to insurance plans.

Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved as exempt by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. Completion of the survey served as consent to participate in this study.

Results

Overall, 89 adults with NS expressed interest in participation, of whom 48 were eligible and 28 returned surveys. With regard to caregivers, 81 expressed interest in participation, of whom 29 were eligible and 17 returned surveys. A summary of the patient demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Of the 28 adults with NS and 17 family caregivers who responded to our survey, 34 (76%) were women and 35 (78%) were non-Hispanic White. Thirty-five (78%) respondents had private insurance only, 12 (27%) had public insurance, six (13%) had Children’s Special Health Care Services (CSH), and one (2%) paid for all costs out of their own pocket. In addition, 17 (38%) participants had a household income of ≤$50,000, and 40 (89%) patients had had NS for more than 3 years. The study included nine (20%) patients with ESKD, defined as dialysis or kidney transplant dependent.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Demographics | All (N=45) | Respondent Type | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult (N=28), n (%) | Family Caregiver (N=17), n (%) | ||

| Women | 34 (76) | 20 (71) | 14 (82) |

| Race and ethnicity of respondent | |||

| White, not of Hispanic origin | 35 (78) | 20 (71) | 15 (88) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 (7) | 3 (11) | 0 (0) |

| Black, not of Hispanic origin | 2 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (6) |

| Hispanic | 4 (9) | 4 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Mixed | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Age at survey completion, yr | |||

| 18–29 | 13 (29) | 12 (36) | 1 (6) |

| 30–39 | 11 (24) | 6 (21) | 5 (29) |

| 40–59 | 16 (36) | 6 (21) | 10 (59) |

| 60–79 | 5 (11) | 4 (14) | 1 (6) |

| Education of respondent | |||

| High school/GED | 10 (22) | 6 (21) | 4 (24) |

| 2-year college/trade school/college certificate | 10 (22) | 7 (25) | 3 (18) |

| 4-year college | 16 (36) | 13 (47) | 3 (18) |

| Master’s degree | 5 (11) | 1 (6) | 4 (24) |

| Doctoral or professional degree (e.g., MD, PhD, JD) | 4 (9) | 1 (6) | 3 (18) |

| Employment status of respondent | |||

| Employed full time (≥40 hours per week) | 21 (47) | 13 (47) | 8 (50) |

| Employed part time (<40 hours per week) | 10 (22) | 7 (25) | 3 (19) |

| Not employed outside of the home | 14 (31) | 8 (29) | 6 (31) |

| Insurance | |||

| Private insurance | 35 (78) | 23 (82) | 12 (75) |

| Public insurance | 12 (27) | 7 (25) | 5 (42) |

| Children’s Special Health Care Services | 6 (13) | 1 (4) | 5 (42) |

| Self-pay or out-of-pocket | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Household income, US$ | |||

| ≤15,000 | 3 (7) | 3 (11) | 0 (0) |

| >15,000 to 25,000 | 4 (9) | 2 (7) | 2 (12) |

| >25,000 to 35,000 | 3 (7) | 3 (11) | 0 (0) |

| >35,000 to 50,000 | 7 (16) | 4 (14) | 3 (18) |

| >50,000 to 75,000 | 7 (16) | 5 (18) | 2 (12) |

| >75,000 | 21 (47) | 11 (39) | 10 (59) |

Table 2.

Patient disease characteristics

| Disease Characteristics | All (N=45) | Patient Type | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult (N=28), n (%) | Childa (N=17), n (%) | ||

| Diagnosis | |||

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | 18 (40) | 12 (43) | 6 (38) |

| Minimal change disease, IgM nephropathy, childhood-onset nephrotic syndrome, not otherwise specified | 22 (49) | 11 (39) | 11 (65) |

| Membranous nephropathy | 4 (9) | 4 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Duration of disease, yr | |||

| 1–2 | 5 (11) | 4 (14) | 1 (6) |

| 3–5 | 13 (29) | 6 (21) | 7 (41) |

| 6–10 | 11 (24) | 7 (25) | 4 (25) |

| 11+ | 16 (36) | 11 (39) | 5 (29) |

| ESKD | 9 (20) | 7 (25) | 2 (12) |

Parents filled out disease characteristics for their children because only those aged ≥18 years could fill out the survey.

Annual Direct Costs

Median annual direct costs were $3464 ($844–$5865) for adult patients and $1687 (IQR $1035–$4763) for caregivers. Of these costs, diet-associated costs contributed $1140 (IQR $600–$2400) for adults and $750 (IQR $388–$1008) for family caregivers. Furthermore, transplant-associated costs (n=3, 11% of adults, and n=1, 6% of family caregivers) contributed $3350 (IQR $1900–$5275) for adults and $1800 for family caregivers (Table 3). All but one participant had insurance for health care costs. One family caregiver participant paid $120 per year for all health care related to NS and attributed this low out-of-pocket cost residual cost burden to supplementary insurance with CSH (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 3.

Annual direct out-of-pocket costs (US$)a for medical, diet, and other special products

| Cost Category | Adult (N=28) | Family Caregiver (N=17) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Reporting, n (%) | Costs (US$), Median (Interquartile Range) | # Reporting, n (%) | Costs (US$), Median (Interquartile Range) | |

| Diagnosis | 16 (57) | 725 (89–3445) | 9 (53) | 140 (40–1000) |

| Total medication | 25 (89) | 210 (75–484) | 16 (94) | 54 (22–210) |

| Dialysis | 5 (18) | 0 (0–0) | 2 (12) | 850 (475–1225) |

| Kidney transplant | 3 (11) | 3350 (1900–5275) | 1 (6) | 1800 (1800–1800) |

| Diet | 16 (57) | 1140 (600–2400) | 12 (71) | 750 (388–1008) |

| Special producta | 16 (57) | 38 (0–73) | 13 (77) | 26 (0–50) |

| Emergency room | 4 (14) | 330 (160–521) | 1 (6) | 10 (10–10) |

| Hospitalization | 6 (21) | 918 (178–1485) | 4 (24) | 150 (83–1325) |

| Nephrology visit | 26 (93) | 80 (41–140) | 16 (94) | 76 (54–110) |

| Primary care provider visit | 19 (68) | 42 (23–92) | 15 (88) | 40 (21–83) |

| Specialist visitb | 9 (32) | 165 (72–360) | 6 (35) | 95 (39–485) |

| Psychiatry visit | 4 (14) | 15 (8–25) | 0 (0) | — |

| Other servicesc | 8 (29) | 90 (62–186) | 3 (18) | 70 (50–1135) |

| Annual total costs per patient | 28 (100) | 3464 (844–5865) | 16 (94) | 1687 (1035–4763) |

Special products include blood pressure monitors, urine dipsticks, and other cleaning products.

Specialists include geneticists, cardiologists, dermatologists, pulmonologists, and optometrists.

Other services include nutrition counseling, genetic counseling, behavioral therapy, social work, and the dentist.

Annual Indirect Costs

The most substantial indirect cost was time spent planning/prepping meals (adults: 183 hours/year [IQR 114–331]; caregivers: 173 h/yr [IQR 84–205]). Adults also spent more time visiting special services (median of 19 h/yr [IQR 17–30 h/yr]), whereas family caregivers spent a median of 3 h/yr (IQR 2.4–6.5 h/yr). These special services included nutrition counseling, behavioral therapy, social work, the dentist, and more. The number of annual blood draws was 12 (IQR 8–13) for adults and five (IQR 3–7 draws) for children (Table 4). Indirect costs from lost opportunities were reported by both adults and family caregivers. Adults reported premature discontinuation of employment (n=4, 14%), premature discontinuation of education (n=3, 11%), and decline of promotion at work (n=2, 7%) due to kidney disease. Family caregivers reported premature discontinuation of education (n=1, 6%) and decline of promotion at work (n=1, 6%) due to their child’s kidney disease. In addition, children of the family caregivers missed a median of four school days (IQR 0–13 school days) due to NS.

Table 4.

Annual indirect costs of nephrotic syndrome

| Activity | Adult (N=28) | Family Caregiver (N=17) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Reporting, n (%) | Time Reported Median (Interquartile Range) | Time Costs (US$) Median (Interquartile Range)a | # Reporting, n (%) | Time Reported Median (Interquartile Range) | Time Costs (US$) Median (Interquartile Range)a | |

| Emergency room, h | 4 (14) | 7.4 (5–10) | 222 (150–300) | 1 (6) | 5 (5–5) | 150 (150–150) |

| Hospitalization, d | 7 (25) | 4 (2–13) | 960 (480–3121) | 4 (24) | 2.5 (1–4) | 600 (240–960) |

| Nephrology visit, h | 26 (93) | 2.5 (2–4) | 75 (60–120) | 16 (94) | 3.5 (2–4.1) | 105 (60–123) |

| Primary care provider visit, h | 22 (79) | 1.3 (1–2) | 39 (30–60) | 16 (94) | 1.5 (1–2.1) | 45 (30–63) |

| Specialists visitb, h | 11 (39) | 4.5 (3–7) | 135 (90–210) | 7 (41) | 4 (1.8–5.5) | 120 (54–165) |

| Other services visitc, h | 7 (25) | 19 (17–30) | 570 (510–900) | 3 (18) | 3 (2.4–6.5) | 90 (72–195) |

| Traveling and shopping for special foods, h | 14 (50) | 19 (3–48) | 570 (90–1440) | 12 (71) | 12 (4.6–45) | 360 (138–1350) |

| Planning and preparing special meals, h | 13 (46) | 183 (114–331) | 5492 (3421–9933) | 10 (59) | 173 (84–205) | 5,204 (2509) |

| Speaking with insurance, h | 26 (93) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–30) | 17 (100) | 0.5 (0–1.5) | 15 (0–45) |

| Work reduction, h | 6 (21) | 9 (4–18) | 270 (120–540) | 2 (12) | 10 (7.5–12.5) | 300 (225–375) |

| Work absentee, d | 28 (100) | 1 (0–12) | 240 (0–2881) | 15 (88) | 5 (0–9) | 1200 (0–2161) |

| School absentee, d | 8 (29) | 4 (2–9) | — | 0 (0) | — | — |

| Blood draws | 26 (93) | 12 (8–13) | 360 (240–390) | 16 (94) | 5 (3–7) | 135 (90–195) |

$30.01 mean hourly earnings 2021 in US$.

Specialists include geneticists, cardiologists, dermatologists, pulmonologists, and optometrists.

Other services include nutrition counseling, genetic counseling, behavioral therapy, social work, and the dentist.

Diet

Diet-related responses are summarized in Table 5. Fifteen (71%) adults and 14 (88%) family caregivers reported that they or their child partially or fully adhere to their special diets. A total of 13 (68%) adults and 13 (81%) family caregivers acknowledged that this special diet is very or extremely important. Sixty-two percent (n=8) of adults and 75% (n=6) of family caregivers responded that special diet products were difficult to acquire due to availability, whereas other factors such financial reasons, distance, and time played a role in complying with the diet. Although few adults (n=5, 25%) asserted that following a special diet was difficult or very difficult, more family caregivers (n=7, 44%) claimed that it was difficult for their child to follow this diet. All reported that following the special diet was difficult due to the burdens of the diet itself (100%). However, 16 (94%) family caregivers reported that it is not difficult or somewhat difficult to meet their child’s needs, and 11 (65%) family caregivers claimed that their child needed no more or a little more care than other children. Through the free-text survey section, those with difficulty purchasing items and following the special diet reported specific reasons for this difficultly. One participant explained, “I’m unemployed due to the disease and the sole income earner. Food banks do not cater to special diets.” Another participant discussed loss of social opportunity for the child at school because the child cannot eat the same food as other children in the cafeteria (see Supplemental Table 3).

Table 5.

Difficulty with nephrotic syndrome diet

| Question about Diet | Adult, n (%) | Family Caregiver, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Have you/your child followed a special diet? | ||

| # of respondents | 21 | 16 |

| No | 6 (29) | 2 (13) |

| Yes, partially | 11 (52) | 8 (50) |

| Yes, fully or daily | 4 (19) | 6 (38) |

| How difficult is it to obtain any part of the special diet? | ||

| # of respondents | 21 | 16 |

| Not difficult | 8 (38) | 8 (50) |

| Somewhat difficult | 6 (29) | 7 (44) |

| Difficult | 5 (24) | 0 (0) |

| Extremely difficult | 2 (10) | 1 (6) |

| Why is it difficult to get special diet products? | ||

| # of respondents | 13 | 8 |

| Financial reasons | 6 (46) | 3 (38) |

| Availability of product | 8 (62) | 6 (75) |

| Distance | 2 (15) | 1 (13) |

| Time | 4 (31) | 3 (38) |

| How difficult is it for you/ your child to follow the recommended diet? | ||

| # of respondents | 20 | 16 |

| Not difficult | 3 (15) | 4 (25) |

| Somewhat difficult | 12 (60) | 5 (31) |

| Difficult | 4 (20) | 4 (25) |

| Very difficult | 1 (5) | 3 (19) |

| Why are you/your child not able to closely follow the recommended diet? | ||

| # of respondents | 4 | 4 |

| Cost of diet | 1 (25) | 2 (50) |

| Diet is burdensome | 3 (75) | 4 (100) |

| Emotional or social factors | 2 (50) | 1 (25) |

| How important do you feel this diet is for your/your child’s health? | ||

| # of respondents | 19 | 16 |

| Somewhat important | 1 (5) | 1 (6) |

| Important | 5 (26) | 2 (13) |

| Very important | 7 (37) | 8 (50) |

| Extremely important | 6 (32) | 5 (31) |

Comparison of non-ESKD to ESKD Costs

Within this study sample, both ESKD adults and caregivers of ESKD children had more direct costs than non-ESKD adults and caregivers of non-ESKD children (Supplemental Tables 4–7). Non-ESKD adults faced more direct costs than caregivers of non-ESKD children, with a median of $2594 (IQR $728–$4881) compared with $1217 (IQR $608–$4214). However, ESKD adults had fewer direct costs than caregivers of ESKD children, with a median of $3960 (IQR $3464–$7109) compared with $4985 (IQR $4343–$5628). In addition, non-ESKD adults spent 182.5 h/yr (IQR 121.7–285.1 h/yr) planning and prepping special meals, and caregivers of non-ESKD children also spent 182.5 h/yr (IQR 91.3–250.9 h/yr) planning and prepping special meals. Whereas ESKD adults spent 228 h/yr (IQR 160–297 h/yr), a single caregiver, whose child had ESKD, spent 150 h/yr.

Influence of Insurance Status

Direct out-of-pocket costs also varied by insurance type (Supplemental Tables 8 and 9). Among non-ESKD adults, individuals with private insurance alone had higher medication, hospitalization, and visit costs that non-ESKD adults with at least some public insurance. Similarly, caregivers of non-ESKD children with private insurance alone had higher medication costs than those with public insurance.

Discussion

Adults and caregivers of children with NS face substantial disease-related direct and indirect costs far exceeding costs covered by insurance. Adult patients experienced more costs when compared with pediatric patients, with median annual direct cost of $3364 (IQR $844–$5865). Annual diet costs were a significant proportion of this cost for both adult patients $1140 (IQR $600–$2400) and caregivers $750 (IQR $388–$1008) and required a time commitment of 183 h/yr (IQR 114–331 h/yr) for adults and 173 h/yr (IQR 84–205 h/yr) for caregivers. The time commitment was primarily due to limited availability of recommended food products, thereby necessitating home-prepared meals; likewise, respondents found that adequately tasty options that met their restrictions (e.g., low sodium) often cost more (see Supplemental Table 3) Although few adults (25%) asserted that following a special diet was very difficult, more family caregivers (44%) claimed that it was very difficult for their child to follow this diet. Lastly, adults and children who had reached ESKD had more direct out-of-pocket costs than those who had not reached ESKD. This variation in cost burden by severity of disease highlights the heterogeneity of the primary NS population, and future work should continue to characterize the experiences of both ESKD and non-ESKD individuals.

The children’s cost may be in part less than adults due to the availability of CSH. This program is provided by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services as part of Title V of the Federal Social Security Act. Similar programs are also present in other states. The benefits include coverage of specialty medical bills and co-pays and deductibles from private or public insurance for children aged <21 years with at least one of more than 2700 chronic health conditions (9). A qualifying diagnosis is dependent on the type, severity, chronicity of medical condition, and the need for pediatric specialty care (10). In this pilot study, we could not quantify the impact of CSH, given the frequency of overlap of public insurance and CSH participation among respondents. Future investigations should explore associations between insurance type, including entities such as CSH, and out-of-pocket costs in a larger cohort of individuals with NS.

To our knowledge, there are no published studies that have described the direct out-of-pocket and indirect costs of NS in either the United States or other countries. However, out-of-pocket costs have been described for other chronic diseases. For instance, the annual direct out-of-pocket costs of asthma, which included medication, office visits, hospitalizations, and emergency room visits were $3761 for adults and $1737 for children (11). A phenylketonuria study illustrated that respondents spent $1961 for low-protein foods and spent more than 300 hours shopping and preparing special diets in a year (5). These costs are comparable to the annual direct costs of adults and caregivers with children living with NS reported in this study.

Participants in this study also reported a significant time burden attributed to NS. These indirect costs were related to dietary needs, medical appointments, and travel time. Furthermore, respondents reported opportunity costs from NS on their personal education with premature withdrawal from school and employment, missed promotions, and early retirement. Adults with ulcerative colitis reported a median of eight medical-related absenteeism days and incurred $5307 in indirect costs per year (12). However, adults with NS reported one missed workday per year, which resulted in a median of $240 lost per year. Furthermore, caregivers with children who have hemophilia missed a median of 3.2 days of work (13). In comparison, caregivers with children with NS missed a median of 5 days. Lastly, children of the family caregivers missed a median of 4 days of school (IQR 0–13 days of school) due to NS, whereas about 13% of students in the United States missed 3–4 days of school in 2015 (14).

This study has some limitations relating to sample size and recall bias. We conducted this as a pilot study to assess both the feasibility of data collection and to generate cost estimates. We enrolled fewer than the goal of 25 adults and 25 family caregivers completing the surveys because the study was prematurely terminated due to the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and potential influence on health care utilization. Although the survey was thorough and covered potential burdens, it was quite long. As a result, participants with the most severe disease may have been more likely to decline participation.

This study is the first to characterize the out-of-pocket direct and indirect costs, which can assist with decision making in regard to NS management strategies and support services needed for implementation of recommended therapies (15). Replication of this work utilizing a larger and more diverse patient sample will be beneficial. Furthermore, future studies enumerating the costs to the health system and payers from health care utilization on a patient and national level are needed to complement this study and generate a comprehensive understanding of the economic impact of NS as a chronic disease.

Disclosures

D.S. Gipson reports consultancy between the University of Michigan and AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech, Goldfinch Bio, Roche, Travere, and Vertex (no individual consultancy agreements); research funding to the University of Michigan from BoehringerIngelheim, Goldfinch Bio, Novartis, Reata, and Travere; being a scientific advisor for or a member of AstraZeneca, Goldfinch Bio, and Vertex; and other interests/relationships with the Nephrotic Syndrome Patient Reported Outcome Consortium (public-private partnership, with Goldfinch Bio, GSK, Pfizer, and Zyversa; NephCure Kidney International). S. Massengill reports consultancy agreements with Guidepoint Network and being a scientific advisor for or a member of the Editorial Board of online Glomerular Disease Journal (Karger Publishers). All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The project was supported in part by the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, CTSA grant NIH/NCATS #UL1TR002240.

Acknowledgments

We thank patients and caregivers and members of the Kidney Research Network Patient Advisory Board.

Footnotes

See related editorial, “The Forgotten Cost of Nephrotic Syndrome to Patients and Caregivers in the United States”, on pages 991–992.

Author Contributions

H.E. Desmond, D.S. Gipson, W.P. Gipson, and S.F. Massengill were responsible for conceptualization; H. Desmond, D.S. Gipson, W.P. Gipson, S.F. Massengill, and C.A. Simon were responsible for the formal analysis, the investigation, the methodology, and project administration; H. Desmond, D.S. Gipson, W.P. Gipson, and C.A. Simon were responsible for data curation; H. Desmond, W.P. Gipson, S.F. Massengill, and C.A. Simon were responsible for supervision; D.S. Gipson was responsible for funding acquisition; D.S. Gipson, W.P. Gipson,S.F. Massengill, E. Salmon, and C.A. Simon reviewed and edited the manuscript; D.S. Gipson, W.P. Gipson, S.F. Massengill, and C.A. Simon were responsible for validation; D.S. Gipson, S.F. Massengill, E. Salmon, and C.A. Simon wrote the original draft of the manuscript; and D.S. Gipson and C.A. Simon were responsible for resources, software, and visualization.

Data Sharing Statement

Partial restrictions to the data and/or materials apply: pilot survey data are not well suited to a repository but are readily available upon request.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material online at https://kidney360.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.34067/KID.0005072021/-/DCSupplemental.

Adult survey summary. Download Supplemental Table 1, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Caregiver survey summary. Download Supplemental Table 2, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Selected free text responses by cost domain. Download Supplemental Table 3, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Adult: Non-ESKD versus ESKD direct out-of-pocket costs (US$). Download Supplemental Table 4, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Adult: Non-ESKD versus ESKD indirect costs (US$). Download Supplemental Table 5, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Caregiver: Non-ESKD versus ESKD direct costs (US$). Download Supplemental Table 6, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Caregiver: Non-ESKD versus ESKD indirect costs (US$). Download Supplemental Table 7, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Non-ESKD adult: direct out-of-pocket costs (US$) by insurance type. Download Supplemental Table 8, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Non-ESKD caregiver: direct out-of-pocket costs (US$)a by insurance type. Download Supplemental Table 9, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

References

- 1.Tapia C, Bashir K: Nephrotic syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL, StatPearls Publishing, 2021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noone DG, Iijima K, Parekh R: Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children. Lancet 392: 61–74, 2018. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30536-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodner C. Diagnosis and management of nephrotic syndrome in adults. Am Fam Physician 93: 479–485, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu ID, Willis NS, Craig JC, Hodson EM: Interventions for idiopathic steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019: 2019. 10.1002/14651858.CD003594.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidney Research Network : Kidney Research Network: About us. Available at: https://www.kidneyresearchnetwork.org/about. Accessed May 31, 2022

- 6.Rose AM, Grosse SD, Garcia SP, Bach J, Kleyn M, Simon NE, Prosser LA: The financial and time burden associated with phenylketonuria treatment in the United States. Mol Genet Metab Rep 21: 100523, 2019. 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2019.100523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, Kelley C, Winkel C: The direct and indirect costs associated with endometriosis: A systematic literature review. Hum Reprod 31: 712–722, 2016. 10.1093/humrep/dev335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Bureau of Labor Statistics : Table B-3: Average hourly and weekly earnings of all employees on private nonfarm payrolls by industry sector, seasonally adjusted. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t19.htm. Accessed June 1, 2021

- 9.Michigan Department of Health & Human Services : General information for families about: “Children’s Special Health Care Services” (CSHCS). Available at: https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/assistance-programs/cshcs/general-information-for-families-about-cshcs. Accessed July 28, 2021

- 10.Pollack HA, Dombkowski KJ, Zimmerman JB, Davis MM, Cowan AE, Wheeler JR, Hillemeier AC, Freed GL: Emergency department use among Michigan children with special health care needs: An introductory study. Health Serv Res 39: 665–692, 2004. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00250.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nurmagambetov T, Kuwahara R, Garbe P: The economic burden of asthma in the United States, 2008–2013. Ann Am Thorac Soc 15: 348–356, 2018. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-259OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilon D, Ding Z, Muser E, Obando C, Voelker J, Manceur AM, Kinkead F, Lafeuille MH, Lefebvre P: Long-term direct and indirect costs of ulcerative colitis in a privately-insured United States population. Curr Med Res Opin 36: 1285–1294, 2020. 10.1080/03007995.2020.1771293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Z-Y, Koerper MA, Johnson KA, Riske B, Baker JR, Ullman M, Curtis RG, Poon JL, Lou M, Nichol MB: Burden of illness: Direct and indirect costs among persons with hemophilia A in the United States. J Med Econ 18: 457–465, 2015. 10.3111/13696998.2015.1016228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García E, Weiss E: Student absenteeism: Who misses school and how missing school matters for performance. Available at: https://www.epi.org/publication/student-absenteeism-who-misses-school-and-how-missing-school-matters-for-performance/. Accessed July 14, 2021

- 15.Mehta M, Nerurkar R: Evaluation and characterization of health economics and outcomes research in SAARC nations. Ther Innov Regul Sci 52: 348–353, 2018. 10.1177/2168479017731583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Adult survey summary. Download Supplemental Table 1, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Caregiver survey summary. Download Supplemental Table 2, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Selected free text responses by cost domain. Download Supplemental Table 3, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Adult: Non-ESKD versus ESKD direct out-of-pocket costs (US$). Download Supplemental Table 4, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Adult: Non-ESKD versus ESKD indirect costs (US$). Download Supplemental Table 5, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Caregiver: Non-ESKD versus ESKD direct costs (US$). Download Supplemental Table 6, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Caregiver: Non-ESKD versus ESKD indirect costs (US$). Download Supplemental Table 7, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Non-ESKD adult: direct out-of-pocket costs (US$) by insurance type. Download Supplemental Table 8, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)

Non-ESKD caregiver: direct out-of-pocket costs (US$)a by insurance type. Download Supplemental Table 9, PDF file, 300 KB (299.5KB, pdf)