Introduction

Due the high incidence of diseases such as hypertension and diabetes, CKD is becoming one of the most highly prevalent noncommunicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (1,2). Therefore, the management of ESKD, a complication of CKD, is a big challenge for those countries where dialysis is not covered by health care systems (3). More than half of patients with advanced CKD do not receive any treatment, especially in LMICs (4). However, even in countries where dialysis health care is covered, for example in India, long-term dialysis represents a financial burden for the government, as does any other kind of subsidy (5).

In Haiti, with a doctor to population ratio of <0.5:1000, the epidemiologic data for CKD remain unavailable for both adults and children. Although a national registry is lacking, several monocentric studies showed the main causes for CKD in adults are arterial hypertension and diabetes. In pediatrics, glomerular diseases, mostly corticoresistant nephrotic syndrome, are the leading etiology. In the 1990s, there were only two adult nephrologists in Haiti; this has increased to six in the last decade, with one pediatric nephrologist. Unfortunately, all of these kidney specialists are working in Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti. Despite the recurrent and complex sociopolitical crises, more patients are being admitted to hospital with kidney disease. It is evident these crises have a negative effect on the kidney health of Haitian people, and undoubtedly on the quality of life of patients with ESKD. Nevertheless, due to the precarity of the Haitian health system, the emphasis should be put on the prevention of, and on providing optimal care for patients with, noncommunicable diseases that cause CKD. Another point is the need for a focus on educating health care providers and on the availability of the drugs and/or biologic tests for patients.

RRT is a lifesaving, high-cost treatment and is unaffordable for most patients in LMIC. In such countries, people usually die within the first few months of dialysis due to multiple causes, such as inadequate resources, discontinued, or irregular access (6,7). According to International Society of Nephrology, peritoneal dialysis (PD) should be a priority in LMIC (8). PD is cheaper and more sustainable than hemodialysis; the use of PD continues to rise: the rate of PD increased by 25 patients per million between 1996 and 2008 (9,10). In Latin America, hemodialysis is the most common form of RRT. However, PD and renal transplant are becoming more widely available, with 20% of patients with ESKD using PD and 20% having a functioning renal allograft. For example, as of 2012, PD was a major form of RRT in Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala (11).

Audit of RRT in Haiti

Unfortunately, PD and kidney transplantation are still not available in Haiti. As stated earlier, the number of patients with ESKD is increasing and there is a huge gap between this the number of patients with access to RRT (8,12). LMIC such as Haiti cannot meet the increased need for dialysis.

Description of Dialysis in Haiti

There is increasing interest in noncommunicable diseases in Haiti. Therefore, health professionals and the government must be aware of the consequences and challenges of CKD so they can improve patients’ quality of life.

Disparities in Access to Dialysis

Patients with ESKD are facing great inequities in access to high-quality management of kidney failure. In addition, when patients or their guardians initiate chronic dialysis, it might only be for a limited period due to the out-of-pocket costs.

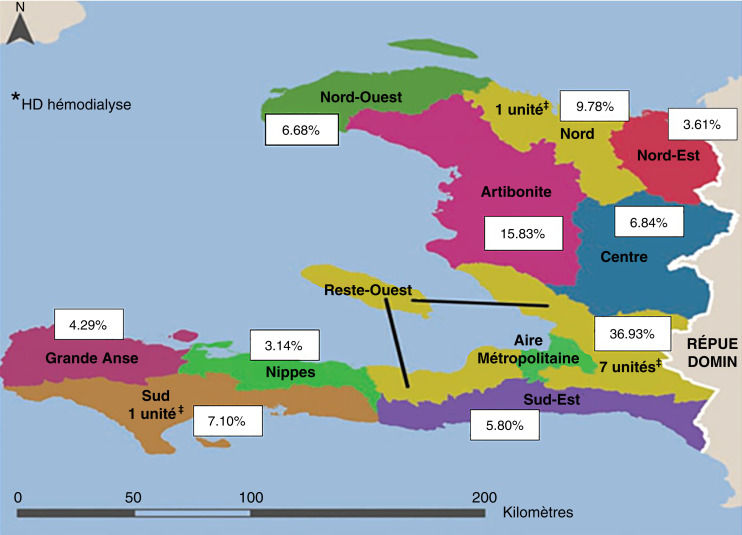

The same global disparities are also seen, with CKD mortality reflecting the disparities in access to care even in the earliest stages. Lack of access to dialysis is an important cause of increased CKD mortality in Haiti as in other LMIC; the disparities are numerous and diverse. Figure 1 demonstrates the geography of dialysis units in the country and the percentage of population per department.

Figure 1.

Distribution of dialysis units in 2021. White box: percentage of total population; metropolitan area = Port-au-Prince.

Living Area

This parameter is important given that people living outside of the metropolitan region of Port-au-Prince do not have access to kidney care. When it comes to RRT, they must travel to Port-au-Prince from all over the country (often a long way from family, friends, or their church). Although the country’s hemodialysis units were not really affected by the earthquake in August 2021, access to the kidney clinic or dialysis unit is compromised by security issues and sociopolitical crisis in the country since 2019 (several “peyi lok” or country lockdowns). In addition to well-known complications of ESKD, this is a non-negligible mortality risk factor for our patients.

Economic Aspect

In 2012, 59% of the population of Haiti lived below the poverty line of US$2.41, with 24% below the extreme poverty line of US$1.23 per day (13). Few patients have access to health insurance or disability financial support (12). The cost of hemodialysis treatment varies between public and private facilities, and between private facilities themselves. As a result, the number of dialysis sessions per week will also depend on the patients’ or their family’s finances because all expenses are out of pocket. At the dialysis unit of the State University Hospital, patients can only have two sessions per week due to the limited number of machines available and the number of patients in need of dialysis. Although the out-of-pocket cost at this unit is ten times less than in the private sector (US$20 vs US$200), it is an expensive and unrealistic option for most patients. We report some data on the dialysis unit in a metropolitan area in Table 1. Private insurance companies offer one dialysis session to their members per week, so a total of 52 sessions per year, which is inadequate for patients’ wellbeing. For some patients, the cost could be very high, depending on vascular access. An arteriovenous fistula is an option for people who can afford it, although the surgery is only carried out privately.

Table 1.

Dialysis data of the dialysis unit in a metropolitan area

| Type of Facility | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | Non-profit unit | Profit unit | |||||

| State University Hospital (Hôpital de l’Université d’Etat d’Haïti) | Other Hospital West department | Private 1 | Private 2 | Private 3 | Private 4 | Private 5 | |

| Mean number of patients per facility | 15 (9M) | Unknown | 24 (18M) | 12 (11M) | 8 | 10 | Unknowna |

| Insurance coverage | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown |

| Hospital-based units | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Rb in US$ | No | No | 1 session per month for private insurance | 1 session per month for private insurance | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Patient /RN ratio | Not standard | ||||||

| Average length of dialysis session, h | 3 | 3 | 3–4 | 4 | 3–4 | 3–4 | 3–4 |

| % patients with AVF | 40–50 | Unknown | 80–90 | 90 | 80 | Unknown | Unknown |

M, male; Rb, reimbursement; RN, registered nurse; AVF, arteriovenous fistula.

Opened 6 months ago.

Human Resources

Haiti has six nephrologists and one pediatric nephrologist. There is no local nephrology fellowship or specific training program for nurses working in dialysis units. One center has one psychologist for follow-up. Thanks to the International Society of Nephrology, in January 2018 a PD training class was held for >40 participants (doctors and nurses), but nothing since. There is also a lack of multidisciplinary collaboration due to an absence of psychosocial workers, dietitians for example. Given the increase in the number of patients with CKD seen in our center over the last few years, all stakeholders in collaboration with the schools of medicine must build a formal local program of nephrology and skills of the primary care providers.

Lack of Drugs

In the hemodialysis unit of Hôpital de l’Université d’Etat d’Haïti, the patients receive erythropoiesis-stimulating agents free of charge when they are available, whereas this is a paid-for service in other centers. Vitamin D analogs and phosphate binders such as sevelamer are not available, nor is a growth hormone injection (for children).

Lack of Supplies

The small hemodialysis unit of Hôpital de l’Université d’Etat d’Haïti, the only public dialysis facility in the country, faces regular supply shortages. Around half of patients receive dialysis through central venous catheters, which are prone to infection or dysfunction.

Laboratory Exams

Biologic examinations are not carried out regularly due to patients’ socioeconomic problems. There is sometimes incoherence between the results and patients’ clinical evaluations.

Anemia Management

Due to a lack of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, the red blood cell transfusion rate is high and there is a lack of blood at the blood bank.

Pediatric Dialysis Ward

Children and adults dialyze in the same room and there are no pediatric-trained nursing staff. There are no appropriately sized hemodialysis catheters for children. PD modality is not available in the country. Some infants are on PD with locally made peritoneal fluid. We used a thoracic drain because of a lack of PD catheters.

Conclusion

Managing dialysis in Haitian patients (children or adults) is a challenge. The unaffordable cost of treatment (direct and indirect) and the lack of access to health insurance contribute to the impoverishment of the families because payments are out of pocket. The problem is multifactorial and complex. However, with the collaboration of national and international partners, we can alleviate some of the issues and improve the quality of life of our patients. Education, governance, access to care, financing, and human resources are all essential components to meet the goals of improved dialysis for all. We need national ESKD and CKD registries.

Disclosures

The author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the author(s) and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or Kidney360. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the author(s).

Author Contributions

J. Exantus reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators : Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 385: 117–171, 2015. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, Saran R, Wang AY, Yang CW: Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 382: 260–272, 2013. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jha V, Arici M, Collins AJ, Garcia-Garcia G: Understanding kidney care needs and implementation strategies in low-and middle-income countries: Conclusions from a “Kidney Disease: Improving Global outcomes” (KDIGO) Controversies Conferences. Kid Int 90: 1164–1174, 2016. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V, Neal B, Patrice HM, Okpechi I, Zhao MH, Lv J, Garg AX, Knight J, Rodgers A, Gallagher M, Kotwal S, Cass A, Perkovic V: Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: A systematic review. Lancet 385: 1975–1982, 2015. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradshaw C, Gracious N, Narayanan R, Narayanan S, Safeer M, Nair GM, Murlidharan P, Sundaresan A, Retnaraj Santhi S, Prabhakaran D, Kurella Tamura M, Jha V, Chertow GM, Jeemon P, Anand S: Paying for hemodialysis in Kerala, India. Kidney Int Rep 4: 390–398, 2018. 10.1016/j.ekir.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luyckx VA, Brenner BM: Birth weight, malnutrition and kidney-associated outcomes—a global concern. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 135–149, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham G. The challenges of renal replacement therapy in Asia. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 4: 643–655, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The ISN framework for developing dialysis programs in low-resource settings https://www.theisn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ISN-Framework-Dialysis-Report-HIRES.pdf

- 9.Carter M, Kilonzo K, Odiit A, Kalyesubula R, Kotanko P, Levin NW, Callegari J: Acute peritoneal dialysis treatment programs for countries of the East African community. Blood Purif 33: 149–152, 2012. 10.1159/000334139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain AK, Blake P, Cordy P, Garg AX: Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 533–544, 2012. 10.1681/ASN.2011060607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Bedat M, Rosa-Diez G, Pecoits-Filho R, Ferreiro A, García-García G, Cusumano A, Fernandez-Cean J, Noboa O, Douthat W: Burden of disease: Prevalence and incidence of ESRD in Latin America. Clin Nephrol 83[Suppl 1]: 3–6, 2015. 10.5414/CNP83S003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Exantus J, Desrosiers F, Ternier A, Métayer A, Abel G, Buteau JH: The need for dialysis in Haiti: Dream or reality? Blood Purif 39: 145–150, 2015. 10.1159/000368979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institut Haitien de Statistique et Informatique . Enquête sur les Conditions de Vie des Ménages après Séisme (ECVMAS), 2012 [Google Scholar]