Abstract

Recurrent high-risk neuroblastoma is a childhood cancer that often fails to respond to therapy. Fenretinide (4-HPR) is a cyototoxic retinoid with cliical activity in recurrent neuroblastoma and venetoclax (ABT-199) is a selective inhibitor of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2. We evaluated activity of 4-HPR + ABT-199 in preclinical models of neuroblastoma. Patient-derived cell lines and xenografts from progresssive neuroblastoma were tested. Cytotoxicity was evaluated by DIMSCAN, apoptosis by flow cytometry, gene expression by RNA sequencing, RT-PCR, and immunoblotting. 4-HPR + ABT-199 was highly synergistic against high BCL-2 expressing neuroblastoma cell lines and significantly improved event-free survival of mice carrying high BCL-2 expressing patient-derived xenografts (PDXs). In 10 matched-pair cell lines (established at diagnosis (DX) and relapse (PD) from the same patients), BCL-2 expression in the DX and PD lines were comparable, suggesting that BCL-2 expression at diagnosis may provide a biomarker for neuroblastomas likely to respond to 4-HPR + ABT-199. In a pair of DX (COG-N-603x) and PD (COG-N-623x) PDXs established from the same patient, COG-N-623x was less responsive to cyclophosphamide + topotecan than COG-N-603x, but both DX and PD PDXs were responsive to 4-HPR + ABT-199. Synergy of 4-HPR + ABT-199 was mediated by induction of NOXA via 4-HPR stimulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that induced expression of ATF4 and ATF3, transcription factors for NOXA. Thus, fenretinide + ventoclax is a synergistic combination that warrants clinical testing in high BCL-2 expressing neuroblastoma.

Keywords: 4-HPR, ABT-199, Apoptosis, NOXA, Neuroblastoma

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is an extra-cranial malignant tumor, arising along the sympathetic chain most commonly in the adrenal gland and is the most common extracranial solid tumor in childhood. Age, MYCN amplification, stage, DNA ploidy, and histology are used to stratify patients with neuroblastoma into low, intermediate, and high-risk. Patients with high-risk tumors are those with genomic amplification of the MYCN oncogene, patient age > 18 months at diagnosis, higher stage, diploid, and unfavorable histology (1). Despite intensive treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, myeloablative chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, followed by maintenance therapy with 13-cis-retinoic acid and anti-GD2 antibody + cytokines, the five-year overall survival rate for patients with high-risk neuroblastoma is still ~ 50% (1,2). Therefore, investigating novel drug combinations is crucial for improving the therapy of high-risk neuroblastoma.

B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) family of proteins consists of 25 pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members (3). Pro-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins play vital roles in inducing apoptosis in response to external stress signals while anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins promote cancer cell survival by antagonizing apoptosis and thus provide therapeutic targets (4). BCL-2 overexpression is frequent in various cancers, including neuroblastoma, and BCL-2 modulation can increase sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents (5–7). ABT-737 (a preclinical version of navitoclax = ABT-263) is active against preclinical models of hematologic malignancies (8–10), neuroblastoma (5,11), and small cell lung cancer (12). Clinical development of navitoclax (an orally bioavailable version of ABT-737) was curtailed due to dose-dependent thrombocytopenia resulting from the inhibition of BCL-XL by ABT-263 (13). This led to the development of venetoclax (ABT-199), a selective BCL-2 protein inhibitor that does not inhibit BCL-XL, thus avoiding thrombocytopenia (13). ABT-199, which is well-tolerated by patients achieving 2 μM plasma concentrations, was granted an FDA registered indication for treating chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with a 17p deletion (14,15) and is being investigated in clinical trials of multiple hematologic malignancies (16) as well as pre-clinically for solid tumors (17) including neuroblastoma (6,18,19).

Fenretinide (4-HPR), a synthetic retinoid, can safely achieve 10 to 40 micromolar plasma levels in children and has shown multiple complete responses among heavily pre-treated neuroblastoma patients (20). 4-HPR can activate apoptosis independent of retinoid receptors and p53 (21), an essential consideration as loss of p53 function has been shown to be a mechanism of multi-drug resistance in neuroblastoma (22). 4-HPR increases accumulation of toxic dihydroceramides in neuroblastoma by activating de novo dihydroceramide synthetic enzymes while simultaneously inhibiting dihydroceramide desaturase (23). The increased dihydroceramides in response to 4-HPR occur selectively in malignant cells and minimally in non-malignant cells (24). Another primary mechanism of 4-HPR inducing cell death is via increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (21). We have previously demonstrated that ABT-737 significantly increased the activity of fenretinide in in vitro and in vivo models of neuroblastoma (11) and ALL (9).

BCL-2 is essential for survival of some cancer cells, including a subset of BCL-2-dependent neuroblastomas, and high BCL-2 expression is a potential biomarker of sensitivity to BCL-2 inhibitors (5,25,26). However, it is often not feasible to obtain the tumor biopsies from recurrent neuroblastoma patients to determine the BCL-2 expression level due to ethical and clinical reasons. We determined if ABT-199 can synergize with 4-HPR against neuroblastoma. We also assessed BCL-2 expression as a potential biomarker of sensitivity to ABT-199 + 4-HPR and we determined the mechanism of synergistic anti-neuroblastoma activity between 4-HPR and ABT-199.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

Fenretinide (4-HPR) for in vitro experiments and fenretinide oral powder formulation in Lym-X-Sorb were from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). Venetoclax (ABT-199) was from AbbVie. Ketoconazole (Keto) was from TEVA Pharmaceuticals. Ascorbic acid was from Sigma Aldrich. H2DCFDA was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Cyclophosphamide (cyclo) was obtained from Baxter Healthcare. Topotecan (topo) was from SAGENT Pharmaceuticals. ABT-199 was dissolved in 60% phosal 50 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 30% peg 400 (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10% ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) for dosing of mice. All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) was from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell Culture.

All cell lines used in this study are described in Supplementary Table 1 and were obtained from the COG/ALSF Childhood Cancer Repository (www.CCcells.org). Neuroblastoma cell lines used in the study were cultured in complete medium of Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco – Life Technologies), 4 mmol/L L-glutamine (Corning Cellgro), insulin and transferrin (20 mg/mL each), and selenous acid (20 ng/mL; ITS Culture Supplement; BD Biosciences). Cell line and patient-derived xenograft identities were verified via short-tandem repeat (STR) profiling by GenePrint® 10 System from Promega validated against a searchable online database at www.CCcells.org, before starting and at the conclusion of the experiments, and were confirmed to be free of mycoplasma with MycoAlert Mycoplasma detection kit from Lonza. Cells were cultured and treated in a 37 deg C humidified incubator gassed with 5% CO2 and 90% N2, to achieve bone marrow level hypoxia of 5% O2 (27). Cell lines with the “h” suffix were established in and only cultured in 5% O2.

Cytotoxicity assay.

We plated neuroblastoma cells in 96 well plates for 24 hrs before treating with either 4-HPR (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM), ABT-199 (0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, and 5 μM), or the combination of 4-HPR + ABT-199 at 1:2 drug concentration ratio. There were six replicates per drug concentration, and the control was treated with drug vehicle. After 96 hrs of drug incubation, cell viability was measured using the DIMSCAN assay as previously described (28–30).

Protein expression analysis.

Cells were collected and washed twice with PBS before lysing with lysis buffer, RIPA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) + protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich) + phosphatase inhibitors (NAF and NA3VO4). The protein concentration was quantified by BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific), then diluted with NuPAGE™ LDS Sample Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Dithiothreitol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Protein was transferred from the gel onto the Amersham Protran 0.45 NC nitrocellulose Western blotting membrane using the GE Healthcare Amersham™ TE 70 Semi-Dry Transfer Unit. The nitrocellulose membrane was blocked by 1% BSA solution for 1 hr, then incubated with primary antibody overnight. The next day, the membrane was washed three times (10 mins each) in 1X TBST solution before incubating with secondary antibody for 1 hr, then the membrane was washed three times (10 mins each) with TBST before developing for chemiluminescent signal using Amersham ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare), and HyBlot CL® Autoradiography Film (Denville Scientific) or Amersham Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare).

Primary antibodies, anti-BIM (2933), anti-BAD (9292), anti-NOXA (14766), anti-PUMA (12450), anti-BAK (6947), anti-BAX (2772), anti-BIK (4592), anti-BETA ACTIN (8457), anti-ATF4 (11815), anti-BCL-2(2872), anti-BCL-W (2724), anti-BCL-XL (2764), were from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-ATF-3 (SC81189) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and anti-MCL-1 (559027) was from BD Biosciences. Anti-FLAG® (F3165) antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit-7074, and anti-mouse-7076) were from Cell Signaling Technology. For co-immunoprecipitation, NOXA (Myc-DDK tagged) was immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG® beads (Sigma-Aldrich). 3X FLAG® Peptide (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to elute NOXA (Myc-DDK-tagged protein) from the anti-FLAG® beads.

Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR).

RNA was as extracted by RNeasy Mini Kit (QUIAGEN) as per kit instructions. The primers used in the study are: ATF-4 (Hs00231069_m1, ThermoFisher, ThermoFisher), ATF-3 (Hs00231069_m1, ThermoFisher), NOXA (Hs00560402_m1, ThermoFisher), and GAPDH (Hs.PT.39a.22214836, Integrated DNA Technologies). RT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicate in a 96 well plate with TagMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents (Applied Biosystems) using QuantStudio 12K Flex. The cycling conditions were 30 minutes at 48° C, 10 minutes at 95°C, then 45 cycles of 15 seconds at 95° C, and 1 minute at 60° C.

RNA Sequencing.

RNA Seq libraries were prepared from polyA-selected RNA and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 as described in (31). The FASTQ formatted sequence reads were aligned to GRCh37.69 using the STAR RNA Seq aligner (v2.3.1) (32) and transcripts were assembled and quantified using Cufflinks v2.1.1 (33) and reported as fragments per kilo base of gene length per million reads (FPKM).

Immunohistochemistry.

Tissue sections (4-μm) were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated by ethanol. For antigen retrieval, sections were steamed at 95⁰ C with citrate buffer (pH = 6.0) for 30 minutes. After cooling for 5 minutes, endogenous peroxidase was blocked with dual endogenous enzyme blocking agent (Dako, S2003) for 10 minutes. Sections were incubated with anti-BCL-2 (M0887, DAKO, 1:50) primary antibody for 1 hour in a humidified chamber at room temperature, followed by incubation with secondary antibody (8125S, Cell Signaling) for 30 minutes and detected with signal stain DAB substrate kit (Cell Signaling) after 10 minutes. All wash steps were performed with 1X tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 5 minutes. Sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin, rehydrated, and mounted. Mounted slides were imaged using Olympus BX551.

Apoptosis (DNA fragmentation) Assay.

Cells were plated in triplicate before treating with 4-HPR (10 μM), ABT-199 (2 μM), or 4-HPR (10 μM) + ABT-199 (2 μM). The amount of DNA fragmentation is quantified by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay (APO-DIRECT™ KIT from BD Biosciences). We followed the company established protocol, except the incubation time with DNA-Labeling Solution which was adjusted to 3 hrs. to maximize the staining of neuroblastoma cell lines. Then, the cells were analyzed by BD LSR II flow cytometer (San Jose, CA) with BD FACSDiva™ software (version 6.1.3) by gating for singlets and detecting % of FITC-positive population with emission at 520 nm.

Xenograft Studies.

Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) used in this study are described in Supplementary Table and were obtained from the COG/ALSF Childhood Cancer Repository (www.CCcells.org). Six to 8 weeks old female nu/nu mice (Envigo) were subcutaneously injected with 10–20 million cells from a progressively growing PDX. Then, tumor-bearing mice were randomized into control and treatment groups at 100 to 300 mm3 tumor volume, which was measured by ½ length X width X height as previously described (34). Mice were sacrificed once the tumor volume exceeded 1500 mm3 or if moribund from toxicity or illness.

4-HPR in Lym-X-Sorb™, a matrix of lipids designed to increase 4-HPR solubility and bioavailability (35) oral powder formulation, dissolved in water, was given to mice by gavage at 180 mg/kg/day divided in two equal doses. Ketoconazole (a CYP3A4 inhibitor) was administered to mice by gavage at 38 mg/kg/day to enhance systemic exposure to 4-HPR (36). ABT-199, dissolved in 60% phosal 50 propylene glycol, 30% polyethylene glycol 400, and 10% ethanol, was given at 75 mg/kg/day by gavage. 4-HPR, ABT-199, vehicle, or 4-HPR + ABT-199 was administered for up to 100 days, after which all remaining mice were sacrificed. Cyclophosphamide was given by intraperitoneal (IP) injection at 30 mg/kg and topotecan by IP injection at 0.6 mg/kg. Cyclophosphamide and topotecan (CYCLO + TOPO) were given for five days (day 1 to 5) every 21 days cycle (total 3 cycles). Mouse survival was analyzed by log-rank test of event-free survival in which an event was tumor volume exceeding 1500 mm3, mouse being sacrificed for humane reasons (illness or toxicity), or death from any cause. The protocol was approved by the TTUHSC Laboratory Animal Resources Center and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Stable knockdown or overexpression of genes.

Lentiviruses containing either shRNA plasmid (pLKO.1) or EGFP-KD (pLKO.1-non-targeting plasmid) were packaged using Lenti-vpak packaging kit from Origene, following kit instructions with minor modifications. Cells were plated in 6-well plates; then the virus-containing medium was added and incubated for 72 hrs. The transduced cells were selected with 1.5 μg/ml of puromycin dihydrochloride (Sigma) until stable clones were established. PMAIP1 (TRCN0000151311) TRC lentiviral shRNA plasmid was from Dharmacon. PMAIP1 (TRC202071) Human cDNA ORF Clone plasmid was ordered from Origene then sub-cloned into a doxycycline-inducible plasmid, pCW57-MCS1–2A-MCS2. pCW57-MCS1–2A-MCS2 was a gift from Adam Karpf (Addgene plasmid # 71782).

Transient knockdown of ATF3 and ATF4 by siRNA.

Cells were plated in complete growth medium 24 hrs before the transfection. Growth medium was replaced with Opti-MEM™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before transfection. Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX was used as the transfection agent along with 150 nM of ON-TARGETplus non-targeting pool (Dharmacon), 150 nM of SMARTpool: ON-TARGETplus ATF3 siRNA (Dharmacon) or 150 nM of SMARTpool: ON-TARGETplus ATF4 siRNA (Dharmacon). Cells for incubated with the siRNA for 12 hrs before the transfection medium was replaced by complete growth medium and treated with 5 uM of 4-HPR for 6 hrs prior to use in experiments.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Detection Assay.

ROS generation was detected using 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) and flow cytometry (9), with cells washed after staining with 1X PBS (to eliminate interference from phenol red dye in the medium) and reconstituted in PBS before analysis; 100 μM of H2O2 was used as a positive control. Vitamin C at 150 μM was used to antagonize the ROS generated by 4-HPR treatment.

Statistical analysis.

Anti-apoptotic protein expression and combination index value (CIN) was compared using unpaired two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction. The difference in dose-response curves of ABT-199 versus ABT-199 plus doxycycline treatment for PCW empty vector and PMAIP1-PCW stably infected cell lines was compared by the ratio paired two-tailed t-test. The difference in % of apoptotic cells between 4-HPR, ABT-199, and 4-HPR + ABT-199 was compared by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. The differences in fold change in DCFDA fluorescence between the control, 4-HPR, 4-HPR + vitamin C were compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. The differences in mRNA expression of NOXA, ATF3, and ATF4 were compared by paired two-tailed t-test. The difference in survival curves was compared by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. The difference in the dose response curves of 4-HPR, ABT-199, and 4-HPR + ABT-199 with or without the presence of vitamin C was compared by the ratio paired two-tailed t-test. The differences in BCL-2 protein expression, ABT-199 fraction affected, and the 4-HPR+ABT-199 CIN value for the high BCL-2 and low BCL-2 groups as well as MYCN-amplified and MYCN non-amplified groups were compared by non-paired two-tailed t-test. All statistical analysis was computed using GraphPad Prism 7.01. The combination index value (CIN) (37) and the concentration cytotoxic or inhibitory for 50% of cells (IC50) were computed using CompuSyn software (ComboSyn, Inc). All statistical tests were considered significant when P ≤ 0.05.

Results

BCL-2 is a biomarker of ABT-199 sensitivity and 4-HPR + ABT-199 synergy in neuroblastoma cell lines.

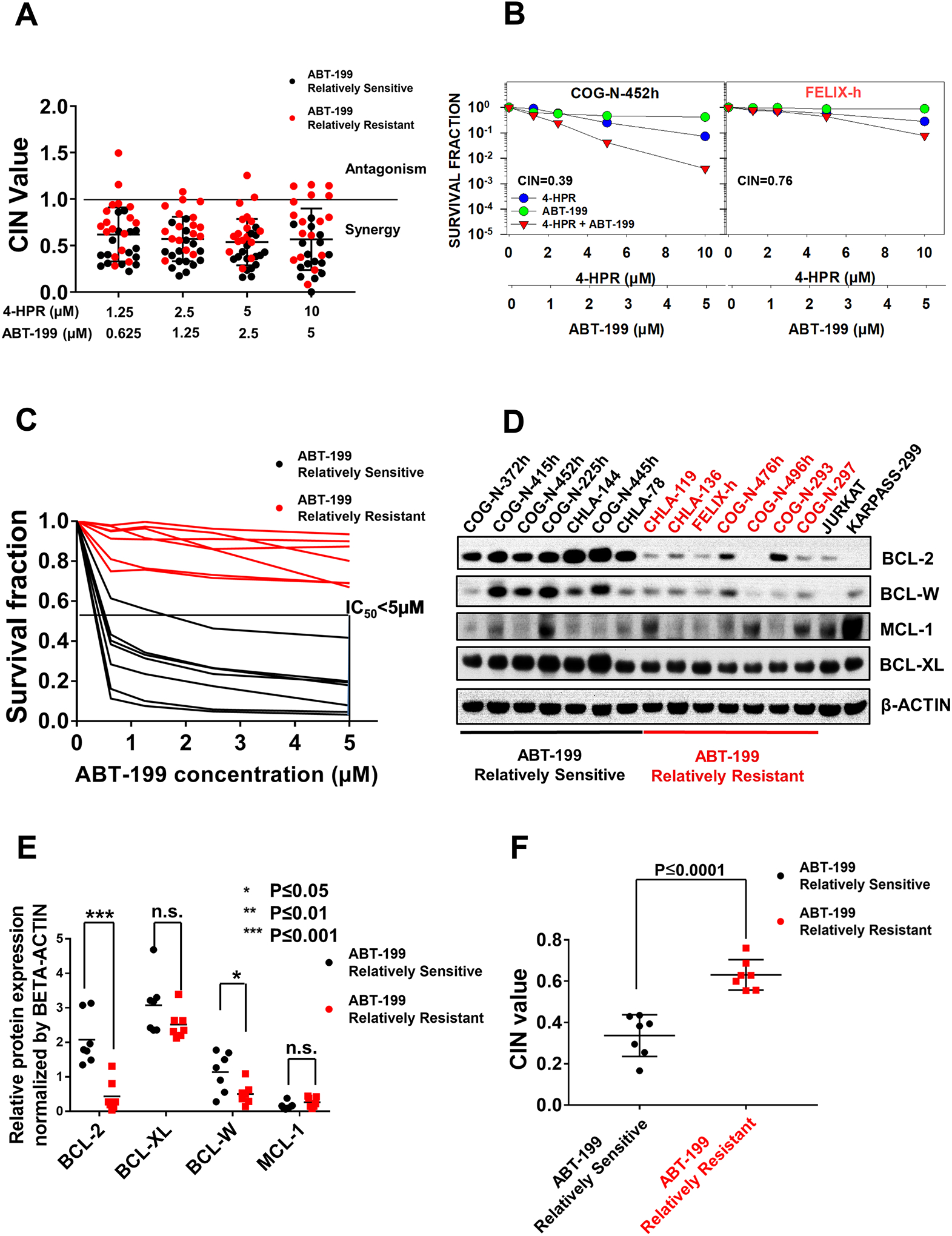

4-HPR and ABT-199 showed synergistic activity in multiple neuroblastoma cell lines (Fig. 1A, 1B, S1, S2), within the clinically achievable concentrations for both agents. We classified cell lines with ABT-199 IC50 > 5 μM (2.5 times clinically achievable concentration) as relatively resistant to ABT-199. Cell lines relatively sensitive to single-agent ABT-199 (defined as ABT-199 IC50 < 5 μM) showed greater synergy between 4-HPR + ABT-199 compared with cell lines relatively resistant to ABT-199 (Fig. 1A). Since BCL-2 expression has been shown to be a biomarker for the sensitivity to BCL-2 family inhibitors (ABT-737 and ABT-263) (25), the association between the expression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family of proteins and sensitivity to ABT-199 was examined. In seven each of the neuroblastoma cell lines most sensitive and resistant to ABT-199 (Fig. 1C) we assessed expression of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family of proteins (Fig. 1D). BCL-2 and BCL-W protein levels in the ABT-199-sensitive cell lines were significantly higher than in ABT-199-resistant cell lines; BCL-2 protein showed a greater difference than BCL-W (Fig. 1D, 1E). The seven ABT-199-sensitive cell lines showed much stronger synergy (lower CIN value) between 4-HPR + ABT-199 than the seven ABT-199-resistant cell lines (P≤0.0001, Fig. 1F).

Figure 1.

BCL-2 protein expression as a marker of ABT-199 sensitivity and 4-HPR + ABT-199 synergy in neuroblastoma cell lines. A, Combination index values (CIN) of all tested neuroblastoma cell lines for the combination cytotoxicity of ABT-199 and 4-HPR showing data for 15 ABT-199 relatively sensitive cell lines (ABT-199 IC50 < 5 μM), black symbols and 17 ABT-199 relatively resistant cell lines (ABT-199 IC50 > 5 μM), red symbols. CIN < 1 (synergy), CIN = 1 (additive effect), CIN > 1 (antagonism) (37). Fixed-ratio dose-response curves used to generate data for Fig. 1A are shown in Figs S1 and S2. B, Example of DIMSCAN assay dose response curves for ABT-199 relatively sensitive (COG-N-452h) and ABT-199 relatively resistant (Felix-h) cell lines. Cells were treated with varying (fixed-ratio) concentrations of 4-HPR, ABT-199, and 4-HPR + ABT-199 (6 replicates per drug concentration) for 96 hrs then analyzed by the DIMSCAN assay. C, Dose-response curves of seven ABT-199 relatively sensitive and seven ABT-199 relatively resistant cell lines selected for determining the difference in basal expression of anti-apoptotic proteins. D, Expression of anti-apoptotic proteins in seven ABT-199 relatively sensitive cell lines and seven ABT-199 relatively resistant cell lines. E, Dot plots quantitating immunoblotting data shown in panel C. The BCL-2 and BCL-W protein levels were significantly higher in the ABT-199 relatively sensitive group versus the ABT-199 relatively resistant group. n.s.: not significant. F, CIN values for the 7 selected ABT-199 relatively sensitive cell lines compared to 7 selected ABT-199 relatively resistant cell lines. 4-HPR + ABT-199 combination index (CIN) values of the ABT-199 relatively sensitive lines was significantly lower than the CIN values of the ABT-199 relatively resistant lines.

BCL-2 is a biomarker for 4-HPR + ABT-199 activity in neuroblastoma patient-derived xenografts (PDXs).

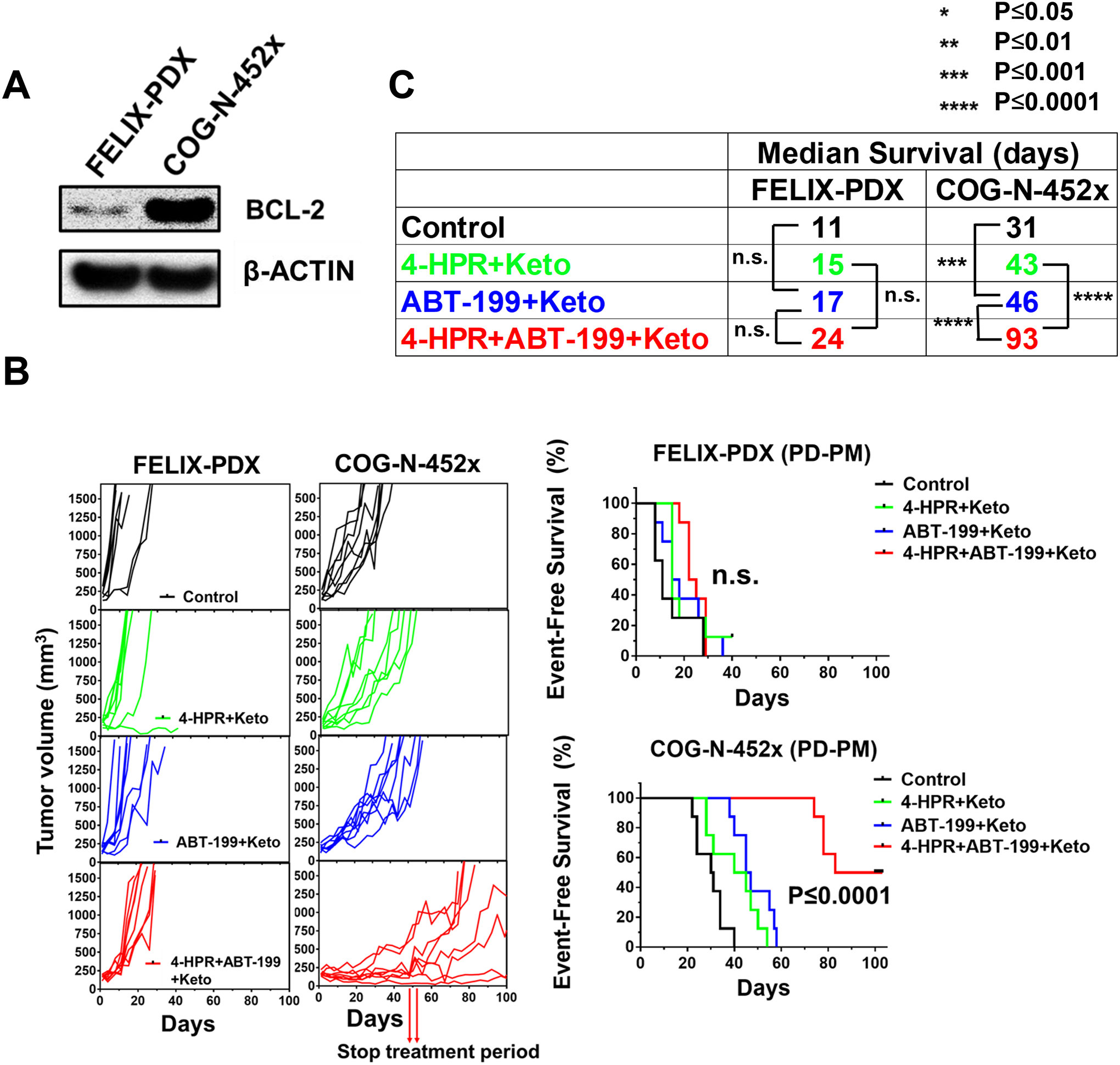

We tested activity of 4-HPR + ABT-199 using two PDXs, both established at post-mortem from progressive disease after therapy: Felix-PDX (low BCL-2 expression) and COG-N-452x (high BCL-2 expression) (Fig. 2A, S3A). In COG-N-452x, ABT-199 + keto significantly extended event-free survival (EFS) relative to vehicle control (P≤0.001) and EFS of mice treated with 4-HPR + ABT-199 + keto was greater than 4-HPR + keto (93 vs 43 days, P≤0.0001) or ABT-199 + keto (93 vs 46 days, P≤0.001) (Fig. 2B, 2C). Felix-PDX (low BCL-2 expression) did not show significant improvement in EFS for ABT-199 + keto versus control or for 4-HPR + ABT-199 +keto relative to the 4-HPR + keto or ABT-199 + keto (Fig. 2B, 2C).

Figure 2.

4-HPR + ABT-199 + keto significantly enhanced event-free survival (EFS) of mice carrying a high BCL-2 expressing PDX. A, BCL-2 protein expression in two PDXs established at time of death from progressive neuroblastoma, FELIX-PDX (low BCL-2 expression) and COG-N-452x (high BCL-2 expression). B, Tumor growth curves and event-free survival of the control, 4-HPR + keto, ABT-199 + keto, and 4-HPR + ABT-199 + keto groups for FELIX-PDX and COG-N-452x. 4-HPR + ABT-199 + keto significantly improved EFS versus the 4-HPR + keto and ABT-199 + keto groups for COG-N-452x PDX but not FELIX-PDX. C, Median EFS of the control, 4-HPR + keto, ABT-199 + keto, and 4-HPR + ABT-199 + keto groups for COG-N-452x and FELIX-PDX.

BCL-2 expression is consistent from diagnosis to progressive disease in the same patient.

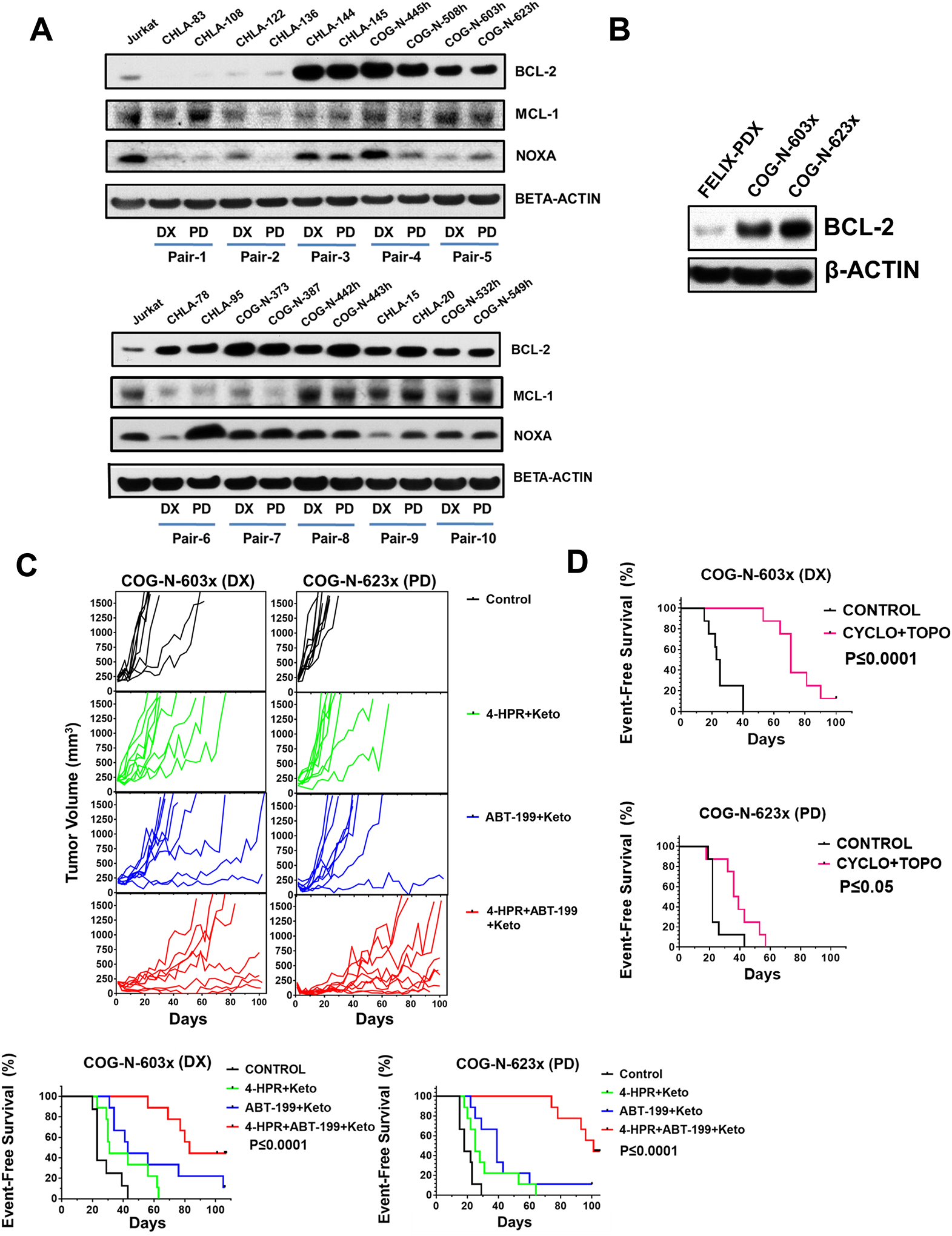

Because obtaining tumor biopsies at time of progressive disease to analyze BCL-2 protein expression as a biomarker can be challenging, we compared BCL-2 protein expression in a panel of neuroblastoma matched pairs (cell lines established at diagnosis and progressive disease from the same patient) from 10 patients. BCL-2 protein expression was consistent between diagnosis and relapse cell lines established from the same patient (Fig. 3A). We also compared BCL-2 protein expression in a matched pair of PDXs established at diagnosis and progressive disease from the same patient, COG-N-603x (diagnosis) and COG-N-623x (progressive disease). The matching cell lines for these PDXs are COG-N-603h and COG-N-623h. We observed that COG-N-603x and COG-N-623x both expressed high BCL-2 protein levels (Fig. 3B, S3B), which is consistent with the expression of BCL-2 in the matching cell lines (Fig. 3A). 4-HPR + ABT-199 + keto was more active against both DX and PD PDXs relative to 4-HPR + keto (P≤0.0001) or to ABT-199 + keto (P≤0.001) (Fig. 3C, S4A). These data are consistent with our observations in cell lines showing that BCL-2 is a biomarker for 4-HPR + ABT-199 activity, and that BCL-2 protein expression is consistent between diagnosis and progressive disease. In the matched pair PDXs we assessed the activity of cyclophosphamide plus topotecan (CYCLO + TOPO, one of the treatment regimens for neuroblastoma) (38). COG-N-623x (PD, median mouse survival = 38 days) was significantly more resistant (P≤0.05) to CYCLO + TOPO treatment relative to COG-N-603x (DX, median mouse survival = 71 days) (Fig. 3D, S4B), demonstrating that 4-HPR + ABT-199 is non-cross-resistant with standard cytotoxic chemotherapy for neuroblastoma.

Figure 3.

BCL-2 protein expression at diagnosis and relapse are consistent and may provide a biomarker for neuroblastoma tumors likely to respond to the combination of 4-HPR + ABT-199. A, BCL-2, NOXA, and MCL-1 protein expression for matched pair cell lines (established at diagnosis and relapse from 10 patients). High BCL-2 expressing cell lines established at diagnosis (DX) and later at relapse (PD) from the same patient show comparable BCL-2 protein expression. B, High BCL-2 protein expression was observed for both PDXs of the matched pair PDX models, COG-N-623x (DX) and COG-N-603x (PD). C, Tumor growth curves and EFS of the control, 4-HPR + keto, ABT-199 + keto, and 4-HPR + ABT-199 + keto groups for COG-N-603x and COG-N-623x. Both models showed significant improvement in survival for 4-HPR + ABT-199 + keto versus the 4-HPR + keto and ABT-199 + keto groups. D, EFS of the control and cyclophosphamide + topotecan (CYCLO + TOPO) groups for COG-N-603x (DX) and COG-N-623x (PD) showing the increased resistance of COG-N-623x to CYCLO + TOPO compared to COG-N-603x.

4-HPR enhanced ABT-199 apoptosis by inducing NOXA expression.

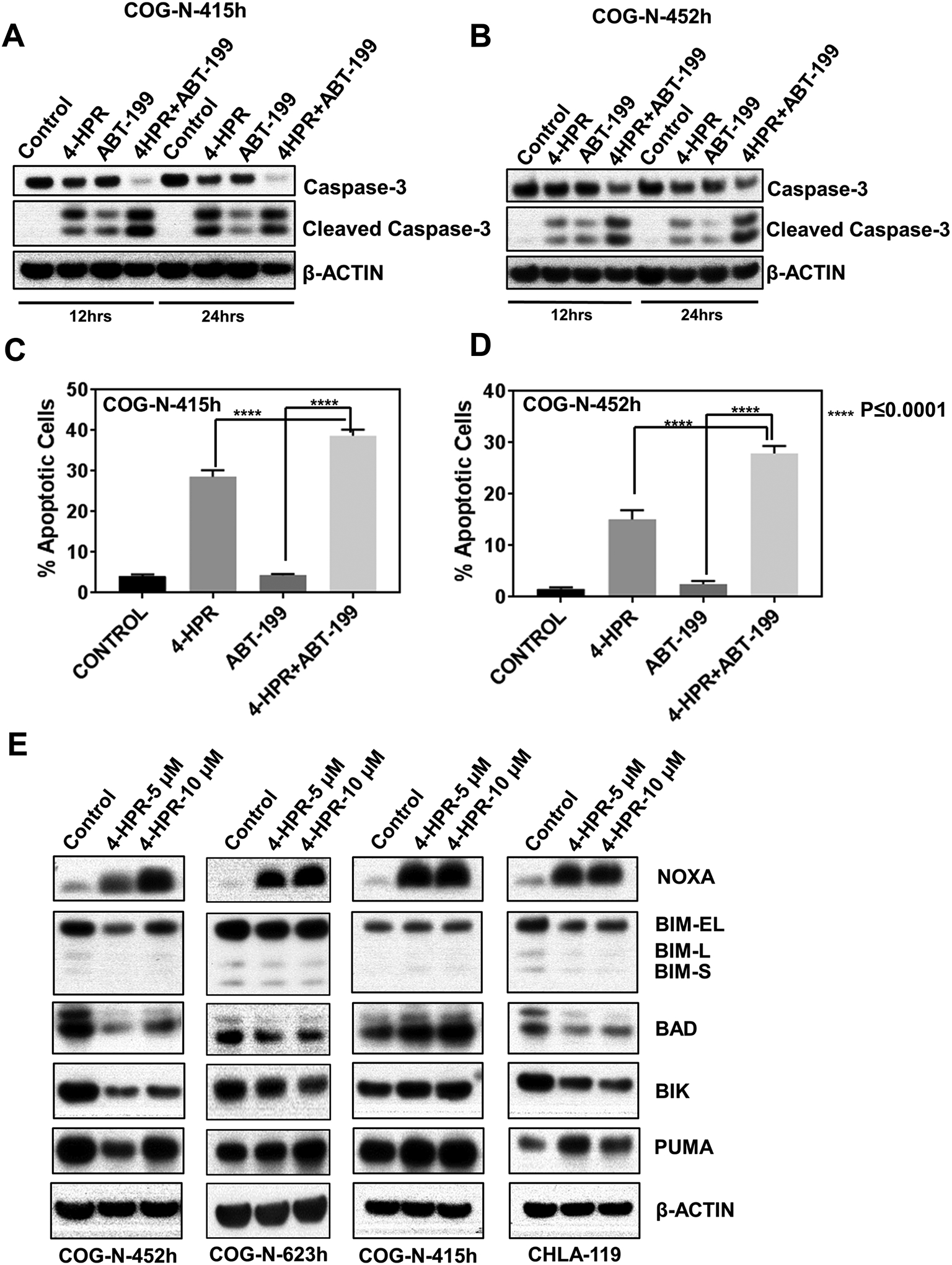

We observed that 4-HPR + ABT-199 induced greater caspase 3 cleavage (Fig. 4A, 4B) and higher DNA fragmentation measured by TUNEL assay (P≤0.0001, Fig. 4C, 4D) compared to both single agents. These data suggest that apoptosis plays a major role in the combination cytotoxicity of 4-HPR + ABT-199. To study the specific mechanism of apoptosis, changes in expression of the pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family of proteins after 4-HPR treatment at 5 μM and 10 μM was evaluated. 4-HPR increased NOXA while no increase was observed in other pro-apoptotic proteins (Fig. 4E). Moreover, 4-HPR treatment also increased the ratio of NOXA to MCL-1 protein (Fig. S5). These data suggest that an increase in NOXA expression by 4-HPR plays an important role in the enhanced apoptosis observed with the 4-HPR + ABT-199 combination.

Figure 4.

Apoptosis and induction of NOXA by 4-HPR + ABT-199. A & B, 4-HPR + ABT-199 induced greater caspase 3 cleavage compared with both single agents and the control. COG-N-415h and COG-N-452h were treated with vehicle, 4-HPR (10 μM), ABT-199 (2 μM), or 4-HPR + ABT-199 (10 μM + 2 μM) for 12 hrs or 24 hrs before immunoblotting. C & D, 4-HPR + ABT-199 induced greater apoptosis compared with both single agents. COG-N-415h and COG-N-452h were treated with vehicle, 4-HPR (10 μM), ABT-199 (2 μM), or 4-HPR + ABT-199 (10 μM+2 μM) for 24 hrs and 48 hrs respectively before staining for the TUNEL assay. E, 4-HPR induced NOXA protein expression in multiple neuroblastoma cell lines. CHLA-119, COG-N-452h, COG-N-415h, and COG-N-623h were treated with 5 μM and 10 μM of 4-HPR for 12 hrs and subjected to immunoblotting for NOXA, BIM, BAD, BIK, and PUMA.

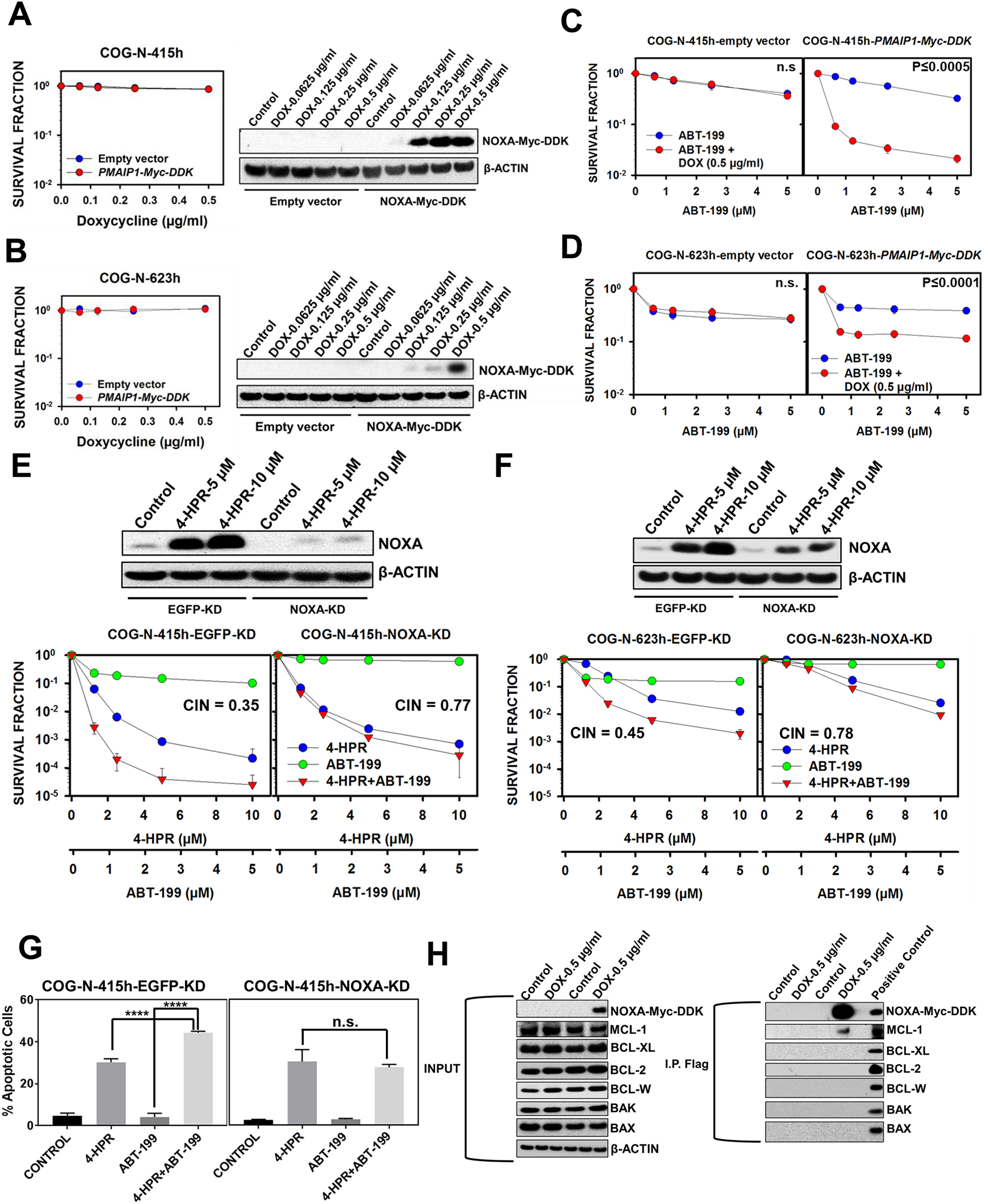

Knock-down of NOXA abolished 4-HPR + ABT-199 synergy while overexpressing NOXA enhanced ABT-199 cytotoxicity.

To determine whether NOXA can enhance the apoptosis induced by ABT-199, we transduced two neuroblastoma cell lines, COG-N-415h and COG-N-623h, with either empty vector or a PMAIP1 (encoding NOXA) doxycycline-inducible vector (PMAIP1-myc-DDK). Doxycycline (0.5 μg/ml) induced NOXA protein expression without significantly affecting the cell viability in both cell lines (Fig. 5A, 5B). ABT-199 (in the presence of doxycycline) induced much higher cytotoxicity in cells transduced with PMAIP1-myc-DDK relative to the cells transduced with empty vector in both tested cell lines (Fig. 5C, 5D).

Figure 5.

NOXA as a crucial mediator of 4-HPR + ABT-199 synergy. A & B, COG-N-415h and COG-N-623h, transduced with either empty vector or PMAIP1-Myc-DDK, were treated with different concentrations of doxycycline for 48 hrs before being subjected to immunoblotting for NOXA (Myc-DDK tagged) protein. Cells were also treated with different concentrations of doxycycline (6 replicates per drug concentration) for 96 hrs then analyzed for cytotoxicity by DIMSCAN. Doxycycline 0.5 μg/ml was selected to induce NOXA-Myc-DDK expression for both COG-N-415h and COG-N-623h. C & D, COG-N-415h and COG-N-623h, transduced with either empty vector or the PMAIP1-Myc-DDK doxycycline-inducible vector, were treated with doxycycline (0.5 μg/ml) for 48 hrs before being treated with different concentration of ABT-199 for 96 hrs and then analyzed for cytotoxicity by DIMSCAN. E & F, NOXA knockdown (KD) reduced the NOXA protein induced by 4-HPR (5 μM and 10 μM at 12 hrs) for both COG-N-415h and COG-N-623h and decreased the cytotoxicity of 4-HPR + ABT-199. Cell lines, transduced with either EGFP-KD or NOXA-KD shRNA, were treated with 4-HPR, ABT-199, or 4-HPR + ABT-199 for 96 hrs before being analyzed for cytotoxicity by DIMSCAN. G, NOXA knockdown (KD) attenuated the enhanced apoptosis of 4-HPR + ABT-199 relative to 4-HPR and ABT-199 as single agents. COG-N-415h, transduced with either EGFP-KD or NOXA-KD plasmid, were treated with 4-HPR, ABT-199, or 4-HPR + ABT-199 for 24 hrs before being stained for the TUNEL assay. H, NOXA protein binds explicitly to the MCL-1 protein. COG-N-623h, transduced with either empty vector or PMAIP1-Myc-DDK doxycycline-inducible vector, were treated with doxycycline (0.5 μg/ml) for 48 hrs before being harvested and immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody (for NOXA-Myc-DDK) and then immunoblotted to detect BCL-2, MCL-1, BCL-W, BCL-XL, BAX, and BAK.

To further confirm the role of NOXA in the combination cytotoxicity of 4-HPR + ABT-199, we stably knocked down NOXA and conducted in vitro cytotoxicity experiments in COG-N-415h and COG-N-623h. We found that NOXA knockdown reduced the cytotoxicity of single-agent ABT-199 and decreased the synergy of 4-HPR + ABT-199 in both cell lines (Fig. 5E, 5F). NOXA knockdown also diminished the enhanced apoptosis observed by 4-HPR + ABT-199 relative to single agents (Fig. 5G). Together, these data demonstrate that NOXA induction by 4-HPR is a key mechanism of 4-HPR + ABT-199 synergy.

NOXA binds to MCL-1 while having little affinity to other anti-apoptotic proteins (39,40). To verify NOXA affinity for MCL-1 in our system, NOXA immunoprecipitation was conducted in COG-N-623h transduced with PMAIP1-Myc-DDK or the empty vector. Only MCL-1, not BCL-2, BCL-W, or BCL-XL, was detected in NOXA pull-down samples (Fig. 5H). NOXA is also known as a sensitizer pro-apoptotic protein, which does not directly bind to activated BAX/BAK oligomerization but instead enhances apoptosis by inhibiting MCL-1 (4). We also found that NOXA does not directly bind to BAX or BAK (Fig. 5H). These data suggest that 4-HPR enhanced ABT-199 activity by inducing NOXA which specifically binds to and inhibits the MCL-1 protein.

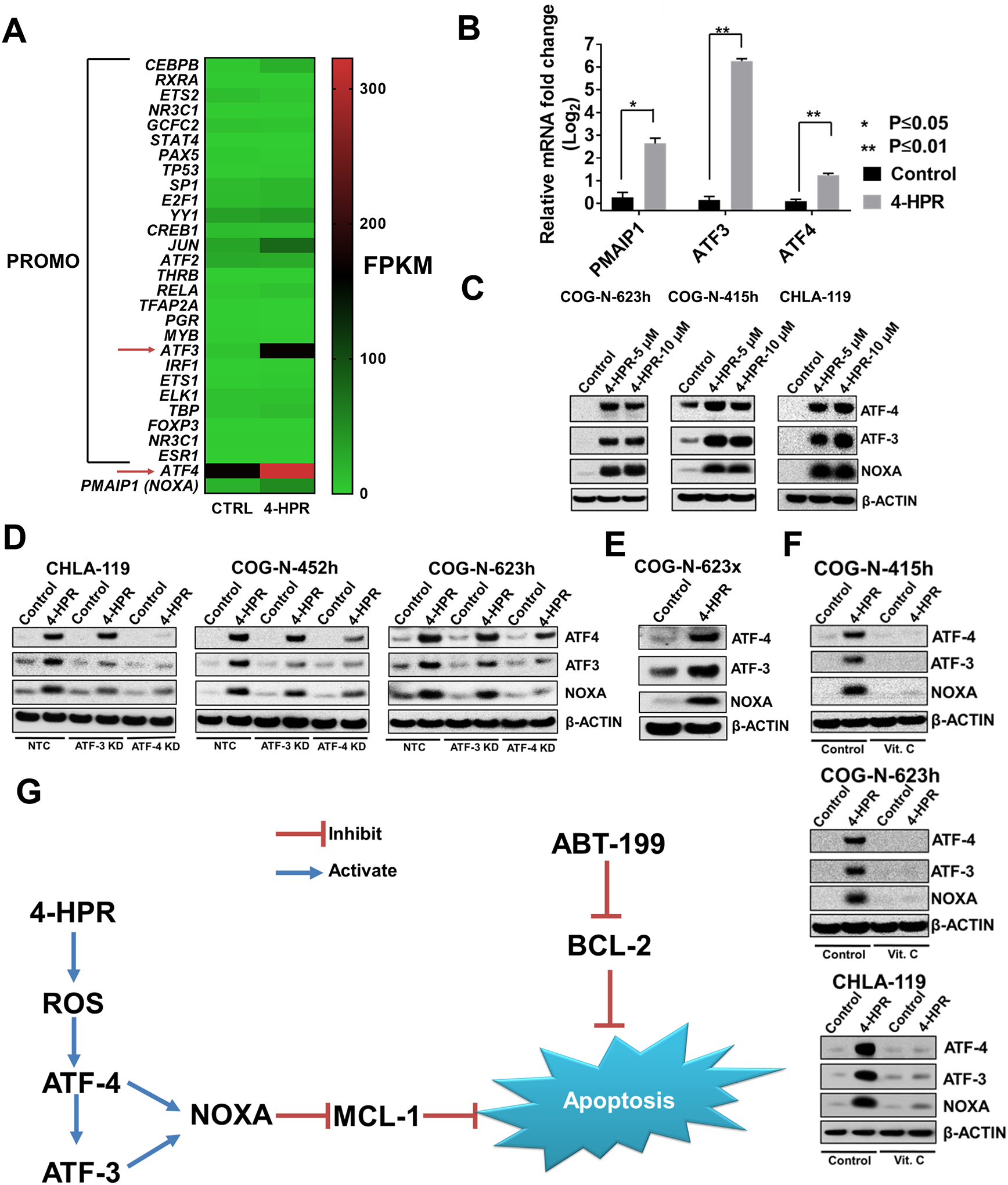

4-HPR induced NOXA though the ATF3 and ATF4 pathway.

In order to determine the mechanism of NOXA induction by 4-HPR, we analyzed control and 4-HPR-treated (5 μM for 15 hrs) CHLA-119 cells by RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). The transcription factors binding to the PMAIP1 (NOXA) promoter were identified using transcription factor analysis available with the PROMO database (41,42). Expression of ATF3 (a transcription factor binding to CTACGTCA sequence of the PMAIP1 promoter) and ATF4 (a transcription factor forming a complex with ATF3 to activate PMAIP1) were elevated in 4-HPR-treated cells relative to control cells (Fig. 6A). Even though the PROMO database did not identify ATF4 as a potential transcription factor of the PMAIP1 promoter, we found that ATF4 has also been reported to bind to the CTACGTCA sequence of the PMAIP1 promoter (44) and that mutation of this sequence reduced the PMAIP1 promoter activation by ATF4 (44). Moreover, ATF4 has been reported to activate the ATF3 promoter (45). In multiple neuroblastoma cell lines treated with 4-HPR ATF-3, ATF-4, and NOXA mRNA were increased (Fig. 6B, S6A, S6B), and 4-HPR also increased ATF-3, ATF-4, and NOXA protein expression (Fig 6C). ATF3 and ATF4 knockdown by siRNA reduced NOXA protein induced by 4-HPR, while ATF4 knockdown had greater effect in reducing 4-HPR-induced NOXA expression compared with ATF3 knockdown (Fig. 6D). ATF4 knockdown also reduced the level of ATF3 protein induced by 4-HPR (Fig. 6D), confirming that ATF4 is upstream of ATF3 and NOXA. In mice bearing the COG-N-623x PDX treated with either vehicle or 4-HPR + keto for four days ATF4, ATF3, and NOXA proteins were induced in the PDX tumors by 4-HPR (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

Induction of ATF-3 and ATF-4 transcription factors by 4-HPR-induced ROS mediate induction of NOXA expression in neuroblastoma. A, RNA sequencing was carried out with control and 4-HPR-treated (5 μM for 15hrs) CHLA-119 cells; expression of selected genes are shown in the heat map. We used the PROMO database and PMAIP1 promoter sequence (-500 to 0 of the ATG transcription start site) to further narrow down RNA-seq data to transcription factors binding to the PMAIP1 promoter. ATF3, a transcription factor known to activate PMAIP1 promoter (43), showed the highest increase in response to 4-HPR. ATF4, a transcription factor known to activate ATF3 and PMAIP1 promoter (44,45), is also upregulated. Heatmap scale was adjusted to emphasize differences in transcription factor expression. Relative differences in expression are better visualized in Figure 6B. B, 4-HPR treatment significantly upregulated NOXA, ATF3, and ATF4 mRNA expression compared to controls. CHLA-119 was treated with 4-HPR (5 μM) or vehicle control for 6 hrs before being harvested for measuring changes in mRNA expression by RT-PCR. C, 4-HPR treatment at 5 μM and 10 μM for 12 hrs induced both ATF3 and ATF4 protein expression along with NOXA protein expression in multiple tested neuroblastoma cell lines. D, Knock-down of ATF3 and ATF4 using siiRNA reduced NOXA induction by 4-HPR treatment in multiple neuroblastoma cell lines. Cell lines were transfected with either non-targeted control (NTC) siRNA, ATF3 siRNA, or ATF-4 siRNA for 12 hrs before being treated with 4-HPR (5 μM) for 6 hrs, harvested, and blotted for ATF-3, ATF-4, and NOXA. E, Mice bearing COG-N-623x (PDX) were treated with either vehicle or 4-HPR + keto for four days before the tumors being harvested and subjected to immunoblotting for NOXA, ATF3, and ATF4 protein. Figure shows representative data from tumors in 2 mice, control and 4-HPR treated. F, Vitamin C (Vit. C) reduced ATF3, ATF4, and NOXA induced by 4-HPR treatment. Cells were pre-treated with vitamin C (150 μM) for 1 hrs before being treated with 4-HPR for 12 hrs. G, Mechanism of 4-HPR + ABT-199 mechanism of synergy.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been shown to be one of the mechanisms of 4-HPR cytotoxicity, and vitamin C, an antioxidant capable of penetrating into mitochondria,, can neutralize the ROS generated by 4-HPR (34,46). ATF4 is reported as an ROS responsive gene (47), which suggests that ROS generated by 4-HPR is upstream of the ATF4, ATF3, and NOXA pathway. COG-N-623h and COG-N-415h were pretreated with vitamin C for 1 hr before incubating with 4-HPR for 12 hrs prior to immunoblotting. Vitamin C attenuated the expression of ATF-3, ATF-4, and NOXA induced by 4-HPR (Fig. 6F) and significantly decreased the cytotoxicity of 4-HPR + ABT-199 (Fig. S7). ATF-4, ATF-3, and NOXA were not induced by all-trans retinoic acid (Fig. S6E). Together, our data suggest that 4-HPR induced NOXA through generating ROS which activates the ATF4 and ATF3 pathway.

4-HPR induced NOXA is independent of MYCN.

MYCN has been shown to activate NOXA promoter (6); however treatment of 4-HPR decreased MYCN protein in MYCN amplified cell lines (Fig. S8A). We also observe that Vit. C can reverse the effect of 4-HPR reducing MYCN protein expression. Our data suggested that NOXA induced by 4-HPR is independent of MYCN protein expression and that 4-HPR can reduce the MYCN protein expression in neuroblastoma models.

BCL-2 is a more robust predictor than MYCN amplification status for ABT-199 single agent sensitivity and 4-HPR+ABT-199 combination synergy.

In order to confirm BCL-2 as the marker of 4-HPR+ABT-199 combination synergy, we separated all neuroblastoma cell lines (n=28) with available BCL-2 protein expression into either high BCL-2 protein expression or low BCL-2 protein expression group (Fig. S9A). We used ABT-199 fraction affected (Fa) at 1.25 μM as the marker of ABT-199 sensitivity since not all cell lines were able to achieve IC50 at the maximum tested concentration of ABT-199. We found that the high BCL-2 protein expression group showed significantly higher sensitivity to single agent ABT-199 (Fig. S9B) and significantly higher synergy to the combination of 4-HPR+ABT-199 (Fig. S9C). Using the same group of cell lines, we separated them into either MYCN-amplified or MYCN non-amplified groups. We found that there were no significant difference in ABT-199 single agent sensitivity (Fig. S9D) or 4-HPR+ABT-199 combination synergy (Fig. S9E) between the MYCN-amplified or non-amplified groups of lines.

Discussion

Neuroblastoma, especially high-risk neuroblastoma remains a therapeutic challenge (1,48). Identifying well-tolerated drug combinations that are not cross-resistant with currently employed therapy would enable testing in patients with progressive disease and eventual incorporation into up-front treatment regimens. We demonstrated that combining 4-HPR + ABT-199 is both highly synergistic in vitro at concentrations that are achievable in the plasma for each single agent in patients and was more active than either of the single agents against multiple high BCL-2 expressing PDXs established from patients who developed progressive disease on currently available therapy. ABT-199 + 4-HPR was also active against neuroblastoma PDXs established from patients at time of progressive disease (using dosing comparable to that used for single agents in patients). ABT-199 + 4-HPR was equally active against a neuroblastoma PDX that developed resistance to cyclophosphamide + topotecan and a PDX from the same patient established at diagnosis that was sensitive to cyclophosphamide + topotecan. 4 -HPR has shown tolerable toxicity and achieved multiple complete responses in a phase 1 clinical trial for high-risk neuroblastoma (20). ABT-199 received FDA approval for treating CLL with 17p deletion, and it showed manageable systemic toxicities (14,15). Thus, combining these two agents in neuroblastoma patients with high BCL-2 expression may provide a regimen with minimal systemic toxicities that is active against progressive neuroblastoma.

High BCL-2 expression is known as a marker of sensitivity to BCL-2 inhibitors in cancer cells, including neuroblastoma (5,25,26). We demonstrated that BCL-2 protein levels are consistent between tumors cells obtained at diagnosis and at progressive disease (the latter all from blood or bone marrow) using paired cell lines and a PDX pair from 10 patients. This opens the possibility of assessing BCL-2 protein expression in tumor biopsies of neuroblastoma obtained at diagnosis to identify patients with progressive disease that are more likely to respond to 4-HPR + ABT-199.

The survival of neuroblastoma cells depend on either MCL-1 or BCL-2 protein (5). Targeting only BCL-2 protein has been shown to cause neuroblastoma cells to depend on MCL-1 for survival (5). Consistent with observations by others (6,18,19) we found that in some neuroblastoma cell lines and PDXs single agent ABT-199 induced cytotoxicity but ABT-199 single agent activity is often modest. Thus, clinical development of ABT-199 has focused on combinations with traditional cytotoxic agents for which tolerability in patients has yet to be demonstrated and may be limited by enhanced marrow toxicity (49). Thus, development of combinations of agents with ABT-199 that have minimal marrow toxicity, such as 4-HPR, are warranted.

The synergism between 4-HPR and ABT-199 is similar to synergism we observed between 4-HPR and ABT-737 (11), with 4-HPR benefiting from inhibition of BCL-2 while at the same time inhibiting MCL-1. Here we have demonstrated that the mechanism of MCL-1 inhibition is via induction of NOXA, which specifically binds to MCL-1 and prevents MCL-1 from interfering with the pro-apoptotic function of ABT-199. Moreover, knocking down and also overexpressing NOXA confirmed that induction of NOXA is key to enhancing ABT-199 activity against neuroblastoma.

Inducing NOXA through MYCN has been shown to increase ABT-199 activity in MYCN amplified neuroblastoma cell lines (6). However, we have demonstrated that 4-HPR induction of NOXA protein is greater than NOXA expression seen in MYCN-amplified cell lines. Moreover, we also observed that 4-HPR can reduce MYCN protein in MYCN-amplified cell lines indicating that the mechanism of 4-HPR inducing NOXA production is independent of MYCN. The increase in NOXA protein epresssion, either by 4-HPR treatment or through the NOXA plasmid transduction, significantly increased the activity of ABT-199 in MYCN-amplified cell lines. Moreover, we also observed that BCL-2 expression is a stronger predictor compared to MYCN genomic amplification for BCL-2 single agent sensitivity or for 4-HPR+ABT-199 combination synergy. Taken together our data indicate that the enhanced cytotoxicity of ABT-199 when combined with 4-HPR is independent of the MYCN-amplification status of neurolblastoma cells.

In investigating how 4-HPR induced NOXA protein expression, we discovered that 4-HPR induced NOXA through generating ROS, which can activate the ATF4 and ATF3 transcription factors. ATF3 and ATF4 have been shown to transcriptionally activate PMAIP1, the gene encoding NOXA, the ATF4 and ATF3 induction are generally associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress which can be induced by proteasome inhibitors (43). Our study is the first to demonstrate that 4-HPR induces NOXA protein expression via ATF4 and ATF3. It has been suggested that 4-HPR generates ROS by inhibiting the mitochondrial electron complexes (50) and previous studies have shown that vitamin C, a mitochondrial-penetrating anti-oxidant, can effectively attenuate 4-HPR cytotoxicity (34,46). We showed that vitamin C significantly reduced induction by 4-HPR of ATF3, ATF4, and NOXA, and also reduced 4-HPR + ABT-199 cytotoxicity, thus implicating 4-HPR-generated ROS in the induction of NOXA and the synergy of 4-HPR + ABT-199.

In summary, 4-HPR + ABT-199 demonstrated synergistic activity in preclinical models of neuroblastoma with high BCL-2 protein expression via induction of NOXA by 4-HPR. In our preclinical models, BCL-2 protein expression identified neuroblastomas with high sensitivity to 4-HPR + ABT-199. BCL-2 protein expression was consistent from diagnosis to progressive disease in pairs of cell lines and PDXs established from the same patients. These data support carrying out early-phase clinical trials of 4-HPR + ABT-199 in neuroblastomas with high BCL-2 expression in tumor biopsies obtained at any time during the course of therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The cell lines and PDXs models used in the study were provided by the Childhood Cancer Repository Powered by Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation (www.CCcells.org). We thank Tito Woodburn, Heather L. Davidson, Kristyn E. McCoy, and Jonas A. Nance for their efforts in establishing neuroblastoma models, and Dr. Michael M. Song for preparing the laboratory samples for RNA-seq analyses. We thank Dr David Wheeler and Joy Jayaseelan of the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Texas for the RNA sequencing. We thank Dr. Lluis Lopez-Barcons for his help in in vivo xenograft experiments. Supported by National Cancer Institute grant CA221957 (CP Reynolds + MH Kang) and Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation (CP Reynolds).

Footnotes

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest C. P. Reynolds reports being a co-inventor on issued patents on intravenous formulations of fenretinide with financial interests through institutional intellectual property revenue sharing agreements, and is a consultant to, and owns stock in, CerRx, Inc., that licenses this technology; M. H. Kang is a consultant to CerRx, Inc. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by other authors.

References

- 1.Matthay KK, Maris JM, Schleiermacher G, Nakagawara A, Mackall CL, Diller L, et al. Neuroblastoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16078 doi 10.1038/nrdp.2016.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, London WB, Kreissman SG, Chen HX, et al. Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363(14):1324–34 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa0911123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008;9(1):47–59 doi http://www.nature.com/nrm/journal/v9/n1/suppinfo/nrm2308_S1.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang MH, Reynolds CP. Bcl-2 inhibitors: targeting mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15(4):1126–32 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldsmith KC, Gross M, Peirce S, Luyindula D, Liu X, Vu A, et al. Mitochondrial Bcl-2 family dynamics define therapy response and resistance in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 2012;72(10):2565–77 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ham J, Costa C, Sano R, Lochmann TL, Sennott EM, Patel NU, et al. Exploitation of the Apoptosis-Primed State of MYCN-Amplified Neuroblastoma to Develop a Potent and Specific Targeted Therapy Combination. Cancer Cell 2016;29(2):159–72 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamers F, Schild L, den Hartog IJ, Ebus ME, Westerhout EM, Ora I, et al. Targeted BCL2 inhibition effectively inhibits neuroblastoma tumour growth. Eur J Cancer 2012;48(16):3093–103 doi 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beurlet S, Omidvar N, Gorombei P, Krief P, Le Pogam C, Setterblad N, et al. BCL-2 inhibition with ABT-737 prolongs survival in an NRAS/BCL-2 mouse model of AML by targeting primitive LSK and progenitor cells. Blood 2013;122(16):2864–76 doi 10.1182/blood-2012-07-445635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang MH, Wan Z, Kang YH, Sposto R, Reynolds CP. Mechanism of synergy of N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide and ABT-737 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines: Mcl-1 inactivation. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100(8):580–95 doi 10.1093/jnci/djn076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason KD, Vandenberg CJ, Scott CL, Wei AH, Cory S, Huang DC, et al. In vivo efficacy of the Bcl-2 antagonist ABT-737 against aggressive Myc-driven lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105(46):17961–6 doi 10.1073/pnas.0809957105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang H, Harned TM, Kalous O, Maldonado V, DeClerck YA, Reynolds CP. Synergistic activity of fenretinide and the Bcl-2 family protein inhibitor ABT-737 against human neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17(22):7093–104 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner EE, Connis N, Poirier JT, Cope L, Dobromilskaya I, Gallia GL, et al. Rapamycin rescues ABT-737 efficacy in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 2014;74(10):2846–56 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER, Ackler SL, Catron ND, Chen J, et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat Med 2013;19(2):202–8 doi 10.1038/nm.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashkenazi A, Fairbrother WJ, Leverson JD, Souers AJ. From basic apoptosis discoveries to advanced selective BCL-2 family inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017;16(4):273–84 doi 10.1038/nrd.2016.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J, Coutre S, Seymour JF, Munir T, et al. Venetoclax in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17(6):768–78 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu H, Almasan A. Development of venetoclax for therapy of lymphoid malignancies. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:685–94 doi 10.2147/DDDT.S109325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaillant F, Merino D, Lee L, Breslin K, Pal B, Ritchie ME, et al. Targeting BCL-2 with the BH3 mimetic ABT-199 in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Cell 2013;24(1):120–9 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lochmann TL, Powell KM, Ham J, Floros KV, Heisey DAR, Kurupi RIJ, et al. Targeted inhibition of histone H3K27 demethylation is effective in high-risk neuroblastoma. Sci Transl Med 2018;10(441) doi 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanos R, Karmali D, Nalluri S, Goldsmith KC. Select Bcl-2 antagonism restores chemotherapy sensitivity in high-risk neuroblastoma. BMC Cancer 2016;16:97 doi 10.1186/s12885-016-2129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurer BJ, Kang MH, Villablanca JG, Janeba J, Groshen S, Matthay KK, et al. Phase I trial of fenretinide delivered orally in a novel organized lipid complex in patients with relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma: a report from the New Approaches to Neuroblastoma Therapy (NANT) consortium. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60(11):1801–8 doi 10.1002/pbc.24643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hail N, Jr., Kim HJ, Lotan R. Mechanisms of fenretinide-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis 2006;11(10):1677–94 doi 10.1007/s10495-006-9289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keshelava N, Zuo JJ, Chen P, Waidyaratne SN, Luna MC, Gomer CJ, et al. Loss of p53 function confers high-level multidrug resistance in neuroblastoma cell lines. Cancer Res 2001;61(16):6185–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, Maurer BJ, Liu YY, Wang E, Allegood JC, Kelly S, et al. N-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)retinamide increases dihydroceramide and synergizes with dimethylsphingosine to enhance cancer cell killing. Mol Cancer Ther 2008;7(9):2967–76 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurer BJ, Melton L, Billups C, Cabot MC, Reynolds CP. Synergistic cytotoxicity in solid tumor cell lines between N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide and modulators of ceramide metabolism. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92(23):1897–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merino D, Khaw SL, Glaser SP, Anderson DJ, Belmont LD, Wong C, et al. Bcl-2, Bcl-x(L), and Bcl-w are not equivalent targets of ABT-737 and navitoclax (ABT-263) in lymphoid and leukemic cells. Blood 2012;119(24):5807–16 doi 10.1182/blood-2011-12-400929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bate-Eya LT, den Hartog IJ, van der Ploeg I, Schild L, Koster J, Santo EE, et al. High efficacy of the BCL-2 inhibitor ABT199 (venetoclax) in BCL-2 high-expressing neuroblastoma cell lines and xenografts and rational for combination with MCL-1 inhibition. Oncotarget 2016;7(19):27946–58 doi 10.18632/oncotarget.8547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grigoryan R, Keshelava N, Anderson C, Reynolds CP. In vitro testing of chemosensitivity in physiological hypoxia. Methods Mol Med 2005;110:87–100 doi 10.1385/1-59259-869-2:087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keshelava N, Frgala T, Krejsa J, Kalous O, Reynolds CP. DIMSCAN: a microcomputer fluorescence-based cytotoxicity assay for preclinical testing of combination chemotherapy. Methods Mol Med 2005;110:139–53 doi 10.1385/1-59259-869-2:139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frgala T, Kalous O, Proffitt RT, Reynolds CP. A fluorescence microplate cytotoxicity assay with a 4-log dynamic range that identifies synergistic drug combinations. Mol Cancer Ther 2007;6(3):886–97 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang MH, Smith MA, Morton CL, Keshelava N, Houghton PJ, Reynolds CP. National Cancer Institute pediatric preclinical testing program: model description for in vitro cytotoxicity testing. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;56(2):239–49 doi 10.1002/pbc.22801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Ni X, Covington KR, Yang BY, Shiu J, Zhang X, et al. Genomic profiling of Sezary syndrome identifies alterations of key T cell signaling and differentiation genes. Nat Genet 2015;47(12):1426–34 doi 10.1038/ng.3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013;29(1):15–21 doi 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc 2012;7(3):562–78 doi 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makena MR, Koneru B, Nguyen TH, Kang MH, Reynolds CP. Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Synergism of Fenretinide and Romidepsin in Preclinical Models of T-cell Lymphoid Malignancies. Mol Cancer Ther 2017;16(4):649–61 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maurer BJ, Kalous O, Yesair DW, Wu X, Janeba J, Maldonado V, et al. Improved oral delivery of N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide with a novel LYM-X-SORB organized lipid complex. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13(10):3079–86 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper JP, Hwang K, Singh H, Wang D, Reynolds CP, Curley RW Jr., et al. Fenretinide metabolism in humans and mice: utilizing pharmacological modulation of its metabolic pathway to increase systemic exposure. Br J Pharmacol 2011;163(6):1263–75 doi 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds CP, Maurer BJ. Evaluating response to antineoplastic drug combinations in tissue culture models. Methods Mol Med 2005;110:173–83 doi 10.1385/1-59259-869-2:173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashraf K, Shaikh F, Gibson P, Baruchel S, Irwin MS. Treatment with topotecan plus cyclophosphamide in children with first relapse of neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60(10):1636–41 doi 10.1002/pbc.24587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shamas-Din A, Brahmbhatt H, Leber B, Andrews DW. BH3-only proteins: Orchestrators of apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1813(4):508–20 doi 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen L, Willis SN, Wei A, Smith BJ, Fletcher JI, Hinds MG, et al. Differential targeting of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins by their BH3-only ligands allows complementary apoptotic function. Mol Cell 2005;17(3):393–403 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Messeguer X, Escudero R, Farre D, Nunez O, Martinez J, Alba MM. PROMO: detection of known transcription regulatory elements using species-tailored searches. Bioinformatics 2002;18(2):333–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farré D, Roset R, Huerta M, Adsuara JE, Roselló L, Albà MM, et al. Identification of patterns in biological sequences at the ALGGEN server: PROMO and MALGEN. Nucleic Acids Research 2003;31(13):3651–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q, Mora-Jensen H, Weniger MA, Perez-Galan P, Wolford C, Hai T, et al. ERAD inhibitors integrate ER stress with an epigenetic mechanism to activate BH3-only protein NOXA in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106(7):2200–5 doi 10.1073/pnas.0807611106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qing G, Li B, Vu A, Skuli N, Walton ZE, Liu X, et al. ATF4 regulates MYC-mediated neuroblastoma cell death upon glutamine deprivation. Cancer Cell 2012;22(5):631–44 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu L, Kilberg MS. Elevated cJUN expression and an ATF/CRE site within the ATF3 promoter contribute to activation of ATF3 transcription by the amino acid response. Physiol Genomics 2013;45(4):127–37 doi 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00160.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen NE, Maldonado NV, Khankaldyyan V, Shimada H, Song MM, Maurer BJ, et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Mediates the Synergistic Activity of Fenretinide Combined with the Microtubule Inhibitor ABT-751 against Multidrug-Resistant Recurrent Neuroblastoma Xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther 2016;15(11):2653–64 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lange PS, Chavez JC, Pinto JT, Coppola G, Sun CW, Townes TM, et al. ATF4 is an oxidative stress-inducible, prodeath transcription factor in neurons in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med 2008;205(5):1227–42 doi 10.1084/jem.20071460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shohet J, Foster J. Neuroblastoma. BMJ 2017;357:j1863 doi 10.1136/bmj.j1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Place AE, Goldsmith K, Bourquin JP, Loh ML, Gore L, Morgenstern DA, et al. Accelerating drug development in pediatric cancer: a novel Phase I study design of venetoclax in relapsed/refractory malignancies. Future Oncol 2018;14(21):2115–29 doi 10.2217/fon-2018-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki S, Higuchi M, Proske RJ, Oridate N, Hong WK, Lotan R. Implication of mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species, cytochrome C and caspase-3 in N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide-induced apoptosis in cervical carcinoma cells. Oncogene 1999;18(46):6380–7 doi 10.1038/sj.onc.1203024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.